1. Introduction

Acute heart failure (AHF) is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome associated with high mortality rates and frequent hospital readmissions, assuming a significant burden on healthcare systems both medically and economically [

1,

2]. One of its defining characteristics is volume overload combined with systemic inflammation, wherein soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 (sST2) serves as a crucial indicator of inflammatory and fibrotic processes [

3]. Elevated plasma levels of sST2 in AHF patients have been closely linked to increased disease severity, poor diuretic response, and a heightened risk of cardiovascular mortality [

4].

Beyond sST2, antigen carbohydrate 125 (CA125), also known as mucin 16 (MUC16), has emerged as another promising biomarker in AHF, particularly in reflecting volume overload and inflammation [

5]. Recent research suggests that CA125 may play a causal role as a ligand, actively modulating inflammatory responses through interactions with various molecular targets. Notably, CA125 has been identified as a binding partner for soluble lectins, such as galectin-1 (Gal-1) and Gal-3 [

6]. These interactions with glycosylated proteins are known to influence the biological activity of galectins. In the context of AHF, previous studies have shown that the prognostic impact of Gal-3 is modulated by CA125 levels. Specifically, elevated Gal-3 is linked to worse outcomes in patients with high CA125 concentration, whereas this association is not observed in those with lower CA125 levels, highlighting a potential interplay between these biomarkers [

7].

Structurally, MUC16 has a highly glycosylated extracellular domain that enables interactions with other proteins, allowing it to function as a modulator in various biological processes [

6]. Similarly, sST2 contains an immunoglobulin-like domain in its extracellular region, conferring structural flexibility that may facilitate interactions with proteins beyond its native interleukin-33 (IL-33) receptor [

8]. Along this line of thought, we recently found an interaction between CA125 and sST2 in a small sample of patients with AHF and renal dysfunction [

9]. Specifically, elevated sST2 was significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular (CV)-renal hospitalizations only in patients with CA125 >35 U/mL but not when CA125 was ≤35 U/ml. However, this prior observation was restricted to a selected population with kidney dysfunction on admission. Additionally, the small sample size precluded to obtain robust estimates in terms of mortality risk.

In the current study, we wanted to confirm whether the prognostic interaction found between CA125 and sST2 is also replicated in a larger, non-selected sample of patients with decompensated heart failure in emergency room. Thus, we aimed to examine the association between sST2 and long-term adverse clinical outcomes (mortality and heart failure (HF)-hospitalizations) across CA125 status.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

We analyzed data from 635 consecutive patients with AHF included in the Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Spanish Emergency Departments (EAHFE) registry, in which sST2 and CA125 levels were measured. The EAHFE registry is a multicenter, non-interventional, analytical cohort study with a prospective follow-up [

10,

11]. It includes patients diagnosed with AHF who were enrolled across multiple Spanish hospital emergency departments (EDs). The registry systematically collects comprehensive data on clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, therapeutic interventions, and outcomes in AHF patients. To date, the EAHFE registry has completed eight phases of patient inclusion. For the present study, cases were randomly selected.

The participating hospitals are distributed throughout Spain and include a diverse mix of university, referral, and community hospitals. The EDs consistently enroll all consecutive patients treated for AHF. The diagnostic criteria for AHF are based on the presence of typical symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea), acute clinical signs of AHF (e.g., third heart sound, pulmonary crackles, jugular venous distension >4 cm, resting sinus tachycardia, peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, or hepatojugular reflux), and radiological evidence of pulmonary congestion. The only exclusion criterion is the presence of ST-elevation myocardial infarction as the primary diagnosis with associated AHF. At each hospital, a training meeting was held to standardize inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any doubts were reviewed by the principal investigator of each center. This protocol has been applied consistently across all eight recruitment phases of the registry, with minimal changes to the collected variables.

The EAHFE registry adheres to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in the registry. The study protocol was approved by the ethics and clinical research committees of all participating hospitals.

2.2. Biomarkers Assessment

Plasma samples were collected in the first blood sample obtained at the ED of the participating hospitals, upon patient arrival. All samples were collected in lithium heparin tubes, processed and stored at -20ºC until analysis. CA125 and sST2 biomarkers were processed at the Clinical Biochemistry and Molecular Pathology Laboratory of the University Clinical Hospital of Valencia.

The commercially available assays used were microparticle chemiluminescent immunoassay Alinity-i CA 125 II (Abbott®) and turbidimetric immunoassay SEQUENT-IATM ST2 (Critical Diagnosis®), adapted for the Alinity-c analyzer (Abbott®). The mean values of the quality control for CA125 were: Level 1= 22 U/mL; Level 2= 37 U/mL and Level 3= 74 U/mL, while for sST2, they were: Level 1= 18 ng/mL and Level 2= 54 ng/mL. The total variation coefficients for each assay, as indicated by the manufacturers, were 4.2%, 3.7%, 2.7% for the low (39.3 U/mL), medium (271.2 U/mL) and high (570.7 U/mL) concentrations of CA125 and 8.6%, 3.8%, and 2.2% for the low (25.7 ng/mL), medium (75.4 ng/mL) and high (160.6 ng/mL) concentrations of sST2 respectively. Both biomarkers were categorized based on established cut-off values reported in the literature (35 U/mL and ng/mL, respectively).

2.3. Endpoints

In the current analysis, we aimed to assess the relationship between the exposures and: a) time to all-cause death, and b) the combined time to death or new HF-admission (excluding the index episode).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] when appropriate. sST2 and CA125 were categorized based on established threshold levels (sST2: ≤35 vs. >35 ng/mL and CA125: ≤35 vs. >35 U/mL). Group differences for sST2 and CA125 were analyzed with ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis rank test, as appropriate. Discrete variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the χ2 test. Correlation between CA125 and sST2 were assessed by Spearman correlation index. Mortality and new HF admissions rates were reported as the number of events per 10 person-years (P-Y). The associations between the exposures (CA125 and sST2) and adverse clinical events were examined by multivariate Cox regression analyses. Specifically, we assessed whether the risk of sST2 along the continuum was statistically modified by CA125 strata (>35 U/mL vs ≤35 U/mL).

The final models for the endpoints included the following covariates: age, sex, prior New York Heart Association (NYHA) class under stable conditions, history of HF, history of ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation at admission, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, Barthel index score, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, third heart sound, jugular venous distension, pleural effusion, peripheral edema, hemoglobin, and creatinine levels. We performed as a sensitivity analysis adjusting for MEESSI risk score when was available (n=406 patients). This score provides and accurate risk stratification in patients with AHF in EDs [

12]. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.1 [Stata Statistical Software, Release 16 (2019); StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The baseline and biomarker characteristics of the total cohort are detailed in

Table 1. The mean±SD age of the sample was 82.4±10 years, and 339 (53.4%) were women. Most of patients showed prior history of hypertension (84.1%) and prior history of HF (63.1%). At presentation, the proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation was 49.9% and most of them showed clinical data of volume overload (

Table 1). The median (p25% to p75%) creatinine, hemoglobin and NT-proBNP were 1.2 mg/dL (0.9–1.6), 12 g/dL (10.6-13.4), 4207 pg/mL (2280–8421), respectively. Regarding the exposures, the median (p25% to p75%) of CA125 and sST2 were 44 U/mL (19.0–94.0), and 49.2 ng/mL (27.3–88.5), respectively. The proportion of patients with CA125 and sST2 values above 35 was 57.3% and 67.2%, respectively (

Table 1). Spearman correlation coefficient showed CA125 and sST2 were weak and positively correlated (r=0.237, p<0.001).

3.2. Baseline Characteristics Across CA125 and sST2 Categories

Among the 284 patients (44.7%) with elevated levels of both CA125 (>35 U/mL) and sST2 (>35 ng/mL), there was a higher prevalence of women, and had lower systolic blood pressure. They exhibited significantly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and higher levels of NT-proBNP. This group also had a higher prevalence of pleural effusion and poorer functional status, as indicated by lower Barthel Index scores compared to other groups. In summary, patients with both biomarkers elevated displayed a worse risk profile (

Table 2).

3.3. Adverse Clinical Events

At a median (p25% to p75%) follow-up of 380 days (126 to 456), we registered 216 (34.0%) all-cause deaths, and 152 (23.9%) new HF-admissions. The total of patients that experienced the combined endpoint of death or new HF admission was 295 (46.5%). The annualized rates of death and the combined of death or new HF admissions were 3.9 (CI 95%: 3.5 to 4.5) and 6.6 (CI 95%: 5.9 to 7.4) per 10- P-Y, respectively.

3.4. Relationship Between CA125 and sST2 as Main Terms with Adverse Clinical Events

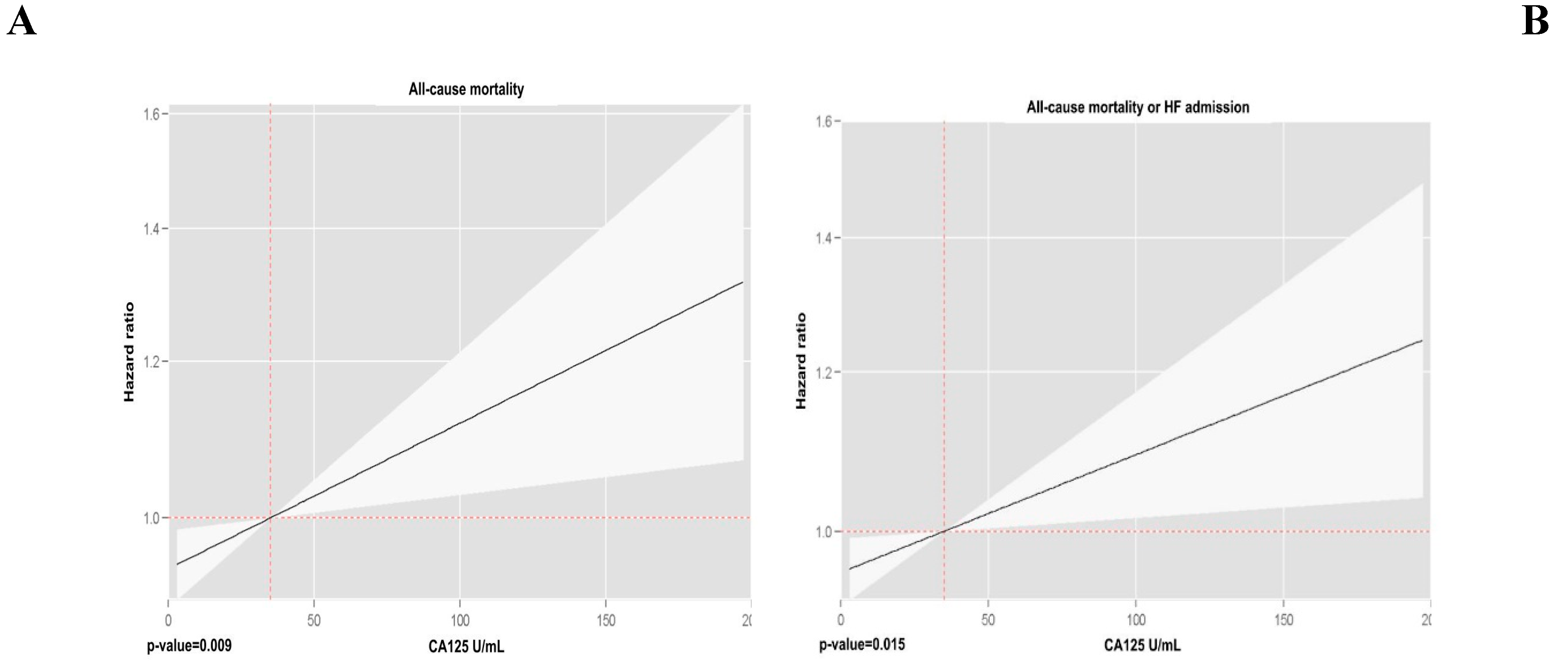

Multivariate analyses, incorporating both biomarkers into the model, revealed that CA125 and sST2 were independently associated with both endpoints. The risk pattern for CA125 followed a positive and linear trend (

Figure 1), while for sST2, the relationship was also positive but exhibited a slightly nonlinear behavior (

Figure 2). Multivariate analyses, incorporating both biomarkers into the model, revealed that CA125 and sST2 were independently associated with both endpoints. The risk pattern for CA125 followed a positive and linear trend (

Figure 1), while for sST2, the relationship was also positive but exhibited a slightly nonlinear behavior (

Figure 2).

3.5. The Modifying Prognostic Role of sST2 Across CA125

3.5.1. All Cause-Mortality

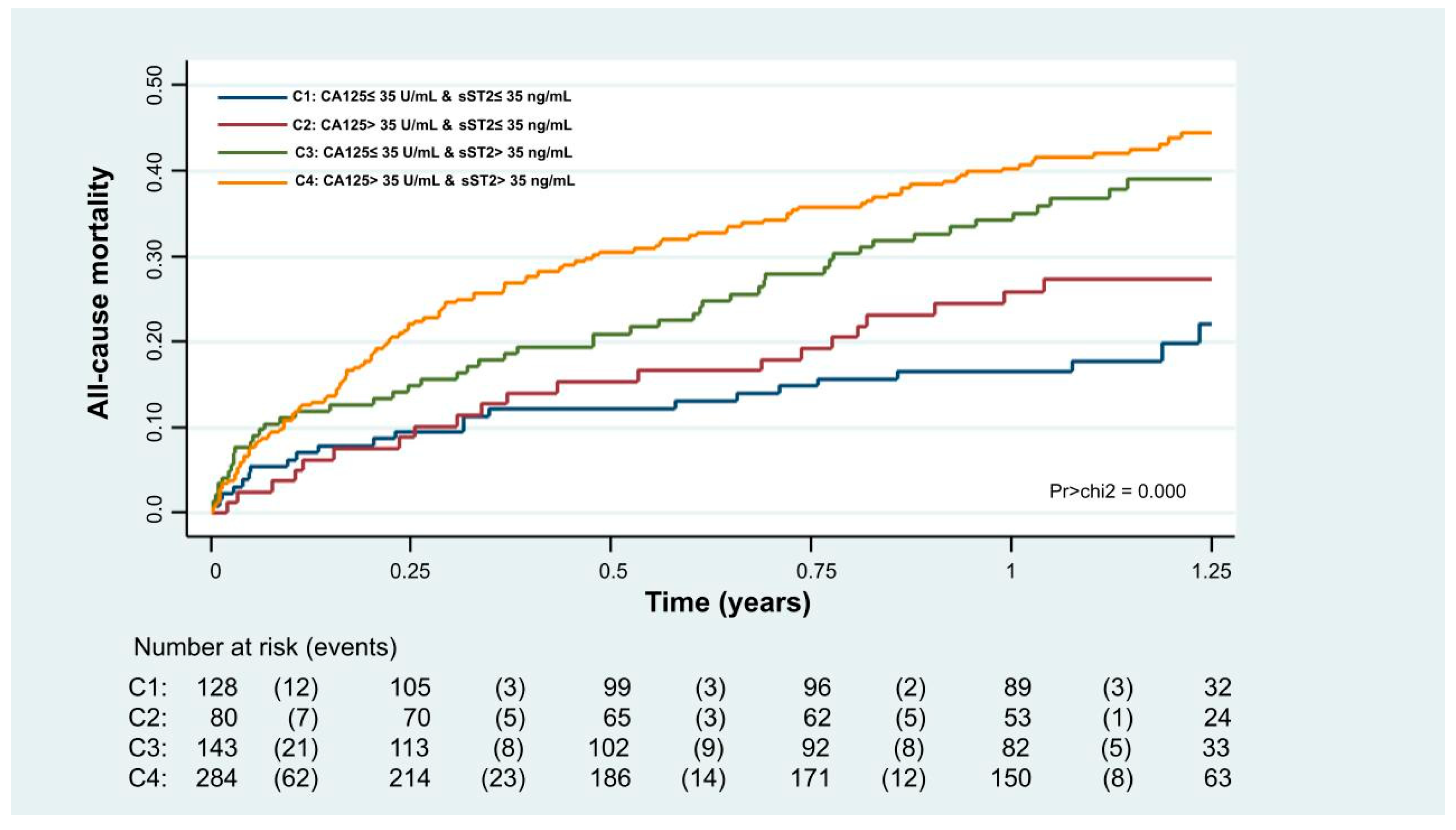

Kaplan-Meier analyses revealed that combining both biomarkers (CA125>35 U/mL and sST2>35 ng/mL) allowed for a more refined risk stratification. Patients with both biomarkers below the threshold had the lowest mortality risk through the follow-up, those with one elevated biomarker had an intermediate risk, and those with elevated biomarkers had the highest risk (

Figure 3, p<0.001).

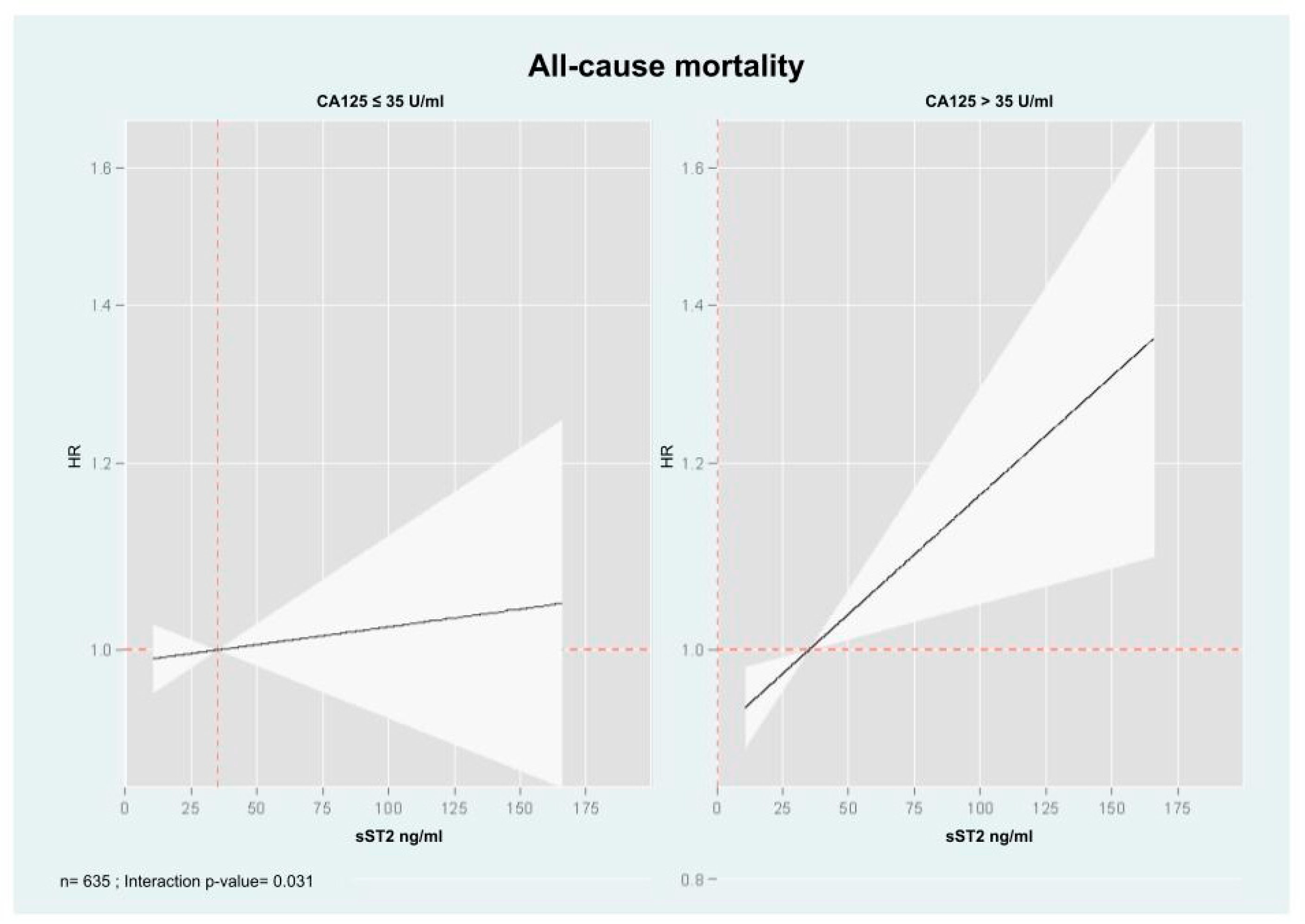

Multivariate analyses examining the association of sST2 with mortality across CA125 status (≤35 U/mL vs >35 U/mL) revealed a significant interaction (interaction p-value=0.031). In patients with CA125>35 U/mL, sST2 (along their continuum) were positive and linearly associated with mortality risk (

Figure 4). Indeed, the HRs [95% CI, (p-value)] per increase in 10 ng/mL of sST2 were 1.02 (CI 95%: 1.01 to 1.04, p=0.006). At the opposite, in individuals with CA125≤35 U/mL, sST2 was not related to the risk of death (HR: 1.00, CI 95%: 0.99 to 1.02, p=0.619).

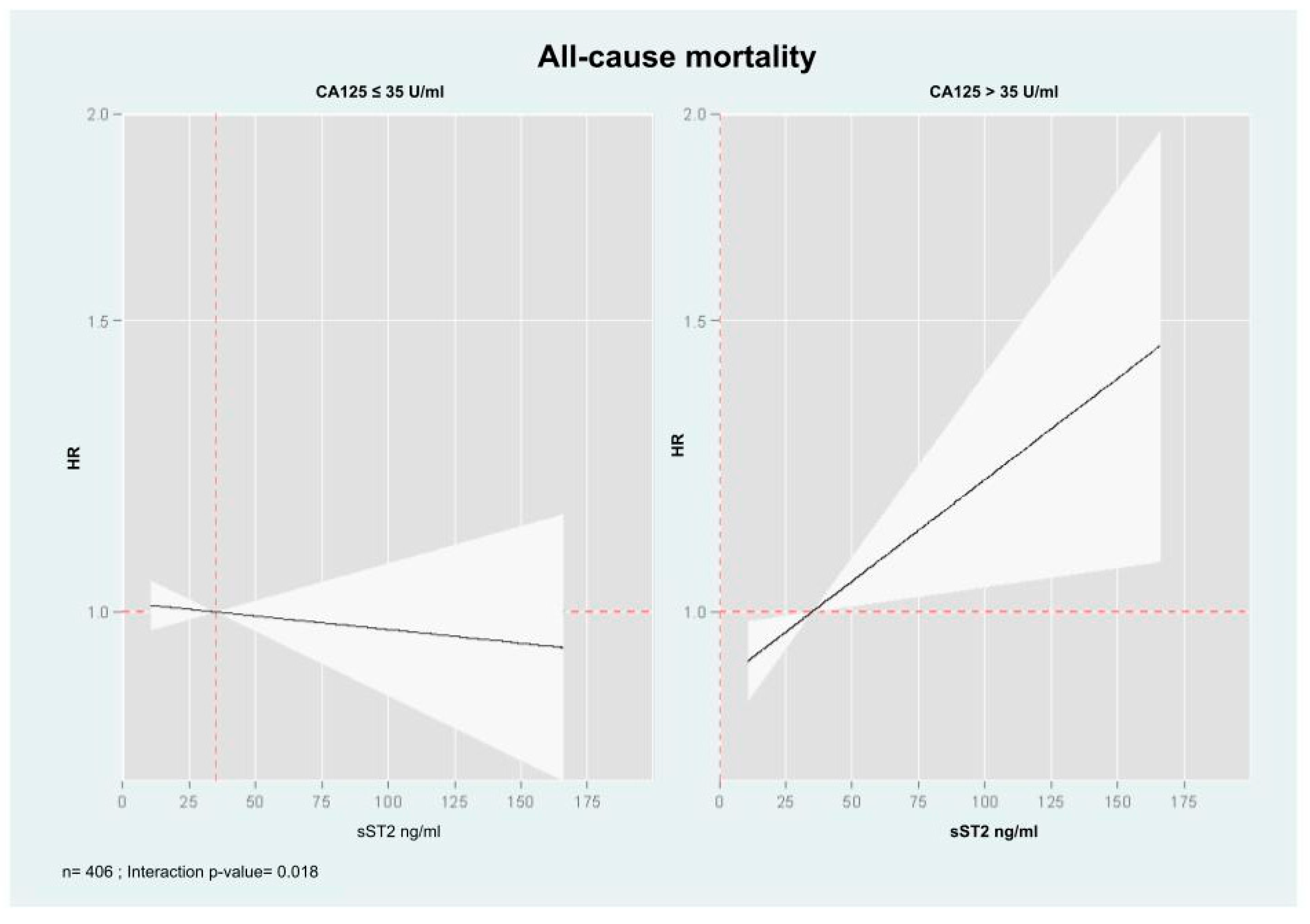

In a sensitivity analysis, performed in 406 patients in which MEESSI risk score was available, a similar heterogeneous association was found when estimates of risk were adjusted for MEESSI risk score (

Figure 5).

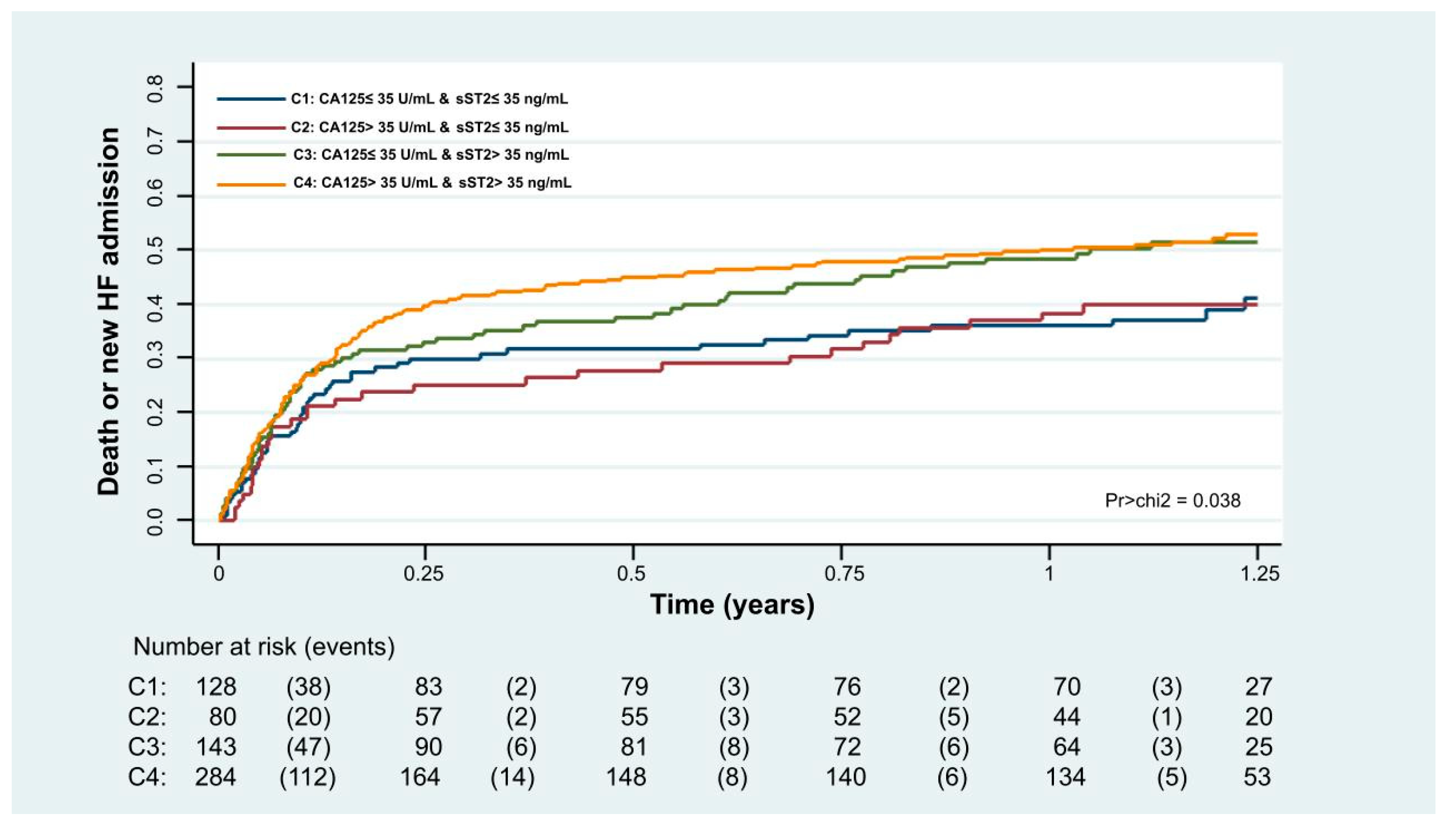

3.5.2. Combined of Death or HF-Admission

Kaplan-Meier curves also showed that combining both biomarkers, the risk was higher when both biomarkers were elevated, especially for the first 6 months. After this period, the curves were no longer diverging (

Figure 6, p=0.038).

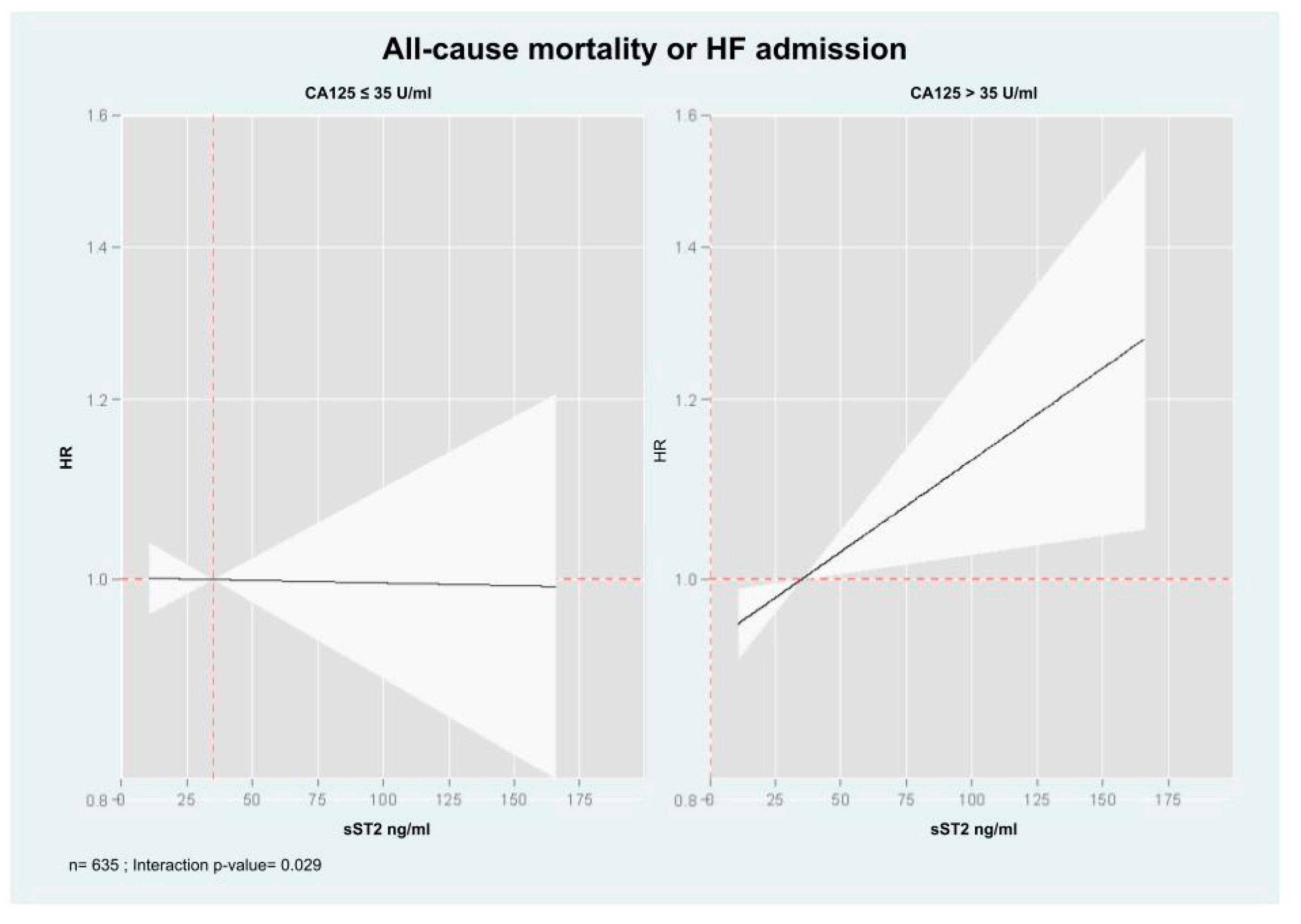

After multivariate adjustment, we also found that the sST2 risk was modified based on CA125 >35 U/mL vs. ≤35 U/mL (interaction p-value= 0.029). In patients with CA125 >35 U/mL, higher sST2 was significantly associated with an increased risk of the event (HR=1.02, CI 95%: 1.01 to 1.03, p=0.013, per increase in 10 ng/ml), as shown in

Figure 4. Conversely, in patients with CA125≤35 U/mL, sST2 was not related to this endpoint (

Figure 7). Likewise, this heterogeneous risk across CA125 strata was also present when estimates were adjusted for MEESSI risk score.

4. Discussion

In the present post-hoc study of the EAHFE registry, we found that the association between sST2 and long-term adverse outcomes (mortality and HF-hospitalizations) in patients with AHF was differentially influenced by CA125 concentrations. Indeed, the increased risk attributable to elevated sST2 levels was found when CA125 was >35 U/mL but not in those with CA125 ≤ 35 U/mL. This study builds upon previous findings, where the prognostic value of sST2 and Gal-3 were significantly influenced by CA125 levels [

7,

9]. The interaction between sST2 and CA125 underscores a complex interplay between inflammation and congestion in AHF, reaffirming the potential role of this mucin in modulating inflammatory and reparative activity in patients with HF [

7,

9,

13]. The underlying biological mechanisms for this interaction merit further exploration.

4.1. Structure and Pathophysiology of MUC16 (CA125)

MUC16 is a large transmembrane mucin with three major domains: an extracellular N-terminal domain, a large tandem repeat domain, and a C-terminal domain (CTD), with potential cleavage locations [

6,

14]. It plays a role in cellular protection, signaling, and tumor progression [

7,

14]. Cleavage of MUC16 occurs under conditions of cellular homeostasis, tumor progression, and inflammation, which facilitates the release of its N-terminal domain into the circulation, making CA125 a valuable biomarker [

7]. Meanwhile, after cleavage, the CTD can remain on the cell surface or translocate to the nucleus, binding to chromatin, where it acts as a transcriptional co-regulator (6). In malignancies such as ovarian [

15], and pancreatic cancer [

16], MUC16 CTD translocation drives the expression of invasion-related genes, such as NRP2 in pancreatic cancer, promoting disease progression. Moreover, recent evidence has identified MUC16 CTD as a component of a protein binding complex, mediated by N-glycan components, which includes EGFR, β1 integrin, and Gal-3 on the cell surface [

6,

17]. These interactions positively regulate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process that contributes to cancer metastasis, organ fibrosis, and tissue remodeling [

6,

18]. EMT is also implicated in pulmonary fibrosis, where TGF-β1 forms a protein complex with MUC16 CTD to activate fibrotic pathways [

18]. Similar mechanisms have been observed in prior studies [

13], performed in myocardial tissue, where MUC16 expression in epicardial fat correlates with markers of inflammation and fibrosis, suggesting a contributory role in myocardial remodeling. Literature linked EMT and soluble inflammation mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [

17].

4.2. Relationship of CA125 with Pro-Inflammatory Pathways and sST2

AHF is not only a consequence of structural or functional damage to the heart, it is also produced by an exacerbated inflammatory response. In this scenario, epicardial adipose tissue shifts its biology to a pro-inflammatory state, becoming a source of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, which have been associated with fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and myofibroblast activation [

13]. Along this line of thought, CA125 is upregulated in most of cases with AHF, and in this setting is associated with the severity of volume overload and inflammatory activity [

14]. Inflammatory stimuli is identified as a main driver for CA125 synthesis in mesothelial cells [

14] and prior studies have reported a positive correlation among cytokines and CA125 in AHF [

19] and is associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes [

20].

The mediator linking volume overload and elevated CA125 levels in AHF is unknown. However, we speculate the mechanical stress and inflammation caused by excessive tissue fluid accumulation [

14] subsequently activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways, leading an increase in CA125 levels [

5]. First, JNK activation promotes the synthesis of CA125. Second, changes in cell morphology and membrane stability, along with mechanical stress, activate the O-glycosylated extracellular domain of CA125, facilitating its shedding from mesothelial cells and thereby increasing its concentration in the peripheral circulation [

21].

ST2, located on chromosome 2q12 within the IL-1 gene cluster, is expressed primarily as two key isoforms: the membrane-bound ST2 (ST2L) and the soluble ST2, sST2. [

22,

23,

24]. ST2L serves as the receptor for IL-33 and is found on the surface of myocytes and T-lymphocytes (Th0), supporting protective cardiac effects by reducing fibrosis, hypertrophy, and apoptosis [

3,

22,

25]. In contrast, sST2—produced largely by cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells under hemodynamic overload, inflammation, and fibrotic stimuli—acts as a decoy receptor that neutralizes IL-33 [

24,

26]. Consequently, sST2 release dampens the beneficial IL-33/ST2L axis, shifts the immune response from a Th2 (anti-inflammatory) to a Th1 (proinflammatory) profile, and promotes cell death, fibrosis, and progression of heart failure [

3,

22,

25].

Our findings align with studies reporting that severe congestion—marked by high CA125 levels—is linked to upregulation of sST2 and other inflammatory pathways [

3,

9,

17]. Elevated CA125 may reflect a state of long-standing tissue fluid overload and inflammatory activation.

4.3. Differential Effects of sST2 Across CA125 Levels

Previously, in a post-hoc analysis of the IMPROVE-HF trial [

9] involving patients with AHF and renal dysfunction on admission, we found that sST2 was a strong predictor of CV-renal rehospitalizations only when CA125 levels exceeded 35 U/mL. Building on these findings, the present study expands the scope by examining the interaction between sST2 and CA125 in a larger cohort of patients with AHF diagnosed in hospital EDs. Notably, in this broader population, elevated sST2 again proves to be a robust prognostic indicator—specifically, for all-cause mortality and recurrent HF admissions among individuals with CA125 >35 U/mL.

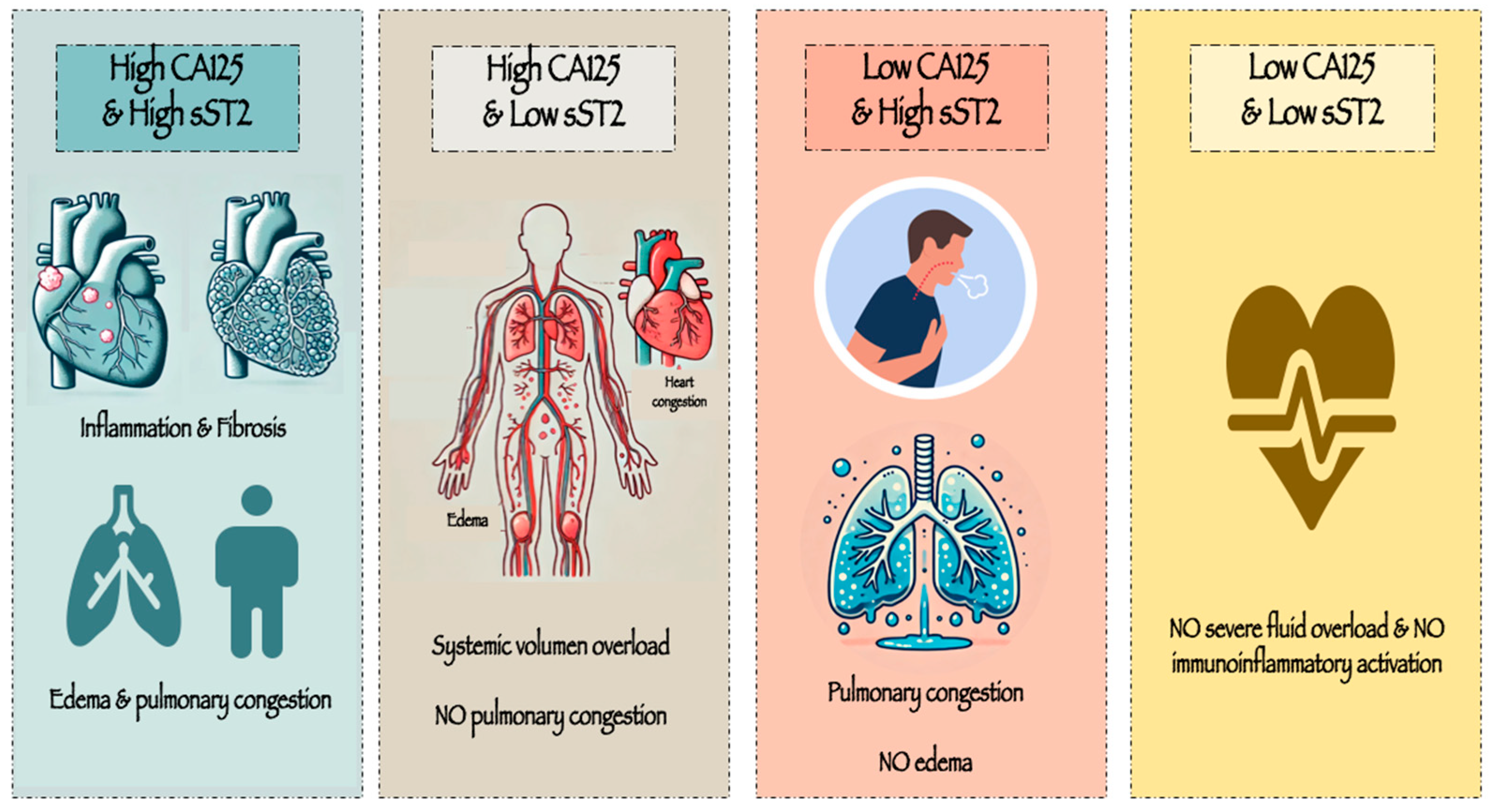

From a pathophysiological perspective, a concurrent rise in both CA125 and sST2 may indicate sustained tissue congestion together with pronounced inflammation and fibrosis. Conversely, patients whose CA125 exceeds 35 U/mL but present lower sST2 levels might reflect a subgroup characterized primarily by systemic volume overload, without marked pulmonary congestion—an important source of ST2 in heart failure. Meanwhile, patients who exhibit lower CA125 but higher sST2 levels may represent an acute, abrupt onset of AHF, primarily driven by pulmonary intravascular congestion rather than significant interstitial fluid overload. Lastly, those patients with low both biomarkers may be identified as those without severe fluid overload and no immunoinflammatory activation (

Figure 8).

One unanswered question is whether the relationship between sST2 and CA125 simply reflects a difference in inflammatory profiles or whether CA125 is mechanistically linked to the sST2 pathway. Future research is needed to clarify whether CA125 exerts a causal influence on sST2 biology or primarily serves as a marker of a distinct pathophysiological state.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the prognostic interplay between sST2 and CA125 in AHF. Elevated sST2 levels predicts adverse outcomes primarily in patients with high CA125 levels (>35 U/mL) but not in the rest. This interaction endorses the role of CA125 as a modulating factor of inflammatory activity in HF. Further studies are warranted.

Funding

This research was funded by CIBER Cardiovascular [grant numbers 16/11/00420 and 16/11/00403], Unidad de Investigación Clínica y Ensayos Clínicos INCLIVA Health Research Institute, Spanish Clinical Research Network (SCReN; PT13/0002/0031 and PT17/0017/0003), cofounded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional—Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and Proyectos de Investigación de la Sección de Insuficiencia Cardiaca 2017 from the Sociedad Española de Cardiología.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization, Arancha Martí-Martínez and Julio Núñez; Data curation, Julio Núñez; Formal analysis, Julio Núñez; Methodology, Julio Núñez; Resources, Arancha Martí-Martínez, Pere Llorens and Pablo Herrero-Puente; Supervision, Julio Núñez and Herminio López-Escribano; Visualization, Arancha Martí-Martínez; Writing – original draft, Arancha Martí-Martínez; Writing – review & editing, Julio Núñez, Herminio López-Escribano, Elena Revuelta-López, Anna Mollar, Marta Peiró, Juan Sanchis, Antoni Bayés-Genís, Arturo Carratala, Òscar Miró, Pere Llorens and Pablo Herrero-Puente. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (protocol code 2024/371).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

Abbreviations

| AHF |

Acute heart failure |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| CA125 |

Antigen carbohydrate 125 |

| CTD |

C-terminal domain |

| CV |

Cardiovascular |

| EAHFE |

Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Spanish Emergency Departments |

| EDs |

Emergency departments |

| EMT |

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| Gal-1 |

Galectin-1 |

| HF |

Heart failure |

| IL-33 |

Interleukin-33 |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| JNK |

c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MUC16 |

Mucin 16 |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association |

| P-Y |

Person-years |

| sST2 |

Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 |

| ST2L |

Membrane-bound ST2 |

| Th0 |

T-lymphocytes |

| TNF |

Tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Arrigo M, Jessup M, Mullens W, Reza N, Shah AM, Sliwa K, Mebazaa, A. Acute heart failure. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Mar 5;6(1):16. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0151-7. PMID: 32139695; PMCID: PMC7714436.

- Kurmani, S., Squire, I. Acute Heart Failure: Definition, Classification and Epidemiology. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017 Oct;14(5):385-392. doi: 10.1007/s11897-017-0351-y. PMID: 28785969; PMCID: PMC5597697.

- Riccardi M, Myhre PL, Zelniker TA, Metra M, Januzzi JL, Inciardi RM. Soluble ST2 in Heart Failure: A Clinical Role beyond B-Type Natriuretic Peptide. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023 Nov 17;10(11):468. doi: 10.3390/jcdd10110468. PMID: 37998526; PMCID: PMC10672197.

- Wang Z, Pan X, Xu H, Wu Y, Jia X, Fang Y, Lu Y, Xu Y, Zhang, J., Su, Y. Serum Soluble ST2 Is a Valuable Prognostic Biomarker in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Feb 9;9:812654. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.812654. PMID: 35224046; PMCID: PMC8863653.

- Kumric M, Kurir TT, Bozic J, Glavas D, Saric T, Marcelius B, D'Amario D, Borovac JA. Carbohydrate Antigen 125: A Biomarker at the Crossroads of Congestion and Inflammation in Heart Failure. Card Fail Rev. 2021 Jun 12;7:e19. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2021.22. PMID: 34950509; PMCID: PMC8674624.

- Giamougiannis P, Martin-Hirsch PL, Martin FL. The evolving role of MUC16 (CA125) in the transformation of ovarian cells and the progression of neoplasia. Carcinogenesis. 2021 Apr 17;42(3):327-343. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgab010. PMID: 33608706.

- Núñez J, Rabinovich GA, Sandino J, Mainar L, Palau P, Santas E; et al. (2015) Prognostic Value of the Interaction between Galectin-3 and Antigen Carbohydrate 125 in Acute Heart Failure. PLoS ONE 10(4): e0122360. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122360. PMID: 25875367.

- Pusceddu I, Dieplinger B, Mueller, T. ST2 and the ST2/IL-33 signalling pathway-biochemistry and pathophysiology in animal models and humans. Clin Chim Acta. 2019 Aug;495:493-500. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.05.023. Epub 2019 May 25. PMID: 31136737.

- Revuelta-López E, de la Espriella R, Miñana G, Santas E, Villar S, Sanchis J, Bayés-Genís A, Núñez, J. The modulating effect of circulating carbohydrate antigen 125 on ST2 and long-term recurrent morbidity burden. Sci Rep. 2025 Jan 14;15(1):1905. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-84622-7. PMID: 39809935; PMCID: PMC11733209.).

- Llorens P, Escoda R, Miró Ò, Herrero-Puente P, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Jacob J, Garrido JM, Pérez-Durá MJ, Gil C, Fuentes M, Alonso H, Muller, C., Mebazaa, A. Characteristics and clinical course of patients with acute heart failure and the therapeutic measures applied in Spanish emergency departments: Based on the EAHFE registry (Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments). Emergencias. 2015 Feb;27(1):11-22. Spanish. PMID: 29077328.

- Llorens P, Javaloyes P, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Jacob J, Herrero-Puente P, Gil V, Garrido JM, Salvo E, Fuentes M, Alonso H, Richard F, Lucas FJ, Bueno H, Parissis J, Müller CE, Miró Ò.; ICA-SEMES Research Group. Time trends in characteristics, clinical course, and outcomes of 13,791 patients with acute heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol. 2018 Oct;107(10):897-913. doi: 10.1007/s00392-018-1261-z. Epub 2018 May 4. PMID: 29728831.

- Rossello X, Bueno H, Gil V, Jacob J, Javier Martín-Sánchez F, Llorens P, Herrero Puente P, Alquézar-Arbé A, Raposeiras-Roubín S, López-Díez MP, Pocock, S., Miró, Ò. MEESSI-AHF risk score performance to predict multiple post-index event and post-discharge short-term outcomes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021 Apr 8;10(2):142-152. doi: 10.1177/2048872620934318. PMID: 33609116.

- Eiras S, de la Espriella R, Fu X, Iglesias-Álvarez D, Basdas R, Núñez-Caamaño JR, Martínez-Cereijo JM, Reija L, Fernández AL, Sánchez-López D, Miñana G, Núñez J, González-Juanatey JR. Carbohydrate antigen 125 on epicardial fat and its association with local inflammation and fibrosis-related markers. J Transl Med. 2024 Jul 3;22(1):619. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05351-z. PMID: 38961436; PMCID: PMC11223376.

- Núñez J, de la Espriella R, Miñana G, Santas E, Llácer P, Núñez E, Palau P, Bodí V, Chorro FJ, Sanchis J, Lupón J, Bayés-Genís, A. Antigen carbohydrate 125 as a biomarker in heart failure: A narrative review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021 Sep;23(9):1445-1457. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2295. Epub 2021 Jul 20. PMID: 34241936.

- Thériault C, Pinard M, Comamala M, Migneault M, Beaudin J, Matte I, Boivin M, Piché A, Rancourt, C. MUC16 (CA125) regulates epithelial ovarian cancer cell growth, tumorigenesis and metastasis. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Jun 1;121(3):434-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.020. Epub 2011 Mar 21. PMID: 21421261.

- Marimuthu S, Lakshmanan I, Muniyan S, Gautam SK, Nimmakayala RK, Rauth S, Atri P, Shah A, Bhyravbhatla N, Mallya K, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Datta K, Jain M, Ponnusamy MP, Batra SK. MUC16 Promotes Liver Metastasis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by Upregulating NRP2-Associated Cell Adhesion. Mol Cancer Res. 2022 Aug 5;20(8):1208-1221. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-21-0888. PMID: 35533267; PMCID: PMC9635595.

- Suarez-Carmona M, Lesage J, Cataldo D, Gilles, C. EMT and inflammation: Inseparable actors of cancer progression. Mol Oncol. 2017 Jul;11(7):805-823. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12095. Epub 2017 Jun 26. PMID: 28599100; PMCID: PMC5496491.

- Ballester B, Milara J, Montero P, Cortijo, J. MUC16 Is Overexpressed in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Induces Fibrotic Responses Mediated by Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Canonical Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 17;22(12):6502. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126502. PMID: 34204432; PMCID: PMC8235375.

- Miñana G, Núñez J, Sanchis J, Bodí, V., Núñez E, Llàcer, A. CA125 and immunoinflammatory activity in acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2010 Dec 3;145(3):547-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.081. Epub 2010 May 18. PMID: 20483181.

- Núñez J, Bayés-Genís A, Revuelta-López E, Ter Maaten JM, Miñana G, Barallat J, Cserkóová A, Bodi V, Fernández-Cisnal A, Núñez E, Sanchis J, Lang C, Ng LL, Metra M, Voors AA. Clinical Role of CA125 in Worsening Heart Failure: A BIOSTAT-CHF Study Subanalysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2020 May;8(5):386-397. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.12.005. Epub 2020 Mar 11. PMID: 32171764.

- Huang, F.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Huang, H. ; New mechanism of elevated CA125 in heart failure: The mechanical stress and inflammatory stimuli initiate CA125 synthesis. Med. Hypotheses 2012, 79, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Xiao P, Song D, Song, D., Chen, Z., Li, H. Growth stimulation expressed gene 2 (ST2): Clinical research and application in the cardiovascular related diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Nov 4;9:1007450. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1007450. PMID: 36407452; PMCID: PMC9671940.

- Xing, J., Liu, J., Geng, T. Predictive values of sST2 and IL-33 for heart failure in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2021 Dec;246(23):2480-2486. doi: 10.1177/15353702211034144. Epub 2021 Aug 3. PMID: 34342552; PMCID: PMC8649928.

- Aleksova A, Paldino A, Beltrami AP, Padoan L, Iacoviello M, Sinagra, G., Emdin, M., Maisel AS. Cardiac Biomarkers in the Emergency Department: The Role of Soluble ST2 (sST2) in Acute Heart Failure and Acute Coronary Syndrome-There is Meat on the Bone. J Clin Med. 2019 Feb 22;8(2):270. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020270. PMID: 30813357; PMCID: PMC6406787.

- Homsak, E., Gruson, D. Soluble ST2: A complex and diverse role in several diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Aug;507:75-87. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.04.011. Epub 2020 Apr 16. PMID: 32305537.

- Castiglione V, Aimo A, Vergaro G, Saccaro, L., Passino, C., Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2022 Mar;27(2):625-643. doi: 10.1007/s10741-021-10105-w. Epub 2021 Apr 14. PMID: 33852110; PMCID: PMC8898236.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).