1. Introduction

The most common method for extracting cosmetic compounds from natural resources employs organic solvents which generally have a negative environmental and health impact because the toxicity, volatility, and other intrinsic factors for those substances. Some researchers suggest the use of new cleaner methodologies through the development of 100% natural and biodegradable solvents, known as Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents or Nades [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These solvents are a green proposal useful for industry processes requiring extraction for organic substances. Nades are defined as homogeneous eutectic mixtures obtained by mixing two or more natural pure components (liquids or solids, ions or neutral molecules) consisting in hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) and hydrogen bond donors (HBD) [

6]. These green solvents are inspired by nature, and the how metabolites are dissolved and stabilized within plants by eutectic combinations of simple chemicals, for instance sugars, polyols or amino acids; furthermore, considering the diversity of constituents that can enter in the preparation of Nades, the prospects offered by these mixtures for the development of new extraction processes are very broad. According to different authors, since 1995 more eco-friendly experimental techniques have been proposed and developed, establishing basic principles for this approach called Green Chemistry [

7,

8,

9,

10]. To avoid harmful synthetic compounds in new cosmetics, Nades offer the needed properties in the final products with minimal side effects [

6,

11].

Examples of some processes including Nades for the cosmetic industry include the extraction of phenolic acids and flavonoids from the flowers of

Calendula officinalis with mixtures of fructose/glycerine, fructose/betaine and fructose/sorbitol, among others. Each of them exhibited an extraction efficiency towards phenolic acids equal to or higher than the best conventional solvents (for instance, MeOH, EtOH, acetone, hexane, EtOAc, CHCl₃, CH₂Cl₂) [

12]. Extraction of phenylethanes and phenylpropanoids from

Rhodiola rosea L. used a L-lactic acid/fructose-based Nades which was proposed as a viable alternative to 40% aqueous/ethanol mixture for the extraction of salidroside, tyrosol, rosavin, rosin and cinnamyl alcohol [

13].

The extensive bioactivity of macroalgae has been linked to the presence of many inorganic and organic compounds including carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, vitamins, hormones, and secondary metabolites (terpenoids, steroids, alkaloids, phenolic compounds, etc.) more abundant than the amount found in the terrestrial environment [

14,

15,

16]. A review of the existing literature found a few reports related to the use of Nades for the extraction of secondary metabolites from marine natural sources, especially focused to extraction of phlorotannins and trace metals from

Fucus vesiculosus [

17,

18], fatty acids from Spirulina [

19], phycoerythrin from

Porphyra yezoensis [

20], and α-chitin from crab

Polybius henslowii [

21], also the extraction of phlorotannins from brown macroalgae

Ascophyllum nodosum L. [

22]. The extraction efficiency of polyphenolic compounds was evaluated using ten types of Nades based on choline chloride, lactic acid, betaine and glucose in various molar proportions [

12]. Another study was focused on red macroalgae, specifically

Gelidium corneum (Hudson) J.V. Lamouroux,

Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt, to obtain antioxidant-enriched extracts using Nades to introduce in cosmetic formulations [

23]. That work highlighted the role of natural deep eutectic solvents to face the lack of information concerning their use in the extraction of seaweed phenolic compounds and their application in a topical formulation for dermatological use. Extraction yields with Nades surpassed those of conventional solvents like water and ethanol (70:30, v/v) in the two extracted seaweeds. Furthermore,

S. muticum extracts revealed higher antioxidant capacity, strongly related to their high phenolic content, proving to be suitable for further dermatological applications with antioxidant properties [

23].

Moreover, an exponential growth is noticeable in the scientific reports of the last three years, which cover the use of Nades as an alternative in the extraction processes of organic compounds, as well as the direct use of Nades extracts in the production of certain cosmetic products [

24], as ingredients in different medicinal products [

25,

26] , optimization of polysaccharide extraction processes of industrial interest [

27], obtaining essential oils [

28], extraction of substances of industrial interest from plant waste from agroindustry [

29,

30], removal of contaminants in water [

31], CO

2 uptake from air, among others [

32]. It is worth to mention that switchable Nades have been reported, which can be reused several times, only by modifying the pH after extraction [

29]. However, there should be more evidence on the potential risk of using Nades, as different authors claim [

33]. This work describes results from extraction processes with Nades and other solvents to extract substances with cosmetic potential from Colombian marine macroalgae.

2. Results

2.1. Samples

Among the available macroalgae samples, six of the species analyzed were identified as brown macroalgae, while the remaining six species were classified as red macroalgae.

2.2. Preliminary Chemical Screening

Preliminary chemical screening tests for all macroalgae samples showed that all raw extracts yielded with ethanol, water and 5% HCl solution displayed positive results for polysaccharides. Alkaloids tests were negative for all samples. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) for all ethyl acetate extracts (silica gel, hexane-ethyl acetate 4:1) displayed low polarity compounds when TLC plates were revealed with UV lamp (254 and 365 nm), and with phosphomolybdic acid reagent and heat 105 °C. Phenolic compounds gave positive results for all macroalgae samples.

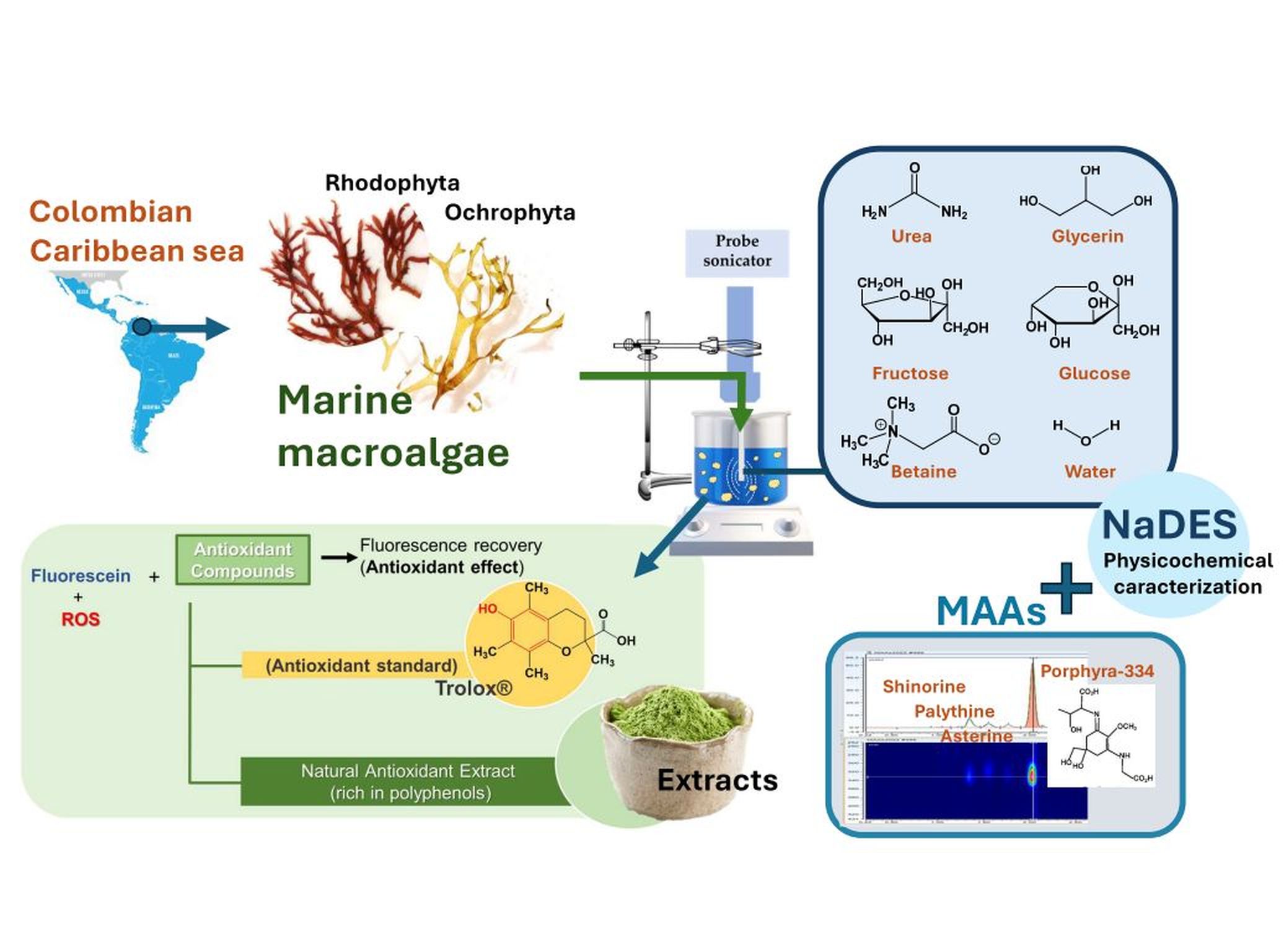

2.3. Preparation of NaDES

All prepared Nades formed a eutectic mixture in different ratios, all three systems were transparent liquids. It was observed that these solvents were stable at ambient temperature and pressure. They existed as a homogeneous liquid mixture, without any precipitates or solid material.

2.4. Extraction of Macroalgae with NaDES

The extraction of bioactive compounds using Nades was challenging due to their high viscosity, which makes handling difficult in filtration steps, and compared to conventional solvents, Nades required more energy to intensify the mass transfer through solvent-solute contact, but Nades viscosity is benefit for developing ready-to-use extracts for the cosmetics industry, as exemplified by Gattefossé™ production [

11]. These Nades allowed extractions at elevated temperatures and effectively reduced the solvent viscosity, but that reduction occurred without mass loss and helped to minimize air contamination due to there being no solvent vaporization, enhancing the effectiveness in extraction processes.

2.5. Phenolic Content Determination by the Folin-Ciocalteau Method

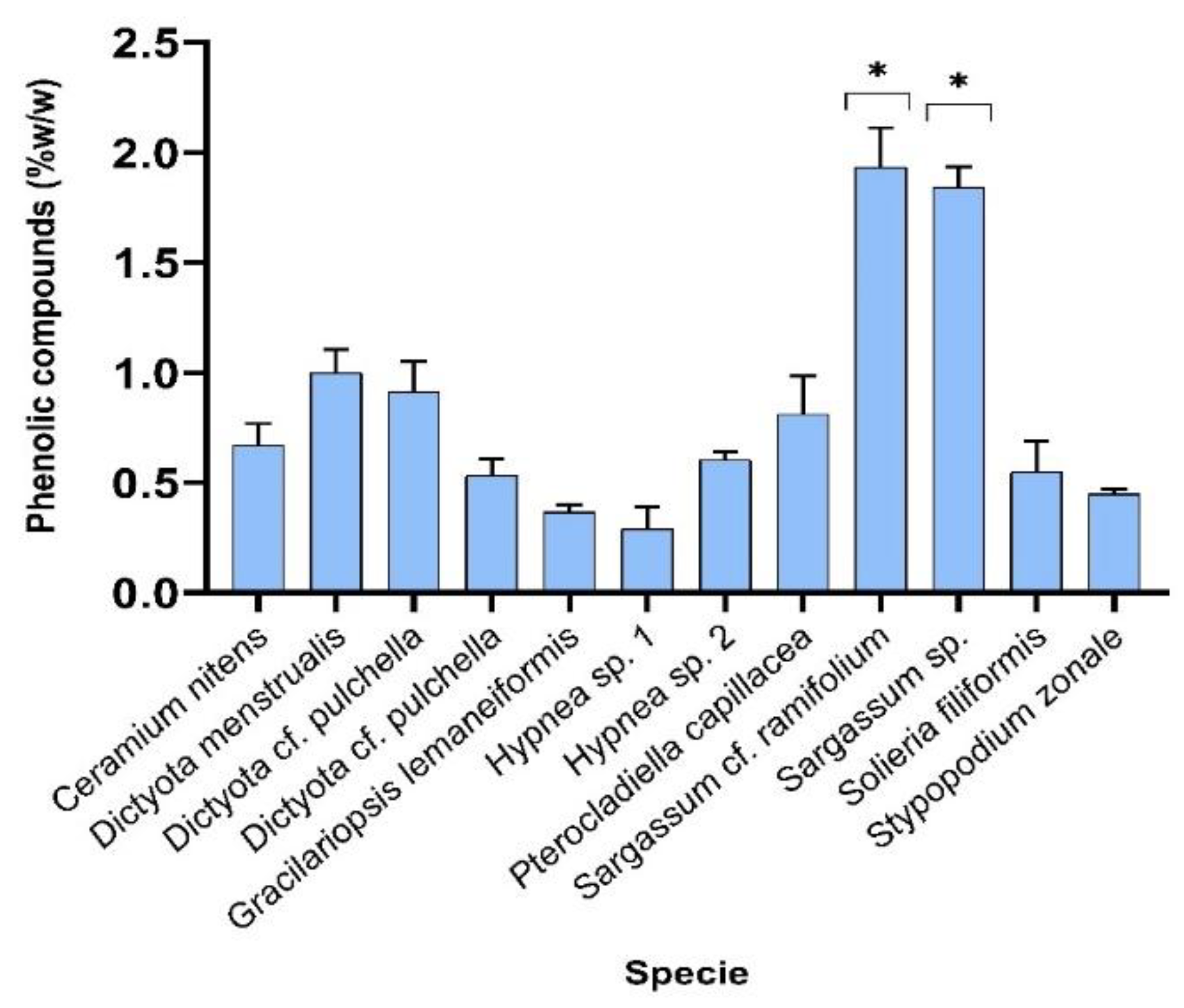

Figure 1.

Results of quantitation of phenolic compounds using Folin-Ciocalteau method, for all water extracts of macroalgae samples analysed.

Figure 1.

Results of quantitation of phenolic compounds using Folin-Ciocalteau method, for all water extracts of macroalgae samples analysed.

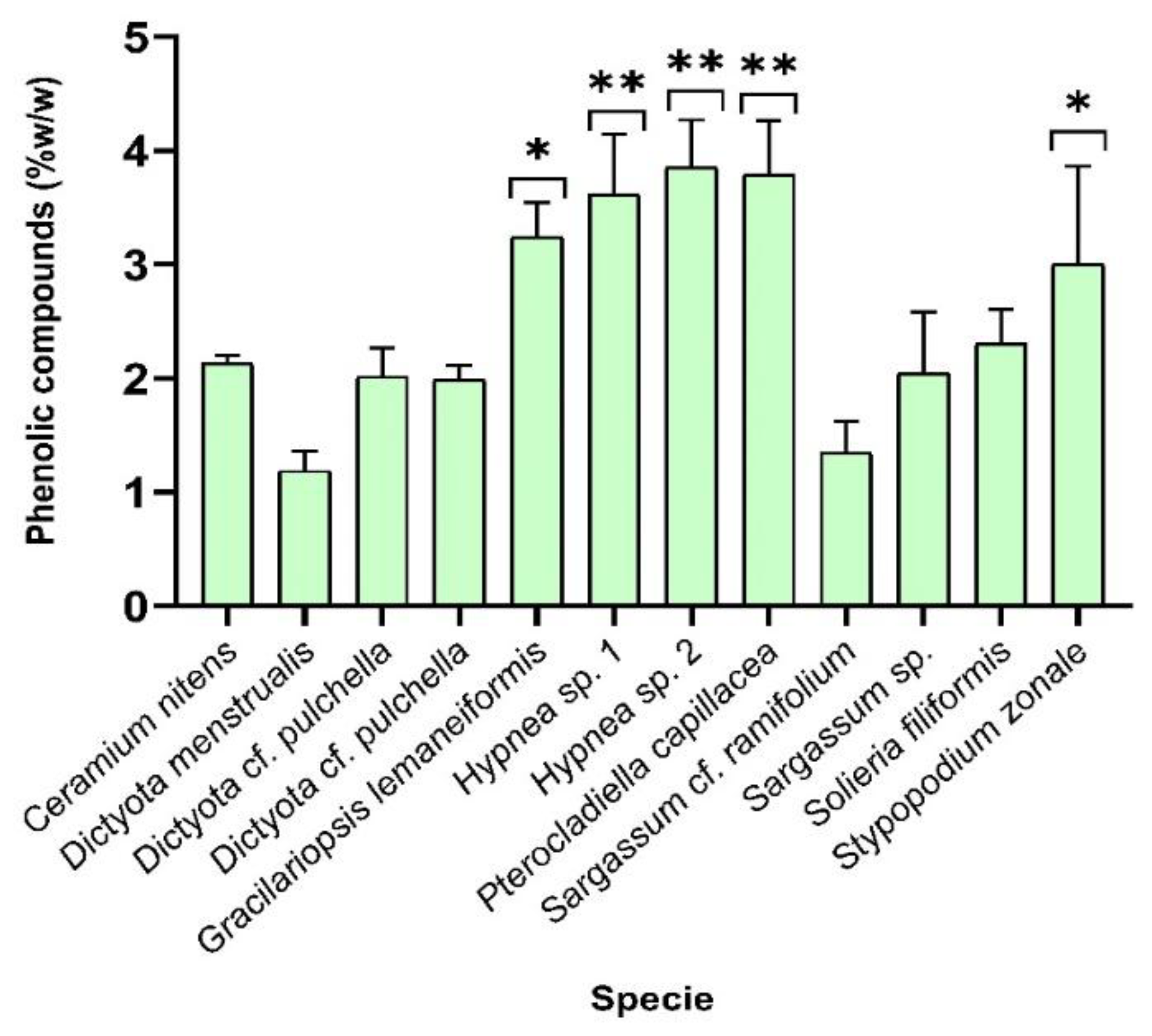

Figure 2.

Results of quantitation of phenolic compounds using Folin-Ciocalteau method, for all 5% HCl solution extracts of macroalgae samples analysed.

Figure 2.

Results of quantitation of phenolic compounds using Folin-Ciocalteau method, for all 5% HCl solution extracts of macroalgae samples analysed.

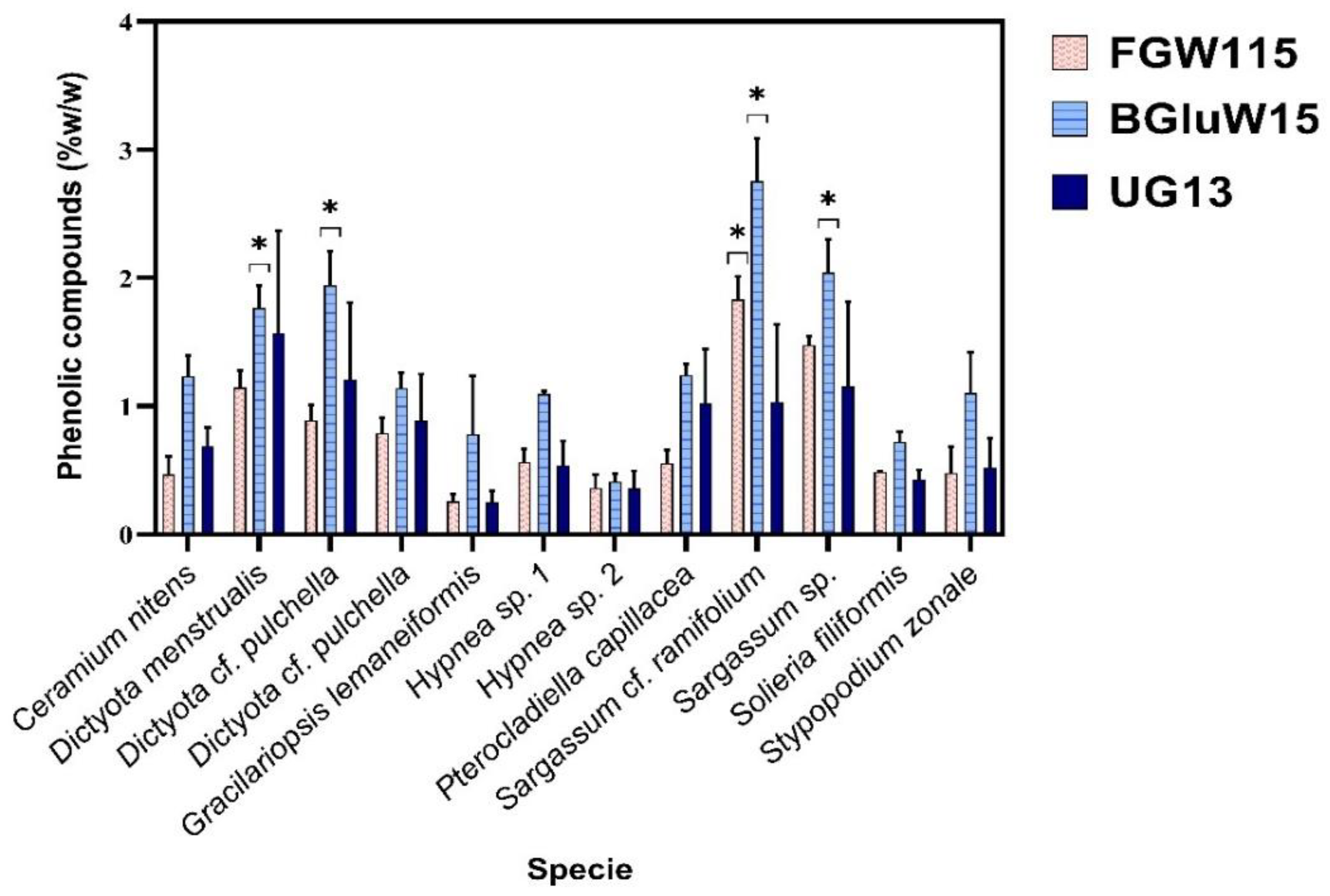

Figure 3.

Results of quantitation of phenolic compounds using Folin-Ciocalteau method, for all Nades extracts of macroalgae samples analysed.

Figure 3.

Results of quantitation of phenolic compounds using Folin-Ciocalteau method, for all Nades extracts of macroalgae samples analysed.

2.6. Estimation of the Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Quantified Extracts by DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl)

Additionally, to phenolic compounds content the DPPH radical capture assay was applied to Sargassum samples. Table 1 displays the results when using Nades for extraction. For three tested Nades, BGW 1:1:5 displays the higher percentage of phenolics (2.05%) and DPPH scavenging activity (97.63%).

Table 1.

Results for phenolics content and DPPH scavenging activity for Sargassum cf. ramifolium Nades extracts.

Table 1.

Results for phenolics content and DPPH scavenging activity for Sargassum cf. ramifolium Nades extracts.

| Nades extract |

Phenolic compounds (% w/w) |

DPPH Scavenging activity (%) |

| Urea/Glycerine 3:1 |

1.15 |

11.77 |

| Fructose/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 |

1.47 |

21.44 |

| Betaine/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 |

2.05 |

97.63 |

2.7. Pre-Scaling

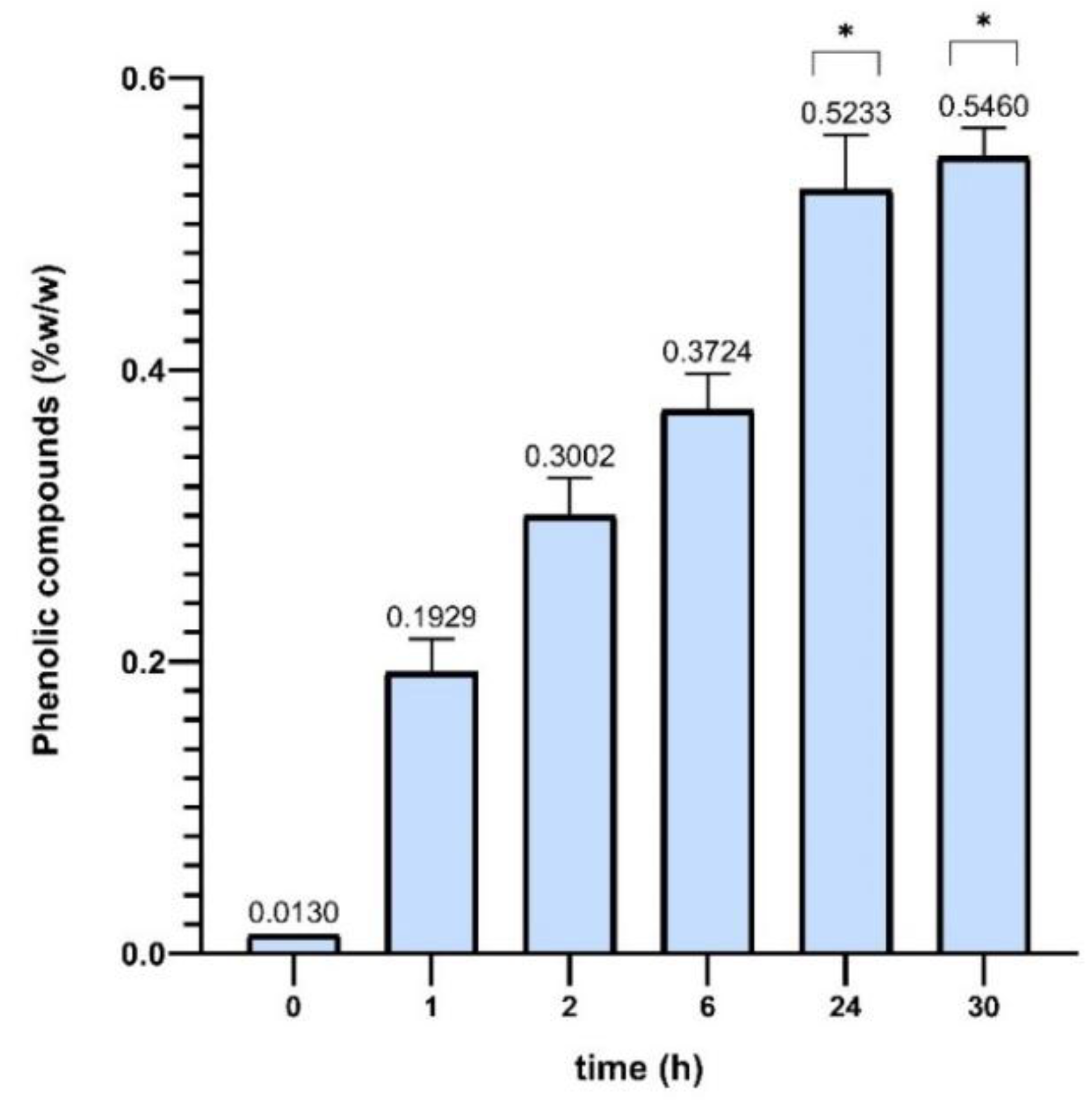

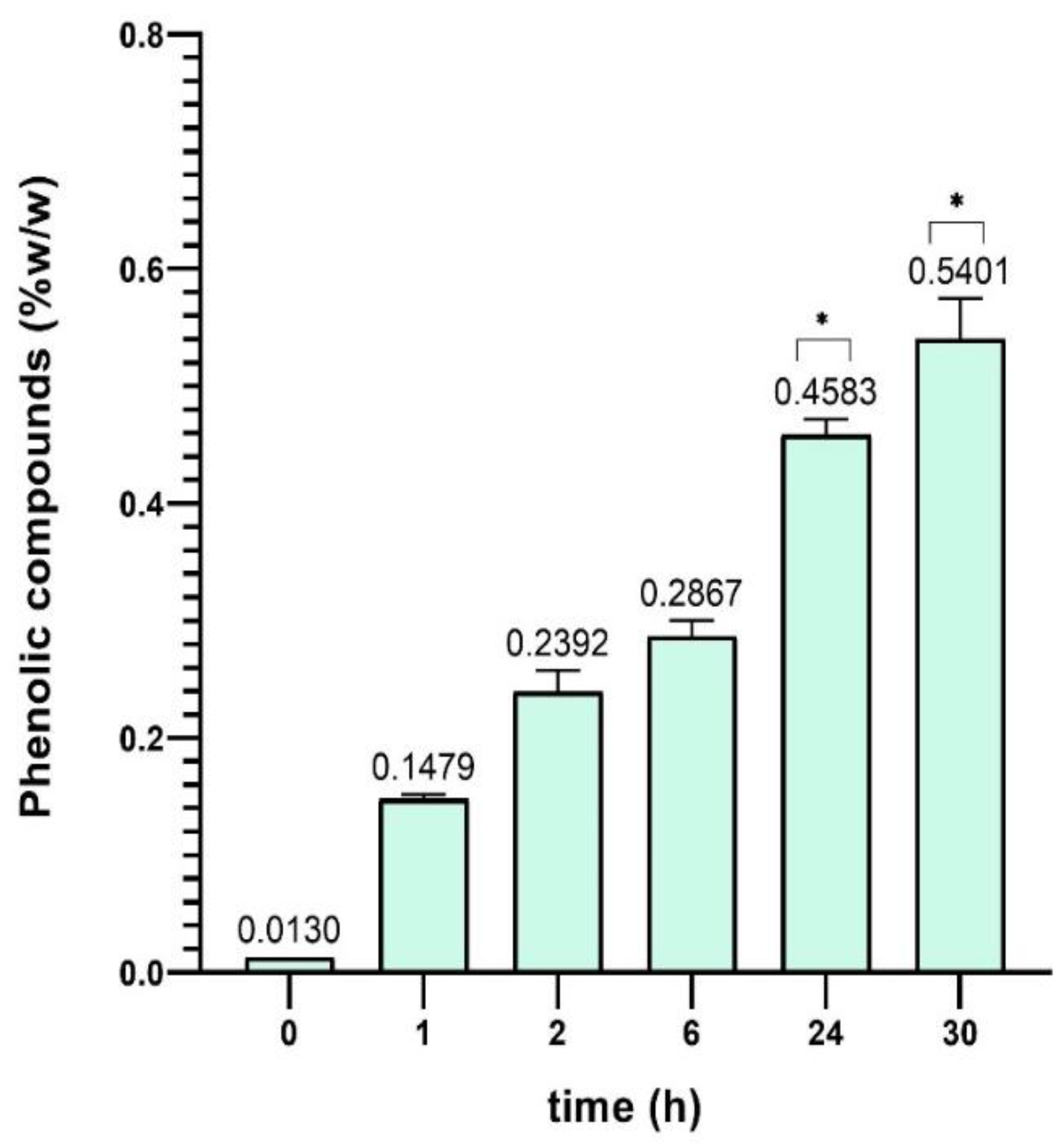

To assess the susceptibility of the analytical method to reasonable minor variations, in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 shown below, the increase in the percentage by weight of phenolic compounds in the BGluW115 solvent is observed.

Figure 4. represents the #1 reference of the components of the Nades solvent composition mentioned above; and

Figure 5. components of reference #2 for Nades solvent of equal composition.

Figure 4.

% w/w of phenolic compounds in Sargassum polyceratium using BGluW115 reference #1 (commercial betaine and glucose).

Figure 4.

% w/w of phenolic compounds in Sargassum polyceratium using BGluW115 reference #1 (commercial betaine and glucose).

Figure 5.

% w/w of phenolic compounds in Sargassum polyceratium using BGluW115 reference #2 (analytical betaine and glucose).

Figure 5.

% w/w of phenolic compounds in Sargassum polyceratium using BGluW115 reference #2 (analytical betaine and glucose).

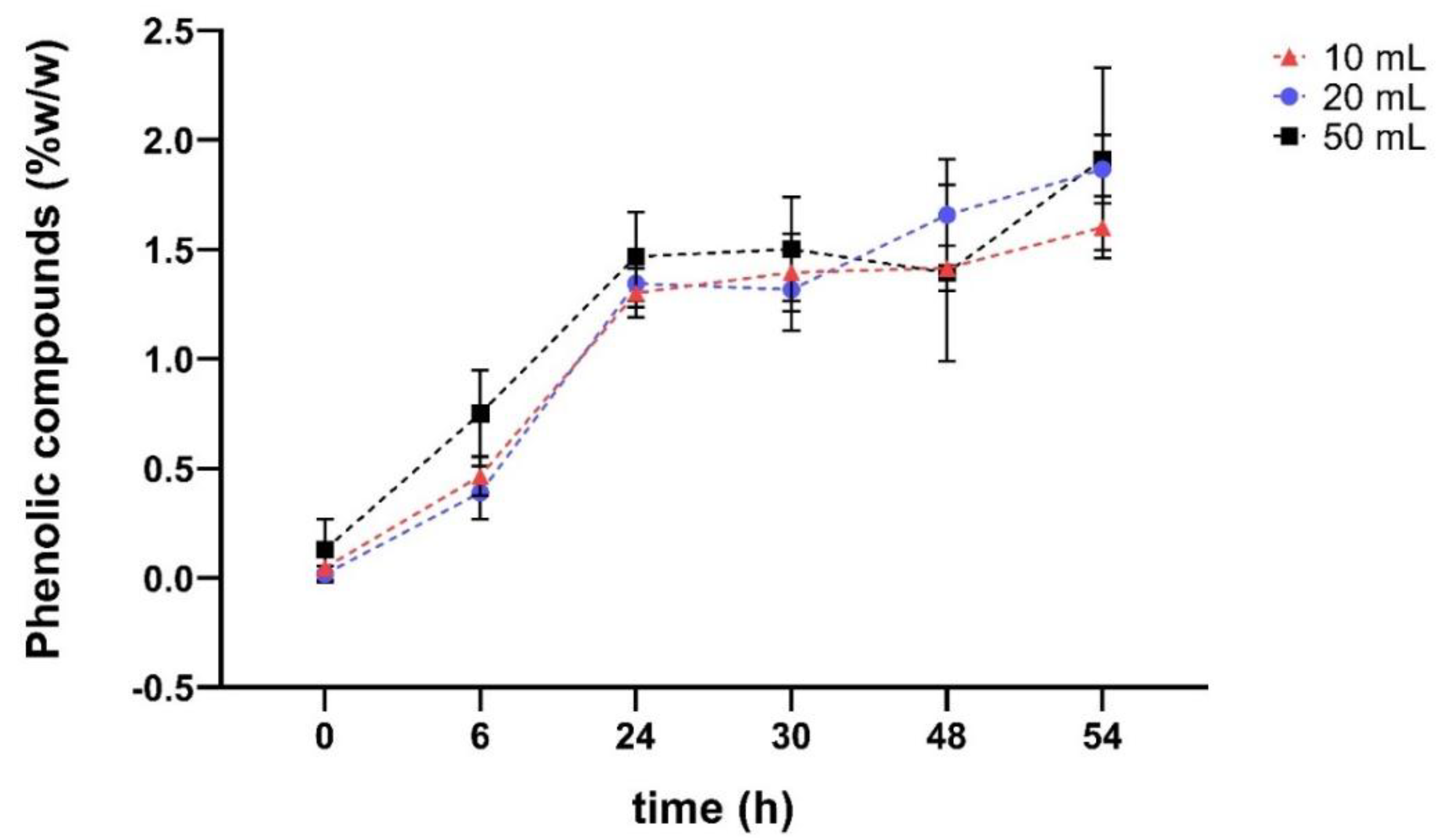

Figure 6.

% w/w of phenolic compounds from the sample Sargassum polyceratium extracted with 10 mL of Nades BGluW115 diluted at different times. Total volume of extraction Nades solvent: red 10 mL; blue 20 mL; black 50 mL.

Figure 6.

% w/w of phenolic compounds from the sample Sargassum polyceratium extracted with 10 mL of Nades BGluW115 diluted at different times. Total volume of extraction Nades solvent: red 10 mL; blue 20 mL; black 50 mL.

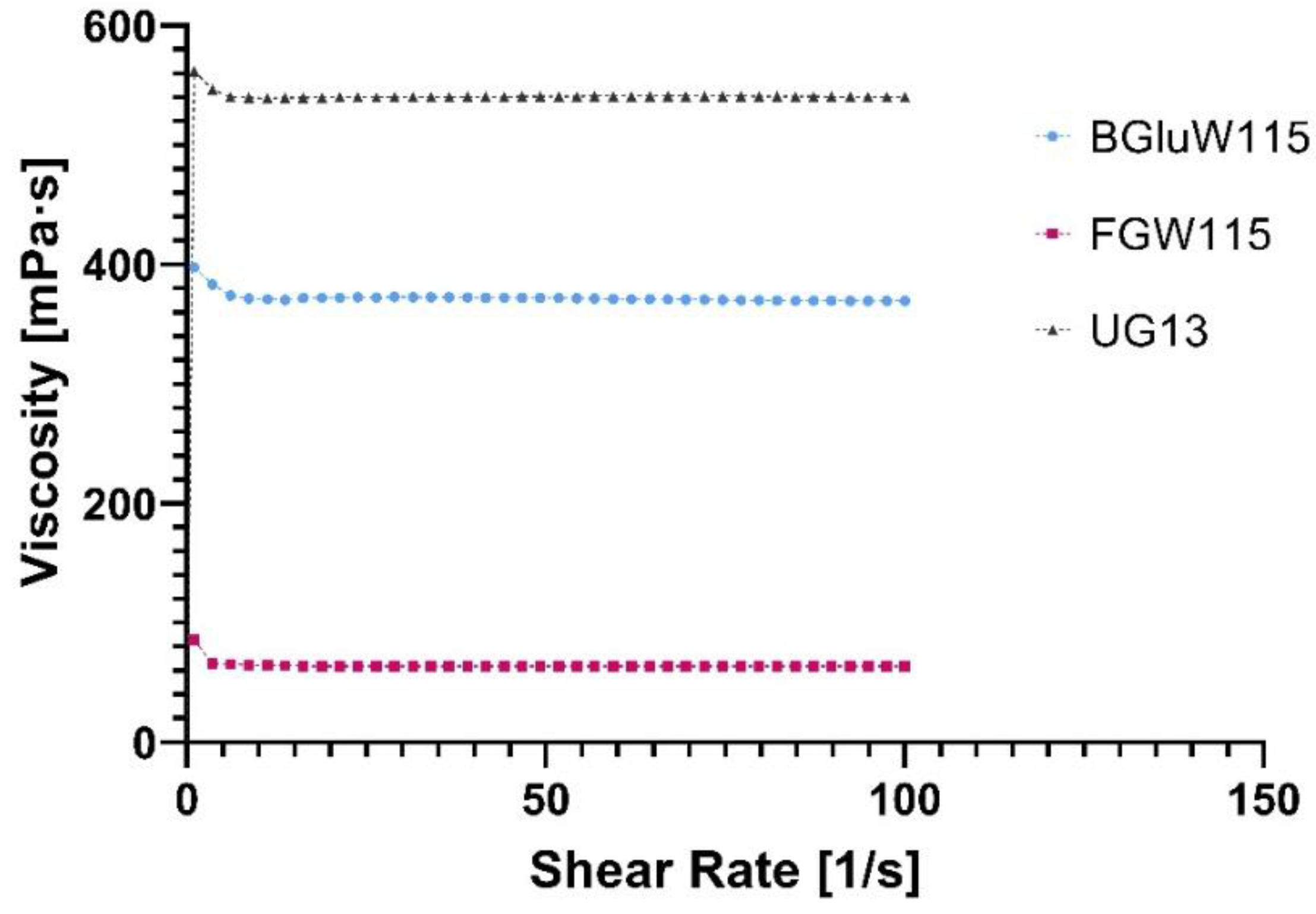

2.8. NaDES Physico-Chemical Parameters

Flow profile: The results obtained for each prepared and used Nades in all extractions are shown in

Figure 7.

Surface tension: Table 2 shows the results obtained from the force acting on the wettable ring because of the tension of the Nades sheet removed when removing the ring.

pH

Table 3.

pH of prepared Nades.

Table 3.

pH of prepared Nades.

| Nades |

pH |

Temperature (°C) |

| Fructose/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 |

7.38 |

22.0 |

| Betaine/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 |

8.44 |

21.8 |

| Urea/Glycerine 1:3 |

9.30 |

21.9 |

Conductivity

Table 4.

Conductivity of prepared Nades.

Table 4.

Conductivity of prepared Nades.

| Nades |

Conductivity (µS/cm) |

Temperature (°C) |

| Fructose/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 |

2.2 |

21.8 |

| Betaine/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 |

0.9 |

21.4 |

| Urea/Glycerine 1:3 |

1.4 |

21.4 |

2.9. Samples Physico-Chemical Parameters

Table 5.

Specific surface area of the macroalgae evaluated.

Table 5.

Specific surface area of the macroalgae evaluated.

| Sample |

SSA (m2/g) |

| Ceramium nitens |

0.034 |

| Dictyota menstrualis |

0.034 |

|

Dictyota cf. pulchella (127) |

2.289 |

|

Dictyota cf. pulchella (130) |

7.230 |

| Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis |

1.077 |

|

Hypnea sp. 1 |

6.001 |

|

Hypnea sp. 2 |

2.295 |

| Pterocladiella capillacea |

1.139 |

|

Sargassum cf. ramifolium

|

1.787 |

| Sargassum polyceratium |

1.058 |

| Solieria miliformis |

1.464 |

| Stypopodium zonale |

1.058 |

2.10. UV Preliminary Scanning

Additionally, UV scanning for FGW 1:1:5 (Fructose/Glucose/Water 1:1:5), BGW 1:1:5 (Betaine/Glucose/Water 1:1:5), and UG 1:3 (Urea/Glycerine 1:3), ethyl acetate, ethanol, water and 5% HCl solution extracts from samples of Ceramium nitens, Gracilaria cf. bursa-pastoris, Hypnea sp. 1, Hypnea sp. 2, Pterocladiella capillacea, Sargassum cf. ramifolium, Sargassum polyceratium, Solieria filiformis and Stypopodium zonale was developed. Only Pterocladiella capillacea water, ethanol, BGW 1:1:5, and UG 1:3 extracts, displayed absorption maximum between 320-330 nm.

2.11. Identification of MAAs by UHPLC-DAD

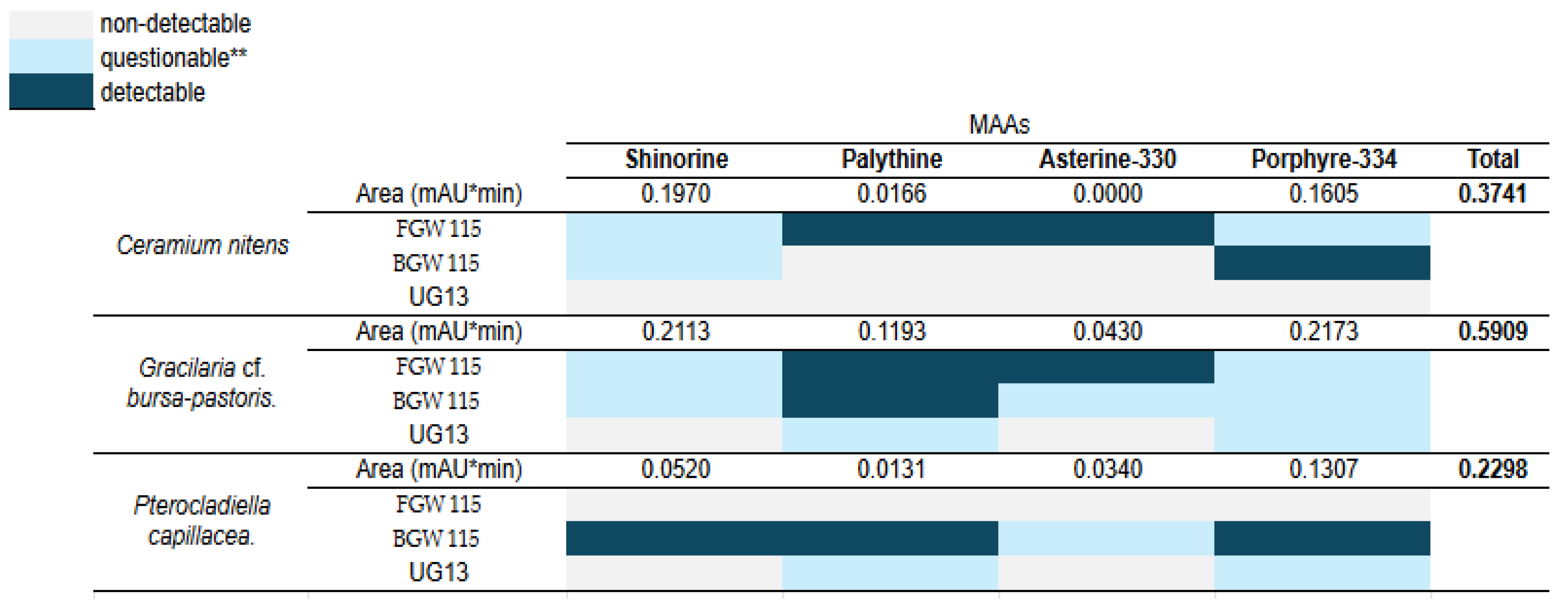

The results from the identification of MAAs, as shown in the heatmap (

Figure 8), provide a detailed view of their abundance based on the calculated areas. Notably, each species exhibited the presence of at least two out of the four MAAs: Shinorine, palythine-330, asterine-330, and Porphyra-334. The results from MAAs detection in macroalgae samples highlight the performance of various extraction methods.

Using water extraction (with the mobile phase in UHPLC-DAD analysis), all species exhibited detectable levels of shinorine, palythine-330, asterine-330, and Porphyra-334. Peak area estimations revealed that

Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis had the highest total MAA content, significantly surpassing that of

Ceramium nitens and

Pterocladiella capillacea. This method demonstrated effectiveness and consistency in detecting MAAs [

34]

In contrast, extraction with Nades FGW 115 yielded variable results. Palythine, asterine-330 were detected in G. cf. bursa-pastoris and C. nitens, but P. capillacea showed no detectable MAAs. Similarly, Nades BGW 115 exhibited selective detection, identifying shinorine, palythine, and Porphyra-334 in P. capillacea while providing questionable results for other species. Finally, Nades UG 13 proved to be the least effective, with no detectable MAAs in C. nitens and only questionable results for G. cf. bursa-pastoris and P. capillacea. This suggests that Nades UG 13 may not be suitable for extracting MAAs from these macroalgae.

3. Discussion

3.1. Samples

The selection of macroalgae samples was based on representative species from the coastal waters around Colombia, and all specimens collected belong to brown or red macroalgae group. In fact, these samples can provide various compounds at different quantities and for that, research on identification of their bioactive compounds can be seen as an almost unlimited field, hence, the approach of compound analysis was directly associated to the results of preliminary chemical screening prior to extraction with Nades.

3.2. Preliminary Chemical Screening

Preliminary chemical screening shows that all analysed samples contain phenolics, terpenoids and polysaccharides. These results agree with previously reported studies which also include these compound classes [

14,

15,

35].

3.3. Preparation of NaDES

Natural deep eutectic solvents (Nades) are a sustainable alternative to traditional organic solvents due to their low toxicity, biodegradability, and ability to solubilize bioactive compounds like phenolic compounds. In this case, three Nades with different compositions were analysed, including combinations of carbohydrates, betaines, and urea with water or glycerol, highlighting the following characteristics of each.

3.3.1. Fructose, Glucose, and Water (1:1:5)

The sugar-water mixture allows for a high solubilization capacity of polar compounds like phenolic compounds due to the strong hydrogen-bond interactions between sugar molecules and water, thus enhancing extraction efficiency. This Nades tends to be less viscous than other Nodes without water, which facilitates handling and application in extraction processes, therefore improving its practicality. The presence of water reduces viscosity, allowing better solvent diffusion into the macroalgae matrix, thereby enabling more efficient compound extraction. Furthermore, being a sugar-rich mixture, this Nodes can interact well with polar compounds, such as phenolic acids, which are highly soluble in hydrogen-rich solvents with a high hydrogen-bonding capacity.

3.3.2. Betaine, Glucose, and Water (1:1:5)

Betaine is a highly hydrophilic substance that interacts well with polar compounds and enhances the stability of the extracted compounds, thus making it highly effective for phenolic extraction. The addition of glucose increases the solubilization capacity for phenolic compounds, therefore broadening the range of compounds that can be extracted. Moreover, Betaine can stabilize proteins and other biomolecules, making this Nodes not only capable of solubilizing phenolic compounds but also preserving their active structure.

3.3.3. Urea and Glycerol (1:3)

Urea, as a hydrogen bond donor, interacts strongly with glycerol, which contains three hydroxyl groups, therefore creating a structure with high capacity to stabilize polar compounds. This Nodes is significantly more viscous than the others due to the absence of water and the dense nature of glycerol, consequently requiring more careful handling during extraction. The combination of urea and glycerol has a strong polar character, which gives it a high capacity to extract polar or moderately polar compounds, such as phenolic compounds. Nevertheless, the lack of water could limit its ability to solubilize highly polar compounds. In addition, this Nodes can form complexes with the amino and carbonyl groups of phenolic compounds, facilitating their extraction.

3.4. Extraction of Macroalgae with NaDES

Fructose/Glucose/Water (1:1:5): the presence of water significantly reduced the viscosity, allowing the solvent to penetrate more easily into the macroalgal matrix, facilitating the extraction process. This solvent is particularly effective for polar phenolic compounds, which form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of both fructose and glucose. In the context of the 12 macroalgal matrices, this Nodes have shown variable efficiency.

Betaine/Glucose/Water (1:1:5): the inclusion of betaine in the Nodes composition introduced a highly hydrophilic component with strong affinity for polar compounds, enhancing the solubilization of phenolic compounds. Betaine’s zwitterionic nature allows it to stabilize both polar compounds and biomolecules, offering potential for a wider range of extractions compared to the fructose/glucose/water system. This solvent has similar viscosity-reducing benefits due to the presence of water, improving its diffusion into the macroalgal matrix. In comparison to the fructose-based Nodes, betaine/glucose/water have exhibited superior performance for the extraction of phenolic compounds containing amino or carboxyl functional groups, given betaine’s ability to interact with these moieties.

Urea/Glycerol (1:3): in contrast to the sugar- and water-based Nodes, the urea/glycerol solvent has distinct properties due to its composition. Urea functioned as a hydrogen bond donor, interacting with the hydroxyl groups of glycerol to form a highly polar medium. The absence of water increased the viscosity of the solvent, which might have hindered its ability to diffuse into the macroalgal matrix efficiently, but the strong polar character compensated by enhancing the solubility of moderately polar phenolic compounds. Urea also formed complexes with the carbonyl and amino groups of phenolic compounds, promoting their extraction. However, due to its lack of water, this Nodes had limitations in extracting highly polar compounds, which probably were more efficiently solubilized by the other two Nodes systems.

3.5. Phenolic Content Determination by the Folin-Ciocalteau Method

Figure 1. shows the results of the determination of the content of phenolic compounds extracted with water, for the samples studied. The phenolic compounds were extracted from all samples. The highest yields are observed for both samples of the genus Sargassum.

In

Figure 2 the samples containing most phenolic compounds correspond to values between 3 and 4 %w/w for the species

Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis, the two samples of

Hypnea sp.,

Pterocladiella capillacea and

Stypopodium zonale using HCl 5% solution as the extractor solvent.

Figure 3 shows the results for phenolic compounds quantitative content, using three Nades: FGW 1:1:5 (Fructose/Glucose/Water 1:1:5), BGW 1:1:5 (Betaine/Glucose/Water 1:1:5), and UG 1:3 (Urea/Glycerine 1:3). For all samples the higher phenolic compounds content is yielded with BGW 1:1:5, with exception of

Gracilaria sample which higher content is with UG 1:3. When comparing these results with results for water extracts (

Figure 1), the samples with higher phenolic compounds contents are also

Sargassum and

Dictyota, however Nades BGW 1:1:5 extracts overcome to water extracts. For

Dictyota pulchella the extraction increases in a radio of 2.11 with Nades, and for

Sargassum ramifolium increase 1.42. In all the other samples Nades BGW 1:1:5 overcome water extraction in different radios between 1.1 to 2.4.

Among the three Nades assessed (

Figure 3), the Betaine/Glucose/Water 1:1:5 (BGluW115) exhibited the greatest capacity for phenolic compound extraction compared to Fructose/Glycerine/Water 1:1:5 (FGW115) and Urea/Glycerine 1:3 (UG13). Using the BGluW115 composition, the samples containing the highest number of phenolic compounds are

Sargassum polyceratium with values between ~ 2 and 2.8%,

Dictyota sp. with values between 1.14-1.9% being DP127 and DP120. The most compounds of the three samples of this genus,

Ceramium nitens and

Pterocladiella capillacea with 1.2% and

Stypopodium zonale with 1.1%.

Comparing all the three extraction systems used (water, 5% HCl solution and Nades), the 5% HCl solution overcomes water and Nades systems, maybe by hydrolysis processes that can take place during extraction processes.

3.6. Estimation of the Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Quantified Extracts by DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl)

In Table 1 it is observed that the extract of BGW 115 contains 2.05% of extracted phenolic compounds, its DPPH radical scavenging activity is 97.63%. It is also possible to observe that with the three Nades extracts, the highest the amount of phenolic content extracted, the anti-radical activity DPPH is increased.

3.7. Pre-Scaling

The pre-scaling tests results are included in

Figure 6. It is observed with the solvent Nades BGluW115 an increase in the percentage of phenolic compounds extracted as the extraction time elapses, obtaining values close between 1.0% and 2.0% since 24 - 54 hours of extraction.

Figure 6. shows slight differences between phenolic content values within and between extraction series; the internal differences are due to the change in the time of hours of sample extraction. Total solvent volume influences slightly the extraction, because increasing the volume of Nades appears to have a positive effect on the percentage of phenolic compounds extracted from dry material, the difference between 10 mL, 20 mL and 50 mL volumes is relatively small. Although a slightly higher yield is observed with 50 mL, this increase is not drastic. This suggests that, after a certain volume, the solvent’s ability to extract more phenolic compounds stabilizes, and an increase in the volume of solvent does not result in a proportionally significant improvement. During the first 30 hours of extraction, 10 mL and 20 mL volumes show remarkably similar percentages of phenolic compounds. This indicates that for short extraction times (up to 30 hours), the volume of solvent does not appear to be a determining factor in the extraction efficiency of phenolic compounds, suggesting that an excessive volume of solvent is not necessary to obtain good returns within this time range.

As it is observed in

Figure 6, applying a two-way ANOVA Post hoc test in GraphPad Prism, the Nades extraction yields oscillate in a very closed range around 1.0% of phenolic compounds, thus, that results indicate there are almost no variations and that were verified statistically (p > 0.9999). This common behaviour was not expected according the extremely high Nades viscosity differences (p < 0.0001), 64.2 [mPa·s] for FGW115, 372.1 [mPa·s] for BGluW115 and 541.0 [mPa·s] for UG13. Accordingly, the extraction process has a high potential to be robust in a wide range of viscosities. This variable establishes the experimental basis to develop the extraction method validation.

3.8. NaDES Physico-Chemical Parameters

Flow profile: Figure 7. shows the relationship between viscosity versus shear rate of the three Nades prepared. The graph shows that Nades prepared have a Newtonian behaviour because it is observed that their respective viscosities can be considered as constant over time, due to the linear behaviour identified in the graph. This implies that its viscosity is the same for all shear speeds applied to the fluid and depends on the temperature and pressure that is applied to it. As for their viscosity, it is observed that the order of higher to lower viscosity in Nades is UG13 > BGluW115 > FGW115. This viscosity is important because it influences the rate of diffusion of metabolites in the sample at the time of extraction.

Surface tension: all three Nades had higher surface tension values than the theoretical water value (

Table 2), which can be corroborated that due to the electrostatic attraction between the components of the solvent, they led to the formation of hydrogen bonds between them, the cohesive forces between the molecules that make up these solvents are very strong. The surface tension value allows to evaluate in the Andes important physicochemical parameters in the cosmetic area as the wettability, indicating that like water (surface tension 72.7 mN/m at 293 K), it is dispersed, flows through surfaces and has a small three-dimensional height, nevertheless hardly penetrates small spaces.

pH: in

Table 3, the pH values of the Nades varied significantly. The fructose/glucose/water mixture exhibited a neutral pH of 7.38, indicating a balanced environment that is typically conducive to the solubilization of a wide range of compounds, including phenolic compounds. In contrast, the betaine/glucose/water Nades had a higher pH of 8.44, suggesting a more alkaline environment. This increase in pH could have enhanced the solubility of certain phenolic compounds, particularly those with acidic functional groups, due to the deprotonation of hydroxyl groups, thus facilitating their extraction. The urea/glycerine NaDES presented the highest pH at 9.30, which may indicate a strong basic character. This high pH environment could promote the extraction of specific polar compounds, potentially altering their chemical state and enhancing their solubility. However, the elevated pH may also pose risks, as it could lead to the degradation of sensitive biomolecules during the extraction process.

Conductivity:

Table 4 reveals the conductivity measurements, which reflect the ionic strength and overall electrochemical environment of the Nades. The fructose/glucose/water Nades showed the highest conductivity at 2.2 µS/cm, which aligns with its neutral pH. This increased conductivity indicates a higher concentration of ions in solution, which can enhance the solubilization capacity for polar compounds. Conversely, the betaine/glucose/water Nades exhibited lower conductivity at 0.9 µS/cm. This reduced conductivity may be attributed to the unique interactions of betaine with water and glucose, potentially leading to a more stabilized environment for solubilizing compounds without a significant ionic presence. The urea/glycerine Nades had a conductivity of 1.4 µS/cm, which falls between the other two Nades. This suggests a moderate ionic environment, potentially allowing for effective extraction while avoiding excessive ionic interactions that could hinder the solubilization of certain compounds.

3.9. Samples Physico-Chemical Parameters

The size and shape of the particles of the powder obtained by mechanical grinding of the sample of Sargassum polyceratium. showed that the samples simultaneously presented diversity of sizes, ranging from large particles to fine particles. As far as their appearance is concerned, most particles are irregular and amorphous in shape and size, and a little quantity have different geometries (data not shown) due to it is not applied grinding control by particle-size reduction procedures such as bead mill, mortar, pestle, and shearing, in order to guarantee solid samples homogenization. As expected, morphological heterogeneity was present in the sample, implying that this factor could probably have a decisive impact on the extraction of metabolites with the solvent Nades since theoretically, the size and shape of solutes influence the diffusion processes generated in the extractions. In this case, the most recommended is to reduce the size of the particles, to increase the effectiveness of the extraction, because by decreasing the size of the particles, the diffusion path is reduced and the solvent contact area is increased, resulting in an accelerated extraction process. In addition, irregularity and amorphism affect the reproducibility of experimental procedures because the ratio of solvent to sample is variable, causing variation in the yields of extractions.

As regards porosity, the calculated specific surface area values shown in

Table 3 revealed very low values of this parameter, indicating that the particle size is large [

36,

37]; on the other hand, if the specific surface area of the material is related to its porosity [

36,

38], it could be said that the samples are not porous or have no significant porosity, due to the low surface area values obtained, that lead to the proposition that these values could be attributed to spaces formed between the particles (intergranular pore), that is, a textural porosity [

39]. This can be assumed because the higher the porosity, the greater the adsorption capacity of the material, as porosity is one of the most influential factors in the interactions and chemical reactivity of materials with gases and liquids [

36,

40], and therefore large values of specific surface area would be obtained.

3.10. UV Preliminary Scanning

For mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs), only extracts made with water and Nades FGW 1:1:5, BGW 1:1:5 and UG 1:3; displayed an absorption maximum between 324-326 nm, which is characteristic for mycosporine-like amino acids, MAA absorption maxima are between 268 and 362 nm, depending on their molecular structure [

41].

Pterocladiella capillacea water, ethanol, BGW 1:1:5, and UG 1:3 extracts, displayed absorption maximum between 320-330 nm, this absorption is characteristic for mycosporine-like amino acids as reported [

41].

3.11. Identification of MAAs by UHPLC-DAD

The variability in the content of MAAs among macroalgal species is also influenced by the time of year, as indicated by the study of Urrea-Victoria et al. [

34], among others. During different periods of the year, MAAs concentrations in species collected from the Colombian Caribbean showed significant variations. For example,

Ceramium rubrum exhibited 2.08 mg.g

-1 DW of shinorine, while

Gracilaria sp. presented concentrations of palythine up to 56 mg.g

-1 DW, asterine up to 0.39 mg.g

-1 DW, and P-334 up to 8.44 mg.g

-1 DW. These differences reflect how environmental variations affect MAA production in macroalgae. These results underscore the importance of Gracilariales and Ceramiales species in MAAs production, particularly for sunscreen development.

In the present study, MAAs concentrations ranged from 0.2 to 0.5 mg.g-1 DW in the species analysed with aqueous extractions. Future studies should focus on optimizing drying processes and collection times to enhance MAA production. Additionally, among Nades extraction methods, both FGW 115 and BGW 115 effectively detected MAAs, whereas UG 13 did not. These findings highlight the need to adjust extraction methods based on the specific characteristics of each macroalga and the MAA of interest, emphasizing the importance of optimizing techniques for cosmetic and biotechnological applications.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Samples

Macroalgae samples were collected in the north-east coastal areas of Colombia. The collection permits were granted by the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible by Permission No 121 of January 22 of 2016 (modification otrosí No 7) for research permission of marine samples. In order not to exhaust the biological resources, the most significant data were collected in Table 1.

Table 1.

Macroalgae samples studied with assigned code for analysis, species, collection dates and collection sit.es.

Table 1.

Macroalgae samples studied with assigned code for analysis, species, collection dates and collection sit.es.

| Group |

Specie |

Order |

Family |

Collection date |

Collection site |

Voucher number |

Brown

macroalgae |

Dictyota menstrualis |

Dictyotales |

Dictyoptaceae |

26/09/2021 |

Providencia |

JIW00004951 |

|

Dictyota cf. pulchella

|

Dictyotales |

Dictyoptaceae |

26/09/2021 |

Providencia |

JIW00004956 |

|

Dictyota cf. pulchella

|

Dictyotales |

Dictyoptaceae |

26/09/2021 |

Providencia |

JIW00004952 |

|

Sargassum cf. ramifolium

|

Fucales |

Sargassaceae |

01/03/2021 |

Guajira |

JIW00004940 |

| Sargassum polyceratium |

Fucales |

Sargassaceae |

01/02/2021 |

San Andrés |

JIW00004945 |

| Stypopodium zonale |

Dictyotales |

Dictyotaceae |

03/03/2021 |

Guajira |

JIW00003294 |

Red

macroalgae |

Ceramium nitens |

Ceramiales |

Ceramiaceae |

28/02/2021 |

Guajira |

JIW005012 |

| Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis |

Gracilariales |

Gracicilariaceae |

01/03/2021 |

Guajira |

JIW005011 |

|

Hypnea sp. 1 |

Gigartinales |

Cystocloniaceae |

01/03/2021 |

Guajira |

ND*

|

|

Hypnea sp. 2 |

Gigartinales |

Cystocloniaceae |

28/02/2021 |

Guajira |

ND*

|

| Pterocladiella capillacea |

Gelidiales |

Pterocladiaceae |

01/03/2021 |

Guajira |

JIW005015 |

| Solieria filiformis |

Gigartinales |

Solieriaceae |

04/03/2021 |

Guajira |

JIW0005029 |

The fresh samples were washed with sea water and dried by sun exposure for twelve hours. Finally, the samples were dried one last time on the stove at 40°C for 48h. Each sample was ground, and the resulting material was stored in dry bottles protected from light and heat and duly labelled.

4.2. Preliminary Chemical Screening

Each of the dried and ground samples was extracted successively with 10.0 mL of ethyl acetate, ethanol and water weighing 1.0 g of sample. Each sample was separately extracted with 10.0 mL of 5% HCl solution. Ethyl acetate extracts were analysed by thin layer chromatography to determine the presence of low polarity substances, and the extract also determined the presence of phenolic compounds. In turn, extracts in ethanol, water and 5% HCl solution were evaluated to determine the presence of phenolic compounds, polysaccharides, and alkaloids, respectively.

An ultrasonic bath at 40°C for ethyl acetate and 60°C for other solvents was used for all extractions. For the phenolic compound test, 1.0 mL of filtered supernatant of the extracts was used by adding respectively to each tube 2-3 drops of ferric chloride reagent (FeCl3 at 1% aqueous); for the alkaloid test, 1.0 mL of filtered supernatant of the aqueous acid extract (5% HCl solution) was used by adding 2-3 drops of the Wagner reagent (I2+KI in water); finally, 1.0 mL of filtered supernatant from aqueous and aqueous acid extracts (5% HCl solution) was used to detect the presence of polysaccharides by precipitation by adding excess analytical grade ethanol. From the filtrate N°1 obtained from the individual extraction of 1.0 g of sample of each species of macroalga with 10.0 mL of ethyl acetate, the analysis was conducted by thin layer chromatography on silica gel using as eluting system: 4:1 hexane/ethyl acetate, and cholesterol as reference standard. Subsequently, the filtered extract was concentrated in the rotary evaporator to obtain a more efficient seeding in the chromatographic plate, which was done in triplicate with each of the samples in the TLC plate. Once the plate was eluted, it was revealed using UV light at a wavelength of 254 nm and 360 nm (short and long length respectively) and finally revealed with phosphomolybdic acid followed by heating at 105°C.

4.3. Preparation of the NaDES

After conducting the search for the different Nades reported in the literature as effective solvents in the extraction of phenolic compounds or cosmetic applications, discarding choline chloride as a restricted substance in the preparation of cosmetic products, three Nades were prepared with the following compositions: urea/glycerine 1:3 (UG 13) [

42], fructose/glucose/water 1:1:5 (FGW 115) and, betaine/glucose/water 1:1:5 (BGluW 115) [

11]. The mixture of the components was prepared with calculated quantities to obtain 50 g of solvent. Each component was added in an erlenmeyer and a magnetic stirrer: UG 13: 10 mL glycerine (99.5% Sigma Aldrich) + 13.2 g urea; FGW 115: 12.7 g fructose + 19.7 mL glycerine (99.5% Sigma Aldrich) + 12.5 mL deionized water; BGluW 115: 23.3 g betaine + 23.3 g glucose + 11.7 mL deionized water. Subsequently each mixture was heated between 50-55 °C with constant magnetic agitation to form a colourless liquid (estimated time: 30-90 min approx.).

4.4. Extraction of Macroalgae with NaDES

Twelve samples of marine macroalgae mentioned in Table 1, were obtained and prepared for extraction. Each sample was weighed separately in 15.0 mL falcon tubes, 100 mg dry weight and ground sample. Each sample was independently added 1.5 mL of Nades solvent, water and 5% HCl solution to obtain 5 extracts for the same alga sample: three individual extracts of each alga for each Nades solvent (FGW115, BGluW115 and UG13) and two extracts with each of the reference solvents (water or 5% HCl solution). Subsequently, ultrasound-assisted extraction was performed for 60 min at 60°C. Each extraction was performed in triplicate.

4.5. Phenolic Content Determination by the Folin-Ciocalteau Method

A microplate reader of 96 Synergy H1 wells was used. The analysis extracts were from the samples: Sargassum cf. ramifolium, Sargassum polyceratium, Stypopodium zonale, Pterocladiella capillacea, Solieria filiformis, Ceramium nitens, Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis, Hypnea sp. 1, Hypnea sp. 2, Dictyota menstrualis (DP120) and Dictyota cf. pulchella (DP127 and 130) obtained in each of the prepared Nades (Fructose/glycerin/water 1:1:5 FW115, Betaine/glucose/water 1:1:5 BGluW115 and urea/glycerine 1:3 UG13).

Evaluated 10 μL of the extract and added 30 μL of Na2CO3 solution at 20%, 245 μL of deionized water and 15 μL of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent. The measurements were taken by triplicate. Also, the target was composed of the reagents mentioned above, 10 μL of the corresponding solvent and without the presence of extract. The reading was made at 760 nm at normal temperature and pressure. For pre-scalation extracts, 30 μL of the extract was evaluated and 30 μL of Na2CO3 solution 20%, 225 μL of deionized water and 15 μL of Folin reagent were added. Measurements were taken in triplicate. The reading was made at 760 nm at normal temperature and pressure.

4.6. Estimation of the Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Quantified Extracts by DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl)

The DPPH free radical scavenging activity uptake method was used with modifications. In microplates of 96 wells, 10 μL of the extracts of Sargassum cf. ramifolium and Sargassum polyceratium and added 10 μL ethanol and 280 μL DPPH solution 2000 μg/mL. The samples were incubated in the dark for 40 minutes at room temperature and the absorbance was read at 517 nm. 3 targets were prepared: the solvent target, the DPPH target, and the sample target. Ascorbic acid was used for comparison. The measurements were taken by triplicate.

4.7. Pre-Scaling

For the scaling tests, small sample sizes were used to decrease the resistance to mass transfer to the solvent, for this an N°20 sieve with opening of 850 μm (NTC 32 A.S.T.E 11-87) was used.

For the initial tests, 1.0 g of dry and ground sample of algae Sargassum polyceratium was weighed, 10 mL of Nades betaine solvent/glucose/water 1:1:5 (BGluW115) was added. The test evaluated two different references of solvent components. Extraction was performed with constant agitation using a mechanical agitator at 60°C. Extract samples were taken after 1h, 2h, 4h, 24h, 29h extraction. On the other hand, 1.0 g of dry and ground sample of Sargassum polyceratium, 10 mL, 20 mL, and 50 mL of Nades betaine/glucose/water solvent 1:1:5 was added (BGluW115). Extraction was performed with a mechanical agitator at 60°C, taking extract samples after 6h, 24h, 30h, 48h and 54h extraction.

4.8. NaDES Physico-Chemical Parameters

Nades flow profile: The rheological behavior of prepared Nades was observed by performing viscosity experiments in a rheometer (MCR92, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) and using a cone and plate geometry (diameter 1 inch) at 25°C. Samples were directly measured without dilution. Each Nades was individually poured into the geometry up to the mark shown for a defined volume. The computer program parameters were subsequently set to zero to illustrate the measurements as a function of increased shear rate and viscosity. The rheometric profile of viscosity versus shear rate of the three Nades prepared was used to predict the rheological behavior of the liquids obtained.

Nades surface tension: Surface tension measurements were conducted using the Du Noüy ring method at a temperature of 23°C approx. using a Krüss K8 tensiometer (KRÜSS GmbH, Hamburg, Germany; Iridium-Platinum ring). The ring was immersed in 5.0 mL of Nades solvent and gradually lifted above the surface. The maximum value of the force at ring detachment determined the surface tension of the interface. Each Nades was subjected to three measurements.

pH: The pH determination of Nades was conducted by an electrometric method, using a Metrohm pH meter model 780, integrated with a pH electrode with Metrohm temperature sensor Pt 1000 model 6.0258.600 that supports viscous and alkaline samples. This equipment was calibrated and inspected with three pH buffer solutions HI7004 pH 4.01, HI7007 pH 7.01 and HI7010 pH 10.01 at 25 °C. In each measurement, a sufficient portion of prepared Nades was extracted without any kind of pre-treatment, until the electrode bulb is completely covered; during measurement, the solvent was kept continuously and gently agitated and the reading recorded when a stable pH value was obtained.

Conductivity: The determination of the conductivity of Nades was conducted with a SCHOTT® instruments brand conductometer model Lab 960 with a 4-pole graphite conductivity cell SCHOTT® instruments brand LF413T. It was calibrated and verified with certified reference material for electrolytic conductivity measurement 0.001 mol/L (nominal 0.146 mS/cm) brand Merck of the Certipur® line. At each measurement, a sufficient aliquot of prepared Nades was extracted without any pre-treatment until the cell was completely covered, gently stirred and conductivity and temperature were recorded.

4.9. Samples Physico-Chemical Parameters

Porosity: for the determination of porosity, the specific surface area was calculated based on the BET model with data from the gas adsorption isotherm obtained in the equipment. Nitrogen adsorption isotherms were conducted at 77 K using a Nova 1200e (Quantachrome Instruments, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) with Novawin software. To remove any trace of gas before the experiment, all samples were degassed for 6 h at 150°C under secondary vacuum (30 mmHg). The equilibrium conditions were achieved when no difference greater than 0.9 mmHg was recorded for at least 390 s.

4.10. UV Preliminary Scanning

A UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis was performed in microplates of 96 wells, by means of a spectral sweep of 200 to 400 nm of 10 μL of the extracts of the samples Ceramium nitens, Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis, Hypnea sp. 1, Hypnea sp. 2, Pterocladiella capillacea, Sargassum cf. ramifolium, Sargassum polyceratium, Solieria filiformis and Stypopodium zonale in all solvents of interest. Water and dilution of the Nades solvent in which the extract was found was used as a negative control. A positive control of MAAs was not available.

4.11. Identification of MAAs by UHPLC-DAD

MAAs extraction was performed according to the method described by Urrea-Victoria et al. [

34]. Briefly, samples of 5 mg freeze-dried weight were spiked with 1 mL of acidified water (0.25% formic acid and 20 mM ammonium formate) and mixed thoroughly and for Nades extract was employed 30 mg DW with 2 mL of acidified water (Extracted in a water bath at 60 °C with ultrasound for 2 h). The samples were then extracted using an ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic Easy 37 kHz, Germany) for 15 min at room temperature. After extraction, the tubes were centrifuged at 1500 x g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 µm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) hydrophilic syringe filters (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) and transferred to vials [

34]

An aliquot of 5.0 μL of each filtered extract was injected into a Synergi Hydro-RP 80 Å (4 μm, 150 x 2.0 mm) column, protected by a Security Guard precolumn. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min at 22 °C. The gradient system combined an aqueous solution of 0.25% formic acid and 20 mM ammonium formate (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). It started with 100% A (0-3 min), followed by 95% A (3-7 min), 20% A (7-8 min). The re-equilibration duration between individual runs was 5 min. The detection wavelengths were 330 nm.

5. Conclusions

The extractions with Nades solvents obtain favorable results regarding the phenolic content of samples with species of Sargassum and Dictyota for the Nades BGluW115 and FGW115, as well as Gracilaria and Dictyota with the Nades UG13. Notably, the best phenolic compound extraction (expressed as %w/w) was achieved using the reference solvent HCl 5% compared to water and the used Nades solvents; furthermore, the best phenolic compound extraction using Nades solvents was with BGluW115. Likewise, the higher anti-free radical activity DPPH and the higher content of phenolic compounds for samples of Sargassum polyceratium were observed with the Nades betaine/glucose/water 1:1:5 (BGluW115) solvent. In addition, methods of isolation and identification of MAAs can be explored for the sample of Pterocladiella capillacea, which may contain cyclohexenimine-type MAAs such as Palythine, that have an absorption maximum at 320 nm. The variation in the references of the components of the BGluW115 solvent provided an indication of its reliability, since reproducibility of the results was obtained by performing the method on the same sample under varying operating conditions. Regarding the extraction resolution, it was improved by increasing the time of exposure of the sample to the solvent, which was favored by the reduction in viscosity of Nades BGluW115 due to temperature, so that mass transfer was maximized.

When the solvent is water, the best yield is obtained with samples of algae of the genus Sargassum. However, when the solvent extractor is 5% HCl, the best yield is obtained with the algae samples of Gracilaria, Hypnea, Pterocladiella, and Stypopodium.

The control of the proposed method was established by the limits of acceptable variability of the detector response to phenolic compounds. Specifically, these showed a lower limit (LI) of 484.44 mg/L of phenolic compounds and an upper limit (LS) of 13511.11 mg/L for 10 mL BGluW115. Despite advances in synthetic chemistry, macroalgae remain a major source of secondary metabolites, which, thanks to their chemical characteristics, are promising candidates for natural sunscreen and other cosmetic applications.

Furthermore, most sun protection compounds and UV sunscreens based on organic and/or inorganic compounds have shown adverse effects on the environment and combine with other sun protection chemicals to produce a product of “broad spectrum.” “However, some of these compounds show instability after a particular time. Therefore, the characteristics of MAAs provide a new opportunity in the search for an alternative source of natural sun protection compounds due to their excellent properties without causing harmful effects. Additionally, the morphology of the pulverized macroalgae was a crucial factor during extraction processes, indicating the need to homogenize particle size to obtain results with lower standard deviation. Finally, according to the calculated specific surface areas, macroalgae samples are poorly permeable as they have no relevant porosity. Consequently, the ability to absorb fluids in extraction processes is one of the factors influencing the extraction performance of phenolic compounds in most samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AM; methodology, AM., VU, VMT., CHS., SDA. , and JC.; resources, AM, DMM, LC., and JC.; writing—original draft preparation, AM and VMT; writing—review and editing, AM., VU., VMT., CHS., SDA., and JCR.; supervision, AM, DMM, and LC.; project administration, LC., DMM, AM, and JCR.; funding acquisition, AM., DMM., JC., and LC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, this work has received financial support from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Colombia (Minciencias) with resources from the “FONDO NACIONAL AUTÓNOMO DE FINANCIACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO PARA LA CIENCIA, LA TECNOLOGÍA Y LA INNOVACIÓN: FRANCISCO JOSÉ DE CALDAS”, the Jorge Tadeo Lozano University Foundation, the National University of Colombia and the University of Antioquia, within the framework of the contingent recovery financing contract 80740-739-2020 concluded between Fiduciaria la Previsora S.A. - Fiduprevisora S.A. acting as spokesperson and administrator of the national financing fund for science, technology and innovation, Francisco José de Caldas Fund and the National University of Colombia - Bogota Headquarters. Scholarship for graduate studies best graduate of the program of Chemistry 2019, Faculty of Exact Sciences, University of Antioquia, Resolution 3398 of 26/03/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are included in the article; further information can be request directly with the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the authors for their contributions to the research, data curation, and writing—reviewing and editing. Heartfelt thankful for the funding from Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Colombia (Minciencias), National University and University of Antioquia for sources and funding acquisition; Professor Nora Jiménez, Phytochemical Laboratory – University of Antioquia for assistance in phytochemical information and instrumental analysis; PhD Mariana Peñuela, Bioprocess Laboratory, Engineering Faculty – University of Antioquia for technological support in the UV spectra; PhD. Stefania Sut and members of Natural Products Laboratory - University of Padua, Italy, for providing access to their research projects and the assistance in data acquisition, analysis and technical support; Environmental Remediation and Biocatalysis (GIRAB) Laboratory in the data acquisition of physicochemical parameters; PhD Luis Fernando Giraldo, Polymer Research Laboratory (LIPOL) – University of Antioquia for assistance in physicochemical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Nades |

Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| FGW115 |

Fructose/glycerine/water 1:1:5 |

| BGluW115 |

Betaine/glucose/water 1:1:5 |

| UG13 |

Urea/glycerine 1:3 |

| MAAs |

Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids |

| UV-Vis |

Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy |

| UHPLC-DAD |

Ultra High-Performance Liquid

Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection |

| DPPH |

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| TLC |

Thin Layer Chromatography |

References

- Abbott, A.P.; et al. Deep eutectic solvents formed between choline chloride and carboxylic acids: versatile alternatives to ionic liquids. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2004, 126, 9142–9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, A.; et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents–solvents for the 21st century. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Espino, M.; et al. Natural designer solvents for greening analytical chemistry. TrAC trends in analytical chemistry 2016, 76, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents: cytotoxic profile. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents: properties, applications, and perspectives. Journal of natural products 2018, 81, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; et al. NaDES application in cosmetic and pharmaceutical fields: an overview. Gels 2024, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, M.; et al. Green profile tools: current status and future perspectives. Advances in Sample Preparation 2023, 6, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moermond, C.T.; et al. GREENER pharmaceuticals for more sustainable healthcare. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2022, 9, 699–705. [Google Scholar]

- Funari, C.S.; et al. Reaction of the phytochemistry community to green chemistry: insights obtained since 1990. Journal of Natural Products 2023, 86, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; et al. Major phytochemicals: recent advances in health benefits and extraction method. Molecules 2023, 28, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, C.; Virginie, C.; Boris, V. The use of NADES to support innovation in the cosmetic industry. In Advances in Botanical Research; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 309–332. [Google Scholar]

- Obluchinskaya, E.; et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents as alternatives for extracting phlorotannins from brown algae. Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal 2019, 53, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.N.; et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents for the extraction of phenyletanes and phenylpropanoids of Rhodiola rosea L. Molecules 2020, 25, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aina, O.; et al. Seaweed-derived phenolic compounds in growth promotion and stress alleviation in plants. Life 2022, 12, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. Seaweeds as source of bioactive substances and skin care therapy—cosmeceuticals, algotheraphy, and thalassotherapy. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Tarafdar, A.; Badgujar, P.C. Seaweed as a source of natural antioxidants: Therapeutic activity and food applications. Journal of Food Quality 2021, 2021, 5753391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obluchinskaya, E.D.; et al. Optimization of extraction of phlorotannins from the arctic Fucus vesiculosus using natural deep eutectic solvents and their HPLC profiling with tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.N.; et al. The impact of natural deep eutectic solvents and extraction method on the co-extraction of trace metals from Fucus vesiculosus. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wils, L.; et al. Alternative solvents for the biorefinery of spirulina: impact of pretreatment on free fatty acids with high added value. Marine drugs 2022, 20, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Hou, Y. Efficient purification of R-phycoerythrin from marine algae (Porphyra yezoensis) based on a deep eutectic solvents aqueous two-phase system. Marine drugs 2020, 18, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, C.; et al. Double valorization for a discard—α-chitin and calcium lactate production from the crab Polybius henslowii using a deep eutectic solvent approach. Marine drugs 2022, 20, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; et al. A concise review of the brown macroalga Ascophyllum nodosum (Linnaeus) Le Jolis. Journal of Applied Phycology 2020, 32, 3561–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.; et al. Extraction of macroalgae phenolic compounds for cosmetic application using eutectic solvents. Algal Research 2024, 79, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawoczny, A.; Gillner, D. The most potent natural pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food ingredients isolated from plants with deep eutectic solvents. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 71, 10877–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joarder, S.; et al. Bioinspired green deep eutectic solvents: preparation, catalytic activity, and biocompatibility. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 376, 121355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, J.; et al. Active pharmaceutical ingredient ionic liquid in natural deep eutectic solvents–influence of solvent composition. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 384, 122282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Exploring carbohydrate extraction from biomass using deep eutectic solvents: Factors and mechanisms. IScience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; et al. Green and efficient extraction of wormwood essential oil using natural deep eutectic solvent: Process optimization and compositional analysis. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 382, 121977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, R.; Tan, Z. Extraction and purification of grape seed polysaccharides using pH-switchable deep eutectic solvents-based three-phase partitioning. Food Chemistry 2023, 412, 135557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taweekayujan, S.; Somngam, S.; Pinnarat, T. Optimization and kinetics modeling of phenolics extraction from coffee silverskin in deep eutectic solvent using ultrasound-assisted extraction. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletta, A.; et al. Separation of phenolic compounds from water by using monoterpenoid and fatty acid based hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 381, 121806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosielski, B.; Warminska, D.; Cichowska-Kopczynska, I. CO2 separation using supported deep eutectic liquid membranes based on 1, 2-propanediol. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11, 4093–4105. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R.; et al. Green extraction techniques of bioactive compounds: a state-of-the-art review. Processes 2023, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea-Victoria, V.; et al. Mycosporine-like-amino acids profile in red algae from high UV-index geographical areas (San Andrés Island and La Guajira) of the Colombian Caribbean coast. Algal Research 2025, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Tarafdar, A.; Badgujar, P.C. Seaweed as a source of natural antioxidants: Therapeutic activity and food applications. Journal of Food Quality 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinal, L. Porosity and its measurement. In Characterization of Materials; 2002; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell, S.; Shields, J.E. Powder surface area and porosity; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowski, A. Adsorption—from theory to practice. Advances in colloid and interface science 2001, 93, 135–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, J.R. Porosity and pore size distribution. Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment 2004, 3, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Rouquerol, J.; et al. Recommendations for the characterization of porous solids (Technical Report). Pure and applied chemistry 1994, 66, 1739–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, V.; Pinto, E. Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs): Biology, chemistry and identification features. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alishlah, T.; Mun’im, A.; Jufri, M. Optimization of urea-glycerin based NADES-UAE for oxyresveratrol extraction from Morus alba roots for preparation of skin whitening lotion. Journal of Young Pharmacists 2019, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).