1. Introduction

Malignant Hyperthermia (MH) is a rare, life-threatening, autosomal dominant disorder triggered by certain anesthetic agents, particularly volatile gases and depolarizing muscle relaxants like succinylcholine. It is caused by mutations affecting the type 1 ryanodine receptor (RYR1) gene on Chromosome 19, leading to uncontrolled calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, resulting in sustained muscle contraction, excessive heat production, metabolic acidosis, and if untreated, multi-organ failure. Though uncommon, MH has been reported in patients undergoing cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), with only 30 documented cases in the literature. CPB complicates MH recognition and management, as active rewarming can serve as a potential trigger, and hypothermia may mask early symptoms [

1].

The diagnosis of MH is primarily clinical, with early signs including sinus tachycardia, hypercarbia, metabolic acidosis, and muscle rigidity, particularly following administration of succinylcholine [

2]. The definitive diagnostic test involves a muscle biopsy to assess the skeletal muscle response to halothane and caffeine [

3]. In the perioperative setting, a high suspicion is necessary, particularly in patients with a personal or family history of MH.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), commonly referred to as brittle bone disease, is a rare inherited connective tissue disorder caused by mutations in COL1A1 or COL1A2, which encode type 1 collagen. While OI is primarily associated with skeletal fragility and frequent fractures, it can also affect extra-skeletal structures, including the cardiovascular system. The most frequently reported cardiac manifestations involve left-sided heart valves, particularly aortic and mitral regurgitation, as well as aortic root dilation. Additionally, OI has been linked to perioperative hyperpyrexia, metabolic acidosis, and an increased risk of respiratory and coagulation dysfunction, all of which pose significant anesthetic and surgical challenges [

4].

The co-existence of MH and OI in a single patient undergoing aortic root replacement with hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) presents an exceptionally rare and complex clinical scenario. Hypothermia during CPB creates unique challenges as it may both mask and exacerbate MH-associated complications. Furthermore, the fragile vasculature in OI also increases the risks of aortic surgery, while respiratory and metabolic instability in both conditions raises concerns for postoperative recovery.

Here, we present a case of a 62-year-old male with biopsy-confirmed MH, OI, a bicuspid aortic valve, and an ascending aortic aneurysm, who underwent cardiac surgery involving HCA at 25°C. Despite meticulous perioperative planning, including avoidance of triggering anesthetic agents, slow rewarming, and prompt administration of dantrolene at the first sign of deterioration, the patient ultimately succumbed from complications likely associated with the combination of MH and OI.

2. Case Report

A 62-year-old gentleman was referred for a cardiology consult due to progressive shortness of breath and exertional chest heaviness over a six months period, that had significantly limited his exercise tolerance.

He was an ex-smoker, and his past medical history included hypertension, osteogenesis imperfecta and malignant hyperthermia, which had been confirmed by muscle biopsy. His MH susceptibility was particularly significant, with five of his family members having died from MH-related crises. He had also suffered a previous ischemic stroke, for which he was on Clopidogrel, and had a long-standing history of suicidal depression, managed with Venlafaxine. Given his diagnosis of malignant hyperthermia, he previously underwent a total knee replacement and spinal surgery under spinal anesthesia to avoid any potential risks of anesthesia.

A transthoracic echocardiogram (ECHO) revealed a bicuspid aortic valve with moderate aortic stenosis (mean gradient of 28mmHg, peak gradient of 47mmHg, aortic valve area of 1.44cm

2, Doppler Velocity Index =0.30cm

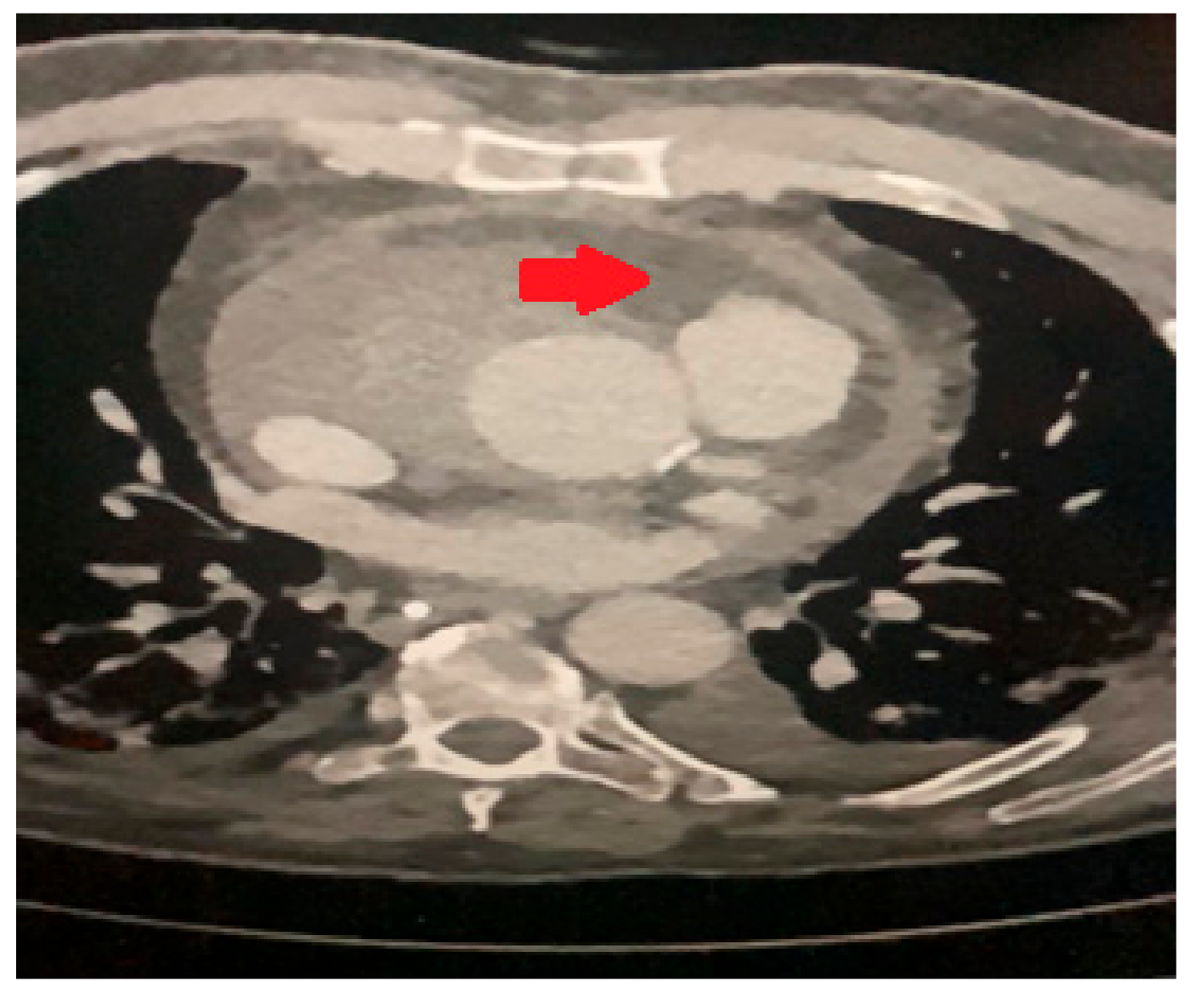

2), moderate aortic regurgitation, and a severely dilated left ventricle with moderate systolic dysfunction (LVEF of 45%). Additionally, the aortic root and mid-ascending aorta were dilated, measuring 50mm. A computer tomography (CT) scan further confirmed the presence of aortic dilation, with specific measurements (

Figure 1) showing an annulus diameter of 38 x 28mm, a sinus of Valsalva diameter of 40 x 36mm, a sino-tubular junction of 45mm, and a mid-ascending aortic dimension of 50mm. The distal ascending aorta was also 50mm, while the mid-arch measured 30mm. A CT coronary angiogram did not reveal any significant coronary artery disease.

The patient was reviewed in our High-Risk Anesthetic Clinic in view of his complicated clinical picture. It was agreed that anesthesia would be managed using propofol and non-depolarizing muscle relaxants, while careful temperature control would be ensured with slow rewarming on cardiopulmonary bypass. Furthermore, Dantrolene would be readily available in the event of an MH crisis.

Following a multidisciplinary discussion, the consensus was that the patient required aortic valve replacement (AVR) and aortic root/ascending aorta replacement (AAR), in accordance with ESC/EACTS Guidelines for aortic disease and valvular heart disease [

5].

Anesthesia was successfully induced using non-triggering agents. As a distal anastomosis of the tube graft to the arch of the aorta was required, hypothermic circulatory arrest was deemed necessary to facilitate the procedure. Standard cardiopulmonary bypass was established and the patient was cooled to 25°C. The heart was arrested with St Thomas’ cardioplegia solution antegradely with further doses administered at 20-minute intervals via direct coronary intubation and the composite graft when this was constructed.

At operation, the aortic valve was confirmed to be bicuspid (Type 0). The aortic root was grossly dilated and the sinuses and ascending aorta were very thin. An aortic root replacement was thus deemed necessary. The native aortic valve was excised and the ascending aorta was resected and sent for histology. The root was replaced with a Carbomedics (Corcym, Italy) composite valve and tube graft with re-implantation of the coronary buttons. A 9-minute period of circulatory arrest allowed for the distal anastomosis to be completed. The total aortic cross-clamp time was 139 minutes, while cardiopulmonary bypass duration was 248 minutes. Considering his susceptibility to MH, the patient was gently re-warmed to 34°C (core temperature) before being weaned off CPB in a stable condition. Throughout the procedure, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring showed no significant drops in cerebral oxygenation.

He was extubated on postoperative day one. However, by day seven, he developed worsening respiratory distress, necessitating reintubation due to type 1 respiratory failure with high oxygen requirements (FiO2 0.7-1.0). Despite broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, high-dose methylprednisolone and ventilation in the prone position, there was minimal improvement in ventilatory requirements. During this period, he also developed hemodynamic instability, requiring inotropic and vasopressor support and several DC cardioversions for atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia.

A transesophageal echocardiogram (TOE) identified a collection around the aortic root. CT thorax (

Figure 2) confirmed bilateral lung consolidation and a small hematoma collection around the aortic root in keeping with recent surgery. As it was possible that the cardiac arrhythmias and hemodynamic instability were related to the peri-aortic hematoma, the decision was made to proceed with a re-sternotomy and drainage. This was performed on postoperative day thirteen with drainage of a moderate serous pericardial effusion and evacuation of the periaortic hematoma. An intra-aortic balloon pump was also inserted.

His respiratory failure persisted despite these interventions with no significant positive microbiology, prompting a suspicion of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). His condition further deteriorated with the onset of renal failure, requiring replacement therapy for severe acidosis and hyperkalemia. A repeat echocardiogram confirmed the aortic valve was functioning satisfactorily, with no aortic regurgitation and preserved LV function. Throughout this period his temperature had not exceeded 37.8°C, then spiked suddenly to 40°C on nasal probe and 42°C on TOE probe). In response, Dantrolene (2.5mg/kg) was administered intravenously, and active cooling with the Arctic Sun Temperature Management system (Medivance/Bard) was initiated, successfully lowering his body temperature to 35°C and vasoconstrictors were weaned off.

Despite these measures, he remained critically unwell, with severe respiratory failure requiring escalating ventilator support, worsening renal failure, and new-onset sinus bradycardia without AV block. He was deemed unsuitable for veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) due to prolonged mechanical ventilation. By postoperative day 33, his oxygen requirements had further escalated to FiO2 1.0 and following discussions with family, a decision was made to withdraw life-sustaining treatment and the patient passed away.

3. Discussion

This case highlights the extraordinary complexity of managing a patient with both malignant hyperthermia and osteogenesis imperfecta undergoing major cardiac surgery with hypothermic circulatory arrest. Despite comprehensive preoperative planning and meticulous intraoperative management, the patient developed late-onset hypermetabolism, multi-organ failure, and ultimately succumbed to complications.

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a rare but life-threatening disorder that has traditionally been considered a perioperative event, primarily triggered by exposure to volatile anesthetic agents or depolarizing neuromuscular blockers such as succinylcholine and halogenated hydrocarbon anesthetic vapor [

6]. However, it has also been reported among patients undergoing cardiac surgeries involving cardiopulmonary bypass, raising concerns about its unique presentation and management challenges in this setting. Diagnosing MH can be difficult, as symptoms may present subtly and the underlying trigger is not always identifiable. Without prompt intervention, mortality can reach up to 75% [

7].

Due to its rarity, the management of MH-susceptible patients in cardiac surgery is largely derived from a limited number of case reports. Standard recommendations include avoiding triggering agents, active cooling, and intravenous Dantrolene administration. However, even when these measures are successfully implemented, severe complications such as renal failure, heart failure, and bowel ischemia can still occur, as seen in this case.

Malignant hyperthermia has been reported in patients undergoing surgeries involving cardiopulmonary bypass, though cases remain rare. Butala et al. recently reviewed the diagnosis and treatment of MH during cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass [

6]. They identified 17 cases of newly diagnosed or presumed MH. Of this group, the majority were treated with Dantrolene and a survival rate of 88% (15 out of 17 patients) was observed. Additionally, 13 cases of known malignant hyperthermia-susceptible patients were also identified, all of whom received tailored management that included the use of non-triggering agents, meticulous preparation of mechanical ventilators, close multiparametric monitoring, avoidance of hypothermia during cardiopulmonary bypass, slow rewarming after cardiopulmonary bypass, “off-pump” coronary artery bypass graft when possible, continued high-level vigilance throughout the postoperative period, and in many cases Dantrolene prophylaxis.

Supportive treatment also involved optimization of oxygenation and ventilation, discontinuation of triggering agents, correction of hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis, cooling as necessary with cold isotonic crystalloid and ice packs, and cardiovascular support as needed.

Dantrolene functions as a postsynaptic muscle relaxant that plays a crucial role in the treatment and prevention of malignant hyperthermia (MH). It exerts its effect by directly inhibiting the release of calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle cells, thereby preventing the uncontrolled calcium accumulation that leads to sustained muscle contraction, hypermetabolism, and excessive heat production. By blocking the ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR1) channels, Dantrolene effectively reduces intracellular calcium levels, which in turn helps to relax the muscles, counteract the hypermetabolic state, and stabilize cardiovascular and respiratory function. Its mechanism of action specifically targets skeletal muscle, without affecting cardiac or smooth muscle, making it the only pharmacologic agent capable of reversing an MH crisis. However, its prophylactic use remains controversial, even among patients with confirmed MH susceptibility or a strong family history. [

9] Current guidelines do not routinely recommend preemptive administration, as there is insufficient evidence to justify its use in all cases. Furthermore, Butala et al noted inconsistencies in Dantrolene’s pharmacokinetics in the CPB setting [

6], highlighting existing gaps in knowledge regarding its optimal use in cardiac surgery. In our case, Dantrolene was not given prophylactically but was administered once MH was suspected in the late postoperative period. Whether earlier intervention could have improved the outcome remains uncertain.

Hypothermia during cardiopulmonary bypass introduces additional challenges, particularly in MH detection and management. Cooling may suppress early metabolic warning signs, potentially delaying diagnosis, while active rewarming has been implicated as a potential MH trigger. For this reason, it is recommended that MH-susceptible patients undergo slow, controlled rewarming, maintaining core temperatures below 36°C [

8]. In this case, the patient was rewarmed slowly to only 34°C, yet still developed a delayed hypermetabolic crisis, suggesting CPB-associated temperature shifts alone may not fully explain MH activation in this context.

While MH is well-recognized as a hypermetabolic disorder, osteogenesis imperfecta has also been associated with perioperative hyperpyrexia, metabolic acidosis, and respiratory complications, though the exact mechanism remains unclear. In contrast to fulminant MH, OI-related hyperthermia is often self-limiting and does not present with generalized rigidity or severe hypercarbia. [

10]. Some patients with OI have exhibited intraoperative hyperthermia and tachycardia, yet muscle biopsy testing ruled out MH, supporting the hypothesis that OI may involve a separate, distinct metabolic dysregulation [

11].

During the aortic multidisciplinary meeting, concerns were raised regarding the need for hypothermic circulatory arrest to facilitate the procedure in this patient. However, the consensus was that surgery was strongly indicated based on current guidelines. Despite an appropriate pre-operative work-up, meticulous intraoperative monitoring, gentle rewarming on cardiopulmonary bypass, and the administration of Dantrolene, the outcome was ultimately fatal. It is possible the combination of hypothermic circulatory arrest, malignant hyperthermia, and osteogenesis imperfecta is a bridge too far and avoidance of surgery in these patients might be warranted.

4. Conclusions

This case highlights the complex challenges of managing a patient with both malignant hyperthermia and osteogenesis imperfecta undergoing major cardiac surgery with hypothermic circulatory arrest. Despite extensive perioperative precautions, the patient experienced a delayed hypermetabolic crisis, ultimately leading to multi-organ failure and a fatal outcome. The interplay between MH and OI in this setting remains poorly understood, raising important considerations regarding perioperative metabolic stability, temperature modulation strategies, and tailored anesthetic management in high-risk patients.

Although malignant hyperthermia is primarily recognized as a pharmacogenetic disorder of skeletal muscle, its occurrence in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass suggests that temperature shifts and metabolic stress may serve as additional triggers. The role of hypothermia in masking early signs of MH, as well as the potential for rewarming to precipitate a crisis, emphasizes the importance of intraoperative temperature control and prolonged postoperative monitoring.

The outcome of this case raises critical questions about the optimal management of MH-susceptible patients requiring major cardiovascular interventions. Given the high perioperative risk associated with both MH and OI, alternative approaches should be explored. Additionally, while prophylactic administration of Dantrolene is not routinely recommended, its potential role in reducing the risk of late postoperative MH warrants further investigation in patients at high risk of developing MH.

In conclusion, this case calls for the need for a highly individualized approach when managing patients with complex metabolic disorders undergoing major cardiac surgery. A multidisciplinary collaboration between surgeons, anesthesiologists, and intensivists is essential to anticipate potential complications, optimize perioperative management, and improve overall outcomes. Further research is needed to better understand the relationship between MH, OI, and metabolic crises, allowing for more effective strategies to enhance patient safety in similar high-risk scenarios.

Funding

This paper did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Lichtman AD, Oribabor C, Malignant Hyperthermia Following Systemic Rewarming After Hypothermic Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Anesth Analg. 2006 Feb;102(2):372-5.

- Litman RS, Smith VI, Green Larach M, Mayes L, Shukry M, Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States (MHAUS): Consensus statement on unresolved clinical questions concerning the management of patients with malignant hyperthermia. Anesth Analg. 2019 Apr;128(4):652-659.

- Rosenberg H, Davis M, James D, Pollock N, Stowell K, Malignant hyperthermia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007; 2: 21.

- Marom R, Rabenhorst BM, Morello R, Osteogenesis imperfecta: an update on clinical features and therapies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020 Oct; 183(4):R95-R106.

- 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of Valvular Heart Disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS).

- Butala B, Busada M, Cormican D, Malignant Hyperthermia: Review of Diagnosis and Treatment during Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018 Dec;32(6):2771-2779.

- Schneiderbanger D, Johannsen S, Roewer N et al. Management of malignant hyperthermia: diagnosis and treatment. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:355–362.

- Metterlein T, Zink W, Kranke E et al. Cardiopulmonary bypass in malignant hyperthermia susceptible patients: A systematic review of published cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141(6):1488-95.

- Hackl W, Mauritz W, Winkler M et al. Anaesthesia in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible patients without dantrolene prophylaxis: A report of 30 cases. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34:534–7.

- Porsborg P, Osteogenesis irnperfecta and malignant hyperthermia. Is there a relationship? Anaesthesia. 1996 Sep;51(9):863-5.

- Baum VC, O’Flaherty JE: Anesthesia for genetic, metabolic and dysmorphic syndromes of childhood, 2nd ed., Lippicott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong-Kong, Sydney, Tokyo 2007: 283–284.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).