1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the seventh most frequent cancer worldwide, the eighth in Spain [

1]. Its incidence has markedly increased in the last few decades in high-income countries, mainly due to improvements in imaging resolution at the detection stages [

2,

3]. The increase in incidence is limited to papillary carcinoma (PTC), a differentiated thyroid carcinoma, comprising 80-90% of cases, while the thyroid cancer-specific mortality rate has remained stable or slightly decreased [

4]. The prognosis for most patients with PTC is excellent. However, after initial surgery, nearly 11% of patients suffer from clinical or pathological recurrence [

4]. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) risk stratification system categorizes the recurrence risks into low, intermediate, and high, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor Node and Metastasis (AJCC TNM) system predicts risk of PTC-related mortality [

5]. Other, less common types of thyroid cancer are the poorly differentiated medullary thyroid carcinomas (MTCs) and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas (ATCs), the latter showing one of the most aggressive clinical behaviors among human cancers.

PTCs are mainly driven by constitutive activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathway, which is locked-in by mutually exclusive activating mutations in

BRAF (47-62%) and

RAS genes (4-13%), or by chimeric receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) bearing RET or NTRK3 constitutively active catalytic domains resulting from abnormal gene fusions (7-12%) [

6,

7]. The occurrence of molecular heterogeneity of PTC is evidenced by the fact that

NRAS and

HRAS mutations show variable prevalence in different histological subtypes, with low frequencies in classical PTC (cPTC, 1.3%) and frequencies as high as 48% in follicular variant PTC (fvPTC) or in minimally invasive PTC (miPTC) (25-50%)[

6,

7,

8].

RET gene fusions are almost exclusively harbored by cPTC. Mutations in the

TERT promoter are also highly enriched (about 10% prevalence) in these tumors, across histological subtypes [

6]. Other oncogenic driver alterations in PTCs include mutations in

EIF1AX [

6] or

MUC16 [

7] and gene fusions involving

BRAF,

PPARG,

NTRK1/3,

ALK,

ROS and

THADA [

6], representing potentially actionable alterations associated with well-differentiated PTC [

7]. Although PTC with “

BRAF only” or “

RAS only” mutations portend a good prognosis [

9], metastatic/aggressive cases are characterized by mutations in the

TERT promoter concurrent with oncogenic alterations in MAPK pathway components, notably

BRAF,

NRAS and

RET gain-of-function alterations, and

TP53 or

CDKN2A/

CDKN2B loss-of-function alterations [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Aggressive PTC and ATC tumors present higher frequency of combinations of driver mutations as compared to more differentiated thyroid cancers [

13].

The

RET gene encodes a transmembrane receptor with a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain and an extracellular domain that binds to the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored co-receptor GDNF family receptor-α (GFRα1-4), which engages Glial Cell-line Derived Neurotropic Factors (GDNF) family ligands (GFLs) [

14]. Binding of GFLs to GFRα1 causes dimerization of RET monomers in lipid raft domains, and phosphorylation on cytoplasmic tyrosine residues. Recruitment of adaptor proteins to these phosphotyrosines propagate signaling, allowing for activation of PI3K/AKT [

3,

14,

15]. RET signaling is vital for neural-neuroendocrine tissue development, renal morphogenesis, and spermatogonial stem cell maintenance [

14,

15].

Mutations in the extracellular domain of RET may cause ligand-independent dimerization through the generation of chimeric cytosolic domains that homodimerize to yield a constitutively active RET kinase signaling [

16]. The altered signaling dysregulates proliferation, survival, and causes metabolic changes [

7], including downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class-I expression, escape from immune surveillance, and loss of differentiated properties of thyroid epithelial cells such as iodine transport and metabolism [

7,

17], which underlies resistance to radioiodine therapy [

18].

RET fusions have been found in various neoplasms, including PTC, NSCLC, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, salivary gland adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [

15,

16,

19]. At least 13

RET fusion partners have been identified in PTC, most commonly coiled-coil domain containing 6 (

CCDC6-RET) and nuclear receptor co-activator 4 (

NCOA4)-

RET, and at least 45 fusion partners have been reported in NSCLC, very frequently kinesin family member 5B (

KIF5B)-

RET and

CCDC6-RET [

16]. While the

NCOA4-RET fusion is predominant in radiation-induced (

e.g., Chernobyl survivors) PTC [

20,

21,

22] and is associated with solid PTC, the

CCDC6-RET fusion is prevalent in sporadic PTC and is strongly associated with cPTC [

23]. On the other hand, activating mutations of

RET are found almost exclusively in MTC and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (MEN2A)[

16].

Ligand-independent RET activation is an actionable therapeutic target in PTCs and in subsets of NSCLC and other cancers. The tyrosine kinase activity of RET can be inhibited by non-selective multikinase inhibitors (MKI), including Cabozantinib and Vandetanib, primarily designed to target other kinases and displaying partial inhibition of RET [

24]. However, the response rates and durability to MKI of patients with RET-dependent cancers are relatively low, with substantial toxicity due to off-target side effects given their poor selectivity. The more recently developed RET-selective kinase inhibitors Selpercatinib [

24,

25,

26,

27] or Pralsetinib [

28,

29] offer significantly superior response rates and improved toxicity profiles [

30]. Both drugs have been approved by the FDA for use, among others, in adult and pediatric patients with metastatic thyroid cancer and RET fusion-positive advanced cancer, and patients with a RET variant MTC cancers [

31]

. In this context, the accurate and timely detection of RET oncogenic variants has a clear impact on the management of patients with RET-driven neoplasms [

3,

14,

32]. Several techniques can be used to assess the status of RET. The utility of immunohistochemistry for detecting RET fusions is limited by variable staining patterns and low reactivity [

33]. RT-PCR is both sensitive and specific for the detection of known fusions, but is not reliable for the detection of novel fusion partners [

33]. Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH), the gold standard technique for fusion detection, can be also performed relatively quickly and inexpensively [

33], but it is largely limited to the detection of a single driver alteration. Further, false-positive or false-negative events may occur for RET status detection in PTCs using the traditional FISH scoring method with break-apart probes [

34]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides the most comprehensive view across many genes and can identify RET gene fusions as well as other actionable alterations [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], including new BRAF mutations [

41], with minimal sample tissue needed. However, because of its high cost and the technical expertise required for interpretation, NGS is usually only available in larger reference centers [

15]. Furthermore, care must be taken when selecting NGS platforms that can reliably detect RET fusions, as not all assays are optimized to identify these oncogenic drivers [

42].

A barrier for the generalized use of NGS in clinical practice is a lack of consensus or standardized external quality control for approaches to detect

RET fusions, only a pilot Molecular Pathology EQA scheme focused in RET Validation was recently performed by GenQA (

www.genqa.org). In the present work, we show that NGS is a rapid, cost-effective method for the detection of

RET and other actionable fusions in PTCs, and demonstrate the robustness of the procedure through the establishment of external controls and interlaboratory comparisons.

2. Materials and Methods

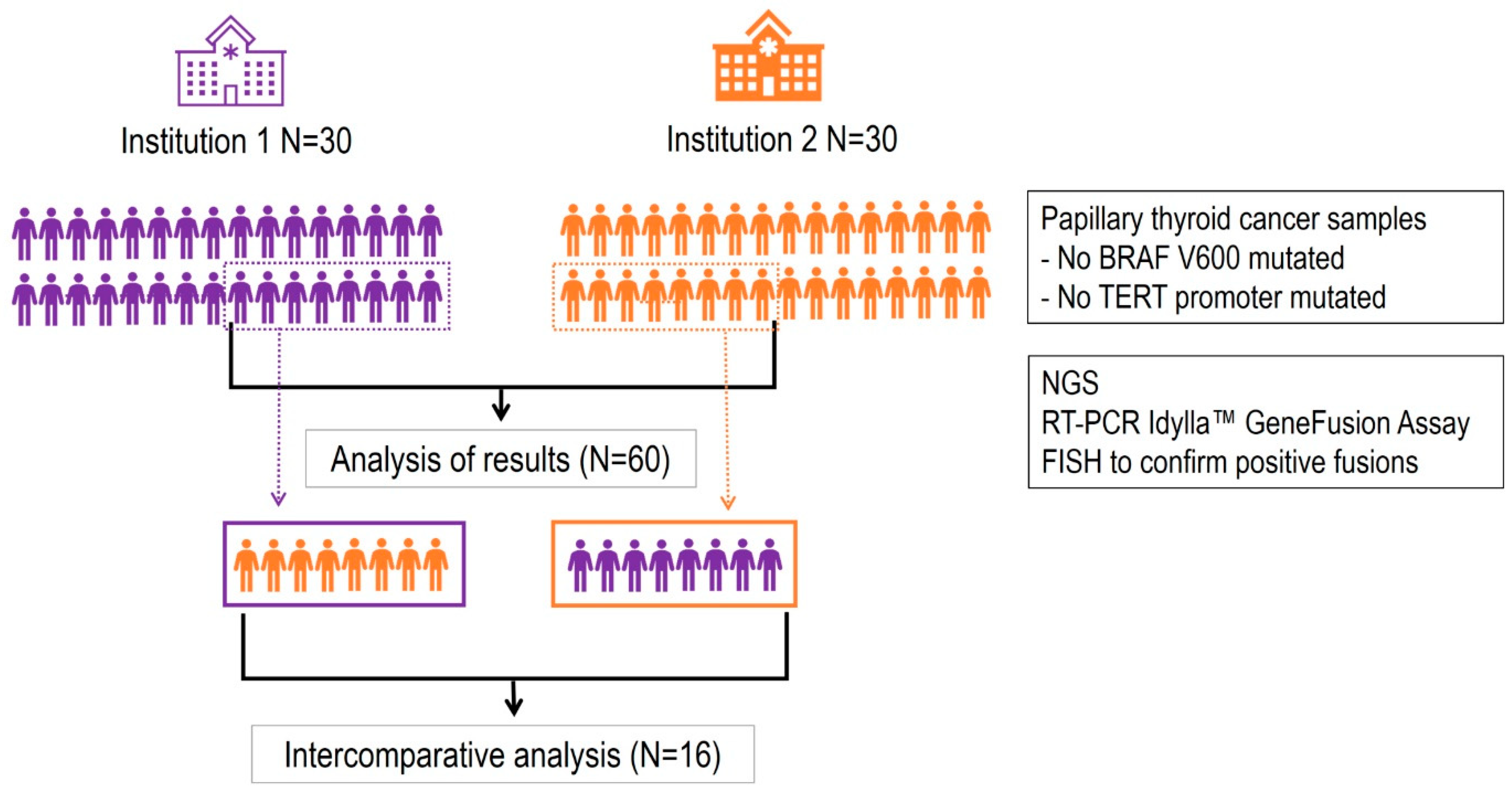

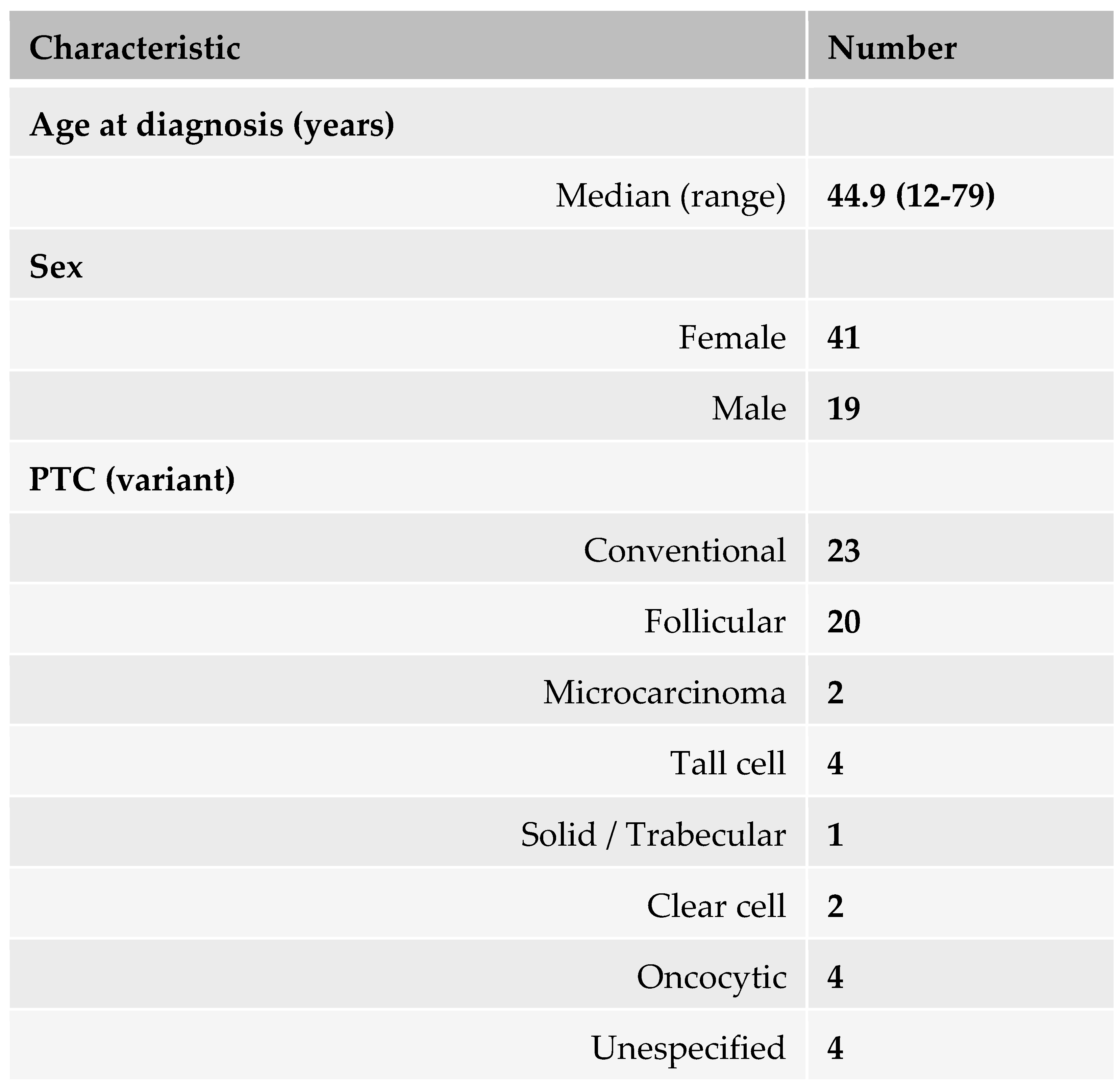

Patient selection. Sixty retrospective formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples of living patients diagnosed with PTC according according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine, 4th Edition (2017), were selected from two institutions: Hospital Vall d'Hebron and Hospital del Mar in Barcelona, Spain. The selection criteria were: (i) stage I or II PTC, (ii) no mutations in the BRAF V600 gene, and (iii) no mutations in the TERT promoter. All patients included in the study signed the informed consent that regulates the use of biological samples previously approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. The patient characteristics are described in

Table 1. Additional information is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

NGS testing. DNA and RNA extractions from patient biopsies were performed using the Cobas® DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics) and the High Pure FFPET RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics). After analysis of nucleic acid concentration using Qubit (ThermoFisher Scientific), a targeted NGS panel (Oncomine Focus Assay, ThermoFisher Scientific) was carried out following manufacturer instructions using the Ion Chef Instrument and S5 XL sequencer. Analysis of raw NGS data was performed using an Ion Torrent server and Ion Reporter Software version 5.12.3.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific). The assay includes 50 oncogenic driver hot-spot genes: AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, ALK, AR, ARAF, BRAF, CDK4, CDKN2A, CHEK2, CTNNB1, EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB3, ERBB4, ESR1, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, FLT3, GNA11, GNAQ, GNAS, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, KIT, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, MET, MTOR, NRAS, NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3, PDGFRA, PIK3CA, PTEN, RAF1, RET, ROS1, SMO, TP53. The assay also detects CNVs in 14 genes: ALK, AR, CD274, CDKN2A, EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB3, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, KRAS, MET, PIK3CA, PTEN; and interrogates fusions in 19 genes: ALK, AR, BRAF, EGFR, ESR1, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, MET, NRG1, NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3, NUTM1, RET, ROS1, RSPO2, RSPO3.

Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH). FISH technology, the gold standard technique with a dual color probe, was applied to confirm

RET-,

ALK- and

NTRK3-positive samples using the

RET (10q11.21),

ALK (2p23) and

NTRK3 (15q25.3) Break-Apart-FISH probes (Abbot Molecular), respectively, as previously described [

43].

Idylla(TM) GenFuiosn Assay. As an alternative to NGS technology, we used the IdyllaTM GeneFusion Assay (Biocartis, NV, Mechelen, Belgium), a RT-PCR multi-tests capable of simultaneous detection of multiple genes rearrangements in a fast and robust way. This assay qualitatively detects defined gene fusions for ALK, ROS1, RET, as well as MET Exon 14 skipping, and expression imbalance for ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK1/2/3. It is a fully automated assay providing deparaffinization and digestion of the tissue up to mRNA amplification by real time PCR, data analysis, and report of the results. Selected paraffin tissue sections were processed using this methodology (ref. A0121/6, Biocartis).

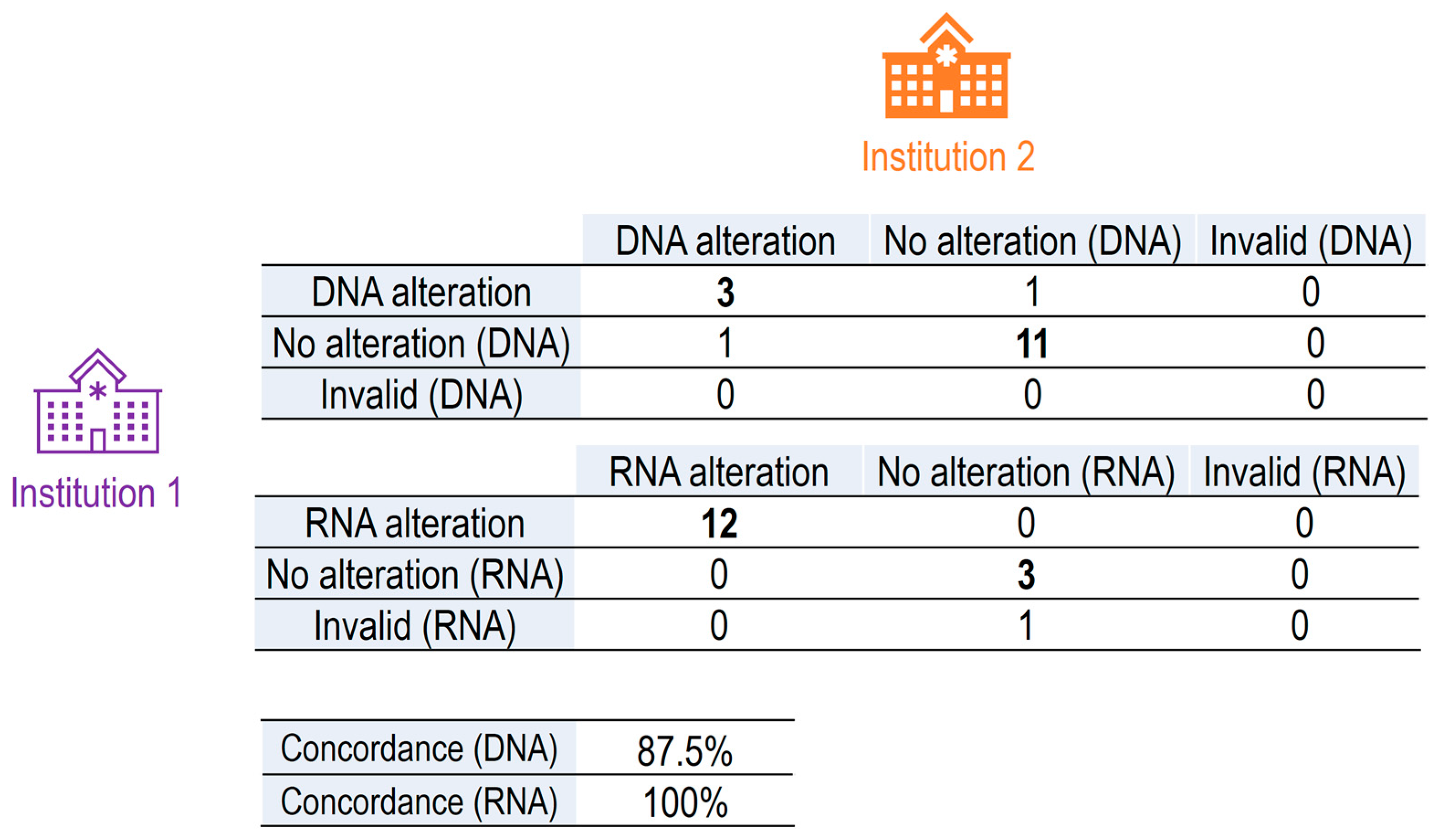

External quality control assessment. A total of 16 FFPE samples from thyroid cancer patients were selected, 8 from each hospital, including positive and negative cases for RET alteration. Concordance analysis was applied to verify the robustness of the chosen diagnostic tool for RET molecular analysis and the degree of reproducibility between measurements performed in each of the two hospitals. A positive concordance was defined as the same gene alteration found in both institutions, and negative concordance otherwise. The performance of the tests was calculated as positive and negative percent agreement (PPA and NPA, respectively), as follows: PPA = 100x PA (PA+PD), and NPA = 100xNA/(NA+ND), where PA is number of positive agreements, PD number of positive disagreements, NA number of negative agreements and ND number of positive disagreements. The Overall Percent Agreement (OPA) was also calculated: ORA = (PA + NA)/(PA+ PD + NA + ND).

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Gene Alterations in PTCs

To identify patients bearing actionable alterations in RET and hence eligible for targeted treatment with appropriate tyrosine kinase inhibitors, 60 retrospective tumor samples from living patients diagnosed with stage I and II PTC were analyzed by NGS (

Table 1). The tumors selected for this study lacked driver

BRAFV600 mutations and mutations in the

TERT promoter, (Supplementary Table 1). Further, as there is no consensus or standardized external quality assessment (EQA) for approaches to the detection of

RET fusions, an inter-comparative analysis was established to validate

RET molecular alterations detected by NGS at two distinct sites. More specifically, a concordance analysis was designed to determine the validity of the diagnostic assessment technique done in two independent institutions (Hospital Vall d'Hebron and Hospital del Mar). The study design is schematically illustrated in

Figure 1.

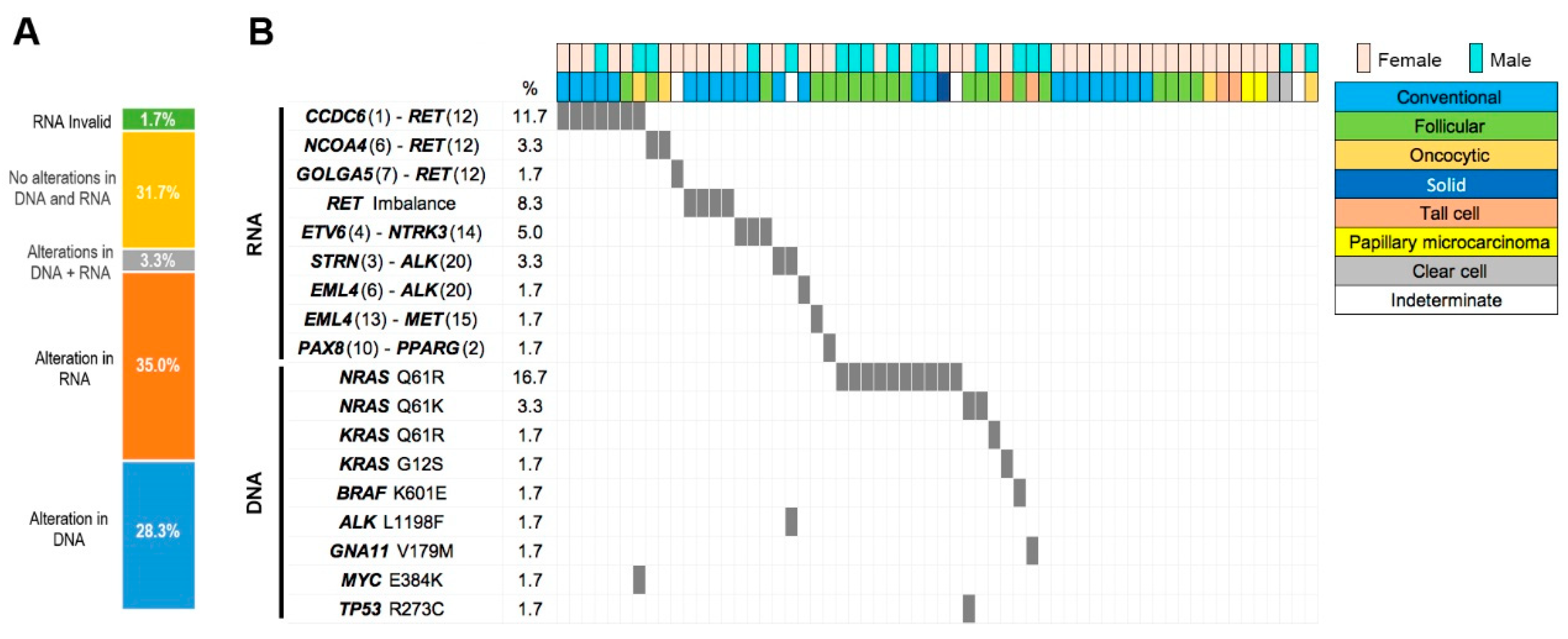

NGS analysis of all 60 samples revealed a high frequency of molecular alterations, detected in their RNA, DNA, or both (

Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). RNA alterations were observed in 21 (35%) tumors and DNA alterations in 17 (28.3%) tumors. Alterations in both RNA and DNA were found in 2 (3.3%) tumors, while the rest of tumors had no alterations in either RNA or DNA. “Invalid RNA” results were found in 1 tumor sample. Positive gene fusions were confirmed by FISH, using the appropriate probes for each different fusion detected, when available.

The large number of RNA alterations included fusions (n=19; 31.7%) and imbalances in genes important in thyroid cancer, with a high frequency (11 cases out of 19, 18.3% of all tumors, 57,9% of all gene fusions detected) of

RET fusions with different partners:

CCDC6::RET (n=8),

NCOA4::RET (n=2) and

GOLGA5::RET (n=1) (

Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). In addition, 4 cases with

RET imbalance were identified, indicating that the NGS panel detected overexpression of the downstream 3'

RET sequence of these cases, potentially derived from

RET gene fusions not included in the NGS panel (Oncomine Focus Assay). Apart from

RET fusions, the second most common fusions were with the

NTRK3 gene, where 3 samples showed the

ETV6-NTRK3 fusion, and in the

ALK gene (n=3; 5% of all cases), including

STRN-ALK (n=2; 3.3%), and

EML4-ALK (n=1; 1.7%). Other gene fusions included

EML4-MET (n=1; 1.7%) and

PAX8-PPARG (n=1; 1.7%) (

Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Nineteen tumors with DNA alterations bore SNVs in several genes (

NRAS,

KRAS,

ALK and

MYC). The most common alterations were mutations in

NRAS (n=13; 68,4%), mostly Q61R but also Q61K, mutations in

KRAS (n=2; Q61R and G12S) and

BRAF (n=1; K601E) (

Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). In contrast to the relatively high

NRAS mutation rate found in our PTC case series, the

NRAS mutation rates described in other studies range from 1% to about 8% in cPTC, with higher rates of

N/

H/

K RAS mutations in the fvPTC, FTC, miFTC and FA of the thyroid [

6,

8].

Of the 23 cases with gene fusions identified by NGS of RNA, 20 with sufficient sample were tested by FISH with probes for RET, ALK and NTRK3 (Supplementary Table 1). Two of the tested samples were not evaluable. Of the remaining 18 samples, 16 presented RET fusions detected by FISH, and three presented fusions involving ALK, namely two fusions involved STRN-ALK and one EML4-ALK.

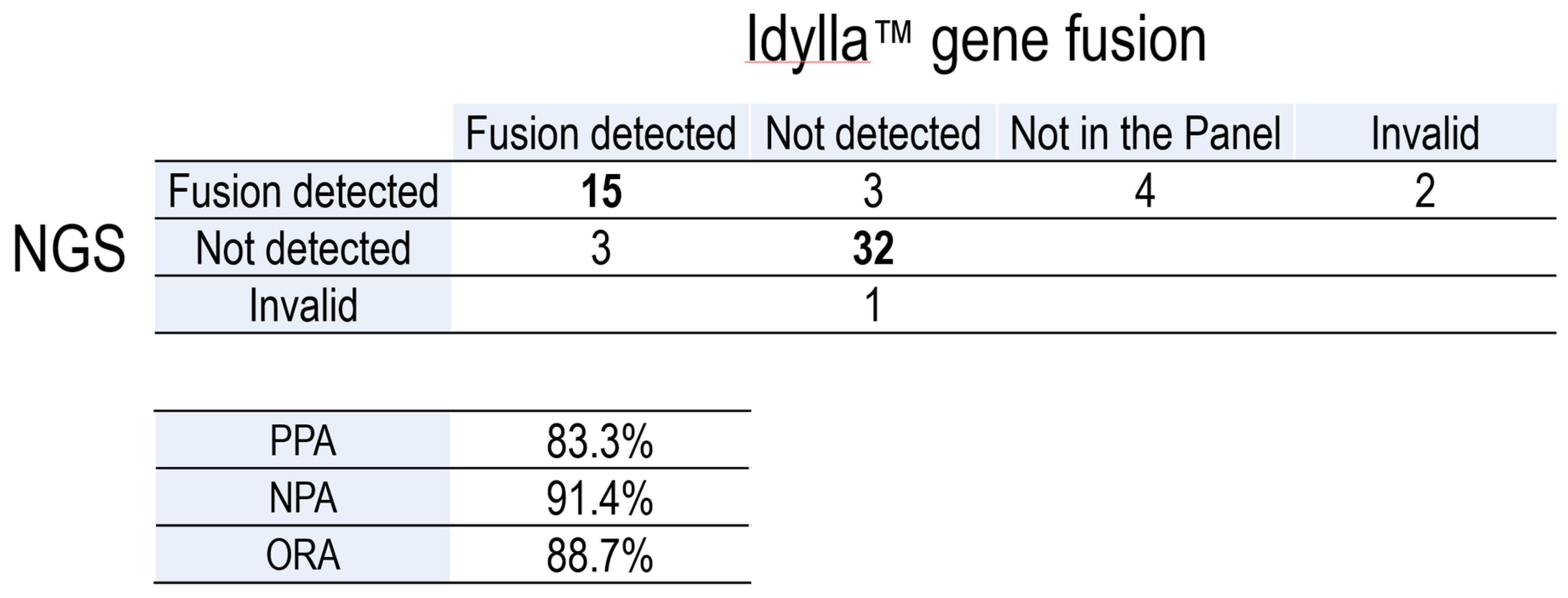

Gene fusions were further confirmed using a RT-PCR-based technique (Idylla) and the results were compared to those yielded by NGS (

Table 2, Supplementary Table 1). After excluding samples with a fusion not included in the Idylla panel and one invalid sample, we obtained a positive percent agreement (PPA) of 83.3% and a negative percent agreement (NPA) of 91.4%, with an overall percent agreement (OPA) of 88.7% between both techniques. As such, we conclude that Idylla is a robust procedure to detect gene fusions, especially

RET fusions, in PTC patients.

3.2. Inter-Hospital Concordance

To assess the degree of concordance between results obtained at different institutions, data were first inter-corrected, and 8 tumor samples (with positive or negative NGS results) were randomly selected from each institution. These samples were exchanged between both institutions and reanalyzed in a second round of nucleic acid extraction and NGS analysis (

Figure 1). In this second round of analysis, 1 RNA sample of the 16 interchanged failed in the NGS analysis (invalid) (

Table 3). This inter-hospital comparative study revealed a very high concordance rate for RNA analysis (12 positive alterations detected by both institutions) and DNA analysis (3 positive alterations detected by both institutions), the concordance rate being 100% for the detection of RNA alterations and 87.5% for the detection of DNA alterations.

4. Discussion

With the advent of new and potent RET-selective inhibitors, the accurate identification of tumors harboring actionable oncogenic alterations in this tyrosine kinase has become critical for the management of patients with advanced thyroid cancers and other RET-driven neoplasms. While fine needle aspiration is the most accurate and cost-effective method to stratify patients with thyroid tumors according to their risk of malignancy [

44], along with histopathological assessment of features such as capsular and vascular invasion [

45], conferring a further layer of precision, molecular analysis affords to refine cytological [

46,

47], histological and liquid biopsy [

48] diagnosis and to propose prognostic and predictive biomarkers as a guidance for attaining an optimal therapeutic strategy,

e.g., active surveillance, surgery, radioactive iodine, or targeted therapy.

The clinical use of molecular biomarkers, particularly in interinstitutional contexts, requires unified technical and analytical criteria for a robust guidance to patient management. The current absence of external quality programs that interrogate fusion detections in solid tumors by NGS makes this type of studies mandatory. Our study, conducted on 60 PTC samples from two independent clinical settings, has yielded a high degree of interinstitutional concordance in the identification of gene fusions and mutations detected by NGS, most notably through analyzing RNA.

Although the NGS platform used here (Oncomine Focus Assay) may have missed some gene fusions [

42], the frequency of fusions detected in our case series, 31.7% of all cases (18.3% with

RET fusions), is very close to that found in other studies, as accessed in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (cbioportal.org), namely 32% of cases with gene fusions in BRAFV600E-negative PTCs (17% with RET fusions) [

6]. Although the small number of cases studied here does not afford to reach strong conclusions with regards to fusions involving genes distinct from

RET, the frequencies of

ALK (5%),

NTRK3 (5%), and

PPARG (1.7%) fusions in our series are consistent with those in the TCGA database (1.5%

ALK, 5%

NTRK3, 3%

PPARG fusions in

BRAFV600E-negative PTCs). Overall, these concurring outcomes support the sensitivity and adequacy of our gene fusion analysis.

On the other hand, we found a relatively high rate of

NRAS mutations (21.7%) in our PTC case series, compared to the NRAS mutation rates previously described that range from 1% to about 8% in cPTC, with higher rates of N/H/KRAS mutations in fvPTC, FTC, miFTC and FA [

8,

23]. However, a recent review reported a wider range of prevalence for RAS mutations, from 20 to 100% in thyroid cancer. This high frequency might be a consequence of the tumor series heterogeneity coming from different geographic areas, different sources, and detection methods (direct sequencing, PCR-based approaches, or NGS technology) [

49]. Indeed, BRAF

V600E mutations and

RET,

NTRK3 and

BRAF fusions (

BRAF-like tumors) are strongly associated with cPTC, while tumors dubbed RAS-like (

N/H/KRAS, EIF1AX, BRAFK601E, PTEN, IDH2, DICER1 mutations and

PPARG and

THADA fusions) are associated with follicular variant and minimally invasive papillary histologies [

6,

8].

5. Conclusions

The routine implementation of NGS analysis in patients with PTC could be useful to identify patients harboring different fusions (RET, NTRK, MET) who may benefit from targeted therapies with new target-selective or multikinase inhibitors (MKI). In the present work, we demonstrate that NGS is a rapid, reliable method for the detection of RET and other actionable fusions in PTCs, and show that the establishment of external controls and interlaboratory comparisons provides a robust procedure.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Table 1, (The tumors selected for this study lacked driver BRAFV600 mutations and mutations in the TERT promoter) (Supplementary Table S1).

Author Contributions

Concept and design: M. Sesé, S. Clavé, B. Bellosillo and J. Hernandez-Losa. Development of methodology: M. Sesé, S. Clavé, R. Somoza. Data acquisition: C. Zafón, C. Iglesias, J. Hernando, J. Capdevila, M. Sesé, S. Clavé, B. Bellosillo, J. Hernández-Losa. Data analysis and interpretation: M. Sesé, S. Clavé. Writing: M. Sesé, J. Hernández-Losa. Review of paper: M. Sesé, S. Clavé, J. Hernández-Losa, B. Bellosillo, C. Iglesias, C. Zafón. Study supervision: M. Sesé, B. Bellosillo, J. Hernández-Losa., B.LLoveras.

Funding

This study was mainly funded by Lilly through an agreement with Fundació Hospital Universitari Vall d´Hebron – Institut de Recerca (“VHIR”) and Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (“HUVH”). Additional support was provided by Biocartis, which supplied Idylla™ GeneFusion Assays under a grant agreement.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Research (protocol code PR(AG)495-2021).

Informed Consent Statement and Ethics approval:

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON.

Conflicts Of Interest Declaration

JHL declares scientific consultancy role (speaker and advisory roles) from Pfizer, Bayer, Amgen, Lilly, Roche, Astrazeneca, Owkin, Jannssen, MSD and Thermofisher. S declares no conflicts of interest in the present study. CZ declares speakers Bureaus from Lilly. JH declares speakers Bureaus from Novartis, Ipsen, AAA, Lilly, Elisai, Terumo and Angellini. JC declares scientific consultancy role (speaker and advisory roles) from Novartis, Pfizer, Ipsen, Exelixis, Bayer, Eisai, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Amgen, Sanofi, Lilly, Hudchmed, ITM, Merck Serono, Roche, Esteve, Advanz; research grants from Novartis, Pfizer, Astrazeneca, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Eisai, Amgen, ITM, Roche, Gilead and Bayer.

References

- F. Bray et al., “Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries,” CA. Cancer J. Clin., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 229–263, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Pizzato et al., “The epidemiological landscape of thyroid cancer worldwide: GLOBOCAN estimates for incidence and mortality rates in 2020,” Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 264–272, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Boucai, M. Zafereo, and M. E. Cabanillas, “Thyroid Cancer: A Review,” JAMA, vol. 331, no. 5, p. 425, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Jegerlehner et al., “Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of thyroid cancer: A population-based temporal trend study,” PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 6, p. e0179387, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Tuttle, B. Haugen, and N. D. Perrier, “Updated American Joint Committee on Cancer/Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging System for Differentiated and Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer (Eighth Edition): What Changed and Why?,” Thyroid, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 751–756, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Agrawal et al., “Integrated Genomic Characterization of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma,” Cell, vol. 159, no. 3, pp. 676–690, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Qu et al., “Integrated proteogenomic and metabolomic characterization of papillary thyroid cancer with different recurrence risks,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 3175, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S.-K. Yoo et al., “Comprehensive Analysis of the Transcriptional and Mutational Landscape of Follicular and Papillary Thyroid Cancers,” PLOS Genet., vol. 12, no. 8, p. e1006239, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Ahmadi and I. Landa, “The prognostic power of gene mutations in thyroid cancer,” Endocr. Connect., vol. 13, no. 2, p. e230297, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Xing et al., “BRAF V600E and TERT Promoter Mutations Cooperatively Identify the Most Aggressive Papillary Thyroid Cancer With Highest Recurrence,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 32, no. 25, pp. 2718–2726, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Liu et al., “The age- and shorter telomere-dependent TERT promoter mutation in follicular thyroid cell-derived carcinomas,” Oncogene, vol. 33, no. 42, pp. 4978–4984, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Máximo et al., “Genomic profiling of primary and metastatic thyroid cancers,” Endocr. Relat. Cancer, vol. 31, no. 2, p. e230144, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. P. Krishnamoorthy et al., “EIF1AX and RAS Mutations Cooperate to Drive Thyroid Tumorigenesis through ATF4 and c-MYC,” Cancer Discov., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 264–281, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Mulligan, “GDNF and the RET Receptor in Cancer: New Insights and Therapeutic Potential,” Front. Physiol., vol. 9, p. 1873, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A.Y. Li et al., “RET fusions in solid tumors,” Cancer Treat. Rev., vol. 81, p. 101911, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Regua, M. Najjar, and H.-W. Lo, “RET signaling pathway and RET inhibitors in human cancer,” Front. Oncol., vol. 12, p. 932353, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Xu et al., “Identification of Key Functional Gene Signatures Indicative of Dedifferentiation in Papillary Thyroid Cancer,” Front. Oncol., vol. 11, p. 641851, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Nagarajah et al., “Sustained ERK inhibition maximizes responses of BrafV600E thyroid cancers to radioiodine,” J. Clin. Invest., vol. 126, no. 11, pp. 4119–4124, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Shi et al., “Identification of RET fusions in a Chinese multicancer retrospective analysis by next-generation sequencing,” Cancer Sci., vol. 113, no. 1, pp. 308–318, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Thomas et al., “High Prevalence of RET/PTC Rearrangements in Ukrainian and Belarussian Post-Chernobyl Thyroid Papillary Carcinomas: A Strong Correlation between RET/PTC3 and the Solid-Follicular Variant1,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., vol. 84, no. 11, pp. 4232–4238, Nov. 1999. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Morton et al., “Radiation-related genomic profile of papillary thyroid carcinoma after the Chernobyl accident,” Science, vol. 372, no. 6543, p. eabg2538, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Ricarte-Filho et al., “Identification of kinase fusion oncogenes in post-Chernobyl radiation-induced thyroid cancers,” J. Clin. Invest., vol. 123, no. 11, pp. 4935–4944, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. E. Nikiforov and M. N. Nikiforova, “Molecular genetics and diagnosis of thyroid cancer,” Nat. Rev. Endocrinol., vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 569–580, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Drilon, Z. I. Hu, G. G. Y. Lai, and D. S. W. Tan, “Targeting RET-driven cancers: lessons from evolving preclinical and clinical landscapes,” Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 151–167, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Subbiah et al., “Selective RET kinase inhibition for patients with RET-altered cancers,” Ann. Oncol., vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 1869–1876, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Drilon et al., “Efficacy of Selpercatinib in RET Fusion–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 383, no. 9, pp. 813–824, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Wirth et al., “Efficacy of Selpercatinib in RET -Altered Thyroid Cancers,” N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 383, no. 9, pp. 825–835, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Subbiah et al., “Pan-cancer efficacy of pralsetinib in patients with RET fusion–positive solid tumors from the phase 1/2 ARROW trial,” Nat. Med., vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 1640–1645, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Gainor et al., “Pralsetinib for RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARROW): a multi-cohort, open-label, phase 1/2 study,” Lancet Oncol., vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 959–969, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Nardo et al., “Strategies for mitigating adverse events related to selective RET inhibitors in patients with RET-altered cancers,” Cell Rep. Med., vol. 4, no. 12, p. 101332, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Duke et al., “FDA Approval Summary: Selpercatinib for the Treatment of Advanced RET Fusion-Positive Solid Tumors,” Clin. Cancer Res., vol. 29, no. 18, pp. 3573–3578, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Filetti et al., “Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up,” Ann. Oncol., vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1856–1883, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Belli et al., “ESMO recommendations on the standard methods to detect RET fusions and mutations in daily practice and clinical research,” Ann. Oncol., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 337–350, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, S. Wu, L. Zhou, Y. Guo, and X. Zeng, “Pitfalls in RET Fusion Detection Using Break-Apart FISH Probes in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., vol. 106, no. 4, pp. e1129–e1138, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Moore et al., “Next-generation sequencing in thyroid cancers: do targetable alterations lead to a therapeutic advantage?: A multicenter experience,” Medicine (Baltimore), vol. 100, no. 25, p. e26388, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Qi et al., “Somatic Mutation Profiling of Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas by Whole-exome Sequencing and Its Relationship with Clinical Characteristics,” Int. J. Med. Sci., vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 2532–2544, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Bandoh et al., “Targeted next-generation sequencing of cancer-related genes in thyroid carcinoma: A single institution’s experience,” Oncol. Lett., Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Scholfield et al., “Defining the Genomic Landscape of Diffuse Sclerosing Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma: Prognostic Implications of RET Fusions,” Ann. Surg. Oncol., vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 5525–5536, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. X. Ma et al., “Clinical Application of Next-Generation Sequencing in Advanced Thyroid Cancers,” Thyroid, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 657–666, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen et al., “Molecular Profile of Advanced Thyroid Carcinomas by Next-Generation Sequencing: Characterizing Tumors Beyond Diagnosis for Targeted Therapy,” Mol. Cancer Ther., vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 1575–1584, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Capezzone et al., “Identification of a Novel Non-V600E BRAF Mutation in Papillary Thyroid Cancer,” Case Rep. Endocrinol., vol. 2024, pp. 1–5, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Heydt et al., “Detection of gene fusions using targeted next-generation sequencing: a comparative evaluation,” BMC Med. Genomics, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 62, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Martinez et al., “Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry as Diagnostic Methods for ALK Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients,” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 1, p. e52261, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Lebrun and I. Salmon, “Pathology and new insights in thyroid neoplasms in the 2022 WHO classification,” Curr. Opin. Oncol., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 13–21, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. W. Baloch et al., “Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms,” Endocr. Pathol., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 27–63, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Akahane et al., “Cancer gene analysis of liquid-based cytology specimens using next-generation sequencing: A technical report of bimodal DNA - and RNA -based panel application,” Diagn. Cytopathol., vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 493–500, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Shang et al., “Correlation between genetic alterations and clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid carcinomas,” J. Int. Med. Res., vol. 52, no. 3, p. 03000605241233166, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. D. Tarasova et al., “Characterization of the Thyroid Cancer Genomic Landscape by Plasma-Based Circulating Tumor DNA Next-Generation Sequencing,” Thyroid®, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 197–205, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Marotta, M. Bifulco, and M. Vitale, “Significance of RAS Mutations in Thyroid Benign Nodules and Non-Medullary Thyroid Cancer,” Cancers, vol. 13, no. 15, p. 3785, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).