Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

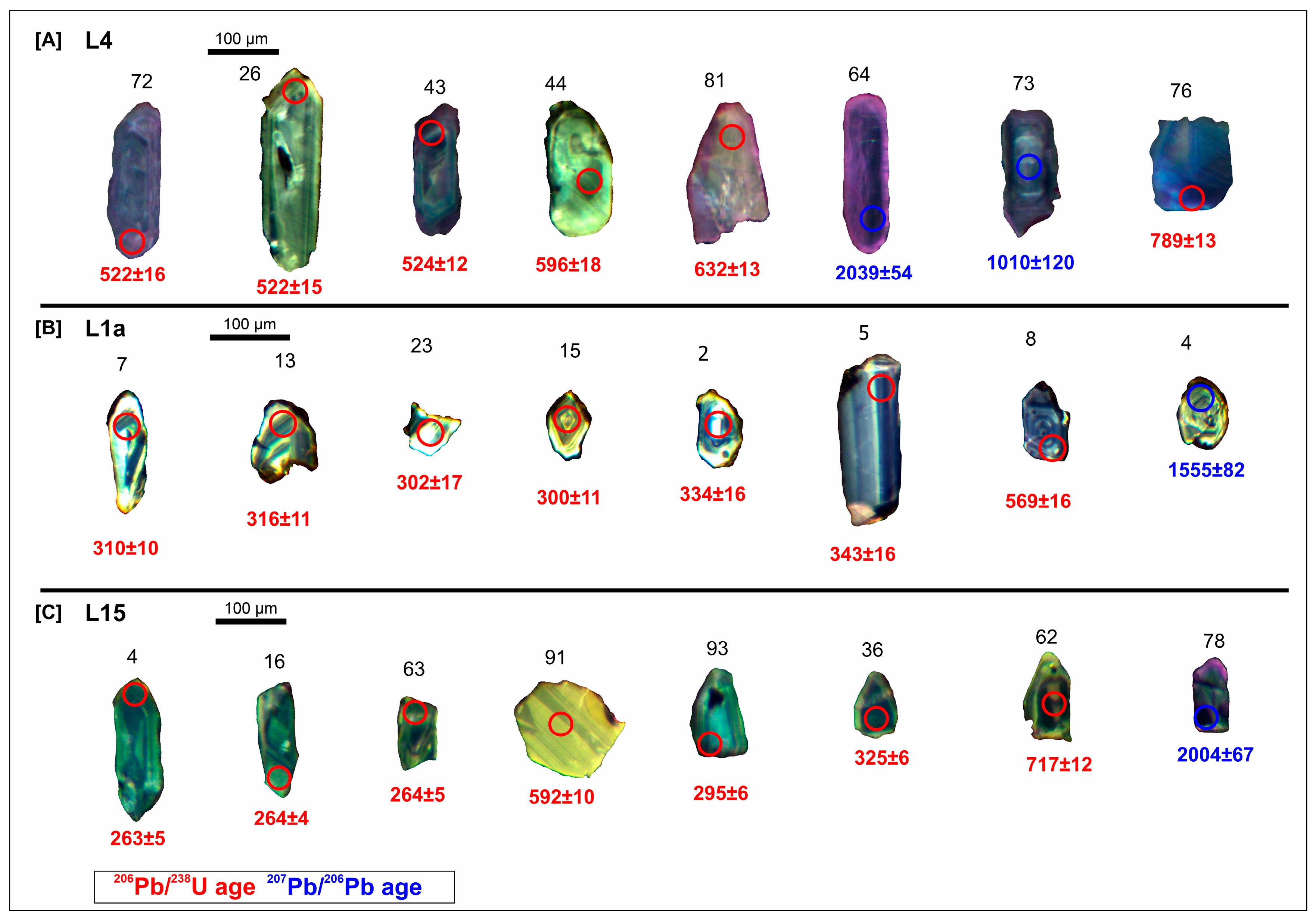

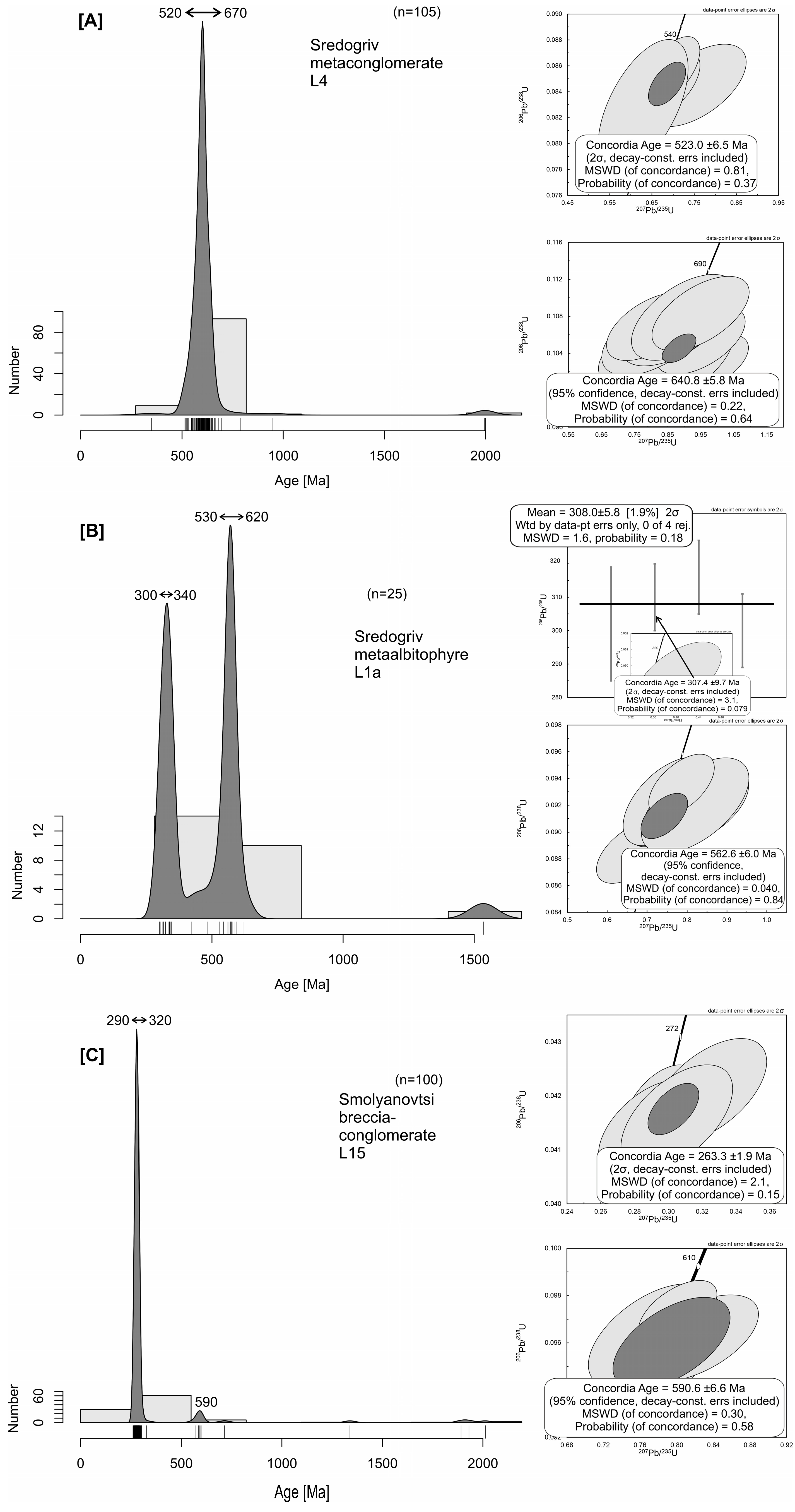

The Sredogriv greenschist facies rocks belong to the Western Balkan Zone in northwestern Bulgaria. The low-grade rocks consist of clastic-tuffaceous precursors and presumably olistostromic magmatic bodies. We present U-Pb LA-ICP-MS zircon age constraints for the Sredogriv metaconglomerate, intruding metaalbitophyre and a breccia-conglomerate of the sedimentary cover. Detrital zircons in the Sredogriv metaconglomerate yielded a maximum depositional age of 523 Ma, with a prominent Neoproterozoic-Early Cambrian detrital zircon age clusters derived from igneous sources. The metaalbitophyre crystallized at 308 Ma and contains the same age clusters of inherited zircons. A maximum age of deposition is defined at 263 Ma for a breccia-conglomerate of the Smolyanovtsi Formation from the sedimentary cover that recycled material from the Sredogriv metamorphics and Carboniferous-Permian magmatic rocks. Proximity to Cadomian island arc sources and provenance from the northern periphery of Gondwana outline the depositional setting of the Sredogriv sedimentary succession. The timing of the Variscan greenschist facies metamorphism of the Sredogriv metamorphics is bracketed between 308 Ma and the depositional age of 272 Ma of another adjacent clastic formation. The results obtained allow us to identify the timing of the Cadomian sedimentary history and the Variscan magmatic and tectono-metamorphic evolution in part of the Western Balkan Zone.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting and Field Observations

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. U-Pb Geochronology

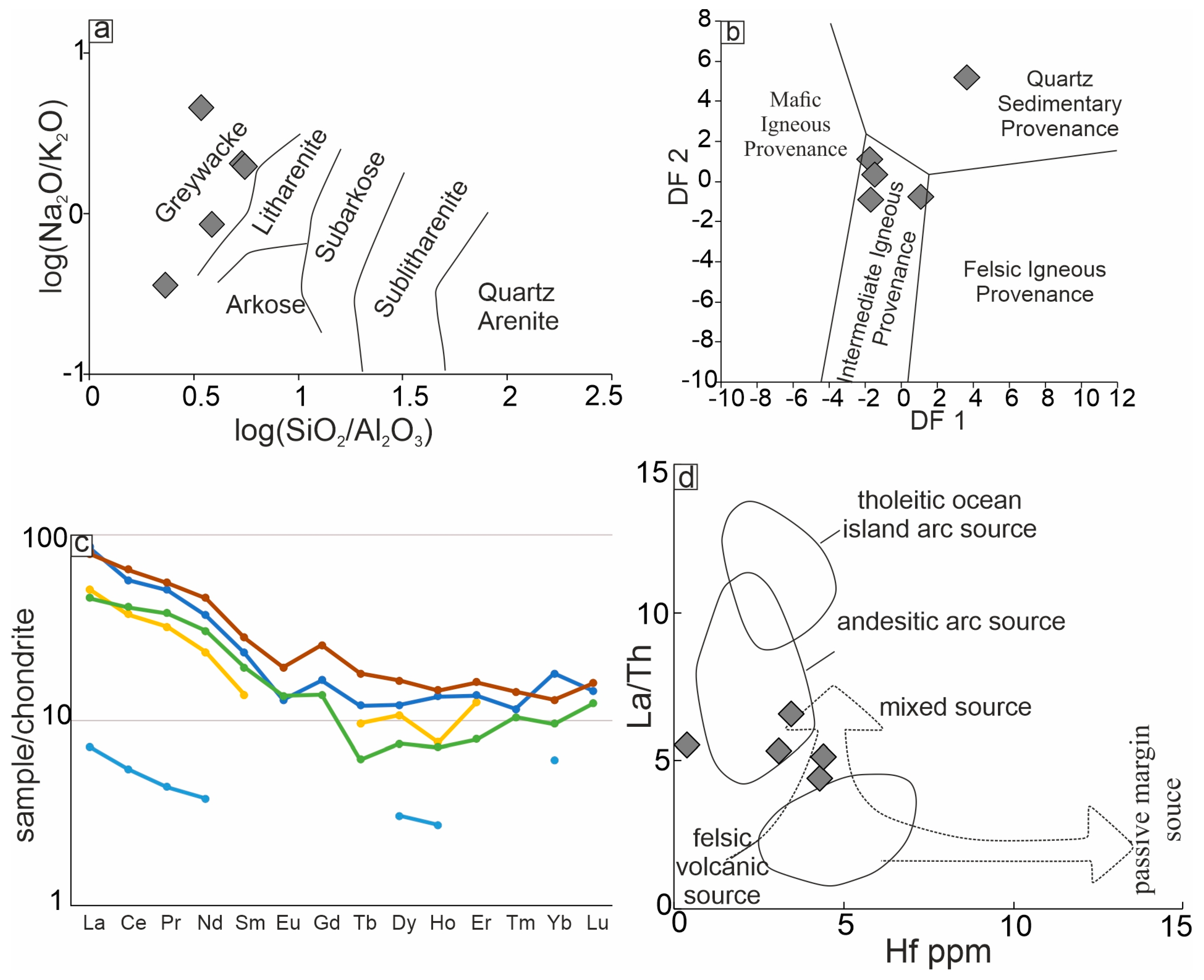

4.2. Whole-Rock Geochemistry

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haydoutov, I. Precambrian ophiolites, Cambrian Island arc and Variscan suture in the South Carpathian-Balkan region. Geology 1989, 17, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydoutov, I.; Yanev, S. The Protomoesian microcontinent of the Balkan Peninsula- a peri-Gondwanaland piece. Tectonophysics 1997, 272, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydoutov, I. Pristavova, S.; Daieva, L-A.Some features of Neoproterozoic-Cambrian geodynamics in Southeastern Europe. C. R. Acad. bulg. Sci. 2010, 63, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Žák, J.; Svojtka, M.; Gerdjikov, I.; Vangelov, D.A.; Kounov, A.; Sláma, J.; Kachlík, V. In search of the Rheic suture: detrital zircon geochronology of Neoproterozoic to Lower Paleozoic metasedimentary units in the Balkan fold-and-thrust belt in Bulgaria. Gond. Res. 2023, 121, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savov, I.; Rayan, J; Haydoutov, I.; Schijf, J. Late Precambrian Balkan-Carpathian ophiolite – a slice of Pan-African ocean crust? Geochemical and tectonic insights from the Tcherni Vrah and Deli Jovan massifs, Bulgaria and Serbia. J. Volc. Geoth. Res. 2001, 110, 299–318.

- Carrigan, C.; Mukasa, S.B.; Haydoutov, I.; Kolcheva, K. Neoproterozoic magmatism and Carboniferous high-grade metamorphism in the Sredna Gora Zone, Bulgaria: An extension of Gondwana-derived Avalonian-Cadomian belt? Prec. Res. 2006, 147, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, C.; Mukasa, S.; Haydoutov, I.; Kolcheva, K. Age of Variscan magmatism from the Balkan sector of the orogen, central Bulgaria. Lithos 2005, 82, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žák, J.; Svojtka, M.; Gerdjikov, I.; Ackerman, L.; Kachlík, V.; Sláma, J.; Vangelov, D.A.; Kounov, A. New U-Pb zircon ages from Cadomian basement of the Balkan fold-and-thrust belt of northern Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2024, 85, 3, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorchev, I. On the Early Paleozoic orogeneses in Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2024, 85, 3, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yanev, S. Paleozoic terranes of the Balkan Peninsula in the framework of Pangea assembly. Paleogeogr. Paleoclim. Paleoecol. 2000, 161, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesogno, L; Gaggero,L.; Ronchi, A.; Yanev, S. Late orogenic magmatism and sedimentation within Late Carboniferous to early Permian basins in the Balkan terrane (Bulgaria): geodynamic implications. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2004, 93, 500–520.

- Dyulgerov, M.; Ovtcharova-Schaltegger, M; Ulianov, A.; Schaltegger, U. Timing of high-K alkaline magmatism in the Balkan segment of southeast European Variscan edifice: ID-TIMS and LA-ICP-MS study. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2018, 107, 1175–1192.

- Georgiev, S.; Lazarova, A.; Balkanska, E.; Naydenov, K., Broska, I.; Kurylo, S. Time constraints on the Variscan magmatism along Iskar River Gorge and Botevgrad basin, Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2024, 85, 2, 159–162.

- Boncheva, I.; Lakova, I.; Sachanski, V.; Koenigshof, P. Devonian stratigraphy, correlations and basin development in the Balkan terrane, western Bulgaria. Gond. Res. 2010, 17, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velichkova, S.H.; Handler, R.; Neubauer, F.; Ivanov, Z. Variscan to Alpine tectonothermal evolution of the Central Srednogorie unit, Bulgaria: constraints from 40Ar/39Ar analysis. Schweiz. Meneral. Petr. Mitt. 2004, 84, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Dabovski, Ch.; Zagorchev, I. Chapter 5.1. Introduction: Mesozoic evolution and alpine structure. In Geology of Bulgaria. Volume 5 part 2. Mesozoic geology; Zagorchev, I. Dabovski, Ch., Nikolov, T. Eds.; Academic Publishing House “Marin Drinov”, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2009, pp. 13–37. (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Ivanov, Z. Tectonics of Bulgaria. Sofia University Press, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017, pp. 331 (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Žák, J.; Svojtka, M.; Gerdjikov, I.; Kounov, A.; Vangelov, D.A. The Balkan terranes: a missing link between the eastern and western segments of the Avalonian-Cadomian orogenic belt? Int. Geol. Rev. 2022, 64, 2389–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, S. Diabase rocks in Iskar gorge between the railroad station Bov and stop Lakatnik. Ann. Univ. Sofia Fac. Phys. Mat. Fac. 1929, 25, 175–273, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjiev, S. On the diabase-phyllitoid complex in Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 1970, 31, 1, 63–74, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Z.; Kolcheva, K.; Moskovski, S.; Dimov, D. 1987.On the particularities and character of the “Diabase-Phyllitoid Formation”. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 1987, 48, 1–24, (in Bulgarian with French abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Kalvacheva, R. Palynology and stratigraphy of the Diabse-Phyllitoid complex in the West Balkan Mountains. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 1982, 33, 1, 8–24, (in Russian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, S.; Popov, M.; Balkanska, E.; Gerdjikov, I.; Vangelov, D. First U-Pb zircon geochronology data of the diabases from the Lower Paleozoic section along Iskar and Gabrovnitsa River valleys. Proceedings of National Conference with international participation “GEOSCIENCES 2016”, Sofia, Bulgaria, 7-8 December 2016, Bulgarian Geological Society, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016, 55–56.

- Haidutov, I.; Tenchov, Y.; Janev, S. Lithostratigraphic subdivision of the Diabase-Phyllitoid complex in the Berkovica Balkan Mountain. Geologica Balc. 1979, 9, 13–25, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Haydoutov, I. Origin and evolution of the Precambrian Balkan-Carpathian ophiolitic segment. Publishing house of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991, 176 p. (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Haydoutov, I.; Daieva, L.; Nedyalkova, S. Data on the composition and structure of the Stara Planina ophiolite association in Chiprovtsi region. Geotect. Tectonophys. Geodyn, Sofia 1985, 21, 14–25, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Von Quadt, A.; Peytcheva, I.; Haydoutov, I. 1998.U-Pb dating of Tcherni Vrah metagabbro, West Balkan, Bulgaria. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1998, 51, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kiselinov, H.; Georgiev, S.; Vangelov, D.; Gerdjikov, I.; Peytcheva. I. Early Devonian Carpathian-Balkan ophiolite formation: U–Pb zircon dating of Cherni Vrah gabbro, Western Balkan, Bulgaria. Proceedings of National Conference with international participation “GEOSCIENCES 2017”, Sofia, Bulgaria, 7-8 December 2017, Bulgarian Geological Society, Sofia, 2017, 59-60.

- Zakariadze, G.; Karamata, S.; Korikovsky, S.; Ariskin, A.; Adamia, S.; Chkhotua, T.; Sergeev, S.; Solov’eva, N. The early-middle Paleozoic oceanic events along the southern European margin: the Deli Jovan ophiolite massif (NE Serbia) and paleo-oceanic zones of Great Caucasus. Turkish J. Earth Sci. 2012, 21, 635–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balica, C.; Balintoni, I.; Berza, T. On the age of the Carpathian-Balkan pre-Alpine ophiolite in SW Romania, NE Serbia and NW Bulgaria. In: Proceedings of XX Congress of the Carpathian-Balkan Geological Association, Tirana, Albania. Buletini i Shkencave Gjeologjike, Special Issue 1, 2014, 196–197.

- Plissart, G.; Ch. Monnier, Ch.; Diot, H.; Maruntiu, M.; Berger, J.; Triantafyllou, A. Petrology, geochemistry and Sm-Nd analyses on the Balkan-Carpathian Ophiolite (BCO – Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria): Remnants of a Devonian back-arc basin in the easternmost part of the Variscan domain. J. Geodyn. 2017, 105, 27–50. [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, C.; Mukasa, S.; Haydoutov, I.; Kolcheva, K. Ion microprobe U-Pb zircon ages of pre-Alpine rocks in the Balkan, Sredna Gora, and Rhodope terranes of Bulgaria: Constraints on Neoproterozoic and Variscan tectonic evolution. J. Czech Geol. Soc. 2003, 48/1-2, 32–33.

- Angelov, V., Antonov, M.; Gerdjikov, S.; Klimov, I.; Petrov, P.; Kiselinov, H.; G. Dobrev, G. Explanatory note of geological map of Bulgaria, scale 1:50 000, sheet Rujinzi, (eds. V. Angelov and Ch. Chrischev), Sofia, Bulgaria, Geocomplex, 2006a,107 p. (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Angelov, V., Antonov, M.; Gerdjikov, S.; Klimov, I.; Petrov, P.; Kiselinov, H.; G. Dobrev, G. Explanatory note of geological map of Bulgaria, scale 1:50 000, sheets Knjazevats and Belogradchik, (eds. V. Angelov and Ch. Chrischev), Sofia, Bulgaria, Geocomplex, 2006b,115 p. (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Moskovski, S.; Nedyalkova, S.; Harkovska, A.; Tenchov, Y.; Shopov, V.; Yanev, S. Stratigraphic and lithologic investigations in the core and part of the mantle of the Mihaylovgrad antcline between the rivers Chuprenska and Rikovska bara (Northwest Bulgaria). Travaux sur la géologie de Bulgarie, ser. Stratigr. Tect. 1963, 5, 29–67, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Kounov, A. Petrologic arguments for the assignment of the so-called Pesochnishka and Sredogrivska formations to the Diabase-Phyllitoid Formation. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 1973, 35, 203–207, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bonchev, S. Geology of the Western Stara Planina. II. The main lines of geological structure of the Western Stara Planina. Trudove na Bulgarskoto pririodno drujestvo 1910, 4, 1–59. (in Bulgarian).

- Haydoutov, I. Notes on the tectonomagmatic evolution of the and evolution of the Stara Planina eugeosyncline during the Phanerozoic. Bull. Geol. Inst. ser. Geotect. 1973, 21, 5–20, (in Bulgarian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Kiselinov, H. Tectonic structure and evolution of the Sredogriv metamorphics. Ph.D. thesis, Geological institute Strashimir Dimitrov, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2011, 215 p. (in Bulgarian).

- Kiselinov, H. Evolution of the Paleozoic (Silurian-Devonian?) Sredogriv metamorphics, NW Bulgaria. Geol. Balc. 2024, 53, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselinov, H.; von Quadt, A.; Peytcheva, I.; Pristavova, S. U-Pb dating and field relationships of the Protopopintsi metagranite with the Sredogriv metamorphites (NW Bulgaria). Compt. Rend. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 2009, 62, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Haydoutov, I.; Pristavova, S.; Daieva, L.-A. Late Neoproterozoic-Early Paleozoic evolution of the Balkan terrane (SE Europe) – a probable fragment of the Iapetus Ocean. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012, 132 pp. (in Bulgarian with English abstract).

- Jackson, S.E.; Pearson, N.J.; Griffin, W.L.; Belousova, E.A. , 2004, The application of laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry to in situ U–Pb zircon geochronology. Chem. Geol. 2004, 211, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sláma, J.; Košler, J.; Condon, D.J.; Crowley, J.L.; Gerdes, A.; Hanchar, J.M.; Whitehouse, M.J. 2008, Plešovice zircon – a new natural reference material for U–Pb and Hf isotopic microanalysis. Chem. Geol. 2008, 249, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenbeck, M.; Alle, P.; Corfu, F.; Griffin, W.; Meier, M.; Oberli, F.; Quadt, A.V.; Roddick, J.; Spiegel, W. Three natural zircon standards for U-Th-Pb, Lu-Hf, trace element and REE analyses. Geost. Newslett. 1995, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, C.; Hellstrom, J.; Paul, B.; Woodhead, J.; Hergt, J. Iolite: freeware for the visualization and processing of mass spectrometric data. J. Analytic. Atomic Spectr. 2011, 26, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. User’s Manual for Isoplot/Ex, Version 4.15. A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Berkeley Geochronology Center Special Publication No. 4, 2011, 2455 Ridge Road, Berkeley, CA 94709, USA.

- Rubatto, D. Zircon trace element geochemistry: partitioning with garnet and the link between U-Pb ages and metamorphism. Chem. Geol. 2002, 184, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiepel, U.; Eichhorn, R.; Loth, G.; Rohrmülle, J.; Höll, R.; Kennedy, A. U-Pb SHRIMP and Nd isotopic data from the western Bohemian Massif (Bayerischer Wald, Germany): Implications for Upper Vendian and Lower Ordovician magmatism. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2004, 93, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The continental crust: its composition and evolution. 1985, Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 312. [CrossRef]

- Pettijohn, F.J; Potter, P.E.; Siever, R. Sand and Sandstone. 1972, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 553.

- Roser, B.P.; Korsch, R.J. Provenance signatures of sandstone-mudstone suites determined using determiantion function analysis of major element data. Chem. Geol. 1988, 67, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, P.A; Leveridge, B.E. Tectonic environment of Devonian Gramscatho basin, south Cornwell: framework mode and geochemical evidence from turbiditic sandstones. J. Geol. Soc. London. 1987, 144, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Young, G.M. Prediction of some weathering trends of plutonic and volcanic rocks based on thermodynamic and kinetic considerations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1984, 48, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M.; Hemming, S.; McDaniel, D.K.; Hanson, G.N. Geochemical approaches to sedimentation, provenance and tectonics. In Processes Controlling the Composition of Clastic Sediments; Johnson, M.J., Basu, A. Eds.; Geol. Soc. Am. Sp. Pap. 1993, 284, London, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.R.; Crook, K.A.W. Trace element charcteristics of graywackes and tectonic setting discrimination of sedimentary basins. Contrib. Minaral. Petrol. 1986, 92, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipov, P.; Bonev, N.; Vladinova, T.; Kalchev, R.; Georgiev, S.; Macheva, L.; Georgieva, H.; Vlahov, A.; Morin, G. U-Pb detrital zircon geochronology of the late Paleozoic-early Mesozoic sedimentary successions from the Belogradchik Unit in the West Fore-Balkan, NW Bulgaria. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2024, 85, 2, 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Matte, P. Tectonics and plate tectonics model for the Variscan belt in Europe. Tectonophysics 1986, 126, 329–374. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, W. The mid-European segment of the Variscides: tectonostratigraphic units, terrane boundaries and plate tectonic evolution. In Orogenic Processes: Quantification and Modelling the Variscan belt; Franke, W., Haak, V., Oncken, O., Tanner, D., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publication, London, UK 2000, Volume 179, pp. 35–61.

- von Raumer, J.F.; Stampfli, G.M; Busy, F. Gondwana-derived microcontinents – the constituents of Variscan and Alpine collisional orogens. Tectonophysics 2003, 365, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfli, G.M; Kozur, H.W. Europe from the Variscan to the Alpine cycles. In European Lithosphere Dynamics; Gee, D.G., Stephenson, R.A., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Memoirs, London, UK, 2000 Volume 32, pp. 57–82.

- Kroner, U.; Romer, R.L. Two plates-Many subduction zones: The Variscan orogeny reconsidered. Gond. Res. 2013, 24, 298–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, T; Kroner, U.; Romer, R.L.; Rösel, D. From a bipartite Gondwanan shelf to an arcuate Variscan belt: The early Paleozoic evolution of northern peri-Gondwana. Earth Sci. Rev. 2019, 192, 491–512.

- Okay, A.I.; Topuz, G. Variscan orogeny in the Black Sea region. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2017, 106, 569–592. [Google Scholar]

- Okay, A.I.; Nikishin, A.M. Tectonic evolution of the southern margin of Laurasia in the Black Sea region. Int. Geol. Rev. 2015, 57, 1051–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).