Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Image Acquisition and Scene Set-Up

2.3. 3D Processing:

2.4. 3D Model Alignment and Export

2.5. 3D Annotation

2.6. Classification

2.7. Community Metrics

2.8. Structural Complexity Metrics

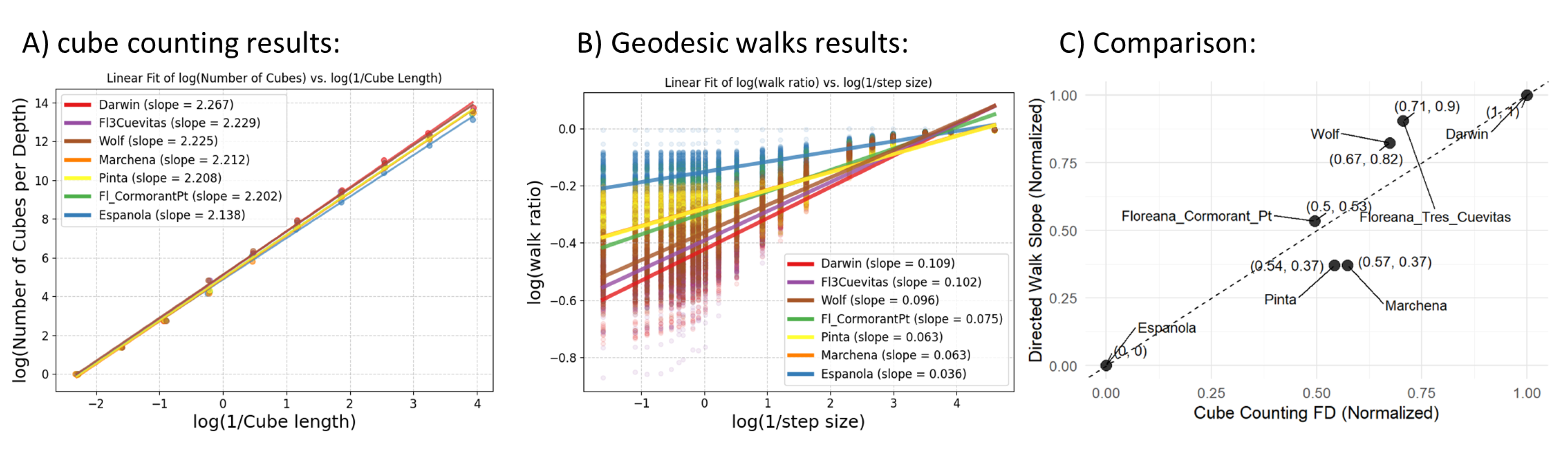

2.8.1. Fractal Dimension from Cube Counting

2.8.2. Fractal Dimension from Directed Geodesic Walks

3. Results

| site name | Caulerpa | DeadCoral-Framwork | DeadCoral-Rubble | Other | Pavona | Pocillopora | Porites | Rock | Sand | Tubastraea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darwin- Wellington Reef | 105 | 66 | 1 | 46 | 566 | 29 | 1108 | 855 | 177 | 9 |

| Española- Xarifa | 1 | 31 | 65 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 584 | 353 | 800 | 0 |

| Floreana- Tres Cuevitas | 0 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 731 | 1 | 0 | 1409 | 463 | 1 |

| Floreana-Punta Cormorant | 0 | 16 | 0 | 13 | 351 | 0 | 16 | 1317 | 485 | 1 |

| Marchena -Roca Espejo | 0 | 90 | 38 | 18 | 35 | 613 | 361 | 1063 | 265 | 1 |

| Pinta - Cabo Ibetson | 0 | 332 | 39 | 18 | 3 | 674 | 10 | 1423 | 64 | 0 |

| Wolf - Corales | 0 | 40 | 0 | 12 | 812 | 7 | 961 | 580 | 93 | 2 |

| Site name | Unknown | Psammocora | Cube Counting FD | mean_slope | lacunarity | SurfaceArea | Lat | Lon | Depth | |

| Darwin - Wellington Reef | 129 | 0 | 2.267 | 0.108951 | 1.495 | 309 | -91.995824 | 1.67824 | 15 | |

| Española - Xarifa | 8 | 1 | 2.138 | 0.035663 | 1.626 | 185 | -89.644622 | -1.357863 | 5 | |

| Floreana- Tres Cuevas | 130 | 8 | 2.229 | 0.101956 | 1.998 | 225 | -90.408089 | -1.236136 | 10 | |

| Floreana- Punta Cormorant | 51 | 1 | 2.202 | 0.074877 | 1.615 | 276 | -90.419325 | -1.223949 | 12 | |

| Marchena - Roca Espejo | 74 | 19 | 2.212 | 0.062882 | 1.458 | 258 | -90.401241 | 0.312162 | 8 | |

| Pinta - Cabo Ibetson | 71 | 18 | 2.208 | 0.062978 | 1.536 | 265 | -90.720945 | 0.544216 | 8 | |

| Wolf - Corales | 101 | 0 | 2.225 | 0.096196 | 1.684 | 261 | -91.815861 | 1.386624 | 12 |

3.1. Community Metrics from 3D Annotations

3.2. Multidimensional Scaling

3.3. Structural Complexity from Cube Counting and Walk Ratios

4. Discussion

- The authors used chatGPT and the Metashape online forum to generate the code and figures in the mansucript.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Principal Component Analysis | PCA |

| Fractal Dimension | FD |

References

- Izurieta, A.; Delgado, B.; Moity, N.; Calvopina, M.; Cedeno, Y.; Banda-Cruz, G.; Cruz, E.; Aguas, M.; Arroba, F.; Astudillo, I.; et al. A collaboratively derived environmental research agenda for Galápagos. Pacific Conservation Biology 2018, 24, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Wellington, G.M. Corals and coral reefs of the Galápagos Islands; Univ of California Press, 1983.

- Riegl, B.; Johnston, M.; Glynn, P.W.; Keith, I.; Rivera, F.; Vera-Zambrano, M.; Banks, S.; Feingold, J.; Glynn, P.J. Some environmental and biological determinants of coral richness, resilience and reef building in Galápagos (Ecuador). Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 10322. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, T.; Henderson, S.; Banks, S. Galapagos coral conservation: impact mitigation, mapping and monitoring. Galapagos Res 2009, 66, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman, A.D.; Duprey, N.N.; Yuval, M.; Dumestre, M.; Leichliter, J.N.; Rohr, M.C.; Dodwell, R.C.; Dodwell, G.A.; Clua, E.E.; Treibitz, T.; et al. Severe cold-water bleaching of a deep-water reef underscores future challenges for Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 951, 175210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman Jr, C.P. Evolutionary responses of marine invertebrates to insular isolation in Galapagos. Galapagos Research 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, G.J.; Banks, S.A.; Brandt, M.; Bustamante, R.H.; Chiriboga, A.; Earle, S.A.; Garske, L.E.; Glynn, P.W.; Grove, J.S.; Henderson, S.; et al. El Niño, grazers and fisheries interact to greatly elevate extinction risk for Galapagos marine species. Global Change Biology 2010, 16, 2876–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, P.W.; Feingold, J.S.; Baker, A.; Banks, S.; Baums, I.B.; Cole, J.; Colgan, M.W.; Fong, P.; Glynn, P.J.; Keith, I.; et al. State of corals and coral reefs of the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador): Past, present and future. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 133, 717–733. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Riegl, B.; Purkis, S.; Kerr, J.M.; Smith, T.B. Coral reef recovery in the Galápagos Islands: the northernmost islands (Darwin and Wenman). Coral Reefs 2015, 34, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, I.; Dawson, T.P.; Collins, K.J.; Campbell, M.L. Marine invasive species: establishing pathways, their presence and potential threats in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Pacific Conservation Biology 2016, 22, 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold, J.S.; Glynn, P.W. Coral research in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. In The Galápagos marine reserve: a dynamic social-ecological system; Springer, 2013; pp. 3–22.

- Glynn, P.W. State of coral reefs in the Galápagos Islands: natural vs anthropogenic impacts. Marine Pollution Bulletin 1994, 29, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, S.; Vera, M.; Chiriboga, A. Establishing reference points to assess long-term change in zooxanthellate coral communities of the northern Galápagos coral reefs. Galapagos Research 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.J.; Glynn, P.W.; Riegl, B. El Niño, echinoid bioerosion and recovery potential of an isolated Galápagos coral reef: a modeling perspective. Marine Biology 2017, 164, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, O.K.; Brandt, M.; Witman, J.D. La Niña-related coral death triggers biodiversity loss of associated communities in the Galápagos. Marine Ecology 2023, 44, e12767. [Google Scholar]

- Peñaherrera-Palma, C.; Harpp, K.; Banks, S. Rapid seafloor mapping of the northern Galapagos Islands, Darwin and Wolf. Galapagos Research 2016. [Google Scholar]

- López-Pérez, A.; Granja-Fernández, R.; Ramírez-Chávez, E.; Valencia-Méndez, O.; Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F.A.; González-Mendoza, T.; Martínez-Castro, A. Widespread Coral Bleaching and Mass Mortality of Reef-Building Corals in Southern Mexican Pacific Reefs Due to 2023 El Niño Warming. In Proceedings of the Oceans. MDPI. 2024; 5, 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.; Delparte, D.; Gates, R.; Takabayashi, M. Integrating structure-from-motion photogrammetry with geospatial software as a novel technique for quantifying 3D ecological characteristics of coral reefs. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1077. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, R.; Figueira, W.F.; Pratchett, M.S.; Boube, T.; Adam, A.; Kobelkowsky-Vidrio, T.; Doo, S.S.; Atwood, T.B.; Byrne, M. 3D photogrammetry quantifies growth and external erosion of individual coral colonies and skeletons. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 16737. [Google Scholar]

- Yuval, M.; Alonso, I.; Eyal, G.; Tchernov, D.; Loya, Y.; Murillo, A.C.; Treibitz, T. Repeatable semantic reef-mapping through photogrammetry and label-augmentation. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 659. [Google Scholar]

- Risk, M.J. Fish diversity on a coral reef in the Virgin Islands. Atoll research bulletin 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Loya, Y. Plotless and transect methods. Coral reefs: research methods. UNESCO, Paris 1978, pp. 197–217.

- Hill, J.; Wilkinson, C. Methods for ecological monitoring of coral reefs. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville 2004, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Laxton, J.; Stablum, W. Sample design for quantitative estimation of sedentary organisms of coral reefs. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 1974, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, B. Community patterns on a submerged barrier reef at Barbados, West Indies. Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie 1975, 60, 719–736. [Google Scholar]

- Remmers, T.; Grech, A.; Roelfsema, C.; Gordon, S.; Lechene, M.; Ferrari, R. Close-range underwater photogrammetry for coral reef ecology: a systematic literature review. Coral Reefs 2024, 43, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Luckhurst, B.; Luckhurst, K. Analysis of the influence of substrate variables on coral reef fish communities. Marine Biology 1978, 49, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.S.; Garrison, G.; Grober, R.; Hillis, Z.M.; Franke, M.A. Coral Reef Monitoring Manual for the Caribbean and Western Atlantic. Technical report, Virgin Islands National Park., 1994.

- Rogers, C.S.; Miller, J. Coral bleaching, hurricane damage, and benthic cover on coral reefs in St. John, US Virgin Islands: a comparison of surveys with the chain transect method and videography. Bulletin of Marine Science 2001, 69, 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Knudby, A.; LeDrew, E. Measuring Structural Complexity on Coral Reefs. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 26th Symposium, 2007; 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, M.; Ferrari, R.; Figueira, W.; Pizarro, O.; Madin, J.; Williams, S.; Byrne, M. Characterization of measurement errors using structure-from-motion and photogrammetry to measure marine habitat structural complexity. Ecology and Evolution 2017, 7, 5669–5681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.; Pizarro, O.; Williams, S.B.; Johnson-Roberson, M. Multi-scale measures of rugosity, slope and aspect from benthic stereo image reconstructions. PloS one 2012, 7, e50440. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, R.; McKinnon, D.; He, H.; Smith, R.N.; Corke, P.; González-Rivero, M.; Mumby, P.J.; Upcroft, B. Quantifying multiscale habitat structural complexity: a cost-effective framework for underwater 3D modelling. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 113. [Google Scholar]

- González-Rivero, M.; Harborne, A.R.; Herrera-Reveles, A.; Bozec, Y.M.; Rogers, A.; Friedman, A.; Ganase, A.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Linking fishes to multiple metrics of coral reef structural complexity using three-dimensional technology. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 13965. [Google Scholar]

- Hylkema, A.; Debrot, A.O.; Osinga, R.; Bron, P.S.; Heesink, D.B.; Izioka, A.K.; Reid, C.B.; Rippen, J.C.; Treibitz, T.; Yuval, M.; et al. Fish assemblages of three common artificial reef designs during early colonization. Ecological Engineering 2020, 157, 105994. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina-Barreto, I.; Chiroleu, F.; Pinel, R.; Fréchon, L.; Mahamadaly, V.; Elise, S.; Kulbicki, M.; Quod, J.P.; Dutrieux, E.; Garnier, R.; et al. Quantifying the shelter capacity of coral reefs using photogrammetric 3D modeling: From colonies to reefscapes. Ecological Indicators 2021, 121, 107151. [Google Scholar]

- Yuval, M.; Pearl, N.; Tchernov, D.; Martinez, S.; Loya, Y.; Bar-Massada, A.; Treibitz, T. Assessment of storm impact on coral reef structural complexity. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 891, 164493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aston, E.A.; Duce, S.; Hoey, A.S.; Ferrari, R. A Protocol for Extracting Structural Metrics From 3D Reconstructions of Corals. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 854395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Passoja, D.E.; Paullay, A.J. Fractal character of fracture surfaces of metals. Nature 1984, 308, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, K.L.; Graham, N.A.; Wilson, S.K.; Bellwood, D.R. Cross-scale habitat structure drives fish body size distributions on coral reefs. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.; Backes, A.R.; Schubert, P.; Wilke, T. The power of 3D fractal dimensions for comparative shape and structural complexity analyses of irregularly shaped organisms. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2017, 8, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga, A.; Burns, J.H. Metrics of coral reef structural complexity extracted from 3D mesh models and digital elevation models. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2676. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Pulliza, D.; Dornelas, M.A.; Pizarro, O.; Bewley, M.; Blowes, S.A.; Boutros, N.; Brambilla, V.; Chase, T.J.; Frank, G.; Friedman, A.; et al. A geometric basis for surface habitat complexity and biodiversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2020, 4, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.; Yadav, S.; Madin, J.S. The contribution of corals to reef structural complexity in Kāne ‘ohe Bay. Coral Reefs 2021, 40, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, O.S.; Smith, J.E.; Petrovic, V.; Sandin, S.A. Identifying the drivers of structural complexity on Hawaiian coral reefs. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2022, 702, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornder, N.A.; Cappelletto, J.; Mueller, B.; Zalm, M.J.; Martinez, S.J.; Vermeij, M.J.; Huisman, J.; de Goeij, J.M. Implications of 2D versus 3D surveys to measure the abundance and composition of benthic coral reef communities. Coral Reefs 2021, 40, 1137–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loya, Y. Community structure and species diversity of hermatypic corals at Eilat, Red Sea. Marine Biology 1972, 13, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R.; Lachs, L.; Pygas, D.R.; Humanes, A.; Sommer, B.; Figueira, W.F.; Edwards, A.J.; Bythell, J.C.; Guest, J.R. Photogrammetry as a tool to improve ecosystem restoration. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2021, 36, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Pavoni, G.; Corsini, M.; Callieri, M.; Palma, M.; Scopigno, R. SEMANTIC SEGMENTATION OF BENTHIC COMMUNITIES FROM ORTHO-MOSAIC MAPS. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing & Spatial Information Sciences, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pavoni, G.; Corsini, M.; Ponchio, F.; Muntoni, A.; Edwards, C.; Pedersen, N.; Sandin, S.; Cignoni, P. TagLab: AI-assisted annotation for the fast and accurate semantic segmentation of coral reef orthoimages. Journal of field robotics 2022, 39, 246–262. [Google Scholar]

- Remmers, T.; Boutros, N.; Wyatt, M.; Gordon, S.; Toor, M.; Roelfsema, C.; Fabricius, K.; Grech, A.; Lechene, M.; Ferrari, R. RapidBenthos: Automated segmentation and multi-view classification of coral reef communities from photogrammetric reconstruction. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, V.; Vanoni, D.J.; Richter, A.M.; Levy, T.E.; Kuester, F. Visualizing high resolution three-dimensional and two-dimensional data of cultural heritage sites. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 2014, 14, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pavoni, G.; Pierce, J.; Edwards, C.B.; Corsini, M.; Petrovic, V.; Cignoni, P. Integrating Widespread Coral Reef Monitoring Tools for Managing both Area and Point Annotations. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2024, 48, 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- King, A.; M Bhandarkar, S.; Hopkinson, B.M. Deep Learning for Semantic Segmentation of Coral Reef Images Using Multi-View Information. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2019, pp. 1–10.

- Pierce, J.; Butler IV, M.J.; Rzhanov, Y.; Lowell, K.; Dijkstra, J.A. Classifying 3-D models of coral reefs using structure-from-motion and multi-view semantic segmentation. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8, 706674. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, J.; Halpin, J.E.; Wilding, T.A. 3D photogrammetry and deep-learning deliver accurate estimates of epibenthic biomass. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2024, 15, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauder, J.; Banc-Prandi, G.; Meibom, A.; Tuia, D. Scalable semantic 3D mapping of coral reefs with deep learning. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2024, 15, 916–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Banks, S. Health status of the coral communities of the northern Galapagos Islands Darwin, Wolf and Marchena. Galapagos Res 2009, 66, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Park, J.; Koltun, V. Open3D: A Modern Library for 3D Data Processing. arXiv:1801.09847, 2018; arXiv:1801.09847. [Google Scholar]

- Labelbox. Online, 2025.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021.

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package, 2024. R package version 2.6-8.

- Schroeder, M. Fractals, Chaos, Power Laws: Minutes from an infinite paradise, 1991.

- Sullivan, C.B.; Kaszynski, A. PyVista: 3D plotting and mesh analysis through a streamlined interface for the Visualization Toolkit (VTK). Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, C.M.; Sweatman, H.P.; Brainard, R.E. The 2014–2017 global-scale coral bleaching event: insights and impacts. Coral Reefs 2019, 38, 539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, B.; Glynn, P.W.; Banks, S.; Keith, I.; Rivera, F.; Vera-Zambrano, M.; D’Angelo, C.; Wiedenmann, J. Heat attenuation and nutrient delivery by localized upwelling avoided coral bleaching mortality in northern Galapagos during 2015/2016 ENSO. Coral Reefs 2019, 38, 773–785. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, J.D.; Peixoto, R.S.; Davies, S.W.; Traylor-Knowles, N.; Short, M.L.; Cabral-Tena, R.A.; Burt, J.A.; Pessoa, I.; Banaszak, A.T.; Winters, R.S.; et al. The Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event: Where do we go from here? Coral Reefs 2024, pp. 1–5.

- NOAA. ENSO Diagnostic Discussion, 2024. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- Fox, M.D.; Carter, A.L.; Edwards, C.B.; Takeshita, Y.; Johnson, M.D.; Petrovic, V.; Amir, C.G.; Sala, E.; Sandin, S.A.; Smith, J.E. Limited coral mortality following acute thermal stress and widespread bleaching on Palmyra Atoll, central Pacific. Coral Reefs 2019, 38, 701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn, P.W.; Riegl, B.; Correa, A.; Baums, I.B. Rapid recovery of a coral reef at Darwin Island, Galapagos Islands. Galapagos Research 2009, 66, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Q.; Liang, Y.; Xiao, Y. Color-based segmentation of point clouds. Laser scanning 2009, 38, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

| Alignment Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | High |

| Generic preselection | Yes |

| Reference preselection | No |

| Key point limit | 40,000 |

| Key point limit per Mpx | 1,000 |

| Tie point limit | 4,000 |

| Exclude stationary tie points | Yes |

| Guided image matching | No |

| Adaptive camera model fitting | Yes |

| Depth Maps Generation Parameters | Values |

| Quality | High |

| Filtering mode | Mild |

| Reconstruction Parameters | Values |

| Surface type | Arbitrary |

| Source data | Depth maps |

| Interpolation | Enabled |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).