1. Introduction

The global prevalence of anxiety disorders, based on data from 87 studies conducted in 44 countries, has been estimated at 7.3% [

1,

2,

3]. Furthermore, they are associated with significant disability [

3,

4], an increased risk of developing chronic diseases [

5], and high rates of comorbidity with other neuropsychiatric disorders, especially those related to mood and substance abuse [

6]. These disorders have a significant economic impact on society, primarily affecting the working-age population (18–64 years) and those with other psychiatric conditions [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Conventional treatment for anxiety includes benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; however, these drugs can cause adverse effects, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation [

11]. Since anxiety disorders are often chronic and require long-term treatment, it is essential that the medications used meet high standards of safety and adherence. In this context, herbal medicine emerges as a natural alternative with fewer side effects that can be used as a complementary or palliative treatment for anxiety disorders and other mental health conditions [

12]. Essential oils (EOs) have a long history in pharmaceutical sciences as natural products with diverse biological applications in the medicinal, cosmetic, agrochemical, and nutritional fields [

13]. Their use in aromatherapy and phytotherapy is widely recognized, especially for their effects on reducing stress and anxiety [

14] and in treating central nervous system disorders [

15]. Despite their popularity, the available scientific evidence presents methodological limitations in clinical studies on EOs [

16,

17,

18]. Therefore, further studies that provide greater rigor and validity to using EO are needed.

Remarkably, there is scientific evidence supporting the anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of certain EOs, with lavender EO (LEO) being one of the most studied for its relaxing properties and its traditional use in the treatment of anxiety, stress, and depression [

19]. Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP), and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) [

20] have approved the therapeutic use of lavender for these disorders. Several studies have analyzed its analgesic [

21], anti-inflammatory [

22], anxiolytic [

23], antidepressant [

24], and sleep-enhancing effects [

23]. Several authors report beneficial effects of LEO in humans, for example, pregnant women who used LEO during the second and third trimester of pregnancy have reported a significant improvement in anxiety and sleep quality [

25]. Moreover, an improvement in social anxiety was reported in first-year university students after LEO inhalation [

26], and its beneficial effect was even seen in people diagnosed with anxiety disorders when ingesting LEO [

27]. However, despite numerous publications, there are very few controlled preclinical studies with a systematic scientific methodology that demonstrate clinical efficacy and provide credibility to the effect of LEO [

28]. It is important to highlight that most of the data in the literature refer to human studies and aromatherapy.

Lavandula burnatii (

L. burnatii, clone Super), a hybrid resulting from the cross between

Lavandula angustifolia (L. angustifolia) and

Lavandula latifolia, is cultivated in the province of Córdoba, Argentina. This variety has a high concentration of linalool and linalyl acetate, compounds with described anxiolytic activity [

29].

L. burnatii is characterized by its robust growth, low to moderate water requirements, and excellent adaptability to the region's soils. Additionally, has an advantage since it has a 20 times higher productive yield of oil per plant than

L. angustifolia, and it has the same active components (linalool and linalyl acetate) and the other components of lavender essential oil, such as limonene, perillyl alcohol, coumarin, and camphor, present in other species with relative variation in their concentrations [

30] in a similar proportion. Based on the described characteristics, this study aims to evaluate the effect of

L. burnatii essential oil on anxiety behavior in male rats, given the fact there is no data about this variety cultivated in our region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Essential Oil

LEO: extracted from flower tops of Lavandula burnatii was provided by Dr. Cristian Moya (AROMAHERBA, Calmayo, Córdoba, Argentina). The aerial parts of L. burnatii were collected during the flowering stage from Córdoba, dried, and subjected to hydrodistillation. The oil was stored in sealed vials at 4°C.

Chemical characterization of LEO: GC-FID (Gas chromatography with flame ionization detector) was used to qualitatively characterize the LEO used in the present study. Quantitative analyses of EOs were performed using a PerkinElmer Clarus 500 equipped with an FID and a DB-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter and 0.25 μm film thickness). A 1 μL aliquot of LEO (1/100 v/v in n-heptane) was manually injected. The oven temperature was set as follows: 60 ◦C for 5 min, ramped to 240 ◦C at 5 ◦C/min and held for 10 min. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injector and detector temperatures were 250◦C and 280◦C, respectively. The abundance of each volatile EO compound was expressed as a relative percentage obtained by peak area normalization.

2.2. Animals

Adult male Wistar rats (250-300 g) were obtained from the Department of Pharmacology Otto Orsingher vivarium (Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina) and randomly housed in groups of 3 or 4 one week before the beginning of the experimental protocol. Throughout the experiment, animals were maintained in controlled environmental conditions (20–24°C, 12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 07 a.m.) and had free access to food and water. Behavioral experiments were conducted between 09:00 and 14:00 h.

All procedures were conducted following the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee CICUAL, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina (EX-2023-00769898-UNC-ME#FCQ).

2.3. Experimental Protocol

LEO of L. burnatii was developed and supplied by Dr. Cristian Moya. The plantation is located at 850 meters above sea level, and the geographic coordinates are -32.031034 and -64.459524.

LEO was used at two different concentrations (30 and 80 mg/Kg) in a mixture of medium-chain triglycerides (Myritol 318 Pura Química, Córdoba, Argentina). The EO was stored at 4°C, and Myritol was stored at room temperature, both away from light until use.

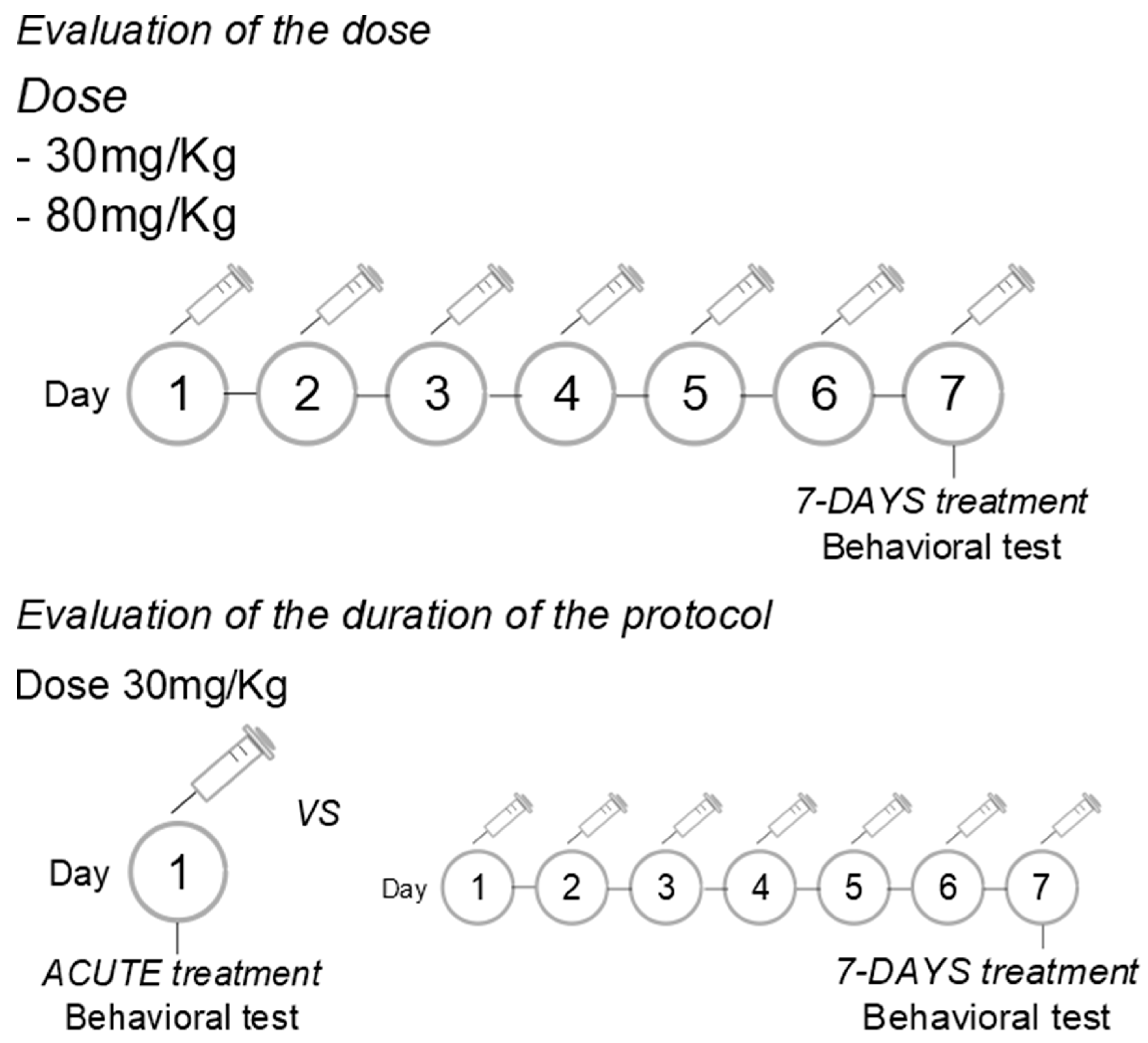

Evaluation of the dose: The LEO was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at doses of 30 or 80 mg/Kg, in a volume of 300 microliters, once daily for 7 consecutive days.

Evaluation of the duration of treatment: The LEO was administered in a dose of 30 mg/Kg (i.p.), in a volume of 300 microliters, acutely or once daily for 7 consecutive days. Since the dose evaluation was conducted first, we chose the dose with anxiolytic effects to assess the effective protocol of administration.

Control rats were treated with an equal volume of the vehicle (a mixture of medium-chain triglycerides). Experiments were conducted 1 h after the single or last drug/vehicle administration.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocols.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocols.

2.4. Behavioral Test

Elevated plus-maze test: The maze has two opposite arms (50 × 10 cm), crossed with two enclosed arms of the same dimension and having 40 cm high walls. The arms are connected with a central square (10 × 10 cm) giving the apparatus the shape of a plus sign. The maze was kept in a dimly lit room and elevated 50 cm above the floor. The rats were placed individually in the center of the maze, facing an open arm. Thereafter, the number of entries and time spent on the open and enclosed arms was recorded during the next 5 min. An arm entry was defined when all four paws of the rat were in the arm [

31].

Dark-light test: The apparatus comprises a transparent section, called the “illuminated area” (27 × 27 × 30 cm), and a smaller, fully enclosed section, called the “dark area” (18 × 27 × 30 cm) separated by a partition with a small opening (12 × 5 cm). The light side is illuminated by a bulb. The test begins with the animal placed in the dark area, and the latency to enter the illuminated area is recorded, considering only whole-body entries. The test was measured for 5 minutes.

Open-field test: The apparatus (61 x 61 x 50 cm) was made of plywood and consisted of squares, the entire apparatus was painted grey, which divided the floor into 16 squares. The animals were placed in the center of the apparatus and the ambulation (distance traveled) was measured, for 5 minutes, using Smart 3.0 software [

32].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using One-way ANOVA and Tukey's post-test. Data is reported as means ± SEM. A p-value of p< 0.05 was considered significant. The analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism® 8.02 software and the images were made by using Inkscape®.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we show clearly the anxiolytic effect of

L. burnatii EO in rats, moreover, we presented evidence of an effective dose and two protocols of administration. Our findings were obtained using two validated tests for anxiety where the plus maze evaluates the fear of open spaces, the dark light test evaluates the aversion to illuminated spaces [

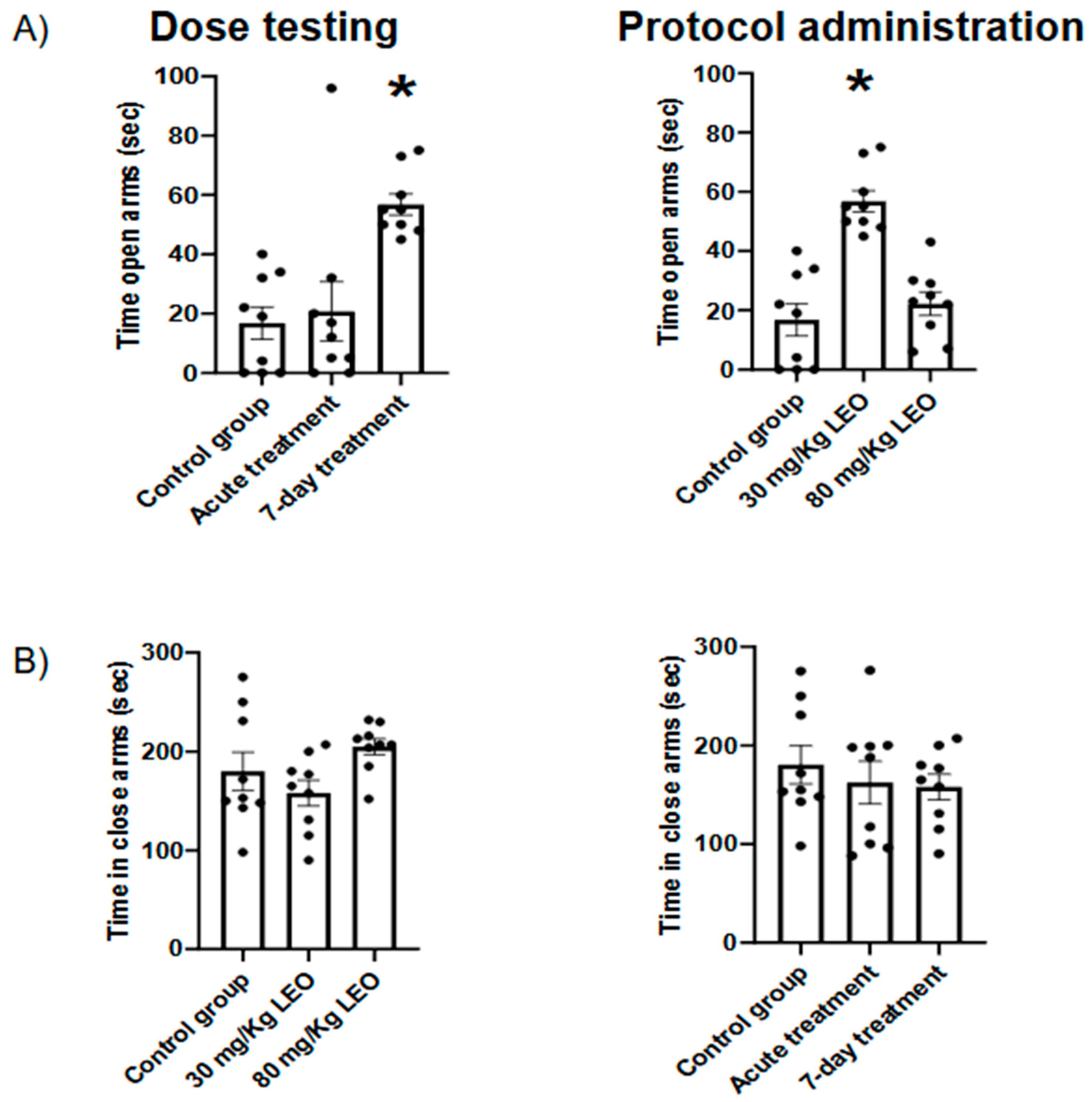

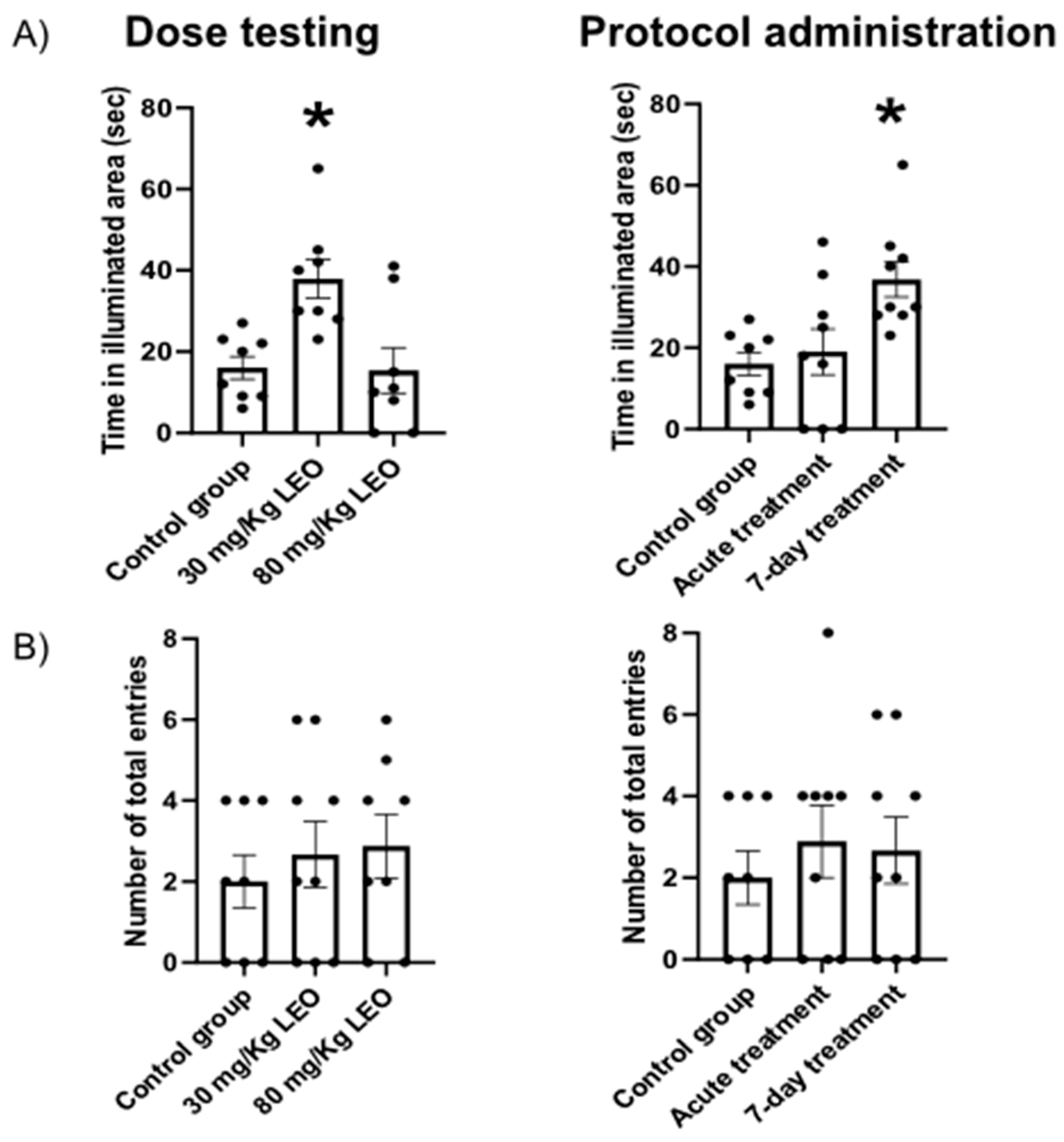

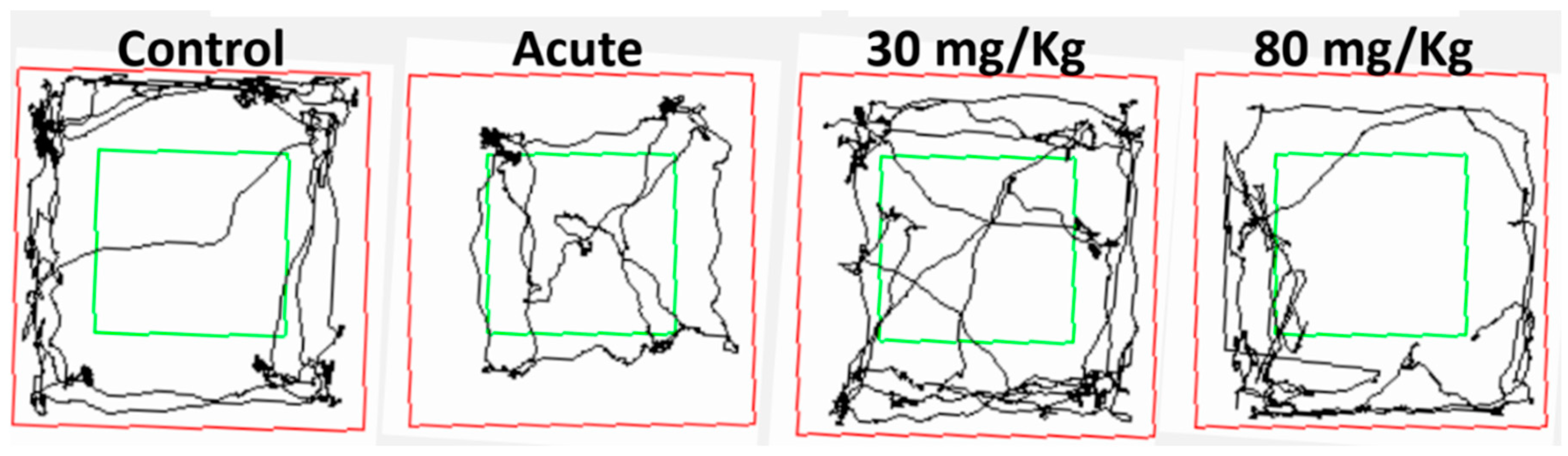

31]. In this sense, we found that the dose of 30mg/kg induced a clear anxiolytic effect in the plus maze, observed as an increased time spent in the open arms, meanwhile, the higher dose showed no significant impact. Moreover, the lower dose was effective under the 7-days protocol, and no significant differences were observed with the acute administration. Similar results were obtained when the animals were evaluated in the dark light test. No significant difference was observed regarding the locomotor activity in either test, supporting the hypothesis that the difference is in the decreased fear/anxiety in the conflict test. This result is also supported by the open field evaluation showing no differences in the locomotor activity.

The results obtained in the present study are consistent with the data reported by Kumar (2013) [

23], using

L. angustifolia essential oil (Silexan®, standardized capsule formulation based on L. angustifolia EO) with the same dose and protocol of administration. Regarding the lack of an anxiolytic effect with the highest dose (80 mg/Kg), we can speculate that we are facing a dose-dependent response. In this sense, it has been described as the "U-shaped effect" for several drugs, where doses that are too high or too low may not cause any effect or even be harmful [

33].

The beneficial effects of LEO on the central nervous system have been related to two of its main components, linalyl acetate and linalool. The results of Lopez and cols. [

34] showed that

L. angustifolia EO and its main therapeutic molecules (linalool and linalyl acetate) interact with glutamate receptors (NMDA), inhibiting them, and generating an anxiolytic effect. Other authors found similar results of LEO on the glutamatergic system [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Also, it has been reported that the hydroxyl group of linalool can bind to the serotonin transporter, which could explain the antidepressant effect reported in some works [

39,

40]. Moreover, it has been reported that Silexan® presents binding potential to serotonin-1A receptors, where its activity was significantly reduced after ingestion of LEO [

41]. Schuwald et al. [

42], using Silexan®, identified that the potent anxiolytic effect is due to the inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels in synaptosomes, observed primary hippocampal neurons, and cell lines with stable overexpression. The same finding was confirmed with linalool in snail neurons, in addition to increasing potassium currents [

43]. Other studies suggest that LEO reversibly inhibits GABA-induced signals. Milanos et al. [

44] showed that only oxygenated metabolites of linalool at carbon 8 positively influence GABAergic currents, and hydroxylated or carboxylated derivatives at carbon 8 were ineffective, while acetylated derivatives of linalool did not produce significant changes, indicating that linalool metabolism reduces its allosteric potential at GABAA receptors compared to the original linalool molecule.

Finally, it is important to note that, according to a systematic analysis by Sattayakhom et al. [

45] based on data from the MEDLINE, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases, 81.43% of EO studies have been conducted in human subjects, 18.57% in animal models, and only 1.43% in vitro cell cultures. Moreover, several of the scientific studies performed on both, animals and humans, showed significant methodological issues, such as small sample sizes, inconsistent administration methods, and a lack of placebo or control groups. In this sense, the data reported in the bibliography concerning subjects under study, the range of doses, protocols, and route of administration is wide and controversial [

46,

47]. We contribute to adding new systematic evidence regarding the effects of EO in the central nervous system; however, more standardized experiments are needed to confirm the benefits of lavender for brain disorders and to better understand its pharmacological and therapeutic potential.

Additionally, despite the pharmaceutical use of LEO in Europe, as far as we know, no evidence has been reported in Latin America; and the LEO formulation is not approved in all countries. In addition, we evaluated the effect of an acute dose, which had not been evaluated behaviorally until now, and we can infer from these results that repeated administration is required to observe a behavioral effect. For this reason, it becomes relevant to characterize a locally produced species of lavender thinking on a future formulation for regional use. In this sense, our study shows for the first time the therapeutic approach to L. burnatii, a Latin American endemic plant, proposing an effective dosage and administration protocol for future preclinical studies to contribute to systematic studies concerning lavender anxiolytic effects.