Introduction

As the proportion of aging populations increases, greater attention is being paid to the health issues associated with aging [

1]. Among these, chronic pain is particularly significant due to its profound impact on physical, mental, and social aspects of life. Persistent pain in the elderly can lead to cognitive decline, exacerbate social isolation, and significantly reduce quality of life [

2]. Effective pain management is crucial not only to alleviate individual suffering but also to maintain patients’ independence, social connections, and overall well-being [

3]. Given the complex etiology of chronic pain, its management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, encompassing pharmacological therapy, physiotherapy, psychotherapy, and lifestyle modifications [

4]. This paper explores the specific characteristics of pain in older adults, diagnostic and therapeutic options, and relevant guidelines.

Types of Pain

Pain can be categorized into acute and chronic pain. Acute pain is a short-term response to injury, tissue damage, or disease. It typically begins suddenly and lasts for a few days to weeks. Acute pain is often associated with a clear cause, such as a wound, fracture, infection, or surgery. Its primary function is to act as a warning signal, prompting protective behavior to avoid further harm [

5]. In contrast, chronic pain persists for more than three months and often lacks a clear physiological cause. Chronic pain is frequently multifactorial and can have long-term detrimental effects on patients’ quality of life [

6]. Common types of chronic pain include: osteoarthritis pain: caused by joint degeneration and inflammation, highly prevalent in older adults. Neuropathic pain: Arises from nerve damage or injury, often characterized by burning, numbness, or stabbing sensations. Cancer-related pain: frequently intense and challenging to manage. Fibromyalgia: manifests as widespread muscle and connective tissue pain, often accompanied by fatigue and sleep disturbances. Chronic low back pain: results from spinal degeneration or other causes, leading to significant mobility limitations. Visceral pain: stems from chronic pain in internal organs, such as the abdomen or pelvis, and is often difficult to diagnose [

1].

Why Focus on Older Adults?

This review focuses on older adults as a population disproportionately affected by chronic pain. Chronic pain is significantly more prevalent among older adults compared to younger individuals. Additionally, the perception, experience, and response to pain and its consequences vary distinctly in this population. Chronic pain profoundly influences the social circumstances, quality of life, psychological well-being, and cognitive functions of older adults.

Prevalence of Chronic Pain in Older Adults

Chronic pain is more prevalent among older adults compared to younger populations. Among those aged 65 and older, the prevalence ranges from 50% to 85%, compared to 15% to 30% in younger adults [

7]. National and European surveys underscore chronic pain as a major health issue in the elderly, with rates potentially three times higher than in younger populations. The risk of chronic pain increases with age and comorbidities, such as cancer, diabetes and peripheral neuropathy. Additionally, diminished pain perception in conditions like coronary artery disease can lead to diagnostic challenges. These findings highlight the importance of effective pain management for individual well-being and healthcare systems.

Psychological Changes and Cognitive Decline

Conditions such as depression and anxiety, which are more common in older adults, can amplify the subjective experience of pain. Social isolation, loneliness, and a lack of environmental stimulation can further exacerbate the perception of pain.

Chronic pain in older adults is closely linked to cognitive decline. Studies indicate that persistent pain can impair memory, attention, and executive functions. Chronic pain can lead to structural and functional changes in the brain, including reduced hippocampal volume and overactivation of pain-processing areas such as the anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortices. These changes contribute to cognitive overload and decreased resilience.

Sleep disturbances, often associated with chronic pain, exacerbate cognitive decline by impairing memory consolidation and concentration. Psychosocial factors, including reduced activity levels and social isolation, also accelerate cognitive decline. Multidisciplinary pain management approaches that incorporate psychological support, physical activity, and improved sleep quality are crucial in mitigating these effects.

Pain Perception

Pain perception is a complex process initiated by nociceptors, the sensory receptors for pain. These receptors are the endings of sensory nerves, responding to various stimuli such as temperature changes, pressure, or chemical signals. Once detected by nociceptors, pain signals are transmitted through different levels of the nervous system—peripheral nerves, the spinal cord, and the brain. The brain is where both the sensation and emotional response to pain are processed, involving key centres like the thalamus and the limbic system.

In older adults, pain perception and processing undergo several changes. Age-related alterations in the central nervous system, such as a reduction in the number of neurons and slower neural conduction, can influence pain sensitivity. Moreover, the responses to pain may differ due to changes in neural pathways and neurotransmitter function. As a result, older individuals may experience heightened or diminished pain sensations, with differences in how pain is processed compared to younger populations.

Changes in Pain Perception with Aging

Physiological changes associated with aging significantly affect the perception and management of chronic pain in older adults. For instance, the peripheral nervous system experiences a decline in the number and function of nociceptors, potentially altering pain sensitivity. Consequently, older individuals may exhibit reduced or atypical responses to certain pain stimuli, complicating pain recognition and treatment. Research has consistently shown decreased sensitivity to lower pain intensities in aging populations [

8].

The central nervous system also undergoes significant age-related changes, such as a reduction in neuronal density, disruptions in neurotransmitter balance, and functional decline in brain structures like the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which are critical for pain processing. These changes can contribute to both heightened pain sensitivity and diminished pain responses.

Psychosocial factors play a crucial role in pain perception among older adults. Cognitive decline, particularly in memory and attention, can hinder accurate pain recognition and communication, complicating medical interventions. Additionally, depression and anxiety, common in this age group, can amplify the subjective experience of pain and its intensity.

Challenges in Pain Management for Older Adults

Pharmacological pain management presents unique challenges in older adults, as they are more susceptible to the side effects of analgesics like opioids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory increasing the risk of adverse effects such as sedation, confusion, or constipation.

Non-pharmacological strategies, including physiotherapy, cognitive-behavioural therapy, and lifestyle modifications (e.g., increased physical activity), can also be effective. These approaches not only reduce pain but also enhance the overall quality of life for older patients. Effective pain management for older adults requires a comprehensive approach that addresses biological, psychological, and social factors [

9].

Pain Assessment in Older Adults

Assessing pain in older adults is particularly challenging due to its subjective nature, influenced by individual perception, prior experiences, and psychological state. Pain is a subjective experience shaped by multiple factors, including age, psychological status, and prior encounters with pain. Since there is no objective tool that can precisely measure pain intensity, clinicians must rely entirely on the patient’s subjective accounts. This approach underscores the principle that the patient’s report is always valid; if someone reports experiencing pain, it is a genuine experience for them, even if environmental or medical evaluations do not clearly corroborate it.

Recognizing the subjective nature of pain is crucial for its management. The patient’s feelings and descriptions must be considered to design an individualized treatment plan. Pain is not merely a reflection of physical condition but also involves a psychosocial dimension that significantly influences its perception and impact. Effective management requires addressing this multidimensional nature of pain, ensuring that both its physical and psychosocial aspects are considered.

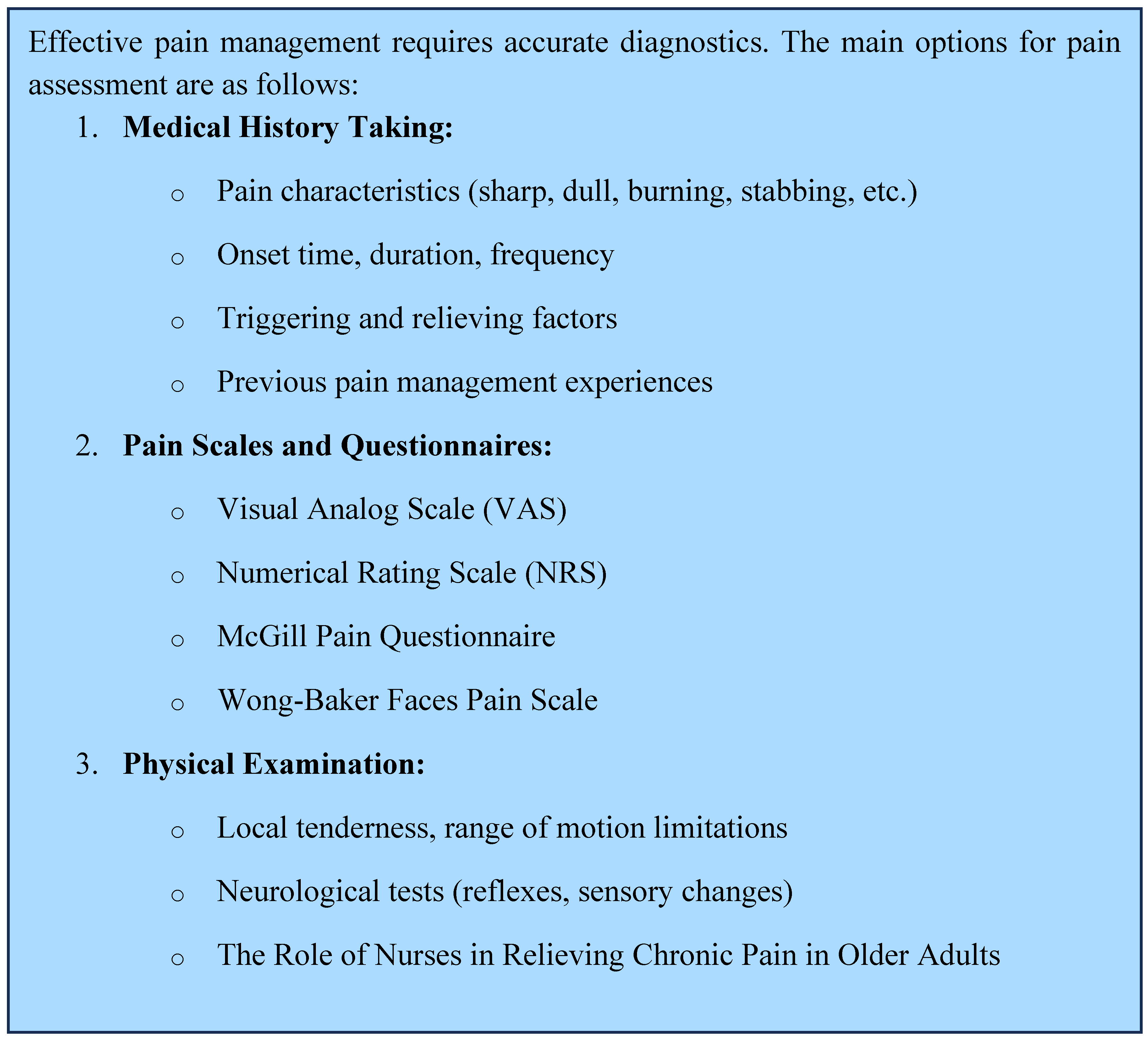

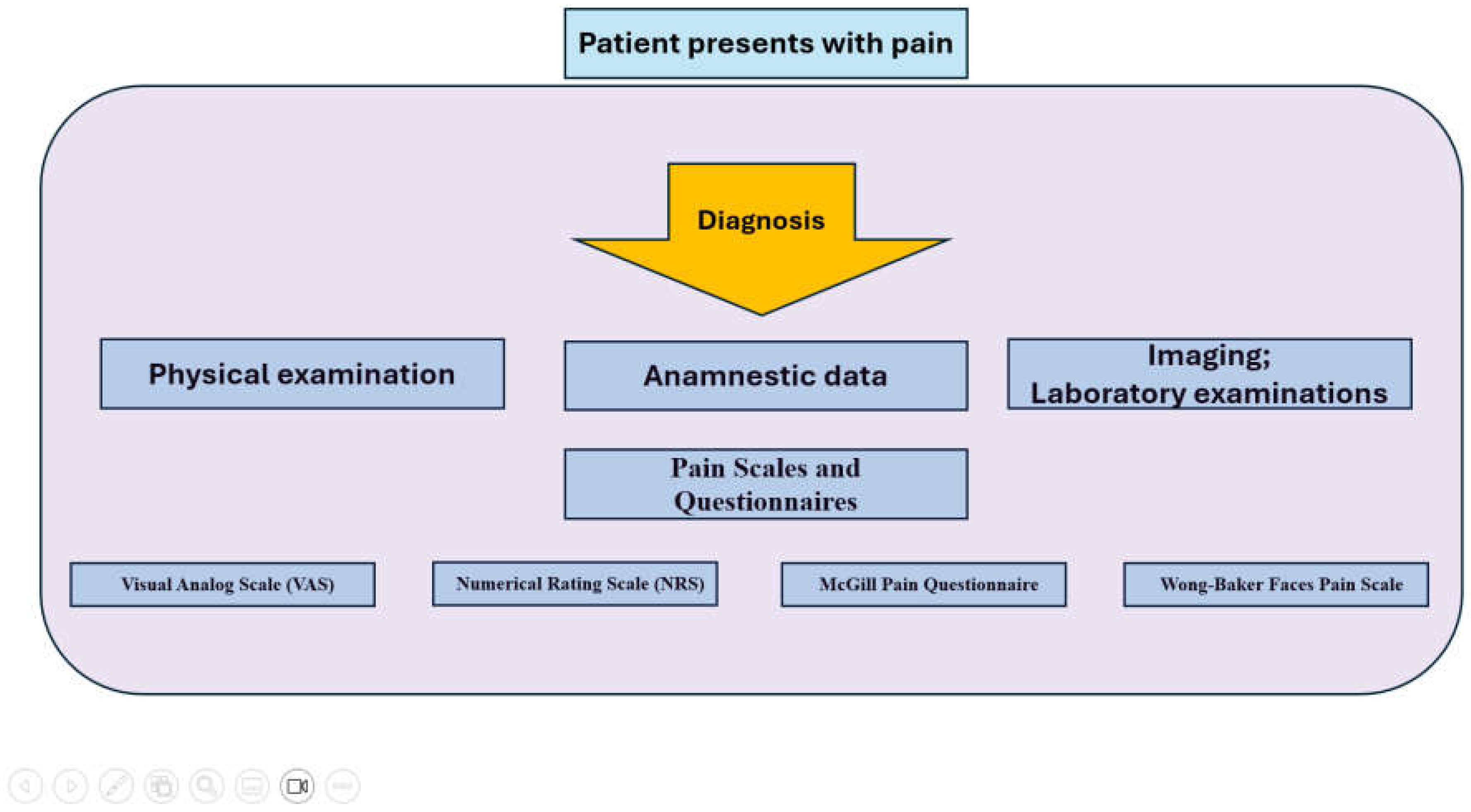

Pain assessment is a multifaceted process that requires various methods due to the subjective nature of pain [

10]. Self-reporting remains the most common approach, where patients describe their pain verbally or through visual tools. This method is highly effective as it directly relies on the patient’s experience, providing invaluable information due to the subjective nature of pain. Verbal scales, such as the 0-to-10 numeric rating scale, are simple and quick to administer [

11]. However, the accuracy of self-reporting may decrease in older patients, particularly those with cognitive impairments [

12]. Visual analogue scales (VAS), where patients mark their pain level on a continuum, offer an alternative. These are easily understood and efficient, particularly for assessing acute pain and tracking its changes over time. Nevertheless, they may pose challenges for individuals with motor or visual deficits, limiting their applicability in elderly or physically debilitated patients.

Observational scales are especially useful in cases where patients cannot communicate. For instance, the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale evaluates pain based on observable indicators such as facial expressions, vocalizations, body posture, or activity levels. Although these methods are inherently subjective, they play a critical role for caregivers and family members in identifying pain in patients with dementia or severe cognitive decline [

13]. Observations made by nurses or family members are vital for classifying pain-related behaviours and tailoring appropriate interventions.

Various studies have explored the effectiveness of different pain assessment methods. Physiological markers, such as changes in heart rate, blood pressure, or cortisol levels, are well-documented responses to pain, though other stress factors can influence these indicators. Emerging technologies, such as electroencephalography (EEG) and functional imaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), offer new possibilities for pain measurement. However, their high costs and limited accessibility currently restrict their use in research settings [

14].

Psychometric tools, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire [

15], enable the measurement of both qualitative and quantitative aspects of pain. Despite their utility, these tools can be time-consuming and less practical for older or physically frail patients. Combining objective and subjective data, such as physiological markers and self-reporting methods, provides the most effective approach to understanding the complexity of pain [

16].

The objectification of pain also requires attention to physical parameters that complement subjective reports. Changes in blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and skin colouration can signal the presence of pain. Additionally, involuntary reactions, such as changes in facial expressions, muscle tension, or altered posture, provide valuable insights into pain intensity. For example, if a patient protects a painful area or avoids movement, this behaviour may indicate an underlying condition. Pain assessment thus relies not only on verbal complaints but also on nonverbal cues, contributing to a more accurate evaluation and the development of appropriate treatments [

17] (

Figure 1 and 2).

Role of Nurses in Chronic Pain Management of the Elderly

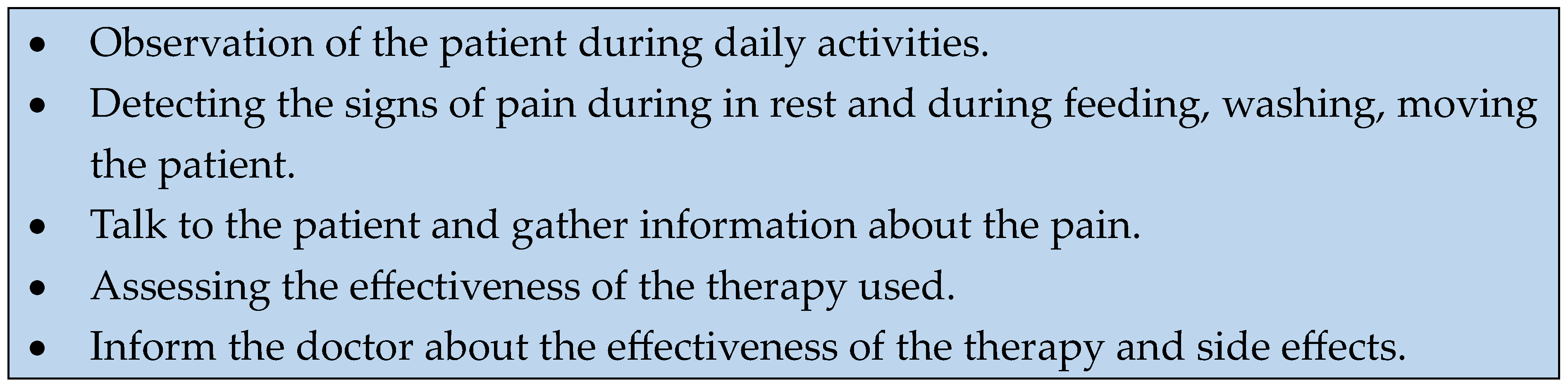

Nurses play a pivotal role in the care of elderly patients, particularly when addressing chronic pain. Relieving pain in older adults is not only essential for improving their quality of life but also a fundamental requirement for ensuring the effective and safe delivery of nursing care. This section explores why nurses hold such a central role in pain management and the key considerations they must take into account [

18].

Nurses are the healthcare professionals most closely connected to patients. In the daily and long-term care of older adults, their continuous presence allows them to thoroughly understand the patient’s condition, complaints, and other needs. Older adults often experience a combination of physical and psychological symptoms that can only be adequately addressed when the nurse has detailed information about their state.

Nurses can identify signs of chronic pain, even when the patient cannot or will not articulate them. Older adults often tend to downplay their complaints, believing that pain is an inevitable part of aging. Through empathetic approaches and experience, nurses can help bring these issues to light.

Chronic pain affects not only the patient but also the nurse’s workload. Pain often makes patients less able or willing to cooperate with nursing tasks such as bathing, feeding, or mobilization. This not only complicates the nurse’s work but also increases the risk of complications, such as pressure ulcers. For example, pain during movement may hinder a patient’s rehabilitation. In such cases, nurses must not only manage the pain but also devise alternative strategies to mobilize the patient while minimizing discomfort. Untreated pain frequently leads to psychological stress, anxiety, or depression, further distancing the patient from an improved quality of life.

Nurses play a crucial role in collecting and communicating information about the patient. They act as the eyes and ears of the medical team, continuously monitoring the patient’s condition and reporting any changes. This is particularly important for older adults, as patients with multiple chronic illnesses can experience rapid and subtle deteriorations. Thanks to their constant presence, nurses can accurately detect changes in the patient’s pain levels and relay this information to the physician. This is especially significant because medical visits do not always provide sufficient opportunities to gather comprehensive pain-related information from the patient.

The role of nurses extends far beyond physical care. Chronic pain often brings feelings of loneliness and social isolation. Nurses, through empathy, attention, and support, can help patients emotionally cope with their situation. Emotional support is often as critical as the pain management therapy itself.

Nurses are vital members of the multidisciplinary team working to alleviate pain in older adults. Collaboration among physicians, physical therapists, dietitians, and nurses is essential to provide comprehensive and holistic care. Within this team, the nurse ensures that medical instructions are effectively implemented in practice.

Nurses are also skilled in documenting pain intensity, location, and characteristics in detail, which is fundamental for selecting the appropriate therapy. Their observations form the basis of a tailored and effective pain management plan (

Figure 3).

Pain Relief Options: A Discussion of Drug and Non-Pharmacological Therapy

Pain is one of the most fundamental and complex biological and psychological phenomena in human life [

19]. While acute pain is a physiologically useful defence mechanism that alerts the body to potential or existing tissue damage, chronic pain is not [

20]. Persistent pain not only causes physical suffering but can also significantly impair quality of life, cause psychological distress, and limit daily activities. This can lead to social isolation and depression [

21].

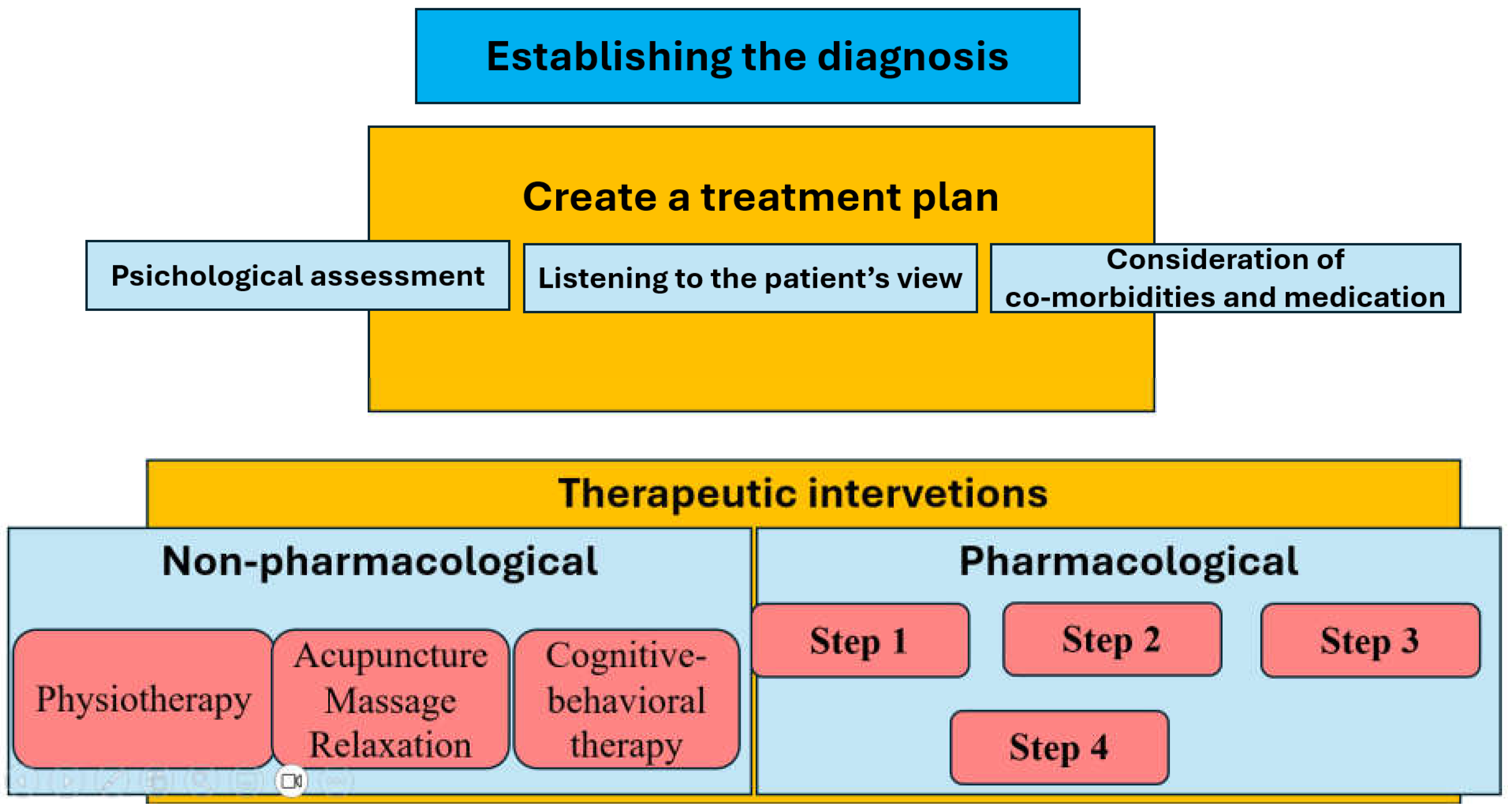

A plethora of therapeutic options exist to alleviate this condition, which can be broadly categorised into two primary classifications: drug-based interventions and non- pharmacological treatments [

22]. The selection of an appropriate treatment is contingent on a multitude of factors, including the aetiology, intensity, and duration of the affliction [

23]. Acute pain, by virtue of its transitory nature, is typically addressed through the implementation of targeted, short-term therapeutic interventions. Conversely, the management of chronic pain, which is characterised by its multifactorial origins and complex pathophysiology, necessitates an integrated, multidisciplinary approach that encompasses diverse therapeutic modalities.

The effective management of pain frequently necessitates a multifaceted approach, encompassing various therapeutic modalities, including pharmacological treatments, physiotherapy, psychological interventions, and lifestyle modifications. This holistic strategy is designed not solely to alleviate pain but also to enhance the patient’s quality of life, restore functional capabilities, and optimise long-term health outcomes.

Pharmacological Management of Pain

Medication represents one of the most predominant methods of providing rapid and effective pain relief. Medicines exert their effects via diverse mechanisms, thus enabling the treatment of a variety of pain types. Analgesic drugs can be categorised into three primary categories: minor and major analgesics, and adjuvant drugs.

Minor Analgesics

These are employed in the management of pain of mild to moderate intensity. Representing a highly prevalent class of analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that are frequently prescribed for the management of pain and inflammation include ibuprofen and diclofenac. Beyond their ability to alleviate discomfort, NSAIDs also demonstrate substantial anti-inflammatory properties, making them particularly efficacious in the treatment of pain associated with inflammation [

24]. Nevertheless, caution should be considered when recommending their long-term use, as this may potentially result in adverse effects, such as gastrointestinal disorders, hypertension, or renal deterioration [

25].

Paracetamol, another widely used analgesic, is particularly effective for mild pain and has a low potential for adverse effects. However, it is important to note that at high doses, it can cause liver damage, so it is essential to adhere to the recommended dosage [

26] (

Table 1).

Major Analgesics

Major analgesics are used to treat more severe pain. These include opioids such as morphine, fentanyl and oxycodone. Opioids are highly effective in treating severe pain, for example after surgery or for cancer pain. [

27] However, their long-term use can carry serious risks due to a range of side effects including vomiting, constipation, respiratory depression and confusion [

28].

Their correct use is complicated by the fear of addiction and tolerance. When opioids are used to treat cancer pain, the development of dependence should not be a major concern [

29]. The use of opioids in this case is not only to reduce pain, but also to ensure a dignified life for the patient. For patients with terminal illnesses, pain relief is an eminent part of maintaining quality of life. Therefore, the use of opioids in these patients is necessary and justified rather than dangerous [

30]. They are used under medical supervision, under controlled conditions, and the dosage should always be adapted to the patient’s pain. Medical necessity and the patient’s quality of life are paramount, so the risk of addiction is minimal if treatment is administered appropriately (

Table 2).

Adjuvant Medications

Adjuvant medications are not primarily indicated for pain relief but are very effective in treating certain types of pain or complementing other medications. Examples include antidepressants (e.g., tricyclics or SSRIs), which can be used to treat chronic pain such as neuropathic pain [

31]. Similarly, anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine) are also used to relieve neuropathic pain [

32]. The aim of these drugs is not only to reduce pain, but also to affect the neurological processing of pain sensations.

Medication Strategy for Pain Relief

In the case of medication for pain relief, it is important not only to determine the type and dosage of the medication, but also to adjust the route and frequency of administration.

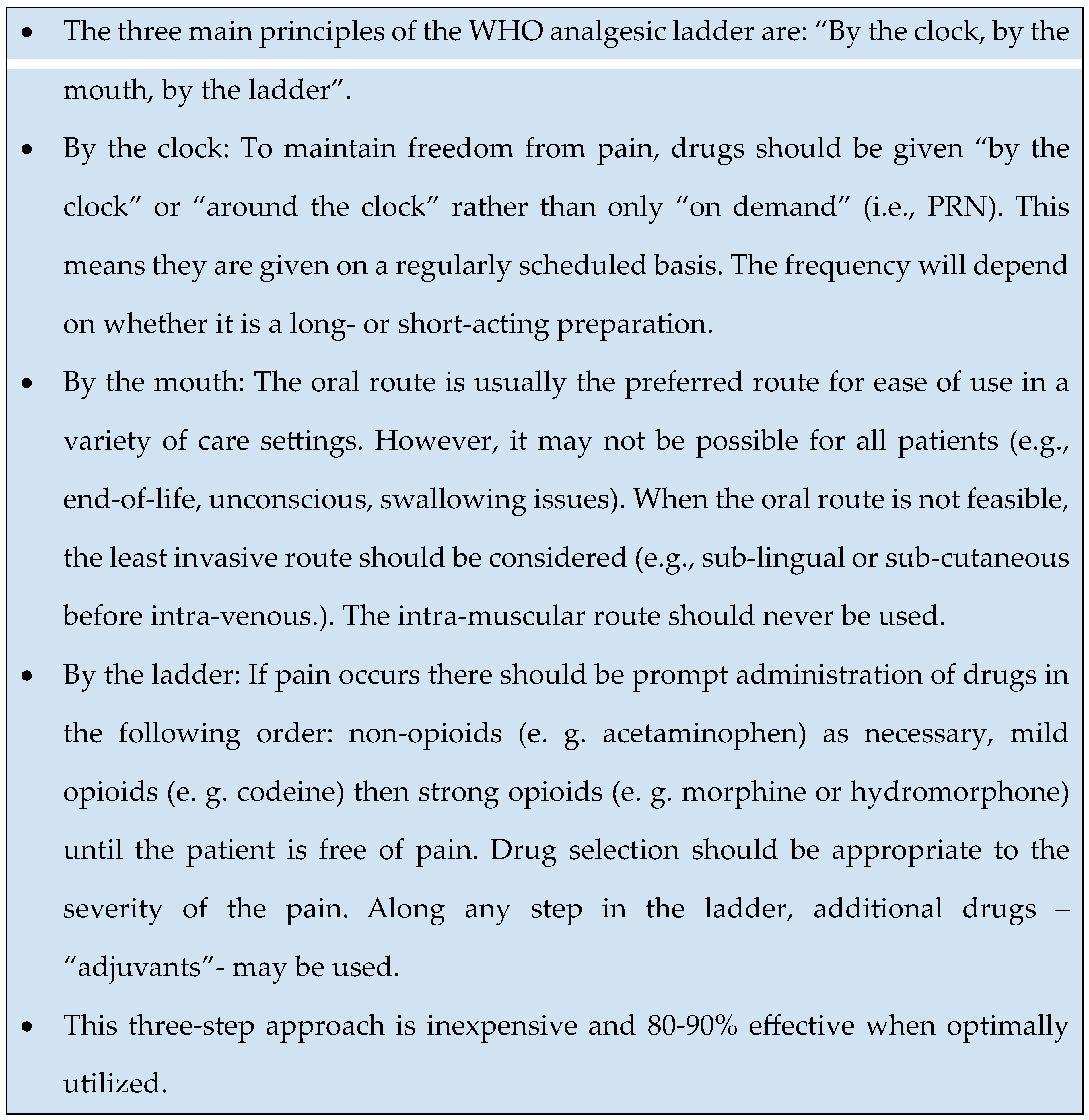

The basic principles of pharmacological analgesia include a stepwise therapeutic approach using different analgesics depending on the intensity of the pain [

33] (

Figure 4).

There are three main levels of stepwise analgesia (The WHO Pain Ladder): level 1 for mild pain, level 2 for moderate pain and level 3 for severe pain [

34] (

Figure 5). At level 1, pain is usually relieved with NSAIDs or paracetamol, which can be effective for minor pain such as headaches, muscle aches or minor injuries. If the pain does not respond to these drugs, we can move to step two, where we give milder opioids, such as tramadol, which can reduce the pain without causing many harmful side effects. At the third level, once the pain becomes more severe, stronger opioids such as morphine, oxycodone or fentanyl may be required, which can be very effective in reducing pain, for example in patients with tumours or severe injuries. The advantage of a stepwise approach is that it allows for gradual and effective use of analgesics, while minimising overuse and side effects.

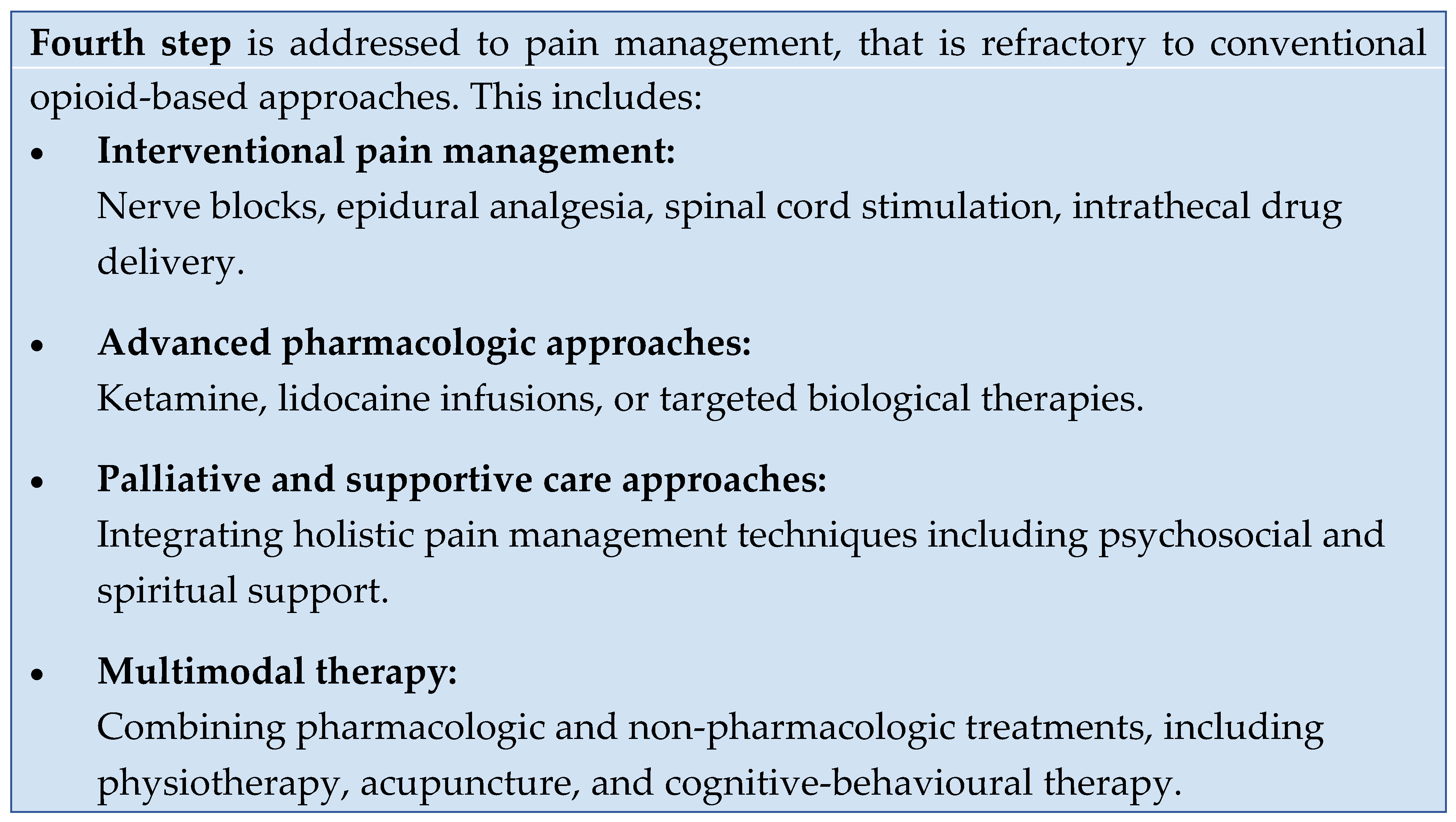

While the original World Health Organization (WHO) ladder consisted of three steps, the revised version is supplemented with a fourth ladder [

35] (

Figure 6).

Surgical intervention or minimally invasive procedures could add further pain relief if the applied medication does not work well [

36].

The original WHO ladder was unidirectional, starting from the lowest step of NSAIDs, including COX inhibitors or acetaminophen, and heading towards the strong opioids, depending on the patient’s pain. The updated WHO analgesic ladder focuses on the quality of life and is intended as a bidirectional approach; clinicians should also provide de-escalation of treatment in the case of chronic pain resolution.

The use of combinations of medicines is an important element in the treatment of pain. A combination of medicines used for pain relief can help to reduce pain more quickly and effectively when a single medicine is not enough. Combining opioids and non-opioids, for example NSAIDs with weaker opioids such as tramadol, can often relieve pain while reducing the dose and side effects of each drug. For chronic pain, ad hoc use of analgesics is discouraged because it does not provide continuous and adequate pain relief. Instead of an ad hoc approach, it is important that pain relief is planned and controlled so that the patient does not suffer unnecessarily.

The effectiveness of the treatment also depends on the way the painkillers are used. Different routes of administration ensure that the drugs work as quickly and for as long as possible. Rectal administration, for example in the form of suppositories, is particularly useful if the patient is unable to take medication orally, for example because of vomiting or difficulty swallowing. Suppositories are rapidly absorbed through the intestinal wall, providing a rapid analgesic effect. The disadvantage is that not all patients are willing to accept suppositories, and not all painkillers are available in this form.

Oral drops are absorbed quickly and allow flexible dosing. This can be particularly useful when pain is sudden and immediate relief is needed. Transdermal (through the skin) application using patches is one of the most convenient routes of administration. A well-accepted example is the fentanyl patch, which provides continuous pain relief for up to 72 hours. This has the advantage of being convenient and not requiring frequent use of the medication, but the disadvantage that the initial effect is slower, and the patches are not always comfortable for patients.

Long-acting medicines, such as long-acting opioids or fentanyl patches, can be of significant benefit in pain management, especially for people with persistent pain, such as cancer patients. They have the advantage of being more convenient as they do not need to be administered frequently. Sustained-release preparations provide continuous pain relief, which can help to reduce anxiety and worry for patients, as they can be assured that the pain relief will continue. Such preparations can help reduce the development of breakthrough pain (sudden onset of pain). If breakthrough pain does occur, fast-acting opioids may be needed.

It is also important to consider the side effects of painkillers, especially in older people. Prolonged use of opioids can cause constipation, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, respiratory depression and altered mental status, especially at higher doses. The main side effects of NSAIDs include damage to the stomach lining, high blood pressure and kidney damage.

Pregabalin, gabapentin and carbamazepine are anticonvulsants used to relieve neuropathic neuralgiform pain. They have an opiate-like spectrum of side effects (vomiting, constipation, respiratory depression, drowsiness) and may cause memory loss, difficulty concentrating and other cognitive problems (slowing of thinking), and depression [

37]. Carbamazepine may also cause agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia and hyponatraemia [

38].

Older people often take several medicines at the same time. Taking more than five medicines is called polypharmacy [

39]. Some studies suggest that around 30-50% of people over 65 take more than five medicines [

40]. This can increase the incidence of adverse effects, as different drugs may interact with each other. Opioids and other sedatives, such as benzodiazepines, may increase the risk of respiratory depression, dizziness and drowsiness when used together. Elderly patients should be treated with caution, as impaired renal and hepatic function may lead to slower metabolism of the drugs, resulting in accumulation and higher risk of side effects.

The issue of polypharmacy is particularly important in the treatment of elderly patients, as the concomitant use of multiple drugs increases the risk of drug-drug interactions and side effects. It is therefore important to keep the patient’s medication list under constant review. Ensuring the correct dosage and use of medicines in older patients is key to successful pain management.

The Difficulties of Pain Relief from the Perspective of Patients and Clinicians

Chronic pain management presents many challenges for both patients and clinicians. Many aspects of long-term pain management can cause problems that affect the effectiveness of treatment and the patient’s quality of life. One of the biggest difficulties for patients is accepting the sensation of pain and communicating it accurately to their doctors. Chronic pain is often a subjective phenomenon and patients are not always able to accurately describe its nature, intensity or impact on other aspects of their lives, which can reduce the effectiveness of pain management[

41]. In addition, many patients may be frustrated if pain relief does not result in immediate or lasting improvement, as the effects of painkillers are not always predictable and long-term adherence to treatment requires patience.

Side effects can also be a common problem for patients. Long-term use of painkillers often leads to dizziness, drowsiness, indigestion or reduced social and work activity, which can significantly affect patients’ quality of life. In addition, long-term use of opioids and other stronger painkillers for chronic pain can cause patients to worry about developing an addiction, which can lead to further inhibition, fear or rejection, even if the doctor believes the treatment is safe. Patients often refuse to take painkillers properly if they feel they are not effective or experience too many side effects. Refusing to take painkillers for long periods can therefore lead to non-adherence to medical recommendations [

42].

The management of chronic pain is a complex and time-consuming task for healthcare professionals. Pain management requires not only drug therapy but also a complex approach that may include physiotherapy, psychological support and lifestyle changes. As well as physical pain, psychological and social difficulties can also make diagnosis and treatment difficult. The use of painkillers is often not a complete solution, and doctors need to consider individual factors to develop a tailored treatment plan.

In addition, doctors often do not have enough time or resources to deal with the complex issues involved in pain management. In addition to medication, it is often necessary to involve several specialists, such as a pain specialist, psychologist or physiotherapist, but these integrated treatments are not always available in the healthcare system. Doctors must therefore consider the safety of the medication, the side effects and the level of pain relief experienced by the patient, as well as the risks associated with long-term use of the medication, such as the development of tolerance or drug interactions. It is common experience that physicians are reluctant to give patients adequate analgesia, despite their primary duty to reduce patient suffering [

43].

One of the ethical and legal aspects of chronic pain management is the use of opioids, which carries the risk of addiction. Doctors need to monitor patients’ conditions to avoid overuse and to ensure that treatment does not lead to situations that could have legal consequences. Another concern is that the use of opioids can lead to a loss of patient autonomy. Maintaining doctor-patient trust and ensuring appropriate medication is therefore key for both parties. Continuous review of treatment and the use of alternative pain management options can help to ensure that pain relief remains effective and safe.

Non-Pharmacological Approaches to Pain Management

Although medication offers an effective solution to pain management, a growing body of research and clinical experience suggests that non-pharmacological therapies can also play an important role in pain management, particularly in the management of chronic pain [

44].

Physiotherapy is one of the most widely used non-pharmacological treatments. Various types of massage, heat and cold treatments, and physiotherapy exercises can provide significant pain relief, especially for musculoskeletal pain such as arthritis or back pain. Electrotherapy such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can also be used successfully to reduce pain [

45].

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a psychological treatment that can help manage negative psychological responses to pain. CBT aims to teach people to live more positively with pain by changing their thoughts and behaviours about pain. These techniques can help reduce the perception of pain and reduce pain-related anxiety and stress [

46].

Acupuncture, a well-known method of traditional Chinese medicine, reduces pain by inserting needles into specific points on the body. Although the mechanism of acupuncture is not fully understood, a large body of research and clinical practice suggests that it can be effective in relieving various types of pain, such as chronic back pain, migraines or joint pain [

47]. Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, meditation and visualisation can also help reduce pain [

48,

49].

Biofeedback technology allows patients to consciously control their own physiological functions, such as pulse, muscle tension or breathing. The control of these functions can help in pain management as the patient can learn to control pain responses [

50] (

Figure 7).

Key Summary

Principles of treatment of chronic pain in the elderly

Pain relief is a complex process in which both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy play an important role.

Since the sensation of pain is subjective, its definition requires complex methods.

Pain is always as strong as the patient perceives it to be.

Medications can be divided into three main groups: minor and major analgesics, and adjuvant agents.

The choice of appropriate treatment always depends on the type, intensity of pain, and the patient's condition. Although medications can provide rapid and effective relief, non-pharmacological treatment modalities can significantly contribute to pain management.

For effective pain reduction, the best results can be achieved by combining the two approaches, taking into account the individual needs and condition of the patient.

Author Contributions

Authors equally contributed to write the article

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest

References

- Patel KV, Guralnik JM, Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. Pain. 2013;154(12):2649-57. [CrossRef]

- Whitlock EL, Diaz-Ramirez LG, Glymour MM, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE, Smith AK. Association Between Persistent Pain and Memory Decline and Dementia in a Longitudinal Cohort of Elders. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1146-53. [CrossRef]

- Carta G, Costantini G, Garzonio S, Romano D. Investigation of the Relevant Factors in the Complexity of Chronic Low Back Pain Patients With a Physiotherapy Prescription: A Network Analysis Approach Comparing Chronic Pain-Free Individuals and Chronic Patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;102(7):571-6. [CrossRef]

- Rajput K, Ng J, Zwolinski N, Chow RM. Pain Management in the Elderly: A Narrative Review. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(3):671-91. [CrossRef]

- Mears L, Mears J. The pathophysiology, assessment, and management of acute pain. Br J Nurs. 2023;32(2):58-65. [CrossRef]

- Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1331-46. [CrossRef]

- Jackson T, Thomas S, Stabile V, Shotwell M, Han X, McQueen K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Global Burden of Chronic Pain Without Clear Etiology in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Trends in Heterogeneous Data and a Proposal for New Assessment Methods. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(3):739-48. [CrossRef]

- Lautenbacher S, Peters JH, Heesen M, Scheel J, Kunz M. Age changes in pain perception: A systematic-review and meta-analysis of age effects on pain and tolerance thresholds. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;75:104-13. [CrossRef]

- Mullins S, Hosseini F, Gibson W, Thake M. Physiological changes from ageing regarding pain perception and its impact on pain management for older adults. Clin Med (Lond). 2022;22(4):307-10. [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P. The Assessment of Pain in Older People: UK National Guidelines. Age Ageing. 2018;47(suppl_1):i1-i22. [CrossRef]

- Bicket MC, Mao J. Chronic Pain in Older Adults. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33(3):577-90. [CrossRef]

- Madariaga VI, Overdorp E, Claassen J, Brazil IA, Oosterman JM. Association between Self-Reported Pain, Cognition, and Neuropathology in Older Adults Admitted to an Outpatient Memory Clinic-A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sci. 2021;11(9). [CrossRef]

- Dunford E, West E, Sampson EL. Psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia scale in an acute general hospital setting. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37(12). [CrossRef]

- Elliott JM, Owen M, Bishop MD, Sparks C, Tsao H, Walton DM, et al. Measuring Pain for Patients Seeking Physical Therapy: Can Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) Help? Phys Ther. 2017;97(1):145-55. [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1(3):277-99. [CrossRef]

- Brooks AK, Udoji MA. Interventional Techniques for Management of Pain in Older Adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(4):773-85. [CrossRef]

- Closs SJ, Cash K, Barr B, Briggs M. Cues for the identification of pain in nursing home residents. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42(1):3-12. [CrossRef]

- Alodhialah AM, Almutairi AA, Almutairi M. Assessing the Association of Pain Intensity Scales on Quality of Life in Elderly Patients with Chronic Pain: A Nursing Approach. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(20). [CrossRef]

- Hadjistavropoulos T, Craig KD, editors. Pain: Psychological Perspectives2004.

- Koneti KK, Jones M. Management of acute pain. Surgery (Oxford). 2013;31(2):77-83. [CrossRef]

- Murray CB, Murphy LK, Jordan A, Owens MT, McLeod D, Palermo TM. Healthcare Transition Among Young Adults With Childhood-Onset Chronic Pain: A Mixed Methods Study and Proposed Framework. The Journal of Pain. 2022;23(8):1358-70. [CrossRef]

- Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2082-97. [CrossRef]

- Hainline, B. Chronic pain: physiological, diagnostic, and management considerations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(3):713-35, 31. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro H, Rodrigues I, Napoleão L, Lira L, Marques D, Veríssimo M, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), pain and aging: Adjusting prescription to patient features. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150:112958. [CrossRef]

- LaForge JM, Urso K, Day JM, Bourgeois CW, Ross MM, Ahmadzadeh S, et al. Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Clinical Implications, Renal Impairment Risks, and AKI. Adv Ther. 2023;40(5):2082-96. [CrossRef]

- Freo U, Ruocco C, Valerio A, Scagnol I, Nisoli E. Paracetamol: A Review of Guideline Recommendations. J Clin Med. 2021;10(15). [CrossRef]

- Sun XJ, Feng TC, Wang YM, Wang F, Zhao JB, Liu X, et al. The effect of the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and the reduced use of opioids on postoperative outcomes in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(20):10053-60. [CrossRef]

- Khademi H, Kamangar F, Brennan P, Malekzadeh R. Opioid Therapy and its Side Effects: A Review. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(12):870-6.

- Auret K, Schug SA. Underutilisation of opioids in elderly patients with chronic pain: approaches to correcting the problem. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(8):641-54. [CrossRef]

- Kotalik, J. Controlling pain and reducing misuse of opioids: ethical considerations. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(4):381-5, e190-5.

- Coluzzi F, Mattia C. Mechanism-based treatment in chronic neuropathic pain: the role of antidepressants. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(23):2945-60. [CrossRef]

- Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Clarke H, Dao T, Finley GA, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):328-35. [CrossRef]

- Davison, SN. Clinical Pharmacology Considerations in Pain Management in Patients with Advanced Kidney Failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(6):917-31. [CrossRef]

- Ventafridda V, Saita L, Ripamonti C, De Conno F. WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. Int J Tissue React. 1985;7(1):93-6.

- Anekar AA, Hendrix JM, Cascella M. WHO Analgesic Ladder. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Vissers KC, Besse K, Wagemans M, Zuurmond W, Giezeman MJ, Lataster A, et al. 23. Pain in patients with cancer. Pain Pract. 2011;11(5):453-75. [CrossRef]

- Mathieson S, Lin CC, Underwood M, Eldabe S. Pregabalin and gabapentin for pain. Bmj. 2020;369:m1315. [CrossRef]

- Dyong TM, Gess B, Dumke C, Rolke R, Dohrn MF. Carbamazepine for Chronic Muscle Pain: A Retrospective Assessment of Indications, Side Effects, and Treatment Response. Brain Sci. 2023;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi SS, Shati M, Keshtkar A, Malakouti SK, Bazargan M, Assari S. Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010989. [CrossRef]

- Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57-65. [CrossRef]

- Náfrádi L, Kostova Z, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. The doctor-patient relationship and patient resilience in chronic pain: A qualitative approach to patients’ perspectives. Chronic Illn. 2018;14(4):256-70. [CrossRef]

- Niehaus R, Urbanschitz L, Schumann J, Lenz CG, Frank FA, Ehrendorfer S, et al. Non-Adherence to Pain Medication Increases Risk of Postoperative Frozen Shoulder. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12:115. [CrossRef]

- Glajchen, M. Chronic pain: treatment barriers and strategies for clinical practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(3):211-8.

- Shrestha S, Schofield P, Devkota R, editors. A critical literature review on non-pharmacological approaches used by older people in chronic pain management2013.

- Ambrose KR, Golightly YM. Physical exercise as non-pharmacological treatment of chronic pain: Why and when. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(1):120-30. [CrossRef]

- Niknejad B, Bolier R, Henderson CR, Jr., Delgado D, Kozlov E, Löckenhoff CE, et al. Association Between Psychological Interventions and Chronic Pain Outcomes in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):830-9. [CrossRef]

- Morone NE, Greco CM. Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: a structured review. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):359-75. [CrossRef]

- Park J, Hughes AK. Nonpharmacological approaches to the management of chronic pain in community-dwelling older adults: a review of empirical evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):555-68. [CrossRef]

- Horgas, AL. Pain Management in Older Adults. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;52(4):e1-e7. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann A, Edelhoff D, Schubert O, Erdelt KJ, Pho Duc JM. Effect of treatment with a full-occlusion biofeedback splint on sleep bruxism and TMD pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24(11):4005-18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).