1. Introduction

Deforestation, is a critical environmental problem that currently attracts the attention of researchers, policy makers, and the general public. The problem is particularly important in tropical regions, where high rates of deforestation have led to significant losses of biodiversity, also contributing to global climate change [

1]. Numerous studies have investigated the causes of deforestation, as well as proposed solutions to mitigate its expansion. Laurence et al. [

2] identifies key drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, including population growth, industrial activities, road construction, and human-induced wildfires. According to Barber et al. [

3], deforestation in the Amazon forest is strongly associated with proximity to roads and rivers, while protected areas help to prevent it. Colman et al. [

4], on the other hand, argue that the rate of deforestation in the Cerrado has been historically higher than in the Brazilian Amazon, being the conversion of native vegetation areas in agriculture over the last 30 years the main driver of these changes. Given their crucial role in global climate stability, addressing deforestation is essential for protecting such unique ecosystems and safeguarding the planet’s well-being.

Fortunately, advances in remote sensing technology have improved monitoring capabilities. Hansen et al. [

5] mapped global forest loss, finding tropical regions, including the Amazon, the most affected. In this regard, among other initiatives, the PRODES project stands out as a key program for monitoring deforestation in Brazil. Developed by the Brazilian Space Research Institute (INPE), it uses optical satellite data to track deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and other biomes, providing reliable information on deforestation trends, aiding environmental management.

Jiang et al. [

6] highlights that deep learning (DL) techniques have recently become a leading approach in various fields, including remote sensing. Nonetheless, DL models typically need extensive labeled datasets to be trained, and producing such reference data is expensive and time-consuming, demanding field surveys and expert image interpretation. Additionally, environmental dynamics, geographical differences, and sensor variations restrict the application of pre-trained classifiers to new data, leading to reduced accuracy. These challenges exemplify what is called as the domain shift, when source domain data marginal distribution differs substantially from the one of the target domain. Domain shift as well as the high demand for labeled training data hampers the implementation of broad scale, real-world, DL-based remote sensing applications.

When considering deforestation as a single process, it is necessary to include not only the extremes of the process, like clear-cutting, which are more obvious and easier to identify, but also the forest degradation gradient that occurs throughout the deforestation process. This degradation can occur slowly over time due to continuous logging and successive occurrences of forest fires. Despite various classifications found in other literature, the methodology employed by PRODES [

7] condenses the distinct types of deforestation into the two above-mentioned main categories, i.e., clear-cutting and degradation.

As documented by IBGE [

8], the predominant vegetation in the Amazon is the dense ombrophilous forest, which represents 41.67% of the biome. This type of forest is densely wooded, with tall trees, a wide range of green hues, and high rainfall (less than 60 dry days per year). Another type of vegetation present is the open ombrophilous forest. It features vegetation covered with palm forests throughout the Amazon and even beyond its borders, along with bamboo in the western part of the Amazon. Unlike the dense ombrophilic forest, it has lower rainfall. In the Brazilian Cerrado biome, there is a mixture of forest, savanna, and grassland formations. The biome is characterized by scattered trees and shrubs, small palms, and a grass-covered soil layer [

9].

The distinct differences among various biomes pose a significant challenge for DL models when applied to deforestation detection. Rainforests, savannas, and grasslands, exhibit unique ecological characteristics, including diverse types of vegetation, terrain variations, and weather patterns. These variations introduce considerable variability in the visual features present in satellite images, making it difficult for a model trained on one biome to generalize effectively to others.

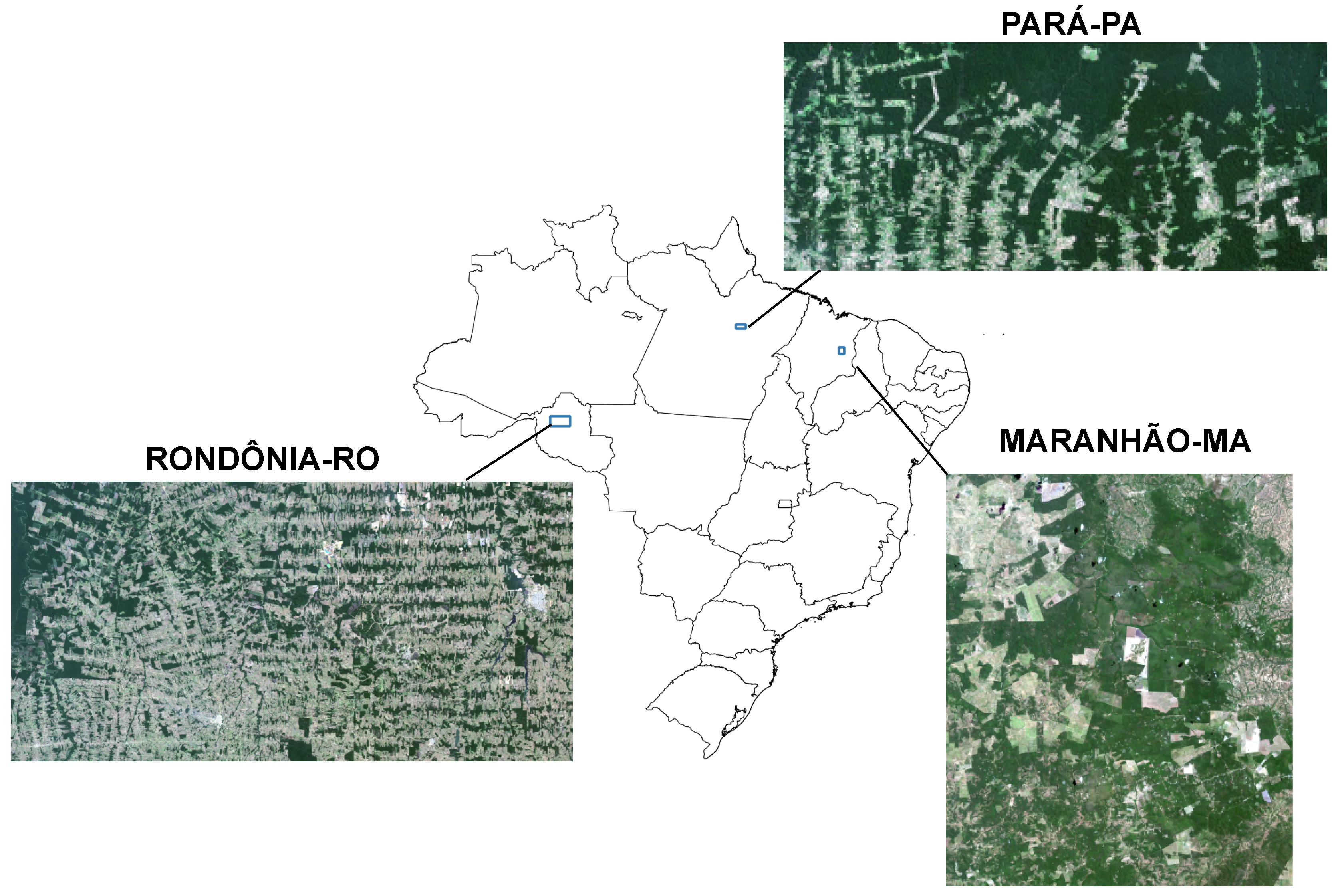

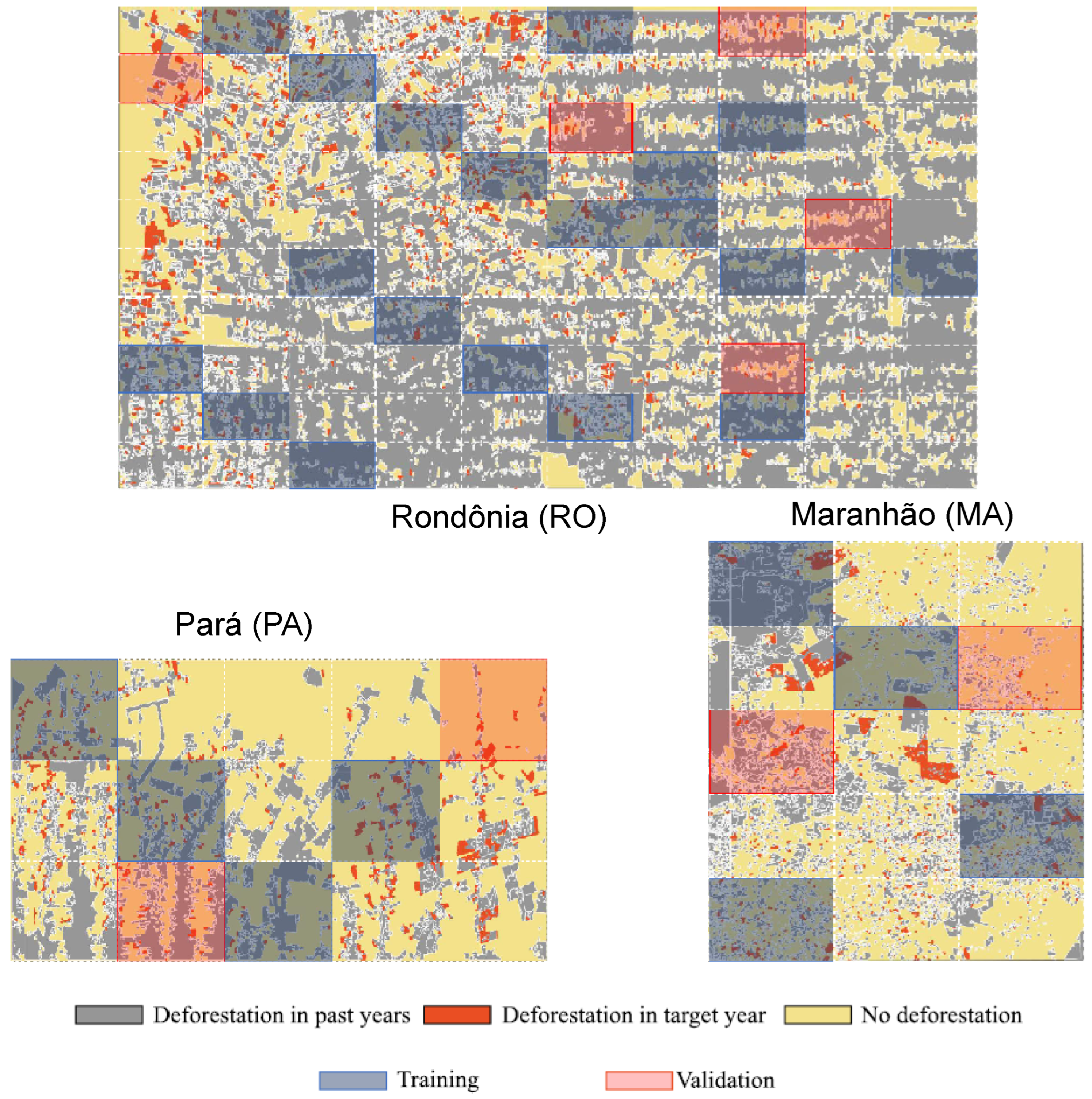

In this study, our focus is on imagery from two distinct Amazonian locations, Pará (PA) and Rondônia (RO), and one site situated within the Cerrado biome, Maranhão (MA). Each site exhibits distinct patterns of deforestation, characterized by varying distributions of deforestation types. According to [

10], clear-cutting with exposed soil is the predominant form of deforestation in Pará, Rondônia, and Maranhão. However, the extent of this practice varies significantly across those regions. In Maranhão, clear-cutting with exposed soil is dominant. In contrast, Pará and Rondônia show a more balanced distribution, with significant contributions from progressive degradation with vegetation retention. Additionally, Pará stands out for having a small but noteworthy proportion of deforestation attributed to mining activities.

Several studies have explored domain adaptation (DA) methods for deforestation detection from remote sensing data. Soto Vega et al. [

11] proposed an unsupervised DA approach based on the CycleGAN [

12], which transforms target domain images, so that they resemble source domain images while preserving semantic structure. Noa et al. [

13] introduced a domain adaptation method based on Adversarial Discriminative Domain Adaptation (ADDA) [

14] for semantic segmentation, which incorporates a domain discriminator network during training. Soto et al. [

15] developed a DA method derived from Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN) [

16], integrating change detection and patch-wise classification, and employing pseudo-labels to address class imbalance. Vega et al. [

17] introduced the Weakly-Supervised Domain Adversarial Neural Network method for deforestation detection, which uses the DeepLabv3+ architecture [

18]. This approach uses pseudo-labels both for dealing with class imbalance, and for a form of weak supervision to enhance the accuracy of domain adaptation models.

While those methods demonstrated effectiveness in single-source, single-target settings, none of them addressed multi-source or multi-target scenarios in a semantic segmentation task, a gap that this study aims to fill. In terms of uncertainty estimation, Martinez et al. [

19] evaluated uncertainty estimation techniques and introduces a novel method to improve deforestation detection. By integrating uncertainty estimation into a semiautomatic framework, the approach flags high-uncertainty predictions for visual, expert review. This study provided a strong foundation for this work, reinforcing the use of predictive entropy from an ensemble of DL models.

The method introduced in this work aims at tackling the above-mentioned problems in the context of deforestation detection with deep learning models, in a partially assisted strategy. We propose a two-phase approach, called Dense Multi-Domain Adaptation (DMDA). In the first phase, extending the Domain Adaptation Neural Networks (DANN), a pixel-wise classifier is trained using the a particular DL architecture, combined with DA techniques to enable unsupervised training for deforestation prediction across different target domains. In the multi-target setting, a single labeled source domain is used to adapt to multiple unlabeled target domains. In the multi-source DA setting, the method adapts from multiple labeled source domains to a single unlabeled target domain.

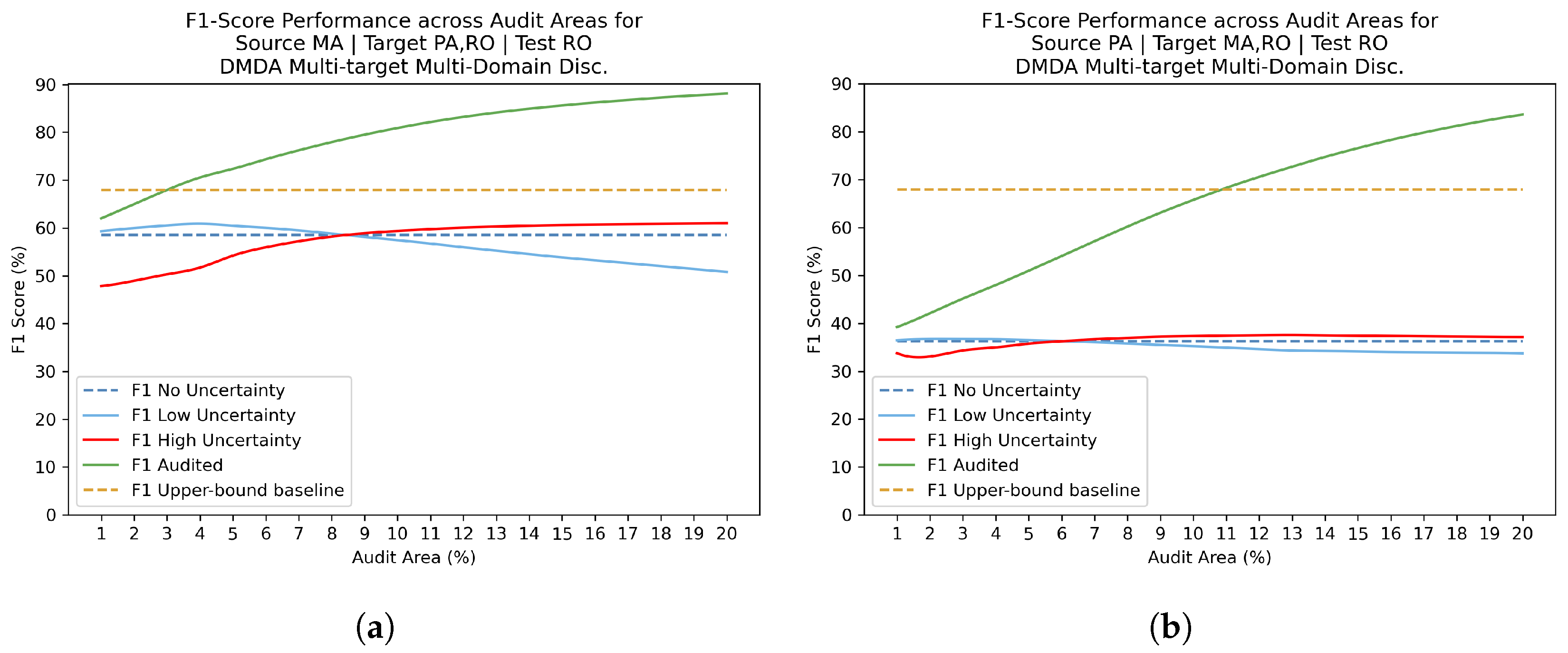

In the second phase, following the method proposed by Martinez et al. [

19], the prediction of the model is supplemented by expert auditing, focusing on areas with high uncertainty, determined by an uncertainty threshold. The predictions for each pixel in the target domain are used to calculate the entropy, which is used to identify high-uncertainty regions for further human visual inspection. Once this inspection is completed, we assume that the predictions for the selected areas of high uncertainty are accurate, and we recalculate recall, precision, and F1 score metrics values. The hypothesis is that the use of DA methods combined with uncertainty estimation not only improves the accuracy of the deforestation predictions in unseen domains, but also provides users with greater transparency in the reliability of the models, as well as the opportunity to manually improve its overall performance, recommending the most uncertain areas for visual inspection.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

Two distinct scenarios of domain adaptation (DA) are presented. The first, termed multi-target, involves a single source domain and multiple target domains. The second, known as multisource, consists of multiple source domains adapting to a single target domain.

Two configurations of the domain discriminator component were evaluated: multi-domain discriminator and source-target discriminator.

Inclusion and assessment of an expert audit phase designed to target areas of highest uncertainty, utilizing uncertainty estimation from the predictions made by the DL model in a domain adaptation context.

Experiments are conducted in three different domains associated with Brazilian biomes, and our approach is validated by comparing the results obtained with single-target and baseline experiments.

The remainder of this document is organized as follows. Next section presents materials and methods. Then, in

Section 3, we present the experimental procedure, while

Section 4 is dedicated to results presentation. Finally,

Section 5 is dedicated to results discussion, while

Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Domain Adversarial Neural Network (DANN)

Proposed in [

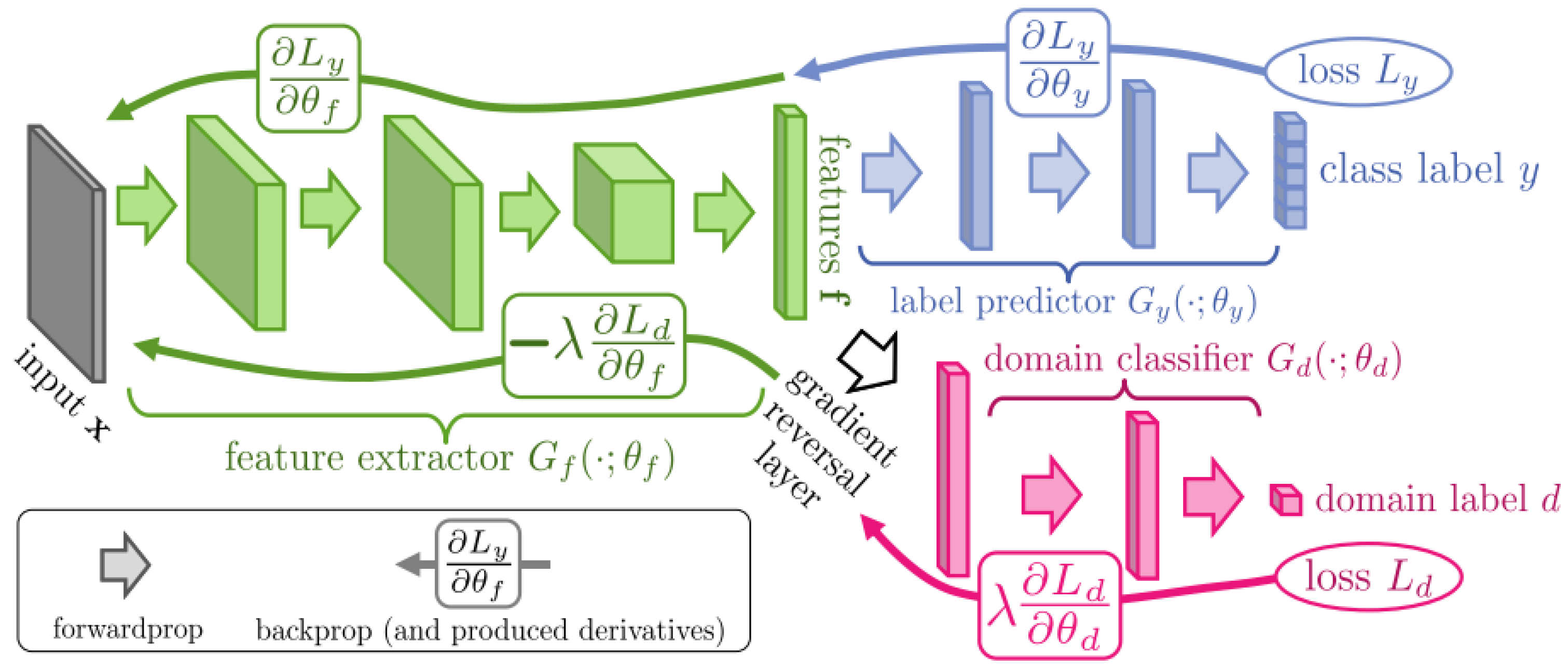

16], DANN aims to minimize the divergence between two probability distributions by learning domain-agnostic latent representations employing adversarial training. As depicted in

Figure 1, three modules compose the DANN strategy: a

feature extractor , a

label predictor and a

domain classifier . In short,

maps both the source and target learned features into a common latent space,

estimates the input sample categories, and

, used only during training, tries to discern between source and target samples from the features given by

.

In the DANN domain adaptaion startegy,

does not evaluate features coming from target domain samples, as their corresponding labels are unknown. In contrast, source and target domain features are forwarded through

, as their domain labels are known. The optimal network parameters

, and

are given by Equations (

1) and (

2):

where

represents the DANN loss function defined by:

The first term of the loss function represents the label predictor loss, and the second term is the domain classifier loss. The

coefficient controls the influence of the domain classifier over the feature extractor parameters. In [

16], the authors suggest that

should start and remain equal to zero during the first epochs allowing the domain classifier to properly learn how to discern among features of the respective domains. Afterwards, the coefficient value gradually increases through the training epochs favoring the domain classifier influence to the feature extractor in the opposite direction. As a result, the learning process updates the parameters of the model by implementing the rules detailed in Equations (

4), (

5) and (

6). We observe that

and

in the aforementioned equations are both positive. Therefore, the derivatives of

push

and

in opposite directions, configuring an adversarial training, which is expressed by the last term of Equation (

6).

This term penalizes

when

correctly identifies the domain to which an input sample belongs. DANN implements such an operation on

Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) (see

Figure 1). Summarily, during the forward procedure, the GRL acts as an identity mapping and, during the backpropagation, reverses the gradient (multiplying it by

) coming from the domain classifier.

Figure 1.

DANN proposed architecture (source: [

20]).

Figure 1.

DANN proposed architecture (source: [

20]).

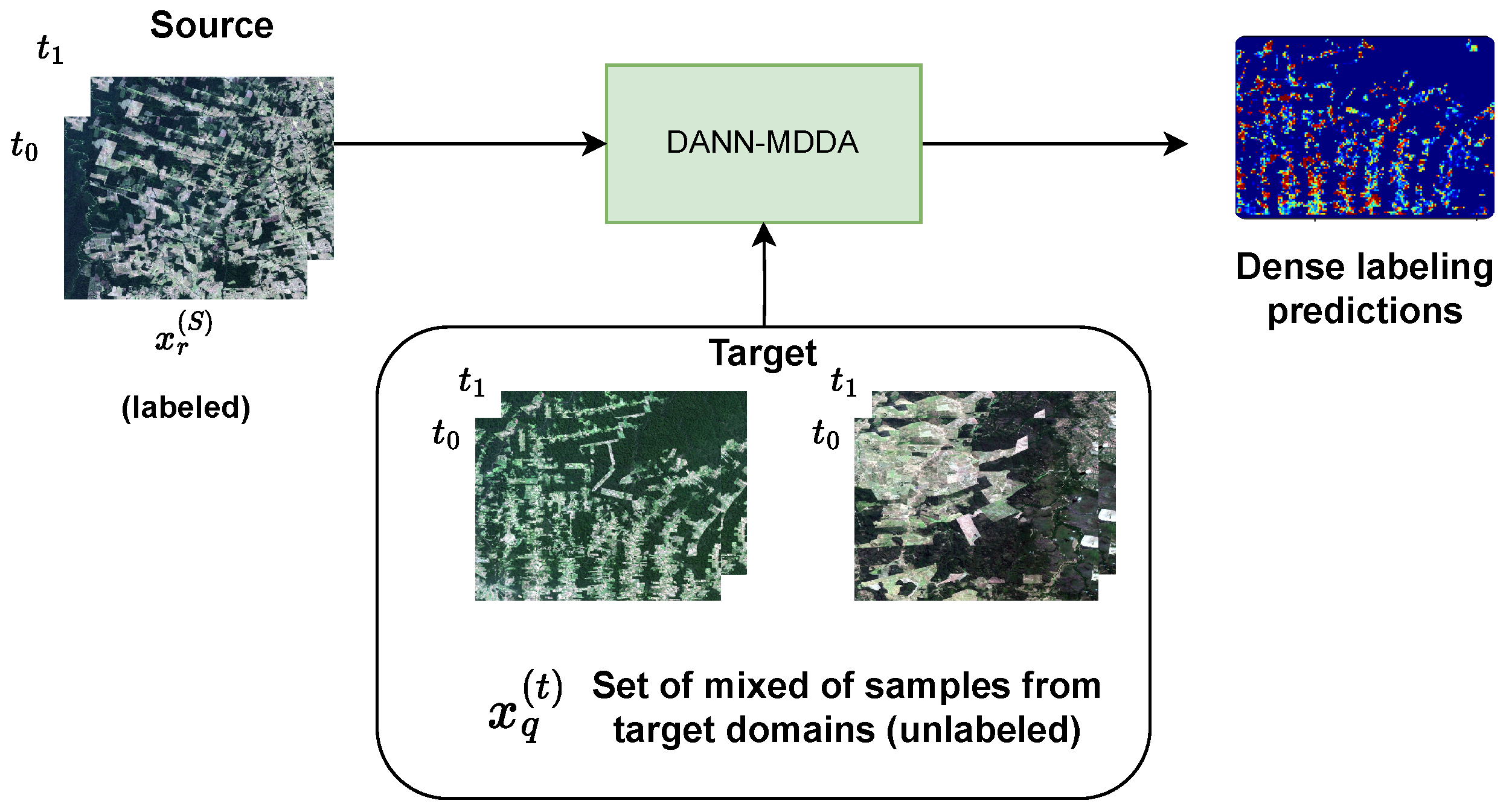

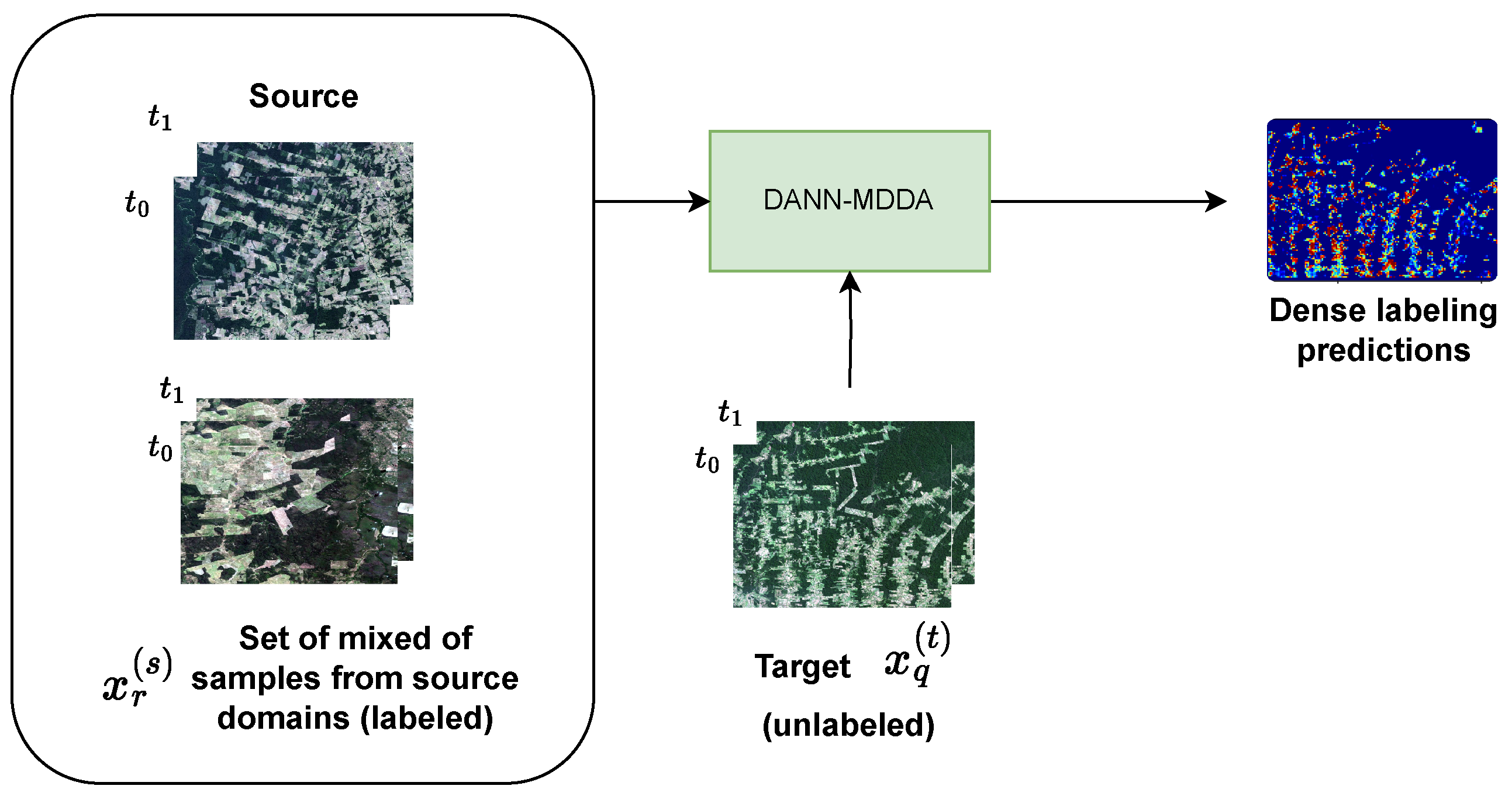

2.2. Dense Multi-Domain Adaptation

This work proposes an approach called Domain Adversarial Neural Network Dense Multi-Domain Adaptation (DANN-DMDA) to tackle the challenges of deforestation detection by exploring two settings. In the first, termed Multi-Target DA, a set of a labeled source domain is incorporated alongside multiple sets of unlabeled target domains combined into a single one for adaptation. In the second setting, known as Multi-Source DA, we combine multiple labeled source domains into a single one to adapt to a single unlabeled target domain. The hypothesis is that utilizing domain adaptation with multiple unlabeled target domains or multiple labeled source domains can improve the accuracy of deforestation prediction across these domains. Using both diverse target and source domains, the model can learn a more robust and generalized feature representation.

This work builds on the method proposed by [

21], which introduced an unsupervised domain adaptation approach for deforestation detection. Additionally, the Deeplabv3+ semantic segmentation architecture was employed, as evaluated in [

22] (please refer to

Figure 4).

Like DANN, the DANN-DMDA approach employs two adversarial neural networks: the domain discriminator and the label predictor. The architecture includes an encoder model that transforms input samples into a latent representation, a decoder responsible for semantic segmentation, and a domain discriminator that attempts to classify the domain of the encoder’s output (determining whether it belongs to the source or target domain). In the Multi-Target configuration, the encoder component receives a set of labeled samples from one source domain and unlabeled samples originating from two or more distinct target domains. Alternatively, in Multi-Source setting, the encoder is provided with labeled samples from two or more source domains, and unlabeled samples from a single target domain.

By employing such an architecture and training methodology, we aim to obtain a common feature representation shared across all domains involved, and thus improve the performance of semantic segmentation on each target domain. Although our method can be generalized to multiple target domains, we make use of two targets only to showcase the method and experiments.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate in a simplified way the blend of target and source samples for domain adaptation.

The proposed method follows the general structure outlined by [

21], which consists of three phases: data pre-processing, training, and evaluation.

First, there is a data pre-processing phase, which consists of the following procedures. The first is to apply the Early Fusion (EF) procedure, that concatenates images taken at different periods of time in the spectral dimension. Then, each image is partitioned into tiles, which are then allocated to training, validation, and test sets. From each tile, small patches are extracted to be used as input to the DANN-DMDA model.

The training phase comes in sequence. We define two distinct designs for the domain classifier model. In the first, called the multi-domain discriminator, the discriminator label space is , where each class is represented by a unique value. In the other design, named source-target discriminator, the label space is , where 0 denotes the source domain, and 1 represents the target domain. In this case, there is no discrimination between specific source or target domains. For the label predictor model, a pixel-wise weighted cross-entropy loss is adopted in order to enable a calibration over of how much weight is given to no-deforestation and deforestation predictions. The domain discriminator model works with a cross-entropy loss.The DANN-DMDA model is trained until convergence by simultaneously updating the parameter sets .

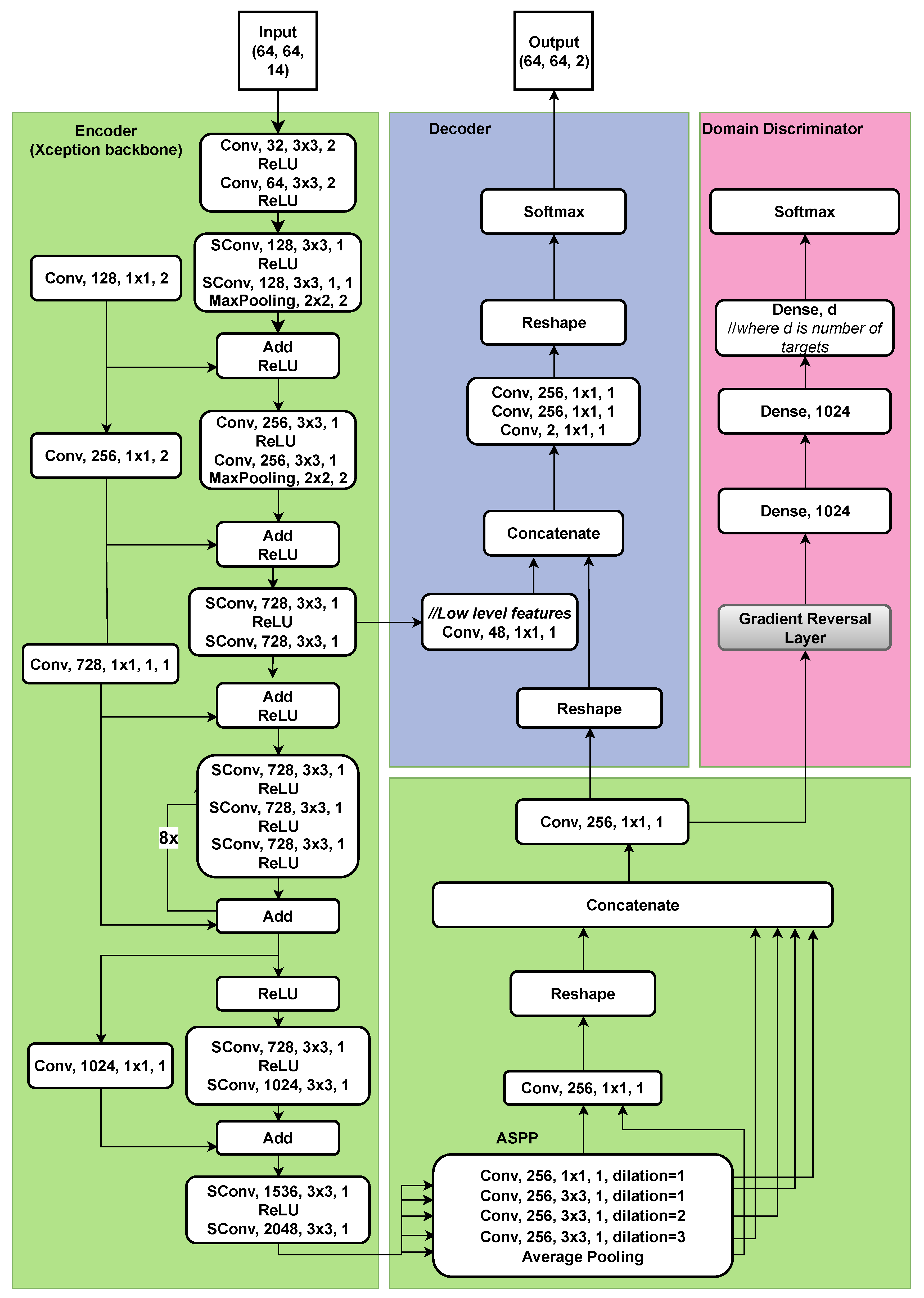

2.3. Deep Learning Model Architecture

The DMDA model developed in this study extends an adapted version of the Deeplabv3+ architecture introduced in [

17]. The encoder backbone relies heavily on Xception [

23], although some adjustments have been made to adapt the network to the problem and the input data. The dilation rates of the atrous convolutions in the ASPP have been modified to 1, 2 and 3, replacing the original rates of 6, 12, and 18 [

18].

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the deep learning architecture. The layer descriptions include the following information: Convolution type ("Conv" for regular convolution; "SConv" means depthwise separable convolution), number of filters, filter size, and stride. In addition, the ASPP component displays dilation rate values.

Figure 4.

Overview of Deeplabv3+ architecture. The full model has over 54M trainable parameters.

Figure 4.

Overview of Deeplabv3+ architecture. The full model has over 54M trainable parameters.

2.4. Uncertainty Estimation

In the second phase, following [

19], predictive entropy over an ensemble’s outcome is utilized as a metric for uncertainty estimation. The ensemble is composed of a set of instances of the architecture shown in

Figure 4. Each instance is trained with different random initializations of network weights, and different batch selections, resulting in

K different models. The uncertainty of the pixel-wise predictions is assessed by calculating the predictive entropy for the

K models, as in Equation (

7), in which

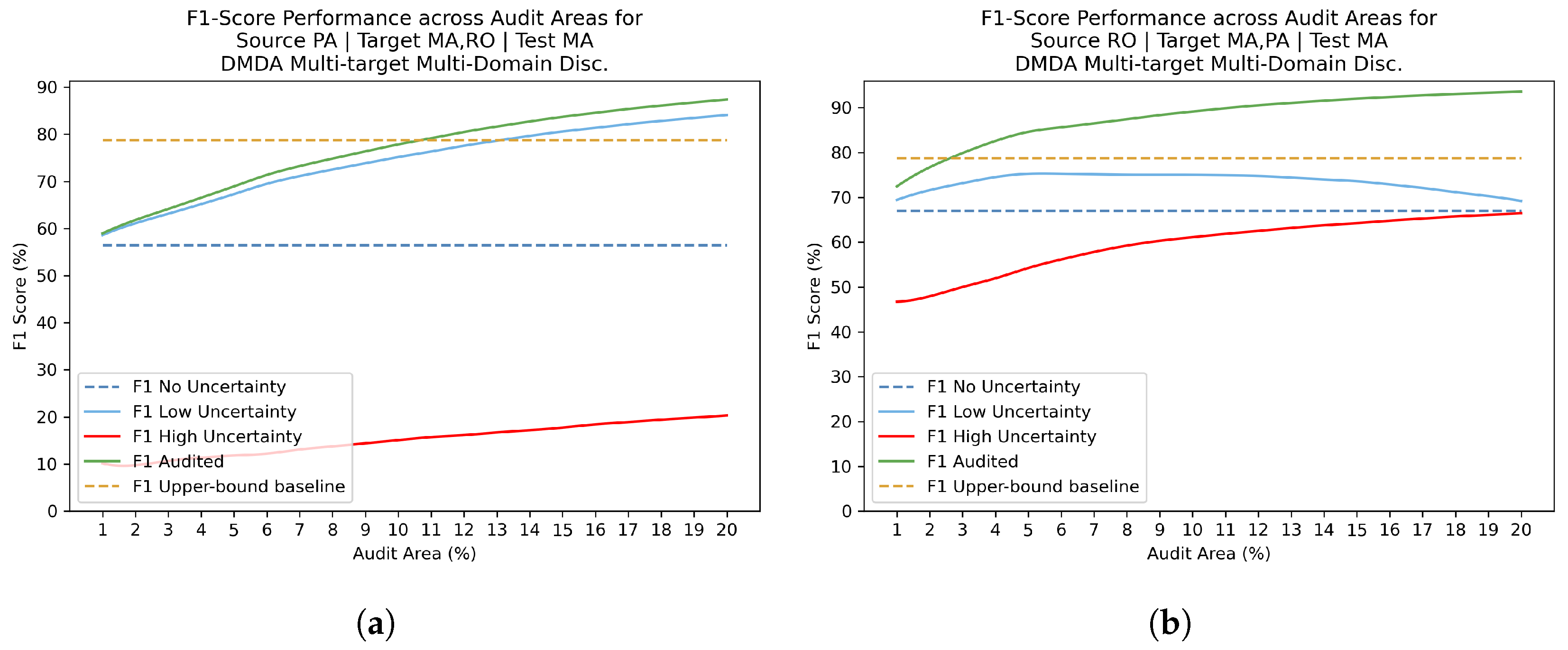

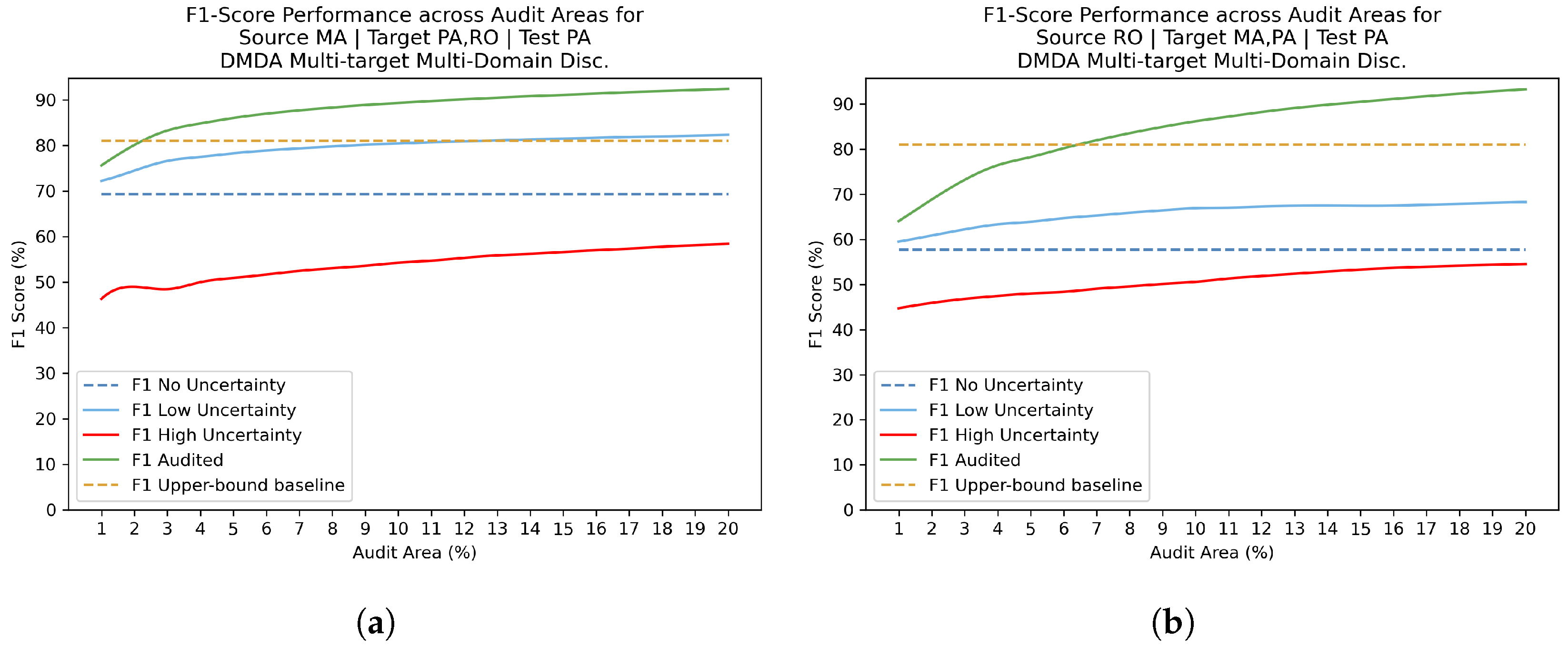

is a model’s output probability map. In the following experiments

K was arbitrarily chosen as five. The result is an uncertainty map with the same spatial dimensions as the prediction map.

To classify predictions as having high or low uncertainty, the uncertainty threshold Z is determined based on the audit area parameter , defined in terms of percentage of the total area. The uncertainty map values are sorted and the threshold Z is set at the percentile. The regions with high uncertainty are then selected for manual inspection. The goal is to find a threshold that optimizes the F1 score while minimizing manual review effort.

We adopted for samples with uncertainty below the threshold defined by the most uncertain pixels, which are subjected to audit. Contrarely, considers the pixels with the highest uncertainty values . represents the classification accuracy prior to auditing, and the classification performance after a human expert visually inspects and correctly annotates the high uncertainty regions. In this study, we simulate the inspection process by replacing the most uncertain pixels using their respective ground truth labels. It should be noted that this method of review of uncertainty areas can be applied to a model trained without domain adaptation as well, since it is independent of the training approach.

5. Discussion

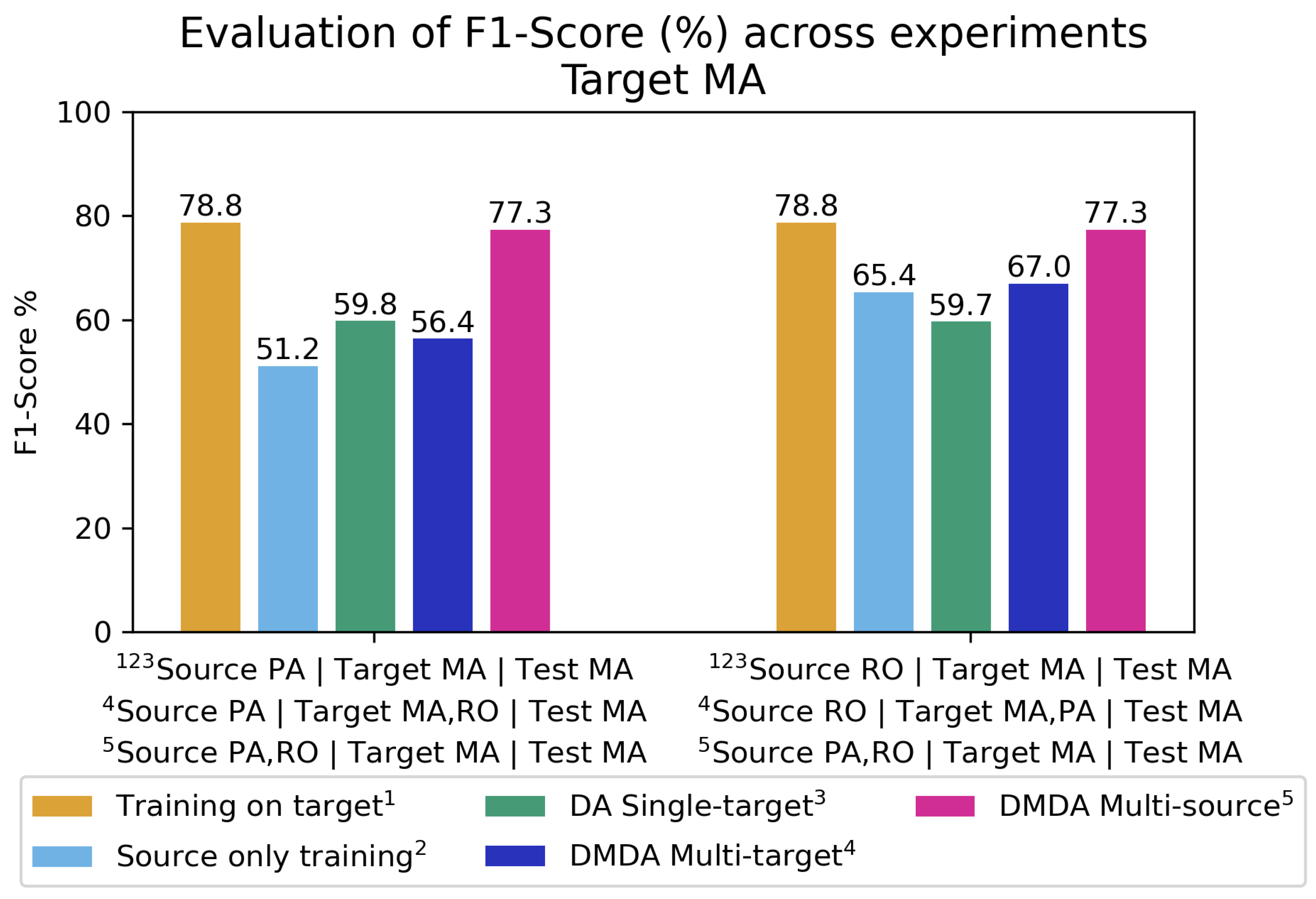

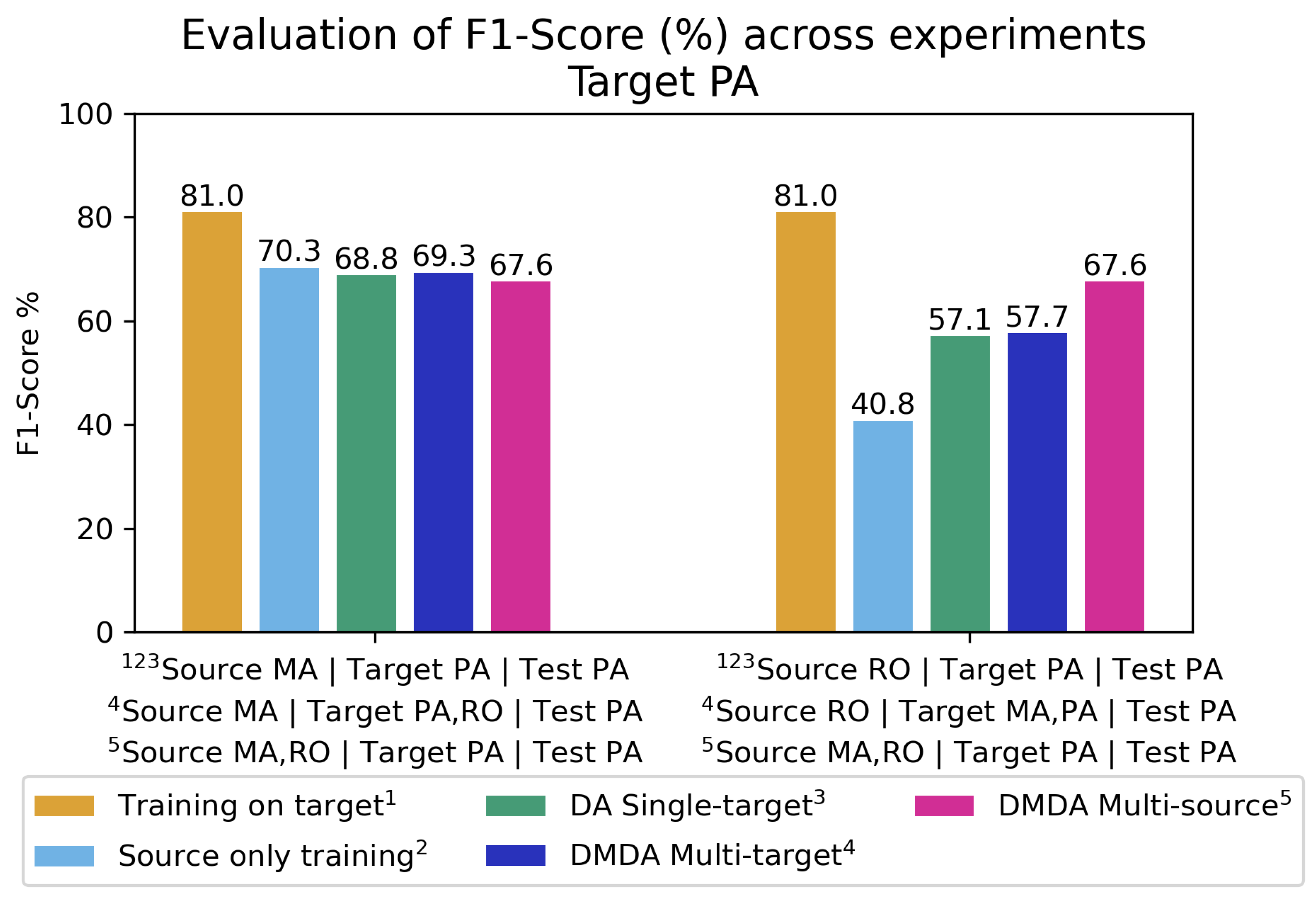

The results indicate that even with only one labeled source domain, prediction accuracy on a target domain can improve by incorporating an additional unlabeled target domain in the adaptation process. This inclusion helps the model learn features that are discriminative for the main task while remaining invariant to domain shifts. In the more favorable scenario of Multi-Source training, with two or more labeled source domains, the model significantly outperforms the lower-bound baseline and leverages the unlabeled data effectively, outperforming the ’Multi-Source only’ training experiment. This suggests that both multi-target and multi-source approaches are reliable methods to enhance model performance for deforestation detection. However, substantial gains with Multi-source and Multi-target domains heavily depend on the diversity of data attributes introduced by additional domains. Regarding the relationship among the three domains used in this study, the inclusion of Maranhão (MA) domain generally improves adaptation for the other domains. This may be explained by the higher complexity and variability of forested areas there. As MA has more dry periods, the visual characteristics of the forest changes without necessarily indicating deforestation. In addition, a model targeting MA is generally benefited from inclusion of PA or RO as third domain. Our hypothesis is that in areas with lower forest density, such as MA, the process of cleaning the area is easier and faster, resulting in more uniform deforestation footprints.

In contrast to other scenarios, the PA site presents a unique challenge due to its higher forest density. This density often results in incomplete deforestation processes, leaving behind debris that may persist for several years. As a consequence, these areas become visually harder to identify as deforested, complicating detection efforts. Both the PA and RO domains exhibit greater diversity in deforested areas, primarily due to the prevalence of clear-cutting with residual vegetation and regions undergoing progressive degradation. This diversity makes it more challenging to accurately classify these areas. When classifiers are trained on one domain (e.g., PA or RO) and applied to the other, they tend to produce a higher rate of false-positive predictions. In simpler terms, the PA and RO domains do not complement each other in terms of predictive accuracy, as the characteristics of deforestation in one domain do not translate well to the other.

Additionally, by using uncertainty estimation to refine predictions, the F1 score improved by 6 to 12 percentage points—a notable gain that, in some experiments, even exceeded the upper-bound baseline’s F1 score. The consistently low F1 scores in most metrics reveal a strong correlation between high uncertainty and prediction error.

6. Conclusions

The proposed approach learns invariant feature representations across multiple domains, whether source or target. This is achieved by strategically selecting samples from different domains and modifying the domain discriminator to predict the specific domain of each sample. Experimental results demonstrate that DMDA Multi-target outperformed Single-Target DA in four out of six cross-domain experiments. Furthermore, DMDA Multi-source surpassed both DMDA Multi-target and Single-Target DA in four out of six domain pair combinations, highlighting its effectiveness in improving prediction accuracy without requiring additional labeled data. While the success of multi-domain scenarios depends on the characteristics of the domains incorporated during training, these methods, given the increased diversity of training data—whether as source or target—tend to produce more balanced models in terms of accuracy. Although they may not always achieve the highest accuracy, they help mitigate negative transfer.

Additionally, targeted human review can further boost model accuracy with a relatively modest effort. In the context of remote sensing for deforestation detection, combining unsupervised multi-domain adaptation with uncertainty estimation to guide human intervention proves to be an effective strategy for significantly improving model classification performance. Though, it must be highlighted that human review is a technique that can be applied independently of the model, with or without adaptation, allowing even models trained on the target domain to benefit significantly from this approach.

Looking ahead, future work will explore additional biomes to determine which ones can benefit most from being adapted as a source or target domain in multi-domains scenarios. In the field of uncertainty estimation, we aim to leverage expert feedback for refining model training sessions and investigate how human review can influence model evolution.