Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Motor-vehicle crashes are a leading and persistent cause of unintentional deaths in the United States. Scholarship to understand how manmade interventions and natural phenomena interact to effectuate such calamitous outcomes is longstanding and ongoing. One manmade intervention with long interest in the literature is daylight saving time (DST). Unfortunately, such interest engenders little unanimity on how the natural phenomena attributable to DST interact with travel behavior to affect the frequency and severity of motor-vehicle crashes. In order to advance knowledge on DST-safety interactions the study adopts a multilevel model approach to explore spatial and temporal heterogeneity in fatal crashes the explication of which is not yet evident in the literature. Results suggest analyses of the forty-eight states plus the one state equivalent (District of Columbia) in the contiguous United States mask differences from time zone to time zone on the effects of independent variables known to affect the frequency and severity of fatal crashes. Results also suggest time-of-day and time-zone safety effects are indeed evident. Research which adopts a multilevel model approach to analyze DST-transition safety effects is ongoing. Policy implications highlight the importance of governmental efforts to limit licensure and monitor behavior in order to most effectually decrease the number of fatalities in such motor-vehicle crashes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data

- number of persons police report alcohol involvement;

- DST (yes = 1, no = 0);

- number of persons police report drug involvement;

- latitude in decimal degrees;

- light (dawn or dusk = 1, 0 otherwise);

- longitude in decimal degrees;

- number of persons;

- number of vehicles;

- weather (adverse = 1, 0 otherwise); and

- time zone [17].

- kilometers of travel;

- number of licensed drivers;

- number of motor-vehicle crash fatalities;

- lane-kilometers of road;

- percentage of poor-quality road surfaces; and

- number of registered vehicles from 2001 to 2020 [18].

4. Methodology

- Ycs is number of fatalities or natural log of number of fatalities in crash c in state s;

- βPs are (p = 0, 1, 2, …, P) crash-level coefficients;

- XPcs is crash-level predictor P for crash c in state s;

- rcs is the crash-level error term; and

- σ2 is the variance of crash-level error term rcs.

- γ00 is the y-intercept term for crash effect β0s;

- γ0Q are (q = 1, 2, …, Q) state-level coefficients;

- WQs is state-level predictor Q in state s;

- u0s is the state-level error term; and

- τ00 is the variance of state-level error term u0s.

5. Analysis

5.1. Contiguous United States

5.1.1. Random-Intercept Model Results for Contiguous United States

5.1.2. Random-Coefficients Model Results for Contiguous United States

5.2. Time Zones

5.2.1. Random-Intercept Model Results for Time Zones

5.2.2. Random-Coefficients Model Results for Time Zones

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Top Ten Leading Causes of Death in the U.S. for Age 1-44 from 1981-2023. 2025. Available online: https://wisqars.cdc.gov/animated-leading-causes/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Smith, A. Spring forward at your own risk: daylight saving time and fatal vehicle crashes. Am. Econ. J.: Appl. Econ. 2016, 8, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridstrøm, L.; Ifver, J.; Ingebrigsten, S.; Kulmala, R.; Thomsen, L. Measuring the contribution of randomness, exposure, weather, and daylight to the variation in road accident counts. Accident Anal. Prev. 1995, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aries, M.; Newsham, G. Effect of daylight saving time on lighting energy use: a literature review. Energ. Policy 2008, 36, 1858–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartky, I.; Harrison, E. Standard and daylight-saving time. Sci. Am. 1979, 240, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.; VoPham, T.; Wright, K.; Vetter, C. A chronobiological evaluation of the acute effects of daylight saving time on traffic accident risk. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 729–735.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerhoff, N. The influence of daylight saving time on motor vehicle fatal traffic accidents. Accident Anal. Prev. 1978, 10, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Preusser, D.; Lund, A.; Zador, P.; Ulmer, R. Daylight saving time and motor vehicle crashes: the reduction in pedestrian and vehicle occupant fatalities. Am. J. Public Health 1995, 85, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varughese, J.; Allen, R. Fatal accidents following changes in daylight savings time: the American experience. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, N.; Ghosh, A. The short and long run effects of daylight saving time on fatal automobile crashes. The B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Poli. 2007, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Levinson, D. The effects of daylight saving time on vehicle crashes in Minnesota. J. Safety Res. 2010, 41, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, G.; Davis, J.; Hicks, R. Fatal alcohol-related traffic crashes increase subsequent to changes to and from daylight savings time. Percept. Motor Skill. 1998, 86, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broughton, J.; Hazelton, M.; Stone, M. Influence of light level on the incidence of road casualties and the predicted effect of changing ‘summertime’. J. R. Statist. Soc. A 1999, 162, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sood, R.; Graham, D. Road traffic casualties in Great Britain at daylight savings time transitions: a casual regression discontinuity design analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, R.; Sarma, K. Impact of daylight saving time on road traffic collision risk: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, F.; Darrah, J.; Graham, L.; Berning, A.; Blomberg, R.; Finstad, K.; Griggs, C.; Crandall; Schulman, C.; Kozar, R.; Lai, J.; Mohr, N.; Chenoweth, J.; Cunningham, K.; Babu, K.; Dorfman, J.; Van Heukelom, J.; Ehsani, J.; Fell, J.; Whitehill, J.; Brown, T.; Moore, C. Alcohol and Drug Prevalence Among Seriously or Fatally Injured Road Users. 2022. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/2022-12/Alcohol-Drug-Prevalence-Among-Road-Users-Report_112922-tag.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- United States Department of Transportation. (2022a). Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/research-data/fatality-analysis-reporting-system-fars (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- United States Department of Transportation. Highway Statistics. 2022b. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics.cfm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Raudenbush, S.; Bryk, A. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002.

- Monk, T. Traffic accident increases as a possible indicant of desynchronosis. Chronobiologia 1980, 7, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maas, C.; Hox, J. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methods. 2005, 1, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Geological Survey. The National Map - Data Delivery. 2019. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/NationalMap/data (accessed on 10 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

| Reference | When | Sample | Methodology | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | 1973–1974 | Fatal Accident File of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). | FA 1 DF 2 |

DST decreases motor-vehicle crash fatalities by about −1.00% at spring ST-DST and fall DST-ST transitions. Net decrease in motor-vehicle crash fatalities of −0.70% in March and April of 1974 with DST versus March and April of 1973 without DST. |

| [8] | 1987–1991 | 14,659 crashes fatal to at least one pedestrian plus 60,152 crashes fatal to at least one vehicular occupant from the Fatal Accident Reporting System (FARS) of the NHTSA. | FE 3 | Estimate about 901 less fatal crashes (727 involving pedestrians and 174 involving vehicular occupants) if DST is permanent. |

| [9] | 1975–1995 | Mean number of accidents on days before and after DST transitions (Saturday, Sunday, and Monday) in spring and fall versus mean number of accidents on the same days the week before and after DST transitions in spring and fall from the NHTSA. | t-Test | Statistically significant increase in fatal crashes on the Monday immediately after spring DST transition. Statistically significant increase in fatal crashes on Sunday of fall DST transition. |

| [10] | 1976–2003 | Experimental subsample of fatal crashes on first Sunday of April before DST transitions versus control subsample of fatal crashes on last Sunday of April after DST transitions from the FARS of the NHTSA. | DD 4 | Long-run decrease from −8.00% to −11.00% in fatal crashes involving pedestrians after spring DST transitions. Long-run decrease from −6.00% to −10.00% in fatal crashes involving vehicular occupants after spring DST transitions. Short-run effect on fatal crashes after spring DST transitions is not statistically significant. |

| [2] | 2002–2011 | Exploit quasi-experimental policy change in DST transition date from before 2007 to after 2007 due to the Energy Policy Act of 2005 to analyze overall effect of DST on fatal crashes from the FARS of the NHTSA. | FE 3 RD 5 |

Fatal crashes increase from +5.00% to +6.50% immediately after spring DST transition. Suggests spring DST transition causes more than thirty deaths annually at annual social cost from $120 million to $300 million. |

| [6] | 1996–2017 | Fatal, motor-vehicle crashes (n = 732,835) from the FARS of the NHTSA. | IRR 6 | Fatal, motor-vehicle crash risk increases by about +6.00% in spring, DST-transition week (Monday to Friday). Greatest increase in fatal, motor-vehicle crash risk is from 0400 to 0800. A five-degree change in longitude from east to west within a time zone increases fatal, motor-vehicle crash risk by +4.00% in spring, DST-transition week (Monday to Friday). |

| Level | Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Crash | ||

| Fatalities | Number of fatalities. | |

| lnFatalities | Natural log of number of fatalities. | |

| Alcohol | Number of persons police report alcohol involvement. | |

| DST | DST at time/date of crash. If time or date of crash are in DST then DST = 1, 0 otherwise. | |

| Drugs | Number of persons police report drug involvement. | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | Geographic location in global position coordinates from police crash report. | |

| Light | Light conditions at time of crash. If time is at dawn or dusk then Light = 1, 0 otherwise. | |

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | Geographic location in global position coordinates from police crash report. | |

| Persons | Number of persons. | |

| Vehicles | Number of vehicles. | |

| Weather | Atmospheric conditions at time of crash. If atmospheric conditions are adverse 1 at time of crash then Weather = 1, 0 otherwise. | |

| Zone | Time zone 2 for geographic location of crash. | |

| State | ||

| Aggregate Travel Demand | Vehicle Kilometers of Travel (VKT). | |

| Licensed Drivers | Licensed 3 drivers per 1,000 driving-age population. | |

| Motor-Vehicle Crash Fatalities | Motor-vehicle crash fatalities on functional road 4 system. | |

| Aggregate Road Supply (Lane-Kilometers) | Functional road 5 system. | |

| Poor-Quality Road Surfaces (%) | Percentage of poor 6 quality (rural and urban) National Highway System (NHS) road surfaces. | |

| Registered Vehicles | Automobiles (private and commercial 7). |

| Level (n) | Variable | M 1 | SD 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crash (638,164) | |||

| Fatalities | 1.10 | 0.38 | |

| lnFatalities | 0.06 | 0.22 | |

| Alcohol | 0.26 | 0.49 | |

| DST (Percent) | |||

| Yes | 63.76 | ||

| No | 36.24 | ||

| Drugs | 0.09 | 0.30 | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | +36.59 | 5.00 | |

| Light (Percent) | |||

| Yes | 4.15 | ||

| No | 95.85 | ||

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | −91.70 | 14.19 | |

| Persons | 2.54 | 1.86 | |

| Vehicles | 1.52 | 0.80 | |

| Weather (Percent) | |||

| Yes | 18.92 | ||

| No | 81.08 | ||

| Zone (Percent) | |||

| Eastern | 45.40 | ||

| Central | 34.99 | ||

| Mountain | 6.42 | ||

| Pacific | 13.19 | ||

| State (49) | |||

| Aggregate Travel Demand | 98,459.75 | 99,758.94 | |

| Licensed Drivers | 903.91 | 51.47 | |

| Motor-Vehicle Crash Fatalities | 765.42 | 775.28 | |

| Aggregate Road Supply (Lane-Kilometers) | 279,853.45 | 184,231.26 | |

| Poor-Quality Road Surfaces (Percent) | 9.41 | 12.24 | |

| Registered Vehicles | 2,489,722.38 | 2,832,015.90 |

| Level (n) | Variable | Fatalities 1 | lnFatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crash (638,164) | |||

| Alcohol | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | |

| DST (Yes 1, No 0) | −0.001 | −0.001** | |

| Drugs | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | +0.001*** | +0.01*** | |

| Light (Dawn or Dusk = 1, Otherwise = 0) | +0.01** | +0.003** | |

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | −0.001*** | −0.001*** | |

| Persons | +0.07*** | +0.04*** | |

| Vehicles | −0.04*** | −0.02*** | |

| Weather (Adverse = 1, Otherwise = 0) | +0.001 | +0.001 | |

| Zone | |||

| Eastern | Referent 2 | Referent | |

| Central | +0.01 | +0.003 | |

| Mountain | −0.03*** | −0.02*** | |

| Pacific | −0.06*** | −0.04*** | |

| State (49) | |||

| Intercept | +1.11*** | +0.07*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | +0.0001 | +0.00004 |

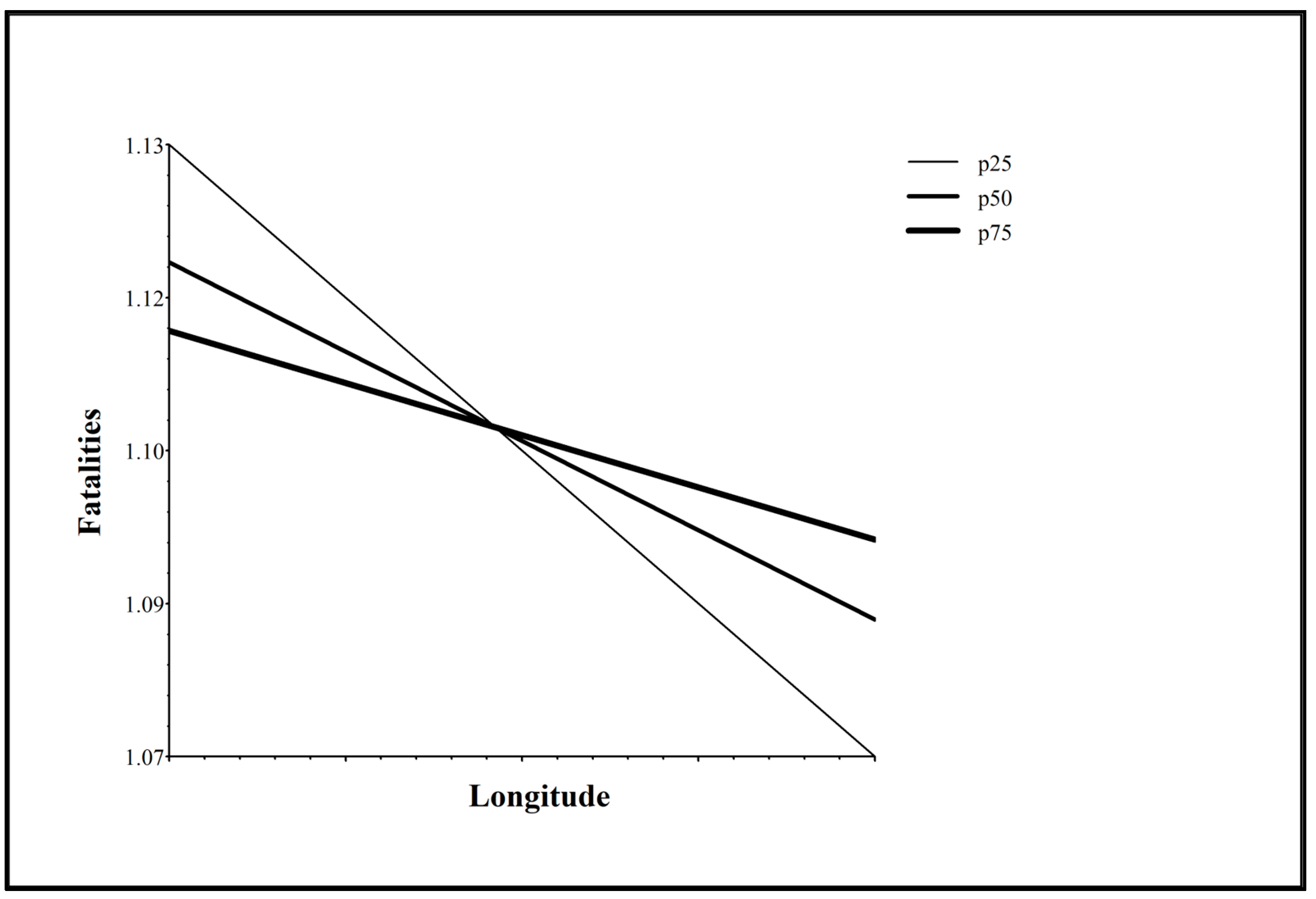

| Level (n) | Variable | Fatalities 1 | lnFatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crash (638,164) | |||

| Alcohol | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | |

| DST (Yes = 1, No = 0) | −0.001 | −0.001** | |

| Drugs | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | |||

| Intercept | +0.001*** | +0.001*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | −0.00002*** | −0.00001*** | |

| Light (Dawn or Dusk = 1, Otherwise = 0) | +0.01** | +0.003** | |

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | |||

| Intercept | −0.001*** | −0.001*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | +0.00001*** | +0.00001*** | |

| Persons | +0.07*** | +0.04*** | |

| Vehicles | −0.04*** | −0.02*** | |

| Weather (Adverse = 1, Otherwise = 0) | +0.001 | +0.001 | |

| Zone | |||

| Eastern | Referent 2 | Referent | |

| Central | +0.01* | +0.01 | |

| Mountain | −0.02** | −0.01** | |

| Pacific | −0.05*** | −0.03*** | |

| State (49) | |||

| Intercept | +1.10*** | +0.07*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | +0.0001 | +0.00004 |

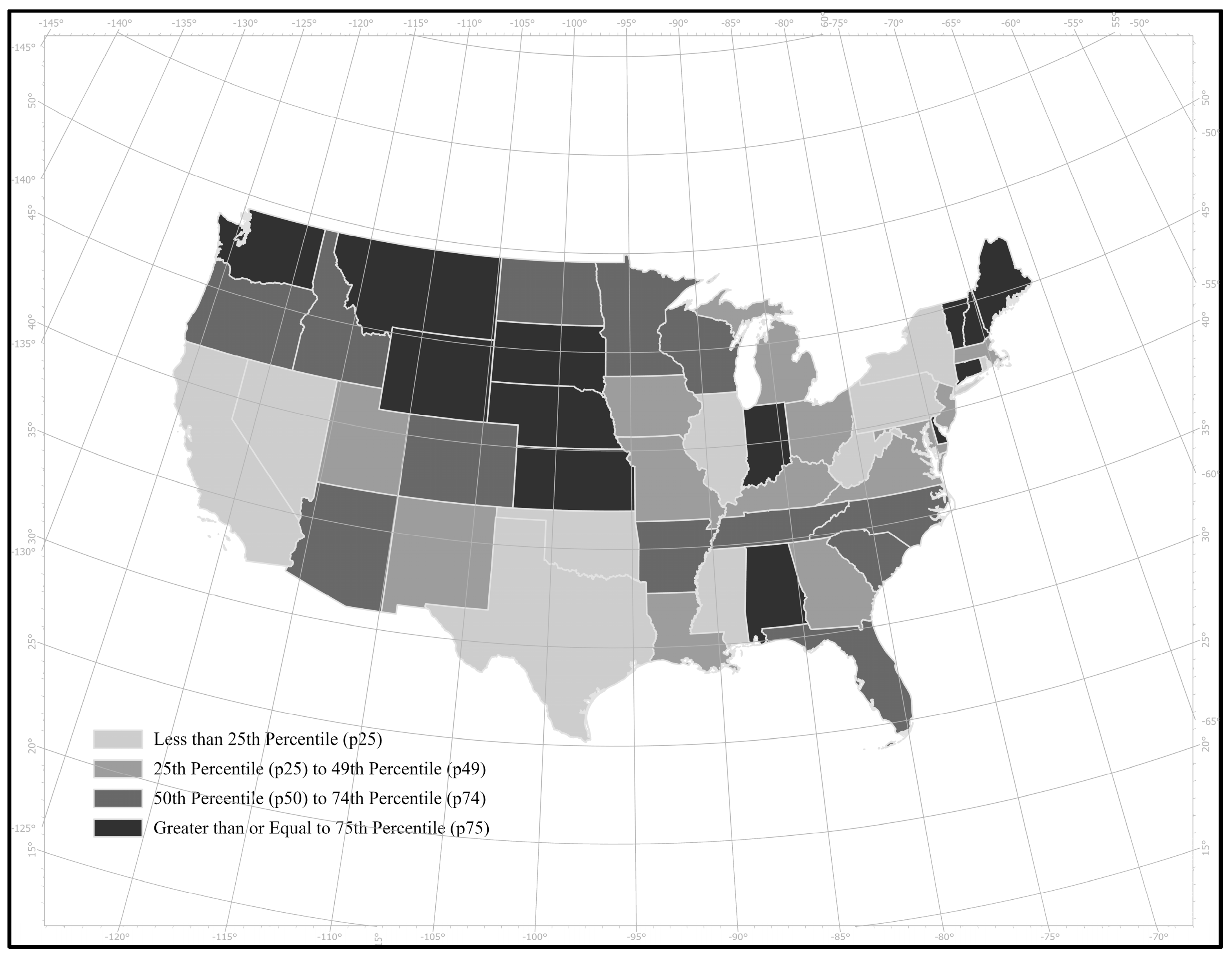

| Time Zone (n) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific plus Mountain (125,160) | Central (223,283) | Eastern (289,721) | |||||

| Level (n) | Variable | M 1 | SD 2 | M | SD | M | SD |

| Crash (638,164) | |||||||

| Fatalities | 1.10 | 0.40 | 1.11 | 0.41 | 1.09 | 0.35 | |

| lnFatalities | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.20 | |

| Alcohol | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.47 | |

| DST (Percent) | |||||||

| Yes | 58.19 | 65.45 | 64.87 | ||||

| No | 41.81 | 34.55 | 35.13 | ||||

| Drugs | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.30 | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | +37.83 | 4.55 | +35.58 | 4.84 | +36.83 | 4.23 | |

| Light (Percent) | |||||||

| Yes | 4.75 | 3.63 | 4.29 | ||||

| No | 95.25 | 96.37 | 95.71 | ||||

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | −116.37 | 5.43 | −92.83 | 4.57 | −80.17 | 4.23 | |

| Persons | 2.68 | 2.02 | 2.51 | 1.86 | 2.49 | 1.79 | |

| Vehicles | 1.51 | 0.85 | 1.52 | 0.76 | 1.52 | 0.81 | |

| Weather (Percent) | |||||||

| Yes | 13.64 | 19.32 | 20.88 | ||||

| No | 86.36 | 80.68 | 79.12 | ||||

| Time Zone (n) | |||||||

| Pacific plus Mountain (11) | Central (16) | Eastern (22) | |||||

| Level (n) | Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| State (49) | |||||||

| Aggregate Travel Demand | 94,050.90 | 146,701.55 | 94,710.32 | 89,777.87 | 103,391.03 | 81,824.57 | |

| Licensed Drivers | 906.93 | 35.46 | 908.37 | 48.97 | 899.16 | 60.83 | |

| Motor-Vehicle Crash Fatalities | 699.35 | 978.00 | 807.76 | 786.65 | 767.67 | 687.54 | |

| Aggregate Road Supply (Lane-Kilometers) | 241,915.43 | 143,322.41 | 395,764.46 | 196,280.28 | 214,523.55 | 157,537.50 | |

| Poor-Quality Road Surfaces (Percent) | 5.53 | 5.17 | 7.05 | 3.80 | 13.07 | 17.12 | |

| Registered Vehicles | 2,570,613.89 | 4,709,974.36 | 2,125,533.57 | 2,013,478.82 | 2,714,141.22 | 2,171,491.90 | |

| Time Zone (n) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific plus Mountain (125,160) | Central (223,283) | Eastern (289,721) | |||||

| Level (n) | Variable | Fatalities 1 | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities |

| Crash (638,164) | |||||||

| Alcohol | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | |

| DST (Yes = 1, No = 0) | +0.01** | +0.003* | −0.02*** | −0.02*** | −0.02*** | −0.02*** | |

| Drugs | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | +0.01*** | +0.003*** | −0.000004 | +0.0001 | +0.002*** | +0.001*** | |

| Light (Dawn or Dusk = 1, Otherwise = 0) | +0.005 | +0.003 | +0.01** | +0.01** | +0.002 | +0.001 | |

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | +0.003*** | +0.002*** | −0.003*** | −0.002*** | −0.001*** | −0.001*** | |

| Persons | +0.08*** | +0.04*** | +0.08*** | +0.04*** | +0.06*** | +0.03*** | |

| Vehicles | −0.05*** | −0.02*** | −0.03*** | −0.01*** | −0.03*** | −0.02*** | |

| Weather (Adverse = 1, Otherwise = 0) | −0.002 | −0.0003 | +0.001 | +0.001 | +0.002 | +0.001 | |

| Time Zone (n) | |||||||

| Pacific plus Mountain (11) | Central (16) | Eastern (22) | |||||

| Level (n) | Variable | Fatalities | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities |

| State (49) | |||||||

| Intercept | +1.08*** | +0.05*** | +1.12*** | +0.07*** | +1.09*** | +0.05*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | −0.0004* | −0.0002* | +0.0001 | +0.00005 | +0.0001 | +0.0001* | |

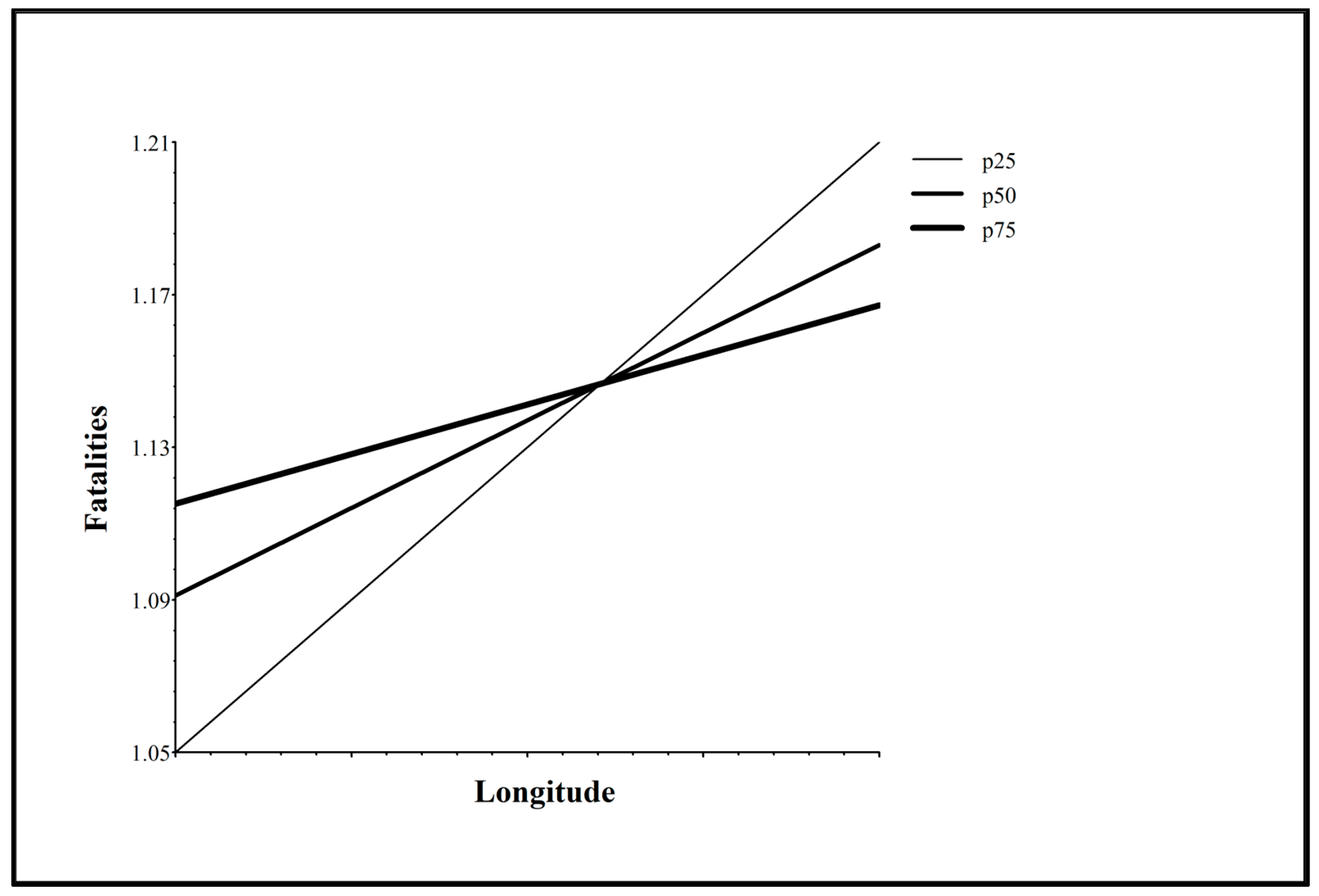

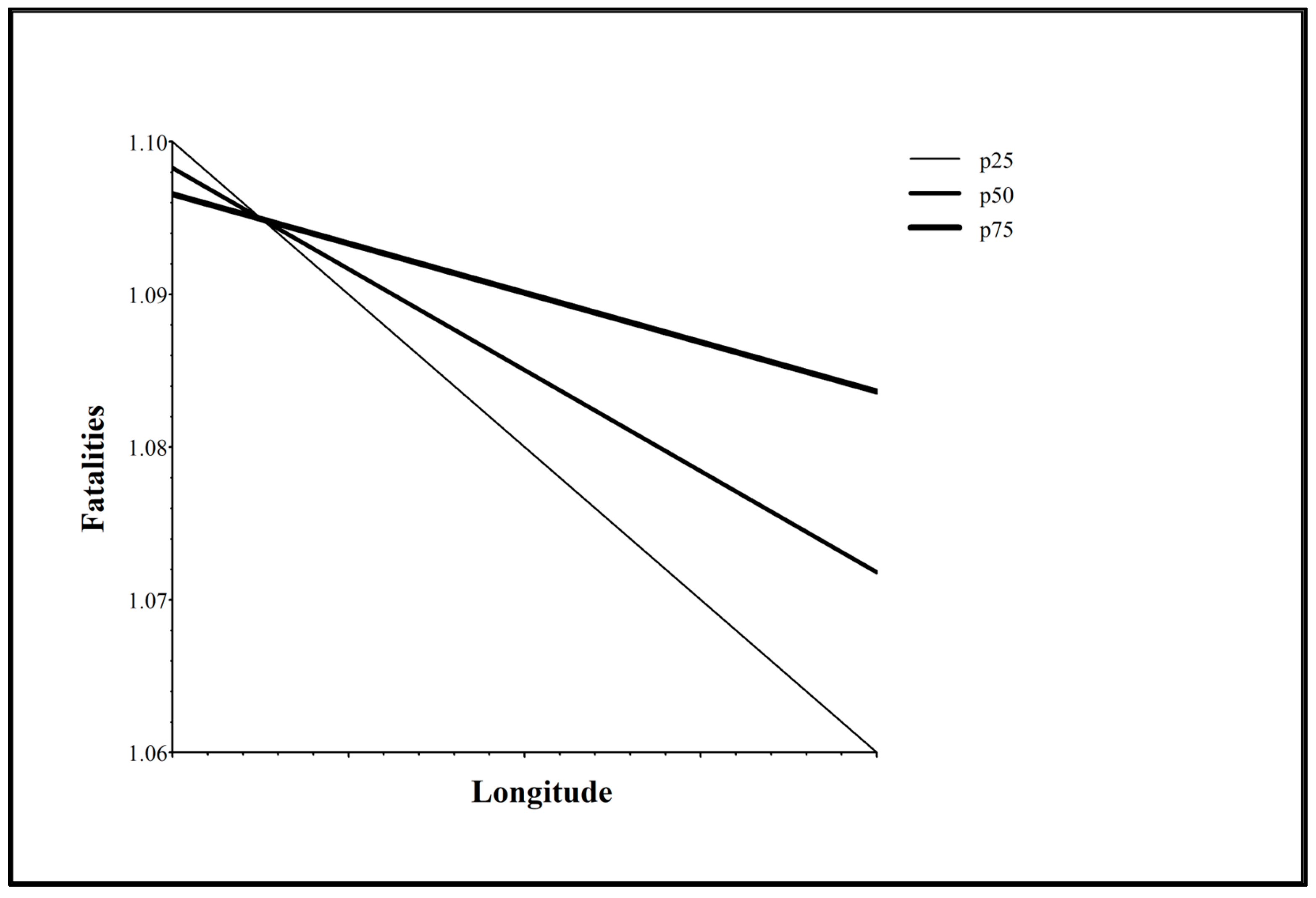

| Time Zone (n) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific plus Mountain (125,160) | Central (223,283) | Eastern (289,721) | |||||

| Level (n) | Variable | Fatalities 1 | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities |

| Crash (638,164) | |||||||

| Alcohol | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | +0.02*** | +0.01*** | |

| DST (Yes = 1, No = 0) | +0.01** | +0.003* | −0.005*** | −0.003*** | −0.002 | −0.002** | |

| Drugs | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | +0.03*** | +0.02*** | |

| Latitude (Decimal Degrees) | |||||||

| Intercept | +0.002 | +0.001 | −0.0001 | +0.00001 | +0.002*** | +0.001*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | |||||||

| Light (Dawn or Dusk = 1, Otherwise = 0) | +0.004 | +0.003 | +0.01** | +0.01** | +0.002 | +0.001 | |

| Longitude (Decimal Degrees) | |||||||

| Intercept | +0.005*** | +0.003*** | −0.002*** | −0.001*** | −0.001*** | −0.001*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | −0.05*** | −0.05*** | +0.00001 | +0.00001 | +0.00002*** | +0.00001*** | |

| Persons | +0.08*** | +0.04*** | +0.08*** | +0.04*** | +0.06*** | +0.03*** | |

| Vehicles | −0.05*** | −0.02*** | −0.03*** | −0.01*** | −0.03*** | −0.02*** | |

| Weather (Adverse = 1, Otherwise = 0) | −0.002 | −0.0002 | +0.001 | +0.001 | +0.001 | +0.001 | |

| Time Zone (n) | |||||||

| Pacific plus Mountain (11) | Central (16) | Eastern (22) | |||||

| Level (n) | Variable | Fatalities | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities | Fatalities | lnFatalities |

| State (49) | |||||||

| Intercept | +1.12*** | +0.07*** | +1.12*** | +0.07*** | +1.08*** | +0.05*** | |

| Licensed Drivers | +0.001 | +0.0004 | +0.0001 | +0.00004 | +0.0001 | +0.0001* | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).