1. Introduction

The meticulous recognition of artifacts in CT imaging is an indispensable aspect in clinical diagnosis and treatment planning. CT scans provide invaluable anatomical information that is essential for effective therapeutic interventions, empowering clinicians to delve comprehensively into the disease manifestations uncovered by radiologic signs and explore the interior pathophysiological mechanisms associated. However, the artifacts can considerably obfuscate image interpretation, compromising the diagnostic process. These artifacts are aberrant visualizations that mainly resulting from diverse factors, including scanner-based issues, physics-based effects, patient-specific influences, as well as helical and multisection techniques [

1]. Manifesting as streaking, shading, rings, and distortion, these artifacts can globally or locally obscure crucial anatomical details or mimic pathological findings [

2]. To tackle these artifact confusions, contemporary scanners have integrated state-of-the-art technologies that are specifically tailored to mitigate the disadvantage. While these sophisticated algorithms demonstrate significant improvements, they often entail considerable time consuming and prone to interobserver variability. Hence, the demand for robust and efficient methodologies that can streamline the artifact optimization is escalating evident.

Deep learning methods have progressively exhibited their potential as viable alternatives for artifact reduction. In recent advancements, supervised learning strategy has been thoroughly explored, harnessing extensive CT imaging datasets with artifacts and their corresponding human annotations, to train deep learning models explicitly in an end-to-end mode. Leveraging a dataset including artifact images and the multiple corresponding annotations, a previous work [

3] presented a novel supervised detection method to screen for common imaging appearances of the artifact such as rings, streaks and bands. However, the complex imaging artifact challenge remains largely unexplored in relevant studies due to the combined difficulties of medical data scarcity and the prohibitive expenses of human annotations, which require excessive time and expertise. To alleviate this data hurdle, some supervised methods trained with labeled synthetic-artifact CT images, which can potentially induce a biased feature fitting process [

4]. Aligning with these circumstances, some studies [

4,

5] introduced analogous semi-supervised strategies to exploit the imaging representations in both image domain and latent feature space, achieving notable experimental results along with considerable robustness.

Unsupervised deep learning methods have been extensively utilized in the medical image translation tasks, proving to be highly effective solutions [

6,

7,

8,

9] for alleviating artifacts through the synthesis of target imaging representation under guidance from an acquired source. In this situation, unsupervised methods rooted in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) tend to learn the mapping from artifact-contaminated images to their artifact-free counterparts. To eliminate the rigid constraint of paired images (requiring pixel-to-pixel correspondence), CycleGAN [

10] was proposed with a cycle consistency scheme, enabling the training mode for unpaired data. Despite overcoming the paired constraint, this method demands numerous training iterations and grapples with instability issues [

11]. A recent study [

12] has employed the cycle consistency loss and further refined it by incorporating a feature-based domain loss, allowing for a better fitting performance of the feature disparity between the synthesized and the target domains. While formidable in generative ability, these methods implicitly represent the distribution of the target domain through a dynamic computation between generator and discriminator that, in a way, relatively undermines the factor of probability assessment [

13]. In most cases, the source and target domains exhibit remarkable disparities in feature diversity and information entropy, leading to a range of issues including inadequate generations, unclear mappings, and degraded model performance. To optimize the alignment of generated images in unpaired image-to-image translation task, the AttentionGAN [

14] achieves high-quality generations in the target domain by fusing the attention masks produced by the attention-guided generators. AttentionGAN reinforces the desired foreground while mitigating changes in the background, leading to the generation of sharper and more realistic images.

While GANs possess the capability to synthesis extensive datasets with ease, they often suffer from limitations in terms of heterogeneity and verisimilitude. Nevertheless, this limitation has been recently alleviated by the advent of denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) [

15,

16], showcasing their effectiveness in processing natural images. Regarding medical imaging, previous research [

17] has shown that Medfusion, a conditional latent DDPM method, is more effective than GANs at synthesizing high-quality medical images. In most cases, diffusion models typically have slow sampling speeds, requiring numerous iterations to synthesize from purely Gaussian noise. Initializing the process with an optimized single forward diffusion can drastically decrease the sampling steps in the reverse process. [

18]. To reduce the memory consuming, some studies [

17,

19,

20] conduct the diffusion training within the latent space of high-performance pretrained autoencoders, allowing a marked simplification and preservation of anatomical detail. Focusing on image translation, Saharia et al., [

21] introduced Palette, a dual-domain Markov chain diffusion model which can perform various image-to-image translation tasks without the need for adversarial constraints. Furthermore, the optimization of artifacts in medical imaging can be likened to a translation process, where the artifact-contaminated image is transformed into a clearer one. Relevant research [

22] presented a diffusion model with robust data distribution representation capability, designed to reduce metal artifacts. They argued that the prevalent comparable approaches typically rely on single-domain processing, whether in the image or sinogram domain, ultimately leading to the neglect of degraded regions caused by metal artifacts. Peng et al., [

23] developed a conditional diffusion model specifically tailored to improve image quality by translating cone-beam CT scans into the CT domain. They employed a time-embedded U-Net architecture incorporating residual and attention blocks to progressively transform standard Gaussian noise into the target CT distribution, conditioned on cone-beam CT images, and training was conducted with pairs of deformed planning CT and cone-beam CT images. CoreDiff [

24] was introduced for denoising low-dose CT images by simulating degradation and reducing errors with CLEAR-Net. Additionally, a one-shot learning framework enabled CoreDiff to rapidly adapt to new dose levels with minimal resources. Li et al. proposed the Conditional Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (c-DDPM) [

25], which represents a significant advance in Ultra-Low Dose CT (ULDCT) image enhancement. By leveraging a 2.5D feature fusion strategy and constrained denoising, c-DDPM effectively suppresses artifacts, improves image quality, and facilitates more accurate lung nodule detection compared to existing methods.

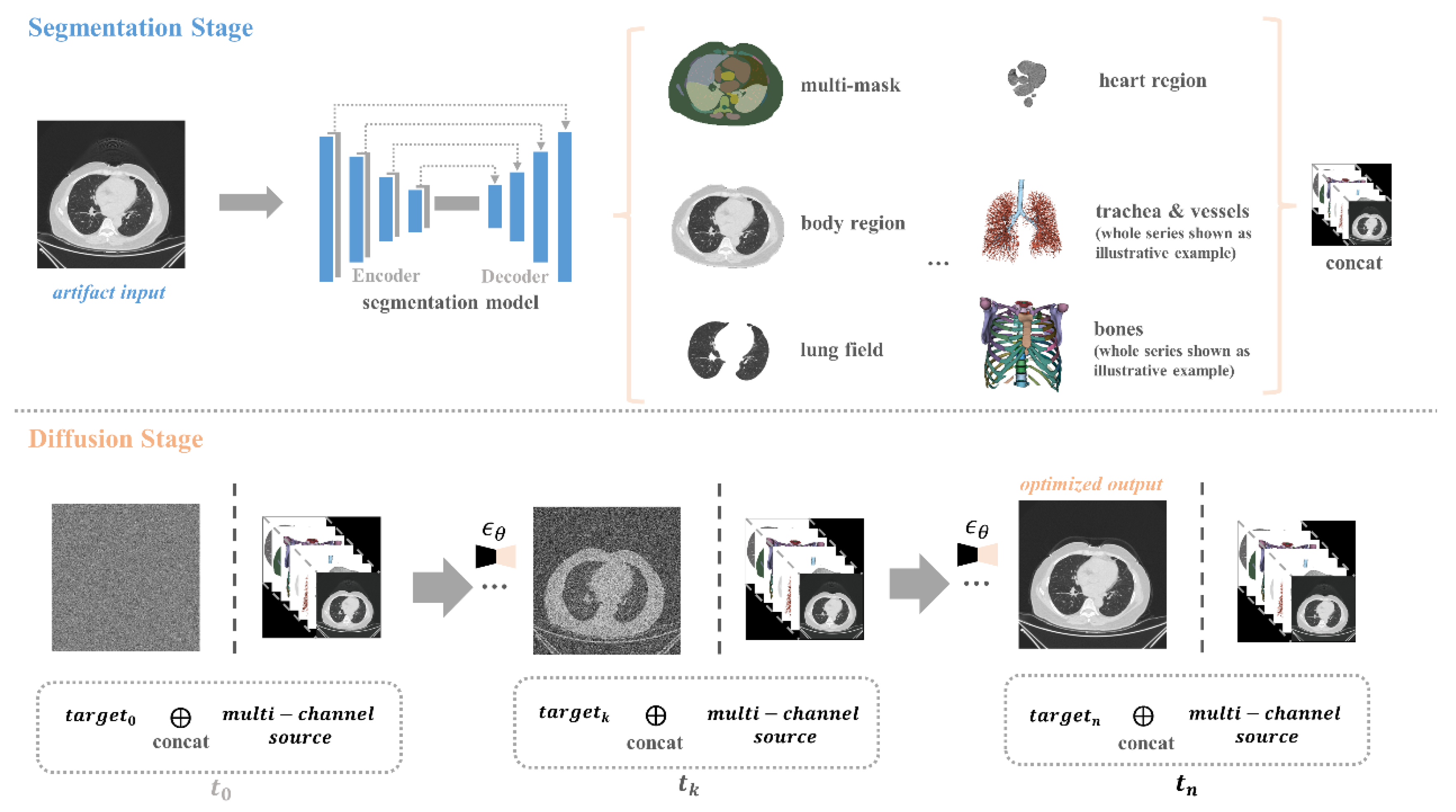

In this work, we introduced a novel guided diffusion method aimed at optimizing streaking artifact reduction in routine non-contrast chest CT. Recognizing the need to retain imaging details for clinical purposes and to achieve cross-domain consistency in diffusion output, we developed a deep learning model proficient in multi-class segmentation that is adept at identifying over 30 classes of anatomical tissue in chest CT scans. For diffusion guidance in the training process, we concatenated artifact-free CT images, segmentation masks, and corresponding anatomical ROIs including lungs, heart, vessels, trachea, bones, and body to preserve anatomical structures throughout every diffusion step. At the artifact reduction phase, the well-trained diffusion model converted the image contaminated with artifacts to an artifact-free image. The invariant anatomical sub-structures inherited in chest CT scans served as the core carrier of our idea, guiding the generation of artifact-free output while preserving the original anatomical consistency.

The performance of our method was evaluated from two aspects: artifact reduction effectiveness and anatomical preservation. Firstly, we applied CycleGAN to the artifact-free samples and transformed them into their artifact counterparts. These altered samples were then processed by our segmentation-guided diffusion model. Following this, we leveraged PSNR and SSIM to calculate the signal distortion and structural similarity between the original artifact-free samples and the corresponding diffusion outputs. Additionally, to objectively assess anatomical preservation, we employed the model from the previous segmentation stage to compute the DSC score between segmentations on the artifact samples and their artifact-free diffusion outputs. After applying our method, the generated images showed a notable decrease in streaking artifacts and high overall consistency with the actual artifact-free samples in terms of both SNR and CNR. Furthermore, the high DSC consistency proved that diffusion outputs retained original anatomical details with fine granularity. Overall, the method is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diffusion Models

In the field of medical imaging, style transfer poses a significant challenge, particularly when it comes to converting images contaminated with artifacts into their artifact-free counterparts. It is imperative that such transformations preserve intricate details of the original image while effectively reducing the artifacts. Our proposed method, based on guided diffusion models, aims to achieve this delicate balance.

Our method lies a detail-preserving artifact reduction technique that leverages diffusion models [

15,

16], specifically tailored to the formulations of DDPMs. Diffusion models operate by generating a set of noisy images {

} from an input image

. This is achieved by incrementally infusing minor noise over numerous timesteps

, gradually increasing the noise level

of an image

in

T steps. We employ a U-Net architecture, which is trained to predict the denoised image

from

at each step following Equation 5. During the training phase, we have access to the ground truth for

, and our model is opitimized using a mixed loss function that combines Mean Squared Error (MSE) with structural constraints imposed by the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM). This ensures that both the pixel-wise accuracy and the structural integrity of the images are maintained throughout the denoising process. In the prediction phase, we start with the

and iteratively denoise it, predicting

with

at each step. This iterative process eventually generates a fake, artifact-free image

. The forward noising process

, which is characterized by variances

and described by Equation 1 and Equation 2, gradually corrupts an image with introduced noise

, approaching a Gaussian distribution as the noise level increases:

where

indicates the maximum step and

. The recursive relationship can be explicitly formulated as:

where

,

. The image denoising, denoted by

, involves optimizing the trainable parameters

through a training procedure and is subsequently defined as:

where

represent the denoised network and

depends on

, with

being the set of parameters. The MSE loss between the denoised and ground truth images is calculated as :

And the SSIM loss for

in the images is described as Eq 7., where

and

represent the means of the ground truth and denoising image, respectively,

and

denote the corresponding variances :

We leverage the formulations of DDPMs to predict the denoised image

from the noisier representation

:

It is worth highlighting that DDPMs introduce a stochastic element ϵ at each sampling step, providing flexibility and diversity in the generated images. Viewing the denoising process as solving an ordinary differential equation (ODE) using the Euler method, we can reverse the generation process by employing the reversed ODE. By discretizing the process into sufficient steps, we diffuse the given image

into a noisy representation

, for

:

At the final stage of the forward diffusion process, we acquire a fully noised image

from

. Subsequently, we recover the identical artifact-free

from the noisy

applying Equation 9 for each

with

. During prediction, we define a noise level

and a gradient scale

to control the denoising process. Crucially, our method incorporates a self-supervised pre-training to differentiate between artifact and artifact-free samples for the denoising U-Net encoder. This emphasizes that only the artifact regions are selectively targeted for modification, while the unaffected regions remain preserved. Additionally, we utilize the original image along with multiple segmentations of organ tissue as conditional inputs to further refine the denoising process. Through the integration of conditional segmentation maps, classifier-guided regularization, and a hybrid loss function, our method enables precise artifact mitigation and high-fidelity image reconstruction. The iterative noising-denoising algorithm is detailed in

Table 1.

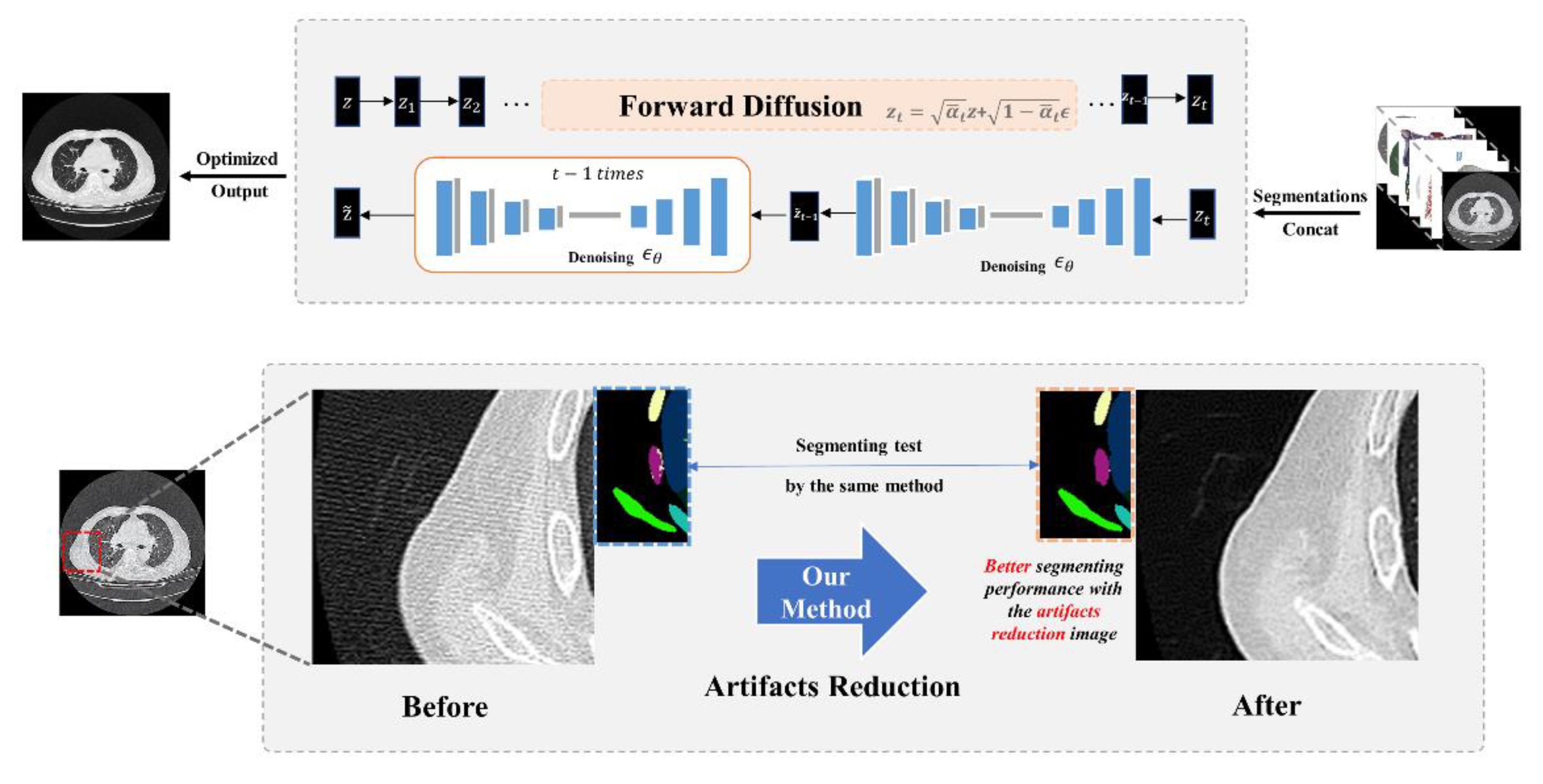

2.2. Segmentation Guided Diffusion

Addressing the domain-invariant issue, we introduce a well-trained U-Net for various an atomical segmentations, serving as further guidance for the diffusion stage. We concatenate the segmentation mask of over 30 classes, the corresponding anatomical components mapped by the mask, and the original CT slice into a multi-channel tensor ( is the number of classes).

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 1, we first leverage the U-Net model

Seg to acquire the segmentation mask and complete the concatenation as an n-channel guidance tensor

for each denoising step. According this, the neural network can be defined as

, and the modified loss based on Equation 6 is given as:

Segmentation guidance operates by enforcing structural constraints on anatomical structures, ensuring their spatial-temporal consistency and topological integrity throughout the diffusion process under artifact perturbation. This constraint-driven regularization preserves fine-grained anatomical details while neutralizing artifact-induced degradations, thereby guaranteeing structurally intact and diagnostically reliable image reconstruction.

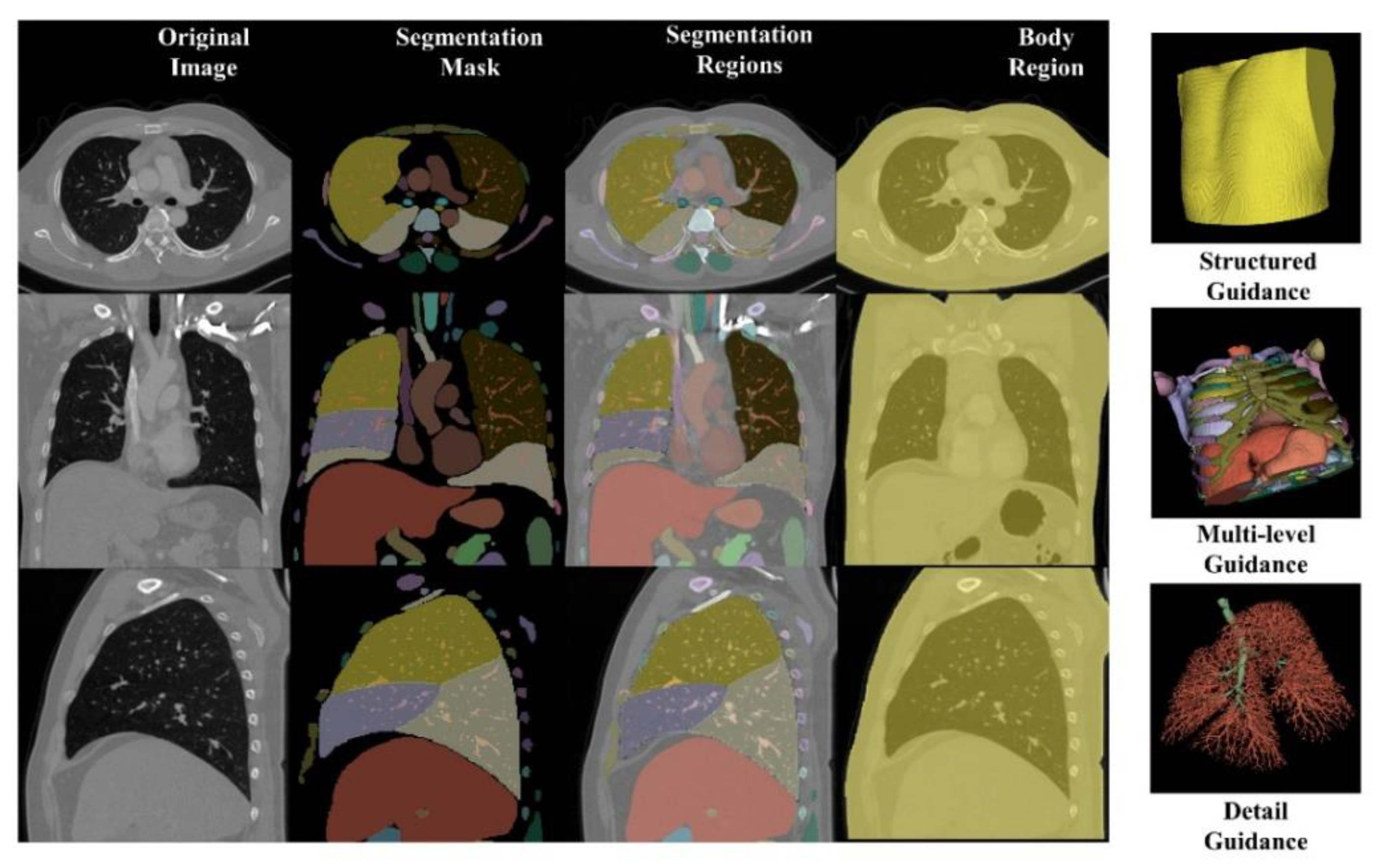

To address artifact reduction, the segmentation-guided diffusion model is trained exclusively on artifact-free (target domain) data, enabling cross-domain comparisons of identical anatomical regions in source (artifact-affected) and target domains to isolate artifact-induced variations and differentiate between variant and invariant features. The method integrates structured guidance from multi-class segmentation masks (including five lung lobes, trachea, body, muscle, mediastinal organs, and bones) converted to binary n-channel tensors via one-hot encoding, alongside anatomical detail guidance from small complex structures like airways and vessels. These guidance components are concatenated into the input tensor through additional channels to ensure consistent model conditioning. An ablation test evaluates the impact of structured vs. anatomical detail guidance on balancing artifact reduction and anatomical preservation, with the training procedure outlined in

Table 2 and segmentation classes visualized in

Figure 3.

Guided by concatenated segmentation and anatomical guidance at each denoising step, the model generates artifact-reduced images while preserving anatomical fidelity through structural and textural constraints enforced by segmentation masks. These masks provide contour and texture information to minimize training loss and optimize parameter updates. Leveraging domain-specific feature disparities and invariances, consistent style translation is enforced across domain-specific and adjacent scan slices to ensure coherent cross-sectional representation.

In the inference phase, the trained diffusion model transfers artifact-affected chest CT images to the artifact-free target domain. Chest CT imaging, characterized by intricate anatomical details, requires specialized segmentation approaches. To address this, we enhanced TotalSegmentator [

26] with MELA [

27], Parse2022 [

28], and ATM22 [

29] datasets to segment organs within and around the lung field. A body mask further refines region-of-interest (ROI) extraction. The dual-purpose segmentation model provides structural guidance during artifact reduction and evaluates anatomical preservation via Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) between segmented outputs of artifact-affected inputs and artifact-free predictions. This ensures consistency in anatomical representation across domains while quantifying structural fidelity. Maintaining anatomical integrity during diffusion-based reconstruction remains a core objective alongside artifact mitigation.

3. Results

This section provides evaluations of segmentation-guide diffusion model. We first introduce the datasets used in this study. Then we assess artifact reduction performance and anatomical preservation compared to notable state-of-the-art models. A further ablation study will be conducted to explain the effectiveness of different segmentation granularities provided as guidance

3.1. Datasets

The research data, specifically compiled for artifact reduction studies, was collected from four centers. It comprises a total of 96,641 unpaired chest CT slices from 763 CT scan series. These scans were conducted within a range of 110 to 150 kVp, with an average of 165 mAs. The slice thickness varies from 0.5 mm to 10 mm. Within this extensive dataset, 47,032 slices clearly exhibit significant artifacts, constituting the source domain. These samples provide valuable insights into the streaking artifact features encountered in CT imaging. Conversely, the remaining 49,609 artifact-free slices form the target domain. All samples and their domain divisions have been identified by two experienced radiologists. We randomly selected 20% of the samples from both the source and target domains to form a test set for evaluation in multiple aspects, including artifact reduction performance, anatomical preservation, and consistency of diffusion output in comparison to samples from the target domain.

During the training process of segmentation model, we utilized four datasets: TotalSegmentator, MELA, Parse2022, and ATM’22. For segmentation guidance in this research, we mainly follow the annotation pattern of anatomical structures from the TotalSegmentator CT dataset as the minimum segmentation granularity. To further accommodate images exhibiting diverse lesions, we applied the segmentation model of TotalSegmentator to annotate the following three datasets: MELA, Parse2022, and ATM’22. The MELA dataset is a significant collection of CT scans from 1136 patients, featuring 1152 annotated mediastinal lesions confirmed by biopsy. Parse2022 focuses on pulmonary arteries with 200 annotated volumes from contrast-enhanced CT scans. ATM’22 offers 500 comprehensively annotated CT scans of pulmonary airways, including COVID-19 images with ground-glass opacity and consolidation.

3.2. Evaluations

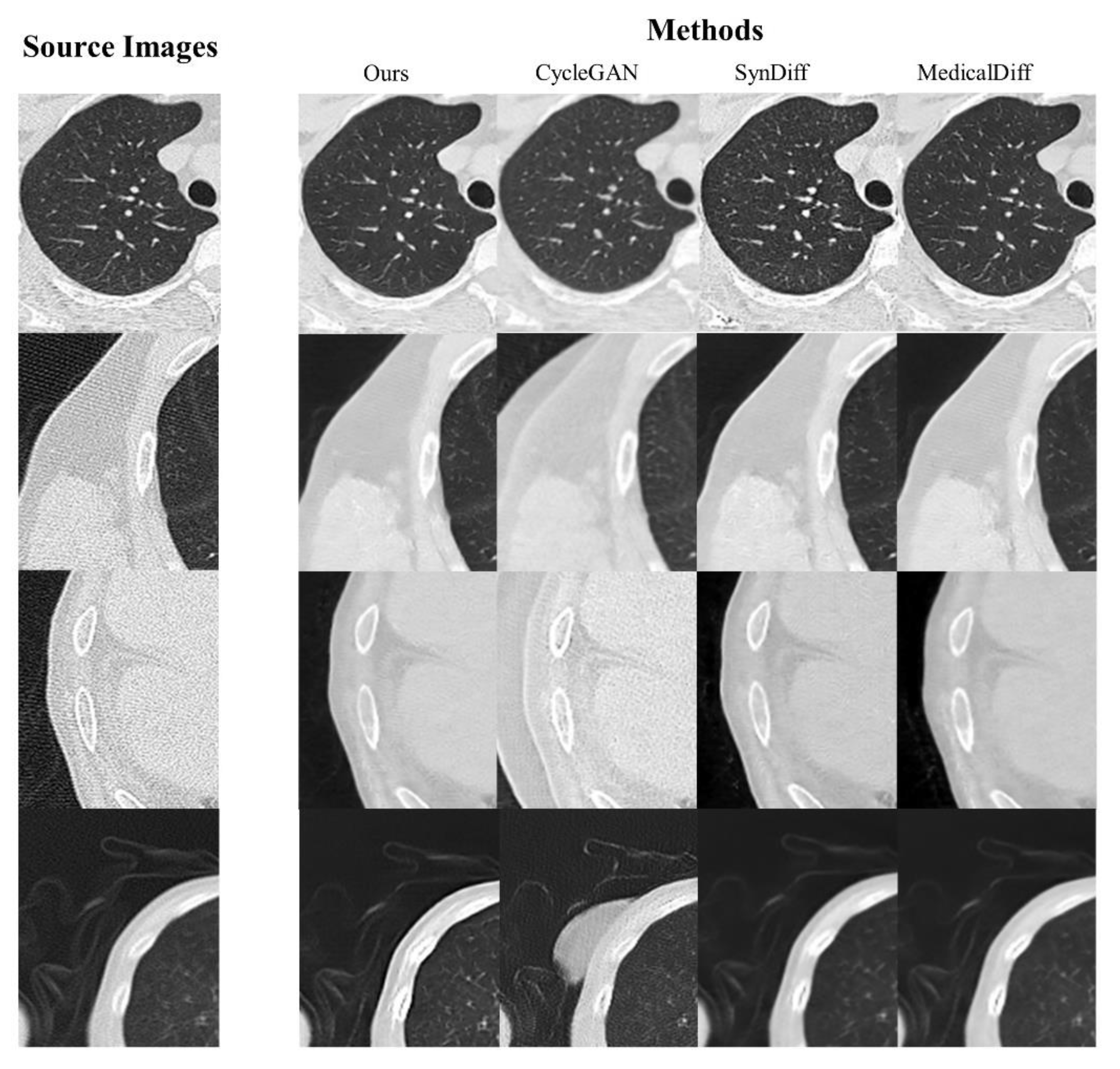

Quantitative evaluation of artifact reduction using PSNR and SSIM demonstrated significant improvements in the proposed method compared to CycleGAN [

10], SynDiff [

30], and CoreDiff [

24] (p<0.05), achieving the highest PSNR (36.95±0.67) and SSIM (0.86±0.01) across all ROIs, including lung fields and trachea, as shown in

Table 3. No statistically significant differences were observed in SNR (26.67±2.01 vs. 26.11±1.89) or CNR (3.76±0.77 vs. 3.78±0.56) between artifact-reduced images and actual artifact-free samples (p>0.05), confirming effective artifact mitigation without compromising image quality. DSC analysis revealed high anatomical preservation (0.96±0.13) between segmented outputs of artifact-laden inputs and artifact-free predictions, with consistent performance across four data centers (p>0.05). Cross-center analysis showed statistically significant SNR and CNR degradation in artifact-laden samples compared to artifact-free controls (p<0.05), particularly in large anatomical regions (e.g., lung fields, liver, spleen, mediastinum), with this effect consistent irrespective of artifact distribution (global/local). Ablation studies demonstrated that structured guidance (organ masks) and anatomical detail guidance (trachea /vessels) synergistically optimized artifact reduction and structural integrity.

Segmentation of artifact-reduced images generated by all methods (including CycleGAN, SynDiff, and the proposed method) using a consistent U-Net model—applied uniformly across all methods—revealed statistically significant improvements in DSC for the proposed method compared to baseline approaches (p<0.05), as shown in

Table 4.

Figure 4 visualizes the artifact reduction performance of four representative artifact-effected samples. All models were evaluated at the 3rd epoch post-convergence to ensure objective and comparable results. Compared to CycleGAN, the proposed method demonstrated superior performance in streaking artifact mitigation and anatomical reconstruction, with no spurious or non-anatomical artifacts introduced. Quantitative analysis confirmed the model’s ability to balance artifact reduction (PSNR/SSIM improvements) with structural fidelity, as validated by DSC scores.

3.2. Ablation Study

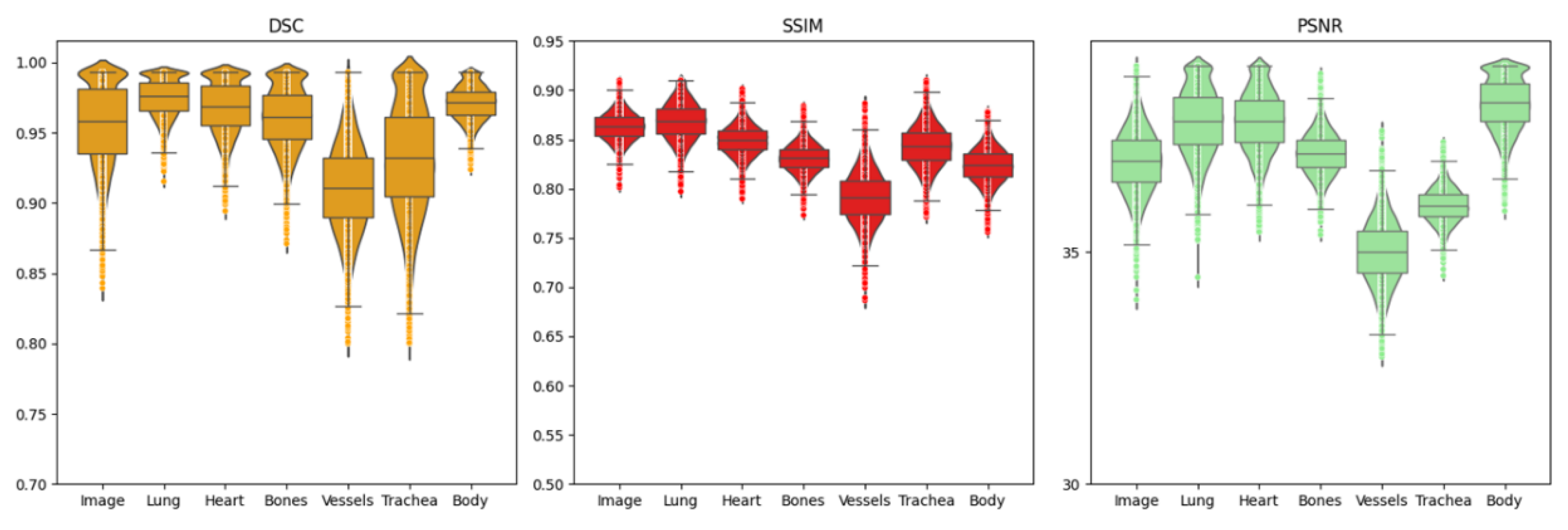

Ablation studies evaluating the effect of anatomical detail granularity revealed differential performance across ROIs, as shown in

Figure 5. DSC, SSIM, and PSNR metrics demonstrated that vessels and trachea consistently yielded lower scores compared to other regions, as shown in

Table 5. This observation indicates that fine-scale anatomical structures are more susceptible to perturbations during denoising, attributed to either residual artifacts in input images or reconstruction-related degradations.

To tackle these challenges, we analyzed the impact of the granularity in the guidance details, particularly pertaining to anatomical cues. Our findings suggested that increasing the level of detail in segmentation guidance, such as individual classification of vertebrae and ribs, or intricate segmentation of major mediastinal vessels, did not uniformly enhance artifact reduction performance. While these detailed cues aided in preserving anatomical information, they simultaneously posed potential limitations to the artifact reduction efficacy.

Table 5 presents the impact of three segmentation guidance levels—coarse-grained (Level-1), intermediate (Level-2), and fine-grained (Level-3)—on artifact reduction and anatomical preservation across regional and global metrics. Level-1 guidance (body vs. non-body regions) achieved the lowest lung DSC (0.972±0.133) and SSIM (0.856±0.03) due to insufficient structural constraints. Level-2 guidance, which segmented major organs (lungs, heart, mediastinum), improved lung DSC to 0.986±0.10 and SSIM to 0.869±0.03, demonstrating enhanced anatomical fidelity. The most detailed Level-3 guidance, incorporating sub-regional cues (lung lobes, tracheal branches, individual bones), yielded the highest trachea DSC (0.953±0.03) and overall DSC (0.970±0.08), indicating superior preservation of fine structures. Trachea PSNR/SSIM peaked at Level-2 (35.998±0.35/0.843±0.02), while overall metrics showed Level-2 outperformed others with PSNR 36.952±0.67 and SSIM 0.863±0.01.

Quantitative analysis revealed Level-2 guidance achieved the optimal balance between artifact reduction and anatomical preservation, outperforming Level-1 and Level-3 across global metrics (

Table 5). Level-2 demonstrated significantly higher lung PSNR (37.822±0.74) and SSIM (0.869±0.03) compared to Level-1 (36.109±0.43/0.856±0.03), while maintaining comparable trachea DSC (0.933±0.04 vs. Level-3’s 0.953±0.03). Although Level-3 achieved the highest trachea DSC (0.953±0.03) and overall DSC (0.970±0.08), it exhibited lower lung PSNR (36.327±0.70) and SSIM (0.858±0.07) compared to Level-2. These findings indicate that fine-grained guidance enhances regional structural fidelity but introduces computational overhead and may compromise global artifact reduction due to increased constraint complexity.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the substantial potential of the proposed segmentation-guided diffusion model for streaking artifact reduction in non-contrast chest CT scans. By leveraging the robustness of diffusion models against mode collapse and their iterative denoising capabilities, coupled with anatomically informed guidance from multi-scale segmentation masks, our method achieves a critical balance between artifact mitigation and structural preservation. The performance of Level-2 guidance (

Table 5) highlights that moderate segmentation granularity optimally constrains the diffusion process, avoiding overfitting to residual artifacts while preserving fine anatomical details. These findings advance current methods by addressing a long-standing challenge in CT image processing: minimizing artifacts without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

Diffusion models inherently mitigate mode collapse—a critical limitation in GAN-based approaches—by leveraging a progressive denoising framework that samples from the entire training distribution at each iteration. Unlike GANs, which often generate repetitive outputs due to biased mode selection during adversarial training, diffusion models employ gradient-based optimization in latent space to iteratively refine synthetic samples, ensuring faithful representation of anatomical diversity. This mechanism mitigates the risk of mode collapse while maintaining stable optimization dynamics, enabling accurate reconstruction of complex structures like tracheal branches and pulmonary vasculature. The integration of segmentation guidance further enhances this stability by imposing anatomically informed constraints, preventing over-smoothing of fine details during denoising.

The optimal performance of Level-2 guidance highlights that moderate segmentation detail balances structural preservation and artifact reduction. However, overly detailed segmentation guidance (Level-3) introduces three challenges: First, it may impose over-regularization by prioritizing subtle anatomical variations (e.g., lung lobule boundaries) that exceed the clinical relevance of denoising. This forces the diffusion model to preserve non-critical details during iterative refinement, potentially amplifying noise coinciding with these structures rather than suppressing artifacts. Second, ambiguous segmentation boundaries at fine scales—common in challenging regions like tracheal bifurcations—disrupt the denoising process by introducing conflicting spatial constraints across time steps. Lastly, the computational overhead of Level-3 guidance (e.g., segmenting individual ribs and bronchial branches) increases computing complexity, limiting clinical translatability. These findings underscore the importance of contextualizing segmentation granularity to the specific task requirements, as excessive anatomical detail may paradoxically degrade image quality in streaking artifact reduction workflows.

While this study demonstrates significant potential for segmentation-guided diffusion models in CT artifact reduction, several avenues for improvement remain. Future work should explore hybrid guidance strategies integrating clinical annotations, metabolic data, or patient-specific physiological parameters to enhance contextual relevance. Expanding the method to other modalities (e.g., MRI, PET, SPECT) presents opportunities to address unique challenges like motion artifacts in radiation-free imaging or low-count noise in functional scans. Notably, the optimal guidance resolution identified here (Level-2) may vary across applications, necessitating adaptive frameworks that dynamically adjust segmentation detail based on image complexity. Development of learnable guidance mechanisms—capable of automatically selecting task-appropriate granularity—represents a key next step toward generalizable clinical translation. These extensions would further solidify the role of diffusion models in medical image processing, balancing computational efficiency with diagnostic precision.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces a novel segmentation-guided diffusion model for mitigating streaking artifacts in non-contrast chest CT scans. By integrating multi-class anatomical guidance, the method effectively reduces artifacts while preserving structural integrity. Compared to existing methods, our method further improved image quality (PSNR, SSIM) and anatomical preservation (DSC). An ablation study suggested an optimal segmentation detail level balancing artifact reduction and anatomical fidelity. Overall, this approach enhances CT image quality, aiding clinical applications and treatment planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and Z.Z.; methodology, Z.Z., J.L., and X.Z.; software, J.L., Z.Z., and X.Z.; validation, Z.S., D.A. and L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, J.L. and K.C.; resources, X.Z., Z.S, and K.C.; data curation, D.A., L.Z. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; visualization, Z.Z., J.L and Z.S.; supervision, J.L. and Z.Z.; project administration, K.C., L.Z., and X.Z.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2018YFC1315604); and the Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant number 20210303003SF). .

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement:.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| DDPMs |

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models |

| DSC |

Dice Similarity Coefficient |

| GANs |

Generative Adversarial Networks |

| kVp |

Kilovolt Peak |

| mAs |

Milliampere-Second |

| MSE |

Mean Squared Error |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PSNR |

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| ROI |

Region of Interest |

| SPECT |

Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| SSIM |

Structural Similarity Index Measure |

References

- Barrett J.F, Keat N. Artifacts in CT: recognition and avoidance. Radiographics. 2004;24(6):1679-1691. [CrossRef]

- Boas, F. E., & Fleischmann, D. CT artifacts: causes and reduction techniques. Imaging Med. 2012; 4(2), 229-240. [CrossRef]

- Prakash P, Dutta S. Deep learning-based artifact detection for diagnostic CT images. Medical Imaging 2019: Physics of Medical Imaging. 2019; 10948, 109484C. [CrossRef]

- Shi Z, Wang N, Kong F, Cao H, Cao Q. A semi-supervised learning method of latent features based on convolutional neural networks for CT metal artifact reduction. Med Phys. 2022;49(6):3845-3859. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Yu H, Wang Z, Chen H, Liu Y, Lu J, et al. SemiMAR: Semi-Supervised Learning for CT Metal Artifact Reduction. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(11):5369-5380. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Gu J, Ye J. C. Unsupervised CT metal artifact learning using attention-guided β-CycleGAN. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2021;40(12):3932-3944. [CrossRef]

- Nakao M, Imanishi K, Ueda N, et al. Regularized three-dimensional generative adversarial nets for unsupervised metal artifact reduction in head and neck CT images. IEEE Access. 2020;8, 109453-109465. [CrossRef]

- Liao H, Lin W. A, Zhou S. K, Luo J. ADN: Artifact Disentanglement Network for Unsupervised Metal Artifact Reduction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39(3):634-643.

- Du M, Liang K, Zhang L, Gao H, Liu Y, Xing Y. Deep-Learning-Based Metal Artefact Reduction with Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Regularization for Practical CT Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42(8):2133-2145. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J Y, Park T, Isola P, Efros A. A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy; 2017; 2242-2251.

- Hoyez H, Schockaert C, Rambach J, Mirbach B, Stricker D. Unsupervised Image-to-Image Translation: A Review. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(21):8540. [CrossRef]

- Selim M, Zhang J, Fei B, Zhang GQ, Ge GY, Chen J. Cross-Vendor CT Image Data Harmonization Using CVH-CT. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2022;2021:1099-1108.

- Isola P, Zhu J Y, Zhou T, Efros, A. A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017; 1125-1134.

- Tang H, Liu H, Xu D, Torr PHS, Sebe N. AttentionGAN: Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation Using Attention-Guided Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34(4):1972-1987. [CrossRef]

- Ho J, Jain A, Abbeel P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2020; 33: 6840-6851.

- Nichol A Q, Dhariwal P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. International conference on machine learning. PMLR. 2021; 8162-8171.

- Müller-Franzes G, Niehues J. M, Khader F, Arasteh S. T, Haarburger C, Kuhl C, et al. A multimodal comparison of latent denoising diffusion probabilistic models and generative adversarial networks for medical image synthesis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12098. [CrossRef]

- Chung H, Sim B, Ye J C. Come-closer-diffuse-faster: Accelerating conditional diffusion models for inverse problems through stochastic contraction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022; 12413-12422.

- Jiang L, Mao Y, Wang X, Chen X, Li C. CoLa-Diff: Conditional latent diffusion model for multi-modal MRI synthesis. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. 2023;398-408. [CrossRef]

- Pinaya W.H.L, Tudosiu P. D, Dafflon J, Fernandez V, Nachev P, Cardoso M. J, et al. Brain imaging generation with latent diffusion models. Deep Generative Models: Second MICCAI Workshop, DGM4MICCAI 2022, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2022, Singapore. 2022; 13609: 117. [CrossRef]

- Saharia C, Chan W, Chang H, et al. Palette: Image-to-image diffusion models. ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 conference proceedings. 2022; 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Xie Y, Diao S, Tan S, Liang X. Unsupervised CT Metal Artifact Reduction by Plugging Diffusion Priors in Dual Domains. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2024;43(10):3533-3545. [CrossRef]

- Peng J, Qiu R. L. J, Wynne J. F, Chang C. W, Pan S, Wang T, et al. CBCT-Based synthetic CT image generation using conditional denoising diffusion probabilistic model. Med Phys. 2024;51(3):1847-1859. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Li Z, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Shan H. CoreDiff: Contextual Error-Modulated Generalized Diffusion Model for Low-Dose CT Denoising and Generalization. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2024;43(2):745-759. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Li C, Yan C, et al. Ultra-low Dose CT Image Denoising based on Conditional Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic model.2022 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC). 2022;198-205. [CrossRef]

- Wasserthal J, Breit H. C, Meyer M. T, Pradella M, Hinck D, Heye T, et al. TotalSegmentator: Robust Segmentation of 104 Anatomic Structures in CT Images. Radiol Artif Intell. 2023;5(5):e230024. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Ji X, Zhao M, Wen Y, She Y, Deng J,et al. Size-adaptive mediastinal multilesion detection in chest CT images via deep learning and a benchmark dataset. Med Phys. 2022;49(11):7222-7236. [CrossRef]

- Luo G, Wang K, Liu J, Li S, Liang X, Li X,et al. Efficient automatic segmentation for multi-level pulmonary arteries: The PARSE challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.03708. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Wu Y, Zhang H, Qin Y, Zheng H, Tang W, et al. Multi-site, Multi-domain Airway Tree Modeling. Med Image Anal. 2023;90:102957. [CrossRef]

- Ozbey M, Dalmaz O, Dar S.U.H, Bedel H.A, Ozturk S, Gungor A, et al. Unsupervised Medical Image Translation with Adversarial Diffusion Models. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42(12):3524-3539. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

It illustrates an overview of our artifact reduction pipeline, which presents a hierarchical method that builds upon the guided diffusion model. This method incorporates multiple anatomical structures and uses random Gaussian noise in conjunction with concatenated guidance to generate artifact-free images. During the segmentation stage, we applied a well-trained U-Net segmentation model to obtain multi-masks, and aligned these masks with the corresponding image regions, serving as the invariant guidance. This process focuses on balancing anatomy preservation and artifact reduction.

Figure 1.

It illustrates an overview of our artifact reduction pipeline, which presents a hierarchical method that builds upon the guided diffusion model. This method incorporates multiple anatomical structures and uses random Gaussian noise in conjunction with concatenated guidance to generate artifact-free images. During the segmentation stage, we applied a well-trained U-Net segmentation model to obtain multi-masks, and aligned these masks with the corresponding image regions, serving as the invariant guidance. This process focuses on balancing anatomy preservation and artifact reduction.

Figure 2.

An artifact chest CT sample was concatenated with the segmentation masks, and corresponding anatomical ROIs including lungs, heart, vessels, trachea, bones, and body, jointly serving as the source domain and providing guidance for z_t during the reversed diffusion process. After artifacts reduction, both the optimized CT slice and the original sample underwent segmentation using the same U-net model, achieving a high DSC (0.9812). Additionally, it is evident that the anatomical recognition accuracy is notably improved in the artifact-reduced image.

Figure 2.

An artifact chest CT sample was concatenated with the segmentation masks, and corresponding anatomical ROIs including lungs, heart, vessels, trachea, bones, and body, jointly serving as the source domain and providing guidance for z_t during the reversed diffusion process. After artifacts reduction, both the optimized CT slice and the original sample underwent segmentation using the same U-net model, achieving a high DSC (0.9812). Additionally, it is evident that the anatomical recognition accuracy is notably improved in the artifact-reduced image.

Figure 3.

In the concatenating stage, we integrate the original image, segmentation mask, segmentation regions, and body region as multi-level guidance. The segmentation mask, an n-value image (n = segmentation classes), maps each pixel from the same category to the same value, providing essential contour information. The segmentation regions, clipped based on the segmentation mask, offer comprehensive structured and anatomical details. The body region outlines the entire anatomical area.

Figure 3.

In the concatenating stage, we integrate the original image, segmentation mask, segmentation regions, and body region as multi-level guidance. The segmentation mask, an n-value image (n = segmentation classes), maps each pixel from the same category to the same value, providing essential contour information. The segmentation regions, clipped based on the segmentation mask, offer comprehensive structured and anatomical details. The body region outlines the entire anatomical area.

Figure 4.

Illustrative comparison of artifact reduction performances.

Figure 4.

Illustrative comparison of artifact reduction performances.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of DSC, SSIM, and PSNR metrics across multiple ROI levels for the proposed artifact reduction method.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of DSC, SSIM, and PSNR metrics across multiple ROI levels for the proposed artifact reduction method.

Table 1.

Artifact reduction using diffusion with segmentation guidance.

Table 1.

Artifact reduction using diffusion with segmentation guidance.

|

Algorithm 1 Artifact reduction using diffusion with segmentation guidance |

|

Input:input image ,concatenated guidance made by model Seg,noise level N |

|

Output:output domain image

|

|

for all t from N to 1 do

|

|

| end for |

|

return

|

Table 2.

The training paradigm of segmentation-guided diffusion model.

Table 2.

The training paradigm of segmentation-guided diffusion model.

|

Algorithm 2 The training paradigm of segmentation-guided diffusion model |

|

Input:Artifact-free samples

|

|

Repeat (for all training samples) |

Update trainable parameter :

Until converged; |

Table 3.

PSNR and SSIM evaluations on different ROIs.

Table 3.

PSNR and SSIM evaluations on different ROIs.

| |

Ours |

CycleGAN |

SynDiff |

CoreDiff |

| Lung PSNR |

37.822±0.74 |

35.196±0.63 |

36.177±0.84 |

37.356±0.49 |

| Lung SSIM |

0.869±0.03 |

0.855±0.03 |

0.859±0.06 |

0.855±0.02 |

| Trachea PSNR |

35.998±0.35 |

33.903±0.50 |

34.693±0.66 |

35.310±0.46 |

| Trachea SSIM |

0.843±0.02 |

0.810±0.04 |

0.833±0.07 |

0.828±0.03 |

| Overall PSNR |

36.952±0.67 |

34.776±0.81 |

35.722±0.93 |

36.498±0.55 |

| Overall SSIM |

0.863±0.01 |

0.835±0.09 |

0.856±0.07 |

0.851±0.01 |

Table 4.

DSC evaluations on different ROIs.

Table 4.

DSC evaluations on different ROIs.

| |

Ours |

CycleGAN |

SynDiff |

CoreDiff |

| Lung DSC |

0.986±0.095 |

0.939±0.161 |

0.988±0.203 |

0.979±0.091 |

| Trachea DSC |

0.933±0.041 |

0.890±0.780 |

0.929±0.125 |

0.931±0.027 |

| Bones DSC |

0.961±0.023 |

0.912±0.058 |

0.955±0.031 |

0.940±0.022 |

| Overall DSC |

0.959±0.134 |

0.932±0.206 |

0.953±0.318 |

0.951±0.126 |

Table 5.

Artifact reduction and anatomical preservation performances across detail levels of segmentation guidance.

Table 5.

Artifact reduction and anatomical preservation performances across detail levels of segmentation guidance.

| |

Detail Level-1 |

Detail Level-2 |

Detail Level-3 |

| Lung PSNR |

36.109±0.43 |

37.822±0.74 |

36.327±0.70 |

| Lung SSIM |

0.856±0.03 |

0.869±0.03 |

0.858±0.07 |

| Lung DSC |

0.972±0.133 |

0.986±0.10 |

0.989±0.05 |

| Trachea PSNR |

34.727±0.67 |

35.998±0.35 |

35.221±0.61 |

| Trachea SSIM |

0.833±0.05 |

0.843±0.02 |

0.839±0.04 |

| Trachea DSC |

0.931±0.08 |

0.933±0.04 |

0.953±0.03 |

| Overall PSNR |

35.796±0.83 |

36.952±0.67 |

36.808±0.59 |

| Overall SSIM |

0.858±0.07 |

0.863±0.01 |

0.856±0.09 |

| Overall DSC |

0.957±0.31 |

0.959±0.13 |

0.970±0.080 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).