1. Introduction

As a policy tool for land management, land consolidation (LC) is commonly employed to reconcile the conflict between economic development and land use across various countries [

1]. It serves as a significant catalyst for sustainable rural development [

2] and has attracted the attention of scholars, experts, and policymakers worldwide [

3]. Relevant studies indicate that land consolidation facilitates the reduction of land fragmentation [

4], enhances land use efficiency, improves highway accessibility, optimizes rural spatial structures [

5], boosts agricultural output, increases profitability [

6] and elevates the living standards of farmers [

7]. However, due to the diverse natural, social, economic, and policy environments across different countries, substantial variations exist in the objectives, methods, and procedures of land consolidation [

8], leading to differing impacts on rural areas and farmers. China's land consolidation has progressed rapidly over the past three decades. Initially, the primary objective of land consolidation was to increase the amount of cultivated land [

9]. However, it has now evolved into comprehensive land consolidation (CLC), which aims to enhance intensive production, improve quality of life, and promote ecological sustainability [

10]. Currently, China's rural regions face significant challenges, including the abandonment of agricultural land, the vacancy of residential plots, the outflow of rural talent, and the degradation of the ecological environment [

11,

12]. These issues severely hinder the sustainable development of rural areas [

13]. Especially in the mountainous areas of southwest China, farmers encounter significant risks in their daily lives and production due to the constraints imposed by the terrain and environmental fragility, which limit available alternative livelihood options [

7]. For these farmers, land constitutes the most essential production resource, providing crucial support for survival, agricultural activities, and social security [

14,

15]. Consequently, investigating the effects of CLC on farmers' livelihood is vital for promoting sustainable development in these mountainous regions.

Currently, based on the DFID sustainable livelihood analysis framework, scholars have examined the impact of rural land consolidation on various aspects of farmers' livelihood capital [

16], including livelihood strategy [

17], livelihood resilience [

18], and farmers' income and well-being [

19]. Several other scholars have examined farmers' satisfaction levels concerning various types of livelihood capital in connection with land consolidation [

20], as well as their reactions to the preservation of arable land [

21]. However, few scholars have considered the impact on farmers' livelihoods from the perspective of all elements of CLC, including agricultural land consolidation (ALC), rural construction land consolidation (RLC), and ecological protection and restoration (EPR). In terms of research methods, scholars typically employ input-output methods (IOM), entropy weight methods (EWM), and analytic hierarchy processes (AHP) to evaluate the effects of land consolidation, the level of livelihood capital, and farmer satisfaction [

16,

22,

23]. They also utilize difference-in-difference (DID) and structural equation models (SEM) to measure the significance and correlation of land consolidation effects [

17,

24,

25]. Related research frequently examines various landform types and consolidation methods when conducting comparative analyses of the impacts of CLC [

2,

26]. However, there is a notable lack of research focusing on the differential analysis of land consolidation impacts across varying terrain gradients, from river valleys to mountainous regions. In contrast, villages in the mountainous areas of southwest China are situated near rivers, characterized by significant elevation spans and slope differences. These geographical features result in distinct living conditions and livelihood strategies for farmers at different terrain gradients, which, in turn, affect the outcomes of CLC. Therefore, it is essential to study the differences in farmers' livelihood capital under varying terrain gradients and the impact of CLC on livelihood strategy to guide the sustainable development in mountainous areas. Current studies on terrain gradients primarily focus on multiple factors, including elevation, slope, terrain relief, and terrain position index, to explore the effects of terrain gradients on regional land use, habitat quality, and rural revitalization [

27,

28,

29], thereby providing theoretical support for this research.

This study focuses on the Anning River basin in the mountainous region of southwest China, where it examines terrain gradients using elevation, slope, and the terrain position index. It collects livelihood data from farmers across different terrain gradients through a questionnaire survey, analyzes the changes in farmers' livelihood capital before and after CLC and explores the livelihood factors affecting farmers' livelihood strategy. The findings provide valuable insights for implementing land consolidation tailored to local conditions, fostering sustainable livelihoods for farmers, and promoting rural revitalization in the Anning River basin.

2. Theoretical Analysis Framework

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) developed by the United Kingdom's Department for International Development (DFID) effectively analyzes the complexities of livelihoods and the key factors influencing poverty, and it has been widely applied. The framework's key components include livelihood capital, livelihood strategy, and livelihood outcomes, which primarily examine how the reorganization of livelihood capital affects livelihood strategy and, consequently, livelihood outcomes within the context of vulnerability, thereby promoting the sustainable development of rural households [

20,

30]. Therefore, takeing SLF as a reference, this paper analyzes the influence mechanisms of all elements of CLC on the farmers’ livelihood capital and livelihood strategy (

Figure 1).

2.1. The Impact of CLC on Farmers' Livelihood Capital

Comprehensive land consolidation (CLC) is an important rural land utilization project [

31], which promotes the reorganization of farmers' livelihood capital through comprehensive measures such as agricultural land consolidation (ALC), rural construction land consolidation (RLC), and rural ecological protection and restoration (EPR). Among them, ALC has the most direct impact on farmers' natural capital, showing a dual nature [

25]. On the one hand, it can increase the area and quality of agricultural land through land leveling, field consolidation, reclamation of abandoned land, and soil improvement [

26]. On the other hand, it may also reduce the area of agricultural land by widening or building new production roads and irrigation and drainage ditches in the fields [

25]. Secondly, ALC can reduce land disputes among farmers and enhance their social capital through land ownership confirmation and adjustment [

32]. It can also improve farmers' financial capital by improving agricultural infrastructure, reducing farming costs, and increasing agricultural income. In addition, ALC enables farmers to understand relevant policies and learn management and planting skills, thereby improving the quality of the labor force [

25]. RLC has the greatest impact on the livelihood capital of relocated farmers in mountainous areas. Relocated farmers rebuild houses and supporting infrastructure in the river valley area, thereby enhancing their material capital. However, due to the change in location, farmers may transfer or abandon their mountainous agricultural land, altering their natural capital. At the same time, they can free up surplus labor to engage in non-agricultural production activities, increase family income, and enhance their financial capital. EPR mainly affect farmers' natural capital such as farmland quality, material capital such as living infrastructure, and financial capital such as non-agricultural income driven by rural ecological tourism. It has little impact on farmers' human capital and social capital.

The topography of the Anning River Basin is complex. Due to factors such as elevation, slope, relief degree, and transportation accessibility, farmers' livelihoods vary across different terrain gradients. And the content, difficulty, and objectives of CLC also differ, resulting in different impacts on farmers' livelihood capital. In the valley, the terrain is flat, the soil is fertile, and transportation is convenient. Farmers in this area find it easier to engage in agricultural production, seek employment elsewhere, understand policies, and participate in community activities, leading to a relatively higher standard of living. Nonetheless, urbanization has raised population density while diminishing the quantity of arable land, which has led to farmers possessing smaller agricultural plots and a reduction in their natural capital. ALC is a viable approach that can effectively mitigate the fragmentation of agricultural land in the valley regions [

25], although the potential for improvement remains constrained. Similarly, the impact of RLC and EPR on enhancing farmers' livelihood capital is also constrained. In medium terrain areas, the availability of extensive land and convenient transportation facilitates ALC, which can reduce the slope of cultivated land and improve land use efficiency through land leveling and slope modification. Through modern large-scale farming or land transfer, family labor resources can be reasonably allocated between agricultural and non-agricultural activities [

15], thereby increasing household income. RLC and EPR enhance farmers’ material and social capital by improving housing quality, infrastructure, and living environments. In high terrain areas, ecological protection constraints limit the availability of usable land. Additionally, poor land quality, inconvenient transportation, lagging infrastructure, and limited access to information hinder the implementation of CLC, resulting in minimal project outcomes. However, farmers who are primarily relocated benefit significantly from RLC, as their housing location, quality, and living conditions are greatly improved, providing them with more opportunities to understand policies, participate in activities, and interact with other farmers [

25], thus increasing their livelihood capital.

2.2. The Impact of CLC on Farmers' Livelihood Strategy

Livelihood strategy is regarded as the allocation and combination of capital utilization and business activities, including production activities and investment strategies [

33]. According to the classification criteria of previous studies [

32,

33,

34], based on the proportion of time spent in agriculture and other characteristics, the types of farmers' livelihood strategy are classified into five categories: traditional agriculture type, modern agriculture type, agricultural multi-employment type, non-agriculture multi-employment type, and non-agriculture type (

Table 1).

According to the research framework, the impact of CLC on farmers' livelihood strategy has two paths: one is the direct impact on farmers' livelihood strategy, and the other is the impact on livelihood strategy through the influence on farmers' livelihood capital [

35]. The direct impact of CLC is reflected in the rational allocation of family labor resources between agriculture and non-agriculture brought about by land transfer [

15]. For example, under the government-led consolidation model, farmers participate in land consolidation engineering construction, and construction enterprises absorb local farmers to participate in construction and pay wages [

36]. The agricultural operation entity-led model is based on land transfer. After farmers transfer their agricultural land, they will choose other non-agricultural employment methods [

35]. The indirect impact of CLC on farmers' livelihood strategy is mainly through the intermediary element of farmers' livelihood capital, which is mainly manifested as follows: after the implementation of CLC, if farmers' natural capital, human capital and material capital increase, it will be convenient to carry out agricultural mechanization and large-scale farming, and farmers will develop from traditional small-scale agriculture to modern large-scale agriculture. For some farmers, ALC increases the comprehensive value of the land, enabling them to obtain higher rental income from land transfer, so they are more willing to transfer agricultural land and then engage in non-agricultural production activities. Some farmers transfer the management rights of their agricultural land for a certain period by shareholding or leasing to agricultural production enterprises or agricultural cooperatives, and become agricultural workers of the management entity, obtaining wages from agricultural production [

36].

Based on the analysis of the impact of CLC on the livelihood capital of farmers at different terrain gradients, farmers in plain areas are more affected by the ALC and have more livelihood options. When farmers' human capital, financial capital and social capital increase, they can carry out business activities based on the knowledge and skills they have, and utilize available financial funds and social resources to increase the diversity of their livelihoods. Farmers in medium terrain gradient areas have more land resources and mainly engage in agricultural production, and are greatly affected by the ALC. After land leveling and slope reduction, large-scale planting can be implemented to develop modern agriculture. Farmers in mountainous areas are more affected by RCL. Due to relocation, their homesteads and agricultural land are reclaimed by the state or it is inconvenient to work on the mountains, so they may choose to work outside or do business, changing their livelihood strategies.

2.3. Selection of Farmers' Livelihood Capital Variables

Based on the theoretical analysis and related research, this paper selects livelihood capital variables from five aspects: natural, human, physical, financial, and social capital (

Table 2). The natural capital includes four indicators: cultivated land area, orchard land area, land quality, and irrigation water adequacy. Human capital is represented by two indicators: the number of family laborers and labor skill level. Material capital consists of five indicators associated with the material foundation and production resources for living: location of the house, area and quality of the house, and the value of production and living materials. Financial capital includes four indicators concerning the flow of funds and channels: annual household income, annual agricultural income, the income channels, and borrowing sources. Finally, social capital is represented by three indicators: land dispute situations, friendliness with other farmers, and participation in social activities.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

The Anning River Basin is situated within the transition zone between the Sichuan Basin, Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (101°51′-102°48′E, 26°38′-28°53′N) in southwestern China (

Figure 2). It is predominantly mountainous, with altitudes varying from 531 to 5,271 meters, demonstrating a topology characterized by higher elevations in the north and lower elevations in the south. Moreover, it comprises the second largest plain in Sichuan Province [

37]. According to the ‘Territorial Spatial Planning of Anning River Basin (2022-2035)’, the Anning River Basin covers 11 cities and counties: Renhe District, Miyi County, Yanbian County, Xichang City, Dechang County, Ningnan County, Huili City, Huidong City, Yanyuan County, Xide County and Mianning County [

37]. In March 2024, Sichuan Province released the ‘Comprehensive Land Improvement Plan for the Anning River Basin in Sichuan Province (2022-2035)’, which aims to transform the Anning River Basin into "the second granary of Tianfu" by implementing comprehensive land consolidation (ALC, RLC and EPR), so as to ensure food security and promote high quality development of the Anning River Basin. Therefore, researching the impact of CLC on farmers' livelihoods in the Anning River Basin is both representative and advantageous for the successful implementation of these initiatives.

3.2. Data Source

The digital elevation model (DEM) was obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud website (

https://www.gscloud.cn/) and has a spatial resolution of 30 meters. Slope data were derived from the DEM, enabling the calculation of average elevation and slope for each village through regional statistics [

26] Administrative boundary data for countries, provinces, and cities were sourced from the Ali Cloud Data Visualization Lab (

https://datav.aliyun.com/portal), while data for towns and villages were provided by local government authorities. Regarding the farmers' livelihood data, our research team conducted a questionnaire survey in the study area in August 2024 through random sampling and face-to-face interviews. our research team conducted a questionnaire survey in August 2024 using random sampling and face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire covered various aspects, including the demographics of farmers and their families, changes in farmers' livelihood capital (natural, human, physical, financial, and social), and shifts in livelihood strategies before and after CLC. A total of 320 questionnaires were distributed, with 307 valid responses retained after excluding incomplete submissions, resulting in an effective response rate of 95.9%. Among the valid submissions, 165 were from regulated areas and 142 from unregulated areas. Based on terrain gradients, the survey consisted of 100 respondents from low terrain areas, 106 from medium terrain areas, and 101 from high terrain areas.

3.3. Terrain Gradient Division

Elevation and slope, as critical terrain factors, significantly influence regional land use and the effectiveness of CLC [

38]. However, their effects are interdependent rather than independent. The terrain Position Index (TPI) is a measure that reflects elevation and slope, effectively encapsulating how these elements impact land use on a regional scale [

28]. The formula is as follows:

is the terrain position index of the

village;

,

is the average elevation and slope of the

village;

,

is the average elevation and slope of the Anning River basin [

27]. The higher the elevation and the steeper the slope, the larger the terrain position index [

38].

This paper categorizes the terrain gradient of the Anning River basin into six grades and three terrain regions based on elevation, slope, and the terrain Position Index (TPI), providing a terrain basis for the selection of sample villages. Elevation is divided into six grades with 600 meter intervals using the equal spacing method: (600 m, 1200 m], (1200 m, 1800 m], (1800 m, 2400 m], (2400 m, 3000 m], (3000 m, 3600 m], and (3600 m, 4200 m]. According to the critical slope grading method, slope is categorized into six grades: (0°, 2°], (2°, 6°], (6°, 15°], (15°, 25°], (25°, 35°], and (35°, 45°]. The terrain Potential Index is divided into six grades using the natural breakpoint method [

28,

38].

3.4. Calculation of the Livelihood Capital Index

Considering the inherent differences in data and the significance of various indicators, this paper employs a hybrid weighting method that combines the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Coefficient of Variation (COV) to assess livelihood capital indicators [

25,

39]. Subsequently, the comprehensive index method is utilized to calculate the livelihood capital indexes (LCI) of farmers. The formulas are as follows:

,

,

,

are respectively the coefficient of variation, standard deviation, arithmetic mean and standardized value of the variable

.

,

,

are the weights calculated by COV, AHP, and weighted average respectively.

represents the livelihood capital index.

3.5. Difference-in-Differences Model (DID)

The difference-in-difference (DID) model is commonly employed to study the effects of policy interventions. Its basic logic involves dividing survey samples into a treatment group and a control group, measuring the changes in both groups before and after the policy, and then calculating the difference between these changes to reflect the net effect of the policy [

26]. In this study, CLC is regarded as a policy, with the treatment group consisting of farmers who implemented CLC, while the control group comprises farmers who did not. Based on the implementation timeline, the samples can be divided into four groups, distinguished by adding two dummy variables

and

[

17].

=1 represents the farmers in regulated area,

=0 represents the farmers in unregulated area,

=0 corresponds to farmers before CLC,

=1 corresponds to farmers after CLC. The DID model is constructed as follows:

is the explained variable, i represents the i farmer, t represents the t year,

is the interaction term of

and

.

,

represents the implementation effect and time effect of CLC, and

is the net effect of CLC concerned by this study.

is the coefficient to be estimated,

is the random disturbance term.

3.6. Ordered Logistic Regression Model (OLR)

The ordered logistic regression model is suitable for regression problems involving ordered categorical data [

34]. In this study, the farmers' livelihood strategies are classified into five types based on the proportion of family labor input into agricultural work. The classification follows the sequence of livelihood non-agriculturalization and is suitable for ordered logistic regression analysis. This study utilizes Stata 17.0 software, treating farmers' livelihood strategies as the dependent variable, and land comprehensive consolidation and livelihood capital as control variables. It conducts ordered logistic regression analysis on the farmers' livelihood data before (model 1) and after (model 2) CLC under different terrainal gradients, aiming to explore the impact of CLC on farmers' choices of livelihood strategies.The model formula is as follows:

is the latent variable of livelihood strategy

,

represents the probability of farmers' livelihood transformation, is the intercept,

is the explanatory variable,

is the regression coefficient of each explanatory variable, and

is a random disturbance term following a normal distribution. Before regression, multiple collinearity tests are conducted on the explanatory variables using Stata 17.0 to avoid inaccurate parameter estimation and affect the significance of the test variables [

40]. When the variance inflation factor (VIF) is less than 10, it indicates that there is no collinearity among the explanatory variables, and regression analysis can be conducted [

40]. After the analysis, the parallelism test of the independent variable coefficients is performed based on the model chi-square value. If the significance level of the chi-square value is greater than 0.05, the parallelism test is passed, and subsequent analysis can be carried out [

41].

4. Results

4.1. Results of Terrain Gradient Division

The regional terrain gradients are categorized into three regions based on elevation, slope, and the Terrain Position Index (TPI), as shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 3. It can be observed that the average elevation of most villages in the Anning River basin is between 1200 m and 3000 m, which corresponds to grades II, III, and IV, accounting for 28.89%, 39.84%, and 23.63%, respectively. The average slope of most villages ranges from 6° to 35°, corresponding to grades III, IV, and V, accounting for 15.8%, 58.43%, and 21.02%, respectively. The terrain potential index of villages in the Anning River basin ranges from 0.235 to 0.848. Specifically, 28.71% of the villages are located in low terrain areas (grades I and II), with a terrain location index between 0.234 and 0.497, primarily situated along the main stream of the Anning River, in shallow hill regions, the Yanyuan Basin, and the Heishui River valley. Additionally, 49.91% of the villages fall within medium terrain areas (grades III and IV), exhibiting a terrain location index ranging from 0.497 to 0.626, predominantly found in the low mountain regions on both sides of the Anning River, deep hill areas, and the low mountain areas of the Yanyuan Basin. Lastly, 21.39% of the villages are situated in high terrain areas (grades V and VI), mainly distributed along the upper and western banks of the Anning River, and parts of the high terrain area of Ningnan County and Dechang County, with a terrain position index between 0.626 and 0.848.

The purpose of this research is to reveal the varying impacts of CLC on farmers' livelihood across different terrain gradients. Accordingly, sample villages in low terrain areas, medium terrain areas, and high terrain areas were selected based on the classification of terrain gradients. Meanwhile, the CLC projects in the sample villages were well implemented, incorporating at least two of the following three projects: Agricultural Land Consolidation (ALC), Rural Construction Land Consolidation (RLC), and Ecological Protection and Restoration (EPR). The implementation timeline was controlled within 2019 to 2023 to ensure the comparability and accuracy of the data. In summary, the villages involved in the Zichu Village Land Consolidation Project, Qiulin Village Land Consolidation Project, Si Azu Village Land Consolidation Project, and Hongmo Town Beautiful China Ecological Civilization Construction Project, were selected as the sample villages (

Figure 3).

4.2. The Impact of CLC on Farmers' Livelihood Capital

4.2.1. Descriptive Analysis of Variables

The data regarding farmers' livelihood capital before and after CLC across different terrain gradients are presented in

Table 4. First and foremost, land is a fundamental resource for farmers' livelihoods. Before CLC, the distribution of cultivated land owned by farmers was as follows: low terrain area < medium terrain area < high terrain area. After CLC, the cultivated land area decreased from 3367 m² to 2533 m² in the low terrain area, from 5740 m² to 4127 m² in the medium terrain area, and from 5933 m² to 3575 m² in the high terrain area. The distribution of orchard land owned by farmers was: medium terrain area < low terrain area < high terrain area before regulation; after regulation, there was an increase in orchard land in medium terrain areas, while the area of orchard land in both low terrain and high terrain areas experienced a decline.. Second, human capital increased across all three regions. In terms of material capital, the production materials and living materials for farmers in the low terrain area exhibited the most significant increase, while the housing area for farmers in the medium terrain area expanded the most, and the housing quality for farmers in the high terrain area improved the most. Regarding financial capital, prior to regulation, annual household income and agricultural income were ranked as follows: low terrain area > medium terrain area > high terrain area. Land consolidation has increased the annual household income and agricultural income for farmers across all three regions, contributing to a wider range of income and loan sources. Finally, in terms of social capital, land consolidation has reduced land ownership disputes among farmers in all three regions, increased friendships among farmers, and bolstered farmers' enthusiasm to participate in social activities. To sum up, except for the cultivated land area, orchard land area, and location of housing, the other variables of farmers' livelihood capital showed improvement.

4.2.2. Change Characteristics of Farmers' Livelihood Capital

The farmers' livelihood capital index (LCI) before and after CLC across different terrain gradients is shown in

Figure 4. Farmers' LCI increased from 0.432 to 0.492 in the low terrain area, from 0.429 to 0.494 in the medium terrain area, and from 0.390 to 0.423 in the high terrain area, indicating that the growth of farmers' livelihood capital exhibited a trend of medium terrain area > low terrain area > high terrain area. Analyzing the individual indices of livelihood capital reveals that the natural capital index for farmers increased in medium terrain areas, but decreased in the low terrain and high terrain areas. The human capital index, physical capital index, financial capital index, and social capital index for the three regions all increased. Among these, the human capital index before and after CLC displayed the trend of medium terrain area > low terrain area > high terrain area. The physical capital index and financial capital index were high, with significant increases, indicating that physical and financial capital are crucial to farmers' livelihoods. There is little variation in the farmers' social capital, which all shows an increasing trend.

4.2.3. Net Effect of Land Consolidation

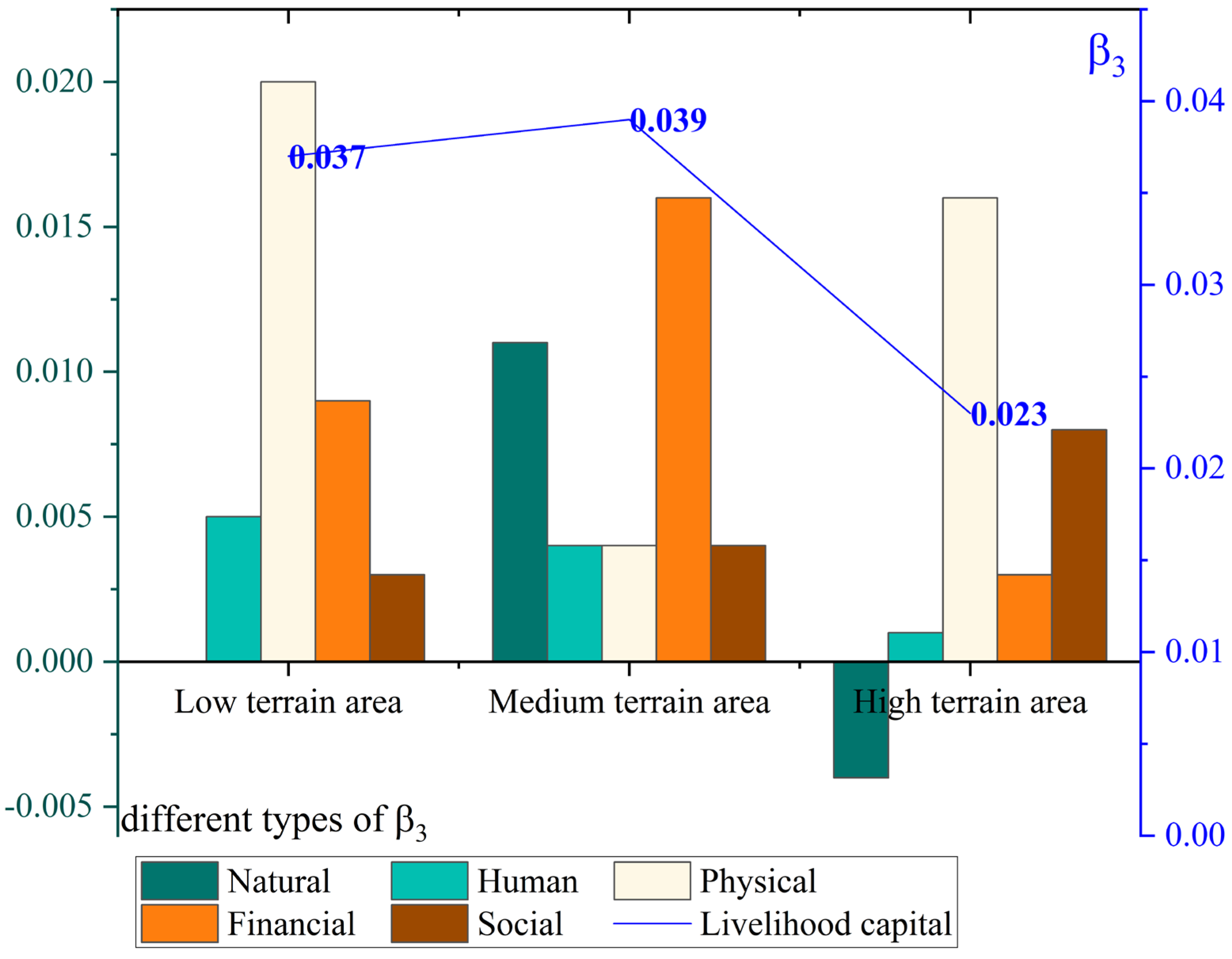

The net effect values of CLC for different terrain gradients are shown in

Figure 5. The net effect values of farmers' livelihood capital in the low terrain area, medium terrain area, and high terrain area are 0.037, 0.039, and 0.023, respectively. Therefore, the positive net effect of CLC on farmers' livelihood capital follows a trend that can be ranked as medium terrain area > low terrain area > high terrain area. When considering the net effect on individual capital components, it is evident that CLC primarily enhances physical and financial capital for farmers in the low terrain area. This indicates that CLC significantly improves the area and quality of their housing, improves household production and living materials, and increases agricultural and household income. For farmers in the medium terrain area, the net effect values of natural capital and financial capital are relatively large, which indicates that CLC significantly increases the quantity and quality of land and increases agricultural and household income. For farmers in the high terrain area, CLC primarily enhances physical capital and social capital, mainly because farmers there have improved the quality of their housing and living materials through relocation or on-site house renovation. After moving to the concentrated settlement, they have more contact with surrounding farmers and have easier access to policy information, so the net effect values of physical capital and social capital are more significant.

4.3. The Impact of CLC on Farmers' Livelihood Strategies

4.3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Variables

The data on farmers' livelihood strategies before and after CLC in different terrain gradients are shown in

Table 5. It can be seen that before CLC, the main livelihood type of the total sample farmers was agriculture multi-employment type, with a total of 162 cases, accounting for 52.77%. The traditional agricultural type and non-agriculture multi-employment type followed. After CLC, the traditional agricultural type farmers converted to modern agricultural type and agriculture multi-employment type. The non-agricultural input and income of agriculture multi-employment type farmers increased, converting to non-agriculture multi-employment type farmers. This indicates that CLC has led to a development trend towards diversified and non-agricultural livelihood for farmers.

From the perspective of different terrain gradients, the main livelihood type of farmers in the low terrain area before CLC was agriculture multi-employment type, accounting for 46.6%. After CLC, the agriculture multi-employment type and traditional agricultural type decreased, while the non-agricultural multi-employment type increased, with the overall change trend consistent with that of the total sample. For farmers in the medium terrain area, the main livelihood type was agriculture multi-employment type both before and after CLC, but the proportion decreased from 54.7% to 42.7%. Most traditional agricultural type farmers transformed to modern agricultural type, and agricultural multi-employment type farmers transformed to non-agricultural multi-employment type. For farmers in the high terrain area, the main livelihood type was agricultural multi-employment type , but the proportion decreased from 57.4% to 45.5%. After CLC, the traditional agricultural type significantly decreased, while the non-agricultural multi-employment type significantly increased.

4.3.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Farmers' Livelihood Strategies

This study used stata17.0 software to conduct an ordered logistic regression analysis of farmers' livelihood data before (Model1) and after (Model2) CLC under different terrain gradients. Model 1 reveals that the livelihood transitions of farmers in low terrain areas are significantly influenced by labor skill levels, annual household income, borrowing channels, and friendliness with other farmers before CLC. In contrast, the livelihood transitions of farmers in medium terrain areas are primarily affected by cultivated land area, annual household income, annual agricultural income, income channels, and land dispute situations. For farmers in high terrain areas, significant influences come from irrigation water adequacy, annual household income, annual agricultural income, and income channels. Notably, cultivated land area, irrigation water adequacy, annual agricultural income, and friendliness with other farmers have a significant negative impact. This indicates that the more arable land and irrigation water farmers have, the more motivated they are to engage in agricultural production. Furthermore, better neighborly relations increase the likelihood of farmers choosing to stay and develop in their hometown rather than seeking employment or business opportunities elsewhere. Labor skill levels, annual household income, income channels, and land disputes have a significant positive impact on the diversification and non-farm activities of farmers' livelihoods, suggesting that the more skills farmers possess, the greater the variety of livelihood options available to them. Additionally, with more income channels and higher annual household income, farmers are better equipped to engage in diversified production activities.

According to the results of Model 2, the direct impact of CLC on the livelihood transition of farmers in low terrain areas is significant, while its effects in medium terrain and high terrain areas are not significant. From an indirect perspective, CLC has strengthened the significance of the negative impact of cultivated land area across all three regions, indicating the critical role that cultivated land plays in livelihood activities. If the cultivated land area increases and its quality improves, farmers can engage in larger-scale modern production. Conversely, a reduction in cultivated land area may drive farmers to seek non-farm livelihood activities such as business or labor outside. Furthermore, CLC has significantly enhanced the positive impact on the labor skill levels in low terrain areas, indicating a substantial improvement in the skills of farmers, thereby facilitating greater livelihood diversification. It has also increased the positive impact of the number of household laborers in high terrain areas. This is primarily due to the relocation of farmers and a reduction in agricultural land, allowing families with more labor to engage in local or external labor activities in addition to agricultural production. Additionally, CLC has reduced the positive impact of annual household income on livelihood transitions in low terrain areas while increasing the negative impact of income channels, whereas its effects in medium terrain areas and high terrain areas remain relatively stable.

5. Discussion

Land is the most important production factor and source of livelihood for farmers, especially in the rural areas of the southwestern mountainous regions where alternative livelihood options are scarce [

7]. CLC is expected to significantly impact farmers' livelihoods. However, existing research has rarely considered the differential impacts of CLC across various terrain gradients. This study addresses this gap by analyzing the effects of CLC on farmers' livelihoods from a theoretical perspective, taking into account the complex topography of the Anning River Basin. By calculating the Livelihood Capital Index based on household livelihood data, we examine the changes in livelihood capital before and after CLC. The results indicate that CLC has both positive and negative impacts on farmers' natural capital, while positively affecting human, material, financial, and social capital. This aligns with the findings of Zhang [

7] and Xie [

25]. But the predecessors focused on the effects of agricultural land consolidation, whereas this study provides a comprehensive analysis of all elements involved in CLC. Across different terrain gradients, the changes in farmers' livelihood capital and the net effects of CLC exhibit a trend of medium terrain areas > low terrain areas > high terrain areas, which is consistent with Zhang’s conclusions regarding the income effects of agricultural land consolidation based on landform types [

26]. This trend can primarily be attributed to the substantial landholdings of farmers in the medium terrain areas, which, after participating in CLC, have led to large-scale cultivation, improved land use efficiency, and increased agricultural output, resulting in significant gains in natural and financial capital for these farmers.

In terms of farmers' livelihood strategy, CLC has led to a general shift towards diversification and non-farm activities, aligning with the conclusions of Wu [

42] that the construction of high-standard farmland promotes the transition of traditional smallholder livelihood strategies towards diversification and non-farm activities. However, changes in livelihood strategies across different terrain gradients exhibit variability. In the low terrain areas, farmers are transitioning from traditional agricultural type and agriculture multi-employment type to non-agriculture multi-employment type and non-agriculture types. This shift is primarily due to the fact that many farmers in the low terrain area have transferred their land, allowing them to engage in diverse livelihood activities, consistent with the findings of Han [

43]. In medium terrain areas, farmers are transitioning from traditional agricultural types to modern agricultural types, as CLC has resulted inenabling farmers to participate in village cooperatives for large-scale modern agricultural production. In high terrain areas, the shift is mainly from traditional agricultural and agriculture multi-employment type to non-agriculture multi-employment type. This is because farmers in these areas have seen their farmland become state-owned after relocating, with family labor primarily engaged in local and external wage work and business activities, resulting in minimal agricultural production. Using the ordered logistic regression model, this study assesses the direct and indirect impacts of CLC on farmers' livelihood strategies and identifies the livelihood factors influencing these strategies. This provides a scientific basis for the selection of livelihood strategies and promotes the sustainable development of farmers in mountainous areas.

However, this study has some limitations. First, CLC is a complex project that includes agricultural land consolidation, construction land consolidation, and rural ecological protection and restoration. The analysis of the impact of CLC on farmers' livelihood capital and strategies is somewhat general and lacks in-depth research on the effects of different land consolidation projects on farmers' livelihood, which is insufficient to establish an impact mechanism. Second, the sample villages selected for the survey are limited in number. While they were chosen based on multiple criteria to ensure some degree of representativeness, the results may not adequately reflect the impact of CLC on rural areas throughout the Anning River Basin. Continued follow-up with households in land consolidation project areas is needed to guide sustainable livelihood development for farmers.

6. Conclusions

In the context of developing the "Second Granary of Tianfu" in the Anning River Basin, this study considers the complexity of the region's topography by classifying it into terrain gradient zones based on elevation, slope, and terrain position index. Utilizing livelihood data from 307 households across different terrain gradients, we calculated the Livelihood Capital Index and analyzed the changes in livelihood capital before and after CLC, as well as the effects of terrain gradients. The following conclusions were drawn: (1) The Livelihood Capital Index for farmers in low terrain areas increased from 0.432 to 0.492, from 0.429 to 0.494 in medium terrain areas, and from 0.390 to 0.423 in high terrain areas, indicating a trend of medium terrain areas >low terrain areas> high terrain areas. (2) The net effects of CLC in the low terrain areas, medium terrain areas, and high terrain areas were 0.037, 0.039, and 0.023, respectively, consistent with the terrain gradient effects on livelihood capital growth. (3) After CLC, the trend of livelihood type transformation for farmers generally shifted from traditional agricultural type to modern agricultural type and agriculture multi-employment type, and from agriculture multi-employment type to non-agriculture multi-employment type. (4) The ordered logistic regression model indicates that CLC has a significant direct impact on the livelihood transition of farmers in low terrain areas, while its effects in medium terrain areas and high terrain areas are not significant. From an indirect perspective, CLC significantly influences farmers’ livelihood transitions by affecting cultivated land area, irrigation water adequacy, labor skill levels, the value of production materials, annual household income, annual agricultural income, income channels, borrowing channels, and land disputes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.R. and Y.H.; methodology, W.R. and Y.B.; software, W.R.; validation, Z.D. and H.Y.; formal analysis, W.R.; investigation, W.R., Y.H., Z.D. and H.Y.; resources, Y.H. and Y.B.; data curation, W.R. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, W.R.; writing—review and editing, W.R. and Y.H.; visualization, W.R. and Z.D.; supervision, Y.B.; project administration, Y.H. and Y.B.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (Grant Number: 41671529) and Research Projects of Department of Natural Resources of Sichuan Province (New Think Tank Research Projects)(Grant Number: KJ-2024-021).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Long, H.; Tu, S. Land use transition and rural vitalization. China Land Science 2018, 32(7), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tunali, S.P.; Dagdelen, N. Comparison of different models for land consolidation projects: Aydin yenipazar plain. Land Use Policy 2023, 127, 6590–6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgan, M.; Bavorova, M. How to increase landowners' participation in land consolidation: Evidence from north macedonia. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 6424–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S.T.A. Evaluation of land consolidation projects with parcel shape and dispersion. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 5401–5401. [Google Scholar]

- Stanczuk-Galwiaczek M. Analysis of changes in spatial structure of rural areas in poland resulting from land consolidation - a case study. Geographic Information Systems Conference and Exhibition, GIS ODYSSEY 2016 2016, 235-245.

- Lazic J.; Marinkovic G.; Borisov M.; Trifkovic M.; Grgic I. Effects and profitability of land consolidation projects: Case study - the republic of serbia. Tehnicki Vjesnik-Technical Gazette 2020, 27(4),1330-1336.

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, D.; Jiang, J. Integrated features and benefits of livelihood capital of farmers after land transfer based on livelihood transformation. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2018, 34(12), 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Timothy, D.J. An assessment of farmers' satisfaction with land consolidation performance in china. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y. Basic logic, key issues and main relations of comprehensive land consolidation. China Land Science 2022, 36(11), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Ye Y.; Lin Y. Experience and enlightenment of multifunctional land consolidation in germany,japan and taiwan in china. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University(Social Sciences Edition) 2019, 3,140-148,165,166.

- Lin, Y.; Yang, R.; Ge, Y. Internal logic and transmission mechanism of rural comprehensive land consolidation for rural revitalization. Planners 2023, 39(05), 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Land consolidation and rural vitalization. Acta Geographica Sinica 2018, 73(10), 1837–1849. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Wen, Y. Review on household livelihood in china. Forestry Economics 2016, 38(04), 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. Land transfer,increase of farmers'income and income inequality. Rural Economy 2021, 06(06), 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; Xia, X. Research on the influence of land consolidation on farmers'income gap. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics 2024, 8(8), 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, G. Change of farmers' livelihood capital before and after rural land consolidation in different modes. China Land Science 2018, 32(10), 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, W. The influence of rural land consolidation on households' livelihood strategies based on psm-did method. Journal of Natural Resources 2018, 33(9), 1613–1626. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, H.; Lu, X. Impact effects and mechanisms of comprehensive land consolidation on farmers' livelihood resilience:A case study of some counties in hubei province. Research of Agricultural Modernization 2023, 44(6), 1002–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, J. The effect on poverty alleviation and income increase of rural land consolidation in different models: A china study. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 4989–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Feng, Z.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, H. Study on farmers' satisfaction with land consolidation performance from the perspective of livelihood capital: A case study of ranyi town, sichuan province. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis 2020, 56(2), 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y.; Zhao K.; He J.; Qu M. Effect of capital endowment on farmers' decision-making in protecting cultivated land in a rice-growing area: An empirical study based on a double-hurdle model. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture 2019, 27(6),959-970.

- Hiironen, J.; Riekkinen, K. Agricultural impacts and profitability of land consolidations. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.; Deng, W. Measuring the role of land consolidation to community revitalization in rapidly urbanizing rural china: A perspective of functional supply-demand. Habitat International 2025, 155, 3237–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Giorgio, O.; Robinson, B.E.; de Waroux, Y.l.P. Impacts of agricultural commodity frontier expansion on smallholder livelihoods: An assessment through the lens of access to land and resources in the argentine chaco. Journal of Rural Studies 2022, 93, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G. Influence mechanism and empirical analysis of rural land consolidation on the income and welfare of rural households. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics 2020, 12(12), 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, G. How can rural land consolidation increase farmers' income: Heterogeneity analysis based on consolidation modes and geomorphic types. Journal of Natural Resources 2021, 36(12), 3114–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; An, J.; Yang, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, X. Potential and development paths of rural revitalization in qinling-daba mountains,china under different terrain gradients. Journal of Earth Sciences and Environment 2024, 46(01), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; He-Yang, Y.; Tang, H.; Chen, C.; He, K. Terrain gradient effect and functional zoning of land use change in the red river basin of yunnan province. Journal of Yunnan University Natural Science 2024, 46(2), 276–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, P.; Chen, H.; Han, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution of habitat quality in the weihe river basin and its topographic gradient effects and influencing factors. Arid Land Geography 2023, 46(03), 481–491. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q. Research progress and future key trends of sustainable livelihoods. Advance in Earth Sciences 2015, 30(7), 823–833. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Scientifically promoting the strategy of reclamation and readjustment of rural land in china. China Land Science 2011, 24(4), 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Wang X.; Xiong G. Impacts of farmland consolidation on farmers'livelihood strategies based on sustainable livelihoods framework. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2020, 40(2),269-277-269-284.

- Su, F.; Xu, Z.; Shang, H. An overview of sustainable livelihoods approach. Advance in Earth Sciences 2009, 24(1), 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. Impacts of land consolidation on households' livelihood transformation and its effects under the background of rural vitalization. Huazhong Agricultural University,Wuhan, 2019.

- Xie, J.; Yang, G.; Xu, Y. The impact of different rural land consolidation modes on rural households' livelihood strategies: Examples from some counties and cities from the jianghan plain and mountainous areas in hubei province. Chinese Rural Economy 2018, 11, 96–111. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Impacts of rural land consolidation on farmers' livelihood: A case study of tianmen, qianjiang and enshi in hubei province. Huazhong Agricultural University,Wuhan, 2018.

- Chen, L.; Wang, C. Characteristics and driving factors of non-grain production of cultivated land in anning river basin of sichuan province. Chinese Journal of Soil Science 2024, 55(2), 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- An B.; Xiao W.; Cui X. Topographic gradient effect of land use pattern in hanjiang river ecological economic belt. Research of Soil and Water Conservation 2024, 31(4),288-297,307.

- Ding, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Da, R.; Wu, J.; Yu, S.e. Comprehensive benefit evaluation of land consolidation based on perspective of production,living and ecology. Yellow River 2020, 42(10), 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Z. Differences in farming households’ cognition of ownership adjustment benefits in rural land consolidation and causes. Resources Science 2019, 41(07), 1329–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y. An analysis of people’s satisfaction degrees and influencing factors in treatment of empty houses in rural areas:A case study of xiangyin county in hunan province. Journal of Yichun University 2022, 44(11), 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, H.; Lu, X. Impact of high-standard farmland construction on farmers'livelihood strategies and its benefits. Agricultural Economics and Management 2024, 06, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Zhang, Z. The impact of farmland transfer on diversified livelihood strategies of farmers:An empirical analysis based on the national household survey. Scientific and Technological Management of Land and Resources 2024, 41(02), 75–89. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).