1. Introduction

Meningioma-related epilepsy (MRE) occurs in 30% of patients with supratentorial meningiomas and is, in 20%-50% of cases, the presenting symptom [27,28]. Surgical resection leads to recovery in 60% of cases, with persistence of MRE after surgery in 30-40% of cases [18]. MRE significantly impacts patients' quality of life due to recurrent seizures, which lead to limitations in daily activities' autonomy and the side effects of antiseizure medications (ASM), primarily affecting cognitive functions [6,20]. Although the mechanisms of epileptogenesis in MRE are not fully understood, the initiation of ASMs is recommended after the first epileptic seizure in the presence of a supratentorial meningioma [26]. Therefore, the indication for ASM therapy is independent of the tumor's radiological characteristics, seizure semiology, and, in general, patient-specific factors. This highlights how the definition of MRE encompasses a wide variety of patients who must start ASM independently of each character.

While the presence of a supratentorial meningioma may justify such a broad indication for ASM initiation, the same cannot be said for the continuation and discontinuation of ASMs throughout the clinical course of these patients. There is no recognized protocol for discontinuing ASMs after radical resection of a supratentorial meningioma. Due to a lack of clear scientific evidence, the decision of when and whether to stop these medications remains entirely at the clinician's discretion, and this is one of the main unresolved issues in clinical practice regarding managing MRE [9]. Although numerous clinical studies have identified risk factors for MRE [4,5,14,17,19,21], none have pinpointed risk factors that could support a recognized protocol for postoperative ASM management. Clinicians often choose to continue ASMs for many years after radical meningioma surgery, even in the absence of seizures, due to the fear of recurrent seizures. In light of this, we decided to investigate which characteristics of epileptogenic naïve meningiomas in the preoperative period could reassure clinicians in their decision to discontinue ASMs.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study retrospectively collected a series of patients with naïve supratentorial meningioma surgically treated at our Center between January 2020 and December 2022. The retrospective data collection was carried out using our hospital's computerized database. We included all patients with naïve supratentorial meningioma who underwent radical surgical resection, provided that preoperative and follow-up clinical and radiological data were available for at least 12 months.

We excluded cases of recurrence/postsurgical residuals, multiple meningiomatosis, death within 12 months after treatment, and all cases in which preoperative and postoperative MRI and clinical data were not available.

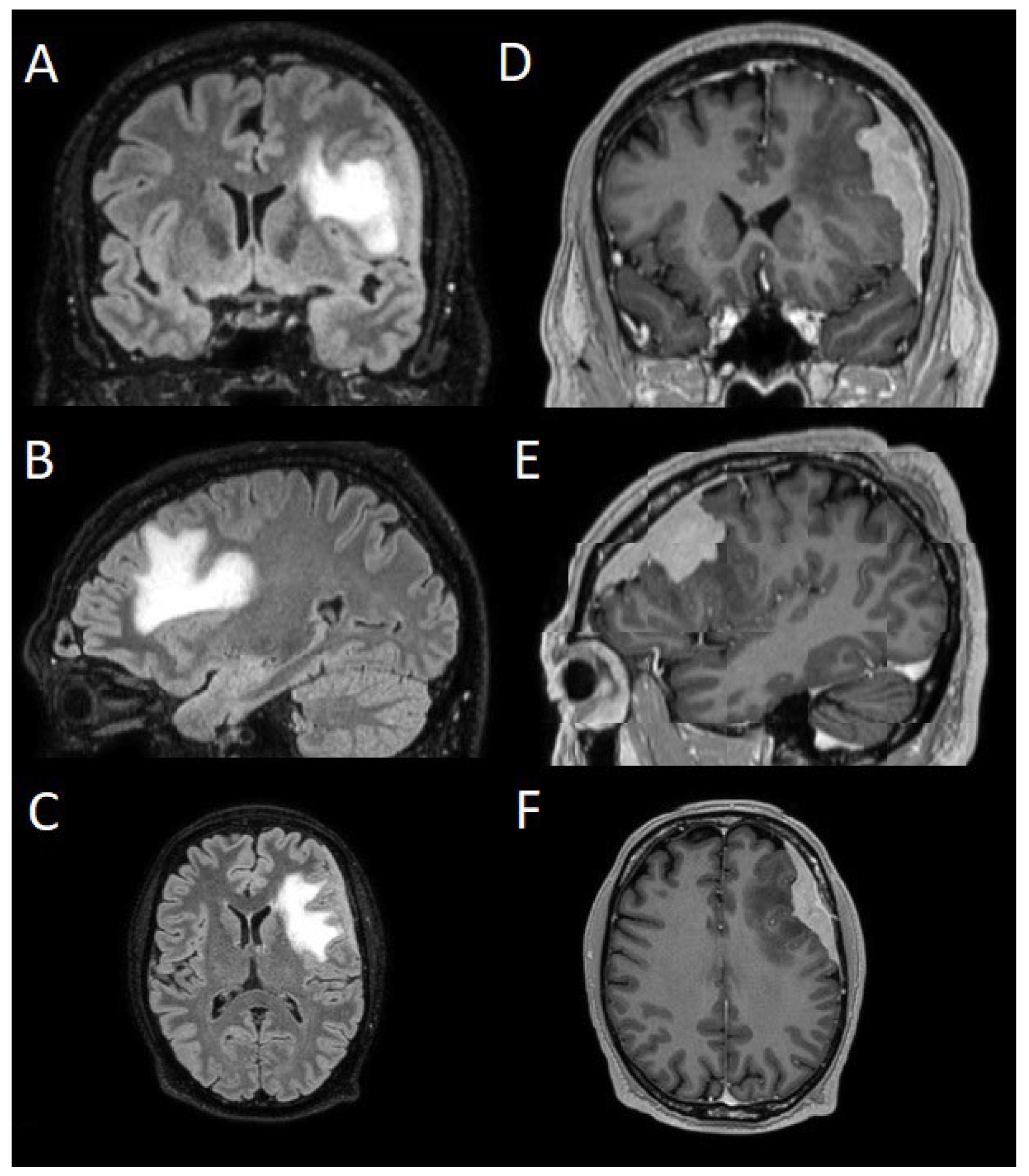

The patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at our Center using a 1.5T or 3T Tesla MRI machine (Ingenia 3T, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) with the standard oncological protocol [7]. Specifically for analysis, the sequences collected were T1-weighted with contrast enhancement to estimate tumor volume and conformation and FLAIR (Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) to quantify PE (

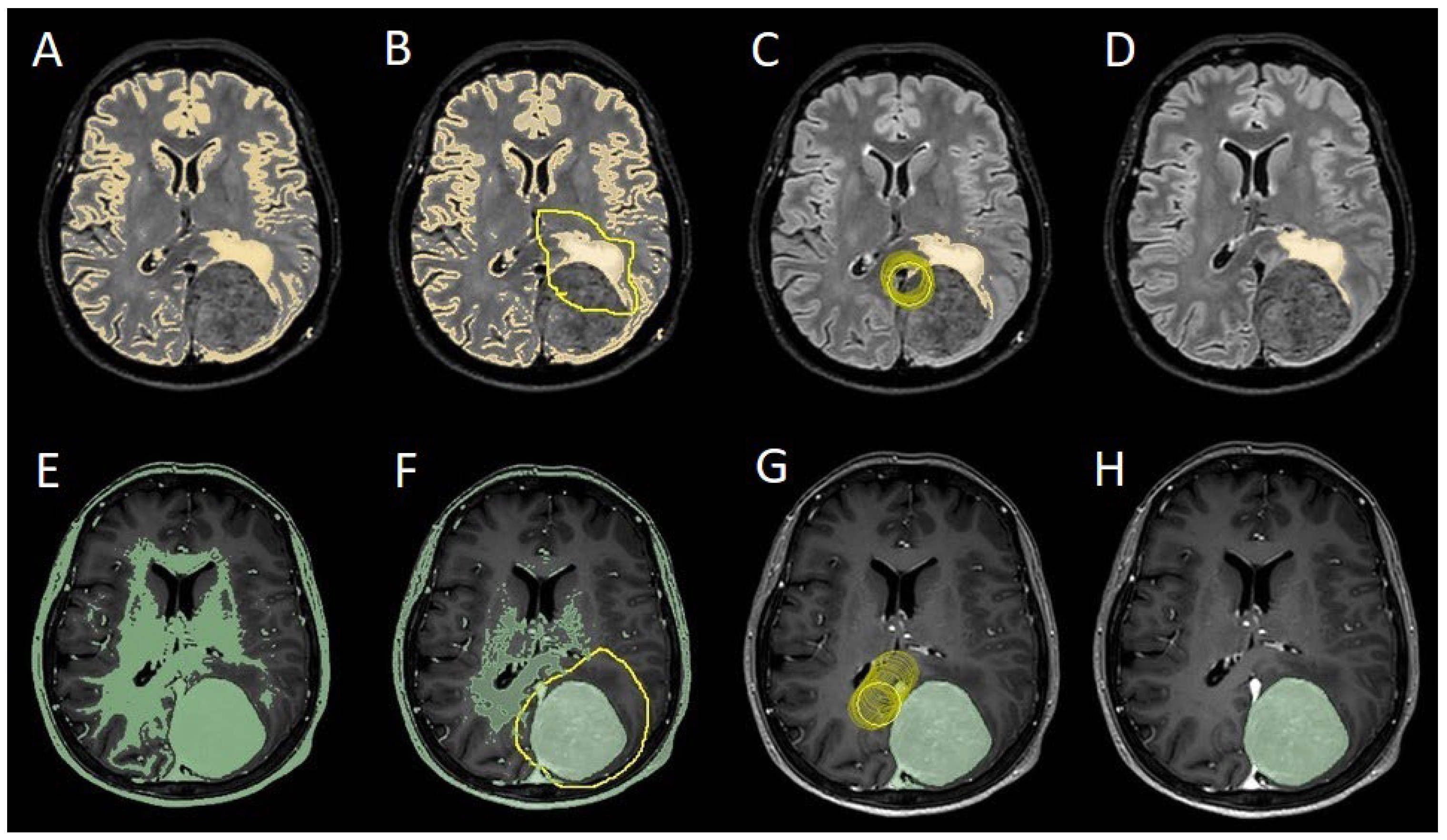

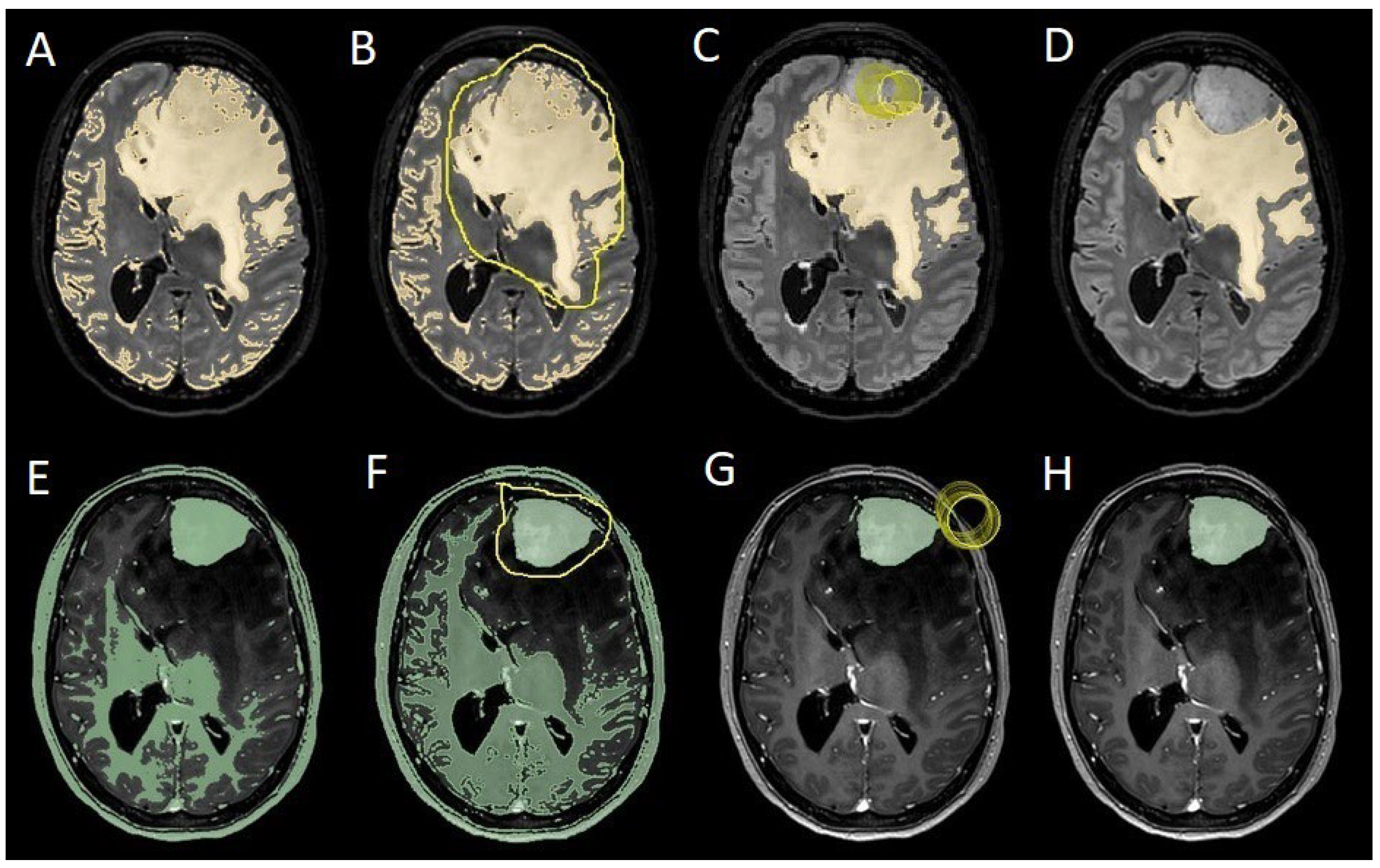

Figure 1). We manage the preoperative imaging in DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format. The images from the T1-weighted with contrast enhancement and FLAIR sequences in DICOM format were processed through the Slicer website [12]. Tumor and PE segmentation was performed using a voxel-based analysis that integrated automated and manual methods (

Figure 2). The process begins with an automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values (

Figure 2A, 2E). This is followed by manual refinement to enhance accuracy and delineate precise boundaries (

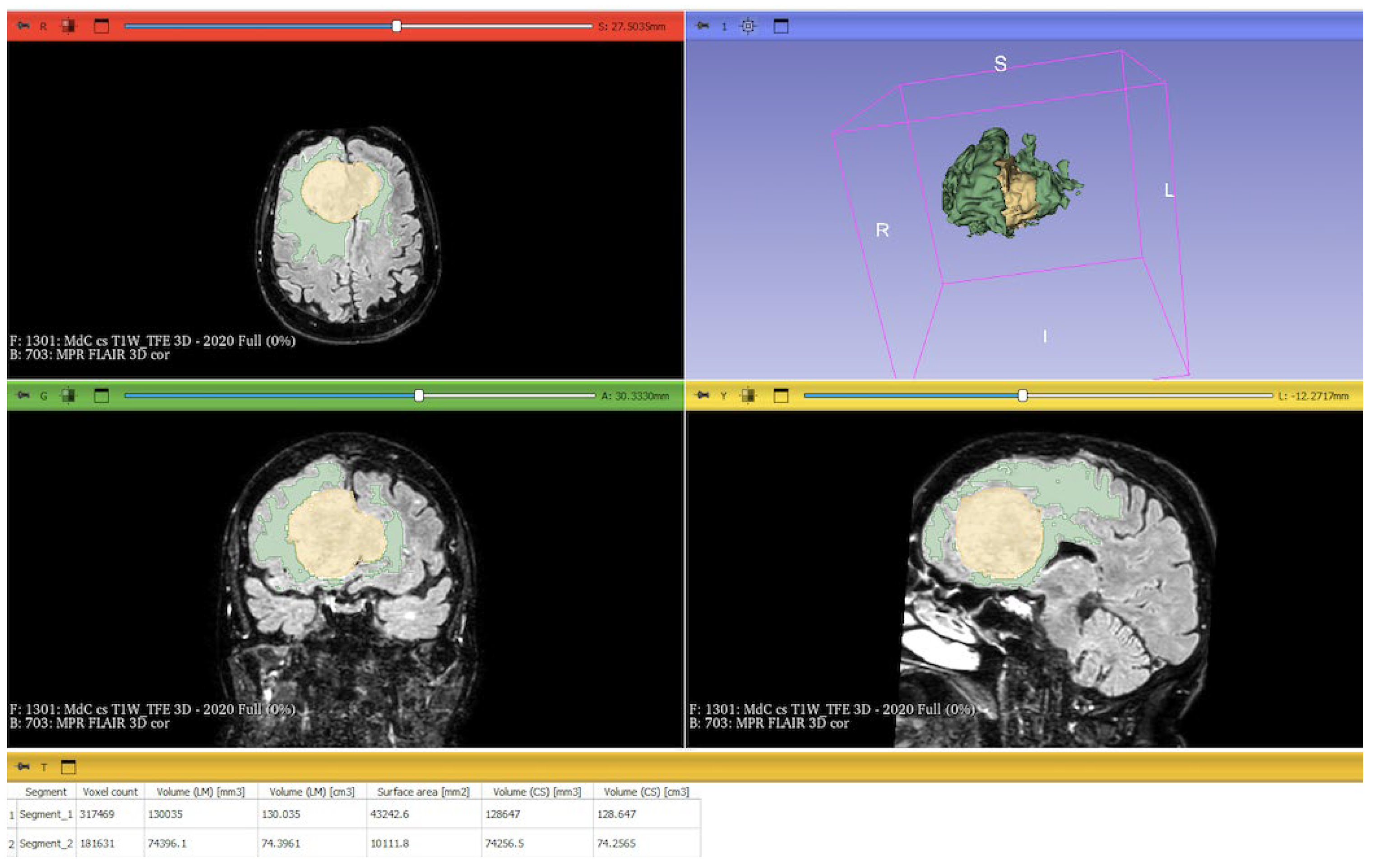

Figure 2B, 2C, 2F, 2G). The final segmentation provides volumetric measurements for both the tumor and the PE, aiding in quantitative analysis (

Figure 3). The included patients' pre- and post-treatment clinical data were retrospectively extracted from our Center's computerized database. Collected data included demographic information, preoperative clinical details (presence or absence of epilepsy, onset symptoms, ASM therapy and number of ASMs taken, radiological characteristics of the meningioma), and postoperative data (Engel class [10], persistence or discontinuation of ASMs, ASM discontinuation timing, and possible postoperative functional deficits). A single examiner conducted data collection to minimize subjective variability in assessments. Surgical procedures were performed using a transcranial approach under general anesthesia. We excluded cases of surgical resection performed via an endoscopic endonasal approach. Cases of postoperative death (within one year after surgery) were excluded. Cases of WHO grade III meningiomas were excluded. The extent of resection (EOR) was determined based on the postoperative MRI (usually one month after surgery) and classified according to the Simpson grading system [22]. The study included cases of complete macroscopic meningioma resection (Simpson I-II-III). Cases with residual tumor persistence or recurrence after surgery (Simpson IV-V) were excluded (

Figure 4). Measurement quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We analyzed qualitative variables by summarizing them as frequencies and percentages, and relationships between variables were assessed using Fisher's exact test and the Chi-square test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or "N-1" Chi-squared test was used to assess statistical differences between the two groups or percentages. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ORs and RRs were calculated to assess the statistical significance of associations. ORs were used to measure the strength of association between categorical variables, while RRs were calculated to estimate the risk of an event in one group compared to another. These methods were chosen to assess the significance of relationships between the analyzed variables accurately.

To evaluate which independent variables (meningioma volume, PE volume, the ratio between meningioma and PE volume, and the presence of preoperative epilepsy) influenced the dependent variable (seizure outcome), we performed a binomial logistic regression, which required converting continuous variables into binary values. For PE volume, values < 1 cm³ were coded as 0 (

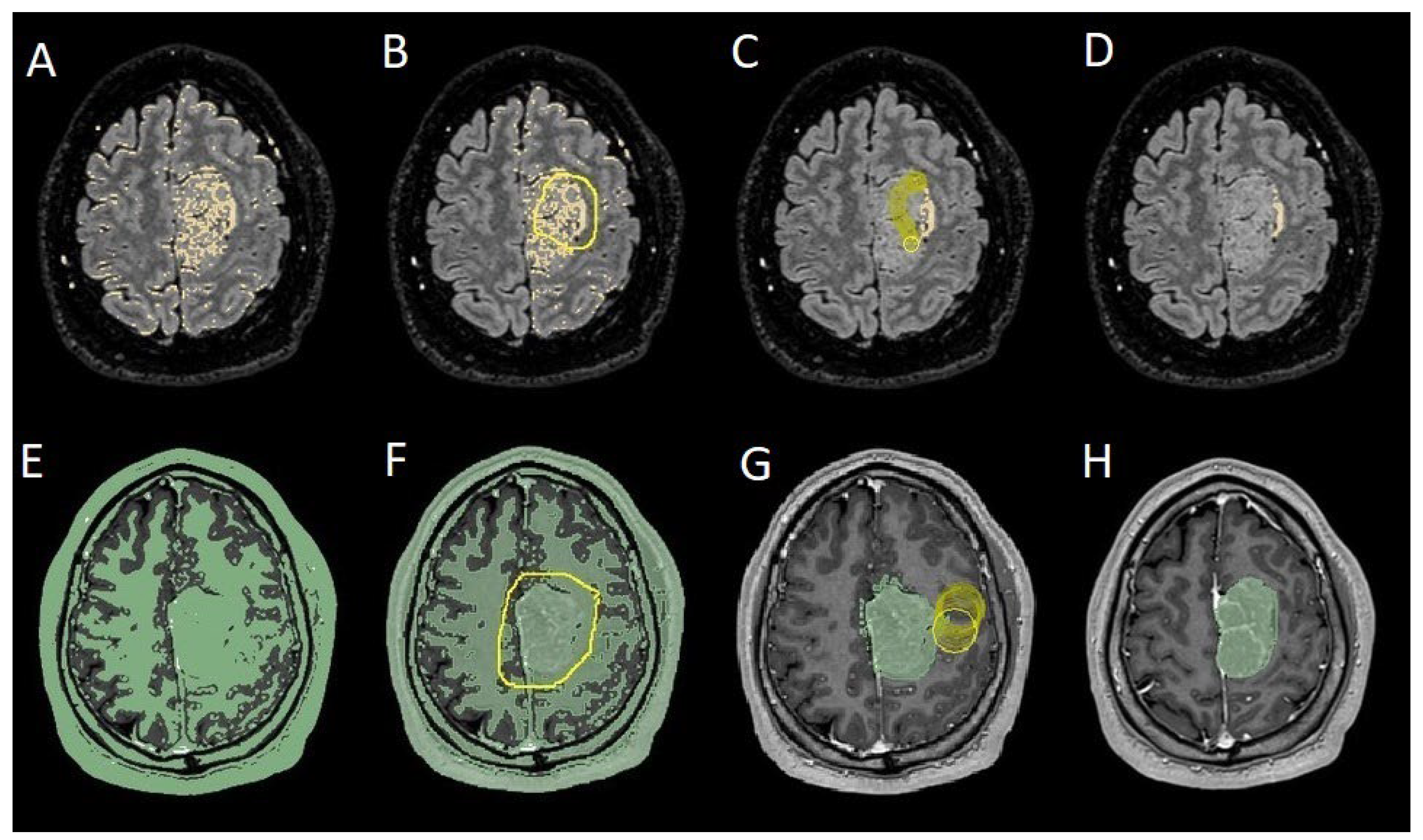

Figure 4), and values ≥ 1 cm³ as 1 (

Figure 5). The cut-off was set at 3 cm³ for tumore volume, and for the volume ratio, the cut-off was 1. The absence of preoperative epilepsy was coded as 0, while its presence was coded as 1. Regarding seizure outcome, Engel IA cases were coded as 0, and cases classified as Engel >IA were coded as 1.

We assessed the factors influencing the discontinuation of ASMs in the postoperative period using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) for whom we had available follow-up data of at least 24 months. We considered 'ID patient' as a subject variable and 'timing' (i.e., the status of ASM therapy at the 12-month and 24-month follow-up time points) as a within-subject variable. Using an exchangeable correlation structure, we included the Engel class, timing of follow-up, PE, and the interaction between the Engel class and the follow-up timing as a covariate.

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Software (IBM Corp. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

3. Results

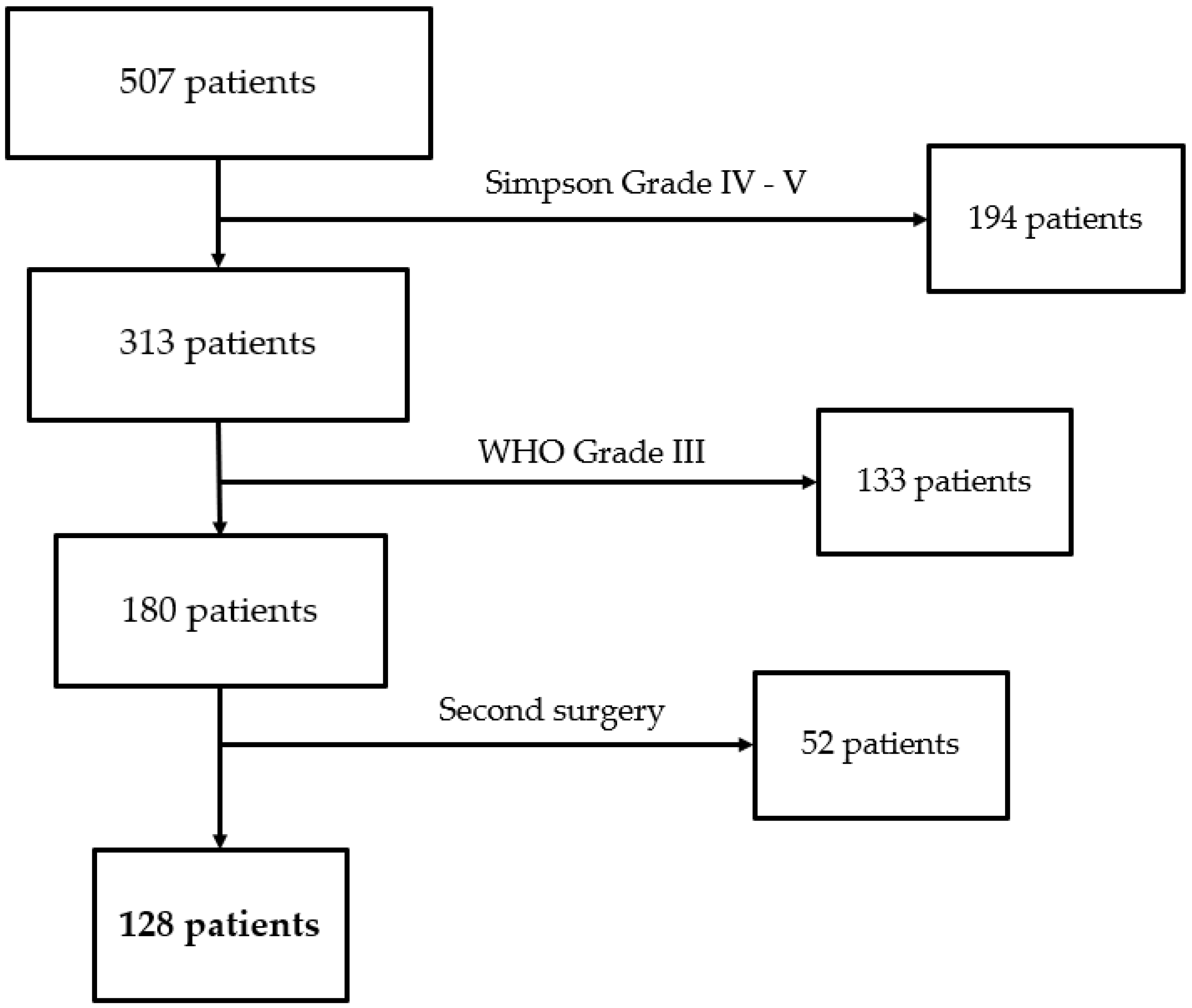

We collected 507 patients at our Center between January 2020 and December 2022. We excluded 194 patients because of Simpson Grade of IV-V, 133 because of WHO Grade III, and 52 because of postsurgical residual. We then included 128 patients in the study who underwent surgical resection (

Figure 6). The demographic characteristics of the population are reported in

Table 1.

1ASMs: AntiSeizure Medications; PE: Peritumoral Edema.

All meningiomas included were naïve. The Simpson Grade I-II was achieved in 110 patients (85.9%) and Grade III-IV in 18 patients (14.1%). The mean follow-up period was 30.1 ± 19.8 months. We included 43 males (33.6%) and 85 females (66.4%), with a mean age of 64 years and a median of 65 years. Preoperative epilepsy was recorded in 53 cases (41.4%). During clinical follow-up, Engel IA was observed in 103 patients (80.4%). The ASM therapy was kept in 39 out of 103 of the patients with Engel IA (37.8%) and 19 out of 25 of the patients with Engel > IA (76%). Among patients on ASM therapy preoperatively who were classified as Engel IA postoperatively (39 patients), 14 discontinued ASM during follow-up (35.9%).

ASM therapy was ongoing preoperatively in 58 cases (45.3%). At 12 months of follow-up, ASM therapy was maintained in 59 patients (46.1%). At 24 months of follow-up, ASM therapy was maintained in 38 patients (29.7%). A meningioma volume greater than 3 cm² was observed in 122 cases (95.3%), and the presence of PE was recorded in 85 cases (66.4%), while a volume ratio greater than one was observed in 51 cases (39.8%).

3.1. Binomial Logistic Regression

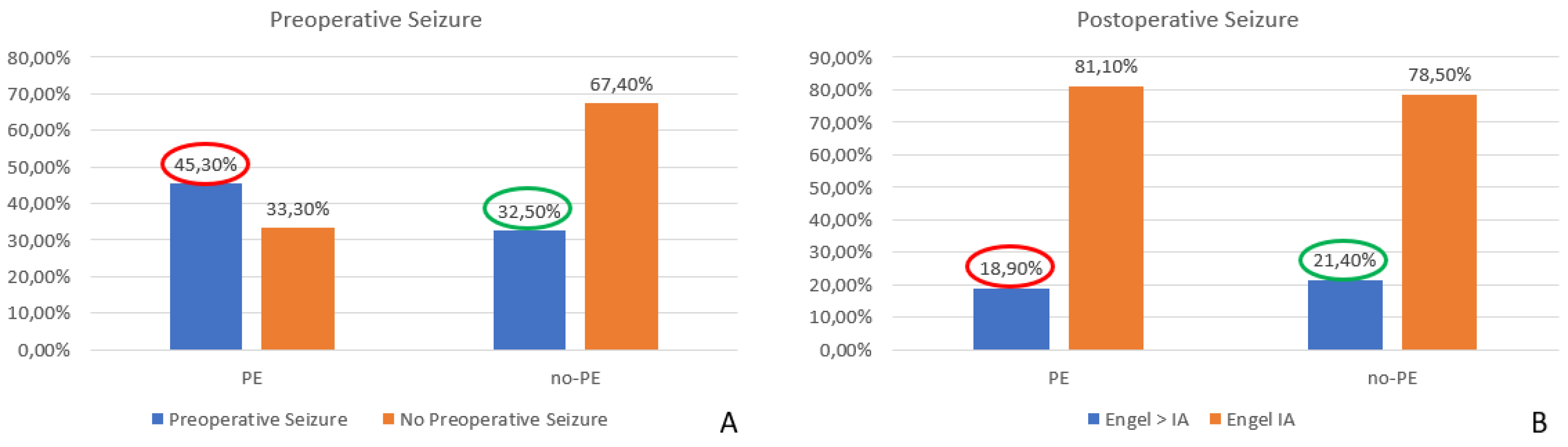

A binomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the independent variables associated with developing postoperative epilepsy. Among the variables analyzed, the only factor that showed a statistically significant association with postoperative epilepsy was the presence of preoperative epilepsy (OR = 2.88, 95% CI: 0.86–5.05; p = 0.016), indicating that patients with epilepsy before surgery had a higher likelihood of experiencing seizures after the procedure. In contrast, other potential predictors, including meningioma volume, PE volume, and volume ratio, did not demonstrate a statistically significant correlation with postoperative epilepsy. These findings suggest that while tumor-related volumetric factors were not significant predictors in this cohort, preoperative epilepsy remains a key determinant of postoperative seizure occurrence (

Figure 7).

3.2. Comparison of Proportion

When considering the overall impact of surgery on MRE, we found a significant decrease in seizure occurrence, with rates dropping from 41.4% before surgery to 19.5% postoperatively (p = 0.0001). These results highlight the potential curative effect of surgical resection in patients with MRE. Furthermore, we observed a statistically significant reduction in the seizure rate among patients with preoperative PE, decreasing from 45.3% before surgery to 18.9% postoperatively (p = 0.0002). This finding suggests that surgical intervention substantially impacted seizure control in this subgroup. Conversely, in cases without PE, although a reduction in seizure frequency was also observed (from 32.5% preoperatively to 21.4% postoperatively), this change did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.24), indicating that factors other than PE might influence seizure persistence in this cohort (

Figure 8).

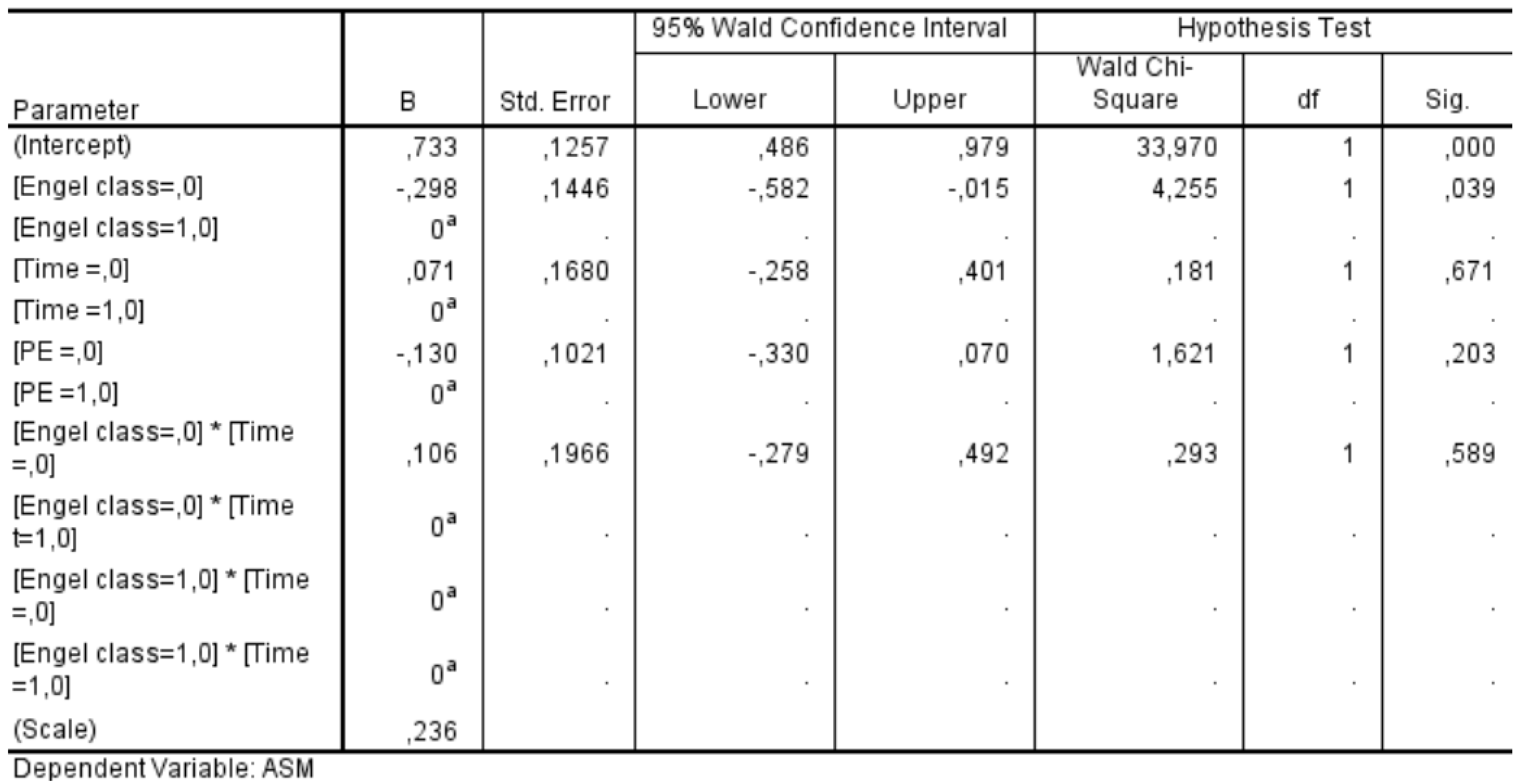

3.3. Generalized Estimating Equations

We conducted a GEE analysis in a subgroup of 59 patients who had completed a 24-month follow-up period. This analysis allowed us to assess the influence of various factors on the likelihood of discontinuing ASMs after surgery. The statistical significance values obtained for each factor were as follows: Engel class demonstrated a significant association with ASM discontinuation (p = 0.039), whereas neither the timing of follow-up (p = 0.671) nor the presence of PE (p = 0.203) showed a statistically significant effect. Additionally, the interaction between Engel class and follow-up timing was insignificant (p = 0.589) (

Figure 9). These findings indicate that Engel classification—a well-established measure of postoperative seizure outcomes—was the only independent factor significantly influencing the decision to discontinue ASMs in the postoperative period. In contrast, the timing of follow-up evaluations and the presence of PE did not play a decisive role in determining whether patients were taken off ASM therapy. This underscores the importance of seizure outcomes in guiding postoperative management strategies for epilepsy patients.

4. Discussion

Our study shows how the presence of PE is the only predictive factor for optimal seizure outcome of the surgical resection of naïve supratentorial meningiomas and how its presence on preoperative MRI can be considered a factor in favor of ASM postsurgical discontinuation in the absence of seizures.

The MRE is a widely studied topic in the literature, with the primary objective being the identification of risk factors for both preoperative and postoperative epilepsy. Despite many studies, only a few risk factors are commonly accepted as associated with MRE. In particular, preoperative epilepsy appears to be correlated with the presence of PE [5,25], while the only commonly accepted risk factor for postoperative epilepsy is the presence of seizures in the preoperative phase. A recent meta-analysis by Tanti et al. [24] reviewed more than 50 papers on supratentorial meningiomas and confirmed that PE is associated with an increased risk of preoperative epilepsy. Additionally, this meta-analysis suggested that PE might also be linked to a slight increase in the risk of both early and late postoperative epilepsy. However, the authors themselves acknowledged that PE does not appear to be the primary risk factor for postoperative seizures. Also, another recent meta-analysis confirms that PE is a predictive factor for postoperative late seizures [13]. These findings contradict our results, indicating that PE is a predictive factor for better seizure outcomes through surgical resection. The reasons behind the differing results can be attributed to several factors. First and foremost, both cited meta-analyses do not focus on the Simpson Grade achieved or the WHO Grade of the included studies. Postoperative epilepsy can be caused by residual tumor tissue or recurrence, introducing a bias in the assessment. In our case series, more than 85% of patients underwent resection with Simpson Grade I-II, and the last 14.9% underwent Simpson Grade III, then no macroscopic residual tumors were present postoperative. Additionally, all the WHO Grade III and recurrence cases during the follow-up were excluded from our study. Consequently, postoperative epilepsy is attributable to factors independent of tumor residue/recurrence, thereby eliminating this evaluation bias. As a result, according to our binomial logistic regression, PE is not a risk factor for an Engel > IA outcome, meaning it is not associated with postoperative epilepsy. Another key difference between our study and previous ones lies in the approach to analysis. Having ruled out PE as a direct risk factor for postoperative epilepsy, we assessed whether its presence could influence the effectiveness of surgery in seizure control. Our findings indicate that, in the presence of PE, surgery is more effective in controlling postoperative epilepsy, and it is the first piece of evidence in the literature to our knowledge. Therefore, according to our analysis, the presence of PE is confirmed as a risk factor for preoperative epilepsy, but also its resolution is a predictor of excellent seizure outcomes following surgical resection. Surgery effectively resolves the mass effect of the meningioma on the surrounding parenchyma and venous system, leading to a reduction in PE itself [2,15,29]. If the presence of PE correlates with epilepsy and its resolution through surgery appears to favor a better seizure outcome compared to cases of surgical resection without PE, this raises the question of PE's role in the epileptogenesis of MRE. There are few studies on this topic, and ours is the first that underlines the role of surgical PE resolution in controlling the seizure. However, our analysis shows that PE appears to be a significant factor that may play a key role in MRE epileptogenesis. Our results have two main implications: resolving PE is the key to treating the most common forms of MRE; secondly, when dealing with meningioma patients with PE, we must remember that resective surgery directly impacts PE resolution and, consequently seizure freedom.

Currently, ASMs in patients with meningioma are indicated only in cases where epileptic seizures occurred before surgery [26]. There are no recommendations for their use as prophylaxis in the absence of epileptic seizures. The ASMs are often associated with side effects such as drowsiness, psychomotor slowing, and potentially severe drug interactions [1,23,30]. Consequently, chronic ASM therapy significantly reduces patients' quality of life and should be avoided in unnecessary cases. However, even if the indication when starting ASM in MRE is reported, the evidence of the proper timing of ASM discontinuation after surgery is less clear. The fear of seizures and the absence of evidence has led neurosurgeons over the years to maintain the ASMs for excessively long periods or even never discontinue in patients Engel class IA [11,16], and our clinical experience reflects this approach. In our surgical series, the decision to discontinue ASM was based on the clinical seizure outcome rather than the duration of follow-up or preoperative PE presence. According to our study's retrospective nature, we described our Center's past approach and reported an ASM maintenance rate of 37.8% in Engel IA cases. This rate is consistent with those reported in the literature [8], showing that more than one-third of seizure-free patients remain on ASM therapy. The recent literature trend of identifying preoperative risk factors for the persistence of postoperative epilepsy is aimed at preemptively determining who is the best candidate for postoperative discontinuation of the ASM therapy, avoiding overtreatment [17].

The risk factors investigated in the development of postoperative epilepsy are numerous, and certain ones have been more consistently reported in the literature as being significantly associated with seizure persistence after surgery. Among these, factors such as the convexity location of the meningioma, involvement of the Rolandic regions, younger patient age, and larger meningioma volumes have been identified as relevant [3,19]. Despite the broad range of risk factors explored in different studies, most of those identified tend to be intrinsic characteristics of the meningioma or the patient, which, interestingly, do not necessarily appear to be directly related to the underlying mechanisms of MRE. Our study results indicate that PE is a suggestive factor for seizure resolution in the postoperative period, highlighting a potentially favorable prognostic implication for patients undergoing surgery and suggesting a potential role of PE in the epileptogenesis of MRE. This finding is particularly relevant in clinical decision-making, as it provides a reassuring element when considering discontinuing ASM after surgery. Given that there are currently no well-defined guidelines or standardized protocols governing ASM withdrawal in this context, recognizing PE as a potentially favorable factor may offer additional confidence to clinicians in guiding postoperative management strategies. Although our findings represent a mere statistical correlation, and further studies are needed to explore the potential role of PE in the epileptogenesis of MRE, this result holds clinical significance. In patients with a history of epilepsy who remain seizure-free in the postoperative period, the presence of PE on preoperative MRI could become a key factor in deciding whether to initiate the decalage of ASM therapy. Regarding the timing of decalage, it is reasonable to hypothesize that it could coincide with the first postoperative MRI at follow-up, in which PE is no longer detected. While further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis, the correlation between PE's presence or absence and seizures' occurrence or resolution could serve as a valuable clinical indicator for determining the optimal timing for ASM decalage and eventual discontinuation in the postoperative setting.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights how PE is associated with a higher risk of preoperative MRE and how it can predict an excellent seizure outcome following the surgical resection of supratentorial meningiomas. The presence of preoperative PE should be considered a favorable factor for discontinuing ASM postoperatively in the absence of seizures. According to our results, the surgery directly impacts MRE and ASM discontinuation in the presence of preoperative PE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., and G.C.; methodology, F.B.; software, G.C.; validation, all authors.; formal analysis, F.B.; investigation, G.C.; resources, G.C.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B.; writing—review and editing, F.B.; supervision, A.DP.; project administration, F.B. and G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective nature.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRE |

Meningioma Related Epilepsy |

| PE |

Peritumoral Edema |

| ASM |

AntiSeizure Medication |

| FLAIR |

Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery |

References

- Barnard SN, Chen Z, Kanner AM, Holmes MG, Klein P, Abou-Khalil BW, Gidal BE, French J, Perucca P (2024) The Adverse Effects of Commonly Prescribed Antiseizure Medications in Adults With Newly Diagnosed Focal Epilepsy. Neurology 103:e209821. [CrossRef]

- Bitzer M, Topka H, Morgalla M, Friese S, Wöckel L, Voigt K (1998) Tumor-related venous obstruction and development of peritumoral brain edema in meningiomas. Neurosurgery 42:730-737. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovic I, Ristic A, Ilic R, Bascarevic V, Bukumiric Z, Miljkovic A, Milisavljevic F, Stepanovic A, Lazic I, Grujicic D (2023) Factors associated with preoperative and early and late postoperative seizures in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Epileptic disorders : international epilepsy journal with videotape 25:244-254. [CrossRef]

- Brokinkel B, Hinrichs FL, Schipmann S, Grauer O, Sporns PB, Adeli A, Brokinkel C, Hess K, Paulus W, Stummer W, Spille DC (2021) Predicting postoperative seizure development in meningiomas - Analyses of clinical, histological and radiological risk factors. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 200:106315. [CrossRef]

- Chen WC, Magill ST, Englot DJ, Baal JD, Wagle S, Rick JW, McDermott MW (2017) Factors Associated With Pre- and Postoperative Seizures in 1033 Patients Undergoing Supratentorial Meningioma Resection. Neurosurgery 81:297-306. [CrossRef]

- Cramer JA, Mintzer S, Wheless J, Mattson RH (2010) Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs: a brief overview of important issues. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 10:885-891. [CrossRef]

- Ellingson BM, Bendszus M, Boxerman J, Barboriak D, Erickson BJ, Smits M, Nelson SJ, Gerstner E, Alexander B, Goldmacher G, Wick W, Vogelbaum M, Weller M, Galanis E, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Shankar L, Jacobs P, Pope WB, Yang D, Chung C, Knopp MV, Cha S, van den Bent MJ, Chang S, Yung WK, Cloughesy TF, Wen PY, Gilbert MR (2015) Consensus recommendations for a standardized Brain Tumor Imaging Protocol in clinical trials. Neuro-oncology 17:1188-1198. [CrossRef]

- Ellis EM, Drumm MR, Rai S, Huang J, Tate MC, Magill ST, Templer JW (2024) Patterns of Antiseizure Medication Use Following Meningioma Resection: A Single-Institution Experience. World neurosurgery 181:e392-e398. [CrossRef]

- Ellis EM, Drumm MR, Rai SM, Huang J, Tate MC, Magill ST, Templer JW (2023) Long-term antiseizure medication use in patients after meningioma resection: identifying predictors for successful weaning and failures. Journal of neuro-oncology 165:201-207. [CrossRef]

- Engel J, Jr. (1993) Update on surgical treatment of the epilepsies. Summary of the Second International Palm Desert Conference on the Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies (1992). Neurology 43:1612-1617. [CrossRef]

- Englot DJ, Magill ST, Han SJ, Chang EF, Berger MS, McDermott MW (2016) Seizures in supratentorial meningioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of neurosurgery 124:1552-1561. [CrossRef]

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S, Bauer C, Jennings D, Fennessy F, Sonka M, Buatti J, Aylward S, Miller JV, Pieper S, Kikinis R (2012) 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magnetic resonance imaging 30:1323-1341. [CrossRef]

- Ghazou A, Yassin A, Aljabali AS, Al-Zamer YS, Alawajneh M, Al-Akhras A, AlBarakat MM, Tashtoush S, Shammout O, Al-Horani SS, Jarrah EE, Ababneh O, Jaradat A (2024) Predictors of early and late postoperative seizures in meningioma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgical review 47:242. [CrossRef]

- Hwang K, Joo JD, Kim YH, Han JH, Oh CW, Yun CH, Park SH, Kim CY (2019) Risk factors for preoperative and late postoperative seizures in primary supratentorial meningiomas. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 180:34-39. [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Moon KS, Jung JH, Jang WY, Jung TY, Kim IY, Lee KH, Jung S (2020) Importance of collateral venous circulation on indocyanine green videoangiography in intracranial meningioma resection: direct evidence for venous compression theory in peritumoral edema formation. Journal of neurosurgery 132:1715-1723. [CrossRef]

- Komotar RJ, Raper DM, Starke RM, Iorgulescu JB, Gutin PH (2011) Prophylactic antiepileptic drug therapy in patients undergoing supratentorial meningioma resection: a systematic analysis of efficacy. Journal of neurosurgery 115:483-490. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Wang C, Lin Z, Zhao M, Ren X, Zhang X, Jiang Z (2020) Risk factors and control of seizures in 778 Chinese patients undergoing initial resection of supratentorial meningiomas. Neurosurgical review 43:597-608. [CrossRef]

- Maschio M, Aguglia U, Avanzini G, Banfi P, Buttinelli C, Capovilla G, Casazza MML, Colicchio G, Coppola A, Costa C, Dainese F, Daniele O, De Simone R, Eoli M, Gasparini S, Giallonardo AT, La Neve A, Maialetti A, Mecarelli O, Melis M, Michelucci R, Paladin F, Pauletto G, Piccioli M, Quadri S, Ranzato F, Rossi R, Salmaggi A, Terenzi R, Tisei P, Villani F, Vitali P, Vivalda LC, Zaccara G, Zarabla A, Beghi E, On behalf of Brain Tumor-related Epilepsy study group of Italian League Against E (2019) Management of epilepsy in brain tumors. Neurological Sciences 40:2217-2234. [CrossRef]

- McKevitt C, Marenco-Hillembrand L, Bamimore M, Chandler R, Otamendi-Lopez A, Almeida JP, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Chaichana KL (2023) Predictive factors for post operative seizures following meningioma resection in patients without preoperative seizures: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Acta neurochirurgica 165:1333-1343. [CrossRef]

- Rudà R, Trevisan E, Soffietti R (2010) Epilepsy and brain tumors. Current opinion in oncology 22:611-620. [CrossRef]

- Seyedi JF, Pedersen CB, Poulsen FR (2018) Risk of seizures before and after neurosurgical treatment of intracranial meningiomas. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 165:60-66. [CrossRef]

- Simpson D (1957) The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 20:22-39. [CrossRef]

- Strzelczyk A, Schubert-Bast S (2022) Psychobehavioural and Cognitive Adverse Events of Anti-Seizure Medications for the Treatment of Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathies. CNS drugs 36:1079-1111. [CrossRef]

- Tanti MJ, Nevitt S, Yeo M, Bolton W, Chumas P, Mathew R, Maguire MJ (2025) Oedema as a prognostic factor for seizures in meningioma - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgical review 48:249. [CrossRef]

- Teske N, Teske NC, Greve T, Karschnia P, Kirchleitner SV, Harter PN, Forbrig R, Tonn JC, Schichor C, Biczok A (2024) Perifocal edema is a risk factor for preoperative seizures in patients with meningioma WHO grade 2 and 3. Acta neurochirurgica 166:170. [CrossRef]

- Walbert T, Harrison RA, Schiff D, Avila EK, Chen M, Kandula P, Lee JW, Le Rhun E, Stevens GHJ, Vogelbaum MA, Wick W, Weller M, Wen PY, Gerstner ER (2021) SNO and EANO practice guideline update: Anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Neuro-oncology 23:1835-1844. [CrossRef]

- Xue H, Sveinsson O, Bartek J, Jr., Förander P, Skyrman S, Kihlström L, Shafiei R, Mathiesen T, Tomson T (2018) Long-term control and predictors of seizures in intracranial meningioma surgery: a population-based study. Acta neurochirurgica 160:589-596. [CrossRef]

- Xue H, Sveinsson O, Tomson T, Mathiesen T (2015) Intracranial meningiomas and seizures: a review of the literature. Acta neurochirurgica 157:1541-1548. [CrossRef]

- Yamano A, Matsuda M, Kohzuki H, Ishikawa E (2024) Impact of superficial middle cerebral vein compression on peritumoral brain edema of the sphenoid wing meningioma. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 246:108575. [CrossRef]

- Zelano J, Nika O, Asztely F, Larsson D, Andersson K, Andrén K (2023) Prevalence and nature of patient-reported antiseizure medication side effects in a Swedish regional multi-center study. Seizure 113:23-27. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Sequences selected for the segmentation: (A, B, C) coronal, sagittal, axial FLAIR sequences to quantify PE; (D, E, F) coronal, sagittal, axial T1-weighted with contrast enhancement to estimate meningioma volume. FLAIR: Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery; PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 1.

Sequences selected for the segmentation: (A, B, C) coronal, sagittal, axial FLAIR sequences to quantify PE; (D, E, F) coronal, sagittal, axial T1-weighted with contrast enhancement to estimate meningioma volume. FLAIR: Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery; PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 2.

Example of segmentation process with Slices website: A, E: automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values, respectively, for the PE on FLAIR sequence and the meningioma on T1-weighted with gadolinium sequence; B, F: partially automatic erase of redundant signal with "erase outside" tool; C, G: definition of boundaries of edema and tumor through manual erasement; D, H: final segmented volumes. FLARI: Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery, PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 2.

Example of segmentation process with Slices website: A, E: automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values, respectively, for the PE on FLAIR sequence and the meningioma on T1-weighted with gadolinium sequence; B, F: partially automatic erase of redundant signal with "erase outside" tool; C, G: definition of boundaries of edema and tumor through manual erasement; D, H: final segmented volumes. FLARI: Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery, PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of 3D Slicer showing the completed segmentation of the meningioma and PE, with 3D reconstruction and statistical quantification: the segmented PE is shown in green; the segmented meningioma is shown in yellow; at the bottom, the statistical quantification of the segment volumes is displayed; the MRIs include a T1-weighted, and a FLAIR scan merged at 50%. PE: peritumoral edema; MRI: magnetic resonance image; FLARI: Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of 3D Slicer showing the completed segmentation of the meningioma and PE, with 3D reconstruction and statistical quantification: the segmented PE is shown in green; the segmented meningioma is shown in yellow; at the bottom, the statistical quantification of the segment volumes is displayed; the MRIs include a T1-weighted, and a FLAIR scan merged at 50%. PE: peritumoral edema; MRI: magnetic resonance image; FLARI: Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery.

Figure 4.

Segmentation process for PE < 1 cm3: A, E: automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values, respectively, for the PE and the meningioma; B, F: partially automatic erase of redundant signal with "erase outside" tool; C: precisely definition of boundaries of edema through manual erasement, cutting all around redundant signal; G: manual erasing boundaries for tumor volume; D, H: final segmented volumes. PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 4.

Segmentation process for PE < 1 cm3: A, E: automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values, respectively, for the PE and the meningioma; B, F: partially automatic erase of redundant signal with "erase outside" tool; C: precisely definition of boundaries of edema through manual erasement, cutting all around redundant signal; G: manual erasing boundaries for tumor volume; D, H: final segmented volumes. PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 5.

Segmentation process for PE > 1 cm3: A, E: automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values, respectively, for the PE and the meningioma; B, F: partially automatic erase of redundant signal with "erase outside" tool; C: precisely definition of boundaries of edema through manual erasement, cutting all around redundant signal inside the tumor; G: manual erasing boundaries for tumor volume; D, H: final segmented volumes. PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 5.

Segmentation process for PE > 1 cm3: A, E: automatic thresholding technique to identify initial regions of interest based on intensity values, respectively, for the PE and the meningioma; B, F: partially automatic erase of redundant signal with "erase outside" tool; C: precisely definition of boundaries of edema through manual erasement, cutting all around redundant signal inside the tumor; G: manual erasing boundaries for tumor volume; D, H: final segmented volumes. PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 6.

Patients flow diagram.

Figure 6.

Patients flow diagram.

Figure 7.

Binomial logistic regression in the surgical group: only preoperative seizure significantly correlated to the dependent variable "seizure outcome" with p = 0.016. The other independent variables analyzed (the volume of meningioma, the volume of PE, and the volume ratio) are not statistically correlated to the seizure outcome. PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 8.

Comparison of proportion of the rate of pre-and postoperative seizure in the presence or absence of PE in the surgical group: the surgery significantly decreases the seizure rate in the presence of PE (45.3% vs. 18.5% p = 0.0002) and not without PE (32.5% vs. 21.4% p= 0.24). PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 8.

Comparison of proportion of the rate of pre-and postoperative seizure in the presence or absence of PE in the surgical group: the surgery significantly decreases the seizure rate in the presence of PE (45.3% vs. 18.5% p = 0.0002) and not without PE (32.5% vs. 21.4% p= 0.24). PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 9.

Results of the Generalized Estimating Equations show how the Engel class influences the decision to discontinue or not the ASM in the postoperative period, while the timing and the PE do not. ASM: AntiSeizure Medication; PE: peritumoral edema.

Figure 9.

Results of the Generalized Estimating Equations show how the Engel class influences the decision to discontinue or not the ASM in the postoperative period, while the timing and the PE do not. ASM: AntiSeizure Medication; PE: peritumoral edema.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data.

| Variable |

Details |

Total patients included

Gender

Male

Female

Age at Diagnosis (y)

Mean Age

Median Age

Mean Follow-up (m)

Simpson Grade (Surgical Group)

Grade 1-2

Grade 3

Preoperative Epilepsy

Engel Class IA

Preoperative ASMs

Postoperative ASMs

12 Months Post- Treatment

24 Months Post-treatment

Volumes

Meningioma > 3 cm3

PE

Meningioma/PE > 1 cm3

|

128

43 (33.6%)

85 (66.4%)

64

65

30.1 ± 19.8

110 (85.9%)

18 (14.1%)

53 (41.4%)

103 (80.4%)

58 (45.3%)

59 (46.1%)

38 (29.7%)

122 (95.3%)

85 (66.4%)

51 (39.8%)

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).