Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) imposes a substantial burden on patients due to its chronic, relapsing nature, often necessitating surgical intervention. However, surgery is not curative, and post-operative recurrence (POR) remains a major clinical challenge, with up to 80% of patients developing endoscopic recurrence within one year if left untreated. The pathophysiology of POR is multifactorial, involving dysregulated immune responses, gut microbiota alterations, and mucosal healing impairment, highlighting the need for targeted therapeutic strategies. This review aims to explore the current landscape of POR management, focusing on biologic therapies and emerging advanced treatments. Conventional management relies on early prophylactic therapy with anti-TNF agents such as infliximab and adalimumab, which have demonstrated efficacy in reducing endoscopic and clinical recurrence. However, newer biologics, including IL-23 inhibitors (risankizumab) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (upadacitinib), have shown promise in CD management, though their role in POR remains underexplored. The lack of direct clinical evidence for advanced biologics in POR prevention, combined with inter-individual variability in treatment response, underscores the need for further research. Future directions should focus on optimizing therapeutic strategies through personalized medicine, identifying predictive biomarkers, and conducting robust trials to establish the efficacy of novel agents in POR prevention. A tailored, evidence-driven approach is essential to improving long-term outcomes and minimizing disease recurrence in post-operative CD patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

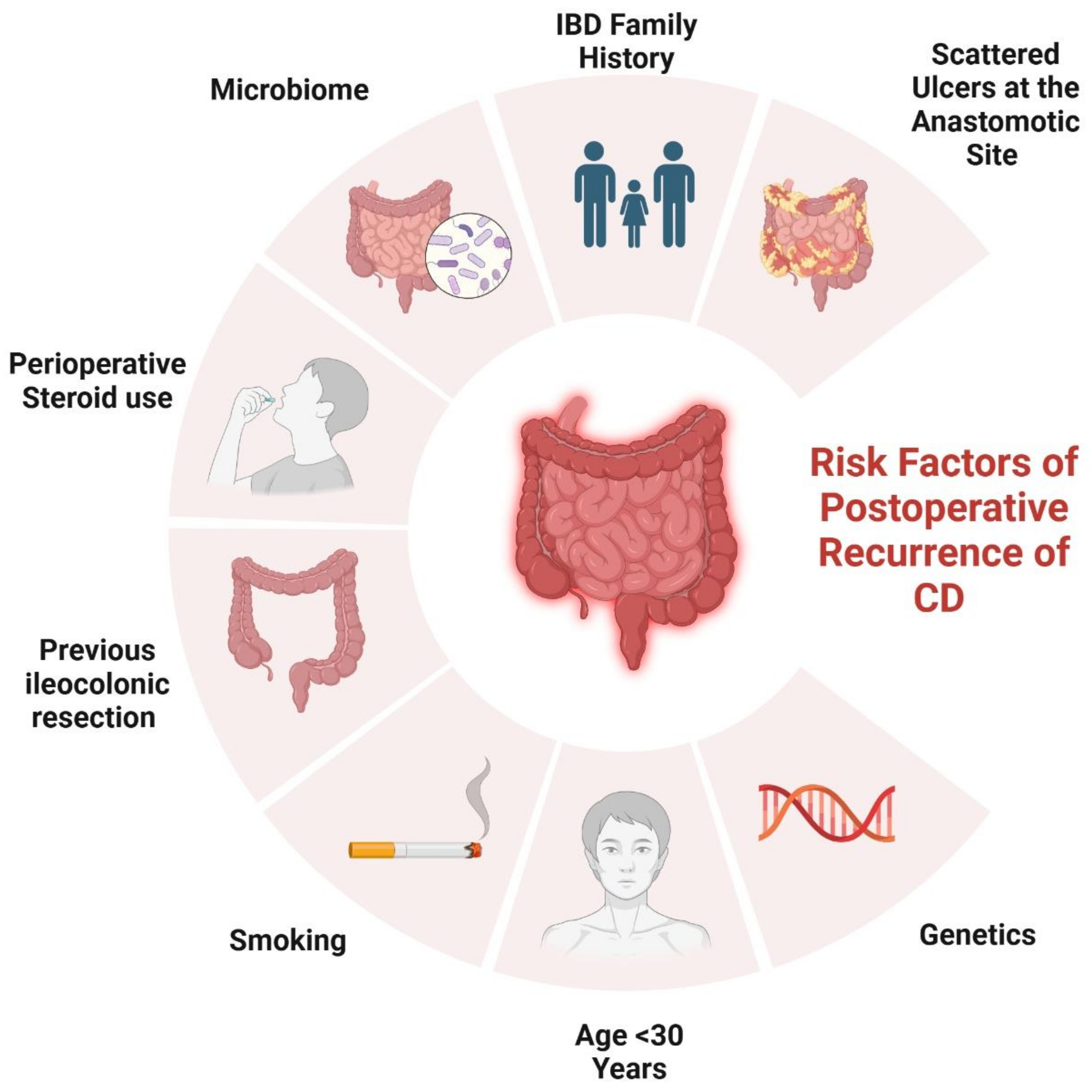

2. Risk Factors Contributing to POR

2.1. Genetical Factors

2.2. Surgical and Histological-Related Factors

2.3. Disease-Related Factors

2.4. Patient-Related Factors

3. Classification and Monitoring of Postoperative Recurrence

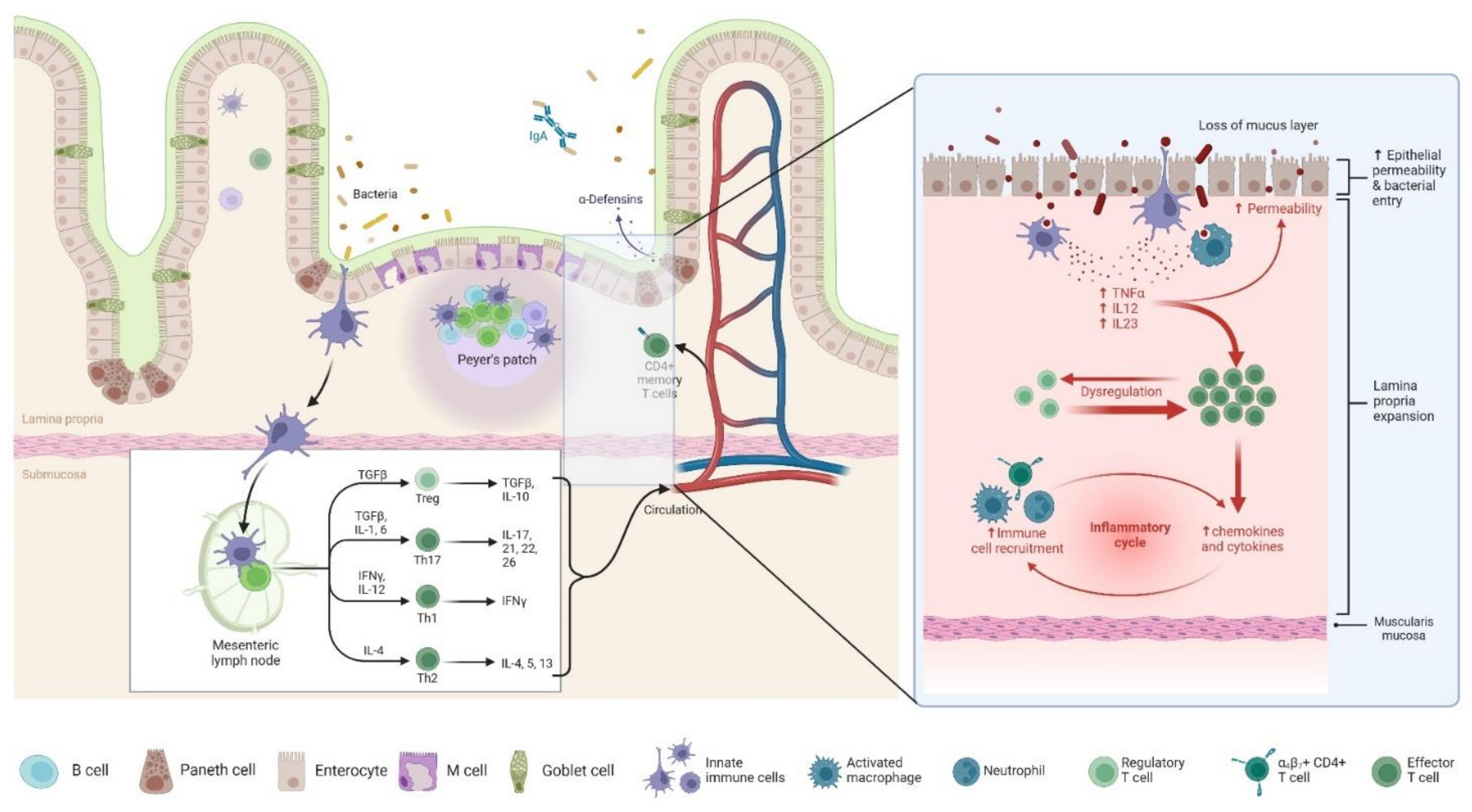

4. Pathophysiology of POR

5. Current Strategies and Guidelines of Prophylaxis

6. Traditional Biological Therapies

6.1. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Agents

6.2. Anti-Integrin and Anti-Interleukin Agents

7. Advanced Biologic Therapies

7.1. Upadacitinib

7.2. Risankizumab

8. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

8.1. Ongoing Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies

8.2. Personalized Medicine Approaches in Biologic Therapy Selection for POR

8.3. Potential Biomarkers for Predicting Response to Biologics in POR

9. Conclusions

References

- Ha F, Khalil H. Crohn’s disease: a clinical update. Therap Adv Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2015 Nov 16;8(6):352–9. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/.

- Ranasinghe IR, Tian C, Hsu R. Crohn Disease. In Treasure Island (FL); 2025.

- Carrière J, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Nguyen HTT. Infectious etiopathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep;20(34):12102–17.

- Kong L, Pokatayev V, Lefkovith A, Carter GT, Creasey EA, Krishna C, et al. The landscape of immune dysregulation in Crohn’s disease revealed through single-cell transcriptomic profiling in the ileum and colon. Immunity. 2023 Feb;56(2):444–458.e5.

- Meima-van Praag EM, Buskens CJ, Hompes R, Bemelman WA. Surgical management of Crohn’s disease: a state of the art review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021 Jun;36(6):1133–45.

- Chiarello MM, Pepe G, Fico V, Bianchi V, Tropeano G, Altieri G, et al. Therapeutic strategies in Crohn’s disease in an emergency surgical setting. World J Gastroenterol. 2022 May;28(18):1902–21.

- Toh JW, Stewart P, Rickard MJ, Leong R, Wang N, Young CJ. Indications and surgical options for small bowel, large bowel and perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Oct;22(40):8892–904.

- Luglio G, Kono T. Surgical Techniques and Risk of Postoperative Recurrence in CD: A Game Changer? Inflamm Intest Dis. 2022 Jan;7(1):21–7.

- Fasulo E, D’Amico F, Osorio L, Allocca M, Fiorino G, Zilli A, et al. The Management of Postoperative Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease. J Clin Med. 2023 Dec;13(1).

- Ma D, Li Y, Li L, Yang L. Risk factors for endoscopic postoperative recurrence in patients with Crohn’s Disease: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2024 Jun 25;24(1):211. Available online: https://bmcgastroenterol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12876-024-03301-z.

- Shah RS, Click BH. Medical therapies for postoperative Crohn’s disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2021 Jan 15;14. [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Murad MH, Scott FI, Agrawal M, Haydek JP, Limketkai BN, et al. Comparative Efficacy of Advanced Therapies for Management of Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis: 2024 American Gastroenterological Association Evidence Synthesis. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1;167(7):1460–82. [CrossRef]

- Economou M, Trikalinos TA, Loizou KT, Tsianos E V., Ioannidis JPA. Differential Effects of NOD2 Variants on Crohn’s Disease Risk and Phenotype in Diverse Populations: A Metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2004 Dec;99(12):2393–404. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00000434-200412000-00020.

- Renda MC, Orlando A, Civitavecchia G, Criscuoli V, Maggio A, Mocciaro F, et al. The Role of CARD15 Mutations and Smoking in the Course of Crohn’s Disease in a Mediterranean Area. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2008 Mar;103(3):649–55. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00000434-200803000-00024.

- Fowler SA, Ananthakrishnan AN, Gardet A, Stevens CR, Korzenik JR, Sands BE, et al. SMAD3 gene variant is a risk factor for recurrent surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2014 Aug;8(8):845–51. [CrossRef]

- Maconi G, Colombo E, Sampietro GM, Lamboglia F, D’Incà R, Daperno M, et al. CARD15 Gene Variants and Risk of Reoperation in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2009 Oct 28;104(10):2483–91. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00000434-200910000-00016.

- Meresse, B. Low ileal interleukin 10 concentrations are predictive of endoscopic recurrence in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut [Internet]. 2002 Jan 1;50(1):25–8. [CrossRef]

- Sehgal R, Berg A, Polinski JI, Hegarty JP, Lin Z, McKenna KJ, et al. Mutations in IRGM Are Associated With More Frequent Need for Surgery in Patients With Ileocolonic Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2012 Feb;55(2):115–21. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-201202000-00002.

- Germain A, Guéant RM, Chamaillard M, Bresler L, Guéant JL, Peyrin-Biroulet L. CARD8 gene variant is a risk factor for recurrent surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis [Internet]. 2015 Nov;47(11):938–42. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1590865815004193.

- Stocchi L, Milsom JW, Fazio VW. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: Follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery [Internet]. 2008 Oct;144(4):622–8. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0039606008004182.

- Eshuis EJ, Slors JFM, Stokkers PCF, Sprangers MAG, Ubbink DT, Cuesta MA, et al. Long-term outcomes following laparoscopically assisted versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg [Internet]. 2010 Mar 4;97(4):563–8. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/97/4/563/6150220.

- Patel S V, Patel SV, Ramagopalan S V, Ott MC. Laparoscopic surgery for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of perioperative complications and long term outcomes compared with open surgery. BMC Surg [Internet]. 2013 Dec 24;13(1):14. Available online: http://bmcsurg.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2482-13-14.

- Tichansky D, Cagir B, Yoo E, Marcus SM, Fry RD. Strictureplasty for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2000 Jul;43(7):911–9. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-200043070-00005.

- Reese GE, Purkayastha S, Tilney HS, Von Roon A, Yamamoto T, Tekkis PP. Strictureplasty vs resection in small bowel Crohn’s disease: an evaluation of short-term outcomes and recurrence. Color Dis [Internet]. 2007 Oct 21;9(8):686–94. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01114.x.

- Li Y, Stocchi L, Rui Y, Liu G, Gorgun E, Remzi FH, et al. Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Postoperative Outcome in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Undergoing Primary Ileocolonic Resection in the “Biological Era.” J Gastrointest Surg [Internet]. 2015 Oct;19(10):1842–51. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1091255X23033814.

- McLeod RS, Wolff BG, Ross S, Parkes R, McKenzie M. Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease After Ileocolic Resection Is Not Affected by Anastomotic Type. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2009 May;52(5):919–27. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-200905000-00009.

- Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Bertin E, Polese L, Filosa T, Prando D, et al. Surgical predictors of recurrence of Crohn’s disease after ileocolonic resection. Int J Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2007 Sep 30;22(9):1061–9. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00384-007-0329-4.

- Muñoz-Juárez M, Yamamoto T, Wolff BG, Keighley MRB. Wide-lumen stapled anastomosis vs. conventional end-to-end anastomosis in the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2001 Jan;44(1):20–5. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-200144010-00005.

- Simillis C, Purkayastha S, Yamamoto T, Strong SA, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP. A Meta-Analysis Comparing Conventional End-to-End Anastomosis vs. Other Anastomotic Configurations After Resection in Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2007 Oct;50(10):1674–87. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-200750100-00024.

- Kono T, Fichera A, Maeda K, Sakai Y, Ohge H, Krane M, et al. Kono-S Anastomosis for Surgical Prophylaxis of Anastomotic Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: an International Multicenter Study. J Gastrointest Surg [Internet]. 2016 Apr;20(4):783–90. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1091255X23064788.

- Fazio VW, Marchetti F, Church JM, Goldblum JR, Lavery IC, Hull TL, et al. Effect of Resection Margins on the Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease in the Small Bowel. Ann Surg [Internet]. 1996 Oct;224(4):563–73. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/00000658-199610000-00014.

- Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, Magro Dias FJ, Rogler G, Lakatos PL, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2017 Feb 1;11(2):135–49. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/11/2/135/2456548.

- Glass RE, Baker WN. Role of the granuloma in recurrent Crohn’s disease. Gut [Internet]. 1976 Jan 1;17(1):75–7. Available online: https://gut.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/gut.17.1.75.

- Chambers TJ, Morson BC. The granuloma in Crohn’s disease. Gut [Internet]. 1979 Apr 1;20(4):269–74. Available online: https://gut.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/gut.20.4.269.

- Malireddy K, Larson DW, Sandborn WJ, Loftus E V., Faubion WA, Pardi DS, et al. Recurrence and Impact of Postoperative Prophylaxis in Laparoscopically Treated Primary Ileocolic Crohn Disease. Arch Surg [Internet]. 2010 Jan 1;145(1). Available online: http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archsurg.2009.248.

- Simillis C, Jacovides M, Reese GE, Yamamoto T, Tekkis PP. Meta-analysis of the Role of Granulomas in the Recurrence of Crohn Disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2010 Feb;53(2):177–85. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-201002000-00011.

- Rahier JF, Dubuquoy L, Colombel JF, Jouret-Mourin A, Delos M, Ferrante M, et al. Decreased Lymphatic Vessel Density Is Associated With Postoperative Endoscopic Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2013 Sep;19(10):2084–90. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/19/10/2084-2090/4602989.

- Ferrante M, de Hertogh G, Hlavaty T, D’Haens G, Penninckx F, D’Hoore A, et al. The Value of Myenteric Plexitis to Predict Early Postoperative Crohn’s Disease Recurrence. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2006 May;130(6):1595–606. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016508506003362.

- Sokol H, Polin V, Lavergne-Slove A, Panis Y, Treton X, Dray X, et al. Plexitis as a predictive factor of early postoperative clinical recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Gut [Internet]. 2009 Sep 1;58(9):1218–25. Available online: https://gut.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/gut.2009.177782.

- Bressenot A, Chevaux JB, Williet N, Oussalah A, Germain A, Gauchotte G, et al. Submucosal Plexitis as a Predictor of Postoperative Surgical Recurrence in Crohnʼs Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2013 Jul;19(8):1654–61. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/19/8/1654-1661/4603086.

- Misteli H, Koh CE, Wang LM, Mortensen NJ, George B, Guy R. Myenteric plexitis at the proximal resection margin is a predictive marker for surgical recurrence of ileocaecal Crohn’s disease. Color Dis [Internet]. 2015 Apr 20;17(4):304–10. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/codi.12896.

- Decousus S, Boucher AL, Joubert J, Pereira B, Dubois A, Goutorbe F, et al. Myenteric plexitis is a risk factor for endoscopic and clinical postoperative recurrence after ileocolonic resection in Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis [Internet]. 2016 Jul;48(7):753–8. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1590865816000621.

- Lemmens B, de Buck van Overstraeten A, Arijs I, Sagaert X, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, et al. Submucosal Plexitis as a Predictive Factor for Postoperative Endoscopic Recurrence in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Undergoing a Resection with Ileocolonic Anastomosis: Results from a Prospective Single-centre Study. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2017 Feb;11(2):212–20. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw135.

- Sachar DB, Lemmer E, Ibrahim C, Edden Y, Ullman T, Ciardulo J, et al. Recurrence patterns after first resection for stricturing or penetrating Crohnʼs disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2009 Jul;15(7):1071–5. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/15/7/1071-1075/4643554.

- Avidan B, Sakhnini E, Lahat A, Lang A, Koler M, Zmora O, et al. Risk Factors Regarding the Need for a Second Operation in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Digestion [Internet]. 2005;72(4):248–53. Available online: https://karger.com/DIG/article/doi/10.1159/000089960.

- Simillis C, Yamamoto T, Reese GE, Umegae S, Matsumoto K, Darzi AW, et al. A Meta-Analysis Comparing Incidence of Recurrence and Indication for Reoperation After Surgery for Perforating Versus Nonperforating Crohn’s Disease. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2008 Jan;103(1):196–205. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00000434-200801000-00029.

- PASCUA M, SU C, LEWIS JD, BRENSINGER C, LICHTENSTEIN GR. Meta-analysis: factors predicting post-operative recurrence with placebo therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2008 Sep;28(5):545–56. [CrossRef]

- Han YM, Kim JW, Koh S, Kim BG, Lee KL, Im JP, et al. Patients with perianal Crohn’s disease have poor disease outcomes after primary bowel resection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2016 Aug 30;31(8):1436–42. [CrossRef]

- Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and recurrence in 907 patients with primary ileocaecal Crohn’s disease. J Br Surg [Internet]. 2000 Dec 1;87(12):1697–701. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/87/12/1697/6268590.

- Manser CN, Frei P, Grandinetti T, Biedermann L, Mwinyi J, Vavricka SR, et al. Risk Factors for Repetitive Ileocolic Resection in Patients with Crohnʼs Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2014 Sep;20(9):1548–54. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/20/9/1548-1554/4579123.

- Borley NR, Mortensen NJM, Chaudry MA, Mohammed S, Warren BF, George BD, et al. Recurrence After Abdominal Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2002 Mar;45(3):377–83. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-200245030-00012.

- Romberg-Camps MJL, Dagnelie PC, Kester ADM, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MAM, Cilissen M, Engels LGJB, et al. Influence of Phenotype at Diagnosis and of Other Potential Prognostic Factors on the Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2009 Feb 27;104(2):371–83. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00000434-200902000-00020.

- Keh C, Shatari T, Yamamoto T, Menon A, Clark MA, Keighley MR. Jejunal Crohn’s disease is associated with a higher postoperative recurrence rate than ileocaecal Crohn’s disease. Color Dis [Internet]. 2005 Jul;7(4):366–8. [CrossRef]

- Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, Prosberg M V., Bengtsson BG, Blixt T, Munkholm P, et al. Hospitalisation, surgical and medical recurrence rates in inflammatory bowel disease 2003–2011—A Danish population-based cohort study. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2014 Dec;8(12):1675–83. [CrossRef]

- Cottone M, Rosselli M, Orlando A, Oliva L, Puleo A, Cappello M, et al. Smoking habits and recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 1994 Mar;106(3):643–8. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0016508594906971.

- Unkart JT, Anderson L, Li E, Miller C, Yan Y, Charles Gu C, et al. Risk Factors for Surgical Recurrence after Ileocolic Resection of Crohn’s Disease. Dis Colon Rectum [Internet]. 2008 Aug;51(8):1211–6. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00003453-200851080-00004.

- Reese GE, Nanidis T, Borysiewicz C, Yamamoto T, Orchard T, Tekkis PP. The effect of smoking after surgery for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Colorectal Dis [Internet]. 2008 Dec 2;23(12):1213–21. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00384-008-0542-9.

- Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MRB. Smoking is a predictive factor for outcome after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis in patients with Crohn’s colitis. J Br Surg [Internet]. 1999 Aug 1;86(8):1069–70. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/86/8/1069/6269308.

- de Barcelos IF, Kotze PG, Spinelli A, Suzuki Y, Teixeira F V., de Albuquerque IC, et al. Factors affecting the incidence of early endoscopic recurrence after ileocolonic resection for Crohn’s disease: a multicentre observational study. Color Dis [Internet]. 2017 Jan 5;19(1). [CrossRef]

- Handler M, Dotan I, Klausner JM, Yanai H, Neeman E, Tulchinsky H. Clinical recurrence and re-resection rates after extensive vs. segmental colectomy in Crohn’s colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Tech Coloproctol [Internet]. 2016 May 17;20(5):287–92. [CrossRef]

- Polle SW, Slors JFM, Weverling GJ, Gouma DJ, Hommes DW, Bemelman WA. Recurrence after segmental resection for colonic Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg [Internet]. 2005 Aug 17;92(9):1143–9. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/bjs/article/92/9/1143/6144363.

- Nos P, Domenech E. Postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence: a practical approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Sep;14(36):5540–8.

- Rivière P, Bislenghi G, Vermeire S, Domènech E, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Laharie D, et al. Postoperative Crohn’s Disease Recurrence: Time to Adapt Endoscopic Recurrence Scores to the Leading Surgical Techniques. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1;20(6):1201–4. [CrossRef]

- Ble A, Renzulli C, Cenci F, Grimaldi M, Barone M, Sedano R, et al. The Relationship Between Endoscopic and Clinical Recurrence in Postoperative Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Mar;16(3):490–9.

- Spinelli A, Sacchi M, Fiorino G, Danese S, Montorsi M. Risk of postoperative recurrence and postoperative management of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Jul;17(27):3213–9.

- Dragoni G, Allocca M, Myrelid P, Noor NM, Hammoudi N, Rivière P, et al. Results of the eighth scientific workshop of ECCO: Diagnosing postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease after an ileocolonic resection with ileocolonic anastomosis. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2023;17(9):1373–86.

- Vespa E, Furfaro F, Allocca M, Fiorino G, Correale C, Gilardi D, et al. Endoscopy after surgery in inflammatory bowel disease: Crohn’s disease recurrence and pouch surveillance. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14(9):829–41.

- Furfaro F, D’Amico F, Zilli A, Craviotto V, Aratari A, Bezzio C, et al. Noninvasive Assessment of Postoperative Disease Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: A Multicenter, Prospective Cohort Study on Behalf of the Italian Group for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2023 Nov;21(12):3143–51.

- Xiong S, He J, Chen B, He Y, Zeng Z, Chen M, et al. A nomogram incorporating ileal and anastomotic lesions separately to predict the long-term outcome of Crohn’s disease after ileocolonic resection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2023 Jan 14;16. [CrossRef]

- Chongthammakun V, Fialho A, Fialho A, Lopez R, Shen B. Correlation of the Rutgeerts score and recurrence of Crohn’s disease in patients with end ileostomy. Gastroenterol Rep. 2017 Nov;5(4):271–6.

- Narula N, Wong ECL, Dulai PS, Marshall JK, Jairath V, Reinisch W. The Performance of the Rutgeerts Score, SES-CD, and MM-SES-CD for Prediction of Postoperative Clinical Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023 May;29(5):716–25.

- Gecse K, Lowenberg M, Bossuyt P, Rutgeerts PJ, Vermeire S, Stitt L, et al. Sa1198 Agreement Among Experts in the Endoscopic Evaluation of Postoperative Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease Using the Rutgeerts Score. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2014 May;146(5):S-227. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016508514608027.

- Rivière P, Pekow J, Hammoudi N, Wils P, De Cruz P, Wang CP, et al. Comparison of the Risk of Crohn’s Disease Postoperative Recurrence Between Modified Rutgeerts Score i2a and i2b Categories: An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2023 Mar 18;17(2):269–76. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/17/2/269/6702795.

- Domènech E, Mañosa M, Bernal I, Garcia-Planella E, Cabré E, Piñol M, et al. Impact of azathioprine on the prevention of postoperative Crohnʼs disease recurrence: Results of a prospective, observational, long-term follow-up study. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2008 Apr;14(4):508–13. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/14/4/508-513/4653666.

- Ollech JE, Aharoni-Golan M, Weisshof R, Normatov I, Sapp AR, Kalakonda A, et al. Differential risk of disease progression between isolated anastomotic ulcers and mild ileal recurrence after ileocolonic resection in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc [Internet]. 2019 Aug;90(2):269–75. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016510719300720.

- Rivière P, Vermeire S, Irles-Depe M, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, de Buck van Overstraeten A, et al. No Change in Determining Crohn’s Disease Recurrence or Need for Endoscopic or Surgical Intervention With Modification of the Rutgeerts’ Scoring System. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2019 Jul;17(8):1643–5. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1542356518310796.

- Hammoudi N, Auzolle C, Tran Minh ML, Boschetti G, Bezault M, Buisson A, et al. Postoperative Endoscopic Recurrence on the Neoterminal Ileum But Not on the Anastomosis Is Mainly Driving Long-Term Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2020 Jul;115(7):1084–93. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000638.

- Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 1990 Oct;99(4):956–63. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0016508590906136.

- Shah RS, Regueiro M, Cohen B, Mahadevan U. A Review on the Management of Postoperative Crohn’s Disease. Pract Gastroenterol. 2024;48(2):20–7.

- Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, Amiot A, Bossuyt P, East J, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2013 Dec;7(12):982–1018. [CrossRef]

- Bislenghi G, Vancoillie PJ, Fieuws S, Verstockt B, Sabino J, Wolthuis A, et al. Effect of anastomotic configuration on Crohn’s disease recurrence after primary ileocolic resection: a comparative monocentric study of end-to-end versus side-to-side anastomosis. Updates Surg. 2023;75(6):1607–15.

- Kann, B.R. Anastomotic considerations in Crohn’s disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2023;36(1):63–73.

- Scheurlen KM, Parks MA, Macleod A, Galandiuk S. Unmet Challenges in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. J Clin Med. 2023 Aug;12(17).

- De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Krejany EO, Gorelik A, et al. Crohn’s disease management after intestinal resection: a randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 2015 Apr;385(9976):1406–17.

- De Cruz P, Bernardi M, Kamm MA, Allen PB, Prideaux L, Williams J, et al. Postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: impact of endoscopic monitoring and treatment step-up. Color Dis. 2013;15(2):187–97.

- Nguyen GC, Loftus EVJ, Hirano I, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Crohn’s Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jan;152(1):271–5.

- Lichtenstein GR, Loftus E V, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2018;113(4):481–517.

- Allocca M, Dal Buono A, D’Alessio S, Spaggiari P, Garlatti V, Spinelli A, et al. Relationships Between Intestinal Ultrasound Parameters and Histopathologic Findings in a Prospective Cohort of Patients With Crohn’s Disease Undergoing Surgery. J Ultrasound Med [Internet]. 2023 Aug 6;42(8):1717–28. [CrossRef]

- Yung DE, Har-Noy O, Tham YS, Ben-Horin S, Eliakim R, Koulaouzidis A, et al. Capsule Endoscopy, Magnetic Resonance Enterography, and Small Bowel Ultrasound for Evaluation of Postoperative Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1;24(1):93–100. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/24/1/93/4757506.

- Schaefer M, Laurent V, Grandmougin A, Vuitton L, Bourreille A, Luc A, et al. A Magnetic Resonance Imaging Index to Predict Crohn’s Disease Postoperative Recurrence: The MONITOR Index. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2022 May;20(5):e1040–9. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1542356521006996.

- Yebra Carmona J, Poza Cordón J, Suárez Ferrer C, Martín Arranz E, Lucas Ramos J, Andaluz García I, et al. Correlación entre la endoscopia y la ecografía intestinal para la evaluación de la recurrencia posquirúrgica de la enfermedad de Crohn. Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2022 Jan;45(1):40–6. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0210570521000893.

- Macedo CP, Sarmento Costa M, Gravito-Soares E, Gravito-Soares M, Ferreira AM, Portela F, et al. Role of Intestinal Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Postsurgical Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: Correlation with Endoscopic Findings. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2022 May;29(3):178–86.

- Yebra Carmona J, Poza Cordón J, Suárez Ferrer C, Martín Arranz E, Lucas Ramos J, Andaluz García I, et al. Correlation between endoscopy and intestinal ultrasound for the evaluation of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol y Hepatol (English Ed [Internet]. 2022 Jan;45(1):40–6. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2444382421002339.

- Paredes JM, Ripollés T, Cortés X, Moreno N, Martínez MJ, Bustamante-Balén M, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography: Usefulness in the assessment of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2013 Apr;7(3):192–201. [CrossRef]

- Rispo A, Imperatore N, Testa A, Nardone OM, Luglio G, Caporaso N, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography in the Detection of Postsurgical Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2018 Apr 23;24(5):977–88. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/24/5/977/4982866.

- Connelly, T.M. Predictors of recurrence of Crohn’s disease after ileocolectomy: A review. World J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2014;20(39):14393. Available online: http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i39/14393.

- Azramezani Kopi T, Shahrokh S, Mirzaei S, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Amini Kadijani A. The role of serum calprotectin as a novel biomarker in inflammatory bowel diseases: a review study. Gastroenterol Hepatol from bed to bench. 2019;12(3):183–9.

- Lee YW, Lee KM, Lee JM, Chung YY, Kim DB, Kim YJ, et al. The usefulness of fecal calprotectin in assessing inflammatory bowel disease activity. Korean J Intern Med. 2019 Jan;34(1):72–80.

- Tham YS, Yung DE, Fay S, Yamamoto T, Ben-Horin S, Eliakim R, et al. Fecal calprotectin for detection of postoperative endoscopic recurrence in Crohn’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818785571.

- Boschetti G, Moussata D, Stefanescu C, Roblin X, Phelip G, Cotte E, et al. Levels of fecal calprotectin are associated with the severity of postoperative endoscopic recurrence in asymptomatic patients with Crohn’s disease. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2015;110(6):865–72.

- Lasson A, Strid H, Ohman L, Isaksson S, Olsson M, Rydström B, et al. Fecal calprotectin one year after ileocaecal resection for Crohn’s disease--a comparison with findings at ileocolonoscopy. J Crohns Colitis. 2014 Aug;8(8):789–95.

- Khakoo NS, Lewis A, Roldan GA, Al Khoury A, Quintero MA, Deshpande AR, et al. Patient adherence to fecal calprotectin testing is low compared to other commonly ordered tests in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn’s Colitis 360. 2021;3(3):otab028.

- D’Haens G, Kelly O, Battat R, Silverberg MS, Laharie D, Louis E, et al. Development and Validation of a Test to Monitor Endoscopic Activity in Patients With Crohn’s Disease Based on Serum Levels of Proteins. Gastroenterology. 2020 Feb;158(3):515–526.e10.

- Hamilton AL, De Cruz P, Wright EK, Dervieux T, Jain A, Kamm MA. Non-invasive Serological Monitoring for Crohn’s Disease Postoperative Recurrence. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Dec;16(12):1797–807.

- Sensi B, Siragusa L, Efrati C, Petagna L, Franceschilli M, Bellato V, et al. The Role of Inflammation in Crohn’s Disease Recurrence after Surgical Treatment. Cavaliere C, editor. J Immunol Res [Internet]. 2020 Dec 26;2020:1–14. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jir/2020/8846982/.

- D’Haens GR, Geboes K, Peeters M, Baert F, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P. Early lesions of recurrent Crohn’s disease caused by infusion of intestinal contents in excluded ileum. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 1998 Feb;114(2):262–7. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016508598704767.

- Sokol H, Brot L, Stefanescu C, Auzolle C, Barnich N, Buisson A, et al. Prominence of ileal mucosa-associated microbiota to predict postoperative endoscopic recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Gut [Internet]. 2020 Mar;69(3):462–72. [CrossRef]

- Zorzi F, Monteleone I, Sarra M, Calabrese E, Marafini I, Cretella M, et al. Distinct Profiles of Effector Cytokines Mark the Different Phases of Crohn’s Disease. Chamaillard M, editor. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2013 Jan 17;8(1):e54562. [CrossRef]

- Dang JT, Dang TT, Wine E, Dicken B, Madsen K, Laffin M. The Genetics of Postoperative Recurrence in Crohn Disease: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Framework for Future Work. Crohn’s Colitis 360 [Internet]. 2021 Apr 1;3(2). [CrossRef]

- Rivière P, Bislenghi G, Hammoudi N, Verstockt B, Brown S, Oliveira-Cunha M, et al. Results of the Eighth Scientific Workshop of ECCO: Pathophysiology and Risk Factors of Postoperative Crohn’s Disease Recurrence after an Ileocolonic Resection. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2023 Nov 8;17(10):1557–68. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/17/10/1557/7127328.

- Allez M, Auzolle C, Ngollo M, Bottois H, Chardiny V, Corraliza AM, et al. T cell clonal expansions in ileal Crohn’s disease are associated with smoking behaviour and postoperative recurrence. Gut [Internet]. 2019 Nov;68(11):1961–70. [CrossRef]

- Mineccia M, Maconi G, Daperno M, Cigognini M, Cherubini V, Colombo F, et al. Has the Removing of the Mesentery during Ileo-Colic Resection an Impact on Post-Operative Complications and Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease? Results from the Resection of the Mesentery Study (Remedy). J Clin Med [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1;11(7):1961. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/7/1961.

- Coffey CJ, Kiernan MG, Sahebally SM, Jarrar A, Burke JP, Kiely PA, et al. Inclusion of the Mesentery in Ileocolic Resection for Crohn’s Disease is Associated With Reduced Surgical Recurrence. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2018 Nov 9;12(10):1139–50. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/12/10/1139/4788815.

- de Bruyn JR, Bossuyt P, Ferrante M, West RL, Dijkstra G, Witteman BJ, et al. High-Dose Vitamin D Does Not Prevent Postoperative Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2021 Aug;19(8):1573–1582.e5. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1542356520306984.

- Ferrante M, Pouillon L, Mañosa M, Savarino E, Allez M, Kapizioni C, et al. Results of the Eighth Scientific Workshop of ECCO: Prevention and Treatment of Postoperative Recurrence in Patients With Crohn’s Disease Undergoing an Ileocolonic Resection With Ileocolonic Anastomosis. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2023 Nov 24;17(11):1707–22. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/17/11/1707/7127335.

- Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut [Internet]. 2019 Dec;68(Suppl 3):s1–106. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen GC, Loftus E V., Hirano I, Falck–Ytter Y, Singh S, Sultan S, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Crohn’s Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2017 Jan;152(1):271–5. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016508516352854.

- Joustra V, Duijvestein M, Mookhoek A, Bemelman W, Buskens C, Koželj M, et al. Natural History and Risk Stratification of Recurrent Crohn’s Disease After Ileocolonic Resection: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2022 Jan 5;28(1):1–8. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/28/1/1/6203395.

- Joustra V, van Sabben J, van der does de Willebois E, Duijvestein M, de Boer N, Jansen J, et al. Benefit of Risk-stratified Prophylactic Treatment on Clinical Outcome in Postoperative Crohn’s Disease. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2023 Apr 3;17(3):318–28. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/17/3/318/6702662.

- Dragoni G, Castiglione F, Bezzio C, Pugliese D, Spagnuolo R, Viola A, et al. Comparison of two strategies for the management of postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease patients with one clinical risk factor: A multicentre IG-IBD study. United Eur Gastroenterol J [Internet]. 2023 Apr 21;11(3):271–81. [CrossRef]

- Arkenbosch JHC, Beelen EMJ, Dijkstra G, Romberg-Camps M, Duijvestein M, Hoentjen F, et al. Prophylactic Medication for the Prevention of Endoscopic Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: a Prospective Study Based on Clinical Risk Stratification. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2023 Mar 18;17(2):221–30. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/17/2/221/6696306.

- Geldof J, Truyens M, Hanssens M, Van Gucht E, Holvoet T, Elorza A, et al. Prophylactic Versus Endoscopy-driven Treatment of Crohn’s Postoperative Recurrence: A Retrospective, Multicentric, European Study [PORCSE Study]. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2024 Aug 14;18(8):1202–14. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/18/8/1202/7578736.

- D’Amico F, Tasopoulou O, Fiorino G, Zilli A, Furfaro F, Allocca M, et al. Early Biological Therapy in Operated Crohn’s Disease Patients Is Associated With a Lower Rate of Endoscopic Recurrence and Improved Long-term Outcomes: A Single-center Experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2023 Apr 3;29(4):539–47. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/29/4/539/6594472.

- Sorrentino, D. Infliximab With Low-Dose Methotrexate for Prevention of Postsurgical Recurrence of Ileocolonic Crohn Disease. Arch Intern Med [Internet]. 2007 Sep 10;167(16):1804. Available online: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archinte.167.16.1804.

- Sorrentino D, Paviotti A, Terrosu G, Avellini C, Geraci M, Zarifi D. Low-Dose Maintenance Therapy With Infliximab Prevents Postsurgical Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2010 Jul;8(7):591–599.e1. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1542356510001163.

- Yoshida K, Fukunaga K, Ikeuchi H, Kamikozuru K, Hida N, Ohda Y, et al. Scheduled infliximab monotherapy to prevent recurrence of Crohnʼs disease following ileocolic or ileal resection: A 3-year prospective randomized open trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2012 Sep;18(9):1617–23. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/18/9/1617-1623/4607752.

- Araki T, Uchida K, Okita Y, Fujikawa H, Inoue M, Ohi M, et al. The impact of postoperative infliximab maintenance therapy on preventing the surgical recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a single-center paired case–control study. Surg Today [Internet]. 2014 Feb 6;44(2):291–6. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00595-013-0538-0.

- Regueiro M, Feagan BG, Zou B, Johanns J, Blank MA, Chevrier M, et al. Infliximab Reduces Endoscopic, but Not Clinical, Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease After Ileocolonic Resection. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2016 Jun;150(7):1568–78. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016508516002936.

- Papamichael K, Archavlis E, Lariou C, Mantzaris GJ. Adalimumab for the prevention and/or treatment of post-operative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: A prospective, two-year, single center, pilot study. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2012 Oct;6(9):924–31. [CrossRef]

- Aguas, M. Adalimumab in prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease in high-risk patients. World J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2012;18(32):4391. Available online: http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i32/4391.htm.

- Gangwani, M.K. Comparing adalimumab and infliximab in the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2023. Available online: http://www.annalsgastro.gr/files/journals/1/earlyview/2023/AnnGastroenterol-36-293-0786.pdf.

- Liu C, Li N, Zhan S, Tian Z, Wu D, Li T, et al. Anti -TNFα agents in preventing the postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: Do they still play a role in the biological era? Expert Opin Biol Ther [Internet]. 2021 Nov 2;21(11):1509–24. [CrossRef]

- Erős A, Farkas N, Hegyi P, Szabó A, Balaskó M, Veres G, et al. Anti-TNFα agents are the best choice in preventing postoperative Crohn’s disease: A meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis [Internet]. 2019 Aug;51(8):1086–95. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1590865819306280.

- Yamada A, Komaki Y, Patel N, Komaki F, Pekow J, Dalal S, et al. The Use of Vedolizumab in Preventing Postoperative Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2018 Feb 16;24(3):502–9. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/24/3/502/4863704.

- D’Haens G, Taxonera C, Lopez-Sanroman A, Nos Mateu P, Danese S, Armuzzi A, et al. OP14 Prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease with vedolizumab: First results of the prospective placebo-controlled randomised trial REPREVIO. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2023 Jan 30;17(Supplement_1):i19–i19. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/17/Supplement_1/i19/7009310.

- Buisson A, Nancey S, Manlay L, Rubin DT, Hebuterne X, Pariente B, et al. Ustekinumab is more effective than azathioprine to prevent endoscopic postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease. United Eur Gastroenterol J [Internet]. 2021 Jun 5;9(5):552–60. [CrossRef]

- Yanai H, Kagramanova A, Knyazev O, Sabino J, Haenen S, Mantzaris GJ, et al. Endoscopic Postoperative Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease After Curative Ileocecal Resection with Early Prophylaxis by Anti-TNF, Vedolizumab or Ustekinumab: A Real-World Multicentre European Study. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2022 Dec 5;16(12):1882–92. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/16/12/1882/6650750.

- Axelrad JE, Li T, Bachour SP, Nakamura TI, Shah R, Sachs MC, et al. Early Initiation of Antitumor Necrosis Factor Therapy Reduces Postoperative Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease Following Ileocecal Resection. Inflamm Bowel Dis [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1;29(6):888–97. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ibdjournal/article/29/6/888/6651946.

- Mañosa M, Fernández-Clotet A, Nos P, Martín-Arranz MD, Manceñido N, Carbajo A, et al. Ustekinumab and vedolizumab for the prevention of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease: Results from the ENEIDA registry. Dig Liver Dis [Internet]. 2023 Jan;55(1):46–52. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1590865822006181.

- Loftus EVJ, Panés J, Lacerda AP, Peyrin-Biroulet L, D’Haens G, Panaccione R, et al. Upadacitinib Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023 May;388(21):1966–80.

- Wu H, Xie T, Yu Q, Su T, Zhang M, Wu L, et al. An Analysis of the Effectiveness and Safety of Upadacitinib in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Multicenter Real-World Study. Biomedicines. 2025 Jan;13(1).

- Farkas B, Bessissow T, Limdi JK, Sethi-Arora K, Kagramanova A, Knyazev O, et al. Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Selective JAK Inhibitors in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: A Retrospective, Multicentre Study. J Clin Med. 2024 Dec;13(24).

- García MJ, Brenes Y, Vicuña M, Bermejo F, Sierra-Ausín M, Vicente R, et al. Persistence, Effectiveness, and Safety of Upadacitinib in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Real Life: Results From a Spanish Nationwide Study (Ureal Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Nov.

- Bezzio C, Franchellucci G, Savarino E V, Mastronardi M, Caprioli FA, Bodini G, et al. Upadacitinib in Patients With Difficult-to-Treat Crohn’s Disease. Crohn’s colitis 360. 2024 Oct;6(4):otae060.

- Cohen S, Spencer EA, Dolinger MT, Suskind DL, Mitrova K, Hradsky O, et al. Upadacitinib for Induction of Remission in Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: An International Multicentre Retrospective Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025 Feb.

- Runde J, Ryan K, Hirst J, Lebowitz J, Chen W, Brown J, et al. Upadacitinib is associated with clinical response and steroid-free remission for children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025 Jan;80(1):133–40.

- Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens G, Panés J, Kaser A, Ferrante M, et al. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23 inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet [Internet]. 2017 Apr;389(10080):1699–709. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673617305706.

- Feagan BG, Panés J, Ferrante M, Kaser A, D’Haens GR, Sandborn WJ, et al. Risankizumab in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: an open-label extension study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2018 Oct;3(10):671–80. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2468125318302334.

- Ferrante M, Feagan BG, Panés J, Baert F, Louis E, Dewit O, et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Risankizumab Treatment in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: Results from the Phase 2 Open-Label Extension Study. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2021 Dec 18;15(12):2001–10. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/15/12/2001/6291316.

- D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Baert F, Bossuyt P, Colombel JF, Danese S, et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet [Internet]. 2022 May;399(10340):2015–30. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673622004676.

- Bossuyt P, Ferrante M, Baert F, Danese S, Feagan BG, Loftus Jr E V, et al. OP36 Risankizumab therapy induces improvements in endoscopic endpoints in patients with Moderate-to-Severe Crohn’s Disease: Results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE studies. J Crohn’s Colitis [Internet]. 2021 May 27;15(Supplement_1):S033–4. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/15/Supplement_1/S033/6286077.

- Ferrante M, Panaccione R, Baert F, Bossuyt P, Colombel JF, Danese S, et al. Risankizumab as maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease: results from the multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase 3 FORTIFY maintenance trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2022 May;399(10340):2031–46. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673622004664.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study Comparing Intravenous (IV)/Subcutaneous (SC) Risankizumab to IV/SC Ustekinumab to Assess Change in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) in Adult Participants With Moderate to Severe Crohn’s Disease (CD) (SEQUENCE) [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04524611.

- AbbVie News Center. AbbVie’s SKYRIZI® (Risankizumab) Met All Primary and Secondary Endpoints Versus Stelara® (Ustekinumab) in Head-To-Head Study in Crohn’s Disease. [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://news.abbvie.com/news/press-releases/abbvies-skyrizi-risankizumab-met-all-primary-and-secondary-endpoints-versus-stelara-ustekinumab-in-head-to-head-study-in-crohns-disease.htm.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).