1. Introduction

Global warming and energy security are among the most critical challenges of the 21st century [

1]. Fossil fuels, which account for 80% of global energy consumption, are primary drivers of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change [

2]. This dependency also creates geopolitical tensions due to the uneven distribution of resources. To address these issues, governments and industries worldwide are transitioning to renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower [

3].

Hydrogen is emerging as a key energy carrier in this transition, with the potential to decarbonize sectors such as transportation, heavy industry, and energy storage [

4]. It offers high energy density, versatility, and compatibility with renewable energy systems, producing no direct emissions during use. Additionally, hydrogen provides a solution to the intermittency challenges associated with renewable energy by acting as a storage medium [

5].

Despite these advantages, the economic challenge of producing cost-competitive green hydrogen persists, particularly in systems reliant on renewable-powered electrolysis. Optimising production schedules to align with low-cost electricity periods and managing storage levels effectively are essential to reducing costs and ensuring reliability.

This study presents a novel predictive simulation model using AI-driven methods to address these challenges. The model employs Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) with Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) to forecast electricity prices, natural gas flow, and hydrogen storage needs, enabling dynamic production optimisation. Through comparative analysis with traditional methods, this paper demonstrates the model’s ability to reduce production costs while maintaining operational efficiency. By focusing on the predictive model’s performance and practical applications, this work contributes to advancing the economic viability of green hydrogen.

2. Hydrogen Production Processes and Cost Dynamics

Green hydrogen is primarily produced through water electrolysis, with Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) and Alkaline Electrolysis being the most widely utilised technologies [

6,

7]. PEM electrolysis is characterised by its high efficiency, compact design, and rapid responsiveness to fluctuating renewable energy inputs, making it particularly well-suited for integration with intermittent energy sources such as solar and wind [

8,

9]. Despite these advantages, PEM systems rely on expensive materials, including platinum and iridium, which significantly increase capital costs. Additionally, challenges related to the durability of these materials persist due to degradation during operation [

6,

7]. In contrast, Alkaline Electrolysis represents a mature and cost-effective technology that employs non-noble metal catalysts and a liquid electrolyte, thereby lowering capital expenditure. However, this approach has inherent limitations, such as a slower response time and reduced hydrogen purity, which diminish its suitability for direct integration with renewable energy systems [

8,

10,

11].

2.1. Cost Components of Green Hydrogen Production

Green hydrogen production costs are influenced by several critical factors. Foremost among these is electricity, which accounts for 50–70% of the overall production costs [

12]. Markets such as Australia, where renewable energy integration has led to periods of surplus generation, offer significant opportunities to lower production costs by leveraging reduced electricity prices during these times [

13,

14]. Capital expenditure (CapEx) also plays a crucial role, PEM systems incur higher costs due to the use of expensive components, whereas alkaline systems, while more affordable, require larger installations to achieve equivalent output levels [

8]. Operational and maintenance (O&M) costs further impact economic viability, with PEM systems experiencing elevated costs associated with component degradation, while alkaline systems face expenses related to electrolyte maintenance and diaphragm replacements. Lastly, infrastructure costs, encompassing storage, transportation, and distribution, present additional financial burdens, highlighting the need for system-wide optimisation to enhance cost efficiency.

These cost challenges underscore the need for advanced predictive tools to optimise production processes dynamically. By aligning hydrogen production with periods of low electricity prices and managing storage and blending effectively, AI-driven predictive models offer a path toward cost-competitive green hydrogen production [

15].

3. The Role of Renewable Energy in Hydrogen Production Costs

Renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, are critical to reducing the carbon footprint of hydrogen production [

7]. However, their high variability and intermittency create challenges for achieving consistent and cost-effective operations. For instance, electricity prices fluctuate significantly based on renewable energy availability, leading to periods of both surplus generation and scarcity [

3]. These fluctuations directly influence the economic viability of hydrogen production.

AI offers innovative solutions to address these challenges. By forecasting electricity prices and renewable energy availability, AI-driven predictive models enable hydrogen producers to optimise production schedules dynamically. For example, an RNN with GRU can analyse historical electricity prices, renewable energy data, and market trends to predict price fluctuations with high accuracy [

16].

In this study, the predictive simulation model demonstrated its ability to:

Align hydrogen production with periods of low-cost renewable electricity.

Minimise reliance on high-cost electricity periods by leveraging hydrogen storage.

Enhance overall system efficiency by dynamically managing production schedules and blending operations.

By integrating renewable energy forecasting into the hydrogen production process, the AI-driven predictive model bridges the gap between renewable energy intermittency and the cost optimisation required for widespread green hydrogen adoption.

1.1. Impact on Hydrogen Economics

AI’s integration into hydrogen production systems directly supports cost reduction targets such as the Australian government’s

$2.00/kg goal for green hydrogen [

17]. By enabling precise scheduling, reducing electricity expenditures, and optimising storage and distribution, AI enhances the economic viability of hydrogen production. These advancements make green hydrogen competitive with fossil fuel-based alternatives, paving the way for large-scale adoption. [

18]

4. Hydrogen Production Process Example

To illustrate a typical hydrogen production process, this paper references a commercially operational facility employing a 1.25 MW PEM electrolyser [

19,

20]. The process involves converting purified water and renewable electricity into high-purity hydrogen, which is distributed for various applications, including integration with natural gas networks and industrial supply chains.

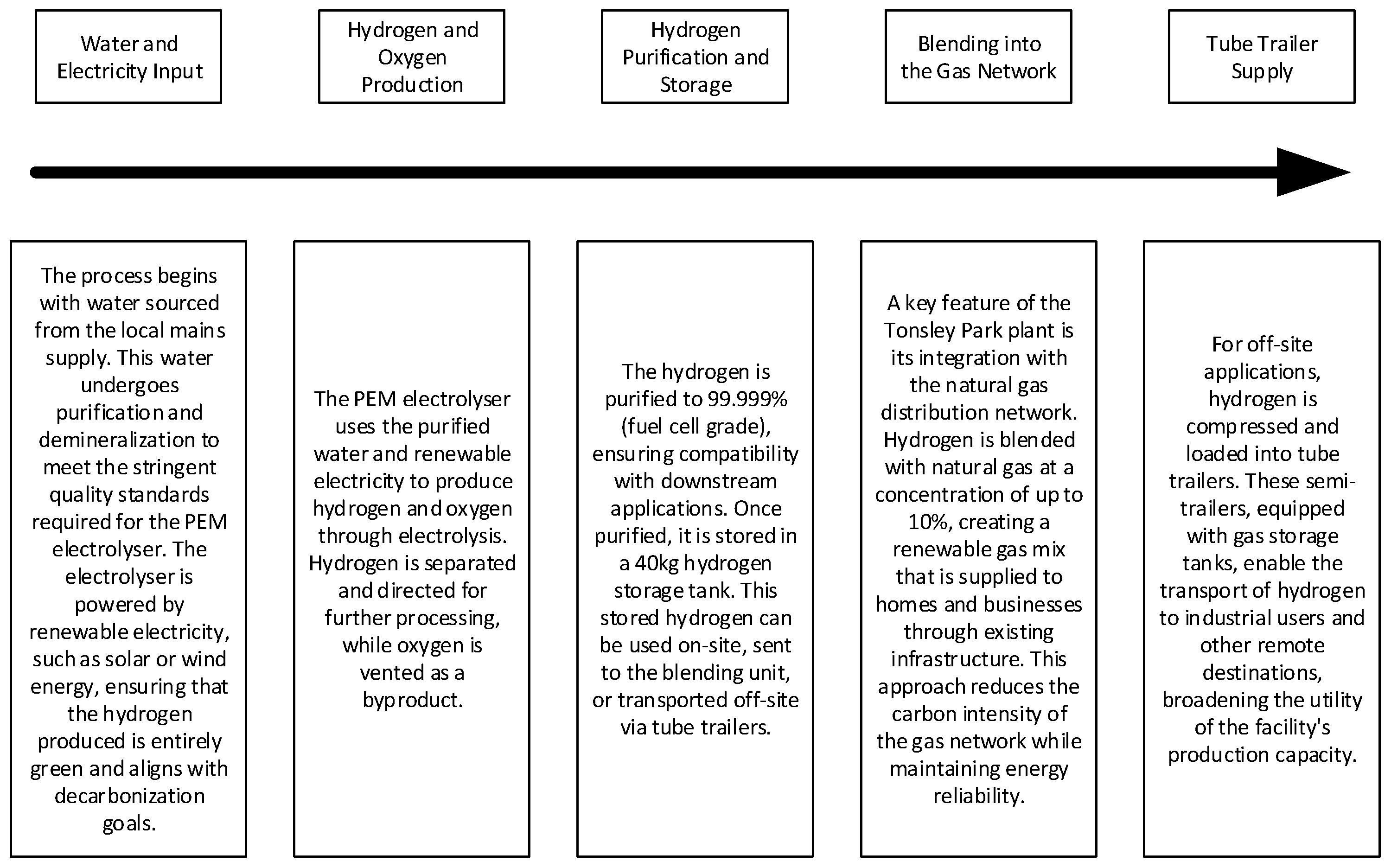

The flow diagram as illustrated in

Figure 1 provides an overview of the key operational stages involved in the hydrogen production process:

5. AI Demonstrating Efficiency in Electricity Price Prediction

As noted in section 2.1, electricity costs dominate hydrogen production, accounting for 50–70% of total expenses [

12]. This highlights the critical need to align production schedules with periods of low electricity prices to enhance cost efficiency

Accurately forecasting electricity prices is crucial for optimising electrolyser operations and minimising production costs. This study employs an RNN with GRU model to predict electricity prices 5 days in advance, demonstrating AI’s efficiency in addressing this challenge.

The predictive simulation model leverages historical electricity prices, renewable energy data, and market trends to identify patterns and forecast future price fluctuations. The model’s ability to accurately predict electricity price trends enables hydrogen producers to:

Avoid operating electrolysers during high-cost periods.

Align production with surplus renewable energy availability, reducing overall electricity expenditures.

Maintain adequate hydrogen reserves to ensure blending consistency during non-production periods.

5.1. Model Performance and Comparisons

The effectiveness of the RNN-GRU was assessed by comparing its performance against traditional models, including linear regression and ARIMA. Key metrics such as Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD), and Interquartile Range (IQR) were utilised to measure predictive accuracy and reliability in forecasting electricity prices.

Table 1 highlights the advantages of the RNN-GRU model in capturing variability and accurately predicting price trends:

RNN-GRU: The RNN-GRU model demonstrates the best ability to capture the variability and spread in electricity prices. Its MAD (21.06) is much closer to the actual MAD (37.97), and its IQR (36.26) closely approximates the actual IQR (49.18).

Linear Regression: Linear regression fails to capture the variability in electricity prices, with a significantly lower MAD (2.25) and IQR (4.06) compared to actual values. This indicates an oversimplified prediction.

ARIMA: ARIMA performs better than linear regression in terms of MAD (31.60) but fails to capture the spread of electricity prices, as indicated by an IQR of 0.00, effectively flat-lining the predictions.

5.2. Dynamic Optimisation for Hydrogen Production

The RNN-GRU model has proven to be highly effective in optimising hydrogen production processes by addressing critical operational challenges [

21]. One of its key contributions is its ability to facilitate dynamic scheduling, allowing hydrogen producers to avoid high-cost electricity periods while capitalising on surplus renewable energy availability. This ensures that production aligns with economic and sustainability objectives. Furthermore, the model enhances storage management by maintaining adequate hydrogen reserves to meet blending requirements during periods of production downtime. By dynamically adjusting production schedules based on predictive insights, the system ensures a consistent and reliable supply of hydrogen. Additionally, the model significantly reduces costs through the effective utilisation of electricity pricing trends, minimising expenditures and advancing the economic viability of green hydrogen production.

6. AI-Based Prediction for Natural Gas Distribution in Hydrogen Blending

To validate the model’s performance, the RNN-GRU was compared with traditional methods, including linear regression and ARIMA. The results, summarised in

Table 2, highlight the advantages of the RNN-GRU model:

6.1. Results

RNN-GRU: Closely matches actual metrics, with MAD and IQR values aligning well with real-world data, demonstrating its ability to capture variability and patterns in gas flow effectively.

Linear Regression: Over-simplifies the predictions, with a significantly higher MAD (115.6) and much lower IQR (11.65) than actual values, rendering it inadequate for dynamic gas flow scenarios.

ARIMA: Although it achieves lower MAD (18.45), its inability to capture variability (IQR = 0) makes it less reliable for operational use.

6.2. Summary

The results demonstrate that the RNN-GRU model significantly outperforms traditional methods in accurately predicting natural gas flow variability and trends. This predictive capability enables optimised storage management by ensuring that hydrogen reserves are consistently maintained at levels sufficient to support uninterrupted blending operations. Moreover, the model facilitates dynamic scheduling by aligning hydrogen production schedules with real-time gas demand forecasts. This alignment minimises operational costs while maintaining reliability, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency and sustainability of hydrogen production systems.

7. Storage Management

Effective storage management is essential to maintaining consistent hydrogen blending within natural gas networks, particularly during periods when electrolyser operation is uneconomical due to high electricity prices or scheduled maintenance. This section outlines a predictive framework that leverages AI-driven insights to optimise hydrogen storage requirements.

7.1. Predictive Storage Framework

The proposed framework integrates electricity price forecasts, natural gas flow predictions, and blending ratios to determine optimal storage levels. This ensures adequate reserves during non-production periods while minimising costs.

-

Forecasting Hydrogen Demand for Blending:

-

Storage Utilisation During Non-Production:

-

Net Storage Requirement

Where:

If Sinit exceeds Sreq no additional hydrogen production is necessary.

-

Dynamic Scheduling of Production:

-

Final Storage Balancing

The storage level F

final(t) is updated to ensure alignment with blending and production:

Where:

7.2. Dynamic Hydrogen Storage and Production Optimization”

The predictive framework effectively ensures that storage levels are dynamically adjusted to consistently meet blending demands, even under fluctuating operational conditions. Furthermore, the framework optimises production by prioritising hydrogen generation during periods of low electricity costs, thereby enhancing economic efficiency. This approach also minimises operational disruptions, maintaining system reliability and functionality even during extended non-production periods, such as those caused by high electricity prices or scheduled maintenance.

8. Development and Application of a Predictive Hydrogen Plant Simulation Model

Hydrogen production systems face significant challenges in achieving economic and operational efficiency due to fluctuating electricity prices, variable demand, and storage limitations. To address these challenges, this study presents a predictive simulation model that integrates advanced analytics and real-world constraints. By leveraging AI-driven predictions, the model offers a framework for optimising hydrogen production, storage, and blending operations.

This section details the development and application of the simulation model, highlighting its functionality, performance, and contributions to advancing the economic viability of green hydrogen.

8.1. Objective and Scope

The primary objective of this simulation model is to analyse the interplay between electricity pricing, hydrogen production, and storage management within the context of blending hydrogen into natural gas networks. Central to this analysis is an evaluation of the impact of electricity price fluctuations on the operational viability and cost-effectiveness of hydrogen production. Additionally, the model examines the capacity of hydrogen storage systems to maintain uninterrupted blending during periods of non-production, thereby ensuring reliability and compliance with blending requirements. Furthermore, the operational performance of the electrolyser is assessed, with particular attention to its startup and shutdown dynamics, which significantly influence efficiency and system longevity. By simulating these factors, the model provides insights into strategies for achieving economically viable and sustainable hydrogen production.

8.2. Methodology

The simulation model incorporates several key features to optimise hydrogen production, blending, and storage within dynamic operational constraints. A critical aspect of the model is its integration of forecasted electricity prices to identify periods of economically favorable production. By aligning hydrogen production schedules with low-cost electricity availability, the model effectively minimises overall production costs, leveraging the variability inherent in electricity markets.

Another integral feature of the model is its ability to predict natural gas flow rates, which are subsequently used to calculate hydrogen demand for blending. This predictive capability ensures adherence to blending ratios while maintaining consistent and reliable operations within the natural gas network. The integration of these forecasts supports dynamic adjustments to production schedules, aligning supply with real-time demand.

Hydrogen storage management is another essential component of the model. Storage dynamics are simulated to account for production volumes, blending demands, and capacity constraints. This ensures that sufficient reserves are maintained during periods when the electrolyser is non-operational, such as during high electricity price intervals or scheduled maintenance, thereby mitigating the risk of blending disruptions.

The operational performance of the electrolyser is modeled, incorporating real-world constraints. The model dynamically schedules electrolyser operations to achieve cost-effective and sustainable hydrogen production. Several parameters are included to ensure operational efficiency and reliability. For instance, the simulation accounts for ramp-up time, modeling a one-hour transition period for the electrolyser to reach full operational capacity [

22]. This parameter provides an accurate representation of electrolyser dynamics while preventing inefficiencies during startup phases.

To reduce mechanical stress and extend equipment lifespan, the model enforces a minimum runtime of two hours for the electrolyser once it is operational. This measure mitigates the wear and tear associated with frequent start/stop cycles, ensuring both efficiency and longevity [

9]. Furthermore, the model employs a dynamic scheduling algorithm that synchronises production windows with low-cost electricity periods while maintaining adequate storage to meet blending demands. This adaptive approach balances production and demand, reducing costs and optimising system performance. By optimising production windows.

The simulation evaluates system performance using detailed metrics that capture both economic and operational effectiveness. These metrics include total operational hours of the electrolyser, total electricity costs incurred during production, the quantity of hydrogen blended into the natural gas network, the number of startup and shutdown events, the cost per kilogram of hydrogen produced, and the number of hours where negative electricity pricing was utilised

8.3. Application of Simulation Model for Hydrogen Production Optimisation

This simulation model was developed to support the design and optimisation of hydrogen production systems. A primary application is cost optimisation, where the model identifies operational strategies that minimize electricity expenses while ensuring blending requirements are consistently met. Additionally, the model aids in system planning and reliability by aligning storage capacities and production schedules with blending demands, even under fluctuating electricity prices and variable gas flow conditions. Furthermore, it serves as a tool for policy and decision-making, offering actionable insights to help stakeholders evaluate the feasibility and economic viability of hydrogen production in dynamic market environments.

8.4. Results and Analysis

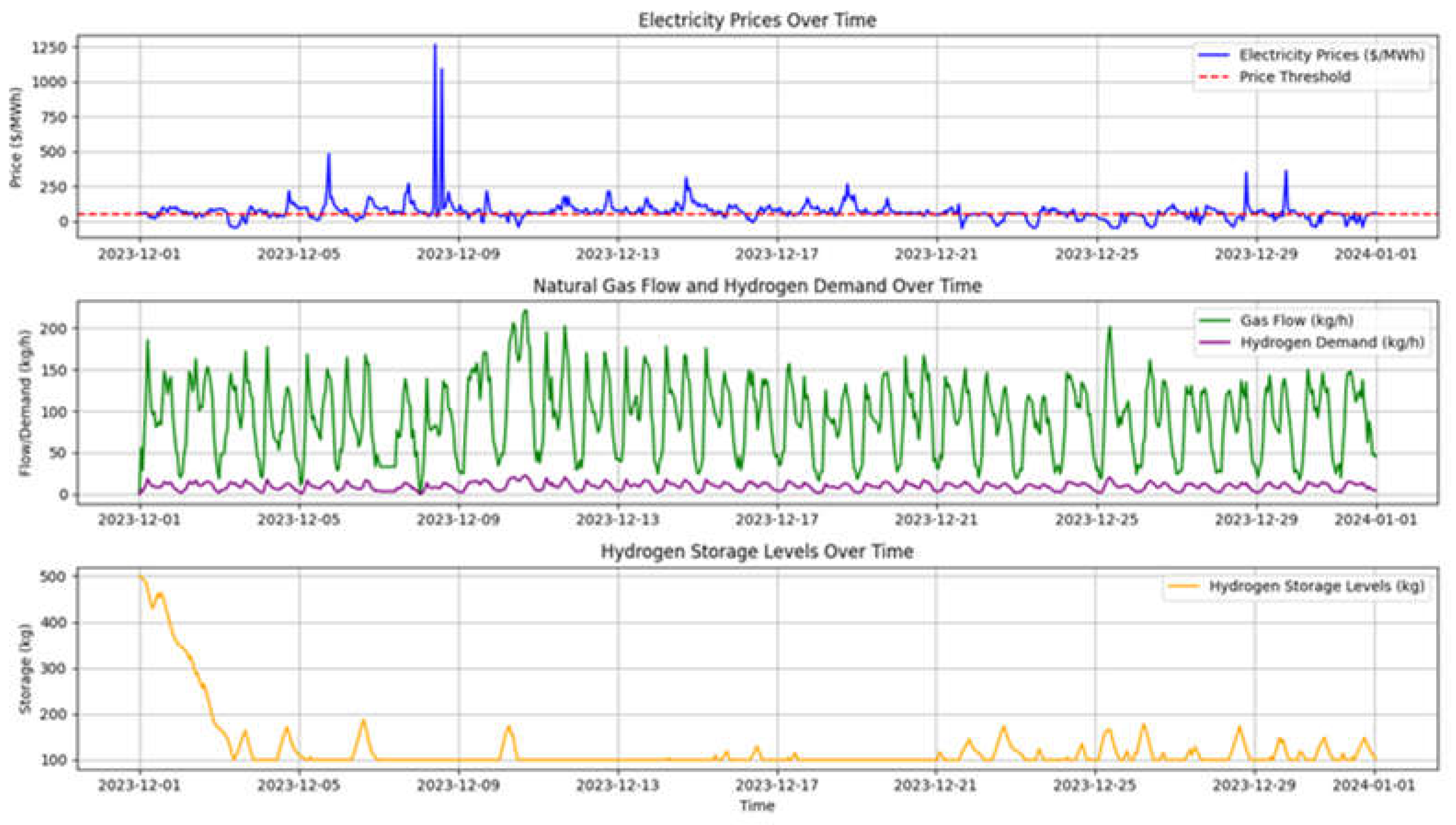

The simulation of the hydrogen plant model provides insights into the operational dynamics of hydrogen production, storage, and blending systems. The results are summarised in

Table 3, highlighting key performance metrics, and illustrated in

Figure 2, which visualise electricity pricing, gas flow, hydrogen demand, and storage levels for Tonsley Park in December 2023.

The simulation results validate the model’s capability to optimise hydrogen production by effectively managing electricity pricing, hydrogen demand, and storage levels. The alignment between low-cost electricity periods and electrolyser operation highlights the model’s ability to minimise operational costs, a critical factor in achieving competitive hydrogen production. By leveraging electricity price thresholds, the model ensures production occurs during economically favorable conditions, demonstrating its efficiency in utilising surplus renewable energy.

The model synchronises hydrogen production with dynamic blending demands derived from natural gas flow. This adaptability ensures sufficient hydrogen availability to maintain blending ratios, even during fluctuating demand. The consistent tracking of storage levels above the minimum threshold further emphasizes the model’s reliability in avoiding operational disruptions. However, the proximity of storage levels to the minimum threshold during some periods suggests potential vulnerabilities under sustained high-demand conditions or adverse electricity pricing.

While the model exhibits strong economic and operational optimisation, further improvements could enhance resilience and reduce the frequency of electrolyser start/stop cycles. Refining storage strategies could provide more excellent stability. Overall, the model demonstrates a robust framework for cost-effective and reliable hydrogen production, aligning well with green hydrogen cost reduction objectives.

Figure 2 illustrates the effectiveness of the hydrogen production model in synchronising electrolyser operation with electricity price fluctuations, natural gas flow, and storage dynamics. The model successfully prioritizes production during low-cost electricity periods while maintaining sufficient hydrogen reserves to meet blending demands, ensuring cost-efficient and reliable operations.

Table 3 shows the operational metrics of the hydrogen production model, highlighting its efficiency in managing key parameters. The electrolyser operated for a total of 119 hours over a 1-month period, blending 6887.28 kg of hydrogen at an average cost of

$1.72 per kilogram. Notably, the start/stop count was 40, reflecting the effectiveness of the scheduling algorithm in minimising equipment stress. Additionally, the electrolyser leveraged 29 hours of negative electricity pricing, further reducing overall production costs.

8.5. Summary

The hydrogen production model demonstrates a strategic balance between cost efficiency and reliability. By leveraging dynamic scheduling, the model not only minimizes electricity costs but also enhances equipment longevity. The effective utilization of low-cost electricity periods, including negative pricing, underscores its potential for sustainable hydrogen production.

9. Future Research Objectives

Future research should explore extending the capabilities of RNN-GRU models to address additional complexities in hydrogen production systems. While the current model demonstrates strong predictive performance for electricity pricing and natural gas flow, integrating multi-task learning could enable simultaneous prediction of other critical parameters, such as renewable energy availability or water consumption rates. Such advancements would provide a more holistic approach to operational optimisation.

Further investigation into hybrid AI architectures, combining RNNs with algorithms like reinforcement learning [

23], could improve decision-making in dynamic environments, particularly under scenarios of high variability in demand or pricing. Additionally, applying transfer learning to adapt pre-trained models to different operational scales or geographic regions could enhance the model’s generalisability and scalability [

24], refine predictive accuracy and validate model assumptions in practical settings. Finally, research into these predictive models’ economic and environmental impacts under various policy frameworks, such as carbon pricing or renewable subsidies, could offer valuable insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders.

10. Summary

Research has shown that RNNs with GRUs are effective tools for predicting electricity pricing trends and optimising hydrogen production schedules [

15]. These models enable dynamic adjustments to electrolyser operations by identifying periods of low-cost electricity, facilitating cost-effective scheduling of hydrogen production. While challenges remain in precisely predicting the intensity of electricity price spikes, the primary objective of aligning production with economic conditions has been successfully demonstrated. This highlights the practical utility of RNN-GRU models in supporting operational decisions within hydrogen production systems.

Building on this foundation, the present study extends the application of RNN-GRU models by incorporating additional predictive capabilities, such as natural gas flow forecasting, to optimise hydrogen blending operations. By integrating multiple predictive elements, the model addresses the interdependent dynamics of production, storage, and blending, further advancing the economic and operational viability of green hydrogen systems.

References

- Luft, G.; Korin, A. Energy Security Challenges for the 21 Century; Greenwood Publishing Group: UNited States, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Advancing strategies on green H2 water electrocatalysis: bridging the benchtop research with industrial scale-up. Microstructures 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ibekwe, K.; Etukudoh, A.E.; Nwokediegwu, Q.S.Z.; Umoh, A.A.; Adefemi, A.; Ilojianya, I.V. ENERGY SECURITY IN THE GLOBAL CONTEXT: A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF GEOPOLITICAL DYNAMICS AND POLICIES. Engineering Science & Technology Journa 2024, 5, 152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Andeobu, L.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S. Renewable hydrogen for the energy transition in Australia - Current trends, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 87, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Government. Australias’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan A whole-of-economy Plan to achieve net zero emissions by 2050; Commonwealth of Australia 2021: Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akyüz, S.; Telli, E.; Farsak, M. Hydrogen generation electrolyzers: Paving the way for sustainable energy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 81, 1338–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.A.; Rajendran, S.; Khusnun, N.F.; Bahari, M.B.; Jahari, A.; Kamaruddin, M.J.; Ismal, M. Recent review and evaluation of green hydrogen production via water electrolysis for a sustainable and clean energy society. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSIRO. Efficient hydrogen generation via alkaline water electrolysis on low cost electrocatalysts. Available online: https://research.csiro.au/hyresearch/efficient-hydrogen-generation-via-alkaline-water-electrolysis-on-low-cost-electrocatalysts/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Fang, Y.; Li, J.; Sun, L. Multi-unit Control Strategy of Electrolyzer Considering Start-Stop Times. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Power and Energy Technology (ICPET), Beijing, China; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Jia, C.; Bai, F.; Wang, W.; An, S.; Zhao, K.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, H. A comprehensive review of the promising clean energy carrier: Hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and utilization (HPTSU) technologies. Fuel 2024, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbahi, S.; Assila, A.; Belghiti, A.A.; Laasri, S.; Kaya, S.; Hlil, E.K.; Rachidi, S.; Hajjaji, A. A comprehensive review of recent advances in alkaline water electrolysis for hydrogen production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 583–599. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, J.; Iversen, T.; Eckert, C.; Peterssen, F.; Bensmann, B.; Bensmann, S.; Beer, M.; Hartmut, W.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. Cost and competitiveness of green hydrogen and the effects of the European Union regulatory framework. Nature Energy 2024, 9, 703–713. [Google Scholar]

- Simshauser, P. Australia’s National Electricity Market: An Analysis of the Reform Experience 1998–2021; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler, W.; Muesgens, F. On the long-term merit order effect of renewable energies. Energy Economics 2021, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Bassey, K.E.; Ibegbulam, C. Mchiene Learning for Green Hydrogen Production. Computer Science & IT Research Journal 2023, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.; Akhtar, K. Optmisation and Automation of Hydrogen Production With Recurrent Neural Networks; Engineering Institute of Technology: Perth, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. National Hydrogen Stratagy 2024; Commonwealth of Australia 2024: Canberra ACT 2601, 2024.

- Longden, T.; Beck, F.J.; Jotzo, F.; Andrews, R.; Prasad, M. ‘Clean’ hydrogen? – Comparing the emissions and costs of fossil fuel versus renewable electricity based hydrogen. Applied Energy 2022, 306. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Gas Infrustructure Group. Hydrogen Park South Australia. 2024. Available online: https://www.agig.com.au/hydrogen-park-south-australia (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Australian Hydrogen Centre. Hydrogen Park South Australia (HyP SA); Australian Government, Australian Renewable Energy Agency: South Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, R.; Hou, Y.; Li, W.; Jiang, C.; Pan, X.; Zhong, M. Performance Prediction of Proton Exchange Membrane Hydrogen Fuel Cells Using the GRU Model. In Proceedings of the WCX SAE World Congress Experience; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tuinema, B.W.; Adabi, E.; Ayivor, P.K.; Suarez, V.G.; Liu, L.; Perilla, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Torrez, J.L.R.; van der Meijden, M.A.; Palensky, P. Modelling of large-sized electrolysers for real-time simulation and study of the possibility of frequency support by electrolysers. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Z.; Karakose, M. Comparative Study for Deep Reinforcement Learning with CNN, RNN, and LSTM in Autonomous Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry: Way Towards a Sustainable Economy (ICDABI), Sakheer, Bahrain; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vrbancic, G.; Podgorelec, C. Transfer Learning With Adaptive Fine-Tuning. IEEE 2020, 8, 196197–196211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).