Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

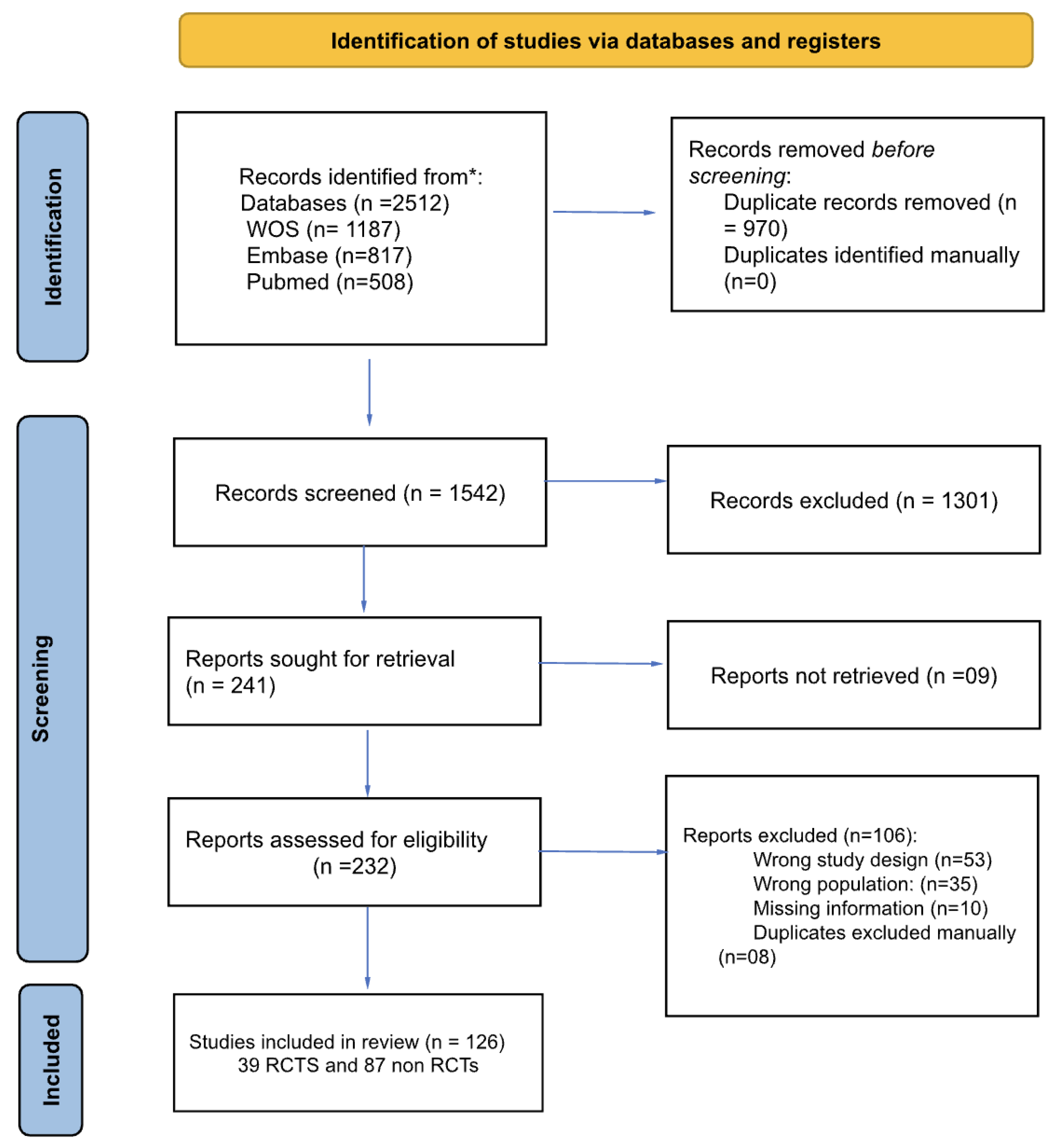

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence and Critical Appraisal

2.4. Data Charting Process

2.5. Data items and Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment

3.2. Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative Sensory Testing Methods

3.3. Static QST

3.4. Dynamic QST

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FMS | Fibromyalgia Syndrome |

| QST | Quantitative Sensory Testing |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| PPTh/PPT | Pressure Pain Threshold/Tolerance |

| MDTh/MPTh/MPS | Mechanical Detection/Pain Thresholds/Sensitivity |

| TPTh/TPT | Thermal Pain Threshold/Tolerance |

| TS | Temporal Summation |

| CPM | Conditioned Pain Modulation |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| ROB 2 | Risk of Bias Tool 2 |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

References

- D’Agnelli, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Gerra, M.C.; Zatorri, K.; Boggiani, L.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E. Fibromyalgia: Genetics and Epigenetics Insights May Provide the Basis for the Development of Diagnostic Biomarkers. Mol. Pain 2019, 15, 1744806918819944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.; Fang, Y.-H.D.; Jones, C.; McConathy, J.E.; Raman, F.; Lapi, S.E.; Younger, J.W. Evidence of Neuroinflammation in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A [ 18 F]DPA-714 Positron Emission Tomography Study. Pain 2023, 164, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mulder, B. Fibromyalgia Prevalence Available online:. Available online: https://www.fmaware.org/fibromyalgia-prevalence/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Siracusa, R.; Paola, R.D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D. Fibromyalgia: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment Options Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar]

- Beiner, E.; Lucas, V.; Reichert, J.; Buhai, D.-V.; Jesinghaus, M.; Vock, S.; Drusko, A.; Baumeister, D.; Eich, W.; Friederich, H.-C.; et al. Stress Biomarkers in Individuals with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Pain 2023, 164, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Bair, M.J.; Krebs, E.E. Fibromyalgia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, ITC33–ITC48. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Graven-Nielsen, T. Translational Musculoskeletal Pain Research. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 25, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos, V.; Akin-Akinyosoye, K.; Zhang, W.; McWilliams, D.F.; Hendrick, P.; Walsh, D.A. Quantitative Sensory Testing and Predicting Outcomes for Musculoskeletal Pain, Disability, and Negative Affect: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain 2019, 160, 1920–1932. [Google Scholar]

- Backonja, M.M.; Attal, N.; Baron, R.; Bouhassira, D.; Drangholt, M.; Dyck, P.J.; Edwards, R.R.; Freeman, R.; Gracely, R.; Haanpaa, M.H.; et al. Value of Quantitative Sensory Testing in Neurological and Pain Disorders: NeuPSIG Consensus. Pain 2013, 154, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, L.A.; Kazyiama, H.H.S.; Teixeira, M.J.; de Siqueira, S.R.D.T. Quantitative Sensory Testing in Fibromyalgia and Hemisensory Syndrome: Comparison with Controls. Rheumatol. Int. 2013, 33, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtig, I.M.; Raak, R.I.; Kendall, S.A.; Gerdle, B.; Wahren, L.K. Quantitative Sensory Testing in Fibromyalgia Patients and in Healthy Subjects: Identification of Subgroups. Clin. J. Pain 2001, 17, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmelz, M. What Can We Learn from the Failure of Quantitative Sensory Testing? Pain 2021, 162, 663–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Yarnitsky, D. Experimental and Clinical Applications of Quantitative Sensory Testing Applied to Skin, Muscles and Viscera. J. Pain 2009, 10, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Backonja, M.-M.; Walk, D.; Edwards, R.R.; Sehgal, N.; Moeller-Bertram, T.; Wasan, A.; Irving, G.; Argoff, C.; Wallace, M. Quantitative Sensory Testing in Measurement of Neuropathic Pain Phenomena and Other Sensory Abnormalities. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 641–647. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, J.; Rudy-Froese, B.; Hoyt, C.; Ramsahoi, K.; Gareau, L.; Howatt, W.; Carlesso, L. Quantitative Sensory Testing Protocols to Evaluate Central and Peripheral Sensitization in Knee OA: A Scoping Review. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 526–557. [Google Scholar]

- Tutelman, P.R.; MacKenzie, N.E.; Chambers, C.T.; Coffman, S.; Cornelissen, L.; Cormier, B.; Higgins, K.S.; Phinney, J.; Blankenburg, M.; Walker, S. Quantitative Sensory Testing for Assessment of Somatosensory Function in Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Pain Rep 2024, 9, e1151. [Google Scholar]

- Rolke, R.; Magerl, W.; Campbell, K.A.; Schalber, C.; Caspari, S.; Birklein, F.; Treede, R.-D. Quantitative Sensory Testing: A Comprehensive Protocol for Clinical Trials. Eur J Pain 2006, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Mücke, M.; Cuhls, H.; Radbruch, L.; Baron, R.; Maier, C.; Tölle, T.; Treede, R.-D.; Rolke, R. Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST). English Version. Schmerz 2021, 35, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, S.; Sachau, J.; Hellriegel, J.; Forstenpointner, J.; Børsting Jacobsen, H.; Harten, P.; Gierthmühlen, J.; Baron, R. Pain Matters for Central Sensitization: Sensory and Psychological Parameters in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain Rep 2021, 6, e901. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Design | ACR Diagnostic Criteria |

Arms | Total Females (%) |

Age Mean (SD) | QST Static |

QST Dynamic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorensen, 1995 | Non RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 47.5 (7.5) | Yes | No |

| Kosek, 1997 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 42.5 (28.5) | Yes | No |

| Ernberg, 1997 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 92 | 48.5 (14.3) | Yes | No |

| Hurtig, 2001 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 43 (37.9) | Yes | No |

| Price, 2002 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 45.5 (12.5) | No | Yes |

| Desmeules, 2003 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 88 | 48.3 (10.3) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2003 | Non RCT | 1990 | 1 | 87.3 | 49.9 (10.4) | No | Yes |

| Ernberg, 2003 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 92 | 48.5 (14.3) | Yes | No |

| Kendall, 2003 | Non RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 43.6 (7.3) | Yes | No |

| Yildiz, 2004 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 70 | 40.1 (4.7) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2004 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 42.9 (13.04) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2004 | Non RCT | 1990 | 1 | 94.6 | 49.6 (11.5) | Yes | No |

| Giesecke, 2005 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 62.3 | 40.2 (9) | Yes | No |

| Montoya, 2005 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 51.6 (5.9) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2005 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 47.05 (8.7) | Yes | No |

| Geisser, 2007 | Non RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 39.6 ( 9.2) | Yes | No |

| Jespersen, 2007 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 47 (6.08) | Yes | No |

| Smith, 2008 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 48 (6.8) | Yes | No |

| Targino, 2008 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 51.6 (11.07) | Yes | No |

| Diers, 2008 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 86.7 | 50.4(9.5) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2008 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 43.15 (9) | No | Yes |

| Suman, 2009 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 44.8 (11.7) | Yes | No |

| Ge, 2009 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 53 (2.4) | Yes | No |

| Stening, 2010 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 54.3 (3.4) | Yes | No |

| Nelson, 2010 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 51.7 (10.3) | Yes | No |

| Tastekin, 2010 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 42.7 (6.7) | Yes | No |

| de Bruijn, 2011 | Non RCT | 1990 | 1 | 100 | 37.3 (7.7) | Yes | No |

| Hassett, 2012 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 41.1 (10.8) | Yes | No |

| Martínez-Jauand, 2012 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 50.5 (9.4) | Yes | No |

| Paul-Savoie, 2012 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 49.8 (9.3) | Yes | Yes |

| Hargrove, 2012 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 92.2 | 52.6 (3.1) | Yes | No |

| Hooten, 2012 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 90.3 | 46.5 (10.8) | Yes | No |

| Hassett, 2012 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 38.8 (11.7) | Yes | No |

| Castro-Sanchez, 2012 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 50 | 52 (5.5) | Yes | No |

| Burgmer, 2012 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 52.59 (7.95) | Yes | No |

| Van Oosterwijck, 2013 | RCT |

1990 |

2 | 80 | 45.8 (10.9) | Yes | No |

| Üçeyler, 2013 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 91.42 | 56.4 (28.9) | Yes | No |

| Crettaz, 2013 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 40.2 (9.2) | Yes | Yes |

| Da Silva, 2013 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 96 | 49.9 (14.5) | Yes | Yes |

| Casanueva, 2013 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 53.7 (10.8) | Yes | No |

| Belenguer-Prieto, 2013 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 96.7 | 50.8 (7.8) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2014 | RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 45.8 (14.8) | Yes | No |

| Bokarewa, 2014 | Non RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 51 (2.5) | Yes | No |

| Castro-Sanchez, 2014 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 54 | 53.5(7.5) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2014 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 45.8 (14.8) | Yes | No |

| Vandenbroucke, 2014 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 94.8 | 39 (11.7) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2015 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 91.80 | 47.2 (12) | Yes | No |

| Qin, 2015 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 86.05 | 45(9.5) | Yes | No |

| Soriano-Maldonado, 2015 | Non RCT | 1990 | 1 | 100 | 48.3 (7.8) | Yes | No |

| Kin, 2015 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 84 | 44,6 (13.08) | Yes | No |

| Zamuner, 2015 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 47.07 (7) | Yes | No |

| Efrati, 2015 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 49.2 (11) | Yes | No |

| Oudejans, 2016 | RCT | 1990 | 1 | 92.31 | 39.2 (60.1) | Yes | Yes |

| Potvin, 2016 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 93.41 | 49.5 (8.2) | Yes | Yes |

| Schoen, 2016 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 42.7 (10.8) | Yes | Yes |

| Barbero, 2017 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 1 | 100 | 49.5 (8.1) | Yes | No |

| Forti, 2016 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 48.9 (7.2) | Yes | No |

| Gomez-Perretta, 2016 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 46.2 (10.5) | Yes | No |

| Saral, 2016 | RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 41.7 (7.7) | Yes | No |

| Mendonça, 2016 | RCT | 2010 | 3 | 97.8 | 19.5 (8.19) | Yes | No |

| Luciano, 2016 | RCT | 1990 | 1 | 100 | 57.28 (8.81) | Yes | No |

| Gerhardta, 2017 | Non RCT | 1990 | 3 | 72.88 | 56.8 (10) | Yes | Yes |

| de la Coba, 2017 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 53.09 (9.38) | No | Yes |

| Freitas, 2017 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 53.03(10.2) | Yes | No |

| Baumueller, 2017 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 55.6 (6.1) | Yes | No |

| Harper, 2018 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 40.7 (11.2) | No | Yes |

| Pickering, 2018 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 46.7 (10.6) | Yes | Yes |

| Merriwether, 2018 | Non RCT | 1990 | 1 | 100 | 49.3 (11.5) | Yes | Yes |

| Wodehouse, 2018 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 1 | 92.8 | 46.7(10.5) | Yes | Yes |

| Albers, 2018 | RCT | 1990 | 3 | 100 | 55.4 (11.9) | Yes | No |

| Galvez-Sanchez, 2018 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 49.02(8.2) | Yes | No |

| Eken, 2018 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 94 | 36.9 (7.5) | Yes | No |

| de la Coba, 2018 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 53.09 (10.4) | No | Yes |

| Evdokimov, 2019 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 2 | 100 | 52 (15.8) | Yes | Yes |

| Brietzke, 2019 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 42.2 (7.1) | Yes | Yes |

| Amer-Cuenca, 2019 | RCT | 1990/2010 | 4 | 100 | 53.2 (9) | Yes | Yes |

| Donk, 2019 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 94.1 | 44.5 (22.6) | Yes | Yes |

| Andrade, 2019 | RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 51.9 (8) | Yes | No |

| Udina-Cortés, 2020 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 52 (8.8) | Yes | Yes |

| Uygur-Kucukseymena, 2020 | Non RCT | 2010 | 1 | 88.5 | 53(13.52) | No | Yes |

| Kaziyama, 2020 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 44.4 (6.3) | Yes | No |

| Pickering, 2020 | Non RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 51 (9.6) | Yes | No |

| Sarmento, 2020 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 48.8 (11.4) | Yes | No |

| Yuan, 2020 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 97 | 51.07 (8.16) | Yes | No |

| Han, 2020 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 97 | 52 (8.74) | Yes | No |

| Izquierdo-Alventosa, 2020 | RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 54 (7.9) | Yes | No |

| Rehm, 2021 | Non RCT | 1990 | 1 | 95.5 | 50.4 (9.6) | Yes | No |

| Falaguera-Vera, 2020 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 2 | 100 | 55.6 (7.2) | Yes | No |

| Staud, 2021 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 48 (11.9) | Yes | No |

| Jamison, 2021 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 50.4 (13.5) | Yes | Yes |

| Jamison, 2021 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 93.3 | 50.3 (13.5) | Yes | Yes |

| Soldatelli, 2021 | Non RCT | 2010/2016 | 2 | 100 | 49.3 (8.6) | Yes | Yes |

| Karamanlioglu, 2021 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 43.7 (8.1) | Yes | No |

| Izquierdo-Alventosa, 2021 | RCT | 2016 | 3 | 100 | 52.8 (8.2) | Yes | No |

| Van Campen, 2021 | Non RCT | 2010 | 3 | 100 | 39.6 (12.3) | Yes | Yes |

| Weber, 2022 | Non RCT | 2016 | 2 | 81 | 49.9 (8.4) | Yes | Yes |

| Pacheco-Barrios, 2022 | Non RCT | 2010 | 1 | 86.21 | 47.6 (11.5) | Yes | Yes |

| De Paula, 2022 | RCT | 2016 | 4 | 100 | 49.3 (2.1) | Yes | Yes |

| Tour, 2022 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 47.5 (7.8) | Yes | Yes |

| Serrano, 2022 | Non RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 48.2 (9.8) | Yes | Yes |

| Alsouhibani, 2022 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 88.4 | 49.8 (14.4) | Yes | Yes |

| Franco, 2022 | Non RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 49.9 (10) | No | Yes |

| Samartin-Veiga, 2022 | RCT | 2010 | 4 | 100 | 50.2 (8.7) | Yes | No |

| Lin, 2022 | RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 48.5 (13.02) | Yes | No |

| Castelo-Branco, 2022 | Non RCT | 2010 | 4 | 87.8 | 48.8 (10.1) | No | Yes |

| Berwick, 2022 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 90 | 49.4 (10.6) | Yes | No | |

| Fanton, 2022 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 100 | 47.6 (7.7) | Yes | No | |

| Ablin, 2023 | RCT | 2016 | 2 | 79.3 | 45.1 (12.3) | Yes | Yes |

| Berardi, 2023 | RCT | 1990 | 4 | 100 | 48.7 (11.7) | Yes | Yes |

| Cigaran-Mendez, 2023 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 2 | 100 | 52.5(11) | Yes | Yes |

| Soldatelli, 2023 | Non RCT | 1990 | 2 | 100 | 49.6 (7.7) | No | Yes |

| Leone, 2023 | Non RCT | 2016 | 3 | 88.30 | 49.1 (11.7) | Yes | Yes |

| Bao, 2023 | RCT | 2016 | 3 | 100 | 43.6 (14.3) | No | Yes |

| Kumar, 2023 | Non RCT | 2010 | 1 | 100 | 35.1 (8.9) | Yes | No |

| Tapia-Haro, 2023 | Non RCT | 2010 | 1 | 100 | 56.06 (6.41) | Yes | No |

| Sanzo, 2024 | RCT | 2010 | 2 | 100 | 52.07(2.28) | Yes | Yes |

| Baumler, 2024 | Non RCT | 2010/2016 | 2 | 100 | 54.9(13.02) | Yes | No |

| Neira, 2024 | Non RCT | 1990/2010 | 2 | 100 | 50 (9) | Yes | No |

| Marshall, 2024 | Non RCT | 2016 | 3 | 93 | 45.4 (15.0) | Yes | No |

| Boussi-Gross, 2024 | RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 33.3 (5.9) | Yes | Yes |

| Coupel, 2024 | Non RCT | 2010 | 2 | 98.2 | 50.91 (10.04) | Yes | No |

| Berardi, 2024 | RCT | 1990 | 4 | 100 | 49.05 (11.6) | Yes | Yes |

| Aoe, 2024 | Non RCT | 2016 | 2 | 90 | 42.4 (11.1) | Yes | No |

| Castelo-Branco, 2024 | Non RCT | 2010 | 1 | 86.5 | 48.08 (11.12) | No | Yes |

| Gil-Ugidos, 2024 | Non RCT | 2010 | 1 | 100 | 56.06 (6.41) | Yes | No |

| Gungormus,2024 | RCT | 2016 | 2 | 100 | 54.5 (7.5) | Yes | Yes |

| Test Category | Testing Location | Test Category | Testing Location |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Static Quantitative Sensory Testing |

Dynamic Quantitative Sensory Testing |

||

| Mechanical Detection, Pain threshold or Mechanical Pain Sensitivity |

Forearm n=3Hands n=4Variable n=3 | Windup and Temporal Summation - Mechanical or Thermal | Forearm n=4 Hands n=7 Foots n=1 Variable n=3 |

| Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) | Forearm n=5 Hands n=17 Trapezius n=8 18 tender points n=24 Variable n=30 |

Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM) | Forearm n=12 Hands n=4 Foots n=2 Variable n=8 |

| Cold Pain Threshold or Cold Pain Tolerance | Forearm n=2 Hands n=9 Variable n=5 |

||

| Heat Pain Threshold or Tolerance | Forearm n=7 Hands n=6 Variable n=7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).