1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is one of the most common chronic autoimmune diseases that tends to occur in children an adolescents, although it can affect people of any age. T1DM results from autoimmune destruction of the β-cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans, ultimately leading to absolute insulin deficiency and lifelong dependence on exogenous insulin [

1]. Interestingly, the incidence of T1DM has increased significantly in recent decades. At the same time, the global incidence of vitamin D deficiency has increased in all age groups, including children and adolescents [

2,

3]. It should be noted that the incidence of T1DM is higher in high latitude regions (e.g. Canada and Scandinavian countries) where there is less exposure to sunlight and consequently a higher incidence of vitamin D deficiency, leading to the hypothesis that vitamin D may play a role in the T1DM process [

4,

5]. In addition, a recent meta-analysis found a positive association between the latitude of the patient's residence and the risk of T1DM. This also suggests that people living at high latitudes may be predisposed to T1DM; whereas people living near the equator would synthesise enough vitamin D due to the strong solar ultraviolet B radiation available [

6]. In addition, a number of observational studies have shown that children with new-onset T1DM tend to have significantly lower vitamin D levels than healthy controls children [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

The physiological role of vitamin D goes far beyond the regulation of calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism, and exerts a wide variety of extra-skeletal effects. Indeed, Vitamin D is now considered a pleiotropic hormone, exerting its effects through both genomic and non-genomic actions. Most of the effects of vitamin D are mediated by its interaction with a nuclear transcription factor or vitamin D receptor (VDR) and subsequent binding to specific DNA sequences, regulating the expression of a large number of target genes involved in several physiological processes, including cellular proliferation and differentiation, as well as anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities (genomic pathway) [

14,

15,

16].

Because of the widespread distribution of VDRs throughout the human body, including immune cells (antigen-presenting cells and activated T and B lymphocytes) and pancreatic β cells, several experimental and epidemiological studies support the ability of vitamin D to prevent the pathogenesis of T1DM [

17]. This suggests that vitamin D deficiency may be an important environmental factor in the development of the disease. The beneficial effects of vitamin D in T1DM would be based on its functional versatility in various immune populations, such that vitamin D could improve glucose homeostasis by preserving β-cell mass, reducing inflammation and decreasing autoimmunity. In fact, over the last decade, numerous studies have shown associations between vitamin D deficiency and the risk of developing autoimmune diseases, including T1DM [

6,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The aim of this review is to produce a comprehensive literature review (narrative review) on (a) research progress on the possible function of vitamin D status as an environmental risk factor in the pathogenesis of T1DM and (b) the assessment of the potential role of vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of T1DM. This review is based on an electronic search of the PubMed database of the US National Library of Medicine for literature published between January 2011 and December 2024, conducted by two independent researchers. The following specific keywords (Medical Subject Headings) were used alone or in combination for the search: “vitamin D” and “Type 1 diabetes mellitus”.

2. Vitamin D Synthesis and Metabolism

Vitamin D is known as “sunshine hormone”. In fact, it is a steroid hormone that is obtained mainly (80-90%) from exposure to sunlight (vitamin D3) and to a lesser extent from food (vitamin D2). When exposed to solar ultraviolet B radiation, 7-dehydrocholesterol present in the human skin is converted to vitamin D3. Vitamin D (including vitamin D2 or D3) in the circulation is bound to vitamin D binding protein (VDBP), which transports it to the liver. There, Vitamin D is converted by vitamin D 25-hydroxylase (encoded by the CYP2R1) to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] or calcidiol (used as a biomarker for vitamin D status). 25(OH)D then circulates bound to VDBP, and reaches the kidneys where it is activated by 25(OH)D-1αhydroxylase (encoded by the CYP27B1) to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D] or calcitriol, which is the biologically active form of vitamin D.

According to the US Endocrine Society’s guidelines, calcidiol levels are considered the best indicator of organic vitamin D content, given its long half-life (two to three weeks). Vitamin D deficiency was defined as calcidiol lower than 20 ng/mL (<50 nmol/L). Vitamin D insufficiency is when calcidiol levels fluctuate between 20 and 29 ng/mL, and vitamin D sufficiency is when calcidiol levels reach or overtake 30 ng/mL (>75 nmol/L). That is, optimal vitamin D levels range between 30 and 50 ng/mL (75–125 nmol/L) and maximum safe levels go up to 100 ng/mL (250 nmol/L) [

22].

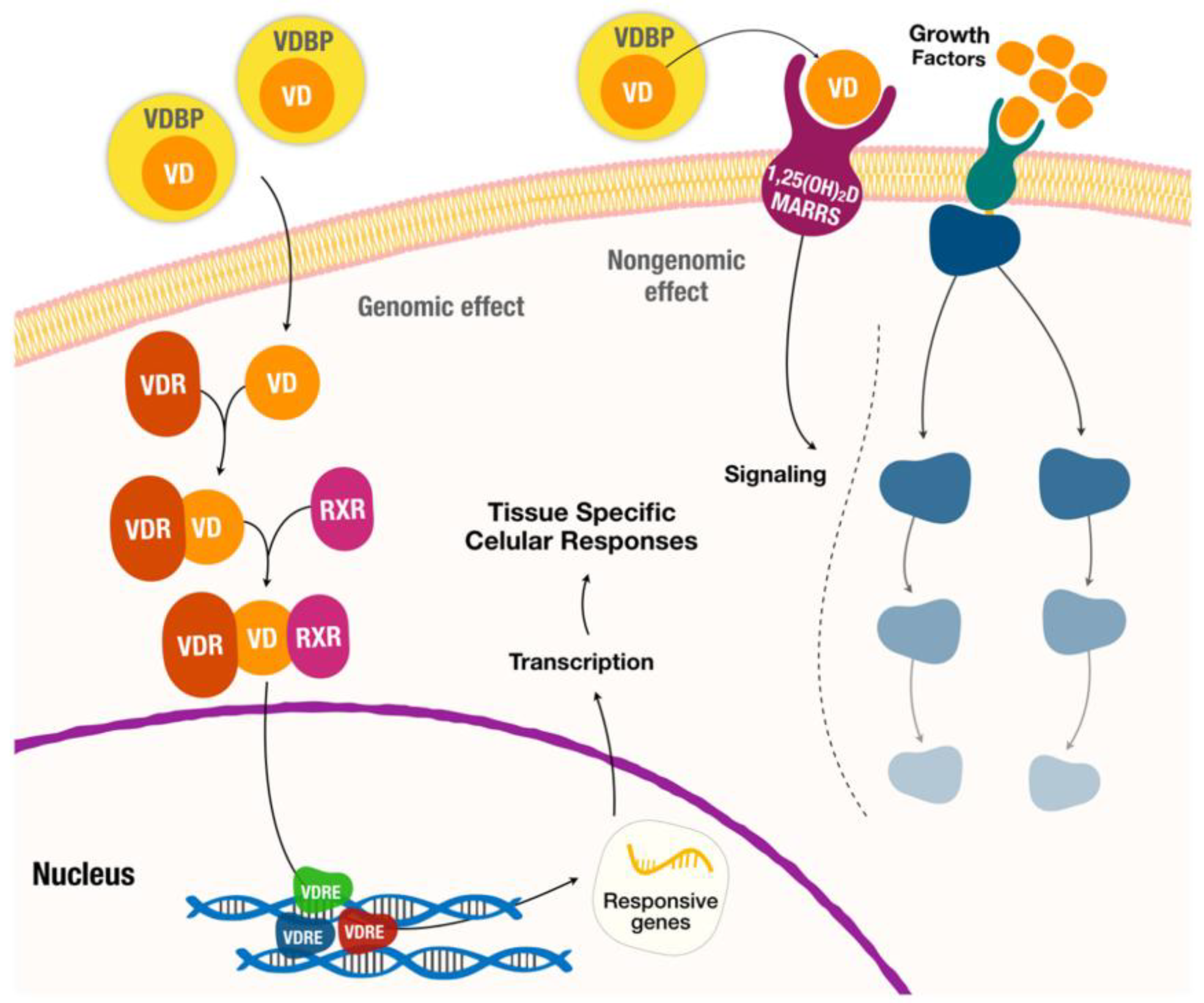

For the genomic pathways (

Figure 1), vitamin D binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which acts as a transcription factor by forming a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR). The VDR/RXR complex then translocates to the nucleus and binds to specific nucleotide sequences in DNA (also known as VDRE, vitamin D response elements) to modulate the expression of a substantial number of target genes (about 5-10% of the total human genome). In addition, vitamin D induces rapid non-genomic cellular responses by binding to a membrane receptor, called membrane-associated rapid response steroid (MARRS), to regulate several intracellular processes (calcium transport, mitochondrial function, ion channel activity, etc.) [

5,

14,

15,

23,

24].

3. Pathogenesis and Natural History of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

T1DM is a complex multifactorial disease in which environmental factors and genetic predisposition interact to promote the induction of an autoimmune response against β-cells [

25]. Both humoral and cellular immune responses are involved in the pathogenesis of T1DM. The natural history of T1DM shows that its clinical diagnosis occurs several years after the onset of the autoimmune process of β-cell damage. In fact, by the time T1DM is diagnosed, approximately 70-80% of the β-cell mass has been destroyed [

26].

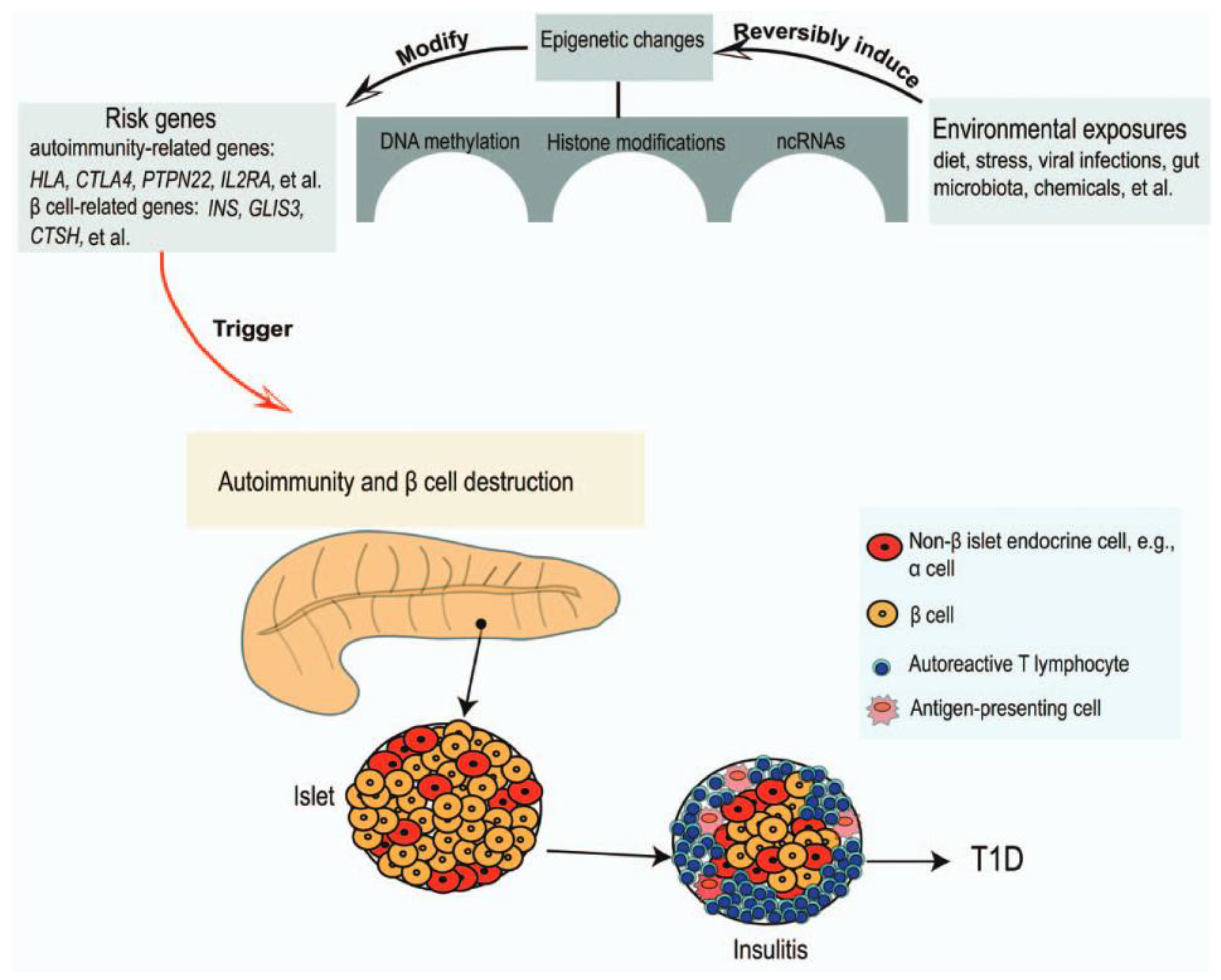

The genetic predisposition to β-cell autoimmunity and subsequently T1DM, occurs mainly in individuals with specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II haplotypes involved in antigen presentation: HLA-DR3-DQ2 or HLA-DR4-DQ8, or both; although other genes may also be involved, either related to autoimmunity (CTLA4, PTPN22, IL2RA, etc.) or to β-cells (INS, GLIS3, CTSH, etc.) [

27,

28,

29]. The increase in the prevalence of T1DM in recent decades cannot be attributed to genetic factors alone, as environmental factors most likely play a role in triggering islet autoimmunity. In addition, evidence from incomplete concordance of diabetes incidence in monozygotic twins suggests that environmental factors also play critical a roles in T1DM pathogenesis. In other words, the selective destruction of β-cells would be caused by an interaction between risk genes and environmental factors.

To date, viral infections have been considered the most important environmental factors in initiating the process of autoimmune destruction of β-cells. There is no specific ‘diabetes virus’, but several agents associated with diabetes have been described, including rubella, mumps, and measles viruses, varicella-zoster virus, enterovirus, adenovirus, rotavirus, coxsackievirus, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr virus, human endogenous retroviruses and also SARS-CoV-2 [

30]. Viruses can damage pancreatic β-cells either by direct cytolysis or by inducing an autoimmune response against β-cells. It is now believed that viral induction of an autoimmune response may be the result of a phenomenon of molecular mimicry, as some similarities have been described between the amino acid sequence of some β-cells molecules and proteins derived from several viruses (adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, coxsackievirus, cytomegalovirus, etc.). This means that the similarity of particle fragments derived from viral proteins to β-cell antigens may contribute to the activation of autoreactive T cells and the initiation of the autoimmunity process leading to the destruction of the pancreatic islets. For virions to be destroyed in the host, the viral peptides must be presented by antigen-presenting cells (such as dendritic cells and macrophages). If the presented antigens are molecularly similar to those of the organism, autoreactive B and T lymphocytes are produced. As a result, these cells may cross-react with virions and self-antigens on the surface of pancreatic cells (molecular mimicry model). However, it is extremely difficult to prove a cause-effect relationship between viral infections and the development of T1DM, as the period between viral exposure and the onset of clinical symptoms of T1DM is often very long.

In recent years, in addition to viral infections, several epidemiological studies have described new environmental factors, such as nutrition in the first months of life, gut microbiota and climatic conditions, including higher latitudes and reduced sunlight exposure and/or vitamin D deficiency, which may play a role in triggering islet autoimmunity and T1DM in subjects at high genetic risk. While breastfeeding has a protective role against autoimmunity, studies show conflicting results on the possible impact of cow's milk, gluten or Omega-3 fatty acids intake in children on the risk of T1DM [

31,

32]. Dysbiosis is associated with abnormalities in the activity of the immune system. In fact, lower gut microbiota diversity appears to be associated with an increased risk of T1DM [

33]. Vitamin D deficiency is common in the pediatric population with T1DM, particularly at the onset of the disease [

8,

10,

18,

34]. A recent prospective study (The TEDDY study) of children with genetic risk for T1DM (HLA genotypes or family history of T1DM) who had persistent islet autoimmunity (positivity for at least one autoantibody to the same antigen in consecutive controls) conducted at centres in the USA (Colorado, Georgia/Florida, Washington) and Europe (Finland, Germany, and Sweden) shows that higher vitamin D concentrations were associated with a lower risk of islet autoimmunity, but this effect was more pronounced in cases with minor alleles of the VDR

ApaI polymorphism [

19,

35]. There is also high-level evidence (systematic reviews, meta-analyses) that adequate vitamin D in early life reduces the risk of diabetes [

6,

36]. All of these factors could alter gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms (particularly DNA methylation, histone modifications or long non-coding RNA) thereby inducing an aberrant immune response and progressive β-cells destruction (

Figure 2), and thus be involved in the pathogenesis of T1DM [

29,

37,

38].

The core of the autoimmune process in T1DM is a breakdown of immune self-tolerance to pancreatic β-cells autoantigens, resulting in their destruction by infiltration of the pancreatic islets by monocytes/macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, helper (CD4+) and cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) and plasma cells, known as autoimmune insulitis. β-cells are destroyed by apoptosis and necrosis,

First, in children at high genetic risk for T1DM, viral infections or other environmental factors cause β-cells apoptosis, resulting in the release of β-cell antigens. Self-antigens induce the activation of antigen presenting cells (APCs). Activated APCs, mainly dendritic cells (DCs) and NKs, present self-antigens to naïve CD4+ T cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes and promote their activation. Subsequently, CD4+ T cells expand and differentiate into several effector subpopulations, including Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg cells, with IL-12 produced by APCs mainly inducing Th1 differentiation. Specifically, Th1 cells (autoreactive T cells) infiltrate pancreatic islet and releasse proinflammatory interleukins (IL), such as IL-2, tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interferon γ (IFN-γ), which induce migration of macrophages and NK cells to pancreatic islets (insulitis) and enhance the destruction of pancreatic β-cells by apoptotis/necrosis. In addition, Th1 cells activate CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic T cells) via IL-2 and IFN-γ, which also induce pancreatic β-cell apoptosis/necrosis. Although increased Th1 cell activity -also known as the Th1 profile- and, consequently, Th1/Th2 cell imbalance has been considered the main contributor to the development of T1DM, other authors suggest that an increased Th17/Treg ratio would also play a key role in the pathogenesis of T1DM.

In addition to autoreactive T cells against β-cell autoantigens, which are considered an important factor of cell damage, a humoral response is also involved in the mechanism of the autoimmune process and in the destruction of pancreatic islets. Th1 recruitment is associated with the activation and expansion of B lymphocytes and their subsequent differentiation into autoantibody-producing plasma cells, which further contribute to the inflammatory process and tissue destruction. A higher proportion of plasma cells into insulitis has been associated with a faster β-cell decline [

39].

In fact, the clinical symptoms of T1DM are preceded by a long period of “pre-diabetes”, characterized by specific histological features (autoimmune insulitis), and the presence of serum islet autoantibodies: anti-insulin antibodies (IAAs), antibodies against insulin-producing islet cells (ICAs) and/or antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65), antibodies to insulinoma-associated antigen-2 (anti-IA2) and antibodies to zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8), although patients remain normoglycaemic and asymptomatic (stage 1). Subsequently, patients retain islet autoantibody positivity and remain asymptomatic, but exhibit dysglycaemia as evidencied by abnormal glucose tolerance test (stage 2). The persistent presence of at least two types of β-cell autoantibodies, which are considered predictive biomarkers of irreversible islet autoimmunity [

40], lead to the onset of clinical T1DM (symptomatic disease). The first clinical symptoms of the disease (polyuria, polydipsia, fatigue, weight loss, diabetic ketoacidosis, etc.) usually appear several years after the onset of the autoimmune process, when most of the pancreatic β-cells have been destroyed (stage 3), and T1DM is definitively established [

28,

41,

42].

Nevertheless, a few weeks after clinical onset of the disease and initiation of insulin therapy, about half of all patients with T1D experience a transient and partial spontaneous remission or ¨honeymoon phase¨ [

43]. During this phase, the remaining β-cells are still able to produce sufficient insulin, leading to a significant reduction in exogenous insulin requirements. Although the pathogenesis of the remission phase remains unknown, it is of remarkable clinical importance as it can be used to investigate the potential efficacy of different therapeutic agents to halt or slow down the autoimmune process and disease progression in T1DM [

44].

4. Immunomodulatory Effects of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases

The immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D is based on a genomic response and its ability to modify gene transcription. The most important role of vitamin D in autoimmune diseases, including T1DM, is its ability to induce immune tolerance as well as anti-inflammatory effects.

Vitamin D is involved in the regulation of both innate and adaptive immunity. Effects of vitamin D on both NKs, macrophage and DCs include inhibition of inflammatory cytokine release (IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IFN-γ), and increased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10. It also affects the differentiation of DCs, resulting in the preservation of immature DCs (tolerogenic phenotype) and, consequently, a reduction in the number of antigen-presenting cells and activation of naïve CD4+ T cells, thus contributing to the induction of a tolerogenic state. Inhibition of DCs differentiation and maturation therefore induces T-cell anergy (unresponsiveness), which is particularly important in the context of an autoimmune process.

Vitamin D promotes the differentiation of T-helper lymphocytes from a Th1 and Th17 profile to a Th2 and Treg profile, increasing the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL10, while decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17 and IL-21. In addition, Treg cells are also capable of suppressing the proliferation of CD8+ (cytotoxic lymphocytes) and antigen-presenting cells. Thus, vitamin D would modulate cell-mediated immune responses and regulate the inflammatory activity of T cells, an important role in the prevention of autoimmune responses.

With respect to B-lymphocyte regulation, vitamin D impairs B cell activation and proliferation, plasma cell differentiation, memory B cells formation, and autoantibody production. These effects of vitamin D on B-lymphocyte homeostasis may be clinically relevant in T1DM, as autoreactive antibodies are involved in the pathophysiology of autoimmunity.

In summary, the immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D is characterized by induction of immune tolerance and T cell anergy, impairment of B cell activity and antibody production, and reduction of the inflammatory response. Therefore, it can be suggested that vitamin D could play an important therapeutic role in reducing the risk of autoimmune process of T1DM. [

5,

41,

42,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

5. Vitamin D Status and the Risk of T1D

A multicentre study (the POInT study) was recently been conducted in a large sample of infants and children aged 4-7 months to 3 years (longitudinal design) with a high genetic risk of developing β-cell autoantibodies, as defined by HLA genotype or family history of T1DM, in five European countries (Belgium, England. Germany, Poland, and Sweden). Multivariate logistic regression analysis concluded that vitamin D deficiency is common and persistent in infants and children with a genetic predisposition to develop T1DM [

12]. A systematic review and meta-analysis was recently conducted that included a total of 45 studies of acceptable quality [

50] with statistical information on vitamin D deficiency in children and adolescents with T1DM. These studies included 6,995 participants from 25 countries in Africa (Egypt and Tunisia), Oceania (Australia), Europe (United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Ukraine and Germany), North America (USA and Canada) and Asia (Turkey, Korea, Iran, India, China, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Kuwait, Bangladesh and Iraq). The results of this meta-analysis showed that the proportion of vitamin D deficiency among children/adolescents with T1DM was 45%. Specifically, vitamin D deficiency appears to be much more prevalent in patients with T1DM than in healthy individuals [

13]. Several authors who have measured serum vitamin D levels in newly diagnosed children have observed significantly lower serum vitamin D levels at the onset of T1DM compared to controls [

7,

10,

11,

18]. In addition, serum vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients admitted with diabetic ketoacidosis than in patients without ketoacidosis [

7,

9]. Although numerous researchers have suggested an association between vitamin D deficiency and T1DM, it is not entirely clear whether vitamin D insufficiency is a trigger for T1DM or a consequence of the disease.

There is now a body of literature suggesting that vitamin D status may be an important environmental risk factor in the pathogenesis of T1DM, rather than a consequence of pathophysiological changes resulting from the disease. Numerous authors have investigated whether polymorphisms of genes involved in vitamin D metabolism, especially those encoding vitamin D hydroxilases and VDBP, may influence the risk of islet autoimmunity and T1DM. Some observational studies have reported that various polymorphisms in CYP2R1 (the gene encoding vitamin D 25-hydroxylase), CYP27B1 (the gene encoding vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase) and the VDBP gene were significantly associated with an increased risk of T1DM [

41], In contrast, a recent Mendelian randomisation analysis involving 9356 cases (from Canada, United Kingdom and United States) failed to demonstrate an association between any polymorphism in these genes and the risk of T1DM [

51]. Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that included studies from different geographical locations did not confirm the hypothesis that polymorphisms in these vitamin D-related genes might be associated with an increased risk of T1DM [

52]. Some studies have shown an association between VDBP genetic polymorphisms and the risk of T1DM, but these results have not been subsequently confirmed.

However, a potential role of VDR gene polymorphisms in T1DM seems more suggestive. There are four known VDR polymorphisms that have been extensively studied for their potential role in T1DM:

ApaI, BsmI, TaqI, and FokI. For example, the Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY study), mentioned above, is a large prospective study of children at increased T1DM risk, as defined by HLA genotype or family history of T1DM, conducted at centers in the USA and Europe. The study found that higher serum vitamin D concentration was associated with a decreased risk of islet autoimmunity, but only in those with VDR gene

Apal polymorphism. That is, higher concentration of circulating vitamin D in combination with VDR genotype (Apal) may decrease risk of developing insulitis autoimmune, suggesting that the underlying mechanism involves vitamin D action [

19]. In addition, the results of a meta-analysis conducted in Asian populations (China, Japan, India, Iran and Turkey) suggested that the

BsmI polymorphism might be a risk factor for susceptibility to T1DM in the East Asian population, and that the

FokI polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of T1DM in the West Asian population. However, the authors reported that the statistical power was not sufficient due to the limited number of included articles, and concluded that further studies are essential to confirm their findings [

53]. Furthermore, a study (case-control design) was recently conducted in three major hospitals in Kuwait (Adan, Farwania and Mubarak Al-Kabeese) and the genotypes of four VDR gene polymorphisms were determined in 253 children with newly diagnosed T1DM. The results of this study show that the VDR gene

FokI and

TaqI polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to T1DM, and thus contribute significantly to the genetic predisposition to T1DM [

20]

. Finally, a prospective cohort study of 101 children with newly diagnosed T1DM demonstrated that adequate vitamin status (≥30 ng/mL) together with the

FokI and

TaqI polymorphisms of the VDR gene could lead to greater preservation of residual β-cell mass and function [

54]. However, although VDR gene polymorphisms have recently been associated with susceptibility to various autoimmune diseases, there is no comprehensive meta-analysis of VDR gene polymorphisms and the risk of T1DM, and the existing literature is relatively inconsistent [

55].

In 2012, the first study (case-control design) reporting an association between low vitamin D levels during pregnancy and an increased risk of T1DM in offspring was conducted in a cohort of 35,940 pregnant women in Norway. Because of the long follow-up period (15 years), virtually all children in the original maternal cohort who developed T1DM in childhood could be identified. This study showed that the mothers of children who developed T1DM before the age of 15 had significantly lower serum vitamin D levels -during the last trimester of pregnancy- than the mothers of children who did not develop the disease [

56]. In contrast, a case-control study of 383 Finnish pregnant women (Finnish Maternity Cohort) found no difference in serum vitamin D levels during the first trimester of pregnancy between mothers of children who subsequently developed T1DM and mothers of non-diabetic children of the same age (0-7 years) [

57]. A report based on the All Babies In Southeast Sweden (ABIS) study, which used questionnaire data from 16,339 mothers, found no significant association between vitamin D intake during pregnancy and the risk of T1DM in children aged 14-16 years [

58]. Similarly, the aforementioned TEDDY study found no association between maternal of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and an increased risk of islet autoimmunity [

59]. Finally, a meta-analysis of relevant observational studies found insufficient evidence for an association between maternal vitamin D intake and risk of T1DM in offspring [

60]. That is, given the limited and inconsistent evidence at present, large randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to clarify whether prenatal vitamin D exposure modifies the risk of T1DM later in life. It should be noted that vitamin D supplementation in early childhood appears to play a more relevant role than prenatal vitamin D exposure in determining the risk of T1DM. In fact, several meta-analysis of observational studies suggest that there is evidence that vitamin D supplementation in infancy may offer protection against the development of T1DM [

60,

61].

Results from long-term follow-up studies in children suggest no association between pre-diagnosis vitamin D status and the occurrence of T1DM later in life. For example, in a cross-sectional study of 108 children with pre-diabetes (defined as the presence of multiple islet autoantibodies), the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was higher in children with pre-diabetes than in controls. The cumulative incidence of T1DM at 10 years after seroconversion was similar between children with vitamin D deficiency and those with sufficient vitamin D levels. That is, vitamin D deficiency was not associated with faster progression to T1DM in children with multiple islet autoantibodies [

62]. In addition, the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) was a prospective study conducted in Colorado (USA) involving 448 children between birth and 8 years of age. All were at increased risk of developing T1DM (HLA genotype or first-degree relatives of patients with T1DM). Autoantibodies and vitamin D status were checked regularly during follow-up. Their results showed that in children at increased risk of T1DM, there was no association between vitamin D status in infancy or throughout childhood with the risk of islet autoimmunity or progression to T1DM [

63]. Finally, the Type 1 Diabetes Prevention and Prediction Study (DIPP) was a prospective cohort project in Finland with 252 children at increased risk for T1DM (HLA genotype and/or seroconversion to islet cell antibody positivity). During their follow-up (12 years), circulating vitamin D concentrations were measured from 3 months of age until diagnosis of T1DM. Their results showed that there was no difference in vitamin D status between children who progressed to T1DM and controls. In conclusion, this prospective study suggests that the development of T1DM would not be associated with vitamin D status [

64].

6. Vitamin D Supplementation in Type 1 Diabetes

Experimental studies using non-obese diabetic mice as a model of human T1DM have demonstrated protective effects of vitamin D against islet autoimmunity and progressive β-cell dysfunction. Also importantly, vitamin D deficiency in early life results in a higher incidence and earlier onset of diabetes. Calcitriol and its analogues have also been shown to prevent insulitis and thus diabetes, especially when given at an early age (when the immune attack on β-cells is in its early stages). In short, pre-clinical evidence suggest that vitamin D and its analogues appear to be able to protect β-cell mass and function from autoimmune attack by several mechanisms, including (i) promoting the shift from a Th1 to a Th2 cytokine expression profile and so decreasing the number of Th1 cells (autoreactive T cells), (ii) enhancing the clearance of autoreactive T cells and decreasing the Th1 cell infiltration within the pancreatic islets, (iii) reducing cytokine-induced β-cell damage, and (iv) promoting the differentiation and suppressive capacity of Treg cells [

41,

65].

The efficacy of vitamin D in halting or reversing islet autoimmunity observed in preclinical studies has stimulated numerous interventional studies and randomised controlled trials that have established beneficial clinical effects of different forms of vitamin D or analogues (in addition to insulin therapy) in patients with T1DM [

36,

41,

66]. In other words, insulin therapy supplemented with vitamin D appears to be able improve the preservation of residual pancreatic β-cell function in patients with T1DM.

Table 1 displays some relevant interventional studies conducted in children/adolescents with new-onset T1DM which resulted in significant preservation of residual pancreatic β-cell function and improved glycaemic control.

Several interventional studies and randomised controlled trials have shown beneficial effects of cholecalciferol supplementation in addition to insulin therapy in children with new-onset T1DM, in terms of preservation of residual β-cell function and improvement of glycaemic control. In addition, cholecalciferol also appears to improve the suppressive function of Tregs, reduce autoantibody titres and daily insulin requirements [

67,

68,

69]. However, cholecalciferol supplementation in children with established T1DM (disease duration >12 months) did not show protective effects on pancreatic β-cell function or glycaemic control [

70,

71,

72]. In other words, the hypothesis that the protective effect of cholecalciferol supplementation is only visible when the disease duration is less than 1 year (patients with new-onset T1DM) seems to be confirmed [

73].

Several studies on children with new-onset T1DM have reported potential protective effects on β-cell function from the use of cholecalciferol in combination with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), lansoprazole or sitagliptin. Omega-3 PUFAs (especially eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)) have anti-inflammatory properties. In a placebo-controlled cohort study 26 children with new-onset T1DM, the combination of high-dose of cholecalciferol (1000 IU/day) and omega-3 PUFAs (EPA + DHA, 50-60 mg/kg/day) added to insulin therapy showed a reduction in insulin requirements after 12 months of supplementation. Therefore, these results suggest that this co-supplementation would preserve residual endogenous insulin secretion by attenuating autoimmunity and counteracting inflammation [

74]. On the other hand, lansoprazole is a proton pump inhibitor (PPIs) that increase gastrin levels, and gastrin plays an important role in the regulation of β-cell neogenesis. Indeed, experimental and clinical studies have reported improved glycaemic control in response to PPIs. In a placebo-controlled observational study of 14 children with new-onset T1DM, combination therapy with cholecalciferol (2,000 IU/day) and lansoprazole 15 mg (<30 kg) or 30 mg (>30 kg) for six months in addition to insulin therapy was associated with a slower decline in residual β-cell function and lower insulin requirements [

75]. Finally, sitagliptin is a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor used as a hypoglycaemic agent. It reduces α-cell glucagon secretion, increases β-cell insulin secretion and may stimulate β-cell proliferation. A recent retrospective case-control study in 46 children/adolescents with newly diagnosed T1DM showed that co-administration of cholecalciferol (5,000 IU/day) plus sitagliptin (50 mg/day) in addition to insulin therapy can significantly prolong the duration of the clinical remission phase through synergistic anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties [

76]. Obviously, randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm whether these combinations can lead to preservation of β-cell function in children with new-onset T1DM.

There are few data on the efficacy of ergocalciferol in T1DM. However, a recent randomised, placebo-controlled trial showed that ergocalciferol supplementation (50,000 IU/week for 2 months, then fortnightly for 10 months) in addition to insulin therapy improved glycaemic control and reduced serum TNF-α concentration and total daily insulin dose. In other words, these results suggest a protective action of ergocalciferol on residual β-cell function in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed T1D [

77]. However, larger studies are needed to quantify the effect of ergocalciferol in young people with T1D.

There are also few data on the efficacy of calcidiol supplementation in newly diagnosed T1DM. A pilot intervention in 15 children with new-onset T1D who received calcidiol supplementation for one year (in addition to insulin treatment) showed a significant reduction in mononuclear reactivity against GAD-65 along with daily insulin dose, suggesting a potentially conservative effect of β-cells. Furthermore, calcidiol could modulate the immune response to β-cell autoantigens by local conversion to calcitriol (immune cells express 1α-hydroxylase and are therefore able to locally convert calcidiol to calcitriol) [

78]. Unfortunately, the small sample size of these studies does not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn about the efficacy of calcidiol in T1DM; therefore, future prospective interventional studies should be conducted.

Studies of supplementation of the active form of vitamin D (calcitriol) in addition to insulin therapy for the treatment of new-onset T1DM have been disappointing. Two randomized placebo-controlled trials showed that calcitriol supplementation at a dose of 0.25 μg/day for 18 to 24 months was ineffective in preserving residual β-cell function and improving glycemic control in patients (children and young adults) with new-onset T1DM [

79,

80]. The negative results could be due to the doses of calcitriol administered in both studies, or the short serum half-life of calcitriol could lead to fluctuations in its serum concentration that would condition its immunomodulatory effects on β-cells. This means that larger studies with longer observation periods and calcitriol dose stratification would be needed.

Alphacalcidol (1α-hydroxycholecalciferol) is a vitamin D analogue that is converted to calcitriol in the liver by the enzyme vitamin D-25-hydroxylase without the need for a secondary renal hydroxylation. In addition, alphacalcidol improves immune senescence by acting as an anti-inflammatory agent through increased IL-10 and decreased IL6/IL-10 ratio, and also improves cellular immunity through increased CD4/CD8 ratio [

81]. Few studies have investigated the efficacy of alfacalcidol as an adjunct to insulin therapy in the treatment of T1DM. Hovewer, a randomized controlled trials confirmed that alfacalcidol (at 0.5 ug/day for six months) can safely preserve β-cell function in newly diagnosed T1DM in children [

82].

Unfortunately, in T1DM, the potential benefits of supplementation with vitamin D or analogues would be focused on preventing the onset of the disease rather than treating it, since the destruction of β-cells is irreversible. Indeed, as mentioned above, several randomised controlled trials in the last decade have shown that vitamin D supplementation, especially as cholecalciferol, appears to preserve residual β-cell function and improve glycaemic control in children and adolescents with new-onset T1DM through its immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. However, future large-scale prospective trials are needed to adequately assess the role of vitamin D as an adjuvant treatment in T1DM.

7. Conclusions

Interestingly, both the prevalence of T1DM and vitamin D deficiency are increasing worldwide and are becoming a serious public health problems. Accumulating data over the past decades suggest that vitamin D status is involved in the pathogenesis of T1DM. In fact, many researchers have found that vitamin D deficiency is more prevalent in children/adolescents with new-onset T1DM than in healthy individuals. Vitamin D is now known to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effect based on the control of gene transcription, which is crucial for maintenance self-tolerance. Therefore, vitamin D deficiency should be considered as an important environmental factor for the development of T1DM.

On the other hand, results from long-term follow-up studies in children suggest that there is no association between vitamin D status before diagnosis and the occurrence of T1DM later in life. In addition, the potential role of vitamin D as an adjuvant therapy in T1DM remains inconclusive. Indeed, the variability of results in human trials is generally frustrating, and at best has a short-term positive effect on newly diagnosed T1DM patients. Most of the researchers conclude their papers by pointing out that large-scale prospective randomized controlled trials are urgently needed to definitively establish the role of vitamin D in T1DM. Discrepancies in clinical outcomes have been attributed to a variety of reasons, including heterogeneity in the design or population studied, as well as different formulations and doses of vitamin D used, the duration of different trials, and, in many cases, small sample sizes in the studies.

We believe that the fact that interventional studies generally have better results in patients newly diagnosed with diabetes should not be surprising. This should lead us to believe that the weakness of the aforementioned interventional studies does not lie in the heterogeneity of their characteristics, but rather in their relationship with functional or residual β-cell mass. To date, all intervention studies have been carried out in the clinical phase of T1DM, whereas it would be desirable to be able to do so in the early stages of the autoimmune process (pre-diabetes). In other words, the efforts of the desired randomised controlled trials should also be directed towards obtaining biomarkers that can detect the onset of autoimmune insulitis and, in these precise circumstances, initiate vitamin D or analogues supplementation in addition to insulin treatment. This could possibly slow down or prevent the autoimmune process from continuing its progressive course and, as far as possible, avoid reaching the clinical and irreversible phase of the disease.

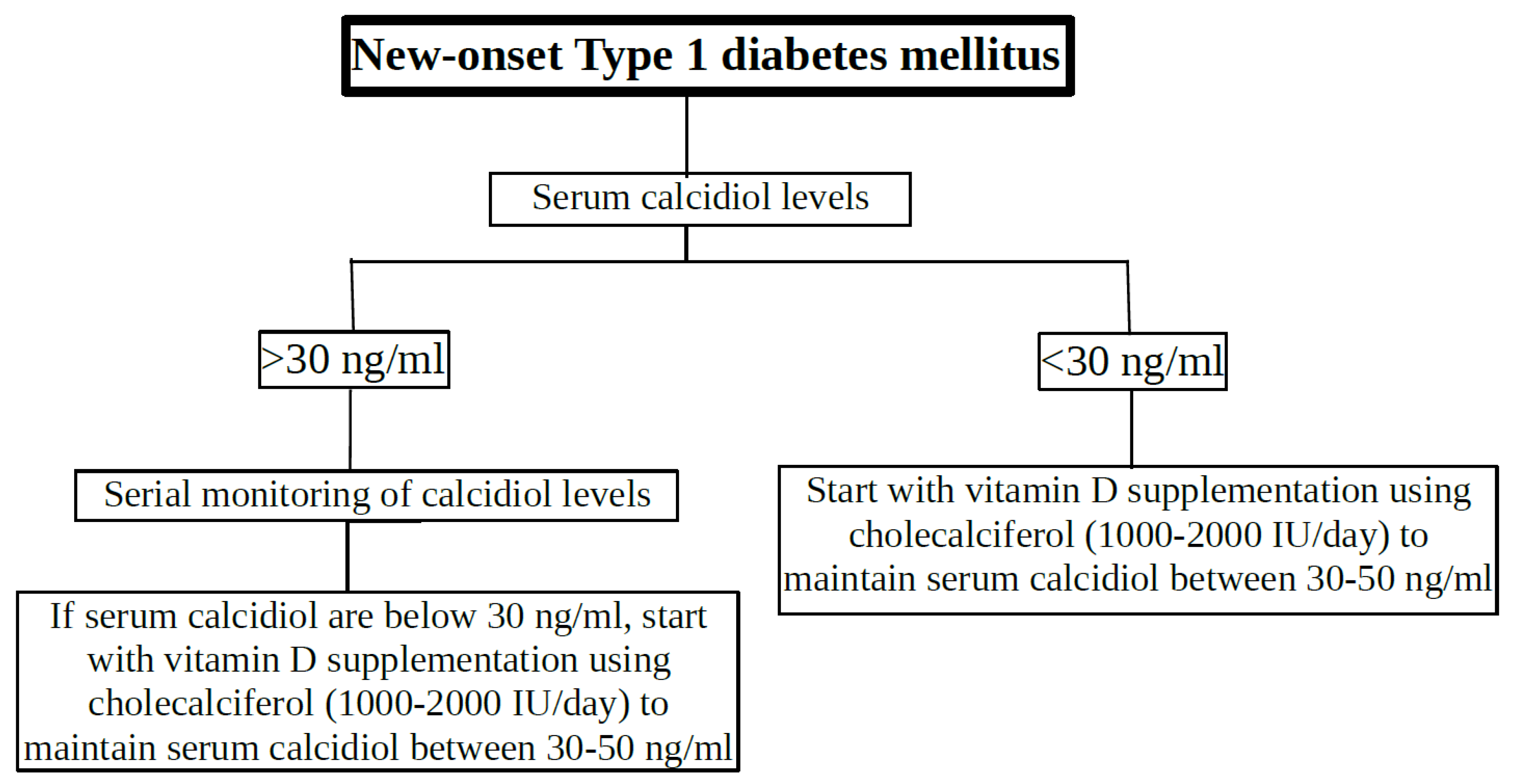

In the meantime, we would suggest a protocol for vitamin D supplementation in children and adolescents with new-onset T1DM based on the data in this narrative review (

Figure 3). Obviously, serum calcidiol levels would be measured in all newly diagnosed T1DM patients. If calcidiol levels are less than 30 ng/ml, they should receive cholecalciferol supplementation (1000 to 2000 IU/day) to maintain serum calcidiol concentration between 30-50 ng/ml (previously defined as optimal vitamin D levels). Patients with serum calcidiol concentrations above 30 ng/mL at the onset of diabetes should be monitored with serial calcidiol concentrations and cholecalciferol supplementation should be initiated if serum calcidiol concentrations are below 30 ng/mL. Cholecalciferol supplementation should be continued for at least one year to ensure optimal vitamin D benefit. Of course, residual β-cell function (fasting plasma C-peptide leves), glycaemic control (HbA1c levels and/or fasting plasma glucose), T1DM-associated autoantibodies (islet autoantibodies) and exogenous insulin requirements from diagnosis should be monitored periodically, together with vitamin D (calcidiol) levels.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article (none declared).

Ethical Approval

Not applicable (this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors)

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article (none declared).

Contribution Statement

TDT and FGV participated in study design, data collection and analysis. Both authors participated in manuscript preparation and approved its final version.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from

the corresponding author on reasonable request.

List of Abbreviation

| 25(OH)D |

25-hydroxicholecalciferol. |

| 1,25(OH)2D |

1,25-hydroxicholecalciferol |

| APCs |

antigen-presenting cells |

| anti-IA2 |

antibodies to insulinoma-associated antigen-2 |

| CD8+ T cells |

cytotoxic T cells |

| DCs |

dendritic cells |

| DHA |

docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA |

eicosapentaenoic acid |

| GAD65 |

antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase |

| HLA |

human leukocyte antigen |

| IAAs |

anti-insulin antibodies |

| ICAs |

antibodies against insulin-producing islet cells |

| IFN-γ |

interferon-γ |

| IL |

interleukin |

| MARRS |

membrane-associated, rapid response steroid-binding protein |

| NK |

natural killer cells |

| PPIs |

proton pump inhibitor |

| PUFAs |

polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RXR |

retinoid-X receptor. |

| T1DM |

Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| Th1 |

CD4+ type 1 T helper |

| Th2 |

CD4+ type 2 T helper |

| Th17 |

CD4+ type 17 T helper |

| Treg |

CD4+ T regulatory cells |

| TNF-α |

tumour necrosis factor α |

| VDR |

vitamin D receptors |

| VDBP |

Vitamin D-binding protein. |

| VDRE |

Vitamin D response elements. |

| ZnT8 |

antibodies to zinc transporter 8 |

References

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Michels, A.W. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2014, 383, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.C.; Harjutsalo, V.; Rosenbauer, J.; Neu, A.; Cinek, O.; Skrivarhaug, T.; Rami-Merhar, B.; Soltesz, G.; Svensson, J.; Parslow, R.C. Trends and cyclical variation in the incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in 26 European centres in the 25 year period 1989–2013: a multicentre prospective registration study. Diabetologia. 2019, 62, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Huang, Y.C.; Qiao, Y.C.; Ling, W.; Pan, Y.H.; Geng, L.J.; Xiao, J.L.; Zhang, X.X.; Zhao, H.L. Climates on incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes mellitus in 72 countries. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.Y.; Shin, S.; Han, S.N. Multifaceted Roles of Vitamin D for Diabetes: From Immunomodulatory Functions to Metabolic Regulations. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Song, A.; Jin, Y.; Xia, Q.; Song, G.; Xing, X. A dose–response meta-analysis between serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, B.; Piazza, M.; Sandri, M.; Mazzei, F.; Maffeis, C.; Boner, A.L. Vitamin D at the onset of type 1 diabetes in Italian children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2014, 173, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Sun, C. Lower serum 25 (OH) D concentrations in type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 108, e71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zubeidi, H.; Leon-Chi, L.; Newfield, R.S. Low vitamin D level in pediatric patients with new onset type 1 diabetes is common, especially if in ketoacidosis. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016; 17,1592–1598.

- Rasoul, M.A.; Al-Mahdi, M.; Al-Kandari, H.; Dhaunsi, G.S.; Haider, M.Z. Low serum vitamin-D status is associated with high prevalence and early onset of type-1 diabetes mellitus in Kuwaiti children. BMC. Pediatr. 2016, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, M.; Pylli, M.; Giannakou, K. Vitamin D Deficiency as a Possible Cause of Type 1 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents up to 15 Years Old: A Systematic Review. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2022, 18, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.; Warnants, M.; Vollmuth, V.; Winkler, C.; Weiss, A.; Ziegler, A.G.; Lundgren, M.; Elding Larsson, H.; Kordonouri, O.; von dem Berge, T.; et al. Vitamin D insufficiency in infants with increased risk of developing type 1 diabetes: a secondary analysis of the POInT Study. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2024, 8, e002212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chai, M.; Lin, M. Proportion of vitamin D deficiency in children/adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, R.; Misra, M. Extra-Skeletal Effects of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Proença, L.; Delgado, A.S.; Mendes, J.J. Vitamin D deficiency and oral health: a comprehensive review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.Y.; Shin, S.; Han, S.N. Multifaceted Roles of Vitamin D for Diabetes: From Immunomodulatory Functions to Metabolic Regulations. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Atkins, A.; Downes, M.; Wei, Z. Vitamin D in Diabetes: Uncovering the Sunshine Hormone’s Role in Glucose Metabolism and Beyond. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J. ; Wan. Y.; Xia. X.; Pan. J.; Gu. W.; Li. M. Serum vitamin D deficiency in children and adolescents is associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 0, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, J.M.; Lee, H.S.; Frederiksen, B.; Erlund, I.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J.; Lernmark, Å.; Simell, O.; Toppari, J.; Rewers, M.; et al. Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration and Risk of Islet Autoimmunity. Diabetes. 2018, 67: 146-154.

- Rasoul, M.A.; Haider, M.Z.; Al-Mahdi, M.; Al-Kandari, H.; Dhaunsi, G.S. Relationship of four vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with type 1 diabetes mellitus susceptibility in Kuwaiti children. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Bishop, E.M.; Harrison, S.R.; Swift, A.; Cooper, S.C.; Dimeloe, S.K.; Raza, K.; Hewison, M. Autoimmune disease and interconnections with vitamin D. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar]

- Hii, C.S.; Ferrante, A. The Non-Genomic Actions of Vitamin D. Nutrients. 2016, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmijewski, M.A. Nongenomic Activities of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschou, S.A.; Papadopoulou-Marketou, N.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C. On type 1 diabetes mellitus pathogenesis. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcox, A.; Gillespie, K.M. Histology of Type 1 Diabetes Pancreas. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2016, 1433, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, J.A.; Valdes, A.M. Genetics of the HLA region in the prediction of type 1 diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2011, 11, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pociot, F.; Lernmark, A. Genetic risk factorsk for type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2016, 387, 2331–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.M.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, F.; Wang, C.Y. Implication of epigenetic factors in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021, 134, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorena, K.; Michalska, M.; Kurpas, M.; Jaskulak, M.; Murawska, A.; Rostami, S. Environmental Factors and the Risk of Developing Type 1 Diabetes—Old Disease and New Data. Biology 2022, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.M.; Miller, M.; Seifert, J.A.; Frederiksen, B.; Kroehl, M.; Rewers, M.; Norris, J.M. The effect of childhood cow’s milk intake and HLA-DR genotype on risk of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: The diabetes autoimmunity study in the young. Pediatr. Diabetes 2015, 16, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, V.; Plachy, L.; Pruhova, S.; Sumnik, Z. Dietary Components in the Pathogenesis and Prevention of Type 1 Diabetes in Children. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wong, F.S.; Wen, L. Type 1 diabetes and gut microbiota: Friend or foe? Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 98, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savastio, S.; Cadario, F.; Genoni, G.; Bellomo, G.; Bagnati, M.; Secco, G.; Picchi, R.; Giglione, E.; Bona, G. Vitamin D Deficiency and Glycemic Status in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. PloS ONE 2016, 11, e0162554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaseminejad-Raeini, A.; Ghaderi, A.; Sharafi, A.; Nematollahi-Sani, B.; Moossavi, M.; Derakhshani, A.; Sarab, G.A. Immunomodulatory actions of vitamin D in various immune-related disorders: a comprehensive review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. 950465.

- Yu, J.; Sharma, P.; Girgis, C.M.; Gunton, J.E. Vitamin D and Beta Cells in Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Z. Epigenetic alterations in cellular immunity: new insights into autoimmune diseases. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017, 41, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Toni, G.; Tascini, G.; Santi, E.; Berioli, M.G.; Principi, N. Environmental Factors Associated With Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMarca, V.; Gianchecchi, E.; Fierabracci, A. Type 1 Diabetes and Its Multi-Factorial Pathogenesis: The Putative Role of NK Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosenko, J.M.; Skyler, J.S.; Palmer, J.P.; Krischer, J.P.; Yu, L.; Mahon, J.; Eisenbarth, G. The prediction of type 1 diabetes by multiple autoantibody levels and their incorporation into an autoantibody risk score in relatives of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2615–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, M.; Ricordi, C.; Sanchez, J.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Padilla, N.; Fuenmayor, V.; Chavez, C.; Alvarez, A.; Baidal, D.; Alejandro, R.; et al. Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.P.; Song, Y.X.; Zhu, T.; Gu, W.; Liu, C.W. Progress in the Relationship between Vitamin D Deficiency and the Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Children. J Diabetes Res. 2022, 2022, 5953562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, K.R.; Lundberg, R.L.; Jasrotia, A.; Maranda, L.S.; Thompson, M.J.; Barton, B.A.; Alonso, L.C.; Nwosu, B.U. A predictive model for lack of partial clinical remission in new-onset pediatric type 1 diabetes. PloS One. 2017, 12, e0176860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonolleda, M.; Murillo, M.; Vázquez, F.; Bel, J.; Vives-Pi, M. Remission Phase in Paediatric Type 1 Diabetes: New Understanding and Emerging Biomarkers. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2017, 88, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankers, W.; Colin, E.M.; van Hamburg, J.P.; Lubberts, E. Vitamin D in autoimmunity: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic potential. Front. Immunol. 2017, 7, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prietl, B.; Treiber, G.; Pieber, T.R.; Amrein, K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2502–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyprian, F.; Lefkou, E.; Varoudi, K.; Girardi, G. Immunomodulatory Effects of Vitamin D in Pregnancy and Beyond. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, D.; Baci, D.; Kustrimovic, N.; Lanzo, N.; Patera, B.; Tanda, M.L.; Piantanida, E.; Mortara, L. How Does Vitamin D Affect Immune Cells Crosstalk in Autoimmune Diseases? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdo-Torres, D.; Andreu, S.; Caballero, O.; Hernández-Ruiz, I.; Ripa, I.; Bello-Morales, R.; López-Guerrero, J.A. Immune Modulatory Effects of Vitamin D on Herpesvirus Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kwong, J.S.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Sun, F.; Niu, Y.; Du, L. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:2–10.

- Manousaki, D.; Harroud, A.; Mitchell, R.E.; Ross, S.; Forgetta, V.; Timpson, N.J.; Smith, G.D.; Polychronakos, C.; Richards, J.B. Vitamin D levels and risk of type 1 diabetes: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003536. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, L.; Sutherland, J.; Zhou, A.; Hyppönen, E. Vitamin D and Type 1 Diabetes Risk: A. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Genetic Evidence. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, N.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Yang, T. Association between two polymorphisms (FokI and BsmI) of vitamin D receptor gene and type 1 diabetes mellitus in Asian population: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibian, N.; Amoli, M.M.; Abbasi, F.; Rabbani, A.; Alipour, A.; Sayarifard, F.; Rostami, P.; Dizaji, S.P.; Saadati, B.; Setoodeh, A. Role of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacological Rep. 2019;71:282–288.

- Ran, Y.; Hu, S.; Yu, X.; Li, R. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism with type 1 diabetes mellitus risk in children: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 202, 100. e26637.

- Sørensen, I.M.; Joner, G.; Jenum, P.A.; Eskild, A.; Torjesen, P.A.; Stene, L.C. Maternal serum levels of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Diabetes 2012, 61, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.E.; Reinert, L.; Kinnunen, L.; Harjutsalo, V.; Koskela, P.; Surcel, H.M.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Tuomilehto, J. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level during early pregnancy and type 1 diabetes risk in the offspring. Diabetologia. 2012, 55, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granfors, M.; Augustin, H.; Ludvigsson, J.; Brekke, H.K. No association between use of multivitamin supplement containing vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of Type 1 Diabetes in the child. Pediatr. Diabetes 2016, 17, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvis, K.; Aronsson, C.A.; Liu, X.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J.; Tamura, R.; Lernmark, Å.; Rewers, M.; Hagopian, W.; She, J.X.; et al. Maternal dietary supplement use and development of islet autoimmunity in the offspring: TEDDY study. Pediatr.Diabetes. 2019, 20, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Y.; Zhang, W.G.; Chen, J.J.; Zhang, Z.L.; Han, S.F.; Qin, L.Q. Vitamin D intake and risk of type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3551–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipitis, C.S.; Akobeng, A.K. Vitamin D supplementation in early childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raab, J.; Giannopoulou, E.Z.; Schneider, S.; Warncke, K.; Krasmann, M.; Winkler, C.; Ziegler, A.G. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pre-type 1 diabetes and its association with disease progression. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.; Brady, H.; Yin, X.; Seifert, J.; Barriga, K.; Hoffman, M.; Bugawan, T.; Barón, A.E.; Sokol, R.J.; Eisenbarth, G.; et al. No association of vitamin D intake or 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in childhood with risk of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: The diabetes autoimmunity study in the young (DAISY). Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, M.; Mykkänen, J.; Koskinen, M.; Simell, V.; Veijola, R.; Hyöty, H.; Ilonen, J.; Knip, M.; Simell, O.; Toppari, J. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in children progressing to autoimmunity and clinical type 1 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachapati, K.; Adams, D.; Bednar, K.; Ridgway, W.M. The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse as a model of human type 1 diabetes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 933, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rak, K.; Bronkowska, M. Immunomodulatory Effect of Vitamin D and Its Potential Role in the Prevention and Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus—A Narrative Review. Molecules. 2018, 24, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, M.A.; Sato, M.N.; Finazzo, C.; Duarte, A.J.; Dib, S.A. Effect of cholecalciferol as adjunctive therapy with insulin on protective immunologic profile and decline of residual β-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiber, G.; Prietl, B.; Fröhlich-Reiterer, E.; Lechner, E.; Ribitsch, A.; Fritsch, M. Cholecalciferol supplementation improves suppressive capacity of regulatory T-cells in young patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus—A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 161, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjiyar, R.P.; Dayal, D.; Attri, S.V.; Sachdeva, N.; Sharma, R.; Bhalla, A.K. Sustained serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations for one year with cholecalciferol supplementation improves glycaemic control and slows the decline of residual β cell function in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 2018, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Dayal, D.; Sachdeva, N.; Attri, S.V. Effect of 6-months’ vitamin D supplementation on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes: A case control interventional study. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 29, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Biswal, N.; Bethou, A.; Rajappa, M.; Kumar, S.; Vinayagam, V. Does Vitamin D Supplementation Improve Glycaemic Control In Children With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus? -A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, SC15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perchard, R.; Magee, L.; Whatmore, A.; Ivison, F.; Murray, P.; Stevens, A. A pilot interventional study to evaluate the impact of cholecalciferol treatment on HbA1c in type 1 diabetes (T1D). Endocr. Connect. 2017, 6, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liao, L.; Yan, X.; Huang, G.; Lin, J.; Lei, M. Protective effects of 1-alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 on residual beta-cell function in patients with adult-onset latent autoimmune diabetes (LADA). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2009, 25, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadario, F.; Pozzi, E.; Rizzollo, S.; Stracuzzi, M.; Beux, S.; Giorgis, A.; Carrera, D.; Fullin, F.; Riso, S.; Rizzo, A.M.; et al. Vitamin D and ω-3 Supplementations in Mediterranean Diet During the 1st Year of Overt Type 1 Diabetes: A Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.; Daya, L.D.; Sachdeva, N.; Attri, S.V.; Gupta, V.K. Combination therapy with lansoprazole and cholecalciferol is associated with a slower decline in residual beta-cell function and lower insulin requirements in children with recent onset type 1 diabetes: results of a pilot study. Einstein (São Paulo). 2022; 20, eAO0149.

- Pinheiro, M.M.; Pinheiro, F.M.M.; de Arruda, M.M.; Beato, G.M.; Verde, G.A.C.L.; Bianchini, G.; Casalenuovo, P.R.M.; Argolo, A.A.A.; de Souza, L.T.; Pessoa, F.G.; et al. Association between sitagliptinplus vitamin D3 (VIDPP-4i) use and clinical remission in patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes: a retrospectivecase-control study. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 67, e000652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, B.U.; Parajuli, S.; Jasmin, G.; Fleshman, J.; Sharma, R.B.; Alonso, L.C.; Lee, A.F.; Barton, B.A. Ergocalciferol in new-onset type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. J. Endocrine. Soc. 2022, 6:bvab179.

- Federico, G.; Focosi, D.; Marchi, B.; Randazzo, E.; De Donno, M.; Vierucci, F. Administering 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in vitamin D-deficient young type 1A diabetic patients reduces reactivity against islet autoantigens. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, C.; Pitocco, D.; Napoli, N.; di Stasio, E.; Maggi, D.; Manfrini, S. No protective effect of calcitriol on beta-cell function in recent-onset type 1 diabetes: The IMDIAB XIII trial. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1962–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, M.; Kaupper, T.; Adler, K.; Foersch, J.; Bonifacio, E.; Ziegler, A.G. No effect of the 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on beta-cell residual function and insulin requirement in adults with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizka, A.; Setiati, S.; Harimurti, K.; Sadikin, M.; Mansur, I.G. Effect of Alfacalcidol on Inflammatory markers and T Cell Subsets in Elderly with Frailty Syndrome: A Double Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Med. Indones. 2018, 50, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ataie-Jafari, A.; Loke, S.C.; Rahmat, A.B.; Larijani, B.; Abbasi, F.; Leow, M.K. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of alphacalcidol on the preservation of beta cell function in children with recent onset type 1 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).