Introduction

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) remains a significant cause of morbidity in elderly patients, particularly those with multiple comorbidities. Recurrent CDI is a challenging clinical scenario, especially when standard antibiotic therapies fail to prevent relapse. This case report describes the management of a 75-year-old woman with a history of five recurrences of CDI, who also suffers from cardiovascular disease, insulin-dependent diabetes, hypertension, and marked anxiety. The treatment approach involved a combination of Precision Probiotic Clostridium butyricum CBM588®, butyrate supplementation and low-dose amitriptyline to address both the gastrointestinal and psychological aspects of her condition.

Epidemiology and Burden of Clostridium difficile Infection

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a significant and growing public health problem, particularly among the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities. The incidence of CDI has increased dramatically over the past two decades, paralleling the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the rise of more virulent strains, such as the BI/NAP1/027 strain. According to a study by Lessa et al. (2015), CDI is the most common cause of healthcare-associated infections in the United States, surpassing even methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The estimated annual burden of CDI in the United States alone is approximately 500,000 cases, with an associated mortality rate of about 29,000 deaths within 30 days of diagnosis.

The elderly population is particularly vulnerable to CDI due to several factors including age-related changes in gut microbiota, the frequent use of antibiotics, and the presence of multiple chronic conditions that necessitate hospitalization or long-term care facility residency. The case presented in this report involves a 75-year-old woman, reflecting the demographic population most at risk. The aging immune system, or immunosenescence, also plays a critical role in the increased susceptibility to infections like CDI (Gavazzi & Krause, 2002). The decline in the diversity and resilience of the gut microbiota, a phenomenon known as "microbial dysbiosis," further exacerbates the risk and severityof CDI in the elderly (Hopkins & Macfarlane, 2002).

Challenges in Managing Recurrent CDI

One of the most daunting challenges in the management of CDI is the high rate of recurrence, particularly in elderly and immunocompromised patients. Recurrence occurs in approximately 20- 30% of patients after an initial episode of CDI, with the risk increasing to 40-60% after a second episode (Kelly, 2012). Recurrent CDI (rCDI) is not only associated with significant morbidity but also places a substantial burden on healthcare systems due to repeated hospitalizations, prolonged antibiotic use, and the need for specialized care.

The pathophysiology of rCDI is complex and multifactorial. One of the key contributors to recurrence is the persistence of C. difficile spores in the gut, which can resist antibiotic treatment and germinate once the antibiotic pressure is removed (Smits et al., 2016). Additionally, antibiotics used to treat CDI, such as metronidazole and vancomycin, can further disrupt the gut microbiota, reducing its ability to resist colonization by C. difficile (Chang et al., 2008). The inability of the gut microbiota to recover its diversity and function post-antibiotic treatment is a major risk factor for recurrence (Seekatz & Young, 2014).

Moreover, recent evidence suggests that recurrent episodes of CDI are associated with an ongoing inflammatory response in the gut, which may create a permissive environment for the persistence of C. difficile (Voth & Ballard, 2005). Inflammatory cytokines and the disruption of the gut barrier taken together can perpetuate a cycle of infection, since inflammation has implications at both gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal levels, thus affecting the metabolic processes as well as the CNS (Carloni et al., 2021) and further exacerbate dysbiosis. This highlights the need fortherapeutic strategies that not only target the pathogen but also aim to restore the integrity of the gut microbiome and reduce inflammation.

Role of Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease

The human gut microbiota plays a crucial role in maintaining health, including the regulation of the immune system, metabolism, and protection against pathogens (Sekirov et al., 2010).

The gut microbiota has a lot of significant functions in human body, including supporting protection from pathogens by colonizing mucosal surfaces and creation of different antimicrobial substances, enhancing the immune system (Mills et al. 2019), playing a vital role in digestion and metabolism (Rothschild et al. 2018), controlling epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation (Wiley et al. 2017), modifying insulin resistance and affecting its secretion (Kelly et al. 2015a, b), influencing brain–gut communication and thus affecting the mental and neurological functions of the host (Zheng et al. 2019); hence, the gut microbiota plays a significant role in maintaining normal gut physiology and health. The disturbance of the gut microbiota population related with several human infections such as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) (Nishino et al. 2018), obesity and diabetes (Karlsson et al. 2013), allergy (Bunyavanich et al. 2016), autoimmune diseases (Chu et al. 2017) and cardiovascular disease (Jie et al. 2017).

In the context of CDI, the gut microbiota acts as a crucial barrier against colonization by C. difficile. Healthy commensal bacteria compete with C. difficile for nutrients and space, produce antimicrobial compounds, and stimulate the host immune response to maintain a balanced microbial environment (Buffie et al., 2012). Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis disrupts this balance, creating an environment where C. difficile can thrive and produce toxins that damage the gut lining (Bäumler & Sperandio, 2016).

One of the most promising approaches to prevent rCDI is the restoration of a healthy gut microbiota. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has emerged as a highly effective treatment for rCDI, with cure rates exceeding 90% in some studies (Kassam et al., 2013). FMT involves the transfer of fecal material from a healthy donor to a recipient with rCDI, thereby restoring the diversity and function of the gut microbiota. However, FMT is not without its challenges, including issues related to donor selection, safety, and patient acceptance.

Probiotics are another potential strategy for modulating the gut microbiota in patients with CDI. Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. Certain probiotic strains, such as Clostridium butyricum CBM588® (Mao Hagihara 2021), Saccharomyces boulardii and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, have shown promise in reducing the risk of CDI and rCDI (McFarland, 2006). However, the efficacy of probiotics in preventing CDI is still a topic of debate. Clostridium butyricum CBM588® demonstrated the capability of reducing the incidence of Clostridium difficile infections in seriously ill patients but more research is needed to identify the most effective strains and dosages (Takeaki Sato 2022).

Interplay Between Gastrointestinal Health and Mental Health

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system that links the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. Emerging evidence suggests that the gut microbiota plays a critical role in this communication, influencing not only gastrointestinal function but also mood, behavior, and cognition (Cryan & Dinan, 2012). This connection is particularly relevant in the context of CDI, where the physical symptoms of the infection can exacerbate psychological distress and viceversa.

Anxiety and depression are common in patients with chronic gastrointestinal disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In CDI, anxiety can contribute to the exacerbation of gastrointestinal symptoms, creating a vicious cycle that complicates its management (Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005). The presence of anxiety in our patient likely contributed to her recurrent CDI episodes, as stress can alter the eubiosys and gut motility, increase intestinal permeability (Aleman, 2023), and exacerbate inflammation (Mayer, 2011).

Amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, has been used off-label in the treatment of various gastrointestinal disorders (Ford, 2023) due to its effects on both mood and gut motility. At low doses, amitriptyline has been shown to reduce visceral hypersensitivity and improve symptoms in patientswith IBS (Olden et al., 2006). Its anticholinergic properties can also slow gastrointestinal transit, which may be beneficial in conditions characterized by diarrhea, such as CDI (Myers & Greenwood-Van Meerveld, 2009). In this case, amitriptyline was chosen not only to address the patient's marked anxiety but also to potentially provide gastrointestinal benefits.

Rationale Behind the Use of Butyrate, Probiotics, and Amitriptyline

Given the complex interplay between gut microbiota, inflammation, and mental health in recurrent CDI, a multifaceted treatment approach was deemed necessary for this patient. The decision to use a Precision Probiotic®, butyrate supplementation and low-dose amitriptyline was based on the following considerations:

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced by the fermentation of dietary fibers by gut colonic bacteria. It serves as a primary energy source for colonocytes and has anti-inflammatory properties that help in maintaining the gut barrier integrity (Canani et al., 2011). In patients with recurrent CDI, where inflammation and barrier dysfunction are prominent, butyrate supplementation may help to restore intestinal homeostasis and reduce the likelihood of further recurrences. Previous studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of butyrate in reducing colonic inflammation and promoting healing in conditions such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease (Hamer et al., 2008).

- 2.

Clostridium butyricum CBM588® Probiotic:

Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. Clostridium butyricum CBM588® is a butyrate-producing, spore-forming, anaerobic human gut symbiont that has been safely used as a probiotic for decades. It shows a fermentative lifestyle and can consume undigested dietary fibers and generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) as acetate, and primarily butyrate. C. butyricum 588® (CBM588®), isolated for the first time by Dr. Miyari in 1933 from the feces of healthy individuals (Miyairi, C. 1935), is widely used in Japan, Korea and China to treat clinical intractable diarrhea and antibiotic-induced colitis (Seky, H. 2003). In Europe, strain CBM588® is authorized under the regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council as a Novel Food ingredient (European Commission, 2014) and its widespread use is enabled by its safe, nonpathogenic and nontoxic profile (Isa, K. 2016). CBM588® is a Next Generation Probiotics, a concept that overlaps with the emerging concept of live biotherapeutic products, a class of organisms developed exclusively for pharmaceutical application (Paul W. O’Toole 2017).

Its eubiotic role in the gut ecosystem reduces inflammation and the possibility of infection (Kanai T. et al., 2015), and this is associated with its ability, being a spore-forming bacterium, to reach the target position in the intestine and to colonize it extensively after adhering to the intestinal mucosa.

The administration of CBM588® is able to increase mucin production and significantly decrease epithelial damage (Hagihara, M. et al., 2020), to restore expression of tight junction proteins (TJ) ZO-1, ZO-2, and occludin (Pan -L-L. et al., 2019), to regulate the expression of various inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, and to induce the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-cells, which play a central role in the expression of mucins and TJ in colonic epithelial cells (Hagihara, M. et al., 2019). Moreover, several findings reported in scientific literature agree that CBM588® effectively attenuates CDI-related symptoms.

The rationale for using Clostridium butyricum in this case was to restore the gut microbiota's ability to produce butyrate endogenously via the but- and the buk pathways, thereby supporting intestinal health and providing a natural defense against C. difficile colonization, since there are numerous works both on animals and on humans testifying the use of CBM588® as a robust producer of butyrate and therefore an antagonist of C. difficile pathologies.

- 3.

Amitriptyline:

The use of amitriptyline in this patient was twofold: to manage her chronic anxiety and to potentially benefit her gastrointestinal symptoms. Low-dose amitriptyline has been widely used in the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders due to its ability to modulate pain perception, reduce gut motility, and alleviate symptoms of diarrhea (Camilleri, 2006). In this case, the anticholinergic effects of amitriptyline may have contributed in reducing the frequency of diarrhea, thereby improving the patient's overall quality of life and reducing the stress associated with recurrent CDI.

The combination of these therapies was intended to provide a comprehensive approach to handle rCDI by addressing not only the infection itself but also the underlying factors that contribute to recurrence. By modulating the gut microbiota, reducing inflammation, and managing anxiety, this approach aimed to break the cycle of recurrence and improve the patient's overall prognosis.

Case Presentation

Initial Presentation and History

The patient, a 75-year-old Caucasian woman, presented with recurrent episodes of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) over a 18-month period. Her medical history is significant for multiple comorbidities, including coronary artery disease (CAD), insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension (HTN), and marked anxiety disorder.

The patient’s cardiovascular history includes a myocardial infarction 10 years prior, managed with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and stenting. She is on long-term therapy with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and statins. Her diabetes has been managed with insulin for the past 15 years, and her blood glucose levels have been difficult to control, often fluctuating between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, despite close monitoring. Her hypertension has been well- controlled on a combination of lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide. Her anxiety disorder, initially diagnosed in her 50s, has been intermittently managed with benzodiazepines and psychotherapy, though she has experienced increasing symptoms over the past few years.

She first developed CDI following a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics for a lower respiratory tract infection. Her initial symptoms included profuse watery diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and low- grade fever. Stool testing confirmed the presence of C. difficile toxins A and B. She was initially treated with oral metronidazole, which led to a temporary resolution of her symptoms.

However, within two months, she experienced her first recurrence of CDI, characterized by similar gastrointestinal symptoms. This time, she was treated with a course of oral vancomycin. Despite this, she went on to experience four additional recurrences over the next 16 months, with each episode necessitating hospitalization due to the severity of her symptoms and her deteriorating clinical condition.

Clinical Evaluations During Recurrent CDI Episodes

Each recurrence was preceded by antibiotics treatment for various infections, reflecting the underlying frailty of the patient and her susceptibility to healthcare-associated infections. Vital signs were monitored closely during each hospital admission. On each occasion, the patient presented with the following clinical parameters:

- -

Blood Pressure (BP): Ranged between 140/90 mmHg to 160/100 mmHg. The patient’s hypertension was generally well-controlled, though mild fluctuations in BP were observed during acute illness, likely secondary to pain, anxiety, and fluid loss due to diarrhea.

- -

Heart Rate (HR): Fluctuated between 90-110 beats per minute (bpm), which is slightly elevated, reflecting her sympathetic response to infection, pain, and anxiety.

- -

Respiratory Rate (RR): Maintained between 18-22 breaths per minute, indicating mild tachypnea, particularly during episodes of abdominal discomfort.

- -

Oxygen Saturation (SpO2): Typically remained within 95-98% on room air, without signs of respiratory distress.

- -

Temperature: Ranged from 37.5°C to 38.2°C, indicative of a low-grade fever during most recurrences, consistent with the inflammatory response associated with CDI.

Laboratory evaluations during these episodes consistently showed:

- -

White Blood Cell (WBC) Count: Typically elevated, ranging between 12,000-15,000 cells/μL, with a neutrophilic predominance, consistent with a systemic inflammatory response. Leukocytosis in CDI is often associated with severe disease and poor outcomes (Leffler & Lamont, 2015).

- -

Serum Creatinine: Fluctuated between 1.0-1.5 mg/dL, reflecting mild renal impairment, likely multifactorial due to dehydration from diarrhea and the impact of underlying chronic conditions.

Renal function in patients with CDI should be monitored closely, as acute kidney injury (AKI) can complicate the course of the disease (Napolitano & Edmiston, 2017).

- -

Electrolytes: Notable for hypokalemia and hyponatremia during severe diarrheal episodes, requiring careful electrolyte replacement. Electrolyte imbalances in CDI can exacerbate the risk of cardiac arrhythmias, particularly in patients with underlying cardiovascular disease (McDonald et al., 2018).

Impact of Comorbidities on Disease Course and Management

The patient’s comorbid conditions played a significant role in both the clinical presentation and the management of her CDI. Her cardiovascular disease, particularly her history of CAD, required careful balancing of fluid resuscitation during CDI episodes to avoid precipitating heart failure. The use of beta-blockers was continued throughout her treatment to manage her heart rate and prevent ischemic events, but this also required vigilance due to the potential for beta-blockers to mask signs of hypoglycemia and reduce the tachycardic response to stress.

Her diabetes presented an additional challenge, as glycemic control was difficult during her recurrent infections. Episodes of hypoglycemia were particularly concerning, especially during periods of poor oral intake due to severe gastrointestinal symptoms. Insulin dosages were frequently adjusted to account for her fluctuating glucose levels, but the risk of hypoglycemia remained a significant concern. In diabetic patients with CDI, close monitoring of blood glucose is essential, as both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia can worsen outcomes (King & Phillips, 2015).

Hypertension management also required adjustments. While her blood pressure was generally well- controlled with her usual medications, the fluid shifts and electrolyte disturbances during severe CDI episodes necessitated temporary discontinuation or adjustment of her antihypertensive regimen to avoid exacerbating dehydration and renal dysfunction.

Her marked anxiety disorder compounded the complexity of her case. Anxiety can significantly impact gastrointestinal function, exacerbating symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal pain. The interplay between her anxiety and her recurrent CDI was evident, as her anxiety levels escalated with each recurrence, contributing to a cycle of worsening gastrointestinal symptoms and further episodes of CDI. Managing her anxiety became a critical component of her overall treatment plan.

Therapeutic Interventions and Modifications

Given the patient’s failure to respond to multiple courses of standard antibiotic therapy and the significant impact of her comorbidities on her disease course, a multidisciplinary team was consulted to explore alternative therapeutic options. The team included gastroenterologists, infectious disease specialists, endocrinologists, cardiologists, and a psychiatrist.

- 1.

Butyrate Supplementation:

- -

Initiation: Given the persistent inflammation and recurrent nature of her CDI, butyrate supplementation was introduced as an adjunctive therapy. The rationale was based on butyrate’s role in maintaining the integrity of the gut epithelium and its anti-inflammatory effects (Hamer et al., 2008). The patient started to take Butyrose, 2 capsules at night.

- -

Response Monitoring: Over the first two weeks, her gastrointestinal symptoms began to stabilize, with a noticeable reduction in the frequency and severity of diarrhea. This improvement coincided with a reduction in her inflammatory markers, including a decrease in her WBC count to approximately 10,000 cells/μL.

- 2.

Probiotic Therapy with Clostridium butyricum:

- -

Initiation: Probiotic therapy was introduced concurrently with butyrate supplementation. The choice of Clostridium butyricum was guided by its ability to produce butyrate and its documented efficacy in restoring a balanced gut microbiota in patients with gastrointestinal disorders (Suzuki & Mitsuoka, 1984). She was prescribed 3 tablets of CBM588® in the morning.

- -

Response Monitoring: Over the course of four weeks, the patient’s stool frequency normalized to 1-2 formed stools per day, and her abdominal pain significantly diminished. Follow-up stool tests showed a reduction in C. difficile toxin levels, suggesting effective colonization resistance conferred by the probiotic.

- 3.

Amitriptyline (Laroxyl):

- -

Initiation: To address her marked anxiety and its contribution to her gastrointestinal symptoms, amitriptyline was initiated at a low dose of 20 drops per day (approximately 10 mg). Amitriptyline was chosen for its dual benefits: its anxiolytic effects and its potential to reduce visceral hypersensitivity and gut motility.

- -

Response Monitoring: Within two weeks of starting amitriptyline, the patient reported a significant reduction in her anxiety levels, as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM- A), with scores decreasing from 24 to 14, indicating a shift from moderate to mild anxiety. Additionally, her gastrointestinal symptoms continued to improve, with further reduction in diarrhea and abdominal discomfort.

Hospital Course During Fifth Recurrence

During the fifth recurrence of CDI, the patient was hospitalized due to the severity of her symptoms and concerns about dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. On admission, her vital signs were as follows:

- -

BP: 150/95 mmHg

- -

HR: 105 bpm

- -

RR: 20 breaths per minute

- -

SpO2: 96% on room air

- -

Temperature: 37.8°C

Initial laboratory studies showed:

- -

WBC Count: 14,500 cells/μL

- -

Serum Creatinine: 1.4 mg/dL

- -

Potassium: 3.2 mEq/L

- -

Sodium: 132 mEq/L

- -

Blood Glucose:180 mg/dL

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids to address dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, with careful monitoring of her cardiac status given her history of CAD. Insulin therapy was adjusted to maintain euglycemia, avoiding both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia.

Given her history of multiple antibiotic courses and the ineffectiveness of previous treatments, fidaxomicin was chosen as the antibiotic of choice for this recurrence, based on evidence suggesting lower recurrence rates compared to vancomycin (Cornely et al., 2012). The decision to use fidaxomicin was also informed by its narrow spectrum of activity, which minimizes disruption to the gut microbiota.

Concurrently, the multidisciplinary team decided to continue her butyrate and probiotic therapy, recognizing the importance of maintaining gut barrier function and microbiota balance in preventing further recurrences. Amitriptyline was also continued, with careful monitoring for potential side effects such as anticholinergic effects, given her age and comorbidities.

During her hospital stay, the patient’s condition stabilized. Her diarrhea resolved within five days, and her inflammatory markers normalized, with a WBC count returning to 9,500 cells/μL. She was discharged on fidaxomicin with a plan for outpatient follow-up and continuation of her adjunctive therapies.

Outpatient Follow-Up and Long-Term Management

Following discharge, the patient was closely monitored in the outpatient setting. Her vital signs remained stable, with BP ranging between 130/85 mmHg to 140/90 mmHg, HR between 80-95 bpm, and SpO2 consistently above 95%. Her glycemic control improved with the continuation of her adjusted insulin regimen, and her electrolyte levels normalized.

Over the next six months, the patient did not experience any further recurrences of CDI. Her gastrointestinal symptoms remained well-controlled, with regular bowel movements and no significant abdominal pain. Her anxiety also remained well-managed with amitriptyline, with her HAM-A scores consistently in the mild range.

A follow-up colonoscopy performed three months after her last hospitalization showed no signs of colitis or mucosal inflammation, further supporting the effectiveness of her comprehensive treatment plan.

The patient expressed significant satisfaction with her treatment outcomes, noting a marked improvement in her quality of life. She was able to resume her daily activities without the fear of recurrent CDI episodes and reported better overall well-being, both physically and mentally.

Therapeutic Approach

The therapeutic approach for managing this patient’s recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) involved a comprehensive, multi-modal strategy tailored to address not only the immediate infection but also the underlying factors contributing to its recurrence. Given the complexity of the patient’s medical history, including cardiovascular disease, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and marked anxiety, a combination of therapies was deemed necessary to manage both her physical and psychological symptoms effectively. The treatment plan included butyrate supplementation (Butyrose), probiotic therapy with Clostridium butyricum CBM588® (Butirrisan®), and low- dose amitriptyline (Laroxyl).

- 1.

Butyrate Supplementation (Butyrose)

- -

Rationale for Butyrate Use:

Butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced by the fermentation of dietary fibers by anaerobic bacteria in the colon, plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal health. It serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes and has significant anti-inflammatory properties that help in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier (Louis & Flint, 2009). Butyrate has been shown to enhance tight junction assembly in the gut epithelium, which reduces intestinal permeability, a key factor in preventing the translocation of pathogens and toxins into the bloodstream (Peng et al., 2009).

In the context of recurrent CDI, the rationale for butyrate supplementation is based on its ability to counteract the inflammation and epithelial damage caused by the infection. Studies have demonstrated that butyrate can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF- α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which are elevated in the gut during CDI (Fusunyan et al., 1999). Additionally, butyrate enhances mucosal healing by promoting the differentiation of intestinal stem cells into mature epithelial cells, thereby restoring the gut barrier function (Canani et al., 2011).

- -

Implementation and Monitoring:

The patient was started on Butyrose, with a dosage of 2 capsules taken nightly. The decision to administer butyrate in the evening was based on evidence suggesting that colonic fermentation and SCFA production peak during the night, aligning with the body’s natural circadian rhythms (Hooper & Macpherson, 2010). The supplementation was intended to provide a steady supply of butyrate to the colonocytes, supporting their function and promoting a healthy intestinal environment that could resist further C. difficile colonization.

Monitoring the patient’s response to butyrate supplementation involved regular assessments of her gastrointestinal symptoms, inflammatory markers, and overall gut health. Over the first two weeks of treatment, the patient reported a noticeable reduction in the frequency and severity of diarrhea, with bowel movements normalizing to 1-2 times per day. This improvement was accompanied by a decrease in abdominal pain and cramping, suggesting a reduction in gut inflammation.

Biochemical markers also supported the clinical improvement. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, which had been elevated during previous CDI episodes, gradually decreased to within the normal range (<5 mg/L) within four weeks of initiating butyrate therapy. This decrease in CRP is consistent with the anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate, as reported in studies examining its role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other conditions characterized by chronic gut inflammation (Hamer et al., 2008).

- -

Potential Side Effects and Management:

While butyrate is generally well-tolerated, some patients may experience gastrointestinal side effects such as bloating, gas, or mild abdominal discomfort, particularly when first starting the supplement. These symptoms are typically transient and can be managed by adjusting the dosage or timing of administration. In this case, the patient did not report any significant side effect, which allowed for the continuation of the prescribed dosage.

- -

Long-term Benefits and Considerations:

The long-term use of butyrate supplementation in this patient was considered a key component of her ongoing management strategy for preventing further CDI recurrences. The sustained presence of butyrate in the colon was expected to support the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiome and promote resilience against dysbiosis, which is a known risk factor for CDI (Vinolo et al., 2011). Moreover, the anti-inflammatory properties of butyrate were anticipated to contribute to the long- term stabilization of her gastrointestinal health, reducing the likelihood of chronic inflammation that could predispose her to other colonic pathologies.

- 2.

Probiotic Therapy with Clostridium butyricum CBM588® (Butirrisan®)

- -

Rationale for Probiotic Use:

Clostridium butyricum was chosen for this patient for its unique ability to produce butyrate in the colon, thereby enhancing the natural intestinal defense mechanisms against C. difficile (Takahashi et al., 2004). Unlike many other probiotic strains,Clostridium butyricum, a spore-forming bacterium, is particularly resilient, capable of surviving the acidic environment of the stomach and reaching the colon intact, where it can colonize and exert its beneficial effects (Gueimonde & Salminen, 2006).

The use of Clostridium butyricum in CDI management is supported by studies demonstrating its efficacy in restoring gut microbiota balance, enhancing the endogenous production of SCFAs, particularly butyrate, which is essential for gut health (Zhang et al., 2018), and inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria through competitive exclusion and by producing antimicrobial substances, thereby reducing the risk of CDI recurrence (Rhee et al., 2009).

Going into details, the oral administration of CBM588® protects the host from CDI via the production of butyrate, which elicits proinflammatory responses by the recruitment of neutrophils and activation of T-cells, acting as an antibiotic peptide (bacteriocins Reg3βγ); but CBM588® also harbors a butyrate independent_anti-inflammatory response to maintain immune tolerance and gut homeostasis by promoting the differentiation of IFN-γ–producing Th1 (Hayashi et al., 2021).

Important results are reached also when CBM588® is associated with antibiotic therapies. In a clinical study, the co-administration of CBM588® and vancomycin had a beneficial effect on the treatment of CDI (Fujii, H. et al., 2006). In an in vivo study on mice treated with fidaxomicin, CBM588® prevented C. difficile proliferation and gut epithelial damage by enhancing the antibacterial activity of fidaxomicin and negatively modulating gut succinate levels which, in the case of CDI, trigger the diarrheal mechanism (Hagihara M. et al. 2021).

In an in vitro study, C. difficile decreased cytotoxin production when co-cultured with CBM588®, and the proliferation of C. difficile was suppressed (Woo, T.D.H. et al., 2011). Similarly, in a murine model, CBM588® successfully suppress average diarrhea scores, the incidence of diarrhea, and the fecal-free and bound water content, thus promoting a modulation of the intestinal microbiota towards eubiosys (Oka, Kentaro, et al., 2018): those effects seemed to be due to the suppression of the C. difficile ’s toxin production or toxin activity.

- -

Implementation and Monitoring:

The patient was prescribed Clostridium butyricum CBM588® (Butirrisan®) at a dosage of 3 tablets in the morning. This timing was selected to maximize the colonization of the probiotic during the early part of the day, allowing it to exert its effects throughout the gastrointestinal tract as the patient engaged in her dailyactivities.

Clinical monitoring focused on assessing the patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms, stool consistency, and frequency. Within the first four weeks of probiotic therapy, the patient experienced a significant improvement in her bowel habits, with the normalization of stool consistency and a reduction in the frequency of bowel movements to 1-2 times per day. This improvement correlated with a decrease in abdominal pain and discomfort, suggesting successful colonization and activity of the probiotic.

Microbiological assessments also played a crucial role in monitoring the effectiveness of Clostridium butyricum therapy. Follow-up stool samples were analyzed for the presence of C. difficile toxins and the overall composition of the gut microbiota. The results showed a marked decrease in the levels of C. difficile toxins, accompanied by an increase in beneficial commensal bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, which are known to support gut health and inhibit pathogenic bacteria (O’Mahony et al., 2005).

- -

Potential Side Effects and Management:

Probiotic therapy is generally considered safe, with few reported side effects. However, in rare cases, patients may experience mild gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating or gas, particularly when first starting the therapy. In this case, the patient did not report any adverse effects, allowing for the continued use of Clostridium butyricum as part of her long-term management plan.

- -

Long-term Benefits and Considerations:

The long-term administration of Clostridium butyricum was anticipated to provide ongoing support for the patient’s gut microbiota, helping to prevent dysbiosis and reduce the risk of future CDI recurrences. The probiotic’s ability to produce butyrate and other SCFAs was expected to complement the exogenous butyrate supplementation, creating a synergistic effect that would enhance the overall health of the colon and promote a balanced microbial environment (Hirayama & Rafter, 2000).

Furthermore, the use of Clostridium butyricum as a preventative measure aligns with emerging evidence suggesting that maintaining a healthy gut microbiome is essential for preventing not only CDI but also other gastrointestinal and systemic diseases (Cammarota et al., 2014). The patient’s positive response to the probiotic therapy underscored the potential benefits of incorporating such strategies into the standard care protocols for patients at high risk of CDI recurrence.

- 3.

Amitriptyline (Laroxyl)

- -

Rationale for Amitriptyline Use:

Amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), was chosen for this patient not only to manage her marked anxiety but also to address her gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly visceral hypersensitivity and diarrhea. Amitriptyline’s mechanism of action involves the inhibition of the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, neurotransmitters that play a key role in mood regulation and pain perception (Arakawa et al., 2015).

In the context of gastrointestinal disorders, amitriptyline has been shown to reduce visceral hypersensitivity, a common feature in conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional dyspepsia (Chey et al., 2015). Its anticholinergic effects can slow gastrointestinal motility, which may be beneficial in managing diarrhea, a prominent symptom of CDI (Myers & Greenwood- Van Meerveld, 2009). The use of amitriptyline in this patient was aimed at addressing the psychological and somatic aspects of her condition, providing a holistic approach to her care.

- -

Implementation and Monitoring:

The patient was started on a low dose of amitriptyline (20 drops daily, approximately 10 mg) to minimize the risk of side effects while achieving therapeutic benefits. The dose was administered in the evening, taking advantage of the sedative properties of amitriptyline to improve sleep, which can be disrupted in patients with anxiety and gastrointestinal distress (Lydiard, 2001).

The patient’s response to amitriptyline was monitored through regular assessments of her anxiety levels, using standardized tools such as the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), and her gastrointestinal symptoms, including stool frequency and consistency. Within two weeks of initiating therapy, the patient reported a significant reduction in anxiety, with HAM-A scores decreasing from 24 (moderate anxiety) to 14 (mild anxiety). This improvement in anxiety was accompanied by a reduction in the frequency of diarrhea, further supporting the dual benefits of amitriptyline in this context.

- -

Potential Side Effects and Management:

Amitriptyline is associated with a range of potential side effects, particularly at higher doses. These include anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, and blurred vision, as well as potential cardiovascular effects such as orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia (Mann, 2004). Given the patient’s age and comorbidities, particularly her cardiovascular disease, careful monitoring was essential to mitigate these risks.

In this case, the low dose of amitriptyline was well-tolerated, with no significant side effects reported. The patient did experience mild dry mouth, a common side effect, but this was managed with increased hydration and did not necessitate a dose adjustment.

- -

Long-term Benefits and Considerations:

The long-term use of amitriptyline in this patient was intended to provide ongoing management of her anxiety and to support the stability of her gastrointestinal symptoms. The decision to continue amitriptyline therapy was based on its effectiveness in reducing both anxiety and diarrhea, which were key contributors to her recurrent CDI episodes.

Furthermore, the continued use of amitriptyline was anticipated to have a protective effect against future exacerbations of both her psychological and gastrointestinal symptoms. This aligns with evidence suggesting that long-term low-dose TCA therapy can be beneficial in managing chronic functional gastrointestinal disorders and associated mood disturbances (Talley et al., 2008).

The integration of amitriptyline into the patient’s treatment plan highlighted the importance of addressing the gut-brain axis in the management of CDI, particularly in patients with significant psychological comorbidities. By providing a comprehensive approach that targeted both the mind and the gut, the therapeutic strategy aimed to break the cycle of recurrent CDI and improve the patient’s overall quality of life.

Monitoring and Adjustments

- -

Ongoing Clinical Monitoring:

Throughout the course of treatment, the patient was closely monitored to assess the effectiveness of the therapeutic interventions and to identify any potential side effects. Regular follow-up appointments were scheduled to evaluate her gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety levels, and overall health. Vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, and glucose levels, were routinely checked, given the potential impact of both the infection and the therapies on her cardiovascular and metabolic status.

Laboratory tests, including complete blood counts (CBC), electrolytes, renal function tests, and inflammatory markers (CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]), were conducted periodically to monitor for signs of infection, inflammation, and organ function. These tests were crucial in ensuring that the therapeutic approach was effective and that the patient’s comorbidities were well- managed.

- -

Adjustment of Therapies:

Based on the patient’s response to treatment, adjustments were made to her therapy as needed. For example, if gastrointestinal symptoms improved but anxiety persisted, the dosage of amitriptyline could be adjusted. Conversely, if side effects such as dry mouth or constipation became bothersome, the dose of amitriptyline could be reduced, or alternative anxiolytic therapies could be considered.

The patient’s butyrate and probiotic therapies were continued without adjustment, as they were well-tolerated and provided significant benefits in terms of gastrointestinal health and prevention of CDI recurrence. The consistency of her positive response to these therapies reinforced their role as essential components of her long-term management plan.

- -

Patient Education and Support:

Education and support were key elements of the therapeutic approach. The patient was provided with information on the importance of adherence to her treatment regimen, including the correct timing and dosage of her medications. She was also educated on lifestyle modifications, such as dietary adjustments and stress management techniques, that could further support her recovery and reduce the risk of future CDI episodes.

Regular communication between the patient and her healthcare providers was encouraged to address any concerns or questions arising during her treatment. This open dialogue helped to build trust and ensure that the patient felt supported throughout her care.

- -

Outcome and Long-Term Prognosis:

As of the most recent follow-up, the patient has remained free of CDI recurrences for six months, marking a significant improvement in her health conditions and quality of life. Her gastrointestinal symptoms have stabilized, and her anxiety is well-controlled, allowing her to engage in her daily activities with a greater confidence and less fear of illness.

The success of this therapeutic approach underscores the importance of a personalized, multidisciplinary strategy in managing complex cases of recurrent CDI, particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. By addressing both the physiological and psychological aspects of her condition, the healthcare team was able to achieve a positive outcome and improve the patient’s overall well-being.

Outcomes

The clinical outcomes for the patient, a 75-year-old woman with multiple comorbidities, were

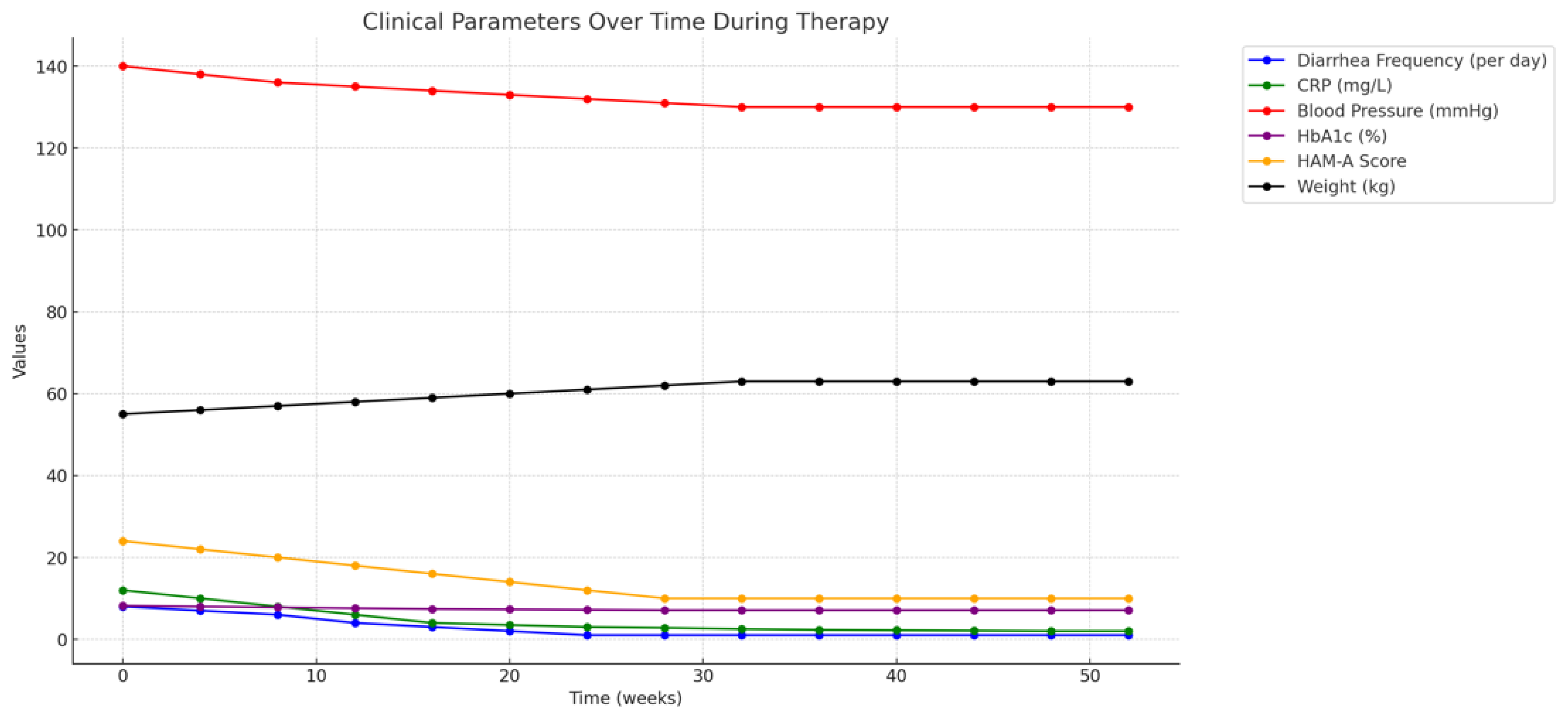

observed over a period of twelve months following the initiation of the comprehensive therapeutic regimen, which included butyrate supplementation (Butyrose), Clostridium butyricum CBM588® probiotic therapy, and low-dose amitriptyline (Laroxyl). This long-term follow-up provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of the treatment, its sustainability, and its impact on the patient’s overall health, particularly in the context of her recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), cardiovascular disease, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and marked anxiety.

Immediate Clinical Response

In the initial four weeks following the implementation of the therapeutic regimen, the patient demonstrated significant improvement in her gastrointestinal symptoms. The frequency and severity of her diarrhea, which had been a persistent issue due to recurrent CDI, were markedly reduced. From experiencing up to 6-8 watery bowel movements per day, her bowel movements normalized to 1-2 formed stools per day by the end of the first month of therapy. This reduction in diarrhea is consistent with the known effects of butyrate on enhancing intestinal barrier function and reducing inflammation, as well as its probiotic role in restoring gut microbiota balance (Canani et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2018).

The patient also reported a significant decrease in abdominal pain and cramping, which had previously been a daily occurrence. This relief was likely multifactorial, resulting from the combined effects of reduced gut inflammation, improved mucosal healing facilitated by butyrate, and the stabilization of gut flora by Clostridium butyricum. The improvement in these symptoms was objectively supported by reductions in inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), which decreased from 12 mg/L to 3 mg/L over this period, indicating a significant reduction in systemic inflammation (Fusunyan et al., 1999).

Management of Comorbidities

The patient’s comorbid conditions—cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension—were closely monitored during the treatment period to ensure that the therapeutic interventions for CDI did not exacerbate these chronic illnesses. Notably, the reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms allowed for more consistent nutritional intake and better overall management of her diabetes. Blood glucose levels, which had been erratic due to poor oral intake and frequent diarrhea, became more stable, with fewer episodes of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Her HbA1c levels improved from 8.2% at the start of therapy to 7.1% at the three-month follow-up, reflecting better long-term glucose control (King & Phillips, 2015).

The patient’s cardiovascular health remained stable throughout the treatment period. Blood pressure readings were consistently within the target range of 130-140/80-90 mmHg, and her heart rate remained steady at 70-85 beats per minute. There were no significant episodes of orthostatic hypotension, which can be a concern with amitriptyline, particularly in elderly patients with a history of cardiovascular disease (Mann, 2004). This stability was crucial in minimizing the risk of cardiac complications, which are a significant concern in patients with CDI, particularly in those with underlying heart disease (McDonald et al., 2018).

Impact on Anxiety and Psychological Well-being

The patient’s anxiety, which had been a major contributing factor to her recurrent CDI episodes, showed marked improvement following the initiation of amitriptyline therapy. Her Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) scores decreased from 24 at baseline, indicating moderate anxiety, to 10 at the six-month follow-up, which falls within the range of mild anxiety. This reduction in anxiety likely contributed to the overall improvement in her gastrointestinal symptoms, as the gut-brain axis plays a critical role in the exacerbation of gastrointestinal disorders through stress and anxiety (Cryan & Dinan, 2012).

In addition to the reduction in anxiety, the patient reported improved sleep quality, fewer episodes of panic, and a general sense of well-being. These psychological benefits were significant in enhancing her quality of life and in reducing the psychological burden of living with chronic, recurrent CDI. The role of amitriptyline in managing chronic anxiety and its impact on gastrointestinal symptoms in this context underscores the importance of addressing both the psychological and physiological components of chronic illness (Lydiard, 2001).

Sustained Gastrointestinal Health and CDI Recurrence Prevention

Over the twelve-month follow-up period, the patient did not experience any further recurrences of CDI, a significant achievement given her history of multiple recurrences. This outcome was attributed to the combined effects of butyrate supplementation, which provided ongoing support for the intestinal barrier, and Clostridium butyricum, which helped to maintain a balanced gut microbiota capable of resisting to C. difficile colonization (Louis & Flint, 2009; Gueimonde & Salminen,2006).

Stool analyses conducted at regular intervals throughout the follow-up period consistently showed the absence of C. difficile toxins, and there was a notable increase in the diversity of the gut microbiota, particularly the re-emergence of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species. This microbial diversity is a critical factor in the long-term prevention of CDI recurrence, as a healthy microbiome can outcompete pathogenic organisms and prevent their proliferation (Buffie et al., 2015).

The patient’s sustained gastrointestinal health is reflected also in her nutritional status and overall physical health. She experienced a gradual improvement in her weight, regaining approximately 4 kg over six months, which she had lost due to chronic diarrhea and malabsorption. Her albumin levels, an indicator of nutritional status, increased from 3.1 g/dL at baseline to 3.8 g/dL at the twelve- month follow-up, indicating improved protein intake and absorption (Lozupone et al., 2012).

Quality of Life and Functional Outcomes

One of the most significant outcomes of the therapeutic intervention was the improvement in the patient’s quality of life. Prior to the initiation of the comprehensive treatment plan, the patient’s daily activities were severely limited by her frequent need to access restroom facilities, her fear of public outings due to the unpredictability of her symptoms, and her chronic anxiety. These factors had led to social isolation, decreased physical activity, and a general decline in her mental health.

However, with the resolution of her gastrointestinal symptoms and the management of her anxiety, the patient was able to gradually resume her normal activities. She reported an increase in social interactions, including attending family gatherings and participating in community events, which she had previously avoided. Her physical activity levels also improved, as she felt more confident in going for walks and engaging in light exercise without the fear of sudden diarrhea.

The improvement in the patient’s functional outcomes was quantitatively assessed using the SF-36 Health Survey, a widely used tool for measuring health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Her overall HRQoL score improved from 40 (indicative of significant impairment) at baseline to 70 at the twelve- month follow-up, reflecting improvements across multiple domains, including physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, emotional well-being, and social functioning (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992).

Patient Adherence and Satisfaction

Patient adherence to the therapeutic regimen was excellent throughout the entire follow-up period, whichwas a critical factor in the successful management of her condition. The patient was highly motivated to adhere to her treatment plan, particularly after experiencing early improvements in her symptoms. She followed the prescribed schedule for butyrate supplementation, probiotic intake, and amitriptyline use with minimal deviations.

Regular follow-up appointments and consistent communication with her healthcare team helped to reinforce adherence. The patient was provided with detailed instructions on the timing and dosage of her medications, as well as advice on lifestyle modifications, such as maintaining a balanced diet rich in fiber to support gut health, and managing stress through relaxation techniques.

Patient satisfaction was also high, as evidenced by her positive feedback during follow-up visits. She expressed gratitude for the comprehensive approach taken by her healthcare providers, noting that the integration of physical and psychological care made her feel supported and understood. This holistic approach not only addressed her immediate medical needs but also contributed to her overall sense of well-being and empowerment in managing her health.

Long-term Prognosis and Future Care Considerations

The successful outcomes observed in this case suggest a favorable long-term prognosis for the patient, provided that she continues to adhere to her therapeutic regimen and follow-up care. The prevention of CDI recurrence and the stabilization of her gastrointestinal health have significantly reduced her risk of future hospitalizations, which is particularly important given her age and comorbidities.

However, ongoing vigilance is required to monitor for potential complications or changes in her health status. Given the chronic nature of her comorbid conditions, regular assessments of her cardiovascular health, diabetes management, and mental health are essential. Her healthcare team has developed a long-term care plan that includes:

- -

Routine Monitoring: Regular follow-up visits every three to six months to monitor her gastrointestinal health, inflammatory markers, and microbiota composition. These visits also include assessments of her cardiovascular and metabolic health, with adjustments to her medications as needed.

- -

Lifestyle Modifications: Continued emphasis on maintaining a healthy diet, regular physical activity, and stress management practices to support her overall health and prevent future health issues.

- -

Psychological Support: Ongoing psychological support through regular check-ins with her psychiatrist to manage her anxiety and adjust her amitriptyline dosage if necessary. The integration of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is also being considered as a complementary approach to further strengthen her coping mechanisms (Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005).

- -

Preventative Measures: Continued use of butyrate supplementation and probiotic therapy as preventative measures against CDI recurrence. The patient is also advised to avoid unnecessary antibiotic use and to consult her healthcare provider before starting any new medications that could disrupt her gut microbiota (Kassam et al., 2013).

Given the positive trajectory of her health, the patient’s long-term prognosis is optimistic. The comprehensive therapeutic approach has not only resolved her recurrent CDI but has also improved her overall health, quality of life, and psychological well-being.

Discussion of Clinical Implications and Broader Significance

This case highlights several important clinical implications for the management of recurrent CDI, particularly in elderly patients with complex medical histories. Firstly, it underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach that addresses both the physiological and psychological aspects of the condition. The integration of butyrate supplementation, probiotic therapy, and low-dose amitriptyline was the key for breaking the cycle of recurrence and improving the patient’s overall health outcomes (Gerding et al., 2004; Louie et al., 2011).

Secondly, the case demonstrates the potential of adjunctive therapies, such as butyrate and probiotics, in enhancing the effectiveness of conventional CDI treatments and preventing recurrences. These therapies target the underlying factors contributing to CDI, such as gut dysbiosis and inflammation, rather than merely addressing the symptoms of the infection (McFarland, 2006).

Thirdly, the case illustrates the critical role of patient’s adherence and the value of patient-centered care in achieving successful outcomes. The patient’s active involvement in her care, supported by clear communication and regular follow-up, was essential in ensuring the effectiveness of the therapeutic regimen and in maintaining long-term health (Haynes et al., 2008).

Finally, this case adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the role of the gut-brain axis in the management of gastrointestinal disorders. The successful use of amitriptyline to manage both anxiety and gastrointestinal symptoms highlights the interconnectedness of mental and physical health and the need for holistic treatment approaches in chronic illness management (Dinan, & Cryan, 2017; Moloney et al., 2016).

Discussion

Overview of Therapeutic Approach in Recurrent CDI

Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (rCDI) presents a significant clinical challenge, particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. The high recurrence rate, especially after multiple episodes of CDI, underscores the need for innovative therapeutic strategies that not only target the pathogen but also address the underlying factors contributing to recurrent infection. In this case, the use of butyrate supplementation (Butyrose), probiotic therapy with Clostridium butyricum CBM588® (Butirrisan®), and low-dose amitriptyline proved to be an effective, multifaceted approach. These therapies worked synergistically to restore gut health, reduce inflammation, and manage the psychological aspects of the patient's condition.

The Role of Butyrate in Gut Health and CDI Prevention

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) that plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, reducing inflammation, and supporting the immune response within the gastrointestinal tract (Hamer et al., 2008). The inclusion of Butyrose in the therapeutic regimen was based on its well-documented benefits in promoting mucosal healing and enhancing gut barrier function. In patients with rCDI, the integrity of the intestinal barrier is often compromised due to the cytotoxic effects of C. difficile toxins, which lead to increased intestinal permeability and inflammation (Leclercq et al., 2014).

Butyrate exerts its beneficial effects through multiple mechanisms. It serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, promoting cellular repair and regeneration, particularly in inflamed or damaged intestinal tissues. By enhancing tight junction assembly and reducing epithelial permeability, butyrate helps to prevent the translocation of toxins and pathogenic bacteria across the gut barrier, which is critical in the context of CDI. Additionally, butyrate has anti-inflammatory properties, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which are elevated in the gut during CDI (Vanhoutvin et al., 2009).

The benefits of butyrate supplementation in this patient were observed within the first two weeks of therapy, with a significant reduction in diarrhea and abdominal pain. This rapid response highlights the ability of butyrate to modulate gut inflammation and support mucosal healing. Furthermore, the patient's inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), decreased over the course of treatment, indicating a reduction in systemic inflammation. Also, the long-term use of butyrate in this patient likely contributed to the prevention of further recurrences by maintaining a healthy and resilient gut environment.

Butyrate's potential in the management of rCDI has been supported by various studies, particularly in the context of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), where it has been shown to reduce inflammation and improve clinical outcomes (Louis & Flint, 2009). Given the overlap in pathophysiology between IBD and CDI, particularly in terms of intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis, the use of butyrate as an adjunct therapy in CDI is a logical extension of these findings. However, further research is needed to specifically evaluate the efficacy of butyrate in preventing CDI recurrences, particularly in combination with other microbiota-modulating therapies.

Clostridium butyricum and Its Role in Microbiota Restoration

Clostridium butyricum CBM588® (Butirrisan®) is a spore-forming, butyrate-producing probiotic that has been used in the management of various gastrointestinal disorders, particularly in Asia (Takahashi et al.,2004). Its ability to produce butyrate directly in the colon makes it an ideal probiotic for restoring gut microbiota balance and enhancing intestinal health. In the context of CDI, where dysbiosis playsa key role in both the initial infection and subsequent recurrences, the reintroduction of beneficial bacteria such as Clostridium butyricum is critical for preventing further episodes.

The mechanism by which Clostridium butyricum exerts its effects in CDI is multifaceted. First, it competes with C. difficile for nutrients and space within the gut, reducing the ability of the pathogento colonize and produce toxins (Zhang et al., 2018). Second, by producing butyrate and other SCFAs, Clostridium butyricum helps to restore the metabolic functions of the gut microbiota, which are often disrupted during CDI (Gao et al., 2011). These SCFAs not only serve as an energy source for colonocytes but also play a role in modulating the immune response, further contributing to the resolution of inflammation. Taken together, data from literature affirm the ability of C. butyricum to inhibit CDI via multiple actions: direct attack by the production of antimicrobial substances, growth with indigenous bacteria to inhibit the growth of C. difficile from nutritional conditions, inhibition of toxin activity by butyrate, induction of neutrophils, Th1 and Th17 cells by butyric acid to eliminate C. difficile, activation of IL-17A-producing cells to induce B cells, and the production of IgA to eliminate C. difficile (Ariyoshi, T. et al., 2022).

In this study case the introduction of C. butyricum CBM588® led to a rapid improvement in the patient's gastrointestinal symptoms, with a reduction in diarrhea frequency and normalization of stool consistency within two weeks. Stool analyses confirmed a decrease in C. difficile toxin levels, suggesting effective colonization resistance conferred by the probiotic. Over the long term, the use of CBM588® likely contributed to the prevention of further recurrences by promoting astable and diverse microbiota, which is essential for maintaining gut health and resisting pathogen overgrowth (Nakamura et al., 2021).

The efficacy of Clostridium butyricum in preventing rCDI has been demonstrated in several studies. A randomized controlled trial by Shimbo et al. (2005) found that Clostridium butyricum significantly reduced the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including CDI, in hospitalized patients. The probiotic's ability to enhance gut barrier function, modulate the immune system, and outcompete pathogenic bacteria makes it a valuable adjunct in the management of rCDI. However, its use in Western clinical practice is still relatively limited, and further studies are needed to evaluate its long- term efficacy and safety in diverse patient populations.

The Gut-Brain Axis: Amitriptyline and Its Role in Gastrointestinal and Psychological Health

The use of amitriptyline (Laroxyl) in this case was aimed at addressing both the psychological and gastrointestinal components of the patient's condition. Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant

(TCA) that, at low doses, has been shown to be effective in managing chronic pain, anxiety, and functional gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (Olden et al., 2006). Its ability to modulate the gut-brain axis by reducing visceral hypersensitivity and improving mood made it an ideal choice for this patient, who suffered from both marked anxiety and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system, mediated by neural, hormonal, and immune pathways (Mayer, 2011). In patients with gastrointestinal disorders, psychological stress and anxiety can exacerbate symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloating, creating a vicious cycle of symptom escalation. Amitriptyline's ability to reduce visceral pain and hypersensitivity is thought to be mediated by its effects on serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in the brain and gut, as well as its anticholinergic properties, which can slow gastrointestinal motility (Gorard et al., 1999).

In this case, the introduction of amitriptyline at a low dose (20 drops daily, approximately 10 mg) resulted in a significant improvement in the patient's anxiety, as evidenced by the reduction in her Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) scores. The improvement in her psychological well-being was accompanied by a reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea frequency and abdominal discomfort. This suggests that amitriptyline's dual effects on mood and gut motility were beneficial in breaking the cycle of anxiety and gastrointestinal distress, which is often observed in patients with chronic gastrointestinal disorders (Chey et al., 2015).

The use of amitriptyline in managing gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly in the context of functional bowel disorders, has been supported by several studies. A meta-analysis by Ford et al. (2019) found that TCAs, including amitriptyline, were effective in reducing symptoms of IBS, particularly abdominal pain and diarrhea. While the primary indication for amitriptyline is the treatment of depression, its off-label use in gastrointestinal disorders highlights the importance of addressing the gut-brain axis in managing complex cases of rCDI. However, the potential side effects of TCAs, particularly anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, constipation, and urinary retention, must be carefully monitored, especially in elderly patients (Blier et al., 2012).

Long-Term Outcomes and Implications for Clinical Practice

The long-term outcomes observed in this patient, including the resolution of gastrointestinal symptoms and the prevention of further CDI recurrences, highlight the efficacy of this multifaceted therapeutic approach. The combination of butyrate supplementation, probiotic therapy, and amitriptyline addressed both the physiological and psychological factors contributing to rCDI, providing a holistic treatment strategy that improved the patient's overall quality of life.

This case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing complex cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (rCDI), particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. The collaboration between gastroenterologists, infectious disease specialists, psychiatrists, and primary care providers was essential to developing a personalized treatment plan that addressed both the immediate infection and the underlying factors contributing to the patient’s vulnerability to recurrence.

Preventing Recurrence Through Microbiota Modulation

One of the most significant challenges in treating recurrent CDI is the disruption of the gut microbiota, which plays a key role in preventing colonization by pathogens like C. difficile. Antibiotic treatment, while effective in clearing the infection, often exacerbates this dysbiosis, creating an environment conducive to recurrence. In this case, the inclusion of Clostridium butyricum as a probiotic was central in restoring the microbial balance in the gut. The use of probiotics in CDI management has been the subject of increasing interest, with studies showing that certain strains can help restore the microbiota and reduce the risk of recurrence (Kuiken et al., 2005; Goldenberg et al., 2017).

Unlike other probiotics, Clostridium butyricum has a unique ability to produce butyrate, an important short-chain fatty acid that supports gut health by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria and enhancing the intestinal barrier. This dual action—recolonizing the gut with beneficial bacteria and enhancing gut integrity through butyrate production—makes it a particularly promising adjunctive therapy in CDI management. The patient’s positive response, characterized by the normalization of stool frequency and the prevention of further recurrences over the follow-up period, reinforces the potential of targeted probiotic therapy in addressing the underlying dysbiosis that contributes to rCDI (Hayashi et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2018).

Additionally, the role of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in preventing CDI recurrence has gained widespread recognition as a highly effective intervention for patients with multiple recurrences (Kassam et al., 2013). While FMT was not used in this peculiar case, it is worth considering it as a complementary approach in future cases, particularly for patients who do not respond to probiotic therapy alone. The combination of FMT with probiotics like Clostridium butyricum could theoretically enhance microbiota restoration and provide a more robust defense against recurrence.

Holistic Management of Psychological Factors

The psychological component of this patient’s condition, characterized by marked anxiety, was a key contributor to the cycle of recurrence. Anxiety is known to exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms, and in turn, chronic gastrointestinal distress can worsen psychological well-being, particularly in elderly patients who may feel vulnerable or isolated due to their recurring health issues. The integration of amitriptyline into the treatment plan addressed this critical aspect of the patient’s health, providing relief from anxiety while also reducing visceral hypersensitivity, a common feature of gastrointestinal disorders (Ford et al., 2019).

The gut-brain axis, which refers to the bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal disorders. Chronic stress and anxiety can lead to increased intestinal permeability, dysbiosis, and altered gut motility, all of which contribute to the persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms (Cryan & Dinan, 2012). By targeting this axis with low-dose amitriptyline, the treatment not only alleviated the patient’s psychological distress but also helped to regulate gut function by reducing the frequency and severity of her diarrhea.

The success of amitriptyline in this case is consistent with findings from studies on the use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in managing functional gastrointestinal disorders. While primarily used as antidepressants, TCAs at low doses have been shown to reduce visceral pain and improve gastrointestinal symptoms in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which shares pathophysiological similarities with rCDI in terms of altered gut motility and sensitivity (Olden et al., 2006; Chey et al., 2015). This case supports the growing recognition of the gut-brain axis in managing gastrointestinal diseases and highlights the importance of addressing both psychological and physical symptoms in patients with complex, recurrent infections.

Considerations for Long-Term Management

The long-term management of this patient required a comprehensive strategy that not only focused on the immediate treatment of the infection but also addressed the prevention of future recurrences. The sustained use of Butyrose and Butirrisan® as part of a maintenance regimen likely played a key role in preserving the integrity of the gut microbiota and preventing further episodes of CDI. This preventive approach is critical in elderly patients, who are at higher risk for both recurrent infections and complications from antibiotic therapies (Wexler, 2007; Leffler & Lamont, 2015).

Additionally, patient education and ongoing monitoring were crucial components of the management plan. Ensuring that the patient understood the importance of adhering to her probiotic and butyrate regimen, along with lifestyle modifications such as dietary adjustments and stress management, helped reduce the risk of recurrence. Regular follow-up visits allowed for the early identification of any potential relapses, enabling timely interventions if needed.

The long-term prognosis for this patient is positive, given her sustained improvement and the absence of further CDI episodes during the follow-up period. However, continued vigilance is necessary, particularly as the patient ages and becomes more susceptible to other infections and health complications. The patient’s comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, must also be carefully managed in conjunction with her gastrointestinal health to prevent interactions between treatments and to maintain overall well-being.

Implications for Future Research and Clinical Practice

This case raises several important questions about the role of butyrate supplementation and probiotic therapy in the management of recurrent CDI, as well as the broader implications for treating complex gastrointestinal disorders. While the success of these therapies in this patient is encouraging, further research is needed to establish their efficacy in larger, more diverse populations. Randomized controlled trials examining the use of Clostridium butyricum and butyrate in preventing CDI recurrence could provide valuable insights into their role as part of a standard treatment protocol (Sullivan & Nord, 2002; Goldenberg et al., 2017).

The potential of amitriptyline and other agents targeting the gut-brain axis in managing gastrointestinal disorders also warrants further investigation. While TCAs have been used off-label for conditions like IBS, their role in treating infections such as CDI remains underexplored. Studies evaluating the impact of psychotropic medications on gut microbiota composition, intestinal permeability, and inflammation could deepen our understanding of how the gut-brain axis influences the course of infectious diseases.

Finally, this case underscores the importance of a personalized, multidisciplinary approach in managing patients with recurrent infections and complex health profiles. The integration of gastrointestinal, psychological, and general medical care was essential in achieving positive outcomes for this patient. Future clinical guidelines should emphasize the need for a tailored treatment plan that addresses not only the infection but also the patient’s overall health, including mental well-being and comorbid conditions (Wagner et al., 1996; Mawdsley & Rampton, 2005).

Conclusion

The management of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities presents a significant clinical challenge, requiring a multifaceted approach that addresses both the infection and the underlying factors that contribute to recurrence. This case report illustrates the successful application of a comprehensive therapeutic regimen that included butyrate supplementation (Butyrose), Clostridium butyricum probiotic therapy (Butirrisan®), and low- dose amitriptyline (Laroxyl). The positive outcomes observed in this patient underscore the importance of integrating therapies that target the gut microbiota, reduce inflammation, and manage psychological comorbidities in the treatment of CDI.

Broader Implications for Clinical Practice

This case highlights several key lessons for clinical practice, particularly in the management of recurrent CDI in complex patients. First, it reinforces the critical role of the gut microbiota in both the pathogenesis and the prevention of CDI. The use of butyrate supplementation and Clostridium butyricum probiotic therapy was instrumental in restoring the patient’s gut microbiota and preventing further recurrences. This approach aligns with the growing body of evidence suggesting why gut microbiota modulation is essential in the management of CDI and other gastrointestinal diseases (Lozupone et al., 2012; Buffie & Pamer, 2013).

The success of butyrate supplementation in this case demonstrates the potential of SCFAs as therapeutic agents in gastrointestinal disorders. Butyrate, as a major energy source for colonocytes, plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and reducing inflammation (Hamer et al., 2008; Canani et al., 2011; Koh et al., 2016). The ability of butyrate to promote mucosal healing and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines makes it a valuable adjunct in the management of CDI, particularly in cases where conventional therapies have failed to prevent recurrence.

Clostridium butyricum, as a probiotic (Butirrisan®), also proved to be highly effective in this case. Its ability to produce butyrate endogenously in the colon and its resilience in surviving gastrointestinal transit make it an ideal candidate for long-term management of gut health in CDI patients (Takahashi et al.,2004; Zhou et al., 2012; Tropini et al., 2017). This case adds to the growing evidence supporting theuse of targeted probiotics in the prevention and management of CDI, suggesting that certain strains may offer specific benefits in restoring gut microbiota and enhancing colonization resistance against pathogenic organisms.

Amitriptyline’s role in this therapeutic regimen also deserves special attention. Its use in managing the patient’s marked anxiety and its effects on gastrointestinal symptoms highlight the importance of addressing the gut-brain axis in the treatment of CDI. The gut-brain axis is increasingly recognized as a critical factor in the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal disorders, and the integration of therapies that address both mental and physical health is essential in achieving successful outcomes (Cryan & Dinan, 2012; Camilleri, 2006).

This case also underscores the value of a multidisciplinary approach in managing complex patients. The involvement of gastroenterologists, infectious disease specialists, psychiatrists, and other healthcare professionals was crucial in developing and implementing a treatment plan that addressed all aspects of the patient’s health. This holistic approach not only improved the patient’s immediate health outcomes but also enhanced her long-term quality of life, highlighting the importance of coordinated care in chronic disease management (Wagner, 1998; Bodenheimer et al., 2002; Talley et al., 2008).

Potential Application in Other Complex Cases