Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by abnormalities in social and communication skills and a tendency towards limited and repetitive behavior patterns [

1]. In addition to the main axis of symptoms, sensory integration disorders are also mentioned, which include excessive or insufficient reactions to auditory, visual, tactile, proprioceptive or other stimuli [

2]. This phenomenon can be attributed to alterations in the brain structures implicated in the processes of perception, analysis and integration of sensory stimuli, such as the cerebellum, sensory cortex and thalamus [

3]. Evidence has been also found of abnormal neurotransmitter secretion in individuals diagnosed with ASD. This abnormality includes disorders in the release and action of glutamate (Glu) or gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [

4]. Not only altered brain anatomy but also abnormal neuroplasticity may play a role in impaired sensory integration. Neuroplasticity is a complex process that enables the central nervous system (CNS) to adapt structurally and functionally to experiences, maturation and recovery from injury [

5]. This includes genetic, molecular and cellular mechanisms that modulate synaptic connections and neuronal circuits, resulting in the strengthening or loss of behavior and function [

6]. However, neuroplasticity can also result in maladaptive outcomes depending on the stage of neurodevelopment, the extent of neuropathogenic factors, and the integrity of homeostatic regulatory mechanisms [

7].

Materials and Methods

A search was performed in the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, using combinations of the following search terms: autism, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), sensory disturbances, sensory integration, therapy, neuroplasticity. The literature search and the manuscript writing were done between November 2024 and March 2025. Since this work is a narrative review, no strict inclusion criteria were established for the selection of articles. During the screening process, studies addressing neuroplasticity, sensory integration and therapies in ASD were included. Based on titles and abstracts, conference abstracts were excluded. Studies not written in English were also omitted. Additionally, supporting literature on potential therapeutic approaches was included. The suitability for inclusion was evaluated on the basis of the full publication. All reference lists of found articles were screened for usefulness. It is essential to note that review is not systematic, and despite attempts to cover all studies, one should keep in mind significant limitations. DeepL was utilized during the manuscript preparation for language refinement, grammatical corrections, and translation support.

Neuroplasticity in ASD

Neuroplasticity is defined as the brain’s capacity to establish new neural connections or eliminate superfluous ones in response to environmental stimuli [

5]. The processes responsible for this phenomenon are neurogenesis and synaptogenesis. Neurogenesis is defined as the formation of new synaptic connections and neural networks, while synaptogenesis is the elimination of unnecessary synapses, otherwise known as synaptic pruning [

8,

9]. Neuroplasticity plays a key role in the effective processing of sensory stimuli and in generating adequate responses to these stimuli. For the sensory integration process to work properly, the brain must identify sensory patterns, anticipate their meaning, and create appropriate adaptive responses. It is evident that neuroplasticity is a pivotal factor in the development of these abilities during childhood, with the potential for modification into adulthood [

10]. The presence of neuroplasticity abnormalities may offer a potential explanation for the etiopathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. This can involve opening and closing critical periods at suboptimal times, consequently leading to improper organization of individual neural circuits [

11]. Another theory postulates that homeostatic plasticity in ASD is maladaptive and results in the destabilization of network activity, such as an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory responses [

12,

13]. Although excitatory-inhibitory neurotransmission disorders currently play the most important role in the impaired neuroplasticity of ASD, further research is still needed in this area [

14].

The role of glutamate (Glu) in neuroplasticity is a subject of considerable interest. Research has indicated that children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder exhibit elevated plasma levels of this amino acid. [

15,

16,

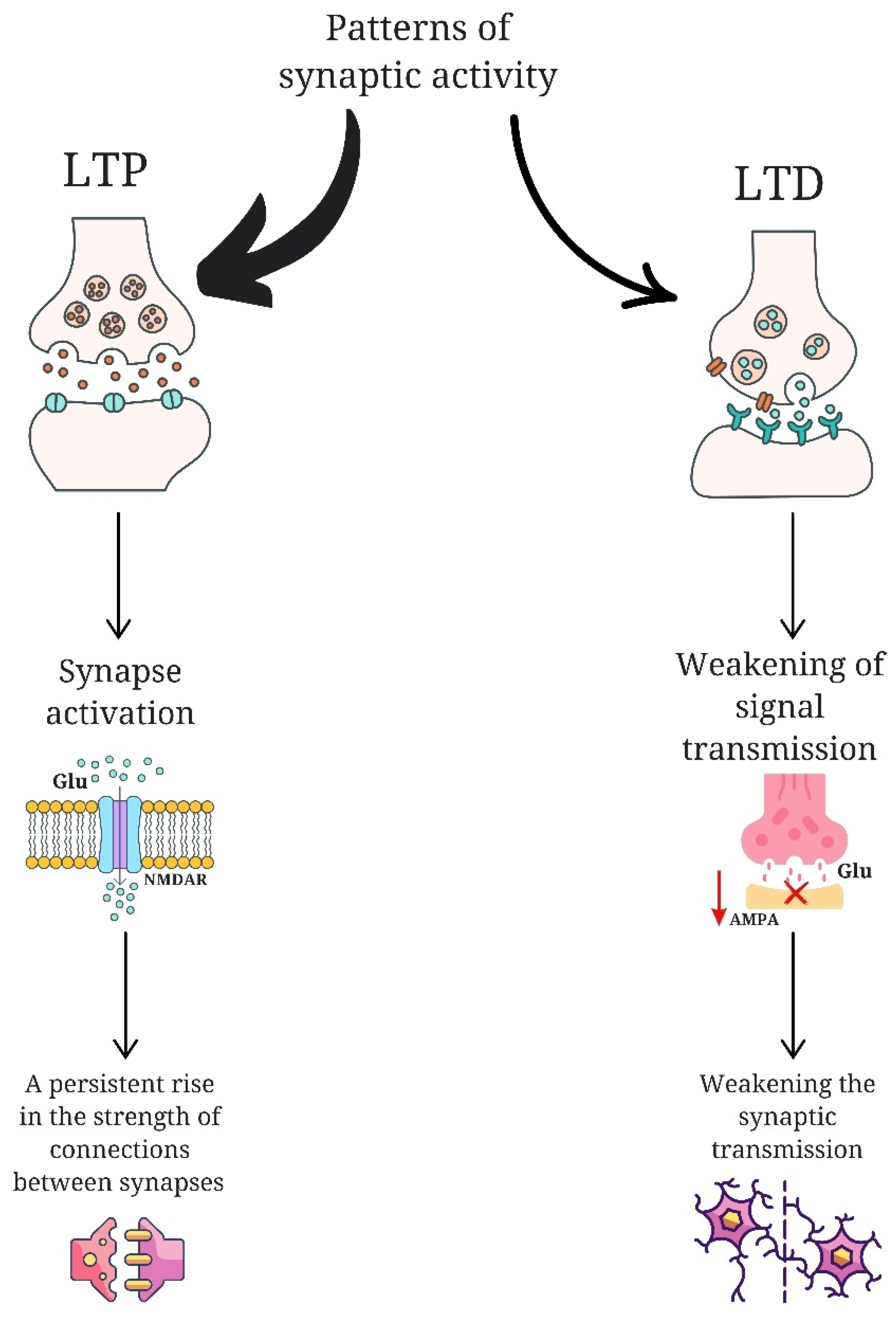

17] The elements that are subject to disruption in neuroplasticity include: abnormalities in long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), disruptions in protein synthesis, changes in the morphology and synthesis of the dendritic spine, and abnormalities in synaptic pruning [

18]. LTP is a neuroplasticity process that results in a permanent increase in the strength of connections between neurons. It occurs as a result of intense or multiple activation of synapses, which triggers a series of molecular and biochemical mechanisms leading to more efficient signal transmission. A key element of LTP is the activation of glutamate receptors such as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR) [

19]. LTD, on the other hand, is the opposite of LTP and is responsible for the long-term reduction of synaptic connection strength. This form of neuroplasticity enables the reorganization of neuronal networks and their adaptation to changing conditions. LTD occurs in response to specific patterns of synaptic activity that are usually less intense than those needed to induce LTP [

20]. During this process, the number of functioning glutamate receptors, mainly α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), in the postsynaptic membrane is reduced, which leads to a weakening of signal transmission. This mechanism enables the brain to modify stored memory traces, eliminate superfluous information, and extinguish reactions to stimuli that have become meaningless [

21].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). LTP acts through glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR), leading to the activation of synapses and strengthening of connections between neurons. LTD is expressed as less intense patterns of synaptic activity, causing a reduction of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPA) in the postsynaptic membrane, which results in the weakening of synaptic transmission and a reduction of connections between neurons.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). LTP acts through glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR), leading to the activation of synapses and strengthening of connections between neurons. LTD is expressed as less intense patterns of synaptic activity, causing a reduction of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPA) in the postsynaptic membrane, which results in the weakening of synaptic transmission and a reduction of connections between neurons.

It is postulated that an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory responses is a contributing factor in the etiology of ASD [

22,

23]. Disruption of LTP and long-term LTD has been observed in several disorders with autistic features, including fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and Angelman syndrome [

9]. In mice with TSC2 gene disorders, the dysfunction of which is associated with the occurrence of tuberous sclerosis, LTP is increased, while LTD is reduced [

24]. LTD changes have also been observed in mice with absent FMR1 protein, which corresponds to the fragile X syndrome, and in mice with Angelman syndrome [

13,

25]. The loss of FMR1 has been linked to an increase in protein synthesis due to increased LTD. This phenomenon has been observed in conjunction with the overproduction of immature dendritic spines, which may be a consequence of the aforementioned factors [

26,

27]. The loss of the TSC1 or TSC2 genes, in addition to affecting LTD, leads to hyperactivation of the MTORC1 protein complex, which is a component of the mTOR pathway [

28]. This pathway controls mRNA translation, thus regulating protein synthesis. Hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway has been linked to a deficiency in dendritic spine pruning, which occurs as a result of the loss of mTOR-dependent autophagy [

29]. A post-mortem examination of the brain tissue of people with ASD revealed a higher density of dendritic spines in their cerebral cortex neurons. Furthermore, it was observed that the synaptic pruning process is less effective as a result of impaired microglial activation [

30]. The involvement of neuroplasticity disorder in the pathogenesis of autism is also indicated by mutations of the SHANK gene encoding the scaffolding protein, which have been identified in ASD models, resulting in impaired dendritic spine formation and maturation [

30,

31].

Sensory Disturbances and Changes in Brain Anatomy in ASD

Disturbances in Auditory Stimulus Processing

A common symptom in patients with autism spectrum disorder is hypersensitivity to sound [

32]. Individuals diagnosed with autism have been observed to exhibit disproportionate emotional responses to a range of auditory stimuli, both quiet and loud. This condition has been referred to in the literature as “misophonia” or “phonophobia,” defined as an aversion to sound [

33]. Lucker and Doman posit a hypothesis that the hypersensitivity to sounds exhibited by children diagnosed with ASD does not stem directly from dysfunction within the auditory system. Rather, they contend that this hypersensitivity is underpinned by emotional factors. The authors contend that non-classical auditory pathways and their connections to the limbic system, which is responsible for emotions, are pivotal in this context. They emphasize that the connection between the auditory and limbic systems is located deep in the temporal lobe of the brain [

34]. The vagus nerve, which is one of the most important cranial nerves, may also play a role in the body’s response to sound and has a strong connection to the limbic system. In the context of auditory hypersensitivity, the vagus nerve amplifies these reactions, causing some people to experience severe discomfort and anxiety in response to certain sounds [

35]. One strategy employed by children with ASD to cope with overwhelming auditory stimuli is echolalia, defined as the repetition of words and sentences. In some cases, this behavior may be employed as a means of regulating their own responses to an excessively stimulative auditory environment [

36]. Disturbed speech processing and difficulties in focusing on verbal communication in the presence of background noise are also consequences of auditory hypersensitivity [

37]. Research has demonstrated that some children diagnosed with ASD encounter challenges in comprehending and producing speech. These challenges subsequently result in delays in the development of their vocabulary and the capacity to formulate coherent sentences [

38].

Hypersensitivity to Light

Photophobia or hypersensitivity to light is a common sensory phenomenon observed in autism [

39]. The visual cortex is the main area of the brain responsible for analyzing visual information. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder may have altered activity in this structure, which can result in distorted perception of visual stimuli, including light. Instead of selectively processing signals, which allows a person to ignore the background and focus on important information, the brain of a person with ASD may react to all stimuli with greater intensity [

40]. Damage to the occipital lobe can result in a number of problems, including difficulties in determining the position of objects, visual hallucinations, and difficulties in recognizing colors and movement. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder may experience similar problems, such as difficulty distinguishing relevant stimuli from the background, excessive focusing on object details, fixations on visual impressions, and excessive visual stimulation from incoming light [

41]. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study showed that people on the autism spectrum exhibit increased activity in the posterior regions of the brain, including the primary cortex (V1) and the extrastriate cortex, while showing decreased activity in the frontal regions. In the inaugural fMRI study using electroencephalography (EEG), it was observed that the ventral occipitotemporal regions showed increased activation. These brain regions are an integral part of early visual processing and are involved in the processing of visual object imagery [

42]. Other studies have shown that individuals with ASD exhibit hyperactivation of the occipital regions during visual detection tasks [

43,

44]. This abnormal brain activity may contribute to the enhancement of certain stimulus characteristics, such as increased sensitivity to light [

45].

Impaired Processing of Tactile Stimuli

ASD patients may show a reduced response to tactile stimuli, but some also experience tactile hypersensitivity [

46,

47]. Studies have shown that high-functioning children with ASD can react very strongly to touch, perceiving it as unpleasant or uncomfortable, and they also show hypersensitivity to proprioceptive stimuli and pain [

48]. However, it is not evident that they will encounter challenges with stereognosis, defined as the ability to discern tactile characteristics such as shape or texture [

2]. Therefore, an aberration in the processing of tactile stimuli results in challenges when it comes to the manipulation of objects [

49]. A multitude of studies have demonstrated that individuals diagnosed with ASD frequently exhibit atypical sensitivity to touch and an incapacity to acclimate to repeated stimuli. A potential cause is considered to be changes in GABAergic feedback loops, which can contribute to abnormal tactile sensitivity. In children with ASD who are hypersensitive to stimuli have insufficient GABA inhibition, which results in impaired processing of low-intensity stimuli [

50]. Children who demonstrate deficiencies in non-verbal communication exhibit a reduction in tactile sensitivity [

51]. The neuronal and behavioral effects of oxytocin, a hormone responsible for the creation of social bonds and also released by tactile stimuli, are weaker in people with ASD, which means that children with autism are less likely to seek tactile contact in human interactions [

52].

Incorrect Texture Processing

A significant number of children with autism have a preference or bias towards certain food textures. It has been observed that more than half of children with ASD have a food selectivity characterized by a limited range of food products they eat [

53]. An autistic person may prefer meals that are easy to swallow, with a specific texture, consistency, color or taste, from a specific plate and using specific utensils, but not those that require long chewing [

54]. It has been observed that children who were exposed to intense or stressful stimuli in early childhood, such as uncomfortable clothing, difficult environmental conditions or negative experiences with certain textures, may develop hypersensitivity as a protective mechanism against further exposure to such unpleasant stimuli [

55]. Individuals with heightened sensory sensitivity frequently exhibit challenges in proprioception, defined as the awareness of one’s own body in space. In the event of an impaired proprioceptive sense, bodily reactions to tactile stimuli may be amplified, leading to heightened sensitivity to various textures [

56] The sensory cortex, situated within the parietal lobe of the brain, is the region responsible for receiving and processing tactile stimuli. In typical cases, the brain analyzes tactile stimuli, filtering and normalizing them so that the touch of textures, such as a rough surface or soft material, is perceived according to its intensity and character [63]. In individuals with heightened sensitivity to textures, the sensory cortex may exhibit increased reactivity, leading to the interpretation of stimuli as more intense or irritating than they actually are. This heightened sensitivity to textures may be accompanied by impaired communication between the sensory cortex and other brain regions, including the limbic system [

33]. In addition, neurotransmitters play an important role in the regulation of sensory signals. In cases of increased sensitivity to textures, there may be an imbalance of neurotransmitters, leading to an inability of the nervous system to adequately modulate responses to stimuli. Research has demonstrated that the decreased level of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA can result in sensory signals being perceived more intensely due to the absence of a mechanism to dampen their intensity [

57].

Inadequate Pain Response

Incorrect processing of tactile stimuli can also manifest as an elevated pain threshold, which can result in frequent injuries that are disregarded by the child [

58]. Some individuals with autism may only react to stronger pain stimuli [

59]. The phenomenon of hypersensitivity to pain in ASD can be understood as the result of a complex interaction between neurological, sensory and psychological factors [

60]. The amygdala, which plays a role in emotional processes and pain reactions, can be either overactive or underactive in individuals with autism [

61]. In contrast, the insula, which is responsible for the subjective perception of pain, may show reduced activity, thus reducing the perception of pain reaction [

62]. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, endorphins and dopamine, which play a role in the pain perception process, may also be relevant in its disturbed perception [

50,

63]. Endorphins, in particular, have been shown to reduce the pain response and, over time, can cause pleasant sensations for stimuli perceived as unpleasant by neurotypical people. Increased endorphin levels are observed in children with ASD who engage in self-biting, suggesting that they may experience a lack of pain perception and even derive pleasure from this act. This is thought to be due to the activation of the reward center in the brain [

64].

The complexity of sensory integration disorders emphasizes the heterogeneity of autism spectrum disorders. Selected elements of the basis of these disruptions are presented in

Table 1.

Conventional Sensory Therapies Based on Neuroplasticity

The knowledge of neuroplasticity and the pathogenesis of somatosensory disorders in autism has been instrumental in the development of therapeutic interventions that are designed to support patients with ASD and their families.

Sensory Integration Therapy

Sensory integration therapy (SIT) is a therapy based on the theory that adaptive behavior is influenced by the relationship between behavior and neurological processes in the central nervous system [

71]. It has been hypothesized that this therapeutic modality facilitates the perception of a variety of sensory stimuli, encompassing visual, auditory, tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular stimuli. This, in turn, assists the child in engaging with their surroundings in an effective manner. Over time, this process supports healthy cognitive, motor, behavioral and emotional development. To date, the effectiveness of SIT has been controversial [

72,

73]. The main reason for the ongoing controversy is the inconsistency in how sensory integration therapy is applied in each study. SIT has proven effective in several conditions, such as cerebral palsy, ASD, ADHD, intellectual disability, and developmental disorders. However, the effect size was greatest for cerebral palsy, followed by autistic disorders, and then ADHD. The most effective therapy for ASD, according to the results of a meta-analysis published in the World Journal of Clinical Cases, is 1:1 therapy with a therapist or a therapy session lasting 40 minutes. A greater effect was observed in the areas of social skills, adaptive behavior and sensory processing functions [

71].

Snoezelen Therapy

Snoezelen therapy, also called controlled multisensory environment (MSE), takes place in a sensory room that has been designed to stimulate multiple senses through the use of lighting effects, colors, sounds, music, scents, and other sensory stimuli. It is believed that MSE improves cognitive abilities and aids learning, while encouraging eye contact, shared attention, shared enjoyment and better communication, all of which help to reduce restrictive and repetitive behaviors [

74]. This allows the child to experience and manage their sensory reactions, gradually increasing their ability to process and integrate sensory information from the environment. The few studies conducted to date on interventions in ASD have shown improvements in sustained attention, developmental skills and challenging behaviors [

75].

Animal-Assisted Therapy

Animal-assisted intervention (AAI) involves incorporating animals such as dogs, horses, dolphins, rabbits, guinea pigs and llamas into the therapeutic process as part of autism treatment. It is one of the most promising therapies aimed at repairing the underlying impairments in children with ASD. [

76,

77,

78]. Moreover, researchers observed that the rhythmic movement of horse riding can specifically stimulate the vestibular system in children with ASD, which can improve speech production and support better learning outcomes [

78,

79]. At the same time, riders have to actively manage their body movements, which strengthens their ability to exercise voluntary control and improves non-verbal communication skills. Another meta-analysis on nature-based interventions (NBI) showed a positive relationship between horse-assisted therapy and goal attainment, as well as between nature-based therapy and parent-child relationships. Furthermore, experimental learning has been indicated as a way to improve the short-term sensory and behavioral outcomes in children with ASD [

80].

Music Therapy

Several studies have shown that MT can effectively improve the social skills of children with ASD [

81]. Individuals with ASD have been observed to demonstrate activation in the cortical and subcortical regions of the brain during exposure to both happy and sad music. This activation is typically observed to a greater extent than in individuals without ASD, and is particularly pronounced in response to non-musical emotional stimuli [

82]. In another review, MT did not show improvement in symptom severity and receptive vocabulary, but significant improvements were observed in brain connectivity, family quality of life, and social communication skills after 8–12 weeks of MT [

83]. The results indicate that MT can be effective in increasing social interaction among children with ASD. A comfortable music program can support children in acquiring social skills and adapting to society. However, the number of eligible studies is small, so all conclusions regarding MT as an ASD therapy should be applied with caution.

Modern Sensory Integration Therapies

Virtual Reality/Augmented Reality Technologies

Virtual reality (VR) technologies can accurately present sensory stimuli and be integrated with human sensing technologies to automatically detect sensory responses, and thus can improve the objectivity and sensitivity of sensory assessment compared to traditional questionnaire-based methods. Modern therapies using virtual reality technology are finding increasing use in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Specifically, HMD with motion-capture VR games has proven to be an effective tool in the treatment of pain of various etiologies, and Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) has shown efficacy in the treatment of ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders [

84]. Virtual reality-incorporated cognitive behavioral therapy (VR-CBT) had positive effects on sensory and motor functions in autism spectrum disorder [

85].

Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids have been shown to act via CB1 and CB2 receptors, and there is also evidence of a cannabinoid receptor in the brain. These receptors modulate signaling pathways, regulating synaptic transmission and plasticity. The impact of cannabinoids on the hippocampus, locomotor activity, and reward pathways is well-documented, and their analgesic properties are widely recognized. Additionally, cannabinoids have been shown to play a protective role in cases of neurodegeneration and brain damage [

86]. Some studies point to a role for the use of cannabinoids in the treatment of ASD, with treatment effects including a reduction in symptoms of hyperactivity, tantrums and self-injury, sleep disturbances, anxiety, agitation and depression, as well as improvements in cognitive function, sensory sensitivity, attention, social interaction and language. However, randomized trials are lacking to provide better evidence of such therapeutic intervention [

87].

Bioneurofeedback

The efficacy of EEG-based neurofeedback therapy is predicated on the brain’s neuroplasticity, which is engineered to instigate enduring self-regulation of modified neuronal activity [

88]. The practice of bioneurofeedback involves the acquisition of skills that enable individuals to self-regulate their brain’s oscillatory activity, thereby exerting a direct influence on the central nervous system [

89]. The utilization of bioneurofeedback in the management of pain and excessive sensory activation has been a subject of interest in recent research [

90,

91,

92]. Research indicates changes in frontal cortex activity and an increase in life satisfaction after bioneurofeedback in adults with sensory hyperactivation, but at the same time, no significant changes were observed in alpha brainwaves, which are key to assessing the effectiveness of neurofeedback. The researchers suggest that further research be conducted to evaluate other oscillatory bands [

90].

Brain Stimulation Techniques

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive brain stimulation technique in which a variable magnetic field is used to induce a small electric current within the brain [

93]. TMS can be used as an ASD biomarker because most studies indicate increased hyperplasticity in these individuals [

94]. The application of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS), which utilizes transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), has been demonstrated to be an effective method of restoring sensory functions in stroke patients [

95]. In the context of autism, the efficacy of NIBS methods in addressing repetitive behaviors and enhancing sociability, as well as executive and cognitive functions, has been demonstrated [

96].

Summary

Sensory dysregulation are a key aspect of autism, affecting the daily functioning of individuals diagnosed with ASD. These deficits include hypersensitivity or insensitivity to sensory stimuli, difficulties in processing information, and impaired motor coordination. They affect adaptability, social interactions and cognitive processes, which underscores their importance in the diagnosis and treatment of autism. The neurobiological basis in autism includes abnormalities in brain structures responsible for sensory processing, such as the somatosensory cortex, thalamus and connections between the sensory cortex and other areas of the brain. These dysfunctions are linked to abnormalities in neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize under the influence of experience. In autism, both reduced synaptic plasticity and overcompensation in certain areas of the brain are observed, which can lead to abnormal processing of stimuli.

Therapies based on neuroplasticity play a key role in improving the functioning of people with autism spectrum disorder and abnormal sensory integration. Neuroplasticity, defined as the brain’s capacity for reorganization and adaptation, underlies both conventional therapeutic methods and recent advancements in the field. Therapeutic effects are achieved by Ayers Sensory Integration Therapy, music therapy, Snoezelen therapy or animal-assisted therapy. Advances in neuroscience have led to the development of new methods, such as neurofeedback training, which uses EEG to regulate brain activity through feedback mechanisms that support self-regulation and attention, brain stimulation techniques which influence synaptic plasticity and can improve cognitive and behavioral functions. Virtual reality-based therapy engages patients in controlled therapeutic environments to support the learning of social and sensory skills, while interventions based on games and mobile applications are tailored to individual needs, promoting neuroplasticity. A potential treatment option could be the use of cannabinoids, which are also responsible for changes in synaptic transmission and may be involved in neuromodulation.

Despite promising results, there are several limitations, including the lack of standardized criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of many emerging therapies, the limited number of randomized controlled trials, and the need for long-term studies to evaluate the durability of therapeutic effects. The heterogeneity of ASD symptoms complicates the standardization of therapeutic approaches, while individual factors such as age, level of functioning and comorbidities, significantly affect the results of therapy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M. C. Lai, M. V. Lombardo, and S. Baron-Cohen, “Autism,” Lancet, vol. 383, no. 9920, pp. 896–910, 2014. [CrossRef]

- I. Riquelme, S. M. Hatem, and P. Montoya, “Abnormal Pressure Pain, Touch Sensitivity, Proprioception, and Manual Dexterity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders,” Neural Plast, vol. 2016, p. 1723401, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Sato, N. Nakai, S. Fujima, K. Y. Choe, and T. Takumi, “Social circuits and their dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder,” Mol Psychiatry, vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 3194–3206, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Pardo and C. G. Eberhart, “The Neurobiology of Autism,” Brain Pathology, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 434, Oct. 2007. [CrossRef]

- N. V. Gulyaeva, “Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity: An Expanding Universe,” Biochemistry (Mosc), vol. 82, no. 3, pp. 237–242, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Johnston, A. Ishida, W. N. Ishida, H. B. Matsushita, A. Nishimura, and M. Tsuji, “Plasticity and injury in the developing brain,” Brain Dev, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Dennis, B. J. Spiegler, J. J. Juranek, E. D. Bigler, O. C. Snead, and J. M. Fletcher, “Age, plasticity, and homeostasis in childhood brain disorders,” Neurosci Biobehav Rev, vol. 37, no. 10 Pt 2, pp. 2760–2773, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Batool, H. Raza, J. Zaidi, S. Riaz, S. Hasan, and N. I. Syed, “Synapse formation: from cellular and molecular mechanisms to neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders,” J Neurophysiol, vol. 121, no. 4, pp. 1381–1397, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Y. Ismail, A. Fatemi, and M. V. Johnston, “Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain,” Eur J Paediatr Neurol, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 23–48, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Lane and R. C. Schaaf, “Examining the Neuroscience Evidence for Sensory-Driven Neuroplasticity: Implications for Sensory-Based Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents,” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 375–390, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Fagiolini and J. J. Leblanc, “Autism: a ‘critical period’ disorder?,” Neural Plast, vol. 2011, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. M. S. Sears and S. J. Hewett, “Influence of glutamate and GABA transport on brain excitatory/inhibitory balance,” Exp Biol Med (Maywood), vol. 246, no. 9, pp. 1069–1083, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Kourdougli et al., “Improvement of sensory deficits in fragile X mice by increasing cortical interneuron activity after the critical period,” Neuron, vol. 111, no. 18, pp. 2863-2880.e6, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, X. Wang, S. Zhang, and F. Han, “Neuroplasticity of children in autism spectrum disorder,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 15, p. 1362288, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Montanari, G. Martella, P. Bonsi, and M. Meringolo, “Autism Spectrum Disorder: Focus on Glutamatergic Neurotransmission,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 7, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Nisar et al., “Genetics of glutamate and its receptors in autism spectrum disorder,” Mol Psychiatry, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 2380–2392, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zheng, T. Zhu, Y. Qu, and D. Mu, “Blood Glutamate Levels in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 7, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. R. Monday, H. C. Wang, and D. E. Feldman, “Circuit-level theories for sensory dysfunction in autism: convergence across mouse models,” Front Neurol, vol. 14, p. 1254297, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Purves et al., “Long-Term Synaptic Potentiation,” 2001, Accessed: Dec. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10878/.

- C. Lüscher and K. M. Huber, “Group 1 mGluR-dependent synaptic long-term depression (mGluR-LTD): mechanisms and implications for circuitry & disease,” Neuron, vol. 65, no. 4, p. 445, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Kossut, “Basic mechanism of neuroplasticity,” Neuropsychiatria i Neuropsychologia/Neuropsychiatry and Neuropsychology, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Nelson and V. Valakh, “Excitatory/Inhibitory Balance and Circuit Homeostasis in Autism Spectrum Disorders,” Neuron, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 684–698, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. M. S. Sears and S. J. Hewett, “Influence of glutamate and GABA transport on brain excitatory/inhibitory balance,” Exp Biol Med (Maywood), vol. 246, no. 9, pp. 1069–1083, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Mullins, G. Fishell, and R. W. Tsien, “Unifying Views of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Consideration of Autoregulatory Feedback Loops,” Neuron, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 1131–1156, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Pignatelli et al., “Changes in mGlu5 receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity and coupling to homer proteins in the hippocampus of Ube3A hemizygous mice modeling angelman syndrome,” J Neurosci, vol. 34, no. 13, pp. 4558–4566, 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Huguet, E. Ey, and T. Bourgeron, “The genetic landscapes of autism spectrum disorders,” Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, vol. 14, pp. 191–213, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Y. Lo and K. O. Lai, “Dysregulation of protein synthesis and dendritic spine morphogenesis in ASD: Studies in human pluripotent stem cells,” Mol Autism, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–9, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Winden, D. Ebrahimi-Fakhari, and M. Sahin, “Abnormal mTOR Activation in Autism,” Annu Rev Neurosci, vol. 41, pp. 1–23, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Tang et al., “Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits,” Neuron, vol. 83, no. 5, pp. 1131–1143, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Durand et al., “SHANK3 mutations identified in autism lead to modification of dendritic spine morphology via an actin-dependent mechanism,” Mol Psychiatry, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 71–84, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Leblond et al., “Meta-analysis of SHANK Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments,” PLoS Genet, vol. 10, no. 9, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Rotschafer, “Auditory Discrimination in Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Front Neurosci, vol. 15, p. 651209, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Kirby, V. A. Dickie, and G. T. Baranek, “Sensory experiences of children with autism spectrum disorder: In their own words,” Autism, vol. 19, no. 3, p. 316, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Lucker and A. Doman, “Neural Mechanisms Involved in Hypersensitive Hearing: Helping Children with ASD Who Are Overly Sensitive to Sounds,” Autism Res Treat, vol. 2015, no. 1, p. 369035, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Porges and G. F. Lewis, “The polyvagal hypothesis: common mechanisms mediating autonomic regulation, vocalizations and listening,” Handb Behav Neurosci, vol. 19, no. C, pp. 255–264, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Xie, E. Pascual, and T. Oakley, “Functional echolalia in autism speech: Verbal formulae and repeated prior utterances as communicative and cognitive strategies,” Front Psychol, vol. 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Hernandez et al., “Social Attention in Autism: Neural Sensitivity to Speech Over Background Noise Predicts Encoding of Social Information,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 11, p. 517323, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Sánchez Pérez, A. Nordahl-Hansen, and A. Kaale, “The Role of Context in Language Development for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Front Psychol, vol. 11, p. 563925, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Thye, H. M. Bednarz, A. J. Herringshaw, E. B. Sartin, and R. K. Kana, “The impact of atypical sensory processing on social impairments in autism spectrum disorder,” Dev Cogn Neurosci, vol. 29, p. 151, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Just, V. L. Cherkassky, T. A. Keller, and N. J. Minshew, “Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity,” Brain, vol. 127, no. Pt 8, pp. 1811–1821, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. I. Zdrowie et al., “‘Neurological disorders in autism,’” vol. 1, 2015.

- S. M. Kosslyn, W. L. Thompson, I. J. Klm, and N. M. Alpert, “Topographical representations of mental images in primary visual cortex,” Nature, vol. 378, no. 6556, pp. 496–498, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Lucker and A. Doman, “Neural Mechanisms Involved in Hypersensitive Hearing: Helping Children with ASD Who Are Overly Sensitive to Sounds,” Autism Res Treat, vol. 2015, pp. 1–8, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Damarla et al., “Cortical underconnectivity coupled with preserved visuospatial cognition in autism: Evidence from an fMRI study of an embedded figures task,” Autism Res, vol. 3, no. 5, p. 273, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. M. Manjaly et al., “Neurophysiological correlates of relatively enhanced local visual search in autistic adolescents,” Neuroimage, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 283–291, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- T. Grandin, “An Inside View of Autism,” High-Functioning Individuals with Autism, pp. 105–126, 1992. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Baranek, L. G. Foster, and G. Berkson, “Tactile defensiveness and stereotyped behaviors,” Am J Occup Ther, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 91–95, 1997. [CrossRef]

- M. Elwin, L. Ek, A. Schröder, and L. Kjellin, “Autobiographical accounts of sensing in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism,” Arch Psychiatr Nurs, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 420–429, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. A. R. Sacrey, T. Germani, S. E. Bryson, and L. Zwaigenbaum, “Reaching and grasping in autism spectrum disorder: A review of recent literature,” Front Neurol, vol. 5 JAN, p. 65872, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao et al., “GABAergic System Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorders,” Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 9, p. 781327, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Balasco, G. Provenzano, and Y. Bozzi, “Sensory Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Focus on the Tactile Domain, From Genetic Mouse Models to the Clinic,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 10, p. 464344, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Daniels et al., “Effects of multiple-dose intranasal oxytocin administration on social responsiveness in children with autism: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial,” Mol Autism, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Schreck and K. Williams, “Food preferences and factors influencing food selectivity for children with autism spectrum disorders,” Res Dev Disabil, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 353–363, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Park, S. J. Choi, Y. Kim, M. S. Cho, Y. R. Kim, and J. E. Oh, “Mealtime Behaviors and Food Preferences of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Foods, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 49, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Thye, H. M. Bednarz, A. J. Herringshaw, E. B. Sartin, and R. K. Kana, “The impact of atypical sensory processing on social impairments in autism spectrum disorder,” Dev Cogn Neurosci, vol. 29, p. 151, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Foss-Feig, J. L. Heacock, and C. J. Cascio, “TACTILE RESPONSIVENESS PATTERNS AND THEIR ASSOCIATION WITH CORE FEATURES IN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS,” Res Autism Spectr Disord, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 337, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Robertson, E. M. Ratai, and N. Kanwisher, “Reduced GABAergic Action in the Autistic Brain,” Curr Biol, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 80–85, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- O. V. Bogdanova et al., “The Current View on the Paradox of Pain in Autism Spectrum Disorders,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 13, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Allely, “Pain sensitivity and observer perception of pain in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder,” ScientificWorldJournal, vol. 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- I. Riquelme, S. M. Hatem, and P. Montoya, “Abnormal Pressure Pain, Touch Sensitivity, Proprioception, and Manual Dexterity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders,” Neural Plast, vol. 2016, no. 1, p. 1723401, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang and X. Li, “A revisit of the amygdala theory of autism: Twenty years after,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 183, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Nomi, I. Molnar-Szakacs, and L. Q. Uddin, “Insular function in autism: Update and future directions in neuroimaging and interventions,” Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, vol. 89, pp. 412–426, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Wise and C. J. Jordan, “Dopamine, behavior, and addiction,” J Biomed Sci, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 83, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Eden, P. J. De Vries, J. Moss, C. Richards, and C. Oliver, “Self-injury and aggression in tuberous sclerosis complex: cross syndrome comparison and associated risk markers,” J Neurodev Disord, vol. 6, no. 1, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Lane et al., “Neural Foundations of Ayres Sensory Integration®,” Brain Sci, vol. 9, no. 7, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Markham and W. T. Greenough, “Experience-driven brain plasticity: beyond the synapse,” Neuron Glia Biol, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 351–363, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Reynolds, S. J. Lane, and L. Richards, “Using animal models of enriched environments to inform research on sensory integration intervention for the rehabilitation of neurodevelopmental disorders,” J Neurodev Disord, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 120–132, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Parham et al., “Development of a fidelity measure for research on the effectiveness of the Ayres Sensory Integration intervention,” Am J Occup Ther, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 133–142, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Pfeiffer, K. Koenig, M. Kinnealey, M. Sheppard, and L. Henderson, “Effectiveness of sensory integration interventions in children with autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study,” Am J Occup Ther, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 76–85, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Raditha, S. Handryastuti, H. D. Pusponegoro, and I. Mangunatmadja, “Positive behavioral effect of sensory integration intervention in young children with autism spectrum disorder,” Pediatr Res, vol. 93, no. 6, pp. 1667–1671, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Oh et al., “Effectiveness of sensory integration therapy in children, focusing on Korean children: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” World J Clin Cases, vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 1260–1271, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Barton, B. Reichow, A. Schnitz, I. C. Smith, and D. Sherlock, “A systematic review of sensory-based treatments for children with disabilities,” Res Dev Disabil, vol. 37, pp. 64–80, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Leong, M. Carter, and J. Stephenson, “Systematic review of sensory integration therapy for individuals with disabilities: Single case design studies,” Res Dev Disabil, vol. 47, pp. 334–351, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Fava and K. Strauss, “Multi-sensory rooms: comparing effects of the Snoezelen and the Stimulus Preference environment on the behavior of adults with profound mental retardation,” Res Dev Disabil, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 160–171, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. De Domenico et al., “Exploring the Usefulness of a Multi-Sensory Environment on Sensory Behaviors in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder,” J Clin Med, vol. 13, no. 14, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Xiao, K. Shinwari, S. Kiselev, X. Huang, B. Li, and J. Qi, “Effects of Equine-Assisted Activities and Therapies for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 20, no. 3, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Esposito, S. Mccune, J. A. Griffin, and V. Maholmes, “Directions in Human–Animal Interaction Research: Child Development, Health, and Therapeutic Interventions,” Child Dev Perspect, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 205–211, Sep. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhao, S. Chen, Y. You, Y. Wang, and Y. Zhang, “Effects of a Therapeutic Horseback Riding Program on Social Interaction and Communication in Children with Autism,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 1–11, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Katz-Nave, Y. Adini, O. E. Hetzroni, and Y. S. Bonneh, “Sequence Learning in Minimally Verbal Children With ASD and the Beneficial Effect of Vestibular Stimulation,” Autism Research, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 320–337, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. S. N. Fan, W. H. C. Li, L. L. K. Ho, L. Phiri, and K. C. Choi, “Nature-Based Interventions for Autistic Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” JAMA Netw Open, vol. 6, no. 12, p. E2346715, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghasemtabar, M. Hosseini, I. Fayyaz, S. Arab, H. Naghashian, and Z. Poudineh, “Music therapy: An effective approach in improving social skills of children with autism,” Adv Biomed Res, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 157, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Caria, P. Venuti, and S. De Falco, “Functional and dysfunctional brain circuits underlying emotional processing of music in autism spectrum disorders,” Cereb Cortex, vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 2838–2849, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Gassner, M. Geretsegger, and J. Mayer-Ferbas, “Effectiveness of music therapy for autism spectrum disorder, dementia, depression, insomnia and schizophrenia: update of systematic reviews,” Eur J Public Health, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 27–34, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Cieślik, J. Mazurek, S. Rutkowski, P. Kiper, A. Turolla, and J. Szczepańska-Gieracha, “Virtual reality in psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of reviews,” Complement Ther Med, vol. 52, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Chu et al., “Effects of a Nonwearable Digital Therapeutic Intervention on Preschoolers With Autism Spectrum Disorder in China: Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial,” J Med Internet Res, vol. 25, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Irving, M. G. Rae, and A. A. Coutts, “Cannabinoids on the brain,” ScientificWorldJournal, vol. 2, pp. 632–648, 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. A. da Silva Junior et al., “Cannabis and cannabinoid use in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review,” Trends Psychiatry Psychother, vol. 44, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Ros, B. J. Baars, R. A. Lanius, and P. Vuilleumier, “Tuning pathological brain oscillations with neurofeedback: a systems neuroscience framework,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 8, no. DEC, p. 1008, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Bagdasaryan and M. Le Van Quyen, “Experiencing your brain: neurofeedback as a new bridge between neuroscience and phenomenology,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 7, no. OCT, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Hamed, L. Mizrachi, Y. Granovsky, G. Issachar, S. Yuval-Greenberg, and T. Bar-Shalita, “Neurofeedback Therapy for Sensory Over-Responsiveness-A Feasibility Study,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 22, no. 5, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Patel et al., “Effects of neurofeedback in the management of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials,” Eur J Pain, vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 1440–1457, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Mayaud et al., “Alpha-phase synchrony EEG training for multi-resistant chronic low back pain patients: an open-label pilot study,” Eur Spine J, vol. 28, no. 11, pp. 2487–2501, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Barker, R. Jalinous, and I. L. Freeston, “Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex,” Lancet, vol. 1, no. 8437, pp. 1106–1107, May 1985. [CrossRef]

- A. Jannati, M. A. Ryan, H. L. Kaye, M. Tsuboyama, and A. Rotenberg, “Biomarkers obtained by transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurodevelopmental disorders,” J Clin Neurophysiol, vol. 39, no. 2, p. 135, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Chen et al., “Non-invasive brain stimulation effectively improves post-stroke sensory impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” J Neural Transm (Vienna), vol. 130, no. 10, pp. 1219–1230, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Khaleghi, H. Zarafshan, S. R. Vand, and M. R. Mohammadi, “Effects of Non-invasive Neurostimulation on Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review,” Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 527–552, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Selected abnormalities responsible for the pathogenesis of sensory integration disorders in autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Table 1.

Selected abnormalities responsible for the pathogenesis of sensory integration disorders in autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

| Neuroanatomical and neurotransmitter abnormalities in sensory processing disorders in ASD |

|---|

| Incorrect processing of auditory stimuli |

Hypersensitivity to light |

Incorrect processing of tactile stimuli |

Incorrect texture processing |

Inadequate pain response |

Abnormalities in the limbic system [35]

Abnormal vagus nerve response [36] |

Abnormalities in the visual cortex [41]

Abnormalities in the primary cortex (V1) and the extrastriate cortex [43]

Decreased activity in the frontal regions [43]

Hyperactivation of the occipital regions [44,45] |

Insufficient GABA inhibition [51]

Abnormal oxytocin level [53] |

Increased reactivity of the sensory cortex [63]

Impaired communication between the sensory cortex and other brain regions, including the limbic system [33]

Decreased level of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA [57] |

Overactive or underactive amygdala [61]

Insula reduced activity [62]

Increased endorphin levels [64] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).