1. Introduction

Heredity is complex and most diseases such as Alzheimer’s Disease and diabetes are heterogeneous conditions whose phenotypes are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Along with the rise in population, these conditions are increasing and, therefore, putting a growing burden on the healthcare systems (Passeri et al., 2022). Although the research on these complex multifactorial diseases has been going on for several decades, the developed treatments are mainly aimed at alleviating the symptoms rather than curing or preventing the disease (Anton et al., 2024; Elmaleh et al., 2021). For many patients, this means years of trial-and-error treatment and little hope for true disease modification. This therapeutic gap shows an important need for therapeutic strategies which tackle the underlying causes of these conditions.

Target identification is the first and most important step of any systematic drug discovery pipeline, as selecting the right molecular targets significantly increases the likelihood of developing a successful therapeutic agent. from the number of available approaches for identifying drug targets, it has been established that therapies that are backed by solid genetic evidence are much more likely to succeed in clinical trials. Specifically, drugs targeting genes with well-established genetic associations are more likely to succeed in phases II and III of the drug development process, with genetic validation increasing the chances of drug approval by more than two times (King et al., 2019; Minikel et al., 2024).

Thanks to the large sample sizes in population-scale datasets and advances in genome-wide association studies (GWAS), we now have a growing catalog of genetic loci associated with complex diseases. However, not all disease-associated genetic elements are causal. Many simply tag broader regions through linkage disequilibrium, while others may lie in non-coding areas that influence gene expression in subtle, context-dependent ways. Consequently, without clear knowledge of the causal biology, therapeutics may address the symptoms rather than the underlying disease mechanisms. For example, BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease, designed to lower amyloid-beta levels, ultimately failed in late-stage trials due to off-target effects on synaptic proteins that lead to unexpected cognitive decline and severe adverse effects (Bazzari and Bazzari, 2022). This demonstrate the need for approaches that accurately identify causal architecture to inform the development of mechanism-based therapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

To identify causal genetic factors and inform drug development, statistical genetics has evolved beyond GWAS. A suite of post-GWAS methods have been developed to refine the list of loci identified from GWAS to pinpoint those that have putative causal relationship to the disease of interest in a functional context. For example, statistical fine-mapping methods narrow down causal variants within associated loci by disentangling true signals from linkage disequilibrium; colocalization analyses integrate GWAS results with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data to identify shared genetic drivers of both disease and molecular traits; mendelian randomization (MR) leverages genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between modifiable exposures, such as gene expression or protein levels, and disease outcomes (Uffelmann et al., 2021). These approaches collectively provide a statistical framework for prioritizing therapeutic targets with a strong mechanistic basis.

Although we have made strides in identifying genetic markers linked to diseases, traditional genetics approaches have inherent limitations in fully capturing the genetic complexity of complex polygenic diseases. The standard GWAS framework looks at how individual variants relate to disease risk and assumes these variants work independently. While this simplifies computation, it overlooks the non-linear interactions among genetic loci that impact disease susceptibility. Earlier interaction models that try to detect significant interacting variants suffer from limited statistical power and computational inefficiency. The huge number of possible SNP-SNP interactions grows exponentially with the number of variants, making exhaustive genome-wide interaction testing impractical. Furthermore, conventional post-GWAS approaches often analyze omics data as separate layers rather than as interconnected components of a dynamic system. In diseases where genetic risk is influenced by highly regulated molecular pathways, this approach may miss important disease-driving mechanisms. For example, the impact of a variation, on gene expression might vary depending on the situation influenced by factors, like chromatin accessibility, histone modifications or metabolic conditions. This kind of context-dependent regulation can only be readily understood by treating the multi-omics data as interconnected parts of a larger system and studying the causal relationships that shape disease development.

Deep learning approaches provide a new solution to tackle these challenges. They can learn non-linear patterns in genomic data without requiring explicit interaction terms. Similarly, they excel in integrating high-dimensional multi-omics datasets. Unlike statistical frameworks that require predefined hypotheses about how omics layers interact, deep learning models can extract latent representations from each omics modality and identify cross-modal dependencies. Their capacity to integrate spatial and temporal omics data from is especially useful for complex diseases, as many diseases evolve over time and differ across tissue regions, such as neurodegenerative disorders (Dong et al., 2021). One approach involves using autoencoders to condense diverse omics characteristics into embeddings that reflect variations underneath it all. Moreover attention based models and transformer designs take this a step further by assigning varying weights to features and effectively highlighting the most significant molecular cues, for a specific disease. By leveraging these approaches, deep learning makes it possible to construct comprehensive models of disease mechanisms that incorporate genetic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic interactions in a unified structure.

While deep learning for genetics studies has gradually been recognized as a useful tool, its applications in genetics research are still at an infant stage as compared to the traditional statistical methods. An important obstacle faced is the problem of overfitting where the model ends up capturing patterns to the training data instead of more general relationships relevant across different datasets. Another limitation is its lack of statistical rigor and interpretability. Traditional statistical genetics methods are built on well-established principles of hypothesis testing and causal inference. They provide quantifiable measures of uncertainty, such as p-values and confidence intervals, which are essential for evaluating the robustness of findings. In contrast, deep learning models, in their naïve form, often function as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand the biological basis of their outputs. This lack of transparency hampers their effectiveness in validating causal relationships between genetic variants and disease phenotypes.

Combining the scalability of deep learning with the rigor of statistical genetics presents a promising path forward for uncovering causal mechanisms in complex diseases. Deep learning-based causal representation learning can model complex genetic interactions and integrate multi-omics data in a biologically meaningful way. These advancements enable comprehensive genome-wide discovery of putative causal genetic variants that drive disease processes. Integrating statistical principles of causal inference into deep learning-driven causal discovery can further ensure that these computational discoveries translate into robust biological insights. This integration not only mitigates overfitting of the data but also refines and enhances the statistical confidence of the identified causal relationships.

In this review, we explore the evolving landscape of computational approaches to causal inference in complex disease. We begin by reviewing traditional statistical approaches, including GWAS and post-GWAS analyses, highlighting their contributions and limitations in target discovery. We then examine how deep learning is reshaping the field, with a focus on epistasis modeling and multi-omics integration. We critically assess two main limitations of these deep learning methodologies: overfitting and interpretability. Finally, we outline future research directions focused on developing integrative frameworks that merge deep learning’s ability to discover novel genetic drivers with statistical methodologies that ensure robust causal interpretation. Our goal is to guide researchers in field to navigate next-generation computational tools for uncovering the molecular basis of complex polygenic diseases.

2. Established Statistical Genetics Approaches

GWAS leverages high-throughput genotyping technologies and statistical models to analyze millions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome, aiming to uncover genotype-phenotype associations. The predominant statistical frameworks in GWAS include fixed-effect and linear mixed-effect models, each tailored to specific study designs and population structures. The fixed-effect model assumes a consistent effect of a genetic variant across all individuals in the study and is particularly suited for homogeneous populations with minimal population structure (Tam et al., 2019). It is computationally efficient and straightforward, making it ideal for initial scans of well-matched cohorts. However, they do not inherently address confounding factors such as relatedness or population structure. To mitigate these issues, researchers commonly calculate identity-by-descent metrics to exclude closely related individuals and adjust for population stratification by including principal components derived from genetic data as covariates in association analyses (Nielsen et al., 2011). Despite these adjustments, fixed-effect models may still fail to fully capture complex confounding effects, potentially leading to residual biases in highly diverse populations. The linear mixed-effect model, on the other hand, incorporates a random effect term to account for confounding effects, including subtle population substructure and genetic relatedness (Uffelmann et al., 2021). By modeling these confounding factors, it reduces the risk of false positives, especially in diverse populations. While computationally more demanding than fixed-effect models, it is particularly advantageous in large-scale studies or meta-analyses involving heterogeneous datasets.

Large-scale biobanks have been instrumental in advancing GWAS by providing extensive genetic and phenotypic data. The UK Biobank, with genotypic and health data from over 500,000 participants, has enabled the discovery of genetic associations across a wide range of diseases. Biobank Japan has contributed ancestry-specific insights, while the All of Us Research Program emphasizes diversity and health equity. Specialized biobanks, such as the International Glaucoma Genetics Consortium (IGGC), have focused specifically on neurodegenerative diseases like glaucoma, facilitating meta-analyses and replication studies. These resources not only improve the statistical power of GWAS but also allow researchers to examine population-specific genetic architectures.

While GWAS have provided unprecedented insights into the genetic architecture of complex diseases, translating these associations into actionable drug targets requires post-GWAS methodologies to identify the biological mechanisms that cause the disease of interest (Mortezaei & Tavallaei, 2021). The challenge lies in resolving the causal variants and genes from the statistical associations observed in GWAS, as most significant loci encompass multiple variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD) and often reside in non-coding regions. To address these challenges, a plethora of post-GWAS methods have been developed, which leverage fine-mapping and omics data to prioritize causal variants and genes (Sigala et al., 2024).

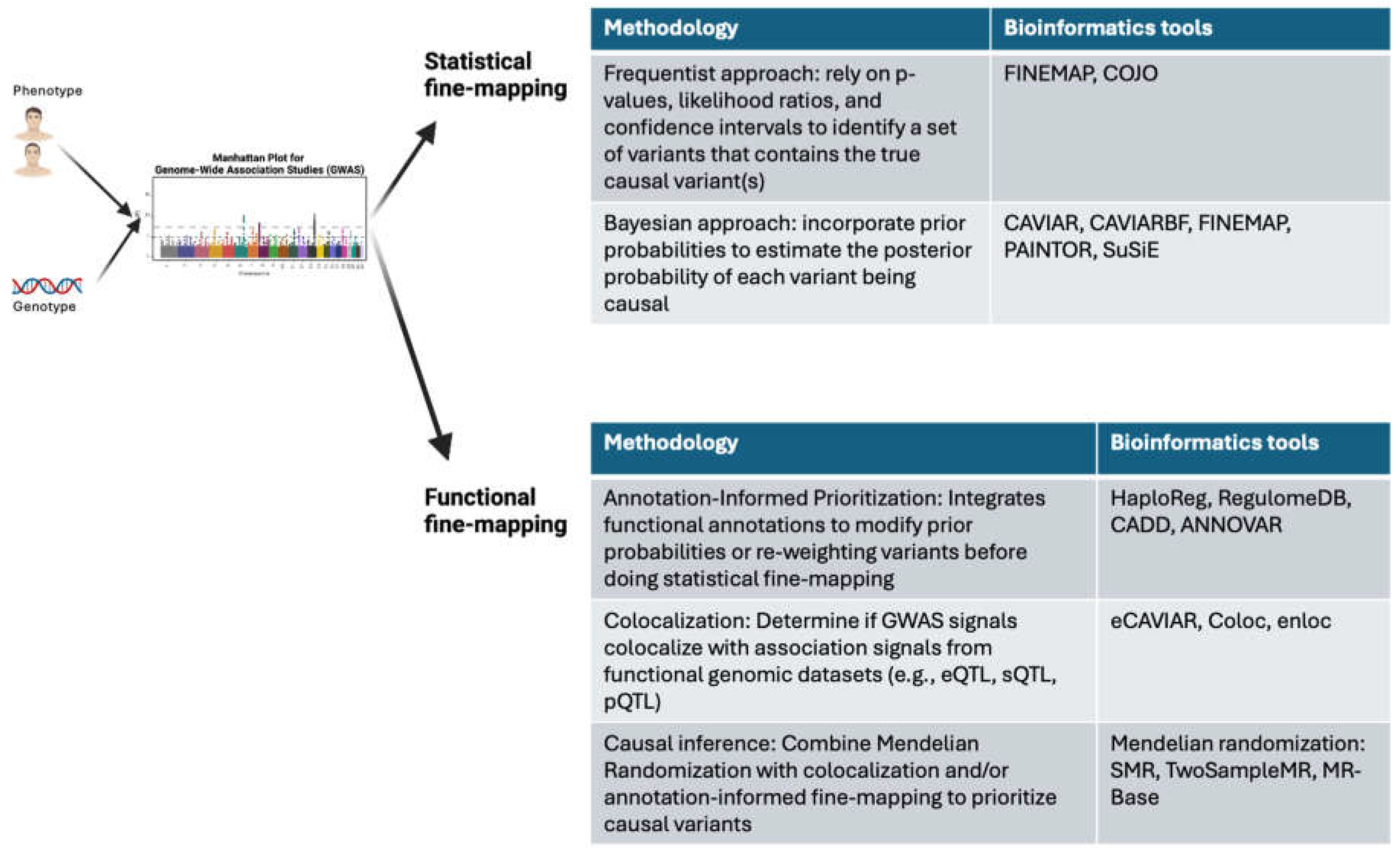

Post-GWAS analyses can be broadly classified into statistical fine-mapping and functional fine-mapping (

Figure 1). Statistical fine-mapping leverages Bayesian and frequentist methodologies to quantify the probability that a given SNP is causal. The core challenge in fine-mapping arises from the high correlation among SNPs due to LD, which creates ambiguity in pinpointing the precise variant driving the association. Frequentist-based approaches, including conditional and joint analysis (Yang et al., 2013), employ stepwise regression models that iteratively adjust for the effects of lead SNPs to identify independent association signals. Bayesian approaches, such as CAVIAR (Hormozdiari et al., 2014) and FINEMAP (Benner et al., 2016), estimate posterior probabilities of causality by modeling the joint distribution of effect sizes across all SNPs in a locus, incorporating priors that account for the expected number of causal variants per region. These methods generate credible sets, which represent the minimal subset of SNPs that collectively capture a high probability of containing the true causal variant. The effectiveness of these methods is contingent upon high-quality GWAS summary statistics and accurate LD reference panels, as misestimation of LD structure can lead to inflated credible sets or erroneous prioritization of variants.

Functional fine-mapping integrates functional data to prioritize variants based on their regulatory potential and link them to the biological pathways and genes they influence. One of the most widely utilized functional annotations in fine-mapping is expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping, which links genetic variants to variation in gene expression across tissues. Large-scale eQTL resources such as GTEx and eQTLGen provide valuable datasets that enable the identification of SNPs that act as transcriptional regulators. Beyond gene expression, splicing quantitative trait locus (sQTL) mapping provides further granularity in fine-mapping by identifying variants that influence alternative splicing rather than overall transcript abundance. Many non-coding GWAS SNPs exert their effects through RNA splicing, leading to altered isoform usage that may be more relevant to disease phenotypes than changes in total gene expression. Fine-mapping efforts are further strengthened by chromatin accessibility and histone modification data, which provide insights into the regulatory landscape of the genome. Variants that reside within open chromatin regions, as detected by ATAC-seq and DNase-seq, are more likely to be functionally active, particularly if they coincide with histone modifications associated with enhancer or promoter activity, such as H3K27ac and H3K4me3. Integrative statistical frameworks, including GARFIELD (Iotchkova et al., 2019) and GenoWAP (Liu et al., 2015), assign functional scores to SNPs based on their enrichment in these regulatory features, improving fine-mapping resolution by prioritizing variants that are more likely to exert regulatory effects. Moreover, transcription factor binding site (TFBS) mapping provides a direct mechanism by which SNPs influence gene regulation. SNPs that disrupt or create TF binding motifs, as inferred from position weight matrix (PWM) analysis and validated by ChIP-seq data, can modulate transcriptional activity in a context-specific manner. Variants that alter TFBSs often serve as allele-specific regulators, leading to differential expression patterns that contribute to disease risk. Another crucial aspect of functional annotation involves understanding long-range regulatory interactions, particularly in cases where the nearest gene to a GWAS variant is not the true target of regulation. Hi-C, promoter capture Hi-C (PCHi-C), and ChIA-PET datasets provide genome-wide maps of chromatin interactions, allowing the identification of distal enhancer-promoter contacts that mediate gene regulation. For instance, SNPs located in non-coding regions may function by altering enhancer activity, which in turn regulates gene expression at a distant locus. This has been exemplified in the case of the FTO locus, where obesity-associated variants do not affect FTO itself but instead regulate IRX3 and IRX5 expression through enhancer-promoter looping. Activity-by-Contact (ABC) modeling and JEME leverage chromatin conformation data alongside histone marks and eQTLs to map GWAS variants to their likely target genes, thereby enhancing the interpretability of fine-mapped SNPs.

Colocalization analysis provides a critical statistical framework for disentangling the causal relationships between genetic variation and molecular traits across all types of functional and omics data. Unlike approaches that merely assess correlations between GWAS and functional signals, colocalization explicitly models the probability that two signals share a common causal variant, thereby reducing false positives due to LD. This framework is particularly relevant for integrating GWAS loci with molecular QTL data. Statistical methods such as coloc (Giambartolomei et al., 2014), eCAVIAR (Hormozdiari et al., 2016), and enloc (Wen et al., 2017) leverage GWAS summary statistics and LD information to estimate the posterior probability that a given SNP is responsible for both a disease association and a molecular trait. coloc, a widely used Bayesian framework, assumes a single causal variant per region and evaluates posterior probabilities across five competing hypotheses to determine whether a shared causal variant exists. eCAVIAR, in contrast, extends this approach by modeling multiple causal variants per locus through a multivariate Gaussian framework, offering greater flexibility in loci with complex LD structures. enloc, another extension of colocalization, accounts for incomplete LD information and sparse eQTL effects, making it particularly useful for fine-mapping functional regulatory elements.

The application of colocalization to various functional datasets has yielded important insights into disease mechanisms across a range of tissues and regulatory contexts. For example, the integration of GWAS loci for primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and intraocular pressure (IOP) with cis-eQTLs and sQTLs from GTEx tissues and retinal-specific datasets has demonstrated that colocalization is a powerful tool for refining causal gene identification (Hamel et al. 2024). A recent study found that 58% of tested loci colocalized with molecular QTLs, leading to the identification of genes such as TMCO1, GAS7, and LMX1B as glaucoma risk genes. Mechanistically, TMCO1-associated variants were shown to regulate alternative splicing in fibroblast tissues, with reduced TMCO1 expression correlating with elevated IOP and increased disease risk. Beyond gene prioritization, colocalization analysis has also revealed pathway-level regulatory mechanisms; for example, IOP-associated loci implicate genes like ANGPT1 and ANGPT2, which are involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and vascular biology, whereas loci associated with normal-tension glaucoma highlight alternative mechanisms, such as retinal glial cell involvement, reinforcing the tissue- and subtype-specific nature of genetic regulation. However, the accuracy of colocalization analysis depends on the resolution and relevance of the molecular QTL data. Functional annotation of non-coding regions remains incomplete, particularly in tissue types relevant to neurodegenerative diseases, limiting the ability to fully map the regulatory landscape that drives disease risk.

To further strengthen causal inference, Mendelian randomization (MR) builds on colocalization by leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables to test causality between gene expression or protein levels and disease risk. MR uses these genetic variants, which are associated with exposure (e.g., gene expression), to infer whether changes in exposure levels causally affect the outcome (e.g., disease risk). By relying on the principle of random assignment inherent in the segregation of alleles, MR mimics randomized controlled trials, minimizing confounding and reverse causality. Advanced MR methods, such as MR-Egger regression and weighted median MR, provide robust frameworks for addressing horizontal pleiotropy, a major challenge in traditional MR analyses. Horizontal pleiotropy occurs when genetic variants influence the outcome through pathways independent of the exposure, violating the assumption that instrumental variables affect the outcome solely through the exposure. MR-Egger regression addresses this issue by allowing for a non-zero intercept in the regression of SNP-outcome effects against SNP-exposure effects. The intercept estimates the average pleiotropic effect across all instruments, thereby detecting and correcting for pleiotropy. However, MR-Egger requires a large number of genetic instruments to achieve sufficient statistical power and is particularly susceptible to weak instrument bias when the genetic variants have small effects on the exposure. Weighted median MR offers an alternative approach that is robust to pleiotropy by calculating the median of the weighted instrumental variable estimates. This method assumes that at least 50% of the weight in the analysis is derived from valid instruments—those not subject to pleiotropy. Compared to MR-Egger, weighted median MR is less sensitive to outliers and weak instruments, making it especially useful in scenarios with limited instruments or variability in their effects. Both methods complement each other, with MR-Egger providing a pleiotropy-sensitive framework and weighted median MR offering a robust option when pleiotropy-free instruments predominate.

The power of MR extends beyond eQTLs and sQTLs to a broader array of functional QTLs, including chromatin accessibility QTLs (caQTLs), histone modification QTLs (hQTLs), and transcription factor binding QTLs (tfQTLs). These QTL types capture diverse aspects of genome regulation, allowing MR to interrogate whether chromatin state alterations, histone modifications, or TF binding changes causally mediate disease risk. For instance, MR can be used to test whether increased enhancer activity in a disease-associated region causally upregulates a downstream gene, ultimately affecting disease susceptibility. When integrated with Hi-C and promoter capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) data, MR can further dissect whether long-range enhancer-promoter interactions mediate these effects, refining target gene identification.

Despite its strengths, MR remains dependent on several key assumptions, including the correct specification of instrumental variables, absence of confounders, and exclusion of reverse causality. Violations of these assumptions can lead to misleading causal inferences, particularly in complex traits where multiple regulatory mechanisms interact. Additionally, the quality of the underlying GWAS and functional QTL datasets critically influences MR reliability. If the instrumental variables are weakly associated with the exposure or if exposure-outcome relationships are confounded by hidden genetic correlations, MR estimates may be biased or lack statistical power.

These well-established statistical genetics approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in uncovering genetic mechanisms underlying complex diseases. For example, A study integrating brain-derived eQTLs with MR and colocalization successfully identified five genes—ACE, GPNMB, KCNQ5, RERE, and SUOX—as promising therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Baird et al., 2021). Notably, GPNMB, a gene encoding the transmembrane protein glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B, was further studied experimentally to elucidate its molecular role in PD and prioritized as a therapeutic target for PD (Diaz-Ortiz et al. 2022).

3. Why are Traditional Statistical Genetics Methods Alone Insufficient?

Despite the discovery of thousands of disease-associated loci through GWAS, these variants explain only a fraction of genetic heritability for complex traits (Manolio et al., 2009, Tam et al. 2019). For instance, in Alzheimer’s disease, SNP-based heritability estimates range from 38% to 66%, depending on the age of cases and controls, yet only about 13% of this heritability can be attributed to known genetic loci (Baker et al., 2022). Part of this missing heritability is contributed by genetic epistasis -- the interaction between genetic variants. Current GWAS is dominated by linear additive models, which fail to capture complex, non-linear, and epistatic relationships in disease etiology. Variant interactions remain largely undetected by traditional GWAS due to limitations in statistical power and computational feasibility. However, evidence suggests that these interactions significantly enhance risk prediction and provide deeper mechanistic insights into disease pathology. For instance, large-scale interaction studies further highlight this impact. A study of 46,000 breast cancer cases and 42,000 controls found that SNP-SNP interactions accounted for additional risk variance undetected in single-locus tests (Milne et al., 2014). In primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), incorporating SNP interactions increased the explained heritability from 2.1% to 3.5%, demonstrating the importance of modeling epistasis (Verma et al., 2016). a study on Parkinson’s disease (PD) found that risk variants in the HLA region do not act independently; rather, their effects are modified by the presence of other SNPs. Conditional analyses revealed that multiple independent SNPs (rs3129882, rs2844505, rs9268515) interact to influence disease susceptibility, with certain haplotypes significantly increasing risk compared to individual variants alone. This suggests that GWAS focusing only on single-SNP associations may misidentify true causal loci by failing to account for epistatic effects (Hill-Burns et al., 2011).

Many approaches attempt to address these limitations by analyzing epistasis at the gene or protein level, but they often rely on marginal SNP associations and miss true SNP-SNP interactions (Hoffmann et al., 2024). Gene-level aggregation assumes that interactions manifest at the functional protein level, which holds for some pathways but not universally. For example, SNPs in non-coding regions, which regulate expression via transcriptional enhancers and chromatin accessibility, exhibit strong combinatorial effects that cannot be inferred from protein-protein interaction networks alone (Hoffmann et al., 2024). Ignoring SNP-level epistasis risks missing key mechanistic insights, particularly in neurodegenerative diseases where transcriptional regulation plays a major role.

Although various statistical- and data-mining-based methods to detect epistasis from population genetics studies have been developed over the past two decades, these approaches have increasingly struggled to keep pace with the complexity of modern datasets. Early regression-based models, while foundational, became computationally impractical due to the combinatorial explosion of SNP interactions. Methods like the Kirkwood Superposition Approximation (KSA) improved efficiency but remained limited to pairwise interactions and suffered from false positives in low minor allele frequency (MAF) scenarios. Bayesian approaches, such as Bayesian Epistasis Association Mapping (BEAM), incorporated prior knowledge and probabilistic frameworks but were computationally intensive and reliant on accurate priors. Non-parametric strategies like Multifactor Dimensionality Reduction (MDR) captured higher-order interactions but were computationally prohibitive and sensitive to imbalanced datasets. Kernel-based models, including Logistic Kernel Machines (LKM) and weighted Principal Component Analysis (wPCA), provided greater flexibility in modeling SNP interactions but depended on predefined groupings and kernel functions, limiting their adaptability. Despite these advances, traditional methods remain constrained by their inability to efficiently model higher-order epistasis, susceptibility to sparse data issues, and reliance on exhaustive searches or rigid statistical assumptions.

Another critical limitation of traditional statistical GWAS and post-GWAS approaches is their inability to effectively integrate multi-omics data to prioritize causal genetic elements for complex diseases. Multi-omics integration is critical in distinguishing true causal effects from statistical correlations by integrating functional annotations and regulatory elements. However, while statistical methods can isolate associations between specific variants and molecular phenotypes, they struggle to model the complex regulatory relationships spanning multiple omics layers. This limitation is particularly relevant in neurodegenerative diseases, where genetic risk variants often reside in non-coding regulatory regions and exert their effects through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), for example, GWAS-identified risk loci such as APOE, BIN1, and CLU affect chromatin accessibility and transcription factor binding in microglia, ultimately influencing tau aggregation and amyloid-beta clearance (Nott et al., 2019). However, a standard eQTL-based approach may identify a SNP influencing BIN1 expression but fail to capture downstream proteomic interactions, such as tau phosphorylation, that ultimately drive disease progression. Similarly, in Parkinson’s disease (PD), risk variants in SNCA (α-synuclein) and LRRK2 contribute to disease risk, but their pathogenic impact is mediated by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, which influence α-synuclein aggregation and mitochondrial dysfunction (Schmit et al., 2013). An optimal framework for identifying true molecular drivers of complex diseases must integrate genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data, allowing for the detection of both individual and interaction genetic elements that causally influence disease susceptibility.

4. Emerging Deep Learning Approaches for Causal Learning with Population Genetic and Multi-Omics Data

Compared to standard linear-model-based GWAS that struggle to detect high-order SNP-SNP interactions, deep learning methods are being developed as powerful tools for genome-wide discoveries. Their ability to scale to high-dimensional genomic data and perform effective feature extraction enables the identification of complex genetic interactions that contribute to disease etiology. The use of transformer-based structures, which have demonstrated their ability to identify SNP-SNP relationships beyond traditional second-order versions, is one of the most promising advancements in epistasis diagnosis. Unlike traditional comprehensive research techniques that suffer from sequential explosion, transformers use attention mechanisms to selectively detect high-order relationships without systematically evaluating all possible SNP combinations. For example, Graça et al. use attention scores and gradient-based relevance measures to maintain explainability while allowing efficient scalability to large GWAS datasets (Graça et al., 2024). Interestingly, they show that their models can identify interactions up to the ninth order, an achievement that was virtually impossible with conventional statistical techniques.

Other promising approaches that integrate neural networks with classical quantitative or ensemble learning methods have also been developed. A deep mixed model framework (Wang et al., 2019) combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for confounding factor correction with long short-term memory networks for effect size estimation. This model improves epistasis detection by simultaneously correcting for population structure while capturing high-order SNP interactions. As another example, in order to enhance interpretability and noise robustness, a method was developed to incorporate deep neural networks with random forests, where the feature representations learned by a deep network serve as input for a tree-based classifier to (Uppu & Krishna, 2018). Beyond neural network-based architectures, network medicine-based approaches are reshaping epistasis detection by integrating biological priors into machine learning models. Given that gene-gene interactions are often influenced by shared pathways or protein-protein interactions, network-based approaches utilize prior biological knowledge to prioritize SNP interactions. A notable example is the NeEDL framework, which leverages SNP-SNP interaction networks to detect high-order interactions and employs quantum computing techniques to enhance computational efficiency (Hoffmann et al., 2024). This method outperforms standard machine learning models by ensuring that the identified SNP interactions are not statistical artifacts but instead have biological plausibility. Another important direction involves feature selection and interpretability-driven methods. Entanglement mapping refines SNP-SNP interaction detection by iteratively perturbing SNP subsets and measuring their impact on a random forest’s variable importance scores (Mahmoodi et al., 2022). Instead of simply predicting disease status, this approach avoids the pitfalls of black-box deep learning models by explicitly identifying which SNPs contribute to interactions. Similarly, sparsity-driven approaches, such as those using mixed-effect deep learning models (Yun et al., 2024), incorporate priors that enforce structured sparsity to improve model interpretability and reduce overfitting. Overall, these methods demonstrate the growing potential of deep learning to reveal epistatic interactions that drive complex diseases, marking an exciting shift in computational genomics. More research efforts are needed to refine these methodologies to make them more adapt to large datasets and more biologically interpretable.

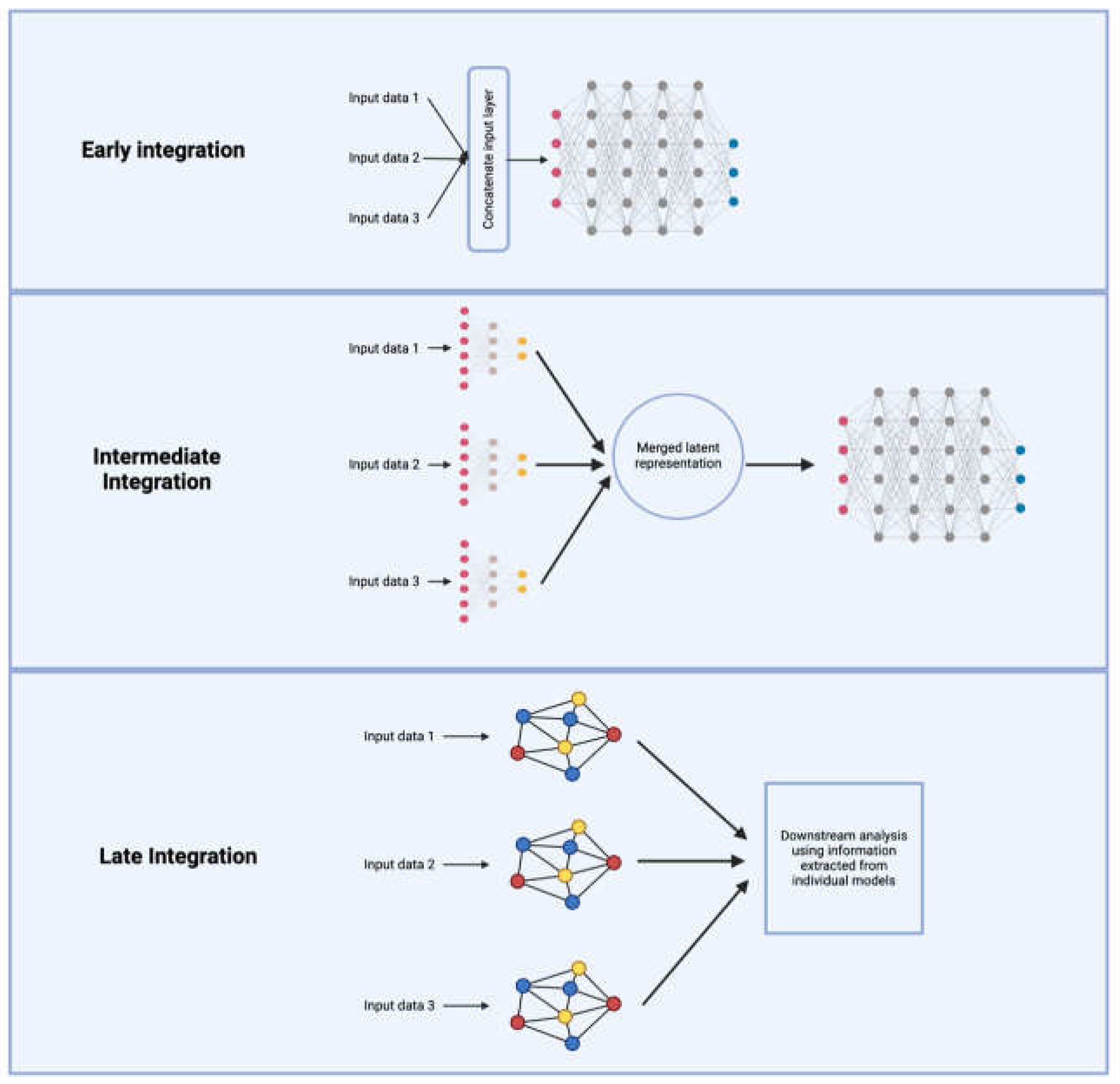

Deep learning also offers a unique avenue for multi-omics integration that moves beyond the traditional post-GWAS methods that use each omics layer separately for functional annotation of GWAS results. It enables the discovery of complex interdependencies between genetic, transcriptomic, epigenetic, and proteomic features that are often lost in sequential analyses (Li et al., 2018). Beyond capturing cross-omics relationships, deep learning is particularly well-suited for modeling the spatiotemporal dynamics of neurodegenerative diseases, which progress over time and exhibit region-specific vulnerability in the brain and retina. However, multi-omics integration presents significant computational challenges, including differences in feature distributions, modality-specific noise, and the risk of overfitting. To address these challenges, deep learning-based integration strategies fall into three major categories: early, intermediate, and late integration. Each approach varies in how and when the information from different omics layers is combined, affecting scalability and interpretability.

Early integration concatenates features from all omics layers into a single high-dimensional representation before training a model. This approach is relatively computationally straightforward and is applicable to the newer spatiotemporal omics datasets from neurodegenerative research, where paired multi-omics data from the same biological sample such as retinal cells are increasingly available. However, caution should be used to address the severe dimensionality and sparsity challenges, particularly when integrating omics modalities with vastly different feature distributions (Valous et al., 2024). Aggressive dimensionality reduction techniques are often necessary to mitigate these issues, but excessive feature compression can lead to the loss of biologically significant signals, thereby limiting the interpretability and predictive power of downstream models (Hauptmann & Kramer, 2023).

Intermediate integration offers a more refined approach by learning latent representations for each omics layer independently before combining them in a shared space for downstream tasks. This strategy preserves modality-specific signals while enabling meaningful fusion across data types. Techniques like variational autoencoders (VAEs) have gained prominence in this domain by effectively filtering out noise while preserving biologically relevant features. DeepProg exemplifies this approach, using autoencoders to transform omics data into lower-dimensional embeddings before merging them for prognosis prediction (Poirion et al., 2021). Instead of feeding raw multi-omics data directly into a unified model, DeepProg applies unsupervised learning at the feature extraction stage, selecting survival-associated latent variables from each omics-specific autoencoder. This method enhances biological interpretability while minimizing the risk of overfitting. Other frameworks, such as OmiEmbed, employ similar strategies, mapping high-dimensional omics data into structured latent spaces optimized for predictive tasks (Zhang et al., 2021). Deep generative models, particularly multi-modal VAEs, have further refined intermediate integration by learning joint probabilistic embeddings that preserve biological structure. For example, MultiVI extends VAEs by explicitly modeling modality-specific noise and batch effects, making them particularly effective for single-cell multi-omics data integration (Brombacher et al., 2022). While this modular framework allows for the flexible incorporation of new omics layers while maintaining biological interpretability, careful selection of latent variables is needed to avoid overcompression of important biological signals.

Late integration, by contrast, trains separate models on each omics layer before combining their outputs into a final prediction. This approach is especially advantageous in scenarios where different omics modalities exhibit distinct data structures and levels of complexity (Valous et al., 2024). By processing each modality independently, late integration allows for specialized modeling tailored to the statistical properties of each omics type, preventing information loss due to premature fusion. Graph-based methods and ensemble learning techniques frequently facilitate this process by leveraging the strengths of each modality-specific model while capturing cross-modal interactions at a later stage. Deep ensemble learning frameworks mitigates biases associated with any single omics modality by averaging or voting across predictions from distinct models. In Super.FELT, modality-specific encoders first extract feature representations separately from transcriptomic, genomic, and epigenomic data (Chereda et al., 2021). These representations are subsequently fed into independent classifiers, and their outputs are aggregated through an attention-weighted fusion mechanism to emphasize the most predictive modalities. This methodology effectively balances model flexibility and integration scalability, making it well-suited for complex multi-omics tasks.

Graph-based methods, such as graph neural networks (GNNs), provide another powerful late integration strategy by structuring omics data into networks where biological entities (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) serve as nodes and relationships (e.g., co-expression, physical interactions, metabolic pathways) are represented as edges (Wu & Xie, 2024). Unlike conventional machine learning models, which treat omics features as independent variables, GNNs leverage these biological relationships to improve prediction accuracy and interpretability. For instance, MoGCN (Multi-Omics Graph Convolutional Network) refines cancer subtype classification by incorporating pathway-based priors (Li et al., 2022). MoGCN constructs a heterogeneous graph where nodes correspond to genes and pathways, and edges capture molecular interactions inferred from transcriptomic and epigenomic data. Through iterative message passing, MoGCN learns contextualized embeddings that integrate cross-omics regulatory patterns, improving its ability to distinguish cancer subtypes with high biological fidelity. Similarly, Cell-GNN applies a graph-based late-integration approach to infer regulatory interactions in single-cell multi-omics datasets (Cao & Gao, 2022). Unlike MoGCN, which focuses on bulk-level omics integration, Cell-GNN models cell-type-specific interactions by constructing gene-gene interaction graphs at the single-cell level. This method captures cell-state transitions by linking transcriptional activity to chromatin accessibility, making it particularly effective for reconstructing lineage differentiation and disease progression pathways.

While there is currently no single deep learning framework capable of simultaneously capturing high-order epistatic interactions, integrating multi-omics data, and prioritizing both individual causal SNPs and their interactions within a fully resolved causal map, deep learning presents a uniquely powerful platform for achieving this goal. Bringing SNP interaction modeling and multi-omics causal inference under a single deep learning framework would transform our ability to map disease mechanisms. Instead of treating genetic associations as static risk factors, we could reconstruct dynamic, multi-layered networks that show how genetic variants interact across different biological scales. This shift would move us closer to therapeutic strategies that address root causes rather than symptoms, as well as offer strong biology understanding for the development of state-of-art therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases such as gene therapies.

5. Challenges of Deep Learning Models in Genomics Research

Current deep learning models demonstrate excellent capabilities for recognizing complex nonlinear hierarchical patterns in multi-omics and genetic datasets but remain in their initial development phase while facing multiple challenges. The main ones include overfitting and the lack of interpretability or statistical rigor. The learning patterns that a deep learning model detects from training data can sometimes produce noise instead of generalizable relationships which leads to poor performance when testing new data. Multi-omics data increases this problem by introducing various feature spaces that bring different types of noise and batch effects. When combining transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics data for analysis they produce modality-specific noise that deep learning models may confuse with relevant patterns. The overlapping molecular pathways between neurodegenerative diseases create an additional problem since they make it hard to detect disease-specific signals. The generation of false associations together with missed subtle biologically relevant patterns through overfitting, resulting in unreliable findings that slow down our understanding of disease mechanisms.

To prevent overfitting, multiple measures should be implemented. The training process is controlled by dropout and L2 regularization which either deactivate neurons randomly or impose penalties for large parameters to enhance model generalizability. These techniques could unintentionally diminish important biological signals in samples with diverse characteristics. Autoencoders with denoising capabilities effectively minimize noise in multi-omics data through feature reconstruction but their performance strongly depends on proper noise injection calibration. Modular architectures like CustOmics divide omics-specific learning from multi-omics integration to stop the spread of noise across different omics data layers. These effective methods need substantial computational power and precise tuning procedures to process the complex scale of multi-omics data. Model architecture that includes biological priors demonstrates effectiveness in controlling overfitting. Graph neural networks and factorization-based autoencoders use gene regulatory networks and protein-protein interaction maps as prior knowledge to direct model learning. Model constraints steer learning toward biological relationships because they restrict models from creating spurious associations. Prior knowledge accuracy and completeness serves as a limitation for these approaches since they depend on it for their operation especially in fields with limited research data. Adversarial regularization techniques that penalize population-specific signals to enhance generalizability across diverse cohorts create additional training complexity and potential instability because of competing loss objectives. The various methods show that deep learning models encounter persistent overfitting issues in genomics research which needs continuous innovation to develop better generalizable techniques.

The main disadvantage of deep learning methods in this field is the absence of a standardized statistical framework. The field of drug target discovery places greater importance on both interpretable deep learning models and statistically sound results rather than just predictive model performance. Traditional statistical analysis establishes robust hypothesis testing frameworks which generate p-values and confidence intervals to measure statistical significance and uncertainty. The optimization of deep learning models for predictive accuracy produces results without inherent statistical metrics and standardization which creates difficulties for studying different studies. Model architecture differences combined with variations in hyperparameter tuning and data preprocessing pipelines lead to inconsistent results that fail to reproduce. As noted by Kang et al. (2021), deep learning model configuration variations in multiple studies about multi-omics data integration produce results that are challenging to reproduce and interpret (Kang et al., 2021).

The ability of deep learning methods in genomics research to perform causal learning benefits from their data-driven approach and their capability to model non-linear high-dimensional relationships in genomics. Traditional causal inference methods will continue to serve a crucial function for conducting strict hypothesis tests and establishing mechanistic causality. Causal discovery in genomics will probably combine causal inference frameworks with deep learning algorithms in future developments. These hybrid methods attempt to merge the modeling power of deep learning methods with the interpretability of traditional statistical techniques. The combination of paradigms enables researchers to tackle complex genomic data while moving toward understanding causal molecular mechanisms in complex diseases.

6. Future Directions: Integrating Deep Learning with Statistical Principles

Advancing causal discovery in neurodegenerative diseases requires a framework that unites the complementary strengths of deep learning and traditional statistical genetics. A crucial step forward lies in leveraging deep learning models to integrate multi-omics data—including genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic layers—to capture nonlinear interactions both within and across these molecular domains (Dibaeinia et al., 2025) This is particularly crucial in neurodegenerative diseases, where regulatory elements and non-coding variants exert their effects through intricate networks rather than isolated genetic loci.

Unsupervised causal discovery methods, also known as latent causal representation learning, is particularly advantageous to be applied to these integrated datasets to identify hidden causal mechanisms underlying disease etiology (Yang et al., 2022). Methods such as CausalVAE and deep structural causal models have demonstrated their ability to extract meaningful latent representations that capture high-order interactions among molecular elements (Lagemann et al., 2023). Beyond these approaches, multi-domain causal representation learning presents a novel avenue for integrating heterogeneous datasets that may share latent causal factors. Recent work has provided theoretical guarantees for identifying shared causal graphs across unpaired datasets, addressing a critical limitation in traditional causal inference techniques (Sturma et al., 2023). This capability is particularly relevant for neurodegenerative research, where patient-derived multi-omics data are often collected from different experimental modalities, requiring robust methods to reconstruct the underlying causal structures.

While deep learning-based causal discovery is instrumental for hypothesis generation, rigorous validation is essential to establish causal mechanisms with confidence. Deep Mendelian Randomization (DeepMR) extends conventional MR by incorporating deep learning-derived SNP-disease associations into causal effect estimation, thereby improving the robustness of causal inference (Zhao et al., 2022) . Additionally, frameworks that integrate counterfactual reasoning and interventional analysis within deep learning pipelines will be crucial for distinguishing genuine causal effects from statistical artifacts (Brand et al., 2023). Recent advances in interpretable AI highlight the potential of structured causal disentanglement, allowing researchers to map learned representations back to biologically meaningful entities, ensuring the interpretability of deep learning-derived causal representations (Dibaeinia et al., 2025).

The future of neurodegenerative disease research lies in the development of integrative frameworks that synergize deep learning’s ability to model complex, high-dimensional data with the statistical rigor of causal inference. Such a framework will not only deepen our understanding of disease etiology but also strengthen the foundation for experimental validation. As methodological advances continue to bridge the gap between data-driven discovery and causal interpretation, the field will be better positioned to identify disease-driving mechanisms and ultimately develop therapies that alter—rather than merely alleviate—the course of these devastating conditions.

Figure 2.

Schematics of the three deep-learning multi-omics integration strategies.

Figure 2.

Schematics of the three deep-learning multi-omics integration strategies.

References

- Anton, N., Geamănu, A., Iancu, R., Pîrvulescu, R.A., Popa-Cherecheanu, A., Barac, R.I., Bandol, G., Bogdănici, C.M., 2024. A Mini-Review on Gene Therapy in Glaucoma and Future Directions. IJMS 25, 11019. [CrossRef]

- Ashuach, T., Gabitto, M.I., Koodli, R.V., Saldi, G.-A., Jordan, M.I., Yosef, N., 2023. MultiVI: deep generative model for the integration of multimodal data. Nat Methods 20, 1222–1231. [CrossRef]

- Athaya, T., Ripan, R.C., Li, X., Hu, H., 2023. Multimodal deep learning approaches for single-cell multi-omics data integration. Briefings in Bioinformatics 24, bbad313. [CrossRef]

- Ausmees, K., Nettelblad, C., 2022. A deep learning framework for characterization of genotype data. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 12, jkac020. [CrossRef]

- Baird, D.A., Liu, J.Z., Zheng, J., Sieberts, S.K., Perumal, T., Elsworth, B., Richardson, T.G., Chen, C.-Y., Carrasquillo, M.M., Allen, M., Reddy, J.S., De Jager, P.L., Ertekin-Taner, N., Mangravite, L.M., Logsdon, B., Estrada, K., Haycock, P.C., Hemani, G., Runz, H., Smith, G.D., Gaunt, T.R., AMP-AD eQTL working group, 2021. Identifying drug targets for neurological and psychiatric disease via genetics and the brain transcriptome. PLoS Genet 17, e1009224. [CrossRef]

- Baker, E., Leonenko, G., Schmidt, K.M., Hill, M., Myers, A.J., Shoai, M., De Rojas, I., Tesi, N., Holstege, H., Van Der Flier, W.M., Pijnenburg, Y.A.L., Ruiz, A., Hardy, J., Van Der Lee, S., Escott-Price, V., 2023. What does heritability of Alzheimer’s disease represent? PLoS ONE 18, e0281440. [CrossRef]

- Bazzari, F.H., Bazzari, A.H., 2022. BACE1 Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease: The Past, Present and Any Future? Molecules 27, 8823. [CrossRef]

- Benkirane, H., Pradat, Y., Michiels, S., Cournède, P.-H., 2023. CustOmics: A versatile deep-learning based strategy for multi-omics integration. PLoS Comput Biol 19, e1010921. [CrossRef]

- Benner, C., Spencer, C.C.A., Havulinna, A.S., Salomaa, V., Ripatti, S., Pirinen, M., 2016. FINEMAP: efficient variable selection using summary data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 32, 1493–1501. [CrossRef]

- Brand, J.E., Zhou, X., Xie, Y., n.d. Recent Developments in Causal Inference and Machine Learning.

- Brombacher, E., Hackenberg, M., Kreutz, C., Binder, H., Treppner, M., 2022. The performance of deep generative models for learning joint embeddings of single-cell multi-omics data. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 962644. [CrossRef]

- Cano-Gamez, E., Trynka, G., 2020. From GWAS to Function: Using Functional Genomics to Identify the Mechanisms Underlying Complex Diseases. Front. Genet. 11, 424. [CrossRef]

- Chai, H., Zhou, X., Zhang, Z., Rao, J., Zhao, H., Yang, Y., 2021. Integrating multi-omics data through deep learning for accurate cancer prognosis prediction. Computers in Biology and Medicine 134, 104481. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K., Poirion, O.B., Lu, L., Garmire, L.X., 2018. Deep Learning–Based Multi-Omics Integration Robustly Predicts Survival in Liver Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 24, 1248–1259. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H., Zhao, Y., Qian, C., Cai, M., Zhang, R., Chu, M., Dai, J., Hu, Z., Shen, H., Chen, F., 2013. Weighted SNP Set Analysis in Genome-Wide Association Study. PLoS ONE 8, e75897. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Ortiz, M.E., Seo, Y., Posavi, M., Carceles Cordon, M., Clark, E., Jain, N., Charan, R., Gallagher, M.D., Unger, T.L., Amari, N., Skrinak, R.T., Davila-Rivera, R., Brody, E.M., Han, N., Zack, R., Van Deerlin, V.M., Tropea, T.F., Luk, K.C., Lee, E.B., Weintraub, D., Chen-Plotkin, A.S., 2022. GPNMB confers risk for Parkinson’s disease through interaction with α-synuclein. Science 377, eabk0637. [CrossRef]

- Dibaeinia, P., Ojha, A., Sinha, S., 2025. Interpretable AI for inference of causal molecular relationships from omics data. Sci. Adv. 11, eadk0837. [CrossRef]

- Dinu, I., Mahasirimongkol, S., Liu, Q., Yanai, H., Sharaf Eldin, N., Kreiter, E., Wu, X., Jabbari, S., Tokunaga, K., Yasui, Y., 2012. SNP-SNP Interactions Discovered by Logic Regression Explain Crohn’s Disease Genetics. PLoS ONE 7, e43035. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X., Liu, C., Dozmorov, M., 2021. Review of multi-omics data resources and integrative analysis for human brain disorders. Briefings in Functional Genomics 20, 223–234. [CrossRef]

- Elmaleh, D.R., Downey, M.A., Kundakovic, L., Wilkinson, J.E., Neeman, Z., Segal, E., 2021. New Approaches to Profile the Microbiome for Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disease. JAD 82, 1373–1401. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H., Chen, L., Knight, J.C., 2020. From genome-wide association studies to rational drug target prioritisation in inflammatory arthritis. The Lancet Rheumatology 2, e50–e62. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.D., Chen-Plotkin, A.S., 2018. The Post-GWAS Era: From Association to Function. The American Journal of Human Genetics 102, 717–730. [CrossRef]

- Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium, DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium, Yang, J., Ferreira, T., Morris, A.P., Medland, S.E., Madden, P.A.F., Heath, A.C., Martin, N.G., Montgomery, G.W., Weedon, M.N., Loos, R.J., Frayling, T.M., McCarthy, M.I., Hirschhorn, J.N., Goddard, M.E., Visscher, P.M., 2012. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet 44, 369–375. [CrossRef]

- Giambartolomei, C., Vukcevic, D., Schadt, E.E., Franke, L., Hingorani, A.D., Wallace, C., Plagnol, V., 2014. Bayesian Test for Colocalisation between Pairs of Genetic Association Studies Using Summary Statistics. PLoS Genet 10, e1004383. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V., Chitranshi, N., Gupta, V.B., 2024. Genetic Risk, Inflammation, and Therapeutics: An Editorial Overview of Recent Advances in Aging Brains and Neurodegeneration. Aging and disease 15, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Hao, X., Zeng, P., Zhang, S., Zhou, X., 2018. Identifying and exploiting trait-relevant tissues with multiple functional annotations in genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet 14, e1007186. [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, T., Kramer, S., 2023. A fair experimental comparison of neural network architectures for latent representations of multi-omics for drug response prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 24, 45. [CrossRef]

- Heilbron, K., Mozaffari, S.V., Vacic, V., Yue, P., Wang, W., Shi, J., Jubb, A.M., Pitts, S.J., Wang, X., 2021. Advancing drug discovery using the power of the human genome. The Journal of Pathology 254, 418–429. [CrossRef]

- Hill-Burns, E.M., Factor, S.A., Zabetian, C.P., Thomson, G., Payami, H., 2011. Evidence for More than One Parkinson’s Disease-Associated Variant within the HLA Region. PLoS ONE 6, e27109. [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, A.D., Kuan, V., Finan, C., Kruger, F.A., Gaulton, A., Chopade, S., Sofat, R., MacAllister, R.J., Overington, J.P., Hemingway, H., Denaxas, S., Prieto, D., Casas, J.P., 2019. Improving the odds of drug development success through human genomics: modelling study. Sci Rep 9, 18911. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M., Poschenrieder, J.M., Incudini, M., Baier, S., Fritz, A., Maier, A., Hartung, M., Hoffmann, C., Trummer, N., Adamowicz, K., Picciani, M., Scheibling, E., Harl, M.V., Lesch, I., Frey, H., Kayser, S., Wissenberg, P., Schwartz, L., Hafner, L., Acharya, A., Hackl, L., Grabert, G., Lee, S.-G., Cho, G., Cloward, M.E., Jankowski, J., Lee, H.K., Tsoy, O., Wenke, N., Pedersen, A.G., Bønnelykke, K., Mandarino, A., Melograna, F., Schulz, L., Climente-González, H., Wilhelm, M., Iapichino, L., Wienbrandt, L., Ellinghaus, D., Van Steen, K., Grossi, M., Furth, P.A., Hennighausen, L., Di Pierro, A., Baumbach, J., Kacprowski, T., List, M., Blumenthal, D.B., 2024a. Network medicine-based epistasis detection in complex diseases: ready for quantum computing. Nucleic Acids Research 52, 10144–10160. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M., Poschenrieder, J.M., Incudini, M., Baier, S., Fritz, A., Maier, A., Hartung, M., Hoffmann, C., Trummer, N., Adamowicz, K., Picciani, M., Scheibling, E., Harl, M.V., Lesch, I., Frey, H., Kayser, S., Wissenberg, P., Schwartz, L., Hafner, L., Acharya, A., Hackl, L., Grabert, G., Lee, S.-G., Cho, G., Cloward, M.E., Jankowski, J., Lee, H.K., Tsoy, O., Wenke, N., Pedersen, A.G., Bønnelykke, K., Mandarino, A., Melograna, F., Schulz, L., Climente-González, H., Wilhelm, M., Iapichino, L., Wienbrandt, L., Ellinghaus, D., Van Steen, K., Grossi, M., Furth, P.A., Hennighausen, L., Di Pierro, A., Baumbach, J., Kacprowski, T., List, M., Blumenthal, D.B., 2024b. Network medicine-based epistasis detection in complex diseases: ready for quantum computing. Nucleic Acids Research 52, 10144–10160. [CrossRef]

- Hormozdiari, F., Kostem, E., Kang, E.Y., Pasaniuc, B., Eskin, E., n.d. Identifying Causal Variants at Loci with Multiple Signals of Association.

- Hormozdiari, F., van de Bunt, M., Segrè, A.V., Li, X., Joo, J.W.J., Bilow, M., Sul, J.H., Sankararaman, S., Pasaniuc, B., Eskin, E., 2016. Colocalization of GWAS and eQTL Signals Detects Target Genes. The American Journal of Human Genetics 99, 1245–1260. [CrossRef]

- Hu, P., Jiao, R., Jin, L., Xiong, M., 2018. Application of Causal Inference to Genomic Analysis: Advances in Methodology. Front. Genet. 9, 238. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., Chu, L., Pei, J., Liu, W., Bian, J., 2021. Model complexity of deep learning: a survey. Knowl Inf Syst 63, 2585–2619. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., Richards, S., Carbone, M.A., Zhu, D., Anholt, R.R.H., Ayroles, J.F., Duncan, L., Jordan, K.W., Lawrence, F., Magwire, M.M., Warner, C.B., Blankenburg, K., Han, Y., Javaid, M., Jayaseelan, J., Jhangiani, S.N., Muzny, D., Ongeri, F., Perales, L., Wu, Y.-Q., Zhang, Y., Zou, X., Stone, E.A., Gibbs, R.A., Mackay, T.F.C., 2012. Epistasis dominates the genetic architecture of Drosophila quantitative traits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15553–15559. [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md.M., Wang, Y., Hu, P., 2018. Deep Learning Models for Predicting Phenotypic Traits and Diseases from Omics Data, in: Aceves-Fernandez, M.A. (Ed.), Artificial Intelligence - Emerging Trends and Applications. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., Ko, E., Mersha, T.B., 2022. A roadmap for multi-omics data integration using deep learning. Briefings in Bioinformatics 23, bbab454. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J., Berzuini, C., Keavney, B., Tomaszewski, M., Guo, H., 2022. A review of causal discovery methods for molecular network analysis. Molec Gen & Gen Med 10, e2055. [CrossRef]

- King, E.A., Davis, J.W., Degner, J.F., 2019. Are drug targets with genetic support twice as likely to be approved? Revised estimates of the impact of genetic support for drug mechanisms on the probability of drug approval. PLoS Genet 15, e1008489. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y., Yu, T., 2018. A graph-embedded deep feedforward network for disease outcome classification and feature selection using gene expression data. Bioinformatics 34, 3727–3737. [CrossRef]

- Lagemann, K., Lagemann, C., Taschler, B., Mukherjee, S., 2023. Deep learning of causal structures in high dimensions under data limitations. Nat Mach Intell 5, 1306–1316. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wu, F.-X., Ngom, A., 2016a. A review on machine learning principles for multi-view biological data integration. Brief Bioinform bbw113. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wu, F.-X., Ngom, A., 2016b. A review on machine learning principles for multi-view biological data integration. Brief Bioinform bbw113. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Montgomery, S.B., 2020. Identifying causal variants and genes using functional genomics in specialized cell types and contexts. Hum Genet 139, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Wei, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, Q., 2017. Deep Neural Networks for High Dimension, Low Sample Size Data, in: Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Presented at the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 2287–2293. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q., Yao, X., Hu, Y., Zhao, H., 2016. GenoWAP: GWAS signal prioritization through integrated analysis of genomic functional annotation. Bioinformatics 32, 542–548. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T., Zhang, A., 2019. Integrate multi-omics data with biological interaction networks using Multi-view Factorization AutoEncoder (MAE). BMC Genomics 20, 944. [CrossRef]

- Milne, R.L., Herranz, J., Michailidou, K., Dennis, J., Tyrer, J.P., Zamora, M.P., Arias-Perez, J.I., González-Neira, A., Pita, G., Alonso, M.R., Wang, Q., Bolla, M.K., Czene, K., Eriksson, M., Humphreys, K., Darabi, H., Li, J., Anton-Culver, H., Neuhausen, S.L., Ziogas, A., Clarke, C.A., Hopper, J.L., Dite, G.S., Apicella, C., Southey, M.C., Chenevix-Trench, G., kConFab Investigators, Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group, Swerdlow, A., Ashworth, A., Orr, N., Schoemaker, M., Jakubowska, A., Lubinski, J., Jaworska-Bieniek, K., Durda, K., Andrulis, I.L., Knight, J.A., Glendon, G., Mulligan, A.M., Bojesen, S.E., Nordestgaard, B.G., Flyger, H., Nevanlinna, H., Muranen, T.A., Aittomäki, K., Blomqvist, C., Chang-Claude, J., Rudolph, A., Seibold, P., Flesch-Janys, D., Wang, X., Olson, J.E., Vachon, C., Purrington, K., Winqvist, R., Pylkäs, K., Jukkola-Vuorinen, A., Grip, M., Dunning, A.M., Shah, M., Guénel, P., Truong, T., Sanchez, M., Mulot, C., Brenner, H., Dieffenbach, A.K., Arndt, V., Stegmaier, C., Lindblom, A., Margolin, S., Hooning, M.J., Hollestelle, A., Collée, J.M., Jager, A., Cox, A., Brock, I.W., Reed, M.W.R., Devilee, P., Tollenaar, R.A.E.M., Seynaeve, C., Haiman, C.A., Henderson, B.E., Schumacher, F., Le Marchand, L., Simard, J., Dumont, M., Soucy, P., Dörk, T., Bogdanova, N.V., Hamann, U., Försti, A., Rüdiger, T., Ulmer, H.-U., Fasching, P.A., Häberle, L., Ekici, A.B., Beckmann, M.W., Fletcher, O., Johnson, N., Dos Santos Silva, I., Peto, J., Radice, P., Peterlongo, P., Peissel, B., Mariani, P., Giles, G.G., Severi, G., Baglietto, L., Sawyer, E., Tomlinson, I., Kerin, M., Miller, N., Marme, F., Burwinkel, B., Mannermaa, A., Kataja, V., Kosma, V.-M., Hartikainen, J.M., Lambrechts, D., Yesilyurt, B.T., Floris, G., Leunen, K., Alnæs, G.G., Kristensen, V., Børresen-Dale, A.-L., García-Closas, M., Chanock, S.J., Lissowska, J., Figueroa, J.D., Schmidt, M.K., Broeks, A., Verhoef, S., Rutgers, E.J., Brauch, H., Brüning, T., Ko, Y.-D., The GENICA Network, Couch, F.J., Toland, A.E., The TNBCC, Yannoukakos, D., Pharoah, P.D.P., Hall, P., Benítez, J., Malats, N., Easton, D.F., 2014. A large-scale assessment of two-way SNP interactions in breast cancer susceptibility using 46 450 cases and 42 461 controls from the breast cancer association consortium. Human Molecular Genetics 23, 1934–1946. [CrossRef]

- Minikel, E.V., Painter, J.L., Dong, C.C., Nelson, M.R., 2024. Refining the impact of genetic evidence on clinical success. Nature 629, 624–629. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.H., Gilbert, J.C., Tsai, C.-T., Chiang, F.-T., Holden, T., Barney, N., White, B.C., 2006. A flexible computational framework for detecting, characterizing, and interpreting statistical patterns of epistasis in genetic studies of human disease susceptibility. Journal of Theoretical Biology 241, 252–261. [CrossRef]

- Mortezaei, Z., Tavallaei, M., 2021. Recent innovations and in-depth aspects of post-genome wide association study (Post-GWAS) to understand the genetic basis of complex phenotypes. Heredity 127, 485–497. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, H.L., John, C.R., Watson, D.S., Munroe, P.B., Barnes, M.R., Cabrera, C.P., 2020. Reaching the End-Game for GWAS: Machine Learning Approaches for the Prioritization of Complex Disease Loci. Front. Genet. 11, 350. [CrossRef]

- Niel, C., Sinoquet, C., Dina, C., Rocheleau, G., 2015. A survey about methods dedicated to epistasis detection. Front. Genet. 6. [CrossRef]

- Nott, A., Holtman, I.R., Coufal, N.G., Schlachetzki, J.C.M., Yu, M., Hu, R., Han, C.Z., Pena, M., Xiao, J., Wu, Y., Keulen, Z., Pasillas, M.P., O’Connor, C., Nickl, C.K., Schafer, S.T., Shen, Z., Rissman, R.A., Brewer, J.B., Gosselin, D., Gonda, D.D., Levy, M.L., Rosenfeld, M.G., McVicker, G., Gage, F.H., Ren, B., Glass, C.K., 2019. Brain cell type–specific enhancer–promoter interactome maps and disease - risk association. Science 366, 1134–1139. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Soh, J., Lee, H., 2021. Super.FELT: supervised feature extraction learning using triplet loss for drug response prediction with multi-omics data. BMC Bioinformatics 22, 269. [CrossRef]

- Passeri, E., Elkhoury, K., Morsink, M., Broersen, K., Linder, M., Tamayol, A., Malaplate, C., Yen, F.T., Arab-Tehrany, E., 2022. Alzheimer’s Disease: Treatment Strategies and Their Limitations. IJMS 23, 13954. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granado, J., Piñero, J., Furlong, L.I., 2022. Benchmarking post-GWAS analysis tools in major depression: Challenges and implications. Front. Genet. 13, 1006903. [CrossRef]

- Poirion, O.B., Jing, Z., Chaudhary, K., Huang, S., Garmire, L.X., 2021. DeepProg: an ensemble of deep-learning and machine-learning models for prognosis prediction using multi-omics data. Genome Med 13, 112. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.D., Hahn, L.W., Roodi, N., Bailey, L.R., Dupont, W.D., Parl, F.F., Moore, J.H., 2001. Multifactor-Dimensionality Reduction Reveals High-Order Interactions among Estrogen-Metabolism Genes in Sporadic Breast Cancer. The American Journal of Human Genetics 69, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Ronen, J., Hayat, S., Akalin, A., 2019. Evaluation of colorectal cancer subtypes and cell lines using deep learning. Life Sci. Alliance 2, e201900517. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, Y., Mackey, J.R., Lai, R., Franco-Villalobos, C., Lupichuk, S., Robson, P.J., Kopciuk, K., Cass, C.E., Yasui, Y., Damaraju, S., 2013. Assessing SNP-SNP Interactions among DNA Repair, Modification and Metabolism Related Pathway Genes in Breast Cancer Susceptibility. PLoS ONE 8, e64896. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.W., Fauvet, B., Moniatte, M., Lashuel, H.A., 2013. Alpha-synuclein Post-translational Modifications as Potential Biomarkers for Parkinson Disease and Other Synucleinopathies. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 12, 3543–3558. [CrossRef]

- Scholkopf, B., Locatello, F., Bauer, S., Ke, N.R., Kalchbrenner, N., Goyal, A., Bengio, Y., 2021. Toward Causal Representation Learning. Proc. IEEE 109, 612–634. [CrossRef]

- Sturma, N., Squires, C., Drton, M., Uhler, C., 2023. Unpaired Multi-Domain Causal Representation Learning. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., Crowley, C.A., Huang, L., Wen, J., Chen, J., Bao, E.L., Auer, P.L., Lettre, G., Reiner, A.P., Sankaran, V.G., Raffield, L.M., Li, Y., 2022. From GWAS variant to function: A study of ∼148,000 variants for blood cell traits. Human Genetics and Genomics Advances 3, 100063. [CrossRef]

- Tam, V., Patel, N., Turcotte, M., Bossé, Y., Paré, G., Meyre, D., 2019. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet 20, 467–484. [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, R.B., Islam, M.M., Sobhan, M., Luo, D., Mondal, A.M., 2024. MOGAT: A Multi-Omics Integration Framework Using Graph Attention Networks for Cancer Subtype Prediction. IJMS 25, 2788. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-King, J.P., Bronstein, M., Roblin, D., 2024. The Future of Machine Learning Within Target Identification: Causality, Reversibility, and Druggability. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 115, 655–657. [CrossRef]

- Tong, L., Mitchel, J., Chatlin, K., Wang, M.D., 2020. Deep learning based feature-level integration of multi-omics data for breast cancer patients survival analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 20, 225. [CrossRef]

- Uffelmann, E., Huang, Q.Q., Munung, N.S., De Vries, J., Okada, Y., Martin, A.R., Martin, H.C., Lappalainen, T., Posthuma, D., 2021. Genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Methods Primers 1, 59. [CrossRef]

- UK10K Consortium, Iotchkova, V., Ritchie, G.R.S., Geihs, M., Morganella, S., Min, J.L., Walter, K., Timpson, N.J., Dunham, I., Birney, E., Soranzo, N., 2019. GARFIELD classifies disease-relevant genomic features through integration of functional annotations with association signals. Nat Genet 51, 343–353. [CrossRef]

- Upton, A., Trelles, O., Cornejo-García, J.A., Perkins, J.R., 2016. Review: High-performance computing to detect epistasis in genome scale data sets. Brief Bioinform 17, 368–379. [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, N., Michailidis, G., 2022. Unsupervised Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Genet. 13, 854752. [CrossRef]

- Valous, N.A., Popp, F., Zörnig, I., Jäger, D., Charoentong, P., 2024. Graph machine learning for integrated multi-omics analysis. Br J Cancer 131, 205–211. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.S., Cooke Bailey, J.N., Lucas, A., Bradford, Y., Linneman, J.G., Hauser, M.A., Pasquale, L.R., Peissig, P.L., Brilliant, M.H., McCarty, C.A., Haines, J.L., Wiggs, J.L., Vrabec, T.R., Tromp, G., Ritchie, M.D., eMERGE Network, NEIGHBOR Consortium, 2016. Epistatic Gene-Based Interaction Analyses for Glaucoma in eMERGE and NEIGHBOR Consortium. PLoS Genet 12, e1006186. [CrossRef]

- Viaud, G., Mayilvahanan, P., Cournede, P.-H., 2022. Representation Learning for the Clustering of Multi-Omics Data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. and Bioinf. 19, 135–145. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Shao, W., Huang, Z., Tang, H., Zhang, J., Ding, Z., Huang, K., 2021. MOGONET integrates multi-omics data using graph convolutional networks allowing patient classification and biomarker identification. Nat Commun 12, 3445. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.-H., Hemani, G., Haley, C.S., 2014. Detecting epistasis in human complex traits. Nat Rev Genet 15, 722–733. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X., Pique-Regi, R., Luca, F., 2017. Integrating molecular QTL data into genome-wide genetic association analysis: Probabilistic assessment of enrichment and colocalization. PLoS Genet 13, e1006646. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Chen, Z., Xiao, S., Liu, G., Wu, W., Wang, S., 2024. DeepMoIC: multi-omics data integration via deep graph convolutional networks for cancer subtype classification. BMC Genomics 25, 1209. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Xie, L., 2025. AI-driven multi-omics integration for multi-scale predictive modeling of causal genotype-environment-phenotype relationships. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 27, 265–277. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., Liu, Q., Zhou, J., Xie, M., Feng, J., Jiang, T., 2020. Quantifying functional impact of non-coding variants with multi-task Bayesian neural network. Bioinformatics 36, 1397–1404. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Weng, D., Li, D., Gu, Y., Ma, W., Liu, Q., 2024. Prior knowledge-guided multilevel graph neural network for tumor risk prediction and interpretation via multi-omics data integration. Briefings in Bioinformatics 25, bbae184. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Xing, Y., Sun, K., Guo, Y., 2021. OmiEmbed: A Unified Multi-Task Deep Learning Framework for Multi-Omics Data. Cancers 13, 3047. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yang, F., Yang, X., Li, Q., Li, N., Zhao, Y., 2024. MoCaGCN: Cancer Subtype Classification by Developing Causal Graph Structure Learning, in: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Medical Artificial Intelligence (MedAI). Presented at the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Medical Artificial Intelligence (MedAI), IEEE, Chongqing, China, pp. 617–625. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Liu, J.S., 2007. Bayesian inference of epistatic interactions in case-control studies. Nat Genet 39, 1167–1173. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Chen, F., Zhai, R., Lin, X., Diao, N., Christiani, D.C., 2012. Association Test Based on SNP Set: Logistic Kernel Machine Based Test vs. Principal Component Analysis. PLoS ONE 7, e44978. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).