1. Introduction

Virtual Reality Immersion (VRI) has emerged as a transformative technology in education, providing learners with an interactive, immersive, and engaging learning environment. Research has increasingly focused on its cognitive and behavioral effects, particularly on students’ Habits of Mind (HoM), which encompass Self-Regulation (SR), Critical Thinking (CRIT), and Creative Thinking (CRET) (Guerra-Tamez et al., 2021; Marzano et al., 1993). The Cognitive Affective Model of Immersive Learning (CAMIL) provides a theoretical foundation for understanding how VRI influences cognitive outcomes through interaction, engagement, and exploration.

Kamińska et al. (2019) highlight the necessity of abstract thinking for learners, especially in science where concepts are not entirely tangible and might cause deficiencies in understanding fundamentals which consequently hinders further development and exploration of the learner. Solmaz et al. (2024) stated that cognitive and behavioral advantages of VR can help educators reduce introductory barriers of new concepts that students usually struggle with. Many applications of VR can be useful, unique, engaging, and motivating in the field of education.

There is evidence that HoM and cognitive learning outcomes in biology are affected by learning processes (Ariyati et al., 2024). Therefore, a focus on the components of SR, CRIT, and CRET is required by educators and teachers to get insights into the cognitive and metacognitive skills of students’ HoM and enhance it accordingly. VR-based biology classes are thought to be autotelic for the fun it provides to the learner.

As a result, modern technologies such as VR became of great importance in the educational field in a way that they affected every aspect of the teaching learning process as tools used to enhance learning motivation and student outcomes (Cevikbas et al., 2023). VR provides high levels of visual immersion. Makransky et al. (2021) emphasize that interactivity refers to the amount of freedom the user is given to control the learning experience, often through handheld controllers and a virtual body.

Educational VR is the construction of the desired learning environment through the simulation of computer equipment and adding real or virtual pictures in the simulated situations to live and realize that situation (Hu et al., 2016). It is visiting the subject matter virtually through technology while keeping safe, staying in place, and having the freedom to explore here and there. It provides with highly authentic interaction, allowing the users to operate and interact with the objects through the man-machine interface.

Therefore, VRI became a promising method of teaching science by increasing students’ engagement, and enhancing student’s SR, CRIT and CRET.

1.2. Theoretical Framework:

Recent studies about engagement support the idea that interactive teaching methods generate higher levels of students’ engagement (Kurt & Sezek, 2021). In a study about the use of VR in educational environments, Scavarelli et al. (2021) reflected optimism about the use of VR-based instruction for its effectiveness and ability to enhance learning outcomes. Students can engage with diverse perspectives, solve problems, and participate in analytical tasks which contribute to the development of CRIT when they work together. Attempts to enhance the quality of science teaching and learning process and enhancing HoM usually engage learners in scientific practices to encourage the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of the learners CRIT (Wang et al., 2024).

Educators nowadays can integrate a combination of media in the classroom to increase students’ interaction (Chang et al., 2011), therefore, an increased engagement or immersion, leading to better outcomes (Behmanesh et al., 2022; Haleem et al., 2022). VR in education has a great potential in providing students with immersive and interactive experiences. VRI technologies and learning experiences have been increasingly used in education settings to support a variety of instructional methods and outcomes by providing experiential and authentic learning experiences (Lowell & Yan, 2024; Marougkas et al., 2023).

HoM is a mixture of skills, attitudes, and experiences of the past and are very supportive of students’ performance in everyday life (Idris & Hidayati, 2017). They can be developed by applying specific learning models and techniques based on student-centred environments where students can freely explore their knowledge and share ideas.

1.2.2. Virtual Reality Immersion (VRI)

VRI is a state of mind that refers to the degree to which senses are absorbed in the virtual simulation with enjoyment, energy, and involvement (Berkman & Akan, 2019). Implementing VR in education provides a more immersive and engaging learning experience. VR takes the learners to difficult-to-access places, such as historical monuments, outer space or even within the human body. Students can better understand the subject and engage with the learning material (Marougkas et al., 2023). According to Di Mitri et al. (2024) immersive learning highlights the idea of enhancing the quality of authenticity of educational experiences. It can create different levels of realism, feedback, and interaction using high-immersion VR.

Digital immersive technologies according to Tang (2024) promote divergent thinking and self-directed learning. Engagement through immersion provides interaction and participatory experiences that encourage learners to engage in learning responsively and develop critical thinking by providing chances to solve problems and make decisions.

Immersion, according to Schubert et al. (2001) is a cognitive process that leads to the emergence of presence. Presence is a psychological phenomenon or a state of consciousness that generates a sense of being in the virtual environment.

1.3. Habits of Mind (HoM)

HoM refers to the way our minds behave when confronted with a challenging situation that requires strategic reasoning, insightfulness, perseverance, creativity, and craftsmanship to resolve a complex problem (Costa & Kallick, 2000; Idris & Hidayati, 2017).

1.3.1. Self Regulation (SR)

SR refers to the learner’s ability to employ a set of meta skills that enable awareness, monitoring, and adaptation of learning strategies through cognitive and metacognitive processes to maintain psychophysiological balance (Mitsea et al., 2023; Zimmerman, 2002). It is the ability to judge consistency of actions with internal and external demands which enables the learner to adaptively redirect him or herself (Mitsea et al., 2023).

1.3.2. Critical Thinking (CRIT)

CRIT is the ability to look deep into the problem from different perspectives, understand it, analyse it, and finally make a decision about the best actions to be taken to handle it (Jamaludin et al., 2022; Kusmaryono, 2023). It is directed towards understanding and solving problems, evaluating alternatives, and decision-making (Campo et al., 2023). Dwyer et al. (2014) define critical thinking as “a metacognitive process, that consists of sub-skills such as: analysis, evaluation, and inference which, if used appropriately, increase probabilities for arriving at logical solutions to a problem.

Prawat (1991) indicated that a common goal of most educators was to improve students' higher order thinking skills. The immersion approach according to Prawat (1991), helped students deeply understand the content and promoted higher-order thinking. In other words, immersion enhanced critical and creative thinking.

1.3.3. Creative Thinking (CRET)

CRET refers to the ability to produce original and appropriate work that is useful and adaptive for the task constraints. It is the ability to rearrange the existing ideas in new combinations to come up with a new design (Sternberg & Lubart, 1998). According to Usha (2009), it is the ability to conceive an innovative idea and verify its validity with scientific reasoning. Some problems require creative thinking and cannot be solved based on scientific reasoning alone. Creativity can be improved over time by enhancing specific skills and knowledge, and a stimulating environment for individuals’ cognitive processes and personality factors, including motivations.

Lindberg et al. (2017) suggested that individual skills and motivation, as well as the external environment are essential for producing creative work. They suggested that giving students chances to learn specific skills, encourages creativity.

To conclude, there is evidence that HoM and cognitive learning outcomes in biology are affected by learning processes (Ariyati et al., 2024). Therefore, a focus on the components of SR, CRIT, and CRET is required by educators and teachers to get insights into the cognitive and metacognitive skills of students’ HoM and enhance it accordingly.

1.4. Mediating Variables:

1.4.1. Flow Experience

FE is a self-reinforcing cycle of energy, motivation, and personal growth (Mirvis & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). It is a state of complete immersion and optimal experience in an activity. It is characterized by a high level of concentration, a sense of control, a merging of action and awareness, and an intrinsic enjoyment in the task at hand. It creates a case of deep concentration, lack of self-consciousness, a feeling of control over what one is doing, complete focus on the task at hand, and a breakthrough in performance (Guerra-Tamez et al., 2021). It is a general phenomenon that is not exclusive to specific activities and therefore not limited to mere intrinsically motivated activities (Mahnke et al., 2012). When engaged in an activity, students may become so completely absorbed that they lose track of time, their surroundings, and everything else except the task at hand (E. Lee, 2005). The Flow Experience refers to the set of elements such as the sense of absorption in the activity, the right level of challenge, the lack of perception of time passing, and the spontaneity of thoughts and actions (Macchi & De Pisapia, 2024).

Macchi & De Pisapia (2024) hypothesized that VRI enhances higher levels of flow caused by its immersive and stimulating nature. VR is potential to bring about ‘flow’ through introducing the element of perceived challenge.

1.4.2. Motivation (MT)

MT is a driving force in the form of a strong desire, will, or tendency to achieve the highest level of success through high quality work (Lase & Noibe Halawa, 2024). Motivation is a critical part of success in education and later life. Thompson et al. (2022) noted that higher degree of self-efficacy appears to be positively associated with students’ attitudes towards learning. Effective instruction has the potential to boost self-efficacy, represented as ‘confidence’, when listening to authentic lectures. In the process of teaching and learning, the motivational variable has a potentiating effect on students’ learning. Motivation gives reasons for people's actions, desires, and needs to obtain the objective of learning. Learners’ motivation is probably one of the most important elements for learning which is inherently hard work. Learning is pushing the brain to its limits and thus can only happen with motivation (Filgona et al., 2020). Motivation can be either intrinsic or extrinsic. IMT happens when motivation is caused by inherent satisfaction or enjoyment of the activity or a desire to feel better (Zeng et al., 2022).

1.4.3. Self-Regulation as a mediator for Critical Thinking and Creative Thinking

According to Ariyati and Fitriyah (2024), SR has a significant influence on controlling students' emotions, thoughts, and actions therefore, self-regulated students will have metacognitive skills that can enhance students’ CRIT and CRET.

Hyytinen et al. (2021) concluded that SR is crucial to CRIT, and a function that guides this complex thinking process. SR refers to an intentional and adaptive process that allows students to plan, adapt, and monitor their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to the demands of the task. Akcaoğlu et al. (2023) believe that SR is related to metacognitive skills in that it determines the methods and timing for planning, monitoring and evaluation processes that will be carried out. Lee (2009) examined the relationships between metacognition, SR and CRIT in an experimental study and found out that SR is a significant predictor of students’ CRIT dispositions. In another study about ‘EFL learners' SR, CRIT and language achievement’, Ghanizadeh and Mizaee (2012) found that the enhancement of SR strategies leads to the development of CRIT abilities.

Another study that explored the predictive power of SR and academic hope in CRET among undergraduate students, Ghbari and Harahsheh (2024) found that SR is a good predictor of CRET. They recommended considering students’ SR to foster CRET.

1.5. Research Objective and Questions

The objective of this study is to examine the impact of VRI-based Biology classes, on East Jerusalem High school students’ HoM mediated by MT, FE, and SR.

Based on the above, the following research questions have been formulated:

RQ1: Are there statistically significant direct effects of VRI as a method of teaching biology on students’ HoM?

RQ2: Are there statistically significant indirect effects of VRI as a method of teaching biology on students’ HoM through the mediation of FE, MT and SR?

1.6. Problem statement

The number of high school students enrolling in the scientific stream in Palestine is linked to the limitations of traditional teaching methods in explaining abstract scientific concepts according to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (2010, 2021). VRI offers a potential solution by enhancing engagement, cognitive skills, and scientific thinking (Elmqaddem, 2019; Ochs & Sonderegger, 2022). VR facilitates experiential learning by transforming abstract concepts into immersive experiences, increasing MT and SR, and fostering habits of mind (HoM) essential for scientific thinking (Mills & Fullagar, 2008; Solmaz et al., 2024). However, the impact of VRI on HoM hasn’t been sufficiently examined. This study investigates how VRI enhances HoM by improving students’ engagement and fostering their CRIT and CRET, ultimately encouraging more students to pursue the scientific stream.

1.7. Study Hypotheses

VRI-based biology classes directly enhance students’ HoM:

1.7.1. Direct-effect relationships:

H1a: Higher levels of VRI directly enhance CRIT.

H1b: Higher levels of VRI directly enhance SR.

H1c: Higher levels of VRI directly enhance CRET.

H1d: Higher levels of VRI directly enhance FE.

H1e: Higher levels of VRI directly enhance MT.

H2: FE directly enhances MT.

H3: MT directly enhances SR.

H4a: SR directly enhances CRIT.

H4b: SR directly enhances CRET.

One the other hand, VRI-based biology classes can indirectly enhance students’ HoM though primary (one mediator), secondary (Two mediators), or tertiary (three mediators):

1.7.2. Primary Mediation Hypotheses (One Mediator)

H5: The relationship between VRI and SR is partially mediated by MT.

H6a: The relationship between VRI and CRIT is partially mediated by SR.

H6b: The relationship between VRI and CRET is partially mediated by SR.

H7: The relationship between VRI and MT is partially mediated by FE.

H8: The relationship between FE and SR is partially mediated by MT.

H9a. The relationship between MT and CRIT is partially mediated by SR.

H9b. The relationship between MT and CRET is partially mediated by SR.

1.7.3. Secondary Mediation Hypotheses (Two Mediator)

H10a: VRI enhances CRIT through MT and SR.

H10b: VRI enhances CRET through MT and SR.

H11: VRI enhances SR through FE and MT.

H12a: FE enhances CRIT through MT and SR.

H12b: FE enhances CRET through MT and SR.

1.7.4. Tertiary Mediation Hypotheses (Three Mediator)

H13a: VRI enhances CRIT through FE, MT, and SR.

H13b: VRI enhances CRET through FE, MT, and SR.

VRI affects HoM (CRIT and CRET) mediated by FE, MT, and SR. Direct and Indirect relationships were based on different theoretical frameworks and empirical studies. VRI is grounded in theories of immersive learning such as CAMIL which adopts a constructivist view of learning by emphasizing the central role of immersion and engagement during VRI instruction. FE as a mediator between VRI and HoM and between VRI and MT was based on Csikszentmihalyi (2000) theory of flow. FE emphasizes that immersed learners enjoyably fall in complete absorption in what they are performing, a state derived from enjoyment and engagement. MT resulting from autotelic nature of performance which generates the state of flow according to Csikszentmihalyi (2000), explained how VRI and flow add to the levels of MT according to Deci and Ryan (1985). The dual role of SR as the final sequential mediator and part of HoM variables is a key variable in the study. HoM encompassing (SR, CRIT, and CRET) as the dependent variables of the study were grounded in Marzano et al. (1993) most important five life-long dimensions of learning.

Locke (1987) in his Social Cognitive Theory explained how SR functions as a mediator between the components in triadic reciprocal causation model: personal factors, behavioral patterns and environmental influences. This enhances the ability for SR to function as a sequential mediator between VRI and HoM.

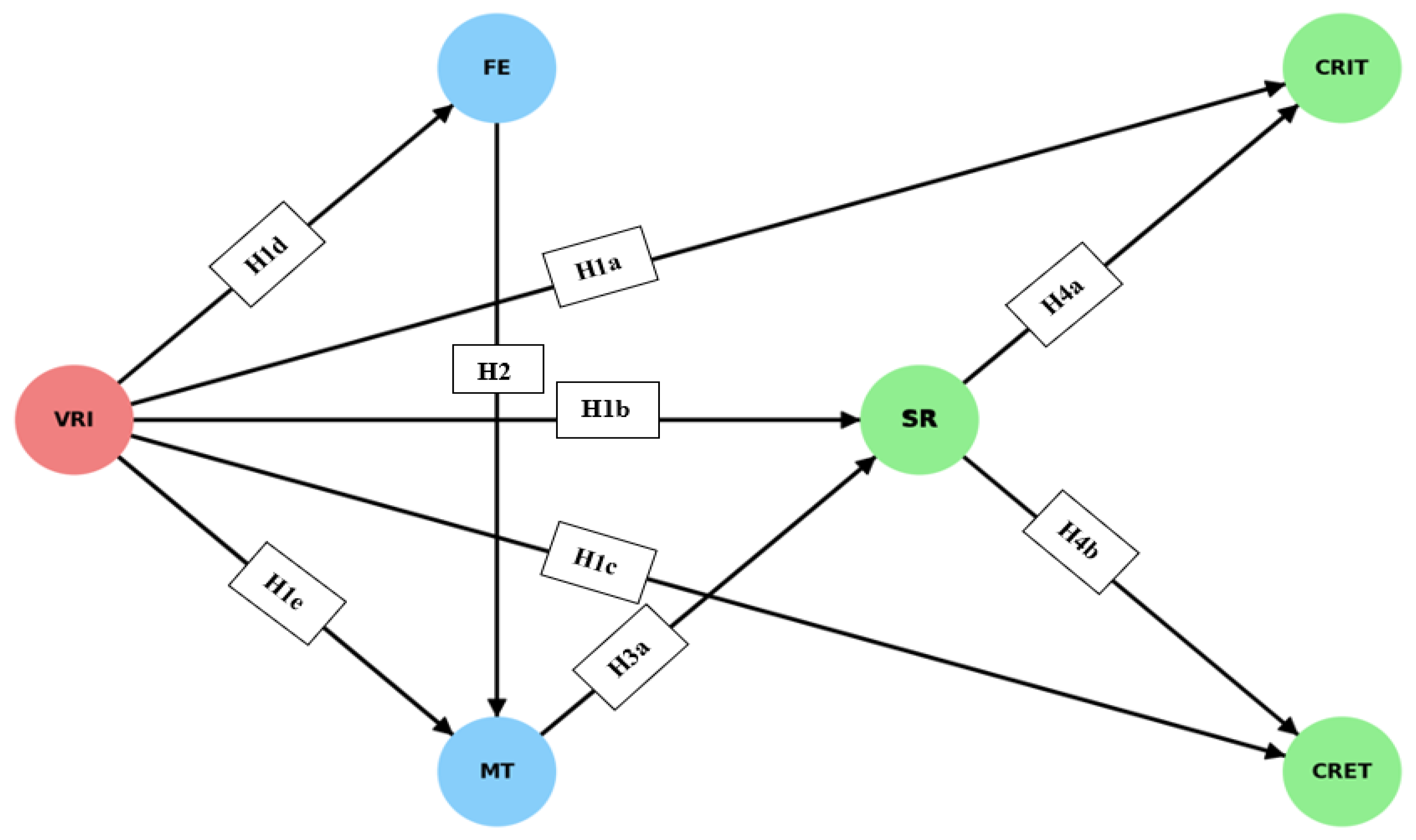

The following figure depicts the conceptual model for the proposed relationships between the independent variable VRI and the dependent variable HoM mediated by flow experience, motivation and self-regulation:

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

This quantitative quasi-experimental sequential explanatory study is designed to allow for the explanation of the questions of the study, and the exact nature of the relationships in the SEM that causes VRI to enhance students' HoM directly or indirectly through FE, MT and SR during biology classes. The following describes the research design and procedures:

2.2. Study Tools

A comprehensive questionnaire used a Likert scale with five answer choices namely, strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree, combined three validated tools to measure the different constructs related to the study:

The independent construct VRI: Schubert et al. (2001) validated Igroup Presence Questionnaire – Short (IPQ-S) to measure students’ level of immersion during biology classes.

The dependent constructs of HoM (SR, CRIT and CRET): The study employed a validated questionnaire of HoM developed by Sriyati et al. (2011) and based on Marzano (1992) and Marzano et al. (1993) habits of mind.

The mediating variables (FE and MT): Guerra-Tamez (2023) validated and advanced questionnaire of FE and MT that measures the partial effects of the mediating variables FE and MT on HoM was adopted.

Table 1.

Constructs and their items adapted from previous studies.

Table 1.

Constructs and their items adapted from previous studies.

| Construct |

Abb |

# |

Item |

|

| Immersion VR |

VRI |

1 |

I felt that I had a sense of being there. (SP) |

(Schubert et al., 2001) |

| 2 |

I felt that VR world surrounded me. (SP) |

| 3 |

I was completely captivated by the virtual world. (INV) |

| 4 |

I was aware of my real environment during the experience. (INV) |

| 5 |

The virtual world seemed very realistic to me. (ER) |

| 6 |

I felt the objects in the virtual world looked realistic. (ER) |

| Flow Experience |

FE |

1 |

Enjoy experience through VR technology. |

(Guerra-Tamez, 2023) |

| 2 |

I found the gratifying VR experience. |

| 3 |

I felt in total concentration during the experience. |

| 4 |

I felt that time passed too fast. |

| 5 |

This class through VR technology exceeds my expectations. |

| Motivation |

MT |

1 |

It is interesting to use VR technology in class. |

| 2 |

My performance was good using VR technology in class. |

| 3 |

After using VR technology for a while, I felt competent. |

| 4 |

I was very relaxed while using VR technology in class. |

| 5 |

I am skilled while I use VR technology in class. |

| Self-Regulation |

SR |

1 |

Recognizing self-thinking |

(Sriyati et al., 2011) |

| 2 |

Making effective plans |

| 3 |

Understanding and using the needed information |

| 4 |

Becoming sensitive toward feedback |

| 5 |

Evaluating the effectiveness of acts |

| Critical Thinking |

CRIT |

1 |

Being accurate and able to look for accuracy |

| 2 |

Being clear and able to look for clarity |

| 3 |

Being open |

| 4 |

Being able to position oneself when there is a guarantee |

| 5 |

Being sensitive and able to recognize friends’ abilities |

| Creative Thinking |

CRET |

1 |

Being able to involve oneself in tasks although the answer and solution has not yet to be found |

| 2 |

Trying hard to expand skills and knowledge |

| 3 |

Creating new ways or point of view outside the common knowledge |

2.2.1. Validity and Reliability

Validity of the combined questionnaire was maintained through expert reviews and pilot testing, ensuring that the instrument accurately measured the intended constructs. Reliability tests, such as Cronbach's alpha, were conducted to confirm the consistency of the combined tool.

2.2.2. Translation Process

The final English form of the questionnaire including a 29-items was translated into Arabic by two competent English teachers to make sure about suitability of the Arabic form to meet the level of high-school students. A competent Arabic teacher revised the translation, then a back translation was performed by a fourth English teacher. A pilot test of the final form of the tool was conducted on a small representative sample from different schools and grade levels to check the clarity, difficulty and appropriateness of the items. Finally, some minimal changes on the final Arabic form of the tool were made based on feedback given from the pilot group.

2.3. Study Context

The experiment was exclusively conducted on East Jerusalem government High School Students based on random cluster sampling.

East Jerusalem government high schools adopt either the Palestinian curriculum (tawjihi) where schools are usually separated based on gender (either male or female) and include three stages: 10th to 12th grades. Schools adopting the Israeli curriculum (Bagrut), on the other hand, are usually mixed and include four stages: 9th – 12th grades. Nevertheless, coursebooks of both types of schools present the same biology content with little variations. This study aims for the schools adopting the Palestinian curriculum, therefore, a random stratified sample to ensure that subgroups are proportionally represented was derived from schools that follow the (taujihi) curriculum.

2.3.1. Study Sample:

The sample included 349 students taught by 4 biology teachers from 3 different high schools (2 male and 1 female school) from East Jerusalem schools were randomly chosen for the experiment. Biology teachers (2 male and 2 female) of the sample were all highly qualified with a BA degree in Biology and an MA degree in methods of teaching science and an experience of more than ten years of teaching biology for high school students.

Table 2.

Demographic information of the sample (initials are fictive).

Table 2.

Demographic information of the sample (initials are fictive).

| School |

Grade |

School Gender |

# of Students |

# of |

| Group |

| Shu’fat Comprehensive School |

10th

|

M |

72 |

2 |

| 11th

|

50 |

2 |

| 12th

|

67 |

2 |

| Beit Hanina Secondary School |

10th

|

F |

30 |

1 |

| 11th

|

30 |

1 |

| 12th

|

30 |

1 |

| Al Mutanabbi Comprehensive School |

10th

|

M |

32 |

1 |

| 11th

|

22 |

1 |

| 12th

|

16 |

1 |

| Total |

|

349 |

12 |

VR biology classes were planned according to the principles of constructivis. This is believed to enhance HoM, especially SR, CRIT and CRET (Kurt & Sezek, 2021; Pande & Bharathi, 2020, 2020). A general framework of lesson plans was followed by all participating groups included: topic introduction, VR interaction, discussion, application activities, and lesson summarization. Biology teachers selected complex and abstract topics for VR instruction, aiming to improve student comprehension.

Groups of 20–34 students attended 50-minute sessions using Meta Quest 3 VR sets. The content was sourced from coursebooks and platforms like www.youtube.com and/or www.mozaweb.com.

2.3.2. Data Collection

The final Arabic form of the questionnaire as a google form with obligation to answer all the fields except for the name was sent to the participating biology teachers in different schools at the end of the experiment. Biology teachers sent the questionnaire to the participating groups via WhatsApp groups which were created for the experiment. 347 participants out of 349 successfully submitted the questionnaire. Data was stored, ensuring the anonymity of the participants and confidentiality of information.

2.3.3. Data Analysis

To allow examining the complex cause-effect relationships between different constructs of the study, Partial Least Squares (PLS4) statistical software, which is designed for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed. The software combines factor analysis and multiple regression analysis, maximizing the explained variance of the dependent variable to enable more general representations of measurement and latent variable models. SEM is a robust statistical method used to examine hypotheses regarding the causal relationships between both observed and latent variables (Sarstedt et al., 2022).

These methods helped in analyzing quantitative data and interpreting the relationships between the variables.

3. Results

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to assess both the direct and indirect effects of VRI on HoM through FE, MT and SR as sequential mediating variables. PLS is an effective software for analyzing complex relationships with mediating variables. The analysis aims to test the hypothesized model and evaluate the predictive relevance of the constructs.

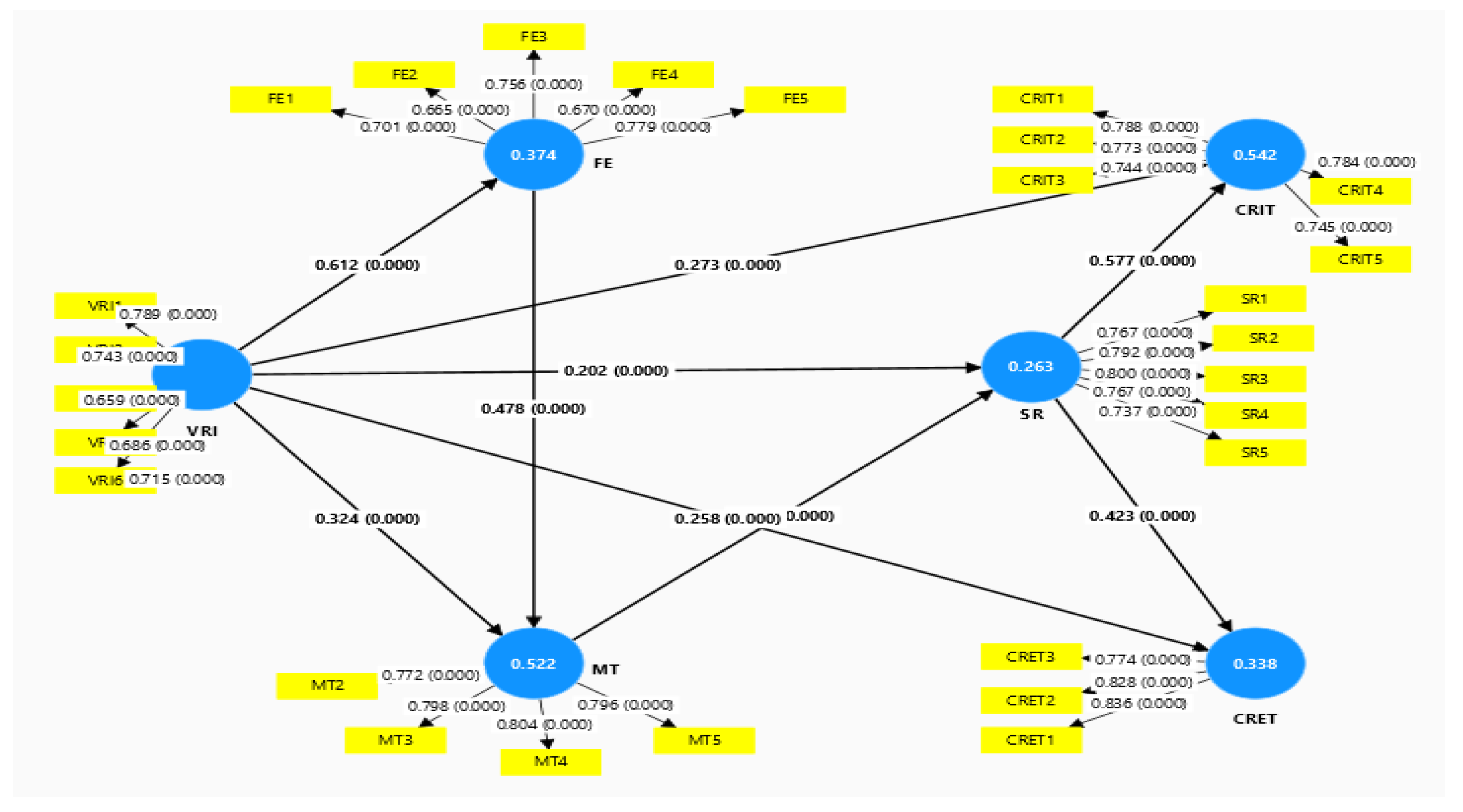

Figure 2.

Results of the conceptual model.

Figure 2.

Results of the conceptual model.

3.1. Measurement of Model Assessment

To ensure that the observed indicators reliably and validly measure the latent constructs, validity and reliability were examined.

3.1.1. Reliability and Convergent Validity

To assess the measurement model and internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability were examined.

Table 4.

Reliability and Convergent Validity.

Table 4.

Reliability and Convergent Validity.

| Variable |

Cronbach’s α |

Rho_a |

Rho_c |

AVE |

p |

| CRET |

0.74 |

0.75 |

0.85 |

0.66 |

0.00 |

| CRIT |

0.83 |

0.83 |

0.88 |

0.59 |

0.00 |

| FE |

0.76 |

0.77 |

0.84 |

0.51 |

0.00 |

| MT |

0.8 |

0.81 |

0.87 |

0.63 |

0.00 |

| SR |

0.83 |

0.83 |

0.88 |

0.6 |

0.00 |

| VRI |

0.77 |

0.77 |

0.84 |

0.52 |

0.00 |

Constructs of the study showed acceptable consistency with Cronbach's alpha values > 0.65 except for two: (VR4 = 0.271 and MT1 = 0.549) therefore, they were deleted (Hair et al., 2019). Composite reliability values ranged between 0.75 and 0.83, indicating good consistent measures of the constructs (Hair et al., 2019). Convergent validity was also supported by the average variance extracted (AVE) for different constructs which were higher than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2019).

3.1.2. Discriminant Validity

HTMT ratio and Fornell-Larcker criterion were used to check the uniqueness of the constructs of the study:

Table 5.

HTMT and Fornell-Larcher Criteria for Discriminant Validity.

Table 5.

HTMT and Fornell-Larcher Criteria for Discriminant Validity.

| Variable |

CRET |

CRIT |

FE |

MT |

SR |

VRI |

| CRET |

0.81 |

0.84 |

0.46 |

0.51 |

0.67 |

0.57 |

| CRIT |

0.66 |

0.77 |

0.51 |

0.60 |

0.83 |

0.65 |

| FE |

0.36 |

0.41 |

0.72 |

0.85 |

0.48 |

0.80 |

| MT |

0.4 |

0.49 |

0.68 |

0.79 |

0.60 |

0.78 |

| SR |

0.53 |

0.69 |

0.39 |

0.49 |

0.77 |

0.53 |

| VRI |

0.44 |

0.52 |

0.61 |

0.62 |

0.43 |

0.72 |

The result supported the robustness of the measurement model and confirmed that each latent variable represents a unique construct, free from significant overlap with other variables.

3.2. Structural Model Assessment

3.2.1. Model fit

Bollen-Stine bootstrapping was conducted to check model fit (Bollen & Stine, 1992).

Bollen-Stine test showed a small discrepancy (< 0.08) between observed and predicted correlations (Bollen & Stine, 1992).

3.2.2. Collinearity Assessment (VIF Values)

Values of VIF according to Hair et al. (2019) should be close to 3 or below. Results of multicollinearity at the construct level ranged between (1.309 – 1.733) < 3.3 indicating low multicollinearity among all predictor variables and their ability to contribute independently in explaining the variance of the dependable variables (Hair et al., 2019). This supports the HTMT and Fornell-Larcker results by providing additional evidence that the constructs are distinct, despite the high correlation between CRET and CRIT.

3.2.3. Path Coefficients: (Direct Effects and Hypotheses Testing):

Results of path coefficients reflect the strong and positive relationships between constructs of the study.

Table 10 summarizes the results:

Table 6.

Direct Effects.

| Path |

H # |

β |

t |

p |

| VRI → CRIT |

H1a |

0.27 |

7.07 |

0.00 |

| VRI → SR |

H1b |

0.20 |

3.55 |

0.00 |

| VRI → CRET |

H1c |

0.26 |

5.11 |

0.00 |

| VRI → FE |

H1d |

0.61 |

13.77 |

0.00 |

| VRI → MT |

H1e |

0.32 |

6 |

0.00 |

| FE → MT |

H2 |

0.48 |

8.56 |

0.00 |

| MT → SR |

H3 |

0.36 |

6.61 |

0.00 |

| SR → CRIT |

H4a |

0.58 |

14.11 |

0.00 |

| SR → CRET |

H4b |

0.42 |

8.33 |

0.00 |

All direct effects were positive and significant (Hair et al., 2021) where:

β < 0.10 → Small effect

0.10 ≤ β < 0.30 → Moderate effect

β ≥ 0.30 → Strong effect

All p-values (p < 0.05) and all t-values for all direct pathways were mainly higher than 1.96: (t > 1.96, p = 0.00) which supported the significance and strength of the reported paths. Hence, all direct hypotheses (H1a – H4b) were positive and significantly effective. This answered the study RQ1:

Are there statistically significant direct effects of VRI as a method of teaching biology on students’ HoM?

PLS-SEM analysis confirmed that VRI directly impacts students CRIT, SR, and CRET which was evidenced by the moderate positive significance of H1a, H1b, and H1c.

However, further analysis of direct effects of VRI on mediators reflected stronger effects:

H1d: The direct effect of VRI on FE (β = 0.61, t = 13.768, p < 0.05) revealed a strong, positive, significant direct effect. Immersion through VR during biology classes, strongly enhanced students’ flow experience. Hence, H1d was supported.

H1e: The direct effect of VRI on MT (β = 0.32, t = 6, p < 0.05) also revealed a strong effect of VRI on students’ motivation.

Other direct effect hypotheses: H2: FE → MT (β = 0.48, t = 8.56, p < 0.05) and H4: MT → SR (β = 0.36, t = 6.61, p < 0.05), H4a: SR → CRIT (β = 0.58, t = 14.11, p < 0.05) and H4b: SR → CRET (β = 0.42, t = 0.322, p < 0.05) were all strong and significant. Hence, they were all supported.

Absence of significant relationships between FE → SR, or FE → CRIT/CRET, or MT → CRIT/CRET, highlighted the role of sequential mediators FE, MT, and SR in enhancing the total effects of VRI on HoM. It also underscored the crucial effect of SR as the final sequential mediator in transmitting the effects of VRI on CRIT/CRET through mediators. This required examining the role of mediation through indirect effects.

3.2.4. Total Indirect Effects

To evaluate indirect effects of VRI on CRIT and CRET through mediators FE, MT and SR, analysis of indirect pathways was conducted:

3.2.5. Indirect effects (Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary)

Table 7.

Indirect-effect Hypotheses.

Table 7.

Indirect-effect Hypotheses.

| Primary Indirect Effects |

| |

H |

β |

T |

P |

|

VRI→MT→SR

|

H5 |

0.12 |

4.74 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→SR→CRIT

|

H6a |

0.12 |

3.49 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→SR→CRET

|

H6b |

0.09 |

3.37 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→FE→MT

|

H7 |

0.29 |

7.22 |

0.00 |

|

FE→MT→SR

|

H8 |

0.17 |

4.96 |

0.00 |

|

MT→SR→CRIT

|

H9a |

0.21 |

5.62 |

0.00 |

|

MT→SR→CRET

|

H9b |

0.15 |

5.00 |

0.00 |

| Secondary Indirect Effects |

|

VRI→MT→SR→CRIT

|

H10a |

0.07 |

4.42 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→MT→SR→CRET

|

H1b |

0.05 |

4.28 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→FE→MT→SR

|

H11 |

0.11 |

4.57 |

0.00 |

|

FE→MT→SR→CRIT

|

H12a |

0.10 |

4.43 |

0.00 |

|

FE→MT→SR→CRET

|

H12b |

0.07 |

3.98 |

0.00 |

| Tertiary Indirect Effects |

|

VRI→FE→MT→SR→CRET

|

H13a |

0.05 |

3.78 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→FE→MT→SR→CRIT

|

H13b |

0.06 |

4.14 |

0.00 |

3.2.5.1. Primary indirect effect hypotheses

The seven primary mediated pathways have positive significant effects that ranged between weak to moderate magnitudes:

H5: VRI → MT → SR (β_indirect = 0.12, p < 0.05; β_direct = 0.20, p < 0.05). VRI influences SR directly and indirectly through the partial mediation of MT. The total effect of VRI on SR is β = 0.32 indicating that while motivation is an important mediator, VRI still has a notable direct impact on SR. Therefore, H5 is supported.

H6a. VRI → SR → CRIT (β_indirect = 0.12, p < 0.05; β_direct 0.27, p < 0.05) and H6b: VRI → SR → CRET (β_indirect = 0.09, p < 0.05; β _direct = 0.26, p <0.05). H6a and H6b were both supported. VRI affects students’ critical thinking and creative thinking both directly and indirectly through the partial mediation of SR. The total effect of VRI on CRIT (β = 0.39) and on CRET (β = 0.35), indicate that while part of the effect occurs directly, a meaningful portion is explained through SR.

H7: VRI → FE → MT (β_indirect = 0.29, p < 0.05; β_direct = 0.32, p < 0.05). Hence, H7 was supported. VRI influences students’ MT both directly and indirectly via the partial mediation of FE.

H8, H9a, H9b were supported as having full mediating effect. H8: FE → MT → SR for example, the path FE → SR was not significant (p > 0,05) implying that FE can only affect SR through MT indicating a full mediation case of MT. The indirect path via MT (β = 0.17, t = 4.957, p < 0.05) reflects a moderate indirect magnitude of FE on SR through full mediation of MT. Therefore, H8, H9a and H9b were supported. FE can not directly enhance SR. FE enhances students’ MT which fully mediates the relationship between FE and SR.

3.2.5.2. Secondary indirect effects (Two mediators):

Five pathways in the model included two mediators:

Five pathways in the model included two mediators:

H10a: VRI → MT → SR → CRIT and H10b: VRI → MT → SR → CRET: The direct effects of VRI on CRIT (β = 0.27, t = 7.07, p < 0.05) and on CRET (β = 0.26, t = 5.11, p < 0.05). However, VRI has a small significant partial indirect effect on CRIT through MT and SR (β = 0.05, t = 4.275, p < 0.05) and on CRET (β = 0.05, t = 4.275, p < 0.05). The total significant effect of the direct and indirect paths (β = 0.32, p < 0.05) and (β = 0.31, p < 0.05) revealed a strong significant partial effect of VRI on CRIT and CRET through the mediators MT and SR. Therefore, H10a and H10b were supported.

H11: VRI → FE → MT → SR. The direct effect of VRI on SR (β = 0.20, t = 6.002, p < 0.05) was enhanced by the indirect path FE → MT (β = 0.11, t = 4.57, p < 0.05): This path also resulted in a strong indirect effect of VRI on SR partially mediated by FE→ MT. (β = 0.31, t = 6.002, p < 0.05)

3. H12a and H12b: FE → MT → SR → CRIT/CRET. Results revealed a small indirect effect of FE through the sequence of mediators MT → SR on CRIT/CRET. Therefore, mediation can be classified as full. This indicates that FE cannot directly affect CRIT and CRET, but rather enhances students’ MT, which subsequently improves their SR, ultimately leading to enhanced CRIT. Therefore, H12a and H12b are supported.

Analysis of secondary pathways explained the mechanisms of sequential mediation of FE → MT → SR, emphasizing the role of SR as the only and final channel through which indirect effects of VRI can affect CRIT and CRET.

3.2.5.3. Tertiary indirect effects (three mediators):

There are two cases of tertiary mediation between VRI and HoM (CRIT/CRET). Both pathways reflected a small but significant impact on CRET: (H27: β = 0.05, t = 3.778, p < 0.05) and on CRIT (H28: β = 0.06, t = 4.139, p < 0.05). Therefore, (H13a and H13b) were supported. These indirect significant effects of VRI on CRIT/CRET though small, it provides a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which mediators function sequentially and underscore the crucial function of SR as the final sequential mediator.

Iindirect-effect analysis revealed that VRI significantly enhances HoM through the sequential mediators (FE→ MT→ SR). The strongest indirect effect is VRI → SR → CRIT (β = 0.25, p < 0.05), confirming the key mediating role of SR.

3.2.6. Total Effects

The impact of both direct and indirect effects together on the dependent variables in the model reflected a comprehensive view of the strength of the different pathways in the model connecting between endogenous VRI and exogenous variables.

Table 8.

Total Effects.

| |

β |

T |

P |

|

VRI→CRET

|

0.44 |

9.59 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→CRIT

|

0.52 |

12.71 |

0.00 |

|

VRI→SR

|

0.43 |

9.57 |

0.00 |

The total effects of VRI on CRIT (β = 0.52), on CRET (β = 0.44) and on SR (β = 0.43) were significantly stronger that the direct effects VRI → CRIT (β = 0.27), VRI → CRET (β = 0.26) VRI → SR (β = 0.20) which highlights the crucial role of mediators in enhancing the total effects. Amplifying the total effects into strong highlight the critical effect caused by sequential mediators FE, MT, and SR in developing higher cognitive skills such as CRIT and CRET.

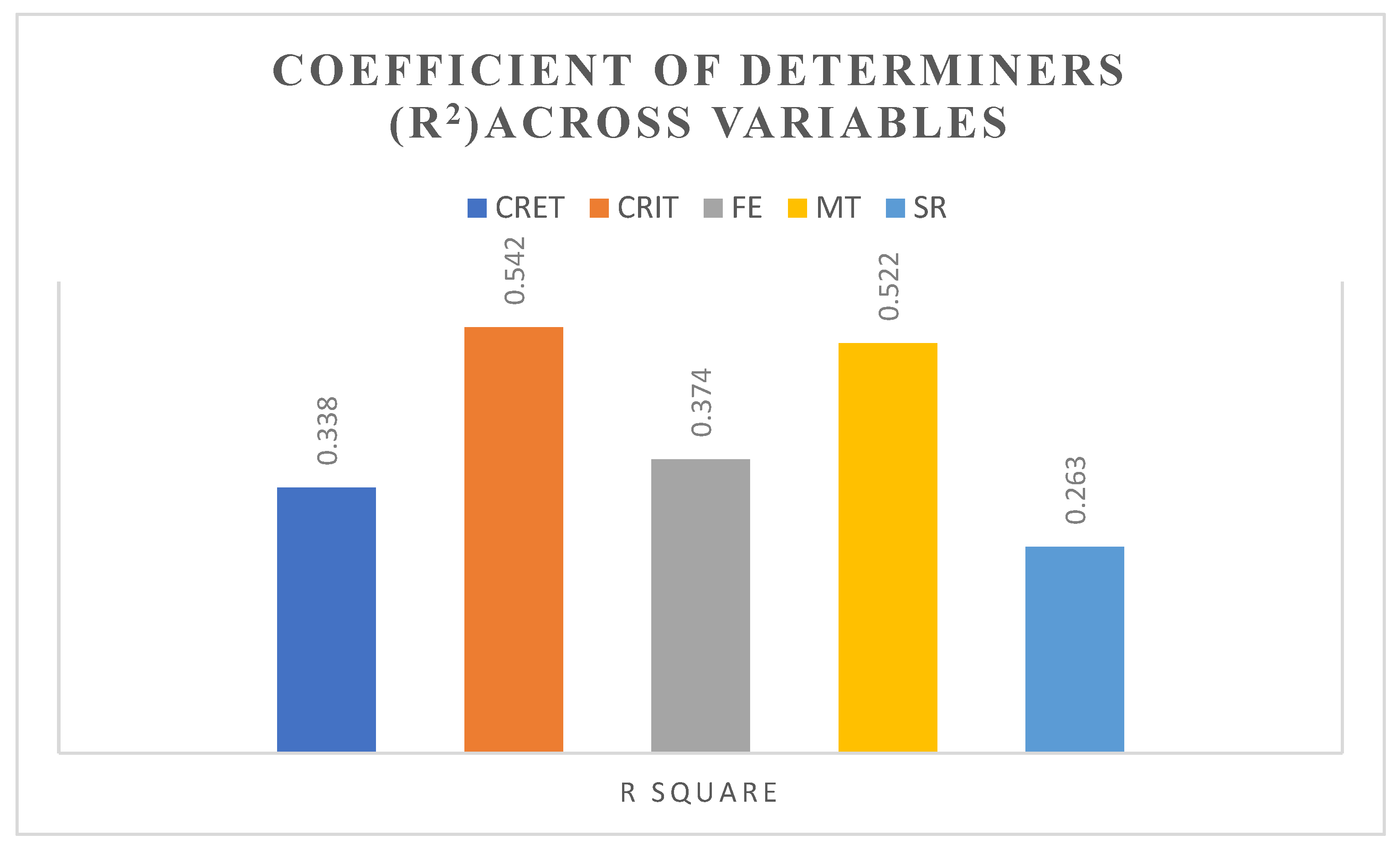

3.2.7. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

Effectiveness of the ability of the independent variable to explain the variance in the dependent variables in the study ranged between small and large.

Figure 3 illustrates the results of R

2:

According to Cohen (1988), R2 values of 0.02, 0.13, and 0.26 corresponds to small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. These criteria are widely used in social and behavioral sciences for evaluating the explanatory power of models. Based on (Cohen, 1988) these criteria:

CRIT and MT demonstrate a moderate to large explanatory power, highlighting the model's effectiveness in predicting these variables.

CRET and FE fall within the medium effect size range, suggesting that while the predictors provide a reasonable level of explanation for CRET and FE, additional factors might enhance their explanatory power.

SR (0.26) meets Cohen’s threshold for a large effect size, implying that its variance is meaningfully explained by the predictors.

The results indicate that the model provides strong explanatory power for CRIT and MT, while CRET, FE, and SR show moderate to strong predictive capabilities based on Cohen's (1988) benchmarks.

3.2.8. Predictive Relevance Q2 and Model Accuracy

All constructs of the current study have Q2 > 0 confirming the model’s predictive relevance. Results of comparing the RMSE values with LM values showed that the majority of indicators yielded smaller prediction errors compared to LM, indicating a medium predictive power (Shmueli et al., 2016). This validates the model’s predictive capability for most constructs.

Table 9.

Q²predict and PLS predict MV.

Table 9.

Q²predict and PLS predict MV.

| Construct |

Q² Predict (Overall) |

PLS Predict (Q² Predict for Items) |

PLS Predict RMSE |

LM RMSE |

Interpretation |

| CRET |

0.19 |

0.154 (CRET1), 0.103 (CRET3) |

0.904,

0.861 |

0.72 |

Medium predictive power, moderate error |

| CRIT |

0.26 |

0.177 (CRIT4), 0.133 (CRIT1) |

0.774,

0.775 |

0.68 |

Large predictive power, low error |

| FE |

0.37 |

0.277 (FE3), 0.143 (FE4) |

0.783,

0.926 |

0.62 |

Large predictive power, low error |

| MT |

0.37 |

0.277 (MT3), 0.179 (MT2) |

0.72,

0.736 |

0.60 |

Large predictive power, lowest error |

| SR |

0.17 |

0.147 (SR4), 0.051 (SR5) |

0.857,

0.745 |

0.73 |

Medium predictive power, high error |

All constructs of the current study have Q2 > 0 confirming the model’s predictive relevance. Results of comparing the RMSE values with LM values showed that the majority of indicators yielded smaller prediction errors compared to LM, indicating a medium predictive power (Shmueli et al., 2016). This validates the model’s predictive capability for most constructs.

The results of comparing the RMSE (or MAE) values with LM values showed that the majority of indicators yielded smaller prediction errors compared to LM, indicating a medium predictive power (Shmueli et al., 2016). Only FE1, FE5, MT4, and SR5 yielded larger prediction errors.

Though the model requires minor refinements to elevate indicators with small to moderate predictive power or from moderate to strong, predicative relevance analysis highlighted the practical applicability of the model through its meaningful predicative ability. This aligns with the study’s goal in structuring a framework to explain the effects of VRI on HoM (CRIT and CRET) through a series of mediators (FE → MT → SR). Hence, RQ1 and RQ2 are further supported as the model explains a significant variance in HoM validated by effect sizes and predictive power.

3.2.9. Effect Size (f2)

Effect size (f2) is a measure of the relative impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable in (PLS-SEM). It quantifies how much an exogenous (predictor) variable contributes to explaining the variance of an endogenous (outcome) variable when added to the model.

Table 10.

Effect Size (f2).

Table 10.

Effect Size (f2).

| |

f² |

T |

P |

Power |

|

FE→MT

|

0.3 |

3.29 |

0.00 |

Large |

|

MT→SR

|

0.11 |

2.85 |

0.00 |

Medium |

|

SR→CRET

|

0.22 |

3.34 |

0.00 |

Medium |

|

SR→CRIT

|

0.59 |

4.59 |

0.00 |

Large |

|

VRI→CRET

|

0.08 |

2.36 |

0.02 |

Small |

|

VRI→CRIT

|

0.13 |

3.33 |

0.00 |

Medium |

|

VRI→FE

|

0.6 |

4.13 |

0.00 |

Large |

|

VRI→MT

|

0.14 |

2.69 |

0.01 |

Medium |

|

VRI→SR

|

0.03 |

1.64 |

0.01 |

Small |

Table 10 summarizes the effects based on (Cohen, 2013):

According to (Cohen, 2013), values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 correspond to small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. The table shows that f² results for the model explain the variance of the dependent variables. FE and MT (f² = 0.3) indicates that FE has a medium contribution in explaining MT. MT has a small significant contribution to the explanation of SR with an (f² = 0.11). SR can largely contribute to the explanation of CRIT with an (f² = 0.59) but a medium contribution on CRET with an (f² = 0.22).

VRI has a small significant contribution to explaining CRET (f² = 0.08), but it contributes largely to explaining FE (f² = 0.60). Moreover, VRI has a small significant contribution to explaining MT (f² = 0.14). Finally, VRI has a significant small contribution in explaining SR (f² = 0.03).

This suggests that VRI alone may not significantly explain changes in SR directly. Specific indirect analysis showed that mediators such as MT: (VRI → MT → SR) or (VRI → FE → MT → SR) significantly contribute to the explanation of the relationship.

These findings reinforce the importance of mediation effects in the model, supporting RQ2 by demonstrating that VRI indirectly influences HoM through FE, MT, and SR.

4. Discussion

CAMIL provides an explanation of how cognitive immersion through VR affects the final desired outcomes through the provision of interaction and participatory experiences. This encourages learners to engage in learning responsively and develop self-regulatory habits that can finally affect critical and creative thinking by providing chances to solve problems and make decisions according to Tang (2024). This current study examined the impact of VRI on desired scientific habits of mind, namely, SR, CRIT and CRET through a sequence of mediators: FE, MT, and SR. Results of analysis provided valuable insights about the mechanisms through which VRI can effectively enhance higher cognitive skills in education.

4.1. Direct effects of VRI:

Direct-effect results confirmed that VRI-based biology classes have a moderate, direct significant impact on students’ SR, CRIT and CRET. VRI-based biology classes helped overcome the barriers of the traditional teacher-centred classroom environment represented in time, space, danger, cost or accessibility as noted by Solmaz et al. (2024), and provided practical experiences for students. Thus, immersion in the virtual environment allowed students to actively interact with new fundamental biology concepts enhancing learners’ behavioral and cognitive skills. This idea of how immersion helps students deeply understand the content and promote critical and creative thinking aligns with (Kamińska et al. (2019); Solmaz et al. (2024) and (Prawat, 1991).

However, PLS-SEM results reflected strong total effects of VRI on SR, CRIT and CRET resulting from mediators’ intervention.

4.2. Mediation effects

Results of indirect and specific indirect effect analysis revealed the significant indirect enhancement caused by mediators FE, MT, and SR. The absence of direct significant effects of either FE or MT on CRIT/CRET made the final sequential mediator SR function as a harbor through which the effects of FE and MT are significantly transferred to CRIT/CRET. This asserts the findings of Hyytinen et al. (2021) about SR being crucial for fostering CRIT and Ghbari and Harahsheh (2024) about SR as a predictor for CRET, reinforcing the idea that students' ability to regulate their learning plays a crucial role in fostering higher order thinking skills.

4.2.1. The role of FE in fostering MT through VRI

VRI has a strong direct effect on FE (β = 0.61). VRI biology classes caused students to be fully absorbed in the virtual environment of the biology content, enhancing high levels of engagement, and deep concentration corroborating with Mahnke et al. (2012). VRI instruction provided students with immersion and higher levels of engagement which facilitated perception of complex biology concepts constructively supporting the ideas and findings of Marougkas et al. (2023) about immersive learning. Educators can use VRI to introduce complex biology contents to students, to make sure they develop a sense of self-competence about them. This mirrors Thompson et al. (2022), about students highly valuing VRI as an effective instructional method that improved their attitudes towards learning.

Furthermore, FE has a strong direct effect on MT (β = 0.47). Being completely engaged in the virtual environment, students became inherently satisfied and enjoyed interacting with the simulated scenes. This created a type of intrinsic motivation that was caused by the force of flow experience. An improved self-regulation resulted in the form of students’ goal-setting skills, persistence to complete the tasks in hand, and resistance to failure. This corroborates with Thompson et al. (2022) view of VRI as positively associated with students’ positive attitudes towards learning.

4.2.2. The role of MT in enhancing SR

Findings also confirmed the strong impact of VRI on MT (β = 0.32) caused by students’ satisfaction or enjoyment for the sake of the activity itself or for the enjoyment and satisfaction gained from it. This aligns with Zeng et al. (2022) and implies that VRI can generate high levels of MT which enhance SR, and subsequently CRIT and CRET. Educators can plan and implement interactive classes to generate higher levels of motivation that can finally impact their higher order thinking skills.

MT functioned as an intermediary variable in the relationship between VRI and SR which accounted for 53% of the total effect. This emphasized the role of VRI in inducing intrinsic motivation either directly or through FE which, in turn, sparks motivation as inherently enjoyable which directly relates to extrinsic motivation according to Mills and Fullagar (2008) and finally enhances students’ SR.

This final effect of motivation gained directly from both VRI and FE directly affects SR enhancing students’ ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate their own behavior. This echoes (Mitsea et al., 2023; Zimmerman, 2002) about SR as positively related to personal adjustment factors, diligence, and well-adjusted academic behavior. Students then, redirect themselves according to their self-evaluation and as part of adaptation of their learning strategies confirming (Mitsea et al., 2023; Zimmerman, 2002) ideas about SR as judging consistency of actions which enables the learner to adaptively redirect him or herself. This enhanced form of student’s SR directly affects their critical and creative thinking.

4.2.3. The role of SR as a mediator in enhancing CRIT and CRET

SR is the final sequential mediator only through which variables like FE and MT can foster CRIT and CRET. In other words, SR is enhanced directly through VRI and indirectly through the sequence of FE and MT, before it finally transmits the effect into CRIT and CRET. This implies that educators can arrange immersive learning experiences through VRI to generate an enhanced FE, which intrinsically enhances MT. Effects of FE and MT amplify the direct effect of VRI on SR which transfers the amplified total effects to higher order thinking skills. SR, as a cognitive skill that is based on meta skills which enable awareness of one’s thinking, monitoring, and adaptation of learning strategies through cognitive and metacognitive processes Zimmerman (2002), is moderately impacted by VRI through a direct pathway. However, it functions as both: an endogenous variable and as a mediator that transfers the effects of other mediators into critical and creative thinking. This aligns with Zimmerman (2002) view of SR as a self-directed process that enables learners to transform their mental abilities into academic skills. The role of SR as a mediator, predictor, precursor to critical and creative thinking was highlighted in the findings of many recent studies (Akcaoğlu et al., 2023; Ariyati & Fitriyah, 2024; Hyytinen et al., 2021; S. Lee, 2009) confirming the role of SR as a precursor to critical and creative thinking. In addition, according to Costa and Kallick (2000) creating self-directed learners is the goal for teaching HoM. Therefore, educators can employ VRI to enhance SR skills, which significantly predicts the enhancement of higher order thinking skills.

To conclude, analysis reflected that VRI can significantly enhance SR, CRIT and CRET directly and indirectly. While direct effects showed how VRI can moderately impact HoM, total effects reflected a strong impact through the sequence of mediators FE, MT, and SR with SR having the most critical mediating role. This supports that VRI, as grounded in CAMIL theory, helps students gain knowledge constructively through active and interactive methods (Kavanagh et al., 2017) and improve cognitive outcomes.

5. Study Limitations

This study took place in East Jerusalem Municipal High Schools where VR is still in its infancy as an educational tool. Many schools still lack labs designed for VR applications and teachers who are qualified to integrate it professionally into their subject matter. Furthermore, lack of educational applications that suit different grade levels to meet different curriculum designs represented some of the limitations of the study. 3D biology contents had to be chosen carefully before application. In addition, training the participating teachers on how to integrate VR effectively in their classes represented another limitation for the study.

The restricted time for conducting the study and number of VR sets posed another limitation for applying VRI on other biology content which would have enabled more noticeable generalizable results.

Moreover, fostering habits of mind needs a long time to be realized, achieved and internalized as healthy habits of the learners. The experiment lasted for one semester which might not clearly reveal the effects of VRI on students’ self-regulation, critical and creative thinking.

Future research should take these notes into consideration in terms of time, place, applications such as the adoption of longitudinal methodology and the inclusion of other scientific subjects to allow for more generalization of their results.

6. Recommendations

VR, as an interesting and engaging method of teaching, is a promising technological tool having the potential to prepare students who can face the challenges of their age. It can help students acquire and process knowledge intelligently as part of the adaptation process with the technological world. However, the tool is still in its infancy, which necessitates careful considerations of different aspects to ensure active application of the tool and powerful results. Therefore, the following recommendations stem from challenges that faced the present experiment:

Biology teachers are advised to integrate VRI in biology classes, especially when introducing complex foundational concepts to ensure students’ effective and constructive perception.

Teachers should engage in training courses about the integration of VR in their biology classes.

Curriculum designers should reconsider designation of the curriculum based on the principles of CAMIL. Moreover, program engineers should provide suitable VR applications that meet the content of different school subjects for all grades.

Curriculum designers should include activities that allow critical and creative thinking.

7. Conclusion

The study aimed to explore the effects of VRI-based biology classes on high school students HoM, considering the mediating roles of FE, MT, and SR, complying with CAMIL principals. Findings confirmed the positive effects of VRI on enhancing critical and creative thinking through enhancing students’ self-regulatory habits. PLS-SEM statistics reflected the usefulness of VRI in fostering students HoM in biology. A higher level of students’ engagement in virtual biology environments resulted in deeper understanding of complex contents which motivated students to regulate themselves and fostered their CRIT and CRET abilities.

VRI represented a transformative potential of traditional education by creating a student-centered classroom in which students engage actively, enjoyably and responsively in the construction of knowledge. Higher engagement generated higher levels of motivation encouraging students to persist in their tasks and resist failure. Engagement through VR during biology classes created students who are reflective to their thoughts and performance and flexible about adapting their strategies to meet their goals creatively. Clarity and accuracy gained from VR experiences affected students’ clarity and accuracy and encouraged analysis of complex concepts assertively and confidently. Higher engagement and better comprehension encouraged students to go beyond their abilities trying to think divergently by examining different alternatives to come up with creative results.

The study complied with the constructivist principles, especially CAMIL which emphasizes the critical role of learners as being active in constructing their own knowledge. However, VRI proved not only to enhance students’ knowledge, but also to foster their critical and creative thinking through fostering their self-regulatory thinking and learning habits.

References

- Akcaoğlu, M.Ö.; Mor, E.; Külekçi, E. The mediating role of metacognitive awareness in the relationship between critical thinking and self-regulation. Think. Ski. Creativity 2022, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyati, E.; Fitriyah, F.K. An Investigation into Habits of Mind Prospective Teacher: Do They Have it? . 2024, 18, e05632–e05632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyati, E.; Susilo, H.; Suwono, H.; Rohman, F. Promoting student’s habits of mind and cognitive learning outcomes in science education. J. Pendidik. Biol. Indones. 2024, 10, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyoub, A.A.M.; Abu Eidah, B.A.; Khlaif, Z.N.; El-Shamali, M.A.; Sulaiman, M.R. Understanding online assessment continuance intention and individual performance by integrating task technology fit and expectancy confirmation theory. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behmanesh, F.; Bakouei, F.; Nikpour, M.; Parvaneh, M. Comparing the Effects of Traditional Teaching and Flipped Classroom Methods on Midwifery Students’ Practical Learning: The Embedded Mixed Method. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2020, 27, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, M.I.; Akan, E. Presence and Immersion in Virtual Reality. In Encyclopedia of Computer Graphics and Games; Lee, N., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A.; Stine, R.A. Bootstrapping Goodness-of-Fit Measures in Structural Equation Models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, L.; Galindo-Domínguez, H.; Bezanilla, M.-J.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Poblete, M. Methodologies for Fostering Critical Thinking Skills from University Students’ Points of View. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevikbas, M.; Bulut, N.; Kaiser, G. Exploring the Benefits and Drawbacks of AR and VR Technologies for Learners of Mathematics: Recent Developments. Systems 2023, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W. ; Kinshuk; Yu, P.-T.; Hsu, J.-M. Investigations of Using Interactive Whiteboards with and without an Additional Screen. 2011 11th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, USADATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 347–349.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. L. , & Kallick, B. (2000). Describing 16 habits of mind. A: Habits of mind.

- https://peertje.daanberg.net/drivers/intel/download.intel.com/education/Common/my/Resources/EO/Resources/Thinking/Habits_of_Mind.

- Davis, M.S.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: The Experience of Play in Work and Games. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1977, 6, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Conceptualizations of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination. In E. L. Deci

& R. M. Ryan, Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior (pp. 11–40). Springer US.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7_2.

- Di Mitri, D.; Limbu, B.; Schneider, J.; Iren, D.; Giannakos, M.; Klemke, R. Multimodal and immersive systems for skills development and education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.P.; Hogan, M.J.; Stewart, I. An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Think. Ski. Creativity 2014, 12, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgona, J.; Sakiyo, J.; Gwany, D.M.; Okoronka, A.U. Motivation in Learning. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, A.; Mirzaee, S. EFL Learners' Self-regulation, Critical Thinking and Language Achievement. Int. J. Linguistics 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghbari, T.A.; Harahsheh, A.H. Academic hope and self-regulation as predictors of creative thinking among undergraduate students. Creativity Stud. 2024, 17, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Tamez, C.R. The Impact of Immersion through Virtual Reality in the Learning Experiences of Art and Design Students: The Mediating Effect of the Flow Experience. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Tamez, C.R.; Dávila-Aguirre, M.C.; Codina, J.N.B.; Rodríguez, P.G. Analysis of the Elements of the Theory of Flow and Perceived Value and Their Influence in Craft Beer Consumer Loyalty. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2020, 33, 487–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, C.-J.; Hu, R.; Wu, Y.-Y. Effects of Virtual Reality Integrated Creative Thinking Instruction on Students’ Creative Thinking Abilities. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2016, 12, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, H.; Ursin, J.; Silvennoinen, K.; Kleemola, K.; Toom, A. The dynamic relationship between response processes and self-regulation in critical thinking assessments. Stud. Educ. Evaluation 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, T. , & Hidayati, N. ( 8, 151.

- Jamaludin, J.; Kakaly, S.; Batlolona, J.R. Critical thinking skills and concepts mastery on the topic of temperature and heat. J. Educ. Learn. (EduLearn) 2022, 16, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamińska, D.; Sapiński, T.; Wiak, S.; Tikk, T.; Haamer, R.E.; Avots, E.; Helmi, A.; Ozcinar, C.; Anbarjafari, G. Virtual Reality and Its Applications in Education: Survey. Information 2019, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S. , Luxton-Reilly, A. ( 10(2), 85–119.

- Education, M.O.N.; Kurt, U.; Atatürk University; Sezek, F. Investigation of the Effect of Different Teaching Methods on Students' Engagement and Scientific Process Skills. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2021, 17, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmaryono, I. (2023). How are Critical Thinking Skills Related to Students’ Self-Regulation and Independent Learning? Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 13(4), 85–92.

- Lase, F.L.; Halawa, N. Improving Motivation to Perform in Learning: A Study of The Influence of Two-Dimensional Media, Interest In Learning and The Value of Hard Work Character. Int. J. Contemp. Stud. Educ. (ij-Cse) 2024, 3, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. The Relationship of Motivation and Flow Experience to Academic Procrastination in University Students. J. Genet. Psychol. 2005, 166, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. (2009). Examining the relationships between metacognition, self-regulation and critical thinking in online socratic seminars for high school social studies students.

- Lindberg, E.; Bohman, H.; Hulten, P.; Wilson, T. Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial mindset: a Swedish experience. Educ. + Train. 2017, 59, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social-Cognitive View. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, V.L.; Yan, W. Applying Systems Thinking for Designing Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Experiences in Education. TechTrends 2023, 68, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, G.; De Pisapia, N. Virtual reality, face-to-face, and 2D video conferencing differently impact fatigue, creativity, flow, and decision-making in workplace dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnke, R.; Wagner, T.; Benlian, A. Flow Experience on the Web: Measurement Validation and Mixed Method Survey of Flow Activities.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Makransky, G.; Andreasen, N.K.; Baceviciute, S.; Mayer, R.E. Immersive virtual reality increases liking but not learning with a science simulation and generative learning strategies promote learning in immersive virtual reality. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 719–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marougkas, A.; Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C. Virtual Reality in Education: A Review of Learning Theories, Approaches and Methodologies for the Last Decade. Electronics 2023, 12, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R. J. (1992). A different kind of classroom: Teaching with dimensions of learning. ERIC.

- Marzano, R. J. , Pickering, D., & McTighe, J. (1993). Assessing student outcomes: Performance assessment using the dimensions of learning model. ERIC.

- Mills, M.J.; Fullagar, C.J. Motivation and Flow: Toward an Understanding of the Dynamics of the Relation in Architecture Students. J. Psychol. 2008, 142, 533–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Higher Education. (2010). Mid-Term Strategy for Higher Education Sector (2010, 2011-2013). Ministry of Education and Higher Education. https://www.mohe.pna.ps/Resources/Docs/StrategyEn.

- Education, M.O.N.; Kurt, U.; Atatürk University; Sezek, F. Investigation of the Effect of Different Teaching Methods on Students' Engagement and Scientific Process Skills. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2021, 17, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.H.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsea, E.; Drigas, A.; Skianis, C. Digitally Assisted Mindfulness in Training Self-Regulation Skills for Sustainable Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, M.; Bharathi, S.V. Theoretical foundations of design thinking – A constructivism learning approach to design thinking. Think. Ski. Creativity 2020, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawat, R.S. The Value of Ideas: The Immersion Approach to the Development of Thinking. Educ. Res. 1991, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2022). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In C.

Homburg, M. Klarmann, & A. Vomberg (Eds.), Handbook of Market Research (pp. 587–632). Springer

International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57413-4_15.

- Scavarelli, A.; Arya, A.; Teather, R.J. Virtual reality and augmented reality in social learning spaces: a literature review. Virtual Real. 2020, 25, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, T.; Friedmann, F.; Regenbrecht, H. The Experience of Presence: Factor Analytic Insights. PRESENCE: Virtual Augment. Real. 2001, 10, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Estrada, J.M.V.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, S.; Kester, L.; Van Gerven, T. An immersive virtual reality learning environment with CFD simulations: Unveiling the Virtual Garage concept. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 29, 1455–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriyati, S. , Rustaman, N. Y., & Zainul, A. (2011). Penerapan asesmen formatif untuk membentuk habits of mind mahasiswa biologi. Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia. Retrieved from Https://Docplayer. Info/56173936-Penerapan-Asesmen-Formatif-Untuk-Membentuk-Habits-Ofmind-Mahasiswa-Biologi. Html.

- Sternberg, R.J.; Lubart, T.I. The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In Handbook of creativity; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F. Understanding the role of digital immersive technology in educating the students of english language: does it promote critical thinking and self-directed learning for achieving sustainability in education with the help of teamwork? BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Aizawa, I.; Curle, S.; Rose, H. Exploring the role of self-efficacy beliefs and learner success in English medium instruction. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2019, 25, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, L. (2009). Creative thinking in medicine: Can we learn it from the masters and practice it? Hektoen International Journal, 1(4).

- Wang, X.-M.; Huang, X.-T.; Han, Y.-H.; Hu, Q.-N. Promoting students' creative self-efficacy, critical thinking and learning performance: An online interactive peer assessment approach guided by constructivist theory in maker activities. Think. Ski. Creativity 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Takada, N.; Hara, Y.; Sugiyama, S.; Ito, Y.; Nihei, Y.; Asakura, K. Impact of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation on Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nurses Working in Long-Term Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Into Pr. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).