Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Imaging is one of the strongest and fastest growing sectors of diagnostic medicine; nevertheless, the incorporation of large-scale medical image datasets across different hospitals is still a challenge due to regulatory, privacy, and infrastructure issues. In this paper, we propose a framework for the application of federated machine learning in radiology and explain how it can be implemented in practice using the Chest X-Ray14 dataset from NIH. We explain how to achieve privacy-preserving data collection and handling in real-world scenarios such as HIPAA and GDPR, secure communication, heterogeneous data preprocessing, and container-based orchestration. The federated approach produces fairly small, but still clinically significant improvements in performance (1.5–2.0% absolute increase in AUC) compared to single-node training and thus proves the feasibility of distributed machine learning in sensitive healthcare environments. We further elaborate on the resource requirements and regulatory constraints and also provide some directions for the future growth of federated radiological analysis so that performance is not overemphasized and the confidentiality of patients is not compromised.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Distributed Learning in Healthcare

2.2. Federated Learning Paradigm

2.3. Radiology-Specific Applications

- Sheller et al. proposed FL for brain tumor segmentation across several hospitals, with performance comparable to centralized training [9].

- Chang et al. tested distributed CNNs on multi-institutional CT scans and demonstrated feasibility [6].

- Zhang et al. examined federated domain adaptation with unsupervised methods for multi-hospital MRI data [28].

2.4. NIH Chest X-ray14

3. Methodology

3.1. Use Case Definition

3.2. Federated Architecture

3.3. Data Preprocessing

- Image Rescaling: Downsample from 1024×1024 (or 2048×2048) to 512×512.

- Normalization: Pixel intensities scaled to [0, 1].

- Augmentation: Random flips, rotations (), and crops [20].

- Label Encoding: Multi-label classification uses a sigmoid per pathology, while binary pneumonia detection uses one sigmoid unit.

3.4. Model Architecture

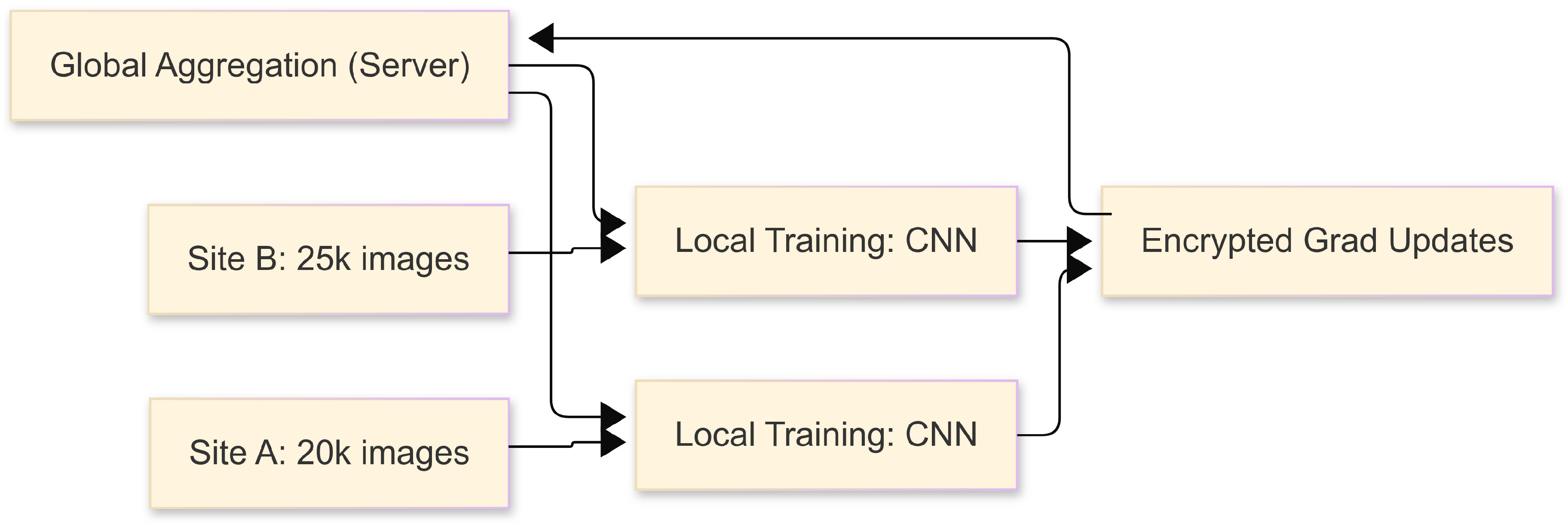

3.5. Federated Averaging Protocol

- Initialization: Server broadcasts global model .

- Local Updates: Each site trains for E epochs, yielding .

- Aggregation:

- Broadcast: Server sends back for the next round.

3.6. Evaluation

4. Implementation Details

4.1. Hardware and Infrastructure

4.2. Software Stack

4.3. Sample Dockerfile

4.4. Training Workflow

- Global Initialization: Server starts with a randomly initialized or pretrained ResNet-50 / DenseNet-121.

- Local Training: Each site runs 2–5 epochs, logs loss and metrics.

- Secure Update: Encrypted weight diffs are sent to the server.

- Aggregation and Broadcast: Server applies FedAvg, returns updated model.

- Monitoring: Track real-time curves (loss, AUC) with TensorBoard or Weights&Biases [36].

- Convergence: After 20–30 communication rounds, evaluate on a central test set.

4.5. Regulatory and Security Compliance

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Dataset Splits

- Site A: 20,000 images

- Site B: 25,000 images

- Site C: 15,000 images

- Site D: 30,000 images

- Site E: 22,000 images

5.2. Performance Metrics

5.2.1. Multi-Label (14 Diseases)

| Config. | AUC (%) | Acc. (%) | F1 | Prec. (%) | Rec. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Node Baseline | 81.2 ± 0.5 | 78.9 ± 0.4 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 80.1 ± 0.5 | 74.6 ± 0.6 |

| Centralized Multi-Node | 82.5 ± 0.4 | 80.2 ± 0.5 | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 81.3 ± 0.4 | 75.9 ± 0.5 |

| Federated Multi-Node | 83.7 ± 0.6 | 81.1 ± 0.3 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 82.1 ± 0.5 | 76.5 ± 0.4 |

5.2.2. Binary Pneumonia Detection

| Config. | AUC (%) | Acc. (%) | Sens. (%) | Spec. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Node Baseline | 86.9 ± 0.3 | 85.2 ± 0.5 | 88.3 ± 0.4 | 84.1 ± 0.6 |

| Centralized Multi-Node | 88.1 ± 0.4 | 86.4 ± 0.4 | 89.2 ± 0.5 | 85.0 ± 0.5 |

| Federated Multi-Node | 89.4 ± 0.5 | 87.1 ± 0.6 | 90.1 ± 0.6 | 85.8 ± 0.5 |

5.3. Training Efficiency and Bandwidth

| Config. | Time/Epoch (hrs) | Comm. Overhead (GB) |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Node Baseline | 8.5 ± 0.4 | N/A |

| Centralized Multi-Node | 5.2 ± 0.3 | ∼150 |

| Federated Multi-Node | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 10–20 |

5.4. Privacy Sensitivity Analysis

5.5. Qualitative Evaluation

6. Discussion

6.1. Clinical Relevance of Modest Gains

6.2. Implementation Complexities

6.3. Limitations

- Variable Data Quality: Labeling inconsistencies or protocol changes degrade performance.

- No Advanced Domain Adaptation: We did not employ adversarial domain adaptation [28].

6.4. Future Directions

- Real-Time Inference: On-device or edge-based pipelines for immediate feedback [36].

7. Conclusion

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Ablation Studies

Appendix A.2. Code Snippets

Appendix A.3. Extended Statistical Analysis

- We computed 95% confidence intervals for AUC via bootstrapping.

- A paired t-test shows p < 0.05 for single-node vs. federated multi-node in pneumonia detection.

References

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks,” Commun. ACM, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 84–90, 2017. [CrossRef]

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, and T. Brox, “U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation,” in MICCAI, pp. 234–241, 2015. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Dept. of HHS, “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),” 1996, Available: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/index.html.

- European Parliament, “General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),” 2018, Available: https://gdpr-info.eu/.

- Q. Yang et al., “Federated machine learning: Concept and applications,” ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 12:1–12:19, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Chang et al., “Distributed deep learning networks among institutions for medical imaging,” J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 221–231, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. McMahan et al., “Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data,” in Proc. AISTATS, pp. 1273–1282, 2017.

- P. Kairouz et al., “Advances and open problems in federated learning,” Found. Trends Mach. Learn., 2021.

- M. J. Sheller et al., “Federated learning in medicine: Facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data,” Sci. Rep., vol. 10, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Rubin et al., “Regulatory affairs of medical devices and software-based technologies,” J. Digit. Imaging, vol. 31, pp. 287–298, 2018.

- J. Dean and S. Ghemawat, “MapReduce: Simplified data processing on large clusters,” Commun. ACM, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 107–113, 2008. [CrossRef]

- B. Burns et al., “Kubernetes: Up and running,” O’Reilly Media, 2019.

- Y. Zhang et al., “Collaborative unsupervised domain adaptation for medical image diagnosis,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 3543–3554, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Gulshan et al., “Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs,” JAMA, vol. 316, no. 22, pp. 2402–2410, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar et al., “CheXNet: Radiologist-level pneumonia detection on chest x-rays with deep learning,” arXiv:1711.05225, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang et al., “ChestX-ray8: Hospital-scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases,” in CVPR, pp. 3462–3471, 2017.

- M. Zaharia et al., “Spark: Cluster computing with working sets,” in USENIX HotCloud, 2010.

- J. Leskovec, A. Rajaraman, and J. D. Ullman, “Mining of massive datasets,” Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- A. Holzinger et al., “Big data in medical informatics: Regulatory and ethical challenges,” Methods Inf. Med., vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 512–524, 2015.

- K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition,” arXiv:1409.1556, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Konečný et al., “Federated learning: Strategies for improving communication efficiency,” arXiv:1610.05492, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Brendan McMahan and D. Ramage, “Federated learning: Collaborative machine learning without centralized training data,” Google AI Blog, 2017.

- Y. Lindell and B. Pinkas, “Secure multiparty computation for privacy-preserving data mining,” J. Priv. Confid., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 59–98, 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Dwork et al., “Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis,” in TCC, pp. 265–284, 2006.

- M. Abadi et al., “Deep learning with differential privacy,” in ACM SIGSAC, pp. 308–318, 2016.

- C. Gentry, “Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices,” in STOC, pp. 169–178, 2009.

- A. Bonawitz et al., “Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning,” in ACM CCS, pp. 1175–1191, 2017.

- T. Maruyama and Y. Matsushita, “Federated domain adaptation with asymmetrically-relaxed distribution alignment,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., 2021.

- R. Beaulieu-Jones et al., “Privacy-preserving generative deep neural networks support clinical data sharing,” Circ.: Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes, vol. 12, no. 7, e005122, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Johnson et al., “MIMIC-CXR-JPG: A large publicly available database of labeled chest radiographs,” arXiv:1901.07042, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. He et al., “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” in CVPR, pp. 770–778, 2016.

- G. Huang et al., “Densely connected convolutional networks,” in CVPR, pp. 2261–2269, 2017.

- J. M. Gorriz et al., “Explainable AI in medical imaging,” Phys. Med., vol. 83, pp. 242–265, 2021.

- A. Sergeev and M. D. Balso, “Horovod: Fast and easy distributed deep learning in tensorflow,” arXiv:1802.05799, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Krishnan et al., “Scaling healthcare AI: Deploying containerized ML pipelines in hospital systems,” arXiv:2107.11127, 2021.

- E. Moen et al., “Deep learning for cellular image analysis,” Nat. Methods, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 1233–1246, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Malhotra, M. Saqib, D. Mehta, and H. Tariq, “Efficient Algorithms for Parallel Dynamic Graph Processing: A Study of Techniques and Applications,” Int. J. Commun. Netw. Inf. Security, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 519–534, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).