Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

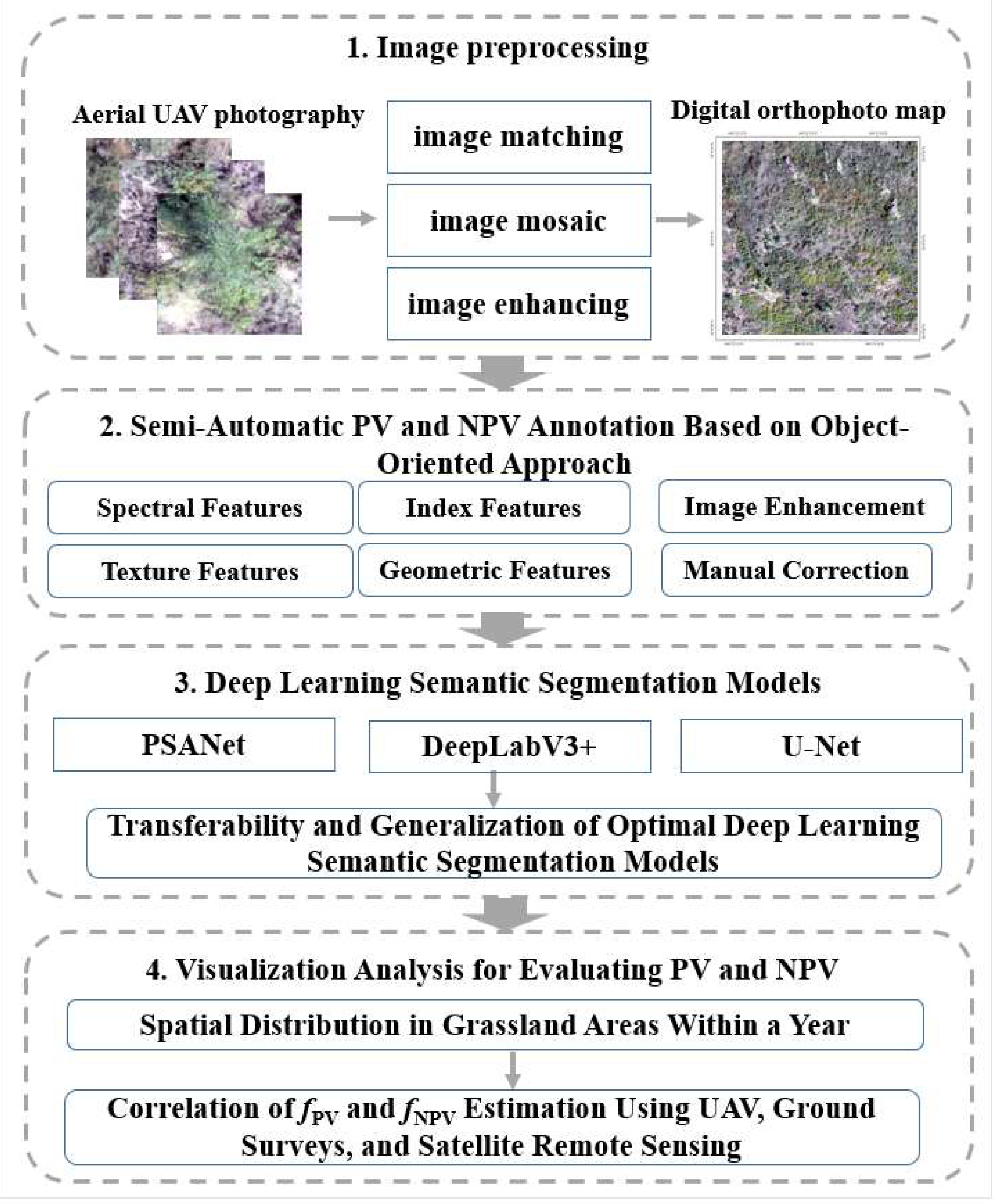

2. Materials and Methods

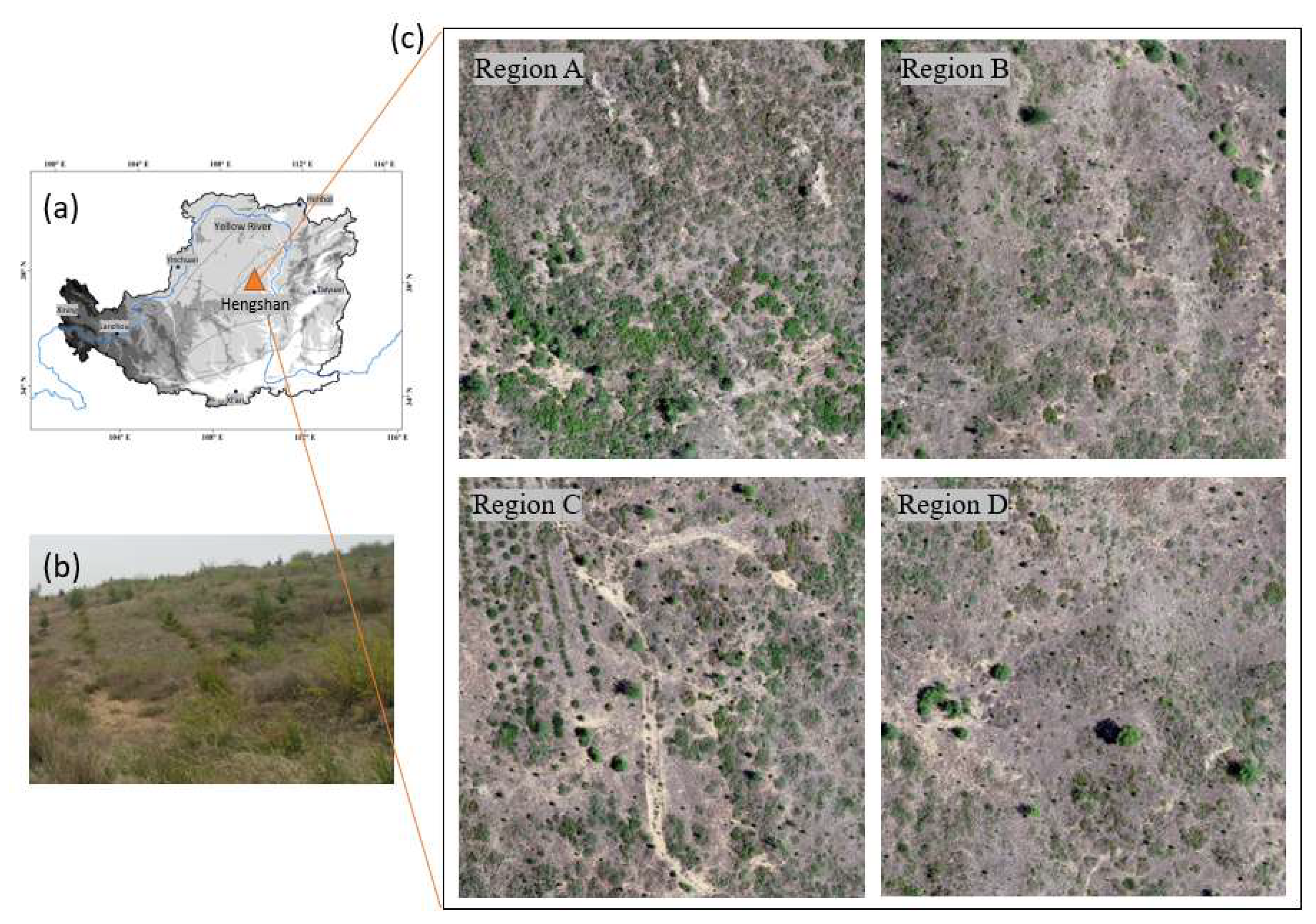

2.1. UAV Aerial Survey Data Acquisition

2.2. Acquisition of Validation Samples and Classification of Ground Objects in Images

2.3. Construction of Semantic Segmentation Label Database

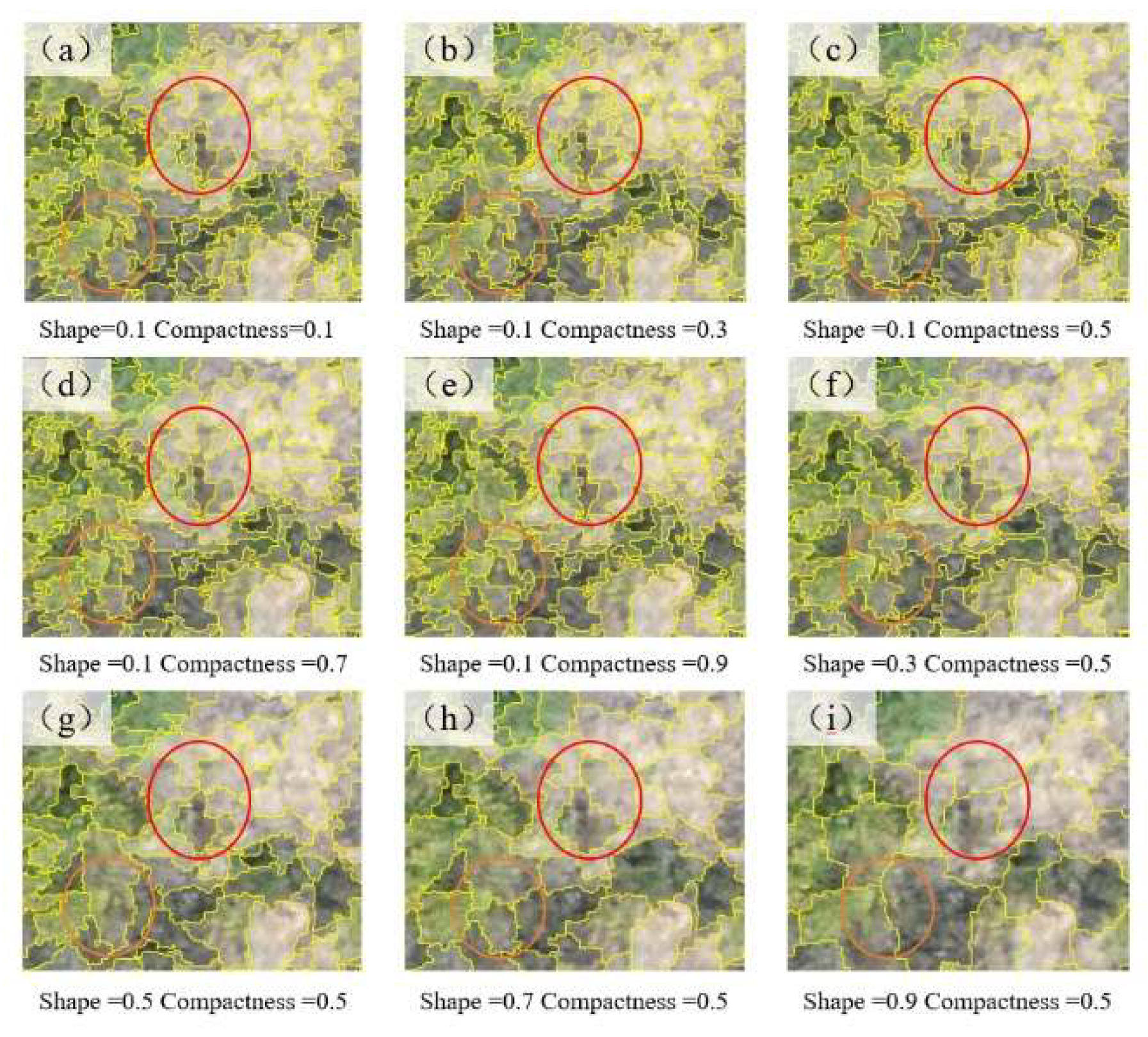

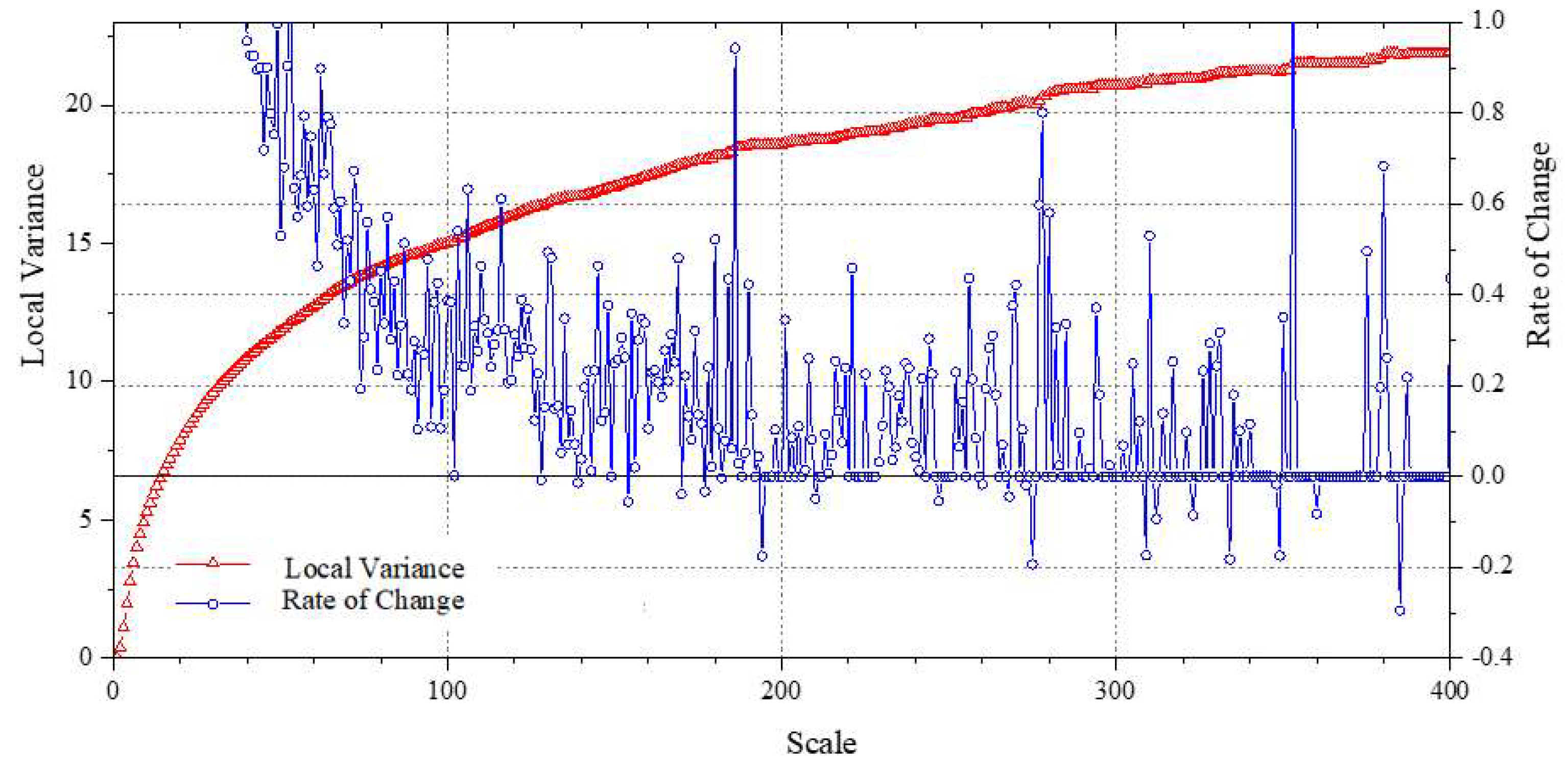

2.3.1. Multiscale Segmentation Parameter Optimisation

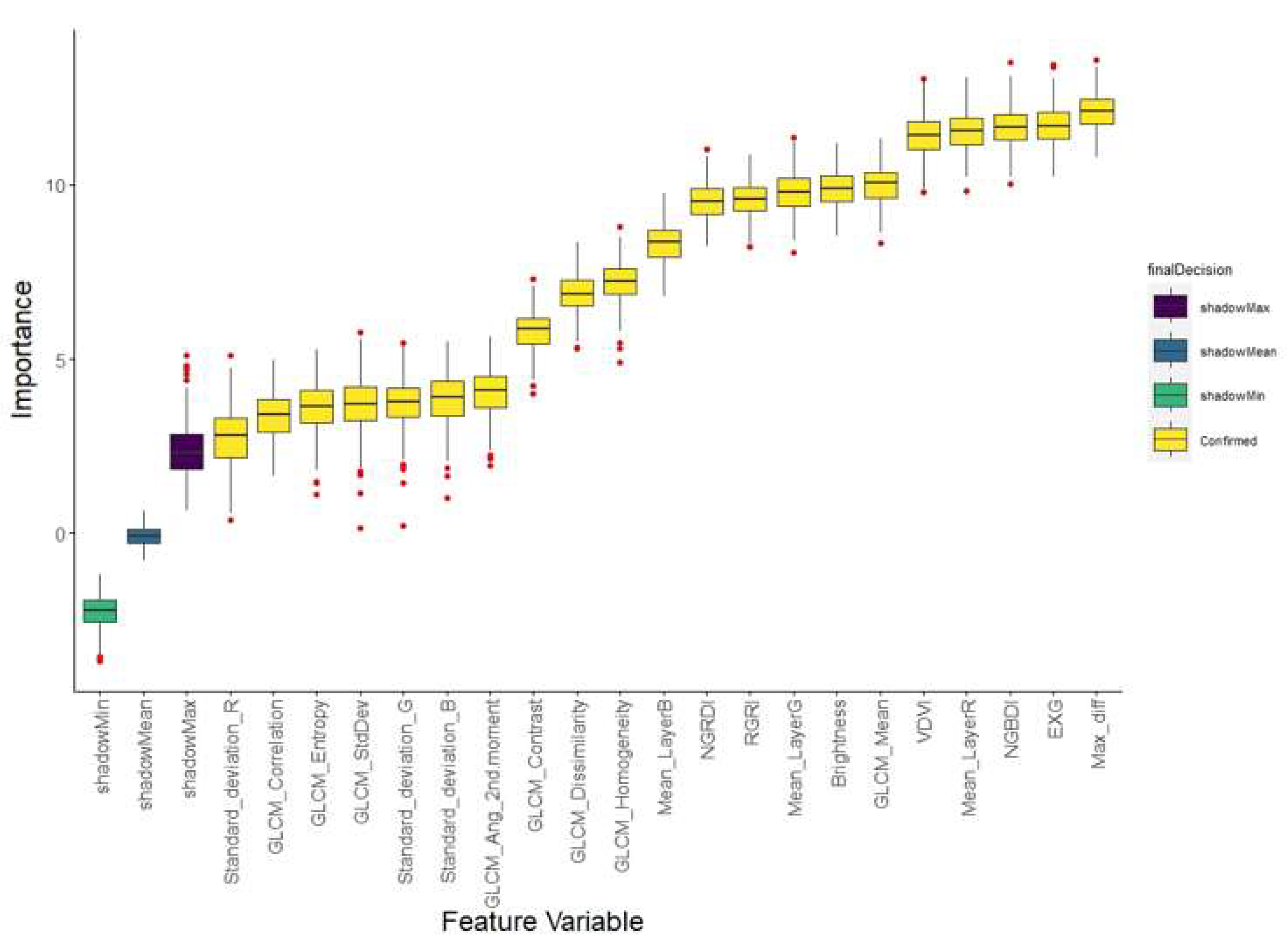

2.3.2. Optimised Feature Indicator Set and Manual Correction

2.4. Methods

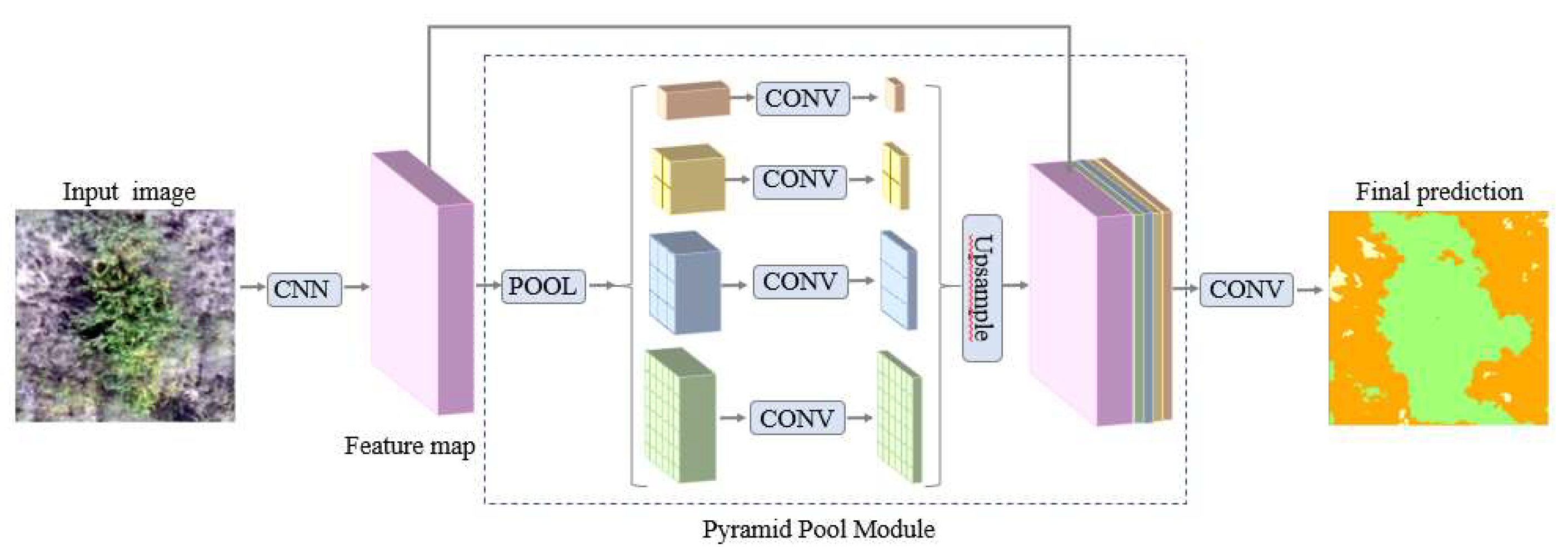

2.4.1. PSPNet

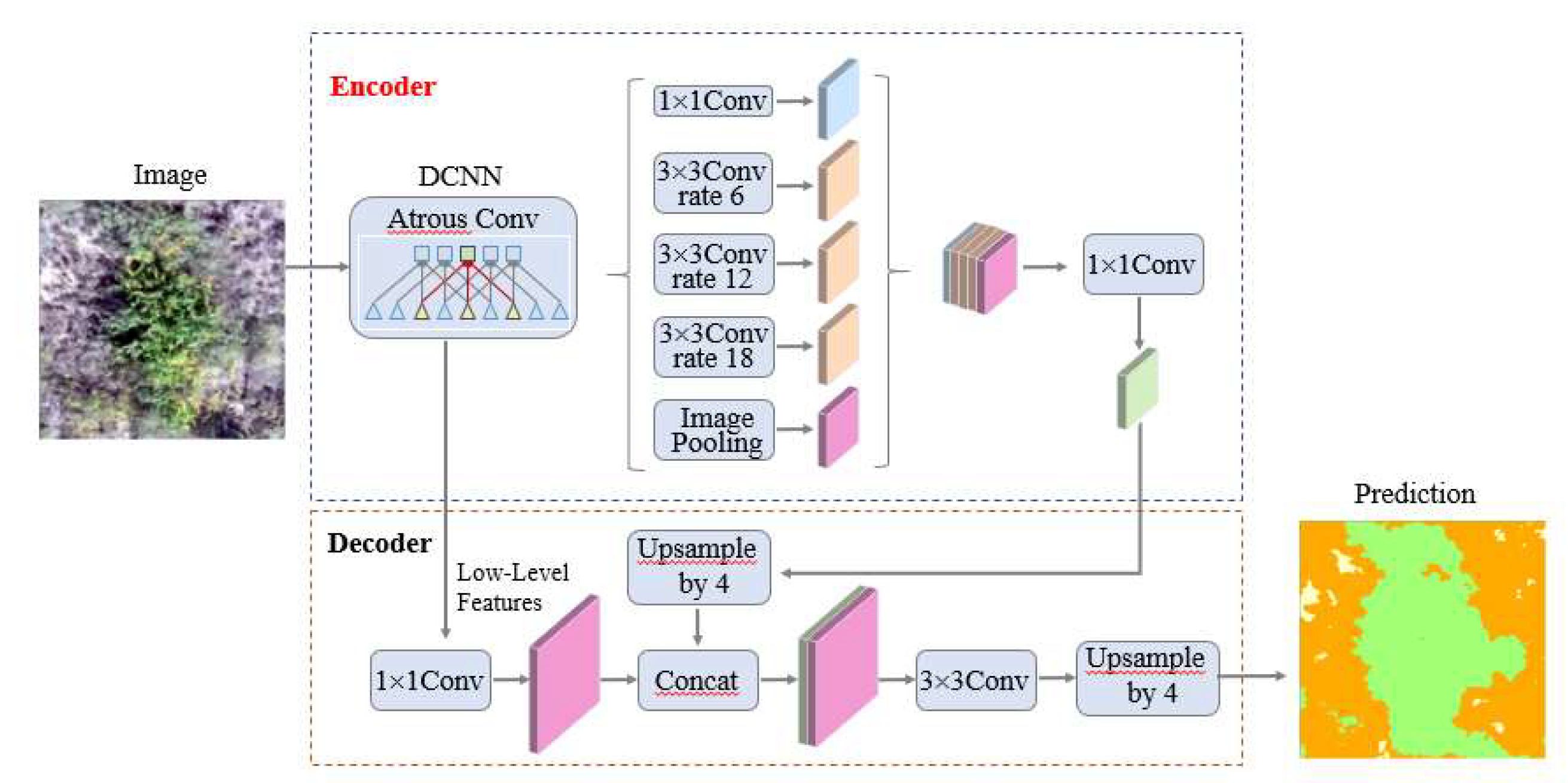

2.4.2. DeepLabV3+

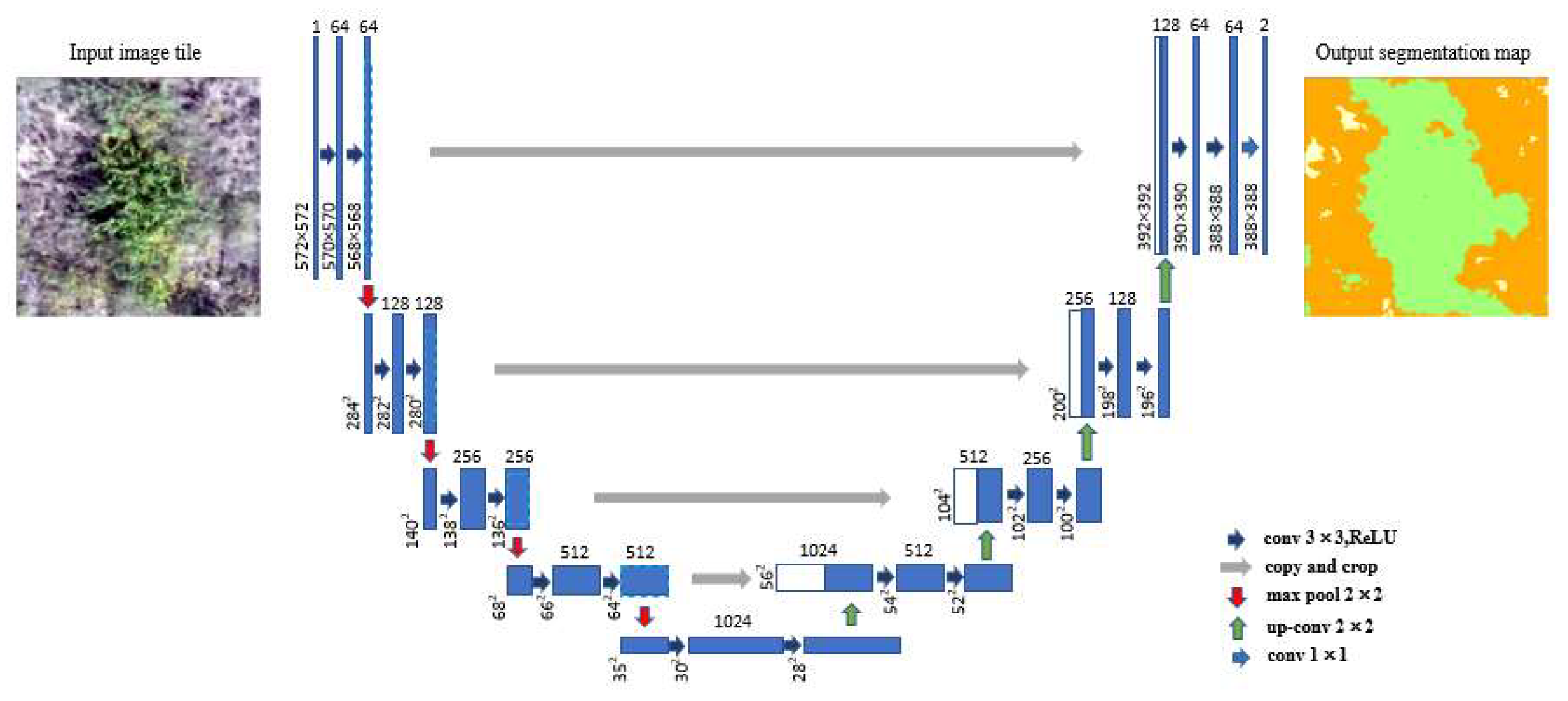

2.4.3. U-Net

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Comparison Between Deep Learning Semantic Segmentation Models for Hengshan Grassland

3.2. Generalisability Evaluation of Semantic Segmentation Models for Hengshan Grassland

3.3. Spatial Distribution of PV and NPV in Hengshan Grassland at Different Times

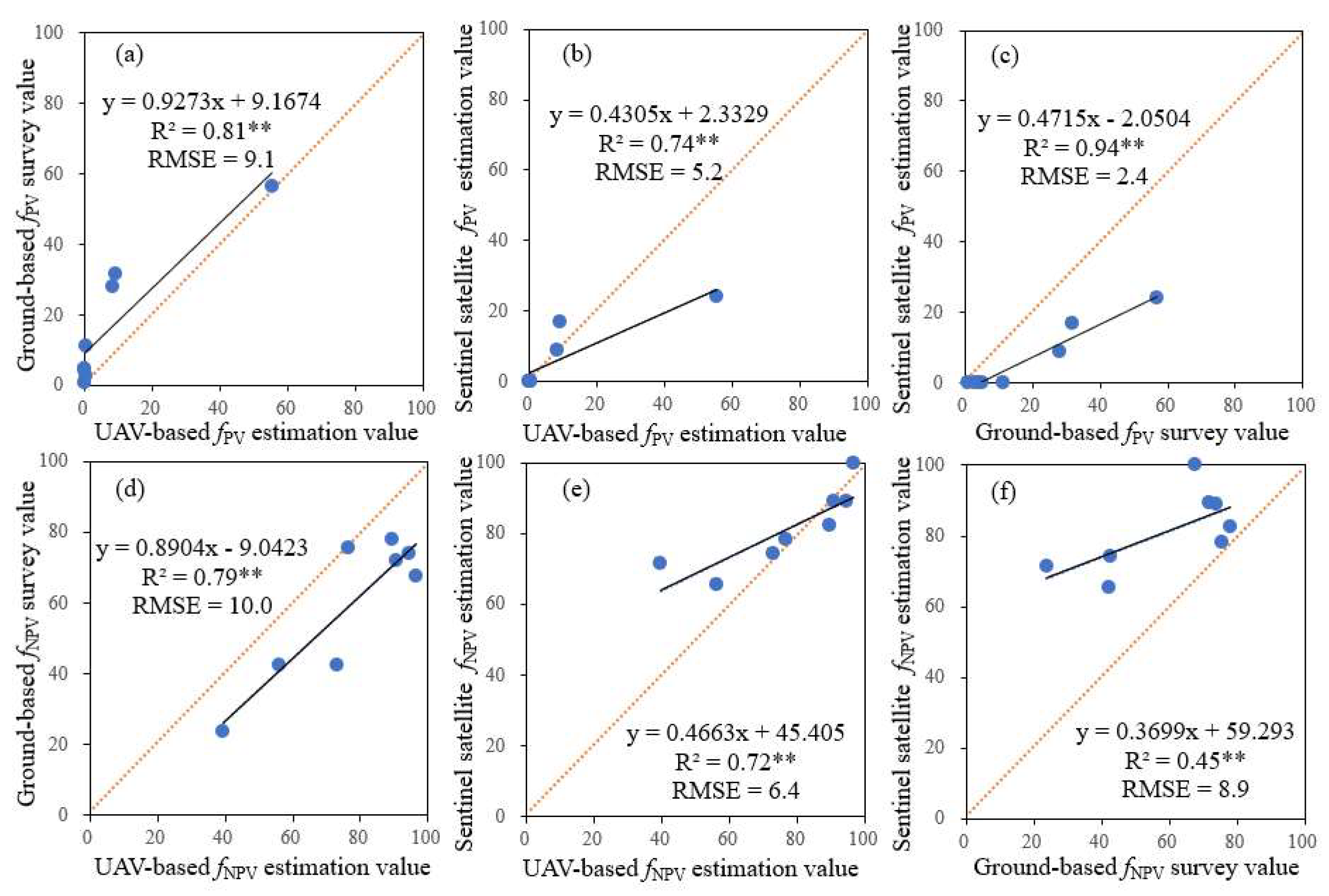

3.4. Correlation Analysis of fPV and fNPV Estimation in Hengshan Grassland Using Three Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Superior Performance of PSPNet in Extracting PV and NPV in Semi-arid Hengshan Grassland

4.2. High Applicability of UAV and Deep Learning-Based Estimation of PV and NPV

4.3. Future Perspectives on Deep Learning Models in Vegetation Classification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, X.; Zhao, W.; Luo, W.; An, N. Effect of climate change on the seasonal variation in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic vegetation coverage in desert areas, Northwest China. Catena. 2024, 239, 107954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.J.; Guerschman, J.P. Global trends in vegetation fractional cover: Hotspots for change in bare soil and non-photosynthetic vegetation. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2022, 324, 107719. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, T.N.; Ripley, D.A. On the relation between NDVI, fractional vegetation cover, and leaf area index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 62, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A.; Pacheco, A.; Staenz, K.; McNairn, H.; Omari, K. Estimating and mapping crop residues cover on agricultural lands using hyperspectral and IKONOS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 104, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Phillips, Z. Examining Spatiotemporal Photosynthetic Vegetation Trends in Djibouti Using Fractional Cover Metrics in the Digital Earth Africa Open Data Cube. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; He, L.; He, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, Q. An experimental study on field spectral measurements to determine appropriate daily time for distinguishing fractional vegetation cover. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Bao, A.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Chang, C.; Chen, T.; Gao, Z. The potential of multispectral vegetation indices feature space for quantitatively estimating the photosynthetic, non-photosynthetic vegetation and bare soil fractions in Northern China. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing. 2019, 85, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ez-zahouani, B.; Teodoro, A.; El Kharki, O.; Jianhua, L.; Kotaridis, I.; Yuan, X.; Ma, L. Remote sensing imagery segmentation in object-based analysis: A review of methods, optimization, and quality evaluation over the past 20 years. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment. 2023, 32, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, G.; Wang, J.; Wu, M.; Li, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Mapping the fractional cover of non-photosynthetic vegetation and its spatiotemporal variations in the Xilingol grassland using MODIS imagery (2000− 2019). Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 1863–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Qin, R.; Chen, X. Unmanned aerial vehicle for remote sensing applications—A review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osco, L.P.; Junior, J.M.; Ramos, A.P.M.; de Castro Jorge, L.A.; Fatholahi, S.N.; de Andrade Silva, J.; Matsubara, E.T.; Pistori, H.; Gonçalves, W.N.; Li, J. A review on deep learning in UAV remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Chang, Y.C.; Liu, L.; Pei, Q. A Low-Cost and Lightweight Real-Time Object-Detection Method Based on UAV Remote Sensing in Transportation Systems. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchra, H.; Belangour, A.; Erraissi, A. A comparative study on pixel-based classification and object-oriented classification of satellite image. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology. 2022, 70, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.Y.; Colkesen, I. A novel hybrid methodology integrating pixel-and object-based techniques for mapping land use and land cover from high-resolution satellite data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 5640–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Guo, J. Fuzzy geospatial objects− based wetland remote sensing image Classification: A case study of Tianjin Binhai New area. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 132, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.I.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Peña, J.M.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; Csillik, O.; López-Granados, F. An automatic random forest-OBIA algorithm for early weed mapping between and within crop rows using UAV imagery. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi Chen, G.; Tao, W.; Shu Lin, L.; Wen Ping, K.; Xiang, C.; Kun, F.; Ying, Z. Comparison of the backpropagation network and the random forest algorithm based on sampling distribution effects consideration for estimating nonphotosynthetic vegetation cover. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 104, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattenborn, T.; Leitloff, J.; Schiefer, F.; Hinz, S. Review on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in vegetation remote sensing. Isprs-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 173, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidaris, S.; Komodakis, N. Object detection via a multi-region and semantic segmentation-aware cnn model. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015, 1134–1142.

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, 2881–2890.

- Fang, H.; Lafarge, F. Pyramid scene parsing network in 3D: Improving semantic segmentation of point clouds with multi-scale contextual information. Isprs-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 154, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, -9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18:Springer, 2015, 234–241. 5 October.

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Dehghan, M.; Zaiane, O.R.; Jagersand, M. U2-Net: Going deeper with nested U-structure for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 106, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. Ieee Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, 801–818.

- Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H.; Hua, W.; Yuille, A.L.; Fei-Fei, L. Auto-deeplab: Hierarchical neural architecture search for semantic image segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, 82-92.

- Li, S.; Zhu, Z.; Deng, W.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Peng, B.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z. Estimation of aboveground biomass of different vegetation types in mangrove forests based on UAV remote sensing. Sustainable Horizons. 2024, 11, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putkiranta, P.; Räsänen, A.; Korpelainen, P.; Erlandsson, R.; Kolari, T.H.; Pang, Y.; Villoslada, M.; Wolff, F.; Kumpula, T.; Virtanen, T. The value of hyperspectral UAV imagery in characterizing tundra vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 308, 114175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo Torres, D.; Queiroz Feitosa, R.; Nigri Happ, P.; Elena Cué La Rosa, L.; Marcato Junior, J.; Martins, J.; Ola Bressan, P.; Gonçalves, W.N.; Liesenberg, V. Applying fully convolutional architectures for semantic segmentation of a single tree species in urban environment on high resolution UAV optical imagery. Sensors. 2020, 20, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Lyu, D.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yi, H.; Tian, Q.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Combining object-oriented and deep learning methods to estimate photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic vegetation cover in the desert from unmanned aerial vehicle images with consideration of shadows. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, H.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, S. Ecosystem Services’ Response to Land Use Intensity: A Case Study of the Hilly and Gully Region in China’s Loess Plateau. Land. 2024, 13, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Gao, X.; Sun, M.; Wang, A.; Sang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Ariyasena, H. Spatial and temporal patterns of drought based on RW-PDSI index on Loess Plateau in the past three decades. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Tsuji, T.; Matsuoka, M. Estimation of rice plant coverage using sentinel-2 based on UAV-observed data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Qi, Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, T.; Tang, B.; Gu, Y. UAV Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Image Classification: A Systematic Review. Ieee, J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens.

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R.; Laake, J.L. Estimation of density from line transect sampling of biological populations. Wildl. Monogr. 1980, 3, 202. [Google Scholar]

- Guerschman, J.P.; Hill, M.J.; Renzullo, L.J.; Barrett, D.J.; Marks, A.S.; Botha, E.J. Estimating fractional cover of photosynthetic vegetation, non-photosynthetic vegetation and bare soil in the Australian tropical savanna region upscaling the EO-1 Hyperion and MODIS sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 928–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Halabuk, A.; Atzberger, C.; Hank, T.; Steinhauser, S.; Berger, K. A comprehensive survey on quantifying non-photosynthetic vegetation cover and biomass from imaging spectroscopy. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhou, B. Mangrove Species Classification from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Hyperspectral Images Using Object-Oriented Methods Based on Feature Combination and Optimization. Sensors. 2024, 24, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drǎguţ, L.; Tiede, D.; Levick, S.R. ESP: a tool to estimate scale parameter for multiresolution image segmentation of remotely sensed data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G. A review of assessing the accuracy of classifications of remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 37, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegun, A.A.; Viriri, S.; Tapamo, J. Review of deep learning methods for remote sensing satellite images classification: experimental survey and comparative analysis. J. Big Data. 2023, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Mahadevan, S. An improved method to construct basic probability assignment based on the confusion matrix for classification problem. Inf. Sci. 2016, 340, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, G.M. Explaining the unsuitability of the kappa coefficient in the assessment and comparison of the accuracy of thematic maps obtained by image classification. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 239, 111630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasingha, D.S.K. Root mean square error or mean absolute error? Use their ratio as well. Inf. Sci. 2022, 585, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, J.; Kang, L.; Zhu, Q. Evaluation of Global-Scale and Local-Scale Optimized Segmentation Algorithms in GEOBIA with SAM on Land Use and Land Cover. Ieee J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Type | Region A | Region B | Region C | Region D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | UA | PA | UA | PA | UA | PA | UA | ||

| September | PV | 92.5 | 94.9 | 90.5 | 76.0 | 91.5 | 87.8 | 86.9 | 98.1 |

| NPV | 90.4 | 86.8 | 93.8 | 97.2 | 91.1 | 91.9 | 94.9 | 89.6 | |

| BS | 85.7 | 85.7 | 70.0 | 77.8 | 88.2 | 93.8 | 76.2 | 76.2 | |

| OA(%) | 91.5 | 91.0 | 90.5 | 90.5 | |||||

| Kappa | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.82 | |||||

| July | PV | 86.7 | 92.9 | 88.2 | 78.9 | 91.5 | 87.8 | 86.3 | 93.2 |

| NPV | 89.4 | 89.4 | 94.2 | 95.4 | 91.8 | 91.8 | 94.3 | 83.9 | |

| BS | 83.3 | 58.8 | 75.0 | 90.0 | 84.2 | 98.0 | 66.7 | 87.5 | |

| OA(%) | 88.0 | 92.0 | 91.0 | 87.5 | |||||

| Kappa | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.77 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).