Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

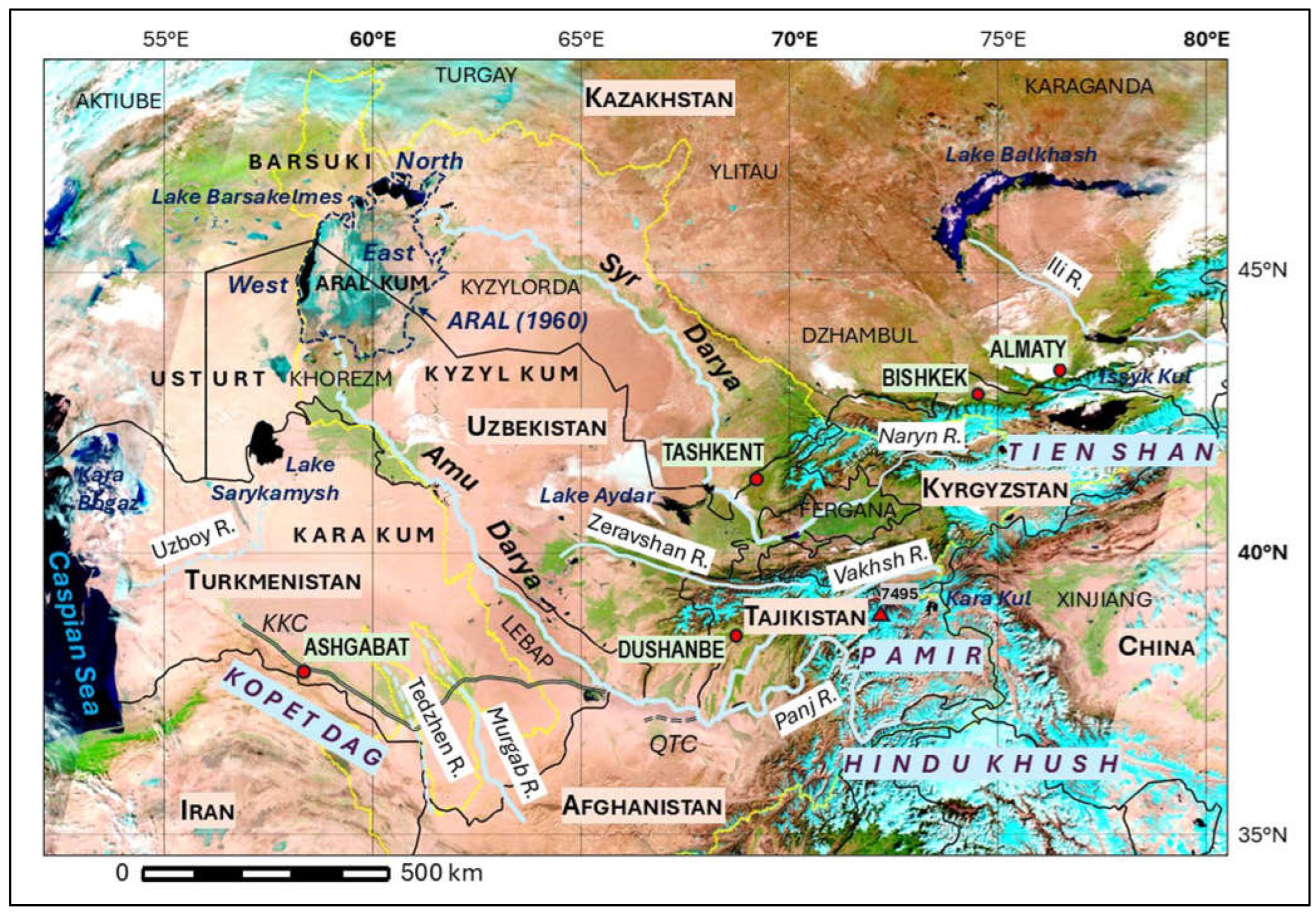

3. Study Area

4. Remote Sensing Based Results

4.1. Precipitation and Temperature

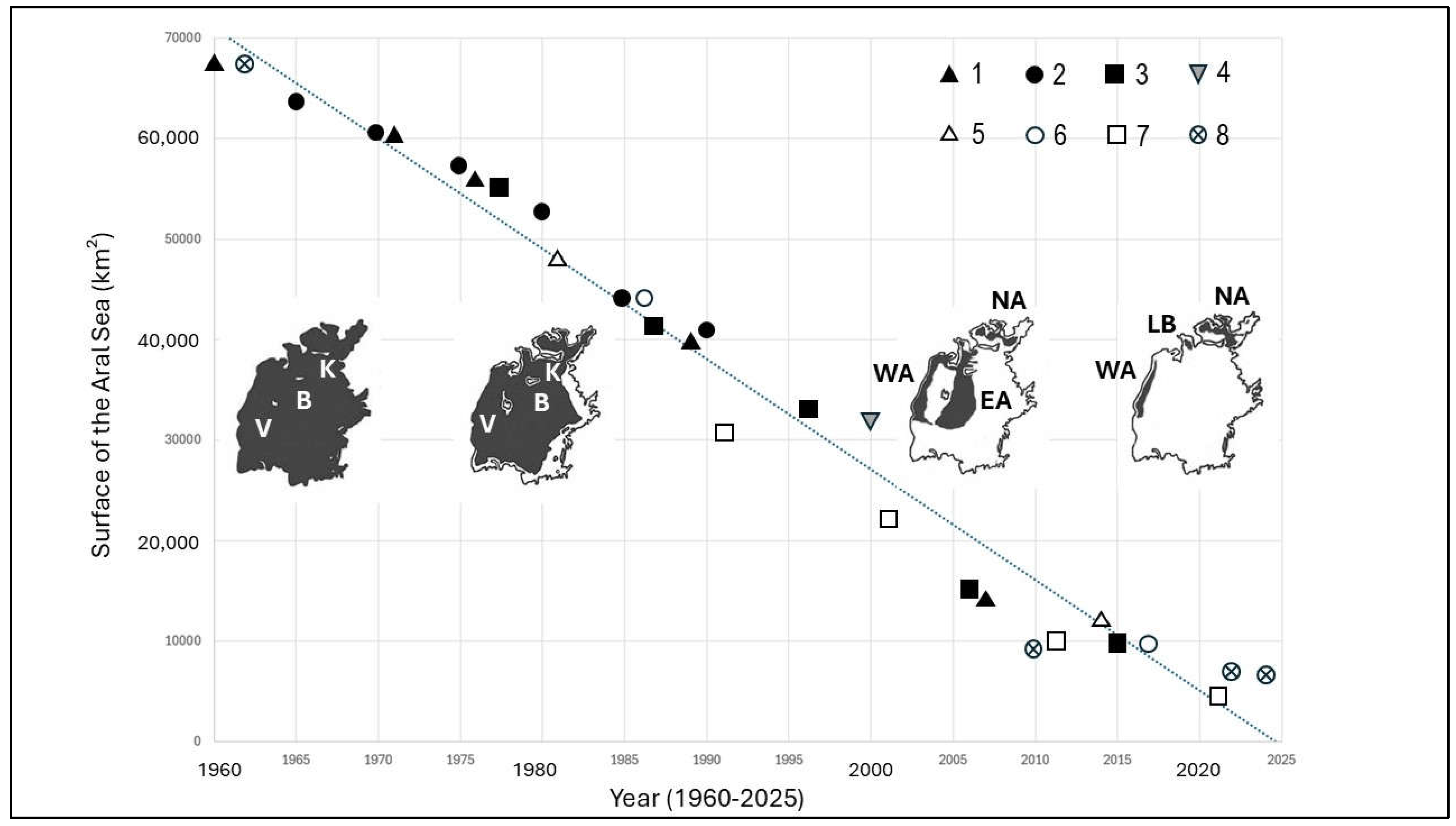

4.2. Water Surface

4.3. Water Surface Altimetry

4.4. Water Volume of the Water Bodies and Irrigation Systems

4.5. Snow and Ice

4.6. Geology

4.7. Salinisation (Minerals and Soils)

4.8. Dust

4.9. Landslides

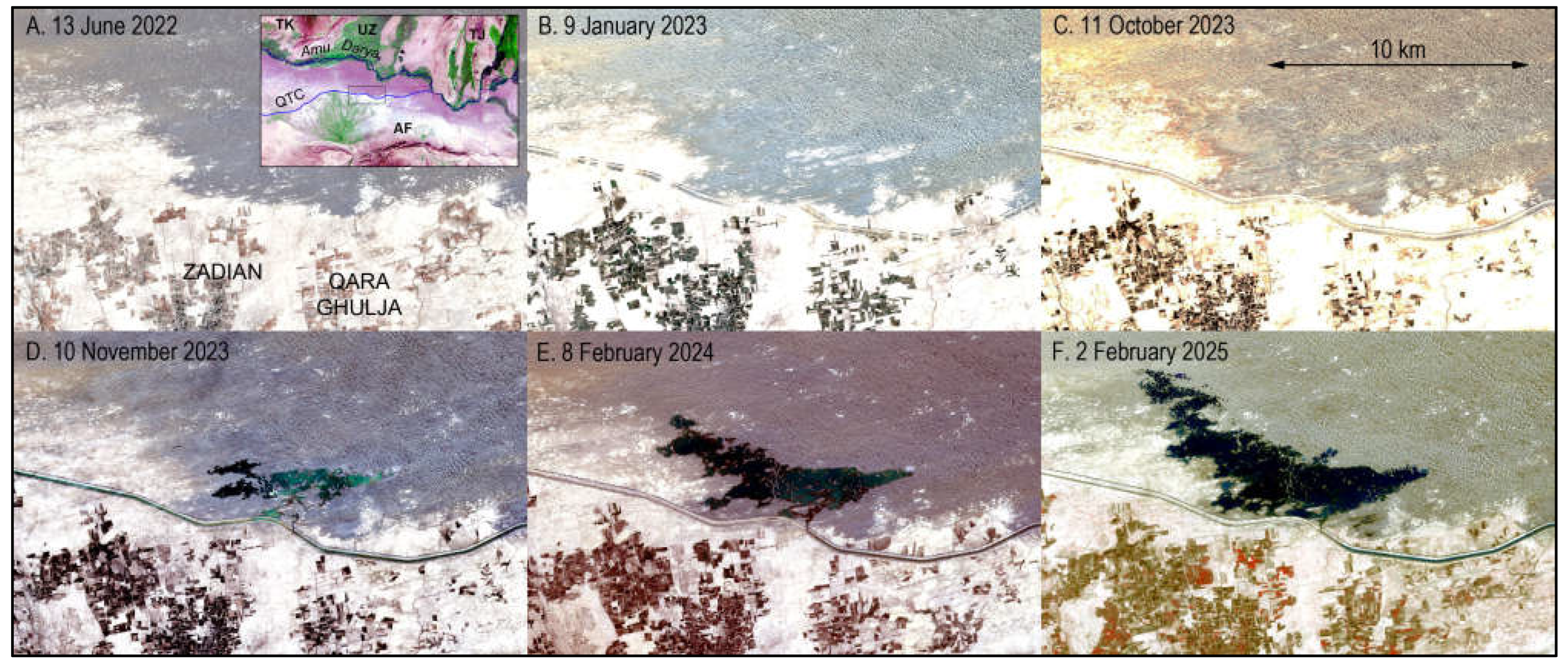

4.10. Flooding

4.11. Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs)

5. Discussion

5.1. Numerical Overview

5.2. Remote Sensing Data Used

5.3. The Question of the Origin of the Aral Sea Disaster

5.4. Paths of Research

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Micklin, P.P. Desiccation of the Aral Sea: A Water Management Disaster in the Soviet Union (FTA). Science 1988, 241, 1170–1176. [CrossRef]

- Létolle, R.; Mainguet, M. Aral. Springer-Verlag: Paris, France, 1993; pp. 1–357.

- Létolle, R. La Mer d’Aral. L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 1–313.

- Micklin, P.; Aladin, N.V.; Plotnikov, I.S. The Aral sea: The devastation and partial rehabilitation of a great lake. Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 1–445.

- Crétaux, J.F.; Kostianoy, A.; Bergé-Nguyen, M.; Kouraev, A. Present-day water balance of the Aral Sea seen from satellite. In Remote Sensing of the Asian Seas; Barale, V.; Gade, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 523–539.

- Xenarios, S.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; Qadir, M.; Janusz-Pawletta, B.; Abdullaev, I. The Aral Sea Basin. Water for sustainable development in Central Asia. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2020; pp. 1–222.

- Narbayep, M.; Pavlova, V. The Aral Sea, Central Asian Countries and Climate Change in the 21st Century. United Nations ESCAP, IDD, Working Paper Series, Part 1: Aral Sea, 2022, pp. 1–58.

- Nagabhatla, N.; Brahmbhatt, R. Geospatial assessment of water-migration scenarios in the context of sustainable development goals (SDGs) 6, 11, and 16. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1376. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cui, B.; Chen, Y.; Feng, T.; Li, Z.; Fang, G. Dynamic changes in water resources and comprehensive assessment of water resource utilization efficiency in the Aral Sea basin, Central Asia. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 353, 120198. [CrossRef]

- Reclus, E. L’Asie russe. Versant de l’Aral et de la Caspienne. In Nouvelle géographie universelle; Hachette: Paris, France, 1881; Volume 6, pp. 374–429.

- Encyclopédie Larousse, 1895. Aral.

- Crétaux, J.F.; Létolle, R.; Bergé-Nguyen, M. History of Aral sea level variability and current scientific debates. Global Planet. Change 2013, 110, 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Gaybullaev, B.; Chen, S.C.; Gaybullaev, D. Changes in water volume of the Aral Sea after 1960. Appl. Water Sci. 2012, 2, 285–291. [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, S.L. Irrigation and land degradation: implications for agriculture in Turkmenistan, central Asia. J. Arid Environ. 1997, 37, 165–179. [CrossRef]

- Saiko, T.A.; Zonn, I.S. Irrigation expansion and dynamics of desertification in the Circum-Aral region of Central Asia. Appl. Geogr. 2000, 20, 349–367. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Dech, S.W.; Hafeez, M.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Tischbein, B. Remote sensing and hydrological measurement based irrigation performance assessments in the upper Amu Darya Delta, Central Asia. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 2013, 61–62, 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Tischbein, B.; Manschadi, A.M.; Conrad, C.; Hornidge, A.; Bhaduri, A.; Hassan, M.U.; Lamers, J.P.A.; Awan, U.K.; Vlek, P.L.G. Adapting to water scarcity: constraints and opportunities for improving irrigation management in Khorezm, Uzbekistan. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2013, 13, 337–348. [CrossRef]

- Bekchanov, M.; Lamers, J.P.A. Economic costs of reduced irrigation water availability in Uzbekistan (Central Asia). Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 16, 2369–2387. [CrossRef]

- Bekchanov, M.; Ringler, C.; Bhaduri, A.; Jeuland, M. Optimizing irrigation efficiency improvements in the Aral Sea Basin. Water Resour. Econ. 2016, 13, 30–45. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Wei, J.; Yang, Z.L.; Lin, P. Irrigation-induced environmental changes around the Aral Sea: An integrated view from multiple satellite observations. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 900. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.; Usman, M.; Morper-Busch, L.; Schönbrodt-Stitt, S. Remote sensing-based assessments of land use, soil and vegetation status, crop production and water use in irrigation systems of the Aral Sea Basin. A review. Water Security 2020, 11, 100078. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Ran, Y.; Feng, M.; Nian, Y.; Tan, M.; Chen, X. Investigate the relationships between the Aral Sea shrinkage and the expansion of cropland and reservoir in its drainage basins between 2000 and 2020. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2021, 14, 661–677. [CrossRef]

- Propastin, P.; Kappas, M.; Muratova, N.R. A remote sensing based monitoring system for discrimination between climate and human-induced vegetation change in Central Asia. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2008, 19, 579–596. [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, T.; Siegfried, T. Climate change and international water conflict in Central Asia. J. Peace Res. 2012, 49, 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, T.; Bernauer, T.; Guiennet, R.; Sellars, S.; Robertson, A.W.; Mankin, J.; Bauer-Gottwein, P.; Yakovlev, A. Will climate change exacerbate water stress in Central Asia? Clim. Chang. 2012, 112, 881–899. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Glazirina, M.; Yuldashev, T.; Otarov, A.; Ibraeva, M.; Martynova, L.; Bekenov, M.; Kholov, B.; Ibragimov, N.; Kobilov, R.; et al. Impact of climate change on wheat productivity in Central Asia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 178, 78–99. [CrossRef]

- Fallah, B.; Didovets, I.; Rostami, M.; Hamidi, M. Climate change impacts on Central Asia: Trends, extremes and future projections. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 4, 3191–3213. [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Beck, H.; Coccia, G.; Serrat-Capdevila, A.; Verbist, K. Satellite remote sensing for water resources management: Potential for supporting sustainable development in data-poor regions. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 9724–9758. [CrossRef]

- Micklin, P. Using satellite remote sensing to study and monitor the Aral Sea and adjacent zone. NATO Security through Science Series C: Environmental Security, 2008, DOI:10.1007/978-1-4020-8960-2_3.

- Dukhovny, V.A. Comprehensive remote sensing and ground-based studies of the dried Aral Sea bed. Scientific-Information Center of the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia (SIC ICWC) 2008, pp. 1–172 p.

- Ginzburg, A.I.; Kostianoy, A.G.; Sheremet, N.A.; Kravtsova, V.I. Satellite monitoring of the Aral Sea Region. In The Aral Sea Environment. Kostianoy, A.G.; Kosarev, A.N. (eds), The handbook of environmental chemistry, 2010, 7, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 147–179. [CrossRef]

- Khasanov, S.; Juliev, M.; Uzbekov, U.; Aslanov, I.; Agzamova, I.; Normatova, N.; Islamov, S.; Goziev, G.; Khodjaeva, S.; Holov, N. Landslides in Central Asia: a review of papers published in 2000–2020 with a particular focus on the importance of GIS and remote sensing techniques. GeoScape 2021, 15, 134—145. [CrossRef]

- Howard, K.W.F.; Howard, K.K. The new ‘‘Silk Road Economic Belt’’ as a threat to the sustainable management of Central Asia’s transboundary water resources. Environ Earth Sci 2016, 75, 976.

- Dilinuer, T.; Yao, J.Q.; Chen, J.; Mao, W.Y.; Yang, L.M.; Yeernaer, H.; Chen, Y.H. Regional drying and wetting trends over Central Asia based on Köppen climate classification in 1961-2015. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2021, 12, 363–372. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Luo, G.; Cai, P.; Hamdi, R.; Termonia, P.; De Maeyer, P.; Kurban, A.; Li, J. Assessment of climate change in Central Asia from 1980 to 2100 using the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 123. [CrossRef]

- Berdimbetov, T. Spatio-temporal variations of climate variables and extreme indices over the Aral Sea Basin during 1960 – 2017. Trends Sci. 2023, 20, 5664.

- Berdimbetov, T.; Pushpawela, B.; Murzintcev, N.; Nietullaeva, S.; Gafforov, K.; Tureniyazova, A.; Madetov, D. Unraveling the intricate links between the dwindling Aral Sea and climate variability during 2002–2017. Climate 2024, 12, 105. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Bolch, T.; Mukherjee, K.; King, O.; Menounos, B.; Kapitsa, V.; Neckel, N.; Yang, W.; Yao, T. High Mountain Asian glacier response to climate revealed by multi-temporal satellite observations since the 1960s. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4133.

- Leuchs, K. Der Block von Ust-Urt. Geol. Rundsch. 1935, 26, 248–258. [CrossRef]

- Rubanov, I.V.; Bogdanova, N.M. Quantitative assessment of salt deflation on drying bottom of the Aral Sea. Probl. Ovs. Pustyn 1987, 3, 9–16.

- Létolle, R.; Mainguet, M. History of the Aral Sea (central Asia) since the most recent maximum glaciation. Bull. Geol. Soc. France 1997, 168, 387–398.

- Atlas of geological maps of Central Asia and adjacent areas. Eds. Tingdong, L.I.; Daukeev, S.Z.; Kim, B.C.; Tomurtogoo, O.; Petrov, O.V., Geological Publishing House, Beijing, China, 2008, maps at 1:2,500,000.

- Burr, G.S.; Kuzmin, Y.V.; Krivonogov, S.K.; Gusskov, S.A.; Cruz, R.J. A history of the modern Aral Sea (Central Asia) since the Late Pleistocene. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 2019, 206, 141–149. [CrossRef]

- Brunet, M.F.; McCann, T.; Sobel, E.R. Geological evolution of Central Asian Basins and the Western Tien Shan Range. Geol. Soc. Sp. 2017, 427, 1–17.

- Robert, A.M.M.; Letouzey, J.; Kavoosi, M.A.; Sherkati, S.; Müller, C.; Vergés, J.; Aghababaei, A. Structural evolution of the Kopeh Dagh fold-and-thrust belt (NE Iran) and interactions with the South Caspian Sea Basin and Amu Darya Basin. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2014, 57, 68–87.

- Hosseinyar, G.; Moussavi-Harami, R.; Fard, I.A.; Mahboubi, A.; Rad, R.N. Seismic geomorphology and stratigraphic trap analyses of the Lower Cretaceous siliciclastic reservoir in the Kopeh Dagh-Amu Darya Basin. Petroleum Sci. 2019, 16, 776–793. [CrossRef]

- Boomer, I.; Wünnemann, B.; Mackay, A.W.; Austin, P.; Sorrel, P.; Reinhardt, C.; Keyser, D.; Guichard, F.; Fontugne, M. Advances in understanding the late Holocene history of the Aral Sea region. Quaternary Int. 2009, 194, 79–90. [CrossRef]

- Sala, R. Quantitative evaluation of the impact on Aral Sea levels by anthropogenic water withdrawal and Syr Darya course diversion during the Medieval period (1.0–0.8 ka BP). In Socio-Environmental Dynamics along the Historical Silk Road, L. E. Yang et al. (eds.), Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2019, pp. 95-121.

- Boroffka, N.; Oberhänsli, H.; Sorrel, P.; Demory, F.; Reinhardt, C.; Wünnemann, B.; Alimov, K.; Baratov, S.; Rakhimov, K.; Saparov, N.; Shirinov, T.; Krivonogov, S.K.; Röhl, U. Archaeology and climate: Settlement and lake-level changes at the Aral Sea. Geoarchaeology 2006, 21, 721–734. [CrossRef]

- Mainguet, M.; Létolle, R.; Dumay, F. The regional Aeolian action system of the Aral Basin. C. R. Geosci. 2002, 334, 475–480.

- Pohl, E.; Knoche, M.; Gloaguen, R.; Andermann, C.; Krause, P. Sensitivity analysis and implications for surface processes from a hydrological modelling approach in the Gunt catchment, high Pamir Mountains. Earth Surf. Dynam., 2015, 3, 333–362. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhu, J.; Yan, W.; Zhao, C. Projections of desertification trends in Central Asia under global warming scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146777. [CrossRef]

- Nezlin, N.P.; Kostianoy, A.G.; Li, B.L. Inter-annual variability and interaction of remote-sensed vegetation index and atmospheric precipitation in the Aral Sea region. J. Arid Environ. 2005, 62, 677–700. [CrossRef]

- De Beurs, K.M.; Henebry, G.M.; Owsley, B.C.; Sokolik, I. Using multiple remote sensing perspectives to identify and attribute land surface dynamics in Central Asia 2001-2013. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 170, 48–60. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Abuduwaili, J.; Ma, L.; Samat, A. Remote sensing-based land surface change identification and prediction in the Aral Sea bed, Central Asia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, doi.org/10.1007/s13762-018-1801-0. [CrossRef]

- Deliry, S.I.; Avdan, Z.Y.; Do, N.T.; Avdan, U. Assessment of human-induced environmental disaster in the Aral Sea using Landsat satellite images. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 471. [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Shi, H.; Gao, C.; Zhan, J.; Ke, X. Water storage monitoring in the Aral Sea and its endorheic basin from multisatellite data and a hydrological model. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2408. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lee, Y.K.; Grassotti, C.; Liang, X.M.; Kidder, S.Q.; Kusselson, S. The challenge of surface type changes over the Aral Sea for satellite remote sensing of precipitation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. 2022, 15, 8650–8655. [CrossRef]

- Kravtsova, V.I. Analysis of changes in the Aral Sea coastal zone in 1975–1999. Water Resour. 2001, 28, 596–603. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ke, L.; Ding, X.; Wang, R.; Zeng, F. Monitoring spatial–temporal variations in river width in the Aral Sea Basin with Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. 2024 16, 822. [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.; Dietz, A.J.; Gessner, U.; Galayeva, A.; Myrzakhmetov, A.; Kuenzer, C. Evaluation of seasonal water body extents in Central Asia over the past 27 years derived from medium-resolution remote sensing data. Int. J. App. Earth Obs. 2014, 26, 335–349. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, M.; Guo, W. Long-term hydrological changes of the Aral Sea observed by satellite. J. Geophys. Res. – Oceans 2014, 119, 3313–3326. [CrossRef]

- Crétaux, J.F.; Birkett, C. Lake studies from satellite radar altimetry. C. R. Geosci. 2006, 338, 1098–1112. [CrossRef]

- Kouraev, A.V.; Kostianoy, A.G.; Lebedev, S.A. Ice cover and sea level of the Aral Sea from satellite altimetry and radiometry (1992–2006). J. Mar. Syst. 2009, 76, 272–286. [CrossRef]

- Zmijewski, K.; Becker, R. Estimating the effects of anthropogenic modification on water balance in the Aral Sea watershed using GRACE: 2003–12. Earth Interact. 2013, 18, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Seitz, F.; Schwatke, C. Inter-annual water storage changes in the Aral Sea from multi-mission satellite altimetry, optical remote sensing, and GRACE. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 123, 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Crétaux, J.F.; Létolle, R.; Calmant, S. Investigations on Aral Sea regressions from mirabilite deposits and remote sensing. Aquat. Geochem. 2009, 15, 277–291. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, X.; Mao, Z. The dynamic changes of Lake Issyk-Kul from 1958 to 2020 based on multi-source satellite data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1575. [CrossRef]

- Crétaux, J.F.; Bergé-Nguyen, M.; Calmant, S.; Jamangulova, N.; Satylkanov, R.; Lyard, F.; Perosanz, F.; Verron, J.; Samine Montazem, A.; Le Guilcher, G.; Leroux, D.; Barrie, J.; Maisongrande, P.; Bonnefond, P. Absolute calibration or validation of the altimeters on the Sentinel-3A and the Jason-3 over Lake Issykkul (Kyrgyzstan). Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1679. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Chen, A.; He, J.; Hua, T.; Qie, Y. Changes in area and water volume of the Aral Sea in the arid Central Asia over the period of 1960–2018 and their causes. Catena 2020, 191, 104566. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Behrangi, A.; Fisher, J.B.; Reager, J.T. On the desiccation of the South Aral Sea observed from spaceborne missions. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 793. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, J.; Xing, W.; Akmalov, S.; Peng, J.; Pan, X.; Guo, C.; Duan, Y. Water balance analysis based on a quantitative evapotranspiration inversion in the Nukus irrigation area, Lower Amu River Basin. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2317. [CrossRef]

- Oberhänsli, H.; Weise, S.M.; Stanichny, S. Oxygen and hydrogen isotopic water characteristics of the Aral Sea, Central Asia. J. Marine Syst. 2009, 76, 310–321. [CrossRef]

- Thevs, N.; Ovezmuradov, K.; Zanjani, L.V.; Zerbe, S. Water consumption of agriculture and natural ecosystems at the Amu Darya in Lebap Province, Turkmenistan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 731–741.

- Shi, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, S.; Su, Y; Shi, Y. The effect of farmland on the surface water of the Aral Sea region using multi-source satellite data. PeerJ 2022, 10:e12920. [CrossRef]

- Gardelle, J.; Berthier,E.; Arnaud, Y.; Kääb, A. Region-wide glacier mass balances over the Pamir-Karakoram-Himalaya during 1999–2011. The Cryosphere 2013, 7, 1263–1286. [CrossRef]

- Rittger, K.; Bormann, K.J.; Bair, E.H.; Dozier, J.; Painter, T.H. Evaluation of VIIRS and MODIS Snow Cover Fraction in High-Mountain Asia Using Landsat 8 OLI. Front. Remote Sens. 2021, 2, 647154. [CrossRef]

- Kouraev, A.V.; Papa, F.; Mognard, N.M.; Buharizin, P.I.; Cazenave, A.; Crétaux, J.-F.; Dozortseva, J.; Remy, F. Synergy of active and passive satellite microwave data for the study of first-year sea ice in the Caspian and Aral Seas. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 2170–2176. [CrossRef]

- Vydra, C.; Dietz, A.J.; Roessler, S.; Conrad, C. The influence of snow cover variability on the runoff in Syr Darya headwater catchments between 2000 and 2022 based on the analysis of remote sensing time series. Water 2024, 16, 1902. [CrossRef]

- Mergili, M.; Müller, J.P.; Schneider, J.F. Spatio-temporal development of high-mountain lakes in the headwaters of the Amu Darya River (Central Asia). Global Planet. Change 2013, 107, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Sadov, A.V.; Krapilskaya, N.M.; Revzon, A.L. Aerospace methods of examining aeration zone in sandy deserts. Int. Geol. Rev. 1980, 23, 297–301. [CrossRef]

- Revzon, A.L.; Burleshin, M.I.; Krapilskaya, N.M.; Sadov, A.V.; Svitneva, T.V.; Semina, N.S. Desert geology studied through air and space methods. Probl. Ovs. Pustyn 1982, 1, 20–28.

- Vitkovskaya, T.P.; Mansimov, M.; Shekhter, L.G. Dynamics of the Sarykamysh Lake development based on space photography. Probl. Ovs. Pustyn 1985, 6, 38–43.

- Borodin, L.F.; Bortnik, V.N.; Krapivin, V.F.; Kuznetsov; N.T., Kulikov; Y.N.; Minaeva, E.N. Some general questions of changes, appraisal elaboration of functioning and the remote sensing monitoring models for aqua- and geosystems of the Aral Sea Basin. Probl. Osv. Pustyn 1987, 1, 71–80.

- Kes, A.S. History of the Sarykamysh Lake in the light of the new data obtained by the distant technique. Probl. Ovs. Pustyn 1987, 1, 36–41.

- Sadov, A.V.; Krasnikov, V.V. Remote sensing in detection of local subaqueous discharge of ground water into the Aral Sea. Probl. Ovs. Pustyn 1987, 1, 28–36.

- Mackenzie, D.; Walker, R.; Abdrakhmatov, K.; Campbell, G.; Carr, A.; Gruetzner, C.; Mukambayev, A.; Rizza, M. A creeping intracontinental thrust fault: past and present slip-rates on the Northern edge of the Tien Shan, Kazakhstan. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 215, 1148–1170. [CrossRef]

- Grützner, C.; Walker, R.T.; Abdrakhmatov, K.E.; Mukambaev, A.; Elliott, A.J.; Elliott, J.R. Active tectonics around Almaty and along the Zailisky Alatau rangefront. Tectonics 2017, 36, 2192–2226. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Han, L.; Xu, X. Gold-copper deposits in Wushitala, Southern Tianshan, Northwest China: Application of ASTER data for mineral Exploration. Geol. J. 2018, 53, 362–371. [CrossRef]

- Zheentaev, E. Application of remote sensing technologies for the environmental impact analysis in Kumtor gold mining company. Int. J. Geoinf., 2015, 12, 31–39.

- Jiang, Y.; Lin, W.; Wu, M.; Liu, K.; Yu, X.; Gao, J. Remote sensing monitoring of ecological-economic impacts in the Belt and Road Initiatives mining project: A case study in Sino Iron and Taldybulak Levoberezhny. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3308. [CrossRef]

- He B.; Xue, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhao, L.; Jin, C.; Wang, P.; Li, P.; Liu, W.; Yin, W.; Yuan, T. Monitoring oil and gas field CH4 leaks by Sentinel-5P and Sentinel-2. Fuel 2025, 383, 133889. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, E.; Gorroño, J.; Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Varon, D.J.; Guanter, L. Mapping methane plumes at very high spatial resolution with the WorldView-3 satellite. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 1657–1674. [CrossRef]

- Sichugova, L.; Fazilova, D. The lineaments as one of the precursors of earthquakes: A case study of Tashkent geodynamical polygon in Uzbekistan. Geodesy and Geodyn. 2021, 12, 399–404. [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Jiang, M.; Singh, R.P. Detection of seismic microwave radiation anomalies in snow-covered mountainous terrain: Insights from two recent earthquakes in the Pamir–Tien Shan Region. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. 2024, 17, 18156–18166. [CrossRef]

- Gorny, V.I.; Salman, A.G.; Tronin, A.A.; Shilin, B.V. Terrestrial outgoing infrared radiation as an indicator of seismic activity. Proc. Acad. Sci. USSR 1988, 301, 67-69.

- Oberhänsli, H.; Novotná, K.; Píšková, A.; Chabrillat, S.; Nourgaliev, D.K.; Kurbaniyazov, A.K.; Grygar, T.M. Variability in precipitation, temperature and river runoff inW Central Asia during the past ~2000 yrs. Global Planet. Change 2011, 76, 95–104.

- Schettler, G.; Oberhänsli, H.; Stulina, G.; Mavlonov, A.A.; Naumann, R. Hydrochemical water evolution in the Aral Sea Basin. Part I: Unconfined groundwater of the Amu Darya Delta – Interactions with surface waters. J. Hydrol. 2013a, 495, 267–284.

- Schettler, G.; Oberhänsli, H.; Stulina, G.; Djumanov, J.H. Hydrochemical water evolution in the Aral Sea Basin. Part II: Confined groundwater of the Amu Darya Delta – Evolution from the headwaters to the delta and SiO 2 geothermometry. J. Hydrol. 2013b, 495, 285–303.

- Bishimbayev, V.K.; Issayeva, A.U.; Nowak, I.; Serzhanov, G.; Tleukeyeva, A.Y. Prospects for rational use of mineral resources of the Dzhaksy-Klych deposit, the Aral region. News Nat. Acad. Sci. Rep. Kazakhstan, Series Geol. Techn. Sci. 2020, 443, 196–203. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, X.; Bao, A.; Lei, J.; Xu,W.; Luo, G.; Guan, Q. Desertification extraction based on a microwave backscattering contribution decomposition model at the dry bottom of the Aral Sea. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4850. [CrossRef]

- Akramkhanov, A.; Martius, C.; Park, S.J.; Hendrickx, J.M.H. Environmental factors of spatial distribution of soil salinity on flat irrigated terrain. Geoderma 2011, 163, 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Wang, X.; Sun, L. Monitoring and mapping of soil salinity on the exposed seabed of the Aral Sea, Central Asia. Water 2022, 14, 1438. [CrossRef]

- Grigoryev, A.A.; Lipatov, V.B. Distribution of dust pollution in the Circum-Aral region by space monitoring. Proc. Acad. Sci. USSR, geographical series 1983, 4, 73–77.

- Grigoryev, A.A.; Jogova, M.L. Strong dust blowouts in Aral region in 1985–1990. Proc. Russ. Acad. Sci. 1992, 324, 672–675.

- Prospero, J.M.; Ginoux, P.; Torres, O.; Nicholson, S.E.; Gill, T.E. Environmental characterization of global sources of atmospheric soil dust identified with the Nimbus 7 Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) absorbing aerosol product. Rev. Geophys. 2002, 40, 1. [CrossRef]

- Löw, F.; Navratil, P.; Kotte, K.; Schöler, H.F.; Bubenzer, O. Remote-sensing-based analysis of landscape change in the desiccated seabed of the Aral Sea — A potential tool for assessing the hazard degree of dust and salt storms. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 8303–8319. [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Kavianpour, M.R.; Shao, Y. Numerical simulation of dust events in the Middle East. Aeolian Res. 2014, 13, 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. R.; Heinold, B.; Schepanski, K. Impacts of the desiccation of the Aral Sea on the Central Asian dust life-cycle. J. Geoph. Res. Atm. 2022, 127, e2022JD036618. [CrossRef]

- Indoitu, R.; Kozhoridze, G.; Batyrbaeva, M.; Vitkovskaya, I.; Orlovsky, N.; Blumberg, D.; Orlovsky, L. Dust emission and environmental changes in the dried bottom of the Aral Sea. Aeolian Res. 2020, 17, 101–115. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Samat, A.; Ge, Y.; Ma, L.; Tuheti, A.; Zou, S.; Abuduwaili, J. Quantitative soil wind erosion potential mapping for central Asia using the Google Earth engine platform. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3430. [CrossRef]

- Ubaidulloev, A.; Kaiheng, H.; Rustamov, M.; Kurbanova, M. Landslide inventory along a National Highway Corridor in the Hissar-Allay Mountains, Central Tajikistan. GeoHazards 2021, 2, 212–227. [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C.; Caiserman, A.; Jarihani, B.; Khojazoda, Z.; Kiesel, J.; Kulikov, M.; Qadamov, A. Sediment sources, erosion processes, and interactions with climate dynamics in the Vakhsh River Basin, Tajikistan. Water 2024, 16, 122. [CrossRef]

- Nardini, O.; Confuorto, P.; Intrieri, E.; Montalti, R.; Montanaro, T.; Garcia Robles, J.; Poggi, F.; Raspini, F. Integration of satellite SAR and optical acquisitions for the characterization of the Lake Sarez landslides in Tajikistan. Landslides 2024, 21, 1385–1401. [CrossRef]

- Behling, R.; Roessner, S.; Kaufmann, H.; Kleinschmit, B. Automated spatiotemporal landslide mapping over large areas using RapidEye time series data. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 8026-8055. [CrossRef]

- Roessner, S.; Wetzel, H.U.; Kaufmann, H.; Sarnagoev, A. Potential of satellite remote sensing and GIS for landslide hazard assessment in Southern Kyrgyzstan (Central Asia). Nat. Hazards 2005, 35, 395–416. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, U.; Pittore, M.; Behling, R.; Roessner, S.; Andreani, L.; Korup, O. How robust are landslide susceptibility estimates? Landslides 2021, 18, 681–695.

- Teshebaeva, K.; Roessner, S.; Echtler, H.; Motagh, M.; Wetzel, H.U.; Molodbekov, B. ALOS/PALSAR InSAR time-series analysis for detecting very slow-moving landslides in Southern Kyrgyzstan. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 8973–8994. [CrossRef]

- Piroton, V.; Schlögel, R.; Barbier, C.; Havenith, H.B. Monitoring the recent activity of landslides in the Mailuu-Suu Valley (Kyrgyzstan) using radar and optical remote sensing techniques. Geosci. 2020, 10, 164. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Motagh, M.; Xia, Z.; Plank, S.; Li, Z.; Orynbaikyzy, A.; Zhou, C.; Roessner, S. A framework for automated landslide dating utilizing SAR-derived parameters time-series, an Enhanced Transformer Model, and Dynamic Thresholding. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2024, 129, 103795. [CrossRef]

- Juliev, M.; Mergili, M.; Mondal, I.; Nurtaev, B.; Pulatov, A.; Hübl, J. Comparative analysis of statistical methods for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Bostanlik District, Uzbekistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 801–814. [CrossRef]

- Aslan, G.; de Michele, M.; Raucoules, D.; Renard, F.; Dehls, J.; Penna, I.; Hermann, R.; Cakir, Z. Dynamics of a giant slow landslide complex along the coast of the Aral Sea, Central Asia. Turk. J. Earth. Sci. 2023, 32, 819–832. [CrossRef]

- Tavus, B.; Kocaman, S.; Gokceoglu, C. Flood damage assessment with Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data after Sardoba dam break with GLCM features and Random Forest method. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151585. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Stanturf, J.A.; Williams, M.D.; Botmann, E.; Madsen, P. Quantification of Mountainous Hydrological Processes in the Aktash River Watershed of Uzbekistan, Central Asia, over the Past Two Decades. Hydrology 2023, 10, 161. [CrossRef]

- Kapitsa, V.; Shahgedanova, M.; Kasatkin, N.; Severskiy I.; Kasenov, M.; Yegorov, A.; Tatkova, M. Bathymetries of proglacial lakes: a new data set from the northern Tien Shan, Kazakhstan. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1192719. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, M.A.; Sabitov, T.Y.; Tomashevskaya, I.G.; Glazirin, G.E.; Chernomorets, S.S.; Savernyuk, E.A.; Tutubalina, O.V.; Petrakov, D.A.; Sokolov, L.S.; Dokukin, M.D.; Mountrakis, G.; Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Stoffel, M. Glacial lake inventory and lake outburst potential in Uzbekistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 228–242. [CrossRef]

- Mergili, M.; Schneider, J.F. Regional-scale analysis of lake outburst hazards in the southwestern Pamir, Tajikistan, based on remote sensing and GIS. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 1447–1462. [CrossRef]

- Petrakov, D.A.; Chernomorets, S.S.; Viskhadzhieva, K.S.; Dokukin, M.D.; Savernyuk, E.A.; Petrov, M.A.; Erokhin, S.A.; Tutubalina, O.V.; Glazyrin, G.E.; Shpuntova, A.M.; Stoffel, M. Putting the poorly documented 1998 GLOF disaster in Shakhimardan River valley (Alay Range, Kyrgyzstan/Uzbekistan) into perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138287. [CrossRef]

- Erokhin, S.A.; Zaginaev, V.V.; MeleshkoI, A.A.; Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Petrakov, D.A.; Chernomorets, S.S.; Viskhadzhieva, K.S.; Tutubalina. O.V.; Stoffel, M. Debris flows triggered from non-stationary glacier lake outbursts: the case of the Teztor Lake complex (Northern Tian Shan, Kyrgyzstan). Landslides 2018 15, 83–98. [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, D.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S.; Xie, Z.; Pieczonka, T.; Xu, J.; Moldobekov, B. Quick release of internal water storage in a glacier leads to underestimation of the hazard potential of glacial lake outburst floods from Lake Merzbacher in central Tian Shan Mountains. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 9786–9795. [CrossRef]

- Bolch, T.; Peters, J.; Yegorov, A.; Pradhan, B.; Buchroithner, M.; Blagoveshchensky, V. Identification of potentially dangerous glacial lakes in the northern Tien Shan. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1691–1714. [CrossRef]

- Daiyrov, M.; Narama, C.; Kääb, A.; Tadono, T. Formation and outburst of the Toguz-Bulak glacial lake in the Northern Teskey Range, Tien Shan, Kyrgyzstan. Geosci. 2020, 10, 468. [CrossRef]

- Daiyrov, M.; Kattel, D.B.; Narama, C.; Wang, W. Evaluating the variability of glacial lakes in the Kyrgyz and Teskey ranges, Tien Shan. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 850146. [CrossRef]

- Zaginaev, V.; Petrakov, D.; Erokhin, S.; Meleshko, A.; Stoffel, M.; Ballesteros-Cánovas, J.A. Geomorphic control on regional glacier lake outburst flood and debris flow activity over northern Tien Shan. Global Planet. Change 2019, 176, 50–59. [CrossRef]

- Meyrat, G.; Munch, J.; Cicoira, A.; McArdell, B.; Müller, C.R.; Frey, H.; Bartelt, P. Simulating glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs) with a two-phase/layer debris flow model considering fluid-solid flow transitions. Landslides 2024, 21, 479–497. [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Song, C.; Liu, K.; Ke, L.; Ma, R. An effective low-cost remote sensing approach to reconstruct the long-term and dense time series of area and storage variations for large lakes. Sensors 2019, 19, 4247. [CrossRef]

- O'Grady, D.; Leblanc, M.; Bass, A. The use of radar satellite data from multiple incidence angles improves surface water mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 652–664. [CrossRef]

- Gladkova, I.; Grossberg, M. D.; Shahriar, F.; Bonev, G.; Romanov, P. Quantitative restoration for MODIS band 6 on Aqua. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 2409–2416. [CrossRef]

- Hoelzle, M.; Barandun, M.; Bolch, T.; Fiddes, J.; Gafurov, A.; Muccione, V.; Saks, T.; Shahgedanova, M. The status and role of the alpine cryosphere in Central Asia. In The Aral Sea Basin, Water for Sustainable Development in Central Asia; Xenarios, S.; Schmidt-Vogt, D.; Qadir, M.; Janusz-Pawletta, B.; Abdullaev, I., Eds.; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2020; pp. 100–121.

- Xu, N.; Zhang, J.; Daccache, A.; Liu, C.; Ahmadi, A.; Zhou, T.; Gou, P. Assessing size shifts amidst a warming climate in lakes recharged by the Asian Water Tower through satellite imagery. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 68770. [CrossRef]

- Orlov, V.I.; Sokolova, N.V. To problem of preservation of Aral Sea. Gidrotekhnicheskoe Stroitel'stvo 1991, 11, 34–37.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).