Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

29 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

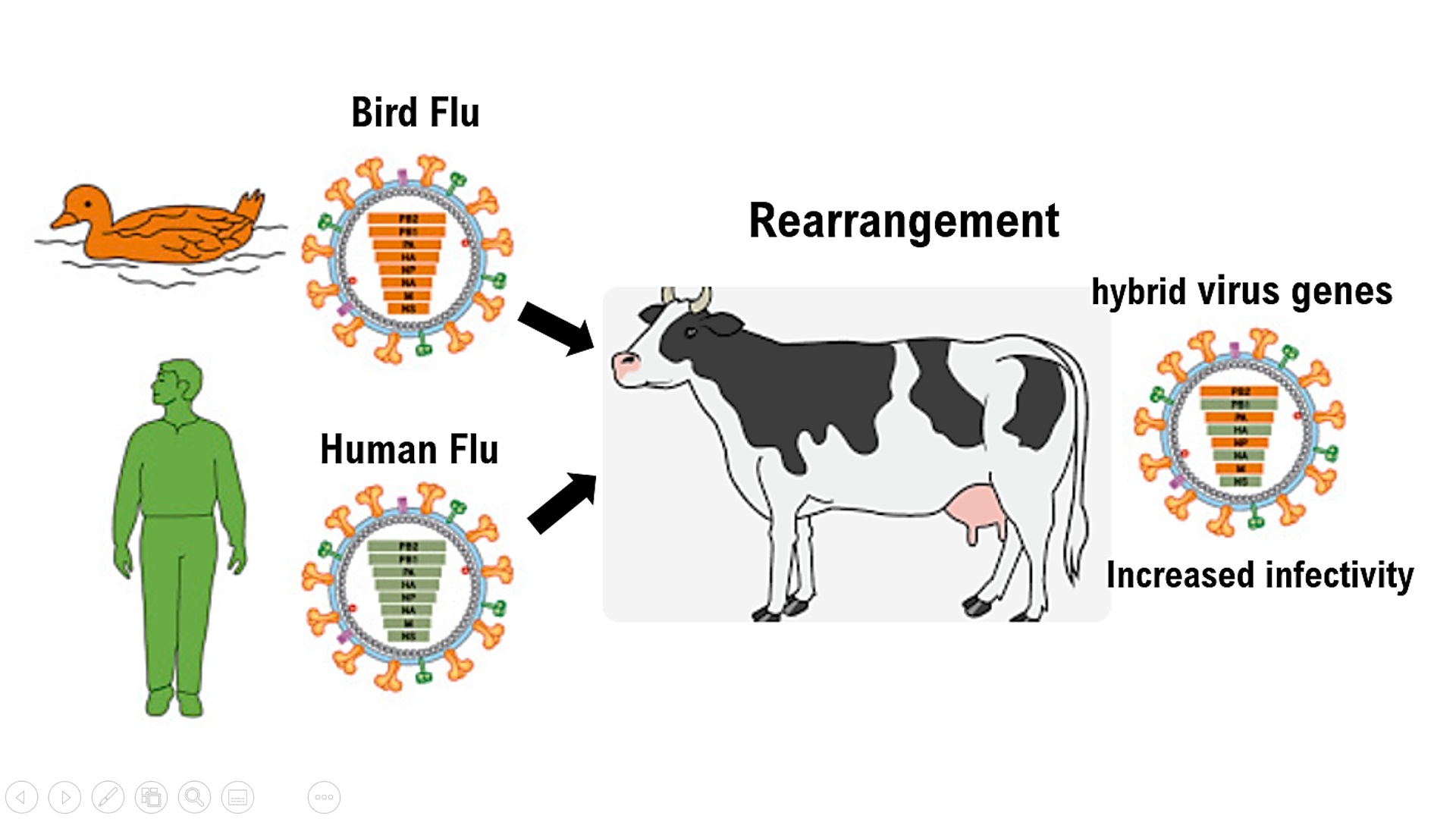

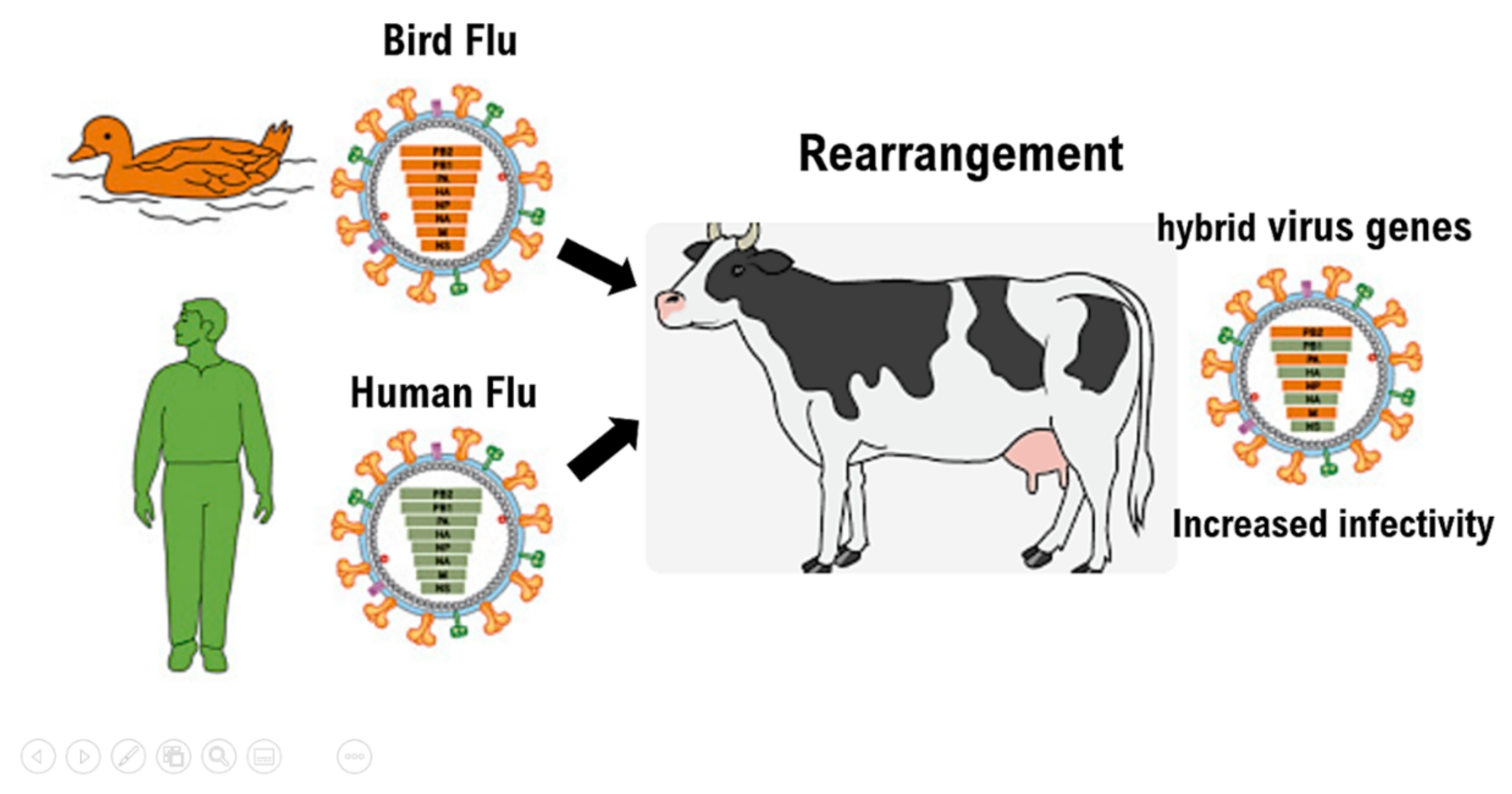

The 5H1N Virus That Infects Dairy Cows Genetically Modifies in the Living Dairy Cow, Increasing Its Infectivity to Humans

Hygiene Management of LBM Is Important to Prevent the Spread of Zoonotic Diseases

Author contribution

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- S. Chowdhury, M.E. Hossain, P.K. Ghosh, S. Ghosh, M.B. Hossain, C. Beard, M. Rahman, M.Z. Rahman, The pattern of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 outbreaks in South Asia, Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. (2019). [CrossRef]

- L.O. Durand, P. Glew, D. Gross, M. Kasper, S. Trock, I.K. Kim, J.S. Bresee, R. Donis, T.M. Uyeki, M.A. Widdowson, E. Azziz-Baumgartner, Timing of influenza a(H5n1) in poultry and humans and seasonal influenza activity worldwide, 2004–2013, Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21 (2015) 202–208. [CrossRef]

- D.U. Pfeiffer, M.J. Otte, D. Roland-Holst, D. Zilberman, A one health perspective on HPAI H5N1 in the Greater Mekong sub-region, Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36 (2013) 309–319. [CrossRef]

- S.L. Letsholo, J. James, S.M. Meyer, A.M.P. Byrne, S.M. Reid, T.B.K. Settypalli, S. Datta, L. Oarabile, O. Kemolatlhe, K.T. Pebe, B.R. Mafonko, T.J. Kgotlele, K. Kumile, B. Modise, C. Thanda, J.F.C. Nyange, C. Marobela-Raborokgwe, G. Cattoli, C.E. Lamien, I.H. Brown, W.G. Dundon, A.C. Banyard, Emergence of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza Virus H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b in Wild Birds and Poultry in Botswana, Viruses 14 (2022). [CrossRef]

- N. Moyen, M.A. Hoque, R. Mahmud, M. Hasan, S. Sarkar, P.K. Biswas, H. Mehedi, J. Henning, P. Mangtani, M.S. Flora, M. Rahman, N.C. Debnath, M. Giasuddin, T. Barnett, D.U. Pfeiffer, G. Fournié, Avian influenza transmission risk along live poultry trading networks in Bangladesh, Sci. Rep. 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- G. Fournié, J. Guitian, S. Desvaux, P. Mangtani, S. Ly, V.C. Cong, S. San, D.H. Dung, D. Holl, D.U. Pfeiffer, S. Vong, A.C. Ghani, Identifying live bird markets with the potential to act as reservoirs of avian influenza a (H5N1) virus: A survey in Northern Viet Nam and Cambodia, PLoS One 7 (2012). [CrossRef]

- R. Indriani, G. Samaan, A. Gultom, L. Loth, S. Irianti, R. Adjid, N.L.P.I. Dharmayanti, J. Weaver, E. Mumford, K. Lokuge, P.M. Kelly, Darminto, Environmental sampling for avian influenza virus a (H5N1) in live-bird markets, Indonesia, Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16 (2010) 1889–1895. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Coker, B.M. Hunter, J.W. Rudge, M. Liverani, P. Hanvoravongchai, Emerging infectious diseases in southeast Asia: Regional challenges to control, Lancet 377 (2011) 599–609. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Rimi, M.Z. Hassan, S. Chowdhury, M. Rahman, R. Sultana, P.K. Biswas, N.C. Debnath, S.K.S. Islam, A.G. Ross, A decade of avian influenza in Bangladesh: Where are we now?, Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 4 (2019). [CrossRef]

- A. Islam, M.Z. Rahman, M.M. Hassan, J.H. Epstein, M. Klaassen, Determinants for the presence of avian influenza virus in live bird markets in Bangladesh: Towards an easy fix of a looming one health issue, One Heal. 17 (2023). [CrossRef]

- F. Pinotti, L. Kohnle, J. Lourenço, S. Gupta, M.A. Hoque, R. Mahmud, P. Biswas, D. Pfeiffer, G. Fournié, Modelling the transmission dynamics of H9N2 avian influenza viruses in a live bird market, Nat. Commun. 15 (2024) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- R.G. Webster, Wet markets - A continuing source of severe acute respiratory syndrome and influenza?, Lancet 363 (2004) 234–236. [CrossRef]

- G.F. Gao, Influenza and the live poultry trade, Science (80-.). 344 (2014) 235. [CrossRef]

- X.-F. Wan, L. Dong, Y. Lan, L.-P. Long, C. Xu, S. Zou, Z. Li, L. Wen, Z. Cai, W. Wang, X. Li, F. Yuan, H. Sui, Y. Zhang, J. Dong, S. Sun, Y. Gao, M. Wang, T. Bai, L. Yang, D. Li, W. Yang, H. Yu, S. Wang, Z. Feng, Y. Wang, Y. Guo, R.J. Webby, Y. Shu, Indications that Live Poultry Markets Are a Major Source of Human H5N1 Influenza Virus Infection in China, J. Virol. 85 (2011) 13432–13438. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, J.T. Wu, B.J. Cowling, Q. Liao, V.J. Fang, S. Zhou, P. Wu, H. Zhou, E.H.Y. Lau, D. Guo, M.Y. Ni, Z. Peng, L. Feng, H. Jiang, H. Luo, Q. Li, Z. Feng, Y. Wang, W. Yang, G.M. Leung, Effect of closure of live poultry markets on poultry-to-person transmission of avian influenza A H7N9 virus: An ecological study, Lancet 383 (2014) 541–548. [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Connie Leung, E.H.Y. Lau, L.J. Zhang, Y. Guan, B.J. Cowling, J.S.M. Peiris, Avian influenza and ban on overnight poultry storage in live poultry markets, Hong Kong, Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18 (2012) 1339–1341. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guan, B.J. Zheng, Y.Q. He, X.L. Liu, Z.X. Zhuang, C.L. Cheung, S.W. Luo, P.H. Li, L.J. Zhang, Y.J. Guan, K.M. Butt, K.L. Wong, K.W. Chan, W. Lim, K.F. Shortridge, K.Y. Yuen, J.S.M. Peiris, L.L.M. Poon, Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China, Science (80-.). (2003). [CrossRef]

- G. Fournié, F.J. Guitian, P. Mangtani, A.C. Ghani, Impact of the implementation of rest days in live bird markets on the dynamics of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza, J. R. Soc. Interface 8 (2011) 1079–1089. [CrossRef]

- J.C.M. Turner, M.M. Feeroz, M.K. Hasan, S. Akhtar, D. Walker, P. Seiler, S. Barman, J. Franks, L. Jones-Engel, P. McKenzie, S. Krauss, R.J. Webby, G. Kayali, R.G. Webster, Insight into live bird markets of Bangladesh: An overview of the dynamics of transmission of H5N1 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses, Emerg. Microbes Infect. 6 (2017). [CrossRef]

- N.J. Negovetich, M.M. Feeroz, L. Jones-Engel, D. Walker, S.M.R. Alam, K. Hasan, P. Seiler, A. Ferguson, K. Friedman, S. Barman, J. Franks, J. Turner, S. Krauss, R.J. Webby, R.G. Webster, Live bird markets of bangladesh: H9n2 viruses and the near absence of highly pathogenic h5n1 influenza, PLoS One 6 (2011). [CrossRef]

- P.K. Biswas, M. Giasuddin, B.K. Nath, M.Z. Islam, N.C. Debnath, M. Yamage, Biosecurity and Circulation of Influenza A (H5N1) Virus in Live-Bird Markets in Bangladesh, 2012, Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 64 (2017) 883–891. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, K. Subbarao, N.J. Cox, Y. Guo, Genetic characterization of the pathogenic influenza A/Goose/Guangdong/1/96 (H5N1) virus: Similarity of its hemagglutinin gene to those of H5N1 viruses from the 1997 outbreaks in Hong Kong, Virology 261 (1999) 15–19. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guan, M. Peiris, K.F. Kong, K.C. Dyrting, T.M. Ellis, T. Sit, L.J. Zhang, K.F. Shortridge, H5N1 influenza viruses isolated from geese in southeastern China: Evidence for genetic reassortment and interspecies transmission to ducks, Virology 292 (2002) 16–23. [CrossRef]

- H.M. Kang, E.K. Lee, B.M. Song, J. Jeong, J.G. Choi, J. Jeong, O.K. Moon, H. Yoon, Y. Cho, Y.M. Kang, H.S. Lee, Y.J. Lee, Novel reassortant influenza a(H5N8) viruses among inoculated domestic and wild ducks, South Korea, 2014, Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21 (2015) 298–304. [CrossRef]

- P. Huang, L. Sun, J. Li, Q. Wu, N. Rezaei, S. Jiang, C. Pan, Potential cross-species transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 subtype (HPAI H5) viruses to humans calls for the development of H5-specific and universal influenza vaccines, Cell Discov. (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Jeong, H.M. Kang, E.K. Lee, B.M. Song, Y.K. Kwon, H.R. Kim, K.S. Choi, J.Y. Kim, H.J. Lee, O.K. Moon, W. Jeong, J. Choi, J.H. Baek, Y.S. Joo, Y.H. Park, H.S. Lee, Y.J. Lee, Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N8) in domestic poultry and its relationship with migratory birds in South Korea during 2014, Vet. Microbiol. 173 (2014) 249–257. [CrossRef]

- ECDC, First identification of human cases of avian influenza A (H5N8) infection, (2021). https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/First-identification-human-cases-avian-influenza-A-H5N8-infection.pdf.

- J. Chen, J. Zhang, W. Zhu, Y. Zhang, H. Tan, M. Liu, M. Cai, J. Shen, H. Ly, J. Chen, First genome report and analysis of chicken H7N9 influenza viruses with poly-basic amino acids insertion in the hemagglutinin cleavage site, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).