Introduction

The impact of disasters on local and global economy and other development pillars cannot be overemphasized. Both developed and developing worlds have had their fair share of cyclones, earthquakes, floods, hurricanes etc. which have had far-reaching effects on the livelihoods of communities (Birkmann et al., 2010; Cannon, 2014; Djalante et al., 2017). As development experts and researchers opine, while hazards reverse hardly won development strides, they also present opportunities for improved institutional response and to rethink systems for integrating sustainable approaches for building resilient and sustainable livelihoods and critical infrastructure (Cannon, 2014; Djalante et al., 2017; Toinpre et al., 2025). This scholarly piece delves into institutional dimensions underpinning sustainable livelihoods which shape the manner with which individuals, communities and governments interact to facilitate reconstruction and recovery. As exemplified in recent research (Toinpre et al., 2024), It builds on underlying theoretical views on vulnerability and sustainable livelihood approaches viable for rethinking longer term recovery as indicated in founding and contemporary disaster risk management research. As disaster occurrences are consequences of hazards and vulnerability interactions, such elements are often driven by a community’s susceptibility, which is mainly addressed by a capacity to cope, adapt or respond to shocks or stresses (Blaikie et al., 2014; Cannon, 1994; Djalante et al., 2013).

The pioneer works of disaster risk management planning and emergency management researchers argue about the anthropogenic roots of these events where institutional actions or inactions could exacerbate disaster impacts (O'keefe et al., 1976; Quarantelli, 2000; Quarantelli & Dynes, 1977; Wisner et al., 2012). However, while other authors argue about the naturalness of these events as ‘an act of God’ or nature’s reaction to the immense pressures put on it (Dynes, 2000; Pelling, 2001), such interactions especially between political, economic and environmental processes and the structures that guide societal behaviors have become a crucial topic in academic and public debates (Blaikie et al., 2014; O'keefe et al., 1976; Tierney, 2012). In a nutshell, hazards may be rapid (e.g. earthquake or wildfire) or slow on-set (e.g. flood or drought) (Pelling, 2001; Quarantelli, 2000). Slow on-set events are often triggered by conscious or subconscious avoidance of strategies to reduce risks and may normally be manifested through vulnerable conditions of people living in hazard-prone areas or purely rooted in underdevelopment (Van Niekerk, 2015; Van Niekerk & Wisner, 2014). Other attributes associated with slow-onset hazards have been related to public behaviors or attitudes manifested in the form of minimal adherence to statutory regulations such as building codes and unplanned proximity to ocean/riverbanks (Pelling, 2001; Van Niekerk, 2015). Similarly, droughts lead to famine and low farm yield which in the longer-term results in malnutrition or low income or productivity. Just as rapid events present devastating impacts to critical infrastructure and livelihoods, slow-onset events are highly detrimental and may sometimes be overlooked.

Underpinned by systemic and structural dimensions of underrepresentation and deprivation, authors argue about the existential threats of sustainable development posed by limited access to basic fundamental human rights, freedoms and other forms of social and human capital (Altman, 2004; Sen, 2001). The state of political economy and other socio-economic and environmental conditions also put people at risk thus hindering them from reducing their own vulnerabilities (Djalante, 2012; Tierney, 2012). Coupled with the harsh realities of economic policies, the productive potential of communities to address risk conditions either by building embankments or retaining walls; taking up insurance premiums to cover costs of potential losses; or even stocking up on basic food supplies and essentials are now coming at a huge cost to those affected (Blaikie et al., 2014; Tierney, 2012). Thus, the need to continuously explore innovative strategies for facilitating sustainable livelihoods especially at the recovery stages in post-disaster.

Demystifying Theoretical and Practical Approaches to Sustainable Livelihoods

Improving livelihoods before and in the aftermath of disaster events has presented the academia, governments and civil society with daunting, ambiguous, complex and uncertain challenges calling for the need to explore root dimensions of vulnerability and longer-term solutions for risk reduction (Renn et al., 2022; Thomalla et al., 2005). As the Pressure and Release (PAR) Model opines, the progression of vulnerability often transitions from root causes (e.g. limited access to power, structures and resources) to dynamic pressures (e.g. lack of local institutions, ethics/standards, rights and freedoms etc.) and unsafe conditions (e.g. fragile economy, unsafe locations, low-income levels etc.) (Blaikie et al., 2014; Mileti & Gailus, 2005). Bearing in mind the devastating impacts of natural hazards on socio-economic and environmental systems, the ‘Access Model’ and ‘Sustainable Livelihoods’ (SL) approach to development were introduced to systemically address recovery both at the household level and beyond (Aven & Renn, 2020; Blaikie et al., 2014).

Although they are similar, the access model iterates through time to provide a precise understanding of how people may be impacted by hazards and their trajectories throughout an event (Blaikie et al., 2014). In addition, both approaches have been used to explain and analyze how individuals obtain livelihoods by drawing upon or combining human capital (i.e. skills, knowledge, health and energy); social capital (i.e. networks, groups, knowledge etc.); physical capital (i.e. infrastructure, technology, equipment etc.) amongst others (Blaikie et al., 2014; Twigg, 2015). The Access Model is economistic and can be precise, deterministic and quantitative, setting an iterative space for response, adaptation, coping and lessons learned through education (Blaikie et al., 2014; Chipangura et al., 2016). Nonetheless, this scholarly piece takes a critical look at progression towards ‘safety’ and ‘self-protection’ where managing risks is not only left at the mercy of key institutional actors such as governments and multinational corporations but diverse and inclusive where communities can be empowered to have a fair share of the responsibility to reduce vulnerability.

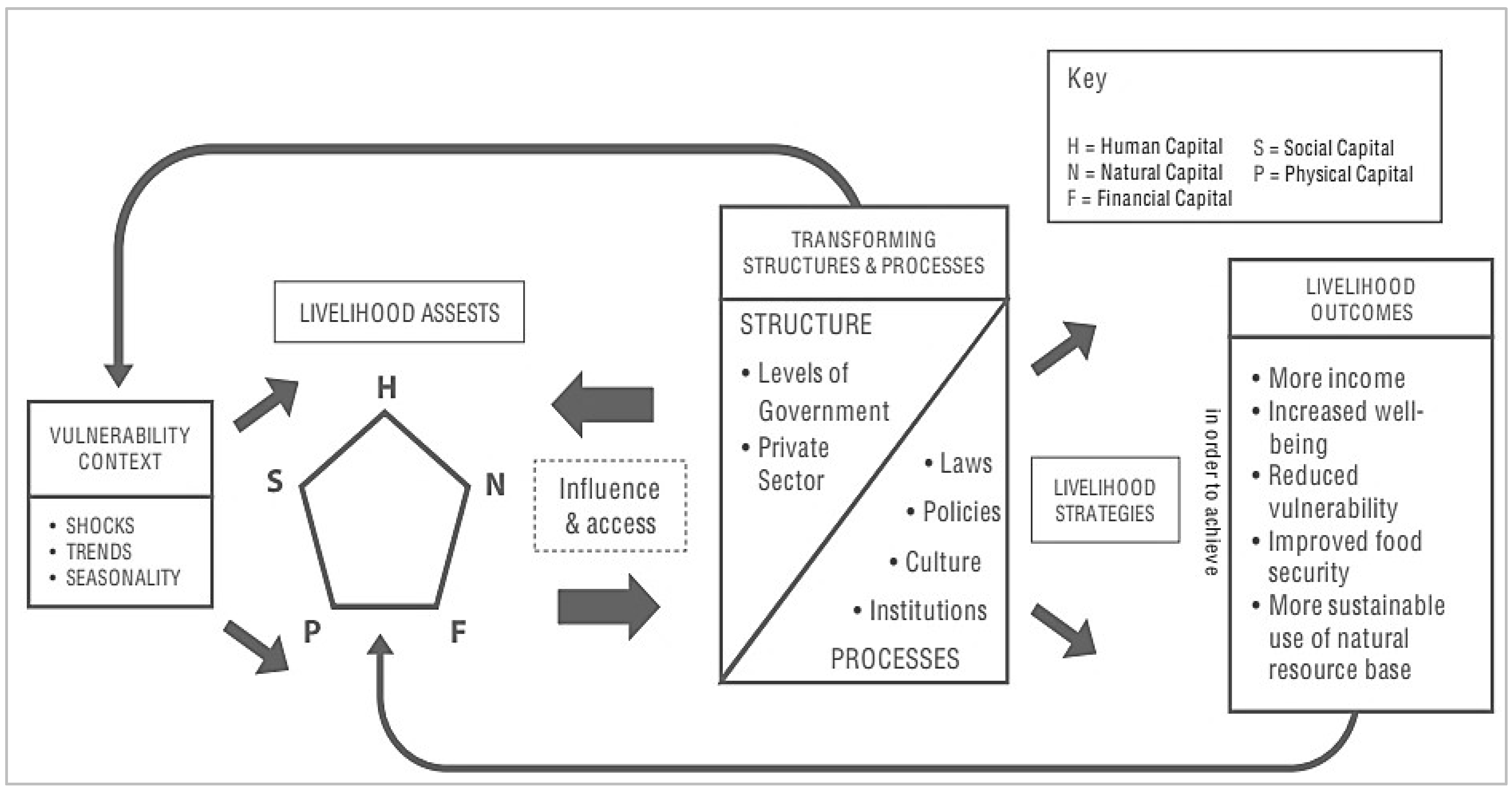

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework illustrates the interconnectedness between ‘institutional actors’ as crucial stakeholders for sustainable recovery and ‘the society’ where individuals can be empowered with the capacity to reduce their own risks and vulnerable conditions (Blaikie, 1995; Blaikie et al., 2014; UNDP, 2017). Livelihood support is an important aspect for many agencies within DRR organizational fields, but this requires continuous support, influence and access to expertise in relevant areas such as agriculture, environmental management, health, food security, nutrition, finance, marketing, education and training, community mobilization etc.(Twigg, 2015). However, interventions to improve livelihood outcomes through the transformation of structures (i.e. Federal, State and Local governments) and processes (i.e. laws, regulations, policies, culture etc.) is crucial and thus requires systemic rethinking for redevelopment/reconstruction in post-disaster scenarios.

Exploring Sustainable Livelihoods and Safety Net Initiatives in Africa and Asia

Bangladesh:

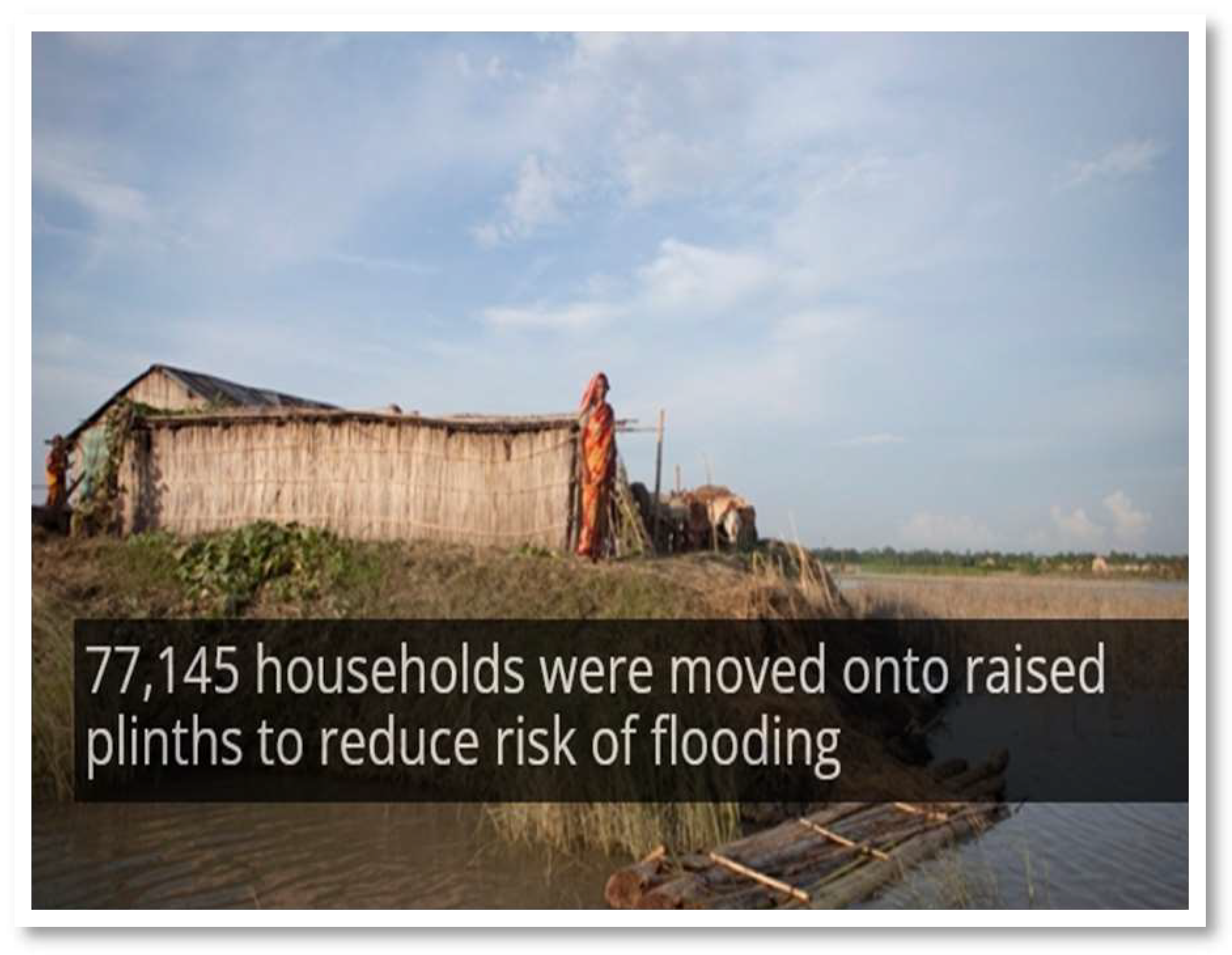

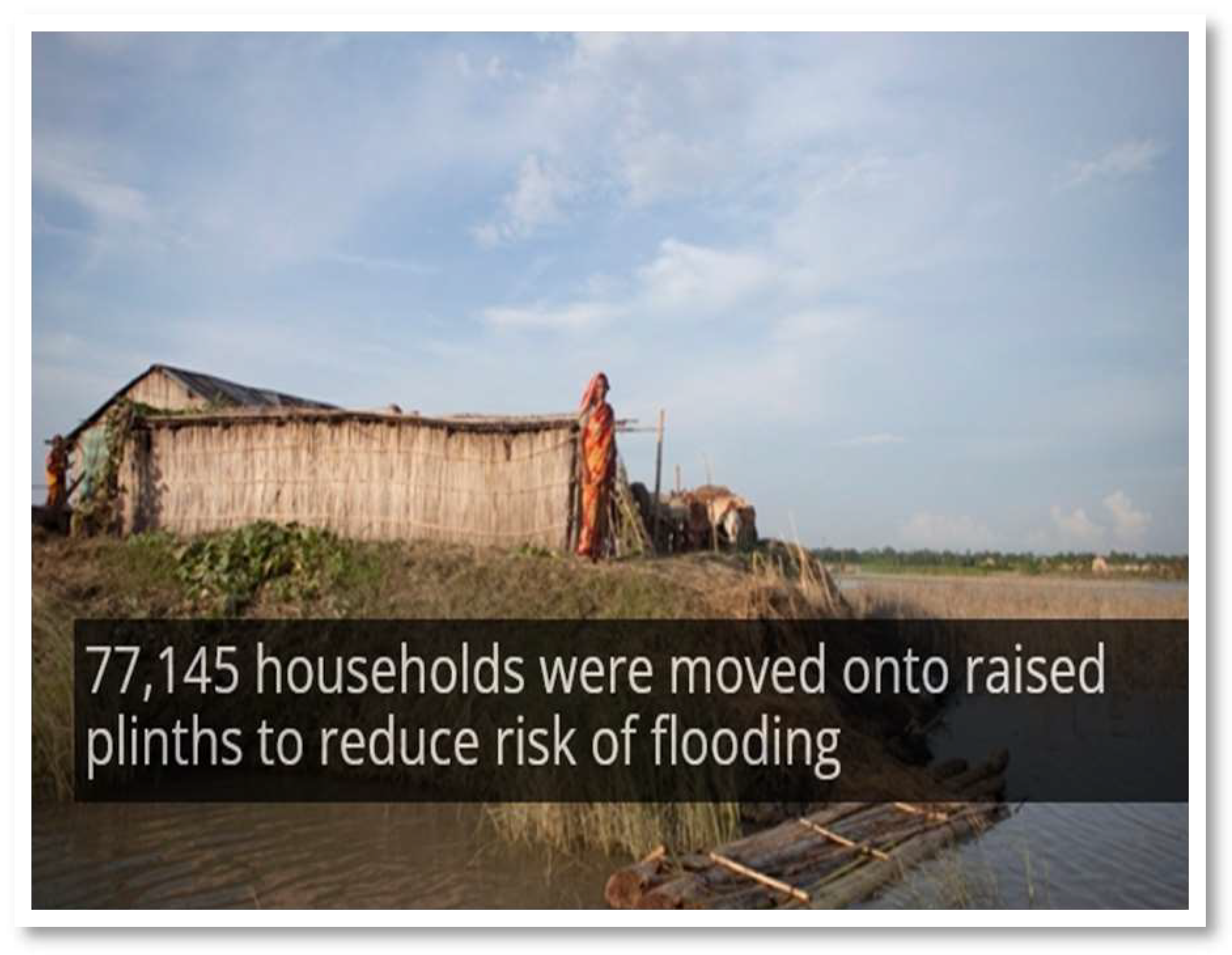

As part of initiatives to promote interventions in hazard-prone areas, The Chars Livelihoods Programme (CLP) was established in North-west Bangladesh to improve incomes and food security for over a million people.

The programme was established to support resilience through five complementary areas such as household infrastructure where homesteads were raised on a plinth to put them above flood levels; provision of livestock for rearing; social development through group meetings and trainings on disaster preparedness; credit schemes and financial capital; as well as disaster relief emergency funds to respond to inflation in food prices and housing repairs after cyclones. Source: Barrett et al. (2014)Source: http://www.clp-bangladesh.org/

The Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) was established by the Ethiopian government in 2005 in response to several droughts. Supported by international donor agencies, the programme made cash or food payments to about 7.8 million people to address food shortages and in return, recipients worked on community projects to benefit their communities in terms of road, school, clinic reconstruction; conservation of soil and water; reforestation etc.

Through its

$25 million contingency fund and Risk Financing Mechanism (RFM) 9.6 million people in districts covered by PSNP were assisted to obtain basic food supplies for up to three months which reduced household spending. Source: Hobson and Campbell (2012) Source:

https://essp.ifpri.info/productive-safety-net-program-psnp/

Unearthing Digital Paths Towards Humanitarian Response, Livelihood Recovery and Reconstruction

Post disaster recovery and reconstruction are basically centered around re-establishing livelihoods; reconnecting communities; providing access to basic safety nets or social capital; reconstructing critical infrastructure such as roads, bridges, hospitals, schools etc. (AIDR, 2021; Paton, 2019). Critical to achieving this is empowering communities through risk information updates via radio, press releases, television, posters, workshops etc. and financial interventions (e.g. credit/micro-finance schemes)(Twigg, 2015). Although several digital technologies and platforms have been launched to rapidly transform humanitarian crisis response, such avenues have proven beneficial for building volunteer networks (Chernobrov, 2018; ILO, 2021). Globally, economies are rapidly evolving and becoming web-based and digital in nature paving the way for new transitions towards digital-labour markets and humanitarian services (Easton-Calabria & Hackl, 2023). Digital labour platforms have increased fivefold between 2010-2020 (ILO, 2021). This is in view of the estimated 15.5 percent contribution to global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) which has grown two and a half times faster than global GDP over the past 15 years (WorldBank, 2022). Digitization has also been significant in crowdsourcing, crowd mapping and other humanitarian response and recovery operations.

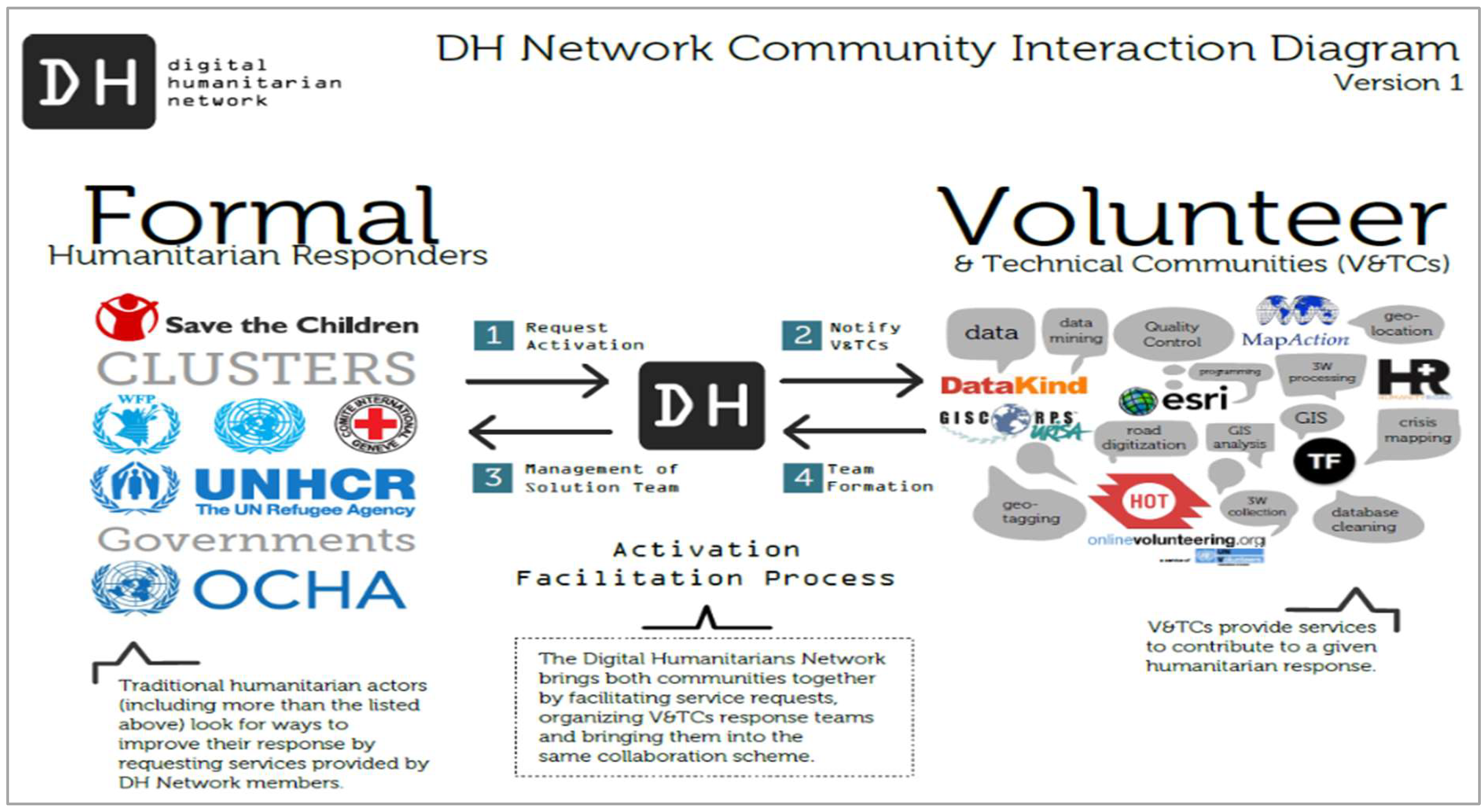

Inspired by the digital age, governments, civil society, social enterprises and international organizations in the humanitarian and development spheres are now delving into this space to harness and deploy resources in the shortest possible time to respond to disasters and to ameliorate risks while facilitating recovery operations (see

Figure 2). Moreso, the efforts of United Nations agencies are now becoming prominent in supporting programmes which seek to help refugees become self-reliant through digital or online remote work connected to various forms of digital finance (Easton-Calabria & Hackl, 2023).

Harnessing ICT Capabilities for Economic Resilience Through Digital Economy in Australia

With the advent of the digital age and transformative power of social media applications and tools, humanitarian interventions are now being designed by tech entrepreneurs to develop new solutions for supporting communities as part of renewed sustainable livelihoods approaches for vulnerability reduction. This approach has been focused on improving household income and providing safety nets for individuals and communities and can assist them to cope and adapt financially.

With the emergence of social media platforms such as weare8 which aims to support the Sustainable Development Goals, individuals can earn from watching advertisements and give towards charity while addressing global challenges in the areas of equality, health, peace, clean water, prosperity, animal care, climate, and education.

‘Everything is possible’ is Zoe’s mantra. "We just had to re-architect social media and the advertising capital flows so that the money flows through to people rather than stopping with big tech. Our sharing model works better for everyone – and changes the world in the process." – Zoe Kalar…founder of ‘weare8’. https://www.weare8.com/post/empowering-communities

Conclusions

Livelihood sustainability propels communities to advance in the aftermath of disaster events. Particularly in the recovery phase, livelihood strategies have been proven to demonstrate the propensity for communities to cope, recover, and possibly expand after hazard events. Successful livelihood recovery strategies may also lead to a variety of economic or non-economic benefits such as inclusion, personal safety, better political representation and enfranchisement, and maintenance of cultural heritage and values. In terms of humanitarian services, United Nations agencies such as the World Food Program and The UN Refugee Agency UNHCR have also transitioned to electronic vouchers and identity technologies such as the iris-recognition technology including Population Registration and Identity Management Ecosystem (PRIME). While other big tech social media platforms such as Meta (formerly Facebook), X (formerly twitter), Instagram, WhatsApp etc. have provided useful updates on disaster recovery and reconstruction, DRR organizational fields in Australia for example have launched apps such as ‘Fires-near-me’ and ‘Hazards-near-me’ aiding real-time hazard alerts to support digital interventions which are viable for preparedness, response and recovery. Further research is therefore recommended to explore systems that can be optimized for seamless interactive networking to facilitate livelihood recovery operations.

References

- AIDR. (2021). Australian Disaster Resilience Handbook Collection: Systemic Disaster Risk. In (First Edition 2021 ed.): Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience.

- Altman, J. (2004). Economic development and participation for remote Indigenous communities: best practice, evident barriers, and innovative solutions in the hybrid economy.

- Aven, T., & Renn, O. (2020). Some foundational issues related to risk governance and different types of risks. Journal of Risk Research, 23(9), 1121-1134. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A., Hannan, M., Alam, Z., & Pritchard, M. (2014). Impact of the chars livelihoods programme on the disaster resilience of chars communities. Innovation, Monitoring and Learning Division. http://clpbangladesh. org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/impact-of-clp-on-the-disaster-resilience-of-charcommunities-final. pdf.

- Birkmann, J., Buckle, P., Jaeger, J., Pelling, M., Setiadi, N., Garschagen, M., Fernando, N., & Kropp, J. (2010). Extreme events and disasters: a window of opportunity for change? Analysis of organizational, institutional and political changes, formal and informal responses after mega-disasters. Natural Hazards, 55, 637-655. [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P. (1995). Changing environments or changing views? A political ecology for developing countries. Geography, 203-214. [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., Davis, I., & Wisner, B. (2014). At risk: natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. Routledge.

- Cannon, T. (1994). Vulnerability analysis and the explanation of ‘natural’disasters. Disasters, development and environment, 1, 13-30.

- Cannon, T. (2014). Rural livelihood diversification and adaptation to climate change. Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change; Ensor, J., Berger, R., Huq, S., Eds, 55-76.

- Chernobrov, D. (2018). Digital volunteer networks and humanitarian crisis reporting. Digital Journalism, 6(7), 928-944. [CrossRef]

- Chipangura, P., Van Niekerk, D., & Van Der Waldt, G. (2016). An exploration of objectivism and social constructivism within the context of disaster risk. Disaster Prevention and Management, 25(2), 261-274. [CrossRef]

- Djalante, R. (2012). " Adaptive governance and resilience: the role of multi-stakeholder platforms in disaster risk reduction". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 12(9), 2923-2942. [CrossRef]

- Djalante, R., Garschagen, M., Thomalla, F., & Shaw, R. (2017). Introduction: Disaster risk reduction in Indonesia: Progress, challenges, and issues. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Djalante, R., Holley, C., Thomalla, F., & Carnegie, M. (2013). Pathways for adaptive and integrated disaster resilience. Natural Hazards, 69, 2105-2135. [CrossRef]

- Dynes, R. R. (2000). The dialogue between Voltaire and Rousseau on the Lisbon earthquake: The emergence of a social science view. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 18(1), 97-115. [CrossRef]

- Easton-Calabria, E., & Hackl, A. (2023). Refugees in the digital economy: The future of work among the forcibly displaced. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 4(3), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- GlobalSolutionsNetwork. (2014). Digital Humanitarian network.

-

leveraging Digital networks for Humanitarian response lighthouse Case Study. https://gsnetworks.org/wp-content/uploads/Digital-Humanitarian-Network.pdf.

- Hobson, M., & Campbell, L. (2012). How Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) is responding to the current humanitarian crisis in the Horn. Humanitarian Exchange Magazine, 53, 8-11.

- ILO. (2021). World employment and social outlook 2021: the role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work. International Labour Organisation (ILO).

- Mileti, D. S., & Gailus, J. L. (2005). Sustainable development and hazards mitigation in the United States: Disasters by design revisited. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 10, 491-504. [CrossRef]

- O'keefe, P., Westgate, K., & Wisner, B. (1976). Taking the naturalness out of natural disasters. Nature, 260(5552), 566-567. [CrossRef]

- Paton, D. (2019). Disaster risk reduction: Psychological perspectives on preparedness. Australian journal of psychology, 71(4), 327-341. [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M. (2001). Natural disasters. Social nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics, Blackwell Publishers, Inc., Malden, MA, 170-189.

- Quarantelli, E. L. (2000). Disaster planning, emergency management and civil protection: The historical development of organized efforts to plan for and to respond to disasters.

- Quarantelli, E. L., & Dynes, R. R. (1977). Different types of organizations in disaster responses and their operational problems.

- Renn, O., Laubichler, M., Lucas, K., Kröger, W., Schanze, J., Scholz, R. W., & Schweizer, P. J. (2022). Systemic risks from different perspectives. Risk analysis, 42(9), 1902-1920. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (2001). Development as Freedom Oxford Paperbacks. In: Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK.

- Thomalla, F., Cannon, T., Huq, S., Klein, R. J., & Schaerer, C. (2005). Mainstreaming adaptation to climate change in coastal Bangladesh by building civil society alliances. In Solutions to coastal disasters 2005 (pp. 668-684).

- Tierney, K. (2012). Disaster governance: Social, political, and economic dimensions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37, 341-363. [CrossRef]

- Toinpre, O., Jamie, M., & Gajendran, T. (2024). Analysing institutional responses towards disaster risk reduction: Challenges and antecedents. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 39(4), 61-70.

- Toinpre, O., Jamie, M., & Gajendran, T. (2025). Analysing disaster risk reduction organisational fields: pathways to resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Volume 40(No. 1), 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Twigg, J. (2015). Disaster risk reduction: Good Practice Review 9. O. D. I. Humanitarian Policy Group. http://www.odi.org/hpg.

- UNDP. (2017). Application of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework in Development Projects. UNDP: New York, NY, USA.

- Van Niekerk, D. (2015). Disaster risk governance in Africa: A retrospective assessment of progress against the Hyogo Framework for Action (2000-2012). Disaster Prevention and Management, 24(3), 397-416. [CrossRef]

- Van Niekerk, D., & Wisner, B. (2014). Integrating disaster risk management and development planning: experiences from Africa. Disaster management: International lessons in risk reduction, response and recovery, 1st edn., A. López-Carresi, M. Fordham, B. Wisner, I. Kelman, and JC Gaillard, 213-228.

- Wisner, B., Gaillard, J.-C., & Kelman, I. (2012). Handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction. Routledge.

- WorldBank. (2022). Digital Connectivity and Economic Diversification. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/devel_e/a4t_e/world_bank_digital_presentation_7_feb_2022_final_presented.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).