Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Background

2.1. Research Questions

- What are the privacy preservation techniques used in the published works?

- What type of IoT edge devices are used and affected by the applied techniques?

- What are the privacy attacks and threats that have been studied and mitigated?

2.2. Related Work

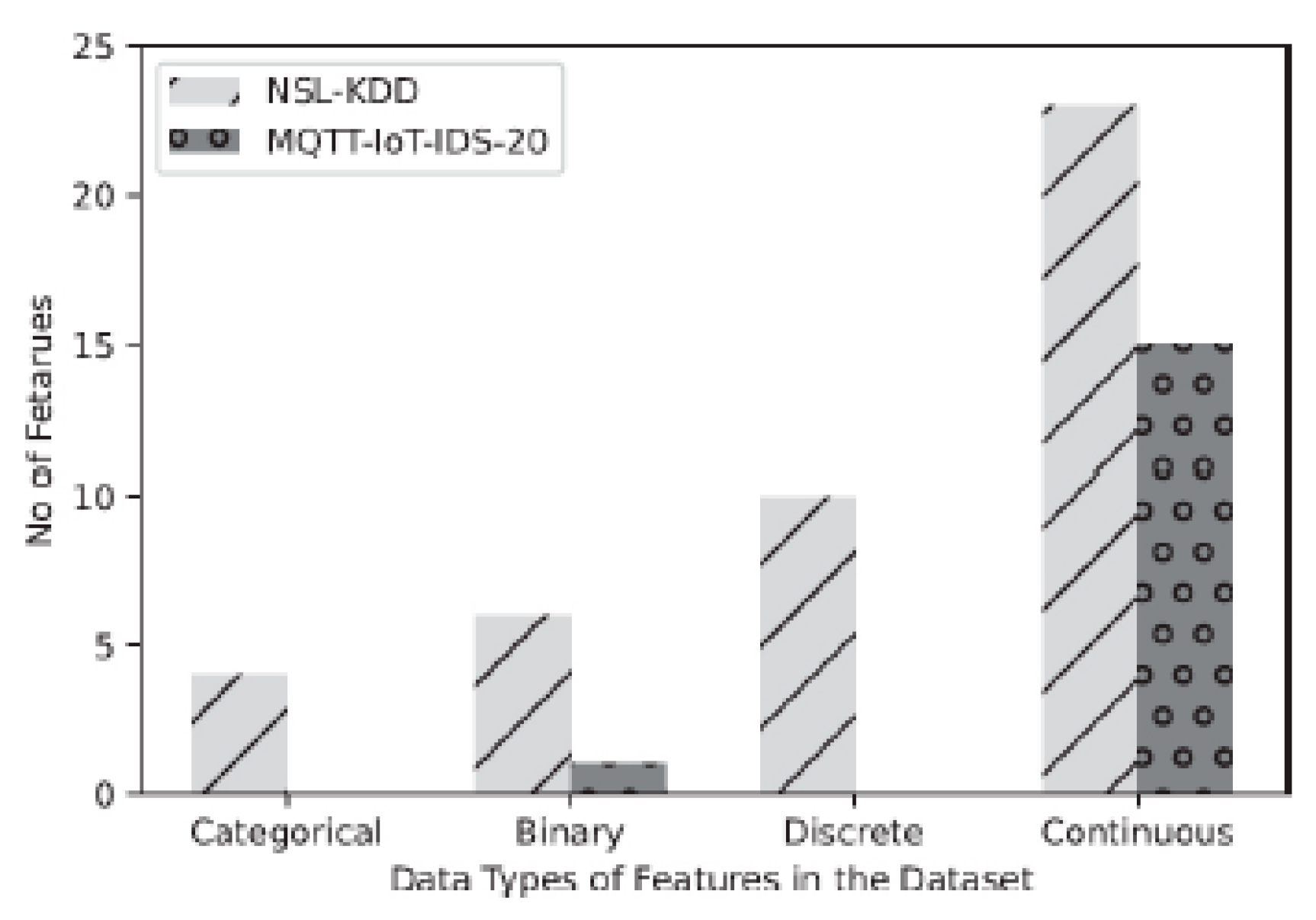

3. Data Sources and Types

| Dataset | Total | Normal | Scan-A | Scan-sU | Sparta | MQTT-BF |

| Packet | 259379 | 86008 | 25693 | 39664 | 91318 | 16696 |

| Uniflow | 49525 | 171836 | 51358 | 56845 | 182407 | 33079 |

| Bi flow | 259379 | 86008 | 25693 | 39664 | 91318 | 16696 |

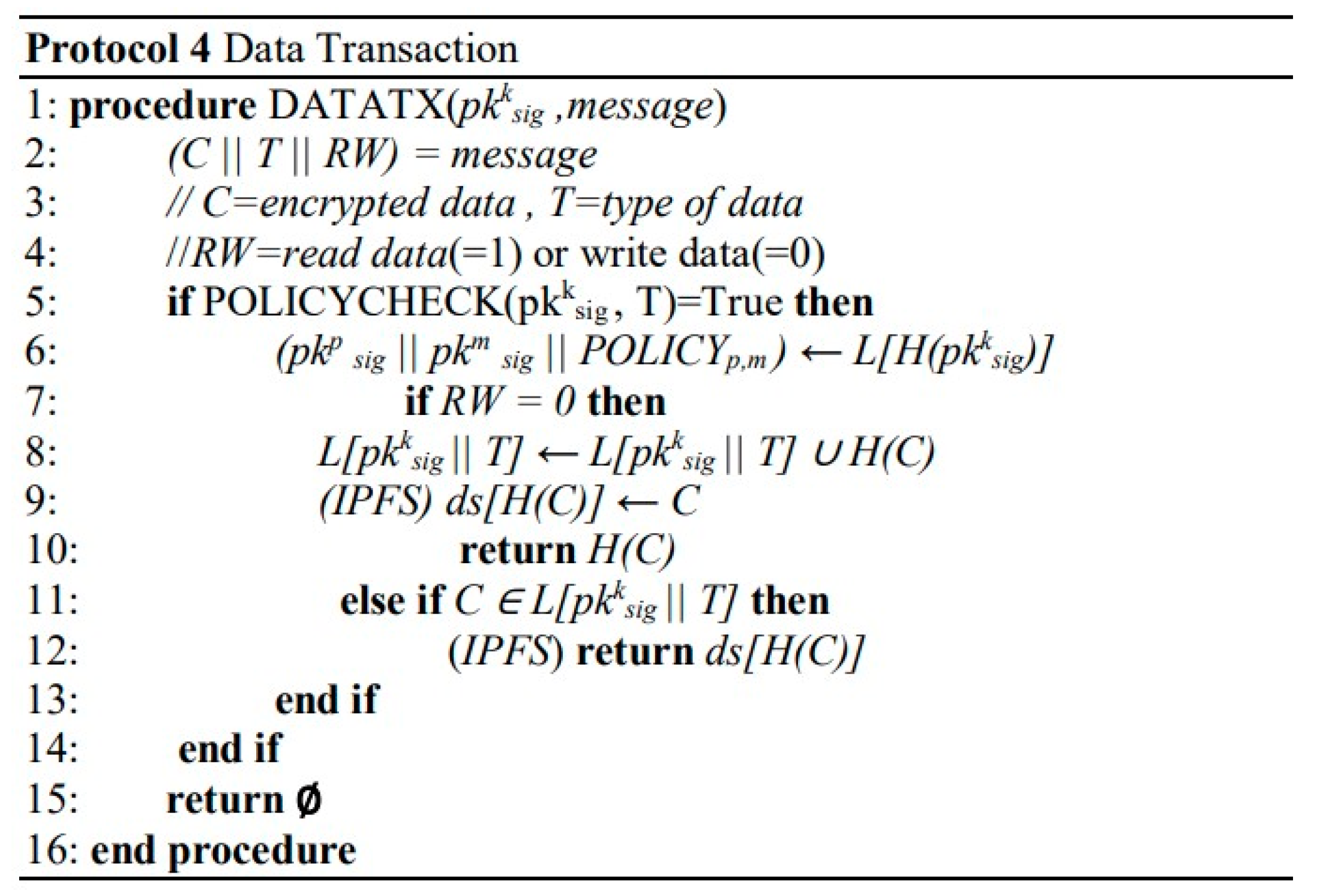

| Dataset | Total | Normal | DOS | Probe | U2R | R2L |

| KDDTrain+ | 125973 | 67343 | 45927 | 11656 | 52 | 995 |

| KDDTest+ | 22544 | 9711 | 7458 | 2421 | 200 | 2654 |

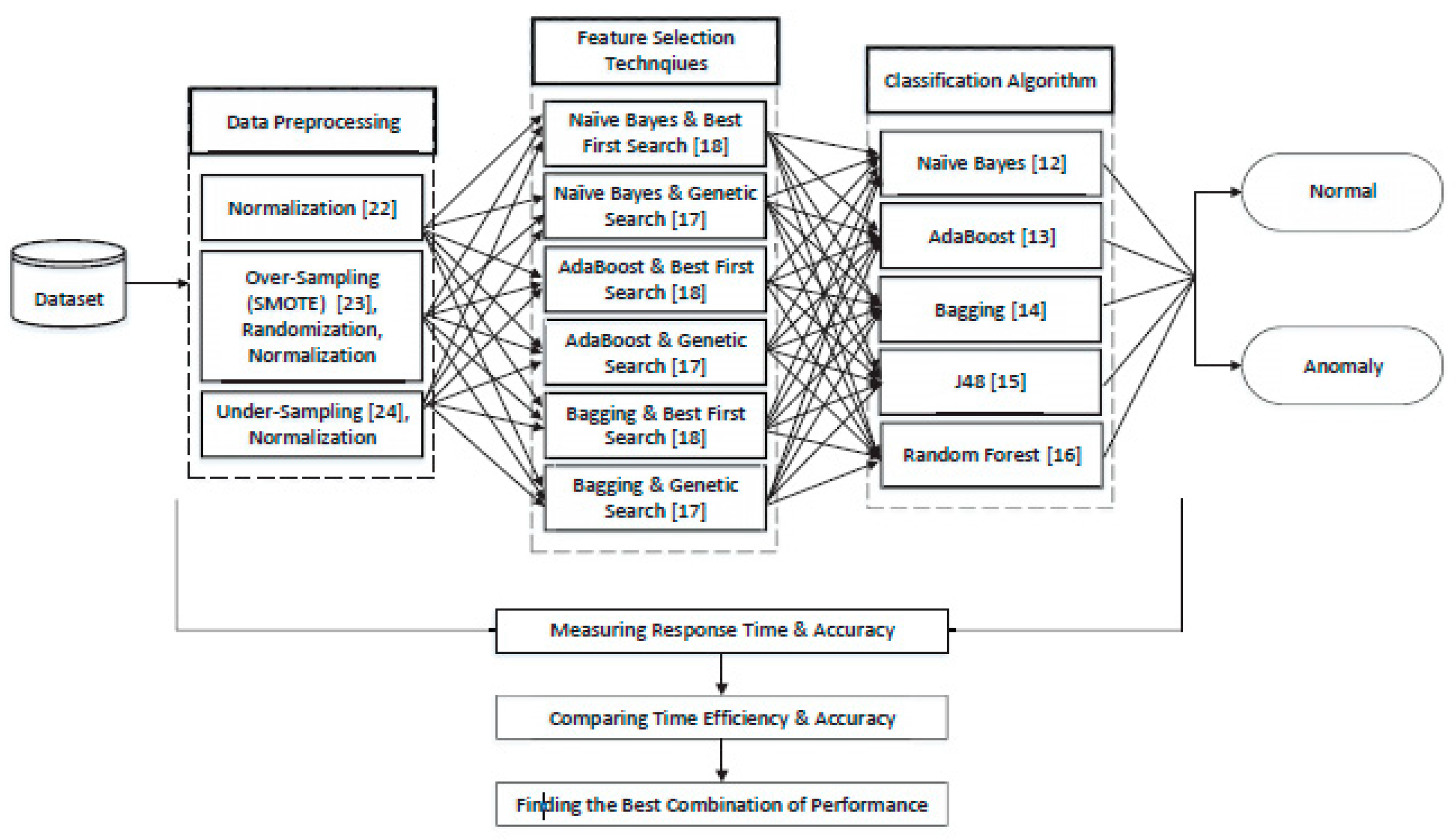

4. Analytical Models Used

5. Discussions

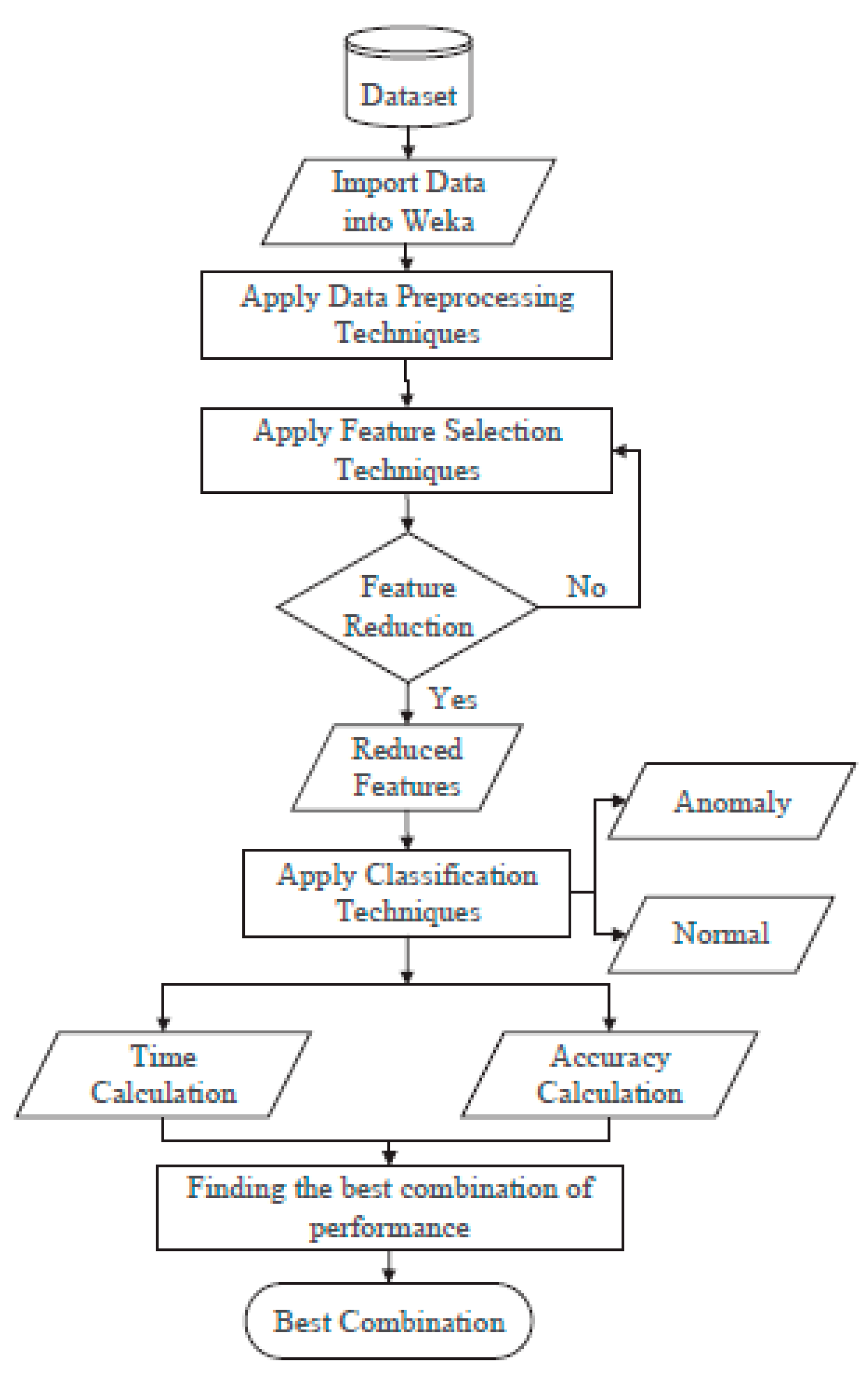

5.1. Data Preprocessing

- Normalization technique transforms the dataset’s features into the same scale. The process changes the numeric columns into a common range without value distortion. But normalization is not applied to the class feature.

- Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) is used for the synthetic data generation from the minority class. The oversampling technique creates new instances which continuously produce anomalous data for the dataset randomization.

- Sampling technique is used to delete the instances from the minority class. Overall, the data preprocessing technique deletes examples from the minority class for dataset balancing.

5.2. Feature Reduction

5.3. Classification Models

- Naïve Bayes algorithm is used, which is a supervised machine learning technique.

- AdaBoost algorithm is used, a boosting technique in machine learning applied as an ensemble method.

- Bagging algorithm is used, which is an ensemble learning technique. Bagging is used to reduce variance where noise is present in the dataset. In MQTT-IoT-IDS, some noise level is present, which is why the Bagging algorithm is used in the experiment.

- J48 algorithm is used, which is a tree-based machine learning algorithm. It uses entropy for building decision trees. A decision tree-based algorithm can detect missing values.

- Random Forst algorithm is used, a supervised machine learning algorithm for accurate and stable results. The main advantage of this algorithm is that it can be applied to classification and regression problems.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

References

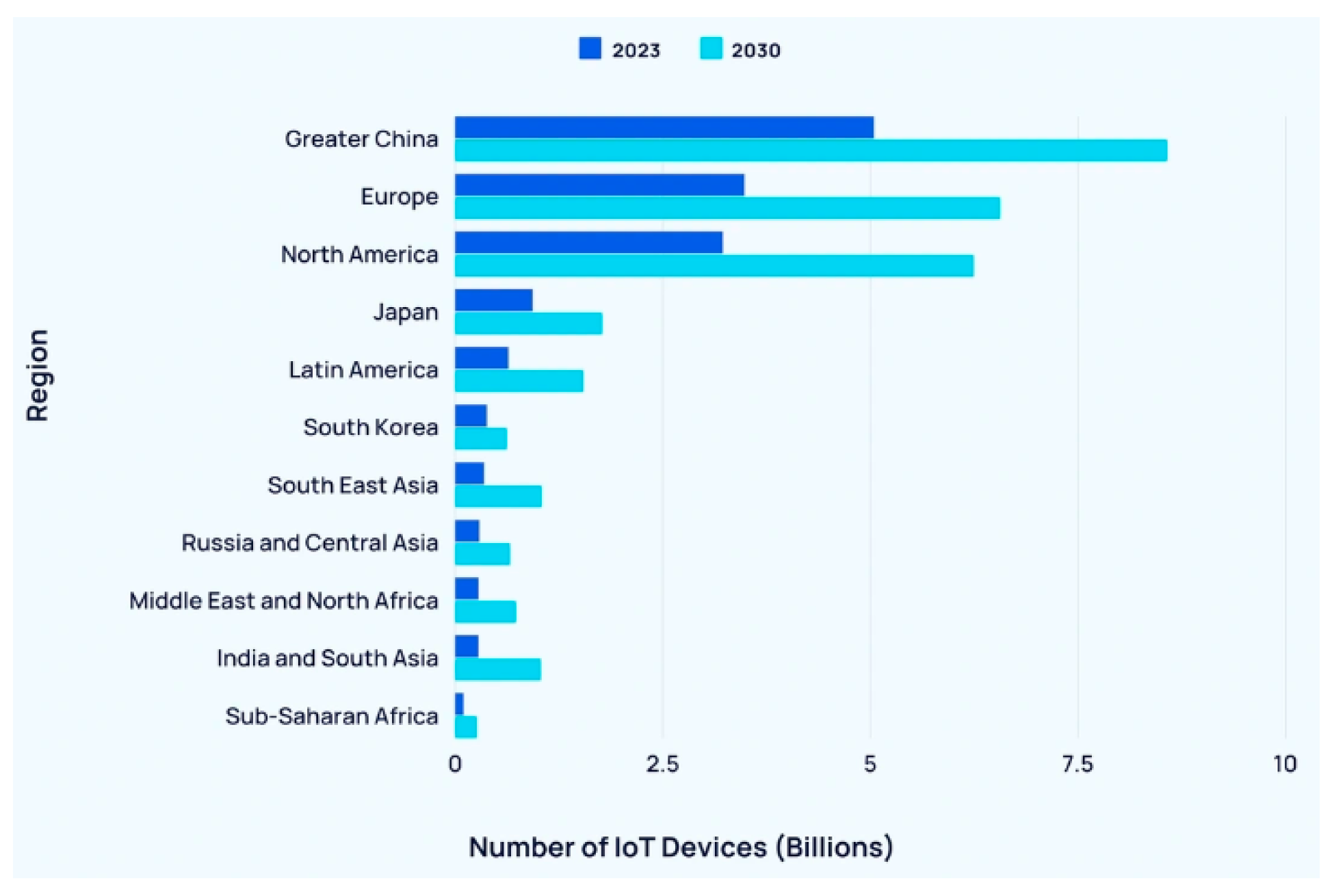

- Duarte, F. EXPLODING TOPICS, 22 February 2023. Available online: https://explodingtopics.com/blog/number-of-iot-devices (accessed on 27 October 2023).

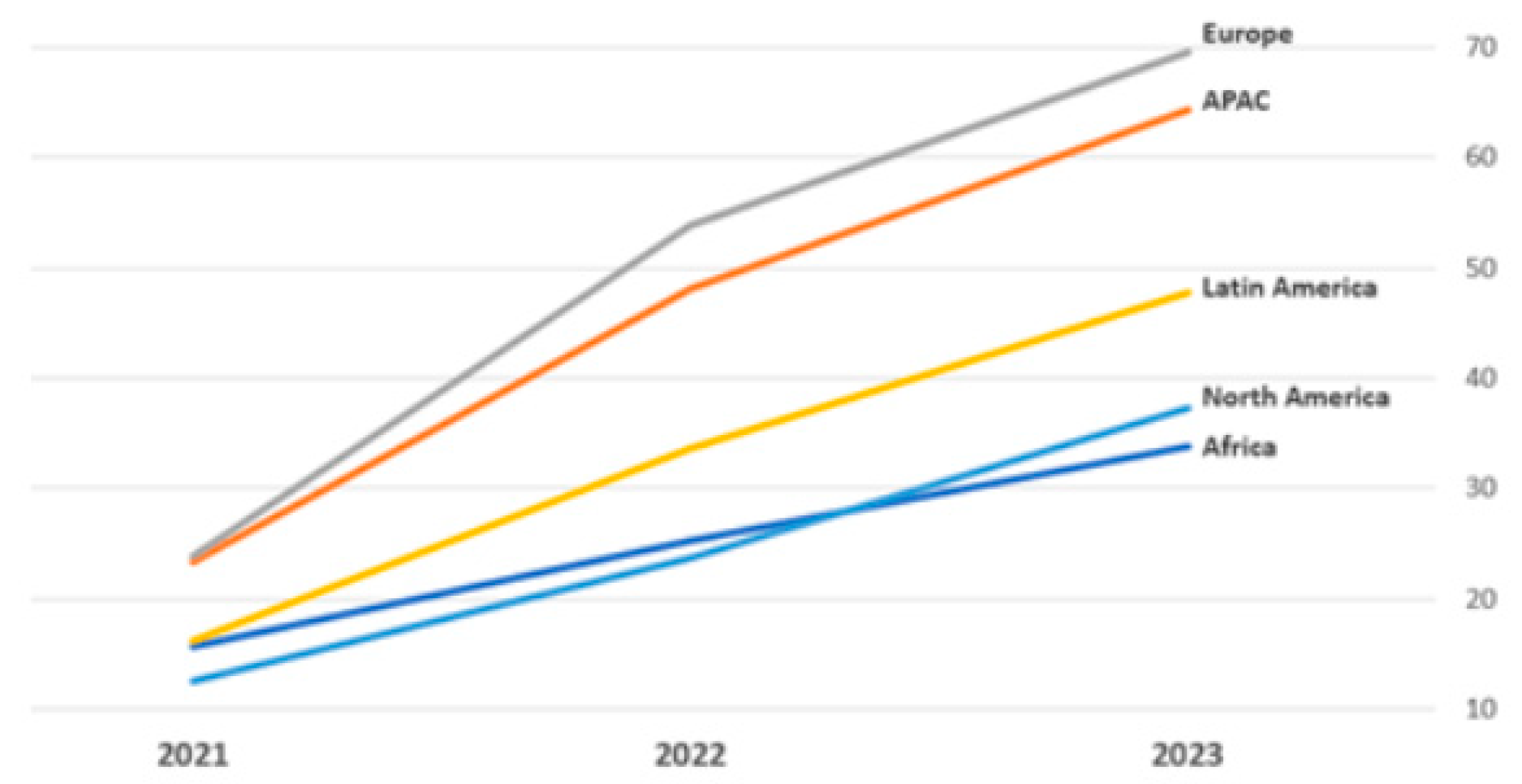

- CHECK POINT. Check Point Research, 11 April 2013. Available online: https://blog.checkpoint.com/security/the-tipping-point-exploring-the-surge-in-iot-cyberattacks-plaguing-the-education-sector/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Xue, W.H.W.G.P.S.A. ; J. In S. An efficient privacy-preserving IoT system for face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 Workshop on Emerging Technologies for Security in IoT (ETSecIoT), IEEE, April 2020; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yuhala, P. Enhancing IoT Security and Privacy with Trusted Execution Environments and Machine Learning. arXiv arXiv:2305.02584, 2023.

- L., J.D.; Carson, R.L. Automatic Classification of Web and IoT Privacy Policies. In Proceedings of the IEEE 19th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Smart Systems (MASS), October 2022; pp. 732-735.

- Elkahlout, M.A.-S.M.A.A.I.A. ; D. In M. 2. A... I. 2. I. C. o. A. a. R. T. IoT-Based Healthcare and Monitoring Systems for the Elderly: A Literature Survey Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Assistive and Rehabilitation Technologies (iCareTech), IEEE, 28 August 2020; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- R., B.; Meenakshiammal, K. Preserving Patient Privacy in IoT Based Breast Cancer Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Edge Computing and Applications (ICECAA), IEEE, 19 July 2023; pp. 1370-1374.

- N., F.M.; Schiliro, B.A. Cognitive privacy: AI-enabled privacy using EEG signals in the internet of things. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Conference on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud and Big Data Systems and Application (DependSys), 14 December 2020; pp. 73-79.

- ., E.; Fazeldehkordi, N. J. Security and privacy in IoT systems: a case study of healthcare products. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology (ISMICT), IEEE, 8 May 2019; pp. 1–8.

- Gochoo, M.T.T.H.S.B.T.H.J.A.F.C.Y. Novel IoT-based privacy-preserving yoga posture recognition system using low-resolution infrared sensors and deep learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 7192–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jui, T.H.M.M.S.H.M. Feature Reduction through Data Preprocessing for Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA), IEEE, 13 December 2021; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- ., E.; Fazeldehkordi, N.J. Security and Privacy Functionalities in IoT. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), IEEE, ; pp. 1-12. 26 August 2019.

- Agbohungbe, O.R.S.D.X.Q.L. Efficient privacy-preserving edge intelligent computing framework for image classification in IoT. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2021, 6, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbohungbe, R.S.D.X.Q.L. Efficient privacy-preserving edge intelligent computing framework for image classification in IoT. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2021, 6, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.; Alotaibi, M. A stacked deep learning approach for IoT cyberattack detection. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 8828591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

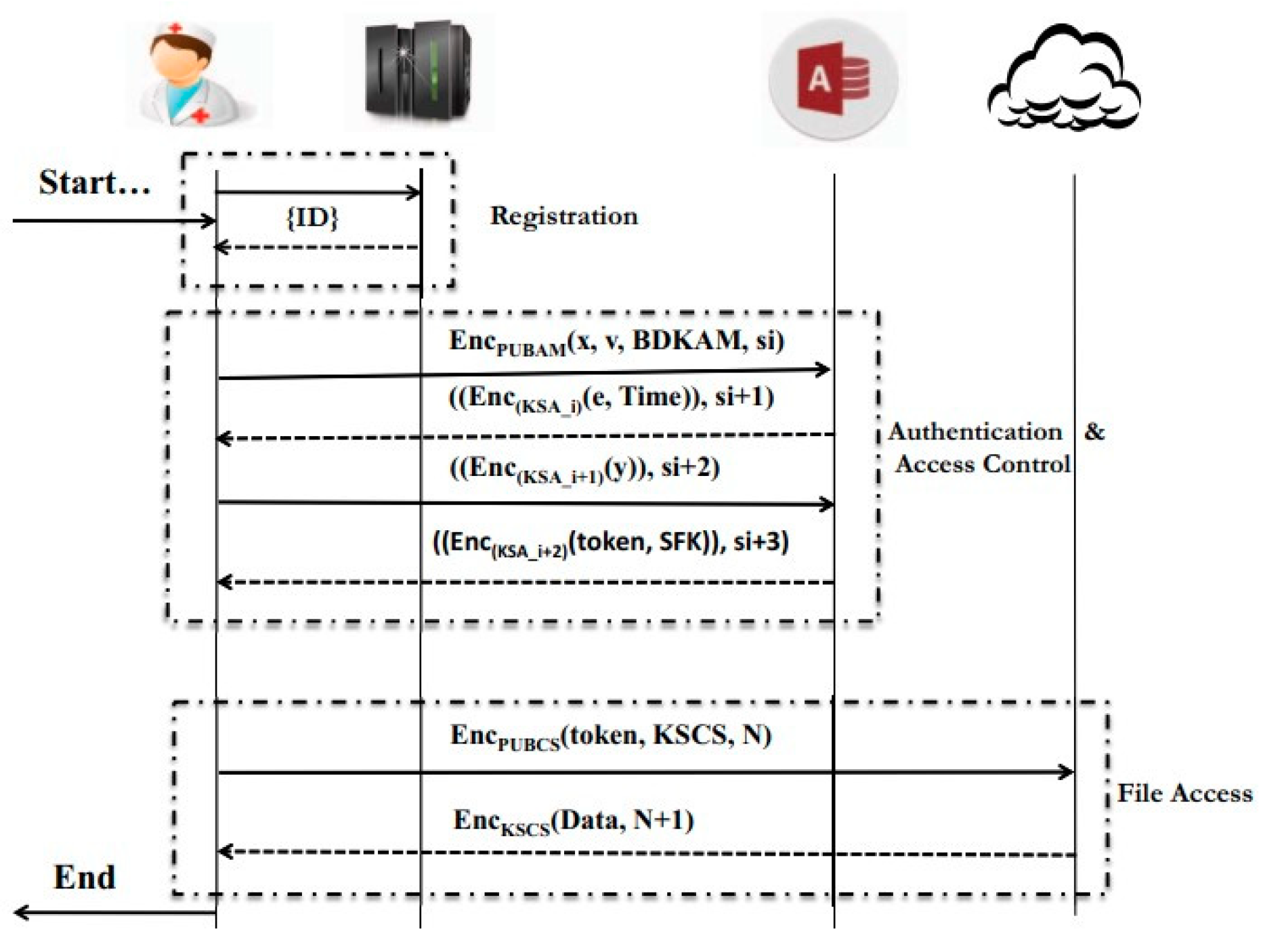

- Kahani, N.; Elgazzar, K.; Cordy, J.R. Authentication and access control in e‐health systems in the cloud. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data Security on Cloud (BigDataSecurity), IEEE International Conference on High Performance and Smart Computing (HPSC), and IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Data and Security (IDS), 13‐23 July 2016.

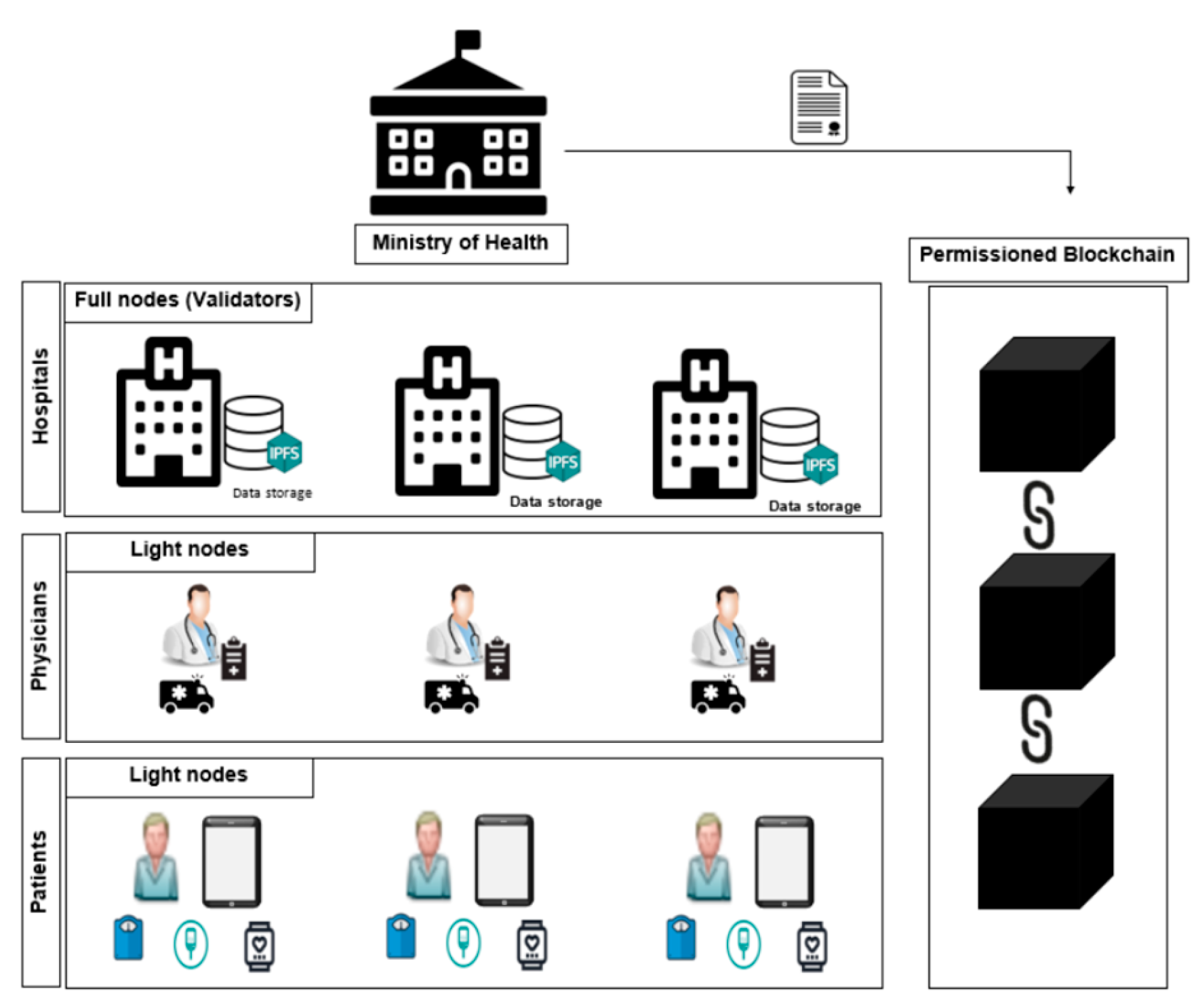

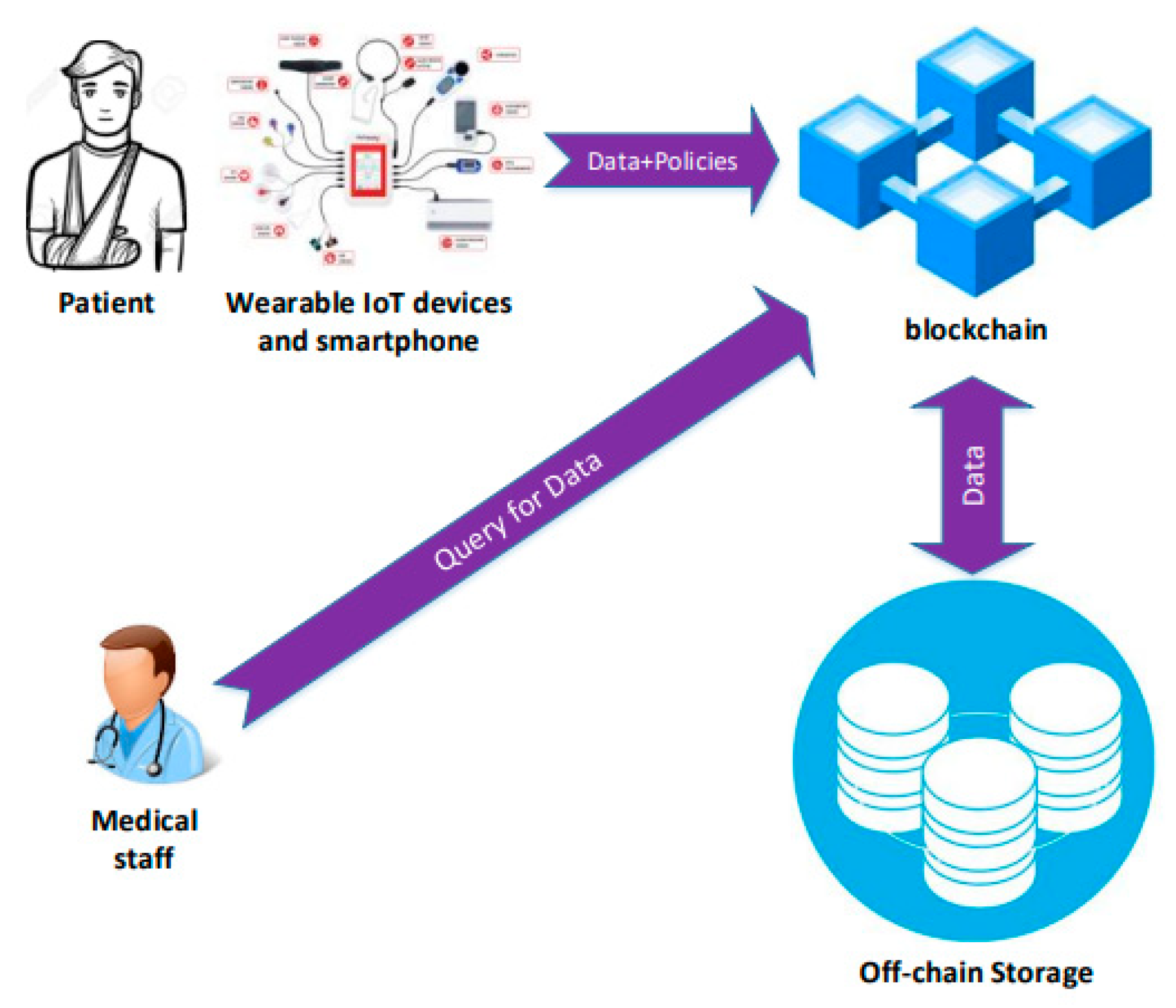

- Meisami, S.; Atashgah, M.B.; Aref, M.R. Using blockchain to achieve decentralized privacy in IoT Healthcare. Int. J. Cybern. Inform. 2023, 12, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Sarwate, A.D.; Mandayam, N.B. Network Traffic Shaping for Enhancing Privacy in IoT Systems. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2022, 30, 1162–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azbeg, K.; Ouchetto, O.; Andaloussi, S.J. Access Control and Privacy-Preserving Blockchain-Based System for Diseases Management. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

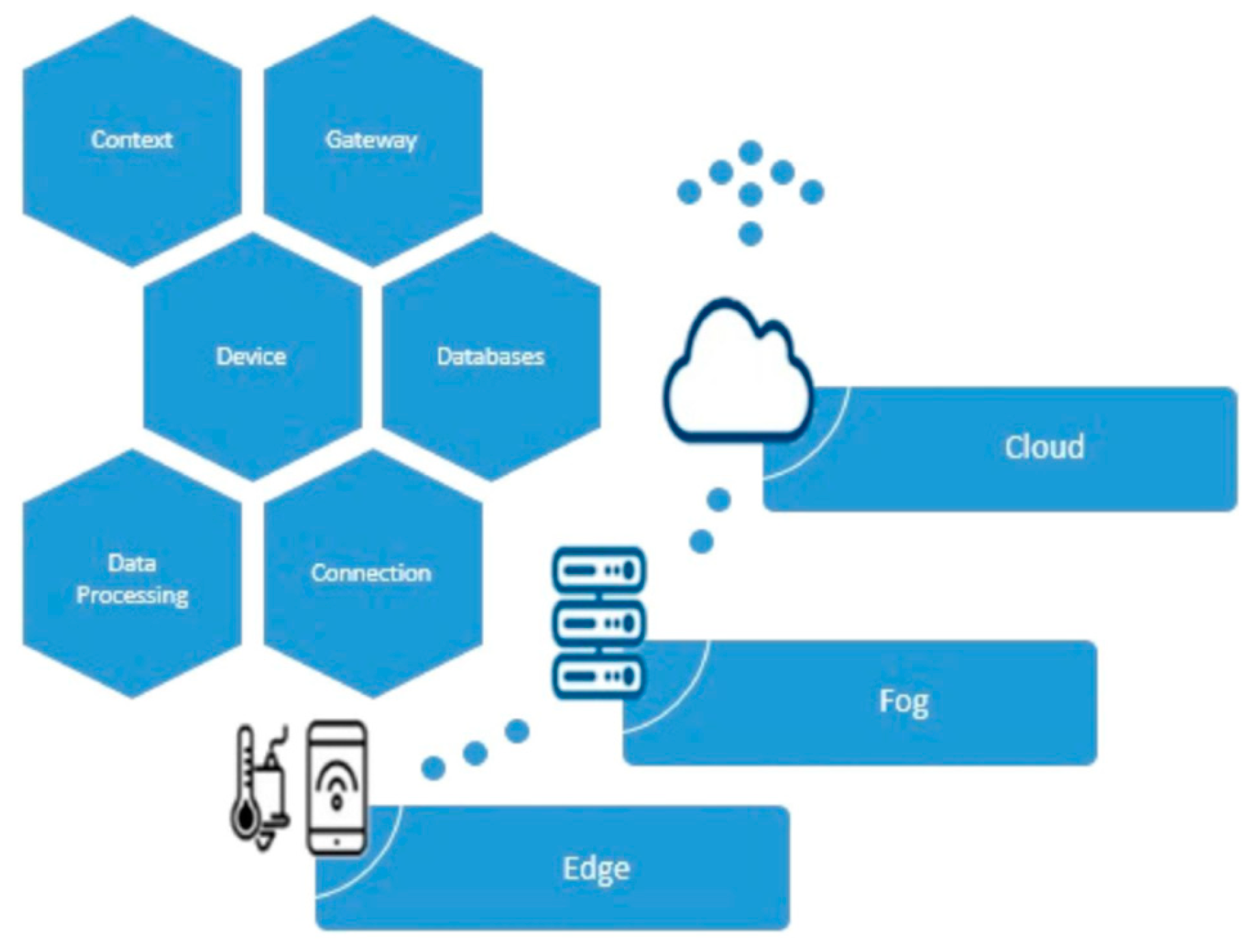

- Will, N.C. A Privacy-Preserving Data Aggregation Scheme for Fog/Cloud-Enhanced IoT Applications Using a Trusted Execution Environment. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon), Montreal, QC, Canada; 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Faujdar, N.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, A. Security and Privacy of Blockchain-Based Single-Bit Cache Memory Architecture for IoT Systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 35273–35286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wang, F.Y.; Tian, Y.; Jia, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, G. Artificial Identification: A Novel Privacy Framework for Federated Learning Based on Blockchain. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gugueoth, V.; Safavat, S.; Shetty, S.; Rawat, D. A Review of IoT Security and Privacy Using Decentralized Blockchain Techniques. Computer Science Review 2023, 50, 100585. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhariji, L.; De, S.; Rana, O.; Perera, C. Semantics-Based Privacy by Design for Internet of Things Applications. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 138, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G.; Chatterjee, P.; Lin, J.C.W. A Privacy-Preserving Internet of Things Smart Healthcare Financial System. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 18452–18460. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Namasudra, S.; Chilamkurti, N.; Kim, B.G.; Crespo, R.G. Blockchain-Based Privacy Preservation for IoT-Enabled Healthcare System. ACM Transactions on Sensor Networks 2023, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Mukherjee, P.; Verma, S.; et al. A Smart Privacy Preserving Framework for Industrial IoT Using Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Algorithm. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 5372. [Google Scholar]

- Tayeb, H.; Bramas, B.; Faverge, M.; Guermouche, A. Dynamic Tasks Scheduling with Multiple Priorities on Heterogeneous Computing Systems. 2024.

- Shen, S.; Wu, X.; Sun, P.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Z.; Yu, S. Optimal Privacy Preservation Strategies with Signaling Q-Learning for Edge-Computing-Based IoT. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 225, 120192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

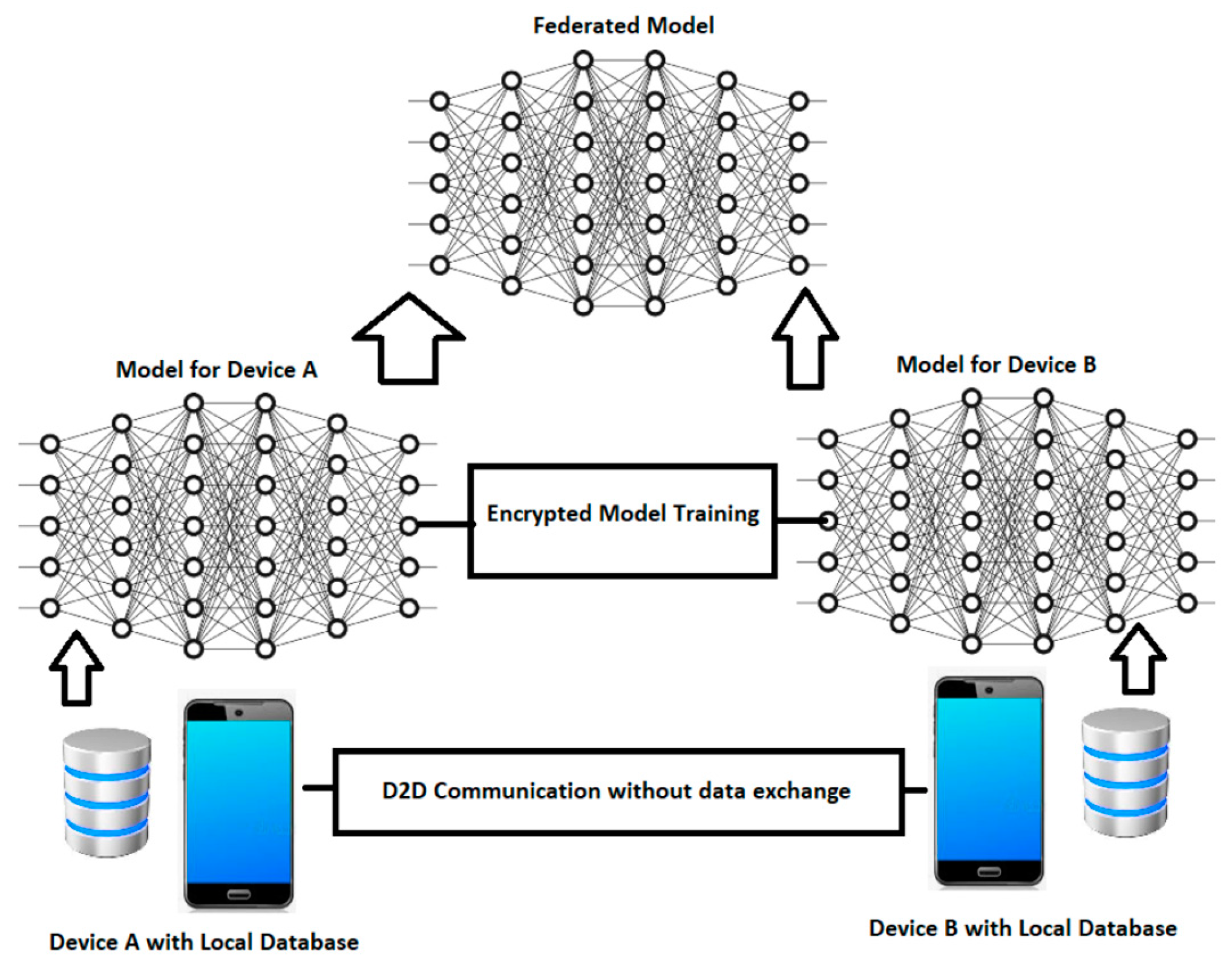

- Alam, T.; Gupta, R. Federated Learning and Its Role in the Privacy Preservation of IoT Devices. Future Internet 2022, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaraziz, M.S.; Jalili, A.; Gheisari, M.; Liu, Y. Recent Trends Towards Privacy-Preservation in Internet of Things, Its Challenges and Future Directions. IET Circuits, Devices & Systems 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Al-rimy, B.A.S.; Alsubaei, F.S.; Almazroi, A.A.; Almazroi, A.A. HealthLock: Blockchain-Based Privacy Preservation Using Homomorphic Encryption in Internet of Things Healthcare Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchige, P.C.; et al. A Trustworthy Privacy-Preserving Framework for Machine Learning in Industrial IoT Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 16, 6092–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, H.; Bramas, B.; Faverge, M.; Guermouche, A. Dynamic Tasks Scheduling with Multiple Priorities on Heterogeneous Computing Systems. 2024.

- Anajemba, J.H.; Iwendi, C.; Razzak, I.; Ansere, J.A.; Okpalaoguchi, I.M. A Counter-Eavesdropping Technique for Optimized Privacy of Wireless Industrial IoT Communications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 18, 6445–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunseyi, T.B.; Bo, T.; Yang, C. A Privacy-Preserving Framework for Cross-Domain Recommender Systems. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2021, 93, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertino, E. Data Security and Privacy in the IoT. Purdue University 2016, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; et al. Lightweight Federated Learning for Large-Scale IoT Devices with Privacy Guarantee. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 3179–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathne, S.M.; Saxena, N.; Khan, M.K. Security and Privacy in IoT Smart Healthcare. IEEE Internet Computing 2021, 25, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.; et al. Systematically Quantifying IoT Privacy Leakage in Mobile Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 7115–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Roy, A.; Misra, S.; Raghuwanshi, N.S. CASE: A Context-Aware Security Scheme for Preserving Data Privacy in IoT-Enabled Society 5.0. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 2497–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, N.; Kaur, R.; Rodrigues, T.; Kashef, R. Post COVID-19 Vaccination: Infection Rate Analysis Using Time Series Modeling. Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Machine Intelligence and Smart Innovation (ICMISI), Alexandria, Egypt, 2024; pp. 266–271. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Comparative Analysis of Power Efficiency in Heterogeneous CPU-GPU Processors. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, 24 July 2023, & Applied Computing (CSCE); pp. 756–758.

- Deebak, B. D.; Hwang, S. O. Privacy-Preserving Learning Model Using Lightweight Encryption for Visual Sensing Industrial IoT Devices. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Noise Suppression Using Gated Recurrent Units and Nearest Neighbor Filtering. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA; 2022; pp. 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Asad, A.; Mohammadi, F. A Comprehensive Review of Processing-in-Memory Architectures for Deep Neural Networks. Computers 2024, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Asad, A.; Al Abdul Wahid, S.; Mohammadi, F. A Survey of Advancements in Scheduling Techniques for Efficient Deep Learning Computations on GPUs. Electronics 2025, 14, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lai, J.; Li, X.; He, D.; Khan, M. K. RPIFL: Reliable and Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning for the Internet of Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 221, 103768. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. A Survey on Memory Subsystems for Deep Neural Network Accelerators. Future Internet 2022, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, Mohamed, Hossam Hawash, Nour Moustafa, Imran Razzak, and Mohamed Abd Elfattah. “Privacy-preserved learning from non-iid data in fog-assisted IoT: A federated learning approach. Digital Communications and Networks 2024, 10, 404–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; Bansal, M. BDD Ordering and Minimization Using Various Crossover Operators in Genetic Algorithm. Int. J. Innov. Res. Electr. Electron. Instrum. Control Eng. 2014, 2, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Thapa, C.; Afli, H.; Scully, T. Enabling All In-Edge Deep Learning: A Literature Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 3431–3460. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Wahid, S. A.; Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Quantum Computing Circuit Design: A Tutorial. Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Scientific Computing (ICASC), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2024; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

| Paper | Datasets Used |

| [3] | YaleB dataset. |

| [4] | Speech, Images collected from the peripheral devices. |

| OPP-115 Corpus dataset. | |

| [6] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [7] | Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer (WDBC) dataset. |

| [8] | PhysioNet BCI dataset (EEG). |

| [9] | Data was collected from the pacemaker used in the patient. |

| [10] | Dataset has 93200 posture images of 26 yoga postures. |

| [11] | MQTT-IoT_IDS-2020 dataset and NSL-KDD dataset. |

| [12] | Data was collected from the pacemaker used in the patient. |

| [13] | Images collected from the edge devices. |

| [14] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [15] | ICS Cyberattack Dataset and IoT Botnet Attack Dataset. |

| [16] | Custom data generated by authors. |

| [17] | No data was used. |

| [18] | Synthetic data from sleep monitor, nest camera, and WeMo switch. |

| [19] | Blood Glucose, weight and health assessment from smart phone and raspberry pi. |

| [20] | No dataset was used. |

| [21] | No dataset was used. |

| [22] | No dataset was used. |

| [23] | No dataset was used. |

| [24] | NA (the paper is a review). |

| [25] | Workshop data for six realistic IoT cases with location, personal information, and photos. |

| [26] | No dataset was used. |

| [27] | No dataset was used. |

| [28] | Three datasets were collected: a) Student activities time in the lab at the University of Genoa, b) Electrical values from household, and c) recorded gas r, humidity, and temperature sensor data. |

| [29] | No dataset was used. |

| [30] | No dataset was used. |

| [31] | NA (the paper is a review). |

| [32] | No dataset was used. |

| [33] | MNIST dataset. |

| [34] | No dataset was used. |

| [35] | Amazon dataset (2018). |

| [36] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [37] | MNIST dataset. |

| [38] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [39] | Private dataset of a three-day IoT traffic communication from a mobile network operator in China. |

| [40] | UCI activity data. |

| [41] | A private dataset was used. |

| Paper | Analytical Models Used |

| [3] | SVM, BFace, Privacy-preserving stochastic gradient descent-based algorithms, Private Aggregation of Teacher Ensembles (PATE). |

| [4] | Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) and leveraged machine learning classification methods for filtering. |

| [5] | Segment-based classification, Bag of words method. |

| [6] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [7] | CNN classification and ANN classification. |

| [8] | LSTM-EEG, Mahalanobis distance-based classification model (SEDP), magnitude squared coherence with the k-nearest neighbour algorithm (MSCKNN), Mahalanobis distance with spectral coherence features (SCCDP) and similar distance-based classification technique along with alpha-delta bands power features (ADPDP). |

| [9] | The paper presents a new taxonomy framework organizing all aspects of security and privacy baselines, guidelines, and recommendations. |

| [10] | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DNCC). |

| [11] | Normalization, SMOTE, Under Sampling for data preprocessing, Best First Search and Genetic Search for feature reduction, Naïve Bayes, AdaBoost, Bagging, J48 and Random Forest for classification. |

| [12] | The paper presents a new taxonomy framework organizing all aspects of security and privacy baselines, guidelines, and recommendations. |

| [13] | Autoencoder model for image dataset at each edge device and CNN Model for latent variables at the edge server. |

| [14] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [15] | Stacked deep learning architecture of five pretrained ResNet and meta-algorithm. |

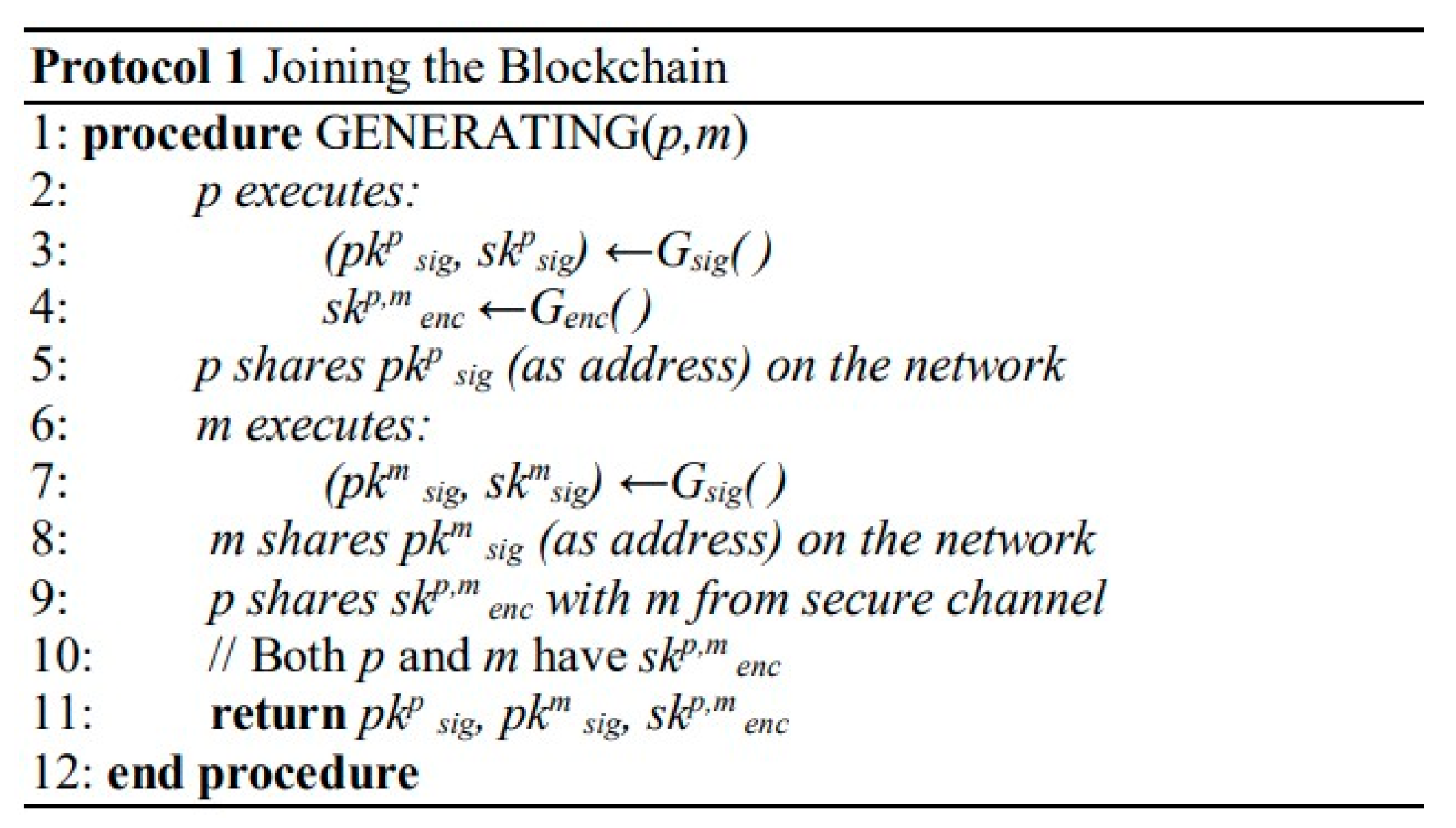

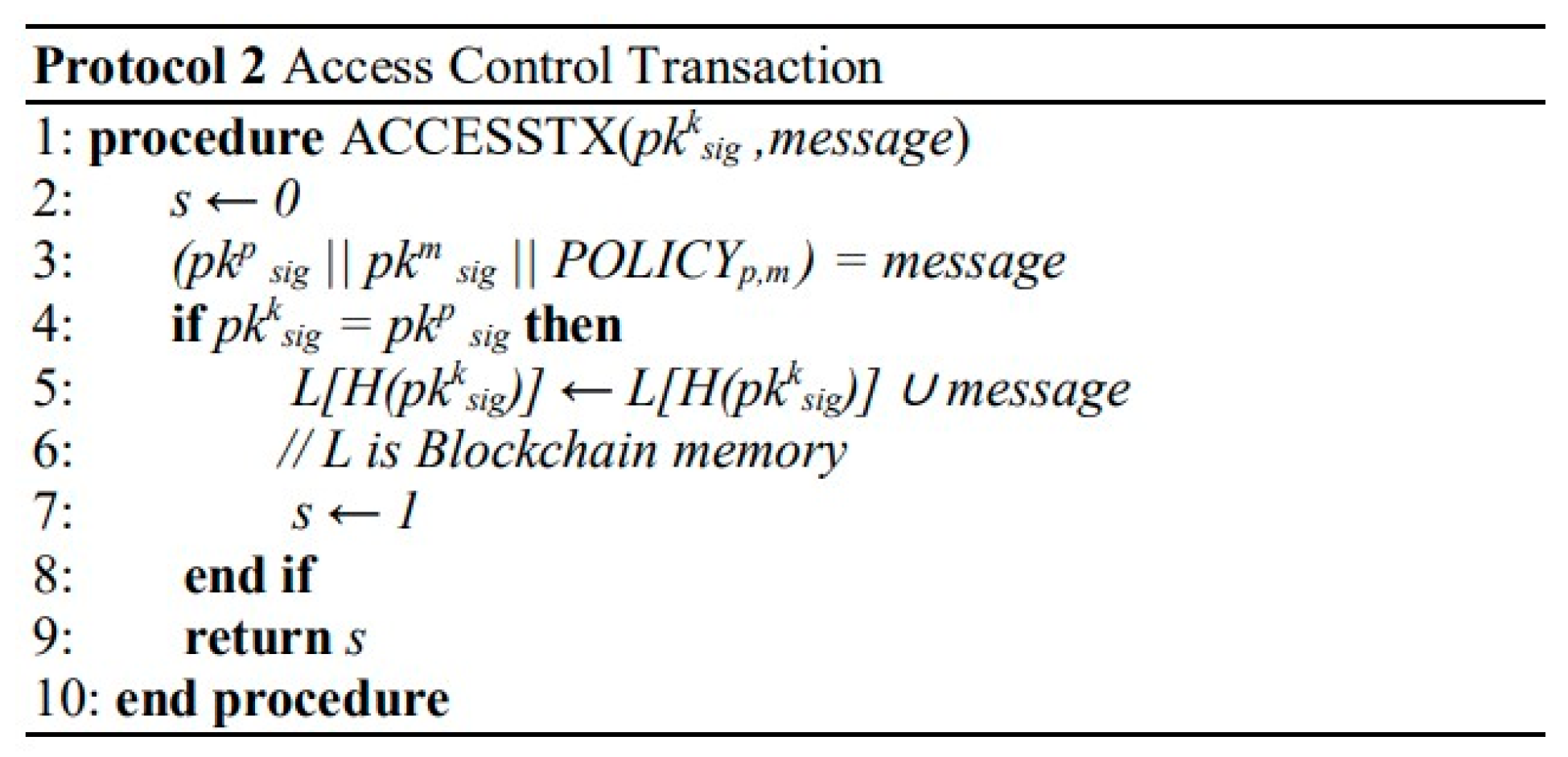

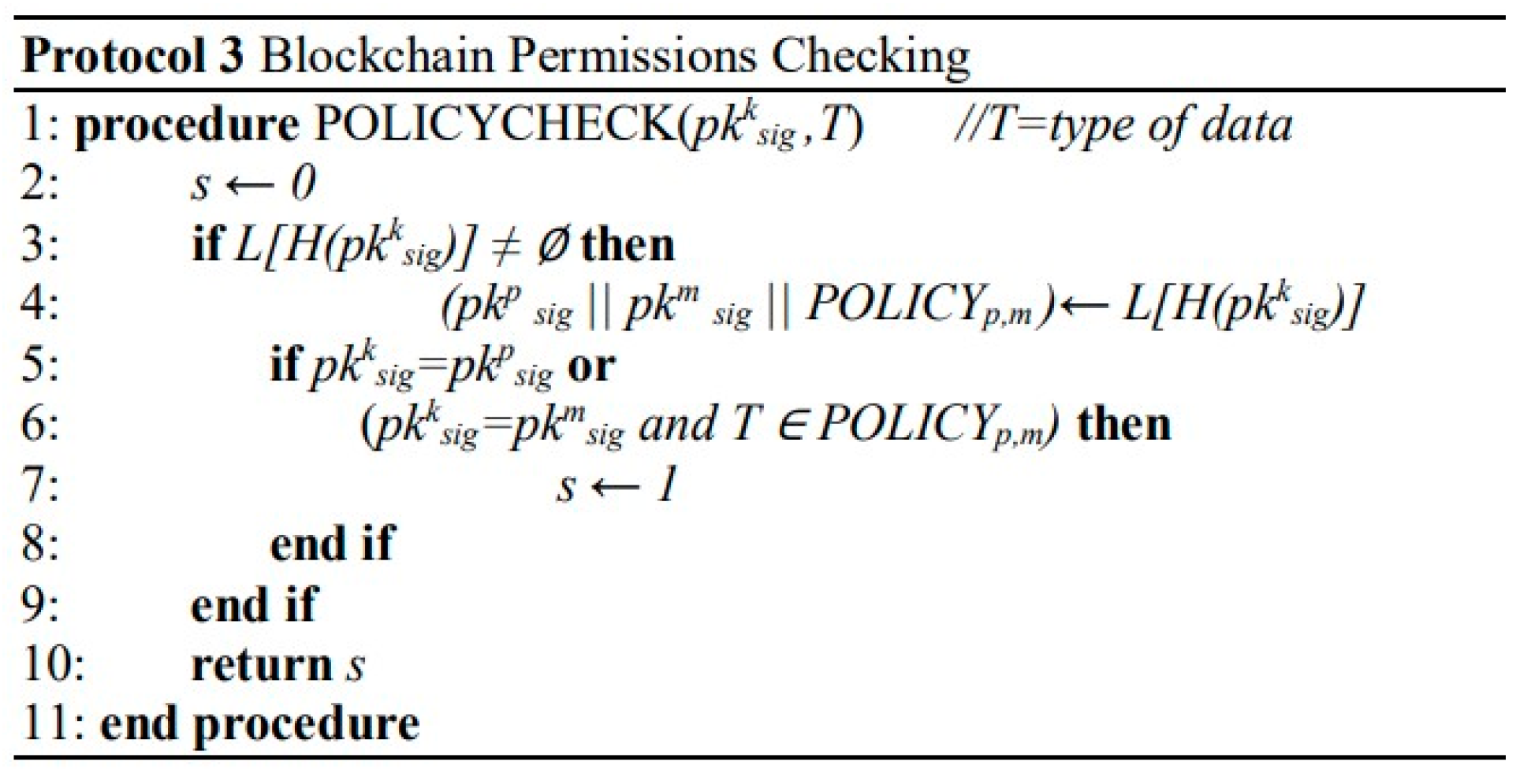

| [16] | Authentication and access control manager (AAM) protocol. |

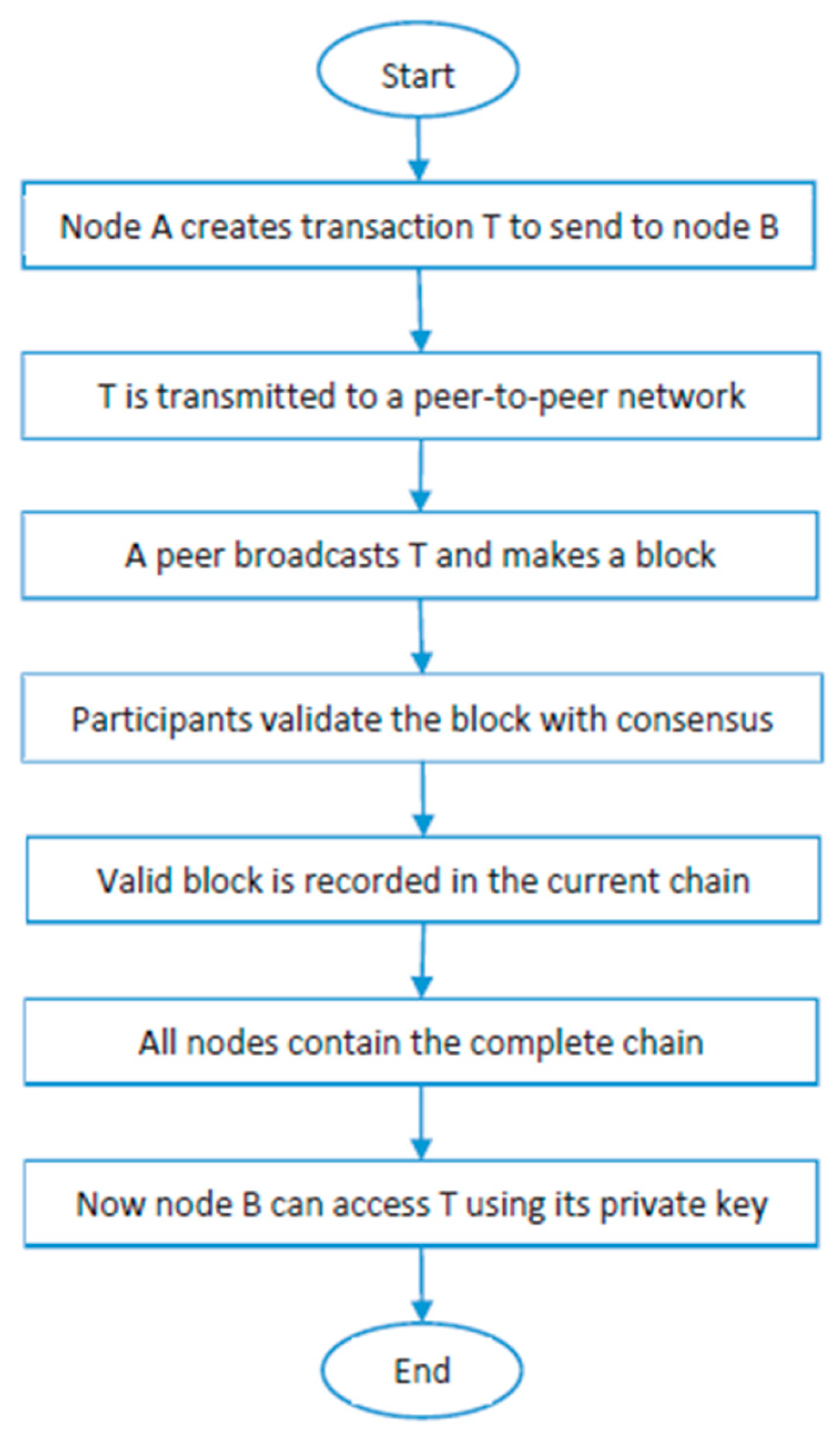

| [17] | Blockchain-based protocol for an efficient privacy-preserving access control method. |

| [18] | Event-level Adversary model, Traffic shaping Mechanisms. |

| [19] | Blockchain technology, Ethereum platform, Proof of Authority (PoA), InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). |

| [20] | Data Aggregation, Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) namely Intel SGX. |

| [21] | Blockchain technology, Ethereum platform, Smart Contracts. |

| [22] | Blockchain, IoT-based single-bit cache memory. |

| [23] | Federated Learning, Ethereum and Interplanar File Systems (IPFS). |

| [24] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [25] | PARROT ontology, Privacy by Design (PbD). |

| [26] | Blockchain, Raft Consensus algorithm. |

| [27] | Distributed application (DA) based on blockchain. |

| [28] | Hybrid met-heuristic algorithm, Grasshopper-Black Hole Optimization. |

| [29] | Edge-based computing, Signaling Q- learning game technique. |

| [30] | Edge-based IoT system, Evolutionary game-based model. |

| [31] | NA (the paper is a literature survey). |

| [32] | The fused Heuristic approach is termed the Elliptic Curve Cryptography Blockchain model. |

| [33] | Privacy-preserving trustworthy machine learning model training and sharing framework based on blockchain (PriModChain). |

| [34] | OPCECA. |

| [35] | Privacy-Preserving Cross-Domain Recommendation (PPCDR) algorithm. |

| [36] | The literature survey research directions for encryption protocols, software protection and sensor data loss. |

| [37] | Lightweight privacy-preserving federated learning (FedL). |

| [38] | The literature survey researched the current state of security and privacy of the IoT in the healthcare system. |

| [39] | The model generates privacy fingerprints from the IoT traffic flow, traffic block generation and sensitive marker selection. |

| [40] | Context-aware attribute learning scheme (CASE). |

| [41] | The model HASHA is proposed, which uses hash functions. |

| Feature Selection | Normalized Data (Set A) | Over-Sampled Data (Set B) | Under-Sampled Data (Set C) |

| Naive Bayes and Best search |

18.50% (3 out of 16) | 37.50% (6 out of 16) | 31.25% (5 out of 16) |

| Naive Bayes and Genetic Search |

37.50% (6 out of 16) | 43.75% (7 out of 16) | 37.50% (6 out of 16) |

| AdaBoost and Best First Search |

25.00% (4 out of 16) | 25.00% (4 out of 16) | 25.00% (4 out of 16) |

| AdaBoost and Genetic Search |

25.00% (4 out of 16) | Memory Exceed | 31.25% (5 out of 16) |

| Bagging and best first Search |

56.25% (9 out of 16) | Memory Exceed | 43.75% (7 out of 16) |

| Bagging and Genetic Search |

Memory Exceed | Memory Exceed | 50.00% (8 out of 16) |

| Feature Selection | Normalized Data (Set A) | Over-Sampled Data (Set B) | Under-Sampled Data (Set C) |

| Naive Bayes and Best search |

06.98% (3 out of 43) | 06.98% (3 out of 43) | 16.287% (7 out of 43) |

| Naive Bayes and Genetic Search |

39.53% (17 out of 43) |

34.88% (15 out of 43) |

37.21% (16 out of 43) |

| AdaBoost and Best First Search |

06.98% (3 out of 43) | 06.00% (3 out of 43) | 09.327% (4 out of 43) |

| AdaBoost and Genetic Search |

44.20% | 23.67% (10 out of 43) |

32.567% (14 out of 43) |

| Bagging and best first Search |

Memory Exceed | Memory Exceed | Memory Exceed |

| Bagging and Genetic Search |

Memory Exceed | 60.47% (26 out of 43) |

Memory Exceed |

| Preprocessing | Feature Selection | Classifier | Accuracy | Time (sec) |

| Normalization | AdaBoost & Best First Search | J48 | 99.86 | 2.81 |

| Over-Sampling & Normalization | AdaBoost & Best First Search | J48 | 99.85 | 5.40 |

| Under-Sampling & Normalization | Naïve Bayes & Genetic Search | J48 | 99.82 | 4.00 |

| Preprocessing | Feature Selection | Classifier | Accuracy | Time (sec) |

| Normalization | AdaBoost & Genetic Search | Bagging | 84.21 | 0.79 |

| Over-Sampling & Normalization | Bagging & Best First Search | Bagging | 84.35 | 0.32 |

| Under-Sampling & Normalization | AdaBoost & Genetic Search | Bagging | 83.80 | 0.36 |

| Paper | Strengths | Limitations |

| [3] | The Practical dataset YaleB is used. | The tradeoff between utility and privacy. |

| [4] | Prevent unwilling or unaware data leakage to untrusted third parties in clouds like Amazon or Google. | The tradeoff between performance, security, and privacy of the IoT-based systems. |

| [5] | Segment-based classification is effective for automated classification in privacy policies. | Accuracy is only 70%. |

| [6] | Shows that blockchain technology is effective for decentralization techniques. | Some semiautomatic systems require manual data log entry by patients, which limits flexible operations. |

| [7] | The triple DES encryption follows the AES algorithm and then a double DES encryption to prevent data leakage. | CNN classifiers create a big volume of synthetic data during training, requiring large storage for the data. The proposed IoMT architecture needs large hardware resources. |

| [8] | AI-enabled cybersecurity technology can protect individuals’ cognitive information and prevent violations of cognitive privacy. | The proposed LSTM-EEG model has 99.5% accuracy, which can lead to overfitting. |

| [9] | The proposed framework improves security significantly. | The only case study considered is a pacemaker functioning as a medical device communicating with its environment. |

| [10] | The proposed model is a novel approach to device-free privacy-preserving sensing technology. | -- |

| Low-resolution infrared sensor based WSN nodes are used, which might affect the image quality. | ||

| [11] | Use of MQTT-IoT_IDS-2020, which is the most recent IoT-specific network intrusion detection dataset and NSL-KDD, which is one of the most popular benchmark datasets for traditional network traffic. | For the MQTT-IoT_IDS-2020 dataset, the achieved accuracy is 99.86%, which might lead to overfitting. |

| [12] | The proposed framework improves security significantly. | The only case study considered is a pacemaker functioning as a medical device communicating with its environment. |

| [13] | Decoupling the training of the autoencoder and the edge server classifier lessens the frequent communication between them and yields improved privacy and security. | The tradeoff between classifier accuracy, data dimensionality compression ratio, and various choices of classifiers. |

| [14] | A systematic mapping study for privacy-preserving techniques in IoT systems. | Industrial IoT systems are not studied elaborately. |

| [15] | Better predictive performance than related approaches. | Lack of mentioned performance metrics and potential easy-to-learn dataset. |

| [16] | Resists common network security attacks, ideal for the IoT cloud infrastructure. | High computational time as responding to multiple requests takes a long time. |

| [17] | High resilience to various common attacks in the IoT environment. | Unavailable result as the model was not implemented. |

| [18] | Better handling of bursty traffic, better privacy-overhead tradeoffs. | Inefficient in hiding larger bursts of event packets. |

| [19] | Data Encryption, Integrity, Privacy, Access control, Confidentiality, and Resistance to attacks. | The current system designed is the web type and can be upgraded to real-time examination. |

| [20] | Better privacy in handling heterogeneous data. | The scheme is yet to be implemented for real-time IOT scenarios |

| [21] | Blockchain provides secure vehicular communication between vehicles and users by handling fake requests. | Latency and fault tolerance are not discussed. |

| [22] | Security issues in the cache are addressed, and power optimization techniques such as dual sleep, sleep transistor and forced stack are utilized. | Results are not compared with previous studies. |

| [23] | Improved security and privacy with satisfactory costs. | Real-time scenarios are not considered. |

| [24] | A complete examination of the blockchain technique is provided and classifies projecting issues that must be addressed. | Though the issues are classified in detail, slight emphasis is given to possible solutions. |

| [25] | Around 56% of questions were answered by the proposed technology. | The analysis is mainly carried out on only six use cases. Also, it does not report all the potential issues in these cases. |

| [26] | Transaction authentication is done in milliseconds. | The practical results of the technique are not included. |

| [27] | Better Latency, processing time, and response time than other existing schemes. | The work is limited to medical certificates and can be extended to prescriptions. |

| [28] | Higher security (more than 89% superiority) for industrial IoT applications than other schemes. | The model should be implemented for real-life cases. |

| [29] | Reduced probability of nasty requests from IoT nodes. | The real-life scenario is missing. |

| [30] | The proposed algorithm increases the projected revenue and yields the finest evolutionary approach. | The research work finds a rough equilibrium argument. |

| [31] | ||

| Makes an accurate assessment of privacy representations. Offers a method of privacy shield by data minimization. | The proposed method has not been implemented yet. | |

| [32] | Better grades of accuracy in comparison to other models. | Real-world application of the algorithm to health care networks is missing. |

| [33] | Combines differential privacy, federated ML, smart contracts, and blockchain. | High federation interval, 5 minutes for 5,000 tuples and 25 minutes for 60,000 tuples. |

| [34] | Capable of receiving artificial noise at both the transmitting and receiving nodes. | The model setup is antennas communicating with each other and not over the network. |

| [35] | Substantial increase in precision and recall compared to other proposed models. | The computational heavy model is composed of embeddings, CIN, DNN and AutoRec Training. |

| [36] | The literature survey focuses on creating complete security and privacy solutions for IoT systems, including various techniques. | The literature survey did not include any deep analysis of potential techniques and methods outlined. |

| [37] | Strong computation efficiency in online and offline phases, with linear time increase as the number of users increases. | Homomorphic encryption was used instead of other cryptographic encryption but requires high computational complexity. |

| [38] | The literature survey highlights novel solutions such as ML, DL, blockchain, SDN and more. | While the literature survey explored novel solutions, it did not include the results of such implementations. |

| [39] | Quantifiable IoT privacy leakage in mobile networks. | The dataset utilized potentially had easily selectable privacy-sensitive markers, which might not be accurate in the real world. |

| [40] | Reduces post-encryption data size compared to similar approaches. | The CASE model is scalable but has a linear increase in average network delay. |

| [41] | Provides location privacy against attacks through address anonymity. | It uses a lot of hashing algorithms; thus, it introduces additional computational overhead, especially for low-performance wireless sensor networks. |

| Paper | Research Gaps | Recommendations |

| [3] | The bloom filter encoding technique is non-reversible. | A parallel key-based data encryption system can compensate for the ‘reversibility’ of data backup. |

| [4] | The developed TEE model has small memory resources, whereas running complex ML models needs larger memory and generates additional overhead. | This gap can be minimized by minimizing TCB with lesser driver functions and smaller ML models. |

| [5] | The privacy policy is suitable for websites, but if it needs to be extended other than websites, this framework is not sufficient. | More data regarding privacy policies for IoT devices must be included, covering different fields. |

| [6] | Some semi-automatic systems require manual record logging. | In the future, semi-automatic systems can be upgraded into automatic by using sensors and wearable IoT devices. |

| [7] | The deep learning-based model needs powerful hardware and bigger RAM. Due to the large amount of synthetic data produced by CNN, large data storage is required, which is not adequately addressed. | The storage problem can be mitigated through cloud computing services. |

| [8] | The proposed model was developed based on the EEG data records from only 109 subjects. | In the future, a large volume of data should be used to validate the model’s performance. |

| [9] | Only a single case study is not enough to propose the taxonomy. | Elaborate studies covering different case studies are recommended. |

| [10] | The proposed novel model is developed based on 26 yoga postures only. | More data for yoga postures should be included in future studies for the robustness of the systems. |

| [11] | Nothing is mentioned in the study about handling data with significantly different values. | Outliers’ detection techniques can be included in the developed model. |

| [12] | Only a single case study is not enough to propose the taxonomy. | Elaborate studies covering different case studies are recommended. |

| [13] | The current comparison technique cannot quantify the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed model. | Comparison with federated learning and SplitNN can be done in future for classifier performance vs. communication cost and model complexity for image classification. |

| [14] | Industrial IoT systems are not studied elaborately. | In the future, privacy preservation techniques in industrial IoT systems should be included in the study. |

| [15] | Additional testing to reduce the computational overhead of the large model. | Addition of performance metrics to check for overfitting. |

| [16] | No testing of security threats other than common ones. | Further testing must be done to test other network security threats. |

| [17] | A comprehensive analysis of the resilience of various network attacks is needed. | Implementation of the model to determine computational overhead. |

| [18] | Difficulty in noting real-time cycle length and onset times during the design phase. | Shaper design efficiency can be improved by modelling the correlation of traffic input. |

| [19] | The current system designates a web category and can be upgraded to real-time patient examination. | The data can be filtered before being sent to the hospital, and Real-time investigation can be added. |

| [20] | Proof of concept for study for the methodology is yet to be implemented. | Security analysis of the proposed scheme can be carried out to bring strengths and limitations. |

| [21] | A comparison table regarding security and efficiency results to previous works is missing. | Simulation results for Proximity, Fault tolerance and latency can also be analyzed. |

| [22] | The power consumption and area overhead witness a trade-off. | This work can be utilized further in the array form. |

| [23] | There is a need to support the flexibility of federations. Pre-shared information must not be disclosed. | The technique can be expanded with RFID to comprehend automated on-chain identification. |

| [24] | Challenges and complications of blockchain technology need to be addressed. | Hybrid consensus protocols can be established by including speed, computational requirements, and other parameters. |

| [25] | The proposed solution is required to be tested for a broader set of areas. | A chatbot interface can be included further to enhance the interaction. |

| [26] | The prototype can be practically developed on a real-time dataset to generate strong results. | The proposed technique can be expanded to other finance systems. |

| [27] | Research can be done to achieve access control for mutual verification. | Government rules and standards can also be studied to produce certificates with stamps. |

| [28] | The model can be applied to broader applications in the industry. | The model can be utilized for other real-time applications. |

| [29] | The research work found an approximate value of the theoretic equilibrium. | The results obtained can be applied to real-world datasets. |

| [30] | Other game models can also be utilized to grip privacy protection. | Privacy protection for different IoT devices under data aggregation can be the next step with the proposed algorithm. |

| [31] | Experimental evaluation of the proposed method can be more specific. | The presentation of the proposed method can be examined and compared with previous methods. |

| [32] | Associations with healthcare workers can aid in reflecting legal and ethical contemplations. | The study of user involvement and usableness is a vital part of upcoming work for this technique. |

| [33] | The authors did not compare with other models for a baseline comparison. | Further testing different approaches to reduce latency and improve efficiency |

| [34] | The authors did not compare with other proposed models for comparison. | Further analysis with other proposed models for a better comparison. |

| [35] | The authors did not include the training time of the model. | Further testing to include more metric analysis for comparison with other proposed models and computational overhead. |

| [36] | The literature survey was too short and did not include a deep analysis of each research direction. | A deeper analysis of each research direction, comparing multiple models. |

| [37] | Further analysis into other methods that can balance privacy preservation and model performance. | Further analysis of other models is necessary to achieve lower time performance. |

| [38] | The literature survey had an in-depth knowledge of various state-of-the-art solutions, but it did not include further analysis of them. | The literature survey should include an example of how each state-of-the-art solution is applied in practice. |

| [39] | The results are unknown to be accurate as metrics are not included, or results are not compared with other models. | Extend the model to other datasets for further analysis. |

| [40] | The authors compared three different models: the NB, SVM and DT. All three models achieved mostly different accuracy, clock cycles and time response thus, further models need to be tested to achieve more uniform results. | Further analysis of other models that can achieve higher accuracy, but lower average clock cycles and average time is necessary for better performance. |

| [41] | The authors only compared the power consumption of their model with another routing algorithm but did not compare other analyses. | Further analysis with the compared routing algorithm for a better analytic comparison. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).