1. Introduction

Nearly half of all cases of infertility are caused by male infertility [

1], male infertility is idiopathic in approximately 30-40% of cases [

2]. Pregnancy rates per embryo transfer using ART remain relatively low [

3]. One of the key challenges is the current lack of effective methods to isolate this specific sperm subpopulation for use in ART [

4].

Artificial intelligence is playing a pivotal role in driving transformative changes across the medical technology field. The application of AI in medicine has advanced from single-modal analysis to sophisticated multi-dimensional intelligent systems, with its technical framework encompassing machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), multi-modal fusion, and intelligent robotics. This evolution has significantly improved the efficiency of disease diagnosis, treatment planning, and medical resource allocation [

5,

6,

7].

The emergence of multimodal AI has further transcended the limitations of single-source data, with its primary aim being to overcome the constraints of traditional empirical medicine through data-driven intelligent systems [

8]. As one of the most intricate clinical application scenarios in reproductive medicine, ART encompasses multi-dimensional decision-making processes such as follicular monitoring, dynamic embryo assessment, and IVF outcome prediction. There is an urgent need for intelligent analysis systems capable of integrating multimodal heterogeneous data, including time-series embryo images, genomic maps, clinical biochemical indicators, and patient electronic health records [

9,

10]. In recent years, artificial intelligence systems have progressively transformed the clinical decision-making paradigm in assisted reproductive technology by leveraging multimodal data integration [

11].

This article focuses on the clinical translation of multimodal artificial intelligence technology in sperm screening for assisted reproductive technology. By combining dynamic functional analysis with molecular feature recognition, it systematically investigates the innovative approaches of intelligent algorithms to enhance the accuracy of sperm motility assessment and optimize metabolic function evaluation, thereby offering multi-dimensional and precise strategies for clinical evaluation and decision-making in ART.

2. The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence

The term artificial intelligence was first formally introduced by John McCarthy at the Dartmouth Conference in 1956. McCarthy defined AI as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines,” with the core objective of replicating human cognitive abilities such as reasoning, learning, perception, and language understanding through algorithms and computational models [

12,

13]. The introduction of this concept not only inaugurated a new domain within computer science but also marked a pivotal shift in humanity’s exploration of intelligence, transitioning from philosophical speculation to practical technological implementation [

14,

15].

In the field of medical imaging diagnosis, AI has emerged as a robust image analysis tool, aiding radiologists in early disease detection and reducing misdiagnosis rates [

16]. For instance, AI has shown promising results in the early identification of various diseases, including breast cancer, skin cancer, ophthalmic conditions, and pneumonia [

16,

17]. Additionally, AI can be utilized for predicting disease risk and managing health outcomes. Studies have utilized machine learning models to predict the likelihood of diabetes onset, with an enhanced decision tree model demonstrating superior performance in forecasting diabetes-related variables [

18,

19]. In drug development, AI also exhibits significant potential. AI utilizing bioinformatics and chemoinformatic can significantly reduce the time and cost associated with drug discovery [

16,

20]. Overall, AI is driving innovation in healthcare, encompassing areas such as medical imaging, disease prediction, and drug discovery [

21].

Figure 1.

AI + Human Brain > Brain: A Minimalist Vision of Intelligent Medicine.

Figure 1.

AI + Human Brain > Brain: A Minimalist Vision of Intelligent Medicine.

3. The Paradigmatic Innovation and Multi-dimensional Empowerment of Medical AI Approaches in ART

AI methods are typically categorized into supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised approaches.

Supervised learning, grounded in meticulous annotations, enables precise analysis of germ cells in microscopic images [

22,

23]. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) utilizing high-resolution microscopic images can accurately detect subcellular structural variations in sperm—such as acrosome integrity and mitochondrial sheath defects—achieving discrimination accuracy that surpasses traditional manual microscopic examination standards [

24,

25,

26]. Cross-modal supervised models further integrate spectral data and dynamic parameters to enable non-invasive quantitative assessment of the DNA fragmentation index, thereby significantly reducing the clinical risks associated with invasive testing [

27,

28].

Semi-supervised, guided by clinical endpoints, addresses the practical challenge of limited annotation resources by leveraging coarse or indirect labels [

29]. In analysing testicular tissue pathology sections, researchers employ a multi-instance learning framework to locate spermatogenic functional units by associating surgical outcome labels with specific tissue features, providing interpretable decision-making support for predicting sperm detection rates [

30,

31]. This approach effectively correlates overall surgical outcomes with local tissue features, enhancing both the interpretability and predictive performance of the model [

32]. Cross-modal contrastive learning, through unsupervised alignment of motion trajectories and metabolic features, uncovers the potential regulatory mechanisms of oxidative stress levels on flagellar movement patterns, paving new pathways for diagnosing and treating male infertility [

24,

33,

34].

Unsupervised learning, utilizing advanced algorithms, explores biological principles beyond empirical observations [

35,

36]. Self-supervised contrastive clustering techniques have identified clinically significant novel kinetic subgroups from large-scale motion parameters, with helical propulsion patterns showing a significant positive correlation with fertilization success rates [

37,

38,

39]. The generative model synthesizes a sperm image library with controllable pathological characteristics, effectively addressing the generalization limitations of algorithms caused by the scarcity of data on rare sperm morphological abnormalities [

40,

41].

Table 1.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms used to evaluate sperm morphology.

Table 1.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms used to evaluate sperm morphology.

| Model Name |

Subtype |

Application |

| Supervised Learning |

Cross-modal models, Deep CNNs |

Acrosome integrity detection, DNA fragmentation index prediction |

| Semi-Supervised Learning |

Multi-instance learning, Attention-based models |

Testicular tissue analysis, sperm detection prediction |

| Unsupervised Learning |

Self-supervised clustering, GANs |

Kinetic subgrouping, sperm motion pattern discovery |

| Generative Models |

DCGAN, VAE |

Synthetic sperm image generation for rare cases |

| Transformer Models |

Biomedical Transformers |

Multimodal fusion, sperm DNA prediction |

| Contrastive Learning |

Cross-modal alignment, Self-supervised contrastive clustering |

Motion-metabolic pattern alignment, sperm phenotype matching |

| Explainable AI (XAI) |

Grad-CAM, Visual heatmaps |

Interpretable sperm quality prediction |

| Meta-learning & Causal Reasoning |

Causal representation learning |

Generalizable and interpretable sperm screening |

4. The Technological Evolution of Multimodal Data Fusion and the Paradigm Shift in Medical Interpretation

Multimodal data fusion is reshaping the analytical dimension of complex biological systems by leveraging the complementarity and synergy of heterogeneous data sources [

6]. Supervised learning establishes precise cross-modal mapping benchmarks; semi-supervised learning mitigates the limitations posed by scarce annotated data; and unsupervised learning uncovers intrinsic data associations. [

42,

43] These three approaches form a closed-loop optimization through techniques such as adversarial training, contrastive learning, and generative models.

Supervised learning establishes robust associations between modalities using annotated data [

44]. In medical image diagnosis, the XLIP framework employs cross-modal attention masking strategies to interactively exchange multi-modal features between annotated medical images and pathological reports, reconstructing both the image features and textual descriptions of lesion areas, thereby enhancing the learning of pathological characteristics [

45]. In drug development, hierarchical fusion architectures guided by supervised signals (e.g., Stacking frameworks) optimize the allocation of multi-modal feature weights, integrating molecular structure data with clinical trial results, which significantly improves the cross-modal interpretability of drug efficacy predictions [

6,

46]. Additionally, joint training strategies promote complementary information exchange between modalities through supervised loss functions [

47]. Supervised transfer learning combines single-modal pre-trained models (e.g., ImageNet-pretrained CNNs) with newly introduced supervised data from other modalities [

48,

49], enabling rapid adaptation to multi-modal tasks [

50].

semi-supervised facilitates semantic alignment between modalities using sparsely labelled data [

51]. In pathological analysis, only malignant regions of some tissue sections are labelled, and a contrastive learning framework correlates pathological image features with unlabelled proteomics data across scales, revealing morphological-molecular interaction patterns [

52]. Additionally, semi-supervised fusion models incorporating attention mechanisms, such as multi-instance learning, address discrepancies in annotation granularity between modalities [

53]. Adversarial training frameworks enhance the robustness of semi-supervised fusion models [

54]. Furthermore, pre-training Transformer architectures using unlabelled medical images and electronic health records captures latent cross-modal patterns of disease progression [

6]. This approach offers an efficient and interpretable multimodal fusion pathway for medical image analysis, drug development, and other domains by reducing labelling costs and mining cross-modal relationships.

Unsupervised learning highlights the superior performance of contrastive learning frameworks in unsupervised multi-modal alignment [

55]. Through modal negative sampling strategies, it enhances feature discriminability, and adversarial generative networks (GANs) achieve cross-modal data distribution matching [

56]. The Conditional Alignment Time Diffusion (CATD) framework proposed by Yao et al. aligns electroencephalogram (EEG) signals with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) images in a latent space, uncovering cross-modal dynamic mechanisms of neural activities [

57]. Variational autoencoders (VAEs) model the joint distribution of multi-modal data, enabling the generation of virtual compounds that satisfy both structural features and activity predictions in drug design [

58,

59]. Additionally, constructing cross-modal associations of organ anatomical structures through unsupervised contrastive learning, followed by fine-tuning attention mechanisms with weakly labelled lesion annotations, optimizes diagnostic decision-making under full supervision [

60,

61]. This hierarchical supervision mechanism achieves an optimal balance between data labelling costs and model performance [

62]. In mixed supervision learning models, meta-learning frameworks adaptively adjust the weights of different supervision signals, enhancing model generalization [

63]. Incorporating causal reasoning modules distinguishes correlations from causations among variables, thereby improving the interpretability of decisions made by mixed supervision models [

64]. The combination of meta-learning and causal reasoning not only boosts model performance but also enhances adaptability and reliability in complex tasks.

The essence of multimodal data fusion lies in constructing alignment and mapping mechanisms across domain feature spaces to fully exploit the complementarity of different modalities [

65]. Spatio-temporal convolution architectures extract dynamic patterns of organ function evolution from dynamic image sequences and form spatio-temporally coupled joint representations with genomic features [

66]. Self-supervised contrastive learning frameworks overcome the semantic limitations of traditional single-modal representations, achieving cross-scale semantic alignment of pathological image texture features and proteomics molecular markers [

49,

67], revealing the dynamic interaction network of morphology, function, and molecules during disease progression. Generative models mitigate distribution shifts arising from multimodal data heterogeneity by modelling joint distributions in latent space [

68]. In the medical field, research on cross-modal intervention counterfactual models is emerging. For instance, Hu et al. proposed the interpretable multimodal fusion network gCAM-CCL, which performs automatic diagnosis and result interpretation simultaneously. The gCAM-CCL model generates interpretable activation maps by combining intermediate feature maps with gradient-based weights, thereby quantifying pixel-level contributions of input features [

69]. These multimodal data technologies offer cross-dimensional evidence chains for clinical decision-making, signifying a shift in medical artificial intelligence from fragmented single-modal analyses to system-level integrated diagnostics.

5. The Limitations of Traditional Sperm Screening Methods and Potential Directions for Breakthrough

In ART, traditional sperm screening predominantly depends on static morphological parameters, such as head shape, acrosome integrity, and flagellar structure. However, the inherent limitations of this approach have become increasingly evident, particularly in its inability to assess dynamic functionalities and genetic integrity. The traditional two-dimensional morphological assessment system is fundamentally grounded in empirical thresholds and thus limited to reflecting the phenotypic characteristics of sperm at a single time point, failing to capture critical biological information such as dynamic functionality and genetic integrity [

24,

70,

71]. A mechanistic study by Komatsu et al. provides compelling evidence supporting this limitation. Although sperm selected based on traditional morphological criteria can form high-quality embryos, their mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) may consistently remain below the threshold observed in embryos derived from in vivo fertilization. Additionally, significant mitochondrial ultrastructural abnormalities may be detected. Consequently, the failure to incorporate dynamic evaluations of mitochondrial function may increase the risk of embryo arrest [

72].

At the molecular level, Zhao et al. demonstrated that sperm with reduced expression of the Mfn2 gene maintained normal morphology but had diminished embryonic developmental potential due to compromised mitochondrial fusion [

73]. Collectively, these findings highlight a fundamental disconnect between traditional morphological assessments and the functional status of sperm mitochondria. Therefore, overcoming the limitations of static morphological assessments and developing a multimodal framework that integrates dynamic functionality, molecular integrity, and three-dimensional morphology is a critical scientific challenge to improve the success rates of ART.

6. The Application of Multimodal Data Integration Strategies in Sperm Screening

Theoretical breakthroughs in artificial intelligence for sperm screening have fundamentally redefined the evaluation criteria for “high-quality sperm” in reproductive medicine. This advancement addresses the limitations of traditional static morphological assessments by integrating dynamic functional data and genomic information through cross-scale modelling, thereby enabling the simultaneous evaluation of sperm morphology, motility, and genetic integrity.

Figure 2.

An integrated pipeline of multimodal artificial intelligence for sperm screening.

Figure 2.

An integrated pipeline of multimodal artificial intelligence for sperm screening.

6.1. Strategies for Sperm Morphology Assessment

Assessing sperm morphology is crucial for the success of assisted reproductive technologies. Normal sperm morphology indicates proper development, essential for fertilization, and correlates positively with successful pregnancy outcomes. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established morphological criteria, defining normal semen samples as those containing at least 4% morphologically normal sperm [

74]. However, compared to other parameters such as sperm concentration and motility, standardizing sperm morphology assessment has proven particularly challenging [

75]. Traditional methods primarily rely on staining techniques to evaluate static structural features, including head shape, acrosome integrity, and midpiece dimensions [

76]. These approaches are limited by subjectivity, potential staining effects on sperm motility, and lack of dynamic physiological data [

24].

Integrating multimodal data strategies offers innovative solutions for assessing sperm morphology. By combining diverse data sources, including microscopic imaging, molecular markers, and computer vision, a more comprehensive and objective evaluation of sperm morphology can be achieved. Yoav N. Nygate et al. developed HoloStain, a deep learning method that integrates holographic microscopy with virtual staining technology to analyse individual sperm cells without chemical staining. This approach uses quantitative phase imaging for high-resolution morphological features and employs a deep convolutional generative adversarial network (DCGAN) to generate virtual staining images. Consequently, HoloStain provides an accurate, artifact-free assessment of sperm morphology by eliminating potential distortions caused by traditional staining methods [

77]. Kamieniczna et al. utilized digital holographic microscopy (DHM) for the morphological evaluation of live sperm, overcoming limitations of conventional techniques. DHM, a non-contact, label-free imaging technology, avoids compromising sperm activity and provides three-dimensional morphological parameters, including detailed head and tail characteristics [

25].

Figure 3.

The three-dimensional structure, flagellar movement and biological characteristics of sperm cells.

Figure 3.

The three-dimensional structure, flagellar movement and biological characteristics of sperm cells.

Zou et al. designed TOD-CNN, a convolutional neural network for detecting sperm cells in microscopic videos. The model was trained on an extensive dataset of 111 high-quality sperm videos, encompassing over 278,000 annotated instances, and achieved an impressive average precision (AP₅₀) of 85.60% in real-time sperm detection tasks. Integrating TOD-CNN into multimodal data strategies is anticipated to significantly enhance the comprehensiveness and precision of sperm morphology evaluations [

78]. Dardikman-Yoffe et al. introduced an innovative high-resolution, stain-free imaging technique for optical computed tomography (CT) of freely swimming sperm. This approach reconstructs the three-dimensional trajectories and structures of individual sperm cells, capturing intricate details of internal organelles and flagellar dynamics. Employing a high-speed off-axis holographic system, this technique images live sperm without the need for cell staining or mechanical stabilization. The reconstruction process relies solely on the sperm’s natural movement and advanced computational algorithms, enabling precise four-dimensional reconstructions [

79]. By leveraging these extensive datasets, artificial intelligence can construct dynamic models to enhance sperm morphology assessments [

80].

6.2. Evaluate the Motility Characteristics of Individual Spermatozoa with Precision

In the assessment of individual sperm motility, traditional methods have predominantly relied on microscopic examination and computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA). While conventional microscopic examination requires trained laboratory personnel to evaluate sperm motility through visual observation of movement patterns, this methodology remains vulnerable to observer subjectivity, thereby limiting both the reproducibility and diagnostic accuracy of results [

81]. The CASA system addresses these limitations by offering standardized quantitative assessment of sperm motility characteristics and morphological parameters via automated tracking algorithms coupled with video microscopy [

82]. Nevertheless, traditional CASA platforms demonstrate reduced diagnostic reliability when analysing semen specimens with extreme concentrations (hyper-concentrated or hypoconcentrated), particularly in scenarios involving cellular contaminants such as non-gamete cells and particulate debris [

83]. These limitations underscore the need for methodological refinements in conventional semen analysis techniques.

The integration of multimodal artificial intelligence technology, which combines high-resolution imaging of sperm trajectories, physiological signals, and molecular-level information, offers more objective, accurate, and efficient solutions for sperm motility assessment. Klumpp et al. developed the Syntalos software, enabling synchronized operation across multiple devices and facilitating the detection of complex correlations between behaviour and single-cell activities. By integrating high-resolution imaging of sperm trajectories with synchronous physiological signal recording, this multimodal data synchronization function allows simultaneous tracking of sperm motility behaviour and associated physiological parameters. This integration provides a more comprehensive analytical framework for assessing sperm motility. Compared to traditional sperm motility assessment methods, which predominantly rely on single motility parameters or physiological indicators, Syntalos excels in its capacity to integrate multimodal data [

84]. Additionally, Syntalos supports the synchronized recording of high-resolution imaging and physiological signals, capturing subtle changes in sperm at different time points and revealing the dynamic processes underlying sperm functional characteristics [

84].

Figure 4.

4D Imaging of Sperm Cell Movement.

Figure 4.

4D Imaging of Sperm Cell Movement.

Pinto et al.’s research highlights the critical role of the CatSper channel, particularly CATSPER1, in regulating calcium ion influx within sperm cells—a process essential for sperm motility and male fertility. Traditional sperm motility assessment methods focus primarily on basic motility parameters and may fail to fully capture the comprehensive functional state of sperm. Incorporating the molecular understanding of CatSper channel function into the multimodal data integration strategy for sperm screening is anticipated to significantly enhance the accuracy of assessments [

85]. By linking molecular-level information on CATSPER1 expression with dynamic imaging data (e.g., flagellar oscillation patterns), researchers can develop predictive models that correlate specific gene expression with functional sperm characteristics [

86]. Dardikman-Yoffe et al. introduced a high-speed off-axis holographic system capable of performing high-resolution four-dimensional reconstruction of freely swimming human sperm cells without staining or mechanical components. Combining this 4D imaging data with complementary modalities such as Raman spectroscopy or metabolomics-based molecular profiles enables the development of cross-scale predictive models. These models connect molecular-level gene expression information with sperm functional traits, offering a deeper understanding of sperm motility [

79]. This multimodal data integration strategy, coupled with advancements in CASA systems, overcomes the limitations of conventional sperm motility assessment techniques [

88].

6.3. Evaluating the Integrity and Damage of Sperm DNA

In traditional sperm DNA integrity assessment, clinical practice primarily depends on endpoint detection techniques such as chromatin structure analysis, in situ DNA break detection, and comet assays [

88,

89,

90]. While these methods indicate the extent of DNA damage at a single time point, they have limitations, such as procedural complexity, subjective result interpretation, and standardization challenges [

81,

91]. Moreover, these methods involve significant sample destruction, are time-consuming, and cannot dynamically monitor damage progression [

92,

93].

The innovative integration of multimodal data is expected to overcome these limitations. With the emergence of deep learning, unprocessed sperm images can be utilized to train predictive models, potentially uncovering important features overlooked by humans and improving prediction accuracy [

94]. In a study by McCallum et al., a deep convolutional neural network was trained using approximately 1,000 human sperm cells with known DNA quality. This approach avoids destructive sperm processing and enables non-invasive DNA integrity assessment. The results demonstrated a moderate correlation (bivariate correlation coefficient of approximately 0.43) between sperm morphology images and DNA quality and could identify sperm cells with DNA integrity above the median [

95]. Popova et al.’s research revealed that structured illumination microscopy (SIM) can capture high-resolution images of live sperm cells at high resolution, particularly in the mitochondrial region of the midpiece, achieving spatial resolutions up to 100 nm. Non-invasive quantitative phase microscopy (QPM), combined with machine learning techniques, elucidated the association between oxidative stress-induced morphological changes in the sperm head and reduced motility. By applying deep neural networks to QPM images, the study achieved 85.6% accuracy in distinguishing healthy and damaged sperm. Furthermore, a systematic review indicated that sperm mitochondrial DNA copy number correlates with DNA quality. Collectively, these findings suggest that advanced imaging techniques such as SIM and QPM, combined with analyses of mitochondrial DNA copy number, can serve as valuable tools for assessing sperm DNA integrity [

96].

Micro-Raman spectroscopy, a non-invasive method, has been employed to detect sperm DNA damage [

97]. Du et al.’s research integrated micro-Raman spectroscopy with image analysis to simultaneously provide dynamic morphological and biochemical information. They developed a rapid Raman spectroscopy-based method that uses fine glass pipettes to adsorb samples onto a metal substrate, measuring Raman spectra at the pipette tip to evaluate DNA damage [

97]. Madan et al. reviewed the development and application of Transformer architectures in analysing diverse biomedical datasets, such as text data, protein sequences, structured longitudinal data, images, and graphs. Incorporating Transformer models into multimodal data strategies for sperm screening can effectively capture complex patterns across different data types, significantly enhancing analytical capabilities. Using the Transformer architecture to integrate genomic data (e.g., CATSPER1 gene expression) with dynamic imaging data (e.g., flagellar oscillation patterns) can more accurately predict sperm motility, DNA fragmentation index (DFI), and aneuploidy risk [

98].

6.4. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Technology

The “black box” problem is a central challenge in applying deep learning technology to medical contexts [

99]. Its core issue stems from the inherent conflict between the irreducible complexity of a model’s internal decision-making logic and the necessity for clinical verifiability [

100]. Within traditional deep learning frameworks, models abstract and integrate features from input data through multiple layers of nonlinear transformations, ultimately producing diagnostic outputs [

27]. However, this end-to-end mapping process lacks transparency, leading to two critical concerns: first, the discriminative features on which the model relies may diverge from established biological mechanisms [

101]. For instance, in sperm quality assessment, algorithms might erroneously classify microscopic imaging artifacts, such as slide scratches, as abnormalities in sperm head structure [

105]. Second, clinicians are unable to trace the decision-making rationale, making it challenging to verify whether the model’s judgments are based on appropriate biomarkers [

106]. In sperm multimodal screening, the “black box” problem is further compounded by data heterogeneity. When multi-source data, such as digital holographic microscopy and Raman spectroscopy, are simultaneously input into the model, the feature fusion process within hidden layers can lead to unintuitive weight distributions [

103].

Explainable artificial intelligence technology is expected to solve this problem. Suara et al. conducted a comprehensive study on interpretable deep learning principles, focusing particularly on the application of Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) in medical imaging. They demonstrated how Grad-CAM enhances the interpretability of deep learning models by highlighting critical regions within medical images that significantly influence model decision-making. By backpropagating gradients through the convolutional neural network, Grad-CAM generates spatial heat maps that correlate strongly with the model’s decisions, transforming the ’input-output’ black box into a visually interpretable ’feature-decision’ association [

104]. The integration of Grad-CAM into multimodal data strategies for sperm screening can substantially enhance the interpretability of predictive models [

105]. Through the application of Grad-CAM, clinicians gain a clearer understanding of which morphological features and molecular markers most significantly influence the model’s predictions regarding sperm quality parameters [

106]. Such an intuitively interpretable model enables direct validation of the artificial intelligence decision-making process, fostering greater trust and acceptance of AI-assisted diagnosis in reproductive medicine [

107] [

108].

7. Challenges and Breakthrough Paths in the Medical Application of Multi-modal Data Fusion

The clinical application of multimodal data fusion faces significant challenges due to the interplay between technical limitations and biological complexity [

109,

110,

111]. The primary hurdle originates from the spatiotemporal asynchrony and semantic gap inherent in heterogeneous data sources [

112,

113]. Specifically, the millisecond temporal resolution of dynamic imaging contrasts sharply with the static nature of genomics data, creating a parsing scale discontinuity. Moreover, the nonlinear relationships between microscopic phenotypic features and metabolic molecular markers far exceed the characterization capabilities of traditional feature engineering approaches [

114,

115,

116]. Additionally, the challenge of balancing information redundancy and complementarity across modalities limits model generalization. For example, in neurological disease diagnosis, the brain network topology derived from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electrophysiological oscillation signals exhibit both synergistic verification and potential interference [

117,

118]. A deeper challenge lies in overcoming the barrier to biological interpretability. Current black-box fusion mechanisms struggle to trace the causal chains underlying cross-modal associations, raising concerns about the credibility of clinical decision support systems [

119,

120,

121].

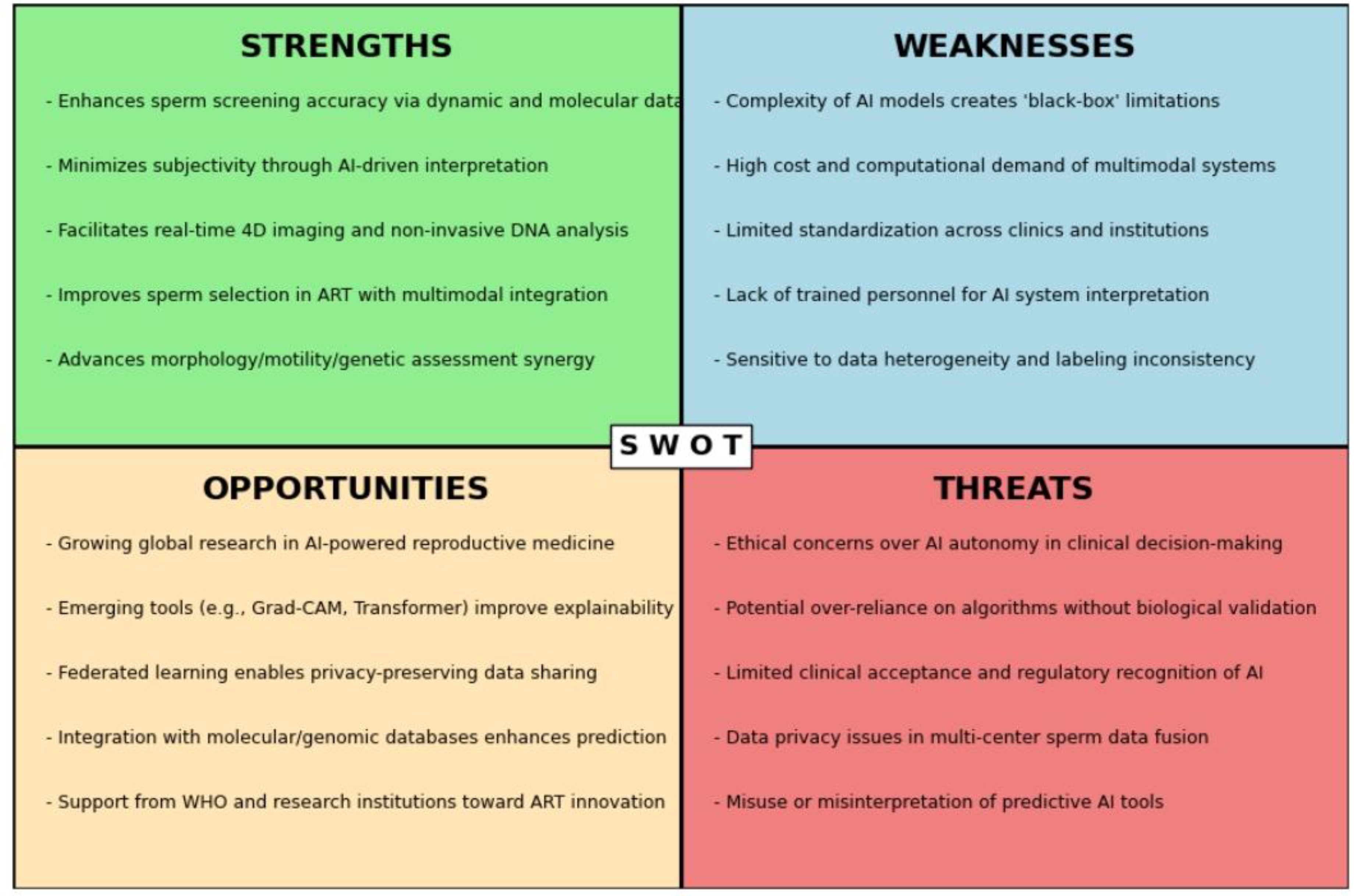

Figure 5.

SWOT analysis of multimodal artificial intelligence applications in sperm screening and assisted reproductive technologies.

Figure 5.

SWOT analysis of multimodal artificial intelligence applications in sperm screening and assisted reproductive technologies.

Frontier research is exploring multiple pathways to address these challenges. Adaptive hierarchical fusion architectures leverage gating mechanisms to dynamically weight the contributions of different modalities, suppressing noise propagation while preserving modality-specific characteristics [

122,

123]. Knowledge distillation techniques compress large multimodal models into lightweight clinical reasoning engines, mitigating the tension between computational constraints and real-time performance requirements [

124,

125]. Distributed multi-center data collaboration under the federated learning framework aims to resolve the trade-off between privacy protection and model generalization [

126]. Notably, the introduction of causal representation learning offers a promising approach by simulating counterfactual interventions to uncover the driving relationships between imaging feature variations and molecular pathway abnormalities, providing a novel paradigm for constructing interpretable fusion decision systems [

127,

128]. The co-evolution of these technologies is propelling multimodal fusion toward a substantive transition from laboratory validation to routine clinical application [

129].

8. Conclusions

In the provided document, the application of multimodal AI in sperm screening within ART is comprehensively discussed. The study emphasizes overcoming the limitations of traditional sperm selection methods, which primarily rely on static morphological parameters and subjective assessments. Multimodal AI incorporates diverse data, including dynamic imaging, genomic profiles, biochemical markers, and clinical parameters, enhancing the accuracy of sperm motility assessments and optimizing metabolic function evaluations.

Key advancements highlighted include the integration of sophisticated AI models—such as machine learning, deep learning, and multimodal fusion techniques—to systematically assess sperm quality in multiple dimensions. These innovative approaches enable precise evaluations of sperm morphology, dynamic motility, and genetic integrity simultaneously, significantly improving clinical outcomes in ART.

However, the clinical application of multimodal AI faces several challenges. Issues such as data heterogeneity, model interpretability, biological complexity, and clinical translation barriers remain critical hurdles. Addressing these concerns requires advanced data fusion strategies, adaptive hierarchical modelling, and explainable artificial intelligence methods to facilitate clinical validation and acceptance. Overall, the study underscores the transformative potential of multimodal AI for reproductive medicine, providing a clear path forward by highlighting current technological opportunities and outlining strategic approaches to address ongoing challenges.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the teachers from the School of Health Science of the University of New South Wales for their guidance, which enabled me to complete the interdisciplinary research.

Conflicts of Interest

the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Inhorn, Marcia C., and Pasquale Patrizio. Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Human reproduction update 2015, 21, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zegers-Hochschild, Fernando; et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Human reproduction 2017, 32, 1786–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Oseguera-López, Iván; et al. Novel techniques of sperm selection for improving IVF and ICSI outcomes. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2019, 7, 298. [Google Scholar]

- Yániz, J. L., C. Soler, and P. Santolaria. Computer assisted sperm morphometry in mammals: a review. Animal reproduction science 2015, 156, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xieling; et al. Artificial intelligence and multimodal data fusion for smart healthcare: topic modeling and bibliometrics. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Junwei; et al. Deep learning based multimodal biomedical data fusion: An overview and comparative review. Information Fusion 2024, 102536. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsen, Farida; et al. Artificial intelligence-based methods for fusion of electronic health records and imaging data. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 17981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSaad, Rawan; et al. Multimodal large language models in health care: applications, challenges, and future outlook. Journal of medical Internet research 2024, 26, e59505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Junwei; et al. Challenges in AI-driven Biomedical Multimodal Data Fusion and Analysis. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2025, qzaf011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Qing, Xiaowen Liang, and Zhiyi Chen. A review of artificial intelligence applications in in vitro fertilization. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 2025, 42, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medenica, Sanja; et al. The future is coming: artificial intelligence in the treatment of infertility could improve assisted reproduction outcomes—the value of regulatory frameworks. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, Vaidyeswaran. JohnMcCarthy—Father of artificial intelligence. Resonance 2014, 19, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negnevitsky, Michael. The History Of Artificial Intelligence Or From The. WIT Transactions on Information and Communication Technologies 2024, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, Dilli Hang. Artificial Intelligence Through Time: A Comprehensive Historical Review. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anurag, A. S. Early beginnings of AI: the field of research in computer science. Cases on AI Ethics in Business. IGI Global 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Al Kuwaiti, Ahmed; et al. A review of the role of artificial intelligence in healthcare. Journal of personalized medicine 2023, 13, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Khalid, Sabitha Krishnan, and Rohit M. Thanki. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer early detection and diagnosis; Springer: Cham.

- Xie, Yi; et al. Integration of artificial intelligence, blockchain, and wearable technology for chronic disease management: a new paradigm in smart healthcare. Current medical science 2021, 41, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar Nia, Nafiseh, Erkan Kaplanoglu, and Ahad Nasab. Evaluation of artificial intelligence techniques in disease diagnosis and prediction. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2023, 3, 5.

- Sarkar, Chayna; et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning technology driven modern drug discovery and development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 2026.

- Pinto-Coelho, Luís. How artificial intelligence is shaping medical imaging technology: a survey of innovations and applications. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1435.

- Gedefaw, Lealem; et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted diagnostic cytology and genomic testing for hematologic disorders. Cells 2023, 12, 1755.

- Liu, Jiazheng; et al. A robust transformer-based pipeline of 3D cell alignment, denoise and instance segmentation on electron microscopy sequence images. Journal of Plant Physiology 2024, 297, 154236.

- Dai, Changsheng; et al. Advances in sperm analysis: techniques, discoveries and applications. Nature Reviews Urology 2021, 18, 447–467.

- Kamieniczna, Marzena; et al. Human live spermatozoa morphology assessment using digital holographic microscopy. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 4846.

- Kang, Mi-Sun; et al. Accuracy improvement of quantification information using super-resolution with convolutional neural network for microscopy images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2020, 58, 101846.

- Duan, Junwei; et al. Deep learning based multimodal biomedical data fusion: An overview and comparative review. Information Fusion (2024): 102536.

- Hussain, Dildar; et al. Revolutionizing tumor detection and classification in multimodality imaging based on deep learning approaches: Methods, applications and limitations. Journal of X-Ray Science and Technology 2024, 32, 857–911.

- Gou, Fangfang; et al. Research on artificial-intelligence-assisted medicine: a survey on medical artificial intelligence. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1472.

- Dai, Wei; et al. Automated Non-Invasive Analysis of Motile Sperms Using Sperm Feature-Correlated Network. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering (2024).

- Lee, Ryan; et al. Automated rare sperm identification from low-magnification microscopy images of dissociated microsurgical testicular sperm extraction samples using deep learning. Fertility and Sterility 2022, 118, 90–99.

- Abou Ghayda, Ramy; et al. Artificial intelligence in andrology: from semen analysis to image diagnostics. The World Journal of Men’s Health 2023, 42, 39.

- Ignatieva, Elena V. ; et al. A catalog of human genes associated with pathozoospermia and functional characteristics of these genes. Frontiers in genetics 2021, 12, 662770.

- Botezatu, A.; et al. Advanced molecular approaches in male infertility diagnosis. Biology of Reproduction 2022, 107, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Saurabh, Praveen Kumar Mannepalli, and Harshita Chourasia. Exploring Cutting-Edge Deep Learning Techniques in Image Processing. 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Quantum Computation-Based Sensor Application (ICAIQSA). IEEE, 2024.

- Swamy, Samatha R., and KS Nandini Prasad. Revolutionizing healthcare intelligence multisensory data fusion with cutting-edge machine learning and deep learning for patients’ cognitive knowledge. 2024 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS). Vol. 1. IEEE, 2024.

- Wang, Xu-Wen, Tong Wang, and Yang-Yu Liu. Artificial Intelligence for Microbiology and Microbiome Research. arXiv arXiv:2411.01098, 2024.

- Wang, Guangyu; et al. A generalized AI system for human embryo selection covering the entire IVF cycle via multi-modal contrastive learning. Patterns 2024, 5.

- Liu, Mark; et al. WISE: whole-scenario embryo identification using self-supervised learning encoder in IVF. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 2024, 41, 967–978.

- Zhang, Chongming; et al. Sperm YOLOv8E-TrackEVD: A Novel Approach for Sperm Detection and Tracking. Sensors 2024, 24, 3493.

- Kresch, Eliyahu; et al. Novel methods to enhance surgical sperm retrieval: a systematic review. Arab Journal of Urology 2021, 19, 227–237.

- Fan, Keqiang. Machine learning techniques for medical image analysis with data scarcity. Diss. University of Southampton, 2025.

- Galić, Irena; et al. Machine learning empowering personalized medicine: A comprehensive review of medical image analysis methods. Electronics 2023, 12, 4411.

- Baltrušaitis, Tadas, Chaitanya Ahuja, and Louis-Philippe Morency. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 41, 423–443.

-

Wu, Biao; et al. Xlip: Cross-modal attention masked modelling for medical language-image pre-training. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.

-

Chen, Jintai; et al. Trialbench: Multi-modal artificial intelligence-ready clinical trial datasets. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.

- Yang, Jucheng, and Fushun Ren. Drug–Target Affinity Prediction Based on Cross-Modal Fusion of Text and Graph. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2901.

-

Lu, Haoyu; et al. Uniadapter: Unified parameter-efficient transfer learning for cross-modal modeling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.

- Ye, Yiwen; et al. Continual self-supervised learning: Towards universal multi-modal medical data representation learning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2024.

- Liu, Qijiong; et al. Multimodal pretraining, adaptation, and generation for recommendation: A survey. Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 2024.

- Chen, Cheng; et al. Unsupervised bidirectional cross-modality adaptation via deeply synergistic image and feature alignment for medical image segmentation. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2020, 39, 2494–2505.

- Li, Xiangyun; et al. Machine Learning-Based Pathomics Model to Predict the Prognosis in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment 2024, 23, 15330338241307686.

- Lai, Qi; et al. Hybrid multiple instance learning network for weakly supervised medical image classification and localization. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 260, 125362.

- Ren, Zeyu, Shuihua Wang, and Yudong Zhang. Weakly supervised machine learning. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology 2023, 8, 549–580.

- Koteluk, Oliwia; et al. How do machines learn? artificial intelligence as a new era in medicine. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2021, 11, 32.

- Wang, Yang. Survey on deep multi-modal data analytics: Collaboration, rivalry, and fusion. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM) 17.1s (2021): 1-25.

- Yao, Weiheng, and Shuqiang Wang. CATD: Unified Representation Learning for EEG-to-fMRI Cross-Modal Generation. 2024; arXiv:2408.00777.

- Zeng, Xiangxiang; et al. Deep generative molecular design reshapes drug discovery. Cell Reports Medicine 2022, 3.

- Born, Jannis, and Matteo Manica. Trends in deep learning for property-driven drug design. Current medicinal chemistry 2021, 28, 7862–7886.

- Weng, Wei-Hung. Learning Representations for Limited and Heterogeneous Medical Data. Diss. Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2022.

-

Sun, Kai; et al. Medical Multimodal Foundation Models in Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment: Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.

- Chen, Yanbei; et al. Semi-supervised and unsupervised deep visual learning: A survey. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2022, 46, 1327–1347.

- Sun, Ya, Sijie Mai, and Haifeng Hu. Learning to learn better unimodal representations via adaptive multimodal meta-learning. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 14, 2209–2223.

- Chudasama, Yashrajsinh; et al. Towards Interpretable Hybrid AI: Integrating Knowledge Graphs and Symbolic Reasoning in Medicine. IEEE Access 2025.

- Zou, Xingchen; et al. Deep learning for cross-domain data fusion in urban computing: Taxonomy, advances, and outlook. Information Fusion 2025, 113, 102606.

- Gao, Bin; et al. An Explainable Unified Framework of Spatio-Temporal Coupling Learning with Application to Dynamic Brain Functional Connectivity Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2024.

-

Deldari, Shohreh; et al. Beyond just vision: A review on self-supervised representation learning on multimodal and temporal data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.

- Dimitri, Giovanna Maria; et al. Multimodal and multicontrast image fusion via deep genrative models. Information Fusion 2022, 88, 146–160.

- Hu, Wenxing; et al. Interpretable multimodal fusion networks reveal mechanisms of brain cognition. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2021, 40, 1474–1483.

- Fernández-López, Pol; et al. Predicting fertility from sperm motility landscapes. Communications biology 2022, 5, 1027.

- Tanga, Bereket Molla; et al. Semen evaluation: Methodological advancements in sperm quality-specific fertility assessment—A review. Animal bioscience 2021, 34, 1253.

- Komatsu, Kouji; et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential in 2-cell stage embryos correlates with the success of preimplantation development. Reproduction 2014, 147, 627–638.

- Zhao, Na; et al. Mfn2 affects embryo development via mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. PloS one 2015, 10, e0125680.

- Zenoaga-Barbǎroşie, Cătălina, and Marlon Martinez. Sperm Morphology. Human Semen Analysis: From the WHO Manual to the Clinical Management of Infertile Men (2024): 135.

- Gatimel, N.; et al. Sperm morphology: assessment, pathophysiology, clinical relevance, and state of the art in 2017. Andrology 2017, 5, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewska, Anna Justyna; et al. The Influence of Cryopreservation on Sperm Morphology and Its Implications in Terms of Fractions of Higher-Quality Sperm. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 7562.

- Nygate, Yoav N. ; et al. Holographic virtual staining of individual biological cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 9223–9231.

- Zou, Shuojia; et al. TOD-CNN: An effective convolutional neural network for tiny object detection in sperm videos. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 146, 105543.

- Dardikman-Yoffe, Gili; et al. High-resolution 4-D acquisition of freely swimming human sperm cells without staining. Science advances 2020, 6, eaay7619.

- Gongora, A. A New Perspective on Sperm Analysis Through Artificial Intelligence: The Path Toward Personalized Reproductive Medicine. Ann Clin Med Case Rep 2025, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- You, Jae Bem; et al. Machine learning for sperm selection. Nature Reviews Urology 2021, 18, 387–403.

- O’meara, Ciara; et al. The effect of adjusting settings within a Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA) system on bovine sperm motility and morphology results. Animal Reproduction 2022, 19, e20210077.

- Dias, Tania R., Chak-Lam Cho, and Ashok Agarwal. Sperm assessment: Traditional approaches and their indicative value. In vitro fertilization: A textbook of current and emerging methods and devices (2019): 249-263.

- Klumpp, Matthias; et al. Syntalos: a software for precise synchronization of simultaneous multi-modal data acquisition and closed-loop interventions. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 708.

- Pinto, Francisco M. ; et al. The role of sperm membrane potential and ion channels in regulating sperm function. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 6995.

- Amini Mahabadi, Javad; et al. The Use of Machine Learning for Human Sperm and Oocyte Selection and Success Rate in IVF Methods. Andrologia 2024, 2024, 8165541.

- Abou Ghayda, Ramy; et al. Artificial intelligence in andrology: from semen analysis to image diagnostics. The World Journal of Men’s Health 2023, 42, 39.

- Esteves, Sandro C. ; et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation testing: Summary evidence and clinical practice recommendations. Andrologia 2021, 53, e13874.

- Agarwal, Ashok, and Rakesh Sharma. Sperm chromatin assessment. Textbook of assisted reproductive techniques. CRC Press, 2023. 70-93.

- Marinaro, Jessica A. , and Peter N. Schlegel. Sperm DNA damage and its relevance in fertility treatment: a review of recent literature and current practice guidelines. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 1446.

- Tvrdá, Eva; et al. Dynamic assessment of human sperm DNA damage III: The effect of sperm freezing techniques. Cell and Tissue Banking 2021, 22, 379–387.

- Diaz, Parris; et al. Future of male infertility evaluation and treatment: brief review of emerging technology. Urology 2022, 169, 9–16.

- Li, Philip S., and Ranjith Ramasamy. Future of Male Infertility Evaluation and Treatment: Brief Review of Emerging Technology. (2022).

- Esteva, Andre; et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nature medicine 2019, 25, 24–29.

- McCallum, Christopher; et al. Deep learning-based selection of human sperm with high DNA integrity. Communications biology 2019, 2, 250.

- Popova, Daria. Advanced methods in reproductive medicine: Application of optical nanoscopy, artificial intelligence-assisted quantitative phase microscopy and mitochondrial DNA copy numbers to assess human sperm cells. (2021).

- Du, Shengrong; et al. Micro-Raman analysis of sperm cells on glass slide: potential label-free assessment of sperm DNA toward clinical applications. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1051.

- Madan, Sumit; et al. Transformer models in biomedicine. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2024, 24, 214.

- Murad, Nafeesa Yousuf; et al. Unraveling the black box: A review of explainable deep learning healthcare techniques. IEEE Access (2024).

- Ali, Sajid; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Information fusion 2023, 99, 101805.

- Perry, Joseph. Streamlining the image capture and analysis for high throughput unbiased quantitation and categorization of nuclear morphology. Diss. University of Essex, 2024.

- Datta Burton, Saheli; et al. Clinical translation of computational brain models: Understanding the salience of trust in clinician–researcher relationships. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 46.1- 2021, 2, 138–157.

- Ruppli, Camille. Methods and frameworks of annotation cost optimization for deep learning algorithms applied to medical imaging. Diss. Institut Polytechnique de Paris, 2023.

-

Suara, Subhashis; et al. Is grad-cam explainable in medical images?. International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Processing. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023.

- Nazir, Asifa; et al. A novel approach in cancer diagnosis: integrating holography microscopic medical imaging and deep learning techniques—challenges and future trends. Biomedical Physics & Engineering Express 2025, 11, 022002.

- Isa, Iza Sazanita, Umi Kalsom Yusof, and Murizah Mohd Zain. Image Processing Approach for Grading IVF Blastocyst: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Perspective of Deep Learning-Based Models. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1195.

- Bagheri, Maryam; et al. AI-driven decision-making in healthcare information systems: a comprehensive review. Preprints (2024).

- Luong, Thi-My-Trang, and Nguyen Quoc Khanh Le. Artificial intelligence in time-lapse system: advances, applications, and future perspectives in reproductive medicine. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2024, 41, 239–252.

- Lilhore, Umesh Kumar, et al., eds. Multimodal Data Fusion for Bioinformatics Artificial Intelligence. John Wiley & Sons, 2025.

- Kaur, Simranjit; et al. Precision medicine with data-driven approaches: A framework for clinical translation. AIJMR-Advanced International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 2024, 2.

- Bai, Long; et al. AI-enabled organoids: construction, analysis, and application. Bioactive materials 2024, 31, 525–548.

- Putrama, I. Made, and Péter Martinek. Heterogeneous data integration: Challenges and opportunities. Data in Brief 2024, 110853.

- Li, Jian; et al. Image Encoding and Fusion of Multi-modal Data Enhance Depression Diagnosis in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2024.

- Lürig, Moritz D. ; et al. Computer vision, machine learning, and the promise of phenomics in ecology and evolutionary biology. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 9, 642774.

- Chakraborty, Sohini; et al. Multi-OMICS approaches in cancer biology: New era in cancer therapy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2024, 1870, 167120.

- Huan, Changxiang; et al. Spatially Resolved Multiomics: Data Analysis from Monoomics to Multiomics. BME frontiers 2025, 6, 0084.

- Liu, Jinyuan; et al. Coconet: Coupled contrastive learning network with multi-level feature ensemble for multi-modality image fusion. International Journal of Computer Vision 2024, 132, 1748–1775.

- Tan, Bo; et al. Aberrant whole-brain resting-state functional connectivity architecture in obsessive-compulsive disorder: an EEG study. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2022, 30, 1887–1897.

- Wysocka, Magdalena; et al. A systematic review of biologically-informed deep learning models for cancer: fundamental trends for encoding and interpreting oncology data. BMC bioinformatics 2023, 24, 198.

-

Sun, Shilin; et al. A review of multimodal explainable artificial intelligence: Past, present and future. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.

- Joshi, Gargi, Rahee Walambe, and Ketan Kotecha. A review on explainability in multimodal deep neural nets. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59800–59821.

- Dong, Aimei; et al. Co-Enhancement of Multi-Modality Image Fusion and Object Detection via Feature Adaptation. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology (2024).

- Zhang, Qingyang; et al. Multimodal fusion on low-quality data: A comprehensive survey. arXiv:2404.18947 (2024).

- Friha, Othmane; et al. Llm-based edge intelligence: A comprehensive survey on architectures, applications, security and trustworthiness. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society (2024).

- Bai, Guangji; et al. Beyond efficiency: A systematic survey of resource-efficient large language models. arXiv:2401.00625 (2024).

- Rauniyar, Ashish; et al. Federated learning for medical applications: A taxonomy, current trends, challenges, and future research directions. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 11, 7374–7398.

- Jiao, Licheng; et al. Causal inference meets deep learning: A comprehensive survey. Research 2024, 7, 0467.

- Jing, Yankang. Machine/Deep Learning Causal Pharmaco-Analytics for Preclinical System Pharmacology Modeling and Clinical Outcomes Analytics. Diss. University of Pittsburgh, 2021.

- Xu, Xi; et al. A comprehensive review on synergy of multi-modal data and ai technologies in medical diagnosis. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 219.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).