1. Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a particularly challenging pain syndrome that typically presents in patients that have received specific chemotherapeutic agents. Agents most commonly associated with peripheral neuropathy with their associated incidence rates include taxanes (eg, paclitaxel 60%-70%) platinums (eg, cisplatin 40%-70%), vinca alkaloids (eg, vincristine 20%), proteasome inhibitors (eg, bortezomib 40%-80%), and immunomodulatory agents (eg, thalidomide 60%) [

1]. The hallmark of CIPN is a gradually progressive, distal symmetrical sensory neuropathy that typically presents in a “stocking-glove” distribution and may be accompanied by reduced motor function. However, motor symptoms are often absent until the later stages of CIPN. It is also common for neuropathy to affect the feet without involving the hands. A temporal relationship exists between the onset of symptoms and the initiation, cessation, and duration of therapy. The pathophysiology of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) encompasses a range of mechanisms, with several key factors commonly proposed. These include disruption of axoplasmic microtubule-mediated transport, which leads to distal axonopathy and distal axonal degeneration; direct damage to the sensory nerve cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia; mitochondrial dysfunction; and the activation of protein kinases and extracellular kinases. Additionally, there is nerve cell death and a reduction in epidermal nerve fiber density with each treatment cycle, which is associated with decreased conduction velocity and amplitude. Other factors include alterations in gene expression related to pain mediation in the spinal cord dorsal horn and central sensitization resulting from long-term peripheral nerve injury [

2]. In regards to neuronal excitability, chemotherapeutic agents cause changes to peripheral nerve excitability that contribute to the development of sensory peripheral neuropathy. These are likely caused by altered expression and function of a range of ion channels—including voltage-gated sodium, voltage-gated potassium and transient receptor potential channels. Except for paclitaxel and oxaliplatin, which induce acute neuropathy that occurs either during or shortly after infusion, the onset of CIPN is typically delayed and tends to be influenced by the total cumulative dose. Some chemotherapeutic agents can lead to a phenomenon known as “coasting,” where symptoms of neuropathy continue to worsen or develop after the cessation of treatment. In severe instances, CIPN may result in an irreversible sensory neuron deficit [

3].

Clinically, CIPN manifests as deficits in sensory, motor, and autonomic function, with sensory symptoms typically appearing first in the feet and hands—reflecting the length of the axons, as longer neurites are affected initially. These symptoms can include numbness, tingling, paresthesias, and dysesthesias triggered by touch, temperature changes, as well as impaired vibration perception and altered touch sensations [

3]. Management revolves around prevention (dose delaying, dose reduction, stopping chemotherapy, or substituting with agents that do not cause CIPN) and treatment via pharmacologic therapy (eg. antiepileptics, antidepressants, analgesics). Neuromodulation for treatment of CIPN has been attempted including dorsal root ganglion stimulation (DRG-S), spinal cord stimulator (SCS) treatment, and peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS). According to one of the latest and largest systematic reviews on neuromodulation for CIPN, results have shown that there is very low-quality evidence supporting that dorsal column SCS, DRG-S, and PNS are associated with a reduction in pain severity from CIPN. Also, results on changes in neurological function are inconclusive [

4].

The PNS neuromodulation technique is effective for managing cancer pain itself. However, its impact on pain specifically caused by cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy- induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), is less significant. A retrospective review by Sudek showed that patients with tumor-related pain experienced meaningful relief from PNS, while those with CIPN or treatment-induced pain syndromes benefited the least from this therapy [

5]. A pilot study involving a case series of 12 patients who received a temporary 60-day peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) treatment for managing oncological pain suggested that PNS may have potential in treating cancer-related pain. However, 5 of the 12 patients did not experience relief from their symptoms. Among the 7 patients who did benefit, 3 cases involved the treatment of either lumbar radicular pain or truncal neuropathic pain. While the majority of patients (7 out of 12) experienced pain relief, the limited number of neuropathic pain cases prevents evidence-based conclusions and restricts the ability to generalize these findings regarding the effectiveness of PNS for neuropathic pain specifically [

6].

Additionally, PNS has shown strong clinical outcomes for a range of chronic pain conditions, beyond just oncological pain, achieving statistically significant reductions in pain scores across various target areas. However, the evidence supporting meaningful improvements in pain and neurological function after implantation for peripheral neuropathic conditions is limited [

7].

This case series further discusses peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) as a treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) and focuses on refining the procedural approach through optimization of lead placement relative to the location of symptomatic manifestations, and respectively assessing improvements in pain levels and neurological function in affected patients. The variation and comparison of target sites enables the assessment of whether distal or proximal stimulation leads to better clinical outcomes, highlighting that proper lead placement is essential for the effectiveness of PNS in CIPN and potentially other neuropathic conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This case series examined the use of peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) as a therapeutic intervention for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). The primary focus was on enhancing the procedural methodology by fine-tuning lead placement in relation to the symptomatic regions, alongside evaluating the impact of altering procedure approach on pain severity and neurological function.

2.2. Participants

A total of four patients were recruited from [anonymized] cancer center.

Table 1 presents the patients’ histories, demographics and characteristics of the cases.

The inclusion criteria included:

Adults aged 18 years or older.

A confirmed clinical diagnosis of CIPN, as determined by existing diagnostic criteria, including a reported history of chemotherapy treatment with onset of symptoms after exposure to a chemotherapeutic agent known to be neurotoxic. Presence of sensory disturbance and or painful symptoms in a symmetrical stocking and glove distribution beginning in lower extremities which may progress to the upper extremities. No other condition or polyneuropathy could account for the painful symptoms [

2].

A Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) score of 4 or higher, indicating moderate to severe pain severity.

The exclusion criteria included:

Previous surgeries involving the peripheral nerves.

Presence of uncontrolled systemic diseases or other neurological disorders.

Contraindications to PNS therapy including active infection at lead placement sites or allergies to materials used for the PNS.

2.3. PNS Procedure

Materials used include the SPR Sprint PNS system with a tined, flexible, coiled wire called MicroLead for the implantation with a MicroLead connector to attach to the external pulse generator (EPG). A OnePass was used as the introducer to advance with the percutaneous sleeve serving as the conduit for the MicroLead.

Following the acquisition of informed consent, patients were positioned for optimal comfort and positioning, and symptom localization was performed to identify target areas of pain and sensory disturbance. The placement of the stimulating lead was strategically selected according to the specific symptoms reported by each patient (all four patients symptomatic at the feet). The targeted areas of stimulation varied from proximal (eg. L5/S1 nerve roots to target dermatomes of ventral/dorsal foot up to ankles, femoral/sciatic nerve) to distal (eg. saphenous/popliteal nerve- midthigh) placement of leads.

Patients received PNS implantation under fluoroscopic guidance to accurately position the PNS lead adjacent to the intended nerve using the OnePass Introducer to advance with the percutaneous sleeve serving as the conduit for the MicroLead. Successful localization of lead placement was confirmed through electrical stimulation by eliciting muscle contraction or sensory response via connection to external pulse generator through MicroLead connectors. After confirming optimal positioning, the MicroLead was disconnected from the MicroLead connectors. The introducer/sleeve was retracted and lead was secured. The MicroLead was reconnected to the MicroLead connectors and excess lead was trimmed. The external pulse generator was connected after affixing the mounting cradle.

2.4. Postoperative Care

Following the procedure, patients received tailored settings for the electrical stimulation based on their immediate feedback and comfort levels. Follow-up was completed at 1-month intervals up to 3 months.

2.5. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the reduction in pain severity, assessed using the NRS pain scale at baseline, 1 month, 2 months, and 3 months post-implantation. The secondary outcomes focused on neurological function, evaluated using the TNAS (treatment induced neuropathy assessment scale) which were administered at the same intervals. Reduction in opioid usage was also monitored to assess efficacy of treatment.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The case series was reviewed and has received full IRB approval as per [anonymized] cancer center policy guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this case series for their participation and for the publication of their anonymized data. All patient data were handled in accordance with institutional policies on confidentiality and data protection.

3. Results

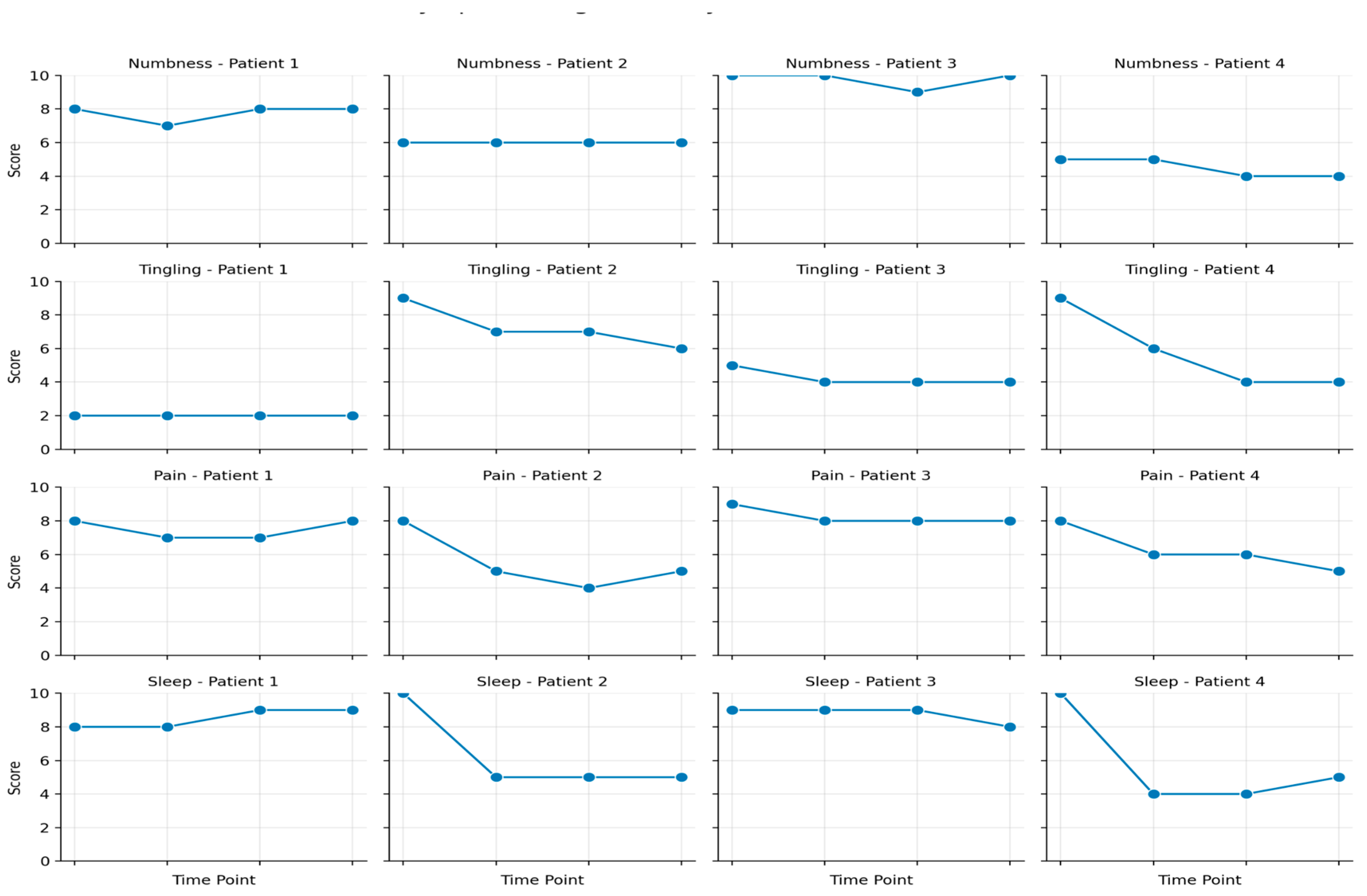

All four patients in this study experienced CIPN-related pain, measured using a VAS pain scale, while neuropathy was assessed using the TNAS (Treatment Induced Neuropathy Assessment Scale) (

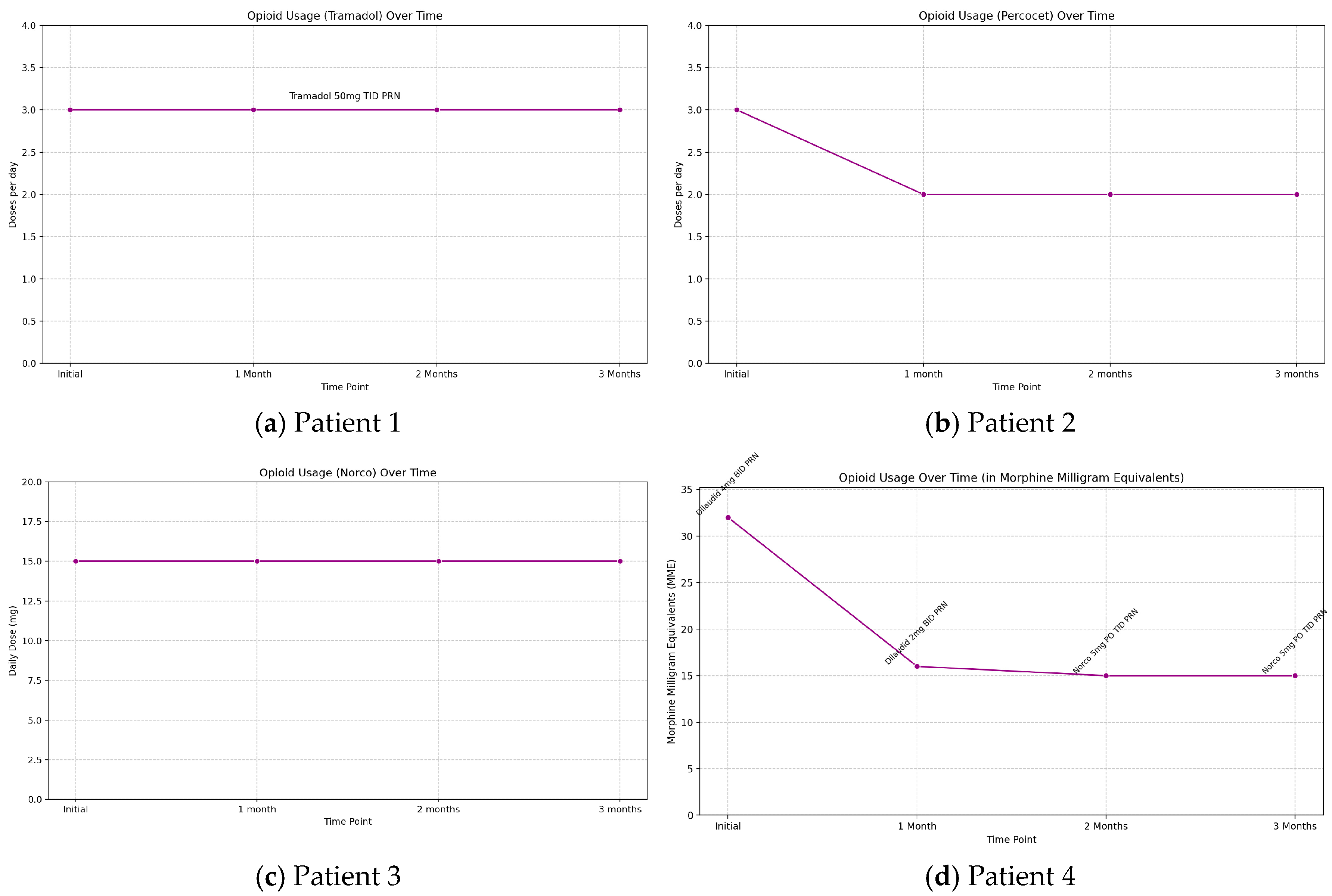

Figure 1). Throughout the three-month therapy, patients’ oral medication regimens were monitored. Patient 2 was able to decrease opioid use from TID to BID dosing as seen with the decrease in percocet use in

Figure 2b and patient 4 successfully transitioned from a strong opioid to a weak opioid (dilaudid to norco) with a significant decrease in MME requirements as seen in

Figure 2d, with further reduced overall oral medication intake over the three months for both patients. Of note, patients 2 and 4 had distal lead placement for peripheral nerve stimulation. Patient 1 and 3 showed no change in opioid requirement over the three months as tramadol and norco requirements stayed consistent, respectively (

Figure 2a,c).

The common site of pain for all patients was the bilateral dorsal and ventral feet up to the ankles, and stimulation targeted various areas based on the placement of electrode leads. Two patients received stimulation at distal target sites (saphenous/popliteal nerves at midthigh) closest to their symptoms, while one patient was targeted at the femoral and sciatic (subgluteal) nerves, and another at the most proximal site including the L5 and S1 nerve roots, furthest from the symptomatic area. The two patients with distal stimulation experienced the greatest pain reduction (patient 2: 30-40%; patient 4: 20-30% over three months). In contrast, the patient with proximal stimulation (L5 and S1) reported only about 10% relief initially, with no relief noted at the three-month follow-up. The patient with the femoral/ sciatic stimulation experienced 10% relief at both the one-month and three-month follow-ups (

Figure 1). Of note, the patient did have a complication where the PNS device dislodged and required reinsertion after one month.

The TNAS (Treatment-Induced Neuropathy Assessment Scale) that was used as another primary outcome measure is a useful tool for evaluating the severity and functional impact of peripheral neuropathy, particularly in individuals undergoing treatments that may induce neuropathy, such as chemotherapy or certain medications. It helps clinicians assess both the intensity of neuropathy-related symptoms and the degree to which these symptoms interfere with daily activities, providing a comprehensive picture of the condition’s effect on a patient’s quality of life. The scale measures five key symptoms—tingling, pain, numbness, hot or burning sensations, and coldness—in the arms, legs, hands, or feet, with each symptom scored from 0 to 10. A global symptom severity score is derived by averaging the scores, with higher values indicating worse symptom severity. Additionally, the TNAS includes an interference assessment that gauges the impact of neuropathy on activities such as using hands or fingers, walking, sleep, and balance. Higher interference scores reflect greater disruption to normal functioning. By assessing both the intensity of symptoms and their impact on daily functioning, the TNAS offers valuable insights that help guide treatment decisions and symptom management, making it an essential tool for clinicians tracking and managing treatment-induced neuropathy. In this study, neuropathy assessment on the TNAS scale showed minimal to no changes in nine symptoms for patients 1 and 3 over three months. However, patients 2 and 4 exhibited significant improvements in three symptoms—tingling, pain, and sleep—by the end of the study (

Figure 1). Patients 2 and 4 were the ones that received the most distal lead placement in proximity to the symptomatic site, in this case the feet.

4. Discussion

This case series assesses particularly the PNS neuromodulation system and its efficacy in treating CIPN. It is established that current evidence regarding the clinical outcomes of the PNS in managing pain related to CIPN is lacking. Large-scale studies examining various types of neuromodulation do not establish the superiority of PNS in treating CIPN. Instead, they generally highlight weak or statistically non-significant evidence supporting neuromodulation for managing pain associated with CIPN. A large-scale study conducted by D’Souza comprises a systematic review that assesses literature on the use of neuromodulation including DRG, SCS and PNS for treatment of pain associated with CIPN. The primary objective was to analyze the changes in pain intensity. The secondary objective was to assess changes in neurological function. In total, 23 articles were included with 73 participants that received DRG, SCS or PNS implantation. Only issue was that all included studies were case reports/series except for one retrospective observational study, which limited the sample size and power along with quality and strength of the data. In addition, the PNS sample size in the review was contributed from a single study, introducing bias. In conclusion, there was very low-quality evidence supporting neuromodulation, particularly PNS with a reduction in pain severity from CIPN [

4].

Furthermore, a credible evidence-based neuromodulatory intervention for treating CIPN has yet to be established. A most recently up to date published literature review on the DRG-S to treat CIPN yielded a total of 10 reports with 8 of them being case reports. The 1 retrospective study available on this topic describes nine patients who underwent DRG-S for CIPN. This study demonstrated significant reductions in pain scores after DRG-S trial and implantation with all patients endorsing improved sensation, 75% with decreased pain medication usage, and 37.5% reporting complete pain relief by 2 years. Despite its statistically significant reductions in pain scores and improvement in neurologic function, the small sample size of eight patients remained a large limitation [

8]. Overall, the literature review emphasizes that most of the reviewed publications, including the 8 case reports and 1 retrospective review of 9 cases are mostly animal studies, which may have limited relevance to human subjects. Although human dorsal root ganglia (DRG) exhibit similar immunoreactivities for pain-related molecules as those in laboratory animals, there are notable differences in factors such as neuronal size, electrophysiology, and the expression of channel proteins and receptors. These discrepancies, along with the absence of subjective feedback (e.g., pain scoring), underscore the urgent need for more clinical research focused on human responses. Not to mention that most published studies are limited by their sample sizes as they are case reports rather than large scale-studies [

9].

With respect to PNS neuromodulatory technique for treatment of CIPN, quality data is lacking. The one limited retrospective review on PNS for CIPN includes Sacco et al. studying a form of PNS called percutaneous auricular neurostimulation (PANS) therapy which stimulates peripheral nerves in the ear. In the study, 18 patients that had pre and post pain scores available for quantitative analyses reported pain VAS scores that significantly decreased after PANS therapy (mean VAS score pre-treatment- 8.11 vs. post-treatment- 3.17; p < 0.001), regardless of the number of treatments. 59% of patients with qualitative data reported marked improvements and 12.5% reported notable but minimal reduction in pain and numbness following treatment [

7]. The study validates the PNS as an effective CIPN treatment device but given it is a specific type of PNS and targets just a single area (one placement at the auricular area) for all patients with no specification of target site of CIPN it is addressing, it is not clear how auricular nerve stimulation helps to alleviate CIPN- related pain that usually presents in a stocking-glove distribution in the distal extremities. There was no lead placement in proximity or at site of the CIPN such as the lower extremity peripheral nerves, questioning the mechanism and efficacy of treatment [

10].

The PNS has demonstrated success in treating chronic pain (≥3 months), achieving an average pain reduction of 34% (pre-procedure VAS score of 6.4 and post-procedure score of 4.2). A retrospective review indicated that outcomes varied widely among patients with different chronic pain syndromes that were stimulated at varying targeted nerve sites with respect to their diagnosis and location of pain. The respective mean VAS pain score improvement and mean percent improvement was categorized per diagnosis/targeted nerve. Some conditions showed minimal improvement—especially neuropathic pain conditions such as diabetic neuropathy and lumbar neuropathy, although certain isolated neuropathies did achieve over 50% improvement [

11]. Following enumeration and comparing the data on the chronic pain conditions and the target nerves with their respective pain scores/percent improvement, it was found that the study was inconclusive as it was difficult to state that PNS is an effective intervention for all chronic pain conditions related to neuropathic pain despite some of the neuropathic conditions showing positive response to the PNS. The inconclusiveness regarding PNS’s effectiveness for neuropathic pain syndromes suggests further exploration into optimizing procedural techniques, such as lead placement, to enhance clinical outcomes in these specific conditions.

The mechanism of action of the PNS itself is effectively explained by the gate control theory, as the neuromodulation targets and activates non-nociceptive (A-beta large diameter) fibers which then activate inhibitory interneurons that inhibit the transmission of pain signals carried by C and A-delta fibers at the spinal cord level where the two types of fibers converge. The therapy works to effectively close the gate to pain signals entering the central nervous system, thereby lessening the perception of pain. Distal stimulation (optimizing lead placement of PNS) can apply this theory more effectively by activating non-nociceptive fibers while avoiding the interference introduced by convergence of various sensory signals at proximal sites, making targeted pain modulation less challenging.

The theory that distal stimulation may be superior to proximal stimulation in the context of PNS for pain management relates closely to how afferent signals converge and the physiological dynamics of pain modulation. At proximal sites (those nearer to the central nervous system), there is often a higher degree of convergence among sensory afferent pathways. This convergence can bring together a variety of sensory signals, including nociceptive and non-nociceptive inputs, onto the same neurons. When stimulation occurs at these proximal locations, it can activate a wider range of signals, making it difficult to achieve selective and effective modulation of pain. In contrast, distal stimulation typically targets specific nerve fibers, allowing for greater precision in modulating sensory input. By activating neurons farther from the CNS, distal stimulation can bypass areas of convergence and selectively engage the desired pathways. This targeted activation can enhance the inhibition of nociceptive signaling while avoiding the more complex pathways found at proximal sites.

Other approaches to selectively activate desired pathways including A-beta fibers (large-diameter fibers) and engage the gating mechanism have been explored, as highlighted in a narrative review by Deer. Larger-diameter nerve fibers are more readily activated by electrical stimulation at lower intensities compared to smaller fibers. By carefully adjusting stimulation intensities, it is possible to selectively activate large-diameter Aα/β fibers while minimizing the activation of smaller nociceptive fibers to engage the gating mechanism. Neuromodulation techniques like PNS offer the potential for more focal and targeted stimulation of the Aα/β fibers, specifically targeting the nerves or ganglia that innervate the pain region. Conventional PNS uses small electrodes placed close to the nerve, generating intense electric fields that dissipate quickly, activating fibers near the electrode (including small-diameter fibers) while sparing those further away. In contrast to the “intimate” conventional electrode placement, percutaneous PNS systems designed to enable remote selective targeting with open-coiled leads are placed farther from the nerve (remote), allowing more focused stimulation to selectively activate Aα/β fibers and avoid Aδ/C fibers. This approach optimizes the relationship between stimulation strength, electrode characteristics, fiber diameter, and electrode-fiber distance (typically 0.5–3 cm) to enhance the activation of large-diameter fibers while minimizing the activation of small-diameter fibers [

12]. By fine-tuning these factors, remote selective targeting may improve the effectiveness of PNS by selectively stimulating larger fibers and reducing unwanted discomfort associated with smaller fibers. The concept of selective activation and focused targeting to optimally stimulate Aα/β fibers with a remote percutaneous PNS system aligns closely with the goal of optimizing lead placement, as both approaches are designed to maximize the clinical effectiveness of PNS therapy.

The underlying mechanisms of CIPN and other chronic polyneuropathies that lead to peripheral neuropathic pain (PNP) share similarities. These mechanisms of PNP can be categorized into effects on dorsal root ganglion neurons, axons, and the myelin sheath or Schwann cells. The pathogenesis is multifaceted, involving endothelial dysfunction, impaired Schwann cell activity, capillary issues, disruption of the blood-nerve barrier, apoptosis, increased oxidative stress, direct toxic effects, mitochondrial DNA damage, loss of neurofilament polymers, and disrupted axonal transport and microtubule function, alterations in gene expression related to pain mediation in the spinal cord dorsal horn, and central sensitization resulting from long-term peripheral nerve injury. In chronic painful polyneuropathy, potential molecular mechanisms contributing to neuronal hyperexcitability and persistent sensory neuron activity may include changes in the expression of ion channels and receptors, heightened levels of reactive metabolites like methylglyoxal, altered neurotransmitter release, inflammatory factors, and the influence of genetic variants in sodium channel genes. Additionally, human studies indicate that patients with painful polyneuropathy exhibit alterations in spinal pain modulation systems and changes in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray, along with modifications in brain connectivity and structure [

13]. However, further research is needed to clarify how specific these changes are to pain and their potential causal roles in the pain’s pathophysiology.

Peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) presents a valuable intervention for managing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) and other forms of peripheral neuropathic pain (PNP) characterized by neuronal hyperexcitability, persistent sensory neuron activity, and central sensitization. The efficacy of PNS is grounded in its alignment with the gate control theory, which facilitates pain modulation through the activation of large fibers and inhibitory neurons, effectively blocking nociceptive transmission from small fibers. Furthermore, PNS mechanisms involve stimulation-induced blockade of cell membrane depolarization, reducing C-fiber excitation and suppressing dorsal horn activity. This alleviates hyperexcitability and long-term potentiation of dorsal horn neurons associated with conditions like CIPN. Effectively managing damaged dorsal root ganglia, which contribute to hyperexcitability and pain mediation, is crucial and can be addressed through the mechanisms of PNS [

7]. Timing is an important consideration; early intervention during the onset of neuropathic symptoms in chemotherapy patients—who often experience symptoms early in treatment—may help prevent the progression of central sensitization, ultimately improving outcomes and enhancing quality of life for those affected.

This case series emphasizes that a change in procedure or clinical treatment approach by addressing the placement of stimulation of the PNS electrode leads has an effect on outcomes (pain scores and neuropathy scores), specifically more distal placement that is in proximity to the site of pain due to CIPN. The 2 patients with saphenous nerve/popliteal nerve stimulation (patient 2 and patient 4) experienced the most distal stimulation in closest proximity to the site of symptoms which for all patients were the feet. They also experienced the greatest analgesia with patient 2 having 30-40% pain relief and patient 4 experiencing 20-30% relief over 3 months. In addition, both patients with distal lead placements were able to reduce opioid use as patient 2 had reduction in daily dosing frequency of norco and patient 4 was able to transition to a weaker opioid with MME requirements that significantly decreased followed by stabilization (dilaudid to percocet and switch from lyrica to duloxetine). Patient 3 with a femoral/sciatic target site only had 10% pain relief at one and three-month follow-up. The most proximal stimulation was the L5/S1 nerve root level where 10% relief was reported at one-month but by three months 0% relief was sustained. It is clear that more distal stimulation, particularly near the target site—specifically, saphenous and popliteal nerve stimulation at the mid-thigh level relative to the symptomatic site in the feet—resulted in a greater percentage of pain relief and improved clinical outcomes, along with a reduced need for opioids. In contrast, proximal stimulation provided significantly less pain relief and showed no change in opioid requirements by the three-month follow-up.While Medicare guidelines suggest that at least 50% pain relief is required during a successful trial implant before considering any form of permanent implantation, the purpose of this study was to conduct a comparative analysis aimed at optimizing lead placements. The analysis sought to determine whether clinical outcomes, including pain scores and quantitative neurological function values, improved after optimizing lead placement, rather than simply evaluating absolute values of pain scores.

From a neurological function standpoint, patient 2 and patient 4 achieved the greatest results in neuropathy assessment with improvement in tingling, pain and sleep (>35% in each symptom). The other 2 patients had minimal to no improvement in their TNAS from baseline from zero to three month follow up. These results show preliminary evidence that lead placement for PNS in a more distal approach and in close proximity to the site of symptoms may play a large role in the percent of analgesia achieved and functional improvement in other neuropathic symptoms, further validating the efficacy of the PNS in treatment of CIPN. It is proposed that closer placement may enhance the modulation of pain pathways as PNS works by delivering electrical impulses that can interrupt or inhibit pain signals traveling to the brain. If placed strategically, PNS may provide more localized stimulation, leading to better symptom relief.

Not only is there a limited amount of research validating PNS for the treatment of CIPN and the advantages of optimizing lead placement for better outcomes, but there is also a deficiency of quality data concerning other neuropathic conditions. In particular, PNS has garnered interest as a potential treatment for diabetic neuropathy (DN), but research in this area remains limited and inconclusive. Current studies evaluating the efficacy of PNS in treating diabetic neuropathy consist primarily of small sample sizes, which limits the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the quality is limited by inadequate randomization, poor blinding, and limited follow-up periods. In regards to procedure approach, there is preliminary evidence surrounding the optimization of lead placement for PNS in diabetic neuropathy that is still emerging. Some low-quality studies suggest that the precise placement of PNS leads may improve treatment outcomes, but these findings require further validation through controlled and designed research settings. Given that CIPN and DN have a similar underlying pathophysiology as they both present with distal axonopathy and symmetrical length-dependent sensory neuropathy in a stocking-glove distribution [

14], their analogous suboptimal responses to the same treatment with the PNS can be attributed to this comparable underlying mechanism of disease. This case series indicates that optimization of lead placement during PNS implantation, particularly when positioned closer to the symptomatic site, results in better clinical outcomes for CIPN. This concept could theoretically extend to diabetic neuropathy (DN) due to their shared underlying pathophysiology. This suggests further studies on more effective lead placement for the PNS for treatment of various other neuropathic pain conditions where PNS has been shown to be less effective compared to other chronic pain disorders.

From a neurophysiological perspective, conducting a nerve conduction study and examining neurophysiological changes—such as nerve latency, amplitude, and conduction velocity—across different nerves while modifying lead placement from proximal to distal can help assess the significance of lead optimization for treating a target site. By detecting patterns and physiological changes as the placement is adjusted, this approach offers scientifically-based evidence that highlights the importance of optimizing placement in PNS therapy for the effective treatment of CIPN.

Although the case series offers valuable preliminary evidence, it comes with certain limitations that should be taken into account. The small sample size and the absence of a control group may limit the generalizability of the findings, necessitating the need for larger-scale prospective studies to validate the results. Additionally, the small sample size inherent in this case series could introduce selection bias.