1. Introduction

With the global industrialization process and social and economic development, the amount of municipal solid waste(MSW) is increasing significantly [

1,

2]. This rapid growth has brought serious challenges to municipal solid waste treatment [

3]. In this context, Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) technology stands out as a widely adopted treatment method [

4]. MSWI is an efficient waste treatment method. The core of the technology is to convert municipal solid waste into ash, flue gas and recoverable heat energy through a high-temperature combustion process [

5]. This technology can not only greatly reduce the volume of waste, but also effectively control the generation of secondary pollution, and can also realize the reuse of resources [

6]. The MSWI process consists of six stages: solid waste fermentation, solid waste incineration, waste heat exchange, steam generation, flue gas purification, and flue gas emission [

7]. Among them, the solid waste incineration stage occupies a core position in the MSWI process, which is not only an effective way to reduce and recycle waste, but also its technical control directly affects the flue gas purification and emission quality [

8]. Reasonable regulation of the incineration process can reduce the generation of harmful substances, ensure that environmental standards are met, and protect the environment and public health [

9]. The essence of solid waste combustion is a thermochemical treatment process, its core lies in the oxidation reaction under high temperature conditions, the combustible substances in solid waste into gaseous products (such as carbon dioxide, water vapor, nitrogen, etc.) and a small amount of solid residues (such as ash). This process not only realizes the volume reduction and harmless treatment of waste, but also is accompanied by the release and conversion of energy, which provides the basis for subsequent energy recovery and utilization [

10].

Therefore, the reasonable regulation of solid waste incineration process is particularly important. However, this process still faces multiple challenges. Among them, the instability of combustion state is a particularly intractable problem, which directly leads to the difficulty of pollutant discharge to meet the standards [

11]. At the same time, it also exacerbates the problems such as slag, ash accumulation and equipment corrosion in the furnace, and may even cause safety accidents such as furnace explosion in serious cases. In view of this, it is particularly important to maintain the combustion stability during the incineration process [

12], which is directly related to the efficiency and environmental effectiveness of the entire treatment process. It is worth noting that the operation of many current MSWI facilities still relies on manual intuitive judgment of the flame burning state during solid waste incineration to adjust the control strategy. Although this method is practical to some extent, it is easily limited by personal experience, subjective judgment and insufficient intelligence level, so it is difficult to meet the urgent needs of MSWI process optimization operation. Therefore, exploring and constructing a combustion state recognition model that can not only adapt to the complex and variable environment of MSWI, but also have a high degree of robustness has become an important direction of current research. The construction of this model not only requires accurate identification of the combustion state, but also should be able to effectively guide the adjustment of the control strategy to ensure the efficient and stable operation of the MSWI process and meet the strict environmental emission standards at the same time.

In recent years, artificial intelligence technology has been more and more widely used in the field of MSWI combustion state recognition [

13]. For example, Duan et al. [

14] proposed a model to identify burning conditions in MSWI process based on multi-scale color moment features and Random Forest (RF). Firstly, the image is preprocessed by dehazing and denoising. Then, based on the pre-set scale, the color moment features of flame images at different scales are extracted by using sliding Windows. Finally, taking the classification accuracy as the evaluation criterion, the RF algorithm based on feature selection was used to realize the accurate identification of the burning state. However, due to the scarcity of abnormal burning state images and the high labeling cost, it is difficult to obtain enough image burning state anomalies. Therefore, Guo et al. [

15] proposed a deep convolutional generation based burning State adversarial Network (DCGAN) for abnormal image generation. Moreover, Ding et al. [

16] introduced the typical MSWI process and summarized the main control requirements. Then, the related control methods were summarized and the applicability and development status were analyzed. Finally, the main problems and difficulties in the current MSWI process control were summarized. At the same time, another method by Zhang et al. [

17] proposed a combustion state recognition model for MSWI process based on convolutional neural network. Guo et al. [

18] constructed a flame image dataset classified according to the position of the burning line of the flame in the MSWI burning image, and used a variety of deep learning models to verify the feasibility of flame burning state recognition, which provides a certain reference for subsequent research work. Tian et al. [

19] firstly enhanced the original flame image by data enhancement methods such as rotation and adding noise to expand the scale of labeled samples and overcome the problem of high cost of manual labeling. Then, the VGG19 model pre-trained on ImageNet is used as the base model, and the output of the last layer of the middle layer is used as the model output. By enhancing the flame image data set and fine-tuning the model parameters, feature transfer learning is realized. Pan et al. [

20] chose Lenet-5 as the recognition model for flame burning state recognition. In order to obtain a suitable CNN model to automatically extract the flame image features, the authors tested the influence of multiple CNN networks on the flame image features and obtained the optimal structure setting of the CNN network. Moreover, Pan et al. [

21] combined the experience of industry experts and the research results in related fields to study the construction of the classification standard and benchmark database of the flame combustion state of waste disposal. The combustion classification criteria based on normal burning, partial burning, channeling burning and smoldering are expounded, and the flame combustion state image database for machine learning is constructed. Finally, based on various classical algorithms in the field of machine vision, the flame combustion image database is modeled and tested. Motivated by this, paper [

22] used deep Forest Classification with Improved ViT (VIT-IDFC) algorithm to identify burning states. Based on the transformer encoding layer of the pre-trained ViT model, multi-layer visual transformation features are extracted from the flame image. The experience of domain experts is used to select deep features. By taking the selected ViT visual transformation features and the original flame image as the input of the cascade forest, an IDFC model is constructed to identify the flame burning state. Yang et al. [

23] proposed a YOLOv5-based method for MSWI process burning state recognition, which uses a backbone network for feature extraction and a head layer for state recognition. Guo et al. [

24] performed data augmentation through DCGAN, then expanded the sample again through non-generative data augmentation, and finally constructed a convolutional neural network to identify the burning state. Hu et al. [

25] used artificial multi-exposure image fusion dehazing algorithm, feature normalization, trap filter, median filter and other preprocessing means to dehaze and represent the flame image. Then, multiple features such as brightness, flame, color and principal component were extracted from the flame image to represent the multi-view image, and the multi-view features were reduced based on mutual information. Finally, a burning state recognition model was constructed based on image features and deep forest model.

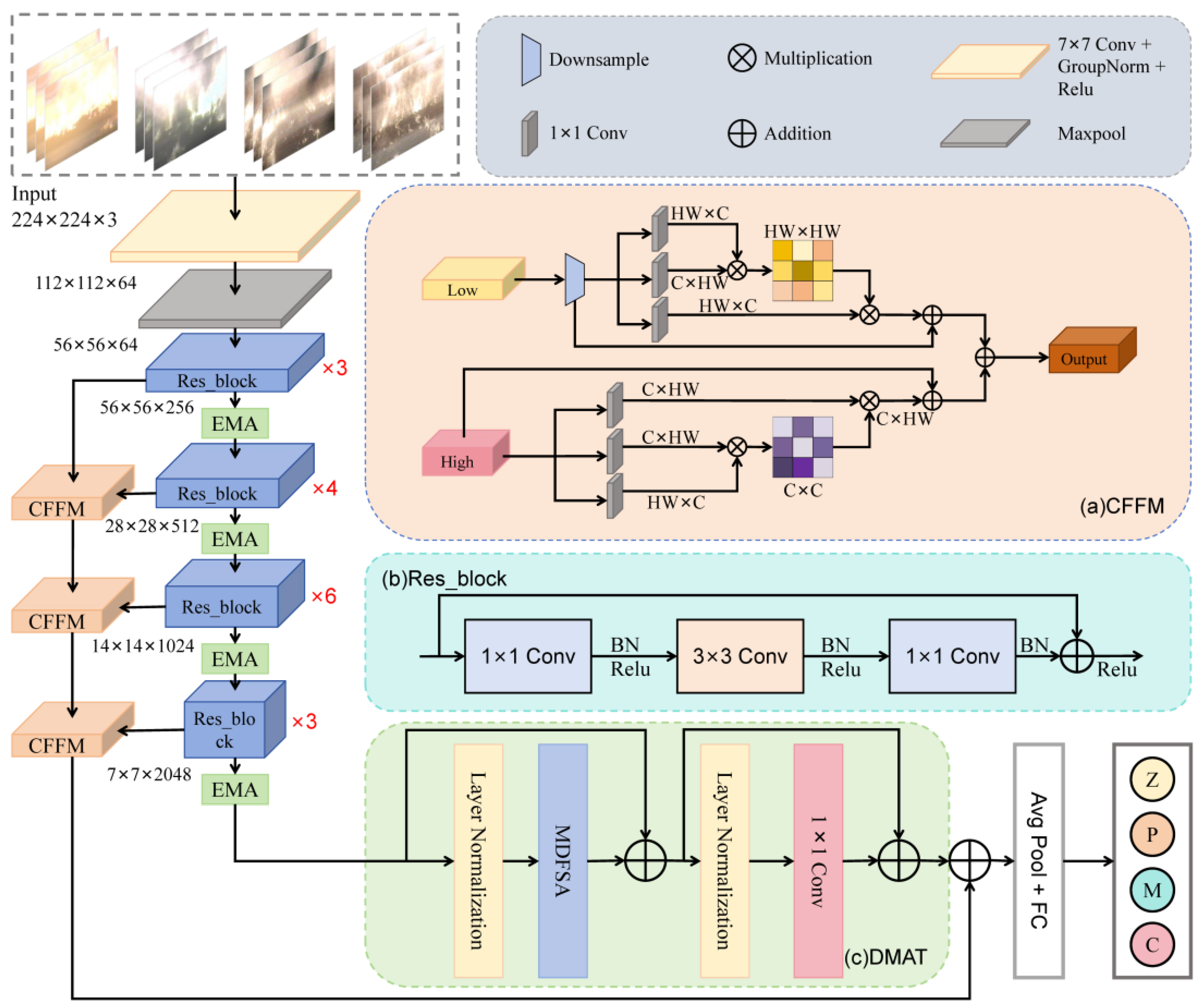

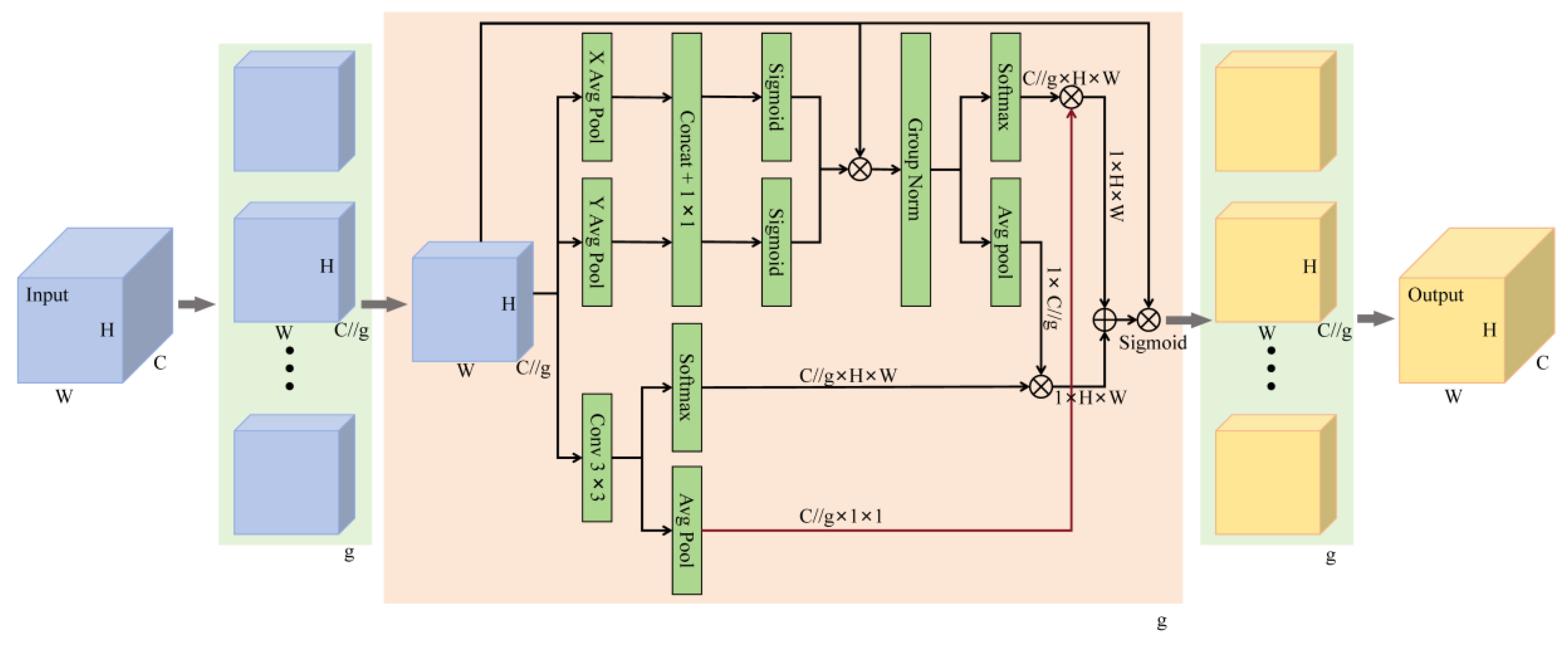

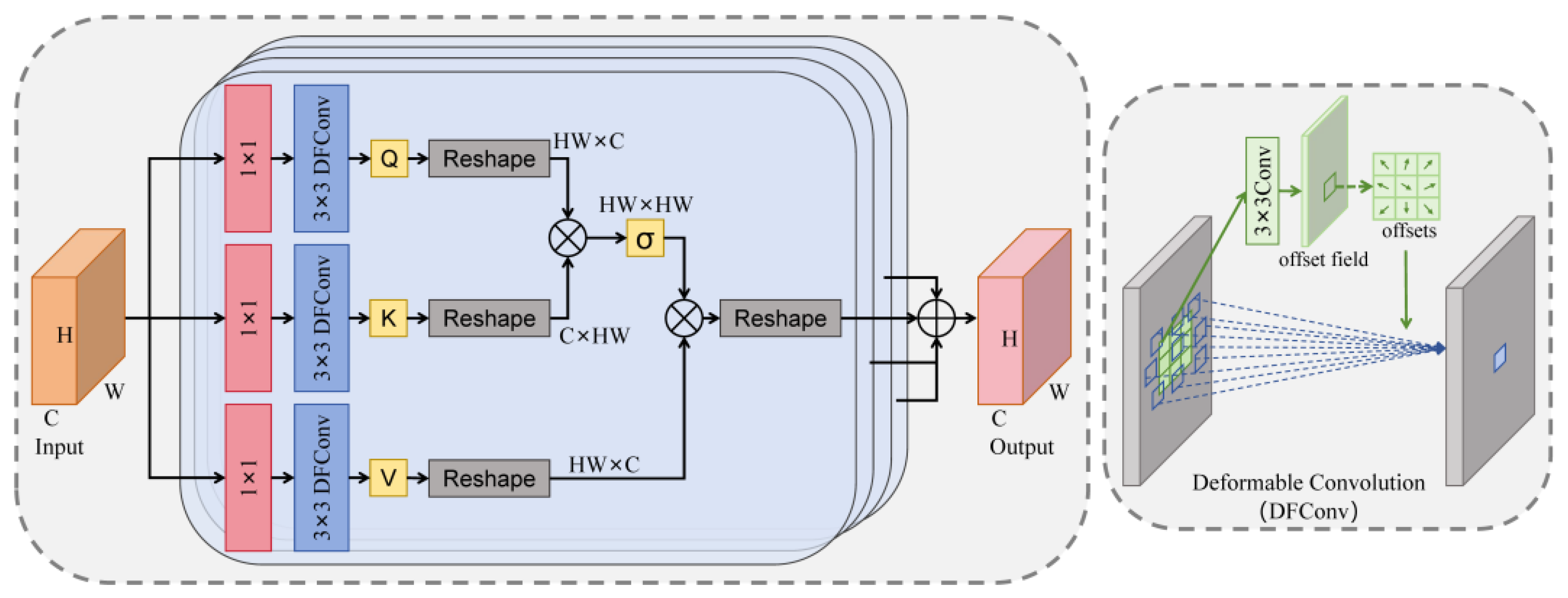

The above studies show that artificial intelligence techniques, especially deep learning-based methods, are able to show good performance in the existing MSWI burning state recognition due to their strong feature learning and expression capabilities. However, there are still some problems in the existing recognition methods. For example, the burning flame of MSWI image is diverse, the shape is complex, the size is also very different, and the boundary with the background image is fuzzy, which leads to the model cannot fully extract effective features for recognition. Aiming at the above problems, we propose M3RTNet model, and use three different feature enhancement strategies to enhance the feature extraction ability of the model, so as to better extract flame burning features. The main contributions are as follows: (1) We use the Res-Transformer structure as the backbone network, and combine the local feature extraction ability of Resnet and the global feature extraction advantage of Transformer to extract local flame combustion features and global information. (2) An efficient multi-scale attention(EMA) module is introduced into the Resnet network, and a multi-scale parallel sub-network is used to establish the long and short dependence relationship to strengthen the recognition ability of the flame burning area, so as to improve the classification performance of the residual neural network. (3) A deformable multi-head attention module(DMAM) is designed in the Transformer layer, which uses deformable self-attention to extract long-term feature dependencies and enhance its global feature extraction ability. (4) A context feature fusion module(CFFM) is designed to efficiently aggregate the spatial information of the shallow network and the channel information of the deep network, and enhance the cross-layer features extracted by the network. Experimental results show that the proposed model effectively improves the recognition accuracy of flame burning state in MSWI process.

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Introduction of Flame Combustion Image

The experiments in this study used Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-13400F processor 4.60 GHz CPU, Windows 11(64-bit) operating system, pytorch2.1.0 framework and NVIDIA CUDA interface model for acceleration.

The network input image size is 224×224×3 pixels, and the selected optimization strategy is Adam algorithm. We used 16 batch sizes of the dataset to train the model for 100 epochs. No pre-trained models were used in any of the experiments, and each model was trained starting from an initial state.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

Through the quantitative comparison of the experimental results of the classification model, the advantages and disadvantages of the classification model can be judged. We mainly use accuracy (Acc), precision (Pre), recall (Rec) and F1 score as evaluation indicators to analyze the recognition effect of the network model proposed in this study on the burning state of MSWI. The mathematical expression of the evaluation index is as follows:

In the equation: TP is the number of model predictions correctly labeled as positive, FP is the number of model predictions incorrectly labeled as positive, TN is the number of model predictions correctly labeled as negative, and FN is the number of model predictions incorrectly labeled as negative.

3.3. Flame Burning Images Dataset

The data set used in this experiment is the flame burning image data set created by Pan et al in literature [

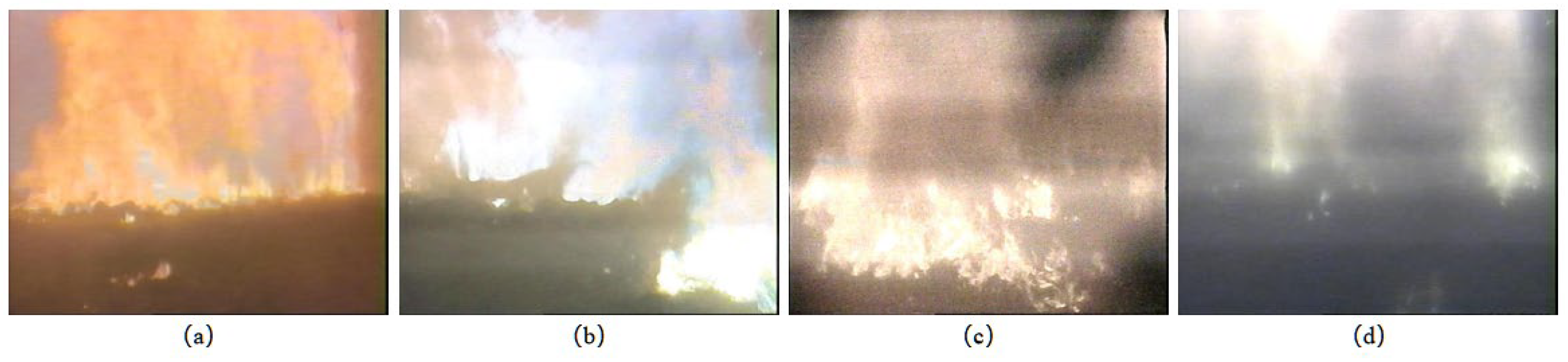

21], which is from a MSWI factory in Beijing. Inside the incinerator, the left and right sides are equipped with high temperature resistant cameras for capturing flame video. After collecting the flame video from the left and right cameras in the field, the first step was to remove the segments that did not describe the burning state clearly. Next, the remaining video clips are classified according to the burning state classification criteria shown in

Figure 1. These classified video clips were subsequently sampled using a MATLAB program at a consistent rate of 1 frame per minute, resulting in the extraction of flame image frames. Finally, the total number of typical burning state images obtained from the left and right stoves is 3289 and 2685, respectively. Due to the symmetrical distribution of the left and right grate images, in order to improve the generalization ability of the model in this paper, the left and right grate images are merged into a data set for experiments, and the ratio of training set, validation set and test set is 0.7:0.15:0.15. The amount of data corresponding to each typical burning state is shown in

Table 1.

3.4. Model Experimental Results

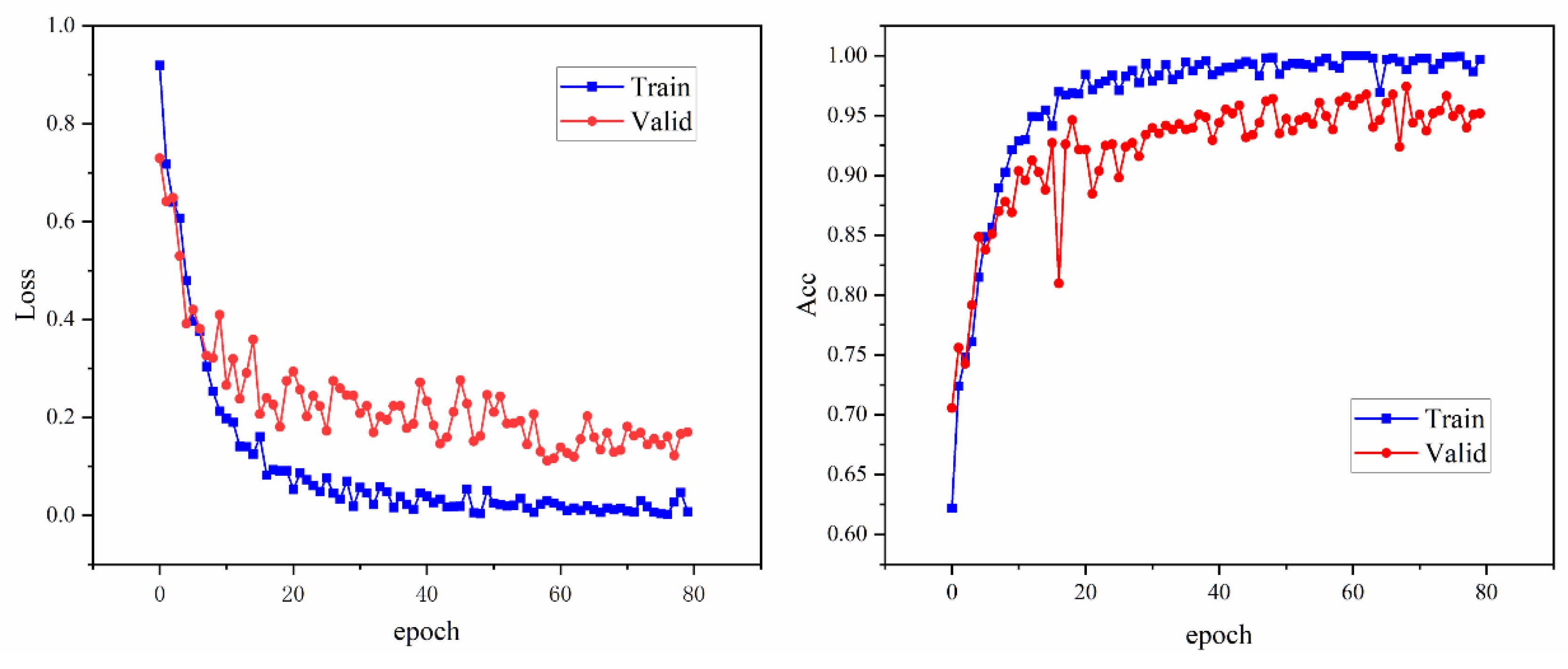

Figure 5 represents the loss and accuracy during model training. The left figure shows the loss plotted against epochs for the training and validation sets. It can be observed that both the training loss and the validation loss gradually decrease with the increase of epochs, which indicates that the performance of the model on both the training and validation sets is constantly improving. In particular, the loss decreases relatively fast in the first 20 epochs, after which the loss gradually levels off and the validation loss fluctuates up and down around the training loss.

The right figure shows the training and validation set accuracy plotted against epochs. It can be seen from the figure that both the training accuracy and the validation accuracy gradually increase with the increase of epochs and become stable after about 20 epochs. The training accuracy is always higher than the validation accuracy, which reflects that the model performs better on the training set than on the validation set, but the gap between the two is not large, indicating that the model does not significantly overfit.

The two figures show that the loss of the model gradually decreases and the accuracy gradually improves during the training process, and it tends to be stable after a certain number of epochs, which achieves a good training effect, indicating that the model has effectively learned the features of the flame burning image.

3.4. Results of Ablation Experiments

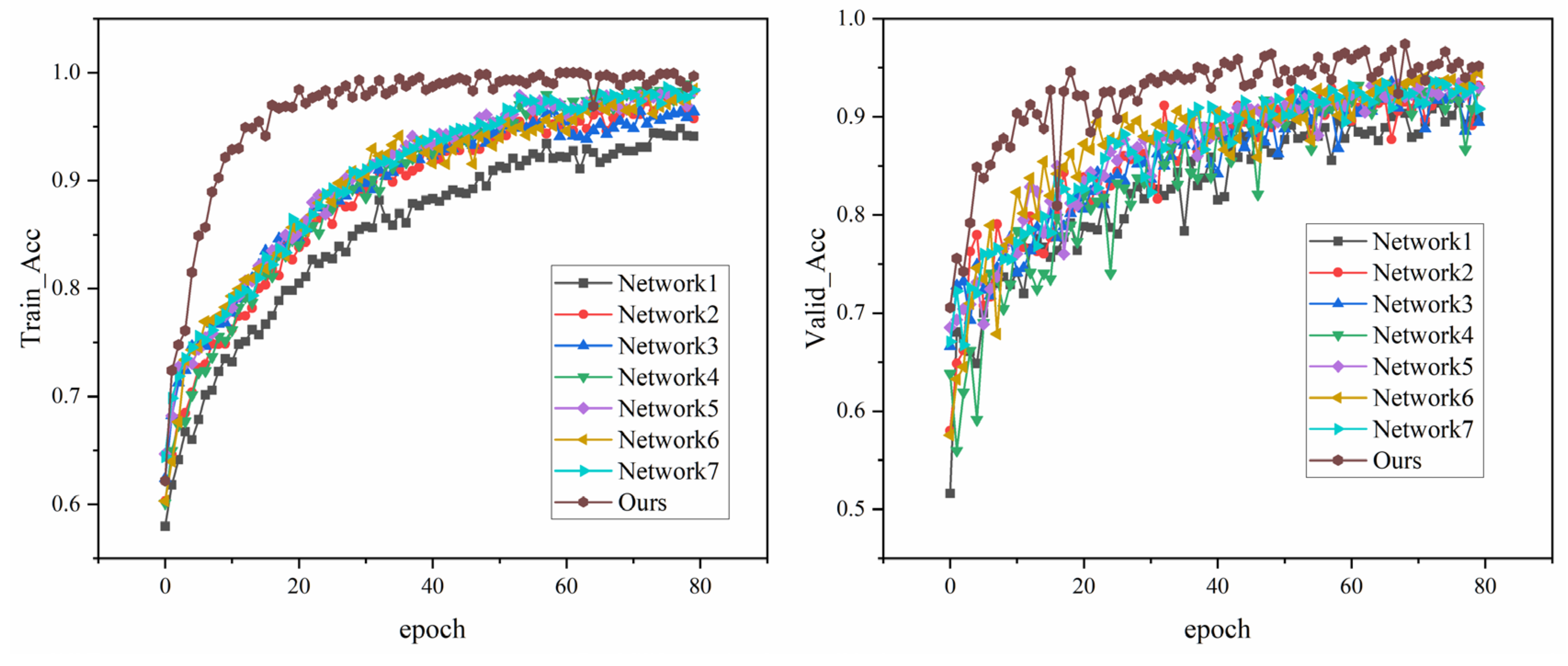

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the modules, each module is tested through different network models, as shown in

Table 2, and eight experiments are conducted in turn based on the residual network in this experiment.

Figure 6 shows the ablation experimental results of different network configurations in the flame burning state recognition task of MSWI process, and the effectiveness of the proposed method is verified by comparing the training and validation accuracy. As can be seen from the left figure, the proposed method shows the characteristics of rapid convergence at the early stage of training, and the training accuracy is significantly higher than other configurations. It is also seen from the right figure that the accuracy of the proposed model in the validation set is always ahead and significantly higher than that of other configurations, which proves the key role of the three feature enhancement strategies proposed in this paper.

Table 2 provides detailed experimental results for each model. Compared with Network1, the performance parameters of Network2 are improved after adding EMA module, and the accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score of Network2 are increased by 0.93%,1.2%,0.55% and 0.88% respectively, which proves the effectiveness of EMA module. After adding DMAT module, the accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score of Network3 are increased by 0.4%,1.14%,0.2 % and 0.67%, respectively, which proves that DMAT module can make the network have better extracted features. After adding the CFFM module to Network4, the accuracy rate is increased by 0.27%, the precision rate is increased by 0.57%, the recall rate is increased by 0.05%, and the F1 score is increased by 0.31%. It is verified that the CFFM module can enhance the feature fusion of different stages and enhance the feature extraction ability of the model.

The evaluation indexes of Network5, 6 and 7 with two modules are higher than those of Network2,3 and 4 with only one module. The model with three modules has the best performance, and compared with the initial Networkl model, the accuracy of pneumonia classification is increased from 91.92% to 96.16%, the precision is increased from 91.45% to 96.15%, the recall is increased from 92.5% to 96.07%, and the F1 score is increased from 91.97% to 96.11%. It can be concluded that the proposed model has the best performance and the best performance in MSWI combustion state recognition.

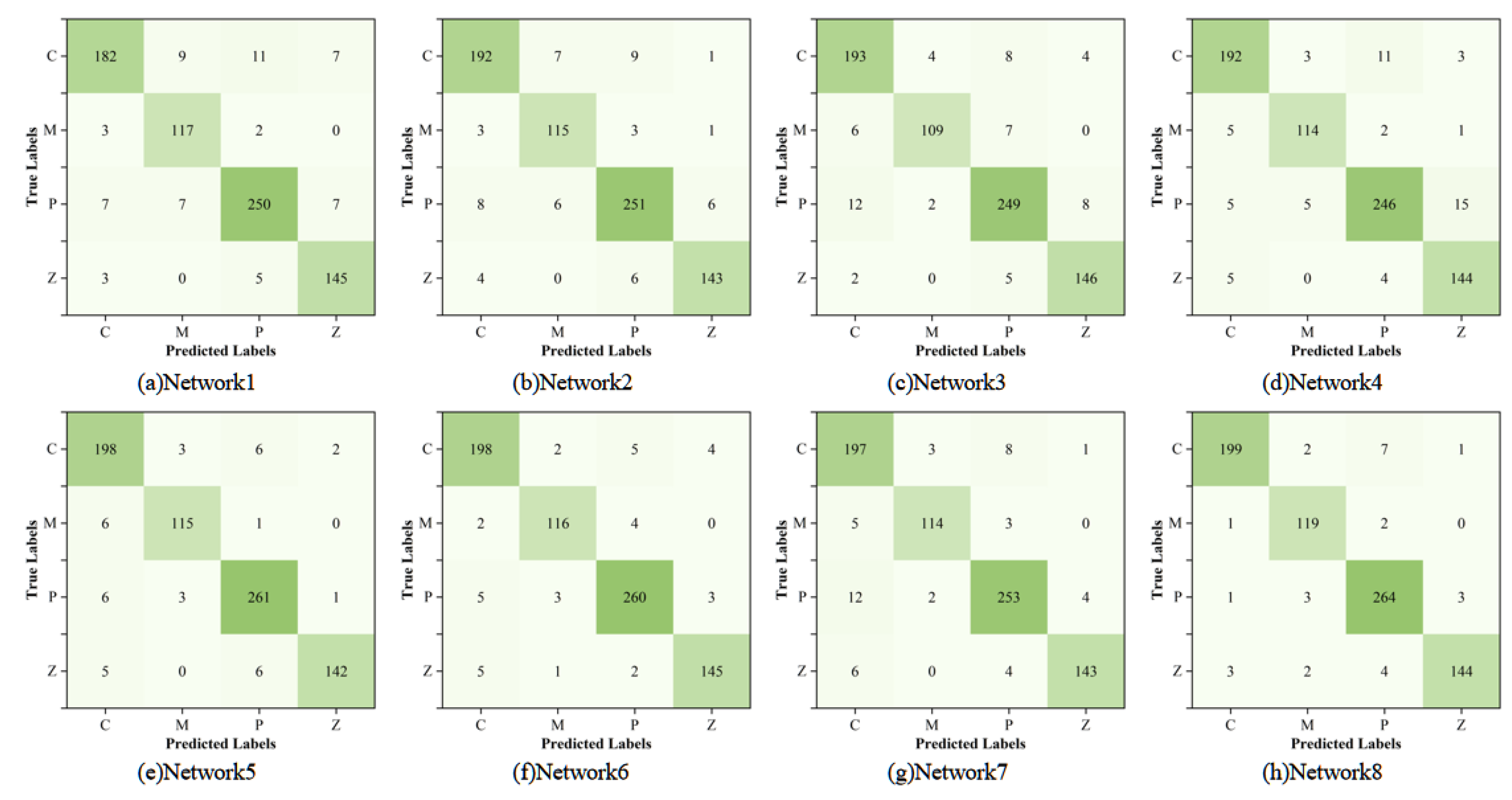

In addition, in order to investigate the difference between the labels predicted by different models for the classification of four types of samples and the real situation, this paper uses a confusion matrix to visualize the test results of ablation experiments, as shown in

Figure 7. Through the comparison of confusion matrix, it can be seen that the proposed model has better classification effect and can realize the accurate identification of MSWI burning state.

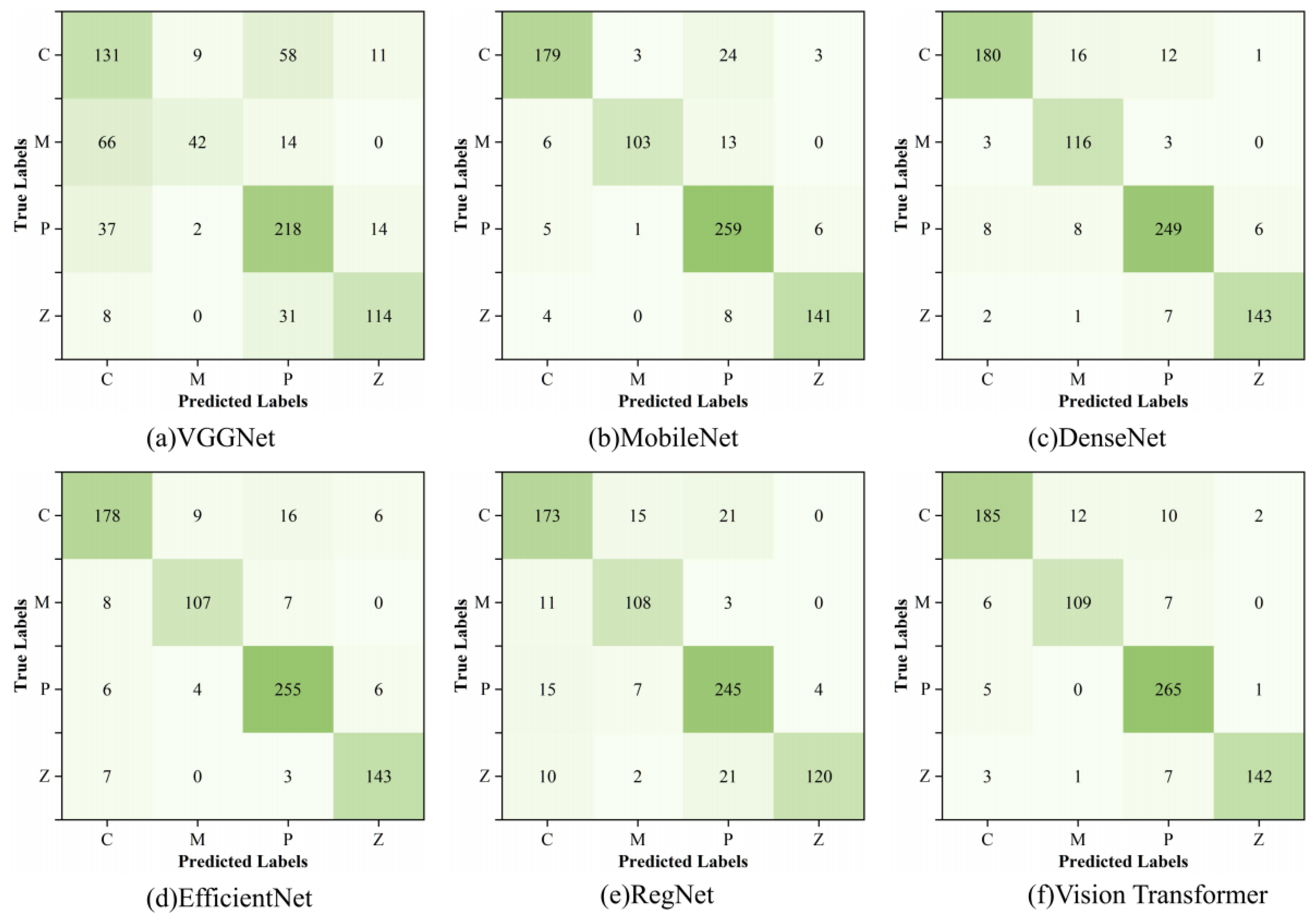

3.3. Results of Comparative Experiment

In order to verify the recognition ability of the proposed model for MSWI burning state, it is compared with the classical deep learning method in

Table 3 on the same data set. The experimental results are as follows:

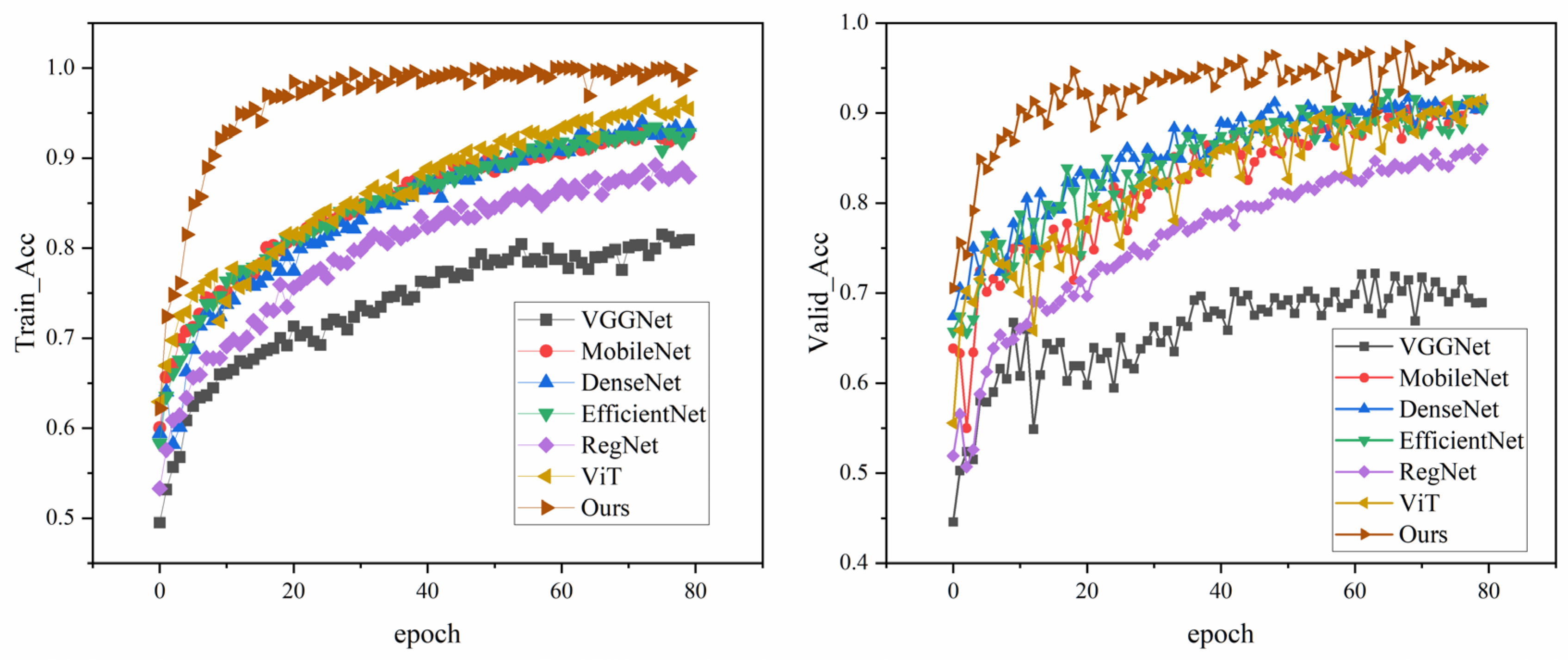

Figure 8 shows the performance of different models in the training process, the left figure shows the accuracy of each model on the training set, and the right figure shows the accuracy on the validation set. In conclusion, the proposed model not only performs well on the training set, but also has strong generalization ability on the validation set. The specific experimental results are shown in

Table 3.

The experimental results show that the accuracy rate, precision rate, recall rate and F1 score of the proposed model are 96.16%, 96.15%, 96.07% and 96.11%, which are better than other networks and have better classification performance. In this study, the confusion matrix is used to visualize the results of the test set of each model, and the results are shown in

Figure 8. From the comparison of the confusion matrix, it can be seen that the recognition ability of the model proposed in this paper for MSWI states is more balanced and more effective than other classification networks.