1. Introduction

Remote sensing of lighting systems properties from space borne imagery represents a major challenge. First, the typical spatial resolution of publicly available satellite images does not allow the identification of individual light sources. In addition, these freely available night time satellite images are mostly panchromatic and it is therefore impossible to distinguish the spectral type of the sources [

1,

2]. One possibility to overcome both limits is to use images taken by the astronauts on board the International Space Station (ISS) [

1]. Images using 400 mm lens have a pixel footprint of about 8 meters, which is enough to perceive distinct lighting systems. Moreover, the images are captured with DSLR cameras so that the colour information contained in those images allows for the identification of the spectral type of the source if we exclude incandescent, fuel based lighting and other near blackbody emission technologies that have significant emission in the near infrared region [

3].

It has been shown by [

4,

5] that one can estimate on each pixel, both the photopic radiance and the spectral class (see

Table 1) using the color ratios. On such images, one can only detect the illuminated area on the ground after the emitted photons experienced a reflection process. In some case, direct upward light is also detected, however these pixels are usually saturated making it impossible to evaluate their true photopic radiances. If one assume a typical reflectance of the underlying ground surface, a Lambertian reflection model and that the most common Upward Light Output Ratio (ULOR) associated to each lighting spectrum is small or close to zero, it is possible to estimate its radiant flux by integrating the pixel photopic radiance over the illuminated area observed under each device. For most Light-Emitting Diodes (LED) streetlights, the assumption of ULOR≈ 0 is realistic. This is at least the case for the city of Montreal that was the target of the current study.

In this paper, we use the photopic radiance and spectral class images derived from ISS color pictures following the methodology of [

4,

5]. We suggest a method of determining the luminous flux (in lumen), the position and the spectral type of each lighting system out of the two images. We apply the Richardson-Lucy (RL) deconvolution algorithm [

6,

7] to the photopic radiance to transform the reflected light areas into a few set of pixels associated to the derived flux. We also use a watershed algorithm to isolate individual light sources from the ISS images with and without the RL deconvolution. This approach is of great interest to serve as input to modern light pollution numerical models such as Illumina v2 [

8,

9]. Usually, this light pollution model can incorporate point-like source inventories which is an outcome of the work presented herein.

2. Methods

This section outlines how the RL deconvolution algorithm was used on ISS images in order to reduce the spread of illuminated areas associated to street lamps or similar lighting systems. It also targets how the watershed algorithm is used on the ISS images to retrieve individual light sources.

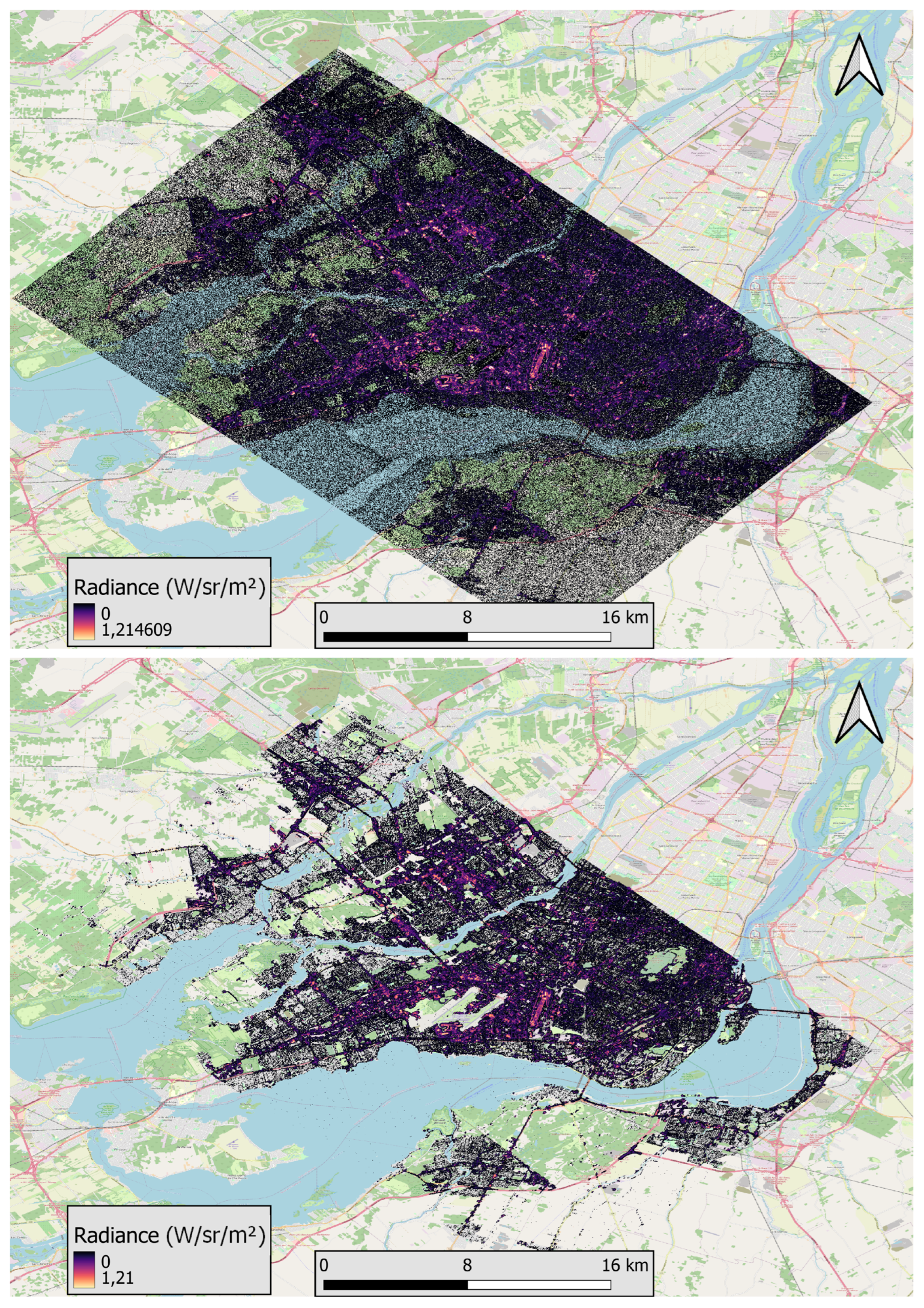

ISS images are acquired from SaveStars Consulting S.L., a company that processes raw ISS images and retrieves photopic radiance values and spectral types classification images (see

Figure 1) along with the viewing angle of the camera based on an examination of the ground-based patterns deformation. For this research project’s purposes, the images need to be postprocessed. The previous contains four steps: background removal, finding saturated pixels, isolated pixels removal and spectral class image corrections. The resultant images are hereafter called preprocessed images. The RL deconvolution algorithm is then applied using a point spread function (PSF) extracted from an isolated source contained in the image. Afterwards, the punctual source retrieval is completed using a watershed algorithm and centroid detection algorithm on the images with and without deconvolution in order to compare the results and determine the necessity of the RL deconvolution in the presented method.

2.1. From the Photopic Radiance to the Device Luminous Flux

According to the methodology developed by [

4] and [

5], one can determine the photopic band radiance corrected for the atmospheric extinction (

in

).

is defined from the spectral radiance

(also corrected for atmospheric extinction) as follow.

is the photopic sensitivity.

Prior to converting

to the lighting device luminous flux, we must remove the background photopic radiance to obtain a background free photopic radiance

. The background photopic radiance

is the result of star and moon light reflected by the ground along with of the light scattered by the atmosphere.

If we assume a typical averaged ground reflectance over the photopic band

and that the ground reflection follows a Lambertian law, it is possible to estimate the photopic radiant flux (

) intercepted by the ground underneath a lighting device as a function of the background free photopic radiance.

where

l is the pixel footprint on the ground. It can be determined with the optomechanical properties of the camera.

h is the altitude of the ISS image,

x is the pixel size and

f is the focal length of the camera. The cosinus correction in equation

3 aims to correct the projection angle since that ISS images are not always taken at nadir. The information about the camera properties, the altitude of the ISS are given by NASA while the nadir angle

is estimated by analysing the image deformation over known ground-based patterns.

is expressed in units of Watt but can be converted to Luminous flux in Lumen

. [

10,

11]

2.2. Natural Background Removal and Error Correction on ISS Images

As stated, the background photopic radiance found in ISS images are due to two main factors: natural light reflected on the ground, such as Moon light and stars; and light scattered by the atmosphere and coming from distributed sources at different locations than the actual source. As the main objective of this work is to characterize the lighting devices, the background needs to be removed.

Apart from the background removal, in this section the possible errors or artifacts that the image may have and their linked correction are explained. The process is divided in four steps: background removal, finding saturated pixels, isolated pixels removal on the photopic radiance and lighting technology images.

2.2.1. Background Removal

Background light varies depending on the ISS image. It depends on the natural sources (mainly the moon and the Milky Way), the composition of the atmosphere and the reflectance of the ground.

In this study it was assumed that the background light is constant for all the region covered by an image. Although it is mostly correct for accounting for the natural sources and the composition of the atmosphere, different surfaces may present differences in terms of background photopic radiance. The lack of high resolution information about surface reflectance and the fact that direct and scattered light is entangled in the photopic radiance received by the camera prevented us from moving forward in this direction. After many trials to obtain an automated background removal method that worked for all the images, we realized it was very difficult due to the differences between them.

The proposed methodology consists of identifying a dark site where there is almost no artificial lighting to isolate the value of natural light. The average pixel value of this site is substracted from every pixel of the image. Afterwards, all the pixels with negative values are removed. By removing the negative values we acknowledge that a small part of the background remains in the image but we found that the lost values are typically a million times smaller than the mean value of the dark place that was subtracted.

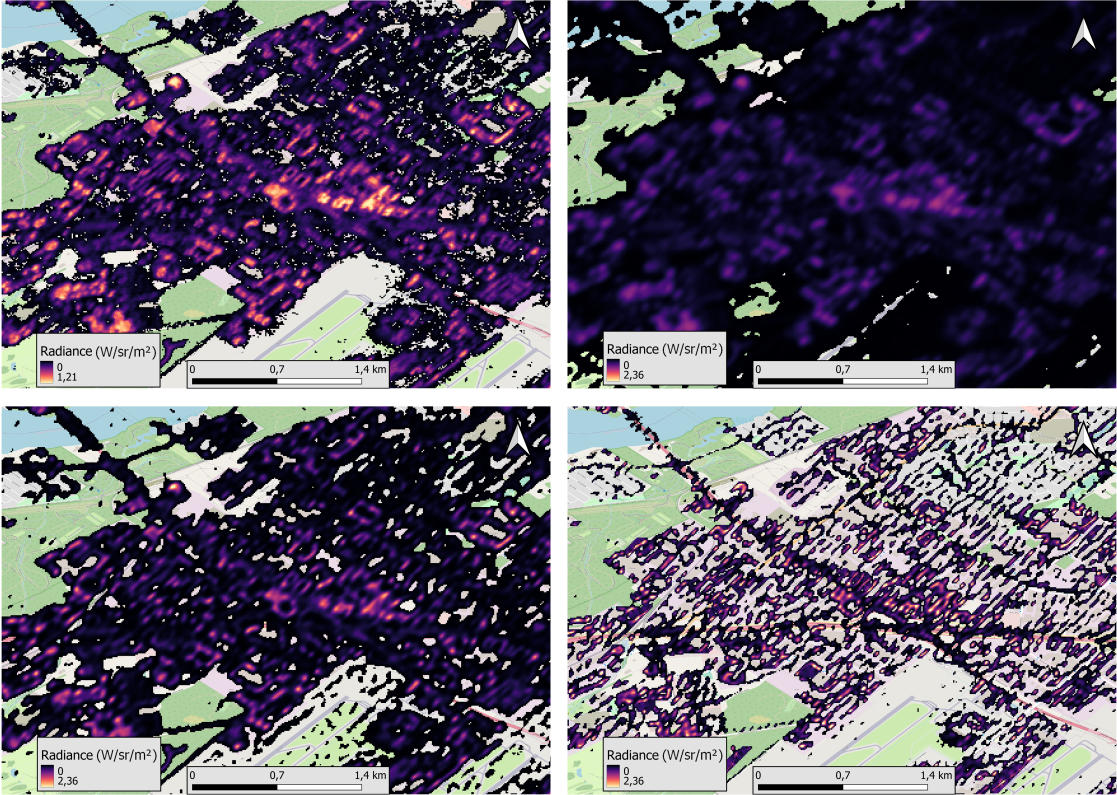

Figure 2 shows the result of applying the background removal method to an ISS image of Montréal. In the original image there are many non zero pixels in the river, parks and other dark places. After the treatment those areas are mostly devoid of these pixels and the street network is better recognizable.

2.2.2. Finding Saturated Pixels

Saturated pixels are those too bright for the camera to process. As a result, they appear as non emitting pixels. To correct, at least partially that problem, those pixels are located and provided with a photopic radiance value for them.

There are two kinds of saturated pixels found in the images. Firstly, pixels with infinite value. These pixels are the fewest and are easy to find. Their photopic radiance is changed to the maximum photopic radiance of the image since they are at least that bright. It is acknowledged that it results to an underestimation of the radiance. Secondly, pixels with no value that are surrounded by bright pixels. It includes all the pixels with a value of 0 that are surrounded by at least 3 pixels within a 3x3 window whose mean is higher than that of the image. Their photopic radiance is changed to the mean of their surrounding pixels. The result is shown on

Figure 3.

2.2.3. Isolated Pixels Removal

Even after the background removal there still remains a non-negligible amount of isolated non null pixels scattered in areas where no light emission is expected: over water (rivers, sea, lakes, etc) and in the countryside far from roads and houses. These bright pixels can be produced by temporary sources such as boats, cars or construction sites, or they could be artifacts created by the camera or the processing for obtaining radiance information from the raw image.

It is important to remove these pixels as any pixel within the image with radiance associated to it will be considered a permanent source in further analysis. The time needed to run light pollution models is normally directly proportional to the number of sources present. Therefore, removing these isolated pixels will not only produce more accurate results but will fasten the computations. Non-real sources pixels are those surrounded by only three or less pixels in a 5x5 window. The result of this process is shown on

Figure 4.

2.2.4. Photopic Radiance and Lighting Spectral Class Images

After treating the photopic radiance image the coherence between that image and the spectral one is lost.

In order to recover it, the spectral class image has to be processed. Firstly, all the pixels that now have no radiance are removed from the technology image. Secondly, the pixels that were void but after the treatment they do have radiance are still void in the technology image. The most repeated value (mode) of the pixels around them (3x3 window) is their assumed new technology class.

The idea behind it is that technology lamps are normally grouped together and they usually do not change abruptly in a city.

2.3. Using Richardson-Lucy Algorithm to Retrieve Quasi Punctual Sources

The main principle of RL deconvolution algorithm is the iterative process. This type of algorithm was put forward for the Hubble space telescope. A blurred Hubble space telescope image was restored with the point spread function (PSF) of the image, and an initial blurred guess of what the image should be. If the guess is incorrect it can be adjusted in the parameters, but if it is correct, the image can be restored using the PSF. This method was created to improve the convergence speed and the sensitivity to noise ([

12]).

The RL deconvolution algorithm is implemented in this method with the aim of retrieving quasi point-like sources from illuminated surface below each streetlights or similar lighting devices. Using the iterative process, the ground lit areas can be reduced significantly. Because of its reduction of the number of illuminated pixels, the RL deconvolution can reduce the computation time when performing numeric modelling of light pollution. It conserves the photopic radiance of ground lit areas while reducing their size.

The iterative process of this method is what makes it efficient. However, if the number of iterations is too high it can eliminate many sources during the RL deconvolution. To avoid this problem, the evaluation of the total number of individual sources for modelling was compared to an inventory of street lamps in Montréal. The ideal number of iterations was chosen with the satisfaction of four criteria. Firstly, the photopic radiance needed to be conserved between the original ground lit area and the deconvolved one. Secondly, the ground lit areas needed to be reduced in size with the process without eliminating too many individual sources. If the number of iteration is too high the algorithm could eliminate too many low intensity sources. Thirdly, the number of resulting ground lit pixels had to be in accordance with the city inventory of streetlights. Finally, the time elapsed for the RL deconvolution calculations needed to be the shortest possible while prioritizing the three other criteria.

The RL deconvolution process contains many steps. The preprocessed photopic radiance image is an input of the algorithm. A PSF also needs to be extracted from the same image. It needs to be an isolated source from a region of the image. This single source’s PSF is applied to the whole image. For the purpose of this research we assume that the extracted PSF is constant throughout the image and we acknowloedge that it can alter the position and number of resulting sources. The PSF and the photopic radiance image are provided to the algorithm along with the number of desired iterations.

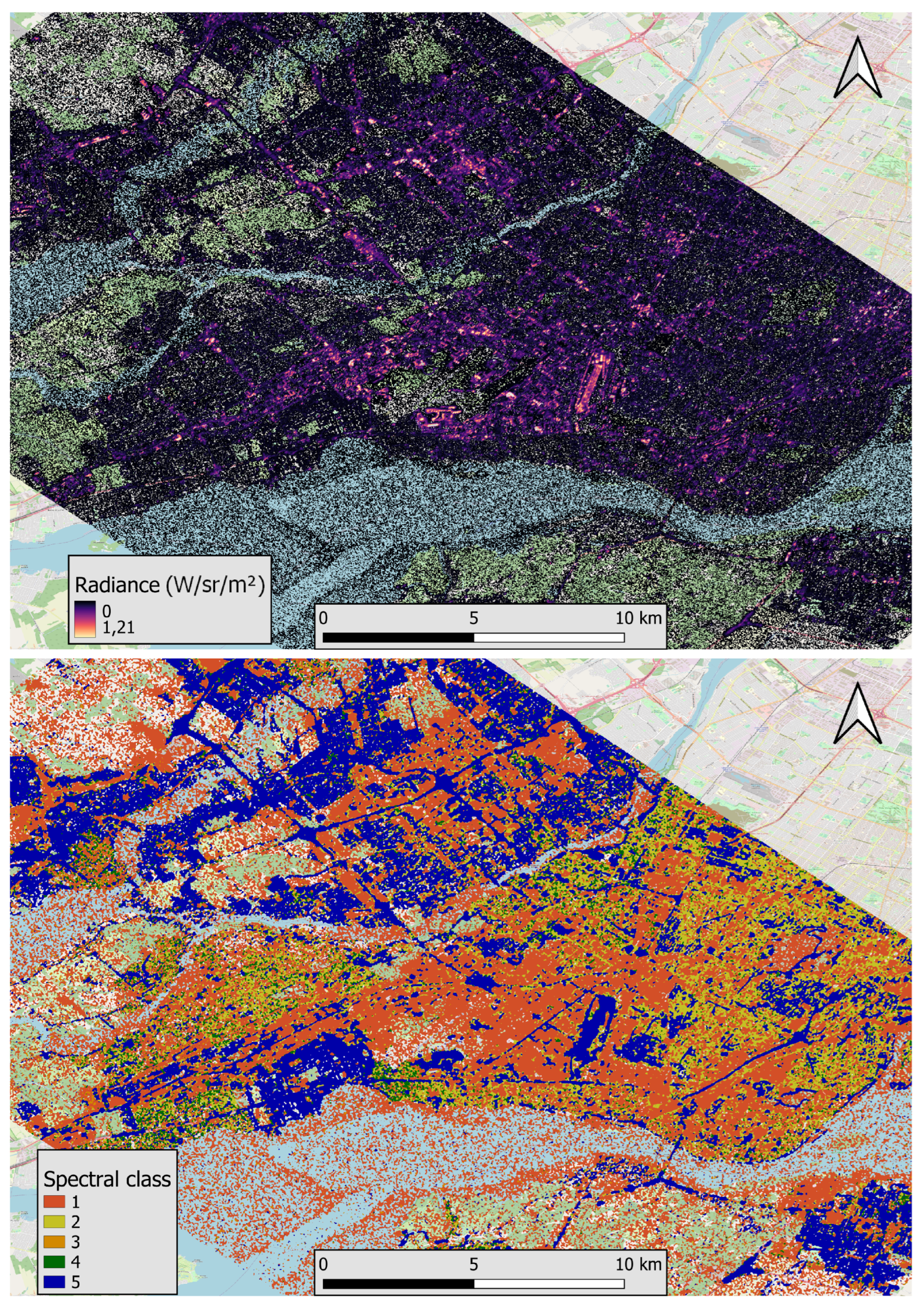

Figure 5 shows the various number of iterations applied to the image of Montréal.

2.4. Estimating Luminous Fluxes per Source

The luminous flux of the extracted sources can be found using equation

3 and

5. With precise information on the luminous flux of light source for the study area it would be possible to validate the accuracy of the estimation. This validation was not done in this project due to a lack of information in the light inventory of Montréal.

2.5. Retrieving Punctual Sources from the Image

The punctual sources retrieval algorithm is used to find a punctual source for every illuminated area in the image. The different illuminated areas on the image dilate with a maximum filter and different local peaks are found throughout the image. These peaks are used to create a mask and arrange it with the peaks length. Afterwards, a watershed segmentation in which the peaks are used as marker to separate the different illuminated areas in the image is implemented. Finally, the pixel flux weighted centroid is extracted.

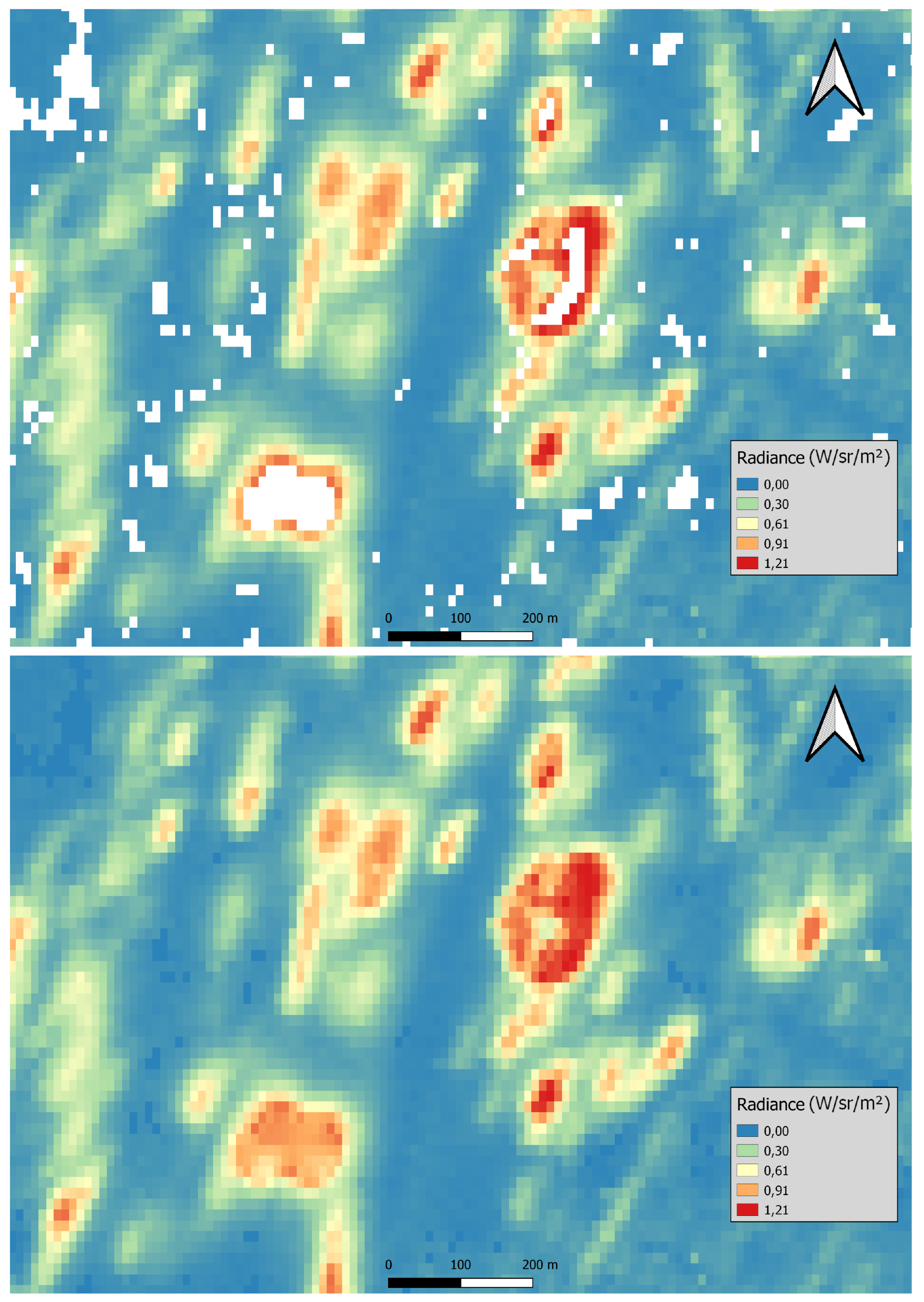

Figure 6 shows the ponctual sources indentification applied to a residential neighborhood of Montréal. On that figure, we used the image without applying the RL deconvolution algorithm.

3. Results

The RL deconvolution process is based on the reduction of the ground lit areas on the ISS images. The results showed on

Figure 5 are at three different levels of iteration. In addition,

Figure 7 shows how the photopic radiance is conserved within the PSF after different number of iterations along with how the illuminated areas reduce with the number of iterations. The first number of iterations tested was 1. This result does not take into account the iterative process of the RL algorithm. The comparison with the two other numbers of iterations is efficient to visualize that the image is blurred after 1 iteration and the size of the ground lit areas are bigger than on the preprocessed image. That is confirmed by the higher full width half maximum (FWHM) as showed of

Figure 7. Without the iterative process, the RL deconvolution algorithm does not reduce the ground lit areas. The second number of iterations that was tested is 5. As shown on

Figure 5, there is a significant reduction of the ground lit pixel areas. The FWHM is also reduced from 80 meters to 50 meters as shown on

Figure 7. In addition, the computing time remains under one minute which does not impact the ability to perform the process many times. For 30 iterations, the conservation of the photopic radiance of the PSF is almost perfect. On the bottom plot of

Figure 7, we can see that the Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM) of the illuminated area was reduced by a factor of 16 after 30 iterations. The computing time is still under one minute and the photopic radiance is fully conserved at the PSF level. That result implies an acceleration of light pollution modelling by the same factor (16). Overall for the image obtained after thirty iterations of the RL deconvolution, the total photopic radiance of the deconvolved images is 3% higher than in the preprocessed image. This is caused by the use of one PSF for the entire image even though it is different for every light source.

It is important that the conservation of the photopic radiance that occurs within a PSF during the RL deconvolution is as close as possible to 100 percent, because the loss of photopic radiance could falsify the data for further light pollution modelling.

The punctual sources retrieval algorithm detects a centroid within watershed polygons. It was both applied with and without RL deconvolution in order to evaluate the necessity to use the RL deconvolution algorithm when trying to retrieve punctual sources. The results are that the algorithm found 238 365 individual light sources in the ISS image without the RL deconvolution algorithm and 151 100 sources with the RL deconvolution algorithm. This difference is attributed to the reduction the density of pixels in the RL deconvolution process, for thirty iterations. The base assumption that was made is that a deconvolved image would have more separated PSF and that therefore the punctual sources retrieval algorithm would find more individual sources. However, the convergence of light sources with the RL deconvolution algorithm eliminates many potential individual sources of lower intensity. This could represents a problem for modelling light pollution close or within the city.

The efficiency of the punctual sources retrieval algorithm was validated by comparing with an inventory of streetlights provided by the city of Montréal. Following the source extraction, the number of extracted sources within a designated polygon shown in

Figure 6 is compared to the sum of streetlights from the inventory within the same polygon. This comparison was completed in a residential area where there are no high buildings and commercial lighting. Furthermore, since the houses in that residential area are not as tall as the streetlights, the risk of masked sources is reduced. The image being acquired on February 26th, 2021 at 09:15:06 GMT (04:15:06 local Montréal time), the tree leaves cannot either mask streetlights. The choice of a residential area also limit considerably the industrial lighting contribution to the artificial lighting on that part of the ISS image. The punctual sources retrieval algorithm successfully extracted 221 sources without the RL deconvolution algorithm, 119 sources with the RL deconvolution algorithm set at 30 iterations and in the city of Montréal inventory, there are 195 streetlights in the same zone. The algorithm therefore extracted respectively 61% and 113% of the sources with and without RL deconvolution. The extra 13% detected without RL deconvolution is probably associated to private lighting not included in the city inventory, but this hypothesis cannot be confirmed. Depending on the period of the year that the ISS image is taken, many sources could be blocked by trees. To make sure that it does not happen, two or more images with different shooting angle could be used. In some parts of the city, buildings could also be blocking sources.

Another form of evalutation that was used is to delimit a zone in Montréal where the inventory of city streetlights only has LED type of lighting and verify whether the extracted sources have the same type of lighting as the inventory. For a delimited area in Montréal, shown in

Figure 6, the algorithm only successfully retrieved 32 percent of the lighting types. Therefore, the technology identification is not accurate. A possible explanation for this result is that the spectral classes are not correctly identified because of color transformation coming from the spectral dependency of the ground reflectance. The spectral classes were identified by [

4] with a spectral database sampled in laboratory combined with synthetic photometry to mimic the detection of the camera used by the astronauts. Determining the classes in laboratory might pose problem when identifying these same classes on a space-borne image. In fact, the reflection of artificial light on asphalt favors the reflectance of red color while the snow cover favor the blue color. But snow reflectance is about 20 times higher than asphalt so that the dominant effect in February for Montréal is the snow reflectance. The combined spectral reflectance of 90% of snow and 10% of asphalt is shown in

Figure 8. That blue favoring ground reflectance alters the color ratios used for spectral classes recognition. The atmospheric extinction also modifies the color and is associated to a reddening process. If the atmospheric correction is not perfectly done on the images, the color ratios can also be affected. The expected effect of the spectral transformation of the ground reflection is that ground based warm lights will be identified as cooler ones. This is actually what the comparison between the spectral classes recognition and the city of Montréal inventory shows. Table spectraltable shows that too many light fixtures were detected in class 1 (110 lamps) which correspond to 4000K LEDs in the Montréal inventory while not enough in class 2 (64) which correspond to 3000K LEDs. Assuming the 110 lamps in class 1 were misidentified class 2, then the total number of class 2 would be 174 which compares favorably to the 186 class 2 of the Montréal’s inventory. In summary, to be able to detect correctly the spectral classes, we estimate that one should apply a spectral transformation to the class definition provided by [

4] according to the expected spectral reflectance of the underlying ground surface.

All things considered, the punctual sources retrieval algorithm should not be paired with the RL deconvolution algorithm to ensure full retrieval of individual light sources. If a user does not want to use the punctual sources retrieval algorithm and use raster data instead as an input in a light pollution model, the RL deconvolution process is useful to reduce the total modelling time while almost conserving the total luminous flux on the image but dim sources are lost and the total photopic radiance of the image is increased by 3%.

Table 2.

Spectral class recognition compared to the city of Montréal inventory in the polygon shown in

Figure 6.

Table 2.

Spectral class recognition compared to the city of Montréal inventory in the polygon shown in

Figure 6.

| Spectral Class |

Number - regonition |

Number - city inventory |

| 0 |

5 |

- |

| 1 |

110 |

0 |

| 2 |

64 |

186 |

| 3 |

6 |

1 |

| 4 |

15 |

8 |

| 5 |

21 |

0 |

| 6 |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

221 |

195 |

4. Conclusion

This paper aimed to introduce a punctual source extraction method applied to images taken by astronauts on board of the ISS and the light pollution research domain. The ISS images needed to be corrected for the noise and background. Saturated and isolated pixels contained in the images were eliminated. The RL deconvolution algorithm was applied to the resulting image. The punctual sources retrieval algorithm was applied to the deconvolved images and the preprocessed images. The result of the comparison between the punctual sources extraction from the deconvolved and preprocessed images is that the RL deconvolution algorithm is relevant for raster data analysis but the agressivity of the algorithm eliminates many dim individual light sources from being extracted by the punctual sources retrieval algorithm. The punctual sources retrieval algorithm retrieved more sources than there were in the inventory which is normal due to private lighting not being included in the inventory. The technology association for the extracted sources is not conclusive. This may be because of the spectral transformation from the ground reflectance that introduces confusion in the spectral classes identification. However, even if not perfect, we estimate that using that method as an input file preparation for light pollution modelling will considerably reduced computing time. That is especially true when taking into account the reduction of an image into a limited set of individual sources.

Acknowledgments

We applied the sequence-determines-credit approach for the sequence of authors [

14] so that authors appear in decreasing order of their level of contribution to the research. This work was supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québéc Nature et les Technologie (FQRNT) and Santé (FRQS) and by the FAST program of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Computation time was partly provided by Compute Canada and Calcul Québec.

References

- Kyba, C.; Garz, S.; Kuechly, H.; De Miguel, A.S.; Zamorano, J.; Fischer, J.; Hölker, F. High-resolution imagery of earth at night: New sources, opportunities and challenges. Remote sensing 2015, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Linares Arroyo, H.; Abascal, A.; Degen, T.; Aubé, M.; Espey, B.R.; Gyuk, G.; Hölker, F.; Jechow, A.; Kuffer, M.; Sánchez de Miguel, A.; et al. Monitoring, trends and impacts of light pollution. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2024, 5, 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Elvidge, C.D.; Keith, D.M.; Tuttle, B.T.; Baugh, K.E. Spectral identification of lighting type and character. Sensors 2010, 10, 3961–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez de Miguel, A.; Kyba, C.C.; Aubé, M.; Zamorano, J.; Cardiel, N.; Tapia, C.; Bennie, J.; Gaston, K.J. Colour remote sensing of the impact of artificial light at night (I): The potential of the International Space Station and other DSLR-based platforms. Remote sensing of environment 2019, 224, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Miguel, A.; Zamorano, J.; Aubé, M.; Bennie, J.; Gallego, J.; Ocaña, F.; Pettit, D.R.; Stefanov, W.L.; Gaston, K.J. Colour remote sensing of the impact of artificial light at night (II): Calibration of DSLR-based images from the International Space Station. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 264, 112611. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, W.H. Bayesian-based iterative method of image restoration. JoSA 1972, 62, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lucy, L.B. An iterative technique for the rectification of observed distributions. Astronomical Journal 1974, 79, 745. [Google Scholar]

- Aubé, M.; Simoneau, A. New features to the night sky radiance model illumina: Hyperspectral support, improved obstacles and cloud reflection. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2018, 211, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubé, M.; Simoneau, A.; Muñoz-Tuñón, C.; Díaz-Castro, J.; Serra-Ricart, M. Restoring the night sky darkness at Observatorio del Teide: First application of the model Illumina version 2. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2020, 497, 2501–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomo, P. CORRIGENDUM: News from the BIPM. Metrologia 1980, 16, 104. [Google Scholar]

- CGPM. Comptes rendues des scéances de la 16e Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures CGPM (Minutes of the meetings of the 16th General Conference on Measures and Weights CGPM), 1979.

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhou, L. Restoration of motion blurred image with Lucy-Richardson algorithm. In Proceedings of the AOPC 2015: Image Processing and Analysis; Shen, C., Yang, W., Liu, H., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2015; Volume 9675, p. 967519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerdink, S.K.; Hook, S.J.; Roberts, D.A.; Abbott, E.A. The ECOSTRESS spectral library version 1.0. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 230, 111196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Hochberg, M.E.; Rand, T.A.; Resh, V.H.; Krauss, J. Author sequence and credit for contributions in multiauthored publications. PLoS biology 2007, 5, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).