Once the installation of solar panels for the fire detection system network has been verified, an analysis was carried out from an economic, legal and sustainable point of view. The results are shown in the following sections.

3.1. Economic Analysis

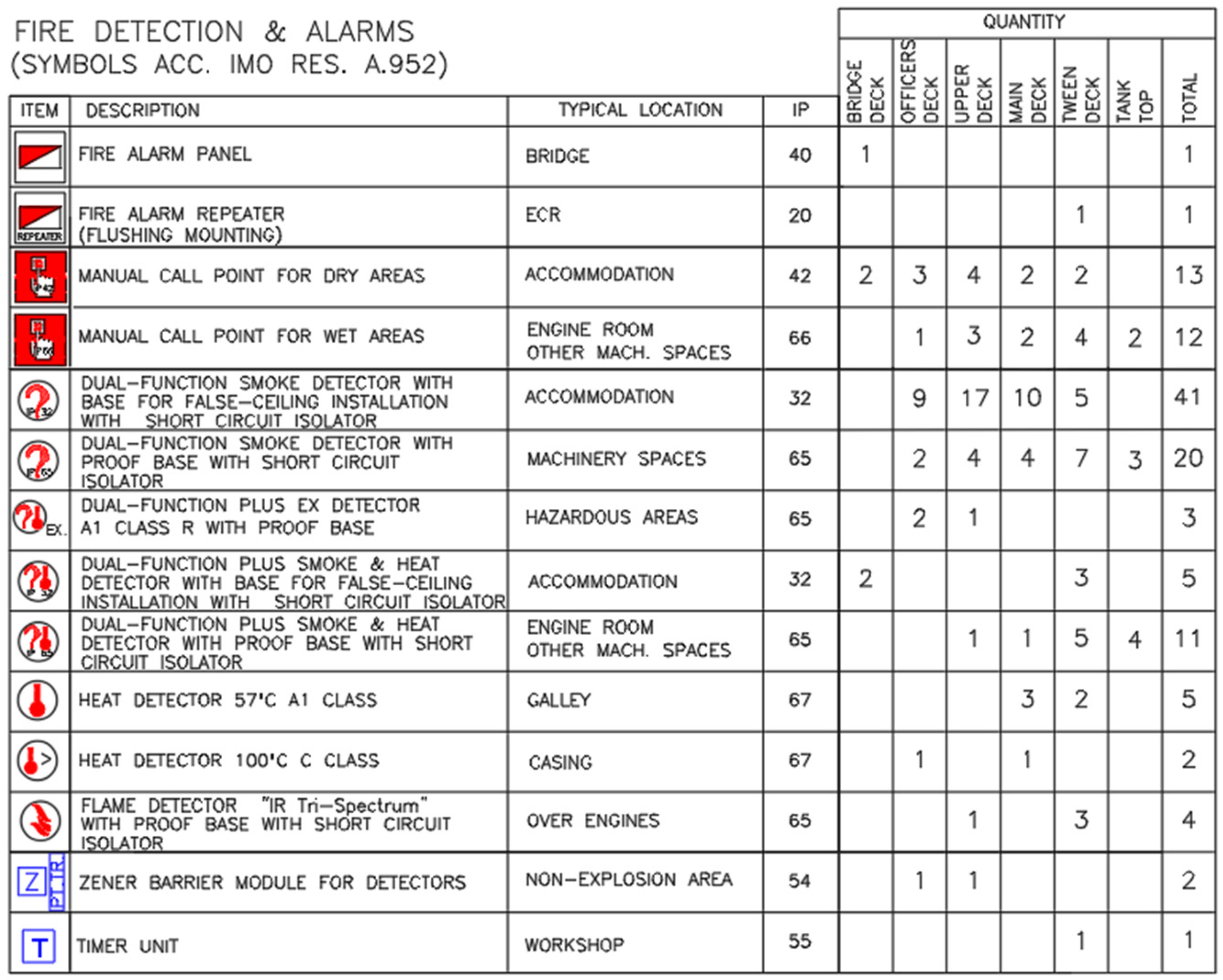

This section analyzes both the investment required and the consumption in tons of marine diesel oil (MDO) for one year to power the fire detection system for several alternatives. It has been taken into account that the ship is out of port 200 days per year, while the rest of the time it is in port and powered by the shore power to the port network (this part is outside the scope of this work).

Alternative 1

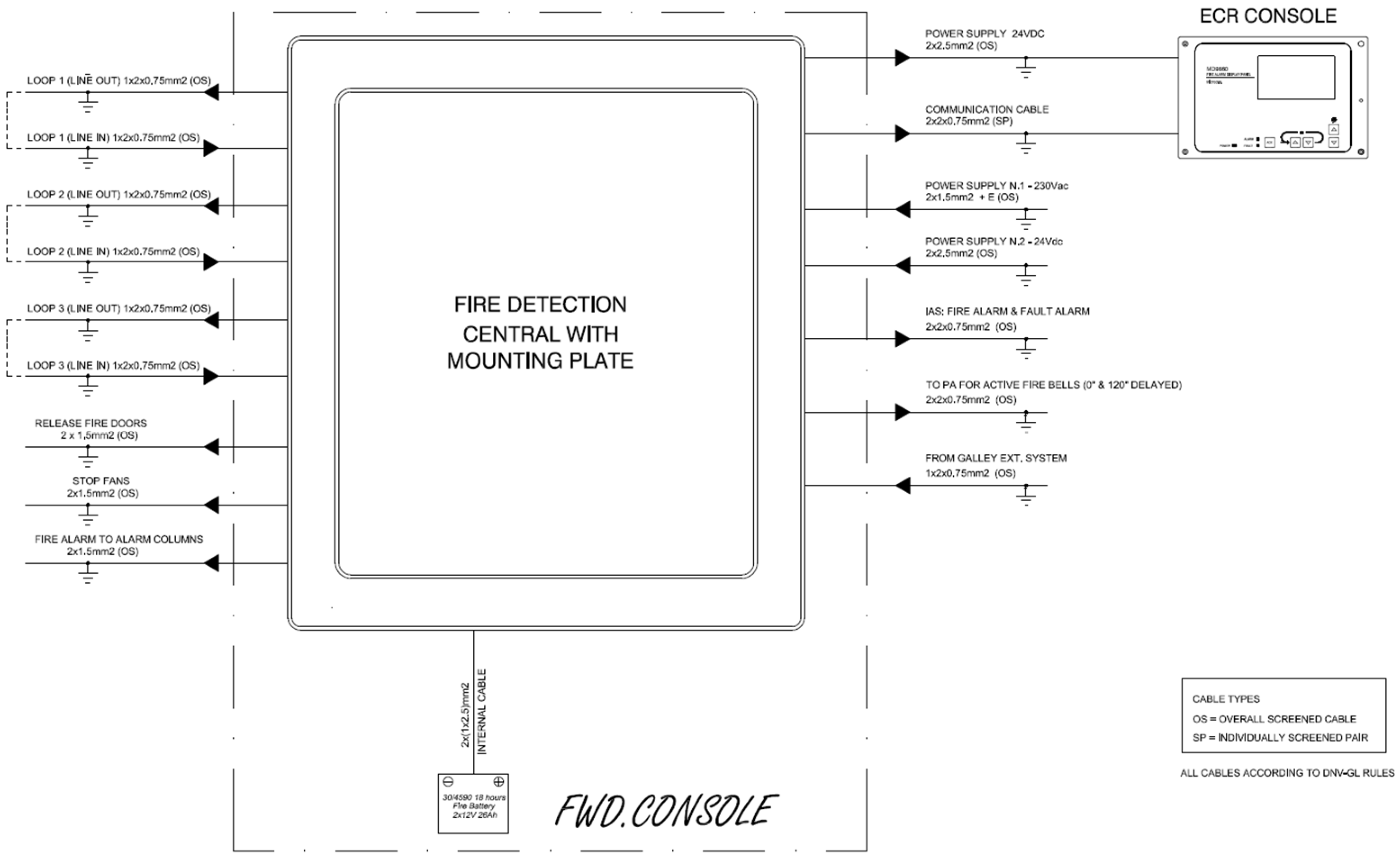

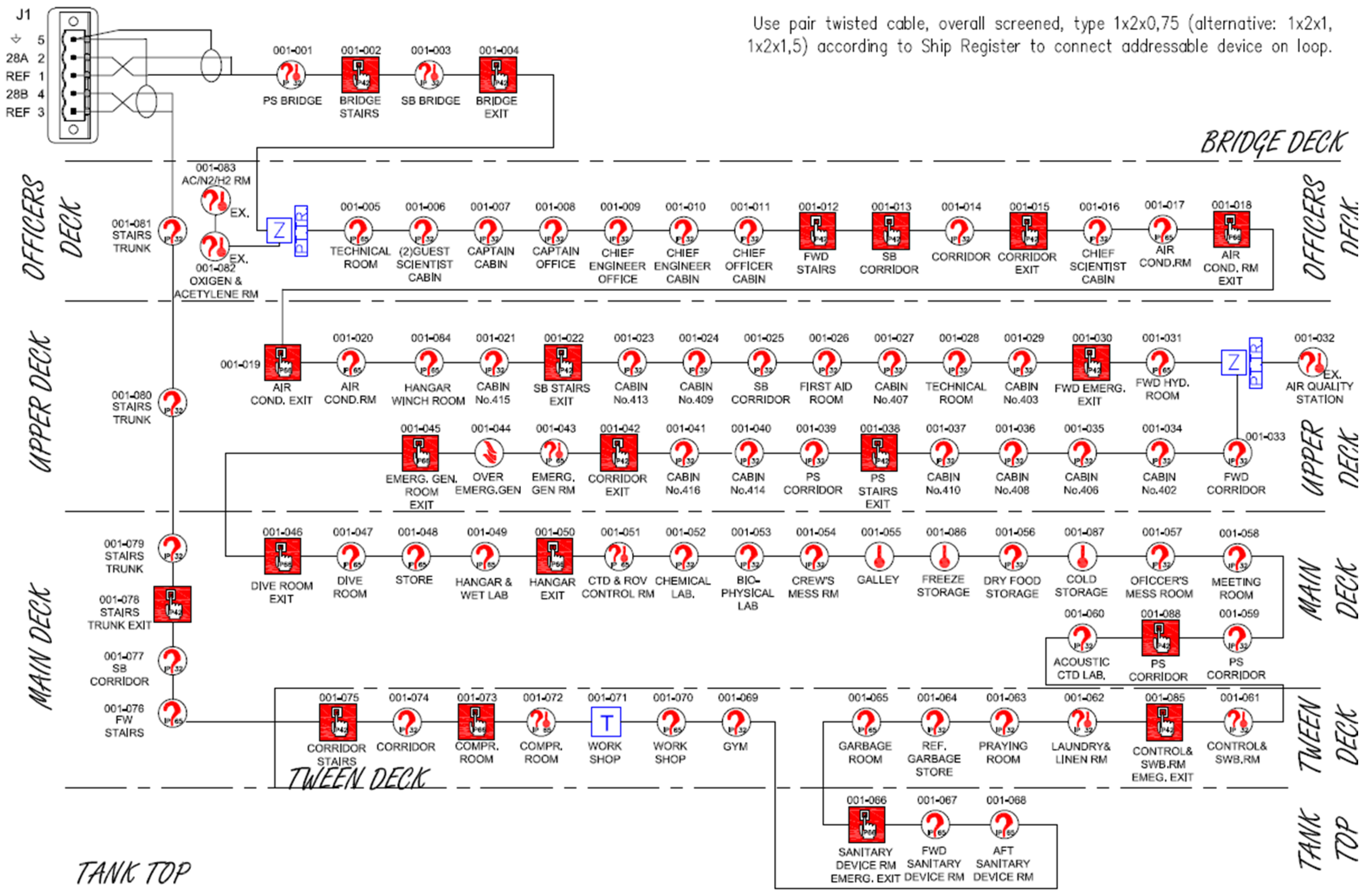

The detection system is powered only from the ship’s 230 Vac emergency mains (via interconnection to the 230 Vac main switchboard), where an AC/DC converter is installed to supply the fire detection system at 24 Vdc, in addition to the emergency mains. Under these conditions, the investment planned is shown in

Table 5.

In addition to this initial investment, the consumption of MDO that must be consumed in the generator set to power the system must be taken into account. An average consumption of the generators of 180 gr/kWh is considered, which is equivalent to 180 gr/kWh x 0.72 kWh/day x 200 days = 25.93 kg of fuel per year. Taking into account the current price of MDO being around 761 $/t (700 €/t), this is equivalent to 18.15 €/year, which considering a useful life of 25 years would amount to 469 €.

Alternative 2

Normal power supply is provided solely by solar panels installed on the decks with sufficient capacity to keep both the fire detection battery charged and the operating system running when the sun is shining. The rest of the power generated by the panels is used for charged a battery system 2 x 100 Ah—2 x 12 Vdc, in order to power supply the system in nights (10 hours with sun/day). The investment is shown in

Table 6.

Although this solution is technically feasible, it is forbidden by SOLAS and also its implementation would mean that during large periods where there is no sun, the system would go into emergency mode and would be powered from its own batteries, which would quickly decrease the life of the batteries and the system would not be prepared for a real emergency of the ship, so it would be necessary to have at least one power supply from the emergency network for at least eight hours a day, as it is shown on alternative 3.

Alternative 3

A solar panel with sufficient capacity to keep the system operational and the fire detection batteries charged is proposed with solar batteries for keep the rest of the generated power supply and power supply the fire detection system on nights, as well as an auxiliary power supply so that in the event of insufficient voltage being generated by the solar panels or by its solar batteries , it would switch to the ship’s emergency 230 Vac network, which would keep the system always operational from the ship’s networks and also the battery always charged. This solution would be a combination of the above situations together with an automatic changeover system so that the power supply to the solar panels would be prioritized. The investment is shown in

Table 7.

In addition to this investment, it will not be necessary to consider any fuel consumption given that the power supply of the fire system from the onboard emergency net will be an unusual situation.

In order to have a quantification of the saving obtained by alternative 3 versus alternative 1, the following economic parameters will be estimated: NPV (Net Present Value), IRR (Internal Rate of Return) and DPBP (Discounted Pay-Back Period).

The NPV, Equation (1), is the present value of the cash flows at the required rate of return of economic savings generated of MDO consumption compared to the investment of alternative 3.

(1)

where i is the required return or discount rate and t the number of time periods.

The IRR is calculated by solving the previous NPV expression for the discount rate required to make the NPV equal to zero, Equation (2).

(2)

The DPBP refers to the amount of time it takes to number of years it takes to break even from undertaking the initial expenditure, Equation (3).

(3)

Where the cash flow is considered the revenue between the yearly cost of the MDO consumption of the alternative 1 (18.74 €/year).

The following values were obtained:

-NPV: Considering a useful life of 25 years and a discount rate of 12%, considering an initial investment of 1995.72 € and an expected annual savings of 18.74 €, an estimated NPV of -1849 € was obtained. Giving that this value is negative, the installation of the solar panel is unprofitable from an economic point of view.

-IRR: Considering the previous values, the rate that makes the NPV zero is -35.3%. Giving that this value is negative, the sum of post-investment cash flows is less than the initial investment.

-DPBP: 37 years. The discounted pay-back period is more than the lifespan of the ship.

These results show that, from an economic point of view, the installation of solar panels does not pay off for supplying energy to small consumers as the installation cost is too high compared to supplying energy by means of a diesel generator.

Given the negative previous result, the main conclusion is that it is advisable to install as many panels as possible. Taking into account the different layouts of merchant vessels, it would normally be possible to install around 20 solar panels (550 Wp per panel) on a typical bridge deck occupying an area of around 45 m

2 (panels inclined at 30°), which is possible on most merchant vessels. The total power generated by the 20 solar panels should be approximately 10 kW. An inverter (DC/AC 3-phase) would be required to supply this solar energy to any consumer whose power consumption is less than 10 kW. The investment corresponding to this proposal is shown in

Table 8. In order to estimate the savings in MDO consumption, as before, it was considered that the solar panels work for 8 hours/day, supplying a load of about 10 kW, for 200 days/year, which (considering a typical consumption of an engine at 180 gr/kWh) corresponds to a saving of 2.88 t/year of MDO, which in economic terms corresponds to 2016 €/year. If the above economic parameters are calculated, the following results are obtained (taking into account 3% of the inversion for maintenance, 25 years of life and a discount rate of 12%):

NPV: 610 €. The investment is profitable, but not a huge saving is going to be made.

IRR: 12.7%. It is positive but it is too like the initial rated return, so it is not a highly profitable project, in economic terms.

DPBP: 21 years.

In view of the results obtained, it can be stated that, from an economic point of view, the installation of solar panels on merchant ships is not profitable, given the small number of panels that can be installed as a result of the limited surface area available and the fact that it takes too many years to recover the cost of the inversion.

Another important problem is that the electricity generated by solar panels is difficult to connect in parallel and synchronized with the auxiliary generators on board, given that the variation of the frequency of them goes, typically, of ±10% of the nominal value and it is not stable, and also the difference of the power supplies of both networks generated that this coupling will be unbalanced.

3.2. Sustainability Analysis

The feasibility analysis carried out above considers technical, legal and economic factors to determine whether the proposal can be realistically implemented. In contrast, a sustainability analysis considers whether a project can maintain its benefits over time without depleting resources or harming the environment [

32,

33].

A sustainability analysis encompasses environmental, social, and economic factors [

34]. Various methods of calculating what is known as the sustainability index (SI) can be found in the literature. One of the most commonly used methods is the simple additive weighting (SAW), according to which the SI can be calculated by Equation (4), where i is the alternative analyzed, c the criteria, w the weight assigned to each criterion j and n the number of criteria. The SI is between 0 (corresponding to the worst sustainability) and 1 (corresponding to the optimal sustainability).

(4)

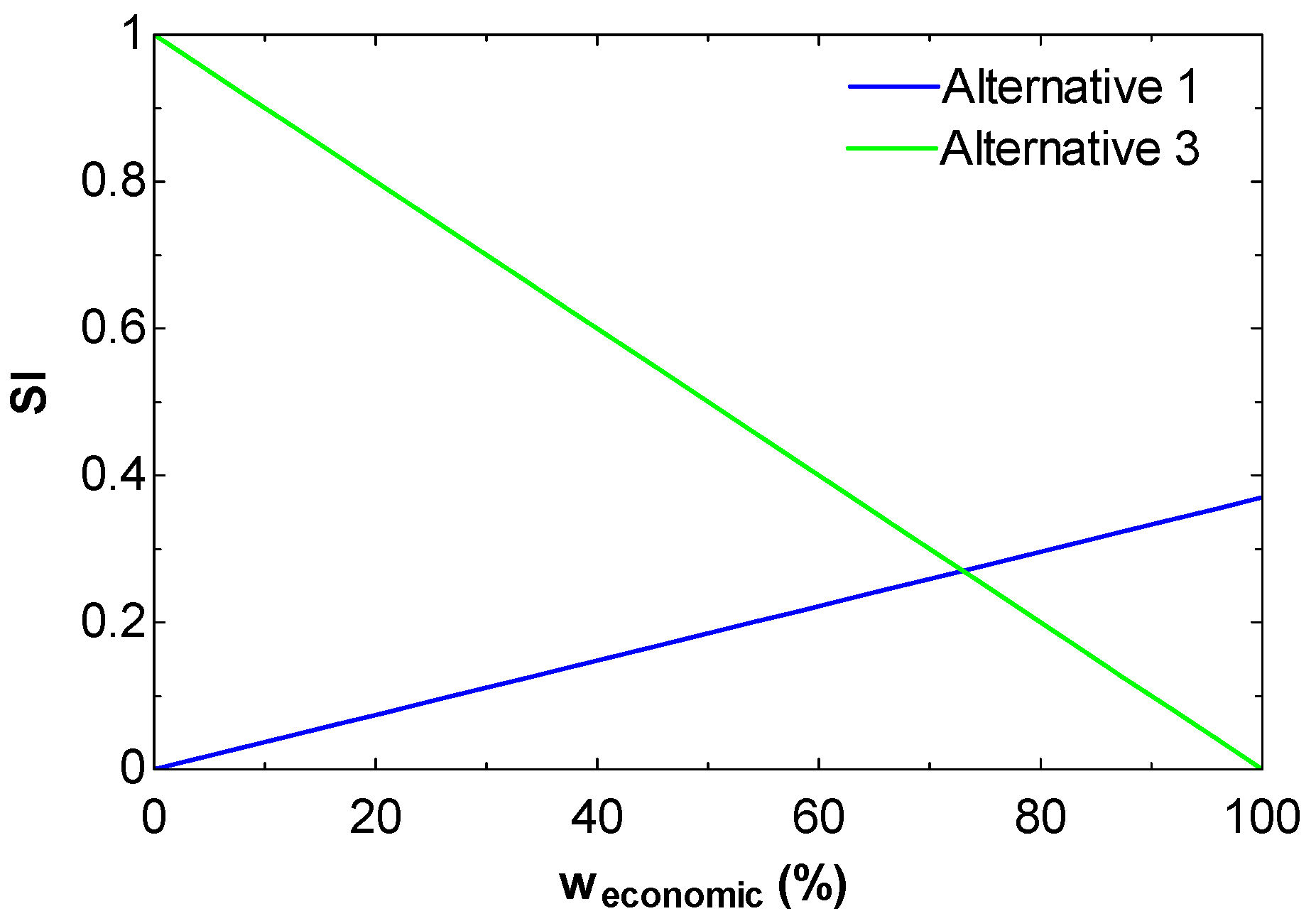

In the present analysis three criteria are considered: economic, social and environment. Regarding the alternatives, since alternative 2 does not meet the SOLAS legal requirements, only alternatives 1 and 3 are compared. The numerical data are shown in

Table 9. Regarding the economic criteria, the costs of alternative 1 and alternative 3 are considered. The cost of alternative 3 refers to the investment cost (1425.72 €), while that of alternative 1 refers to the investment cost plus the MDO consumption cost (432 + 469 = 901 €). These are measurable values obtained in the previous section. In contrast, environmental and social criteria were treated as discrete values, providing a value of 0 to alternative 1 and a value of 1 to alternative 3, given that the latter is more ecological and also more socially appropriate (in terms of community benefits, social equity, cultural impact, and so on).

Once the data for the sustainability analysis are recollected, the next step is to normalize. The normalization process in a sustainability analysis is essential to ensure fair comparisons. In this case, the economic criterion is provided through continuous values in € while the other criteria are provided through discontinuous values as 0 (bad) and 1 (good). The normalization adjusts values to a common scale to consistency and comparability in the analysis. The linear max normalization was used, which follows the following Equations (5) and (6) for beneficial and non beneficial criteria, respectively. In these equations, X is the value and Xj,max the maximum value corresponding to that criterion. In this case, the economic is a non beneficial criterion since it is desirable that the cost is as low as possible, while environmental and social criteria are beneficial since an environmental social solution is desirable.

(5)

(6)

The normalized data are shown in

Table 9. This table includes the normalized values calculated according through Equations (5) and (6), as well as the SI calculated according through Equation (4). In order to calculate the SI, a weight must be given to each alternative. In a sustainability analysis, weights represent the relative importance assigned to different environmental, social, and economic criteria to prioritize key factors in the decision-making. For example,

Table 9 shows the results of the SI corresponding to 50% economic weight (0.5 on a per unit basis), 25% environmental weight (0.25 on a per unit basis) and 25% social weight (0.25 on a per unit basis). These weights corresponds to economic factors with given the half of the possible importance (50%), and the remaining importance has been equally distributed between the other two factors (25% and 25%). Logically, the sum of the assigned weights must be 100, or 1 on a per unit basis. This weighting reflects a decision-making approach where economic sustainability is considered twice as important as environmental and social aspects, influencing how the project’s overall sustainability performance is assessed. It is worth mentioning that choosing weights in a sustainability analysis depends on several factors such as stakeholder priorities, industry standards, regulatory requirements, project goals, and so on. Common methods include expert judgment, stakeholder surveys, historical data analysis and even statistical analyses. For example, a government policy might prioritize environmental factors, while a business-driven project may emphasize profitability. According to this, a sensitivity analysis of the weights has been carried out. The results are shown in

Figure 6, which shows the SI corresponding to alternative 1 and alternative 3 for economic criterion weights ranging from 0 (lowest possible) to 100 (highest possible). As can be seen, from a sustainability point of view, the solution of installing solar panels is recommendable unless the economic issue is of high relevance in the decision-making process.