Introduction

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is a national icon, World Heritage Area, and under sustained threat from climate change and terrestrial land-use. It is also a complex $56 billion asset generating 64,000 jobs and contributing $6.4 billion annually to Australia’s economy (2016 figures). With 1.2 million residents in the 32 local government areas of the reef region, the reef’s health directly impacts local economies and communities.

Current GBR management strategies often separate environmental concerns from economic and social issues, treating the GBR as a closed environmental system with emphasis on ecological restoration, through predominately government funding.

There is a fundamental paradox in how climate adaptation strategies are designed. We acknowledge climate is a dynamic, complex, and emergent system, yet we anchor strategies to models that, by necessity, simplify complexity into linear or probabilistic scenarios. This leads to two key issues: a fixation on predictive certainty; and overlooking systemic interactions and Tipping Points.

Adaptation must be systemic, not siloed; with policy, finance, infrastructure and cultural adaptation interconnected through a management system where economic resilience, ecological health, and social stability are equally recognised as essential outcomes.

In this essay, we propose that alignment of reef investments with collaborative regional resilience through a Great Barrier Reef Economic Zone (GBREZ) will address this paradox and improve the resilience of the regions sustained by and who care for the GBR. More inclusive than standard linear mechanistic thinking, this circular approach will leverage the GBR’s international status to attract continuing investment in regional resilience and sustainable growth and improve GBR management outcomes.

The GBREZ aims to integrate financial sustainability with ecological preservation by

recognising that government funding is not a ‘rescue package’ but an essential and on-going investment in the maintenance of the ecological infrastructure that underpins economic activity;

identifying the connection between a healthy regional economy and the ability of that region to contribute to and be part of ongoing ecological asset maintenance;

reducing the current predominant dependence of environmental work on fluctuating, politically sensitive government funding;

identifying and harmonising policy and funding overlaps and duplications;

diversifying regional economies through nature-based activities, particularly ones that draw on local understanding of and connection to country;

promoting and celebrating the alignment of regional economic activities with environmental imperatives.

The GBREZ seeks to create from the ground up a resilient economic infrastructure that supports the ongoing health of the reef through resilient, empowered communities.

This essay is further intended as a first step towards the development and popular acceptance of a comprehensive governance framework that redefines traditional conservation funding models - fostering a self-sustaining economy that builds resilience and prosperity for both the region and the reef.

Because paradigm shifts occur when people want them, not when they’re imposed.

The Here and the Now

The world is in trouble. Drought, bushfires, storms, ocean acidification, sea level rise and global warming impact everyday people’s lives every day. Climate change has altered marine, terrestrial, and freshwater ecosystems around the world, increased disease, and driven mass mortality of plants and animals at rates hundreds of times higher than the fossil record. How did we come to live in an Anthropocene extinction event?

Throughout recent European history (the past 200+ years) Nature has been regarded as a resource to be exploited for economic growth rather than as an integral part of the economic system. Times change, and the natural world is now increasingly recognised as a key foundation for our economic and social lives, providing the core infrastructure and inputs within which all economies, and life, function (Whitton & Waterford, 2023).

These economies though, they’re not real. They’re a human construct underpinned by another human construct - money. Trees, water, blue skies and people are real. This was made clear in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) where nothing physical changed except … the agreed value and availability of money (see Kinley (2018)).

The GFC impacts were still profound and far reaching, as capitalism is programmed to privilege profit and growth before consideration for the health of human communities and the living earth. The account books of nations and corporations are key to the 21st century global economy. They translate value into the language of modern times -numbers and money - in the shape of Gross Domestic Product GDP and profit figures. They rule the world (Gleeson-White, 2014).

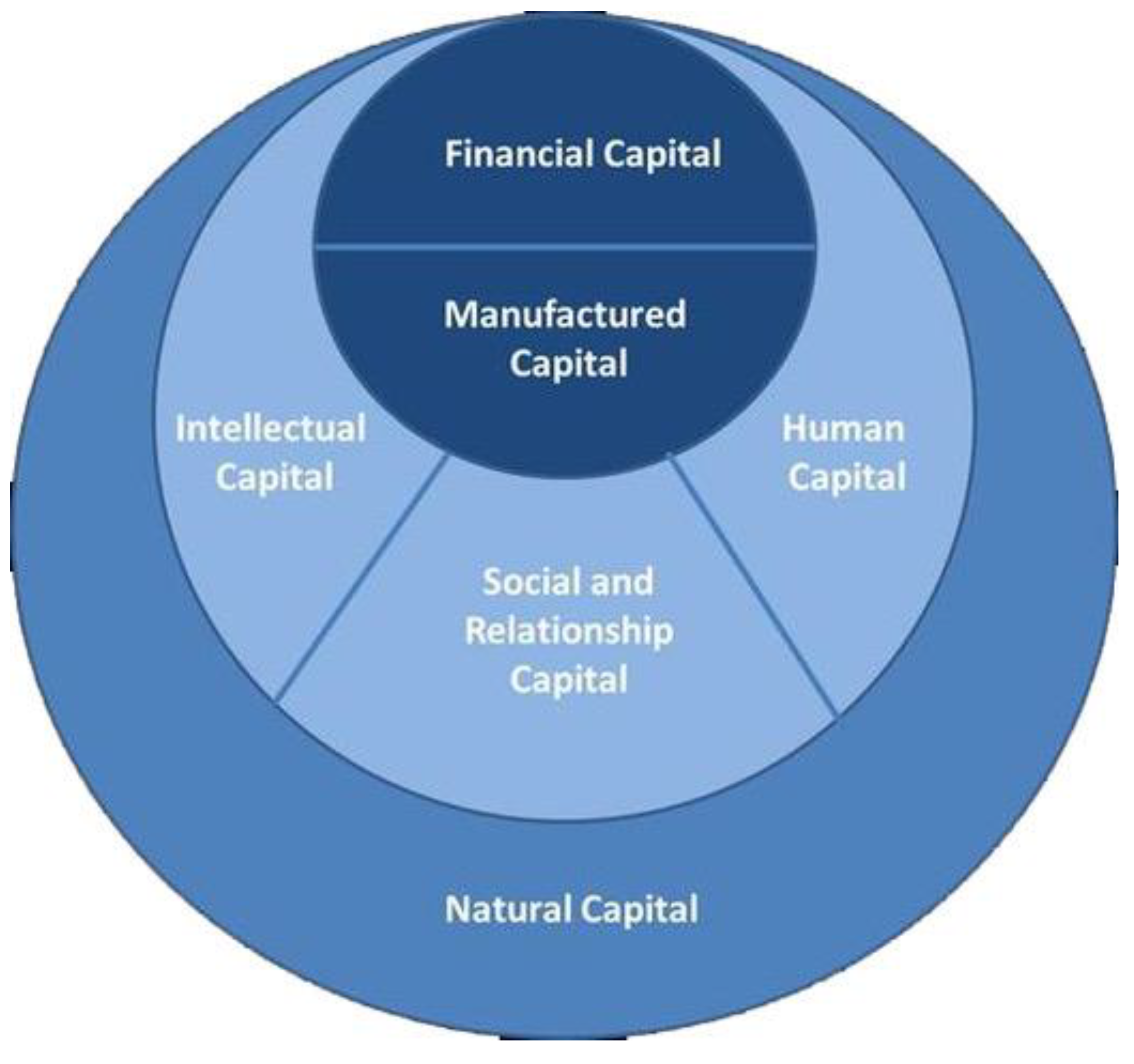

Money, however, is only one of six recognised ‘capitals’ that are affected by or transformed by the activities and outputs of people. The other capitals are Industrial, Intellectual, Human, Social & Relationship (sometimes called Cultural), and Natural Capital. Collectively, these six capitals more realistically describe and account for the sustainability of the world in which we live and operate than the single metric of GDP.

Figure 1.

The Six Capitals, from Sewchurran (2015).

Figure 1.

The Six Capitals, from Sewchurran (2015).

In 2012, two important initiatives occurred: the first, an international movement to transform corporate accounting for the 21st century known as the International Integrated Reporting Council; and second, driven by the World Bank, United Nations endorsement of Natural Capital accounting for nations and the global economy. Together, these developments facilitated emergence of new thinking in business, including:

a push for a new corporation legally bound to benefit nature and society while making a profit;

ecosystem accounting for nations; and

legal rights for nature which resonate with Indigenous earth-centred laws.

While this recognition of the intersection of nature and capital markets may seem sudden, it represents a maturing of humanity’s understanding of what is required to build truly sustainable economies. These movements are critical for the future of human life on this planet. If fully implemented, they have the potential to override the profit-driven modern corporation, the growth-driven nation state, and the legal status of the natural world as lifeless property (Gleeson-White, 2020).

The notion that Financial Capital can sit apart from Natural Capital makes no sense. Nor does the notion that ‘the economy knows best’, or that ‘the market’ should be left to decide how the world operates using algorithms restricted to a single capital metric. This thinking is an extension of the devolution of personal responsibility to someone / something else rather than accept that we, individually and collectively, are responsible for our actions and the world we live in through those actions.

In the words of Paul Hardisty (2023) “It’s not a place to live we need to find, it’s a way of living”. What is the financial sector’s role in finding this new way of living? Can the system often blamed for environmental destruction repair past damage and achieve sustainable management?

There is hope. Hannah Ritchie’s 2024 book “Not the End of the World” posits that today’s generation could be the first ever to leave the world in a better state than they found it. The intention of this essay is to stimulate wider discussion and understanding of this possibility and promote action on how society might achieve this miracle, starting with Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

The Need for Change

In 2023 PwC reported that more than half of the world’s GDP -$US58 trillion - was dependent on nature; up from $US44trn in 2020. But is this right? Doesn’t the natural world underpin all economic activity and society? Rather than debate percentages, let’s acknowledge that society is not even close to properly investing in the maintenance of Earth’s essential ecological infrastructure.

Rather, we mine it in the naive belief that resources will last forever, or someone else will fix it. The prevailing colonialist/pioneer paradigm of Australia’s European settlement disrupted a stable human/landscape system, often through lack of understanding. Such attitudes persist in the “can do” engineering approach many companies continue to default to, with accusations of timidity, risk-aversion, and opposition to development made against opponents rather than as opportunities to consider alternatives.

Such leaps to industrial scale solutions are a perpetuation of the mindset that has brought the world to this place of unprecedented climate change and nature loss. Ken Henry

1 describes this thinking of the past 250 years as “hurtling towards a cliff”. If we are to avoid going over that cliff, he suggests we need to do something different, fast. To persist with the system thinking that drives us towards a precipice at the same time as expecting a different outcome is a definition of lunacy. A different approach is needed from one that offsets bad actions in one place by good actions in another. A paradigm change is required.

Our Evolving World

The 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) acknowledged that climate change and biodiversity challenges are inextricably linked, and that COP parties need to protect and restore nature as an essential act in restricting global warming.

Two weeks later, at the UN Framework Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) in Canada, 188 attending countries agreed to global action on nature to address biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and protect indigenous rights through the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. While a significant outcome for global biodiversity, the framework lacked actual funding mechanisms.

The truly significant COP15 outcome was the evident support by business for a Nature Positive future, with recognition that financial entities, markets and instruments along with governments are central to delivering a global Nature Positive outcome. Suddenly, the phrase Nature Positive was everywhere.

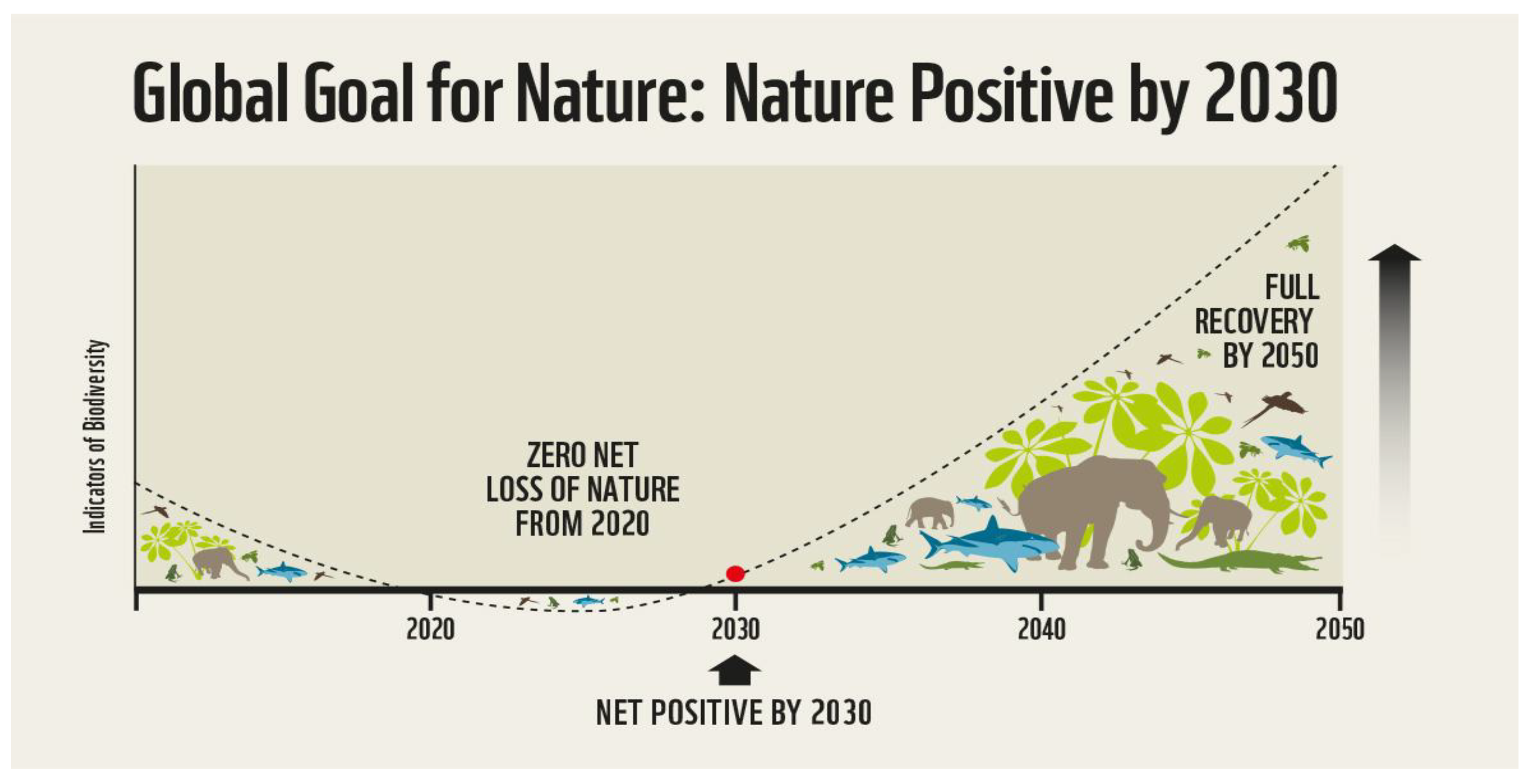

The idea is simple: rather than mine the natural world, a Nature Positive future envisions more nature than what we have now. The Nature Positive concept has been embraced by industry, world leaders and conservationists. Sudden popularity however can also be reason for caution, as many well-intended ideas have subsequently become cover for greenwashing, and a Nature Positive future should not provide a fig leaf for continuing failure (Maron, Evans, & Ermgassen, 2023).

Figure 2.

What does Nature Positive look like?

Figure 2.

What does Nature Positive look like?

Financial institutions, companies, and investors don’t have a structured or auditable way to invest in nature beyond philanthropy, but they want one. Of the 12,000 participants

registered for COP15, more than 1,500 were business representatives from 500 companies. Many appeared to have more ambition that global governments in their desire for mandatory disclosure, strong targets, and the removal of harmful subsidies. Large progressive multinational companies were seeking a level playing field through regulation, and keen to learn from innovations in the voluntary nature market.

People, Place and Money

The current biodiversity crisis is often depicted as a struggle to preserve untouched habitats. However, work by Ellis et al. (2021) combined global maps of human populations and land use over the past 12,000 years with current biodiversity data to show that nearly three quarters of terrestrial nature has long been shaped by diverse histories of human habitation and use by Indigenous and traditional peoples. In Australia this relationship between people and place extends back 65,000 years.

With rare exceptions, biodiversity losses are caused not by human conversion or degradation of untouched ecosystems, but by the appropriation, colonization, and intensification of use in lands inhabited and used by prior societies. Ellis et al. believe the current biodiversity crisis can seldom be explained by the loss of uninhabited wildlands, and instead flows from the appropriation, colonization, and intensifying use of the biodiverse cultural landscapes long shaped and sustained by traditional custodians of the land. As the apex species, humans now have responsibility for all species and habitat.

Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) play an important role in stewarding nature, and both groups rely on nature and are affected by changing approaches to its management. IPLCs are clearly important stakeholders, and their perspective and understanding should inform any landscape management discussion. It is only fair that they also benefit from their enduring connection to nature.

Many (most?) conservation efforts are constrained by inadequate funding. While nature-based carbon projects that address climate change can deliver additional development benefits including nature restoration and conservation, most of the ecosystem services that landscapes provide beyond sequestering carbon have no clear direct monetisation pathway or direct connection to local communities.

Creating a globally scalable nature-crediting framework could address these challenges and drive finance towards critical nature conservation and restoration activities, including methods for verifiably quantifying the benefits to nature and biodiversity achieved. Nature Credits would be generated for companies and investors on the demand side to buy (Vincent, 2023), and so a market would develop.

Business and finance institutions are also looking for implementation plans that link the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) to the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and acknowledge the interconnectedness of climate, nature, and community.

The Evolving Role of Business in Society

In 2017, the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) provided recommendations to help companies supply information to support informed capital allocation. Mandatory climate reporting by large Australian companies against these international sustainability standards commenced 1 July 2024. Failure to disclose, or inadequate disclosure, attracts a civil penalty. While there are challenges for businesses responding to the evolving understanding of the actual physical risk of their business from and on climate, many companies already seek market advantage through active promotion of their green credentials.

Building on this TCFD success, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is a global market-led, science-based and government-backed initiative that has developed disclosure recommendations and guidance for organisations looking to report and act on evolving nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks and opportunities. The recommendations and guidance enable business and finance to integrate nature into decision making and support a shift in global financial flows away from nature-negative outcomes and toward nature-positive outcomes. Over time, TNFD is likely to lead to Australian companies being also required to make biodiversity risk disclosures in their financial reports.

This imminent era of globally consistent climate and sustainability reporting represents both risk and opportunity for business. The risk of greenwashing needs to be balanced against the risk of green-hushing – a failure to disclose activity for fear of accusations of greenwashing. There will be significant scrutiny from regulators, investors and stakeholders of public statements, which will need to be backed with credible, reliable information, not just well-intentioned aspirations. An evolution in business thinking is required, with new metrics and language along with competitive advantage to be derived from companies showing stakeholders their commitment to balance environmental and social sustainability with profit.

While there is rapid evolution in this space, the most significant work required will be to ensure markets deliver just and equitable benefits for the stewards of biodiversity. To do this, the principles of integrity, transparency and strong governance must be affirmed and enforced. And unlike the carbon market, where a tonne of carbon is equivalent no matter where in the world it is sequestered, there is no current universal metric to equate an area of the Great Barrier Reef to one in the Gibson Desert. Both are equally important to maintain, but how to relate them through a financial instrument?

Some groups express concern about monetising nature. Caution around the ability of the very system that brought about the world’s present precarious position to now solve it is understandable. Care is required to ensure that IPLCs see real outcomes from the evolution of markets and IPLCs should not lose access to nature through market developments. Free Prior and Informed Consent of IPLCs must occur in all project developments for nature markets.

The financial system that enables the global economy to operate 24/7 across different time zones, languages, and national currencies to deliver verifiable real-time transactions is not inherently bad or evil - it’s astonishing! It has developed collectively by many societies over thousands of years and is quite possibly one of humanity’s few globally agreed outcomes. Not to use it because up to now it has more often delivered bad environmental outcomes through a restricted focus on financial profit negates the agency of people for change.

Meanwhile, in Australia

The COP15 preparedness for business to recognise and act on the combination of evolving community attitudes and good science was already evident in Australia.

Most Australians are aware of the uniqueness and value of Australia’s biodiversity and many Australians feel connected to nature and want to know it is being looked after. The Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD), the largest director membership organisation in the world

2, recognises that climate change is creating risks and opportunities for organisations, and that investors, regulators, employees and other stakeholders are challenging directors to address climate risk at an organisational level.

The twenty-first century has seen recognition of, and action on, the stewardship responsibilities of Australia’s farmers and other private landholders (Noble, Dennis, & Larkins, 2019, pp. 70-72) and a 2023 Biodiversity Council report found 97% of Australians want more action to protect nature (Borg et al., 2023). But the responsibility to do something about better management of the environment is still largely perceived as belonging to government. This is particularly so when it comes to the extensive rangelands that typify Australia’s landscape, and management of protected areas like the Great Barrier Reef.

Hundreds of billions of dollars were rapidly mobilised to manage the global pandemic, $368bn has been committed to purchasing new submarines, annual fossil fuel subsidies reportedly exceed $10bn, yet a 2023 $1.8bn environment-spend announcement was headline news (and a decision driven by the UNESCO threat to list the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area as “in danger”).

The Copernicus Climate Change Service announced 2024 the warmest on record, with an average global temperature of 1.6ºC above the pre-industrial average. Environmental collapse is a real and current threat to life as we know it as the impacts of climate change manifest around the world and feature in headline nightly news services (E. Ritchie, 2023). An increased environment spend would be a shrewd national investment for Australia, not a cost, would create thousands of jobs in regional Australia, sustain and grow many industries and enable new ones to emerge, and make us all safer, happier, and healthier.

But what is the likelihood of a government environment spend at the required scale - hundreds of times current expenditure? Particularly during a national cost-of-living crisis; escalating demands on health and other community services; the need for real-time disaster relief and repair from extreme weather events accelerated by climate change (Norman, 2023); global unrest and actual conflict; never mind Australia’s partisan political climate?

In early 2022 the Australian software billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes attempted the purchase of AGL Energy, the nation’s single biggest carbon dioxide emitter, with an expressed aim to bring forward closure of its coal-fired power assets. When this takeover was rejected by AGL’s board, Cannon-Brookes subsequently had four independent directors elected to the board by shareholders who will deliver the early closures and increase investment in renewable energy.

Cannon-Brookes achieved this through presenting the clean energy transition as the best and more profitable business decision for shareholders. The Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility described the outcome as “a victory for shareholders and a scathing indictment on those who spent years destroying shareholder value by delaying the inevitable in the face of an escalating energy transition”.

This achievement required shareholders to step outside the standard operating paradigm and adopt an unblinkered and wholistic understanding of the role of the company within a broader social and environmental context. At what point will such an understanding of the role of business become the norm? Increasingly investors are holding companies to account through shareholder action, and there is tremendous growth in capital earmarked to support sustainability themes and create positive impact (Banhalmi-Zakar, 2023).

During the debate prior to Australia’s 2023 constitutional referendum on the Voice an ex-Australian Prime Minister stated that indigenous disadvantage only occurred in remote communities, where kids didn’t go to school and there was no employment. Having lived and worked in some of Australia’s most remote communities I knew the ex-PM was wrong. Indigenous disadvantage exists across Australia, with significant differences in progress markers like life expectancy, health, wealth and suicide, irrespective of remote or inner-city urban. All pre-European Australians were remote from the western world, but people weren’t sitting around waiting for someone to give them a job. Everyone was busy maintaining their relationship with the continent that had developed over 65,000+ years, an achievement unequalled around the globe.

Australians are proud of our unique landscapes and wildlife, but until recently simply did not appreciate how much work went into keeping them in the condition found when colonisers first appeared on country. Through the work of people like Bill Gammage and Bruce Pascoe Australians are realising Australia is a human landscape, and Australians have a responsibility to maintain these landscapes. That’s a job, and an important one.

But what if that ex-PM’s view became policy? It did for a while, and essential resources and life in general became much harder in remote communities. What if it got too hard, and everyone moved to the city to ‘get a job’? Where would the grey nomads buy fuel and bread on their ‘big lap’? Where would the Flying Doctor land in emergencies? Who would keep an eye on those wide-open spaces? Does Australia really want a big empty centre with free rein for drug runners and reprobates? If not, who pays for the human presence that precludes it?

Social media, for all the terrible things we read about it, demonstrates the interaction of Social and Financial Capital as people derive real incomes from their social status. Social media influences individual action at all scales, from national elections to neighbourhood interactions. I talk to my teenage son about this as he ‘fixes’ my phone, and we discuss where the world is heading. He understands my concerns but is not burdened by them, and I find relief in his youthful perspective. We discuss how there is more and more ‘stuff’ in the world, but there’s not more of the world. Turning beach sand into glass is one thing, turning it into an iPhone is a complete energy-intensive other. But if that phone means we don’t clear fell forests to make phone books, perhaps with time we’ll find balance.

The transition to a nature-positive economy is complex but necessary. By taking a systematic approach - and getting started now - companies can assess dependencies and impacts, set strategic priorities, and demonstrate progress to stakeholders (Howard, Middleton, Felton, & Plant, 2023), and what better place to start than on the Great Barrier Reef.

Shifting Paradigms and the Great Barrier Reef

The challenges affecting the Great Barrier Reef have become increasingly evident through symptoms of declining ecological health. The causes have been thoroughly examined, revealing a wide range of factors that have directly or indirectly impacted the Reef’s health. The concept of health in this instance refers broadly to a dynamic, biodiverse system that can maintain itself, adapting to fluctuations in conditions, recovering from adverse circumstances, and thriving, as is expected of all ecological systems.

The Reef is also closely connected to the increasingly important phenomenon of eco-anxiety. Its degradation may subtly remind people, particularly younger generations, of broader environmental issues. Studies have shown that younger people tend to link ecological degradation with hopelessness about the state of the world, leading them to experience high levels of anxiety and other associated psychological disorders that impact on their capacity to function.

Contemporary GBR management is focused on ecological restoration and conservation through predominately government funding, and often to the exclusion of the interconnected regional social and economic dimensions. Could a model recognising the interconnectedness of economic and ecological systems, and promoting resilient and complex thinking as a proactive strategy, deliver a better outcome?

The economic value of the Reef has been argued just as strongly as its value as a biodiversity asset. Figures produced nearly a decade ago and repeated as flagship points include an asset value of $56billion, its direct contribution to the nation’s economy of $6.5 billion annually, and its supporting of 64,000 jobs. If the Reef is such an economic asset as is persistently and justifiably argued, then it begs the question: why couldn’t the economy of the Reef’s economic zone maintain its own asset?

The Reef benefits everyone. The billions of tourist dollars it contributes to the national economy provide a sound argument that the whole of society should contribute to its maintenance, whether through philanthropy, corporate donations, or taxation. However, this arrangement may not be sustainable in complex circumstances with emergent challenges. What happens if climate impacts intensify or, as we are already seeing, become more widespread - with fires in the south, cyclones in the north, and floods in the middle? Could the political appetite for continuous support be maintained, or is there a risk of “Peak Reef”, reaching a saturation point in terms of attention before achieving the necessary or complimentary support required?

In the same way that the Reef is not just an environmental issue, the economy of the region isn’t just an economic issue; it’s a complex cultural, social, and environmental issue that we need to start seeing from a complex perspective.

Instead of having management based on government funding, supplemented by philanthropy, corporate contributions, and market forces, could we establish a system anchored in a strong local economy supported by government, corporate, and other contributions? This would not be a simplistic rearrangement of the deck of cards – it would be a fundamental pivot that makes a less visible dividend in the short term but transformative difference in the long run. The strategic impacts differ when long-term Reef health is coupled to a thriving local economy that is the mainspring of an economic, social, and environmentally resilient region directing its own future in collaboration with governments and other sectors.

It is important to highlight that this concept does not seek to disrupt current work and investment; rather, it intends to build on it. The efforts of so many people, and the real results being delivered are remarkable on the world stage and should be celebrated and continued. They also need to serve as a foundation for the future – a reimagining of what we are doing within an expanded framework.

The concept is not for the establishment of a new business, institutional entity, or for a self-governing region. There are many areas around the world which, while they don’t have formal boundaries, operate as economic zones; for example, the Barossa Valley wine region of South Australia, and Italy’s Tuscany.

Regardless of how people assign value to the Reef, we know that this dynamic influences how they respond to actions taken (or not taken) to protect the Reef. When we rely on a system vulnerable to government decisions, corporate philanthropy, and market forces, we inevitably face too many unknowns and issues that could become overwhelming. To counteract this, we can think about resilience in a different way. Resilience in this context isn’t just a risk management strategy but a growth strategy. The entire system - social, economic, and ecological - connected in a dynamic and collaborative relationship can prepare for and mitigate risks and build back better.

We propose recognition of The Great Barrier Reef Economic Zone (GBREZ) - a model where investments from government, corporations, philanthropy, private donors, and others are recognisably connected and consequently become more sustainable and attractive. This attraction comes from the understanding that investing in the Reef is safe and beneficial and the increased resilience becomes a competitive advantage, making the region attractive for further investment.

The Reef Economic Zone concept framework emphasises the importance of strategic collaboration across diverse sectors, building on successful collaborative models and networks developed in previous reef, landscape, and disaster resilience programs. The concept was borne from firsthand experience with large-scale reef and landscape restoration projects and reflects a deep understanding of the practical challenges and complexities involved in ecological restoration. It also draws on lived experience and place-based involvement in regional community resilience and well-being.

Resilience is a key component of the Reef Economic Zone, informed by extensive experience in disaster resilience and collaboration, highlighting the need for adaptive strategies that can withstand environmental and socio-economic challenges. Resilience, in this context, is not merely a mechanism for risk mitigation. It is a foundation for regional growth. By fostering interdependent relationships between ecological sustainability, economic development, and social stability, the GBREZ will ensure conservation efforts are financially viable and structurally supported within a dynamic economic framework.

Foundations of the Reef Economic Zone

1.2 million people live within the Great Barrier Reef region, geographically the size of Italy. It is rich in biological and cultural diversity, and the Gross Regional Product (GRP) across its 32 local government areas (with 19 already participating in the Reef Guardians program) is $90 billion, or $75k per person. This is significantly higher than the average Australian per capita GRP of $67k (IMF figures) and ranks higher than half the world’s countries.

The GBREZ concept is built upon the principle that, since these communities directly benefit from the ecological assets in which they live, the economic activities within the region should directly contribute to reef preservation and sustainability. Also, the association with and understanding of place by Reef communities and industries assists adaptive management decisions while also improving identification of and timely response to emergent events and opportunities.

Several key advantages underpin this model:

Local Economy as the Foundation: Establishing a self-sufficient economic base that minimizes reliance on fluctuating government allocations and maximises regional ownership and participation.

Resilience as a Growth Strategy: Flips resilience from a defensive “withstanding shocks” concept to a proactive strategic advantage – being prepared for the unexpected - a smart investment that enhances economic value, social stability, and environmental sustainability.

Recognises and Values Local knowledge: Encourages local involvement by recognising single solutions are rarely universally applicable and can be fine-tuned through local experience and understanding.

Greater Stability: A locally driven model ensures a more consistent and predictable flow of financial resources dedicated to reef management while also generating new economic opportunities.

Integrated and Informed Funding: Encouraging coordination among government agencies, corporations, and philanthropic entities to align investments with long-term sustainability objectives.

Sustainability and Growth: Ensuring that economic expansion and industrial activities are Nature Positive and actively contribute to environmental conservation and ecological health along with regional prosperity.

Reduced Dependence on External Funding: Diversifying revenue sources to enhance financial stability and protect against policy and market uncertainties.

Holistic and Adaptive Approach: Implementing a flexible and forward-thinking model that can evolve to address emerging environmental, economic, and social challenges.

Strategic Implementation and Governance

To achieve its objectives, the Reef Economic Zone will require a structured governance framework that integrates economic and environmental policies into a cohesive, collaborative and transparent strategy. The following key components will drive the success of the GBREZ:

Regional Collaboration: Establishing partnerships between local governments, industries, research institutions, and community organizations to foster a shared economic and environmental vision.

Investment and Financial Innovation: Developing investment mechanisms, such as sustainability bonds, reef-focused enterprise zones, and environmental financial instruments, that generate long-term funding for reef conservation initiatives.

Public and Private Sector Alignment: Encouraging sustainable business practices through incentives, regulatory support, and economic policies that promote investment in ecological and social resilience.

Integrated Policy Development: Creating regulatory frameworks that support economic diversification while prioritizing environmental integrity, ensuring that industries operating within the GBREZ contribute positively to reef health.

Adaptive Management Strategies: Enabling place-based decision-making systems that can implement data-driven decision-making and ongoing monitoring systems to adjust policies and investment strategies in response to environmental and economic changes.

Fortunately, many of the necessary components already in place and at work:

Seven of Queensland’s 12 Regional NRM Organisations have operated within the Reef’s catchments for over 20-years, each with a NRM Plan to protect and improve the region’s natural assets, developed in partnership with the people who live in these communities and who rely on the region’s natural assets for their lifestyle and livelihoods

Five Healthy Water Partnerships are in operation from the Daintree to Bundaberg. These are collectives from business, industry, research, education, community, and all levels of government who gather and analyse data to provide their community with an independent picture of waterway and reef health

The Local Government Association of Queensland is a not-for-profit association enabling local governments to share learnings, innovate, and improve services and strengthen relationships with their communities

Regional peak advocacy and economic development organisations striving for prosperous regional futures include Townsville Enterprise Ltd., Advance Cairns, the Greater Whitsunday Alliance, Advance Rockhampton, and the Bundaberg Ag-Food & Fibre Alliance.

Conclusion

Establishment of a Reef Economic Zone is an opportunity to adopt a transformative approach to managing one of the world’s most recognised natural assets. By integrating economic stability and social capacity with environmental stewardship, the GBREZ concept will provide a sustainable, long-term solution that enhances the financial independence of conservation efforts while fostering regional economic resilience - a new paradigm.

Through strategic collaboration, innovative investment mechanisms, and a commitment to sustainability, the GBREZ ensures that the Great Barrier Reef continues to thrive as both an ecological wonder and an economic powerhouse. By reframing conservation as an economic imperative, the GBREZ sets a precedent for future environmental and economic sustainability initiatives, offering a replicable model for ecologically sensitive regions around the world.

Three core challenges stand out:

Efforts Must Be Coordinated, Not Isolated – The most successful conservation strategies link ecological goals to economic realities, ensuring sustainability is built into the system rather than dependent on external funding.

Resilience Requires Structural Change, Not Just More Resources – The challenge is not about securing more funding but about embedding sustainability into the fabric of economic and policy decision-making.

Local and Global Strategies Must Align – The reef’s health is tied to international climate trends. Future efforts must integrate local conservation with broader economic and environmental frameworks.

The Great Barrier Reef has always been a symbol of natural wonder and resilience. The key to its future lies in moving beyond crisis management and embracing a structured, integrated model that aligns environmental sustainability with economic viability.

The Reef Economic Zone concept is a blueprint for how that could be achieved.

| 1 |

Australian economist and Secretary of the Department of the Treasury 2001-11. |

| 2 |

|

References

- Banhalmi-Zakar, Z., Herd, E., Goodwin, M., Pilawskas, P., Srivastava, P., Maniktala, M., Ghainder, S., Khoo, N., Polidori, M. (2023). Responsible Investment Benchmark Report 2023 Australia. Retrieved from Melbourne.

- Borg, K., Smith, L., Hatty, M., Dean, A., Louis, W., Bekessy, S., Williams, K., . . . Wintle, B. (2023). Biodiversity Concerns Report: 97% of Australians want more action to protect nature. Retrieved from https://biodiversitycouncil.org.au/media/uploads/2023_6/202305_biodiversity_concerns_survey_report.pdf.

- Ellis, E. C., Gauthier, N., Klein Goldewijk, K., Bliege Bird, R., Boivin, N., Díaz, S., . . . Watson, J. E. M. (2021). People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(17), e2023483118. [CrossRef]

- Gammage, B. (2011). The biggest estate on earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

- Gleeson-White, J. (2014). Six capitals: the revolution capitalism has to have -- or can acccountants save the planet? Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Gleeson-White, J. (2020). Six Capitals Updated Edition: Capitalism, climate change and the accounting revolution that can save the planet: Allen & Unwin.

- Hardisty, P. E. (2023). The Forcing. London: Orenda Books.

- Henry, K. (2022).

- Howard, P., Middleton, O., Felton, M., & Plant, L. (2023). Get started on your TNFD journey: A 6-step guide to get ahead of new nature reporting requirements. Retrieved from www.naturemetrics.com.

- Integrated Reporting. (2021). INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK. Retrieved from https://www.integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/InternationalIntegratedReportingFramework.pdf.

- Kinley, D. (Producer). (2018, Fri 21 Sep 2018 at 5:48am). The global financial crisis changed everything, and nothing. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-09-21/gfc-australian-economy-wall-street-finance-poverty/10282472.

- Maron, M., Evans, M., & Ermgassen, S. (Producer). (2023). ‘Nature positive’ isn’t just planting a few trees – it’s actually stopping the damage we do. The Conversation.

- Noble, K., Dennis, T., & Larkins, S. (2019). Agriculture and Resilience in Australia’s North: A Lived Experience. Singapore: Springer.

- Norman, B. (2023). Urban Planning for Climate Change. London: Routledge.

- Pascoe, B. (2014). Rethinking Indigenous Australia’s agricultural past. In C. Pryor (Ed.), Bush Telegraph: ABC Radio National.

- Ritchie, E. (2023, 3.5.2023). Australia being unable to afford greater environmental protection is a government myth that refuses to die. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/may/03/federal-budget-2023-australia-being-unable-afford-greater-environmental-protection-myth-refuses-die.

- Ritchie, H. (2024). Not the End of the World: How we can be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet.: Little Brown Spark.

- Sewchurran, K., Schorger, D. (2015). Towards an interpretive measurement framework to assess the levels of integrated and integrative thinking within organisations. Risk governance & control: financial markets & institutions, 5(3). [CrossRef]

- Vincent, S. (2023). Crediting nature. Biodiversity Insight, 2023, 12 - 13. Retrieved from www.environmental-finance.com.

- Whitton, Z., & Waterford, L. (2023). THE POLLINATION OVERVIEW ON NATURE AND CAPITAL MARKETS. NATURE FINANCE FOCUS: Tracking global trends in nature investment. Retrieved from.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).