1. Interrogating Liminality and Precarity: Euro-Orientalism, Racial Triangulation, and the Post-Socialist Subject in International Higher Education

The globalization of academia has elevated efficiency and productivity as cardinal virtues, reshaping higher education through the prism of the Internationalization of Higher Education (IHE), a field rife with contested definitions and potentially transformative implications (Walker, 2009, p. 505; Brandenburg & de Wit, 2011; Knight, 2008). The IHE, as both a scholarly construct and a global phenomenon, encapsulates the dialectics of globalization, where capital flows, sociocultural exchanges, and geopolitical forces converge to redefine institutional missions. Yet, neoliberal globalization has entrenched systemic inequities, rendering higher education complicit in structural violence. Critical Internationalization Studies (CIS) emerges as a counter-hegemonic framework, interrogating the power asymmetries and exploitative logics underpinning globalized academia. This study employs a CIS-informed lens to examine the interplay of domination and resistance within the internationalized university.

Focusing on the University of Iceland’s International Studies in Education Program (ISEP), in this study, ISEP is posited as a potential exemplar of “internationalization otherwise”, a decolonial praxis that challenges the neoliberal commodification of the IHE (Stein et al., 2016, p. 9). By offering an English-medium curriculum to a global cohort, the ISEP embodies an anti-oppressive ethos, contesting Western epistemological dominance and advocating for epistemic justice. CIS critiques the global knowledge economy, unmasking how internationalization policies perpetuate systemic racism, linguistic hierarchies, and xenophobic exclusion (Tikly, 2004; Lee & Rice, 2007; Yao & Mwangi, 2022). Through feminist, anti-capitalist, and anti-racist frameworks, CIS dismantles the veneer of benign globalism, exposing the coloniality of power embedded in the IHE (Stein & McCartney, 2021). This research aligns with CIS’s imperative to reimagine internationalization, confronting its colonial residues and advocating for the equitable redistribution of epistemic and material resources (Stein et al., 2016, pp. 14–15).

This study employs Said’s Orientalism (1978, 1985) and its intra-European counterpart, Euro-Orientalism (Adamovsky, 2005; Buchowski, 2006; Parvulescu, 2015; Appendix B), to interrogate the subjectivities of non-Western European students from post-socialist states at the University of Iceland. Framed by concepts such as exotic insiders (Abu-Lughod, 1991), global white supremacy (Jesús & Pierre, 2020), racial triangulation (Kim, 1999; Parvulescu, 2015), and precarity (Lazar & Sanchez, 2019; Parvulescu, 2015), the analysis reveals how these students oscillate between inclusion and exclusion, occupying a liminal space where whiteness mitigates precarity without conferring privilege (Parvulescu, 2015, p. 39).

Precarity, understood as a condition of marginality, exploitation, and systemic exclusion (Munck, 2013; Casas-Cortès, 2017), is embedded within a racialized hierarchy perpetuated by global white supremacy—a foundational logic of modernity that sustains liberalism, democracy, and rationality (Jesús & Pierre, 2020, p. 67). By synthesizing Critical Internationalization Studies (CIS), postcolonial theory, and anthropological perspectives, this study provides an interdisciplinary framework to examine the lived experiences of ISEP students, contributing to critical dialogues on power asymmetries, inequality, and the racialized contours of international education.

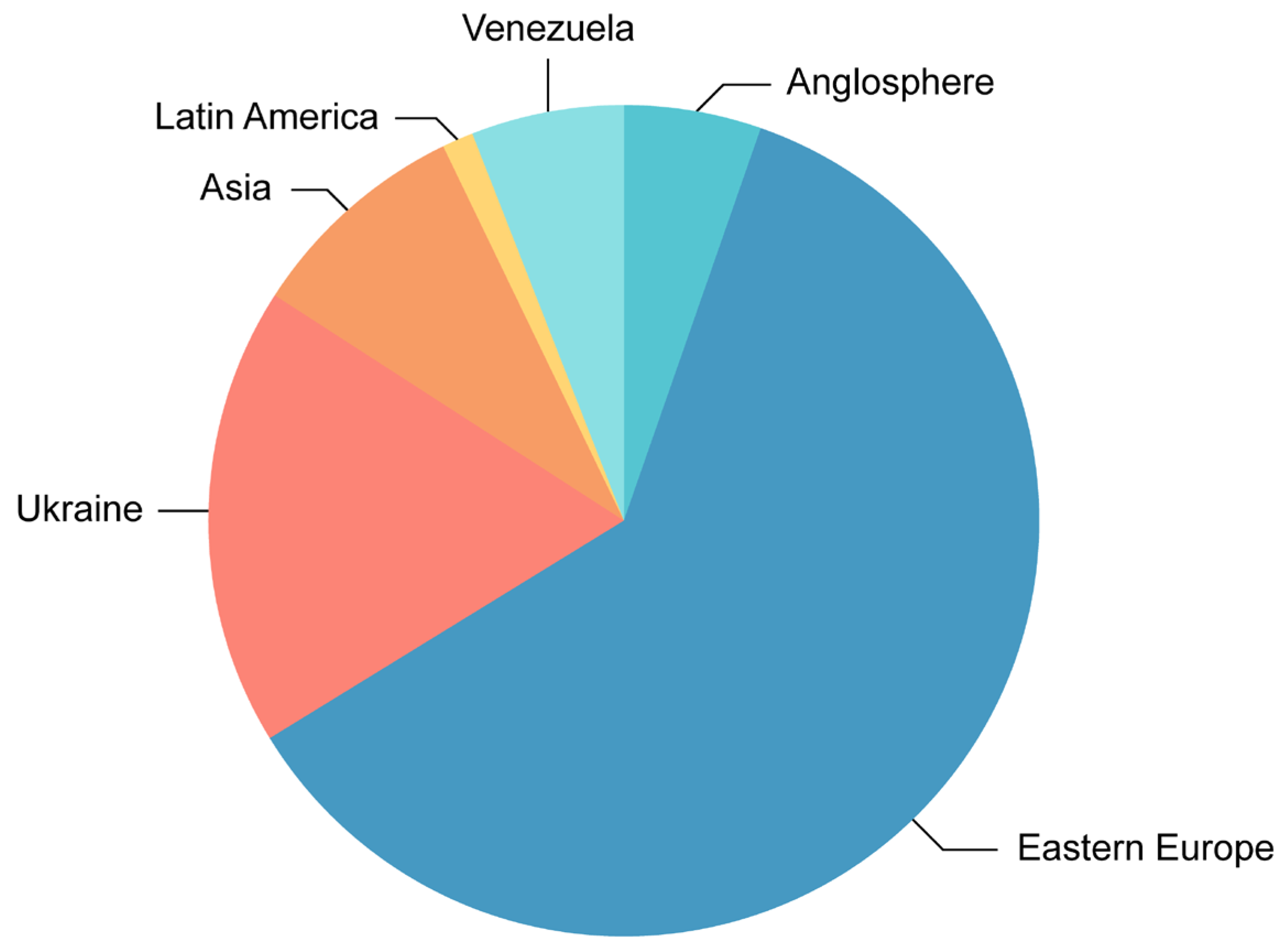

Focusing on Eastern European students within the International Studies in Education Program (ISEP) at the University of Iceland, this research highlights a demographic that constitutes the largest immigrant group in Iceland. In 2022, Eastern Europeans numbered 9734, including Poles, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Ukrainians (Statistics Iceland, 2024). Eastern Europeans constitute the predominant cohort of international students at the University of Iceland, with Asian and Anglosphere students forming significant subsequent contingents. (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Their demographic significance underscores their relevance as a focal point for understanding the intersection of migration, education, and racialized hierarchies in a globalized context.

The term “Eastern Europe” is deployed critically, interrogating its construction through Euro-Orientalist discourses and Western othering. Borders, as ideological apparatuses, perpetuate hierarchies of sovereignty and cultural–political belonging (Balibar & Spivak, 2016; Spivak & Harasym, 1990). Eastern Europeans often inhabit a relational identity, disavowing “Easternness” while striving for Western validation (Kalmar, 2022). Eschewing categorical fetishism (Crawley & Skleparis, 2018), this study examines the subjectivities of non-Western Europeans (NWEs) from post-socialist states, probing how these positions are negotiated, contested, and resisted within international higher education. It seeks to chart pathways for critical relationalities and postcolonial solidarities, challenging essentialist binaries and unveiling the power dynamics that shape their lived realities.

Focusing on NWE students from post-socialist contexts, this research highlights their peripheral positioning within Europe’s sociopolitical imaginary, which informs their distinct relationality to whiteness compared to Western/Nordic or non-white peers. While whiteness remains an invisible privilege for its beneficiaries (Loftsdóttir, 2021, p. 2), NWE students occupy a liminal space, shaped by their post-socialist heritage. These students originate from former Eastern Bloc and non-aligned nations—such as Poland, Hungary, the Baltic states, and Balkans among others—that transitioned from state socialism to market capitalism post 1989, with many acceding to the EU during its 2004 enlargement (Welsh, 1994).

The post-socialist condition is analyzed through the lens of Euro-Orientalism and Buchowski’s (2006) binary of post-socialist versus capitalist mentalities. While vestiges of the Homo Sovieticus stigma endure, Icelandic perceptions have evolved, valorizing NWE students as “hardworking” and “diligent”. Yet, such ostensibly positive tropes reflect racial triangulation (Kim, 1999; Parvulescu, 2015), situating them as model minorities within a stratified hierarchy of whiteness. This framework elucidates their experiences of “passing as Icelanders” or being perceived as “white Europeans” in Western contexts, as further unpacked in the findings.

This study contends, following Parvulescu (2015), that non-Western European (NWE) students occupy a subject position defined not by whiteness or privilege, but by their placement within an ethnic hierarchy of precarity, shaped by global white supremacy (Jesús & Pierre, 2020). Integrating Orientalism, Euro-Orientalism, racial triangulation, and precarity, it addresses its central question: How do NWE students experience higher education at the University of Iceland? The study diagnoses power (Abu-Lughod, 1989) within NWE and post-socialist subjectivities, exploring how these positions are negotiated, contested, and resisted, while envisioning epistemic equality for marginalized voices. Positionality informs the research design, outcomes, and interpretations (Darwin Holmes, 2020; Rowe, 2014), with auto-ethnographic insights enriching the findings.

Structured to critique Eurocentrism (Tikly, 2004; Yao & Mwangi, 2022), racism, and linguistic discrimination (Brown & Jones, 2013; Lee & Rice, 2007), this study disrupts harmful practices (Stein & McCartney, 2021), complacency in harm and advocates for postcolonial solidarities. It begins with a literature review on Critical Internationalization Studies (CIS) and postcolonial theory, followed by methodology, findings, and a conclusion proposing pathways toward relationalities and equity in higher education.

2. Decentering the Global Imaginary: Critical Internationalization Studies, the Politics of Knowledge and Resistance in Higher Education

Critical Internationalization Studies (CIS), grounded in postcolonial critique, challenges mainstream narratives of globalization as neutral or inevitable (Altbach, 2004; Rizvi, 2007). It critiques the commodification of internationalization, where students are framed as “untapped resources” within neoliberal frameworks and interrogates the enduring modern/colonial global imaginary (Stein et al., 2016). CIS reimagines internationalization as a site of resistance, exposing contradictions in Western epistemologies and advocating for anti-oppressive practices (Beck, 2021). Central to this study is internationalization otherwise, informed by Said’s Orientalism (1978), Herder’s Romantic Nationalism (Nisbet, 1999), and Euro-Orientalism (Buchowski, 2006; Kuldkepp, 2023; Parvulescu, 2015), which critiques colonial power dynamics and envisions equitable, transformative higher education.

CIS identifies four trends in the Internationalization of Higher Education (IHE): (1) internationalization for a global knowledge economy, reinforcing neoliberal competition and commodification (Stein & McCartney, 2021); (2) internationalization for the global public good, promoting minor reforms under liberal ideals but risking paternalism and colonial logic (Jefferess, 2012; Ziai, 2019); (3) internationalization for global equity, advocating systemic change; and (4) internationalization otherwise, dismantling oppressive structures entirely. The global knowledge economy perpetuates competition and corporatization (Ball, 2012; McCartney & Metcalfe, 2018), while the global public good masks colonial logics under benevolent rhetoric (Tuck & Yang, 2012). Global equity and internationalization otherwise challenge these frameworks, centering marginalized voices and prioritizing immediate harm reduction over incremental reform (Stein, 2021; Mwangi et al., 2018). This study situates itself within CIS, critiquing commodification and envisioning transformative possibilities for the IHE.

3. Unveiling Hierarchies: Orientalism, Euro-Orientalism, and the Liminality of Non-Western European Subjectivities in Globalized Higher Education

This research centers on Orientalism as a Western dispositif (Said, 1985), restructuring knowledge to dominate the “Orient”, extended here to non-Western European (NWE) post-socialist subjectivities. This deliberate ignorance legitimizes political projects, privileging some while marginalizing others (Buchowski,

Table 1). Said critiques even counter-knowledges such as Marxism, rooted in historicist epistemologies that sustain colonial binaries. Adopting Amel’s (2020) stance, the study reevaluates oppositional consciousness within CIS to interrogate global white supremacy, precarity, and hegemony, seeking pathways to transcend modernity’s enduring antagonisms.

German Romantic Nationalism, as theorized by Herder (Wilson, 1973), posits nations as unique entities shaped by environment and history, weaponizing language and culture to exclude the “Other” (Björnsdóttir & Kristmundsdóttir, 1995; Goldin-Perschbacher, 2014). In Iceland, language becomes a contested site, reflecting tensions between national identity and neoliberal higher education. Euro-Orientalism extends this logic, otherizing Eastern Europe through a Western gaze, situating it between Western and postcolonial contexts (Tlostanova, 2012). NWE students, as exotic insiders, navigate racial triangulation, occupying liminal spaces within global capitalist societies (Chen & Hosam, 2022). This framework reveals how internationalization perpetuates racialized hierarchies while enabling access for a global elite (Johnstone & Lee, 2014). Subsequent sections explore exotic insiders, racial triangulation, precarity, and global white supremacy as they intersect with the article’s theoretical pillars.

4. Exotic Insiders and Racial Triangulation: Navigating Liminality and Hierarchies in Globalized Higher Education

The term exotic insiders describes subjectivities that deviate from idealized societal constructs, occupying liminal spaces within and at the margins of communities (Abu-Lughod, 1991). Applied to Romani peoples (García-Martín, 2018), it aligns with non-Western European (NWE) students in higher education, who navigate tensions between inclusion and exclusion. Like the Roma, whose displacement is depoliticized through legal fetishization (Çağlar, 2016; Sardelić, 2021), NWE students face administrative barriers—unrecognized qualifications, restricted employment rights—reflecting neoliberal exclusions. Valorized as model minorities yet marginalized as perpetual foreigners, their duality mirrors the Roma’s treatment as “undesirables” (McGarry, 2014; Nicolae, 2007). This paradox, rooted in racial triangulation, underscores their liminality within global white supremacy. Critical Internationalization Studies (CIS) challenges these structures, advocating for systemic critique and emancipatory alternatives. By framing NWE subjectivities as exotic insiders, this research interrogates the operationalization of colonial, nationalist, and Euro-Orientalist dispositifs, calling for transformative internationalization practices.

The study employs the terms “racial” and “racialized” over “ethnic” to capture the nuanced hierarchies shaping NWE subjectivities. While some Eastern Europeans self-identify as white, others, like the Roma or Balkan peoples, are racialized as non-white due to darker complexions, revealing differential treatment under global white supremacy. Racial triangulation (Kim, 1999) elucidates these relational hierarchies beyond binary frameworks. Originally applied to Asian-Americans, it describes how groups are valorized relative to others (e.g., over Black communities) while facing civic ostracism from dominant white societies (Shih, 2008). Extended to transnational contexts, it reveals how groups such as South Koreans navigate vertical (economic/color-class) and horizontal (political recognition) axes within global hierarchies (Kim, 2022). Parvulescu (2015) adapts this framework to postcolonial and post-socialist contexts, emphasizing how Eastern Europeans occupy liminal racialized positions, where whiteness signifies reduced precarity rather than privilege. This research leverages racial triangulation to explore NWE students’ subjectivities, revealing their valorization as model minorities and ostracization as perpetual foreigners, underscoring the need for intersectional analyses of race, class, and precarity in European contexts.

5. Precarity, Racial Triangulation, and Global White Supremacy: Interrogating Hierarchies in Neoliberal Modernity

This section explores the intersection of racial triangulation (Kim, 2022; Parvulescu, 2015), precarity, and global white supremacy. Precarity, initially linked to poverty and insecure labor (Barbier & Théret, 2001), now encompasses marginality, social exclusion, and immaterial labor (Casas-Cortès, 2017). While its global applicability was debated (Lazar & Sanchez, 2019), precarity has normalized under neoliberalism, marked by deregulation, privatization, and migrant illegality (Ritzer & Dean, 2021). Yet, it operates within a racialized hierarchy, disproportionately impacting marginalized groups (Schweyher, 2023; Mbembe; Butler), sustained by global white supremacy—a dispositif structuring modernity through liberalism, democracy, and progress (Jesús & Pierre, 2020).

Acknowledging my positionality within this hierarchy, I engage counter-knowledges to critique modernity’s antagonisms (Said, 1985; Amel, 2020), while recognizing the neoliberal university’s complicity in perpetuating white supremacy (Stein et al., 2019; Shultz, 2015). This research interrogates these dynamics, seeking to disrupt harmful patterns and envision transformative possibilities.

6. Methodology

In this study, a qualitative, social constructivist approach is used to examine the subjective experiences of non-Western European (NWE) students from post-socialist countries in the International Studies in Education Program (ISEP) at the University of Iceland. Integrating critical qualitative methods, reflexive narrative accounts, and semi-structured interviews, it explores themes of whiteness, precarity, and racialized hierarchies.

Research Design: Adopting a constructivist–poststructuralist epistemological stance, knowledge is viewed in this study as socially constructed and shaped by power dynamics (Creswell, 2007). The study centers on NWE students, whose marginality reflects broader geopolitical and racialized hierarchies (Loftsdóttir et al., 2023). Reflexive narrative accounts, informed by the researcher’s positionality as an ISEP graduate, supplement the dataset, offering insights into systemic barriers and potential solidarities.

Interview Design: Semi-structured interviews allowed the participants to construct their narratives (Braun & Clarke, 2013). The questions were organized into three parts: basic information, subjective experiences, and social boundaries/hierarchies, facilitating an exploration of students’ perceptions of their subject positions within Icelandic academia and society.

Sampling and Informants: Six NWE students from post-socialist countries were interviewed, selected through convenience and snowball sampling. Despite COVID-19 restrictions limiting sample size, the diversity of participants—spanning gender, linguistic, and professional backgrounds—provided rich, nuanced data.

Confidentiality/Anonymity: Pseudonyms ensured participant anonymity, with data securely stored offline. Informed consent was obtained, and the participants were assured of their right to withdraw at any time.

Data Collection: Conducted between May 2021 and January 2022, the interviews included group and individual sessions, lasting 50–100 min. Conducted in English, they were recorded and transcribed, with deviations from the script to allow for spontaneous narrative development. Supplementary data from the University of Iceland’s course catalog, equality plans, and event programs (2021–2023) corroborated the informants’ accounts.

Analysis: A content analysis of 126 transcribed pages, using LiquidText and Atlas.ti software, explored non-verbal cues and affective dimensions (Ayata et al., 2019; Gould, 2009). A deductive approach framed the study within critical theories of whiteness and racialization, while an inductive approach uncovered emergent discourses of otherness, informed by Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) conceptualization of discourse as a fluid system of meaning.

Shortcomings: Conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, the research faced limitations, including reduced socialization, heightened mental health challenges, and a small dataset due to restricted participation. Online interviews introduced technical and rapport-building difficulties, mitigated by in-depth analysis and reflexive narrative accounts.

Ethical Concerns: The researcher’s positionality—shaped by international experience and activism—required ongoing reflexivity to address potential biases. Confidentiality was ensured through pseudonyms, secure data storage, and informed consent, balancing the researcher’s role as a knowledge curator with commitments to the community.

This section outlined the qualitative methodology, emphasizing its strengths in capturing nuanced insights into NWE students’ experiences. The following section presents the findings, using thematic analysis to explore how sociocultural and political contexts shape these narratives.

7. Presentation of Research Findings

This section examines the subjective experiences of non-Western European (NWE) students at the University of Iceland, focusing on their racialized and class-based positionality within a neoliberal higher education (HE) framework. Often marginalized as “Int Stdnts” (international students), they are framed as transient rather than integral members of Icelandic society. To counter this, the term “immigrant working students” (IWSs) is used, reflecting their dual roles as students and economic contributors.

The analysis is structured around two themes: (1) subjectivity and positionality, exploring race, class, and precarity, and (2) Euro-Orientalism, examining language and racialized hierarchies. The students expressed frustration with institutional support, citing a lack of career-oriented courses in English and a disconnect between their needs and university offerings. Courses such as “Viking and Medieval Norse Studies” cater to heritage tourism rather than practical career advancement, reinforcing exclusionary practices.

The findings reveal how NWE students navigate a system that valorizes certain cultural registers (e.g., Icelandic heritage) while marginalizing others, reducing them to consumers and undermining their sense of belonging. Reflexive narrative accounts further illustrate these dynamics, emphasizing the need for equitable internationalization practices. The research underscores the intersection of global white supremacy, neoliberal HE policies, and the marginalization of NWE students, calling for a reimagining of internationalization that prioritizes inclusivity, anti-racism, and postcolonial solidarity.

Parallels are drawn with França et al.’s (2018, 2023) study of international students in Lisbon, where city-branding strategies created unmet expectations around housing and the cost of living. In Iceland, NWE students face similar precarity, with some relying on student loans or multiple jobs to finance their studies. Tax obligations and housing instability exacerbate their challenges, as the Icelandic real estate market prioritizes tourism over affordable student housing. While local Icelanders may rent their homes to tourists for extra income, marginalized communities and students lack such options, highlighting systemic inequities. This influx has created gentrification of the city center and rising costs for the local population, driven by the large numbers of individuals identified by Malet Calvo (2018, 2021) as a class of transnational urban consumers. It has also caused the homogenization of the city and the loss of sociocultural diversity as a result of neoliberal urban politics pushing away diverse populations. Ironically, the goal of creating a diverse sociocultural setting via the global knowledge economy has backfired for Lisbon. It has been colonized by this same transnational consumer class and thereby extinguished the socially and culturally rich setting that was once a commodity in the city’s branding.

This example underscores the interweaving of Internationalization of Higher Education (IHE) globalization with (neo)colonial and neoliberal imperatives. While Iceland’s public universities, such as the University of Iceland (UI), do not impose substantial tuition fees—unlike private institutions such as Reykjavík University—the prominence of medieval and Viking-related studies signals an effort to leverage nation-branding through the commodification of Icelandic heritage. This aligns with Herder’s Romantic Nationalism, which underscores cultural distinctiveness and has significantly influenced Icelandic nationalism and the construction of racialized identities (Wilson, 1973, pp. 821–822). Historically, Icelanders have asserted that their landscape shaped their national character, leaving an indelible mark on literature and language (Goldin-Perschbacher, 2014, p. 54). Herder’s nationalist ethos permeates the UI’s course catalog, interwoven with contemporary myths of a classless society (Broddason & Webb, 1975), a haven of diversity and gender equality (Þrastardóttir & Kjaran, 2023), and a queer utopia (Vilhjálmsson, 2022). Heritage tourism, a strategic initiative of the European Commission (Richards, 1996, p. 261), encompasses Viking-heritage tourism (Halewood & Hannam, 2001), which commodifies an idealized past, appealing to embodied masculinities (Bureychak, 2013; Knox & Hannam, 2007). This inward gaze positions the West as the pinnacle of modernity, reinforcing nation-branding.

The Icelandic language and its use remain a matter of contention in popular discourse. Sometimes it appears as the ultimate demise and extinction of the language due to foreign influences and the threat of non-Icelandic-speaking immigrants, or, in the comparison to HE and the neoliberal university, the perceived ineptitude of immigrant students to participate due to meager Icelandic skills.

The Icelandic language as a hindrance and gatekeeping mechanism is a recurring theme of research (Innes et al., 2024; Wojtyńska et al., 2022, 2022a), and one which also appeared in one of the interviews. Kristín took courses where the language of instruction was Icelandic, and they were allowed to complete the assignments in English. However, they were encouraged to take the course as a distance course instead of on-site since they would be “unable” to interact with their peers in the Icelandic language. The course in Methodology was a credit requirement for the student before graduation. Language as a hindrance, drawing the lines between career paths, can constitute a form of governing apparatus that is operationalized to legitimize existing differentiation processes and power hierarchies (Abrar-ul-Hassan, 2021). This is in line with the notion of Orientalism as a Western dispositif (Said, 1978). Language also demarcates subject position. When asked who is at the top and who is at the bottom in the social hierarchy, whether within HE or broadly within Icelandic society, one participant noted the following:

“Well, I think at the top [are] white people like me, you know. We are kind of privileged immigrants here … some people sometimes are mean in some circumstances, mostly because of language issues”. (Guðrún)

The subject was asked, based on her lived experiences within HE and the marketplace in Iceland, whether there is a perception of social hierarchy among groups, and if so, how would she explain this hierarchy. There, the subject is not ranking groups but manifesting how racial hierarchies are understood from a subjective perspective. “White people like me” entails self-identification. It also implies presumed gains associated with whiteness and Europeanness, as the following remarks point out:

“I think white Europeans … are accepted and are in a way welcomed … some Icelanders think that white Europeans or even Eastern Europeans, that we are, you know, are very duglegur [English translation is efficient or capable], we are very like... hardworking, good people. I hear this often... Okay. ...while, for example, I think that people from Asia or black people, I think it’s much more difficult for them here... like everywhere... Okay...because of those systemic problems and other issues”. (Vala)

There is a lot to unpack in this remark from Vala. Her response suggests a perceived racial hierarchy. While Guðrún points to whiteness as a dimension of racial differentiation, Vala also notes the category of citizenship as in “white Europeans”, “accepted in a way welcomed”. This indicates a sociocultural and political imaginary within broader transnational processes where being part of the European territory is perceived as an advantage. This is in line with the binary of Insider/Foreigner or “citizenship line” in the concept of racial triangulation. Conversely, the assertion of “white Europeans” as “accepted in a way welcomed” has to do with Superior/Inferior or “color line” in racial triangulation (Kim, 2022). The subject’s precise words are “accepted and are in a way welcomed”. Here, “in a way”, denotes that the link between “white Europeans” and being “welcomed” is not direct. However, they are nonetheless welcome. In the passage that follows, this uncertainty is exemplified by differentiating white Europeans and Eastern Europeans: “even Eastern Europeans” indicates that the position of our NWE informants is not directly associated with whiteness and entails a foreignizing or Westerning (Said, 1985) of these subjectivities. Comparatively, this is similar to a “partial presence” (Espiritu, 2003, p. 47) where civic ostracism (Kim, 2022, pp. 471–472) may occur within a precarious subject position experience (Gutmann, 1994).

Racial triangulation, in the case of NWEs, has to do with highly complex nodes of racialization (Parvulescu, 2015, p. 36), between—in the case of this research—the perceived subject position of NWEs in relation to blacks and Asians, as Vala puts it. This implies racial ordering (Kim, 1999, p. 10) in a racial hierarchy. The subject suggests this “privileged” position of NWEs in relation to these groups applies in Iceland (“here”), and in the rest of the world (“everywhere”). This implies another core concept in this research: that of global white supremacy as the baseline (Jesús & Pierre, 2020, p. 67). However, before I consider the implication of this, there is yet another clear reference to the concept of racial triangulation. It has to do with notions of valorization and model minority-signaling when the informant argues that “some Icelanders think that white Europeans or even Eastern Europeans, that we are, you know, are very duglegur, we are very like... hardworking, good people”. The word duglegur has many meanings in the Icelandic language and is most commonly used as a synonym for “hardworking”. The subject’s suggestion that Eastern Europeans are seen by some Icelanders as hardworking and good people is tied to the idea of a model minority where the contribution of this demographic is valorized (Kim, 2022; Parvulescu, 2015). The hesitation in correlating Eastern Europeans with whiteness may indicate a strategy to operationalize a trait in a disadvantageous subject position:

“…because my boyfriend, he is Icelandic, so I am also kind of a part of his Icelandic family, and I am... I feel really welcome there, so I was saying that ‘Oh, my Icelandic family, they are really nice, and even his extended family is accepting me. I am invited to all the parties, and so on.’ But [referring to my friend’s experience for comparison] ... since she is from the Philippines and has an Icelandic spouse, she was actually saying something totally different, and she said that she, you know, is being judged and criticized, and she faces racism. And she said... like, ‘Oh, you are being accepted, because you look exactly like them,’ you know. I am a white European”. (Guðrún)

Another study approaches a comparable assertion regarding Brazilians of Icelandic descent (Eyþórsdóttir & Loftsdóttir, 2016), particularly in operationalizing a trait within a disadvantaged subject position. Yet it marginalizes local tensions and systemic disparities, partially foregrounding instead Icelandic-ness and "Viking" heritage in the Americas. This perspective, ensnared within Western epistemologies and Herder´s Romantic nationalism, reflects a selective national narrative that privileges ancestral mythos over contemporary structural realities.

The “I am a white European (man/woman)” was a recurrent sentence to describe subjects’ positionality. In line with Parvulescu’s analysis of European racial triangulation (2016), this claim to whiteness appears to be a strategized claim in relation to a racial hierarchy, as exemplified by Vala’s hesitation in the previous quote (“or even Eastern Europeans”). Moreover, Europeanness appears to be a contributing factor to their perceived privileged position compared to non-EU peers. It was in this context that subjects were asked if they have ever heard the statement “We need more people like you in this country”. As a minor auto-ethnographic and positionality account, the formulation of this question was informed by the researcher’s own subjective experiences. Having heard this from Icelanders twice, I had not problematized this before. However, in the context of racial hierarchies and racial triangulation, I found it pertinent to ask. Several confirmed subjects had heard this. However, it was unclear to them what the statement implies, and again it was associated with variations of duglegur: “very good workers, very devoted and hard-working”. They generally accepted the statement as a form of compliment:

“Probably it was just like some compliment that people from, you know, Eastern Europe, they are... are very good workers, very devoted and hard-working. So, it was in such a context”. (Helga)

Paradoxically, “We need more people like you in this country” signifies classification, differentiation, and hierarchy, echoing Said’s Orientalism (1985). It implicitly delineates the “undesirable” immigrant—dependent, unwilling, criminal (Aas, 2011). The valorization of NWE students as industrious reinforces their positioning as “workers”. A manager recently lauded Ukrainian resilience under artillery fire (Sveinsdóttir, 2024, February 1), underscoring NWE subjectivities as a conditioned service class, their worth adjudicated by Icelanders. This aligns with racial triangulation and model minority narratives (Harpalani, 2021; Kim, 2022; Parvulescu, 2015). The post-socialist “Homo Sovieticus” (Buchowski, 2006) thus shifts into a model-minority framework, yet remains burdened by persistent stigmas:

“When I was working in the service sector in Iceland, I [felt] discrimination, because I am some young foreign woman who is from Eastern Europe, a post-Soviet country”. (Kristín)

“One time, I remember, at work people just ask me where I am from, and I told them that I’m from Lithuania and they were saying like... of course it was kind of a joke... but they said like, ’Oh, so you are mafia’, because all those Lithuanians here, they are some, you know, mafiosos”. (Kristín)

“I think people, they just don’t know very much about (...) Poland, Lithuania, or Estonia. They know that [these] are close and kind of similar countries. So, they don’t have different associations”. (Jana)

Kristín’s frustration encapsulates NWE homogenization in Western imaginaries. Her experience illustrates Othering as a dispositif (Buchowski, 2006; Parvulescu, 2015; Said, 1978, 1985): from “some young foreign woman” to “post-Soviet subject”. This spatial Westerning (Said, 1978) echoes Euro-Orientalism (Adamovsky, 2005), akin to “Balkanization” (Todorova, 1997). The criminalization of EEs in Iceland resonates with Buchowski’s (2006) dyad of post-socialist stigmas: dishonesty, work ethic deficiency, and criminal adaptability (Sztompka, 2000).

On racialization, the subjects discussed “passing as Icelanders”, a term signifying fluid identity negotiation (Caughie, 1999). Historical precedents include “passing as Catholic” in limpieza de sangre (Lee, 2016; Defourneaux, 1979) or “passing as Aryan” in Nazi Germany (Griech-Polelle, 2014). Arendt (2023) finds in the Polish manuscript Liber generationis plebeanorum (c. 1624–1640), the denouncing of lower social classes for “passing as nobility”. In a contemporary context, passing in Iceland exemplifies shifting racial hierarchies:

“Most of the time on the street and in public services [They] address me in Icelandic. Because they assume I’m Icelandic because I (...) have you know, the colors... of the (...) [majority of] people have... the [the majority of] people that live here have. You know, it’s very common to have coloured eyes and bright coloured hair”. (Vala)

“Yeah, I think so. I used to hear some... some people saying that... that they thought that I am Icelandic, and they were surprised that I am not”. (Helga)

“But like [laughter] as soon as I open my mouth and I say what I think [laughter] that’s very far from Icelandic”. (Vala)

Passing shapes NWE student subjectivities, designating them as exotic insiders (Abu-Lughod, 1991; Buchowski, 2006). Int Stdnts are homogenized (Peng, 2022), reinforcing Self/Other binaries. This mirrors Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” logic, requiring cultural assimilation (Peng, 2022). It also aligns with development studies’ paternalism (Kabeer, 2015; Kothari, 2005), reinforcing domestic–international dichotomies. “Passing” as a survival mechanism is embedded in global white supremacy (Jesús & Pierre, 2020), dictating who remains “invisible”:

“Unfortunately, yes”. (Kristín)

“It’s easier ... for Icelanders to employ somebody who speaks Icelandic, of course, or looks Icelandic [laughter] and... and I don’t ... I don’t have this experience of not getting a job because I didn’t look Icelandic... because I do look Icelandic. But from people that I have communicated with that have ... I don’t know, darker complex... darker skin complex ... or, you know, frizzy hair or stuff like that [laughter], you know, some... some very superficial .. characteristics, they have shared with me, that it is not so easy, and sometimes they have experienced a kind of racism in the workplace”. (Vala)

“I think sometimes... ’cause I heard from people I know who are like... Asian people, for instance, that they do not feel maybe very welcoming, because, you know, they look … and... and they don’t look like European people. So, yeah, I think it has some impact”. (Guðrún)

“Mmm... yeah, I think so (...) people are [...] more welcoming to those people who look more like, you know, more like they look”. (Atlas)

Atlas and Guðrún affirm that superficial traits influence social acceptance. Helga dissents:

“No, not necessarily. I mean Iceland became so diverse, ehm... especially with so many people from Asia. And they mixed with Icelanders. And now you can’t really say. Mmm..”. (Helga)

Despite Helga’s claim, racial markers remain powerful. “Passing” governs opportunities and desirability within Iceland, reinforcing global white supremacy (Jesús & Pierre, 2020). Her remark on “mixing” implies essentialized categories, obfuscating structural racism.

Institutional barriers exacerbate this stratification. A recent UI survey (Appendix A) reveals that non-EU Int Stdnts face labor exploitation, exacerbated by restrictive work permit policies. Such measures force illegal employment, exposing students to abuse, precarious conditions, and mental health decline. State rhetoric criminalizes non-EEA students, resonating with the moral fetishization of law (Çağlar, 2016). Hawthorne (2008) notes that demand for international student migrants persists despite economic downturns. Given intersecting dimensions of race, class, and migration, exploitation thrives. Precarity theory thus reveals sanctioned conditions of vulnerability, marking certain subjects as permissible sites of exploitation.

8. Global White Supremacy, Performative Progress, and Postcolonial Solidarities

This section contextualizes two reflexive narrative accounts using the research pillars and core concepts to address the research question. NWE students are positioned as exotic insiders within a racialized hierarchy of precarity, maintained by global white supremacy (Jesús & Pierre, 2020). Whiteness, as a metaphor of power, is sustained through moral supremacy and performative acts of virtue, often framed as progress (Andreotti, 2014). Andreotti (2014) critiques soft global citizenship education, which perpetuates paternalistic and colonial assumptions, advocating instead for a critical approach that acknowledges asymmetrical power relations and complicity in harm. This shift from co-dependence to interdependence challenges the moral superiority embedded in Western narratives of progress.

The neoliberal university, entangled with colonial logics, exacerbates inequalities through gatekeeping tactics, cultural capital, and elite capture (Liu, 2020; Táíwò, 2022). Racial triangulation (Parvulescu, 2015) and white supremacy elevate some as model minorities while excluding others, reinforcing epistemic hierarchies.

Helga’s remark, “it is as if they think we have parents to support us financially throughout our lives”, reflects her resistance to being positioned as a financially dependent student. Her self-identification as an “immigrant working student” (IWS) challenges the neoliberal subject idealized in Western academia. This resistance aligns with Ingvars’ (2023) notion of poetic desirability, where marginalized subjects renegotiate their positionality within dominant frameworks.

The International Committee at the UI exemplifies potentialities for solidarity. Through grassroots initiatives, marginalized students advocated for systemic reforms, addressing issues such as financial instability, mental health, and abusive work environments. A reform proposal (Appendix A) emerged from these efforts, highlighting the possibility of meaningful change when power structures acknowledge marginalized voices. The author contributed to this report as an act of decolonial praxis, resulting in the establishment of a Student Council role to mediate between international students, trade unions, and the labor market. Whether this initiative will succumb to entrenched interested, elite student politics, and clientelism or fulfill its envisioned emancipatory purpose remains an open question. Regardless, the initiative stands as a tangible intervention warranting further scrutiny of the interplay between theory and praxis. It resonates with Deleuze and Guattari’s (1983) conceptualization in Anti-Oedipus, wherein capitalism operates as a mechanism to territorialize desire, only to reterritorialize moments of deterritorialization—social phenomena as ruptures that momentarily escape its rationale—within capitalism structures. As a potential site of such rupture, this initiative embodies the dialectic between the perpetual struggle for emancipation and liberation and systemic co-optation.

9. Confronting Global White Supremacy, Neoliberal Academia, and Clientelism Through Postcolonial Critical Internationalization

These narratives illustrate the ambivalence of power—both repressive and constructive. By confronting systemic inequities and fostering relationalities, this research envisions a future where marginalized groups are epistemic equals, challenging the performative virtues of global white supremacy and neoliberal academia.

In this research, a postcolonial critical internationalization approach was used to analyze the subjective experiences of non-Western European students from post-socialist countries at the University of Iceland (UI). Framed within Critical Internationalization Studies (CIS), the study addressed the urgency of those trapped in precarious labor and bureaucratic inertia, confronting neoliberal academic structures.

Building on CIS, particularly “internationalization otherwise”, and deploying a postcolonial lens, this approach was introduced to the Icelandic context. The study drew on Said’s Orientalism, Herder’s Romantic Nationalism, and Euro-Orientalism to position these students as exotic insiders, while racial triangulation, global white supremacy, and precarity informed the interpretation of their narratives. The core inquiry was “How do NWE students experience higher education at the University of Iceland?”

The findings reveal that Western dispositifs of Othering persist, constructing precarious subject positions within global Western bourgeoisie capitalist logics. Euro-Orientalism (Adamovsky, 2005; Buchowski, 2006; Parvulescu, 2015) operates as a structuring mechanism, with racialized bodies legitimizing hierarchical governance. This hierarchy, sustained through language, is embedded in a global white supremacy framework (Jesús & Pierre, 2020). White supremacy was analyzed as a dispositif, a power mechanism shaping modernity, enforcing epistemic and economic domination (Stein et al., 2019; Shultz, 2015). Higher education thus functions as a moral and ideological apparatus reinforcing these hegemonies.

By foregrounding the IHE through this critical lens, this study sought to advance postcolonial solidarities, highlight structural inequities, and dissect the racialized hierarchy of precarity underpinning global academia. Precarity, as an analytical tool, unveiled forms of resistance and subject position struggles. The term “Immigrant Working Students” (IWSs) disrupts the host–guest binary, challenging dominant discourses that deny epistemic equality to international students (Deuchar, 2022; Hayes, 2019). Addressing racial triangulation, white supremacy, and neoliberal academia disrupts the passive acceptance of institutionalized inequality.

Critical inquiry, as praxis, demands transformative knowledge production (Crotty, 1998). This aligns with Tikly and Bond’s (2013) insistence on decolonial critiques in international education. This study, first of its kind, explored decolonial theory and praxis, and its implications within the Icelandic milieu. It lays the groundwork for an exploration into the politics of knowledge and resistance through a decolonial lens. CIS scholars interrogate colonization’s ongoing impact, resisting Western academic hegemony. Problematizing NWE students as simultaneously objects and agents of an unsustainable imaginary (Stein & Andreotti, 2016) extends Marcuse’s (1965) repressive tolerance thesis and moves discourse beyond benevolence and innocence toward systemic analysis (Stein et al., 2022).

Methodologically, in-depth semi-structured interviews (5.5 h, 126 transcript pages) documented ISEP students’ lived realities. The COVID-19 pandemic limited the dataset, but reflexive narratives supplemented the empirical findings. Transcripts illuminated postcolonial racialization, with students explicitly framing experiences through “passing as Icelander”, whiteness, and “white European” self-presentation. These insights expose overlooked racialized and symbolic boundaries within the IHE.

This study answered the question “How do NWE students experience higher education at the University of Iceland?” by applying its theoretical pillars (e.g., Euro-Orientalism) and core concepts. Future research should extend racial triangulation analysis to Iceland, mapping power relations and subject positions in late modernity. Examining the UI’s diverse student demographics and the immigration dynamics in (Appendix C), alongside the institutional challenges, can further illuminate systemic barriers. Investigating labor market transitions, immigrant student precarity, and access to decision-making roles would deepen the understanding of structural inequalities. More crucially, fostering innovative strategies to challenge these constraints can advance postcolonial alliances and solidarities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Science Ethics Committee of The University of Iceland for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aas, K. F. (2011). “Crimmigrant” bodies and bona fide travelers: Surveillance, citizenship and global governance. Theoretical Criminology, 15(3), 331–346. [CrossRef]

- Abrar-ul-Hassan, S. (2021). Linguistic capital in the university and the hegemony of English: Medieval origins and future directions. Sage Open, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Abu-Lughod, L. (1989). The Romance of resistance: Tracing transformations of power through Bedouin women. American Ethnologist, 17(1), 41–55.

- Abu-Lughod, L. (1991) Writing against culture. In R. G. Fox (Ed.), Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present (pp. 137–162). School of American Research Press.

- Adamovsky, E. (2005). Euro-Orientalism and the making of the concept of eastern Europe in France, 1810–1880. The Journal of Modern History, 77(3), 591–628. [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P. (2004). Globalisation and the university: Myths and realities in an unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management, 10(1), 3–25. [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P., & Knight, J. (2006). The internationalisation of higher education: Motivation and realities. The NEA Almanac of Higher Education, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Amel, M. (2020). Arab marxism and national liberation: Selected writings of Mahdi Amel (Vol. 223). Brill.

- Andreotti, V.D. (2014). Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy and Practice; a Development Education Review, pp. 21–31. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arendt, A. (2023). Pride and prejudice. Proto-racism in Walerian Nekanda Trepka’s “Liber generationis plebeanorum” (c. 1624-1640), The Seventeenth Century, 38(2), 245–261. [CrossRef]

- Ayata, B., Harders, C., Özkaya, D., & Wahba, D. (2019). Interviews as situated affective encounters. A relational and processual approach for empirical research on affect, emotion and politics. In Kahl, A. (Ed.), Analyzing Affective Societies: Methods and Methodologies. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Balibar, É., & Spivak, G. C. (2016). An interview on subalternity (published in partnership with Éditions Amsterdam). Cultural Studies, 30(5), 856–871.

- Ball, S. J. (2012). Global education Inc: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Barbier, J. -C., & Théret, B. (2001). “Welfare to work or work to welfare, the French case”. In Gilbert, N. and Van Voorhis, R., Activating the Unemployed: A Comparative Appraisal of Work-Oriented Policies. Transaction Publishers. 135–183.

- Björnsdóttir, I. D., & Kristmundsdóttir, S. D. (1995). Essentialism and punishment in the Icelandic women’s movement. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 2, 171–183.

- Brandenburg, U., & de Wit, H. (2011). The end of internationalization. International Higher Education, 62. [CrossRef]

- Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2013). Encounters with racism and the international student experience. Studies in Higher Education, 38(7), 1004–1019. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. SAGE.

- Broddason, T., & Webb, K. (1975). On the myth of social equality in Iceland. Acta Sociologica, 18(1), 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Buchowski, M. (2006). The specter of orientalism in Europe: From exotic other to stigmatized brother. Anthropological Quarterly, 79(3), 463–482. [CrossRef]

- Bureychak, T. (2013). In search of heroes: Vikings and cossacks in present Sweden and Ukraine. NORMA: Nordic Journal for Masculinity Studies, 7(2), 139–159.

- Casas-Cortés, M. (2017). A genealogy of precarity: A toolbox for rearticulating fragmented social realities in and out of the workplace. In Schierup, C. -U. & Jorgensen, M. B. (Eds.), Politics of Precarity: Migrant Conditions, Struggles and Experiences. Brill.

- Caughie, P. L. (1999). Passing and Pedagogy: The Dynamics of Responsibility. University of Illinois Press.

- Chen, S. G., & Hosam, C. (2022). Claire Jean Kim’s racial triangulation at 20: rethinking Black-Asian solidarity and political science. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10(3), 455–460. [CrossRef]

- Crawley, H., & Skleparis, D. (2018). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe’s “migration crisis”. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 48–64. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Çağlar, A. (2016). Displacement of European citizen Roma in Berlin: acts of citizenship and sites of contentious politics. Citizenship Studies, 20(5), 647–663.

- Darwin Holmes, A. G. (2020). Researcher positionality - A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research - A new researcher guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(4), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Defourneaux, M. (1979). Daily life in Spain in the golden age. Stanford University Press.

- Deleuze G. & Guattari F. (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

- Deuchar, A. (2022). The problem with international students' “experiences” and the promise of their practices: Reanimating research about international students in higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 48, 504–518. [CrossRef]

- Eyþórsdóttir, E., & Loftsdóttir, K. (2016). Vikings in Brazil: The Iceland Brazil Association shaping Icelandic heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(7), 543–553. [CrossRef]

- França, T., Alves, E., & Padilla, B. (2018). Portuguese policies fostering international student mobility: A colonial legacy or a new strategy?. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(3), 325–338. [CrossRef]

- França, T., Cairns, D., Calvo, D. M., & de Azevedo, L. (2023). Lisbon, the Portuguese Erasmus city? Mis-match between representation in urban policies and international student experiences. Journal of Urban Affairs, 45(9), 1664–1678. [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E. (2018). Historic and symbolic violence in the Romani Fuenteovejuna by TNT-El Vacie: Gender, ethnicity, and interculturalism. Romance Quarterly, 65(4), 202–213. [CrossRef]

- Goldin-Perschbacher, S. (2014). Icelandic nationalism, difference feminism, and Björk’s maternal aesthetic. Women and Music: A Journal of Gender and Culture, 18, 48–81. [CrossRef]

- Gould, D. B. (2009). Moving politics: Emotion and act up’s fight against AIDS. The University of Chicago Press.

- Griech-Polelle, B. A. (2014). A matter of conscience. History: Reviews of New Books, 42(3), 75–77. [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, A. (ed.). (1994). Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Princeton University Press.

- Halewood, C., & Hannam, K. (2001). Viking heritage tourism: Authenticity and Commodification. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3), 565–580. [CrossRef]

- Harpalani, V. (2021). Racial triangulation, interest-convergence, and the double-consciousness of Asian Americans. Georgia State University Law Review, 37, 1361.

- Hawthorne, P. L. (2008). The Growing Global Demand for Students as High Skill Migrants. Transatlantic Council on Migration Annual Meeting. New York.

- Hayes, A. (2019). “We loved it because we felt that we existed there in the classroom!”: International students as epistemic equals versus double-country oppression. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(5), 554–571. [CrossRef]

- Ingvars, Á. K. (2023). Poetic desirability: Refugee men’s border tactics against white desire. NORMA, 18(4), 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Innes, P., Skaptadottir, U., & Wojtyńska, A. (2024). Using ideological disjunctures to explain lack of investment in learning the Icelandic language through formal methods. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Jefferess, D. (2012). The “me to we” social enterprise: Global education as lifestyle brand. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 6(1), 18–30.

- Johnstone, M,. & Lee, E. (2014). Branded: International education and 21 century Canadian education policy, and the welfare state. International Social Work, 57(3), 209–221.

- Jesús, A., & Pierre, J. (2020). Special section: Anthropology of white supremacy. American Anthropologist, 122(1), 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2015). Gender, poverty, and inequality: a brief history of feminist contributions in the field of international development. Gender & Development, 23(2), 189–205. [CrossRef]

- Kalmar, I. (2022). White but not quite: Central Europe’s illiberal revolt. Bristol University Press.

- Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society, 27(1), 105–138. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. Y. (2022). Globalizing racial triangulation: including the people and nations of color on which white supremacy depends. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10(3), 468–474. [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. (2008). Higher education in turmoil: The changing world of internationalization. Sense Publishers.

- Knox, D. & Hannam K. (2007). Embodying everyday masculinities in heritage tourism(s). In A. Pritchard, N. Morgan, I. Ateljevic, C. Harris (Eds.), Tourism and gender: embodiment, sensuality and experience. [CrossRef]

- Kothari, U. (2005). A Radical History of Development Studies: Individual, Institutions and Ideologies. Zed Books.

- Kuldkepp, M. (2023). Western orientalism targeting eastern europe: An emerging research programme. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies, 17(4), pp. 64–80. [CrossRef]

- Laclau, E. & Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Verso.

- Lazar, S., & Sanchez, A. (2019). Understanding labour politics in an age of precarity. Dialect Anthropol, 43, pp. 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H. (2016). The Anxiety of Sameness in Early Modern Spain. Manchester University Press.

- Lee, J.J., & Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. Higher Education, 53, 381-409. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. (2020). Virtue Hoarders: The Case against the Professional Managerial Class. University of Minnesota Press. [CrossRef]

- Loftsdóttir, K., Eyþórsdottir, E., & Willson, M. (2021). Becoming Nordic in Brazil: Whiteness and Icelandic heritage in Brazilian identity making. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 11(1), 80–94. [CrossRef]

- Loftsdóttir, K., Hipfl, B., & Ponzanesi, S. (Eds.). (2023). Creating Europe from the Margins: Mobilities and Racism in Postcolonial Europe. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Malet Calvo, D. (2018). Understanding international students beyond studentification: A new class of transnational urban consumers. The example of Erasmus students in Lisbon (Portugal). Urban Studies, 55(10), 2142–2158. [CrossRef]

- Malet Calvo, D., Cairns, D., França, T., & de Azevedo, L. F. (2022). “There was no freedom to leave”: Global South international students in Portugal during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Policy Futures in Education, 20(4), 382–401. [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, H. (1965). Repressive tolerance. In R. P. Wolff, B. Moore Jr., & H. Marcuse (Eds.), A Critique of Pure Tolerance (pp. 81–117). Beacon Press.

- McCartney, D. M., & Metcalfe, A. S. (2018). Corporatization of higher education through internationalization: The emergence of pathway colleges in Canada. Tertiary Education and Management, 24(3), 206–220. [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A. (2014). Roma as a political identity: exploring representations of Roma in Europe. Ethnicities, 14(6), pp. 756–74. [CrossRef]

- Munck, R. (2013). The Precariat: a view from the South. Third World Quarterly, 34(5), 747–762. [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, C. A. G., Latafat, S., Hammond, S., Kommers, S., Thoma, H. S., Berger, J., & Blanco-Ramirez, G. (2018). Criticality in international higher education research: A critical discourse analysis of higher education journals. Higher Education, 76, 1091–1107. [CrossRef]

- Nicolae, V. (2007). Towards a definition of anti-Gypsyism. Roma diplomacy, pp. 21–30.

- Nisbet, H.B. (1999). Herder’s conception of nationhood and its influence in Eastern Europe. In Bartlett, R., Schönwälder, K. (Eds.), The German Lands and Eastern Europe: Essays on the History of their Social, Cultural and Political Relations, pp. 115–135. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parvulescu, A. (2015). European racial triangulation. In Ponzanesi, S. & Colpani, G. (Eds), Postcolonial transitions in Europe, pp. 25–46. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Peng, S. (2022). Treating international students beyond teaching cultural differences?. Critical Internationalization Studies Review, 2(1), 18–19. [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (1996). Production and consumption of European cultural tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2). [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G., & Dean, P. (2021). Globalization: A Basic Text. Blackwell.

- Rizvi, F. (2007). Postcolonialism and globalization in education. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 7(3), 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, W. E. (2014). Positionality. In D. Coghlan, & M. Brydon-Miller (Eds.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research. Sage.

- Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- Said, E. W. (1985). Orientalism reconsidered. Cultural Critique, 1, 89–107. [CrossRef]

- Sardelić, J. (2021). The exclusion of Roma and European citizenship. Current History, 120(824), 100–104. [CrossRef]

- Schweyher, M. (2023). Precarity, work exploitation and inferior social rights: EU citizenship of Polish labour migrants in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49(5), 1292–1310. [CrossRef]

- Spivak, G., & Harasym, S. (1990). The post-colonial critic: interviews, strategies, dialogues. Routledge.

- Shultz, L. (2015). Claiming to be global: An exploration of ethical, political, and justice questions. Comparative and International Education/Éducation Comparée et Internationale, 44(1).

- Shih, S.-M. (2008). Comparative racialization: An introduction. PMLA, 123(5), 1347–1362. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25501940.

- Statistics Iceland (2024). External migration by sex and citizenship 1961-2022. Statistics Iceland Database.

- Stein, S. (2021). Critical internationalization studies at an impasse: Making space for complexity, uncertainty, and complicity in a time of global challenges. Studies in Higher Education, 46(9), 1771–1784. [CrossRef]

- Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Bruce, J., & Suša, R. (2016). Towards different conversations about the internationalization of higher education. Comparative and International Education/Éducation Comparée et Internationale, 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Stein, S., & McCartney, D. M. (2021). Emerging conversations in critical internationalizationbstudies. Journal of International Students, Suppl. Special Issue, 11, 1–14.

- Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Bruce, J., & Suša, R. (2016). Towards different conversations about the internationalization of higher education. Comparative and International Education/Éducation Comparée et Internationale, 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2022). The complexities and paradoxes of decolonization in education. In F. Rizvi, B. Lingard, & R. Rinne. (Eds.), Reimagining Globalization and Education. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Sztompka, P. (2000). Trauma wielkiej zmiany. Spoleczne koszta transformacji (Trauma of a great change. Social costs of transformation). Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN.

- Sveinsdóttir, R. (2024, February 1). Getum lært mikið af því að vinna með er-lendumsér-fræðingum. Vísir. https://www.visir.is/g/20242523293d/getum-laert-mikid-af-thvi-ad-vinna-med-er-lendum-ser-fraedingum.

- Táíwò, O. O. (2022). Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else). Pluto Press.

- Tikly, L. (2004). Education and the new imperialism. Comparative Education, 40(2), 173–198. [CrossRef]

- Tikly, L., & Bond, T. (2013). Towards a postcolonial research ethics in comparative and international education. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 43(4), 422–442. [CrossRef]

- Tlostanova, M. (2012). Postsocialist ≠ postcolonial? On post-Soviet imaginary and global coloniality. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 48(2), 130–142. [CrossRef]

- Tuck, E. & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1): 1–40.

- Vilhjálmsson, T. (2022). Into the enclosure: Collective memory and queer history in the Icelandic documentary “People like that.” NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 30(3), 208–220. [CrossRef]

- Walker, J. (2009). Time as the fourth dimension in the globalization of higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(5), 483–509.

- Welsh, H. A. (1994). Political transition processes in central and Eastern Europe. Comparative Politics, 26(4), 379–394. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.A. (1973). Herder, folklore and romantic nationalism. The Journal of Popular Culture 6(4), 819–835.

- Wojtyńska, A., Lapiņa, L., & Budginaite, I. (2022). Whiteness and racialization in/between East and West. Nordic Summer University. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365410974_Whiteness_and_racialization_inbetween_East_and_West.

- Wojtyńska, A., & Barillé, S. (2022a). Inspired by Iceland: Borealism and Geographical Imaginations of the North in Migrants’ Narratives. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 12, 276–292. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.W., & Mwangi, C.A.G. (2022). Yellow Peril and cash cows: the social positioning of Asian international students in the USA. Higher Education, 84, 1027–1044. [CrossRef]

- Ziai, A. (2019). Towards a more critical theory of “development” in the 21st century. Development and Change, 50, 458–467. [CrossRef]

- Þrastardóttir, B., & Kjaran, J. I. (2023). Girls Claiming Discursive Space within the Dominant Discourse on Gender Performativity: A Case Study from a Compulsory School in Iceland. NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 31(4), 335–348. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).