Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

29 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

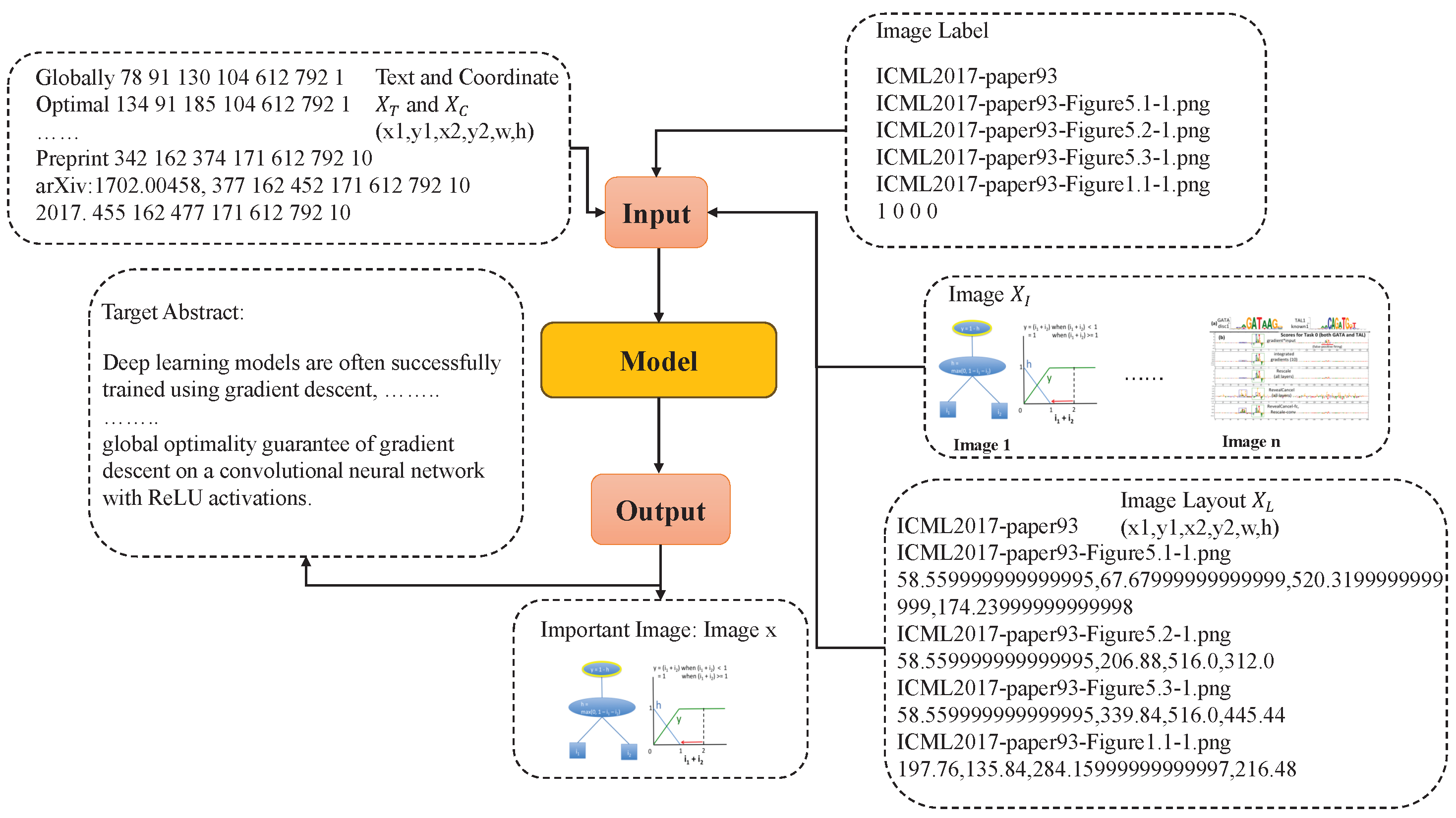

1. Introduction

- We present a novel deep multimodal-interactive network that generates the abstract of a research paper while simultaneously selecting its most representative image. This approach facilitates a deeper understanding of the research content. By integrating both textual and visual modalities that convey complementary information at different semantic levels through a combination module, our multimodal learning framework enables researchers to access paper information beyond the constraints of text alone, thereby advancing scientific research.

- A structural information enhancement module that incorporates the spatial arrangement and layout of textual and visual elements is proposed. This module enhances the semantic understanding of the paper’s structure by generating informative and meaningful summaries that include both the abstract and the most significant image.

- A new multimodal dataset that incorporates structural information is constructed to facilitate the evaluation process. This dataset overcomes the limitations of most existing summarization datasets, which typically only contain text and images for training and validation.

- Extensive experiments demonstrate the superior summarization capabilities of the proposed multimodal learning network, as evidenced by several key performance indicators. Additionally, the proposed model supports image-text cross-modal retrieval applications, showcasing its strong capabilities and significant potential in handling multimodal learning tasks, especially in the future smart city information management systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Document Summarization

2.2. Multimodal Summarization Techniques

3. Methodology

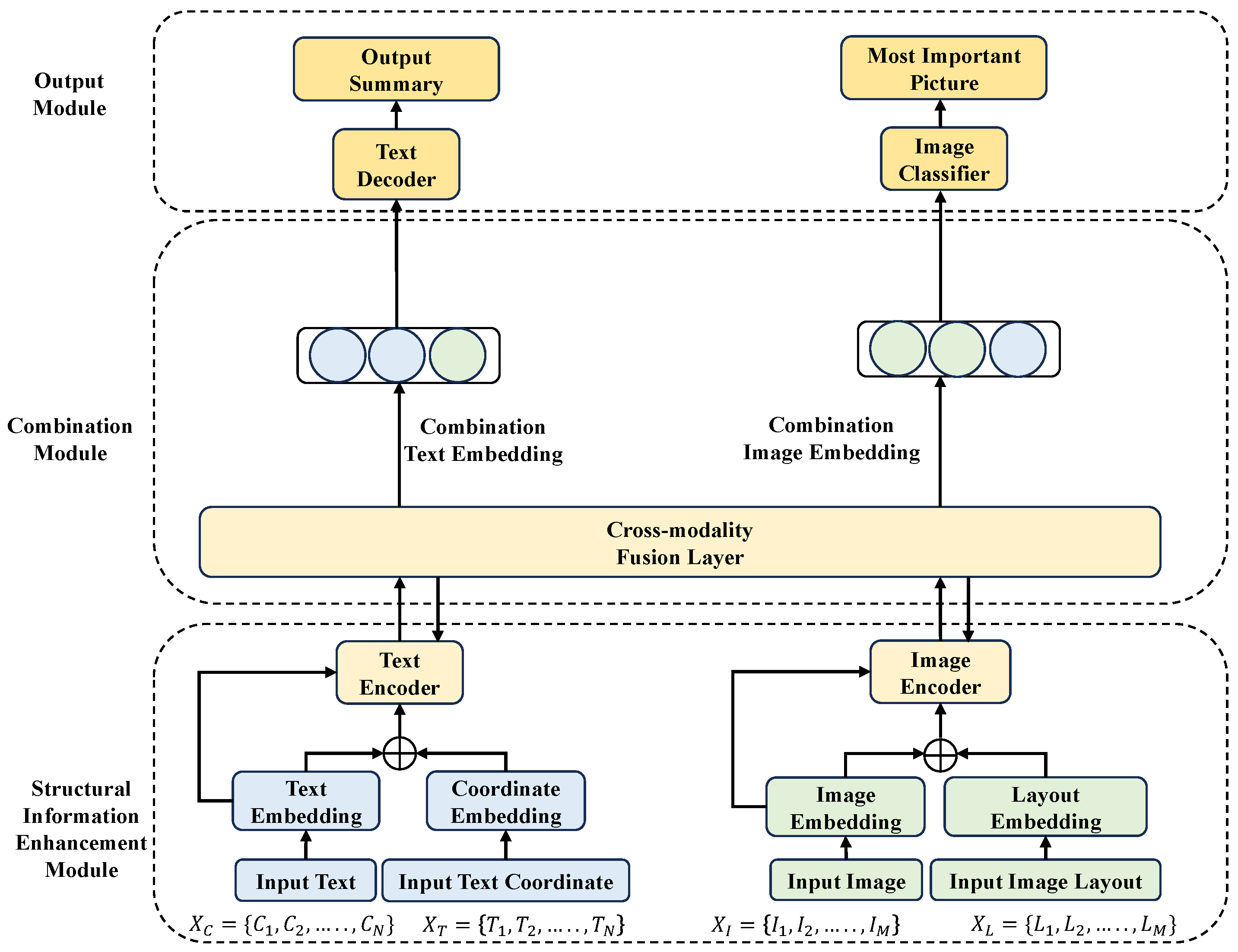

3.1. Overall Framework

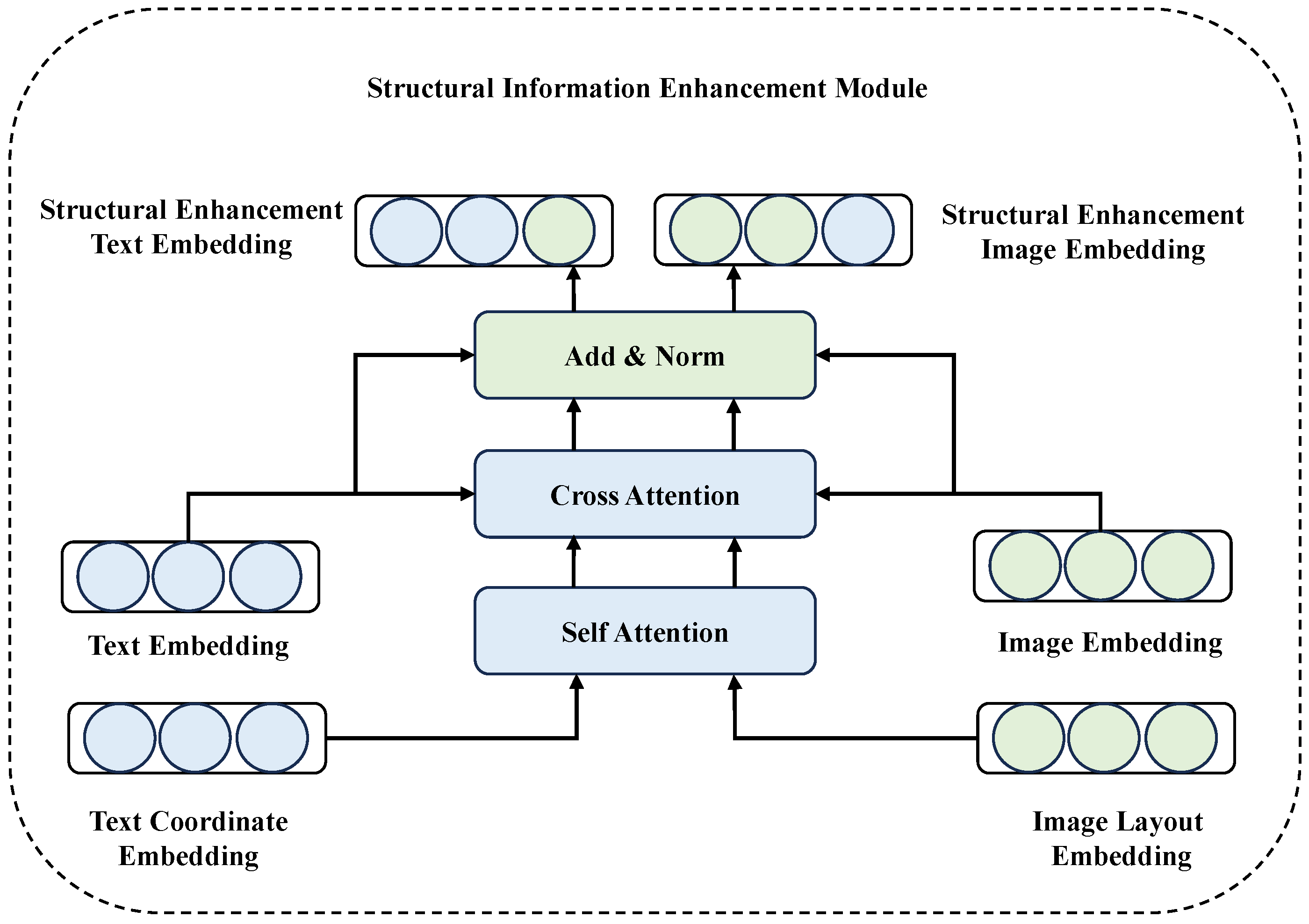

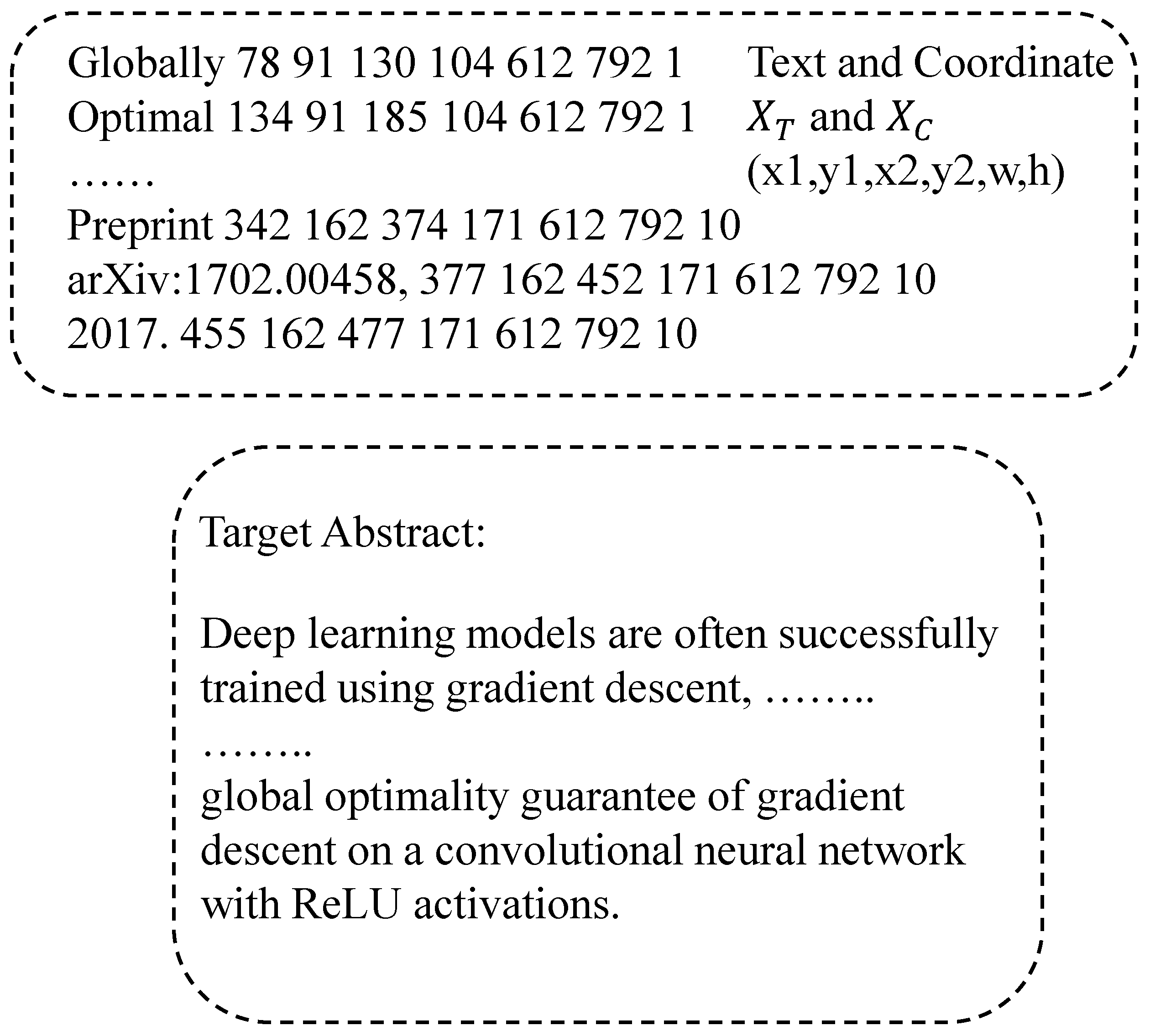

3.2. Structural Information Enhancement Module

3.2.1. Structural Embedding Layer

3.2.2. Image Enhancement

3.2.3. Text Enhancement

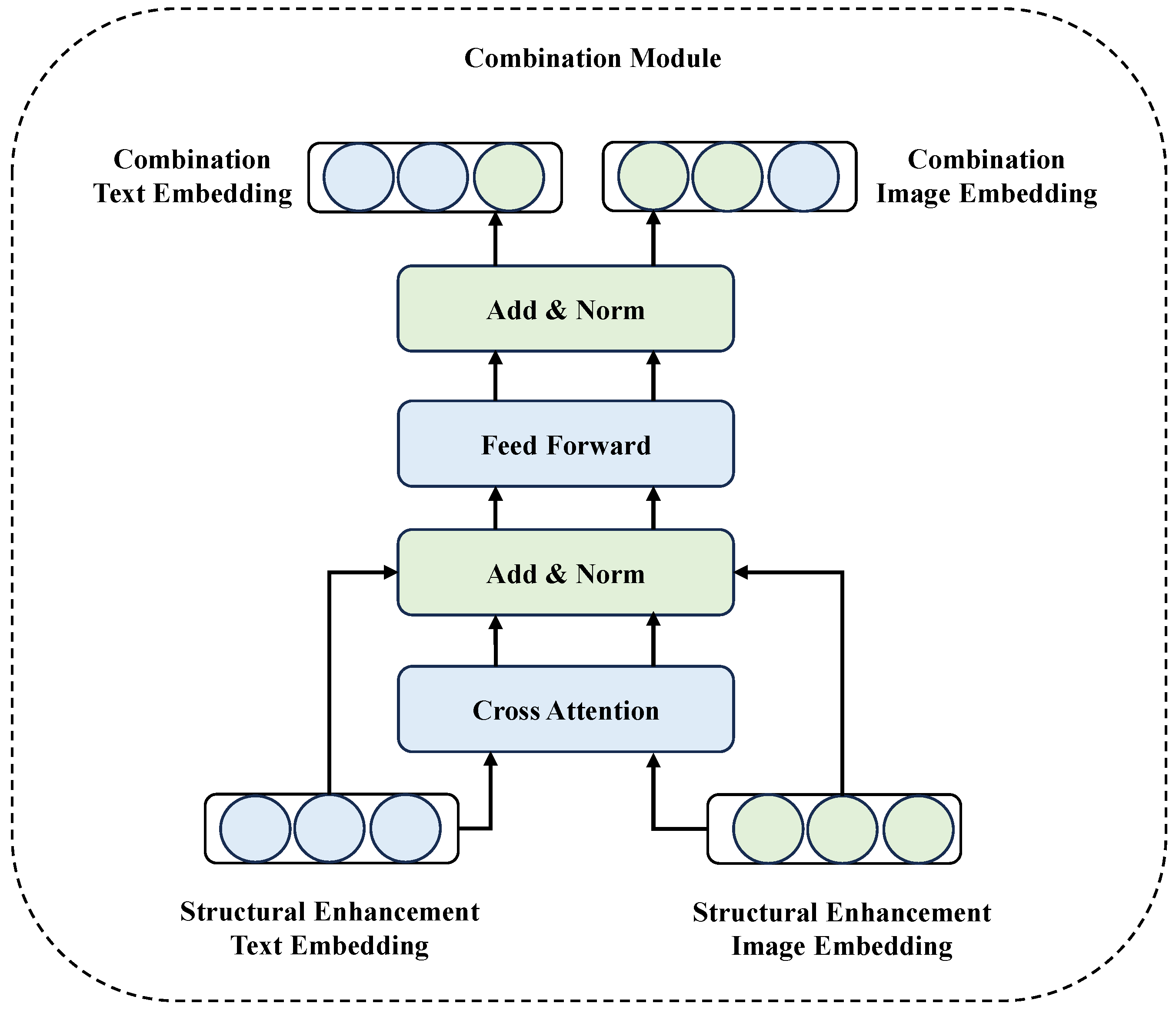

3.3. Combination Module

3.3.1. Image-to-Text Combination

3.3.2. Text-to-Image Combination

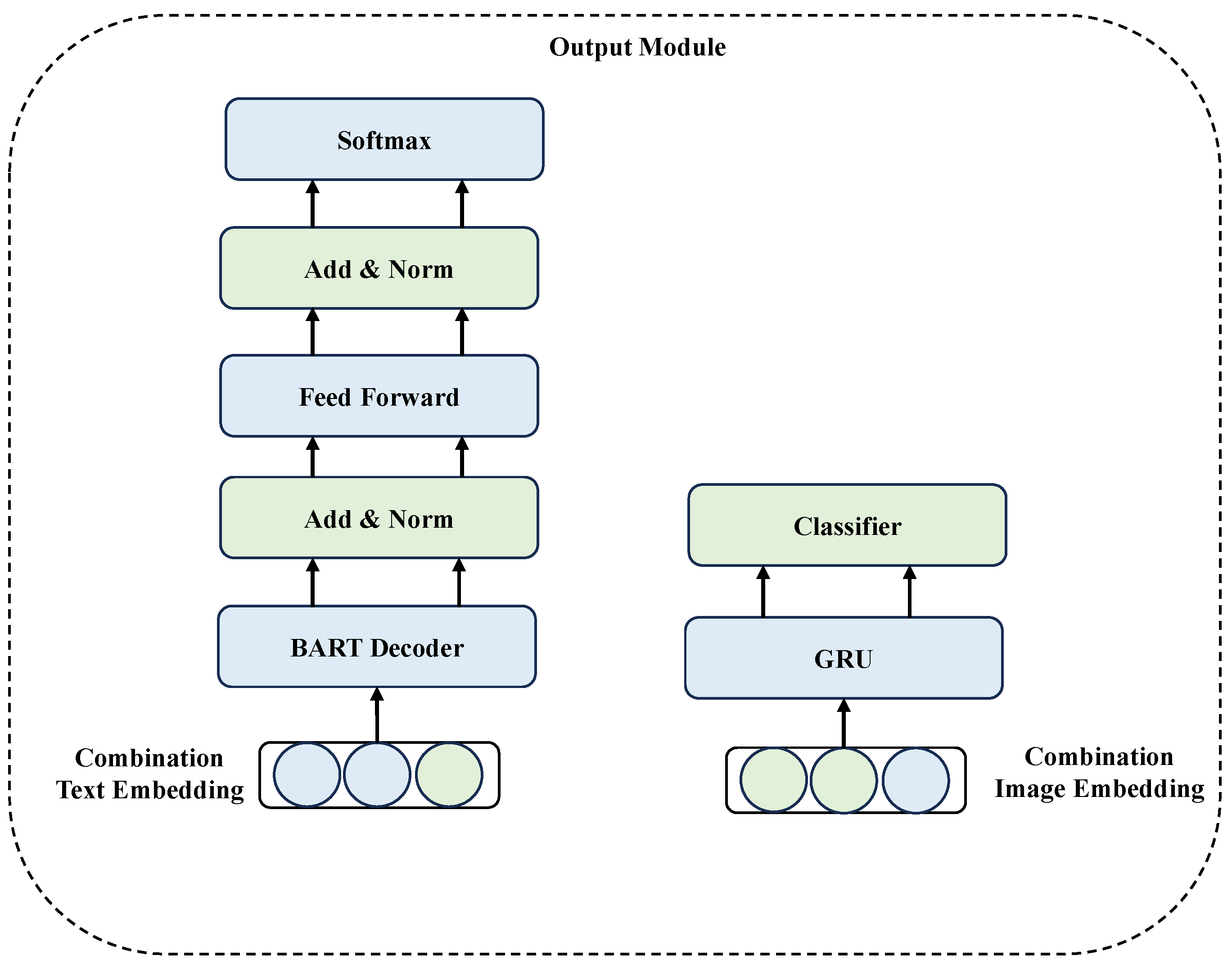

3.4. Output Module

3.4.1. Paper Abstract Generation

3.4.2. The Most Important Image Selection

3.5. Total Loss Function

4. Experiment and Result

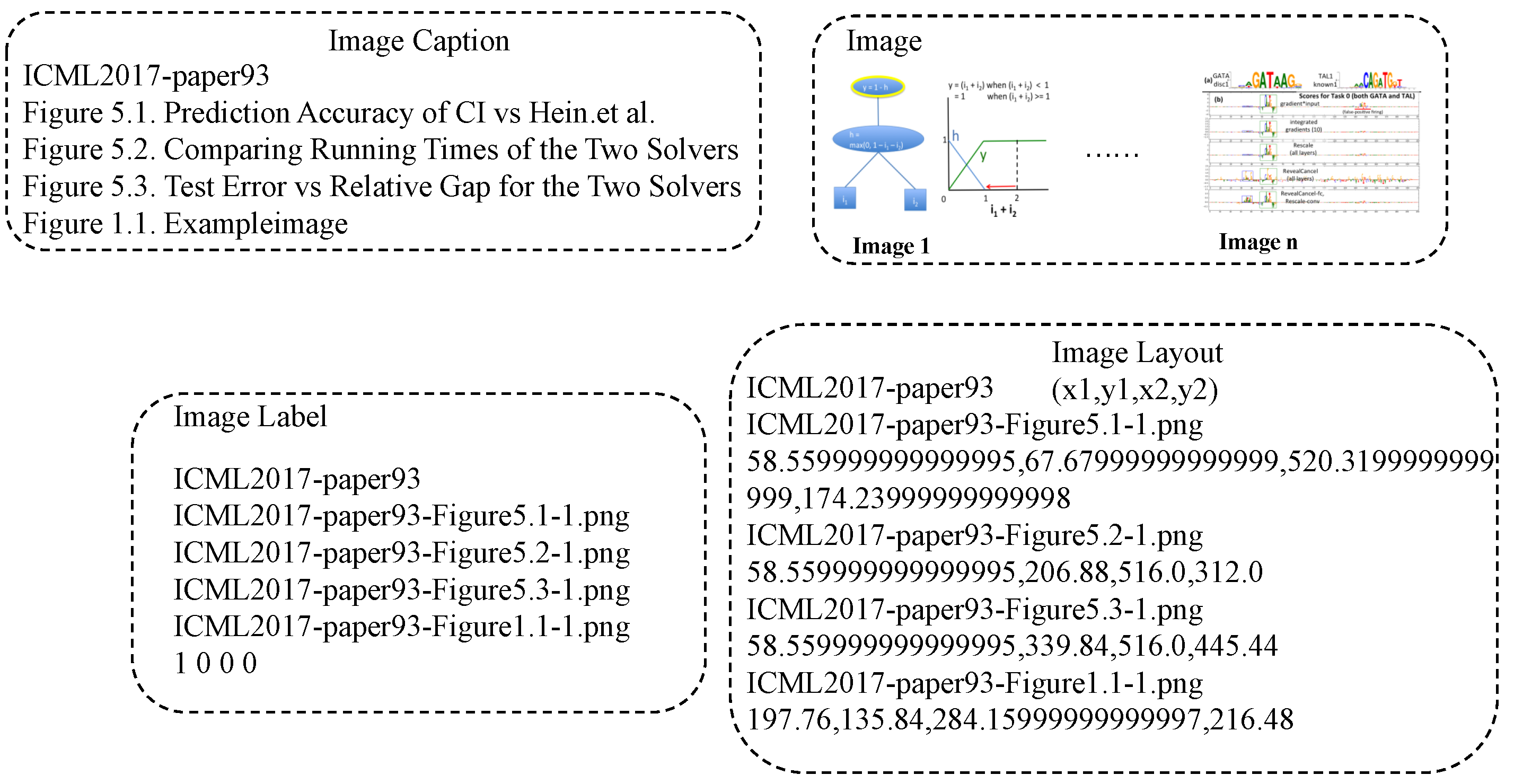

4.1. Dataset Detail

4.2. Implementation Detail

4.3. Baseline Model

- Lead-3: Lead-3 is a simple yet widely used baseline model that selects the first three sentences of a document as the summary. It is based on the assumption that the most important information is often located at the beginning of a text.

- SumBasic: SumBasic is a sentence extraction algorithm that relies on basic features such as sentence length, position, and the presence of capital words. It assigns scores to sentences based on these features and selects the top-ranked sentences to form the summary.

- TF-IDF: TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) identifies important words in a document by calculating their frequency and their rarity across a corpus. The model then extracts sentences containing these high-weight words to form the summary.

- TextRank: TextRank treats sentences as nodes in a graph and computes their importance based on their similarity to other sentences. It iteratively ranks sentences and selects the top-ranked ones to generate the summary.

- LexRank: LexRank is an improved version of TextRank that uses a more efficient algorithm to compute sentence importance. It also focuses on maintaining semantic similarity between sentences to produce coherent summaries.

- T5: T5 is a versatile and powerful model designed for various text-based tasks, including text summarization. It leverages a pre-training approach on a wide range of text-to-text tasks and has shown remarkable performance in generating concise and coherent summaries.

- MBart: MBart is a multilingual pre-trained model optimized for text summarization and machine translation. Its ability to handle multiple languages makes it particularly suitable for cross-lingual summarization tasks, providing robust performance across diverse datasets.

- LED: LED is a model specifically designed for document summarization, focusing on generating informative and concise summaries. It employs a lightweight approach to editing and compression, making it efficient for handling long texts.

- Pegasus: Pegasus is a model developed for abstractive summarization tasks. It utilizes a novel pre-training strategy that incorporates extracted summarization guidance, enabling it to generate high-quality, human-like summaries.

- DistilBART: DistilBART is a lightweight and efficient variant of the BART model, designed to reduce computational resources while maintaining high performance. It is particularly useful for scenarios where resource constraints are a concern.

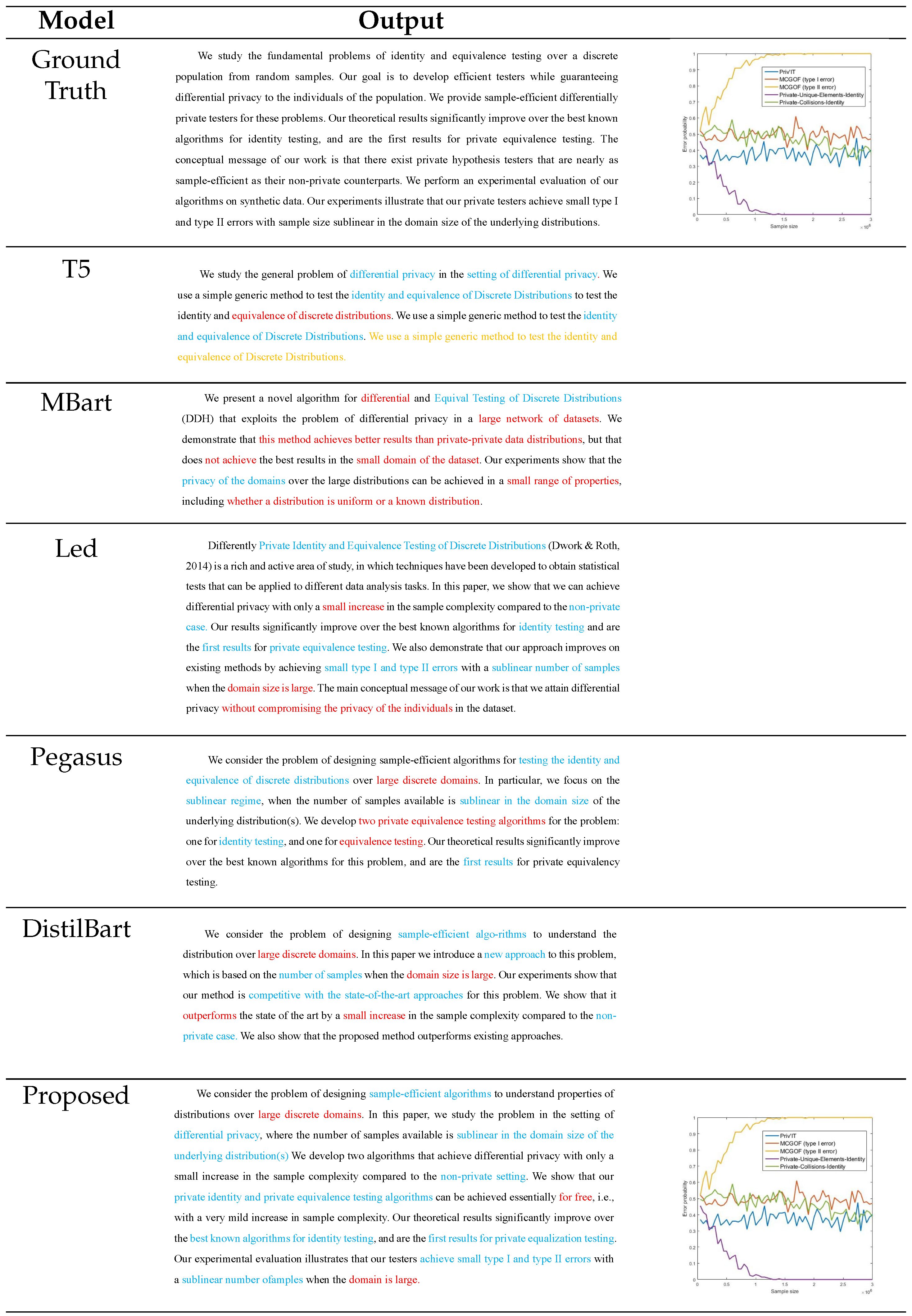

4.4. Comparison Result

4.5. Visualization Result

4.6. Ablation Study

4.7. Cross-Modal Retrieval Application

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transportation Engineering 2024, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kim, H.; Hancke, G.P. Environmental monitoring systems: A review. IEEE Sensors Journal 2012, 13, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarashynskaya, A.; Prus, P. Smart Energy for a Smart City: A Review of Polish Urban Development Plans. Energies 2022, 15, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM transactions on intelligent systems and technology 2024, 15, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkirov, A. Artificial Intelligence impact on higher education quality and efficiency. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Su, S. Multimodal Learning for Automatic Summarization: A Survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Data Mining and Applications. Springer; 2023; pp. 362–376. [Google Scholar]

- Altmami, N.I.; Menai, M.E.B. Automatic summarization of scientific articles: A survey. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Yin, W.; Meng, L.; Sigal, L. Layout2image: Image generation from layout. International journal of computer vision 2020, 128, 2418–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Han, J.; Ding, G.; Sun, J. Repvgg: Making vgg-style convnets great again. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 13733–13742.

- Haralick. Document image understanding: Geometric and logical layout. In Proceedings of the 1994 Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE, 1994, pp. 385–390.

- Hendges, G.R.; Florek, C.S. The graphical abstract as a new genre in the promotion of science. In Science communication on the internet; John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2019; pp. 59–80.

- Ye, X.; Chaomurilige.; Liu, Z.; Luo, H.; Dong, J.; Luo, Y. Multimodal Summarization with Modality-Aware Fusion and Summarization Ranking. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing. Springer, 2024, pp. 146–164.

- Ramathulasi, T.; Kumaran, U.; Lokesh, K. A survey on text-based topic summarization techniques. In Advanced Practical Approaches to Web Mining Techniques and Application; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2022; pp. 1–13.

- Zhang, H.; Yu, P.S.; Zhang, J. A systematic survey of text summarization: From statistical methods to large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.11289 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, G.; Sun, X.; Hu, P.; Liu, Y. Attention-Based Multi-Kernelized and Boundary-Aware Network for image semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 2024, 597, 127988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Liang, X.; Wu, S.; Li, Z. Align vision-language semantics by multi-task learning for multi-modal summarization. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 15653–15666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Han, J. Part-object relational visual saliency. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwaar, M.U.; Labintcev, E.; Kleinsteuber, M. Compositional learning of image-text query for image retrieval. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 1140–1149.

- Wu, G.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Liu, L.; Ding, G.; Zhang, B.; Shen, J. Unsupervised Deep Hashing via Binary Latent Factor Models for Large-scale Cross-modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, 2018, Vol. 1, p. 5.

- Chen, C.; Debattista, K.; Han, J. Virtual Category Learning: A Semi-Supervised Learning Method for Dense Prediction with Extremely Limited Labels. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (T-PAMI) 2024.

- Henderson, P.; Ferrari, V. End-to-end training of object class detectors for mean average precision. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ACCV 2016: 13th Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, November 20-24, 2016, Revised Selected Papers, Part V 13. Springer, 2017, pp. 198–213.

- Yigitcanlar, T. Smart cities: An effective urban development and management model? Australian Planner 2015, 52, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Leng, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y. Fusiontransnet for smart urban mobility: Spatiotemporal traffic forecasting through multimodal network integration. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.05786 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dzemydienė, D.; Burinskienė, A.; Čižiūnienė, K. An approach of integration of contextual data in e-service system for management of multimodal cargo transportation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, N.; Bhushan, B. Demystifying the role of natural language processing (NLP) in smart city applications: background, motivation, recent advances, and future research directions. Wireless personal communications 2023, 130, 857–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. Natural language processing in urban planning: A research agenda. Journal of Planning Literature 2024, 39, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshamwala, A.; Mishra, D.; Pawar, P. Review on natural language processing. IRACST Engineering Science and Technology: An International Journal (ESTIJ) 2013, 3, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wibawa, A.P.; Kurniawan, F.; et al. A survey of text summarization: Techniques, evaluation and challenges. Natural Language Processing Journal 2024, 7, 100070. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.; Scialom, T.; Piwowarski, B.; Staiano, J. LoRaLay: A multilingual and multimodal dataset for long range and layout-aware summarization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.11312 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Backer Johnsen, H. Graphical abstract?-Reflections on visual summaries of scientific research. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, F.K. Verbal and visual resources in graphical abstracts: Analyzing patterns of knowledge presentation in digital genres. Ibérica: Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos (AELFE) 2023, pp. 129–154.

- Jambor, H.K.; Bornhäuser, M. Ten simple rules for designing graphical abstracts. PLOS Computational Biology 2024, 20, e1011789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givchi, A.; Ramezani, R.; Baraani-Dastjerdi, A. Graph-based abstractive biomedical text summarization. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, 132, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangra, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Jatowt, A.; Saha, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M. A survey on multi-modal summarization. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Ji, H.; Radke, R.J. Keep meeting summaries on topic: Abstractive multi-modal meeting summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics, 2019, pp. 2190–2196.

- Bhatia, N.; Jaiswal, A. Automatic text summarization and it’s methods-a review. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th international conference-cloud system and big data engineering (Confluence). IEEE, 2016, pp. 65–72.

- Chen, Z.; Lu, Z.; Rong, H.; Zhao, C.; Xu, F. Multi-modal anchor adaptation learning for multi-modal summarization. Neurocomputing 2024, 570, 127144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Zhang, W.E.; Xie, L.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Sheng, Q. Automatic, meta and human evaluation for multimodal summarization with multimodal output. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, pp. 7768–7790.

- Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, J.; Zong, C. Multi-modal summarization for asynchronous collection of text, image, audio and video. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2017, pp. 1092–1102.

- Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Zong, C.; et al. Multi-modal Sentence Summarization with Modality Attention and Image Filtering. In Proceedings of the IJCAI; 2018; pp. 4152–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Zhu, J.; Lin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zong, C. Cfsum: A coarse-to-fine contribution network for multimodal summarization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.02716 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. A modality-enhanced multi-channel attention network for multi-modal dialogue summarization. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Zong, C. Multimodal sentence summarization via multimodal selective encoding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 5655–5667.

- Yuan, M.; Cui, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Liu, T. Exploring the Trade-Off within Visual Information for MultiModal Sentence Summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2024, pp. 2006–2017.

- Im, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, H.; Cho, H.; Chung, S. Self-supervised multimodal opinion summarization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.13135 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Jing, L.; Lin, D.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Nie, L. V2P: Vision-to-prompt based multi-modal product summary generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, 2022, pp. 992–1001.

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z. MDS: A Fine-Grained Dataset for Multi-Modal Dialogue Summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), 2024, pp. 11123–11137.

- Zhang, J.G.; Zou, P.; Li, Z.; Wan, Y.; Pan, X.; Gong, Y.; Yu, P.S. Multi-modal generative adversarial network for short product title generation in mobile e-commerce. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.01735 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhuge, H. Abstractive text-image summarization using multi-modal attentional hierarchical RNN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2018, pp. 4046–4056.

- Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Multi-modal summarization for video-containing documents. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.08018 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zong, C. MSMO: Multimodal summarization with multimodal output. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2018, pp. 4154–4164.

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zong, C.; Li, C. Multimodal summarization with guidance of multimodal reference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 9749–9756.

- Tan, Z.; Zhong, X.; Ji, J.Y.; Jiang, W.; Chiu, B. Enhancing Large Language Models for Scientific Multimodal Summarization with Multimodal Output. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Industry Track, 2025, pp. 263–275.

- Zhu, J.; Xiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zong, C. Graph-based multimodal ranking models for multimodal summarization. Transactions on Asian and low-resource language information processing 2021, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Z. Unims: A unified framework for multimodal summarization with knowledge distillation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 11757–11764.

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Pan, J. Hierarchical cross-modality semantic correlation learning model for multimodal summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 11676–11684.

- Mukherjee, S.; Jangra, A.; Saha, S.; Jatowt, A. Topic-aware multimodal summarization. In Proceedings of the Findings of the association for computational linguistics: AACL-IJCNLP 2022, 2022, pp. 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Mm-avs: A full-scale dataset for multi-modal summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 2021, pp. 5922–5926.

- Jin, X.; Liu, K.; Jiang, J.; Xu, T.; Ding, Z.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Xue, K.; et al. Pattern recognition of distributed optical fiber vibration sensors based on resnet 152. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 19717–19725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.13461 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. An overview of multi-task learning. National Science Review 2018, 5, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th international midwest symposium on circuits and systems (MWSCAS). IEEE; 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Jiang, X.; Shatkay, H. Figure and caption extraction from biomedical documents. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4381–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, H.; Patel, N.; Jani, D. Fine-tuning BART for abstractive reviews summarization. In Computational Intelligence: Select Proceedings of InCITe 2022; Springer, 2023; pp. 375–385.

- Zhang, Z. Improved adam optimizer for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM 26th international symposium on quality of service (IWQoS). Ieee; 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.P.; Abrecht, V. Better summarization evaluation with word embeddings for ROUGE. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.06034 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.; Lee, Y.C.; Hwang, W.S.; Kim, S.W. Improving the accuracy of top-N recommendation using a preference model. Information Sciences 2016, 348, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratanch, N.; Chitrakala, S. A survey on extractive text summarization. In Proceedings of the 2017 international conference on computer, communication and signal processing (ICCCSP). IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K. Abstractive summarization: An overview of the state of the art. Expert Systems with Applications 2019, 121, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Yang, Z.; Gmyr, R.; Zeng, M.; Huang, X. Make lead bias in your favor: A simple and effective method for news summarization. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nenkova, A.; Vanderwende, L. The impact of frequency on summarization. Microsoft Research, Redmond, Washington, Tech. Rep. MSR-TR-2005 2005, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalcea, R.; Tarau, P. Textrank: Bringing order into text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2004 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, 2004, pp. 404–411.

- Erkan, G.; Radev, D.R. Lexrank: Graph-based lexical centrality as salience in text summarization. Journal of artificial intelligence research 2004, 22, 457–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, H.; Agus, M.P.; Suhartono, D. Single document automatic text summarization using term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF). ComTech: Computer, Mathematics and Engineering Applications 2016, 7, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, A.G.; Abidi, A.I.; Chhabra, M. Fine-tuned t5 for abstractive summarization. International Journal of Performability Engineering 2021, 17, 900. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Zhao, D.; Yan, R. Multilingual Generation in Abstractive Summarization: A Comparative Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), 2024, pp. 11827–11837.

- Abualigah, L.; Bashabsheh, M.Q.; Alabool, H.; Shehab, M. Text summarization: a brief review. Recent Advances in NLP: the case of Arabic language 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Saleh, M.; Liu, P. Pegasus: Pre-training with extracted gap-sentences for abstractive summarization. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 11328–11339. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, N.; Sahu, G.; Calixto, I.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Laradji, I.H. LLM aided semi-supervision for Extractive Dialog Summarization. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2311.11462 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkus, A. Approximation theory of the MLP model in neural networks. Acta numerica 1999, 8, 143–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulnabi, A.H.; Wang, G.; Lu, J.; Jia, K. Multi-task CNN model for attribute prediction. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2015, 17, 1949–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojanapalli, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Glasner, D.; Li, D.; Unterthiner, T.; Veit, A. Understanding robustness of transformers for image classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 10231–10241.

- Dhruv, P.; Naskar, S. Image classification using convolutional neural network (CNN) and recurrent neural network (RNN): A review. Machine learning and information processing: proceedings of ICMLIP 2019 2020, 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsunami, Y.; Taki, M. Sequencer: Deep lstm for image classification. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 38204–38217. [Google Scholar]

- Krubiński, M. Multimodal Summarization. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, J. Learning task relationships in evolutionary multitasking for multiobjective continuous optimization. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2020, 52, 5278–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, F.; Shah, M.A.; Maple, C.; Islam, S.U. A novel internet of things-enabled accident detection and reporting system for smart city environments. sensors 2019, 19, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Preum, S.M.; Ahmed, M.Y.; Tärneberg, W.; Hendawi, A.; Stankovic, J.A. Data sets, modeling, and decision making in smart cities: A survey. ACM Transactions on Cyber-Physical Systems 2019, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, S.; Chang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Amini, L.; Wang, Z. Adversarial robustness: From self-supervised pre-training to fine-tuning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 699–708.

- Yang, Y.; Wan, F.; Jiang, Q.Y.; Xu, Y. Facilitating multimodal classification via dynamically learning modality gap. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 62108–62122. [Google Scholar]

| Train | Valid | Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Num. Papers | 615 | 65 | 163 |

| Avg. Num. Words in papers | 6784.90 | 7088.75 | 6836.77 |

| Avg. Num. Words in Summary | 124.30 | 128.78 | 125.64 |

| Avg. Num. Image in Papers | 6.69 | 6.85 | 6.74 |

| Max. Num. Image in Papers | 19 | 17 | 25 |

| Min. Num. Image in Papers | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Max. Num. Words in Papers | 14084 | 12746 | 13119 |

| Min. Num. Words in Papers | 2854 | 3166 | 3085 |

| Max. Num. Words in Summary | 285 | 216 | 285 |

| Min. Num. Words in Summary | 40 | 56 | 32 |

| Model | Rouge1 | Rouge2 | RougeL | RougeLSum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extractive Models | Lead3[70] | 24.9487 | 6.3754 | 13.6919 | 13.6954 |

| Sumbasic[71] | 22.9243 | 3.9666 | 11.3793 | 11.3944 | |

| TextRrank [72] | 30.9347 | 6.2924 | 17.0652 | 17.0658 | |

| LexRank[73] | 29.6314 | 5.8603 | 16.184 | 16.2027 | |

| TF-IDF[74] | 24.8868 | 5.0350 | 11.4188 | 11.4339 | |

| Abstractive Models | T5 [75] | 30.4562 | 7.5950 | 19.0483 | 19.0540 |

| Mbart[76] | 37.3201 | 9.0104 | 19.8601 | 19.8400 | |

| Led[77] | 42.1852 | 12.3763 | 20.3438 | 20.3380 | |

| Pegasus[78] | 43.6267 | 14.6201 | 24.4578 | 24.4086 | |

| DistilBart [79] | 38.9486 | 10.9574 | 21.0662 | 21.0610 | |

| Proposed | 46.5545 | 16.1336 | 24.9548 | 24.9227 |

| Type | Task | Rouge1 | Rouge2 | RougeL | RougeLSum | Top-1 | Top-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/o CM | I | - | - | - | - | 85.28% | 94.48% |

| T | 45.8707 | 15.4908 | 24.7259 | 24.6456 | - | - | |

| I+T | 46.0182 | 15.5612 | 24.7648 | 24.7674 | 85.89% | 95.09% | |

| With CM | I | - | - | - | - | 86.50% | 93.87% |

| T | 46.2762 | 15.8483 | 24.7441 | 24.7765 | - | - | |

| I+T(ours) | 46.5545 | 16.1336 | 24.9548 | 24.9227 | 87.12% | 95.71% |

| Type | Task | Rouge1 | Rouge2 | RougeL | RougeLSum | Top-1 | Top-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/o SEM | I | - | - | - | - | 84.66% | 93.87% |

| T | 45.8372 | 15.6966 | 24.5167 | 24.5102 | - | - | |

| I+T | 46.2108 | 15.8813 | 24.7682 | 24.8199 | 85.28% | 95.09% | |

| With SEM | I | - | - | - | - | 86.50% | 93.87% |

| T | 46.2762 | 15.8483 | 24.7441 | 24.7765 | - | - | |

| I+T(ours) | 46.5545 | 16.1336 | 24.9548 | 24.9227 | 87.12% | 95.71% |

| Task | Model | 10 | 30 | 50 | 80 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text query Image | MLP [80] | 0.0181 | 0.0253 | 0.0282 | 0.0310 | 0.0324 |

| CNN [81] | 0.0179 | 0.0242 | 0.0276 | 0.0303 | 0.0316 | |

| Transformer [82] | 0.0162 | 0.0231 | 0.0263 | 0.0290 | 0.0304 | |

| RNN [83] | 0.0172 | 0.0246 | 0.0277 | 0.0304 | 0.0319 | |

| LSTM [84] | 0.0154 | 0.0214 | 0.0248 | 0.0278 | 0.0289 | |

| Proposed | 0.0216 | 0.0286 | 0.0315 | 0.0344 | 0.0356 | |

| Image query Text | MLP [80] | 0.0256 | 0.0311 | 0.0341 | 0.0378 | 0.0385 |

| CNN [81] | 0.0193 | 0.0242 | 0.0270 | 0.0299 | 0.0312 | |

| Transformer [82] | 0.0244 | 0.0312 | 0.0334 | 0.0369 | 0.0383 | |

| RNN [83] | 0.0153 | 0.0241 | 0.0283 | 0.0318 | 0.0332 | |

| LSTM [84] | 0.0170 | 0.0228 | 0.0256 | 0.0289 | 0.0302 | |

| Proposed | 0.0270 | 0.0344 | 0.0375 | 0.0409 | 0.0420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).