1. Introduction

Preeclampsia is a condition characterized by the new onset of hypertension and proteinuria—or organ dysfunction such as liver or kidney impairment—after 20 weeks of gestation. It is reported to occur in approximately 2–5% of pregnancies worldwide [

1]. This disorder significantly increases morbidity and mortality for both mothers and fetuses, and can lead to preterm delivery or severe complications (e.g., HELLP syndrome).

Traditionally, preeclampsia has been categorized into early-onset (occurring before 34 weeks of gestation) and late-onset (occurring at or after 34 weeks of gestation) forms. Early-onset preeclampsia is typically associated with marked placental insufficiency and vascular dysfunction, and tends to present with more severe clinical outcomes. In contrast, late-onset preeclampsia is thought to be more influenced by maternal factors (obesity, hypertension, metabolic risks, etc.) [

2,

3]. Although late-onset preeclampsia is often regarded as relatively mild, it still raises the risk of maternal–fetal complications, and frequently necessitates cesarean delivery or other medical interventions.

Currently, the only definitive cure for preeclampsia is delivery, and effective pharmacological interventions remain limited—especially for late-onset cases. For instance, low-dose aspirin has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of early-onset preeclampsia (before 34 weeks), but meta-analyses suggest that this prophylactic effect is less pronounced in late-onset disease [

4]. Hence, early risk stratification and management of late-onset preeclampsia remain crucial.

Several screening approaches have been proposed to enable early risk assessment of late-onset preeclampsia, combining maternal background factors (e.g., chronic hypertension, obesity, history of diabetes), uterine artery Doppler measurements, and serum biomarkers (e.g., PlGF, sFlt-1). However, changes in placental-derived factors are less pronounced in late-onset cases than in early-onset cases, and predictive models relying solely on placental angiogenic factors often reach a sensitivity of around only 40% [

2,

5]. Consequently, late-onset preeclampsia has proven more challenging to predict with high accuracy. While it has been noted that maternal factors (e.g., high BMI, advanced maternal age) play a major role in late-onset cases [

3,

6], the specific molecular mechanisms underlying this subtype have not yet been fully elucidated.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches have gained attention for their potential to integrate these complex risk factors multidimensionally. For example, analyses of large-scale electronic health records (EHR) incorporating diverse maternal background and laboratory data have demonstrated high-accuracy prediction with an AUC exceeding 0.9 [

6]. Nonetheless, most studies to date are retrospective and confined to specific cohorts, and thus lack external validation or prospective evaluation. Although attempts to merge multi-omics data (e.g., genetic risk scores, proteomics, metabolomics) have been reported [

7], cost and clinical feasibility remain significant barriers.

Parallel to developing more accurate predictive models, cell-free RNA (cfRNA) has recently garnered considerable attention as a promising source of biomarkers. cfRNA refers to free-floating RNA fragments found in maternal plasma; in pregnancy, these fragments include placental mRNA, offering a noninvasive method to capture biological information from both the mother and the fetus. Moreover, advancements in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) have made it possible to perform comprehensive analyses (cfRNA-seq) using small amounts of cfRNA, thereby facilitating the identification of molecular signatures distinguishing early- and late-onset preeclampsia [

2,

8].

Early-Onset Preeclampsia (EO-PE): This form is predominantly driven by placental abnormalities and immune dysregulation that begin early in gestation; distinct differential expression of cfRNA has been reported. For example, Moufarrej et al. demonstrated a high-accuracy model (AUC ≈ 0.9) using cfRNA derived from maternal plasma, suggesting an impairment of immune response and angiogenic pathways [

9].

Late-Onset Preeclampsia (LO-PE): Maternal comorbidities such as obesity or chronic hypertension play a substantial role, often diminishing the utility of purely placental biomarkers for high-sensitivity prediction. Indeed, many studies investigating cfRNA- or metabolite-based tests focus on overall PE risk and do not provide separate metrics (eg, AUC) for LO-PE alone. For example, while Maric et al. [

10] report robust performance in predicting PE, their models do not isolate late-onset cases. As a result, the true accuracy for LO-PE remains unclear, and some data even suggest that maternal factors may overshadow direct placental signals, leading to potentially lower AUCs for late-onset compared to early-onset PE. Moving forward, it will be crucial to refine LO-PE–specific molecular signatures—possibly through multi-omics approaches integrated with maternal clinical data—and validate such signatures in large external cohorts. This line of research is expected to clarify whether dedicated LO-PE models can outperform current one-size-fits-all approaches and ultimately improve risk stratification in this patient population.

This study focuses on LO-PE and aims to (1) identify cfRNA-based biomarker candidates specific to LO-PE, and (2) develop and evaluate machine learning models using these markers. More specifically, our objectives are:

To characterize cfRNA profiles in LO-PE and compare them with known markers predominantly associated with EO-PE.

To apply two feature selection strategies—(A) an approach based on differential expression analysis, and (B) an approach leveraging prediction errors (via the elastic net solution path)—and then assess LO-PE prediction performance in terms of AUC, sensitivity, and specificity.

To examine the performance trade-offs involved in simultaneously predicting both EO- and LO-PE, and to investigate how immune tolerance and metabolic pathways might be affected.

Ultimately, this study seeks to elucidate the mechanisms underlying late-onset preeclampsia—particularly those related to immune modulation and placental invasion—by leveraging cfRNA signatures, with the goal of informing future clinical management of preeclampsia.

2. Materials and Methods

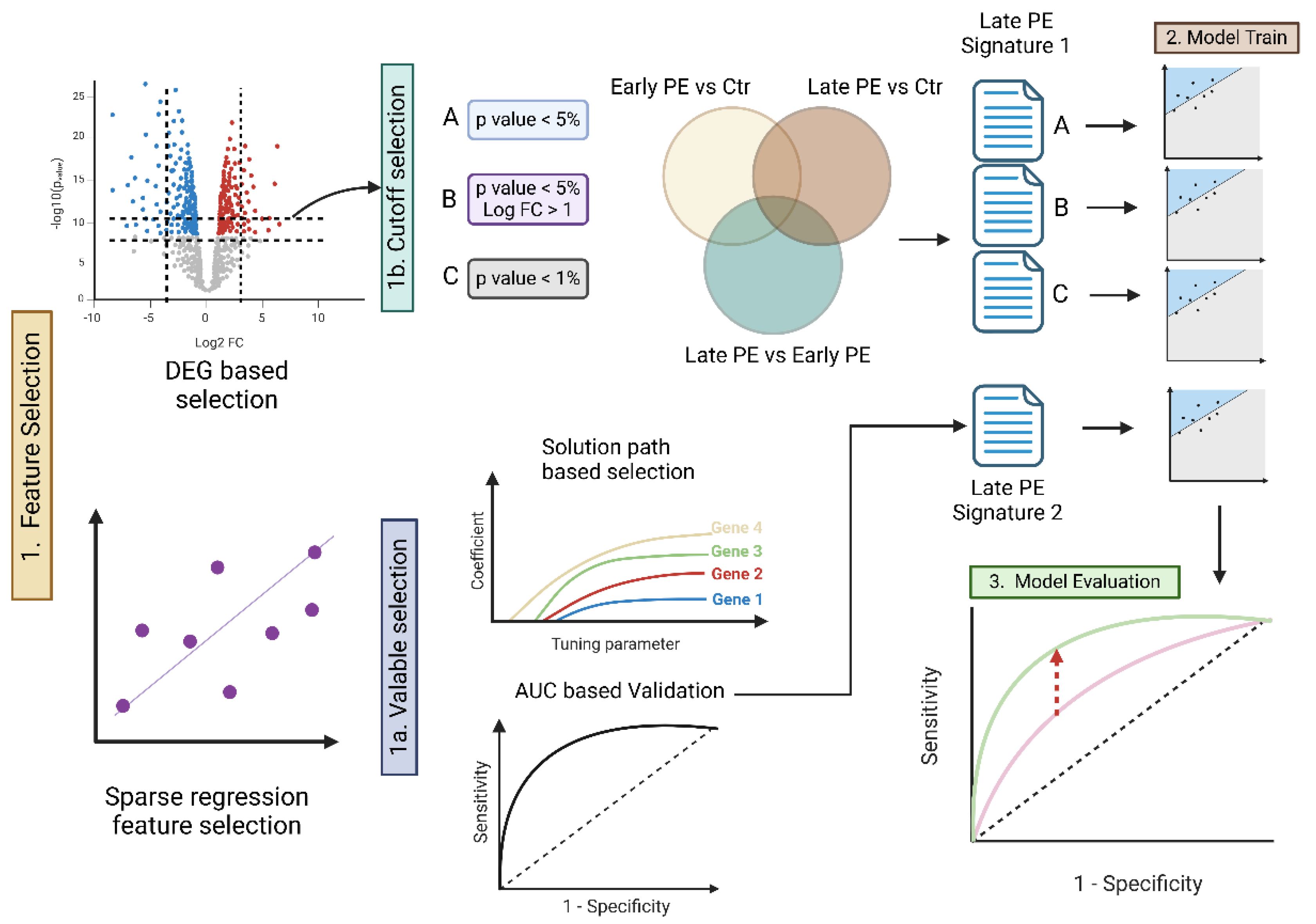

This study analyzed cfRNA sequencing data from a total of 48 samples, comprising EO-PE, LO-PE, and corresponding control groups for each subtype. Our goal was to identify potential biomarkers specifically associated with LO-PE and then construct and evaluate a diagnostic prediction model. The overall analytical workflow is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Dataset

The dataset is based on a cfRNA cohort described in Reference [

11], which includes 12 subjects with LO-PE, 12 subjects with EO-PE, and 12 controls for each group. Blood samples were collected at the time of PE diagnosis, and cfRNA (cell-free RNA) was extracted from maternal plasma for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Because the resulting RNA reads may include transcripts of both placental and maternal origin, it offers the intriguing possibility of capturing both maternal and placental factors. Given that our analysis involves a relatively small sample of 48 total specimens, special attention must be paid to sample-size limitations, the risk of overfitting, and the need for further external validation when constructing prediction models.

Strategy for Selecting Signature Genes

To identify biomarkers specific to LO-PE, we employed two approaches: differential expression gene (DEG) and an elastic net–based machine learning method leveraging prediction error. First, we used RNA-seq count data to conduct three intergroup comparisons: “early-onset vs. control,” “late-onset vs. control,” and “early-onset vs. late-onset.” We then used edgeR [

12,

13] and limma [

14,

15] to extract genes showing statistically significant differential expression. This process involved adjusting the p-values via the Benjamini–Hochberg method [

16] to control the false discovery rate (FDR), and using log2 fold change (logFC) values as an additional criterion for candidate gene selection. By excluding genes that were differentially expressed in both early- and late-onset groups, we obtained a set of candidate genes more specific to LO-PE.

Next, we applied an elastic net regression model using the glmnet [

17] package to tackle two classification tasks—“control vs. early-onset” and “control vs. late-onset.” We optimized the model’s hyperparameter, λ, through cross-validation to maximize prediction performance (AUC) and simultaneously minimize the number of genes used. By examining the solution path, we extracted genes that contributed most significantly to predicting LO-PE and designated them as late-onset–specific signatures for subsequent functional analysis. Since elastic net combines both

(Lasso) and

(Ridge) regularization, it effectively prevents overfitting and performs variable selection automatically. This makes it particularly useful for scenarios, such as ours, where one must narrow down important features from a large pool of genes.

Building and Evaluating the Predictive Model

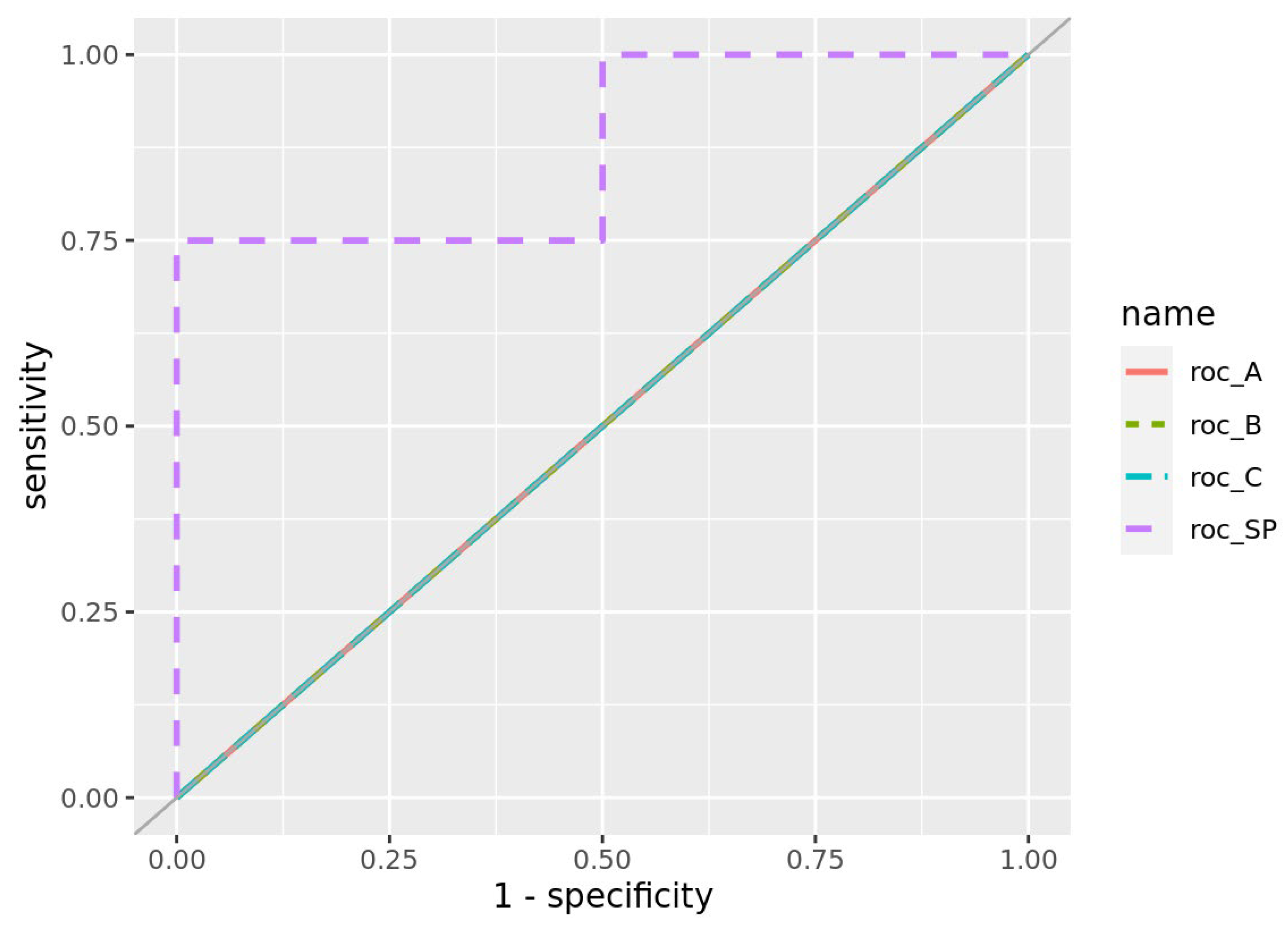

Using the selected signatures, we constructed models to predict LO-PE and evaluated their classification accuracy. Specifically, we adopted a holdout method, splitting the dataset into training (learning) and test (evaluation) sets: the training set consisted of healthy controls (n=16), early-onset cases (n=8), and late-onset cases (n=8), while the remaining samples formed the test set. We trained an elastic net model separately on the “early-onset signature” and the “late-onset signature,” and then computed the AUC to assess performance for the classifications “control vs. late-onset” and “control vs. early-onset.”

In addition, we evaluated performance when combining the early-onset and late-onset signatures to investigate whether handling both simultaneously would induce any performance trade-off. The AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve) serves as a comprehensive measure of a model’s ability to discriminate between true positives and false positives, with 1.0 indicating perfect accuracy and 0.5 indicating performance equivalent to random guessing. Where necessary, we also considered sensitivity and specificity to gain insight into the balance between false positives and false negatives.

Searching for Biomarker Candidates

We further investigated the late-onset signature genes extracted via prediction-error analysis by conducting gene set and pathway analyses to clarify their functional characteristics. Specifically, we cross-referenced the gene lists with databases such as Gene Ontology and KEGG to statistically evaluate the enrichment of pathways related to metabolism, immunity, and other processes, using Fisher’s exact test. Of particular interest were genes involved in immune tolerance or placental invasion, such as HLA-G and IL17RB; their inclusion in the signature could suggest associations with maternal immune dysregulation or trophoblast (EVT) dysfunction in LO-PE. We compared such findings against previous studies to explore their biological significance. Ultimately, this functional validation of late-onset–specific gene groups helps lay the groundwork for determining their potential clinical utility as diagnostic biomarkers in future research.

3. Results

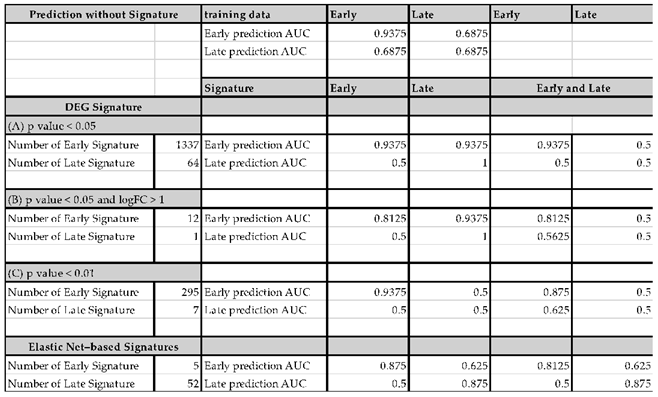

Identification of Signature Genes and Feature Selection

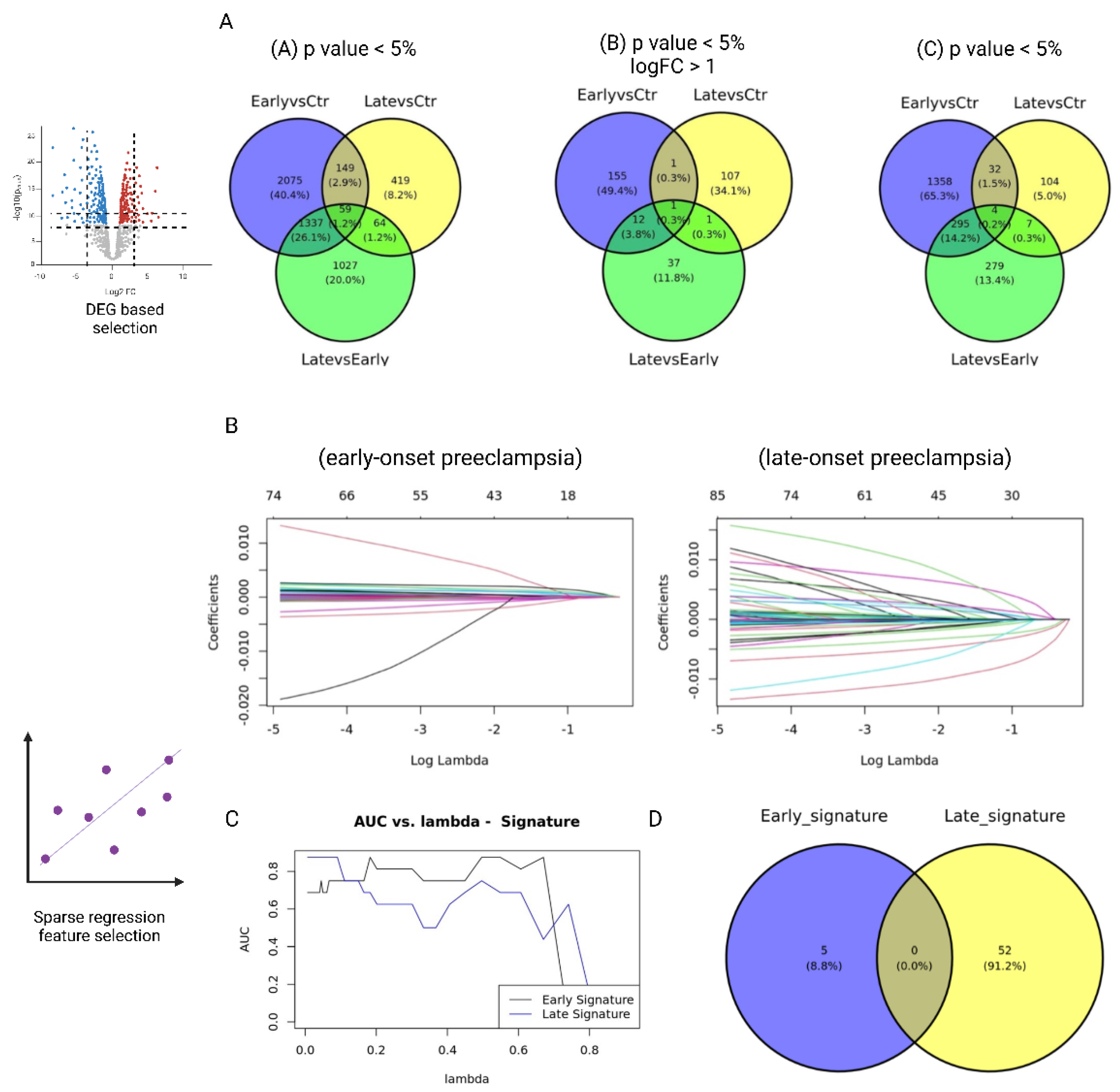

First, we performed differential expression analyses (DEG) for three comparisons—(1) early-onset PE vs. control, (2) late-onset PE vs. control, and (3) early-onset PE vs. late-onset PE—and generated lists of signature candidates by systematically varying the thresholds for p-values and log fold change (logFC) (1b in

Figure 1). We tested three cutoff conditions: (A)

p < 0.05, (B)

p < 0.05 & |logFC| > 1, and (C)

p < 0.01. As shown in

Figure 2A, the late-onset–specific signatures comprised 64 genes under condition A, 1 gene under condition B, and 7 genes under condition C. By contrast, the early-onset–specific signatures included 1,337 genes (A), 12 genes (B), and 295 genes (C).

When we used these results to train an Elastic Net model, the model that relied solely on the single gene KLRC4 (from condition B) attained an extremely high predictive performance for LO-PE (AUC = 1.0). However, given the limited sample size, we must consider the possibility of overfitting.

Candidate Selection via Prediction Error (Elastic Net Solution Path)

Next, we performed cross-validation on the Elastic Net model while varying the hyperparameter

λ in 50 increments, adopting the parameter setting that maximized predictive performance (AUC) while minimizing the number of selected genes (1a. in

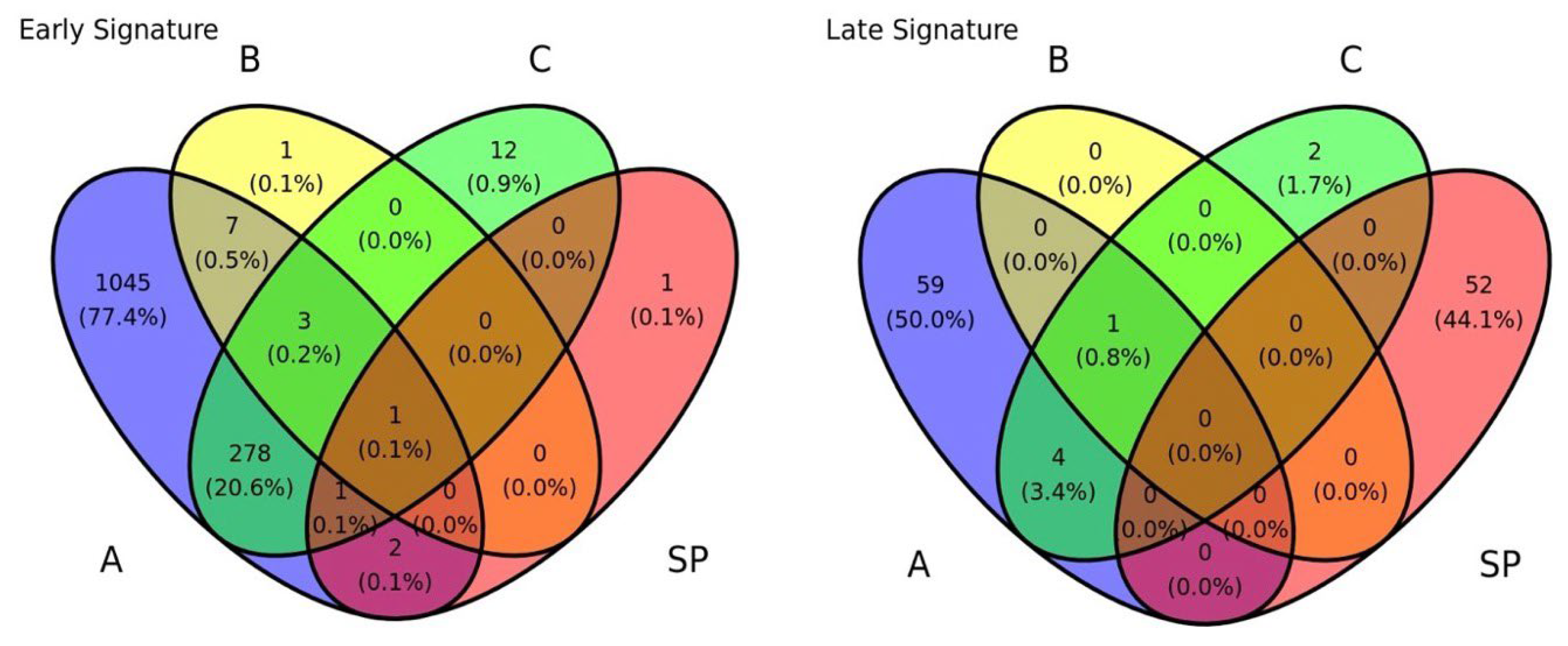

Figures 1). This approach extracted 52 genes as late-onset–specific signatures and 5 genes as early-onset–specific signatures (

Figure 3B-D). These sets exhibited very little overlap with the signatures identified via DEG analysis. As shown in the Venn diagram in

Figure 4, most genes from the solution-path (SP)–based signatures and those from the DEG-based approach did not overlap for both early- and late-onset PE, indicating that the two methods complement each other.

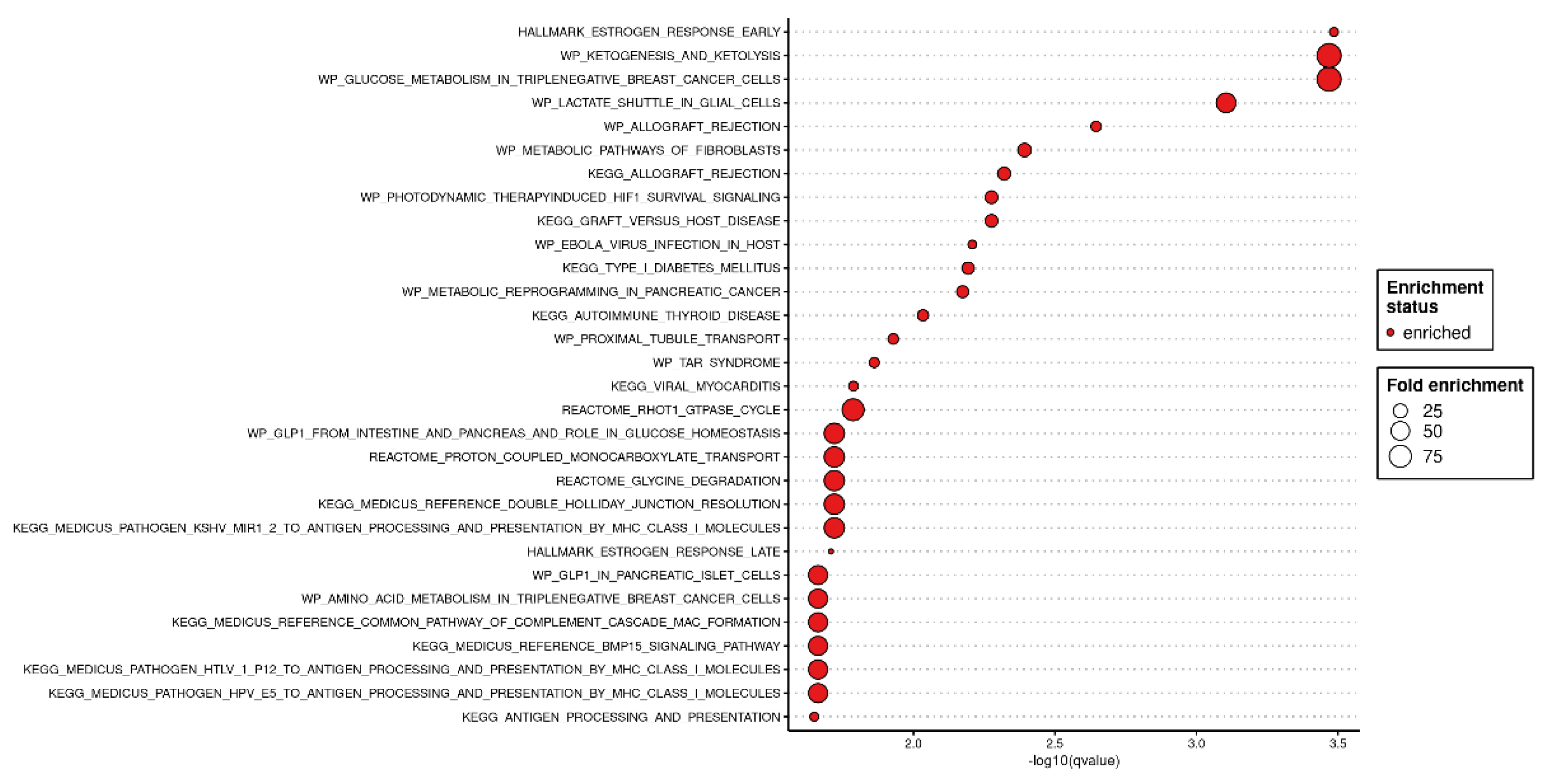

Candidate Biomarkers and Functional Analysis

From the 52 late-onset–specific genes identified by Elastic Net (

Figure 5), functional annotation revealed significant enrichment in immune-related and hormone/metabolic pathways. Among the top categories were Allograft Rejection and Estrogen Response.

Notably, HLA-G, IL17RB, and KLRC4—genes previously implicated in immune tolerance and trophoblast invasion—showed marked expression differences in the LO-PE group compared with controls. This observation suggests a potential role for impaired maternal–placental interactions.

4. Discussion

By developing a prediction model based on cfRNA profiles, this study demonstrates the potential to improve the AUC for predicting LO-PE from 0.69 (using conventional marker sets) to the 0.88–1.0 range by integrating late-onset–specific signatures. A major advantage of cfRNA-seq is that it enables noninvasive detection of both placental and maternal transcripts in maternal plasma. This feature offers the potential to identify useful biomarkers even in LO-PE, which is influenced more strongly by maternal factors than early-onset disease [

9,

18].

Among the immune- and hormone/metabolic pathways, HLA-G and IL17RB appear particularly relevant in LO-PE. Wedenoja et al. [

19] showed that HLA-G is significantly downregulated in preeclamptic placentas, indicating impaired fetal immune tolerance and reduced EVT infiltration—both hallmarks of shallow placental invasion. Likewise, IL17RB (the IL-25 receptor) fosters trophoblast proliferation; Liu et al. [

20] reported that diminished IL-17RB expression in PE placentas correlates with suboptimal placental development. Our findings reinforce that a late-onset immune “collapse” may be tied to early disruptions in maternal–fetal tolerance. Moreover, Ma et al. [

21] identified maternal KIR2DL4–fetal HLA-G genotype combinations that modulate preeclampsia risk, underscoring the genetic dimension of immune tolerance. Altogether, these data underscore how dysregulated HLA-G, IL17RB, and related genes (e.g., KLRC4) may drive LO-PE pathophysiology.

Although various immune and metabolic pathways have been proposed in late-onset preeclampsia (LO-PE), direct evidence for specific processes—such as Allograft Rejection, Estrogen Response, or Glycolysis—and for genes like HLA-G, IL17RB, and KLRC4 remains limited. Recent cfRNA-based studies nonetheless suggest that maternal–placental signaling abnormalities can be detected earlier than clinical onset, potentially offering a broader diagnostic window for LO-PE risk [

9,

10]. However, the current data primarily indicate general immune dysregulation rather than a uniquely “late-onset–specific” mechanism. Further validation—for example, in multi-ethnic cohorts and via single-cell or multiomics approaches—will be crucial to pinpoint precisely which genes or pathways diverge in LO-PE.

This study observed a trade-off wherein including both early- and late-onset subtypes in a single model caused decreased accuracy for at least one subtype. That outcome likely stems from the distinct etiological underpinnings of EO-PE vs. LO-PE [

22]. As noted by Moufarrej et al. [

9], while EO-PE exhibits prominent signals from the placental formation stage, LO-PE often entails maternal metabolic and immune dysfunction that becomes clinically apparent later in gestation. Accordingly, future research should focus on: (1) dynamic risk models incorporating longitudinal data by gestational week, or (2) algorithms that screen early- and late-onset cases separately and then generate an integrated risk score.

The present study is subject to several limitations and suggests directions for future search. First, each group comprised only 12 samples, emphasizing the need for validation in larger cohorts and multi-center collaborations to ensure the generalizability of these findings. Second, the predictive signatures identified in this study are sensitive to the choice of thresholds in differential expression analyses (p-values) and the setting of hyperparameters (λ in the Elastic Net model). Comparative evaluations under multiple conditions are therefore necessary to confirm the robustness of the proposed signatures.

Finally, there are challenges to clinical implementation, as measuring cfRNA and conducting NGS analyses remain expensive and require specialized equipment. Standardizing sample processing and streamlining analytic protocols will be critical for broader clinical adoption. Moreover, integrating other omics data (e.g., metabolomics, epigenomics) to provide a more comprehensive assessment of both maternal and placental status is an important next step.

5. Conclusions

This study identified late-onset–specific cfRNA signatures and demonstrated that incorporating them into an Elastic Net model substantially boosts predictive performance. Abnormalities in immune tolerance and metabolic systems—beyond what conventional early-onset markers can detect—may underlie the pathology of LO-PE. At the same time, challenges remain regarding sample size and model generalizability, pointing to the need for large-scale longitudinal studies and multi-omics integration. Ultimately, leveraging cfRNA-seq–based composite maternal–placental biomarkers in tandem with AI could significantly advance the early diagnosis and management of LO-PE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.; methodology, Y.M. and K.U.; formal analysis, A.N.; data curation, Y.M. and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.M. and K.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), grant numbers JP20H04282 and JP23K18505.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it used only publicly available, de-identified data, and did not involve direct interaction with human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable, because this study did not involve the collection of new data from human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data reanalyzed in this study are publicly available at NCBI dbGaP (accession number phs002017.v1.p1) and in the Supplementary Materials of [

https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz0131]. All newly derived data (including gene signature lists and statistical outputs) are presented in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grant Numbers JP20H04282 and JP23K18505.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC |

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| cfRNA |

Cell-Free RNA |

| DEG |

Differentially Expressed Gene |

| EHR |

Electronic Health Record |

| EVT |

Extravillous Trophoblast |

| HLA-G |

Human Leukocyte Antigen-G |

| IL17RB |

Interleukin-17 Receptor B |

| EO-PE |

Early-Onset Preeclampsia |

| LO-PE |

Late-Onset Preeclampsia |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NGS |

Next-Generation Sequencing |

| PE |

Preeclampsia |

| PlGF |

Placental Growth Factor |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| sFlt-1 |

Soluble fms-like Tyrosine Kinase-1 |

References

- Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, G.; et al. Development of a Prediction Model on Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning: A Retrospective Cohort Study in China. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 896969. [CrossRef]

- Erez, O.; Romero, R.; Maymon, E.; Chaemsaithong, P.; Done, B.; Pacora, P.; Panaitescu, B.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Hassan, S.S.; Tarca, A.L. The Prediction of Late-Onset Preeclampsia: Results from a Longitudinal Proteomics Study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181468. [CrossRef]

- Baylis, A.; Zhang, W.; et al. Prediction and Prevention of Late-Onset Pre-Eclampsia: A Systematic Review. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2024, 10, 1459289.

- Roberge, S.; Bujold, E.; Nicolaides, K.H. Aspirin for the Prevention of Preterm and Term Preeclampsia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 287-293.e1.

- Tan, M.Y.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; et al. Screening for Pre-Eclampsia by Maternal Factors and Biomarkers at 11–13 Weeks’ Gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 186–195.

- Jhee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, Y.A.; Kang, S.-W.; Kwon, J.-Y.; Park, J.T. Prediction Model Development of Late-Onset Preeclampsia Using Machine Learning-Based Methods. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0221202. [CrossRef]

- Kovacheva, V.P.; Eberhard, B.W.; Cohen, R.Y.; et al. Preeclampsia Prediction Using Machine Learning and Polygenic Risk Scores from Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors in Early and Late Pregnancies. Hypertension 2024, 81, 264–272. [CrossRef]

- Layton, A.T. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Preeclampsia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45.

- Moufarrej, M.N.; Vorperian, S.K.; Wong, R.J.; Campos, A.A.; Quaintance, C.C.; Sit, R.V.; Tan, M.; Detweiler, A.M.; Mekonen, H.; Neff, N.F.; et al. Early Prediction of Preeclampsia in Pregnancy with Cell-Free RNA. Nature 2022, 602, 689–694. [CrossRef]

- Marić, I.; Contrepois, K.; Moufarrej, M.N.; Stelzer, I.A.; Feyaerts, D.; Han, X.; Tang, A.; Stanley, N.; Wong, R.J.; Traber, G.M.; et al. Early Prediction and Longitudinal Modeling of Preeclampsia from Multiomics. Patterns (N. Y.) 2022, 3, 100655. [CrossRef]

- Munchel, S.; Edwards, J.; Liao, H.; et al. Circulating Transcripts in Maternal Blood Reflect a Molecular Signature of Early-Onset Preeclampsia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaaz0131.

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. EdgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; Oshlack, A. A Scaling Normalization Method for Differential Expression Analysis of RNA-seq Data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R25. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, G.K. Limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor; Gentleman, R., Carey, V., Huber, W., et al., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 397–420.

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995, 57, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Tzur, T.; Sheiner, E.; Yanovich, L.; et al. Expanding Maternal Plasma Cell-Free RNA Analysis beyond the NIPT. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21253.

- Wedenoja, S.; Yoshihara, M.; Teder, H.; Sariola, H.; Gissler, M.; Katayama, S.; Wedenoja, J.; Häkkinen, I.M.; Ezer, S.; Linder, N.; et al. Fetal HLA-G Mediated Immune Tolerance and Interferon Response in Preeclampsia. EBioMedicine 2020, 59, 102872. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; et al. IL-25 Promotes Trophoblast Proliferation and Invasion via Binding with IL-17RB and Associated with PE. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2021, 40, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, H.; Meng, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Combined Maternal KIR2DL4 and Fetal HLA-G Polymorphisms Were Associated with Preeclampsia in a Han Chinese Population. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1442938. [CrossRef]

- Aisagbonhi, O.; Morris, G.P. Human Leukocyte Antigens in Pregnancy and Preeclampsia. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 884275. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).