1. Introduction

Liver cancer (LC) is a significant global health concern, ranking as one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Recent global statistics position liver cancer as the sixth most prevalent cancer, following breast, lung, colorectal, prostate and gastric cancers and as the third leading cause of cancer mortality. In 2020, approximately 905,700 new cases and 830,200 deaths from LC occurred worldwide [

1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of LC, accounts for nearly 90% of all cases [

2]. Various imaging techniques such as ultrasound, elastography, MRI and CT scans detect LC, with CT scans providing detailed images of internal structures [

3]. However, CT imaging encounters challenges in detecting and diagnosing liver abnormalities accurately. The liver’s varying sizes and shapes cause incorrect segmentation due to the similarity in intensity between tumors and surrounding tissues and unclear lesion boundaries. These factors make manual annotation by radiologists time-intensive and error-prone, leading to inconsistencies in diagnosis.

Medical image segmentation achieves progress in improving cancer diagnosis accuracy and computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems assist in the detection, classification and segmentation of tumours on medical images, reduces radiologists’ workload and increases diagnostic consistency [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), automate this segmentation process. Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) and U-Net architectures also segment liver tumors by performing pixel-wise classification [

10]. Despite their high accuracy compared to manual segmentation, such models require significant computational resources, complicating deployment on edge devices with limited processing power and memory. Large servers are necessary to run these models, causing issues like bandwidth usage, data security, high server costs and substantial carbon footprints due to increased energy consumption compared to resource-constrained embedded systems. Thus, resource-efficient models are needed for accurate liver tumor segmentation on constrained devices.

Liver tumor segmentation employs traditional image processing, supervised, and unsupervised learning methods. Traditional techniques like thresholding [

11], Canny edge detection [

12], and watershed segmentation [

13] differentiate tumors from normal tissue via edge detection and intensity thresholding. Thresholding uses intensity values to separate objects; watershed segmentation applies gradients to define boundaries. These methods struggle with medical image complexity: tumors have irregular shapes, varied sizes, and intensity values similar to surrounding tissues, causing errors [

14]. Traditional approaches often require manual or semi-automatic intervention, increasing reliance on expert input for accuracy.

Unsupervised learning methods address limitations in traditional techniques by segmenting tumors without labeled data. Notable methods include clustering-based techniques and edge-based algorithms. For instance, Al-Kofahi et al. [

15] introduced a multi-scale Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) filter for histopathology images to detect nuclei of varying sizes. Kong et al. [

16] developed a generalized LoG filter (gLoG) to detect elliptical nuclei in histopathology images, which can apply to LC segmentation in CT scans. Despite their potential, unsupervised methods require careful parameter tuning, are sensitive to noise and struggle to define tumor boundaries with low contrast [

17]. Combining unsupervised techniques with region-based methods, such as Active Contour Models (ACM) [

18] and marker-based watershed transforms [

19], improves segmentation accuracy but remains computationally expensive and less generalizable across datasets.

CNNs, FCNs and U-Net variants dominate the field of medical image analysis due to their ability to learn hierarchical features from complex medical images. For instance, Saha Roy et al. [

20] proposed an automated model that utilizes Mask R-CNN followed by Maximally Stable Extremal Regions (MSER) for tumor identification, enabling multi-class tumor classification. Chen et al. [

21] proposed MS-FANet, a multi-scale feature attention network that performs liver tumor segmentation through multi-scale attention mechanisms which boost segmentation capabilities while capturing both global and local context. Lakshmi et al. [

22] designed the Adaptive SegUnet++ (ASUnet++) framework and optimized it with the Enhanced Lemurs Optimizer (ELO) for tumor segmentation and classification. The authors’ model tackles traditional machine learning hurdles including slow training times and gradient explosion issues as well as overfitting using both residual connections and multiscale approaches. Reyad et al. [

23] proposed an architecture optimization framework for hybrid deep residual networks in liver tumor segmentation, utilizing a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to improve segmentation accuracy and model efficiency. Di et al. [

24] developed a framework for automatic liver tumor segmentation which integrates 3D U-Net architecture with hierarchical superpixels and SVM-based classification, achieving robust performance on noisy and low-contrast CT images. Liu et al. [

25] introduced PA-Net, a phase attention network that fuses venous and arterial phase features of CT images for liver tumor segmentation, effectively leveraging phase-specific information to enhance segmentation performance. CNN-based approaches have shown powerful representation abilities together with resilience to different image appearances. However, CNNs are inherently limited in modeling long-range dependencies, which can lead to suboptimal segmentation outcomes. Specifically, the localized receptive fields of convolutional operations restrict the network’s focus to local context rather than global context [

26].

Transformers which were initially created for sequence-to-sequence prediction tasks now play a primary role in computer vision tasks. Transformers demonstrate outstanding performance across multiple computer vision tasks including image classification [

27], object detection [

28], semantic segmentation [

29] and generative tasks like text-to-image synthesis [

25]. Transformers achieve success because their self-attention mechanism provides large receptive fields and long-range dependency capturing abilities. Medical image segmentation tasks have seen multiple proposals for hybrid methods that integrate both CNNs and Transformers. For instance, Balasubramanian et al. [

30] proposed APESTNet, a Mask R-CNN-based Enhanced Swin Transformer Network for tumor segmentation and classification. This method combines the strengths of Mask R-CNN with the attention mechanisms of the Swin Transformer to improve segmentation accuracy. Chen et al. [

31] introduced TransUNet, a cascaded architecture that integrates CNN and Transformer modules to enhance segmentation performance. Ni et al. [

32] presented DA-Tran, a domain-adaptive transformer network for multiphase liver tumor segmentation. DA-Tran leverages domain adaptation techniques to effectively integrate multiphase CT images, improving segmentation accuracy and robustness across varying imaging conditions.

Despite their accuracy, existing models require substantial memory and computational power, which are unsuitable for edge devices like Jetson Nano. These models operate on server systems, requiring sensitive patient data transmission over the internet and exposing data to privacy and security risks. High server energy consumption limits feasibility in resource-constrained environments. This problem is now actively discussed in various domains: recent work in predictive model optimization demonstrates how tailored loss functions that balance accuracy and hardware constraints enable edge deployment [

33], while hybrid training frameworks that integrate domain-specific priors show improved convergence efficiency [

34?]. Inspired by these advances, there is a need to optimize segmentation models to reduce their size and power use while preserving accuracy, enabling deployment on edge devices for real-time, secure, and energy-efficient tumor segmentation. This study proposes a novel approach to optimize the Swin-UNet model for efficient liver cancer segmentation on edge devices, balancing model size and Area Under the Curve (AUC). Contributions include:

Model Size Optimization: The discrete design space of Swin-UNet achieves a balance between model size and accuracy, enabling deployment on memory-constrained devices like Jetson Nano.

Quadratic Penalty Objective Function: A quadratic penalty-based objective function balances model size and AUC, encouraging compact, accurate models.

Search and Rescue Algorithm: The Search and Rescue algorithm identifies optimal configurations, yielding an optimized model termed SAR-Swin-UNet.

Focal AUC Loss Function: The Focal AUC loss function addresses class imbalance during training, enhancing the model’s ability to segment minority class pixels.

This approach facilitates accurate tumor segmentation on edge devices, ensuring real-time analysis with data security and energy efficiency.

2. Preliminary Knowledge

This section covers key computer vision architectures: Transformers for feature extraction and U-Net for segmentation. Transformers excel at feature extraction, particularly in image classification; U-Net optimizes image segmentation. The section details both architectures with key equations and variable explanations.

2.1. The Transformer Model

The Transformer architecture, introduced by Vaswani et al. [

35], revolutionizes sequence-based models by replacing recurrent mechanisms with self-attention. This enables parallel input processing and improves computational efficiency. The core operation is scaled dot-product attention, defined as follows,

where,

Q,

K and

V are matrices representing the query, key and value vectors, respectively. The dimensions of these matrices are as follows:

where

n is the sequence length (number of tokens),

is the dimensionality of the query and key vectors and

is the dimensionality of the value vectors. The attention mechanism computes a sum of the value vectors, where the weights are determined by the similarity between the query and key vectors. This self-attention mechanism is applied to model dependencies across the entire sequence. In the context of image-based tasks, this model is typically applied after embedding image patches into tokens, as in the Vision Transformer (ViT), which we discuss in the next subsection.

2.2. The Vision Transformer (ViT)

The Vision Transformer (ViT) [

36], adapts the Transformer architecture to image classification tasks by treating image patches as tokens. Given an input image

, where

H is the height,

W is the width and

C is the number of channels, the image is divided into non-overlapping patches of size

. These patches are then flattened and projected into an embedding space. The projection of patch

can be formulated as:

where

is the embedding matrix,

is the embedding bias and

is the number of patches. Each embedded patch is treated as a token and passed through the Transformer layers. The model utilizes multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks, as described previously. However, ViT relies heavily on large datasets for training and performs well when pre-trained on large-scale data and fine-tuned on specific tasks. The advantage of ViT lies in its ability to capture global dependencies across image patches, which is a limitation in conventional CNNs that rely on localized receptive fields. However, ViT requires significant computational resources and large datasets to perform optimally.

2.3. The Swin Transformer

The Swin Transformer [

37] presents a modification to the traditional Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture by addressing the challenges associated with computational complexity when working with high-resolution images. Unlike ViT’s global self-attention across all image patches, Swin Transformer employs local window-based attention. This reduces computational costs, enhancing scalability for large images. It also uses a hierarchical structure that progressively enlarges the receptive field, enabling capture of local and global features across scales.

Swin Transformer applies attention within non-overlapping local windows. The model computes self-attention within each window independently and aggregates outputs. Its key innovation—a shifting window mechanism applied to successive transformer layers—captures long-range dependencies between neighboring regions, overcoming limitations of strictly local attention. The shifted-window attention mechanism is defined as:

where,

Q,

K and

V are the query, key and value matrices, respectively and

is the dimensionality of the key vectors. The term

represents the shift between windows that occurs at successive layers of the model. This shift is critical for allowing information to propagate between neighboring windows, ensuring that global dependencies can still be captured, despite the local nature of the attention in the first few layers. The introduction of the shift operation helps the Swin Transformer overcome the limitations of purely local attention, providing the benefits of both local and global feature learning.

To clarify the role of each variable in the equation: - : The query matrix, where n is the number of patches in the window and is the dimensionality of the query vector. - : The key matrix, which has the same shape as the query matrix. - : The value matrix, used to compute the sum of the values based on the attention scores. - : The shift term introduced between successive layers to enable the exchange of information between neighboring windows.

Unlike the original Transformer where attention is computed globally across the entire image, the Swin Transformer confines attention within local windows at the early layers of the model, dramatically reducing computational complexity. The local-to-global attention mechanism is achieved by shifting the window between layers, gradually increasing the receptive field and allowing the model to capture long-range dependencies. This hierarchical design makes the Swin Transformer particularly well-suited for vision tasks such as image classification and object detection, where both fine-grained details and global context are important.

In contrast to the Vision Transformer, where the attention mechanism is applied globally across the entire input sequence (i.e., all patches in the image), the Swin Transformer introduces a more efficient mechanism by limiting attention to small, local windows. However, the shift in windows at each layer ensures that information is shared across windows, thus enabling the model to learn long-range dependencies. The computational complexity of the self-attention operation in the Swin Transformer is reduced to , where N is the number of patches and W is the window size, as opposed to the complexity in ViT, which computes attention globally for all image patches. This reduction in complexity allows Swin Transformer to scale to much larger images without sacrificing performance.

ViT and Swin Transformer differ in attention handling, ViT applies global attention, incurring high computational costs, while Swin restricts attention to local regions and uses shifting windows to propagate information. This strategy improves efficiency and scalability for high-resolution images. Swin Transformer thus combines local window-based attention with a hierarchical structure, reducing computational complexity while capturing local and global dependencies, improving vision task efficiency.

2.4. U-Net for Segmentation

U-Net, introduced by Ronneberger et al. [

38], is a convolutional neural network designed for semantic segmentation, notably in medical imaging. Its encoder-decoder structure uses skip connections to recover spatial information lost during encoder downsampling. The encoder comprises convolutional layers that progressively reduce input resolution, extracting abstract features. At layer

l,

where

denotes the convolutional filter at layer

l, ∗ is the convolution operation,

is the bias term, and

is the activation function (typically ReLU). This process reduces spatial resolution and increases feature map depth, enabling capture of higher-level abstract features representing input content. The decoder reverses the encoder’s downsampling using upsampling layers, often transposed convolutions, to restore feature map resolution. The upsampling operation at decoder layer

l is:

where

denotes transposed convolution filters and

is the upsampled feature map. Skip connections between encoder and decoder layers transfer fine-grained spatial information from encoder to decoder, preserving precise localization of segmentation boundaries. This U-Net design ensures accurate and spatially precise segmentation masks. The decoder’s feature map passes through an activation function: softmax for multi-class segmentation or sigmoid for binary segmentation. The network computes the final segmentation mask as:

In this equation, and are the final weights and biases and is the last feature map produced by the decoder. The architecture of U-Net, with its careful design of encoder-decoder structures and skip connections, is particularly well-suited for applications requiring precise, pixel-level segmentation, such as in medical imaging tasks.

U-Net addresses a distinct task compared to Transformer-based models like Vision Transformer (ViT) or Swin Transformer. Transformers focus on feature extraction, particularly image classification, where they extract semantic features and classify images using global contexts. While effective for classification, their self-attention mechanisms and reliance on large training datasets increase computational costs. They also struggle with pixel-level precision tasks like segmentation. U-Net’s encoder-decoder structure with skip connections captures high-level features and spatial details, enabling effective medical image segmentation where pixel accuracy matters. The architecture preserves spatial information lost in deeper networks, making it ideal for such tasks. Hence, Transformers suit tasks needing global context, like classification, U-Net excels in segmentation requiring precise localization for accurate predictions. Whereas, the overall Swin-Unet model outperforms other architectures in both aspects.

3. Proposed Methodology

This section details the methodology for optimizing Swin-UNet for liver cancer segmentation on memory-constrained edge devices. The approach combines four components ensuring high accuracy under edge device constraints.

The methodology integrates Swin-UNet, merging Swin Transformer and U-Net for medical image segmentation. Swin Transformer captures local and global features critical for segmentation accuracy. The Search and Rescue (SAR) algorithm adjusts hyperparameters to minimize an objective function balancing accuracy and model size. The objective function optimizes the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for classification performance and model size for edge deployment. AUC focal loss prioritizes hard examples (e.g., complex lesions), improving segmentation robustness. Mathematical formulations underpin the optimization process, justifying its effectiveness.

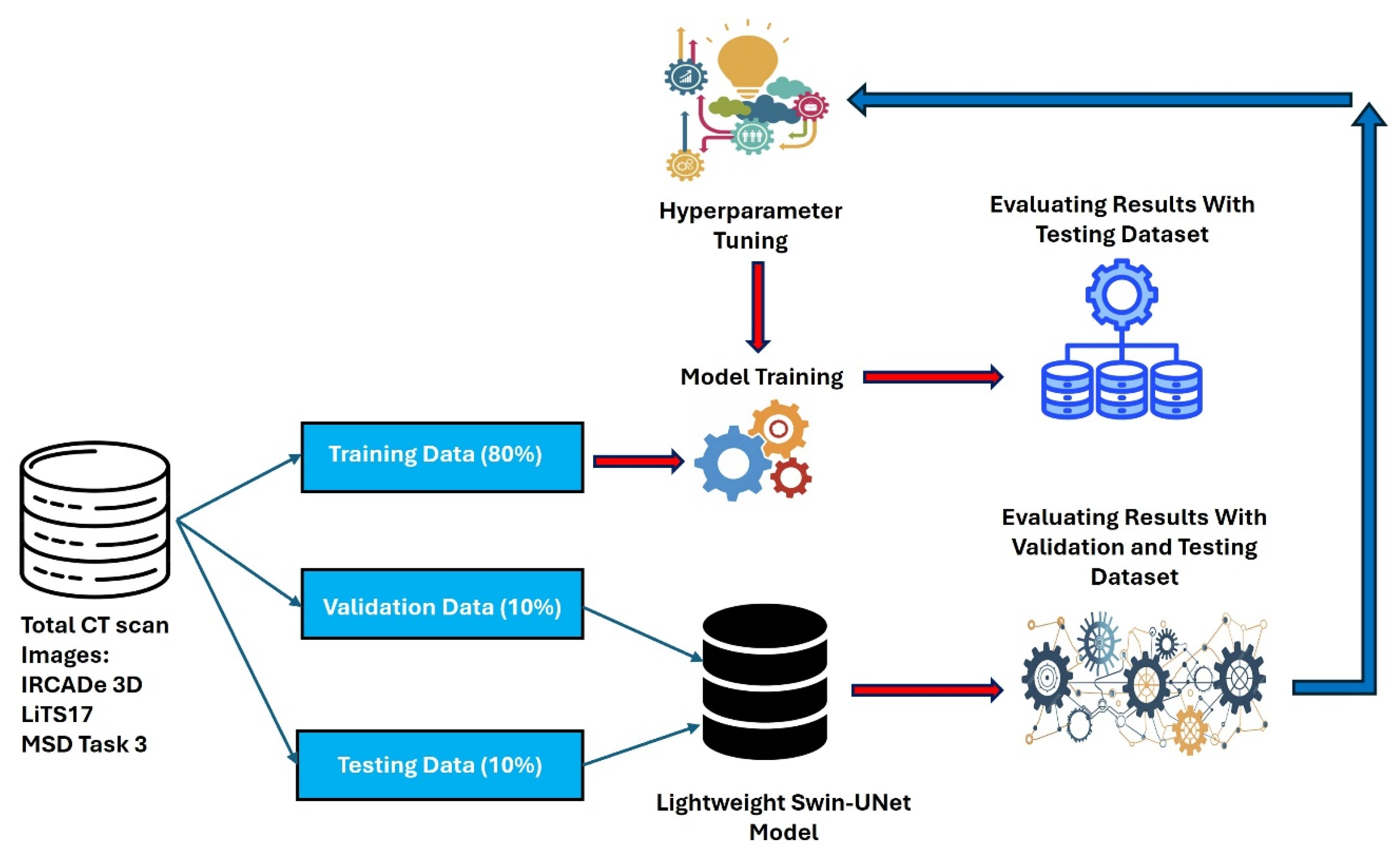

Figure 1 illustrates the workflow and component interactions.

The training dataset splits into training, validation, and test sets. The SAR algorithm iteratively reduces the objective function, enhancing accuracy while constraining model size. Post-optimization, the final model trains and computes results. Subsequent subsections elaborate on each component.

3.1. Swin-UNet and Hyperparameter Optimization

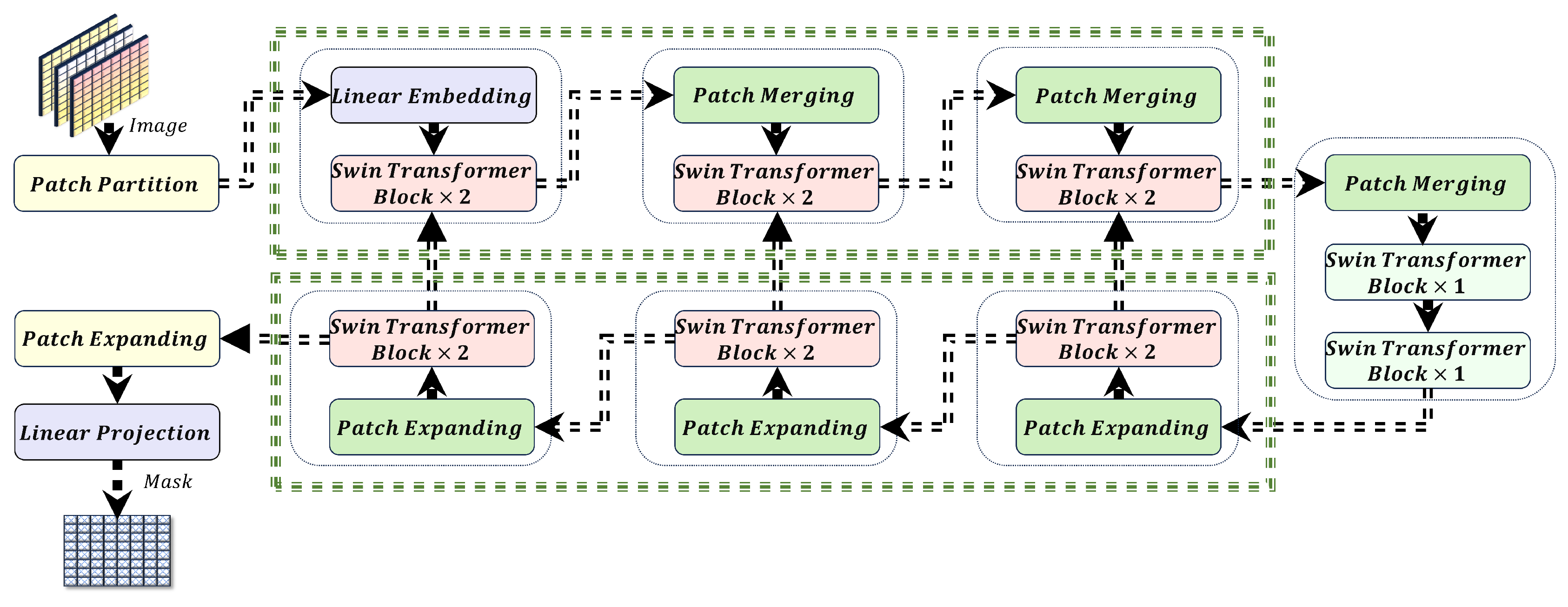

The Swin-UNet model integrates the hierarchical structure and shifted window attention mechanism of the Swin Transformer into the encoder-decoder framework of UNet as shown in the

Figure 2. This subsection overviews the Swin-UNet architecture and details the hyperparameters that significantly impact model performance and memory efficiency.

3.1.1. Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) in Swin-UNet

Swin-UNet employs a localized attention mechanism within non-overlapping windows, which differs from the global self-attention used in traditional Vision Transformers (ViTs). The attention mechanism for each window is computed as follows:

where,

Q,

K and

V are the query, key and value matrices, respectively and

is the dimensionality of the keys. This localized approach reduces the computational complexity compared to global attention mechanisms, making it more suitable for deployment on edge devices.

To facilitate spatial information exchange between windows, the Swin Transformer employs a shifted windowing mechanism, mathematically expressed as:

where,

represents the offset applied to window positions. This mechanism allows the model to capture inter-window dependencies, enhancing the overall segmentation accuracy of liver tumors.

3.1.2. Hyperparameter Space and Constraints

The efficiency and performance of the Swin-UNet model are influenced by several key hyperparameters, each subject to specific constraints.

Table 1 summarizes these hyperparameters along with their optimization ranges:

These hyperparameters control various aspects of the model, such as its depth, capacity and the size of the input data it processes. Optimizing these parameters within their specified ranges ensures a balance between the model’s segmentation accuracy and its memory footprint.

3.2. Search and Rescue (SAR) Algorithm

The Search and Rescue (SAR) algorithm [

39] solves optimization problems by balancing global exploration and local refinement. Inspired by rescue missions, SAR explores high-dimensional search spaces efficiently while focusing on promising regions, avoiding local minima. In machine learning, hyperparameter selection critically affects model performance. Algorithms like neural networks, decision trees, and support vector machines depend on hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, depth, regularization) for accuracy, training time, and generalization. SAR navigates large hyperparameter spaces efficiently, exploiting promising configurations while balancing performance and computational cost.

This study applies SAR to hyperparameter optimization in medical image segmentation for the first time. SAR tunes Swin-UNet for liver tumor segmentation, targeting high accuracy and computational efficiency.

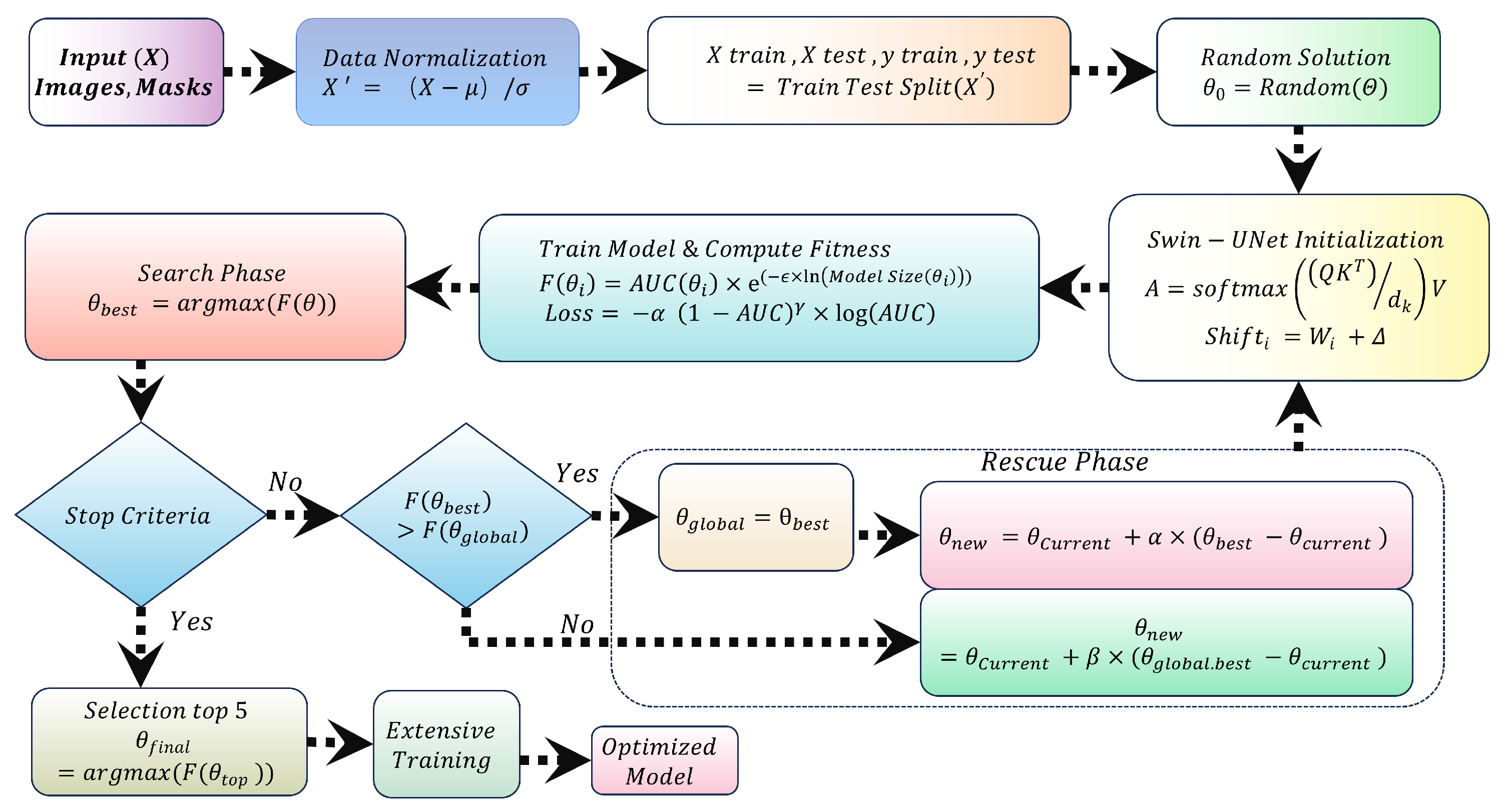

Figure 3 illustrates the SAR-based optimization workflow.

3.2.1. SAR Optimization Phases

SAR operates in three key phases: Initialization, Search and Rescue. These phases integrate both global search strategies and local refinement to ensure the algorithm explores the parameter space widely and then fine-tunes the promising regions. The following sections provide a detailed breakdown of each phase, followed by the mathematical formulations that guide the optimization process.

Initialization Phase:

The algorithm starts by generating an initial population of candidate solutions , where each solution represents a potential set of hyperparameters. These candidate solutions are randomly sampled within predefined bounds, which are set based on prior knowledge or expert intuition about the parameter space. The initialization phase plays a critical role in setting the starting point of the optimization and the quality of the initial candidates can significantly impact the subsequent search process.

The fitness of each candidate solution is evaluated using a fitness function that considers two key aspects: model performance (measured by AUC) and model size (which affects computational efficiency). The fitness function is formulated as follows:

where

represents a set of hyperparameters for candidate solution

i,

is a scaling factor that controls the influence of model size and AUC denotes the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. This formulation ensures that the fitness function rewards configurations that achieve high accuracy while keeping the model size manageable.

Search Phase:

Once the initial population is generated and evaluated, the SAR algorithm enters the Search phase. During this phase, each candidate solution is assessed based on its fitness score and the algorithm iteratively updates the positions of the solutions. The goal is to explore the search space and identify regions that are most promising, based on the fitness function. The search process is carried out using the following formula for updating the positions of each candidate:

where

is a learning rate parameter and

refers to the solution with the highest fitness score among the neighboring solutions. By updating the position of each candidate solution iteratively, SAR ensures that the search is directed towards regions of the search space that hold the potential for better performance.

Rescue Phase:

After the Search phase, the algorithm proceeds to the Rescue phase, where further refinement of the solutions is performed. During this phase, the candidate solutions are adjusted based on their proximity to the best solutions found during the Search phase. The goal of the Rescue phase is to focus the search on the most promising regions, fine-tuning the hyperparameters in order to improve model performance. To adjust the candidate solutions, the algorithm uses two strategies. First, if a suitable neighboring solution is found, the candidate solution is updated by moving it toward the best-performing neighbor. The adjustment is calculated as given in equation

10. If no suitable neighbors are found, the candidate solution is adjusted towards the globally best solution identified during the Search phase. The update for this adjustment is given by:

where

and

are scaling factors that control the magnitude of the adjustments. These strategies ensure that the algorithm refines the solutions towards the most optimal configurations while maintaining a balance between exploration and exploitation. The iterative process of the Rescue phase continues until the algorithm converges, yielding an optimal or near-optimal set of hyperparameters that balances both model performance (AUC) and model size, ensuring efficient training and accurate predictions.

3.3. AUC Focal Loss for Class Imbalance

Liver tumor segmentation faces class imbalance between tumor and healthy pixels. This work employs AUC focal loss to prioritize minority class learning by modulating easy and hard example contributions. The loss function focuses on difficult tumor pixels:

Here,

weights the minority class and

adjusts focus on hard examples. This work optimizes

and

to handle imbalance effectively. Combining SAR-based hyperparameter optimization with AUC focal loss enables efficient Swin-UNet models for accurate segmentation on edge devices. Algorithm 1 provides implementation details.

|

Algorithm 1 Search and Rescue (SAR) Algorithm for Swin-UNet Optimization |

- 1:

Initialize Swin-UNet Architecture - 2:

Input: Hyperparameters - Depth (D), Initial Filter Number (), Patch Size (P), - 3:

Number of Attention Heads (H), Window Size (W), MLP Size (M) - 4:

Output: Swin-UNet Model - 5:

Define the SAR Algorithm: - 6:

Input: Hyperparameter ranges - 7:

Output: Optimized hyperparameters - 8:

Initialization Phase: - 9:

Generate initial population of candidate solutions - 10:

For each candidate , randomly sample hyperparameters within the predefined ranges: - 11:

- 12:

Search Phase: - 13:

For each candidate , calculate Fitness using the following formula: - 14:

- 15:

Select candidates with highest fitness for further exploration - 16:

Rescue Phase: - 17:

For each selected candidate : - 18:

If a suitable neighbor is found: - 19:

Adjust towards neighbor: - 20:

- 21:

Else, adjust towards global best : - 22:

- 23:

AUC Focal Loss: - 24:

Define the AUC Focal Loss function: - 25:

- 26:

Train Swin-UNet: - 27:

Train the Swin-UNet model using the optimized hyperparameters and AUC focal loss. - 28:

Output: Final optimized Swin-UNet model |

3.4. Optimality Analysis of the Objective Function with SAR

The objective function used in this study is given by equation

9. Where

is a set of hyperparameters that includes both discrete and continuous variables. This function is designed to balance model accuracy (AUC) with model size, where

is a positive constant that controls the trade-off. Given that

includes a combination of discrete and continuous variables, the optimization process operates in a mixed space. Thus, traditional convexity concepts apply only to the continuous subspace.

Convexity in the Continuous Subspace:

For a fixed discrete setting of

, consider the continuous component

. The objective function within this continuous subspace can be simplified as:

where

and

.

The convexity analysis in this continuous domain reveals that the Hessian matrix

H of this function is given by:

The determinant of this Hessian matrix is:

Since and , . However, since , the function is not strictly convex but exhibits convexity in a weaker sense. This suggests that the function has flat regions in the continuous domain, leading to multiple suboptimal solutions rather than a unique global optimum.

Optimality in the Discrete Space:

In the context of discrete variables, traditional convexity does not directly apply. However, the concept of piecewise convexity and discrete optimization can be leveraged. For the discrete components of

, the objective function can be viewed as a set of piecewise convex functions:

where each

represents the objective function in the continuous subspace for a fixed discrete setting

j. Each function

is convex, as previously proven.

Although the discrete space lacks a gradient, the SAR algorithm explores it by evaluating a finite set of configurations. SAR employs a combination of local search and global adjustment strategies to navigate this space, effectively finding a configuration that minimizes the objective function.

Suboptimality and Convergence with SAR:

SAR ensures that the search process converges to a suboptimal solution in the mixed space. Given that the continuous subspace is convex for fixed discrete settings, SAR optimizes locally in these regions as given by equation

10. In cases where discrete changes are necessary, SAR adjusts the discrete variables, re-evaluating the objective function. This iterative process guarantees convergence to a suboptimal or near-optimal solution due to the following:

Local Optimality in Continuous Subspace Each continuous optimization step finds a locally optimal solution within the convex region.

Global Exploration in Discrete Space By systematically exploring different discrete configurations, SAR ensures broad coverage of the search space.

Thus, while strict convexity in the discrete space is not mathematically provable, the combination of convexity in the continuous space and SAR’s exploration mechanism ensures effective navigation towards at least a suboptimal point.

4. Results and Discussion

This section discusses the results and comparisons for the proposed scheme. It begins with an overview of the datasets and comparison metrics used to evaluate the scheme. Following this, the optimal hyperparameters are presented, along with an analysis of the model’s performance on various datasets. Finally, the section compares the proposed scheme with recently introduced schemes that have used the same datasets.

4.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

This study uses three datasets for liver tumor segmentation: the LiTS17 dataset, the IRCADe 3D dataset and the MSD Task 3 dataset. The LiTS17 dataset contains 131 images with labels for liver tumor segmentation. These images provide quality data for training and evaluating models. The IRCADe 3D dataset includes 20 images of patients with liver tumors. These images offer layers of CT scans that show liver and nearby structures. Differences in slice thickness and tumor features make this dataset useful for testing models under practical conditions. The MSD Task 3 dataset has 130 images often used for segmentation tasks in medical imaging. These images show a range of liver tumor cases, helping evaluate models in many scenarios. The datasets split into training, validation and test sets in 80%, 10% and 10% proportions, as shown in

Table 2.

Preprocessing helps expand the training dataset and improve model performance. Transformations like rotation, flipping, scaling, gamma correction and logarithmic scaling apply to training images while keeping segmentation masks aligned. These transformations create new versions of images to make models learn from more examples.

Rotation randomly changes image angles within

. The transformation for rotation is:

where

are original coordinates and

are rotated coordinates. This transformation applies to both images and masks to keep them aligned.

Flipping creates variations by horizontally or vertically flipping images. A horizontal flip uses:

Scaling simulates zooming by randomly resizing images by

. Scaling uses the formula:

where

s is the scale factor. Gamma correction adjusts brightness and contrast to help models detect regions under different lighting. Gamma correction follows:

where

I is the intensity and

c and

are constants. Logarithmic scaling improves visibility in areas with low contrast. This uses:

where

I is the intensity and

is a constant. Both gamma and logarithmic scaling enhance features but leave masks unchanged. These steps increase the variety of the data sets and help the models generalize better to new data.

4.2. Experimental Setup

This work optimizes the Swin-UNet model for liver tumor segmentation to improve accuracy and computational efficiency. The Search and Rescue algorithm tunes hyperparameters using an Nvidia 3090 Ti GPU, accelerating the search process. This work deploys the optimized model on a Jetson Nano to evaluate edge-device performance under memory constraints. The Jetson Nano provides a practical balance for real-time medical image segmentation. All models use a learning rate of 0.0001, empirically shown to balance convergence speed and stability. Training runs for 2000 epochs with early stopping (patience: 10 epochs) to prevent overfitting. A batch size of 64 balances memory usage and convergence. The Adam optimizer enhances training through adaptive learning rates and momentum. AUC focal loss addresses class imbalance by prioritizing challenging tumor regions. Experiments demonstrate that the optimized model achieves high segmentation accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency on edge devices like the Jetson Nano.

Table 3.

Summary of Model Hyperparameters and Setup.

Table 3.

Summary of Model Hyperparameters and Setup.

| Hyperparameter |

Value |

| Learning Rate |

0.0001 |

| Epochs |

2000 |

| Batch Size |

64 |

| Optimizer |

Adam |

| Patience (Early Stopping) |

10 epochs |

| Device for Optimization |

Nvidia 3090 Ti |

| Device for Deployment |

Jetson Nano |

4.3. Comparison Metrics

This section introduces metrics to evaluate segmentation algorithms, assessing model performance in distinguishing positive and negative cases and spatial accuracy against ground truth. Metrics fall into two main categories, classification and overlap-based matrics. Classification metrics evaluate model classification performance. Precision represents the proportion of true positives among positive predictions:

Recall indicates the proportion of true positives identified:

The F1 score combines precision and recall through harmonic mean:

Accuracy measures overall correctness:

Specificity quantifies true negative identification:

Overlap-based metrics assess spatial accuracy between predicted (

P) and ground truth (

G) segmentations. The Dice Similarity Coefficient measures overlap:

where

and

denote pixel counts in predicted and ground truth regions, and

counts overlapping pixels. Volume Overlap Error (VOE) computes union-based error:

Relative Volume Difference (RVD) quantifies volume discrepancy:

where

and

represent segmented and ground truth volumes. Lower VOE and RVD indicate better spatial and volumetric accuracy.

4.4. Hyperparameter Optimization and Model Performance

This work evaluates hyperparameter settings for optimizing the Swin-UNet model using the IRCADe 3D dataset. Four experiments analyze the trade-offs between model complexity, segmentation performance, and size: one unoptimized baseline and three configurations with distinct

values (0.0486, 0.1172, 0.2344).

Table 4 summarizes the parameters.

The unoptimized model uses 128 filters and patch size 4. Optimized configurations adjust these parameters: minimizes model size through reduced filters and simpler attention mechanisms; balances complexity and performance; maximizes AUC via larger filters and complex attention. This work enables selection of based on deployment requirements for memory efficiency versus segmentation accuracy.

4.5. Model Performance on Liver Tumor Segmentation

This work assesses segmentation performance across 3DIRCADb, LiTS, and MSD Task03 datasets using accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, Dice score, VOE, and RVD metrics. It identifies optimal

values for each dataset by analyzing model size-performance trade-offs.

Table 5 summarizes results, highlighting configurations that balance compression and accuracy for specific clinical applications.

4.5.1. 3DIRCADb Dataset Analysis

The unoptimized model on the 3DIRCADb dataset achieves a high Dice score of 83.40% and an RVD of 0.23%. Optimizing the model with =0.2344 reduces the model size by 80.25% to 64.16 MB, with a slight increase in Dice to 94.78% and a marginal reduction in RVD to 0.23%. This shows that a smaller model size can be maintained without a significant degradation in performance, even with substantial model compression. Further reducing to 0.0486 yields a smaller model size of 17.22 MB but leads to a marked drop in Dice to 76.44%, despite achieving a recall of 83.29%. This highlights the trade-off between model size and segmentation performance, where a smaller model may sacrifice precision in favor of capturing a broader range of true positives, as reflected in the inflated RVD.

In terms of liver tumor segmentation, the model’s recall increases as decreases, suggesting better sensitivity to true positives. However, this comes at the cost of a reduced Dice score, indicating poorer localization of tumor boundaries. These observations align with the concept that recall improvement does not necessarily guarantee better overall model performance, as it may increase false positives and degrade precision, leading to higher volume estimation errors (RVD).

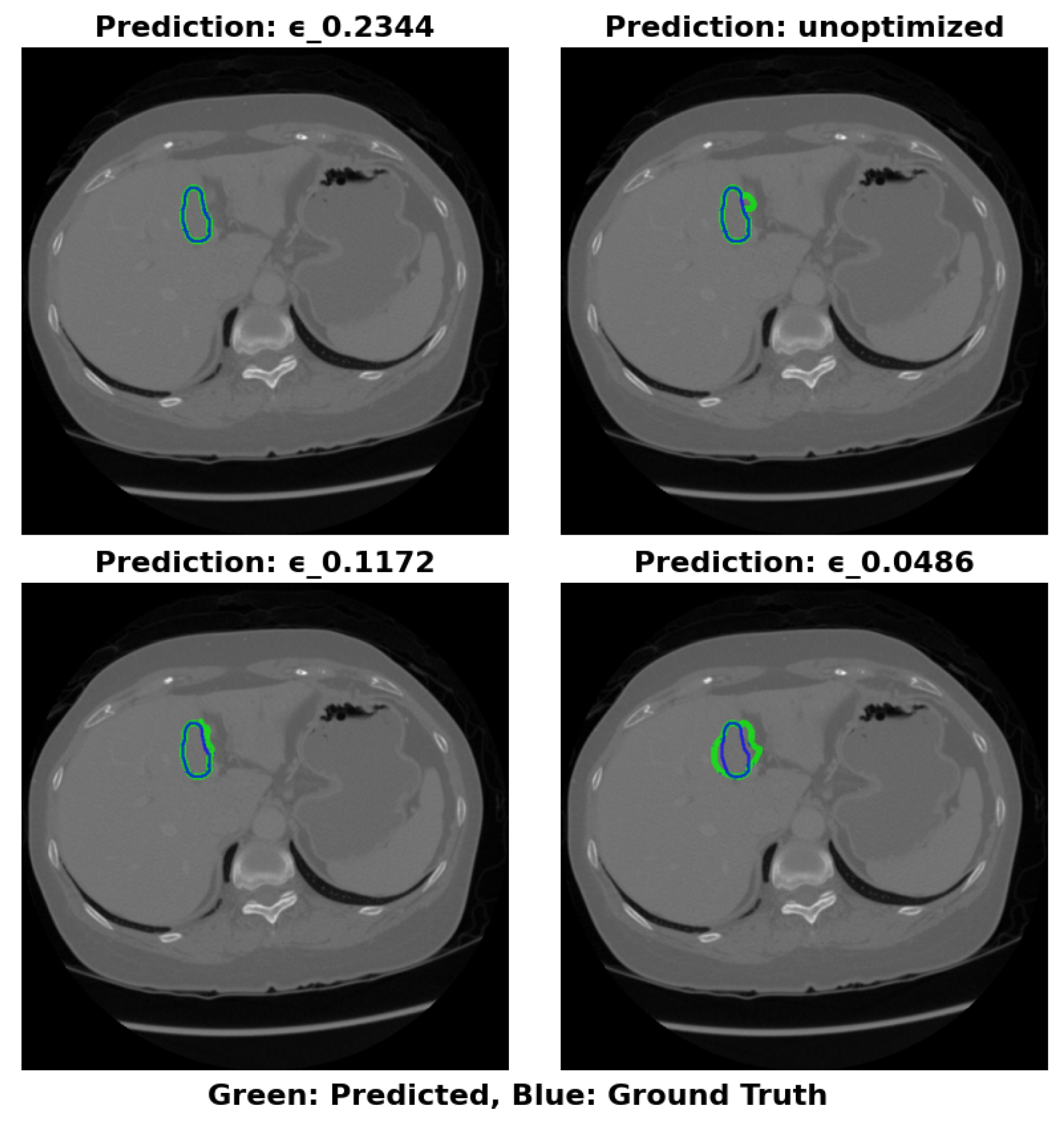

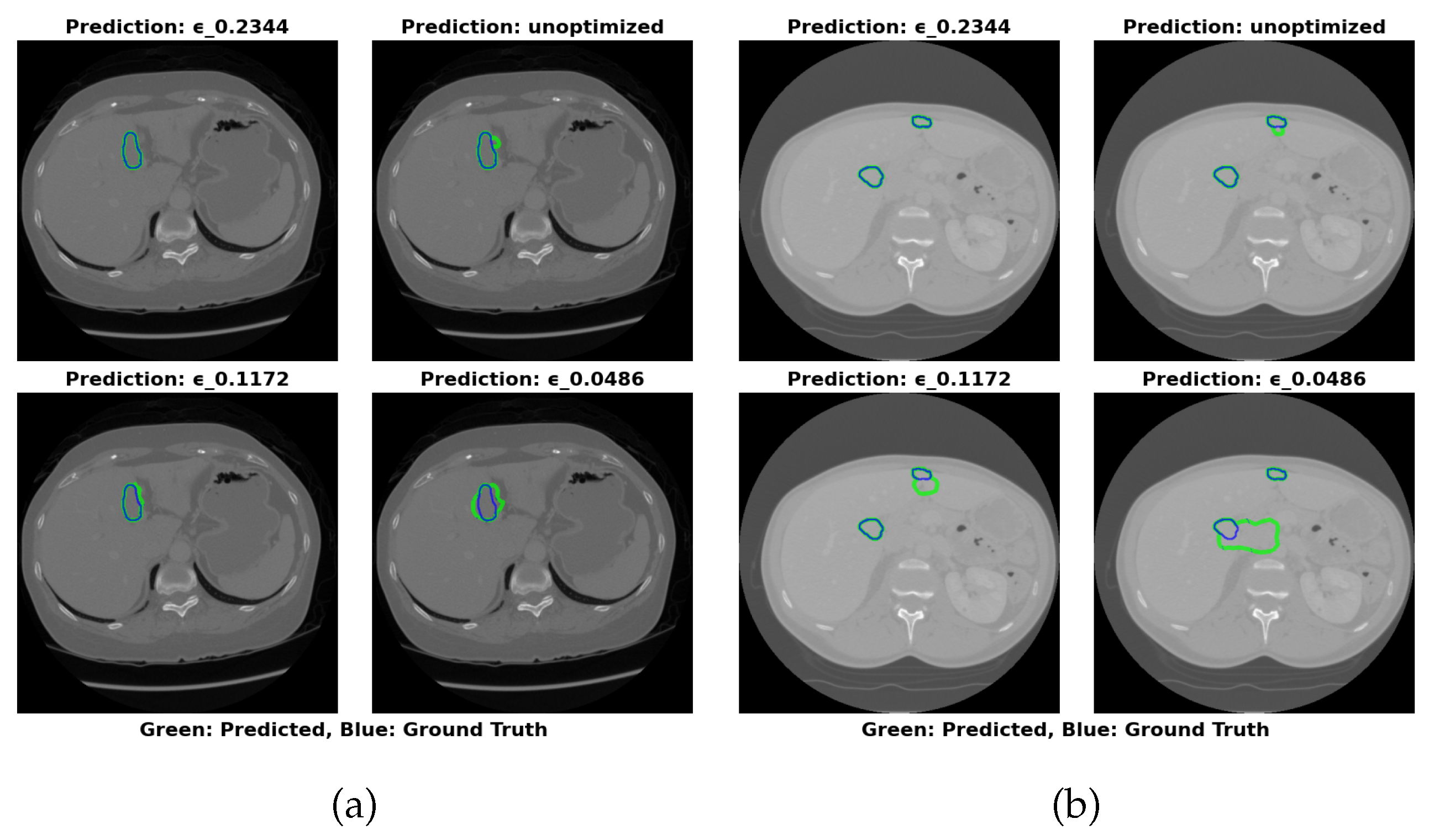

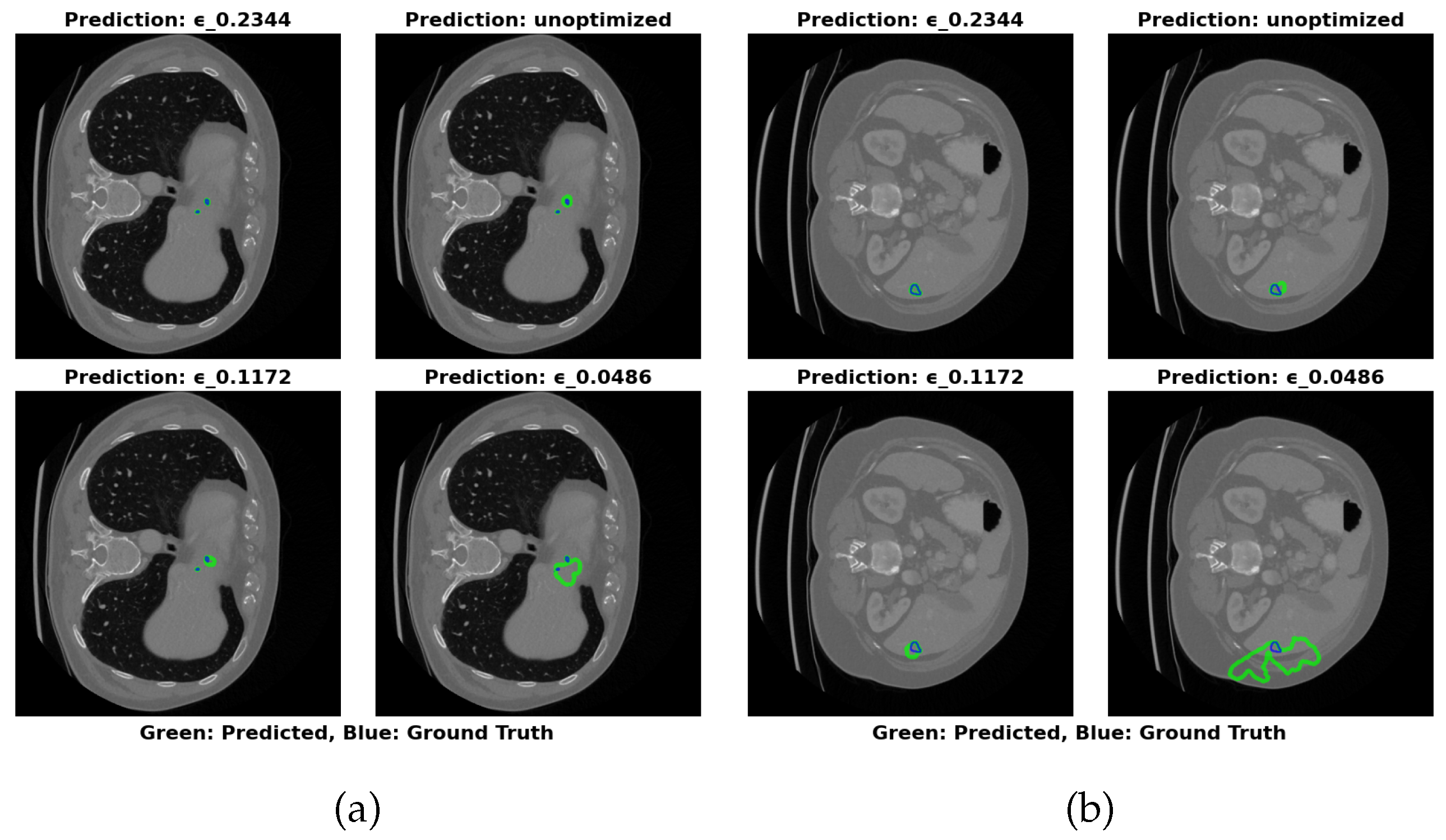

The visual segmentation results presented in

Figure 4 support these findings. The configuration with

=0.2344 exhibits the most accurate tumor boundary predictions, with minimal deviation from the true boundaries. In contrast, the unoptimized model, though effective, demonstrates less precise boundary delineation, particularly in complex tumor regions. These visual results confirm the quantitative findings, reinforcing that optimizing

significantly enhances segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency.

4.5.2. LiTS Dataset Analysis

For the LiTS dataset, the unoptimized model achieves a high Dice score of 87.53% and an RVD of 2.89%. After optimizing to 0.2344, the model size is reduced to 64.16 MB with a slight decrease in Dice to 89.06% and an improvement in RVD to 2.51%. This demonstrates that optimizing the model with a smaller leads to a good balance between performance and model size, with minimal sacrifice in segmentation accuracy. However, further reduction of to 0.0486 significantly reduces the model size to 17.22 MB but causes a large drop in Dice to 79.98% and a marked increase in RVD to 16.8%, indicating that excessive model compression leads to a significant performance trade-off.

As with the 3DIRCADb dataset, reducing

enhances recall but at the expense of precision, resulting in larger errors in volume estimation. The model becomes more sensitive to liver tumor pixels, but this increased sensitivity also leads to a greater number of false positives.

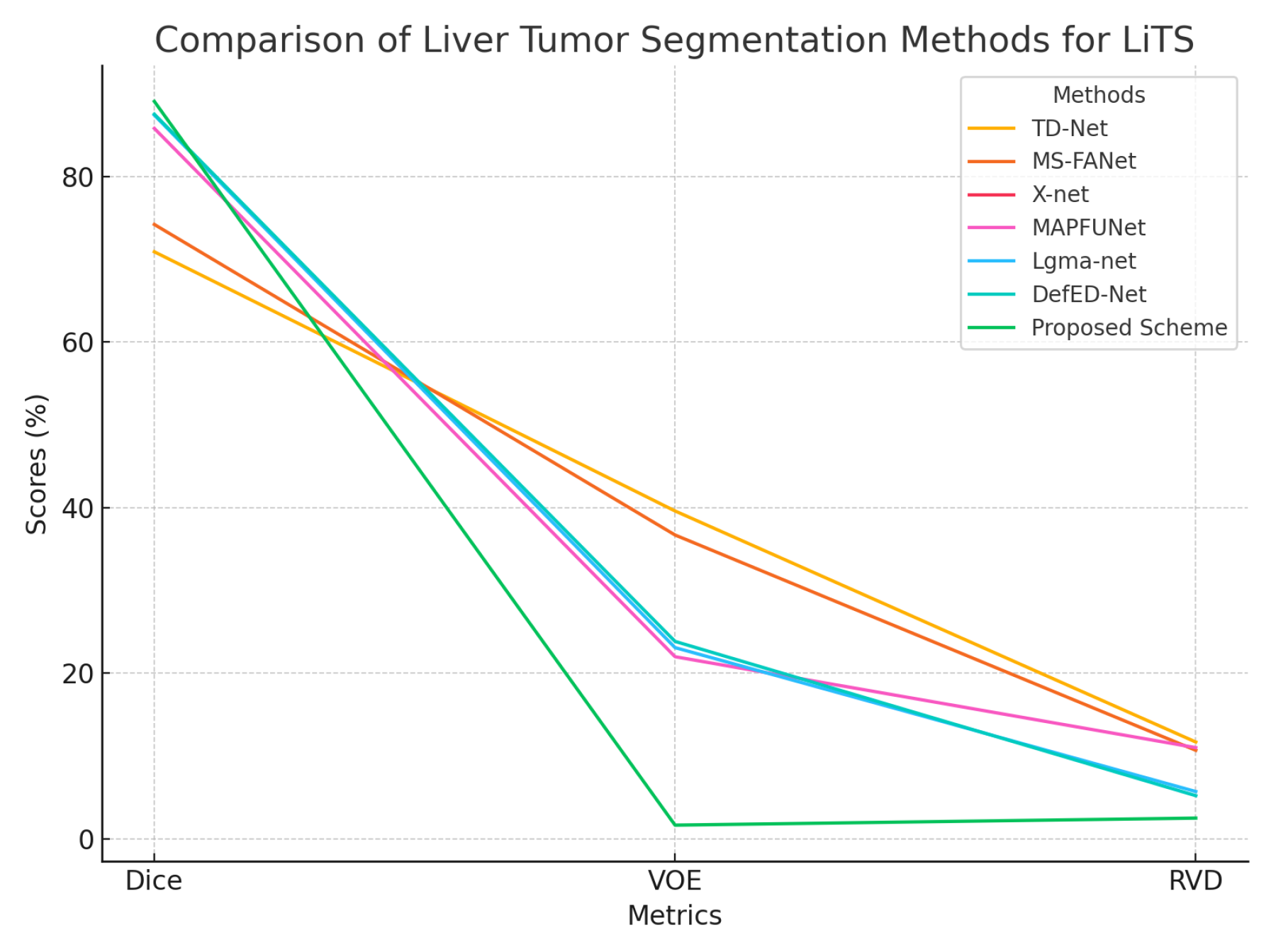

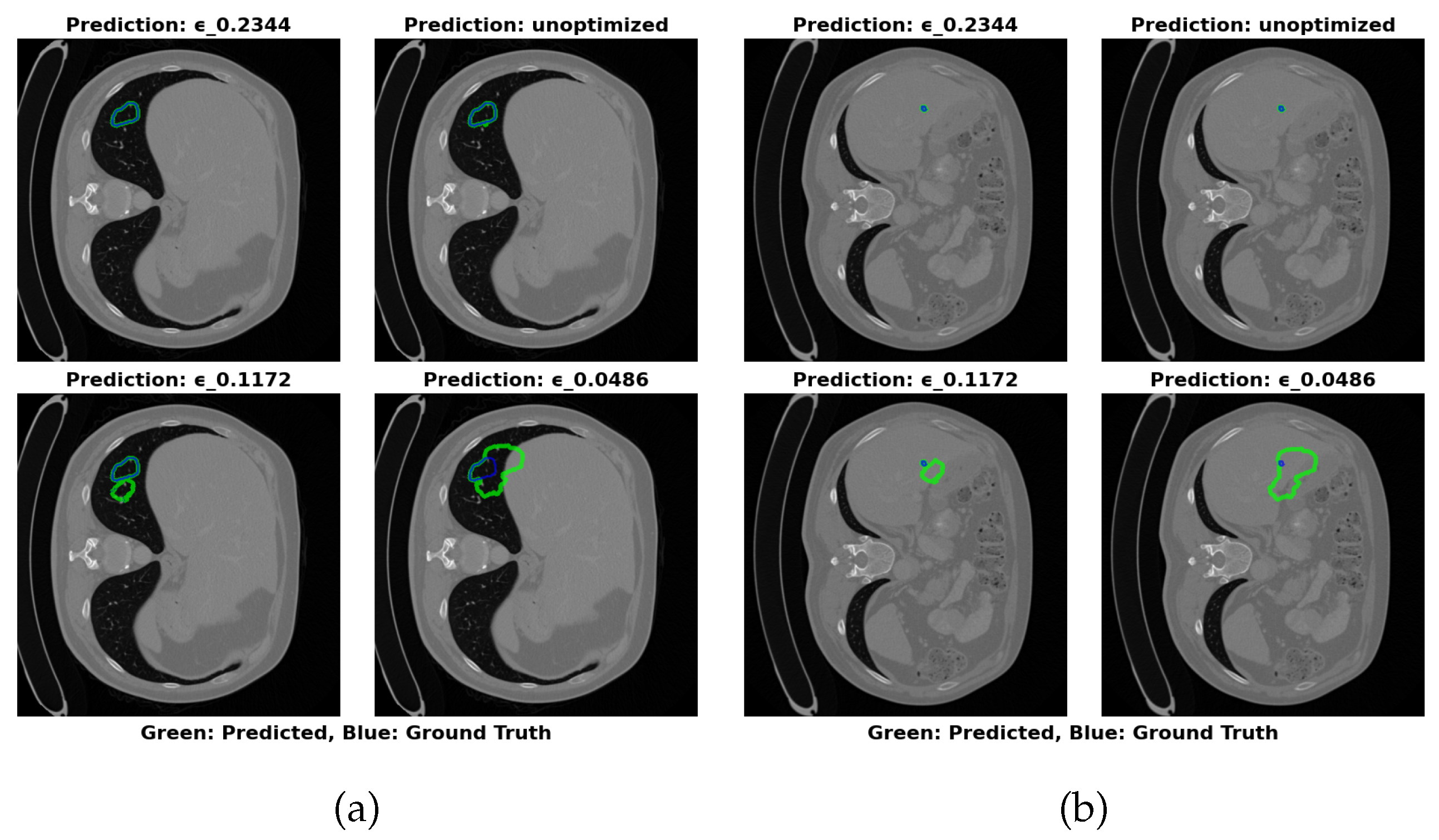

Figure 5 shows that the optimal configuration at

=0.2344 offers the most accurate segmentation boundaries, with slight deviations from the true tumor boundaries. The lower

configuration (0.0486) results in larger inaccuracies in boundary delineation, supporting the need for careful selection of

to balance performance and model size.

4.5.3. MSD Task03 Dataset Analysis

On the MSD Task03 dataset, the unoptimized model achieves a Dice score of 87.58% and an RVD of 19.33%. After optimizing to 0.2344, the model size is reduced to 64.16 MB, with an improvement in Dice to 88.95% and a significant reduction in RVD to 4.63%. This indicates that =0.2344 strikes the optimal balance between model size and performance, offering enhanced tumor segmentation while maintaining a compact model size. However, for the extreme compression setting of =0.0486, the model size is reduced to 17.22 MB, but the Dice score drops to 83.63% and RVD increases drastically to 1233.04%, showing the detrimental effects of extreme compression on model performance.

The recall shows improvement as

decreases, but this is not accompanied by better performance in terms of precision, as indicated by the reduced Dice and the inflated RVD. The increased false positives lead to higher volume estimation errors, particularly when

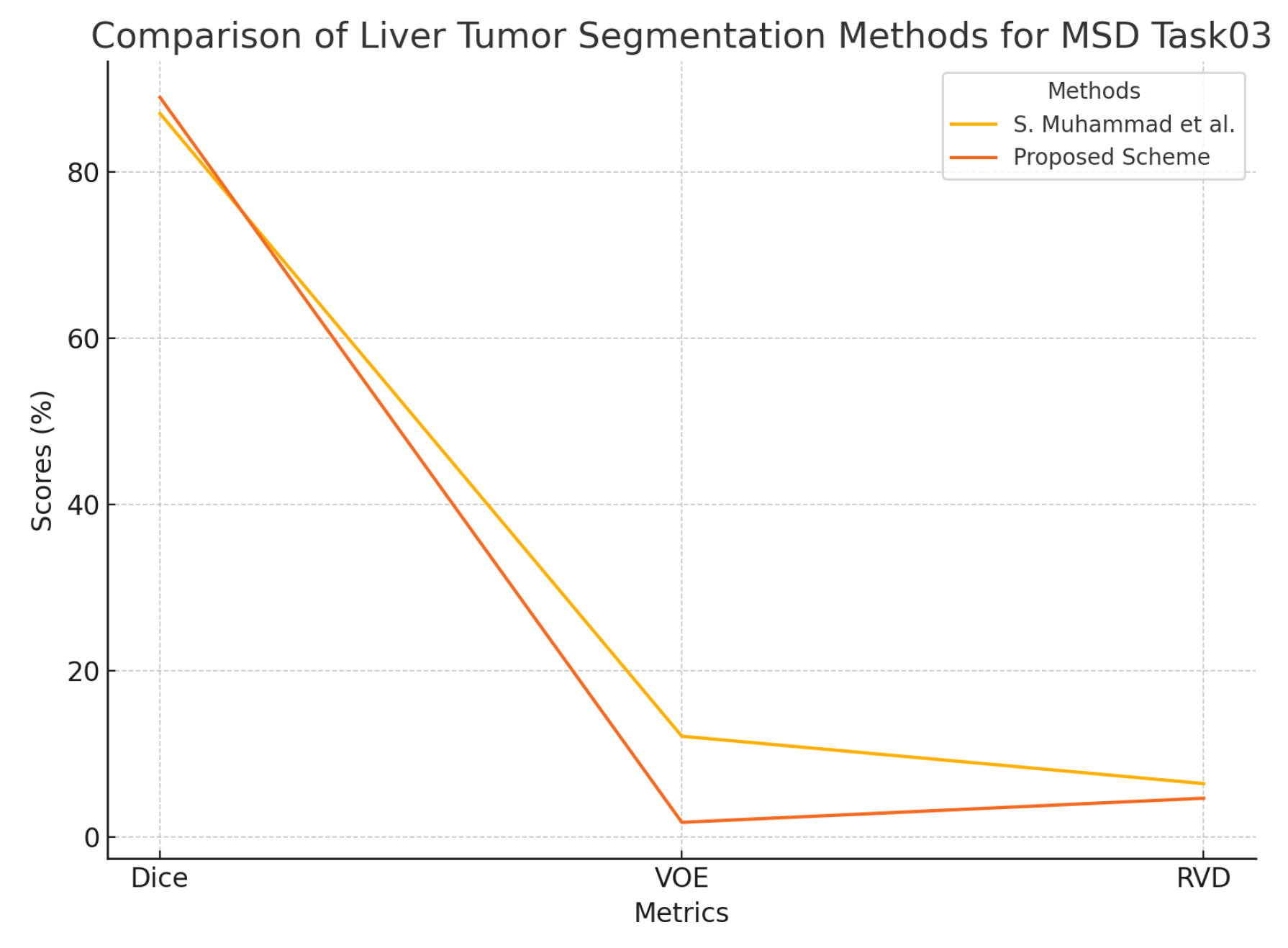

is set to the lowest value. Visual results in

Figure 6 further demonstrate the superior segmentation performance of the

=0.2344 configuration, which closely matches the true tumor boundaries. The unoptimized model, while still effective, demonstrates less accurate boundary delineation, underscoring the advantage of optimizing

for both segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency.

4.5.4. Optimal Configuration Selection

The parameter plays a critical role in adjusting the size-performance trade-off for liver tumor segmentation. The unoptimized configuration offers maximal performance with high Dice and specificity but requires substantial storage. The =0.2344 configuration strikes an optimal balance, offering good performance with a significant reduction in size, maintaining a Dice score above 83% and RVD less than 25% for all datasets. Meanwhile, the =0.0486 configuration provides maximum compression, reducing the model size dramatically, but at the expense of substantial degradation in both Dice and RVD, highlighting the trade-offs involved in model compression.

In liver tumor pixel segmentation, precision-recall balance is paramount. A high recall value indicates good detection of true positives, but it may also increase false positives, resulting in decreased precision and inflated volume estimation errors. As decreases, the model’s recall increases, but this comes at the expense of precision, as seen in the drop in Dice and the increase in RVD. This demonstrates the importance of achieving a balance between recall and precision for accurate liver volume estimation.

Maximal Compression: =0.0486 (17.22 MB) for storage-constrained deployments.

Optimal Balance: =0.2344 (64.16 MB) maintains greater than 83% Dice with RVD less than 25% across datasets.

Maximal Accuracy: Unoptimized (324.91 MB) for non-constrained environments.

The =0.2344 configuration reduces model size by 80.25% while maintaining average Dice scores within 3.25% of the baseline across all datasets. This 64.16 MB model provides clinically acceptable RVD values (less than 5% for LiTS and MSD Task03) while requiring only 19.8% of the original storage capacity.

4.6. Optimized Model Performance Comparison with SOTA

To evaluate the performance of the proposed Swin-UNet scheme, we compare it against several state-of-the-art liver tumor segmentation methods across three datasets: 3DIRCADb, LiTS and MSD Task03.

Table 6 summarizes the results using three metrics: Dice Coefficient (%), Volume Overlap Error (VOE %) and Relative Volume Difference (RVD %).

For the 3DIRCADb dataset, the proposed scheme achieves a Dice score of 94.78%, significantly surpassing existing methods, such as DefED-Net (66.2%), X-net (69.1%) and TD-Net (68.2%). It also outperforms MS-FANet (78.0%), Lgma-net (83.2%) and MAPFUNet (85.9%). The proposed model achieves the highest Dice score among the methods compared, demonstrating superior segmentation accuracy. Additionally, the proposed scheme achieves a remarkably low VOE of 7.83%, which is a notable improvement over all compared methods, including MAPFUNet (23.7%) and MS-FANet (31.3%). The RVD of 0.23% is also the best among all methods, closely matching MS-UNet (0.22%) and MAPFUNet (0.22%) and providing an exceptional level of volume estimation accuracy.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of segmentation results on the 3DIRCADb dataset.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of segmentation results on the 3DIRCADb dataset.

On the LiTS dataset, the proposed scheme achieves a Dice score of 89.06%, which is substantially higher than other state-of-the-art methods, including DefED-Net (87.52%) and MAPFUNet (85.8%). This represents a significant improvement in segmentation accuracy. The VOE is drastically reduced to 1.66%, outperforming the next best value of 22.0% achieved by MAPFUNet and is much lower than values observed in other methods like TD-Net (39.6%) and MS-FANet (36.7%). Similarly, the RVD of 2.51% represents a considerable improvement over previous methods such as DefED-Net (5.22%) and Lgma-net (5.72%). These results demonstrate that the proposed Swin-UNet achieves highly accurate segmentation with minimal overlap and volume estimation errors.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of segmentation results on the LiTS dataset.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of segmentation results on the LiTS dataset.

For the MSD Task03 dataset, the proposed Swin-UNet achieves an impressive Dice score of 88.95%, surpassing the existing method by S. Muhammad et al. (87.0%). The VOE is reduced to 1.73%, compared to 12.09% for Muhammad et al., demonstrating a substantial improvement in segmentation precision. The RVD of 4.63% also shows a noticeable improvement over the previous result of 6.39%, further reinforcing the accuracy of the proposed model.

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of segmentation results on the MSD Task03 dataset.

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of segmentation results on the MSD Task03 dataset.

The proposed Swin-UNet model establishes new state-of-the-art results on the LiTS and MSD Task03 datasets, excelling in all performance metrics. For the 3DIRCADb dataset, it delivers the lowest VOE while maintaining competitive Dice and RVD values. These results highlight the proposed model’s ability to segment liver tumors with high accuracy, minimal overlap errors and precise volume estimation, establishing it as a highly effective solution for medical imaging tasks.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, W.M.I.; methodology, W.M.I.; software, W.M.I. and L.A.; validation, W.M.I., S.S.H. and M.ELA.; formal analysis, W.M.I., S.S.H. and L.A.; investigation, W.M.I., S.S. and Y.Q.Z.; data curation, W.M.I. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.M.I. and Y.Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.M.I., Y.Q.Z., S.S.H., L.A. and M.ELA.; visualization, W.M.I.; supervision, Y.Q.Z. and S.S.H.; project administration, Y.Q.Z.; funding acquisition, L.A. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.