Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Objectives

- Systematically analyze the root causes of failure cases through Safety-I methodology and identify deficiencies in current safety management.

- Define ’flight crew’s resilient behavior’ based on Safety-II methodology and propose methods to transform failure cases into resilient success cases.

- Transform the safety management paradigm from ’failure prevention’ to ’success expansion’ through integrated application of both methodologies, thereby enhancing organizational safety culture.

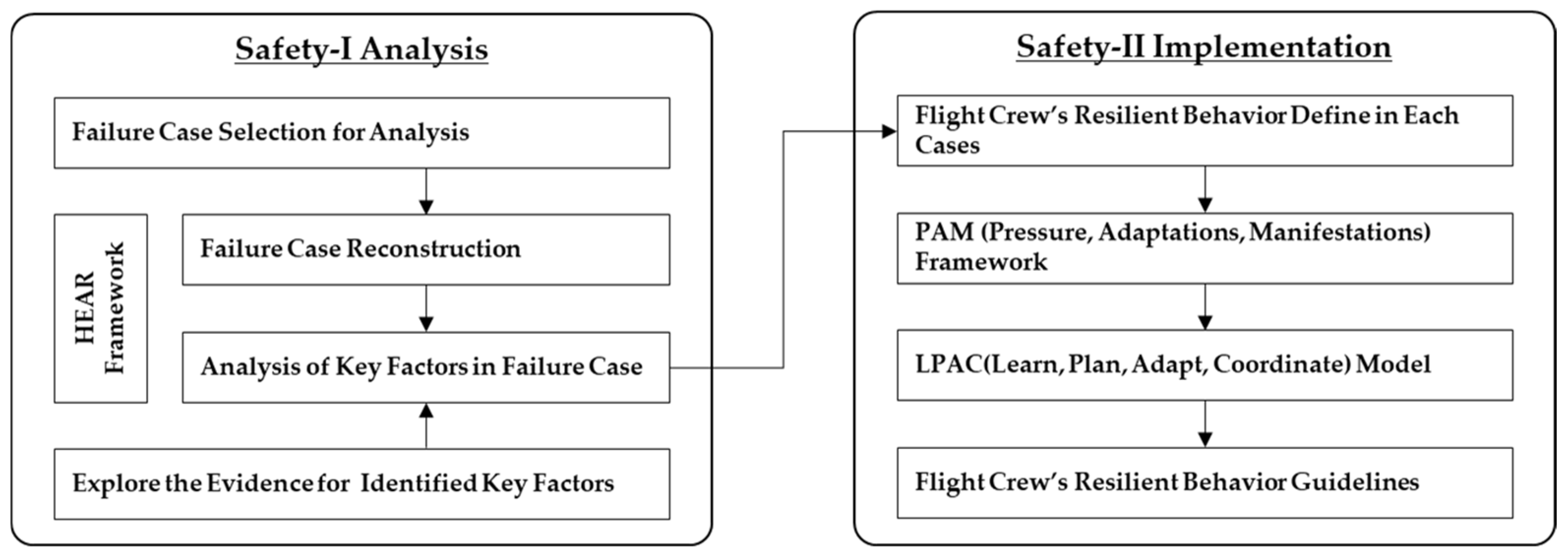

1.3. Research Process

2. Development of Safety Management Systems and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Evolution of Safety Management Concepts

2.2. Modern Safety Management Paradigm Shift

2.2.1. Characteristics and Limitations of Safety-I

2.2.2. Emergence and Core Characteristics of Safety-II

2.2.3. Integration Possibility of Safety-I and Safety-II

2.3. Research Methodology

2.3.1. Safety-I Analysis through HEAR (Human Error Analysis and Reduction) Framework

2.3.2. LPAC (Learn, Plan, Adapt, Coordinate) Model and PAM (Pressures, Adaptations, Manifestations) Framework for Safety-II Implementation

2.3.3. Case Selection Criteria

3. Analysis of Failure Cases and Safety Management Behavior through Safety-I Methodology

3.1. Analysis of Study Cases

| Category | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Type | FMS Operation elated | Turbulence Related | Energy Management Related |

| Occurence Phase | Instrument Approach Phase | Climb Phase | Instrument Phase |

| Specific Phenomenon | Path/Altitude Deviation | Crew Injury | Approach Abort |

| Detailed Situation | Case 1-1: Safety Altitude Violation Case 1-2: Approach Path Deviation |

Altitude 16,700 feet during climb, encountered turbulence resulting in cabin crew left ankle fracture | High energy state(*) continuation resulting in unstable approach and landing abort |

| Main Cause | Lack of FMS function understanding, inappropriate manual input | Inadequate turbulence avoidance strategy formulation/execution | Inappropriate energy management strategy |

| Education/Training Related Elements | Inadequate FMS operation principle education system | Insufficient adverse weather response education | Inappropriate energy management education system |

| Organizational Related Elements | Lack of safety manager insight | Habitually repeating conventional safety education | Adherence to traditional navigation methods |

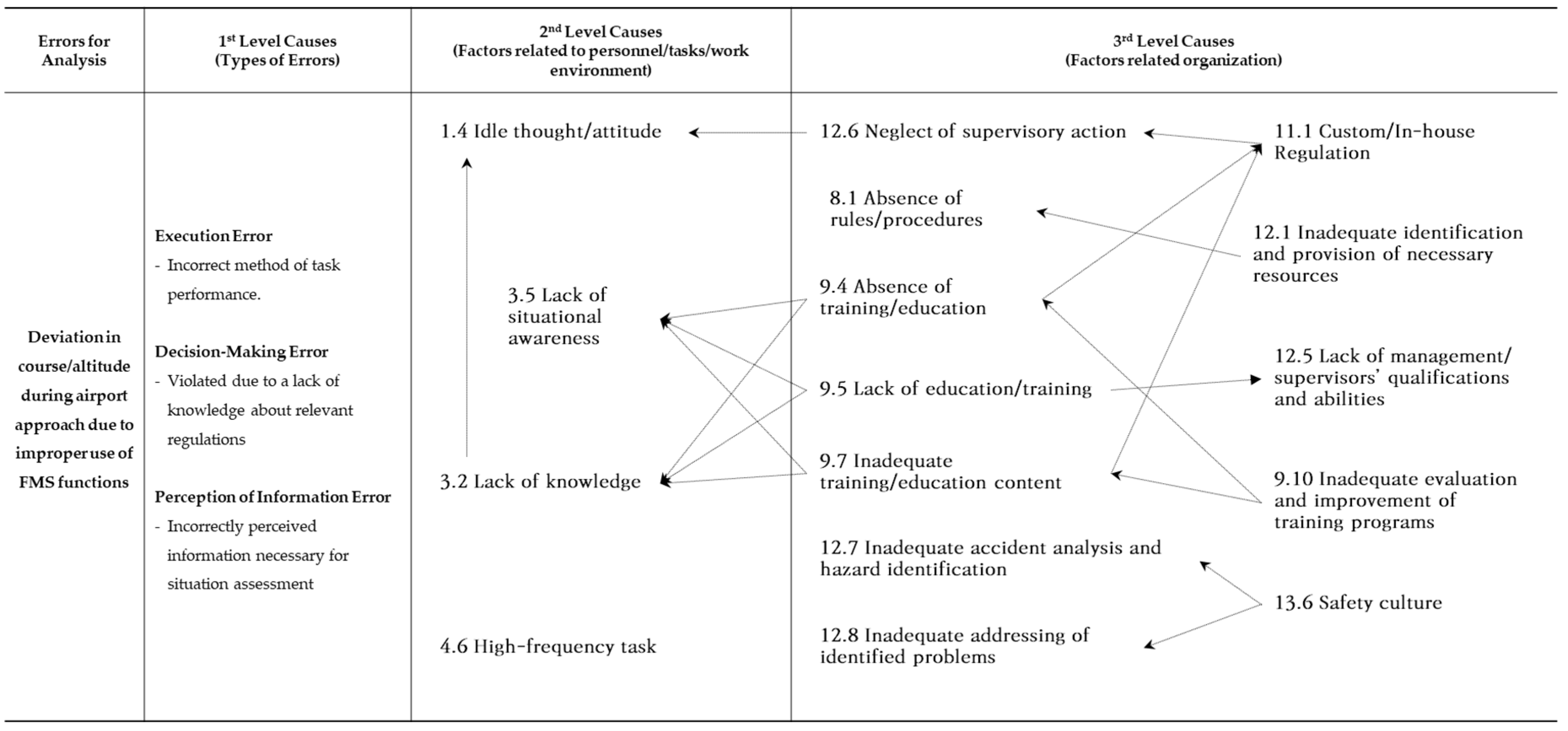

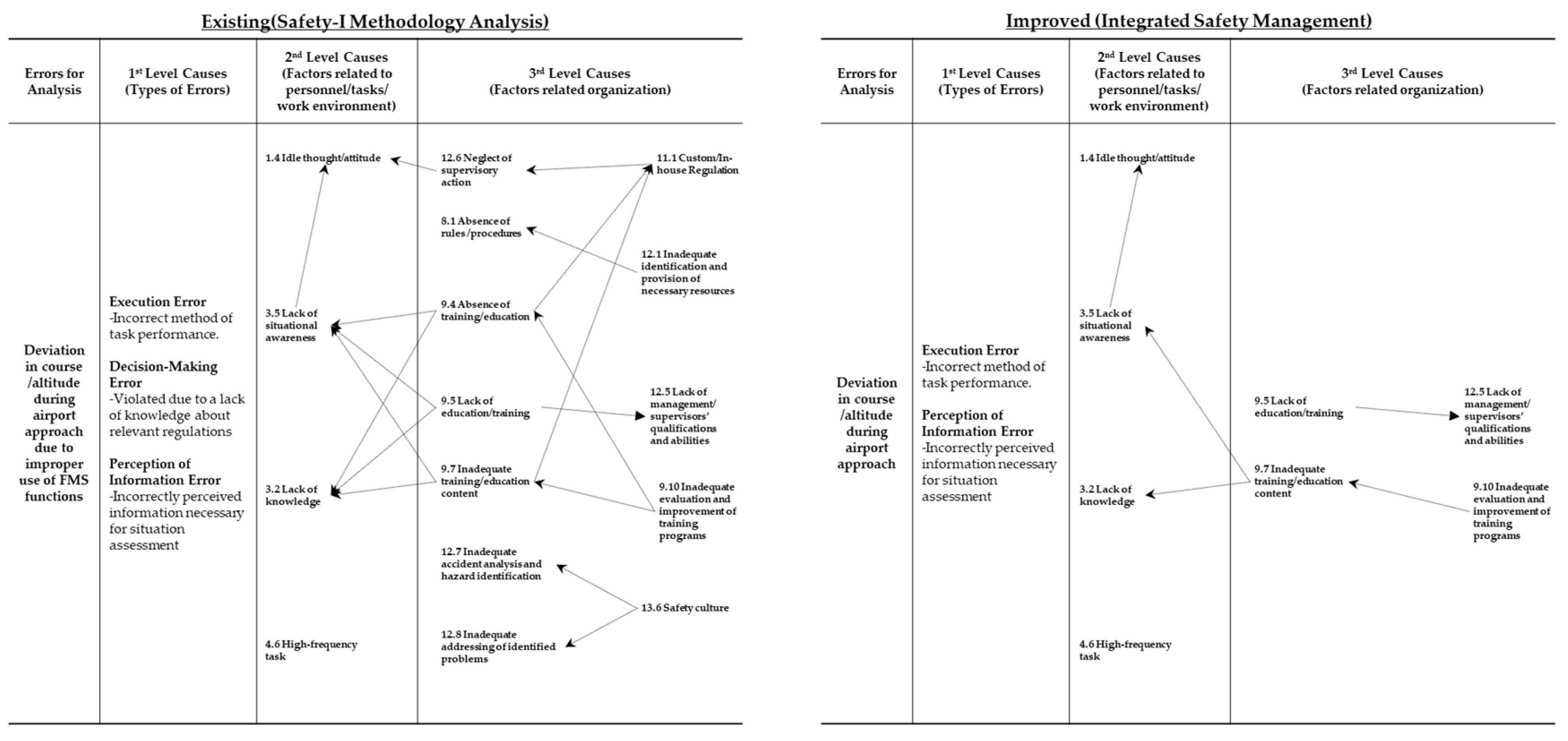

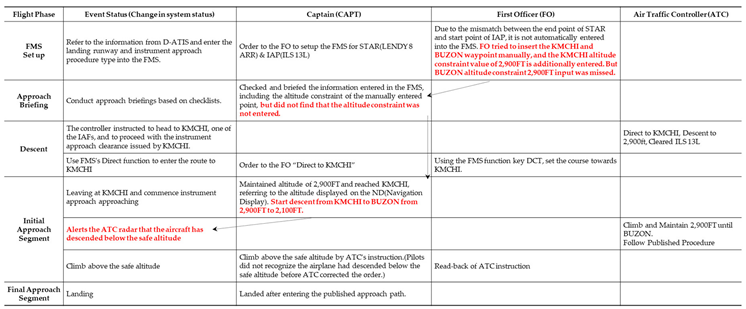

3.1.1. Path and Altitude Deviation due to Inappropriate Use of FMS Functions

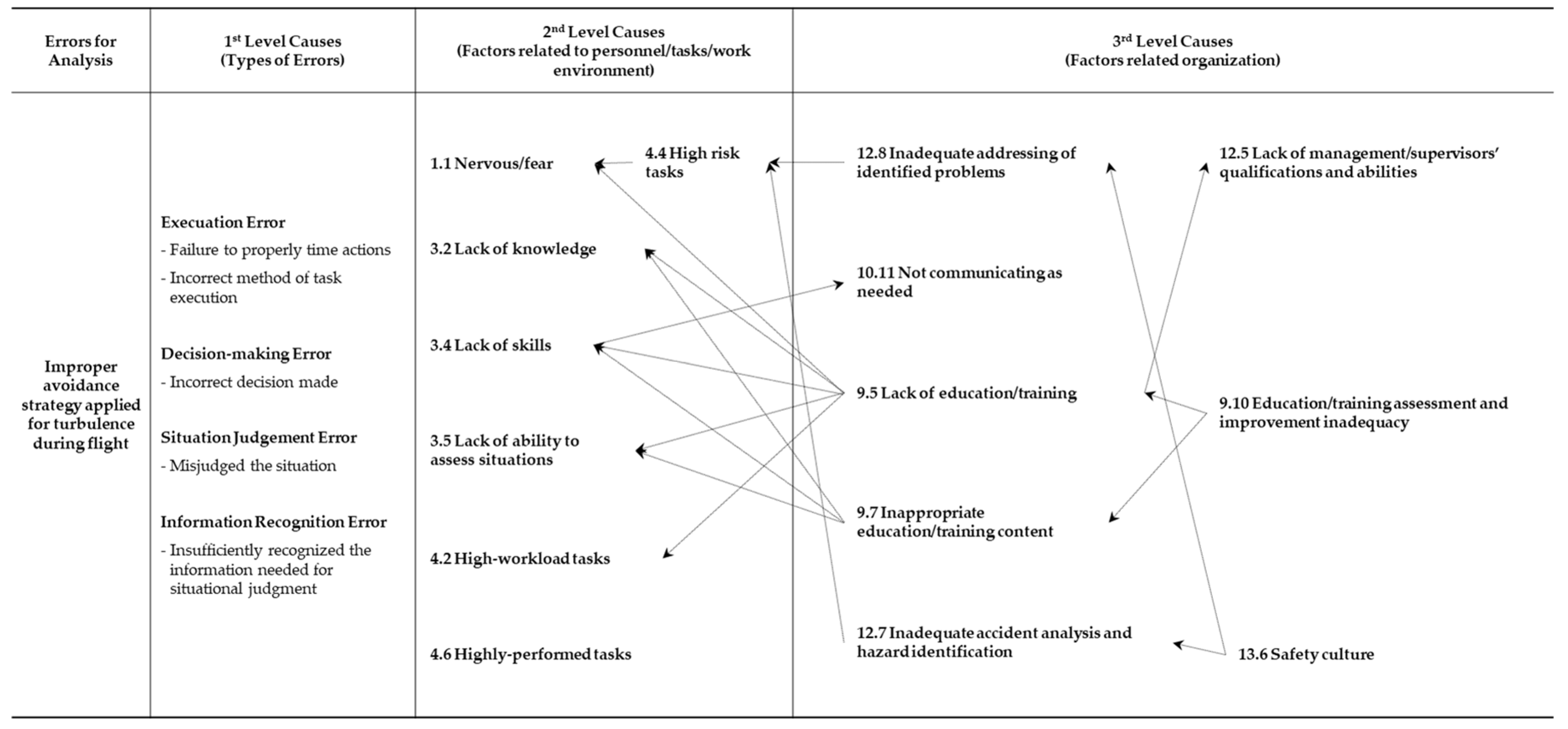

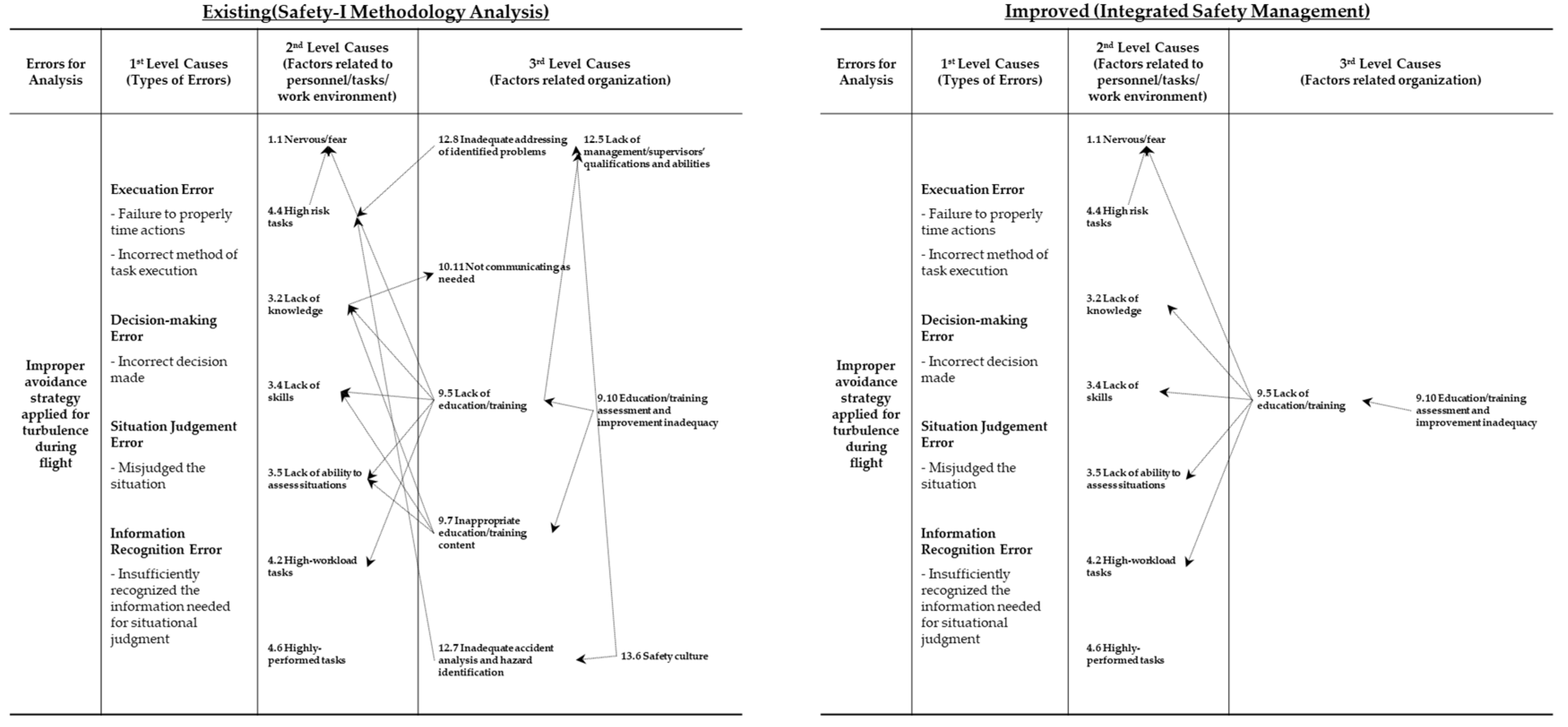

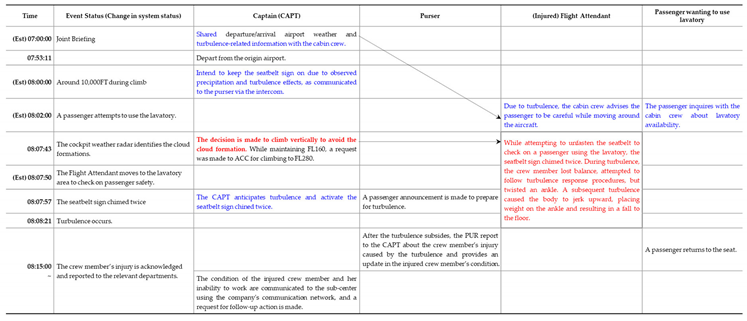

3.1.2. Crew Injury due to In-Flight Turbulence

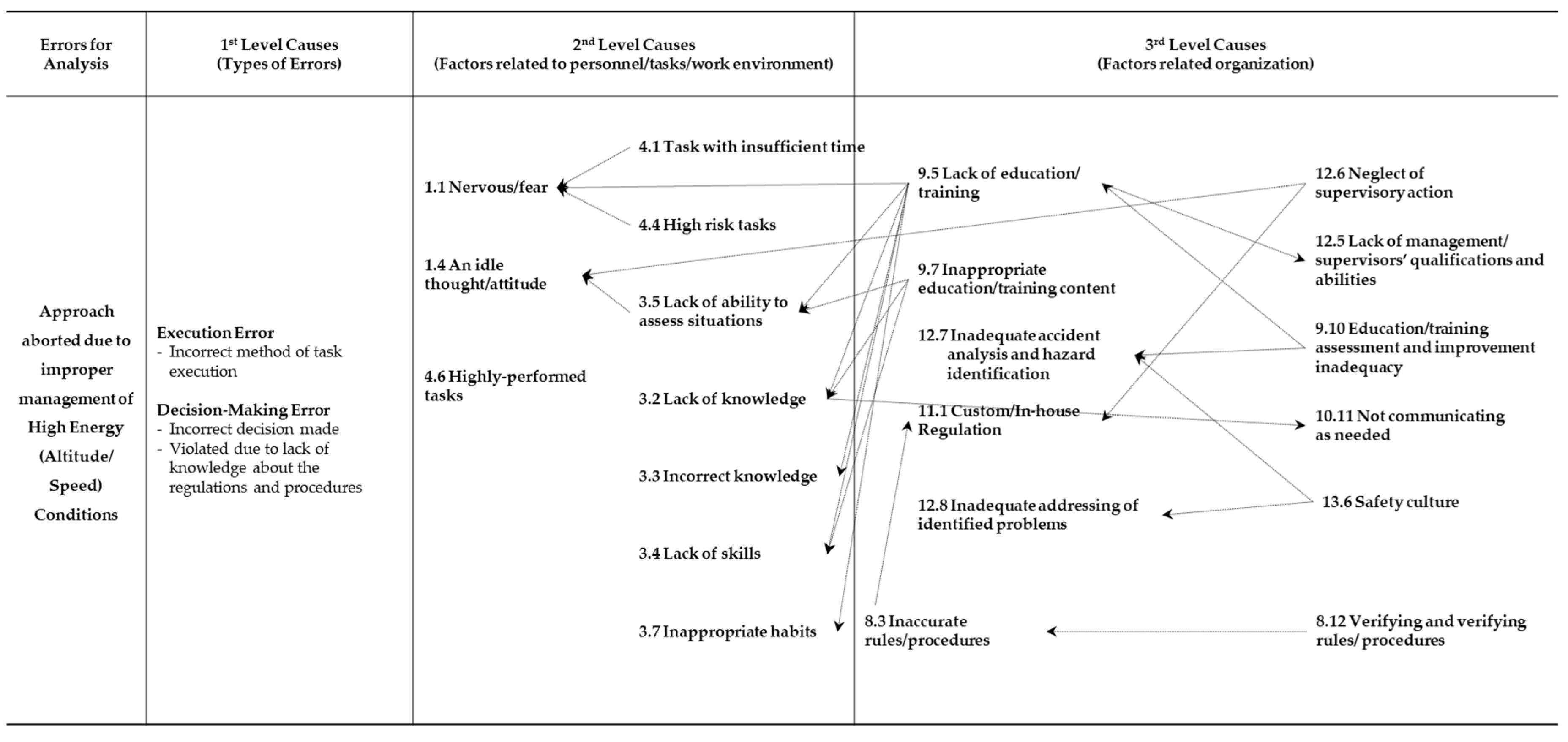

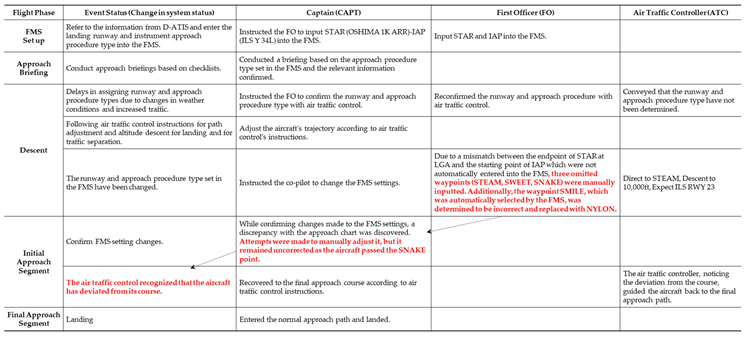

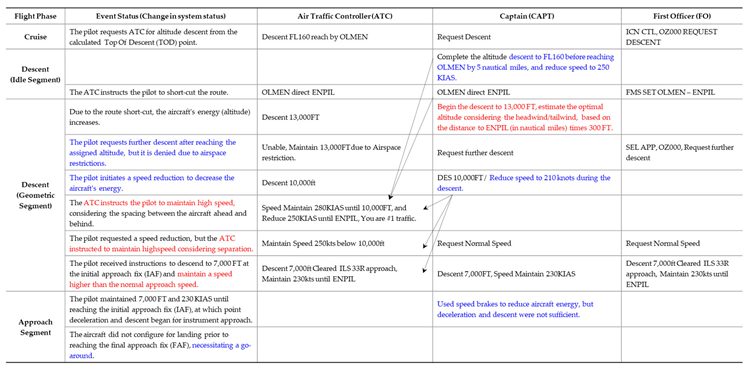

3.1.3. Approach Abort due to Aircraft High Energy during Instrument Approach

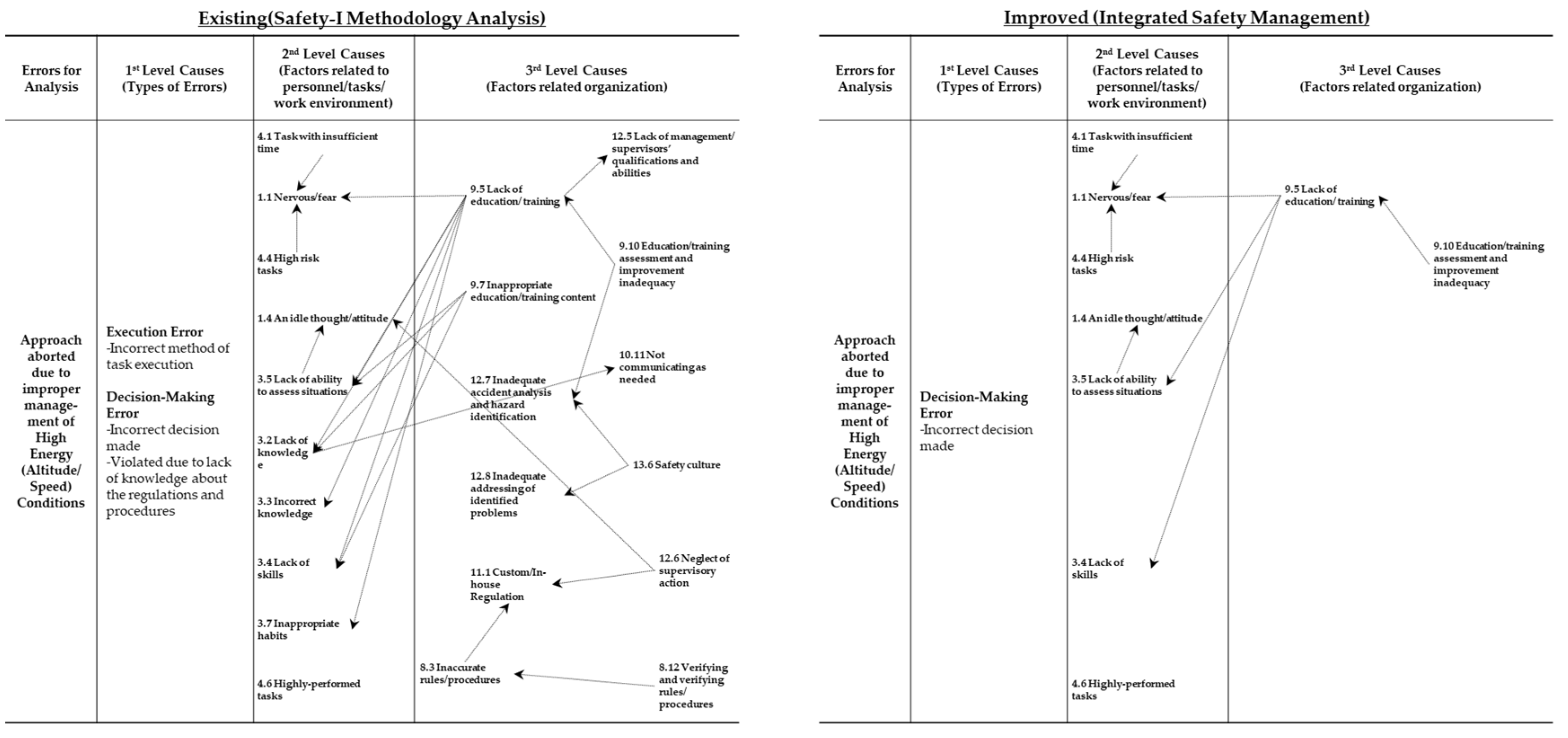

3.2. Comprehensive Analysis Results

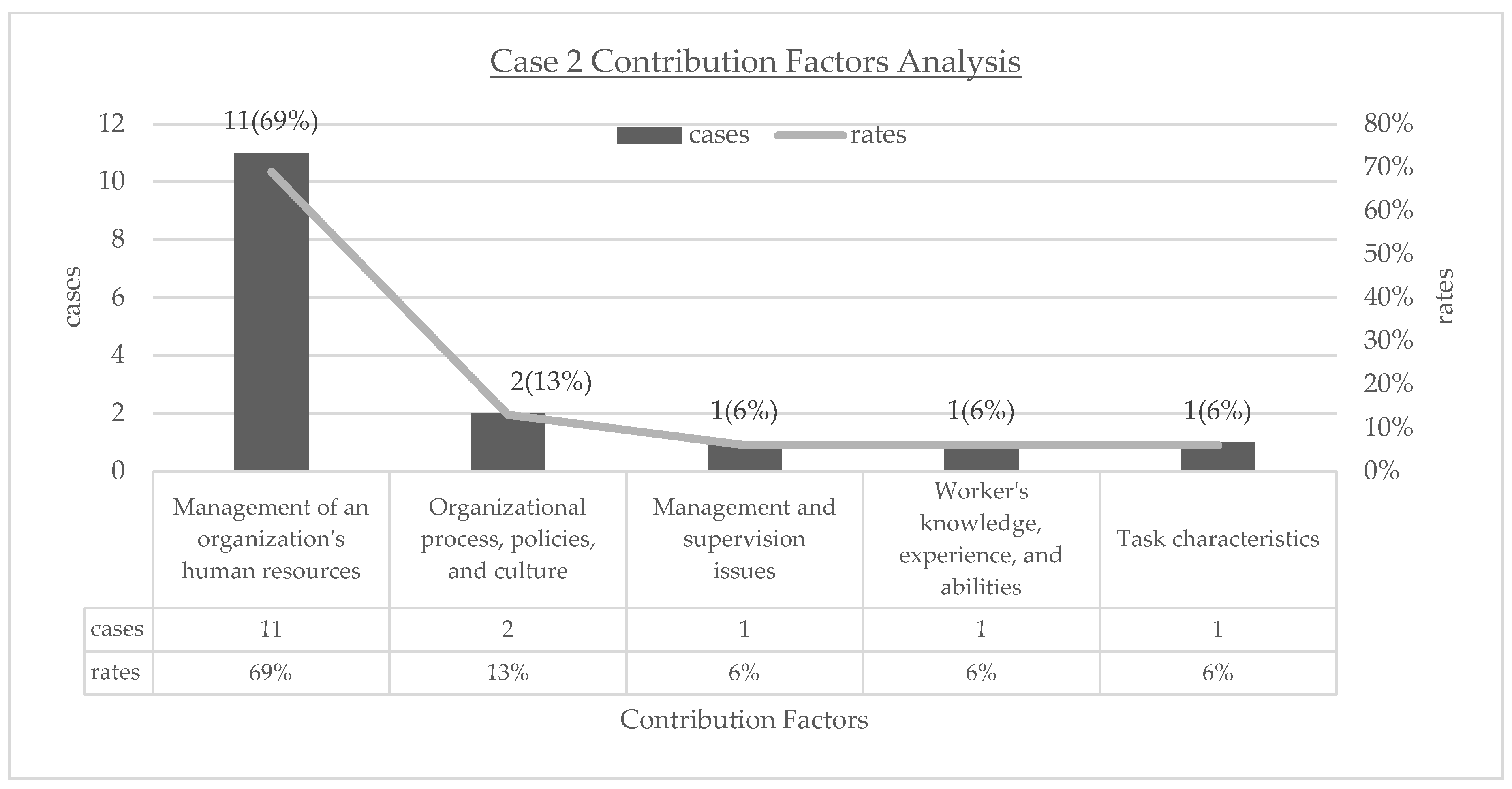

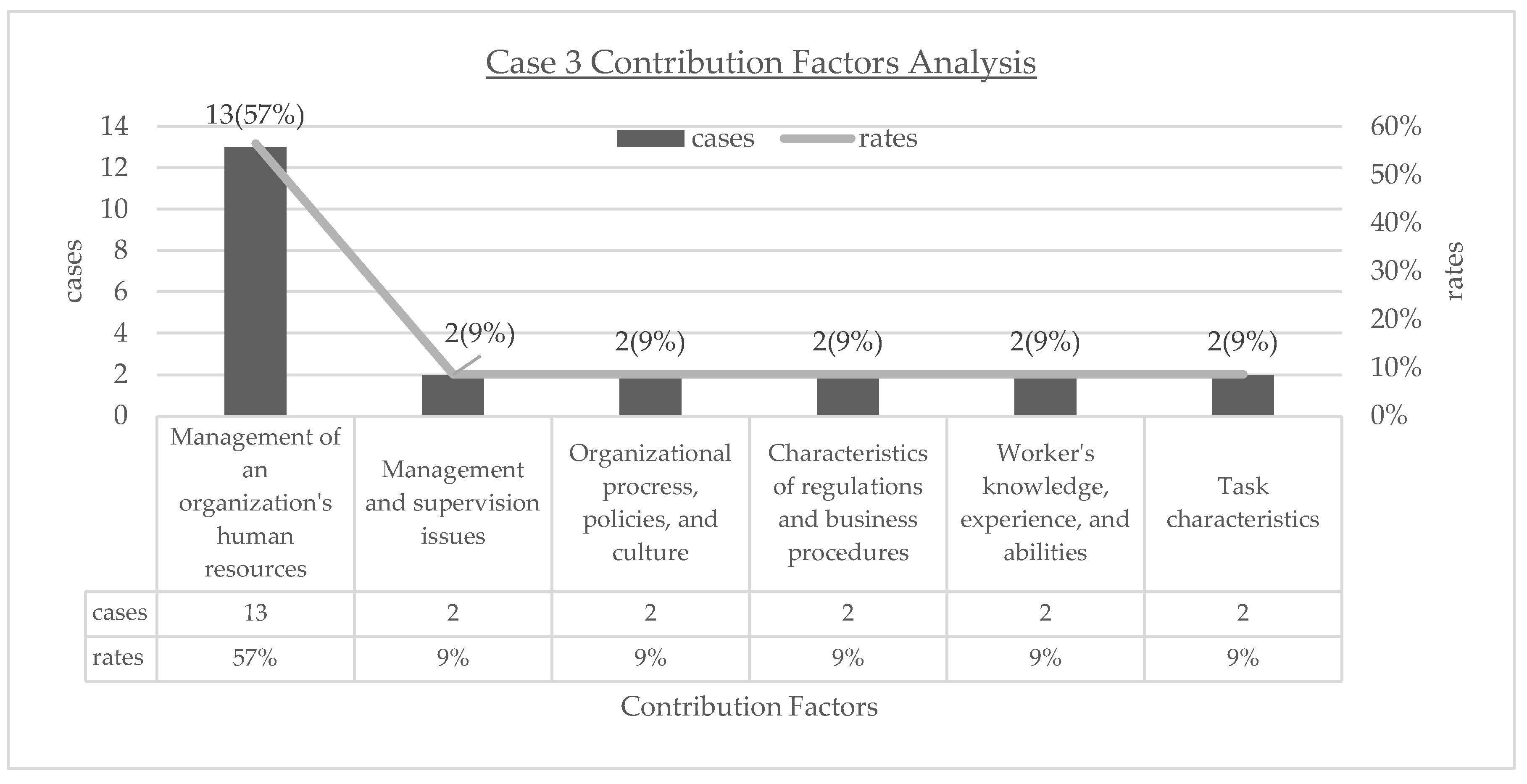

3.2.1. Contributing Factors Analysis

3.2.2. Safety Management Behavior Evaluation

4. Development of Flight Crew’s Resilient Behavior Framework

4.1. Definition of Resilient Behavior

4.2. Theoretical Basis of Resilient Behavior

4.3. Case-Specific Resilient Behavior Enhancement Methods

4.3.1. FMS Operation Resilient Behavior

- Learn: Flight crews accumulate and share knowledge based on approach procedure experiences at specific airports. Particularly, they enhance in-depth understanding of STAR and IAP relationships and systematically analyze lessons from past experiences. Regular FMS function education helps clearly understand system capabilities and limitations and develop capabilities to effectively use them in actual situations.

- Plan: During pre-flight briefing, all possible approach scenarios’ FMS setting methods are thoroughly reviewed. Particularly, using the “Secondary Flight Plan” function to pre-program alternative approach methods and discussing responses to various situations when operating to airports with high approach procedure change probability can enable systematic response even in time-pressured situations.

- Adapt: Flexibly respond in actual situations. If needed, request guidance to the final approach path from control agencies and quickly reconfigure approach procedures using FMS Database skillfully. Immediately recognize and identify the cause if path or altitude deviation is detected to take appropriate action. In this process, maintain optimal aircraft state by balancing between FMS automation functions and manual operation segments.

- Coordinate: Share and confirm procedure changes through clear and effective communication between flight crew members. Immediately inform control agencies and request cooperation if path or altitude deviation is detected. Clearly divide roles between PF(Pilot Flying) and PM(Pilot Monitoring) for effective simultaneous FMS operation and situation monitoring. Strengthen teamwork-based problem-solving through continuous situation awareness sharing.

4.3.2. Turbulence Response Resilient Behavior

- Learn: Flight crews develop in-depth knowledge of weather phenomena and weather radar interpretation. They systematically analyze and share past turbulence encounter experiences and successful response cases, and become proficient in effective use of the latest weather information systems (e.g., WSI). By developing capabilities to integratedly analyze various weather data such as weather charts, radar images, and SIGMET information, they enhance capabilities to predict and assess turbulence in advance.

- Plan: Before flight, they thoroughly analyze weather conditions along the flight route and identify potential turbulence sections to establish response strategies. Particularly, prepare alternative route and altitude options in advance and plan timing and methods for passenger safety assurance. Review turbulence intensity-specific response protocols and share response methods through pre-crew briefing. Such planning provides the basis for systematic response without time pressure when actual situations occur.

- Adapt: Assess weather conditions in real-time during flight and respond flexibly. Accurately determine turbulence location and intensity using radar data and preceding aircraft information, and execute vertical or horizontal avoidance maneuvers as needed. Prioritizing passenger safety, activate seat belt signs at appropriate times and monitor cabin safety status through close communication with cabin crew. Continuously adjust avoidance strategies according to situation changes to safely operate the aircraft.

- Coordinate: Maintain smooth communication between flight crews and cabin crews, and with control agencies. Share information about anticipated turbulence locations and intensities with cabin crew in advance and clearly communicate about potential turbulence levels and duration. Coordinate with control agencies to secure optimal altitudes and routes, and request reports from other aircraft about turbulence if needed. After turbulence encounters, immediately check for possible injuries or equipment damage and take necessary follow-up measures.

4.3.3. Energy Management Resilient Behavior

- Learn: Flight crews develop deep understanding of aircraft energy management principles and FMS energy prediction/management functions. They systematically learn the effects of energy states on flight safety. Particularly, they become proficient in methods to effectively manage the complex interactions between speed, altitude, thrust, and drag through FMS, developing capabilities to maintain optimal energy states even in various approach situations.

- Plan: Before entering the approach phase, they establish energy management strategies considering airspace restrictions and expected traffic flow. They optimize approach profiles using FMS and prepare response plans for various ATC instruction scenarios. Particularly, they predict situations where High Energy states could occur and plan deceleration timing and external configuration change timing. Such systematic planning reduces workload during the approach phase and improves energy management predictability.

- Adapt: Continuously monitor aircraft energy states during actual approach and adjust strategies as needed. When control instructions change, quickly update FMS routes and select appropriate aircraft external configurations (Spoiler, Flap, Landing Gear, etc.) for the energy state. If High Energy states persist, make decisions such as requesting cooperation from control agencies or deciding to abort approach. By actively utilizing energy prediction information provided by FMS, they proactively respond to prevent unstable approach situations.

- Coordinate: Maintain clear communication between flight crew members about energy states and management strategies. Particularly in situations that deviate from standard operating procedures, clearly share intentions and plans and mutually verify them. Effectively communicate with control agencies to request additional distance or altitude if needed for energy management and clearly explain the reasons for necessary maneuvers.

5. Integrated Application of Safety-I and Safety-II

5.1. Integrated Application Framework

- Systematic failure analysis: Root cause identification through HEAR framework

- Resilient behavior definition: Derivation of specific behavioral elements for each case

- Adaptation strategy establishment: Application of PAM framework and LPAC model

- Practical guideline development: Presentation of specific guidelines applicable in the field

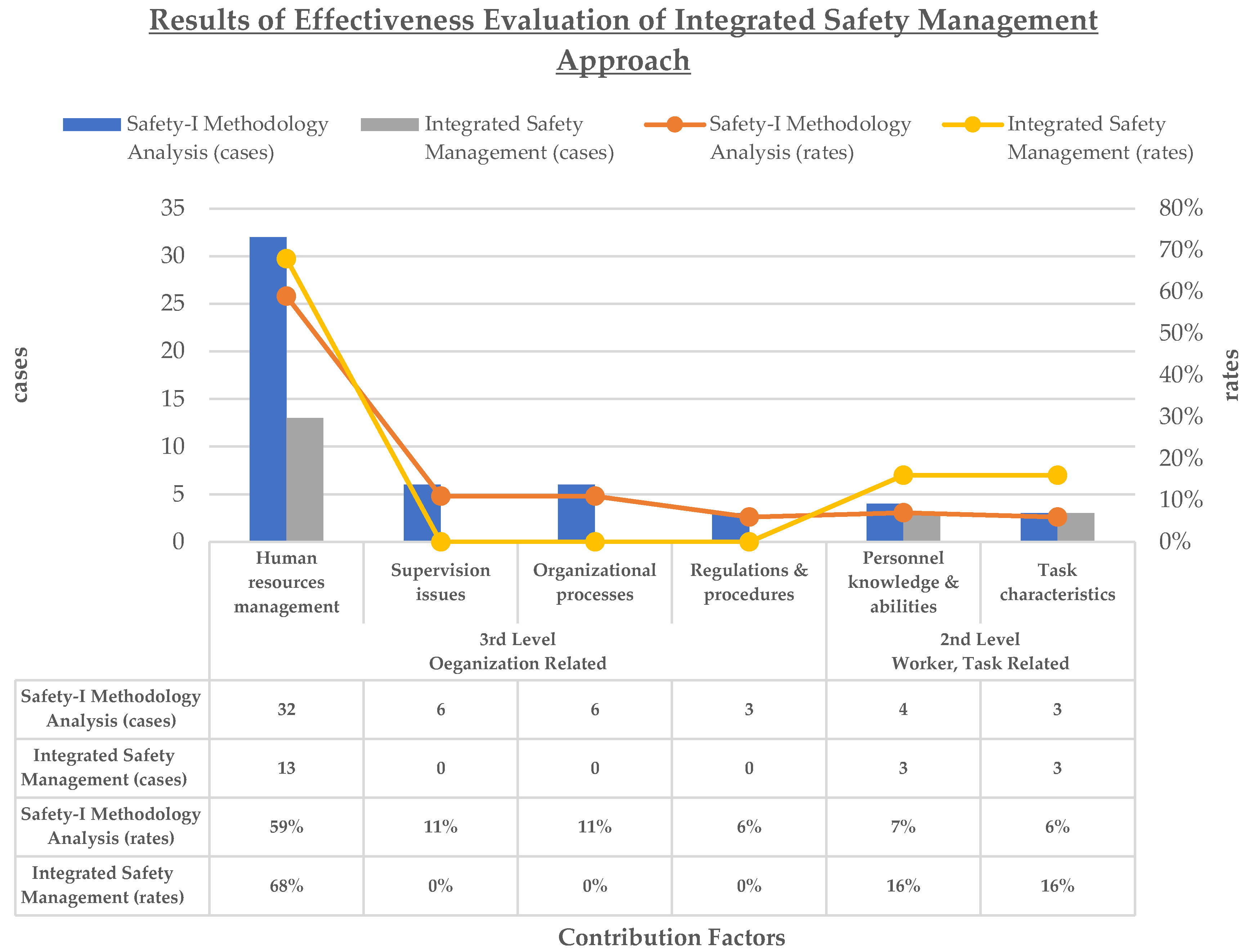

5.2. Effectiveness Evaluation

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Research Findings

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

References

- IATA. Interactive Safety Report. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/publications/safety-report/interactive-safety-report/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and safety-II: the past and future of safety management; CRC press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E.; Leonhardt, J.; Licu, T.; Shorrock, S.; EUROCONTROL. From Safety-I to Safety-II: a white paper. EUROCONTROL. 2013. Available online: https://skybrary.aero/sites/default/files/bookshelf/2437.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ham, D.H. Safety-II and Resilience Engineering in a Nutshell: An Introductory Guide to Their Concepts and Methods. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aven, T. A risk science perspective on the discussion concerning Safety I, Safety II and Safety III. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 217, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E.; Pariès, J.; Woods, D.; Wreathall, J. Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook; 2010.

- Kim, D.S.; Baek, D.H.; Yoon, W.C. Development and evaluation of a computer-aided system for analyzing human error in railway operations. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2010, 95, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- U.S DoD. U.S. Department of Defense Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (DoD HFACS) version 8.0. 2022. Available online: https://www.safety.af.mil/Portals/71/documents/Human%20Factors/DAF%20HFACS%208%20Guide%201%20April%202023.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- NASA. Human Factors Handbook V1.4 Procedural Guidance and Tools. 2023. Available online: https://standards.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/standards/NASA/Baseline/0/NASA-HDBK-870925.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Hollnagel, E. Cognitive reliability and error analysis method: CREAM. 1998.

- American Airlines Department of Flight Safety. Trailblazers into Safety-II: American Airlines’ Learning and Improvement Team, A White Paper Outlining AA’s Beginnings of a Safety-II Journey. 2020. Available online: https://skybrary.aero/sites/default/files/bookshelf/5964.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- American Airlines Department of Flight Safety. Charting a new approach: What goes well and why at American Airlines, A whitepaper outlining the second phase of AA’s Learning and Improvement Team(LIT). 2021. Available online: https://skybrary.aero/sites/default/files/bookshelf/AA%20LIT%20White%20Paper%20II%20-%20SEP%202021 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Flight Safety Foundation. Learning From All Operations Concept Note 1: The Need for Learning From All Operations. 2022. Available online: https://flightsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/LAO-Concept-Note-1-rev2.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Flight Safety Foundation. Learning From All Operations Concept Note 7: Pressures, Adaptations and Manifestations Framework. 2022. Available online: https://flightsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/LAO-Concept-Note-7_rev1.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Flight Safety Foundation. Learning From All Operations Concept Note 6: Mechanism of Operational Resilience. 2022. Available online: https://flightsafety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/LAO-Concept-Note-6_rev2.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- MOLIT. Cabin crew injury due to turbulence encountered during flight. 2022. Available online: https://araib.molit.go.kr/USR/airboard0201/m_34497/dtl.jsp (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Nanduri, A.; Sherry, L. Generating flight operations quality assurance (foqa) data from the x-plane simulation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Integrated Communications Navigation and Surveillance (ICNS); 2016; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, J. SKILLS, RULES, AND KNOWLEDGE - SIGNALS, SIGNS, AND SYMBOLS, AND OTHER DISTINCTIONS IN HUMAN-PERFORMANCE MODELS. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1983, 13, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, E.; Pritchett, A. SRK as a framework for the development of training for effective interaction with multi-level automation. Cognition Technology & Work 2016, 18, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterson, P.; Le Coze, J.C.; Andersen, H.B. Recurring themes in the legacy of Jens Rasmussen. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 59, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T.; Magis-Weinberg, L.; Jansen, B.R.J.; Van Atteveldt, N.; Janssen, T.W.P.; Lee, N.C.; Van Der Maas, H.L.J.; Raijmakers, M.E.J.; Sachisthal, M.S.M.; Meeter, M. Motivation-Achievement Cycles in Learning: a Literature Review and Research Agenda. Educational Psychology Review 2022, 34, 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

| Causes & Contributing Factors | Cases | Rates (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | Total | C1 | C2 | C3 | Total | ||

| 2nd Level: Personnel & Task Related |

Personnel Knowledge & Experience | 6.7 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 7.4 | ||||

| - Lack of knowledge | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| - Lack of assessment ability | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Task Characteristics | 0.0 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 5.6 | |||||

| - Insufficient time | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| - High risk tasks | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3rd Level: Organization Related | Regulations & Procedures | 6.7 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 5.6 | ||||

| - Absence/Inaccurate procedures | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Human Resources Management | 53.4 | 68.8 | 56.5 | 59.3 | |||||

| - Absence of training | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |||||

| - Lack of education | 1 | 6 | 7 | 14 | |||||

| - Inadequate content | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | |||||

| - Inadequate evaluation | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||||

| Management & Supervision | 20.0 | 6.3 | 8.7 | 11.1 | |||||

| - Resource provision issues | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| - Supervisory neglect | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| - Inadequate analysis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Organizational Culture | 13.3 | 12.5 | 8.7 | 11.0 | |||||

| - Safety culture issues | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | |||||

| Total | 15 | 16 | 23 | 54 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Category | FMS Operation | Turbulence Response | Energy Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resilient Behavior Definition (Summary) | FMS principle understanding-based quick/accurate response during instrument approach procedure changes | Weather information analysis and system utilization-based turbulence avoidance response | FMS-based energy state monitoring and appropriate management |

| Pressure Factors (Pressure) | STAR/IAP mismatch Late runway change Time constraints |

Forecasted turbulence Passenger safety requirements Schedule adherence pressure |

ATC instructions Airspace restrictions Traffic flow |

| Key Systems | FMS Database Instrument approach procedures |

Weather radar Weather information systems |

FMS-based energy management Air traffic flow management |

| Learn | FMS principle and function understanding Approach procedure change experience sharing |

Weather phenomenon understanding Weather data analysis capability enhancement |

Energy management principle knowledge FMS-based energy management |

| Plan | Runway/approach procedure change preparation Alternative procedure discussion |

Avoidance strategy pre-establishment Cabin safety measures planning |

Energy management strategy establishment FMS profile optimization |

| Adapt | Quick FMS reconfiguration ATC cooperation request |

Real-time weather assessment Vertical/horizontal avoidance |

FMS-based energy adjustment Aircraft configuration optimization |

| Coordinate | Flight crew intention sharing ATC communication |

Cabin crew safety measure coordination ATC information sharing |

Energy state continuous sharing Additional distance/altitude request if needed |

| Key Elements | Safety-I Application | Safety-II Application | Integration Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Method | HEAR Framework | LPAC Model, PAM Framework | Systematic failure analysis and resilience enhancement |

| Primary Focus | Root cause identification | Adaptation strategy development | Comprehensive safety management approach |

| Implementation Tools | Why-Because Tree | Resilient behavior definition | Practical application guidelines |

| Expected Effects | Failure prevention | Success expansion | Sustainable safety improvement |

| Causes | Contribution Factors | Existing (Safety-I Methodology Analysis) | Improved (Integrated Safety Management) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases | cases | ||||||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | Total | C1 | C2 | C3 | Total | ||

| 2nd Level Personnel, Task Related |

Personnel’s knowledge, experience, abilities | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Task characteristics | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 3rd Level Organization Related |

Characteristics of regulations and business procedures | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Management of an organization’s human resources | 8 | 11 | 13 | 32 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 13 | |

| Management and supervision issues | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Organizational processes, policies, and culture | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 15 | 16 | 23 | 54 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 19 | |

| Causes | Contribution Factors | Existing (Safety-I Methodology Analysis) | Improved (Integrated Safety Management) | ||||||

| rates (%) | rates (%) | ||||||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | Total | C1 | C2 | C3 | Total | ||

| 2nd Level Personnel, Task Related |

Personnel’s knowledge, experience, abilities | 6.7% | 6.3% | 8.7% | 7.4% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 15.8% |

| Task characteristics | 0.0% | 6.3% | 8.7% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 25.0% | 15.8% | |

| 3rd Level Organization Related |

Characteristics of regulations and business procedures | 6.7% | 0.0% | 8.7% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Management of an organization’s human resources | 53.3% | 68.8% | 56.5% | 59.3% | 80.0% | 83.3% | 50.0% | 68.4% | |

| Management and supervision issues | 20.0% | 6.3% | 8.7% | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Organizational processes, policies, and culture | 13.3% | 12.5% | 8.7% | 11.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).