1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the deadliest cancers worldwide. Its incidence has increased over the last few decades, making it the third leading cause of cancer-related death [

1]. The pathogenesis of HCC involves multi-step molecular changes at both the somatic genomic and epigenetic levels. Knowledge of its molecular mechanisms has expanded rapidly, driven by the development of novel high-throughput technologies such as the next generation sequencing over the past decade [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, most prevalent mutational drivers in HCC remain undruggable [

2,

4]. Furthermore, the application of molecular pathogenesis knowledge to guide precision diagnosis and systemic therapies for patients is still under investigation [

2]. As a result, HCC patients still have a very poor prognosis. To date, only two first-line drugs, sorafenib and lenvatinib, have been approved by the FDA for HCC treatment [

4]. Although advanced therapies are being developed rapidly, there is a pressing need for more effective therapeutic strategies to address this unmet clinical challenge.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a reversible cellular process in which epithelial cells lose their characteristics and acquire mesenchymal traits. During EMT, cells activate families of EMT-associated transcription factors, such as Snail/Slug family and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which enable increased cellular migration [

6,

7]. Cells can transiently or stably acquire various intermediate states between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes (partial EMTs) or undergo a complete EMT, depending on cell type and context. EMT is an evolutionary conserved process involved in both normal development and pathological conditions, including tumour cell migration and invasion [

6,

8]. It is considered the initial step in the metastatic cascade of cancer, which can be triggered by inflammation, carcinogens or specific features of the local microenvironment in primary tumour [

7,

9]. Recent studies have shown that loss of the epithelial phenotype through EMT promotes the acquisition of stem-like traits and resistance to anticancer drugs in carcinoma cells [

10]. As such, targeting EMT has emerged as an attractive therapeutic approach, offering potential new avenues for cancer treatment.

The EMT process involves the activation of multiple signalling pathways, including the Notch pathway. The Notch signalling pathway is highly conserved in metazoan species. Both ligands (Jagged1, Jagged2, DLL1 and DLL4) and receptors (Notch1-4) are single-pass transmembrane proteins, and activation occurs through interactions between neighbouring cells. Upon ligand binding, Notch receptors are cleaved by ADAM family metalloproteases and γ-secretase subsequently, releasing the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) [

11]. The NICD translocates to the nucleus, where it recruits coactivators to regulate the expression of transcriptional regulators such as Hes Family BHLH Transcription Factor (HES) and Hes-Related Family BHLH Transcription Factor with YRPW Motif (HEY) families. The HEY family consists of three members (HEY1, HEY2 and HEYL) in humans, which play critical roles in many developmental processes and the EMT pathway [

12]. Overexpression of HEY factors has been associated with advanced tumour progression and poor overall survival, and this has been mostly linked to EMT [

13]. HEY transcription factors are highly expressed in malignant carcinomas, such as osteosarcoma [

14]. Specially, HEY1 has been reported to be upregulated in 42.6% of HCC tumours in a cohort of 58 samples [

15] and in 72.4% of cases in an expanded in-house cohort of 87 HCC patients [

13]. HEY1 has also been implicated in regulating EMT in various cell types, making it a promising therapeutic target [

12,

14]. Inhibiting HEY1 has thus been proposed as a novel therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

Azvudine (FNC), also known as 2’-deoxy-2’-β-fluoro-4’-azidocytidine, is a novel cytidine analogue initially developed for treating Hepatitis C virus [

16,

17]. It has been clinically applied in the treatment of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 infectious due to its antiviral activity [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Recent studies have demonstrated that FNC exhibits antitumour activity in various cell lines and xenograft animal models [

17,

22,

23,

24]. In various cancer cell lines, such as B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and lung adenocarcinoma, FNC has shown significant effects in suppressing cell proliferation and tumour growth [

22,

23,

25]. Additionally, FNC demonstrated an inhibition activity in adhesion, migration and invasion of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and non-small lung cancer cell lines [

22,

24]. Recently, FNC has been found to induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in Dalton’s lymphoma cells [

26,

27].

Nucleoside analogues have been clinically utilized for over 50 years and remain a cornerstone of cancer treatment [

28,

29,

30]. In HCC studies, nucleoside analogues showed significant efficacy in treating patients with chronic HBV infections[

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of FNC in HCC and elucidate its molecular mechanisms in inhibiting the EMT process in liver cancer cells. This could provide critical insights into its potential application in HCC treatment, particularly in inhibiting of tumour metastasis, which may offer significant implications of FNC such as concomitant therapy.

3. Discussion

FNC is a novel nucleotide analogue with antiviral and antitumour activities, which has been approved for the treatment of AIDS and COVID-19 [

17]. In previous studies, FNC have been associated with the invasion of lymphoma cell lines [

24] and the proliferation of various cancer cell lines [

23].

Extensive evidence has shown that EMT plays a vital role in tumour metastasis, particularly in relation to tumour cell migration and invasion [

9]. Previous studies have highlighted the plasticity between epithelial and mesenchymal states, where cancer cells are observed to be in the intermediate states along this spectrum [

38]. In this study, we examined various types of cancer cell lines and identified, for the first time, identified that FNC inhibits Huh7 cell migration and invasion in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 2F, G). We further investigated the effects of FNC on EMT-related biomarkers and demonstrated that the transcriptional and translational levels of MMP2 and N-cadherin were decreased, accompanied by an upregulation of E-cadherin at the transcriptional level, but not of the Vimentin and Snail (

Figure 3A, B). Decreased transcriptional levels of MMP1 and MMP9 were also observed in Huh7 cells after FNC treatment. The changes in MMPs may contribute to extracellular matrix remodelling, which could lead to the observed changes in cell shape (

Figure 2E). These findings suggest a partial inhibition of EMT in Huh7 cells upon FNC treatment. Thus, FNC shows potential as a therapeutic agent for HCC by inhibiting the EMT process.

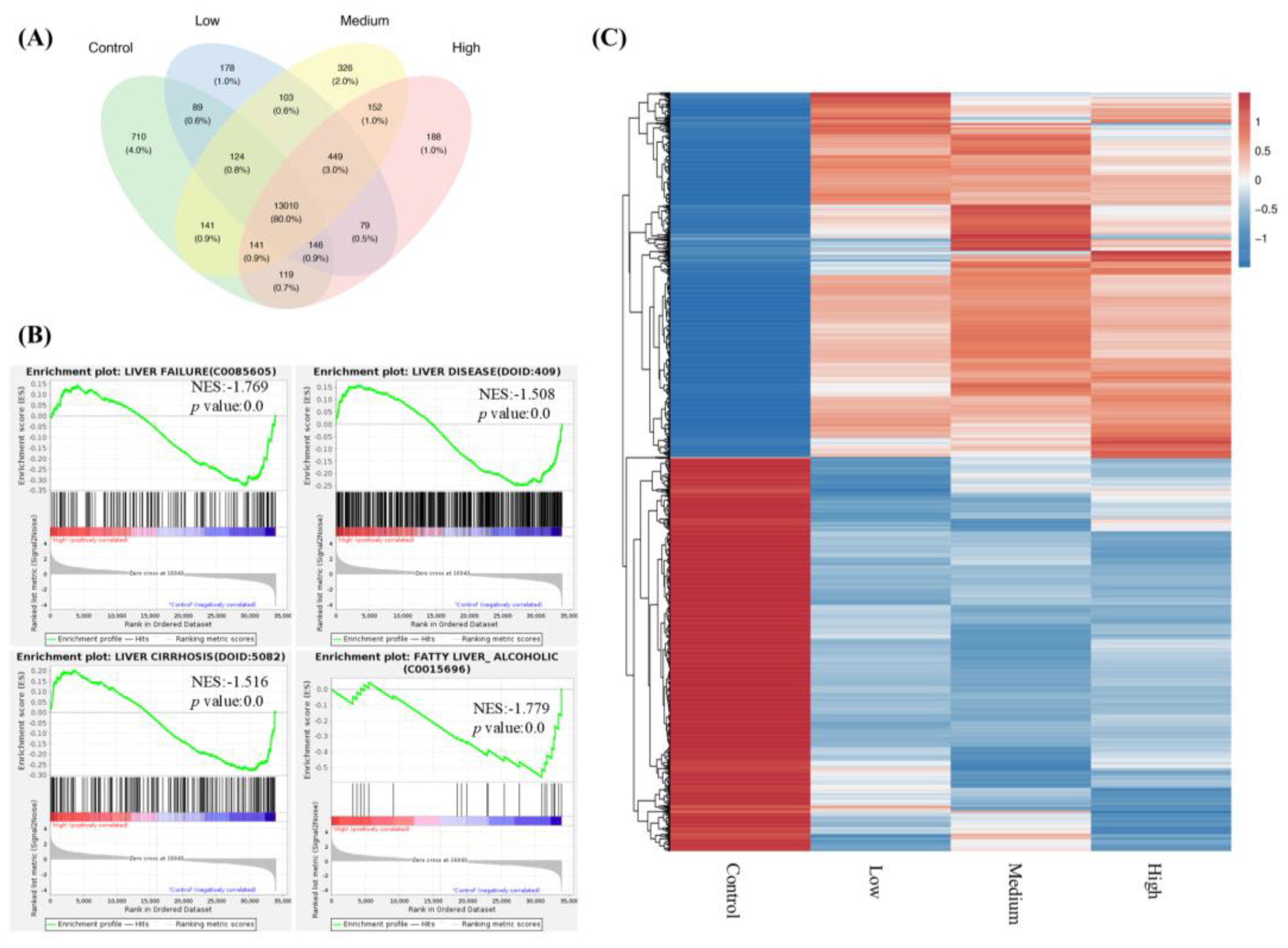

In RNA-seq experiments, we observed that FNC inhibits liver disease, liver failure, liver cirrhosis and fatty liver (alcoholic) gene sets by GSEA analysis (

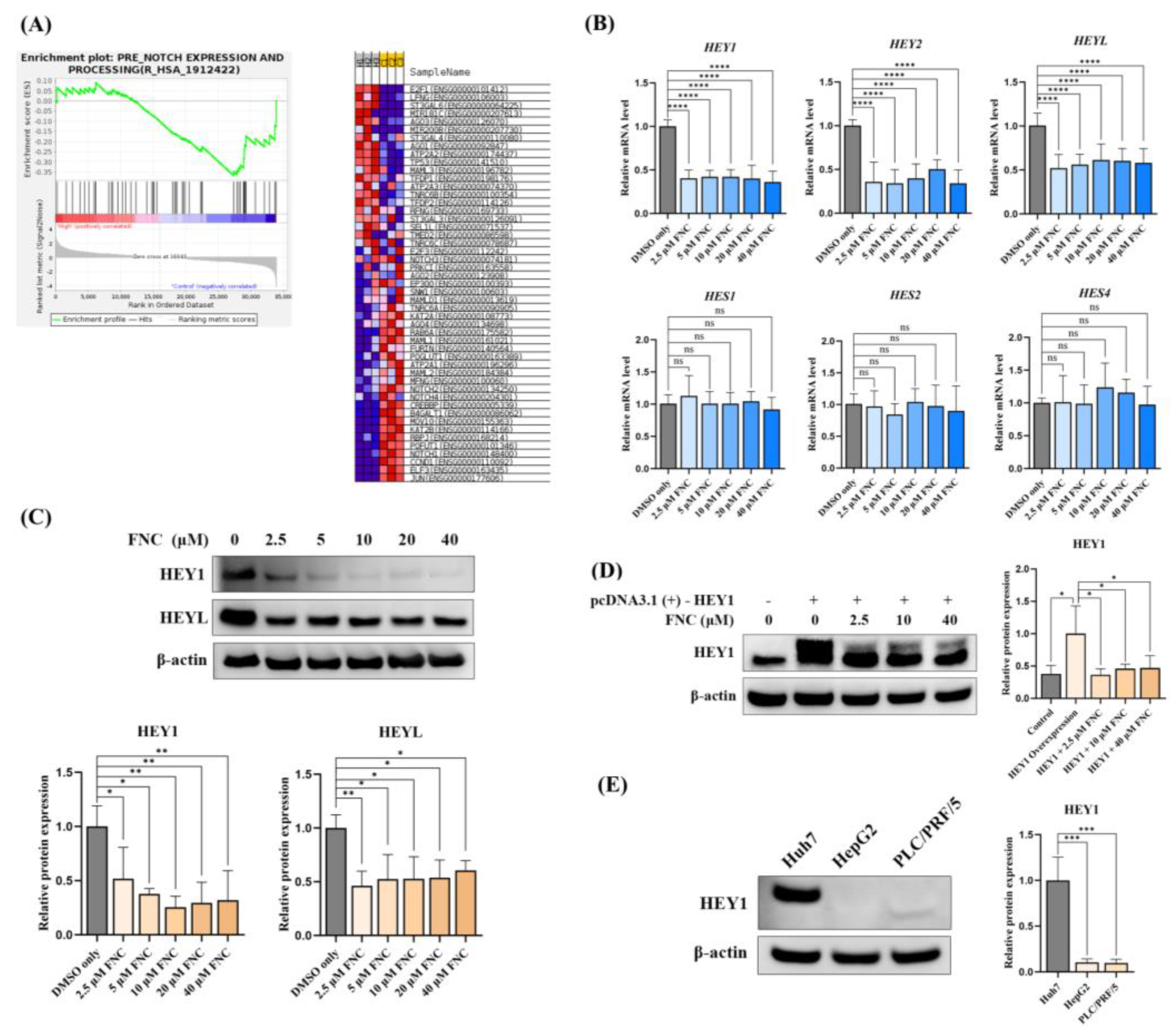

Figure 4B). Additionally, RNA-seq identified differential expression of genes related to the Notch signalling pathway, with q-PCR and Western Blotting confirming for a subset, suggesting HEY factors, including HEY1, HEY2 and HEYL, were inhibited by FNC (

Figure 5B, C). These results suggest that HEY factors may play important roles in the EMT inhibition process. The inhibitory effect of FNC was further validated through HEY1 overexpression experiments (

Figure 5D).

Previous studies have shown that HEY1 is an essential mediator of the TGF-β-induced EMT process in various cell types [

12]. Clinical studies have also reported high expression of HEY factors in various cancers, highlighting their roles in tumour metastasis, angiogenesis as well as proliferation [

37]. Furthermore, strong and growing evidence from clinical and basic research underscores the importance of HEY1 in liver cancer development [

13,

35,

37]. Therefore, HEY1 could potentially be an interesting clinical target for liver cancer treatment. In our study, we tested the effects of FNC on three different HCC cell lines and observed that it exhibited anti-EMT activity in Huh7 cells. This may be due to the different expression profiles of various HCC cell lines [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Given that HEY factors appear to be important targets of FNC in Huh7 cells, we further investigated whether different responses to FNC were related to varying HEY factor expression levels. Our results, supported by data from the Human Protein Atlas database, indicate that Huh7 have higher HEY1 expression levels compared to other tested cell lines, which may explain the observed anti-EMT effect of FNC on Huh7 cells (

Figure 5E) [

43,

44].

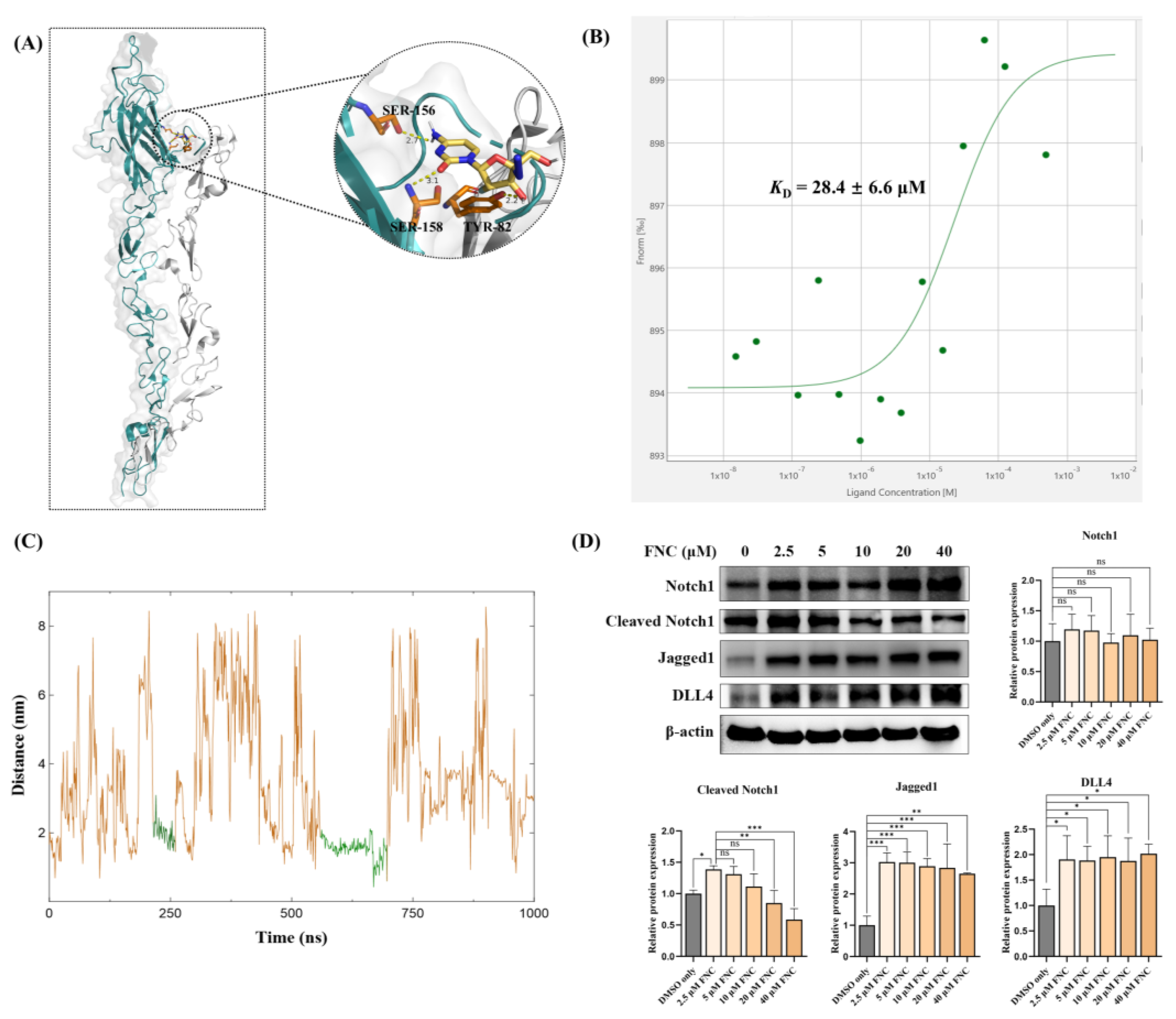

No significant changes were observed in expression levels of Notch ligands and receptors (

Figure 6D and

Figure 7). To explore the mechanism underlying HEY factors downregulation, molecular docking experiments were conducted to assess whether FNC binds to Notch ligands, potentially affecting ligand-dependent Notch activation. Notch ligands and receptors have large ectodomains, many of which have been widely studied due to their critical role for Notch activation [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In addition to direct ligand-receptor interactions, some regions regulate Notch activation indirectly, such as the C2 domain of Notch ligands modulate Notch signalling through their lipid-binding properties [

50,

51]. Previous studies suggested that conformational changes in ligands and receptors during binding are crucial for Notch activation [

48,

49]. Our MST and MD simulations data indicated that FNC can directly interact with Jagged1 (

Figure 6B, C). Molecular docking suggested that FNC might bind to the C2 domain of Jagged1, a critical domain for Notch activation due to its roles in Notch binding and lipid binding (

Figure 6A). Binding of FNC to Jagged1 may induce conformational changes that alter the binding affinity of Jagged1 to Notch receptors and lipids, subsequently reducing Notch receptor activation and HEY1 expression. This hypothesis was further supported by detecting cleaved Notch1 which reflects the level of Notch1 activation level in FNC-treated Huh7 cells (

Figure 6D). An increase in cleaved Notch1 was observed in Huh7 cells treated with 2.5 μM FNC compared to the DMSO only group, likely due to increased Notch ligand expression in FNC-treated samples (

Figure 6D and

Figure 7).

Although small molecule-protein interaction identification approaches offer novel ways to identify potential drug targets, they also have many limitations [

52]. MST is an in vitro assay using purified recombinant Jagged1-Fc protein constructs, although binding measurements were performed in solution mimicking natural conditions, we cannot determine the binding behaviour of FNC to Jagged1 on liver cell surfaces or within the human body. Additionally, while molecular docking and MD simulations identified potential binding sites for FNC on Jagged1, the complexity of the cell surface and tumour microenvironment, coupled with the partial use of Jagged1’s extracellular domain in analyses, limits our ability to determine the exact binding site in vivo.

Overall, our study provides novel insights into the potential of FNC for drug repurposing in hepatocellular carcinoma. We elucidated the mechanisms underlying FNC’s anti-EMT activity in HCC cell lines. Given its previously identified antiviral activities, including against Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV), FNC could be a valuable drug for HCC patients infected by HBV and HCV. Additionally, we demonstrated that FNC exerts its anti-EMT activity by inhibiting HEY1. Considering high expression of HEY1 in significant amount of HCC patients, FNC may be a useful drug for these patients. While our findings suggest that FNC binding to Jagged1 may explain the decrease in HEY1, further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying HEY1 downregulation at lower FNC concentrations. In conclusion, our data indicate that FNC reduces the invasive and migratory capabilities of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating Notch signalling and could have potential for therapeutic applications to treat hepatocellular carcinoma as well as Notch-associated disorders.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Reagents

The hepatocellular carcinoma cell line Huh7 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Huh7 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were starved in a medium containing 0.1% FBS for 24 hours prior to FNC treatment.

4.2. Cytotoxicity Assay

Inoculate 100 µL of Huh7 cell suspension with a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL into a 96-well plate for overnight pre-culture. Replace the culture medium with one containing different concentrations of FNC. After 48 hours, add 10 µL of CCK-8 solution (MedChemExpress, China) to each well. Incubate for 1-4 hours, then measure the absorbance of at 450nm wavelength using the plate reader (PerkinElmer 2030 multilabel Reader, VICTORTM X4).

(As = absorbance of the experimental well; Ac = absorbance of the control well; Ab = absorbance of the blank well)

4.3. Wound-Healing Assay

Confluent, serum-deprived monolayer cultures of Huh7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1.2 × 105 cells/mL. The cells were subjected to "wounding" by scratching the monolayer with a 10 µL plastic pipette tip. DMSO or varying concentrations of FNC were added to each well. After 24 and 48 hours, cell migration was evaluated by measuring the open wound areas. Images were captured using the ZEISS Axio observer A1 inverted phase contrast microscope and analysed with Image J software.

4.4. Invasion Assay

Invasive activity was measured using BD Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in a 24-well plate, following the manufacturer’s protocol. A total of 200 µL Huh7 cells in 0.1% FBS medium were seeded at a density of 0.8 × 104 cells/mL into the upper chamber. The bottom wells of the system were filled with 400 µL of 10% FBS culture medium. After incubation for 24 or 48 hours, the cells in the upper chamber were removed, and the cells on the bottom membrane were fixed and stained. The invading cells were counted in five random fields of the membrane. The invasion efficiency of the control cells was set as 100%.

4.5. RNA Sequencing

Huh7 cells were treated with 2.5 µM (low), 20 µM (medium) and 40 µM (high) FNC or DMSO only (control) for 48 hours, with three biological replicates prepared for each sample group. Cells were lysed using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and sent to Novogene Services (USA) for RNA library construction and sequencing. RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). All samples demonstrated a high RNA integrity number (RIN) index > 5, qualifying them for further analysis. The library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads.

Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 R package (1.20.0). Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 were classified as differentially expressed. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was conducted using DisGeNET datasets. Genes were ranked by the degree of differential expression between the two samples, and predefined gene sets were tested for enrichment at the top or bottom of the ranked list. Enrichment results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4.6. Western Blotting

Cells were washed with PBS before lysis in ice-cold lysis buffer (P0013C, Beyotime). Protein concentrations were measured using the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) after sample lysis. The lysates were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. The following antibodies were used: anti-β-actin (13E5, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-MMP2 (D4M2N, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-MMP9 (D6O3H, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-N-Cadherin (D4R1H, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-E-Cadherin (24E10, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-HEY1 (ab154077, Abcam), anti-HES1 (D6P2U, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Vimentin (D21H3, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Snail (C15D3, Cell Signaling Technology). Detection was performed using a chemiluminescence detection system (Bio-Rad ChemiDocTM).

4.7. Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from the Huh7 cell line was isolated using an RNA isolation kit (TransGen Biotech). Reverse transcription was performed with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems

TM). Reactions were run using a standard SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme) in 96-well plates (Applied Biosystems

TM) on an Analytik Jena qTOWER

3 RT-PCR system. The comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method was applied to determine the fold-change in mRNA expression with Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) used as a reference. Each sample was run in triplicate. All primers used in this study are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.8. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were grown in 6-well plates containing coverslips for 24 hours before being treated with 40 µM FNC or DMSO for 48 hours. After treatment, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS for 10 minutes on ice. The cells were then rinsed three times with PBS and blocked with 5% BCA for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were incubated with the indicated antibodies diluted in PBS overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally, the coverslips were placed onto slides using SlowFadeTM Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (InvitrogenTM). Samples were imaged using a Nikon Ti2U fluorescence microscope. The following antibodies were used: Phalloidin iFluorTM 488 (YEASEN).

4.9. MST

MST traces were generated using a Monolith NT.LabelFree instrument (Nano Temper Technologies) with the MO. Control v2.0.4 software. A full-length extracellular domain (C2 to EGF16, 1277-JG-050, R&D Systems) tagged with an Fc-tag (Jagged1-Fc), was expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Jagged1-Fc was dissolved in HEPES buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM CaCl2) to a concentration of 1 μM. FNC was serially diluted in HEPES buffer to a concentration ranging from 0.015 to 500 μM. Jagged1-Fc was then mexed 1:1 (v/v) with FNC. The mixtures were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. Samples were then transferred into LabelFree Premium Capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies) and analysed at 12% excitation power on the Monolith NT.LabelFree instrument at a constant temperature of 25 °C. The dissociation constant (KD) was determined as the average of three biological replicate values obtained using the MO.Control software.

4.10. Molecular Docking

Protein receptor structures were sourced from the RCSB Protein data bank (PDB). Protein macromolecules and the 3D structure of FNC were imported into AutoDock Tools 1.5.6. Water molecules were removed, hydrogens were added, and the structures were converted into PDBQT format. The grid box was configured to encompass the entire receptor region. Semi-flexible docking was performed using AutoDock Vina to evaluate the interaction forces between FNC and the protein receptors. The 3D conformation of the ligand-receptor complex was visualized using PyMOL 3.0.

4.11. MD Simulations

The three-dimensional structure of Jagged1 (PDB: 4CC1) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank. MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2020.6 software [

53,

54,

55], applying the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field [

56]. The small molecule was prepared using Sobtop [

57] to generate a GAFF force field, with force parameters for the azide structure calculated using the Hessian matrix. A cubic simulation cell, 0.8 nm larger than the FNC-Jagged1 complexes in all dimensions, was employed. Water molecules were modeled using the TIP3P model at a density of 1 kg/L, and the system was neutralized with Na

+ and Cl

- ions. The system’s temperature was gradually increased to 298.15 K over 500 ps. Free dynamic simulations were then conducted using the Verlet algorithm with a 0.002 ps integration time step. The simulations were performed in an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble at 298.15 K and 1 bar pressure, with temperature and pressure controlled using the V-rescale and Parrinello–Rahman methods, respectively. Periodic boundary conditions were applied throughout the simulations, and the duration was extended as needed.

Root mean squared deviation (RMSD) values were calculated to assess the Jagged1–FNC interactions. MD trajectories were visualized using VMD software version 1.9.4. The binding free energy of the Jagged1–FNC complex was calculated using the gmx_MMPBSA package, employing the molecular mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) method.

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 10 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Experiments were performed at least three times, and data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), unless otherwise stated. P-values were calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test to analyse differences between each pair of groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For RNA-seq analysis, the resulting P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M., P.S., Xinyi Y., Z.Z. and Xuefu Y.; data curation, Y.M., P.S., Y.R., X.L. and L.D.; resources, Z.Z., G.L., C.X. and H.L.; formal analysis, Y.M. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M., P.S. and Xinyi Y.; writing—review and editing, Xinyi Y., Xuefu Y. and Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Impacts of FNC on cell invasion of various HCC cell lines. Three independent experiments were conducted, and representative images captured at 24 hours are presented. 10 μM FNC significantly inhibited cell invasion in Huh7 cells, but not in HepG2 or PLC/PRF/5 cells. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. ns, no significant difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Figure 1.

Impacts of FNC on cell invasion of various HCC cell lines. Three independent experiments were conducted, and representative images captured at 24 hours are presented. 10 μM FNC significantly inhibited cell invasion in Huh7 cells, but not in HepG2 or PLC/PRF/5 cells. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. ns, no significant difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Figure 2.

The cytotoxicity, anti-migration and anti-invasion effects of FNC. (A-C) Cytotoxicity assay results demonstrating the effects of FNC on Huh7 (A), HepG2 (B) and PLC/PRF/5 (C) cells. HCC cells were treated with varying concentrations of FNC or DMSO for 48 hours, and cell viability was analysed using a CCK-8 colorimetric assay. The orange dotted line indicates the IC50 (the concentration at which 50% inhibition occurs). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D) The chemical structure of FNC. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy images of Huh7 cells treated with DMSO (control) or 40 μM FNC. Cells were stained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei and Phalloidin (green) to stain actin filaments. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar: 100 µm. (F) Effect of FNC on the mobility of Huh7 cells. Representative images of the wound healing assay at 0, 24 and 48 hours are shown. Values are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Inhibitory effect of FNC on Huh7 cell invasion. Three independent experiments were performed, and representative images at 24 and 48 hours are shown. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Figure 2.

The cytotoxicity, anti-migration and anti-invasion effects of FNC. (A-C) Cytotoxicity assay results demonstrating the effects of FNC on Huh7 (A), HepG2 (B) and PLC/PRF/5 (C) cells. HCC cells were treated with varying concentrations of FNC or DMSO for 48 hours, and cell viability was analysed using a CCK-8 colorimetric assay. The orange dotted line indicates the IC50 (the concentration at which 50% inhibition occurs). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D) The chemical structure of FNC. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy images of Huh7 cells treated with DMSO (control) or 40 μM FNC. Cells were stained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei and Phalloidin (green) to stain actin filaments. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar: 100 µm. (F) Effect of FNC on the mobility of Huh7 cells. Representative images of the wound healing assay at 0, 24 and 48 hours are shown. Values are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Inhibitory effect of FNC on Huh7 cell invasion. Three independent experiments were performed, and representative images at 24 and 48 hours are shown. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Figure 3.

FNC alters a subset of EMT markers in Huh7 cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis showing the expression levels of EMT markers, including N-Cadherin, E-Cadherin, MMP2, Snail and Vimentin, in Huh7 cells after 48 hours of FNC treatment. Only DMSO was used to treat the control group. β-actin was used as a loading control. A representative blot from three independent experiments is shown. Protein expression levels were analysed using ImageJ and are presented as the mean ± SD. ns, no significant difference; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ****P ≤ 0.0001. (B) Expression levels of EMT marker genes relative to GAPDH in Huh7 cells, analyse by real-time PCR. Values are presented together with the mean ± SD. ns, no significant difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 3.

FNC alters a subset of EMT markers in Huh7 cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis showing the expression levels of EMT markers, including N-Cadherin, E-Cadherin, MMP2, Snail and Vimentin, in Huh7 cells after 48 hours of FNC treatment. Only DMSO was used to treat the control group. β-actin was used as a loading control. A representative blot from three independent experiments is shown. Protein expression levels were analysed using ImageJ and are presented as the mean ± SD. ns, no significant difference; *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ****P ≤ 0.0001. (B) Expression levels of EMT marker genes relative to GAPDH in Huh7 cells, analyse by real-time PCR. Values are presented together with the mean ± SD. ns, no significant difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Figure 4.

FNC significantly altered the transcriptional profile of Huh7 cells. (A) Venn diagram showing the number of genes identified across different sets of RNA-Seq data comparisons. The green area represents genes from the control group (Huh7 cells treated with DMSO for 48 hours). The blue, yellow and pink areas represent genes from Huh7 cells treated with 2.5 μM (low), 20 μM (medium), 40 μM (high) FNC, respectively. Numbers in the overlapping regions indicate gene numbers shared between multiple groups. (B) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showing significant enrichment of liver disease and liver failure gene sets in the control group compared to Huh7 cells treated with 40 μM FNC. The GSEA enrichment plots illustrate the distribution of the enrichment score (green line) across genes associated with the respective disease (vertical black lines), ranked by their anti-disease activity (left to right). Liver failure (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.769), liver disease (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.508), liver cirrhosis (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.516) and fatty liver (alcoholic) (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.779) were identified as significantly enriched targets. (C) Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in the control, low, medium and high groups of Huh7 cells. The heatmap uses a color scale relative to each gene (each row) with blue representing the lowest expression and red indicating the highest expression.

Figure 4.

FNC significantly altered the transcriptional profile of Huh7 cells. (A) Venn diagram showing the number of genes identified across different sets of RNA-Seq data comparisons. The green area represents genes from the control group (Huh7 cells treated with DMSO for 48 hours). The blue, yellow and pink areas represent genes from Huh7 cells treated with 2.5 μM (low), 20 μM (medium), 40 μM (high) FNC, respectively. Numbers in the overlapping regions indicate gene numbers shared between multiple groups. (B) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showing significant enrichment of liver disease and liver failure gene sets in the control group compared to Huh7 cells treated with 40 μM FNC. The GSEA enrichment plots illustrate the distribution of the enrichment score (green line) across genes associated with the respective disease (vertical black lines), ranked by their anti-disease activity (left to right). Liver failure (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.769), liver disease (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.508), liver cirrhosis (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.516) and fatty liver (alcoholic) (p value = 0.0; NES = -1.779) were identified as significantly enriched targets. (C) Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in the control, low, medium and high groups of Huh7 cells. The heatmap uses a color scale relative to each gene (each row) with blue representing the lowest expression and red indicating the highest expression.

Figure 5.

FNC inhibits the expression of HEY factors in Huh7 cell lines. (A) Enrichment plots showing changes in the Notch expression and processing gene set after FNC treatment in Huh7 cells. (B) Total RNA was collected from Huh7 cells and analysed using real-time PCR after 48 hours of FNC treatment. The control group was treated with DMSO only. A comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) analysis was performed to calculate fold changes in mRNA expression relative to GAPDH. The experiment was independently performed in triplicate. (C) Protein expression levels of HEY1 and HEYL were analysed by western blot after 48 hours of FNC treatment at the indicated concentrations. β-actin was used as a loading control. Three independent experiments were performed, and a representative blot is shown. ****P ≤ 0.0001. (D) HEY1 with a C-terminal Myc tag was overexpressed in Huh7 cells, followed by treating with 2.5, 10 or 40 μM FNC. Three independent experiments were performed, and data are presented as mean ± SD. (E) HEY1 expression levels in Huh7, HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells were detected by Western Blotting. Three independent experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Figure 5.

FNC inhibits the expression of HEY factors in Huh7 cell lines. (A) Enrichment plots showing changes in the Notch expression and processing gene set after FNC treatment in Huh7 cells. (B) Total RNA was collected from Huh7 cells and analysed using real-time PCR after 48 hours of FNC treatment. The control group was treated with DMSO only. A comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) analysis was performed to calculate fold changes in mRNA expression relative to GAPDH. The experiment was independently performed in triplicate. (C) Protein expression levels of HEY1 and HEYL were analysed by western blot after 48 hours of FNC treatment at the indicated concentrations. β-actin was used as a loading control. Three independent experiments were performed, and a representative blot is shown. ****P ≤ 0.0001. (D) HEY1 with a C-terminal Myc tag was overexpressed in Huh7 cells, followed by treating with 2.5, 10 or 40 μM FNC. Three independent experiments were performed, and data are presented as mean ± SD. (E) HEY1 expression levels in Huh7, HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells were detected by Western Blotting. Three independent experiments were performed. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Figure 6.

FNC interacts with Jagged1. (A) The interaction between FNC and Jagged1 (teal) as proposed by molecular docking. Notch1 (grey) was modelled onto the Jagged1 structure based on the Jagged1-Notch1 complex structure (PDB: 5UK5). Hydrogen bond interactions with residues on the C2 domain are shown. (B) Binding of FNC to Jagged1-Fc is quantified in HEPES buffer. FNC was titrated at concentrations ranging from 0.015 to 500 μM, while the concentration of Jagged1-Fc was kept constant at 1 μM. A representative MST binding curve is shown. The KD value is the average of triplicate measurements. (C) MD simulation of the Jagged1-FNC complex over a 1000 ns simulation. The MD trajectories show the protein-to-drug center-of-mass distance. The green trajectories represent relatively stable confirmations, indicating relatively consistent interactions between Jagged1 and FNC. (D) Jagged1, DLL4, Notch1 and cleaved Notch1 was detected by immunoblotting. Three independent experiments were performed, and data were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with comparisons to the mean of the 2.5 μM FNC-treated sample. ns, no significant difference; *P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Figure 6.

FNC interacts with Jagged1. (A) The interaction between FNC and Jagged1 (teal) as proposed by molecular docking. Notch1 (grey) was modelled onto the Jagged1 structure based on the Jagged1-Notch1 complex structure (PDB: 5UK5). Hydrogen bond interactions with residues on the C2 domain are shown. (B) Binding of FNC to Jagged1-Fc is quantified in HEPES buffer. FNC was titrated at concentrations ranging from 0.015 to 500 μM, while the concentration of Jagged1-Fc was kept constant at 1 μM. A representative MST binding curve is shown. The KD value is the average of triplicate measurements. (C) MD simulation of the Jagged1-FNC complex over a 1000 ns simulation. The MD trajectories show the protein-to-drug center-of-mass distance. The green trajectories represent relatively stable confirmations, indicating relatively consistent interactions between Jagged1 and FNC. (D) Jagged1, DLL4, Notch1 and cleaved Notch1 was detected by immunoblotting. Three independent experiments were performed, and data were assessed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with comparisons to the mean of the 2.5 μM FNC-treated sample. ns, no significant difference; *P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Figure 7.

Effects of FNC on transcription levels of Notch ligands and receptors. Q-PCR analysis was performed to evaluate the transcription levels of Jagged1, Jagged2, DLL4, Notch1, Notch3 and Notch4 in Huh7 cells treated with 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM FNC. Significant upregulation of Jagged1 and DLL4 mRNA levels were observed. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Figure 7.

Effects of FNC on transcription levels of Notch ligands and receptors. Q-PCR analysis was performed to evaluate the transcription levels of Jagged1, Jagged2, DLL4, Notch1, Notch3 and Notch4 in Huh7 cells treated with 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM FNC. Significant upregulation of Jagged1 and DLL4 mRNA levels were observed. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Binding interactions and energies between Notch ligands and FNC as proposed by molecular docking.

Table 1.

Binding interactions and energies between Notch ligands and FNC as proposed by molecular docking.

| Protein * |

Residue |

Binding Mode |

Binding Energy

(kcal/mol) |

| Jagged1 |

TYR 82 |

H-Bond |

-6.592 |

| SER 156 |

H-Bond |

| SER 158 |

H-Bond |

| VAL 86 |

Pi-A |

| Jagged2 |

SER 204 |

SER 204 |

-6.506 |

| ARG 114 |

ARG 114 |

| CYS 198 |

CYS 198 |

| ASP 176 |

ASP 176 |

| TYR 203 |

TYR 203 |

| DLL1 |

HIS 182 |

H-Bond |

-5.707 |

| ASP 180 |

H-Bond |

| TYR 183 |

H-Bond |

| GLY 185 |

H-Bond |

| CYS 179 |

Hal/Pi-S |

| DLL4 |

GLN 153 |

H-Bond |

-6.058 |

| CYS 175 |

H-Bond |

| GLY 181 |

H-Bond |

| ASP 182 |

H-Bond/Attr-Chg |

| PRO 202 |

C-H Bond |