Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

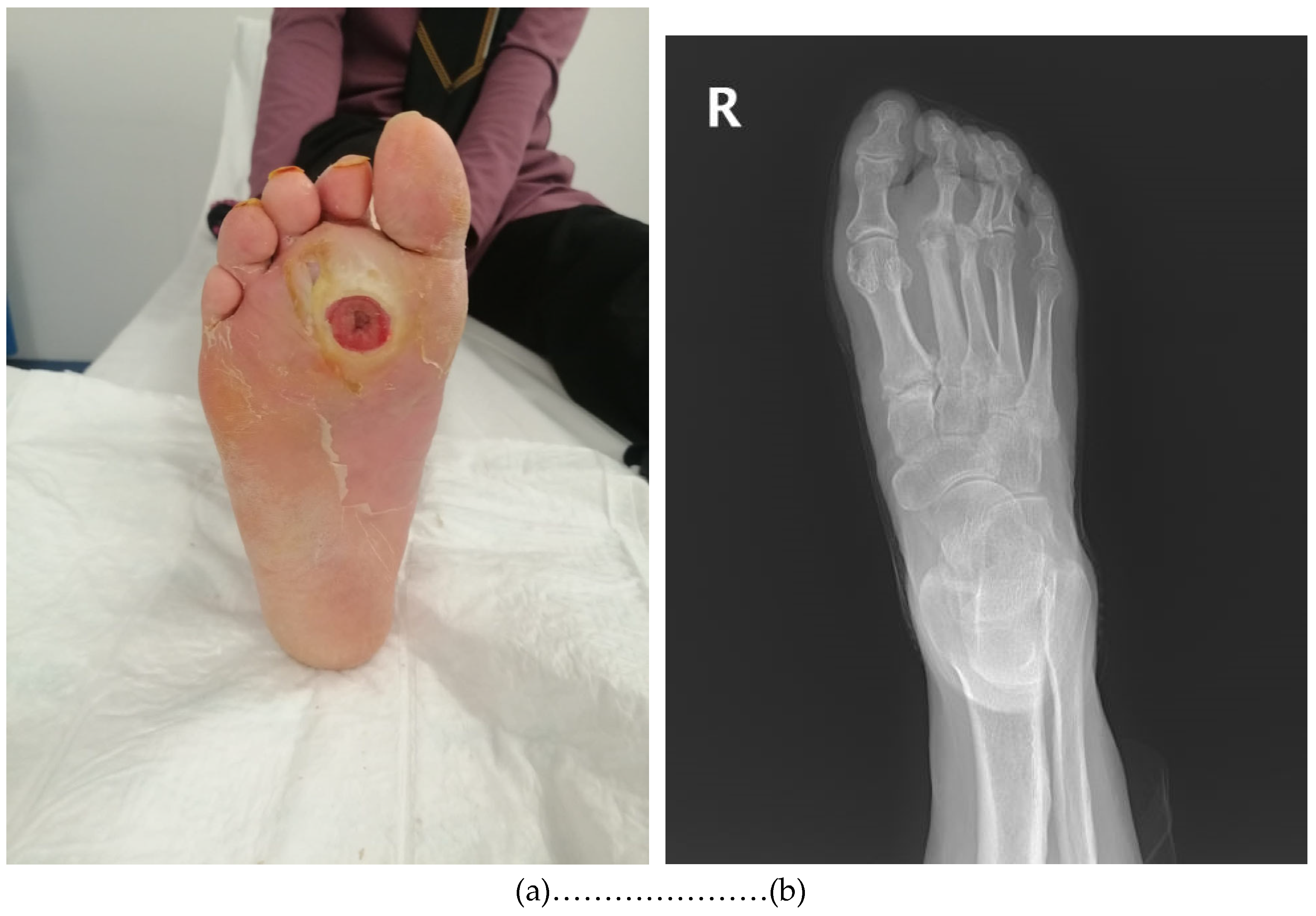

Background: Diabetic foot osteomyelitis (DFO) is a serious complication of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) that contributes to high morbidity and an increased risk of lower extremity amputation. While bone biopsy cultures are considered the gold standard for identifying causative pathogens, their invasive nature limits widespread clinical use. This study evaluates the microbiological concordance between deep tissue and bone cultures in diagnosing DFO. Methods: A retrospective analysis was con-ducted on 107 patients with DFO who underwent simultaneous deep tissue and bone biopsy cultures. Patient demographics, ulcer classification, and microbiological culture results were recorded. The agreement between deep tissue and bone cultures was as-sessed to determine the diagnostic utility of deep tissue sampling. Results: The overall concordance between deep tissue and bone cultures was 51.8%. Staphylococcus aureus was the most frequently isolated pathogen in both culture types and had the highest agreement rate (44.4%). Concordance rates were lower for Gram-negative bacteria (31.9%) and other Gram-positive microorganisms (24.2%). In 21.2% of cases, patho-gens were isolated only from deep tissue cultures, while 16.5% had positive bone cul-tures but negative deep tissue cultures. Conclusions: Deep tissue cultures demonstrate moderate agreement with bone biopsy cultures when diagnosing DFO, particularly for Staphylococcus aureus. While bone biopsy remains the gold standard diagnosis tool, deep tissue cultures may provide clinically useful information when bone sampling is not feasible. Further studies are needed to improve non-invasive diagnostic methods for DFO.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Population

- Diagnosis of diabetic foot infection;

- Positive probe-to-bone (PTB) test (performed using a sterile blunt metal probe; considered positive when bone was palpable through the ulcer);

- Radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis (presence of suggestive findings in initial or follow-up X-rays);

- Absence of clinical signs of Charcot’s neuroarthropathy;

- Concurrent collection of deep tissue and bone culture samples in the operating room during hospitalization;

- Not receiving antibiotic therapy at the time of hospital admission

2.3. Specimen Collection

2.4. Microbiological Analysis

2.5.Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. Lancet 2024, 404, 2077–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, R.; Chan, C.S.; Nather, A. Osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Diabet. Foot Ankle 2014, 5, 24445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville, E.; Albalawi, Z.; van Asten, S.A.; Abbas, Z.G.; Allison, G.; Aragon-Sanchez, J.; Embil, J.M.; Lavery, L.A.; Alhasan, M.; Oz, O.; et al. Diagnosis of infection in the foot of patients with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutluoglu, M.; Sivrioglu, A.K.; Eroglu, M.; Uzun, G.; Turhan, V.; Ay, H.; Lipsky, B.A. The implications of the presence of osteomyelitis on outcomes of infected diabetic foot wounds. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 45, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansert, E.A.; Tarricone, A.N.; Coye, T.L.; Crisologo, P.A.; Truong, D.; Suludere, M.A.; Lavery, L.A. Update of biomarkers to diagnose diabetic foot osteomyelitis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Wound Repair. Regen. 2024, 32, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Sánchez, J.; Lipsky, B.A.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L. Diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: Is the combination of probe-to-bone test and plain radiography sufficient for high-risk inpatients? Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyr, A.J.; Seo, K.; Khurana, J.S.; Choksi, R.; Chakraborty, B. Level of Agreement with a Multi-Test Approach to the Diagnosis of Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018, 57, 1137–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauri, C.; Tamminga, M.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; Juárez Orozco, L.E.; Erba, P.A.; Jutte, P.C.; Lipsky, B.A.; IJzerman, M.J.; Signore, A.; Slart, R.H.J.A. Detection of osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot by imaging techniques: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MRI, white blood cell scintigraphy, and FDG-PET. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, E.; Levine, A.A.; Udyavar, N.R.; Burstin, H.R.; Bhulani, N.; Hoyt, D.B.; Ko, C.Y.; Weissman, J.S.; Britt, L.D.; Haider, A.H.; Maggard-Gibbons, M.A. Disparities in surgical access: A systematic literature review, conceptual model, and evidence map. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Penfield, N.W.; Armstrong, D.G.; Brennan, M.B.; Fayfman, M.; Ryder, J.H.; Tan, T.W.; Schechter, M.C. Evaluation and Management of Diabetes-related Foot Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, M.T.; Abad, C.L.; Safdar, N. Diagnostic accuracy of the physical examination and imaging tests for osteomyelitis underlying diabetic foot ulcers: Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Tan, T.W.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramberg, M.C.T.T.; Lagrand, R.S.; Sabelis, L.W.E.; den Heijer, M.; de Groot, V.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Kortmann, W.; Sieswerda, E.; Peters, E.J.G. Using a BonE BiOPsy (BeBoP) to determine the causative agent in persons with diabetes and foot osteomyelitis: Study protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro-Soares, M.; Hamilton, E.J.; Russell, D.A.; Srisawasdi, G.; Boyko, E.J.; Mills, J.L.; Jeffcoate, W.; Game, F. Guidelines on the classification of foot ulcers in people with diabetes (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 15.0, 2025. Available online: https://www.eucast.org.

- Coşkun, B.; Ayhan, M.; Ulusoy, S. Relationship between Prognostic Nutritional Index and Amputation in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, İ. Treating Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis: A Practical State-of-the-Art Update. Medicina 2021, 57, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prompers, L.; Huijberts, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Jude, E.; Piaggesi, A.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Holstein, P.; Jirkovska, A.; Mauricio, D.; et al. High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitridge, R.; Chuter, V.; Mills, J.; Hinchliffe, R.; Azuma, N.; Behrendt, C.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Conte, M.S.; Humphries, M.; Kirksey, L.; et al. The intersocietal IWGDF, ESVS, SVS guidelines on peripheral artery disease in people with diabetes and a foot ulcer. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elafros, M.A.; Andersen, H.; Bennett, D.L.; Savelieff, M.G.; Viswanathan, V.; Callaghan, B.C.; Feldman, E.L. Towards prevention of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and new treatments. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Li, B.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Kuang, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, S.; Ma, Z.; Li, G. Mechanisms of diabetic foot ulceration: A review. J. Diabetes 2023, 15, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gariani, K.; Pham, T.T.; Kressmann, B.; Jornayvaz, F.R.; Gastaldi, G.; Stafylakis, D.; Philippe, J.; Lipsky, B.A.; Uçkay, I. Three Weeks Versus Six Weeks of Antibiotic Therapy for Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis: A Prospective, Randomized, Noninferiority Pilot Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e1539–e1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrabi, K.; Belczyk, R. Surgical Treatment of Diabetic Foot and Ankle Osteomyelitis. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 2022, 39, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammine, K.; Mouawad, J.; Abou Orm, G.; Assi, C.; Hayek, F. The diabetic sausage toe: Prevalence, presentation and outcomes. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, A.; Chabaud, A.; Desbiez, F.; Descamps, S.; Petrosyan, E.; Letertre-Gilbert, P.; Mrozek, N.; Vidal, M.; Tauveron, I.; Maqdasy, S.; et al. Comparison of microbiological results obtained from per-wound bone biopsies versus transcutaneous bone biopsies in diabetic foot osteomyelitis: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senneville, É.; Lipsky, B.A.; Abbas, Z.G.; Aragón-Sánchez, J.; Diggle, M.; Embil, J.M.; Kono, S.; Lavery, L.A.; Malone, M.; van Asten, S.A.; Urbančič-Rovan, V.; et al. Diagnosis of infection in the foot in diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), e3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, R.A.; Lazarovitch, T.; Boldur, I.; Ramot, Y.; Buchs, A.; Weiss, M.; Hindi, A. Swab cultures accurately identify bacterial pathogens in diabetic foot wounds not involving bone. Diabet. Med. 2004, 21, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senneville, E.; Melliez, H.; Beltrand, E.; Legout, L.; Valette, M.; Cazaubiel, M.; Cordonnier, M.; Caillaux, M.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Mouton, Y. Culture of percutaneous bone biopsy specimens for diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: Concordance with ulcer swab cultures. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamurugan, T.P.; Jagdish, S.; Kate, V.; Chandra Parija, S. Role of bone biopsy specimen culture in the management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Int. J. Surg. 2011, 9, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, H. Concordance of bone culture and deep tissue culture during the operation of diabetic foot osteomyelitis and clinical characteristics of patients. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2023, 49, 2579–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertugrul, M.B.; Baktiroglu, S.; Salman, S.; Unal, S.; Aksoy, M.; Berberoglu, K.; Calangu, S. Pathogens isolated from deep soft tissue and bone in patients with diabetic foot infections. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2008, 98, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senneville, E.M.; Lipsky, B.A.; van Asten, S.A.V.; Peters, E.J. Diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), e3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, M.; Bowling, F.L.; Gannass, A.; Jude, E.B.; Boulton, A.J. Deep wound cultures correlate well with bone biopsy culture in diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2013, 29, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Uçkay, I.; Vuagnat, A.; Assal, M.; Stern, R.; Rohner, P.; Hoffmeyer, P. Two consecutive deep sinus tract cultures predict the pathogen of osteomyelitis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e390–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, S.; Siddiqi, M.A.; Taufiq, I. Diagnostic value of sinus tract culture versus intraoperative bone culture in patients with chronic osteomyelitis. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016, 66 (Suppl. S3), S109–S111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hartemann-Heurtier, A.; Senneville, E. Diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Diabetes Metab. 2008, 34, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senneville, É.; Albalawi, Z.; van Asten, S.A.; Abbas, Z.G.; Allison, G.; Aragón-Sánchez, J.; Embil, J.M.; Lavery, L.A.; Alhasan, M.; Oz, O.; Uçkay, I.; et al. IWGDF/IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes-related foot infections (IWGDF/IDSA 2023). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzer, G.; Strazzabosco, M.; Presi, S.; Furlan, F.; Lora, L.; Benedetti, P.; Bonato, M.; Erle, G.; De Lalla, F. Deep tissue biopsy vs. superficial swab culture monitoring in the microbiological assessment of limb-threatening diabetic foot infection. Diabet. Med. 2001, 18, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manas, A.B.; Taori, S.; Ahluwalia, R.; Slim, H.; Manu, C.; Rashid, H.; Kavarthapu, V.; Edmonds, M.; Vas, P.R.J. Admission Time Deep Swab Specimens Compared with Surgical Bone Sampling in Hospitalized Individuals with Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis and Soft Tissue Infection. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds. 2021, 20, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macauley, M.; Adams, G.; Mackenny, P.; Kubelka, I.; Scott, E.; Buckworth, R.; Biddiscombe, C.; Aitkins, C.; Lake, H.; Matthews, V.; et al. Microbiological evaluation of resection margins of the infected diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, P.G.; Uçkay, I.; Kressmann, B.; Emonet, S.; Lipsky, B.A. The role of anaerobes in diabetic foot infections. Anaerobe 2015, 34, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Asten, S.A.; La Fontaine, J.; Peters, E.J.; Bhavan, K.; Kim, P.J.; Lavery, L.A. The microbiome of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, M.; Johani, K.; Jensen, S.O.; Gosbell, I.B.; Dickson, H.G.; Hu, H.; Vickery, K. Next Generation DNA Sequencing of Tissues from Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers. EBioMedicine. 2017, 21, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johani, K.; Fritz, B.G.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Lipsky, B.A.; Jensen, S.O.; Yang, M.; Dean, A.; Hu, H.; Vickery, K.; Malone, M. Understanding the microbiome of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: Insights from molecular and microscopic approaches. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Raghav, A.; Parwez, I.; Ozair, M.; Ahmad, J. Molecular and culture-based assessment of bacterial pathogens in subjects with diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2018, 12, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age, mean ± SD * | 63.449 ± 12.363 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 80 (74.8%) |

| Any comorbid disease, n (%) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 107 (100%) |

| Hypertension | 100 (93.5%) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 98 (91.5%) |

| Peripheral vascular obstruction | 96 (89.7%) |

| Atherosclerosis | 81 (75.7%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 31 (29%) |

| Chronic renal failure | 26 (24.3%) |

| Venous stasis | 4 (3.7%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (0.9%) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (0.9%) |

| Hepatitis | 1 (0.9%) |

| Lymphedema | 1 (0.9%) |

| Previous antibiotic use | 103 (96.3%) |

| IDSA/IWGDF Classification | No (%) |

| 2 | 5 (4.7) |

| 3 | 69 (64.5) |

| 4 | 33 (30.8) |

| Deep Tissue Cultures (107), n (%) | Bone Cultures (105), n (%) | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 (13.1) | Staphylococcus aureus | 13 (12.2) |

| MRSA | 6 (5.6) | MRSA | 7 (6.7) |

| Escherichia coli | 9 (8.4) | Klebisella pneumoniae | 9 (8.4) |

| Klebisella pneumoniae | 5 (4.7) | Streptococcusspp. | 8 (7.5) |

| Proteus spp. | 5 (4.7) | Escherichia coli | 7 (6.5) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 (4.7) | Corynebacterium striatum | 6 (5.6) |

| Corynebacterium striatum | 4 (3.7) | Proteus spp. | 6 (5.6) |

| Morganella morgagnii | 3 (2.8) | Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 5 (4.7) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3 (2.8) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 (4.7) |

| A.baumannii | 3 (2.8) | Citrobacter spp. | 3 (2.8) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 3 (2.8) | Providencia | 2 (1.9) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 2 (1.9) | Morganella morgagnii | 2 (1.9) |

| Citrobacter spp. | 2 (1.9) | Candida spp. | 1 (0.9) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2 (1.9) | Enterobacter cloacae | 1 (0.9) |

| Achromobacter | 1 (0.9) | Helcococcus kunzii | 1 (0.9) |

| Helcococcus kunzii | 1 (0.9) | Ralstonia picketti | 1 (0.9) |

| Providencia | 1 (0.9) | No growth | 35 (33.3) |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (0.9) | ||

| Candida spp. | 1 (0.9) | ||

| No growth | 42 (39.3) | ||

| Total | 107 (100) | Total | 105(100) |

| Same microorganism isolated | 44 (51.8) |

| Different microorganisms isolated | 9 (10.6) |

| Deep Tissue culture only | 18 (21.2) |

| Bone culture only | 14 (16.5) |

| Total | Deep Tissue | Bone Biopsy | Correlation,n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 27 | 14 | 13 | 12(44.4) |

| Other Gram-positive | 33 | 13 | 20 | 8(24.2) |

| Gram-negative | 73 | 37 | 36 | 23(31.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).