1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the deadliest forms of cancer worldwide, claiming countless lives each year. The development of the disease is closely tied to chronic liver diseases, such as Hepatitis B and C, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cirrhosis linked to alcohol abuse [

1,

2]. While antiviral therapies have extended the lives of patients with hepatitis and cirrhosis and even curbed liver cancer rates in some cases, there is a growing concern. The prevalence of HCC stemming from non-infectious liver diseases is on the rise, solidifying its status as a pressing worldwide health challenge.Ranking as the sixth most common malignant tumor globally, HCC stands is the third deadliest cancer worldwide. Despite strides in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, the outlook for HCC patients remains grim, with a mere 20% survival rate at the five-year mark [

3,

4]. To turn the tide, prioritizing screening, early detection, and prompt intervention for at-risk groups is essential to boosting survival outcomes.

HCC has a complex and varied pathogenesis, necessitating diagnostic methods to adapt to the underlying causative factors and endemic areas. Currently, serological tests and imaging techniques are the most common methods for early diagnosis of HCC. With. The deepening of research on biomarkers of HCC, such as genome, epigenetic inheritance, and metabolites, as well as the deepening of research on liquid biopsy and multi-omics combined models, has brought the possibility of early diagnosis of HCC. Various types of immune and targeted drugs have been successfully introduced based on the immune escape mechanism related to HCC, and the integration of conversion and interventional therapies for patients with mid - to advanced HCC has increased the odds of surgery and notably prolonged tumor-related survival. This offers glimmer hope for the treatment of HCC. In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has witnessed a remarkable growth. They have been extensively utilized in imaging, pathology, disease management, and drug development. AI has revolutionized the traditional medical paradigm. There is a strong belief that AI will emerge as an effective means of combating HCC in the future [

5].

2. Pathophysiology of HCC

The precise cellular origin of HCC remains a topic of ongoing debate. Similar to other carcinomas, HCC may arise from liver stem cells, a transient amplifying cell population, or even fully differentiated hepatocytes. The development of HCC is a multifaceted, multi-step process driven by a combination of genetic susceptibility, viral and non-viral risk factors, and intricate interplay within the cellular microenvironment, including immune cells. Chronic liver disease further compounds these effects, creating a fertile ground for malignant transformation. A critical factor in HCC progression is dynamic tumor microenvironment. If HCC tumor cells fail to effectively display antigens and evade immune detection—or if the microenvironment is saturated with cells and soluble factors that suppress or neutralize cytotoxic T lymphocytes—the tumor can successfully dodge the host’s immune defenses, allowing it to thrive unchecked.The initial stage in triggering a tumor-specific T-cell response hinges on the expression of tumor antigens. During hepatocarcinogenesis, a spontaneous immune response can be activated due to the abnormal expression of oncofetal and cancer antigen genes. Conversely, genomic mutations that arise as HCC progresses can result in amino acid alterations, ultimately resulting in novel cancer antigens [

6,

7]. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) is frequently employed as a surrogate measure for the abundance of neoantigens because the likelihood of identifying T lymphocytes specific to these neoantigens correlates with TMB. Advances in sequencing technology, particularly next-generation sequencing (NGS), have enabled comprehensive mapping of numerous tumor mutation profiles [

8,

9].

HCC is characterized by a diverse array of soluble mediators that play a pivotal role in modulating anti-tumor immune responses. For example, TGF-β exerts a suppressive effect on anti-tumor immunity at multiple stages. This cytokine not only hampers the activation of dendritic cells (DCs) but also impairs the functionality of T and natural killer (NK) cells. Similarly, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which is secreted by both tumor cells and the surrounding stroma, not only drives tumor angiogenesis but also undermines the antigen-presenting capabilities of DCs and the stimulatory potential of T cells. The anti-tumor efficacy of VEGF inhibitors can, in part, be attributed to their ability to counteract these immune-suppressive mechanisms [

10]. In patients with HCC, reduced serum levels of IFNγ are closely linked to more advanced disease stages and worse prognosi [

11].

All of these studies have confirmed that immune escape is an important research direction in the treatment of HCC.

3. Early Diagnosis of HCC

3.1. Imaging

HCC can often be diagnosed using non-invasive imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), owing to its characteristic radiographic features, such as arterial hyperenhancement, venous washout, and capsule enhancement [

12]

. Alpha-fetoprotein(AFP), AFP-L3(lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive α-fetoprotein), Des-γ-carboxy Prothrombin (DCP). were used as auxiliary indicators for HCC diagnosis.

LI-RADS A standardized framework for interpreting liver imaging in high-risk patients (cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis B, or prior HCC), designed to improve consistency in diagnosing HCC and other liver lesions.It Reduces variability in imaging interpretation.Evidence-based, with regular updates (e.g., LI-RADS 2018)and Integrates seamlessly into multidisciplinary HCC care.Through the disposal of high-risk groups(.LR-3-5,M,TIV,NC): Early diagnosis of HCC is necessary, and functional imaging and the use of hepatobiliary-specific MRI contrast agents, such as gadoxetic acid disodium (Gd-EOB-DTPA), have revolutionized HCC diagnosis by enabling the precise detection of small and early stage HCC.

AI algorithms can analyze image patterns; the early diagnosis of medical images has been the focus of much research attention. Inter-observer variability can sometimes have a considerable impact on diagnostic results, and algorithms can be utilized to improve the accuracy of diagnosis.

3.2. Liquid Biopsy and New Biomarkers

3.2.1. New Biomarkers

AFP, vitamin K deficiency, antagonist-II induced protein (PIVKA-II) (DCP), and AFP L3 are all traditional serum tumor markers; AFP is often used as a serologic marker for the diagnosis of HCC. Some patients with HCC have normal or low levels of AFP even when the disease is advanced.15–30% of patients with advanced HCC have normal serum AFP levels, and the use of vitamin K-containing drugs may result in lower PIVKA-II values. We found that vitamin K antagonists and diseases causing vitamin K deficiency (e.g., biliary obstruction or cholestasis) may lead to elevated PIVKA-II values [

13]. Increased PIVKA-II concentrations may occur in patients with renal insufficiency. Drugs containing vitamin K analogs may also have caused bias. To avoid the limitations of traditional tumor markers and achieve early diagnosis of HCC, the concept of new tumor markers has been proposed. GPC3 is a cell surface proteoglycan similar to AFP, which is usually undetectable in healthy adult livers and can be observed only in fetal livers.Glypican-3 (GPC3) can be used as a key complementary biomarker for AFP-negative HCC, and it significantly improves the sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of HCC [

14]. Osteobridging protein (OPN) is another highly promising serologic biomarker for the diagnosis of HCC; we have found that it demonstrates diagnostic advantages in small HCC and in cases of AFP-negative HCC [

15]. Golgi protein 73 (GP73) levels are elevated in patients with HCC, and GP73 possesses superior sensitivity and specificity to AFP in predicting early stage HCC; it is also a promising therapeutic target for HCC. GP73 overexpression in carcinoma cells enhances the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and pro-mitotic signaling in vascular endothelial cells, thereby promoting angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

16]. The level of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) helps differentiate early stage precancerous HCC from progressive HCC. Researchers have found that the combined detection of HSP70 and GPC3 significantly improves the sensitivity and specificity of HCC diagnosis [

17]. The integration of multi-omics technologies and AI analysis is expected to further optimize early screening and personalized treatment strategies for HCC (

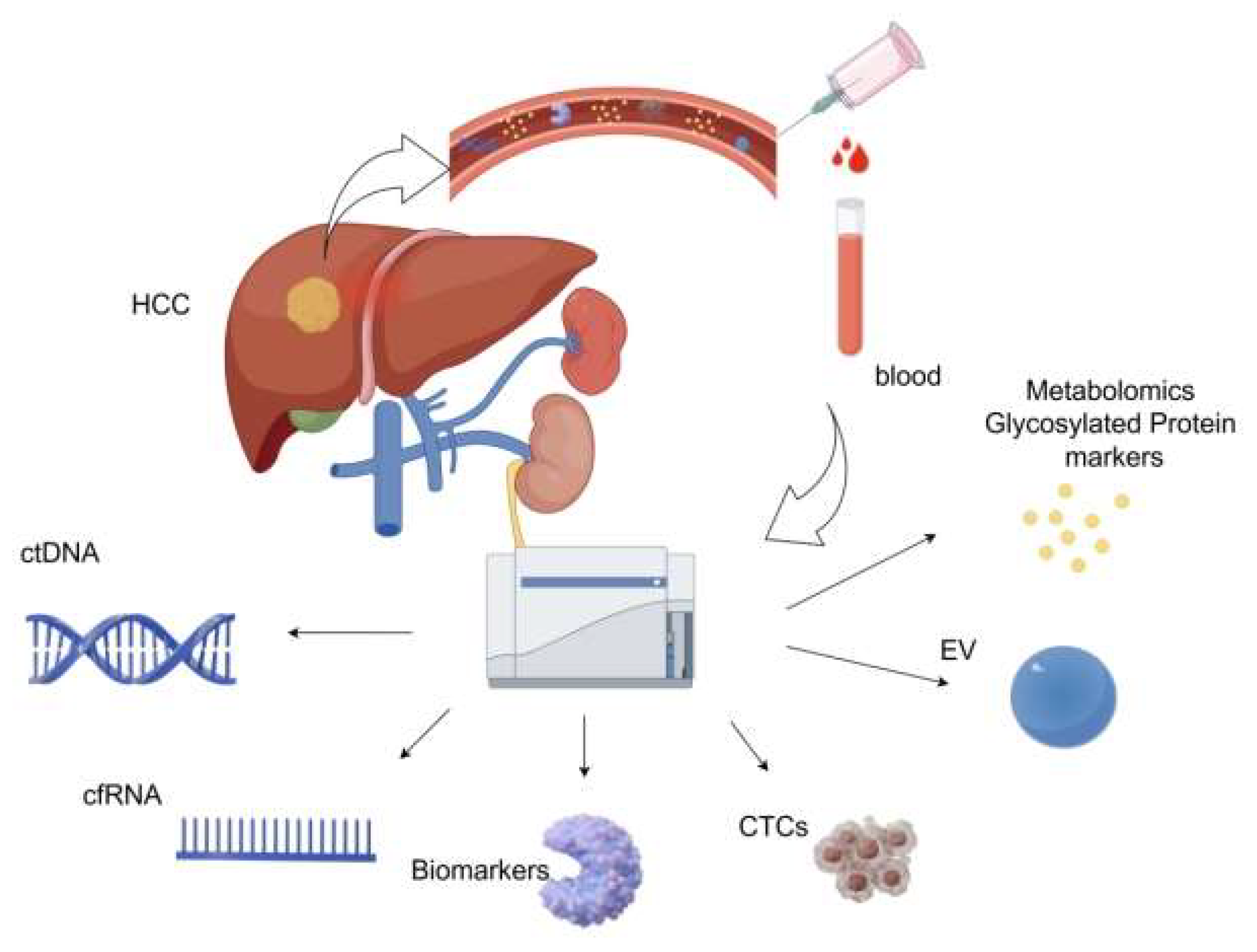

Figure 1).

3.2.2. Liquid Biopsy

Liquid biopsy represents a cutting-edge diagnostic approach that identifies diseases by examining biomarkers in bodily fluids, such as blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid. This innovative method has gained significant traction for both cancer research and clinical applications. Unlike conventional tissue biopsies, which involve invasive procedures, liquid biopsies provide a non-invasive, user-friendly, and real-time monitoring solution, making them indispensable in the realm of precision medicine. LItis not far-fetched to predict that this technique will become increasingly pivotal in shaping the future of medical diagnostics.

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) are tumor cells isolated from the bloodstream. Some CTCs can survive immune attacks and evade destruction, serving as direct evidence of tumor presence and metastatic potential, and they also play a pivotal role in the prognostic assessment of the disease [

18]. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a tumor-specific DNA fragment present in body fluids, such as blood, which forms part of the free DNA (cfDNA). Tumor cells produce these fragments via apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion [

19]. Virus-derived sequences, single-nucleotide variants, and aberrant methylation patterns can be used to distinguish ctDNA from non-tumor cfDNA [

20]. We believe that ctDNA, when combined with advanced technologies such as NGS and AI, has a very high potential for early cancer detection and will play a key role in the early screening and therapeutic monitoring of HCC.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and long-chain non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) comprise cell free RNAs (cfRNAs), which can serve as key liquid biopsy biomarkers for cancer detection and surveillance applications. mRNA (cf-mRNA) was sequenced, and this scientific group discovered and validated a cf-mRNA signature consisting of 10 genes that effectively differentiated HCC patients from hepatitis patients and normal controls, demonstrating the enormous clinical potential of cf-mRNA for tumor diagnosis and subtype classification [

21].

Large-scale genomics and genome-wide studies utilizing comprehensive genomic tools have enhanced our knowledge of cancer evolution and heterogeneity. Genome-wide studies using NGS have explored a wide range of genetic and epigenetic alterations associated with liver tumorigenesis, noting that epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and deregulated non-coding RNA expression, are strongly associated with hepatocellular carcinogenesis [

22].

Extra Cellular Vesicles (EV)such as exosomes, micro-vesicles, and apoptotic bodies also can serve as critical tools in liquid biopsy for HCC early detection and diagnosis [

23]. Metabolomic and Glycosylated Protein Markers have demonstrated significant potential for the early diagnosis of HCC [

24,

25].

4. Treatment of HCC

The approach to treating HCC requires multidisciplinary effort, bringing together expertise from hepatology, surgical teams, diagnostic and interventional radiology, oncology, and pathology. For advanced cases, a combination of treatment strategies is typically used. Historically, surgical resection and liver transplantation have been regarded the sole curative interventions for HCC. Partial hepatectomy, however, remains a feasible option, but only for a specific subset of patients: those with a single tumor, no significant vascular invasion, absence of cirrhosis, and no clinically evident portal hypertension. Careful patient selection is critical to ensure the best possible outcomes, and transplantation is reserved for patients with early HCC within the adapted version of the Milan criteria [

26].The formulation of an individualized and systematic conversion treatment plan is undoubtedly the most suitable option for patients. Experts have proposed a combined treatment plan of interventional and systemic therapy and have explored the aspects of conversion treatment for advanced HCC.

4.1. Immunotherapy for HCC

HCC progression is regulated by the immune system. Various immune mechanisms play crucial roles in the development and progression of HCC and are closely related to prognosis. Immunotherapy may be an effective treatment for HCC, and immunotherapies, such as anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), have demonstrated potent anti-tumor activity in certain patients. Atilizumab, an antibody that inhibits programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), in combination with bevacizumab, a VEGF-neutralizing antibody, is a standard first-line treatment for HCC. This therapy has become or will soon become the standard first-line treatment option for HCC.New therapeutic approaches, including ICIs, TKIs, monoclonal antibodies (CIs),cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), and VEGF inhibitors, have greatly improved the treatment of HCC.

Studies on survival and disease control in patients with HCC have shown that multimodal therapeutic strategies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with VEGF inhibitors, TKIs, or other immunotherapies, have the potential to dramatically improve patient prognosis [

27]. Academic exploration of novel immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3) and T-cell immunoglobulin mucin 3 (TIM3) inhibitors, has also revealed promising clinical applications [

28,

29]. The molecular mechanisms of tumor stem cells (CSCs) and tumor-associated growth factor signaling pathways are becoming increasingly clear, and we are striving to develop targeted therapeutic regimens aimed at interfering with tumor proliferation, metastasis, and treatment resistance [

30]. A deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms of tumorigenesis and progression will lead to the development of targeted therapies to substantially improve the clinical outcomes of patients with HCC.

4.2. Interventional Therapy for HCC

Interventional therapies have emerged as crucial and increasingly popular treatment options for HCC. These approaches effectively control tumor growth, spare healthy liver tissue, and minimize toxic side effects. In the treatment of early stage HCC, the selection of locoregional therapy depends on factors such as tumor size, nature of the underlying liver condition, and overall liver function. Broadly speaking, these therapies fall into two categories: percutaneous and intra-arterial. The latter includes a range of procedures, such as bland embolization (TAE), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), drug-eluting bead chemoembolization (DEB-TACE), selective internal radioembolization therapy (SIRT), and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), all of which leverage the arterial blood supply unique to HCC. Recent advancements in interventional therapy have paved the way for innovative directions, particularly the development of new drug-eluting beads (DEBs) that can be loaded with various chemotherapeutic agents. Yang et al. characterized Irinotecan DEB in vitro and examined its properties as a chemoembolization agent. In a porcine model of hepatic arterial embolization, they measured drug plasma levels, conducted histopathology, and compared the results to those of intra-arterial bolus injection of the drug. The use of DEB resulted in a decrease in peak plasma levels. Precision oncology, based on these findings, is potentially one of the most important aspects of present and future developments in interventional oncology. Imageable radiopaque beads were created. During the bead manufacturing process, a radio-absorber such as iodine or barium is integrated into these particles. These beads enabled the real-time confirmation of HCC targeting during the procedure. Immunoembolization is another emerging area, as noted by Yamamoto et al., in which granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), a form of systemic immunotherapy, directly injected into the arteries that supply HCC has shown promising results. This approach not only extends patient survival, but also slows the progression of extrahepatic metastases [

31]. In recent years, the development of nanoparticle-based formulations for cancer treatment has surged, with many being designed to deliver therapeutic agents. Additionally, there is a growing interest in exploring other therapeutic strategies, such as light, heat, ultrasound, magnetic fields, redox reactions, reactive oxygen species, and systemic therapies combined with transarterial embolization techniques [

32]. Integrating embolization methods with percutaneous ablation therapy can further amplify treatment efficacy and boost patient outcomes [

33]. As advancements in chemotherapy and nuclear medicine continue, it is anticipated that more refined and effective interventional approaches will become the standard in clinical practice.

With the continuous development and progress in medical technology, it is believed that new drugs and technologies will be introduced into clinical treatment in the future.

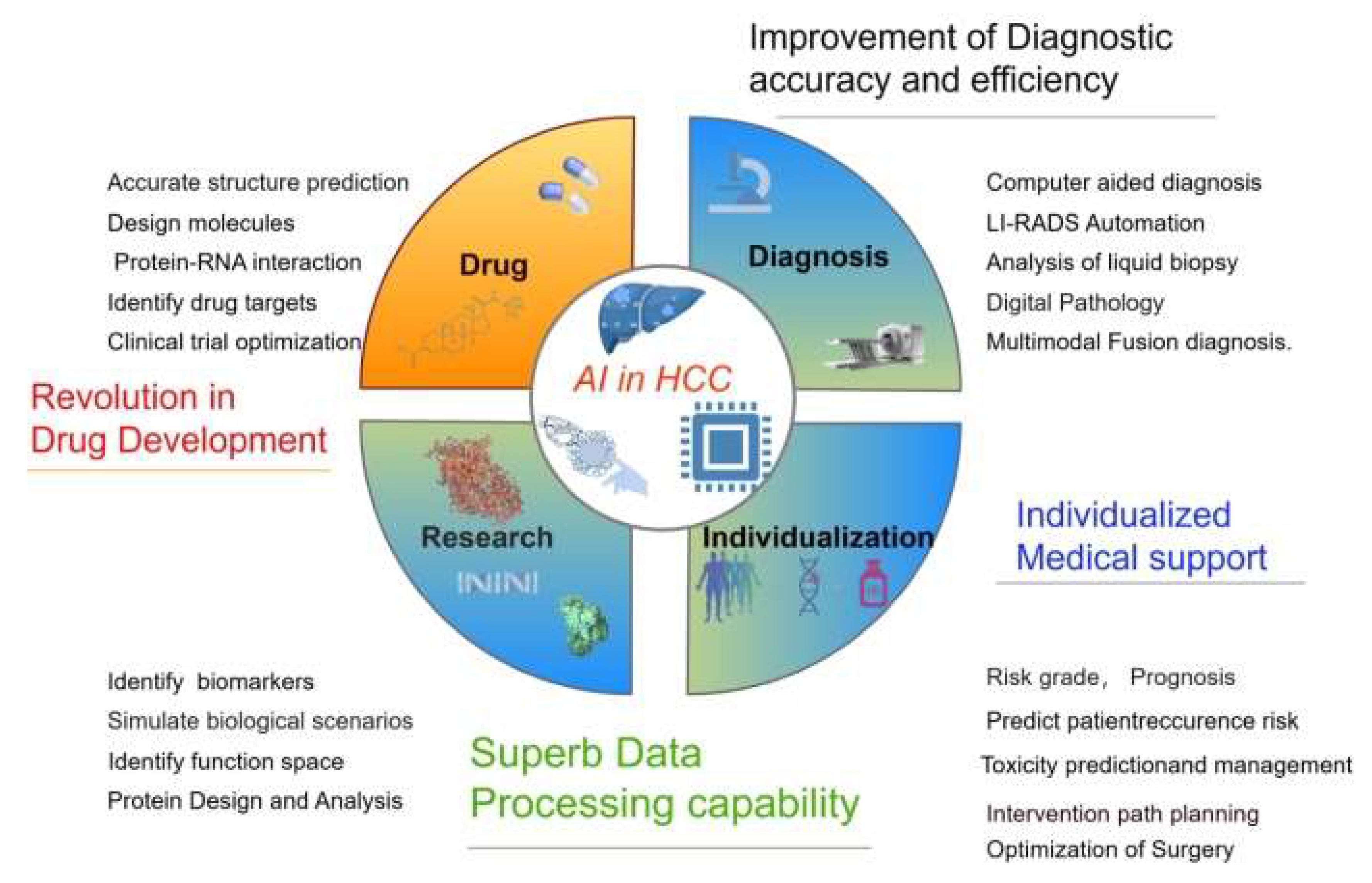

5. The Application of AI in HCC

AI has rapidly emerged as a transformative tool across various domains of cancer research, encompassing diagnosis, grading, drug discovery, treatment development, and the prediction of clinical outcomes [

34,

35] (

Figure 2).

5.1. AI in HCC Research

Over the past few decades, there has been an explosion of large and complex datasets (contain genomic and molecular data from numerous tissues and individual cells) available to us. To improve the detection and characterization of HCC, the academic community has designed a variety of AI algorithms that integrate multi-omics approaches. Deep learning, often referred to as deep neural networks, relies on a hierarchical structure of hidden layers, where data is processed and features are extracted through a sequential flow of these interconnected nodes [

34]. AI excels in creating synthetic data, which essentially mimics real-world patterns and characteristics, thereby enhancing target-recognition capabilities. By leveraging AI-driven algorithms to model diverse biological scenarios, researchers have afforded greater flexibility in investigating and dissecting complex phenomena, opening new avenues for exploration and analysis [

36,

37]. AI has the potential to create synthetic data using existing knowledge and patterns. These synthetic data can be used to train AI models and uncover potential therapeutic targets that have been overlooked in the past. and assists in the discovery of therapeutic targets through rapid biomedical text mining. By mining previous studies, they correlated diseases, genes, and biological processes, quickly identified the biological mechanisms involved in disease development and progression, and identified potential drug targets and biomarkers [

38]. Cannon and colleagues demonstrated that by analyzing the connections between approved medications, molecular targets, and therapeutic indications, AI can expedite drug development. This is achieved by connecting the well-established high-confidence targets of existing drugs to novel, uninvestigated diseases [

39]. Verifying targets using cell and animal models is a crucial phase in target discovery. This step can reduce the project failure rate and drug development expenses in the pharmaceutical sector. Ren et al., by leveraging a deep - learning approach, pinpointed Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 20 (CDK20) as a therapeutic target for HCC. Small molecule inhibitors, efficiently designed by generative AI, exhibit selective anti-proliferative effects in HCC cell lines [

40].

5.2. AI in HCC Early Diagnosis

5.2.1. AI in Imaging Diagnosis

The application of AI in medical imaging has brought excellent convenience to the diagnosis of diseases and can assist in the analysis of imaging features.

Ultrasonography (US) is a commonly used method for screening HCC, However, it is relatively less sensitive, with a sensitivity of only 46–63%. dependence on operator experience, equipment quality, and patient body habitus.Yang et al. developed a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN), using a large, multicenter ultrasound imaging database from 13 hospital. The accuracy of this model for lesions detected by US was 86.5%, which was superior to that of contrast-enhanced CT ( 84.7%) and only slightly inferior to that of MRI (87.9%) [

41]. Guo et al. demonstrated that a deep learning(DL) algorithm applied to liver lesions seen by Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound(CEUS),This model could increase the sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy of CEUS for detecting HCC, It proved that the three-phase CEUS image based computer aided diagnosis(CAD) is feasible for liver tumors with the proposed Deep Canonical Correlation Analysis with Multiple Kernel Learning(DCCA-MKL) framework [

42].

Shukla et al. demonstrated that an AI-driven cascaded fully convolutional Neural Network for HCC screening and prediction showed that the total accuracy rate of the training and testing procedure was 93.85% in the various volumes of 3D Image Reconstruction for Comparison of Algorithm Database(3DIRCAD) datasets tested [

43]. AI and Deep learning have revolutionized the traditional imaging diagnosis mode and have demonstrated high performance in the diagnosis and treatment of liver malignancies. Clinicians have used advanced deep network algorithms to detect HCC lesions, diagnose diseases, and predict prognosis, thereby significantly enhancing the efficiency of liver cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Mokrane and his colleagues conducted a small retrospective study on patients with liver cirrhosis and those with uncertain liver lesions, and they undergo diagnostic liver biopsy.Theirradiomics signature based on 13,920 CT imaging classifiers,the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.70 (95%CI 0.61-0.80) and 0.66 (95%CI 0.64-0.84) in discovery and validation cohorts. The signature was influenced neither by segmentation nor by contrast enhancement [

44].

To date, AI has been applied less frequently to MRI imaging of HCC than to CT.However, MRI provides more data regarding liver imaging, relying on the powerful computing power of AI, may have more promising prospects for assisting in the diagnosis of HCC, and poses greater challenges for the design of AI modes with a sensitivity of 92%. Hamm et al. developed an NN algorithm with a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based deep learning system (DLS), which classifies common hepatic lesions on multi-phasic MRI, successfully classifying MRI liver lesionficity of 98% and an overall accuracy of 92% [

45]. The above studies indicate that AI can enhance the decision-making ability of clinicians by identifying patients at high risk of HCC.

5.2.2. AI in Histopathology

Pathological diagnosis is the gold standard for HCC diagnosis. Compared with imaging and other examination methods, it can more clearly describe the characteristics of the tumor and is of great significance for the formulation of treatment strategies [

46]. Imaging is the primary method for screening typical HCC lesions based on imaging features. Although non-invasive criteria allow the diagnosis of HCC in most cases, histological examination of tumor samples is often required for masses with atypical features on imaging or for different diagnoses of benign liver tumors, cholangiocarcinoma (HCC in most cases or metastasis). Histological examination of tumor samples is often required for masses with atypical features on imaging or for different diagnoses of benign liver tumors, cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), or metastasis. Liao et al. used a CNN to distinguish HCC from adjacent normal tissues,using two large datasets of hematoxylin and eosin stained digital slides, with an area under the curve(AUC) above 0.90 [

47]. Kiana et al. developed a tool able to classify image patches as HCC or CCA. achieved an accuracy of 0.885 for the validation of the assisted state, and the model accuracy significantly affected the diagnostic decisions of all 11 pathologists [

48]. AI can identify features that are beyond human eye recognition, relatively concealed, and quantitatively describe pathological details. It does not merely perform qualitative grading but provides a quantitative description of the pathological features. Moreover, the evaluation results are objective and consistent, avoiding diagnostic outcome variations caused by regional or subjective factors [

49,

50].

Many studies have confirmed that detection and diagnosis based on deep learning algorithms have improved efficiency and achieved high diagnostic efficacy. This is an intelligent method for the detection and diagnosis of HCC.

5.3. AI In Drug Research and Development

Traditional drug Development is a protracted and costly endeavor, typically commencing with the identification of a target and potentially spanning over a decade to unearth and refine a drug’s target of action, followed by an additional period dedicated to development.As the pioneering and most advanced field within the omics disciplines, multiomic data offers researchers a multifaceted lens into interconnected molecular insights, spanning static genomic details as well as dynamic, time- and space-sensitive expression and metabolic patterns. Unlike single-omic methods, integrated multiomic analysis provides a more holistic understanding of disease pathways, serving as a powerful tool for uncovering biomarkers and identifying potential therapeutic targets [

51,

52,

53].

On May 8, 2024, AlphaFold 3was published by Google DeepMind Technologies Limited,This model in the accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions.Unlike earlier versions that required special treatment for different molecular types, AlphaFold 3’s framework aligns more closely with the fundamental physical principles governing molecular interactions. This makes the system significantly more efficient and reliable for studying novel molecular interactions [

34,

54,

55]. AlphaFold 3’s sophisticated grasp of protein-ligand dynamics offers a groundbreaking potential in the realm of drug discovery. Precisely pinpointing binding sites and determining the ideal configurations for drug candidates dramatically accelerates the drug design pipeline [

56]. This capability is particularly transformative in the field of HCC research, where the rapid development of targeted therapies could yield treatments that are both more potent and less prone to adverse effects. Such advancements are reshaping therapeutic strategies and setting new benchmarks in precision medicine [

57,

58]. While challenges remain, such as the limited accuracy in predicting protein-RNA interactions, these hurdles are being addressed, paving the way for innovations in personalized medicine [

56]. Meanwhile, AI has cemented its role as a game-changer in drug development, revolutionizing the identification of new drug targets and repurposing of existing compounds, thereby opening new frontiers in medical research.

AI is also powerful in individualized medical supportsuch as HCC risk grade,prognosis, recurrence risk,toxicity, intervention path planning, and optimization of surgery and treatment.

6 Conclusion

The HCC landscape is evolving rapidly with advances in AI-driven diagnostics, biomarkers, and multimodal therapies. Although challenges such as drug resistance and accessibility persist, the integration of immunotherapy and precision oncology heralds a new era in HCC management. Ongoing trials and interdisciplinary approaches promise further breakthroughs, emphasizing early detection and personalized care.

The increasing number of deaths caused by HCC is a growing concern. It is hoped that universal HBV vaccination, rising cure rates of HCV infection, and improved monitoring will alleviate this burden. HCC is a complex disease often associated with liver cirrhosis, and a multidisciplinary approach in specialized clinics is needed to maximize its impact on the disease course. In the past decade, clinical management of HCC has improved, especially in patients with advanced HCC. Other areas of management still lack effective interventions, such as chemoprevention in patients with liver cirrhosis and adjuvant therapy after surgical resection or ablation. As the number of effective systemic drugs discovered in phase 3 trials continues to grow, the challenge lies in determining the sequence of systemic treatments to maximize clinical benefits while achieving the least toxic effects and costs. In the early stages, the prospects of combination therapy and use of systemic drugs will shape future research plans for HCC.

Author Contributions

Cheng Bo Li was responsible for data article writing; Bao Cheng Deng designed the article and took part in writing and revising.

Funding

Science Planning Project of Liaoning Province.2019JH2/10300031-05: National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number:12171074.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

HCC:Hepatocellular carcinoma, AFP, alpha-fetoprotein,DCP, Des-γ-carboxy Prothrombin NAFLD,Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease AI, Artificial intelligence,DC,Dendritic Cells, TMB,Tumor mutational burden ;TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta,VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor, IFNγ,interferon gamma, Gd-EOB-DTPA gadoxetic acid disodium, PIVKA-II,vitamin K absence or antagonist-II,GPC3,Glypican-3,OPN, osteopontin,GP73,Golgi protein 73,TME,Tumor Microenvironment.HSP70.Heat Shock Protein 70,CTCs,Circulating Tumor Cells, ctDNA,Circulating tumor DNA,cfDNA,cell-free DNA,NGS,next-generation sequencing,miRNA, MicroRNA,mRNA,messenger RNA, lncRNA,long non-coding RNA, cfRNA,cell-free RNA, cf-mRNA,cell-free mRNA, EV,Extra Cellular Vesicles,TKIs,tyrosine kinase inhibitors, ICIs,immune checkpoint inhibitors,CIs,monoclonal antibodies,CTLA4,cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4,PDL1,Programmed Death-Ligand 1,LAG3,Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3 and TIM3,T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain containing-3, CSCs,cancer stem cells,TAE,Transarterial therapies includebland embolization.TACE, transarterial chemoembolization,DEB–TACE drug-eluting beads–transarterial chemoembolization,SIRT,selective internal radioembolization therapy,HAIC, and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy,DEBs,drug-eluting beads,GM-CSF,granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor,CDK20,Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 20,DCNN,,deep convolutional neural network,US,Ultrasound,DL,deep learning(DL),CEUS,Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound,CAD,computer aided diagnosis,DCCA-MKL,Deep Canonical Correlation Analysis with Multiple Kernel Learning,3DIRCAD,3D Image Reconstruction for Comparison of Algorithm Database,CNN,convolutional neural network,DLS,deep learning system (DLS), CCA,cholangiocarcinoma,AUC, area under the curve.

References

- Tsukuma, H., T. Hiyama, S. Tanaka, M. Nakao, T. Yabuuchi, T. Kitamura, K. Nakanishi, I. Fujimoto, A. Inoue, H. Yamazaki, and et al. “Risk Factors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma among Patients with Chronic Liver Disease.” N Engl J Med 328, no. 25 (1993): 1797-801. [CrossRef]

- Ha, N. B., N. B. Ha, A. Ahmed, W. Ayoub, T. J. Daugherty, E. T. Chang, G. A. Lutchman, G. Garcia, A. D. Cooper, E. B. Keeffe, and M. H. Nguyen. “Risk Factors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease: A Case-Control Study.” Cancer Causes Control, 23, no. 3 (2012): 455-62. [CrossRef]

- Bray F., Laversanne M: Sung, J. Ferlay, R. L. Siegel, I. Soerjomataram, and A. Jemal. “Global Cancer Statistics 2022: Globocan Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries.” CA Cancer J Clin 74: no. 3 (2024): 229-63. [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H., Arnold, M. J. Ferlay, O. Lesi, C. J. Cabasag, J. Vignat, M. Laversanne, K. A. McGlynn, and I. Soerjomataram. “Global Burden of Primary Liver Cancer in 2020 and Predictions to 2040.” J Hepatol 77, no. 6 (2022): 1598-606. [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, J., T. P. Seraphin, T. Luedde, and T. G. Simon. “Artificial Intelligence for the Prevention and Clinical Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” J Hepatol 76, no. 6 (2022): 1348-61. [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M., Johnson, B. A., 3rd, E. R. Lutz, D. A., Laheru, E. M., and Jaffee. “Targeting Neoantigens to Augment Antitumour Immunity.” Nat Rev Cancer 17, no. 4 (2017): 209-22.

- Flecken, T., N. Schmidt, S. Hild, E. Gostick, O. Drognitz, R. Zeiser, P. Schemmer, H. Bruns, T., Eiermann, D. A., Price, H. E. Blum, C. Neumann-Haefelin, and R. Thimme. “Immunodominance and Functional Alterations of Tumor-Associated Antigen-Specific Cd8+ T-Cell Responses in Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Hepatology 59, no. 4 (2014): 1415-26. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., C. Zhang, R. Xue, M. Liu, J. Bai, J. Bao, Y. Wang, N. Jiang, Z. Li, W. Wang, R. Wang, B., Zheng, A., Yang, J. Hu, K. Liu, S. Shen, Y. Zhang, M. Bai, Y. Wang, Y. Zhu, S. Yang, Q. Gao, J. Gu, D. Gao, X. W. Wang, H. Nakagawa, N. Zhang, L. Wu, S. G. Rozen, F. Bai, and H. Wang. “Deep Whole-Genome Analysis of 494 Hepatocellular Carcinomas.” Nature 627, no. 8004 (2024): 586-93. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z., J. Liang, R. Huang, W. Song, J. Ying, X. Bi, J. Zhao, Z. Shi, W. Liu, J. Liu, Z. Li, J. Zhou, Z. Huang, Y. Zhang, D. Zhao, J. Wu, L. Wang, X. Chen, R. Mao, Y. Zhou, L. Guo, H. Hu, D. Ge, X. Li, Z. Luo, J. Yao, T. Li, Q. Chen, B. Wang, Z. Wei, K. Chen, C. Qu, J. Cai, Y. Jiao, L. Bao, and H. Zhao. “Hbv Integrations Reshaping Genomic Structures Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Gut 73, no. 7 (2024): 1169-82. [CrossRef]

- Apte, R. S., D. S. Chen, and N. Ferrara. “Vegf in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development.” Cell 176, no. 6 (2019): 1248-64.

- Lee, I. C., Y. H. Huang, G. Y. Chau, T. I. Huo, C. W. Su, J. C. Wu, and H. C. Lin. “Serum Interferon Gamma Level Predicts Recurrence in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients after Curative Treatments.” Int J Cancer 133, no. 12 (2013): 2895-902. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. Y., J. Chen, C. C. Xia, L. K. Cao, T. Duan, and B. Song. “Non-invasive Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From Diagnosis to Prognosis.” World J Gastroenterol. 24, no. 22 (2018): 2348-62.

- Fujita, K., H. Kinukawa, K. Ohno, Y. Ito, H. Saegusa and Yoshimura T.. “Development and Evaluation of Analytical Performance of a Fully Automated Chemiluminescent Immunoassay for Protein Induced by Vitamin K Absence or Antagonist Ii.” Clin Biochem 48, no. 18 (2015): 1330-6. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A. F., X. Chen, and C. Li. “Clinical Utility of Biomarkers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Bratisl Lek Listy 125, no. 2 (2024): 102-06. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M., J. Zheng, F. Wu, B. Kang, J. Liang, F., Heskia, X., Zhang, Y. and Y. Shan. “Opn Is a Promising Serological Biomarker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis.” J Med Virol 92, no. 12 (2020): 3596-603. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., X. Hu, S. Zhou, T. Sun, F. Shen, and L. Zeng. “Golgi Protein 73 Promotes Angiogenesis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Research (Wash D C) 7 (2024): 0425. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Said A. and Al-Sayed M. I. Tealeb. “The Role of Heat Shock Protein 70 and Glypican 3 Expression in Early Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Egyptian Journal of Pathology 42, No. 2 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Qi, L. N., B. D. Xiang, and F. X. Wu, J. Z. Ye, J. H. Zhong, Y. Y. Wang, Y. Y. Chen, Z. S. Chen, L. Ma, J. Chen, W. F. Gong, Z. G. Han, Y. Lu, J. J. Shang, and L. Q. Li. “Circulating Tumor Cells Undergoing Emt Provide a Metric for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Cancer Res 78, no. 16 (2018): 4731-44.

- Campani, C., S. Imbeaud, G. Couchy, M. Ziol, T. Z. Hirsch, S. Rebouissou, B. Noblet, P. Nahon, K. Hormigos, S. Sidali, O. Seror, V. Taly, N. Ganne Carrie, P. Laurent-Puig, J. Zucman-Rossi, and J. C. Nault. “Circulating Tumour DNA in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma across Tumour Stages and Treatments.” Gut 73, no. 11 (2024): 1870-82.

- Kim, S. C., D. W. Kim, E. J. Cho, J. Y. Lee, J. Kim, C. Kwon, J. Kim-Ha, S. K. Hong, Y. Choi, N. J. Yi, K. W. Lee, K. S. Suh, W. Kim, W. Kim, H. Kim, Y. J. Kim, J. H. Yoon, S. J. Yu, and Y. J. Kim. “A Circulating Cell-Free DNA Methylation Signature for the Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Mol Cancer 22, no. 1 (2023): 164. [CrossRef]

- Roskams-Hieter, B., H. J. Kim, P. Anur, J. T. Wagner, R. Callahan, E. and Spiliotopoulos, C. W. Kirschbaum, F. Civitci, P. T. Spellman, R. F. Thompson, K. Farsad, W. E. Naugler, and T. T. M. Ngo. “Plasma Cell-Free Rna Profiling Distinguishes Cancers from Pre-Malignant Conditions in Solid and Hematologic Malignancies.” NPJ Precis Oncol. 6, no. 1 (2022): 28. [CrossRef]

- Toh, T. B., J. J. Lim, and E. K. Chow. “Epigenetics of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Clin Transl Med 8, no. 1 (2019): 13.

- Liu, J., L. Ren, S. Li, W. Li, X. Zheng, Y. Yang, W. Fu, J. Yi, J. Wang, and G. Du. “The Biology, Function, and Applications of Exosomes in Cancer.” Acta Pharm Sin B 11, no. 9 (2021): 2783-97.

- Kimhofer, T., H. Fye, S., Taylor-Robinson, M., Thursz, and E. Holmes. “Proteomic and Metabonomic Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review.” Br J Cancer 112, no. 7 (2015): 1141-56. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., E. Warner, N. D. Parikh, and D. M. Lubman. “Glycoproteomic Markers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Mass Spectrometry Based Approaches.” Mass Spectrom Rev 38, no. 3 (2019): 265-90. [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, M., F. Aucejo, and R. Kim. “General Overview of Neo-Adjuvant Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma before Liver Transplantation: Necessity or Option?” Liver Int 31, no. 8 (2011): 1081-9.

- Sangro, B., P. Sarobe, S. Hervás-Stubbs, and I. Melero. “Advances in Immunotherapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18, no. 8 (2021): 525-43.

- Du, W., Yang, M., Turner, A., Xu, R. L. Ferris, J. Huang, L. P. Kane, and B. Lu. “Tim-3 as a Target for Cancer Immunotherapy and Mechanisms of Action.” Int J Mol Sci 18, no. 3 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., M. F. Sanmamed, I. Datar, T. T. Su, L. Ji, J. Sun, L. Chen, Y. Chen, G. Zhu, W. Yin, L. Zheng, T. Zhou, T. Badri, S. Yao, S. Zhu, A. Boto, M. Sznol, I. Melero, D. A. A. Vignali, K. Schalper, and L. Chen. “Fibrinogen-Like Protein 1 Is a Major Immune Inhibitory Ligand of Lag-3.” Cell 176, no. 1-2 (2019): 334-47.e12.

- Becht, R., K. Kiełbowski, and M. P. Wasilewicz. “New Opportunities in the Systemic Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Today and Tomorrow.” Int J Mol Sci 25, no. 3 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A., Chervoneva, I., Sullivan, K. L., Unk Elman, C. F. Gonsalves, M. J. Mastrangelo, D. Berd, J. A. Shields, C. L. Shields, M. Terai, and T. Sato. “High-Dose Immunoembolization: Survival Benefit in Patients with Hepatic Metastases from Uveal Melanoma.” Radiology 252, no. 1 (2009): 290-8. [CrossRef]

- Bucalau, A. M., Tancredi, I., Verset. “In the Era of Systemic Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Transarterial Chemoembolization Still a Card to Play?” Cancers (Basel), 13, no. 20 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Dawoud, Mahmoud A., Rania E. Mohamed, Mohamed S. El Waraki, and Ahmed M. Gabr. “Single-Session Combined Radiofrequency Ablation and Transarterial Chemoembolization in the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” The Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 48, no. 4 (2017): 935-46. [CrossRef]

- Pun, F. W., I. V. Ozerov, and A. Zhavoronkov. “Ai-Powered Therapeutic Target Discovery.” Trends Pharmacol Sci 44, no. 9 (2023): 561-72. [CrossRef]

- Shiraiwa, K., R. Cheng, H. Nonaka, T., Tamura, I., Hamachi. “Chemical Tools for Endogenous Protein Labeling and Profiling.” Cell Chem Biol 27, no. 8 (2020): 970-85. [CrossRef]

- Viñas, R., H. Andrés-Terré, P. Liò, and K. Bryson. “Adversarial Generation of Gene Expression Data.” Bioinformatics 38, no. 3 (2022): 730-37. [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Xu, Z., Cao, L., Wang, M., Hou, K., Li. “The Discovery of New Drug-Target Interactions for Breast Cancer Treatment.” Molecules 26, no. 24 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., L. Sun, Y. Xia, T. Qin, S. Zhang, H. Poon, and T. Y. Liu. “Biogpt: Generative Pre-Trained Transformer for Biomedical Text Generation and Mining.” Brief Bioinform. 23, no. 6 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Cannon, D. C., J. J. Yang, S. L. Mathias, O. Ursu, S. Mani, A. Waller, S. C. Schürer, L. J. Jensen, L. A. Sklar, C. G. Bologa, and T. I. Oprea. “Tin-X: Target Importance and Novelty Explorer.” Bioinformatics 33, no. 16 (2017): 2601-03. [CrossRef]

- Ren, F., X. Ding, M. Zheng, M. Korzinkin, X. Cai, W. Zhu, A., Mantsyzov, A., and Aliper, V. Aladinskiy, Z. Cao, S. Kong, X. Long and B. H. Man Liu, Y. Liu, V. Naumov, A. Shneyderman, I. V. Ozerov, J. Wang, F. W. Pun, D. A., Polykovskiy, C. Sun, M. Levitt, A. Aspuru-Guzik, and A. Zhavoronkov. “Alphafold Accelerates Artificial Intelligence Powered Drug Discovery: Efficient Discovery of a Novel Cdk20 Small Molecule Inhibitor.” Chem Sci 14, no. 6 (2023): 1443-52. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., J. Wei, X. Hao, D. Kong, X. Yu, T. Jiang, J. Xi, W. Cai, Y. Luo, X. Jing, Y. Yang, Z. Cheng, J. Wu, H. Zhang, J. Liao, P. Zhou, Y. Song, Y. Zhang, Z. Han, W. Cheng, L. Tang, F. Liu, J. Dou, R. Zheng, J. Yu, J. Tian, and P. Liang. “Improving B-Mode Ultrasound Diagnostic Performance for Focal Liver Lesions Using Deep Learning: A Multicentre Study.” EBioMedicine 56 (2020): 102777. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. H., D. Wang, Y. Y. Qian, X. Zheng, C. K. Zhao, X. L. Li, X. W. Bo, W. W. Yue, Q. Zhang, J. Shi, and H. X. Xu. “A Two-Stage Multi-View Learning Framework Based Computer-Aided Diagnosis of Liver Tumors with Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound Images.” Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 69, no. 3 (2018): 343-54. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. K., M. Zakariah, W. A. Hatamleh, H. Tarazi, and B. Tiwari. “Ai-Driven Novel Approach for Liver Cancer Screening and Prediction Using Cascaded Fully Convolutional Neural Network.” J Healthc Eng 2022 (2022): 4277436. [CrossRef]

- Mokrane, F. Z., L. Lu, A. Vavasseur, P. Otal, J. M. Peron, L. Luk, H. Yang, S. Ammari, Y. Saenger, H. Rousseau, B., Zhao, L. H. Schwartz, L. Dercle. “Radiomics Machine-Learning Signature for Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Cirrhotic Patients with Indeterminate Liver Nodules.” Eur Radiol 30, no. 1 (2020): 558-70. [CrossRef]

- Hamm, C. A., C. J. Wang, L. J. Savic, M. Ferrante, I. Schobert, T. Schlachter, M. Lin, J. S. Duncan, J. C. Weinreb, J. Chapiro, and B. Letzen. “Deep Learning for Liver Tumor Diagnosis Part I: Development of a Convolutional Neural Network Classifier for Multi-Phasic Mri.” Eur Radiol 29, no. 7 (2019): 3338-47. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. K., George, B., and V. Rai. “Artificial Intelligence to Decode Cancer Mechanism: Beyond Patient Stratification for Precision Oncology.” Front Pharmacol 11 (2020): 1177. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H., Y. Long, R. Han, W. Wang, L. Xu, M. Liao, Z. Zhang, Z. Wu, X. Shang, X. Li, J. Peng, K. Yuan, and Y. Zeng. “Deep Learning-Based Classification and Mutation Prediction from Histopathological Images of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” Clin Transl Med 10, no. 2 (2020): e102. [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A., B. Uyumazturk, P. Rajpurkar, A. Wang, R. Gao, E. Jones, Y. Yu, C. P. Langlotz, R. L. Ball, T. J. Montine, B. A., Martin, G. J. Berry, M. G., Ozawa, F. K., Hazard, R. A. Brown, S. B. Chen, M. Wood, L. S. Allard, L. Ylagan, A. Y. Ng, and J. Shen. “Impact of a Deep Learning Assistant on the Histopathologic Classification of Liver Cancer.” NPJ Digit Med 3 (2020): 23. [CrossRef]

- Verghese, G., J. K. Lennerz, D. Ruta, W. Ng, S. Thavaraj, K. P. Siziopikou, T. Naidoo, S. Rane, R. Salgado, S. E. Pinder, and A. Grigoriadis. “Computational Pathology in Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Prediction - Present Day and Prospects.” J Pathol 260, no. 5 (2023): 551-63.

- Hosseini, M. S., B. E. Bejnordi, V. Q. Trinh, L. Chan, D. Hasan, X. Li, S. Yang, T. Kim, H. Zhang, T. Wu, K. Chinniah, S. Maghsoudlou, R. Zhang, J. Zhu, S., Khaki, A., Buin, F., Chaji, A., Salehi, B. N. Nguyen, D., Samaras, K. N. Plataniotis. “Computational Pathology: A Survey Review and the Way Forward.” J Pathol Inform 15 (2024): 100357. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Hosen, M. I., Ahmed, M., and H. U. Shekhar. “Onco-Multi-Omics Approach: A New Frontier in Cancer Research.” Biomed Res Int 2018 (2018): 9836256. [CrossRef]

- Gulfidan G., Soylu M., Demirel D. B.. Erdonmez, H. Beklen, P. Ozbek Sarica, K. Y. Arga, and B. Turanli. “Systems Biomarkers for Papillary Thyroid Cancer Prognosis and Treatment through Multi-Omics Networks.” Arch Biochem Biophys 715 (2022): 109085. [CrossRef]

- Weberpals, J. I., T. J. Pugh, P. Marco-Casanova, G. D. Goss, N. Andrews Wright, P. Rath, J. Torchia A, Fortuna G.. Jones, M. P. Roudier, L. Bernard, B. Lo, D. Torti, A. Leon, K. Marsh, D. Hodgson, M. Duciaume, W. J. Howat, N. Lukashchuk, S. E. Lazic, D. Whelan and H. S. Sekhon. “Tumor Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Immune Profiling Characterizes Differential Response to First-Line Platinum Chemotherapy in High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer.” Cancer Med 10, no. 9 (2021): 3045-58.

- Thompson, B., and N. Petrić Howe. “Alphafold 3.0: The Ai Protein Predictor Gets an Upgrade.” Nature (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, B., and P. Bradley. “Advances in Protein Structure Prediction and Design.” Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, no. 11 (2019): 681-97. [CrossRef]

- Desai, D., S. V. Kantliwala, J. Vybhavi, R. Ravi, H. Patel, and J. Patel. “Review of Alphafold 3: Transformative Advances in Drug Design and Therapeutics.” Cureus 16, no. 7 (2024): e63646. [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R., M. Zhang, Y. Liu, and H. Jang. “Alphafold, Allosteric, and Orthosteric Drug Discovery: Ways Forward.” Drug Discov Today 28, no. 6 (2023): 103551. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X., H. Li, G. Ver Steeg, and A. Godzik. “Advances in Ai for Protein Structure Prediction: Implications for Cancer Drug Discovery and Development.” Biomolecules 14, no. 3 (2024). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).