Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

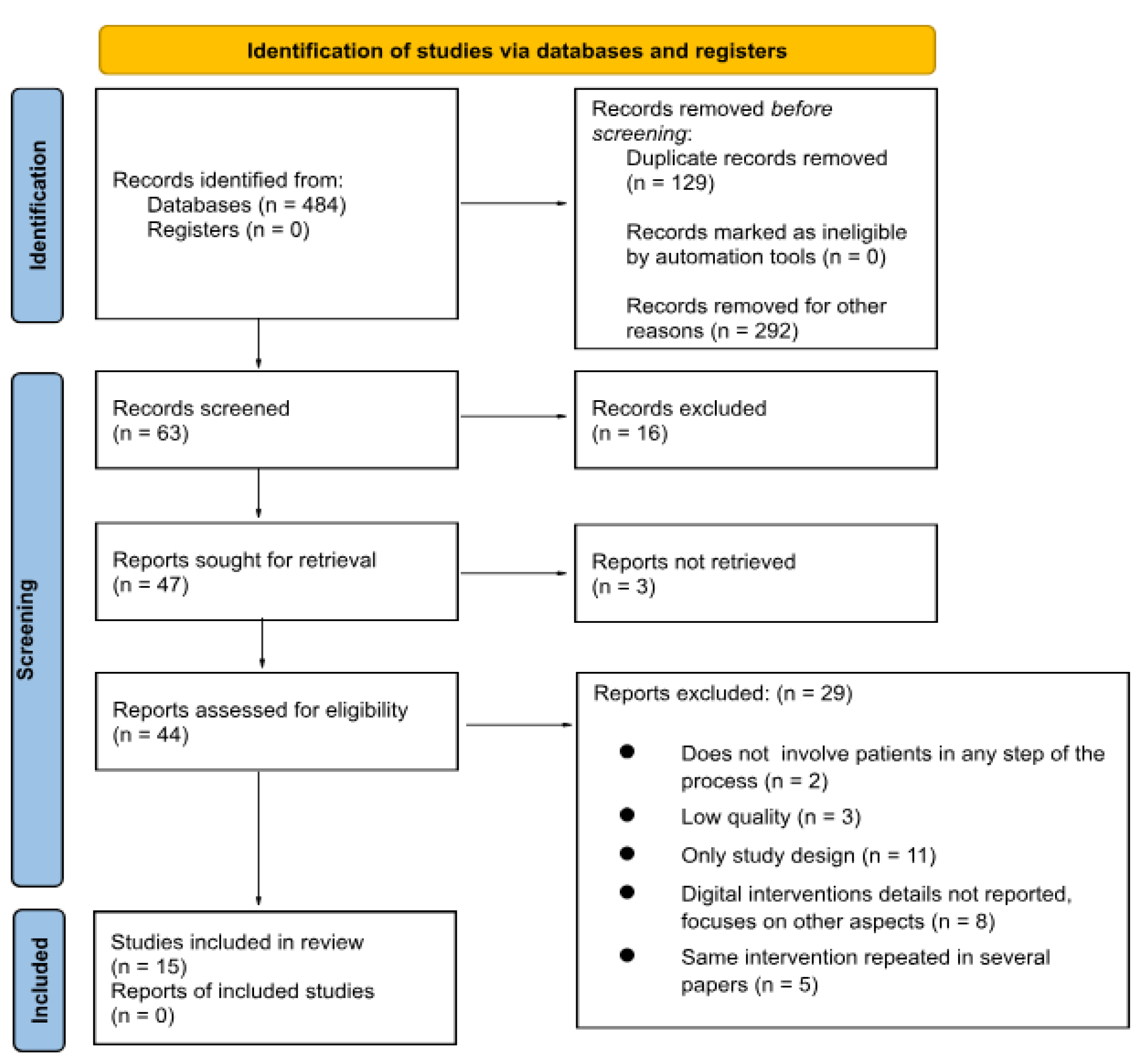

2. Materials and Methods

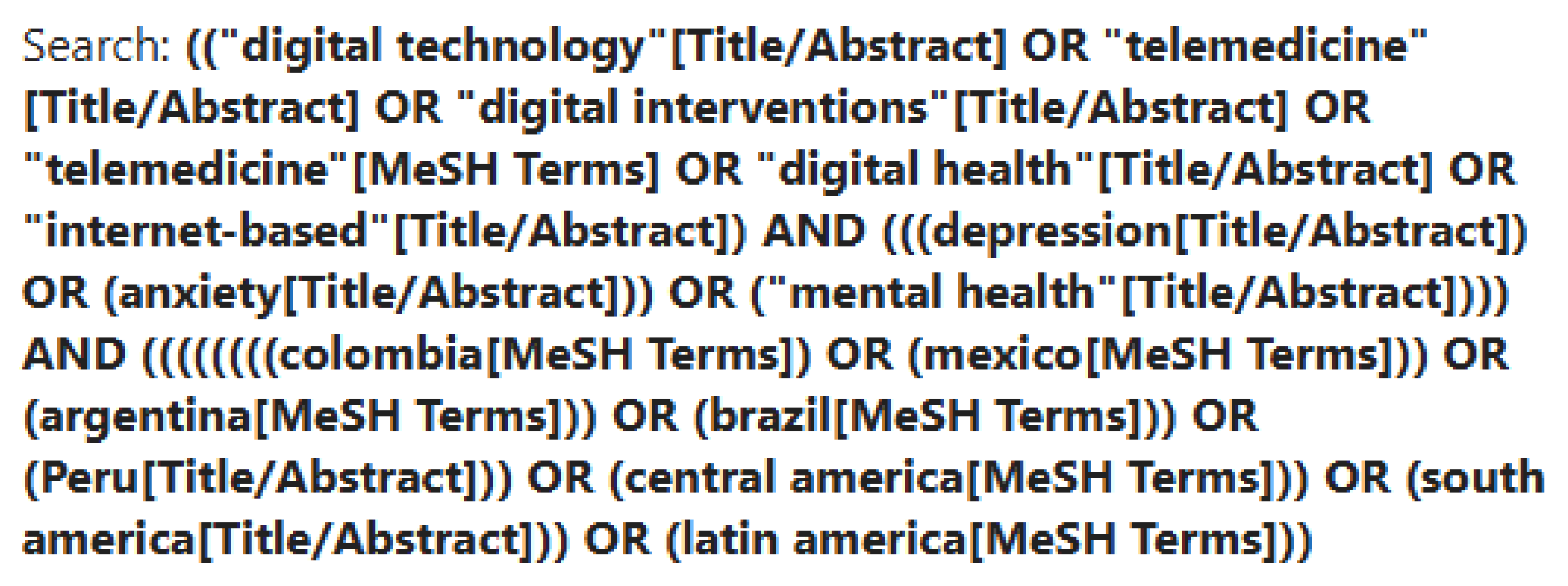

2.1. Information Sources & Search

| Category | Search Terms Combined with AND |

|---|---|

| DHIs | “digital technology” OR “telemedicine” OR “digital interventions” OR “telehealth” OR “digital health” OR “internet-based” OR “e-mental health” |

| MH | “mental health” OR “Depression” OR “Anxiety” |

| Region | “Colombia” OR “Mexico” OR “Brazil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “South America” OR “Central America” OR “Latin America” |

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection & Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

| Author (s), Country, Year | Name of DMHI | MH Disorders | Target Population | Facilitators | Barriers | Study Design | Study Objective | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.De la Cruz-Torralva, Escobar-Agreda, López,. Amaro, Reategui-Rivera & Rojas-Mezarina, Peru, 2024 [20] | Mental Health Accompaniment Program (MHAP) | Depression, Anxiety, Substance Abuse | Recently graduated physicians from the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (n = 75) |

Equal or better results than traditional methods High or increased patient satisfaction |

No time-availability Lack of clinician involvement/ management or organization resistance |

Mixed methods study with follow-up | “This study aimed to evaluate the characteristics and the responses and perceptions of recently graduated physicians who work in rural areas of Peru as part of the Servicio Rural Urbano Marginal en Salud (Rural-Urban Marginal Health Service [SERUMS], in Spanish) toward a telehealth intervention to provide remote orientation and accompaniment in mental health.” | “The MHAP included 4 services: evaluation and screening, self-help, brief intervention, and suicide prevention.” “Implementation of the MHAP is effective in identifying and managing mental health conditions in newly graduated physicians working in rural areas of Peru. Although there is no evidence of digital mental health interventions for these professionals, our findings are consistent with other studies highlighting the usefulness of digital tools in identifying and treating mental health problems.” |

| 2.Zapata-Ospina et al., Colombia, 2024 [21] | LivingLab Telehealth | Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis | Adults receiving telepsychology (n = 371) or telepsychiatry (n = 362) | DI is easier to access | Cost-effectiveness / Insurance coverage More personalization / cultural appropriateness needed |

Descriptive study with follow-up 8-15 days after initial care | “Describe the development and operation of the program and evaluate the degree of satisfaction of the patients.” | “Results of the triage are produced automatically by the medical records programme, which shows the patient’s risk and priority and thus allows interventions to be planned.” “Most of these patients (84.6%) considered the care they received on admission from the TPAH (pre-hospital care team member) to be useful or very useful, and considered that the quality of the telepsychology service was adequate.” “Of this sample, 199 (85.0%) reported that it was the first time they had ever received virtual care, and 69 (29.5%) had difficulty accessing mental health services in person, mainly due to financial problems, distant place of residence and transportation difficulties.” |

| 3.Araya et al., Brazil and Peru, 2021 [22] | Smartphone app | Depression | Patients with clinically significant depressive symptoms with comorbid hypertension and/or Diabetes (n = 880 *Brazil) (n = 432 *Peru) |

DI is easier to access Equal or better results than traditional methods |

More training needed Too complicated/not understand technology Not enough literature / can’t be generalized |

Two randomized control trials with 6-month follow-up | “To investigate the effectiveness of a digital intervention in reducing depressive symptoms among people with diabetes and/or hypertension.” |

“In 2 RCTs of patients with hypertension or diabetes and depressive symptoms in Brazil and Peru, a digital intervention delivered over a 6-week period significantly improved depressive symptoms at 3 months when compared with enhanced usual care. However, the magnitude of the effect was small in the trial from Brazil and the effects were not sustained at 6 months.” |

| 4.Lopes, da Rocha, Svacina, Meyer, Šipka & Berger, Brazil, 2023 [23] | Deprexis | Depression | General population with a high rate of depressive symptoms (n = 312) |

Equal or better results than traditional methods DI is easier to access |

High dropout rate | Randomized control trial | “Replication in Brazil previously reported effects of Deprexis on depressive symptom reduction; whether Deprexis is effective in reducing depressive symptoms and general psychological state in Brazilian users with moderate and severe depression in comparison with a control group that does not receive access to Deprexis.” | “Participants reported medium to high levels of satisfaction with Deprexis. These results replicate previous findings by showing that Deprexis can facilitate symptomatic improvement over 3 months. It also extends previous research by demonstrating that this intervention is effective in a Brazilian sample, which differs culturally and linguistically from the previously studied populations in Germany, Switzerland, and the United States.” |

| 5.Dominguez-Rodriguezet al., Mexico, 2024 [24] | Mixed media (YouTube & PDFs) and IT-Lab | Depression, Anxiety | General adult population 9n = 36) | DI is easier to access Equal or better results than traditional methods DH is less costly |

High dropout rate Too complicated/not understand technology Ensuring data storage safety |

Randomized control trial, with follow-up at 3 and 6 months | “Aims to assess the efficacy of 2 modalities of a self-guided intervention (with and without chat support) in reducing various symptoms” | “For the SGWI group, symptom levels decreased compared to pre- and posttest. But for the SGWI+C group, the reduction in symptoms remained statistically relevant with minor to medium-sized effects for depression, widespread fear, and anxiety.” “Enhancing the utility of web-based interventions for reducing clinical symptoms by incorporating a support chat to boost treatment adherence seemed to improve the perception of the intervention’s usefulness.” |

| 6.Moretti et al., Brazil, 2024 [25] | Online Self-Knowledge Journey | Depression | Adults in technical college (n = 9) Individuals in a public university (n = 18) Non-profit institute employees (n = 30) Platform used by adults (n = 2,145) Private college students (n = 50) |

High or increased patient satisfaction Increased training and support Personalized results |

No time-availability Ensuring data storage safety High dropout rate |

Mixed methods design | “To evaluate the platform’s user engagement and satisfaction in an understudied context.” | “Observed substantial dropout rates across all samples during the usage of the journey, as evidenced by the low completion rates.” “The overall satisfaction in samples 1–3 was high.” “The predominant reason cited for non-completion of the platform’s journey was a lack of time.” |

| 7.Martínez et al., Chile and Colombia, 2021 [26] | Cuida tu Animo | Depression | Adolescents from two schools in each country (n = 199) | Increased training and support High or increased patient satisfaction, Equal or better results than traditional methods |

High dropout rate More personalization / cultural appropriateness needed More training needed |

Pilot mixed- methods study |

“Evaluate the feasibility and acceptability and estimate the effects of an internet-based program for the prevention and early intervention of adolescent depression in high school students implemented in Santiago (Chile) and Medellín (Colombia.” | “The results showed a change in depressive and anxious symptoms in Chilean adolescents, but no significant symptom changes in Colombian adolescents.” “Regarding the feasibility and acceptability, the program was used and accepted by the adolescents. Although the levels of satisfaction were moderate/high (62.1–82.5%), utilization rates were low overall.” |

| 8.Diez-Canseco et al., Peru, 2018 [27] | mHealth | Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis, Substance Abuse, Stress | Adult patients attending public primary health centers (n = 127) Primary Health Care Providers (PHCPs) (n = 22) |

Increased training and support | No time-availability Lack of clinicians involvement/ management or organization resistance More personalization / cultural appropriateness needed |

Multi-phase design with follow-up | “To promote early detection, referral, and access to mental health care for patients with common mental disorders attending primary health care services.” | “With more than 750 screenings completed in real-world circumstances over a 9-week period, it shows the feasibility to integrate the mental health screening into primary care services as a routine procedure.” “Out of 10 patients, 7 actively sought specialized care, and 5 obtained a consultation with a mental health specialist, thus showing promising results for this type of intervention.” |

| 9.Benjet et al., Colombia and Mexico, 2023 [28] | Silvercloud | Depression, Anxiety | University students (n = 1,319) | Reducing shame/stigma DH is less costly DI is easier to access High or increased patient satisfaction |

Not useful for complex and severe cases Not enough literature / can’t be generalized |

Randomized control trial with reassessment after 3 months | “Compare transdiagnostic self-guided and guided internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (i-CBT) with treatment as usual (TAU) for clinically significant anxiety and depression among undergraduates in Colombia and Mexico.” |

“Intent-to-treat analysis found significantly higher adjusted remission rates (ARD) among participants randomized to guided i-CBT than either self-guided i-CBT or TAU, but no significant difference between self-guided i-CBT and TAU” |

| 10.Santa-Cruz et al., Peru, 2023 [29] | ChatBot - Juntos & remote Psychological First Aid (PFA) | Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis, Substance Abuse, Stress, Other | Underserved general population (n = 2027) | DI is easier to access DH is less costly Reducing shame/stigma |

Lack of internet access More training needed |

Retrospective cohort design with 3 month follow-up | “Describe the development, implementation, and participant outcomes of this innovative system of virtual mental health screening and support in the population of Lima affected during the COVID-19 pandemic.” | “Almost 80% of participants screened positive for psychological distress. 63% of people with psychological distress received PFA, and 32.1% of those were also referred for mental health care” “For those who were re-evaluated, significant improvements in SRQ score at 3 months post-intervention were seen in those participating in PFA” |

| 11.Daley, Hungerbuehler, Cavanagh, Claro, Swinton & Kapps, Brazil, 2020 [30] | ChatBot - Vitalk | Depression, Anxiety | General adult population (n = 3,629) | DH is less costly DI is easier to access Time availability increased Reducing shame/stigma |

High dropout rate | Primary evaluation of real-world data over a one month period | “DHI: The goal of the conversations is to help the user reflect on experiences and learn techniques which can help them manage stress, mood and anxiety. A mood tracking tool helps to aid reflection.” “Study: To assess the engagement and effectiveness of Vitalk in reducing mental health symptoms (stress, anxiety, depression) over a one-month period.” |

“Significant reduction in anxiety, depression, and stress scores with large effect sizes - Higher engagement correlated with better outcomes and also found to predict lower anxiety and depressive symptoms at follow up.” “Adult females under 24 years of age (52% 18–24 years, 76% female).” |

| 12.Martínez, Rojas, Martínez, Zitko, Irarrázaval, Luttges & Araya, Chile, 2018 [31] | Remote Collaborative Depression Care (RCDC) Program | Depression | Adolescents ages 13-19 (n = 143) | Time availability increased High or increased patient satisfaction Increased training and support |

Lack of internet access More training needed Lack of clinicians involvement/ management or organization resistance Not useful for complex & severe cases |

2-group, cluster randomized clinical trial with a 12-week follow-up | “Tested the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a remote collaborative care program delivered by primary and specialized mental health teams to enhance the management of adolescent MDD in the Araucanía Region, an underserved area of Chile.” | “The RCDC intervention significantly surpassed enhanced usual care in terms of user satisfaction with psychological treatment. Phone monitoring was perceived as useful and provided them with innovative tools for the comprehensive management of adolescent depression.” “RCDC (at follow-up) for the treatment of adolescent depression did appear to have equivalent effectiveness compared with EUC, achieving comparable levels of depressive symptoms” |

| 13.Alva-Arroyo, Ancaya-Martínez, & Floréz-Ibarra, 2021 ,Peru [32] | Internet HHV (Hospital Hermilio Valdizán), telehealth, & digital platforms | Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis, Substance Abuse, Stress, Other | Patients at Hermilio Valdizán Hospital (n = 4411) |

Increased training and support | Ensuring data storage safety Lack of clinicians involvement/ management or culture organization resistance More training needed Not enough literature / can’t be generalized |

Observation study | “The objective of this article is to present the telehealth experiences in a hospital specialized in mental health in Lima, Peru during the COVID-19 pandemic.” | “Concluded that the implementation of telehealth for the care of the users of the Hermilio Valdizán Hospital contributes to mental health care and reduces the gaps in access to specialized care in psychiatry due to the consequences of COVID-19.” |

| 14.Pérez et al., Colombia, 2020 [33] | Telemedicine | Depression, Anxiety, Other | Patients enrolled for at least a year in a telemedicine program (n = 111) |

Increased training and support | Lack of clinicians involvement/ management or culture organization resistance, More training needed |

Descriptive study | “To describe the experience of physicians and patients in the Telepsychiatry programme at the University of Antioquia’s Faculty of Medicine in the first 12 months after its implementation in eight towns across Antioquia.” | “Most patients and health personnel are satisfied with telemedicine attention and found it of comparable quality to presencial modalities. However, they expressed concern on data confidentiality and low capacity of response in case of emergencies. Patients reported high satisfaction overall.” |

| 15.Gómez-Restrepo, Cepeda, Torrey, Castro, Uribe-Restrepo, Suárez-Obando & Marsch, Colombia, 2021 [34] | Tablet-based screening system & Labbr (mobile app) | Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis, Substance Abuse | Patients attending primary care centers in urban and rural areas (n = 16,188) |

Increased training and support | No time-availability Lack of clinicians involvement/ management or culture organization resistance |

Modified stepped-wedge design with follow-up | “To improve the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of depression and unhealthy alcohol use through a technology-assisted model integrated into primary care.” | “Conducted a total of 22,354 screenings among 16,188 patients with a majority being female.” “10.1% prevalence of GP-confirmed depression and 1.3% of risky alcohol use; improved diagnosis rates due to integrated screening but faced challenges with time constraints.” |

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators

| Author (s), country, year | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| De la Cruz-Torralva, Escobar-Agreda, López,. Amaro, Reategui-Rivera & Rojas-Mezarina, Peru, 2024 [20] | Interventions for Persons | Targeted communication to Persons; Telemedicine | Consultations between remote person and healthcare provider; Transmit targeted health information to person(s) based on health status or demographics |

| Zapata-Ospina et al., Colombia, 2024 [21] | Interventions for Persons | Telemedicine, Data Management | Consultations between remote persons and healthcare providers |

| Araya et al., Peru and Colombia, 2021 [22] | Interventions for Persons | Targeted communication to Persons | Transmit targeted health information to person(s) based on health status or demographics |

| Lopes, da Rocha, Svacina, Meyer, Šipka & Berger, Brazil, 2023 [23] | Interventions for Persons | Personal health tracking | Self-monitoring of health or diagnostic data by the individual |

| Moretti et al., Brazil, 2024 [25] | Interventions for Persons | Targeted communication to Persons | Transmit untargeted health information to an undefined population |

| Dominguez-Rodriguez, Mexico, 2024 [24] | Interventions for Persons | Personal health tracking | Self-monitoring of health or diagnostic data by the individual |

| Martínez, Chile and Colombia, 2021 [26] | Interventions for Persons | Targeted communication to Persons | Simulated human-like conversations with individual(s); Transmit targeted health information to person(s) based on health status or demographics; Peer group for individuals, List health facilities and related information |

| Diez-Canseco, Peru, 2018 [27] | Interventions for healthcare providers | Healthcare provider decision support | Transmit targeted alerts and reminders to person(s) |

| Benjet et al., Colombia and Mexico, 2023 [28] | Interventions for Persons | Personal health tracking | Self-monitoring of health or diagnostic data by the individual |

| Santa-Cruz et al., Peru, 2023 [29] | Interventions for Persons | Targeted communication to Persons | Simulated human-like conversations with individual(s), Identify persons in need of services; Manage referrals between points of service within the health sector |

| Daley, Hungerbuehler, Cavanagh, Claro, Swinton & Kapps, Brazil, 2020 [30] | Interventions for Persons | On-demand communication with Persons | Simulated human-like conversations with individual(s) |

| Martínez, Rojas, Martínez, Zitko, Irarrázaval, Luttges & Araya, Chile, 2018 [31] | Interventions for healthcare providers | Data Management; Healthcare provider decision support | Longitudinal tracking of a person’s health status and services; Managing person-centered structured clinical records; Data storage and aggregation |

| Alva-Arroyo, Ancaya-Martínez, & Floréz-Ibarra, 2021, Peru [32] | Interventions for Persons | Telemedicine | Consultations between remote persons and healthcare providers |

| Pérez et al., Colombia, 2020 [33] | Interventions for Persons | Telemedicine | Consultations between remote persons and healthcare providers |

| Gómez-Restrepo, Cepeda, Torrey, Castro, S., Uribe-Restrepo, Suárez-Obando & Marsch, Colombia, 2021 [34] | Interventions for healthcare providers | Healthcare provider decision support | Screen persons by risk or other health status |

3.3. WHO’s CDISAH

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Use of A.I.

Abbreviations

| CDISAH | Classification of Digital Interventions, Services and Applications in Health |

| DHI | Digital Health Intervention |

| DMHI | Digital Mental Health Intervention |

| LATAM | Latin America |

| MH | Mental Health |

| mhGAP | Mental Health Gap Action Programme |

| RAPS | Rede de Atenção Psicossocial |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix

Appendix A: Coding Used per Database and per Language

| Database | English | Spanish | Portuguese |

| PubMed | ((“digital technology”[Title/Abstract] OR “telemedicine”[Title/Abstract] OR “digital interventions”[Title/Abstract] OR “telemedicine”[MeSH Terms] OR “digital health”[Title/Abstract] OR “internet-based”[Title/Abstract]) AND (((depression[Title/Abstract]) OR (anxiety[Title/Abstract])) OR (“mental health”[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((((((((colombia[MeSH Terms]) OR (mexico[MeSH Terms])) OR (argentina[MeSH Terms])) OR (brazil[MeSH Terms])) OR (Peru[Title/Abstract])) OR (central america[MeSH Terms])) OR (south america[Title/Abstract])) OR (latin america[MeSH Terms])) | ((“Tecnología”[Title/Abstract] OR “telemedicina”[Title/Abstract] OR “digital”[Title/Abstract] OR “telemedicina”[MeSH Terms] OR “digital”[Title/Abstract] OR “internet”[Title/Abstract]) AND (((depresión[Title/Abstract]) OR (ansiedad[Title/Abstract])) OR (“salud mental”[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((((((((colombia[MeSH Terms]) OR (méxico[MeSH Terms])) OR (argentina[MeSH Terms])) OR (brasil[MeSH Terms])) OR (Perú[Title/Abstract])) OR (centroamérica[MeSH Terms])) OR (sudamérica[Title/Abstract])) OR (latinoamérica[MeSH Terms])) | ((“tecnologia digital” OR “telemedicina” OR “intervenções digitais” OR “telessaúde” OR “saúde digital” OR “internet” OR “saúde mental digital”) AND (“saúde mental” OR “depressão” OR “ansiedade”)) AND (“Colômbia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “América do Sul” OR “América Central” OR “América Latina”) |

| APA PsycNet | Any Field: “digital technology” OR “telemedicine” OR “digital interventions” OR “telehealth” OR “digital health” OR “internet-based” OR “e-mental health” AND Any Field: “mental health” OR “Depression” OR “Anxiety” AND Any Field: “Colombia” OR “Mexico” OR “Brazil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “South America” OR “Central America” OR “Latin America” | Any Field: “Colombia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Perú” OR “Sudamérica” OR “Centroamérica” OR “América Latina” OR “Latinoamérica” AND Any Field: “salud mental” OR “depresión” OR “ansiedad” AND Any Field: “tecnología digital” OR “intervenciones digitales” OR “telemedicina” OR “salud digital” OR “internet” OR “salud mental digital” | Any Field: “tecnologia digital” OR “telemedicina” OR “intervenções digitais” OR “telessaúde” OR “saúde digital” OR “internet” OR “saúde mental digital” AND Any Field: “saúde mental” OR “depressão” OR “ansiedade” AND Any Field: (“Colômbia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “América do Sul” OR “América Central” OR “América Latina” |

| Scielo | (digital technology OR telemedicine OR digital interventions OR telehealth OR digital health OR internet-based OR e-mental health) AND (mental health OR depression OR anxiety) AND (Colombia OR Mexico OR Brazil OR Argentina OR Peru OR South America OR Central America) | (“Colombia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Perú” OR “Latinoamérica” OR “sudamérica” OR “centroamérica”) AND (“salud mental” OR “depresión” OR “ansiedad”) AND (“tecnología digital” OR “telemedicina” OR “salud digital” OR “internet”) -COVID-19 -cyberbullying site:scielo.org) | (“tecnologia digital” OR “telemedicina” OR “intervenções digitais” OR “telessaúde” OR “saúde digital” OR “internet” OR “saúde mental digital”) AND (“saúde mental” OR “depressão” OR “ansiedade”) AND (“Colômbia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “América do Sul” OR “América Central” OR “América Latina”) |

| LILACS | ( “digital technology” OR “telemedicine” OR “digital interventions” OR “telehealth” OR “digital health” OR “internet-based” OR “e-mental health”) AND ( “mental health” OR “Depression” OR “Anxiety”) AND ( “Colombia” OR “Mexico” OR “Brazil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “South America” OR “Central America” OR “Latin America”) | (“Colombia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Perú” OR “Sudamérica” OR “Centroamérica” OR “América Latina” OR “Latinoamérica” AND “salud mental” OR “depresión” OR “ansiedad” AND “tecnología digital” OR “intervenciones digitales” OR “telemedicina” OR “salud digital” OR “internet” OR “salud mental digital”) | (“tecnologia digital” OR “telemedicina” OR “intervenções digitais” OR “telessaúde” OR “saúde digital” OR “internet” OR “saúde mental digital”) AND (“saúde mental” OR “depressão” OR “ansiedade”) AND (“Colômbia” OR “México” OR “Brasil” OR “Argentina” OR “Peru” OR “América do Sul” OR “América Central” OR “América Latina”) |

References

- Zhao, X.; Stadnick, N. A.; Ceballos-Corro, E.; Castro, J., Jr.; Mallard-Swanson, K.; Palomares, K. J.; Eikey, E.; Schneider, M.; Zheng, K.; Mukamel, D. B.; Schueller, S. M.; Sorkin, D. H. Facilitators of and barriers to integrating digital mental health into County Mental Health Services: Qualitative interview analyses. JMIR Formative Research 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Viera, C. G.; Cernuzzi, L. C.; Miller, R. S.; Rodríguez-Marín, H. J.; Vieta, E.; Gonzalez Tonanez, M.; Marschi, L. A.; Hidalgo-Mazzei, D. Feasibility of mHealth interventions for depressive symptoms in Latin America: a systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry 2021, 33(3), 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Protecting and promoting mental health in the Americas. 2024. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/60472.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Mental Health Atlas of the Americas 2020; Washington, D.C, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, R.; Ali, A. A.; Puac-Polanco, V.; Figueroa, C.; López-Soto, V.; Morgan, K.; Saldivia, S.; Vicente, B. Mental health in the Americas: an overview of the treatment gap. Revista panamericana de salud pública 2018, 42, e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minoletti, A.; Galea, S.; Susser, E. Community mental health services in Latin America for people with severe mental disorders. Public health reviews 2012, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas Quijada, C.; López-Contreras, N.; López-Jiménez, T.; Medina-Perucha, L.; León-Gómez, B. B.; Peralta, A.; Arteaga-Contreras, K. M.; Berenguera, A.; Queiroga Gonçalves, A.; Horna-Campos, O. J.; Mazzei, M.; Anigstein, M. S.; Ribeiro Barbosa, J.; Bardales-Mendoza, O.; Benach, J.; Borges Machado, D.; Torres Castillo, A. L.; Jacques-Aviñó, C. Social Inequalities in Mental Health and Self-Perceived Health in the First Wave of COVID-19 Lockdown in Latin America and Spain: Results of an Online Observational Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20(9), 5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, Pablo, &; et al. Self-perception of mental health, COVID-19 and associated sociodemographic-contextual factors in Latin America. Cadernos de Saúde Pública [online] [Accessed 9 March 2025]. 40(3), e00157723. [CrossRef]

- Latin America Population 2024 Worldpopulationreview.com. 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/latin-america.

- Dattani, Saloni; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max. “Mental Health”. Data adapted from WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020 via UNICEF. 2023. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/reporting-of-mental-health-system-data-in-the-past-two-years [online resource].

- IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024)–with major processing by Our World in Data. “Anxiety disorders” [dataset]. IHME, Global Burden of Disease, “Global Burden of Disease-Mental Health Prevalence” [original data].

- Aguilar, M. D. La modificación a la Ley General de Salud en materia de salud mental y prevención de adicciones contribuye a respetar el derecho a ejercer la capacidad jurídica de las personas sin discriminación. Comisión De Derechos Humanos De La Ciudad De México. 14 April 2022. https://cdhcm.org.mx/2022/04/la-modificacion-a-la-ley-general-de-salud-en-materia-de-salud-mental-y-prevencion-de-adicciones-contribuye-a-respetar-el-derecho-a-ejercer-la-capacidad-juridica-de-las-personas-sin-discriminacion/.

- Ministerio De Salud-Plataforma Del Estado Peruano. Gobierno promulga Ley de Salud Mental.Noticias-. 23 May 2019. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/noticias/28681-gobierno-promulga-ley-de-salud-mental.

- Sapag, J. C.; Huenchulaf, C. A.; Campos, A.; Corona, F.; Pereira, M.; Veliz, V.; Soto-Brandt, G.; Irarrazaval, M.; Gómez, M.; Abaakouk, Z. Mental Health Global Action Programme (mhGAP) in Chile: Lessons Learned and Challenges for Latin. America and the Caribbean Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2021, 45, NA–NA. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social Régimen legal de Bogotá D.C. Resolución 4886 de 2018 Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. 7 November 2018. https://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=93348.

- Araújo, T. M.; Torrenté, M. O. N. Mental Health in Brazil: challenges for building care policies and monitoring determinants. Epidemiologia e servicos de saude: revista do Sistema Unico de Saude do Brasil 2023, 32(1), e2023098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy on Digital Health 2020-2025. 2021. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445bafbc79ca799dce4d.pdf.

- Wang, Q.; Su, M.; Zhang, M.; Li, R. Integrating Digital Technologies and Public Health to fight covid-19 pandemic: Key Technologies, Applications, challenges and outlook of Digital Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(11), 6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Classification of digital interventions, services and applications in health: a shared language to describe the uses of digital technology for health, 2nd ed. 2023; https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081949.

- De la Cruz-Torralva, K.; Escobar-Agreda, S.; López, P. R.; Amaro, J.; Reategui-Rivera, C. M.; Rojas-Mezarina, L. Assessment of a Pilot Program for Remote Support on Mental Health for Young Physicians in Rural Settings in Peru: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Formative Research 2024, 8(1), e54005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Ospina, J. P.; Gil-Luján, K.; López-Puerta, A.; Ospina, L. C.; Gutiérrez-Londoño, P. A.; Aristizábal, A.; Gómez, M.; García, J. Description of a telehealth mental health programme in the framework of the COVID-19 pandemic in Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría (English ed.) 2024, 53(2), 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya, R.; Menezes, P. R.; Claro, H. G.; Brandt, L. R.; Daley, K. L.; Quayle, J.; Diez-Canseco, F.; Peters, T. J.; Cruz, D. V.; Toyama, M.; Aschar, S.; Hidalgo-Padilla, L.; Martins, H.; Cavero, V.; Rocha, T.; Scotton, G.; Lopes, I. F. A.; Begale, M.; Mohr, D. C.; Miranda, J. J. Effect of a digital intervention on depressive symptoms in patients with comorbid hypertension or diabetes in Brazil and Peru: two randomized clinical trials. Jama 2021, 325(18), 1852–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R. T.; da Rocha, G. C.; Svacina, M. A.; Meyer, B.; Šipka, D.; Berger, T. Effectiveness of an internet-based self-guided program to treat depression in a sample of Brazilian users: randomized controlled trial. JMIR formative research 2023, 7(1), e46326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Sanz-Gomez, S.; González Ramírez, L. P.; Herdoiza-Arroyo, P. E.; Trevino Garcia, L. E.; de la Rosa-Gómez, A.; González-Cantero, J. O.; Macias-Aguinaga, V.; Arenas Landgrave, P.; Chávez-Valdez, S. M. Evaluation and Future Challenges in a Self-Guided Web-Based Intervention With and Without Chat Support for Depression and Anxiety Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Formative Research 2024, 8, e53767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, F.; Bortolini, T.; Hartle, L.; Moll, J.; Mattos, P.; Furtado, D. R.; Fontenelle, L.; Fischer, R. Engagement challenges in digital mental health programs: hybrid approaches and user retention of an online self-knowledge journey in Brazil. Frontiers in Digital Health 2024, 6, 1383999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, V.; Espinosa-Duque, D.; Jiménez-Molina, Á.; Rojas, G.; Vöhringer, P. A.; Fernández-Arcila, M.; Luttges, C.; Irarrázaval, M.; Bauer, S.; Moessner, M. Feasibility and acceptability of “cuida tu Ánimo”(Take care of your mood): an internet-based program for prevention and early intervention of adolescent depression in Chile and Colombia. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18(18), 9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Canseco, F.; Toyama, M.; Ipince, A.; Perez-Leon, S.; Cavero, V.; Araya, R.; Miranda, J. J. Integration of a technology-based mental health screening program into routine practices of primary health care services in Peru (The Allillanchu Project): development and implementation. Journal of medical Internet research 2018, 20(3), e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjet, C.; Albor, Y.; Alvis-Barranco, L.; Contreras-Ibáñez, C. C.; Cuartas, G.; Cudris-Torres, L.; González, N.; Cortés-Morelos, J.; Gutierrez-Garcia, R. A.; Medina-Mora, M. E.; Patiño, P.; Vargas-Contreras, E.; Cuijpers, P.; Gildea, S. M.; Kazdin, A. E.; Kennedy, C. J.; Luedtke, A.; Sampson, N. A.; Petukhova, M. V.; Hani Zainal, N.; Kessler, R. C. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety and depression among Latin American university students: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 2023, 91(12), 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Cruz, J.; Moran, L.; Tovar, M.; Peinado, J.; Cutipe, Y.; Ramos, L.; Astupillo, A.; Rosler, M.; Ravioli, G.; Lecca, L.; Smith, S. L.; Contreras, C. Mobilizing digital technology to implement a population-based psychological support response during the COVID-19 pandemic in Lima, Peru. Global Mental Health 2022, 9, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, K.; Hungerbuehler, I.; Cavanagh, K.; Claro, H. G.; Swinton, P. A.; Kapps, M. Preliminary evaluation of the engagement and effectiveness of a mental health chatbot. Frontiers in digital health 2020, 2, 576361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, V.; Rojas, G.; Martínez, P.; Zitko, P.; Irarrázaval, M.; Luttges, C.; Araya, R. Remote collaborative depression care program for adolescents in Araucanía Region, Chile: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2018, 20(1), e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alva-Arroyo, L. L.; Ancaya-Martínez, M. D. C. E.; Floréz-Ibarra, J. M. Telehealth experiences in a specialized mental health hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública 2021, 38(4), 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, D. C. M.; García, Á. M. A.; Carrillo, R. A.; Cano, J. F. G.; Cataño, S. M. P. Telepsychiatry: a successful experience in Antioquia, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría (English ed.) 2020, 49(4), 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Cepeda, M.; Torrey, W.; Castro, S.; Uribe-Restrepo, J. M.; Suárez-Obando, F.; Marsch, L. A. The DIADA Project: a technology-based model of care for depression and risky alcohol use in primary care centres in Colombia. Revista Colombiana de psiquiatría (English ed.) 2021, 50, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K. Y.; Costafreda, S. G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; Fox, N. C.; Ferri, C. P.; Gitlin, L. N.; Howard, R.; Kales, H. C.; Kivimäki, M.; Larson, E. B.; Nakasujja, N.; Rockwood, K; Samus, Q.; Shirai, K.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Schneider, L. N.; Walsh, S.; Yao, Y.; Sommerlad, A.; Mukadam, N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of The Lancet Standing Commission. The Lancet 2024, 404(10452), 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Lim, C. C.; Cannon, D. L.; Burton, L.; Bremner, M.; Cosgrove, P.; Huo, Y.; McGrath, J. Co-morbidity between mood and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety 2020b, 38(3), 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, Clinic. Mental health disorders: Types, diagnosis & treatment options. 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22295-mental-health-disorders.

- Jiménez-Molina, Á.; Franco, P.; Martínez, V.; Martínez, P.; Rojas, G.; Araya, R. Internet-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of mental disorders in Latin America: a scoping review. Frontiers in psychiatry 2019, 10, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).