Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Pathogenic Mechanism of Long Covid

3. Risk Factors for Long COVID

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine on the Prevention of Long COVID

5.2. Impact of Antivirals on the Prevention of Long COVID

5.3. Impact of Other Treatments on the Prevention of Long COVID

6. Discussion

6.1. COVID-19 Vaccines Reduce the Risk of Long COVID

6.2. Equivocal Evidence for Protective Effect of Antivirals and Other Drugs

6.3. Nutrients and Lifestyle Factors on Long COVID

6.4. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Timeline. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html. Accessed December 7, 2024.

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV, National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine Committee on Examining the Working Definition for Long C. Long Covid Defined. N Engl J Med 2024.

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. Accessed December 7, 2024.

- Committee on Examining the Working Definition for Long COVID (Washington District of Columbia). A long Covid definition : a chronic, systemic disease state with profound consequences. Washington: National Academies Press, 2024.

- Global Burden of Disease Long CC, Wulf Hanson S, Abbafati C, et al. Estimated Global Proportions of Individuals With Persistent Fatigue, Cognitive, and Respiratory Symptom Clusters Following Symptomatic COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. JAMA 2022; 328(16): 1604-15.

- Carlile O, Briggs A, Henderson AD, et al. Impact of long COVID on health-related quality-of-life: an OpenSAFELY population cohort study using patient-reported outcome measures (OpenPROMPT). Lancet Reg Health Eur 2024; 40: 100908. [CrossRef]

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023; 21(3): 133-46.

- Li J, Zhou Y, Ma J, et al. The long-term health outcomes, pathophysiological mechanisms and multidisciplinary management of long COVID. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023; 8(1): 416. [CrossRef]

- Proal AD, VanElzakker MB. Long COVID or Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An Overview of Biological Factors That May Contribute to Persistent Symptoms. Front Microbiol 2021; 12: 698169. [CrossRef]

- Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023; 10: 1187163. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. N Engl J Med 2024; 391(6): 515-25. [CrossRef]

- Proal AD, VanElzakker MB, Aleman S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nat Immunol 2023; 24(10): 1616-27.

- Stein SR, Ramelli SC, Grazioli A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy. Nature 2022; 612(7941): 758-63.

- Swank Z, Senussi Y, Manickas-Hill Z, et al. Persistent Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Spike Is Associated With Post-acute Coronavirus Disease 2019 Sequelae. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023; 76(3): e487-e90. [CrossRef]

- Glynne P, Tahmasebi N, Gant V, Gupta R. Long COVID following mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: characteristic T cell alterations and response to antihistamines. J Investig Med 2022; 70(1): 61-7. [CrossRef]

- Klein J, Wood J, Jaycox JR, et al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 2023; 623(7985): 139-48. [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol 2022; 23(2): 210-6. [CrossRef]

- Su Y, Yuan D, Chen DG, et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022; 185(5): 881-95 e20. [CrossRef]

- Peluso MJ, Deveau TM, Munter SE, et al. Chronic viral coinfections differentially affect the likelihood of developing long COVID. J Clin Invest 2023; 133(3). [CrossRef]

- Pretorius E, Vlok M, Venter C, et al. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021; 20(1): 172. [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci 2021; 24(2): 168-75. [CrossRef]

- Sarubbo F, El Haji K, Vidal-Balle A, Bargay Lleonart J. Neurological consequences of COVID-19 and brain related pathogenic mechanisms: A new challenge for neuroscience. Brain Behav Immun Health 2022; 19: 100399. [CrossRef]

- Turner S, Khan MA, Putrino D, Woodcock A, Kell DB, Pretorius E. Long COVID: pathophysiological factors and abnormalities of coagulation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2023; 34(6): 321-44. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Mak JWY, Su Q, et al. Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut 2022; 71(3): 544-52. [CrossRef]

- Zollner A, Koch R, Jukic A, et al. Postacute COVID-19 is Characterized by Gut Viral Antigen Persistence in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2022; 163(2): 495-506 e8. [CrossRef]

- Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020; 159(3): 944-55 e8. [CrossRef]

- Mendes de Almeida V, Engel DF, Ricci MF, et al. Gut microbiota from patients with COVID-19 cause alterations in mice that resemble post-COVID symptoms. Gut Microbes 2023; 15(2): 2249146. [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Pooya AA, Akbari A, Emami A, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Long COVID Syndrome: A Retrospective Study. Iran J Med Sci 2021; 46(6): 428-36. [CrossRef]

- Bai F, Tomasoni D, Falcinella C, et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28(4): 611 e9- e16. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Martin-Guerrero JD, Pellicer-Valero OJ, et al. Female Sex Is a Risk Factor Associated with Long-Term Post-COVID Related-Symptoms but Not with COVID-19 Symptoms: The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM Multicenter Study. J Clin Med 2022; 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS One 2020; 15(11): e0240784. [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi MC, Tieri P, Ortona E, Ruggieri A. ACE2 expression and sex disparity in COVID-19. Cell Death Discov 2020; 6: 37. [CrossRef]

- Forster C, Colombo MG, Wetzel AJ, Martus P, Joos S. Persisting Symptoms After COVID-19. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2022; 119(10): 167-74.

- Guzman-Esquivel J, Mendoza-Hernandez MA, Guzman-Solorzano HP, et al. Clinical Characteristics in the Acute Phase of COVID-19 That Predict Long COVID: Tachycardia, Myalgias, Severity, and Use of Antibiotics as Main Risk Factors, While Education and Blood Group B Are Protective. Healthcare (Basel) 2023; 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med 2021; 27(4): 626-31.

- Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27(2): 258-63. [CrossRef]

- Vimercati L, De Maria L, Quarato M, et al. Association between Long COVID and Overweight/Obesity. J Clin Med 2021; 10(18). [CrossRef]

- Quan SF, Weaver MD, Czeisler ME, et al. Association of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am J Med 2024; 137(6): 529-37 e3. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Quan L, Chavarro JE, et al. Associations of Depression, Anxiety, Worry, Perceived Stress, and Loneliness Prior to Infection With Risk of Post-COVID-19 Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 2022; 79(11): 1081-91.

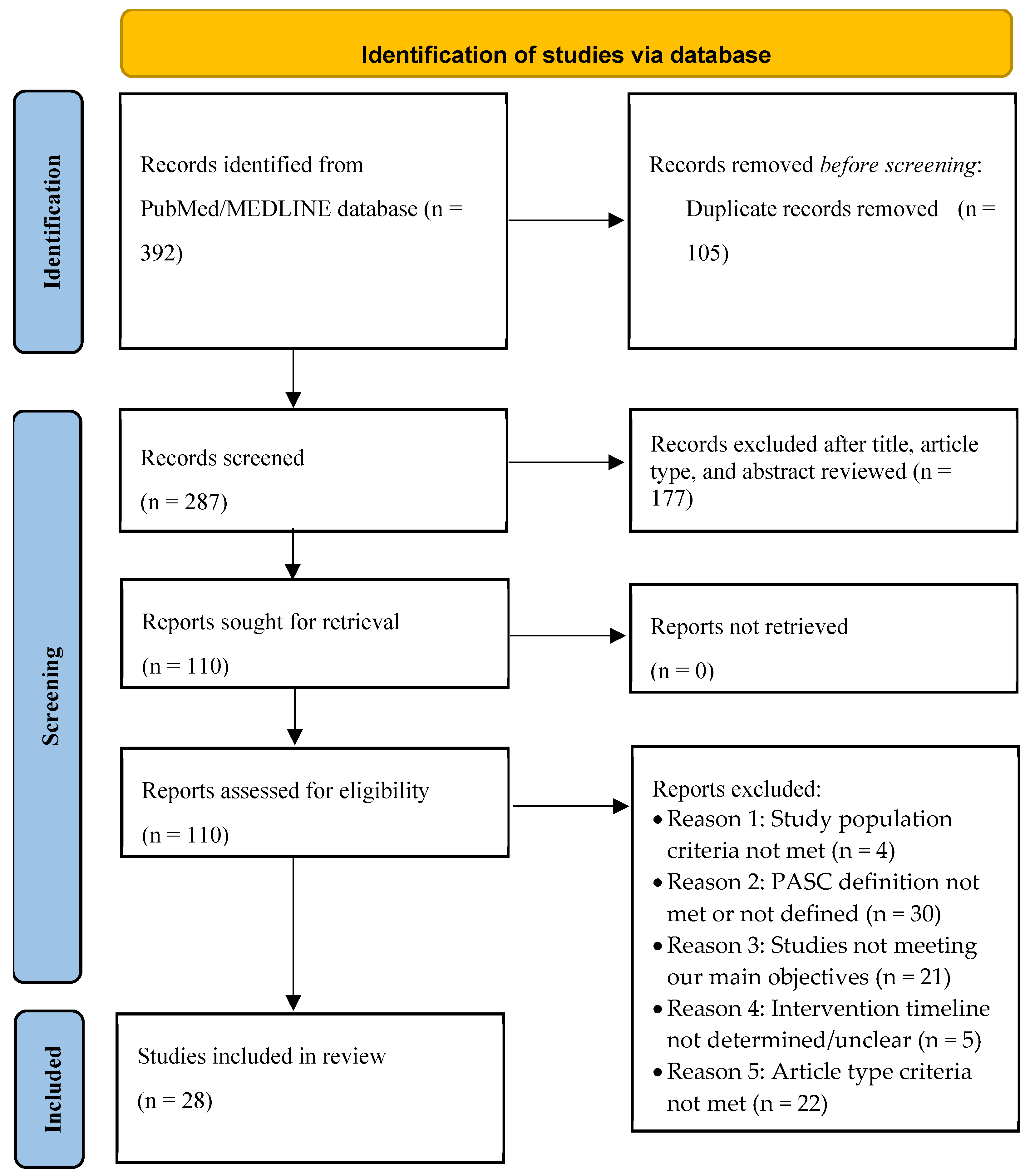

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71.

- Abu Hamdh B, Nazzal Z. A prospective cohort study assessing the relationship between long-COVID symptom incidence in COVID-19 patients and COVID-19 vaccination. Sci Rep 2023; 13(1): 4896. [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. Bmj 2022; 377: e069676. [CrossRef]

- Babicki M, Kapusta J, Pieniawska-Śmiech K, et al. Do COVID-19 Vaccinations Affect the Most Common Post-COVID Symptoms? Initial Data from the STOP-COVID Register-12-Month Follow-Up. Viruses 2023; 15(6). [CrossRef]

- Bertuccio P, Degli Antoni M, Minisci D, et al. The impact of early therapies for COVID-19 on death, hospitalization and persisting symptoms: a retrospective study. Infection 2023; 51(6): 1633-44. [CrossRef]

- Bramante CT, Buse JB, Liebovitz D, et al. Outpatient treatment of Covid-19 with metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine and the development of Long Covid over 10-month follow-up. medRxiv 2022.

- Brunvoll SH, Nygaard AB, Fagerland MW, et al. Post-acute symptoms 3-15 months after COVID-19 among unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals with a breakthrough infection. Int J Infect Dis 2023; 126: 10-3. [CrossRef]

- Català M, Mercadé-Besora N, Kolde R, et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID symptoms: staggered cohort study of data from the UK, Spain, and Estonia. Lancet Respir Med 2024; 12(3): 225-36. [CrossRef]

- Catalán IP, Martí CR, Sota DP, et al. Corticosteroids for COVID-19 symptoms and quality of life at 1 year from admission. J Med Virol 2022; 94(1): 205-10. [CrossRef]

- Congdon S, Narrowe Z, Yone N, et al. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and risk of long COVID symptoms: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 2023; 13(1): 19688. [CrossRef]

- Davelaar J, Jessurun N, Schaap G, Bode C, Vonkeman H. The effect of corticosteroids, antibiotics, and anticoagulants on the development of post-COVID-19 syndrome in COVID-19 hospitalized patients 6 months after discharge: a retrospective follow up study. Clin Exp Med 2023; 23(8): 4881-8.

- Durstenfeld MS, Peluso MJ, Lin F, et al. Association of nirmatrelvir for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection with subsequent Long COVID symptoms in an observational cohort study. J Med Virol 2024; 96(1): e29333. [CrossRef]

- Fatima S, Ismail M, Ejaz T, et al. Association between long COVID and vaccination: A 12-month follow-up study in a low- to middle-income country. PLoS One 2023; 18(11): e0294780. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Franco-Moreno A, Ruiz-Ruigomez M, et al. Is Antiviral Treatment with Remdesivir at the Acute Phase of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Effective for Decreasing the Risk of Long-Lasting Post-COVID Symptoms? Viruses 2024; 16(6). [CrossRef]

- Gebo KA, Heath SL, Fukuta Y, et al. Early antibody treatment, inflammation, and risk of post-COVID conditions. mBio 2023; 14(5): e0061823. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Zhang J, Tang HT, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of long COVID 6-12 months after infection with the Omicron variant among nonhospitalized patients in Hong Kong. J Med Virol 2023; 95(6): e28862. [CrossRef]

- MacCallum-Bridges C, Hirschtick JL, Patel A, Orellana RC, Elliott MR, Fleischer NL. The impact of COVID-19 vaccination prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection on prevalence of long COVID among a population-based probability sample of Michiganders, 2020-2022. Ann Epidemiol 2024; 92: 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Nehme M, Vetter P, Chappuis F, Kaiser L, Guessous I, CoviCare Study T. Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease Condition 12 Weeks After Omicron Infection Compared With Negative Controls and Association With Vaccination Status. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023; 76(9): 1567-75. [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen OPO, Horstia S, Laakkonen S, et al. Effect of remdesivir post hospitalization for COVID-19 infection from the randomized SOLIDARITY Finland trial. Nat Commun 2022; 13(1): 6152. [CrossRef]

- Trinh NT, Jödicke AM, Català M, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID: data from Norway. Lancet Respir Med 2024; 12(5): e33-e4. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhao D, Xiao W, et al. Paxlovid reduces the risk of Long COVID in patients six months after hospital discharge. J Med Virol 2023; 95(8): e29014. [CrossRef]

- Woldegiorgis M, Cadby G, Ngeh S, et al. Long COVID in a highly vaccinated but largely unexposed Australian population following the 2022 SARS-CoV-2 Omicron wave: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust 2024; 220(6): 323-30. [CrossRef]

- Xie Z, Stallings-Smith S, Patel S, Case S, Hong YR. COVID-19 booster vaccine uptake and reduced risks for long-COVID: A cross-sectional study of a U.S. adult population. Vaccine 2024; 42(16): 3529-35. [CrossRef]

- Yoon H, Li Y, Goldfeld KS, et al. COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Therapy: Long-term Implications. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024; 11(1): ofad686. [CrossRef]

- Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Canas LDS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection following booster vaccination: Illness and symptom profile in a prospective, observational community-based case-control study. J Infect 2023; 87(6): 506-15. [CrossRef]

- Richard SA, Pollett SD, Fries AC, et al. Persistent COVID-19 Symptoms at 6 Months After Onset and the Role of Vaccination Before or After SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6(1): e2251360. [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2022; 28(7): 1461-7. [CrossRef]

- Azzolini E, Levi R, Sarti R, et al. Association Between BNT162b2 Vaccination and Long COVID After Infections Not Requiring Hospitalization in Health Care Workers. Jama 2022; 328(7): 676-8. [CrossRef]

- Brannock MD, Chew RF, Preiss AJ, et al. Long COVID risk and pre-COVID vaccination in an EHR-based cohort study from the RECOVER program. Nat Commun 2023; 14(1): 2914. [CrossRef]

- Di Fusco M, Sun X, Moran MM, et al. Impact of COVID-19 and effects of booster vaccination with BNT162b2 on six-month long COVID symptoms, quality of life, work productivity and activity impairment during Omicron. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2023; 7(1): 77.

- Lundberg-Morris L, Leach S, Xu Y, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against post-covid-19 condition among 589 722 individuals in Sweden: population based cohort study. BMJ 2023; 383: e076990. [CrossRef]

- Malden DE, Liu IA, Qian L, et al. Post-COVID conditions following COVID-19 vaccination: a retrospective matched cohort study of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun 2024; 15(1): 4101. [CrossRef]

- Sigler R, Covarrubias K, Chen B, et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2023; 25(6): e14167.

- Tannous J, Pan AP, Potter T, et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies against postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2: analysis of a COVID-19 observational registry for a diverse US metropolitan population. BMJ Open 2023; 13(4): e067611. [CrossRef]

- Taquet M, Dercon Q, Harrison PJ. Six-month sequelae of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection: A retrospective cohort study of 10,024 breakthrough infections. Brain Behav Immun 2022; 103: 154-62. [CrossRef]

- Boglione L, Meli G, Poletti F, et al. Risk factors and incidence of long-COVID syndrome in hospitalized patients: does remdesivir have a protective effect? QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 2022; 114(12): 865-71.

- Fung KW, Baye F, Baik SH, McDonald CJ. Nirmatrelvir and Molnupiravir and Post-COVID-19 Condition in Older Patients. JAMA Intern Med 2023; 183(12): 1404-6. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou GN, Berry K, Rajeevan N, et al. Effectiveness of Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir Against the Development of Post-COVID-19 Conditions Among U.S. Veterans : A Target Trial Emulation. Ann Intern Med 2023; 176(11): 1486-97.

- Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Association of Treatment With Nirmatrelvir and the Risk of Post-COVID-19 Condition. JAMA Intern Med 2023; 183(6): 554-64. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Molnupiravir and risk of post-acute sequelae of covid-19: cohort study. BMJ 2023; 381: e074572. [CrossRef]

- Tomasa-Irriguible TM, Monfà R, Miranda-Jiménez C, et al. Preventive Intake of a Multiple Micronutrient Supplement during Mild, Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection to Reduce the Post-Acute COVID-19 Condition: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024; 16(11). [CrossRef]

- Krishna B, Wills M, Sithole N. Long COVID: what is known and what gaps need to be addressed. Br Med Bull 2023; 147(1): 6-19. [CrossRef]

- Lin DY, Gu Y, Xu Y, et al. Association of Primary and Booster Vaccination and Prior Infection With SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Severe COVID-19 Outcomes. JAMA 2022; 328(14): 1415-26. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. First Oral Antiviral for Treatment of COVID-19 in Adults. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-oral-antiviral-treatment-covid-19-adults. Accessed December 7, 2024.

- Wang Y, Su B, Alcalde-Herraiz M, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors and the risk of post-COVID-19 multisystem sequelae, hospitalization, and death. Nat Commun 2024; 15(1): 6363. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento T, do Valle Costa L, Ruiz AD, et al. Vaccination status and long COVID symptoms in patients discharged from hospital. Sci Rep 2023; 13(1): 2481. [CrossRef]

| Study author | Study design / Country (data) | Study period/Participants (SARS-CoV-2 variants) | LC cases | Patient N (F %) | Age (years), mean ± SD or median (IQR) |

Vaccinated (%) vaccine type vaccination time |

Vaccine impact on LC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayoubkhani et al. [42] | Prospective cohort / UK | Community based; Visit during Feb-Sep 2021; COVID-19 at least 12 wks before the final visit / (A, Δ) |

LC 3-10 mo after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=28,356 (F 55.6%) | 45.9 ± 13.6 | Vaccinated (100%): BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or ChAdOx1 after COVID-19 | Protective,1st vaccine 12.8% reduction in the odds (P < 0.001); 2nd vaccine aditional 8.8% reduction (P = 0.003) |

| Antonelli et al. [64] | Prospective case-control study / UK | Community based; June-Nov 2021 (Δ) and Dec 2021-Apr 2022 (O) / cases (third dose recipient), controls (second dose recipient) |

LC Sx ≥ 12 wks | All COVID-19, Delta:n=1,910 in each group (F 57%); Omicron: n=7,894 in each group (F 60.7%) | Delta: cases 64 ± 12.8, controls 63.7 ± 12.9; Omicron: cases 45.5 ± 16.3, controls 44.3 ± 17.7 | Vaccinated (100%): 3 doses of monovalent in cases, 2 doses in controls) before COVID-19 | No differences between cases & controls in both Δ & O eras, but a trend towards protection in vaccinated; when LC, Sx ≥ 4 wks, cases with aOR 0.56 (95% CI: 044-0.70) during Δ era. |

| Richard et al. [65] | Prospective cohort / USA | Feb 2020-Dec 2021 (wild-type, A, Δ), data from MHS EPICC study | LC Sx ≥ 3mo | COVID-19, n=1832 (F 39%) | 40.5 ± 13.7 (age range 18-44) | Fully vaccinated (22.9%) [2 doses of BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273, or one dose of Ad26.COV2.S] before COVID-19 | Trend towards Protective, RR 0.73 (95%CI: 0.47-1.14)** (When LC Sx ≥ 28d, RR 0.72 (0.54-0.96) |

|

Nehme et al. [57] |

Prospective longitudinal cohort / Switzerland | Outpatients, COVID-19 during Dec 2021-Feb 2022 (O) | LC 3 mo after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=1807 (F 62.3%); COVID-19 negative, n=882 (F 63.9%) | COVID-19 positive, 41.6 ± 13.5 ; COVID-19 negative, 43.7 ± 14.9 | Fully vaccinated (75.5%) [at least 2 doses of mRNA-1273 (61.2%) or BNT162b2 (36.1%)] before COVID-19 | Protective, adjusted prevalence 9.7% vs. 18.1% (P < 0.001) |

| Brunvoll et al. [46] | Prospective cohort (Norweigian COVID-19 cohort) / Norway | COVID-19 during Nov 2020- Oct 2021 (wild-type, A, Δ) | LC 3 mo-15 mo after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=1420 (F 71%) | Vaccinated, 48.3 ± 11.4 ; unvaccinated, 45.7 ± 12.3 | Fully vaccinated (25%) [at least 2 doses of mRNA vaccines at least 2 wks before COVID-19] | No differences in all components except for memory problem, fully vaccinated vs. unvaccinated, 11.9 % vs. 17.3% (P = 0.02) |

| Abu Hamdh et al. [41] | Prospective cohort / Palestine | COVID-19 during Sep 2021- Jan 2022, with FU phone interviews on d 10, 30, 60, 90 / (mainly Δ) | LC at 90 d | COVID-19, n=669 (F 57%) | 35.9 ± 11.5 | Vaccinated (41%) [BNT162b2 (17.8%), Sputnik Light (12.7%), mRNA-1273 (3.7%), Sputnik V (2.4%), ChAdOx1 (2.4%)] before COVID-19 | Protective, ≥ 1 dose vaccinated vs. unvaccinated, aOR 0.15 (95% CI: 0.09-0.24) |

|

Fatima et al. [52] |

Prospective cohort / Pakistan | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 during Feb 2021-June 2021 / (A) | LC at 12 mo | COVID-19 patients admitted to Aga Khan University hospital, n=481 (F 38.3%) | 56.9 ± 14.3 | #Fully vaccinated (19%): 2 does of vaccines; partially vaccinated (19.2%): one dose before COVID-19 | Protective, fully vaccinated aOR 0.38 (95% CI: 0.20-0.70), partially vaccinated aOR 0.44 (95% CI: 0.24-0.80) |

| Nascimento et al. [85] | Prospective cohort / Brazil | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 during May 2021 and Feb 2022 (A, Δ, O) | LC at 90d | COVID-19 patients, n=412 (35.4%) | 60 (IQR 48-72) | Fully vaccinated (44.9%) [1 dose Janssen or 2 doses of #other vaccines before COVID-19 | Protective, aOR for fully vaccinated 0.55 (P= 0.007) |

|

Català et al. [47] |

Staggered retrospective cohort / UK (CPRD); Spain (SIDIAP); Estonia (CORIVA) | Primary care data; registered by Jan or Feb 2021, with FU until Jan 2022 (UK), June 2022 (Spain), Dec 2022 (Estonia) / (A, Δ, O) | LC between 90 d & 365 d after COVID-19 | Over 10 million vaccinated vs. over 10 million unvaccinated (n/a). | n/a | Vaccinated with one dose (BNT162b2, ChAdOx1, mRNA-1273, or Ad26.COV2.S ) +GOLD (49.7%); *AURUM (49.4); SIDIAP (51.5%); CORIVA (19.4%) before COVID-19 | Protective: +GOLD, sHR 0.54 (95% CI: 0.44–0.67); *AURUM, 0.48 (0.34–0.68); SIDIAP, 0.71 (0.55–0.91); CORIVA, 0.59 (0.40–0.87) |

|

Trinh et al. [59] |

Staggered retrospective cohort/ Norway (Norwegian Linked Health Registries) | Primary care data; Vaccination roll out from Jan to Aug 2021, FU up to 1 yr / (A, Δ, O) |

LC between 90d & 365 d after COVID-19 | Over 2.3 million vaccinated vs. over 1.5 million unvaccinated (n/a) |

n/a | Vaccinated at least one dose (60.7%) [BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or ChAdOx1] at least 14 d before COVID-19 | Protective, sHR 0.64 (95% CI: 0.55-0.74) |

|

Luo et al. [55] |

Retrospective cohort/ Hong Kong | Outpatient setting; COVID-19 during Dec 2021-May 2022 / (mainly O) |

LC at 6-12 mo after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=6,242 (F 66.9%) | 47 (IQR 36-60) | Boosted (57.5%; 3 or more BNT162b2 or CoronaVac) vs. less than 3 doses, before COVID-19 | Not protective, aOR 1.105 (95% CI: 0.985-1.239) |

| MacCallum et al.[56] | Population-based retrospective cohort/ USA | Outpatient setting; COVID-19 during March 2020-May 2022 / (wild-type, A, Δ, O) |

LC at 90 d after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=4,695 (F 54.0%) | age 18-29 (25.7%); age 30-49 (37.6%); age 50-64 (24.2%); 65+ (13.5%) | Fully vaccinated (27.9%) [2 doses of BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1, or Sinovac; or 1 dose of Ad26.COV2.S] before COVID-19 | Protective, aPR 0.42 (95% CI: 0.34-0.53) |

|

Babicki et al. [43] |

Retrospective cohort/ Poland (STOP-COVID registry) | Unspecified study period, FU visits at 3 mo and 12 mo after COVID-19/ (n/a) | LC at 1 yr after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=801 (F 65.4%) | 53.5 ± 12.8 | Fully vaccinated (83%) [2 doses of BNT162b2, mRNA-1273 or ChAdOx1 or 1 dose of Ad26.COV2.S], 73.6% vaccinated after COVID-19, 9.4% before COVID-19 | No differences, except that headache (17.4% vs. 29.4%, P=0.001), arthralgia (5.4% vs. 10.3%, P=0.032), dysregulation of HTN (11.6% vs. 18.4%, P=0.030) were more common in unvaccinated. |

| Woldegiorgis et al.[61] | Cross-sectional survey/ Australia | COVID-19 during July-Aug 2022, FU in 90 d / (O) | LC at 90 d after COVID-19 | COVID-19, n=11,697 (F 52.0%) | age 18-29 (20.9%); age 30-39 (21.0%); age 40-49 (18.7%); 50-59 (18.0%); 60-69 (11.6%); 70+ ( 9.7%) |

#Vaccinated, 0-2 (6%); three doses (76.3%); four doses (17.7%) before COVID-19 |

Protective, compared to vaccines 4 or more, 3 doses aRR 1.3 (95% CI: 1.1-1.5); 0-2 doses aRR 1.4 (1.2-1.8) |

|

Xie et al. [62] |

Cross-sectional survey/ USA | Outpatient setting; 2022 National Health Interview Survey / (O) |

LC 3 mo or longer post-infection | COVID-19, n=8,757(weighted 87,509,670) (F 53.3%) | age 18-29 (23.8%); age 30-39 (21.3%); age 40-49 (18.2%); age 50-64 (23.2%); 65+ (13.5%) | #Vaccinated, one dose (17.3%); initial series (33.3%); booster (27.2%) before COVID-19 | Protective, a booster vs. unvaccinated, aOR 0.75 (95% CI: 0.61-0.93) |

| Study author | Study design/ Country | Study period/Participants/ (SARS-CoV-2 variants) | LC cases | Patient N (F %) | Age, mean±SD or median (IQR) | Antivirals (treated %) | Antiviral impact on LC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nevalainen et al. [58] | Randomized trial / Finland | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 during July 2020 - Jan 2021/ (wild-type, A) | LC at 1 yr after COVID-19 | Treated 114 (F 35.1%); untreated 94 (F 36.2%). | Treated, 57.2 ± 13.5; untreated, 59.7 ± 13.2 | Remdesivir (200mg on the 1st day, then 100mg daily for a maximum 10 days.) |

No differences between remdesivir-treated & untreated with wide CI |

| Boglione et al. [75] | Prospective cohort / Italy | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 during March 2020-Jan 2021(wild-type, A) | LC symptoms ≥ 12 wks | Total 449 (F 22%); Remdesvir-treated 163; untreated 165 |

65 (IQR 56-75.5) | Remdesivir | Protective, OR 0.64 (95% CI: 0.41-0.78) |

|

Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al. [53] |

Retrospective, Case-control study / Madrid, Spain | Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 during Sep 2020-March 2021 / (wild-type, A) | LC at 3 mo or later following COVID-19 | Treated, 216 (F 43.5%); untreated, 216 (F 43.5%) | Treated, 55.4 ± 12.6; Untreated, 55.6 ± 12.7 | Remdesivir (200mg on the 1st day, then 100mg daily for a maximum 10 days.) |

Protective, OR 0.401 (95 CI: 0.256-0.628) |

| Durstenfeld et al. [51] | Prospective cohort / USA | Vaccinated, outpatients with their first SARS-CoV-2 positive between March and Aug 2022 / (O) | LC at 90 d or later following COVID-19 | Treated, 353 (F 53.3%); untreated, 1258 (F 64.9%) | Treated, 62.1 ± 12.7; Untreated, 55.1 ± 13.6 | Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir |

No association, aOR 1.15 (95% CI: 0.80-1.64) |

| Wang et al. [60] | Prospective cohort / Shanghai, China | Admitted with COVID-19, then discharged between April and June 2022 / (O) | LC at 6 mo since discharged | COVID-19, 634 (F 54.4%) | 74.1 ± 11.4 | Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir | Protective, OR 0.349 (95 CI: 0.205-0.595) |

| Congdon et al. [49] | Retrospective cohort / New York, USA | Phone interviews between May 2022 & Nov 2022; COVID-19 four mo before the phone interview / (Δ, O) | LC at 4 mo after COVID-19 | Treated, 250 (F 66.4%); untreated, 250 (F 73.6%). Hospitalized (1%). | 50.6 | Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir | No reduction of overall risk of LC (Incidence 44% vs. 50%, P=0.21; aOR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.57-1.2). |

|

Bertuccio et al. [44] |

Retrospective cohort / Italy | Outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19 during April 2021- March 2022 / (A, 3.5%; Δ, 2.2%; O 94.3%) | LC at 3 mo after COVID-19 | COVID-19, 649 (F 48.4%) |

67 (IQR 54-76) | 77 with antivirals (Molnupiravir, 41.6%; Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, 13.0%; remdesivir, 45.5%); 141 with mAbs (Bamlanivimab/ Etesevimab, 44.7%; Casirivimab, 16.3%; Sotrovimab, 39.0%) |

Antiviral Protective, aOR 0.43 (95% CI: 0.21-0.87) for any symptoms; mAbs Protective, aOR 0.48 (0.25-0.92) for neuro-behavioral symptoms; |

| Study author | Study design/ Country (Data) | Study period/Participants/ (SARS-CoV-2 variants) |

LC cases | Patient N (F %) | Age (years), mean ± SD or median (IQR) |

Treatment (treated %) | Treatment impact on LC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gebo et al. [54] | Randomized clinical trial/ USA | Outpatients with COVID-19 between June 2020 & Oct 2021 / (wild-type, A, Δ) | LC at 90 d after CCP | 882 (F 57.4%) | 43 ± n/a | CCP | No association, aOR 0.75 (95% CI: 0.46-1.23) |

|

Yoon et al. [63] |

A secondary analysis of randomized clinical trial/ USA (CONTAIN-RCT) | Hospitalized with COVID-19 between April 2020 & March 2021 / (wild-type, A) | LC at 18 mo post-randomization | 281 (F 44.5%) | 59 (IQR 50-67) | CCP | No association, aOR 0.95 (95% CI: 0.54-1.67) |

|

Bramante et al. [45] |

Randomized clinical trial / USA | Enrolled from Dec 2020 to Jan 2022 / (wild-type, A, Δ, O) | LC at 10 mo after randomization | 1,125 (F 56%) | 45 (IQR 37-54) | #Metformin, ivermectin, fluvoxamine | Only metformin was protective, HR 0.58 (95% CI: 0.38-0.88); Ivermectin, HR 0.99 (0.59-1.64); fluvoxamine, HR 1.36 (0.79-2.39) |

| Davelaar et al. [50] | Retrospective cohort/ The Netherlands | Hospitalized with COVID-19 between March 2020 & Sep 2021 / (wild-type, A, Δ) | LC at 6 mo after discharged | 123 (F 38.2%) | 62.1 ± 9.5 | Corticosteroids | Protective, aOR 0.32 (95% CI: 0.11-0.90) |

| Catalán et al. [48] | Retrospective cohort / Spain | Telephone survey between March 2021 & April 2021 for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 one yr earlier / (wild-type) | LC at 1 yr after discharged | 76 (F 38%) | Treated, 68.5 (IQR 60.2-75.5); untreated, 61.5 (IQR 52.7-72.5) | Corticosteroids | Protective: headache, 6.3% vs. 25% (P=0.032); dysphagia, 11.4% vs. 0% (P=0.049); depression (22.7% vs. 3.1 %, P=0.016), chest pain (11.4% vs. 0%, P= 0.049); bodily pain (SF-36*: 100 vs. 75, P=0.017), mental health (SF-36*: 86 vs. 76, P=0.027) |

| Tomasa-Irriguible et al. [80] | Randomized clinical trial / Catalonia, Spain |

Outpatients with COVID-19 between Sep 2021 & Feb 2023 / (Δ, O) | LC at 6 mo | 246 (F 68.3%) | 46.8 ± 16.3 | Multiple micronutrient supplement |

No reduction of incidence of LC (intervention 27.7% vs. placebo 25%; P=0.785) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).