1. Introduction

Falls are common problems among post-stroke patients, and fall injuries pose a risk for reduced quality of life in post-stroke patients [

1]

. Post-stroke patients experience falls more frequently than healthy older adults, particularly during walking [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, fall prevention is an important rehabilitation goal for post-stroke patients. Frequent falls in post-stroke patients are attributed to reduced body functions, including motor function, sensory function, and balance ability [

4]. Motor and sensory paresis and impaired trunk function, in post-stroke patients are related with balance disorders during walking [

5,

6,

7].

Turning, as well as straight line walking is an important component of everyday mobility [

8]. Compared to straight line walking in healthy adults, turning requires a greater range of hip external/internal rotation of the inner leg and increased foot pressure (i.e., weight bearing) on the inner leg [

9]. Additionally, in healthy adults, the propulsive force generated by the outer leg leads to an increase in angular momentum in the transverse plane around the inner leg, which requires more complex control during turning compared to walking [

10]. In fact, the rate of fall accidents was higher for turning than for straight walking [

11]. Given the task complexity of turning and the high rate of falls during turning, it is necessary to clarify the characteristics of turning movements in post-stroke patients and to develop fall prevention strategies that address the specific challenges of turning movement disorder. However, many studies on the post-stroke patients have focused on straight walking, with fewer reports on turning movements [

12].

Difference during turning movements have been identified between post-stroke patients and healthy adults. Studies have reported that post-stroke patients take longer to complete turning movements compared to healthy adults [

12,

13]. Additionally, post-stroke patients exhibit reduced trunk angular velocity about the vertical axis and trunk acceleration in the antero-posterior direction compared to healthy adults, indicating a decrease in trunk movement speed during turning in post-stroke patients [

13]. In other words, post-stroke patients might employ a more cautious strategy by slowing down their turning movements compared to healthy controls[

14]. On the other hand, some studies have suggested that walking slowly is an inadequate strategy for reducing gait instability [

15,

16]. In these previous studies focusing on straight walking, post-stroke patients with poor clinical balance scores showed greater lateral sway than those with good scores, despite their slower gait speeds [

15,

16]. Therefore, post-stroke patients with poor clinical balance scores may exhibit greater lateral sway even with slower turning speed, potentially contributing to falls during turning movements. However, to our knowledge, it has been unclear in which direction post-stroke patients at high risk for falls (i.e., poor balance ability) are unstable during turning movements.

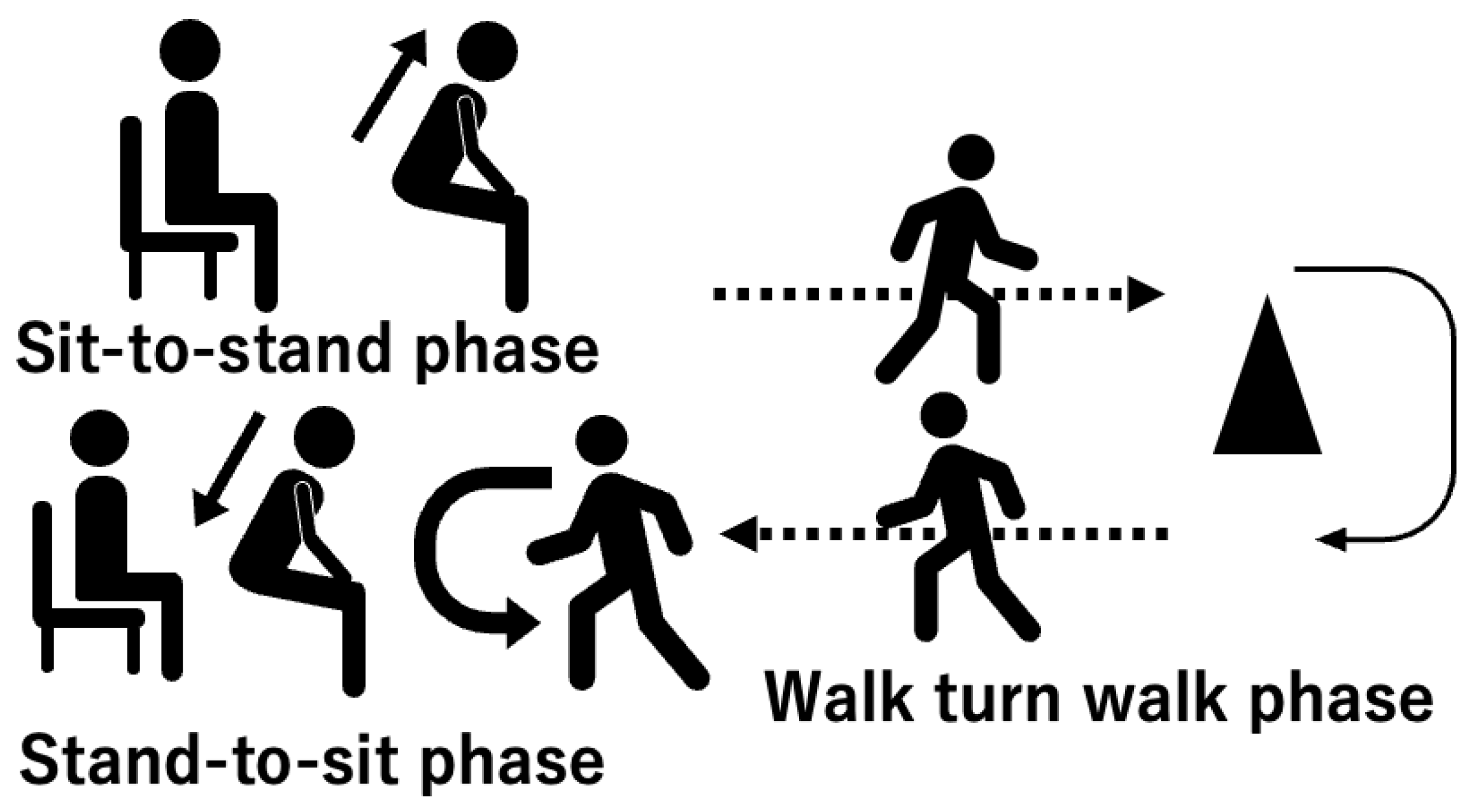

The aim of this study was to determine the differences in gait instability during turning movements between post-stroke patients at high and low risk of falling. In this study, we analyzed the characteristics of turning movements in the Timed up and go test (TUG) (Figure 1). We hypothesized that 1) post-stroke patients with a high-risk of falling exhibit smaller angular velocities about the vertical axis during turning movement than those with a low-risk of falling, and 2) post-stroke patients with high-risk falling exhibit greater disturbance in the mediolateral direction during turning movement than those with low-risk falling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

For the participants, 31 post-stroke patients (19 males, age range 40-89 years) were admitted to our convalescent rehabilitation ward and 10 age-matched controls (6 males, age range 40-80 years). The inclusion criteria for post-stroke group were as follows: 1) hemorrhage or infarction in the supratentorial region on unilateral side by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and diagnosis of cerebral hemorrhage or infraction, 2) patients who had received medical treatment after stroke onset, 3) patients aged 20 years old or older, and 4) patients who were able to perform TUG with cane and orthosis and without assistance. The inclusion criteria for age-matched controls also included 3) and 4). Exclusion criteria for post-stroke group and controls ware: 1) existing neurological (post-stroke group excludes cerebrovascular disorders treated in this trial), motor, circulatory, or respiratory diseases that interfere with the performance in the study, and 2) existing higher brain dysfunction, cognitive impairment, or aphasia that interfere with the performance in the study. Participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Clinical Assessment

Post-stroke patients were administered the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) as a balance ability assessment. Post-stroke patients with a BBS score below 45 were assigned to the high-risk group for falling (high-risk group), and BBS score of 45 or above were assigned to the low-risk group for falling (low-risk group) [

17]. After allocation to the groups, post-stroke patients underwent Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Lower extremity (FMA-L) [

18], Stroke Impairment Assessment Set (SIAS) scores for lower extremity motor function (hip flexion test, knee extension test, and foot tap test) [

19], and Trunk Impairment Scale (TIS) [

20].

2.3. Turning Movement Task

Turning movement was assessed using the instrumented TUG (iTUG)[

13] (

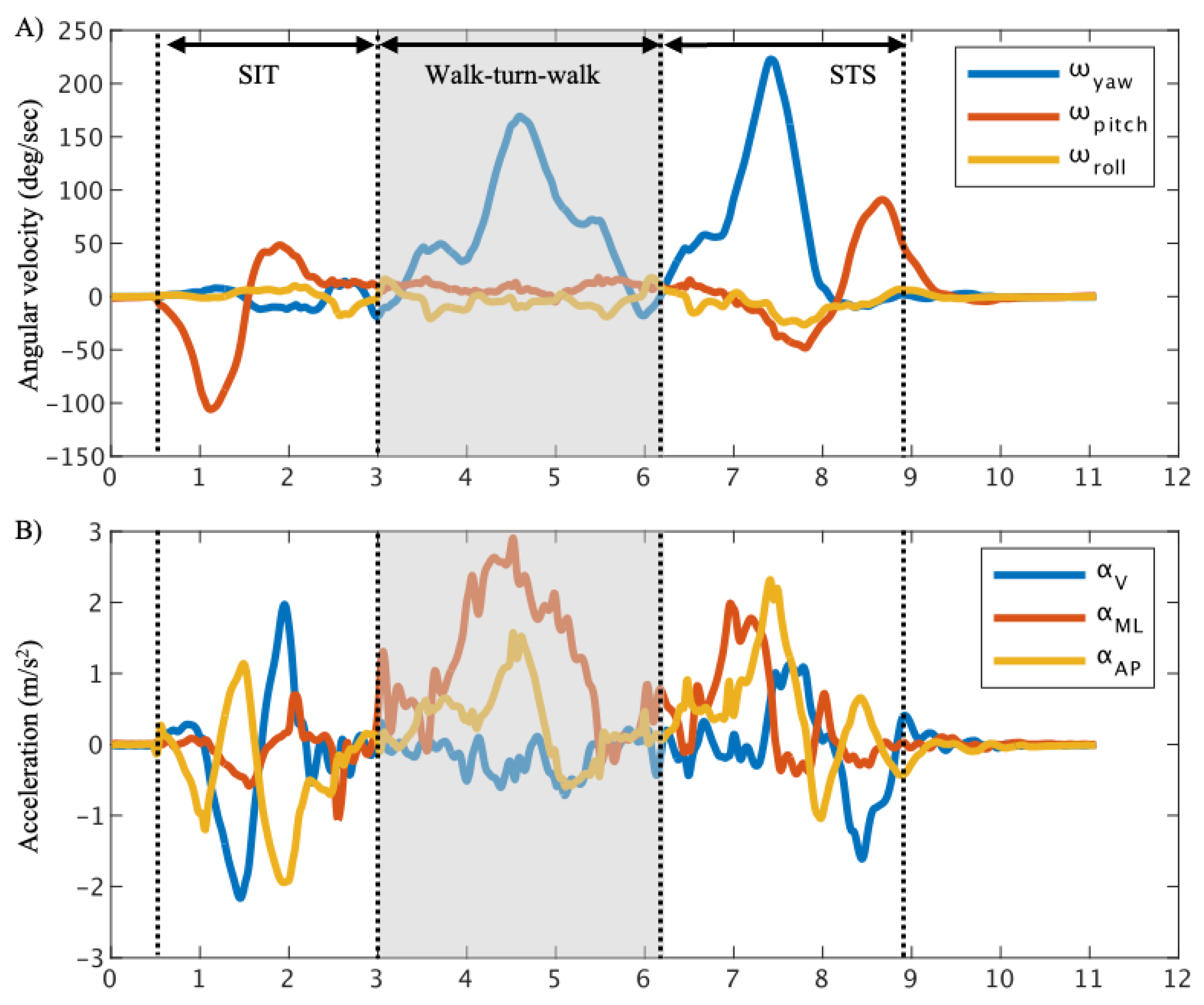

Figure 1), which uses an IMU to measure trunk movement in the TUG (Figure 2). The iOS application SENIOR Quality (Digital Standard inc., Osaka, Japan) [

21] , and the iPhone 12 mini (Apple inc., California, USA) served as the inertial measurement unit (IMU). The iPhone12 mini was placed in a pouch and positioned above the navel. SENIOR Quality recorded the following data: angular velocity about the vertical-axis (ω

yaw), medio-lateral-axis (ω

pitch), and antero-posterior-axis (ω

roll), and acceleration in the antero-posterior direction (α

AP), the vertical direction (α

V), and the medio-lateral direction (α

ML). Positive values of ω

yaw, ω

pitch, and ω

roll were indicated turning velocity toward the affected side, trunk extension velocity, lateral flexion velocity toward the unaffected side in the post-stroke patients’ group, and turning velocity toward the left side, trunk extension velocity, lateral flexion velocity to the right side in the control group. Positive value of α

V, α

ML, and α

AP were indicated the upward acceleration, the lateral acceleration toward the unaffected side, and the forward acceleration in the post-stroke patient group, and upward acceleration, lateral acceleration toward the right side, and the forward acceleration in the control group. The data were recorded at a sampling rate of 100 Hz.

In the iTUG, the subjects were instructed to perform the TUG at comfortable speed. The subjects equipped with the IMU sat in the chairs (height 0.43 m) and prepared for the TUG start cue. At start signal, subjects stood up and walked 3 meters, turned around a cone, returned to the chair and sat down. Post-stroke patients were instructed turn toward to the affected side, and control group was instructed to turn toward the left side. Subjects performed the iTUG three times and were allowed to use their usual cane and orthosis, as used in their daily lives when performing the TUG.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data were smoothed using a 50 Hz moving average filter. The smoothed data were divided into the sit-to-stand phase (SIT), the walk-turn-walk phase, the stand-to-sit phase (STS)[

22] (

Figure 2). The start of the SIT was determined by ω

pitch below

10 deg/s, and the end of the SIT was determined by ω

pitch below 10 deg/s [

23]. The start of the STS was determined by ω

yaw above 10 deg/s, and the end of the STS by the max value of α

V immediately after the peak value of ω

pitch [

24]. The walk-turn-walk phase was defined as the period from the start of the STS to end of the SIT [

25].

The maximum, minimum, and root mean square (RMS) values of the acceleration and angular velocity were calculated for each phase. Data analysis was performed using MATLAB R2021b (MathWorks, Massachusetts, USA).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Sex, diagnosis, paretic side, use of the cane and orthosis, and SIAS were compared between the high-risk group and the low-risk group using the Chi-square test. Time post-stroke, BBS, FMA-L, and TIS scores were compared between the high-risk and the low-risk group using the Willcoxon rank sum test. Age, height, weight, the trunk angular velocity and acceleration parameters, and the duration in the walk-turn-walk phase were compared among the high-risk group, low-risk group, and controls using the Kruskal-Wallis tests, followed by Steel-Dwass multiple comparison procedures. The effect size and statistical power were calculated for each value. The effect size (

) was defined as large ≥ 0.14, medium ≥ 0.06, small ≥ 0.01[

26]. Sufficient statistical power (1 – β) was defined as ≥ 0.80

26.

The spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze the association between the trunk IMU data showing significant differences between the high-risk and low-risk groups and the SIAS lower extremity score. The correlation coefficients were classified as weak (0.10 ≤ r ≤ 0.39), moderate (0.40 ≤ r ≤ 0.69), strong (0.70 < r ≤ 0.89), very strong (0.90 ≤ r) [

27]. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 16 (SAS Institute Inc. North Carolina, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data and Clinical Characteristics

Post-stroke patients were assigned to 13 in the high-risk group and 18 in the low-risk group in this study (

Table 1). There were no significant differences in basic demographic data, but clinical characteristics were significantly different between the high-risk group and the low-risk group (

Table 1). The motor function of the lower limb was significantly lower in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group (FMA-L: p = 0.006, SIAS hip flexion test: p < 0.001, knee extension test: p = 0.006, foot tap test: p = 0.04,

Table 1).

3.2. Trunk Angular Velocity and Acceleration in Walk-Turn-Walk Phase

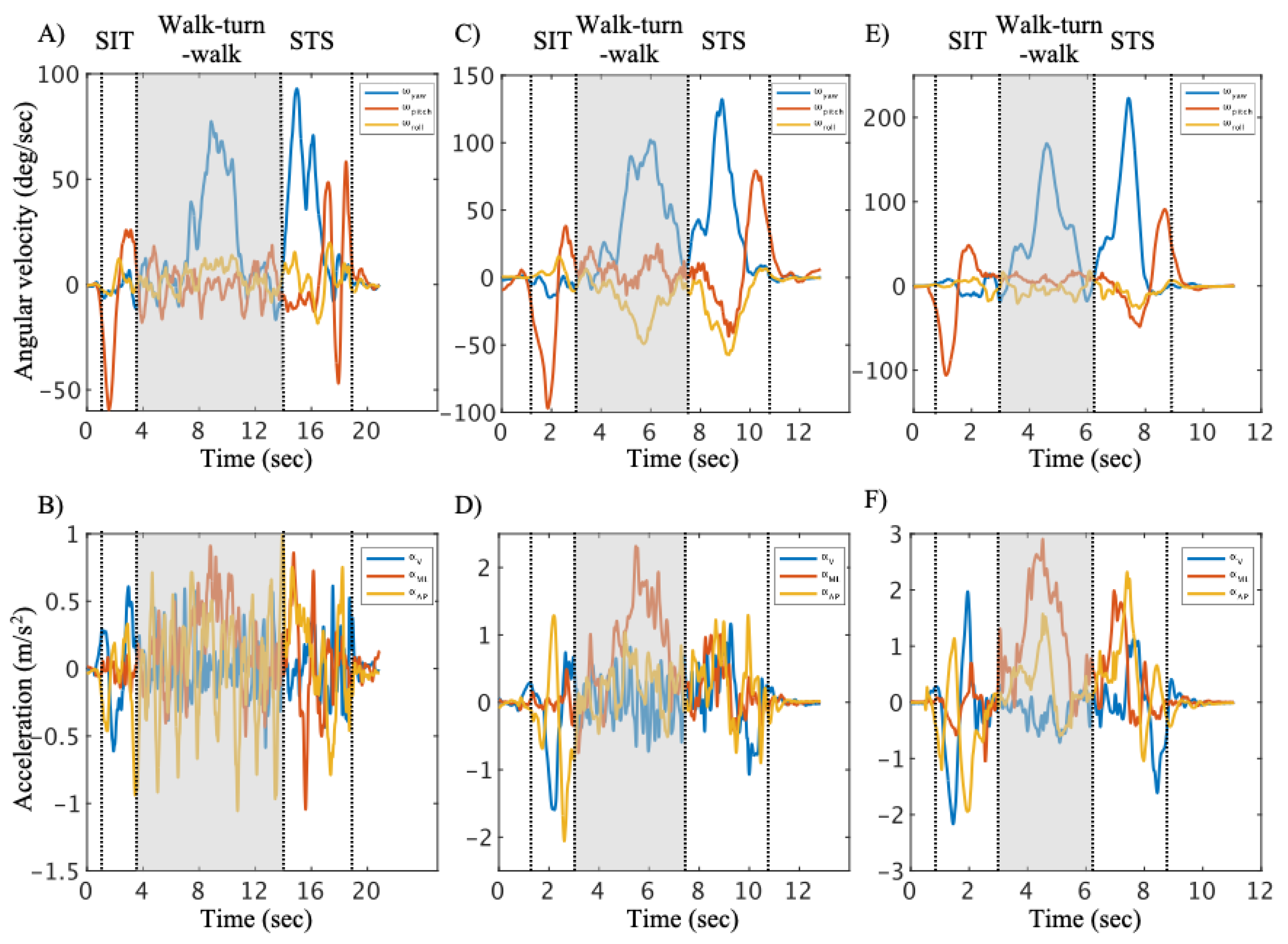

The representative time series data in the walk-turn-walk phase are shown for the high-risk group, low-risk group and controls (

Figure 3). The duration in the walk-turn-walk phase (χ

2 = 31.21, p < 0.001,

) was significantly longer in the high-risk group than that in other groups (

Table 2). The maximum of ω

yaw (χ

2 = 28.51, p < 0.001,

) in the high-risk group was significantly lower than that in other groups (

Table 2). The minimum of ω

pitch (χ

2 = 9.80, p = 0.007,

) in the high-risk group was significantly lower than that in other groups (

Table 2). The RMS of ω

yaw (χ2 = 32.78, p < 0.001,

), α

V (χ

2 = 21.17, p < 0.001,

), α

ML (χ

2 = 21.19, p < 0.001,

) and α

AP (χ

2 = 28.28, p < 0.001,

) in the high-risk group were significantly lower than that in other groups (

Table 2). The comparisons of trunk angular velocity and acceleration in the SIT and STS phase are shown in

Appendix A Table A1 and A2.

3.3. The Relationship Between SIAS Score and Trunk Angular Velocity and Acceleration

The relationships between SIAS score for lower extremity motor function and trunk movement during turning in post-stroke patients are shown in

Table 3. The maximum ω

yaw (r = 0.591, p < 0.001) and the maximum α

AP (r = 0.416, p = 0.020) in post-stroke patients were moderately correlated with hip flexion. The minimum ω

pitch (r = 0.520, p = 0.003) in post-stroke patients was moderately correlated with hip flexion. The RMS of ω

yaw (r = 0.730, p < 0.001) in post-stroke patients was strongly correlated with hip flexion.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the differences in trunk movement during turning in post-stroke patients with high- and low-risk of falling and controls. We found decreased trunk rotation speed and trunk acceleration in the mediolateral direction at the high-risk group, which partially supported our hypothesis. On the other hand, increased trunk flexion velocity during turning in the post-stroke patients with a high-risk of falling did not support our hypothesis about angular velocity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to revel the characteristics of turning movement during turning in post-stroke patients with a high-risk falling.

The high-risk group showed a decrease in the trunk rotation speed and trunk acceleration of mediolateral direction during turning (

Table 2). The previous studies have reported that post-stroke patients have poor balance ability compared to healthy subjects, resulting in longer turning movement time of the TUG [

14,

28,

29]. Our result indicated similar trend with these previous studies. Furthermore, the high-risk group exhibited the lowest trunk rotation speed and acceleration of mediolateral direction compared to the other groups (

Table 2). These results indicate that both trunk rotation speed and mediolateral acceleration are reduced in high-risk group. Previous studies have shown that trunk rotation speed was associated with balance ability in post-stroke patients [

28]. This suggests that a reduction in trunk rotation speed may compensates for poor balance ability in the high-risk group. On the other hand, there were no significant differences in the maximum and minimum ω

roll values between the high-risk and low-risk groups. In other words, trunk lateral flexion showed a similar trend between the two groups. This suggests that trunk rotation speed might be reduced to maintain stability in the mediolateral direction. An increase in the trunk rotation speed is associated with an increase in centrifugal force, which causes the body to fall outward [

30]. Therefore, the high-risk group likely reduces the trunk rotation speed to compensate for stability in the mediolateral direction. Thus, decreased movement speed and mediolateral instability during turning are associated with poor balance ability. These results suggest that a decrease in trunk rotation speed in the high-risk group to compensates for mediolateral stability during turning, thereby supports our hypothesis.

In contrast, the minimum of ω

pitch in the high-risk group was smaller than that in other groups (

Table 3). In other words, the high-risk group exhibited greater trunk disturbance in the trunk flexion direction compared to other groups, despite compensating for stability by decreasing trunk rotation speed during turning. A previous study reported that an increase in whole-body angular momentum in the sagittal plane was associated with a decrease in straight-line walking speed in post-stroke patients [

31]. Our results showed a decrease trunk rotation speed and an increase trunk disturbance in the sagittal plane during turning in the high-risk group, which was a similar trend to previous study. Trunk disturbances in the sagittal plane during walking are primarily compensated for by the hip joint, which maintains trunk stability [

32,

33]. The high-risk group exhibited more severe motor palsy, particularly in the hip joint, compared to the low-risk group (

Table 1). Moreover, the relationship between hip flexion and trunk disturbance in the direction of trunk flexion suggests an association between lower extremity motor function and trunk disturbance (

Table 3). These results suggest that the high-risk group lacks sufficient dynamic postural control through the hip joint during turning, thereby increasing trunk disturbance in the sagittal plane. Importantly, the high-risk group exhibits trunk disturbance in the sagittal plane during turning, even with a decreased movement speed intended to compensate for poor balance ability. This characteristic, contrary to our hypothesis, represents a new finding in our study. These findings suggest that the characteristics of turning movements in post-stroke patients depend on their balance ability, particularly the susceptibility of trunk flexion direction disturbance to balance ability.

This study has several limitations. First, participants with cognitive impairment were excluded. Given the known relationship between cognitive impairment and balance ability, including such participants could potentially yield different results[

34]. Second, the use of canes and orthoses was not restricted. Canes can assist in stabilizing posture during movement [

35,

36]. Third, this study divided the TUG into three subcomponents: the STS, walk-turn-walk, SIT. Walking phase and turning phase divided, Further division of the walking and turning phases could allow for a more detailed analysis of trunk movement during turning. Fourth, this study was conducted using a comfortable speed in the TUG. While maximum movement speed is associated with balance ability, other studies have reported that individuals with good balance ability exhibit less associated movement speed [

37]. Therefore, this study was employed a comfortable speed in TUG. Fifth, this study had a small sample size. Therefore, effect size and statistical power were assessed, and the main results showed adequate statistical power. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as they do not include post-stroke patients with cognitive impairment and are limited to those who can undergo the TUG assessment, which may restrict their generalizability to all post-stroke patients.

5. Conclusions

This study clarified the characteristics of trunk movement during turning in post-stroke patients based on differences in balance ability. The trunk rotation speed and mediolateral acceleration were lowest in post-stroke patients with high-risk of falling compared to other groups and were correlated with balance ability in post-stroke patients. On the other hand, the post-stroke patients with a high-risk of falling exhibited greater trunk disturbance in the sagittal plane during turning compared to other groups. Furthermore, trunk disturbance in the sagittal plane during turning was correlated with hip joint function. These findings indicate that trunk disturbance in the sagittal plane during turning is characteristic of poor balance ability in post-stroke patients. This may suggest the need for a trunk control strategy focusing on the hip joint of the affected side during turning to enhance trunk stability alongside physical function.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, I.S. and S.E.; methodology, D.N., K.H., Y.S., S.I., and S.E.; software, D.N., K.H., and Y.S.; validation, D.N., K.H., and Y.S.; formal analysis, D.N., K.H., and Y.S.; investigation, D.N., K.H., and Y.S.; resources, D.N., K.H., Y.S., S.I., and S.E.; data curation, D.N., K.H., and Y.S, writing—original draft preparation, D.N., K.H., and Y.S., writing—review and editing, D.N., K.H., Y.S., S.I., and S.E.; supervision, S.E; project administration, S.E; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol for this study was approved in advance by the Ethics Committee Tohoku university graduate school of medicine (approval number: 2022-1-089).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data, including graphs, within this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study did not receive any financial support. We would like to thank member of rehabilitation department for assisting with data collection in Southern TOHOKU second hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparison of Sit-to-Stand movement using IMU data between post-stroke patients and controls.

Table A1.

Comparison of Sit-to-Stand movement using IMU data between post-stroke patients and controls.

| |

High-risk group |

Low-risk group |

Control |

) |

Power (1–β) |

| Time (sec) |

2.43 (0.52)ac

|

1.99 (0.24)a

|

1.90 (0.36)c

|

0.18 |

0.65 |

| Maximum |

|

|

|

|

|

| ω yaw

|

10.38 (6.70)b

|

11.56 (6.52)c

|

33.73 (22.63)bc

|

0.20 |

0.66 |

| ωpitch

|

31.44 (11.97)b

|

38.17 (9.79)c

|

51.82 (10.98)bc

|

0.31 |

0.95 |

| ωroll

|

11.63 (4.53) |

10.82 (5.29) |

16.00 (5.14) |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| αV

|

1.93 (0.57)ab

|

3.27 (1.26)ac

|

7.09 (3.62)bc |

0.60- |

0.86 |

| αML

|

1.39 (0.64)ab

|

2.31 (1.12)ac

|

4.97 (2.31)bc

|

0.44 |

0.91 |

| αAP

|

1.68 (0.81)ab

|

4.03 (2.23)ac

|

10.78 (7.19)bc

|

0.62 |

0.76 |

| Minimum |

|

|

|

|

|

| ω yaw

|

–15.12 (4.66)b

|

–15.60 (6.99)c

|

–27.28 (13.56)bc

|

0.19 |

0.53 |

| ωpitch

|

–66.00 (15.59)a

|

–88.39 (12.18)ac

|

–100.72 (21.05)c

|

0.40 |

0.95 |

| ωroll

|

–7.50 (1.75)b

|

–7.86 (3.87) |

–13.91 (7.57)b

|

0.18 |

0.48 |

| αV

|

–2.37 (1.41)ab

|

–3.66 (1.40)ac

|

–7.75 (4.51)bc

|

0.45 |

0.71 |

| αML

|

–1.40 (0.59)b

|

–1.71 (0.90)c

|

–4.32 (2.16)bc

|

0.40 |

0.86 |

| αAP

|

–1.43 (0.50)ab

|

–2.58 (0.93)ac

|

–6.69 (5.95)bc

|

0.65 |

0.45 |

| RMS |

|

|

|

|

|

| ω yaw

|

8.15 (2.29)b

|

7.95 (2.43) |

14.48 (6.32)bc

|

0.23 |

0.67 |

| ωpitch

|

34.58 (8.00)ab

|

45.43 (5.17)a

|

52.16 (10.22)b

|

0.45 |

0.96 |

| ωroll

|

6.20 (2.17) |

6.26 (2.92) |

9.16 (3.17) |

|

|

| αV

|

0.78 (0.27)ab

|

1.41 (0.49)ac

|

2.76 (1.08)bc

|

0.68 |

0.97 |

| αML

|

0.48 (0.20)b

|

0.69 (0.32)c

|

1.45 (0.62)bc

|

0.46 |

0.93 |

| αAP

|

0.58 (0.18)ab

|

1.20 (0.51)ac

|

2.63 (1.12)bc

|

0.68 |

0.97 |

Table A2.

Comparison of Stand-to-sit movement using IMU data between post-stroke patients and controls.

Table A2.

Comparison of Stand-to-sit movement using IMU data between post-stroke patients and controls.

| |

High-risk group |

Low-risk group |

Control |

|

Power (1–β) |

| Time (sec) |

4.56 (0.91)ac

|

3.38 (0.61)ab

|

2.13 (0.55)bc

|

0.66 |

0.99 |

| Maximum |

|

|

|

|

|

| ω yaw

|

73.49 (17.39)ab

|

110.08 (28.08)ac

|

193.60 (25.78)bc

|

0.71 |

1.00 |

| ωpitch

|

59.28 (10.95)ab

|

73.08 (14.86)ac

|

87.84 (15.63)bc

|

0.36 |

0.97 |

| ωroll

|

11.82 (7.55) |

10.29 (6.61) |

10.35 (15.10) |

|

|

| αV

|

3.76 (1.43) |

3.79 (1.29)c

|

5.17 (1.81)c

|

0.12 |

0.43 |

| αML

|

3.53 (1.26)b

|

4.15 (1.37) |

5.88 (2.00)b

|

0.18 |

0.69 |

| αAP

|

4.73 (2.49) |

6.20 (1.79) |

7.66 (3.41) |

|

|

| Minimum |

|

|

|

|

|

| ω yaw

|

–4.26 (6.51) |

–9.02 (12.42) |

–8.13 (7.21) |

|

|

| ωpitch

|

–28.02 (9.77)b

|

–36.60 (9.91) |

–49.06 (11.86)b

|

0.35 |

0.96 |

| ωroll

|

–23.12 (10.63) |

–30.46 (14.02) |

–48.09 (33.85) |

|

|

| αV

|

–7.07 (4.06) |

–6.10 (2.68) |

–6.91 (2.54) |

|

|

| αML

|

–3.08 (1.21) |

–3.12 (0.78) |

–3.97 (1.29) |

|

|

| αAP

|

–4.24 (2.21) |

–3.56 (1.20) |

–3.33 (0.82) |

|

|

| RMS |

|

|

|

|

|

| ω yaw

|

37.97 (11.34)ab

|

54.14 (12.41)ac

|

98.65 (16.03)bc

|

0.63 |

1.00 |

| ωpitch

|

22.78 (4.33)ab

|

31.52 (6.60)ac

|

44.95 (9.56)bc

|

0.60 |

1.00 |

| ωroll

|

11.33 (5.41)b

|

17.00 (7.77) |

28.15 (17.29)b

|

0.17 |

0.51 |

| αV

|

1.27 (0.56)b

|

1.42 (0.44)c

|

2.24 (0.68)bc

|

0.28 |

0.89 |

| αML

|

1.03 (0.38)b

|

1.20 (0.28)c

|

1.69 (0.47)bc

|

0.29 |

0.84 |

| αAP

|

1.00 (0.33)ab

|

1.35 (0.38)ac

|

1.96 (0.62)bc

|

0.39 |

0.90 |

References

- Abey-Nesbit R, Schluter PJ, Wilkinson TJ, et al. Risk factors for injuries in New Zealand older adults with complex needs: a national population retrospective study. BMC Geriatr, 2021; 21. [CrossRef]

- Willig, R.; Luukinen, H.; Jalovaara, P. Factors related to occurrence of hip fracture during a fall on the hip. Public Health. 2003, 117, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, J.J.; Burke, J.F.; Clarke, P.J.; Feng, C.; Skolarus, L.E. The role of the environment in falls among stroke survivors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017, 72, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid AA, Yaggi HK, Burrus N, et al. Circumstances and consequences of falls among people with chronic stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013, 50, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yue, S.; Wei, N.; Li, K. Analysis of center of mass acceleration and muscle activation in hemiplegic paralysis during quiet standing. PLoS One. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanas-Valdés, R.; Bagur-Calafat, C.; Girabent-Farrés, M.; Caballero-Gómez, F.M.; Hernández-Valiño, M.; Urrútia Cuchí, G. The effect of additional core stability exercises on improving dynamic sitting balance and trunk control for subacute stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016, 30, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung KS, In TS, Cho H young. Effects of sit-to-stand training combined with transcutaneous electrical stimulation on spasticity, muscle strength and balance ability in patients with stroke: A randomized controlled study. Gait Posture. 2017, 54, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaister, B.C.; Bernatz, G.C.; Klute, G.K.; Orendurff, M.S. Video task analysis of turning during activities of daily living. Gait Posture. 2007, 25, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyer, K.E.; Brassey, C.A.; Rose, K.A.; Sellers, W.I. Locomotion pattern and foot pressure adjustments during gentle turns in healthy subjects. J Biomech. 2017, 60, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco, L.A.; Silverman, A.K.; Gates, D.H. Whole-body and segment angular momentum during 90-degree turns. Gait Posture. 2019, 70, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Hudes ES. Risk Factors for Injurious Falls: A Prospective Study. Vol 46.; 1991.

- Osada, Y.; Motojima, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yamamoto, S. Abnormal Gait Movements Prior to a Near Fall in Individuals After Stroke. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüest, S.; Massé, F.; Aminian, K.; Gonzenbach, R.; de Bruin, E.D. Reliability and validity of the inertial sensor-based Timed “Up and Go” test in individuals affected by stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016, 53, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnyaud, C.; Pradon, D.; Vaugier, I.; Vuillerme, N.; Bensmail, D.; Roche, N. Timed Up and Go test: Comparison of kinematics between patients with chronic stroke and healthy subjects. Gait Posture. 2016, 49, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistamehr, A.; Kautz, S.A.; Bowden, M.G.; Neptune, R.R. Correlations between measures of dynamic balance in individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis. J Biomech. 2016, 49, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nott, C.R.; Neptune, R.R.; Kautz, S.A. Relationships between frontal-plane angular momentum and clinical balance measures during post-stroke hemiparetic walking. Gait Posture. 2014, 39, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.A.; Ricci, N.A.; Nogueira, E.C.; Perracini, M.R. The Berg Balance Scale as a clinical screening tool to predict fall risk in older adults: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2018, 104, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugl-Meyer A R JLLISS. fugl-meyer-1975-the_post-stroke-hemiplegic-patient. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975, 7, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chino N, Sonoda S, Domen K, Saitoh E, Kimura A. Stroke Impairment Assessment Set (SIAS)-A New Evaluation Instrument for Stroke Patients, 1994.

- Verheyden, G.; Nieuwboer, A.; Mertin, J.; Preger, R.; Kiekens, C.; De Weerdt, W. The Trunk Impairment Scale: A new tool to measure motor impairment of the trunk after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2004, 18, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Aoyagi, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Ishikawa, M. Quantitative evaluation of gait disturbance on an instrumented timed up-and-go test. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosetti, M.; Arie, L.; Kelly, J.; Ren, J.; Lubetzky, A.V. Dual task iTUG to investigate increased fall risk among older adults with bilateral hearing loss. American Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Medicine and Surgery, 2025; 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neťuková S, Klempíř O, Krupička R, et al. The timed up & go test sit-to-stand transition: Which signals measured by inertial sensors are a viable route for continuous analysis? Gait Posture. 2021, 84, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lummel RC, Walgaard S, Hobert MA, et al. Intra-rater, inter-rater and test-retest reliability of an instrumented timed up and Go (iTUG) test in patients with Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One, 2016; 11. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, T.L.; Murphy, T.E.; Tsui, K.L. Assessing elderly’s functional balance and mobility via analyzing data from waist-mounted tri-axial wearable accelerometers in timed up and go tests. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. QUANTITATIVE METHODS IN PSYCHOLOGY A Power Primer.

- Schober, P.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh Hollands, K.; Hollands, M.A.; Zietz, D.; Miles Wing, A.; Wright, C.; Van Vliet, P. Kinematics of turning 180° during the timed up and go in stroke survivors with and without falls history. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010, 24, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs JMB, Zandvliet SB, Schut IM, et al. Mild Stroke, Serious Problems: Limitations in Balance and Gait Capacity and the Impact on Fall Rate, and Physical Activity. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 2023; 37, 786–798. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Suzuki, A.; Hokkirigawa, K. Required coefficient of friction in the anteroposterior and mediolateral direction during turning at different walking speeds. PLoS One. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Muraki, T.; Izumi, S.I. The differences in sagittal plane whole-body angular momentum during gait between patients with hemiparesis and healthy people. J Biomech. 2019, 86, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, T.; Ogihara, N. Regulation of whole-body angular momentum during human walking. Sci Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mierlo M, Ambrosius JI, Vlutters M, van Asseldonk EHF, van der Kooij H. Recovery from sagittal-plane whole body angular momentum perturbations during walking. J Biomech, 2022; 141. [CrossRef]

- Yu HX, Wang ZX, Liu C Bin, Dai P, Lan Y, Xu GQ. Effect of Cognitive Function on Balance and Posture Control after Stroke. Effect of Cognitive Function on Balance and Posture Control after Stroke. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, Y.J.; Chang, M.C. Effectiveness of an ankle–foot orthosis on walking in patients with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese JC, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Nascimento LR, et al. The effects of walking sticks on gait kinematics and kinetics with chronic stroke survivors. Clinical Biomechanics. 2012, 27, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Rodrigues, B.; Gonçalves I de, O.; Asano, R.Y.; Uchida, M.C.; Marzetti, E. The physical capabilities underlying timed “Up and Go” test are time-dependent in community-dwelling older women. Exp Gerontol. 2018, 104, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).