1. Introduction

The increased agricultural activities and the expansion of irrigated farming have led to a rise in pesticide usage; hence, one of the critical occupational dangers worldwide is the subsequent poisoning by these pesticides [

1]. Pesticides were the most often involved substance in human exposures in 2022, according to the 2022 NPDS Annual Report, which provides data on exposure cases reported to US poison centers [

2]. Acounted for 3.69% of the total number of single substance exposure (3.53% in pediatric (≤ 5 years) and 4.61% in adult (≥20 years).

Among the often used common pesticides are pyrethroids like Deltamethrin, Cyphenothrin, D-Tetramethrin, Lambdacyhalothrin, D-Phenothrin, Permethrin, Niclosamide, Cyfluthrin, Allethrin, and organophosphates like Fenitrothion. Although these compounds are rather effective in regulating pests, their acute toxicity in animals is the most evident. Also can cause liver enlargement, a rise in liver enzyme activity, and increase susceptibility to a range of diseases, including respiratory problems, skin disorders, and neurological effects of individuals who are exposed to high levels of these chemicals for long durations [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Since they are harmful and might have different effects on different health aspects, these substances endanger the occupational workers.

Out of all the pyrethroids, only permethrin has been identified as potential or weak carcinogen by USEPA; its mutagenicity has been assessed to be very low [

3]. According to WHO's [

7] report, no laboratory research on human beings have revealed any carcinogens. Most of the 573 cases of acute pyrethroid primarily poisoning recorded in China between 1983 and 1988 came from occupational or unintentional exposure. Following the insecticide's injection into air-conditioning ducts, a severe form of unintentional pyrethroids poisoning was recorded. The affected individuals complained dyspnea, nausea, headache and irritability [

8,

9]. While sensomotor-polyneuropathy in the lower extremities and vegetative nervous disorders, like paroxysmal tachycardia, increased heat sensitivity and reduced exercise tolerance related to circulatory dysfunction [

9,

10], the chronic sequelae of pyrethroids exposure include cerebro-organic disorders.

Pesticides can induce systemic affect and be taken into the body via the skin, inhalation or ingestion. Blood parameters changes, higher oxidative stress, and changed metabolic processes have been associated to repeated exposure to these compounds [

9,

11,

12,

13]. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) technique analysis of biomarkers and organic profiles has provided valuable data regarding the biochemical changes linked with pesticide exposure [

14,

15]. This is crucial to be able to develop policies that can be implemented to be able to prevent or reduce the impacts of these compounds on human health, safety practices, laws and regulations, and therapy.

There have been various studies conducted to evaluate how pesticides affect hematological parameters. For example, the pyrethroids deltamethrin and permethrin have been linked to oxidative stress, alterations in red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin levels, and white blood cell (WBC) count [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Fenitrothion, an organophosphate, has been linked to anemia and leukocytosis in those who have been exposed to the insecticide at work [

20]. The aforementioned differences in blood markers indicate that long-term pesticide exposure causes immunological issues and systemic harm. Moreover, workers exposed to organophosphates and pyrethroids showed lower antioxidant enzyme activity [

21,

22]. These findings show that oxidative stress may be involved in the pathophysiology of pesticide poisoning, resulting in cell damage and inflammation.

Furthermore, multiple pesticide exposures may occur, resulting in synergistic or cumulative toxicity. For example, exposure to both pyrethroids and organophosphates has been shown to enhance oxidative stress and disrupt metabolic processes [

23,

24]. This underscores the need for additional research on the cumulative effects of pesticide exposure in order to better comprehend the risks to human health. As a result, characterisation of blood chemo-profiles and the use of identified metabolites as biomarkers of pyrethroid pesticide exposure could help in the identification and prediction of potential harmful consequences, which may be employed in preventive actions and risk assessments.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted with the participation of a total of 250 male volunteers who were between the ages of 20 and 60 and who worked with pesticides in the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia. Participants in this study had exposure intervals that ranged from one to two years, three to five years, six to eight years, and even more than eight years (exposure intervals: 1-2, 3-5, 6-8, more than 8 years). The use of a questionnaire allowed for the collection of a variety of information, including demographic data, the amount of time that participants had been exposed to pesticides, and the existence of chronic conditions. Following the collection of blood samples for the purpose of carrying out a biochemistry analysis, the samples were extracted through the use of solid phase extraction in order to carry out a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) study.

Samples that were prepared using the procedure described by Latif et al. (2012) [

25], with a few modifications. One milliliter of whole blood was placed into a screw-capped vial that had a capacity of twenty milliliters. An internal standard of one microgram per milliliter of triphenylphosphine (TPP) was added to the blood. Immediately following that, one milliliter of methanol was added to the mixture, and it was vortexed for a duration of one minute. After two minutes of vortexing, ten milliliters of an extraction solvent that was composed of n-hexane and acetone in a ratio of nine to one was added to the mixture. Sonication was performed on the bottles for a period of two minutes after the addition of two grams of anhydrous sodium sulfate. Following this, the bottles were centrifuged for a period of five minutes at a speed of four thousand revolutions per minute. The layer of organic solvent was then filtered into clean 12 ml tubes using a 0.45 µm syringe filter. This was done after the method described above. The liquid that was produced was then subjected to the influence of nitrogen gas in order to evaporate it until it became dry. After everything was said and done, the residues were reconstituted with 200 microliters of methanol, and then they were put into a GCMS vial that was 2 milliliters in volume and had 300 microliters of insert.

A gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (GCMSQP-2010 ultra, Shimadzu, Japan) was utilized in order to carry out the GC. They were developed in accordance with the description that was supplied by Hassan et al (2014) [

26], with a few modifications. For the purpose of chromatographic separation of components, a capillary column manufactured by Thermo Scientific and designated as TR-5 MS was utilized. The interior diameter of the column measured thirty-five millimeters, and its thickness measured twenty-five micrometers. The column measured thirty meters in length. One milliliter per minute was found to be the optimal flow rate for the helium carrier gas, according to the findings of the study. In order to inject the sample extract, which had a volume of 2 microliters, into the injection port, a splitless mode that was heated to 260 degrees Celsius was utilized. For one minute, the temperature in the oven was kept at 70 degrees Celsius, and then it gradually increased to 210 degrees Celsius at a rate of 30 degrees Celsius per minute, with a hold interval of two minutes in between each increment. In the end, the ramping rate was increased to 290 degrees Celsius at a rate of 20 degrees per minute, and there was a holding period of fifteen minutes. A temperature of 70 degrees Celsius was chosen for the oven's beginning temperature for a period of one minute. It was necessary to make use of the electron ionization (EI) source in addition to the scan mode mode that was contained within the mass spectrometer in order to run it. The electron energy was 70 eV and the temperature of the interface was maintained at 290 degrees Celsius, while the temperature of the ion source was maintained at 230 degrees Celsius.

The method of statistical analysis involved data grouping by exposure groups and compounds, calculating descriptive statistics (mean, SEM, and occurrences), and identifying significant compounds using R Statistical Software. Non-parametric testing due to non-normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test, p<0.001) and Kruskal-Wallis methods with significance at (p<0.05) were used. For significant compounds mean peak areas were compared and mean values with 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

3. Results

This study investigated the relationship between the frequency of chronic diseases and the duration of pesticide exposure in 250 workers. The age distribution of the participants was as follows: 20-30 (62), 31-40 (101), 41-50 (62), and 51-60 (25). The participants ranged in age from 20 to 60. Most frequently between the ages of 31 and 40, participants also fall from the 20–30 and 41–50 age ranges. The four groups of exposure times are 1–2 years (n = 52), 3–5 years (n = 44), 6–8 years (n = 26), and >8 years (n = 128). Although most participants have either secondary or tertiary education, a small number have only finished primary school.

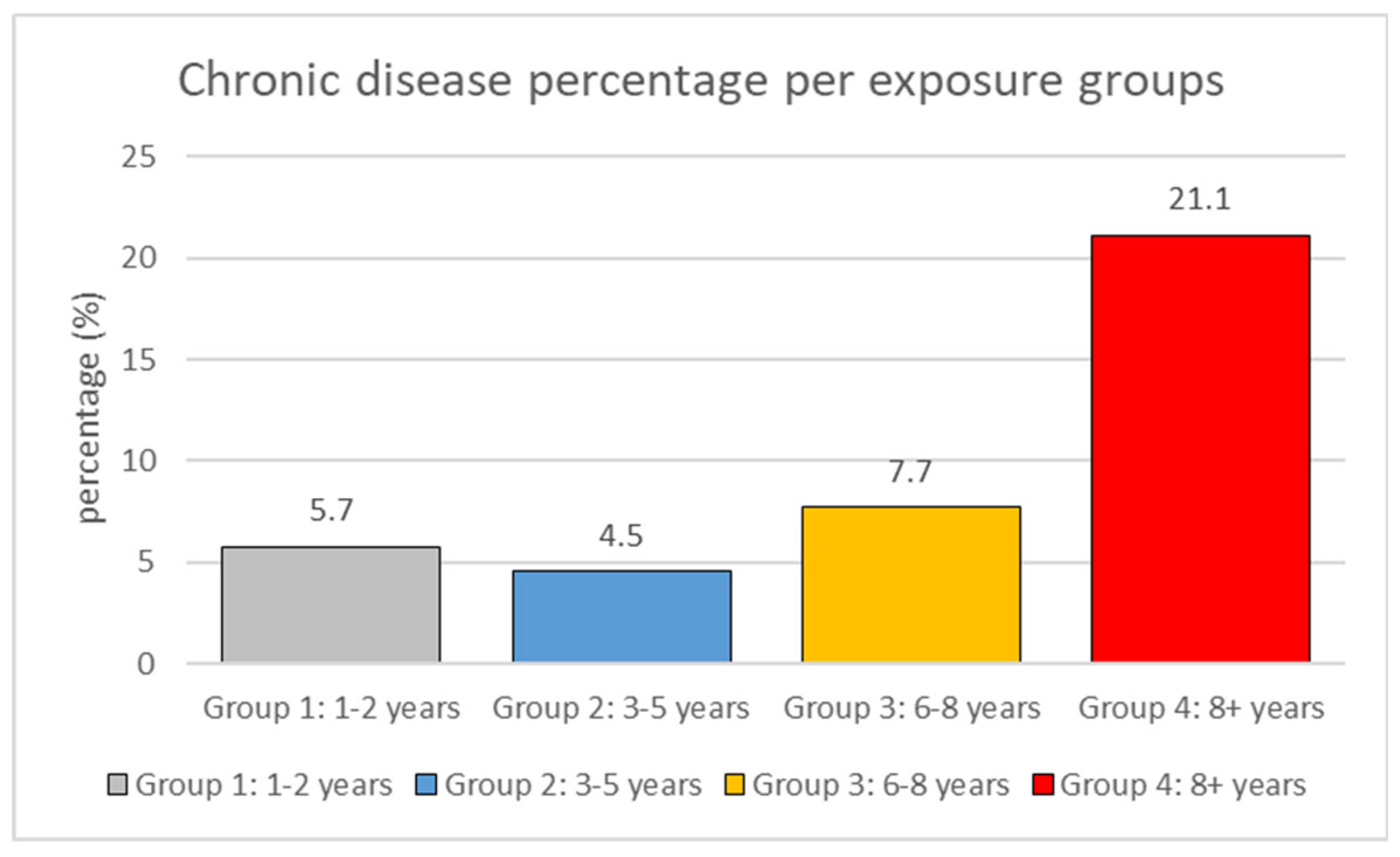

The proportion of chronic diseases increases with longer exposure periods: 1-2 years (5.7% have chronic diseases), 3-5 years (4.5%), 6-8 years (7.7%), 8+ years (21.1%) (

Figure 1). This indicates that workers in exposure group 4 (8+ years) have roughly a 3.7-fold higher risk of chronic diseases compared to those in exposure group 1 (1-2 years). Chronic diseases were relatively infrequent in the shorter exposure groups but increased significantly in workers with longer exposure periods.

The trend analysis revealed a significant association between exposure duration and chronic disease prevalence. Its demonstrates the substantial increase in chronic disease prevalence associated with longer exposure durations, particularly in Group 4 where the prevalence is approximately 3.7 times higher than in Group 1. Starting with 5.7% in the 1-2 years group and 4.5% in the 3-5 years group, rising to 7.7% in the 3-5 years group, and then reaching 21.1% in the 8+ years group, the frequency of chronic diseases exhibited a steady increase with longer exposure periods. This trend shows a significant link between chronic disease risk and exposure length; workers with more than 8 years of exposure show particularly greater susceptibility to disease.

3.1. Blood Parameters Analysis Results

The study evaluated hematological and biochemical parameters across four exposure duration groups: 1-2 years, 3-5 years, 6-8 years, and 8+ years. All participants had complete blood count and biochemical parameters measured (

Table 1).

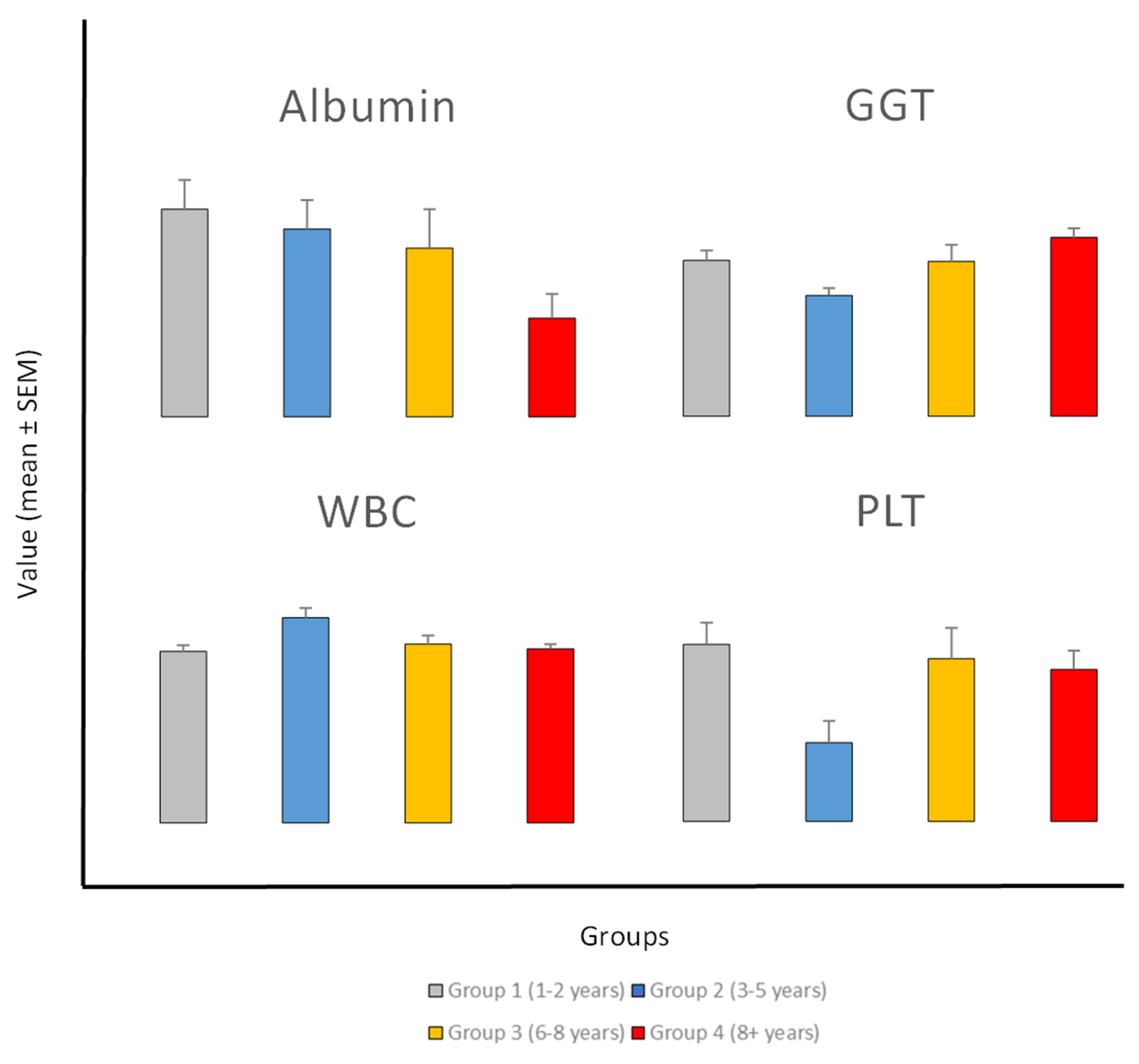

Analysis of blood parameters across different exposure durations revealed significant alterations in several parameters. The bar plot for significant parameters (

Figure 2) demonstrates the changes in parameters levels with increase the exposure duration.

Albumin (ALB) levels exhibited a significant declining trend with increased exposure duration (p=0.003). The mean albumin (ALB) levels showed a significant decrease in the 8+ years group (37.95 ± 0.50 g/L) compared to the 1-2 years group (40.20 ± 0.59 g/L), representing a consistent downward trend across exposure categories. Based on the correlation analysis between exposure period and blood parameters, pearson correlation analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between exposure duration and serum albumin (ALB) levels (r = -0.952, p = 0.048), indicating a strong inverse relationship between exposure time and albumin concentration. This suggests a potential decline in liver synthetic function with prolonged exposure. With a p=0.0002, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) showed the most notable change among each of the parameters. From 50.35 ± 3.26 U/L in the 1-2 years group to 57.83 ± 2.91 U/L in the 8+ years group, GGT levels showed an increasing tendency with respect to exposure time; a clear dip in the 3-5 year group (39.05 ± 2.38 U/L). Additionally statistically significant changes in White Blood Cell Count (WBC) (p=0.016) and Platelet Count (PLT) (p=0.032) were found.

RBC, HGB, HCT, MCV, MCH, MCHC, TP, ALPI, AST, and ALTI were among the other blood parameters that did not approach statistical significance differences across exposure groups (p>0.05). This indicates that there are more subtle alterations in these markers between groups. Nevertheless, for all of the exposure durations, these metrics remained within the guidelines of their respective reference ranges.

3.2. Blood Chemo-Profiling Analysis

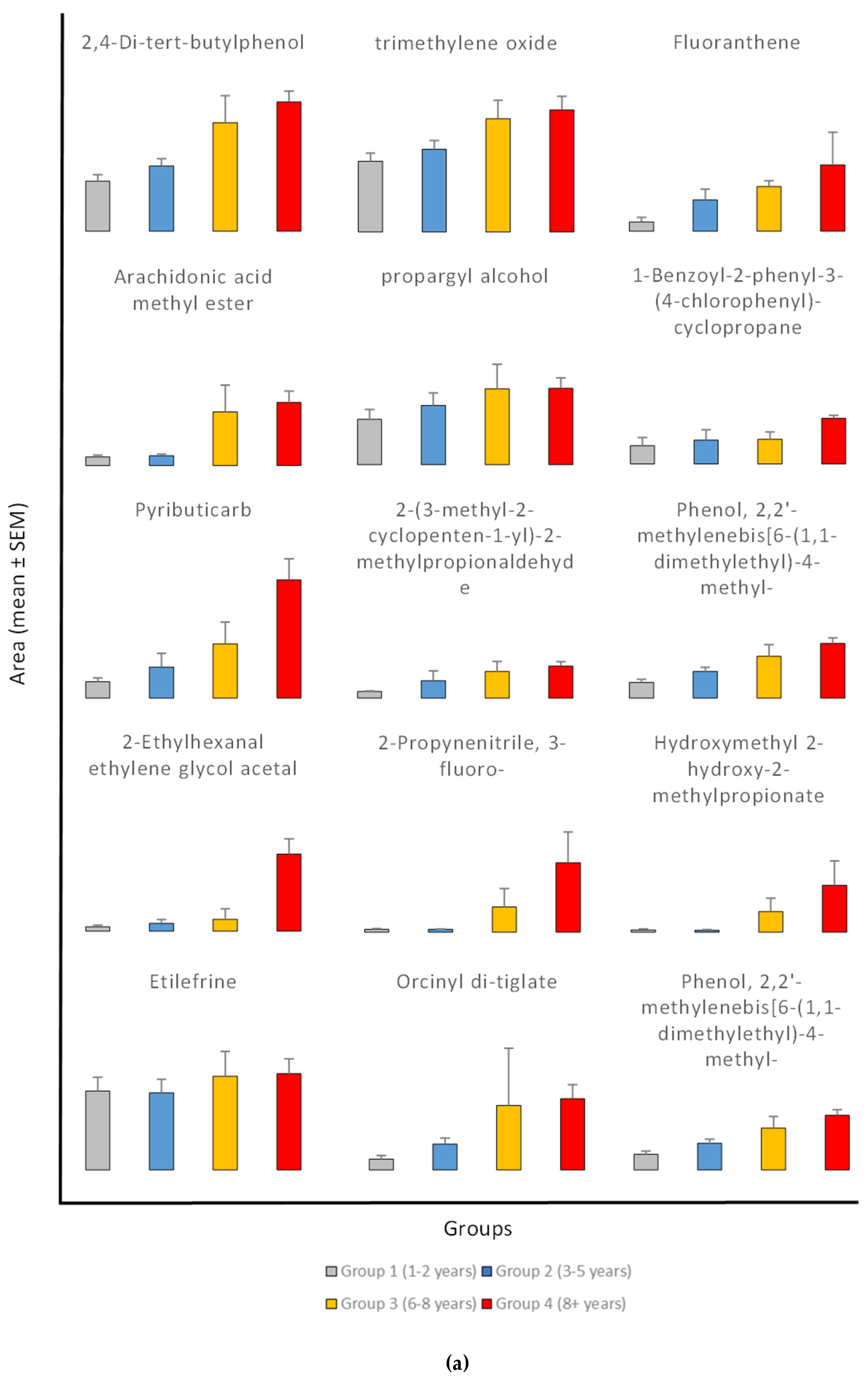

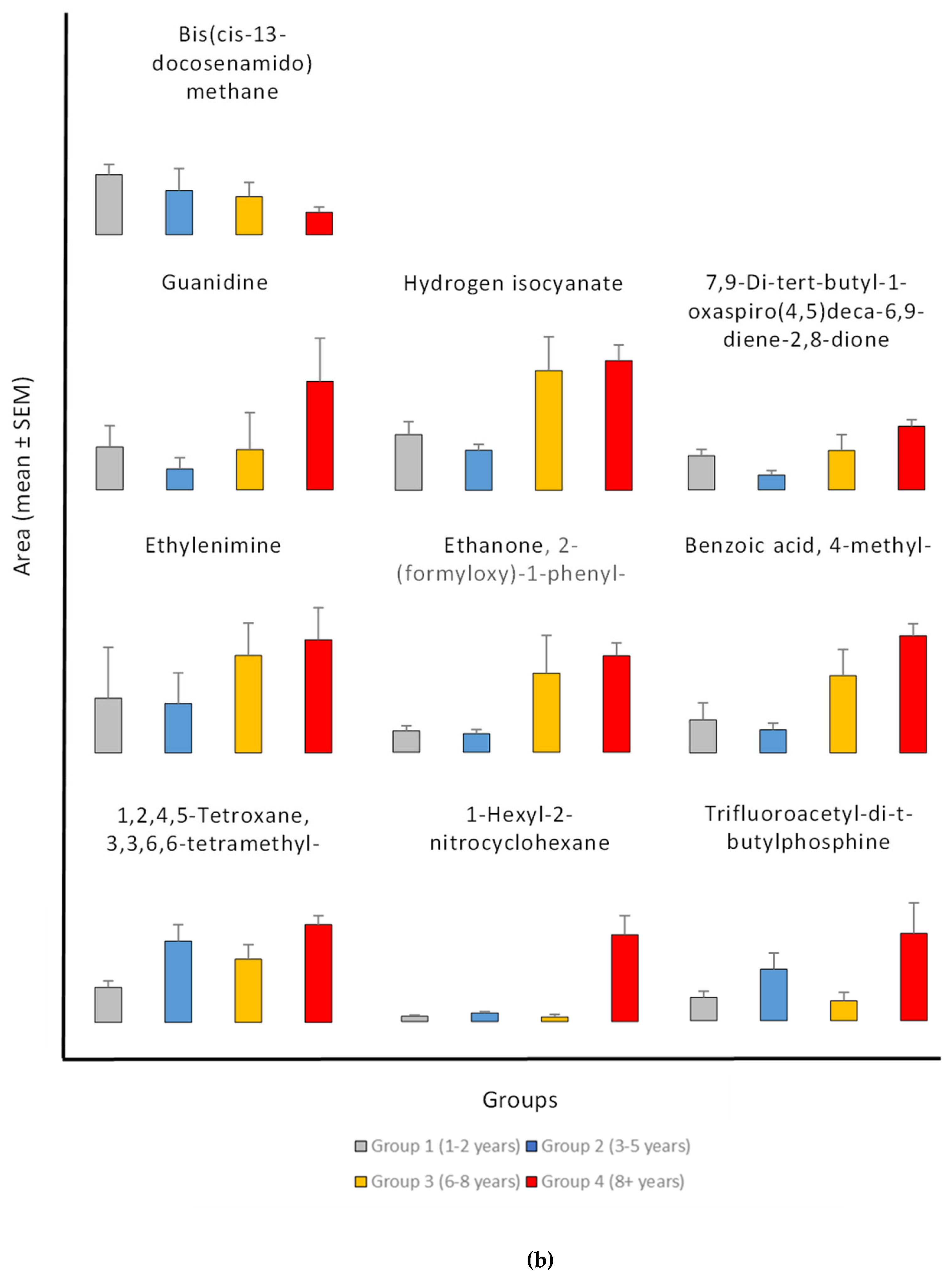

The GCMS study identified compounds displaying significant differences across exposure groups. Overall, the findings show that 1,080 different chemicals were found among all the groups. Investigating group distributions, unique compounds, and compound area trends allowed to identify the most important trends and variations among the exposure groups. Indicating a greater diversity of chemicals with longer exposure times, Group 4 (8+ years) had the most samples (127) and unique compounds (268). With 25 samples and 48 unique compounds, Group 3 (6–8 years) had the lowest compound identified range. Groups 1 (1–2 years) and 2 (3–5 years) had correspondingly modest sample numbers (52 and 44, respectively) and unique compounds (142 and 118, respectively). Group 4 (8+ years) contains the highest number of compounds with significant unique compounds per group according to the intersection analysis; meanwhile, the intersections expose notable overlap between groups, especially between adjacent exposure length groups. This implies the formation of new compounds with extended exposure times as well as persistence of some compounds over time.

In addition, 192 compounds were always present in all four exposure groups, which are the key compounds that persist during all exposure times. Out of the 192 prevalent compounds, 25 exhibited relationships with exposure times. Moreover, the study revealed compounds with both growing and declining trends between groups; for most compounds across exposure groups the distribution shows clear increases in mean area (

Figure 3). Among them, one showed negative connections and 24 chemicals showed positive ones. Correlation coefficients between the average area of each compound and the exposure period were obtained in order to find compounds having significant correlations to exposure periods. The non-normal distribution of the data and different sample sizes across groups led the analysis to use non-parametric statistical techniques (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test).

The values of common compounds were determined for four age groups: Group 1 (1-2 years), Group 2 (3-5 years), Group 3 (6-8 years), and Group 4 (8+ years). The study found significant exposure-related patterns in various common chemical components across four age groups (1-2 years, 3-5 years, 6-8 years, and 8+ years). The compounds had both positive and negative associations with exposure periods, indicating systematic changes in chemical composition over time (

Figure 3).

The results showed significant exposure-related increase, with progressive increase observed from Group 1 (1-2 years) to Group 4 (8+ years) in the levels of 2-Ethylhexanal ethylene glycol acetal (1600% increase), 1-Hexyl-2-nitrocyclohexane (1562% increase), Arachidonic acid methyl ester, Pyributicarb (614% increase), 3-Phenyl-6-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-(1,2,3)triazolo(1,5-d)(1,3,4)oxadiazin-4-one (505% increase), 2-(3-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-yl)-2-methylpropionaldehyde (380 increase), Ethanone, 2-(formyloxy)-1-phenyl-(+350% increase), Phenol, 2,2'-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl- (250% increase), 1,2,4,5-Tetroxane, 3,3,6,6-tetramethyl- (180% increase), 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol (159% increase), 1-Benzoyl-2-phenyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-cyclopropane (150% increase), Benzoic acid, 4-methyl- (148% increase), Hydrogen isocyanate (132% increase), 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione (+87.66% increase), and trimethylene oxide (72% increase).

The findings also showed an exposure-related escalation, characterized by a consistent upward pattern in mean levels correlating with exposure duration, particularly between Group 1 (1-2 years) and Group 4 (8+ years) for 2-Propynenitrile, 3-fluoro- (2344% increase), Hydroxymethyl 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropionate (2234% increase), Fluoranthene (650% increase), Orcinyl di-tiglate (556% increase), Trifluoroacetyl-di-t-butylphosphine (272% increase), Guanidine (153% increase), Ethylenimine (106% increase), propargyl alcohol (68% increase), and Etilefrine (22% increase). The consistent rise in many compounds suggests that accumulation associated to exposure is a prevalent occurrence. The results reveal a propensity for elevated levels with exposure; however, the variability within groups complicates the identification of statistically significant differences. Additional research with larger sample sizes may be necessary to confirm these trends.

In contrast, the compound Bis(cis-13-docosenamido)methane is unique among the investigated compounds in that it shows a significant decrease in average detected area with increasing exposure times. Specifically, the average area measured in the youngest exposure group (1-2 years) is approximately 2.7 times greater than that observed in the group exposed for 8+ years. This negative trend may indicate that this compound accumulates more in earlier age groups. The significant reduction of approximately 62% from Group 1 to Group 4 suggests a possible exposure-related metabolic or environmental mechanism influencing the levels of Bis(cis-13-docosenamido)methane.

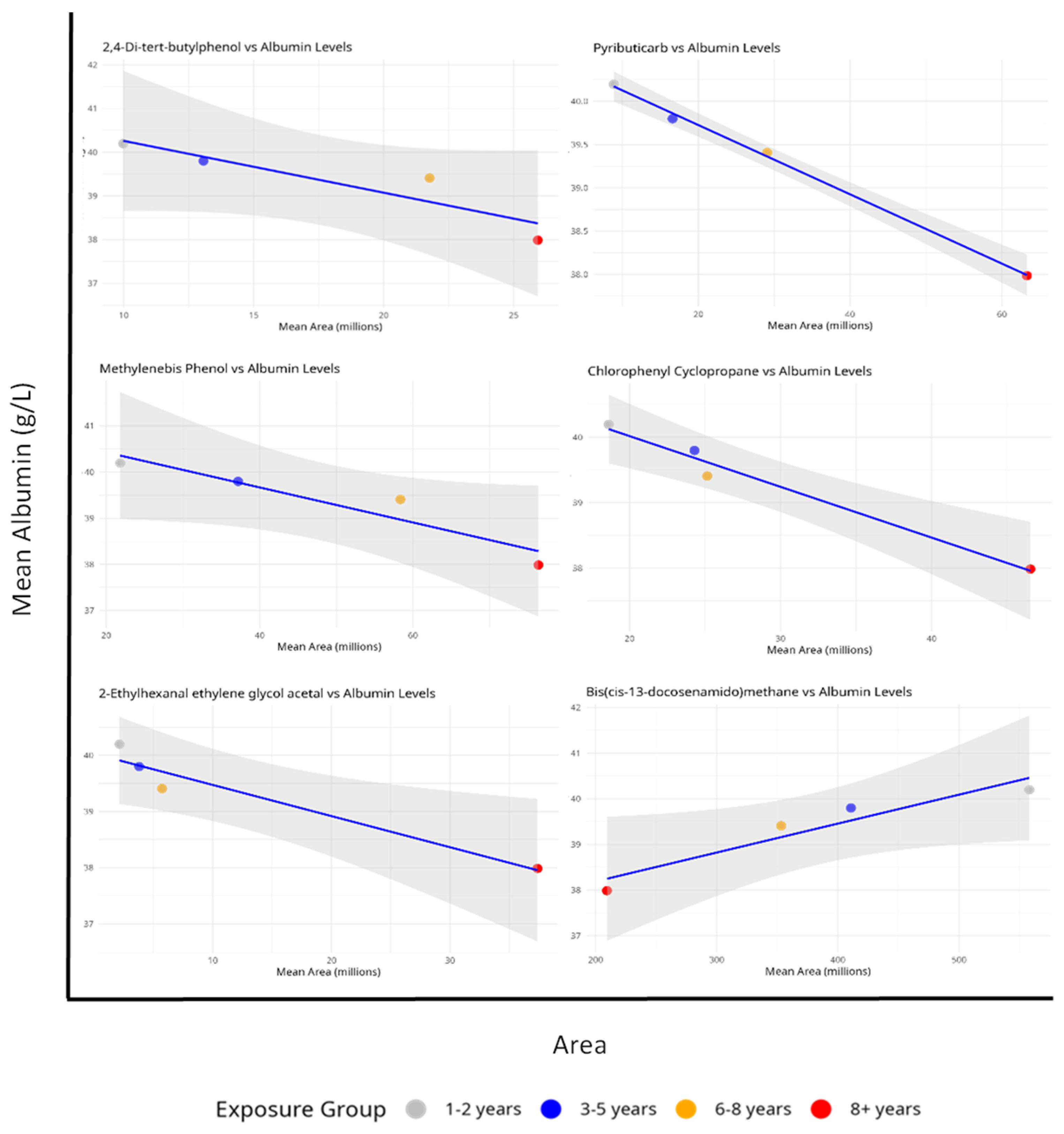

3.3. The Relationship Between Common Compounds and Albumin Concentrations

In order to determine if common compounds had significant effects on albumin concentrations, linear regression models were used to examine the relationship between common compound relative levels and albumin concentrations across exposure groups (

Figure 4).

The analysis reveals a strong and statistically significant negative relationship between albumin levels and Pyributicarb (p = 0.001, R² = 0.998), 1-Benzoyl-2-phenyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-cyclopropane (p = 0.011, R² = 0.977), and 2-Ethylhexanal ethylene glycol acetal (p = 0.032, R² = 0.937). The inverse relationship appears to be statistically significant, with a dose-response pattern across the exposure groups. The strong R² value indicates that increased exposure to this compound significantly contributes to lower albumin levels..

The study also revealed a notable inverse connection between albumin levels and area measurement for phenol, 2,2'-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl- (p = 0.057, R² = 0.889), and 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol (p = 0.086, R² = 0.836) across the analyzed exposure groups. Unlike other compounds, Bis(cis-13-docosenamido)methane shows a positive connection with albumin levels (p = 0.050, R² = 0.902). Calculated to be 0.950, the correlation value indicated a strong positive linear relationship. Although the slope's p-value is slightly higher than the usual 0.05 threshold, it still suggests a significant tendency toward significance, especially given that the study is based on four distinct exposure groups.

4. Discussion

In 250 participants occupationally exposed to pesticides in the Jazan region of Saudi Arabia, this study examined the effects of pesticide exposure on blood parameters as well as the significant changes in blood chemo-profile related with exposure periods.

The prevalence of chronic diseases and exposure time showed a notable correlation according to trend study. Workers with 8 or more years of exposure had a 3.7-fold higher risk of chronic diseases than those with 1-2 years of experience, therefore proving that the longer the exposure, the more risk of chronic health problems exists. This tendency is in agreement with previous studies showing that total occupational hazard exposure—including pesticides—highly increases the incidence of chronic health problems. Research on pesticide exposure workers has revealed that longer exposure times increase the risk of respiratory and neurological illnesses [

27]. In this study, the observed risk increase after six years suggests a threshold effect, accelerating disease development by overwhelming the body's compensatory systems. This study population has 10.80% chronic diseases, which is consistent with occupational cohort data. However, demographics, intensity, and exposure type may vary. Studies show that long-term pesticide exposure increases the risk of chronic diseases such diabetes [

28,

29]. These findings emphasize the importance of improving workplace preventative actions, particularly for long-term exposed workers. Early intervention, exposure reduction, and health monitoring lower chronic illness risk.

This study also found that albumin levels were significantly lower after 8+ years of exposure than after 1-2 years, which is consistent with previous research associating chronic environmental or occupational stress to liver function abnormalities. Chronic pesticide exposure reduced albumin levels, potentially due to impaired liver synthesis or increased protein metabolism, according to Palaniswamy, S. et al. (2021) and Tarhoni, M.H. (2008) [

30,

31]. Additionally, the results indicate a correlation between alterations in some blood parameters and prolonged exposure durations. The most alarming results originated from GGT and albumin levels, indicating potential hepatic damage due to prolonged exposure. GGT exhibits an increasing trend relative to exposure duration, particularly in the 8+ age demographic, whereas ALB demonstrates an overall decreasing trend with extended exposure time. These findings emphasize the importance of albumin as a sensitive indicator of prolonged exposure effects, especially when other liver function tests show no evident changes [

32,

33]. This suggests that albumin may serve as a sensitive marker for long-term effects on liver function, necessitating more investigation into its therapeutic significance. Future research should examine the role of additional confounding variables and biochemical markers in detecting early indicators of liver injury.

GCMS results analysis demonstrated that Group 4 (8+ years) had the most distinct compounds, showing prolonged exposure complicates the chemical profile. It may imply cumulative effects or secondary compounds generated over time. The data also show dynamic compound abundance variations throughout exposure periods, with significant correlations and fold changes suggesting biomarkers or exposure-related effects. Including 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol, trimethylene oxide, Pyributicarb, Phenol, 2,2'-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl-, 1-Benzoyl-2-phenyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-cyclopropane, 2-(3-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-yl)-2-methylpropionaldehyde, 2-Ethylhexanal ethylene glycol acetal, Hydrogen isocyanate, Benzoic acid, 4-methyl-, Ethanone, 2-(formyloxy)-1-phenyl-, 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione, 3-Phenyl-6-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-(1,2,3)triazolo(1,5-d)(1,3,4)oxadiazin-4-one, 1-Hexyl-2-nitrocyclohexane, Arachidonic acid methyl ester and 1,2,4,5-Tetroxane, 3,3,6,6-tetramethyl-. The results showed that exposure increased the previously mentioned compounds, especially after 8 years. A significant exposure-related accumulation pattern suggests it may be a marker for metabolic alterations. It may also indicate physiological or environmental variables affecting its accumulation. More research is needed to confirm these findings and use it as an exposure-related biomarker and metabolic monitor. All these compounds can behave as reactive intermediates impacting redox equilibrium, metabolism, or enzyme efficiency.

Interestingly, propargyl alcohol levels increased significantly from 1-2 to 3-5 years of exposure. This chemical is widely utilized as a solvent and intermediary in pesticide formulations. Its high reactivity and capacity for oxidative stress generation have been observed and proved to cause adenomas in toxicological studies [

34]. Furthermore, the data show that trimethylene oxide, a chemical that appears to induce atherosclerosis, increased by 72% from exposure group 1 to group 4. Trimethylene oxide has been linked to increased plaque in the aorta [

35]. 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol and Pyributicarb have toxicity characteristics that distinguish them from other detected compounds with significant associations. 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol disrupts the endocrine system [

36] and Pyributicarb alters metabolism [

37]. This study also found significant temporal trends in Hydrogen isocyanate levels across exposure periods, suggesting cumulative effects. Chemically reactive hydrogen isocyanate is used in industry and as a pesticide byproduct. The level rise with prolonged exposure may indicate bioaccumulation. Since isocyanates form persistent protein adducts, they persist in biological tissues longer [

38,

39]. Chronic isocyanate exposure can cause asthma and hypersensitivity pneumonitis [

38,

40]. These findings emphasize the significance of monitoring and limiting exposure to this compounds and the need for additional studies into long-term health effects, particularly in occupationally exposed populations. While Bis(cis-13-docosenamido)methane exhibited a significant positive correlation, Pyributicarb, 1-Benzoyl-2-phenyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-cyclopropane and 2-Ethylhexanal ethylene glycol acetal showed significant negative correlations with Albumin levels. The positive relationship between Bis(cis-13-docosenamido)methane could suggest a compensating or protective biological effect on albumin levels at given exposure levels, thereby requiring more investigation.

The study's small sample size in some demographic categories, as well as other potential confounding factors, limit its ability to fully represent the complexity of chemical exposure. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and assess the health affects of these compounds, particularly for vulnerable groups.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the study found significant links between pesticide exposure and health markers. Workers with 8+ years of exposure had a higher risk of chronic diseases than those with 1-2 years. Several compounds increased while some decreased with exposure length. This study reveals chemical exposure trends throughout time. The observed trends may be pesticide exposure biomarkers, but higher sample sizes are needed to confirm. This study emphasizes the necessity for health monitoring and targeted exposure reduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S., E.N. and I.A.; methodology, O.D., E.N., O.M. and S.Q.; software, M.O. and I.A.; validation, M.O., A.H. and M.A.; formal analysis, I.A. and M.H.A.; investigation, M.O., S.Q., Y.M and O.S.; resources, Al.H., E.A., I.K., A.A.A., Z.E., A.A. and Y.M.; data curation, M.O., O.S. and I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.; writing—review and editing, M.O., O.S., Y.H., A.M., A.H.H., W.M. and A.S; visualization, I.A.; supervision, O.S. and M.O.; project administration, O.S.; funding acquisition, O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Jazan Health Ethics Committee, Saudi Arabia (Date: 16 March 2023, No. 2318).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant details are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted at Forensic Toxicology Services in Jazan, Ministry of Health Branch in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alokail, M.S.; Abd-Alrahman, S.H.; Alnaami, A.M.; Hussain, S.D.; Amer, O.E.; Elhalwagy, M.E.A.; Al-Daghri, N.M. Regional Variations in Pesticide Residue Detection Rates and Concentrations in Saudi Arabian Crops. Toxics 2023, 11, 798. [CrossRef]

- Gummin, D.D.; Mowry, J.B.; Beuhler, M.C.; Spyker, D.A.; Rivers, L.J.; Feldman, R.; Brown, K.; Pham, N.P.T.; Bronstein, A.C.; DesLauriers, C. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System((R)) (NPDS) from America's Poison Centers((R)): 40th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2023, 61, 717-939. [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Beilschmidt, D. Toxicology and environmental fate of synthetic pyrethroids. Journal of Pesticide Reform 1990; 10:3.

- Hildebrand, M.E.; McRory, J.E.; Snutch, T.P.; Stea, A. Mammalian voltage-gated calcium channels are potently blocked by the pyrethroid insecticide allethrin. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2004, 308, 805-813. [CrossRef]

- Lifeng, T.; Shoulin, W.; Junmin, J.; Xuezhao, S.; Yannan, L.; Qianli, W.; Longsheng, C. Effects of fenvalerate exposure on semen quality among occupational workers. Contraception 2006, 73, 92-96. [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Xu, L.; Wang, S.; Xia, Y.; Tan, L.; Chen, J.; Song, L.; Chang, H.; Wang, X. Study on the relation between occupational fenvalerate exposure and spermatozoa DNA damage of pesticide factory workers. Occupational and environmental medicine 2004, 61, 999-1005. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Safety of pyrethroids for public health use; World Health Organization: 2005.

- Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; He, F.; Yao, P.; Wu, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Q. An epidemiological study on occupational acute pyrethroid poisoning in cotton farmers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 1991, 48, 77-81. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V.M.; Verma, V.K.; Rawat, B.S.; Kaur, B.; Babu, N.; Sharma, A.; Dewali, S.; Yadav, M.; Kumari, R.; Singh, S. Current status of pesticide effects on environment, human health and it’s eco-friendly management as bioremediation: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13, 962619. [CrossRef]

- Müller-Mohnssen, H. Chronic sequelae and irreversible injuries following acute pyrethroid intoxication. Toxicology letters 1999, 107, 161-176. [CrossRef]

- Tudi, M.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Yang, L.; Tong, S.; Yu, Q.J.; Ruan, H.D.; Atabila, A. Exposure routes and health risks associated with pesticide application. Toxics 2022, 10, 335. [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I.; Matviishyn, T.M.; Husak, V.V.; Storey, J.M.; Storey, K.B. Pesticide toxicity: a mechanistic approach. EXCLI journal 2018, 17, 1101. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D.L.; Daroff, R.B.; Autrup, H.; Bridges, J.; Buffler, P.; Costa, L.G.; Coyle, J.; McKhann, G.; Mobley, W.C.; Nadel, L. Review of the toxicology of chlorpyrifos with an emphasis on human exposure and neurodevelopment. Critical reviews in toxicology 2008, 38, 1-125. [CrossRef]

- Alami, R. DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF A GC/MS-BASED ASSAY FOR DETECTING PESTICIDE RESIDUES IN HUMAN BLOOD. The American Journal of Medical Sciences and Pharmaceutical Research 2024, 6, 7-12.

- Fama, F.; Feltracco, M.; Moro, G.; Barbaro, E.; Bassanello, M.; Gambaro, A.; Zanardi, C. Pesticides monitoring in biological fluids: Mapping the gaps in analytical strategies. Talanta 2023, 253, 123969. [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.; Rathore, N.; John, S.; Bhatnagar, D. Lipid peroxidative damage on pyrethroid exposure and alterations in antioxidant status in rat erythrocytes: a possible involvement of reactive oxygen species. Toxicology letters 1999, 105, 197-205. [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Mandal, T.; Das, S. Repeated dose toxicity of deltamethrin in rats. Indian journal of pharmacology 2005, 37, 160-164. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Ranjbar, A.; Shadnia, S.; Nikfar, S.; Rezaie, A. Pesticides and oxidative stress: a review. Med Sci Monit 2004, 10, 141-147.

- Aljali, A.; Othman, H.; Hazawy, S. Toxic Effect of Deltamethrin on Some Hematological and Biochemical Parameter of Male Rats. AlQalam Journal of Medical and Applied Sciences 2023, 536-546.

- Fareed, M.; Pathak, M.K.; Bihari, V.; Kamal, R.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kesavachandran, C.N. Adverse respiratory health and hematological alterations among agricultural workers occupationally exposed to organophosphate pesticides: a cross-sectional study in North India. PloS one 2013, 8, e69755. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, A.; Solhi, H.; Mashayekhi, F.J.; Susanabdi, A.; Rezaie, A.; Abdollahi, M. Oxidative stress in acute human poisoning with organophosphorus insecticides; a case control study. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 2005, 20, 88-91. [CrossRef]

- Abou El-Magd, S.A.; Sabik, L.M.; Shoukry, A. Pyrethroid toxic effects on some hormonal profile and biochemical markers among workers in pyrethroid insecticides company. Life Sci J 2011, 8, 311-322.

- Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Wang, T.; Kou, R.; Liu, P.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C. Synergistic effects on oxidative stress, apoptosis and necrosis resulting from combined toxicity of three commonly used pesticides on HepG2 cells. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2023, 263, 115237. [CrossRef]

- Iyyadurai, R.; Peter, J.; Immanuel, S.; Begum, A.; Zachariah, A.; Jasmine, S.; Abhilash, K. Organophosphate-pyrethroid combination pesticides may be associated with increased toxicity in human poisoning compared to either pesticide alone. Clinical Toxicology 2014, 52, 538-541. [CrossRef]

- Yawar, L.; Syed Tufail Hussain, S.; Muhammad Iqbal, B.; Shafi, N. Evaluation of pesticide residues in human blood samples of agro professionals and non-agro professionals. American Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2012, , 3, 587–595. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Abdullah, S.M.; Khardali, I.A.; Shaikhain, G.A.; Oraiby, M.E. Evaluation of pesticides multiresidue contamination of khat leaves from Jazan region, Kingdome Saudi Arabia, using solid-phase extraction–gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry 2013, 95, 1477-1483. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, F.; Hoppin, J.A. Association of pesticide exposure with neurologic dysfunction and disease. Environmental health perspectives 2004, 112, 950-958. [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, S.; Miozzi, E.; Teodoro, M.; Briguglio, G.; De Luca, A.; Alibrando, C.; Polito, I.; Libra, M. Occupational exposure to pesticides as a possible risk factor for the development of chronic diseases in humans. Molecular medicine reports 2016, 14, 4475-4488. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.; Kamel, F.; Saldana, T.; Alavanja, M.; Sandler, D. Incident diabetes and pesticide exposure among licensed pesticide applicators: Agricultural Health Study, 1993–2003. American journal of epidemiology 2008, 167, 1235-1246. [CrossRef]

- Palaniswamy, S.; Abass, K.; Rysä, J.; Odland, J.Ø.; Grimalt, J.O.; Rautio, A.; Järvelin, M.-R. Non-occupational exposure to pesticides and health markers in general population in Northern Finland: Differences between sexes. Environment International 2021, 156, 106766. [CrossRef]

- Tarhoni, M.H.; Lister, T.; Ray, D.E.; Carter, W.G. Albumin binding as a potential biomarker of exposure to moderately low levels of organophosphorus pesticides. Biomarkers 2008, 13, 343-363. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Lind, L.; Salihovic, S.; van Bavel, B.; Ingelsson, E.; Lind, P.M. Persistent organic pollutants and liver dysfunction biomarkers in a population-based human sample of men and women. Environmental research 2014, 134, 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yin, H.; Liu, M.; Xu, G.; Zhou, X.; Ge, P.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Impaired albumin function: a novel potential indicator for liver function damage? Annals of medicine 2019, 51, 333-344. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.A.; Flake, G.P.; Travlos, G.S.; Dill, J.A.; Grumbein, S.L.; Harbo, S.J.; Hooth, M.J. Evaluation of propargyl alcohol toxicity and carcinogenicity in F344/N rats and B6C3F1/N mice following whole-body inhalation exposure. Toxicology 2013, 314, 100-111. [CrossRef]

- Moise, A.M.R. The Gut Microbiome: Exploring the Connection between Microbes, Diet, and Health; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781440842658.

- Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Lucardi, R.D.; Su, Z.; Li, S. Natural sources and bioactivities of 2, 4-di-tert-butylphenol and its analogs. Toxins 2020, 12, 35. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H.; Sata, F.; Takeuchi, S.; Sueyoshi, T.; Nagai, T. Comparative study of human and mouse pregnane X receptor agonistic activity in 200 pesticides using in vitro reporter gene assays. Toxicology 2011, 280, 77-87. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Pobłocki, K.; Drzeżdżon, J.; Gawdzik, B.; Jacewicz, D. Isocyanates and isocyanides-Life-threatening toxins or essential compounds? Science of The Total Environment 2024, 173250. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K.; Takeshita, T.; Morimoto, K. Review of the occupational exposure to isocyanates: mechanisms of action. Environmental health and preventive medicine 2002, 7, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Redlich, C.A.; Karol, M.H.; Graham, C.; Homer, R.J.; Holm, C.T.; Wirth, J.A.; Cullen, M.R. Airway isocyanate-adducts in asthma induced by exposure to hexamethylene diisocyanate. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health 1997, 227-231. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Association between Occupational Exposure Duration and Chronic Disease Risk. Bar plot showing the prevalence of chronic diseases across different exposure duration groups. The x-axis represents exposure groups (Group 1: 1-2 years, Group 2: 3-5 years, Group 3: 6-8 years, and Group 4: 8+ years), while the y-axis shows the percentage of workers with chronic diseases. A significant increase in chronic disease prevalence is observed in Group 4 (21.1%) compared to Group 1 (5.7%), representing a 3.7-fold increase in risk (p = 0.00553, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Figure 1.

Association between Occupational Exposure Duration and Chronic Disease Risk. Bar plot showing the prevalence of chronic diseases across different exposure duration groups. The x-axis represents exposure groups (Group 1: 1-2 years, Group 2: 3-5 years, Group 3: 6-8 years, and Group 4: 8+ years), while the y-axis shows the percentage of workers with chronic diseases. A significant increase in chronic disease prevalence is observed in Group 4 (21.1%) compared to Group 1 (5.7%), representing a 3.7-fold increase in risk (p = 0.00553, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Figure 2.

Blood parameters across different exposure periods. Bar plot revealed significant differences in blood parameters across exposure group. Each panel represents one parameter—white blood cell count (WBC), platelet count (PLT), albumin (ALB), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT). The x-axis represents exposure groups (Group 1: 1-2 years, Group 2: 3-5 years, Group 3: 6-8 years, and Group 4: 8+ years), while the y-axis shows the mean unit of blood parameters.

Figure 2.

Blood parameters across different exposure periods. Bar plot revealed significant differences in blood parameters across exposure group. Each panel represents one parameter—white blood cell count (WBC), platelet count (PLT), albumin (ALB), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT). The x-axis represents exposure groups (Group 1: 1-2 years, Group 2: 3-5 years, Group 3: 6-8 years, and Group 4: 8+ years), while the y-axis shows the mean unit of blood parameters.

Figure 3.

(a) Exposure-related Changes in common compounds Levels During pesticides exposure. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for Group 1 (1-2 years, n=52), Group 2 (3-5 years, n=44), Group 3 (6-8 years, n=26), and Group 4 (8+ years, n=128). Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction. The y-axis represents the mean peak area. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM) above the mean. (b) Exposure-related Changes in common compounds Levels During pesticides exposure.

Figure 3.

(a) Exposure-related Changes in common compounds Levels During pesticides exposure. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for Group 1 (1-2 years, n=52), Group 2 (3-5 years, n=44), Group 3 (6-8 years, n=26), and Group 4 (8+ years, n=128). Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni correction. The y-axis represents the mean peak area. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM) above the mean. (b) Exposure-related Changes in common compounds Levels During pesticides exposure.

Figure 4.

Relationship between common compounds and serum albumin levels across different exposure durations. Mean serum albumin concentrations (g/L) are plotted against mean compounds areas (in millions) for four exposure groups: 1-2 years (gray, n=52), 3-5 years (blue, n=44), 6-8 years (orange, n=25), and 8+ years (red, n=127). The blue line represents the linear regression fit, with the shaded area indicating the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Relationship between common compounds and serum albumin levels across different exposure durations. Mean serum albumin concentrations (g/L) are plotted against mean compounds areas (in millions) for four exposure groups: 1-2 years (gray, n=52), 3-5 years (blue, n=44), 6-8 years (orange, n=25), and 8+ years (red, n=127). The blue line represents the linear regression fit, with the shaded area indicating the 95% confidence interval.

Table 1.

Hematological and Biochemical Parameters across different exposure groups.

Table 1.

Hematological and Biochemical Parameters across different exposure groups.

| Parameter |

Study groups (exposure period) |

| 1-2 years |

3-5 years |

6-8 years |

8+ years |

| WBC (×10³/ΜL) |

6.93± 0.26 |

8.30± 0.39 |

7.23± 0.36 |

7.05± 0.19 |

| RBC (×10⁶/μL) |

5.67± 0.10 |

5.73± 0.09 |

5.55± 0.07 |

5.45± 0.08 |

| HGB (g/dL) |

14.61± 0.29 |

14.85± 0.17 |

14.74± 0.19 |

14.19± 0.22 |

| HCT (%) |

45.67± 0.75 |

45.43± 0.59 |

45.49± 0.64 |

43.93± 0.66 |

| PLT (×10³/μL) |

345.92± 10.58 |

298.20± 10.61 |

338.88± 14.95 |

333.68± 9.19 |

| MCV (FL) |

81.59 ± 1.20 |

80.51 ± 1.10 |

82.99 ± 1.11 |

79.43 ± 1.14 |

| MCH (PG) |

25.68 ± 0.44 |

26.05 ± 0.44 |

26.68 ± 0.39 |

25.92 ± 0.49 |

| ALB (g/L)* |

40.20± 0.59 |

39.80± 0.59 |

39.41± 0.79 |

37.95± 0.50* |

| GGT (U/L)* |

50.35± 3.26 |

39.05± 2.38 |

49.42± 5.23 |

57.83± 2.91 |

| TP (g/L) |

76.84± 0.89 |

74.94± 1.11 |

74.47± 1.45 |

74.76± 0.87 |

| ALPI (U/L) |

86.40± 3.72 |

83.91± 3.41 |

83.76± 5.95 |

90.54± 2.27 |

| AST (U/L) |

25.56± 1.15 |

26.89± 1.88 |

23.36± 1.31 |

26.03± 0.79 |

| ALTI (U/L) |

47.21± 2.64 |

45.02± 5.66 |

46.64± 5.15 |

47.39± 1.76 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).