4.1. Before México-Tenochtitlan

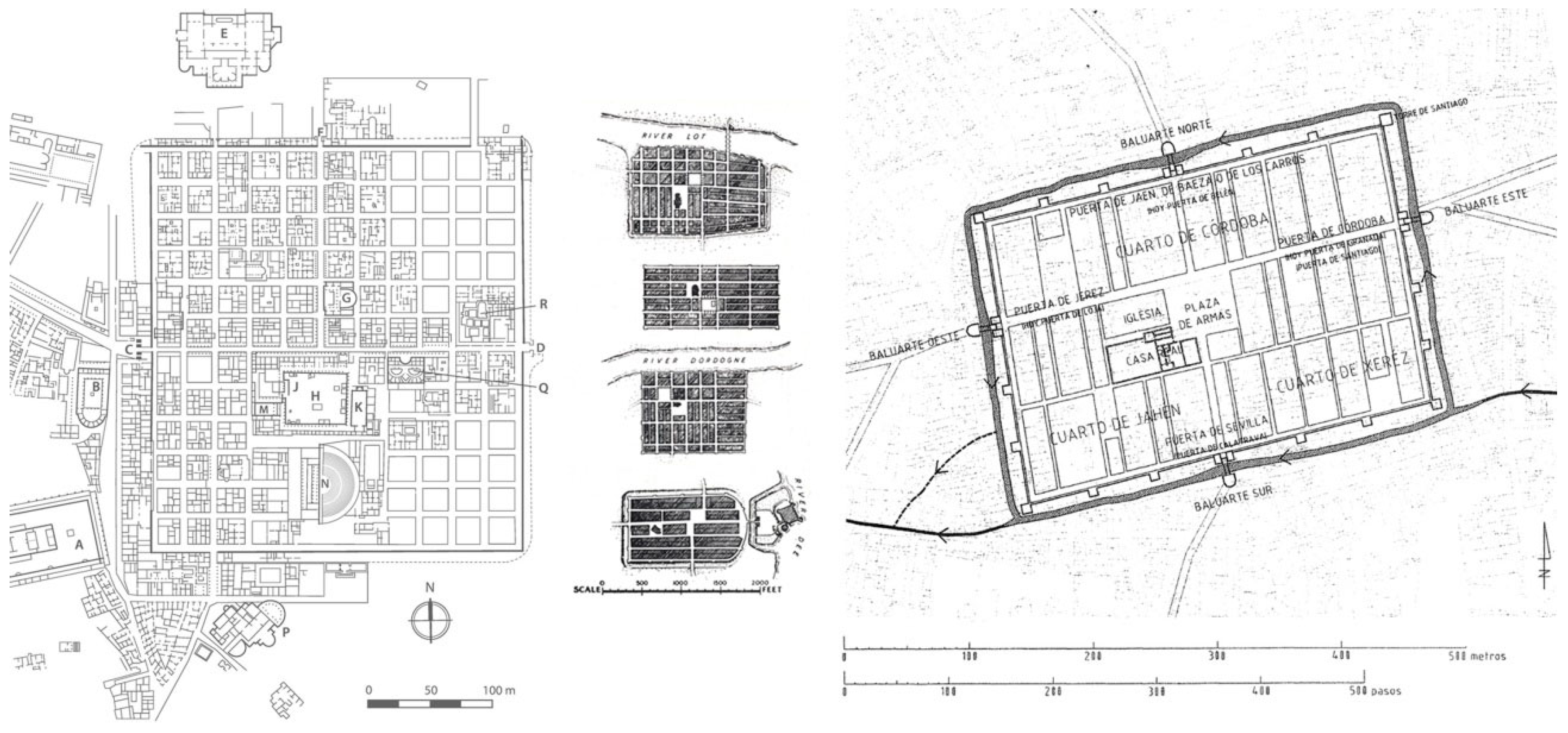

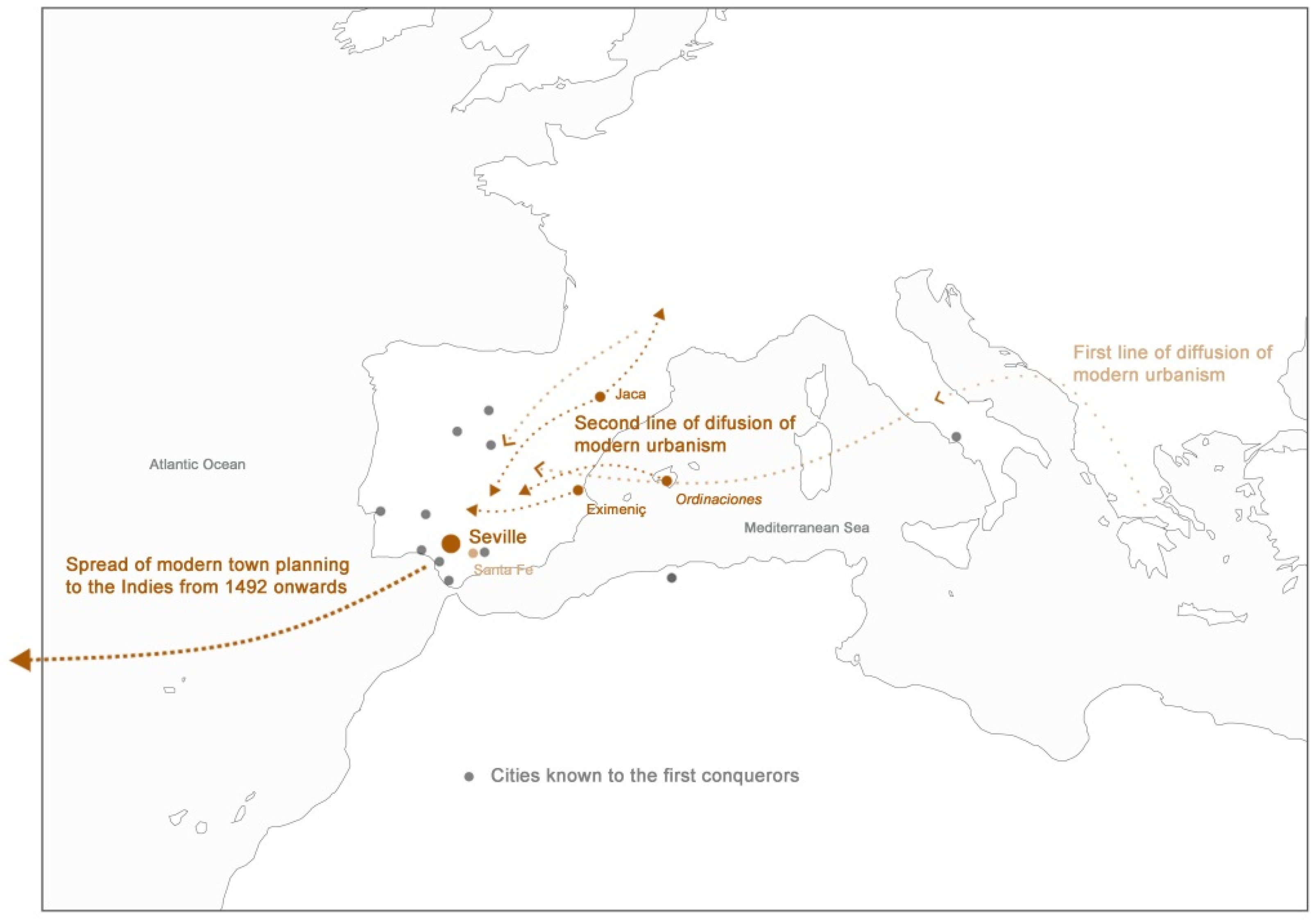

Historically, it has been widely accepted that the origins of modern urbanism, as manifested in the Americas from the 16th century onward, were exclusively a European invention –

first line of diffusion of modern urbanism–. This interpretation is based on the premise that modern urbanism traces back to Western traditions, beginning with Greek civilization and evolving through different stages: from Roman

castrum to the French bastides of the Middle Ages, culminating in the establishment of Santa Fe near Granada in the late 15th century, founded by the Catholic Monarchs (Morris, 2018; Bonet Correa, 1991; Esteras Martín, Diáñez Rubio, & Arvizu García, 1990; Terán, 1989; Gutiérrez, 1984; Hardoy, 1975; Palm, 1951a) (

Figure 2).

However, it is important to highlight that, during the same historical period, various cities in the American continent –completely independent from European traditions– displayed remarkably structured urban layouts. Examples include Teotihuacan in present-day México, which flourished between the 2nd and 7th centuries AD, and the cities of Viracochapampa and Pikillacta in present-day Peru, dating back to the 6th century AD. These cases provide unmistakable evidence that, independent of Western influences, sophisticated urban developments with a high degree of planning existed (

Figure 3).

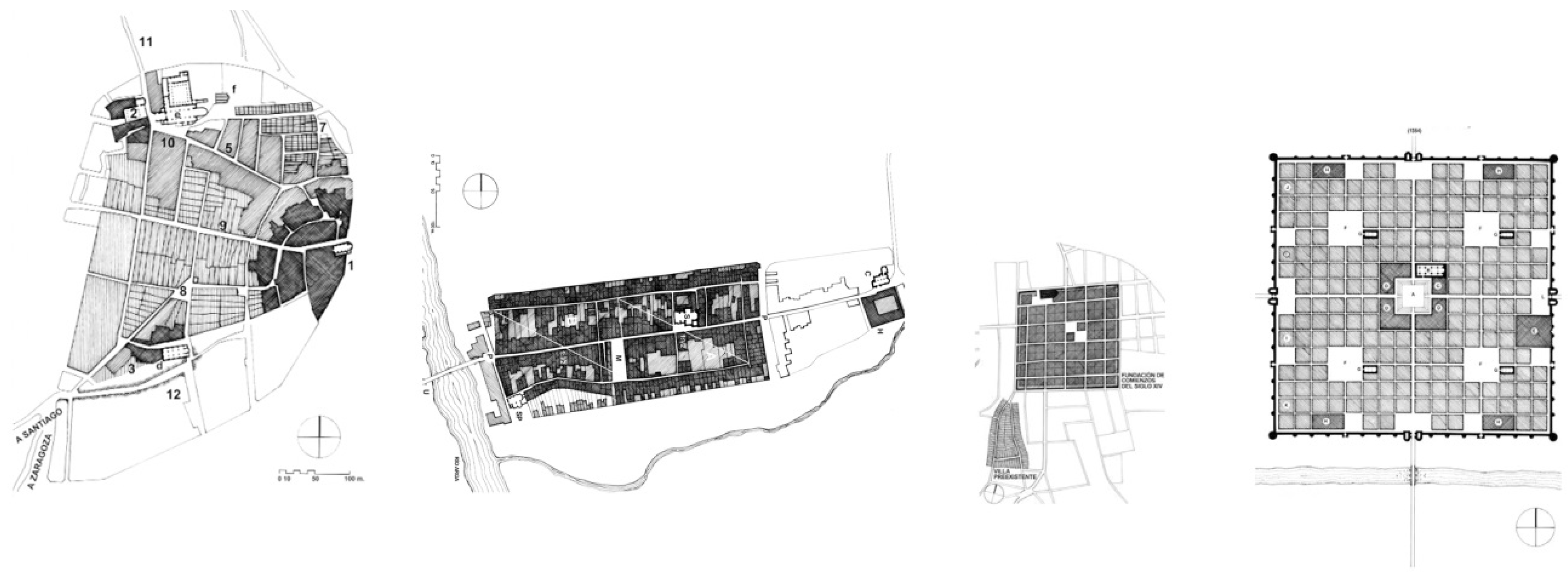

Furthermore, despite the validity of the previously described processes, closer historical precedents to Spain can be found that directly contributed to the invention and dissemination of modern urbanism –second line of diffusion of modern urbanism–. One such example is the implementation of the orthogonal layout, which began in the 11th century in Jaca (a city in northern Spain). This urban initiative was driven by a local charter that promoted equality through the equitable distribution of land plots, encapsulated in the principle ‘equal plots for equal men’. This model influenced the bastides and spread throughout the entire Iberian Peninsula (Bielza de Ory, 2002).

Similarly, within the Crown of Castile, a new urban order emerged during the second half of the 13th century, when Alfonso X the Wise promoted repopulation through the creation of villas and pueblas –also known as polas– with the aim of consolidating royal jurisdiction over regions that had traditionally been under the control of local lords. This process of settlement foundation extended from the northern part of the Peninsula (Galicia, Asturias, and the Basque Country) to the centre and south (Castile and Andalusia). However, at this stage, these new settlements did not yet show a fully defined urban organization (Valdeón Baruque, 2003).

Additionally, the development of a regular urban model materialized later under the monarchs of the Crown of Aragón, particularly under the influence of King James II of Majorca and the

ordinances he issued in the 14th century (Alomar Esteve, 1976). Unlike the traditional orthogonal layout based on rectangular structures, the Aragonese proposals were founded on a grid system, meaning a square-based arrangement for both urban organization and territorial planning. This approach had already been predicted by earlier urban foundations in regions such as Teruel and Castellón in previous centuries, allowing cities to begin adopting a more coherent and structured organization (

Figure 4).

The formalization and dissemination of these models in Aragon did not go unnoticed by contemporary scholars of the time. In the 14th century, the Franciscan monk Francesc Eiximeniç, in Valencia, conceptualized a utopian vision for cities: urban centres organized in a square shape, designed to be both beautiful and orderly, evoking the image of a celestial Jerusalem. This vision can be considered one of the earliest urban theories preceding the Renaissance (Martín Rodríguez, 2004). It was based on the organization of cities through orthogonal axes, where the intersection of these axes divided the urban space into four sectors, reflecting the Gothic-Christian worldview promoted by Thomas Aquinas and the doctrines taught at the University of Paris. At the centre of this design, a square served as the organizational and symbolic core of the city. Although this was a utopian model, it reflects a deep aspiration for a structured and rational urban layout (Cervera Vera, 1989; Antelo Iglesias, 1985; Vila, 1984) (

Figure 5).

4.2. At the Same Time as México-Tenochtitlan in the Iberian Peninsula

Understanding the development of urbanism in the Iberian Peninsula at the dawn of the Early Modern period requires recognizing two fundamental elements inherited from medieval traditions: city walls and churches (Gutiérrez Millán, 2001). These features defined the core of most urban settlements until the introduction of more structured urban layouts in the northeast of the Peninsula in the 11th century.

In a brief period, the consolidation of urban centres led to the creation of spaces and buildings that became key landmarks for future urban growth (Moya-Olmedo & Núñez-González, 2023).

It should also be noted that the conquistadors and those responsible for founding the first cities in the newly gotten American territories were only familiar with urban centres still marked by the medieval characteristics of the Iberian Peninsula, without exposure to the latest urban innovations mentioned earlier. The list of these historical figures is extensive; however, by highlighting a few, this statement can be proved simply by listing the cities they are believed to have known before traveling to the Indies (

Figure 6).

Christopher Columbus visited several Portuguese cities, including Lisbon, and Spanish towns such as Palos de la Frontera, Cádiz, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda (South of Spain).

Nicolás de Ovando, Governor-General of the Indies, was originally from Cáceres (West of Spain) and had ties to the Order of Alcántara in Extremadura, where he served as Grand Commander. He also had connections to the city of Cádiz.

Pedro Arias Dávila, known as Pedrarias Dávila, Governor of Castilla del Oro (mainland), was born in Segovia (centre of Spain), known Granada and Sanlúcar de Barrameda (South of Spain). Also, several Angelian cities.

Diego Velázquez de Cuellar, Governor of the island of Cuba, originally from Cuéllar (near Segovia, centre of Spain), also known Cádiz. Also, a significant city as Naples.

Hernán Cortés, Captain General and Chief Justice of the future New Spain, was born in Medellín (West of Spain) and had contact with cities such as Salamanca, Valladolid (centre of Spain), Valencia (East of Spain), and Granada (South of Spain) (

Figure 7).

In their travels, these figures all passed through Seville, which became the principal gateway to the Americas after the establishment of the Casa de Contratación in 1503. This institution centralized the administration and commerce of the new territories. However, like most Iberian cities of the period, Seville’s urban structure was still shaped by medieval characteristics. The city was organized around its walls and churches, which defined its urban landscape. Buildings were typically narrow-fronted and deep, tightly packed around religious institutions, forming dense neighbourhoods. In peripheral areas or suburbs, constructions were scattered along gates and roads, with open spaces increasing towards the outskirts.

Additionally, Seville’s historical development led to a highly irregular urban fabric, with complex street patterns partly inherited from its Islamic past (Barrios Aguilera, 1995; Moya-Olmedo & Nuñez-González, 2023). The city’s layout cannot be considered modern or remotely orthogonal, as it lacked the geometric planning that would later define Spanish colonial cities (

Figure 8).

4.3. At the Same Time as México-Tenochtitlan in the Indies

The first attempts to set up cities in the New World at the beginning of the 16th century lacked the defining characteristics of modern urbanism. These settlements were temporary and spontaneous, without following the meticulously planned designs that would later define Spanish colonial cities. Their importance lay not in their internal organization but in their strategic role in claiming and populating newly discovered territories for the Crown of Castile. The foundation of these cities was often marked by a ceremonial act and a legal framework transferred from the Iberian Peninsula (Brewer-Carías, 1998) (

Figure 9).

One example is the first settlements founded by Columbus on the Hispaniola Island, which, due to geographical and economic challenges, were eventually abandoned in favour of more strategically helpful locations. The first of these was Fort Navidad (1492-1493), where 39 men were left behind on Columbus’s return voyage to Spain, but which had been destroyed upon his return. La Isabela (1493-1498), also founded on the island, was the first attempt at a permanent colony, but due to various difficulties, it was abandoned within a few years.

Santo Domingo was founded by Columbus’s brother in the south of Hispaniola and became the first permanent city in the new territories and capital of the Viceroyalty of Hispaniola. It can be considered a successful foundation, although only four years later, in 1502, Governor Nicolás de Ovando ordered its transfer. Those who knew it praised the supposed straightness of its streets, laid out in such a way that they seemed to follow a string line; however, a closer analysis reveals that, although the streets were straight, they did not maintain a perfect parallelism, which resulted in a distribution of polygonal blocks of various sizes, next to a main square of equally polygonal and off-centre shape (Lucena Giraldo, 2006). Although this design did not reach the perfection of an orthogonal grid, despite its limitations, the capital of the new territories, at least until the founding of the city of México, was considered by its contemporaries to be superior to many of the peninsular cities, standing out for having level, wide and straight streets. It can be said that, towards the end of the 16th century, a regular layout had materialized that was advanced in comparison with traditional models. Cortés would live in Santo Domingo.

The process of setting up other coastal cities, crucial for securing defense and logistical support during the expansion of the conquest, also marked a milestone in urban evolution. For example, the first significant settlement on the mainland was Santa María la Antigua, founded in 1510 (Quintero Agamez & Sarcina, 2021). This city was partially set up due to the presence of a pre-existing indigenous settlement. However, with the arrival of Pedrarias Dávila in 1514, accompanied by more than a thousand Castilians, an expansion and reorganization process were started according to the directives given by the Crown. By the end of 1515, Pedrarias declared that Santa María was indeed an organized city (Tejeira Davis, 1996). While no graphical representation of its layout has survived, it is plausible to assume that Santa María had a more irregular layout compared to the first foundation of Panama, which had an orthogonal arrangement despite variations in block sizes and street alignments. García Bravo lived in Santa María la Antigua.

Similarly, between late 1510 and early 1511, Velázquez de Cuellar embarked on a journey to Cuba, where he set up a network of urban settlements on the island. In this context, Santiago de Cuba, founded in 1515, was the last of the cities set up in Cuba. The location of Santiago was selected based on criteria such as communication accessibility, the presence of a suitable port, and defensive advantages. However, the site proved unhealthy, leading to its eventual relocation (Gavira Golpe, 1983). Although by the late 17th century it was claimed that its layout followed a grid pattern oriented to cardinal points, evidence suggests that its urban plan was in fact irregular. Cortés served as Mayor of Santiago de Cuba.

Consequently, based on the urban experiences in the New World, it is not valid to conclude that the initiatives known to Cortés in Santo Domingo and Cuba, or to García Bravo in mainland, served as direct models for the layout of the new cities that appeared in the territory later known as New Spain. These settlements were not characterized by orthogonality or systematic planning in the modern sense of urbanism (

Figure 10).

Finally, it is also relevant to mention the first city founded by Cortés, La Villa Rica de la Veracruz. Although the design of the original Veracruz remains unknown, it is documented that in 1524, the city was moved to a more suitable site near San Juan de Ulúa, an island that functioned as a defensive and deep-water port. The first settlement, known as La Antigua, lacked a regular urban design. Although Cortés issued precise instructions about its layout and settlement, including directives for the location of plots and the alignment of streets to ensure their rectilinear arrangement, the result did not achieve the perfection of an ideal grid (

Figure 11).

What did royal instructions state about cities in the New World? In 1513, Charles V issued an instruction directed at Pedrarias, later reiterated in later ordinances, such as the one given to Cortés in 1523. This mandate established:

‘(…) you must distribute the plots of the settlement for the construction of houses (…) and from the beginning, they must be assigned in an orderly manner; so that, once the plots are established, the town appears ordered, both in the space left for the main square and in the placement of the church and the arrangement of the streets. For in places that are newly established, if order is set from the beginning, they remain structured without effort or cost, while in other cases, order is never achieved (…)’ (Cortés, 1981).

This text emphasizes the importance of initiating urbanization in a systematic and planned manner, ensuring that from the very beginning, plots were distributed in an orderly fashion so that the town would show a coherent and aesthetic appearance. This approach aimed not only at construction efficiency but also at symbolically representing a social and administrative order, which needed to be clear from the first structuring of urban space.

Numerous studies have explored in detail the concept of the grid and the notion of an ordered city in the New World, with notable contributions from scholars such as López Guzmán (1997), García Zarza (1996), and Sánchez de Carmona (1989). However, it is important to highlight that, despite the extensive discussions and analyses about the implementation of these urban directives, when Cortés arrived in the Americas in 1519, he unexpectedly met an already ordered city layout.

Later, in 1573, Philip II signed another important ordinance reflecting the evolution of urban foundation and planning processes. This document emphasized the need to design the planta or basic layout of settlements in a way that precisely and uniformly organized squares, streets, plots, and even temples. It clearly looked to reconcile urban expansion with the preservation of pre-established order. However, as noted by Terán, since this law was issued when most major cities in the New World had already been founded –and because none of them truly adhered to the proposed model– it stands as a clear example of legislation that was never fully implemented (Terán, 1999).

In conclusion, the royal directives reflected a clear intention to set up cities with an ordered and coherent layout based on geometric and functional principles. However, the case of México-Tenochtitlan adds a new dimension to this discussion, proving that urban order in the New World had its own roots and manifestations. This raises interesting questions about the interaction between European traditions and pre-Hispanic realities in shaping urbanism in the newly conquered territories.

4.4. After México-Tenochtitlan

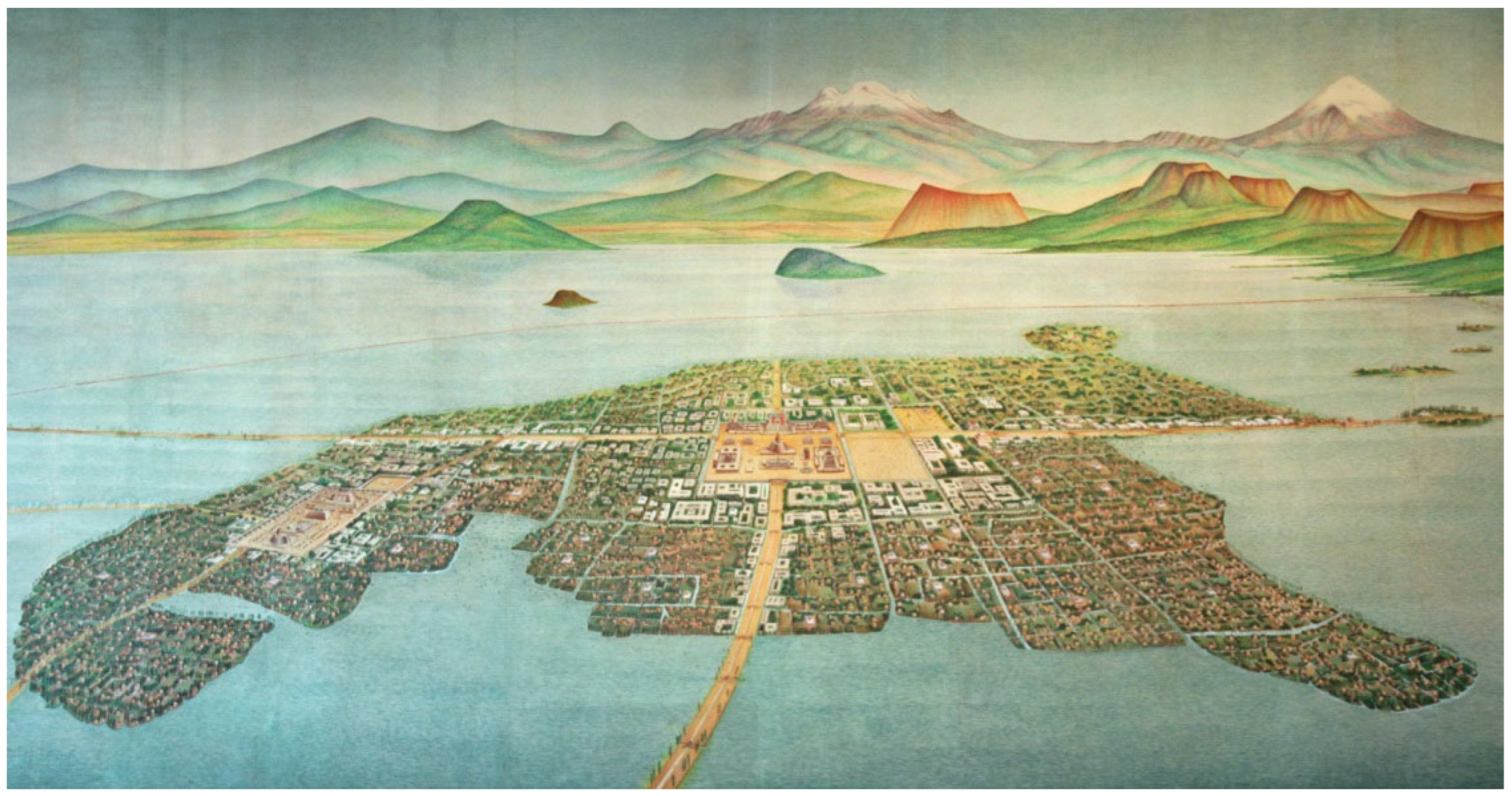

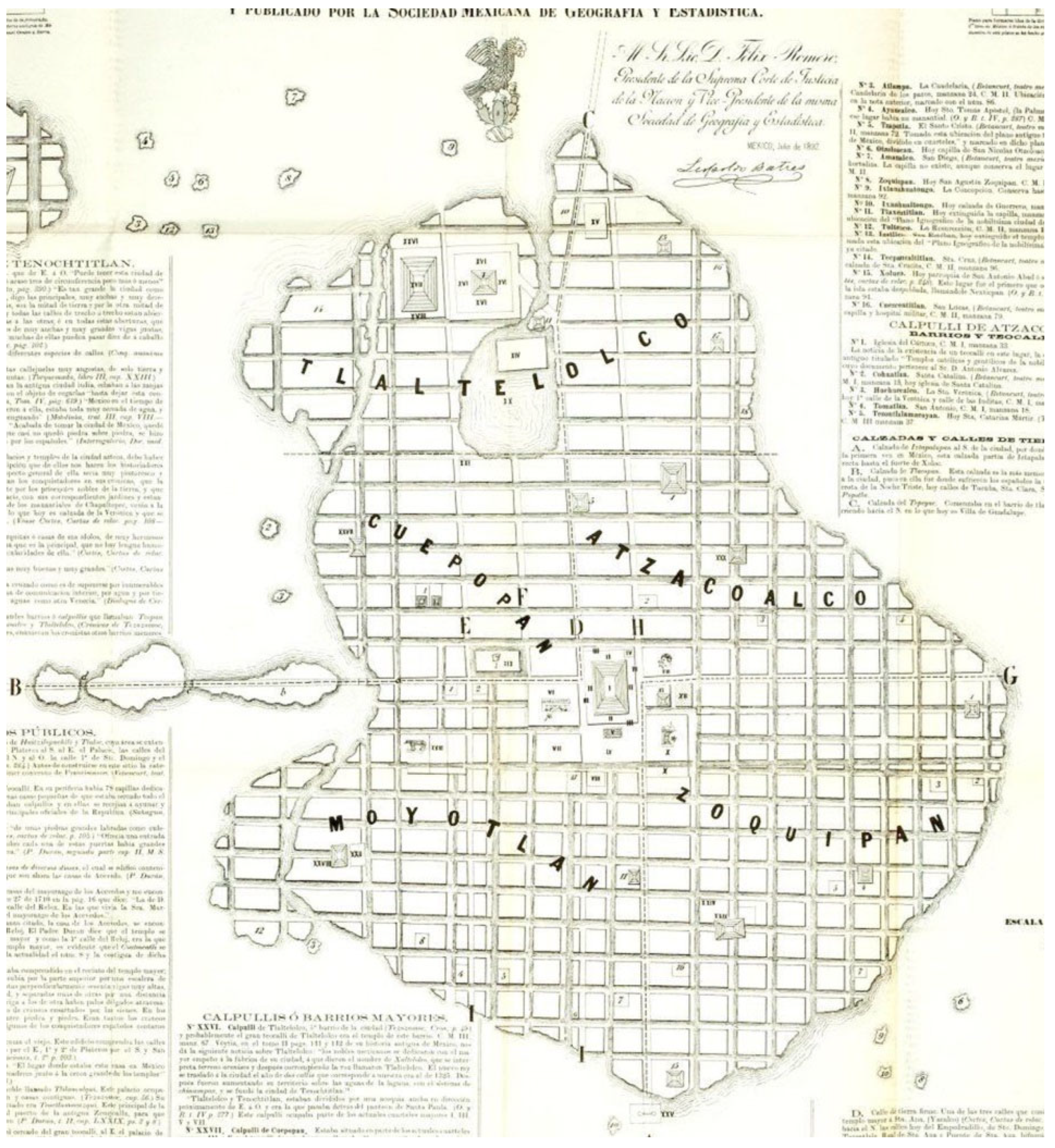

Regardless of royal instructions and all the analysis conducted so far, it is crucial not to overlook the main argument presented at the beginning of this article, which guides the research conclusions: in 1519, when Hernán Cortés arrived in the future New Spain, he encountered a well-ordered city, he encountered México-Tenochtitlan (

Figure 12).

The description made in 1520 reveals that this Mexica city not only surpassed contemporary Iberian cities in size but was also developed based on a marked orthogonality, organized around key elements such as a large marketplace, a significant ceremonial precinct, and four wide causeways. This finding is crucial as it shows that, although royal instructions from the metropolis looked to impose order from the foundation of new settlements, there was already an example of pre-existing urbanism in the Americas that displayed order and planning characteristics challenging traditional European conceptions.

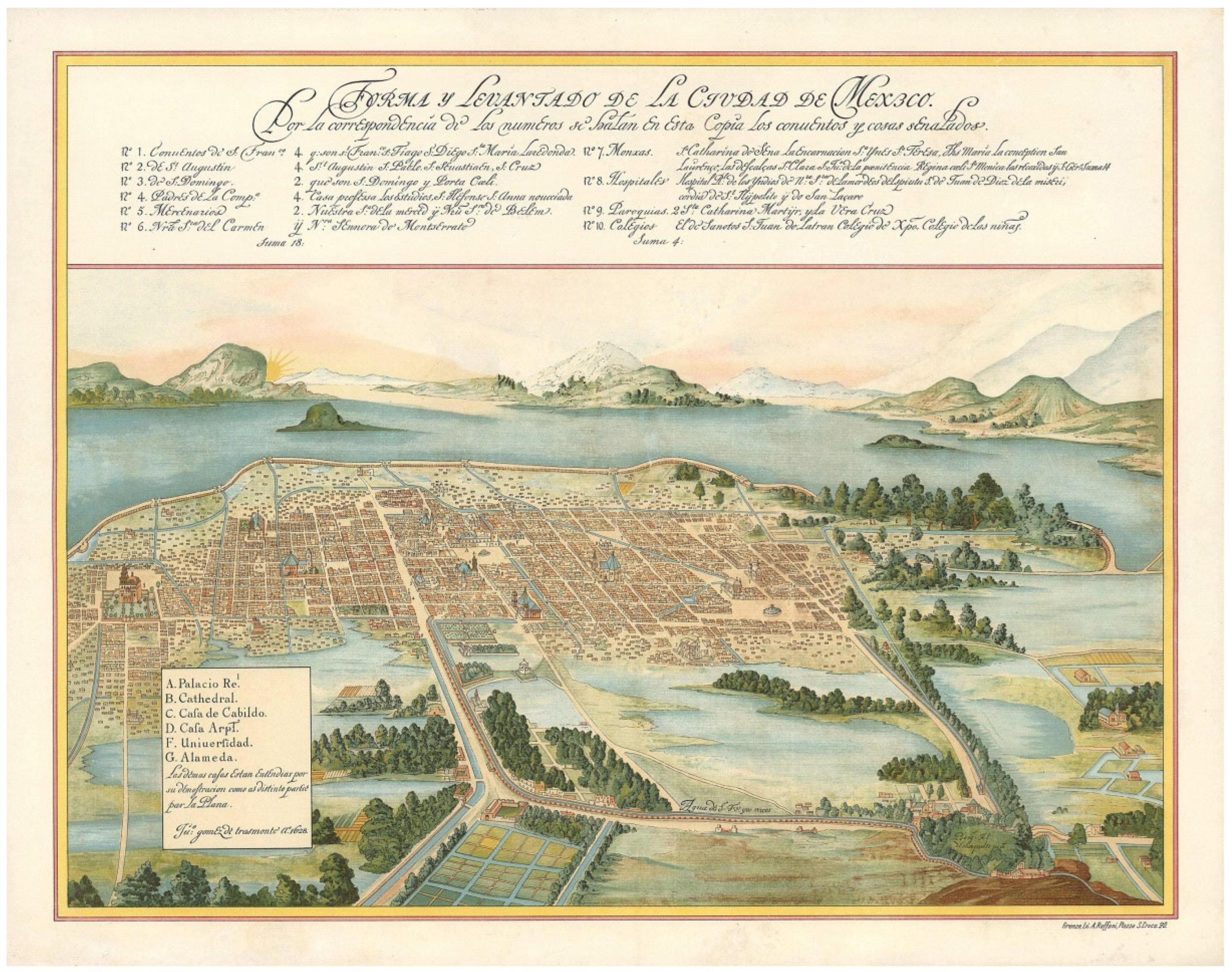

After the consolidation of the conquest of the territory later known as New Spain and the final fall of México-Tenochtitlan in 1521, Cortés made the weighty decision to set up the new capital in the same location as the former Mexica metropolis. This decision marked a turning point in the urban configuration of the region since it was not about creating an entirely new city in an empty space but rather designing and structuring a new Castilian city over the remains of a large pre-existing city. Thus, the new capital, named México, did not appear arbitrarily but as the fortuitous result of the fusion of two different urban visions: the Mexica tradition, with its planned infrastructure, and the Castilian approach, which contributed the urban planning criteria of the Spanish monarchy (

Figure 13).

México became an exceptional case within the urban development of colonial America. Unlike other cities founded by the conquerors up to that point, which lacked a systematic orthogonal plan, México applied a regular model with a structured geometric distribution, albeit based on a pre-Hispanic foundation. The resulting city was thus the product of the combination of the urban layout of the Mexica capital with the principles that the conquerors were beginning to adopt in their new settlements.

Until then, as previously analysed, the conquerors had no experience in creating cities with a strictly orthogonal layout. Neither in the Iberian Peninsula nor in the first cities founded in the Caribbean or mainland had a systematic regular spatial distribution been implemented. However, in the planning of the new city of México, more defined and organized planning criteria were adopted, adjusting a regular structure to the existing urban configuration. The final layout shared characteristics with earlier Castilian foundations and the structured city models developed in the Crown of Aragon since the Middle Ages.

The urban design of the new capital was structured around a cleared central space that had previously been occupied by the Templo Mayor, the main Mexica ceremonial centre. At this key point, a quadrangular main square was appointed, around which the main administrative, religious, and residential buildings for Spanish authorities were arranged. From this square, straight street extended, forming uniform and well-defined blocks, creating an orthogonal scheme with a level of regularity not seen in earlier settlements.

Despite the drastic transformation of the urban environment, some elements of the Mexica city were incorporated or repurposed in the new planning. Among them, the location of the old market square was kept, although its function and structure were changed. Additionally, several of the grand palaces belonging to the Mexica elite were repurposed and adapted as residences and administrative buildings for the Spanish. The orientation and layout of the main causeways connecting the city to the surrounding regions were also preserved, ensuring the continuity of the communication routes that had structured México-Tenochtitlan (

Figure 14).

The final configuration of the new city’s layout was set up in a quadrangular design, with a distribution of six blocks in width by thirteen in length, thus creating a grid system based on the pre-Hispanic city. The planning of this layout, although traditionally attributed to García Bravo –a key figure in structuring several cities in the New World– most likely consisted of conducting the topographic survey of the streets, establishing the limits between the Spanish-controlled city and the area reserved for the indigenous population, and defining the division of plots for distribution among the conquistadors who had participated in Cortés’ campaign.

In any case, México City became the clearest reference for colonial urbanism in America. Its orthogonal layout model, although based on a pre-existing reality, set a precedent for future city foundations, merging a form of urban structuring that spread throughout the viceroyalty and left a lasting impact on the development of Hispanic American cities.

What was significant in the context of colonial urbanism and its evolution over the centuries was that the final design of México City marked a turning point in urban planning. Its configuration not only represented a fusion of pre-existing elements with Castilian urban principles but also set up a territorial planning model that would be replicated in the newly conquered territories from that moment on. México City became a fundamental reference, serving as the basis for developing a new way of structuring urban space in America and, over time, influencing urban planning on other continents.

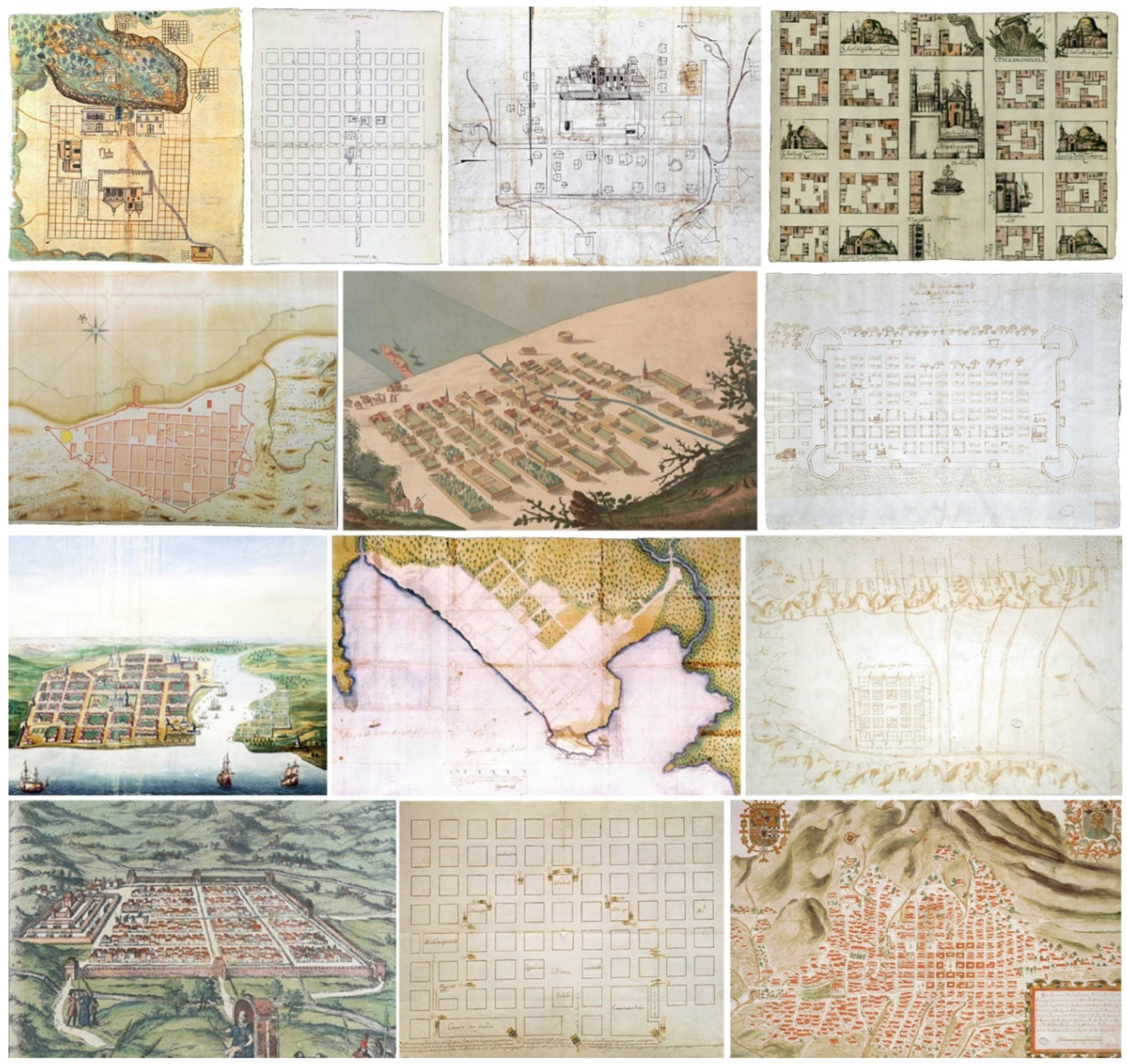

Following the foundation of México, a rapid expansion of cities laid out in regular, orthogonal schemes took place across the American continent. This phenomenon not only transformed the urban geography of the New World but also laid the foundations for a systematic planning tradition that would later influence other parts of the world. From the 16th century onward, cities founded by the Spanish and their successors followed principles of geometric planning, in which the distribution of streets and squares responded to criteria of functionality, aesthetics, and administrative control (

Figure 15).