Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines infant mortality as the death of a child before reaching one year of age. The infant mortality rate (IMR) specifically refers to the number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births within a given year. This metric is often used as a key indicator of the overall health and socioeconomic conditions of a population, reflecting access to healthcare, maternal health, and nutrition. Congenital anomalies contribute significantly to health service expenditure worldwide, as they necessitate intensive medical care for affected infants and their mothers. Additionally, the psychological impact on parents, who may experience the trauma of losing a child at an early age, is profound [

1]. There are a number of initiatives in health systems worldwide including the “Healthy People” programme in the United States, the National action plan for the health of children and young people in Australia [

2] and in the United Kingdom (UK) the Saving babies lives programme committed to achieve a 50% reduction in stillbirths and maternal and neonatal deaths by 2025 [

3].

In the UK, infant mortality has improved since the 1980s with an equivalent to 3.7 deaths per 1,000 live births, however, the neonatal mortality rate (i.e. the death of an infant in the first 28 days) has risen from 2.5 in 2014 to 2.8 per 1000 births in 2019. The predominant causes of infant mortality are preterm birth complications, infections, birth asphyxia, and notably congenital anomalies [

4]. These anomalies can arise from genetic causes such as chromosomal abnormalities and gene mutations affecting organ development [

1]. Environmental influences that encompass maternal infections, nutritional deficiencies, such as folic acid, and exposure to harmful substances during pregnancy such as alcohol, or drugs can be attributors to congenital anomalies..

Congenital anomalies impact infant and caregivers’ long-term health and well-being and health service utilisation. Early detection and identification of the CA is important to allow for parents to understand the consequences for their child (including whether or not they terminate the pregnancy), and for clinicians to better support the child and mother [

4,

5]. The management of CA is of growing importance to the NHS and health services globally where specific cost estimates linked to congenital anomalies vary depending on the type and severity of the anomaly. For instance, in 2003, overall newborn hospital costs in the United States were estimated at

$10 billion, with congenital anomalies accounting for a substantial portion of these expenses [

6,

7].

To support detection rates and help clinicians and families make appropriate and better-informed decisions it’s important to explore the relationship between specific CAs and resultant infant mortality. The study we present here pooled the existing data on CAs and infant mortality, consolidating the evidence to improve clinical practices, guide policy development, and enhance public awareness, for the benefit of infants and their families.

Methods

An evidence synthesis was developed using a systematic review and meta-analysis. As per PRISMA guidelines, good practice and for the purpose of transparency, the study protocol was published in PROSPERO (CRD42024506465). The systematic review and meta-analysis is reported as per the PRISMA guidelines. The primary aim is to report infant mortality linked to a variety of congenital anomalies.

Search Strategy

Multiple electronic databases of PubMed, Science Direct and Web of Science were used to pool peer reviewed and published studies reporting on infant mortality, associated risks and service provision issues as well as impact. Broad key terms words of congenital anomalies, birth defects and infant mortality. The studies were then screened by 2 researchers in the team based for study eligibility. All studies were selected in the first instance using the Population/Participant, Intervention(s), Comparison and Outcome (PICO) strategy. An independent reviewer screened the studies included within the final sample size by reading the full text.

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Randomised clinical trials and non-randomised clinical trials published in English between the 30th of April 1980 and 30th of December 2023 were included. All studies reporting on Anencephaly, Craniorachischisis, Iniencephaly, Encephalocele, Spina bifida, Microcephaly, Microtia/Anotia, Orofacial clefts, Cleft lip only, Cleft lip and palate, Exomphalos, Gastroschisis, Hypospadias, Reduction defects of upper and lower limbs, Talipes equinovarus/club foot, Congenital heart defects, Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, Common truncus, Interrupted aortic arch, Transposition of great arteries, Tetralogy of Fallot, Pulmonary valve atresia, Tricuspid valve atresia, Oesophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula, Large intestinal atresia/stenosis, Anorectal atresia/stenosis, Renal agenesis/hypoplasia, Absent nails, Accessory tragus, Anterior anus, Auricular tag or pit, Bifid uvula or cleft uvula, Lop ear, Natal teeth, Micrognathia, Cleft uvula, Plagiocephaly, Branchial tag, Camptodactyly, Plagiocephaly, Polydactyl type B tag, Preauricular appendage, Cup ear, Cutis aplasia, Rocker bottom feet, Single crease, Single transverse palmar , Single umbilical artery Small penis, Syndactyly involving second and third toes, Umbilical hernia , Hydrocele, Facial asymmetry and Extra nipples were included into the study.

Data Analysis

A meta-analysis was used to reported pooled p-values along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed using funnel plots -test (P-value) and .

Risk of Bias Quality Assessment

All studies within the data sample were critically appraised using the predefined variables followed by the assessment for methodological quality and risk of bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa-Scale (NOS). The NOS scale is an 8-item instrument with 3 quality parameters of selection, outcome and comparability where studies are rated as good, fair or poor on a scale of 0 to 3.

Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed using an Eggers test in addition to the use of the Trim and Fill (TAF) method. TAF reports publication bias within funnel plots to adjust for the overall effect estimate.

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed to better understand and report the heterogeneity of studies reporting congenital anomalies.

Results

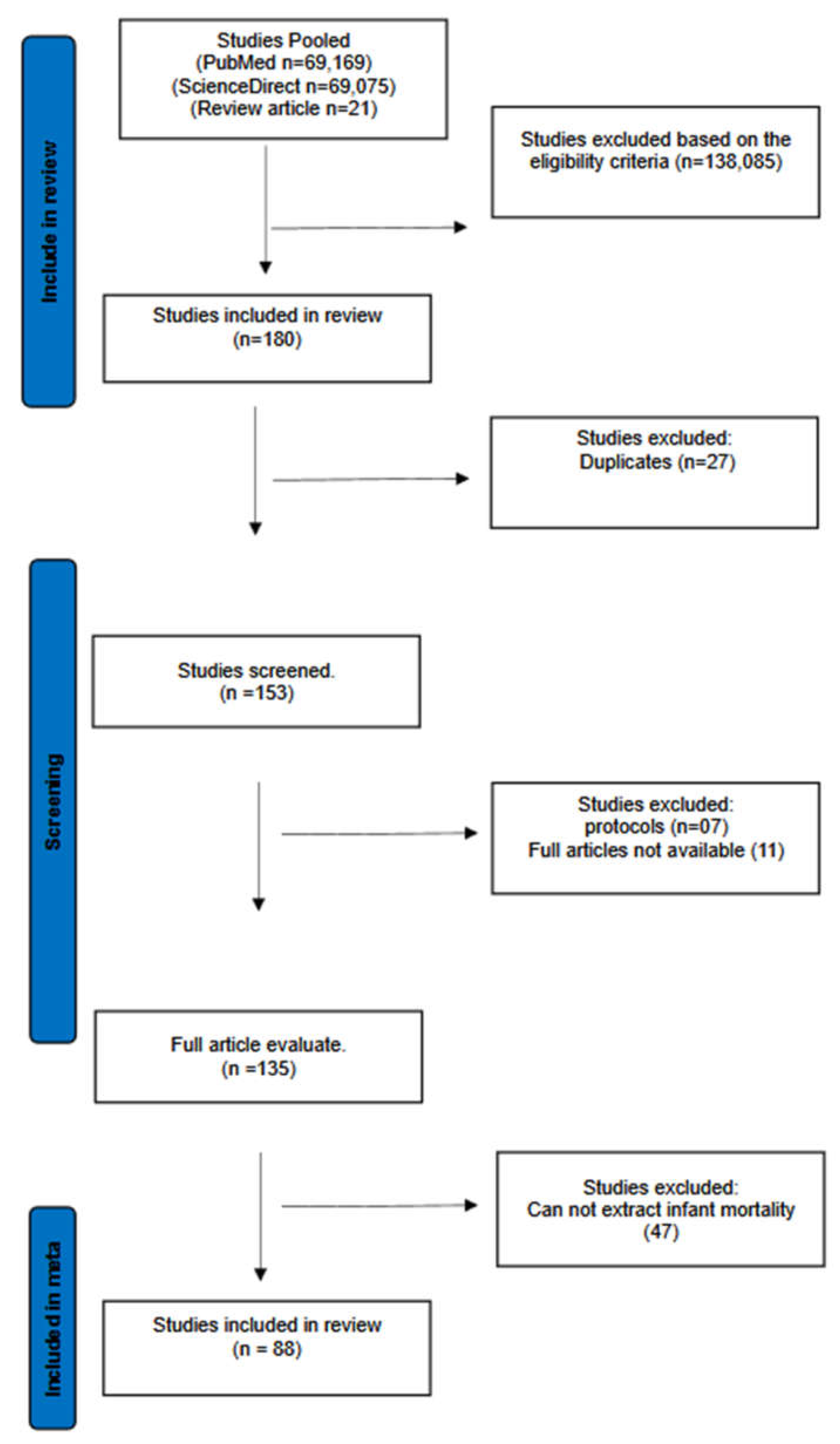

The initial data pool comprised of 138,265 publication. After removing duplicates, and including relevant studies, a total of 88 studies were systematically included, as indicated in the PRISMA flow-chart (

Figure 1). The study characteristics are indicated in Table 1.

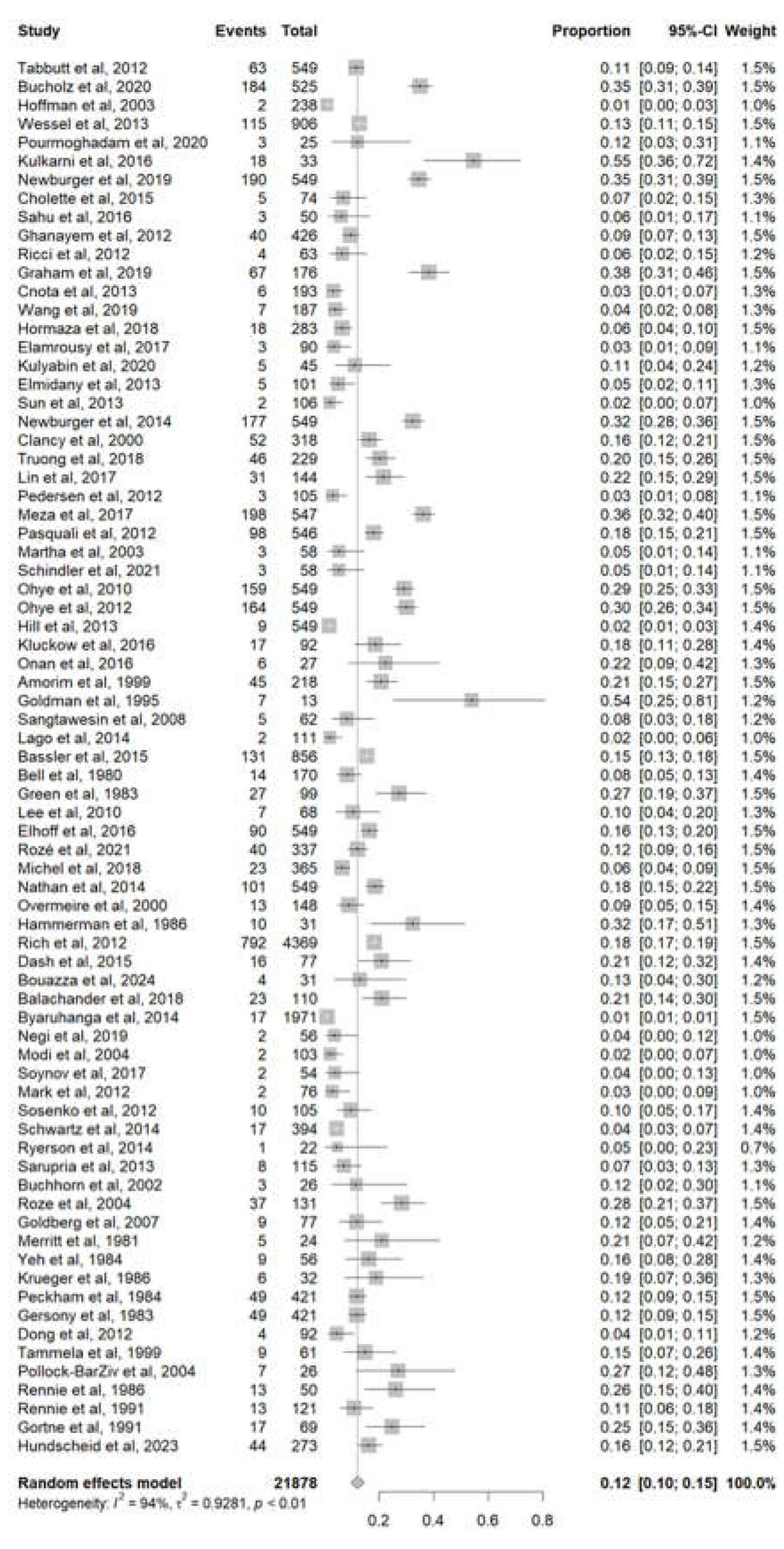

The Prevalence of Infant Mortality Linked to Congenital Anomalies

A total of 75 studies with a sample size of 21878 patients reported the infants’ mortality of congenital anomalies. The pooled mortality was 12% (95% CI 10%-15%). A high heterogeneity was detected with I

2 = 94% and p-value < 0.01 (

Figure 2).

Infant Mortality Based on Congenital Anomaly

A variety of congenital anomalies were attributed to infant mortality and described below;

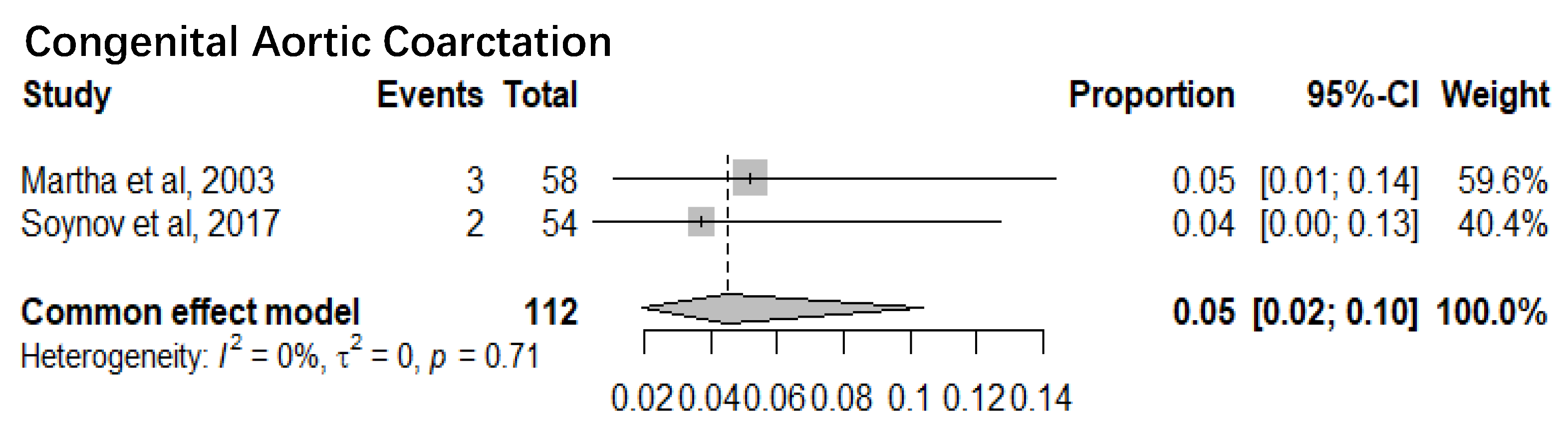

1. Congenital Aortic Coarctation

Two studies with a sample size of 112 patients reported the mortality of congenital aortic coarctation patients. The pooled mortality of congenital aortic coarctation patients was 5% (95% CI 2%-10%). The I

2= 0% and p-value= 0.71 showed there was minimal statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 3).

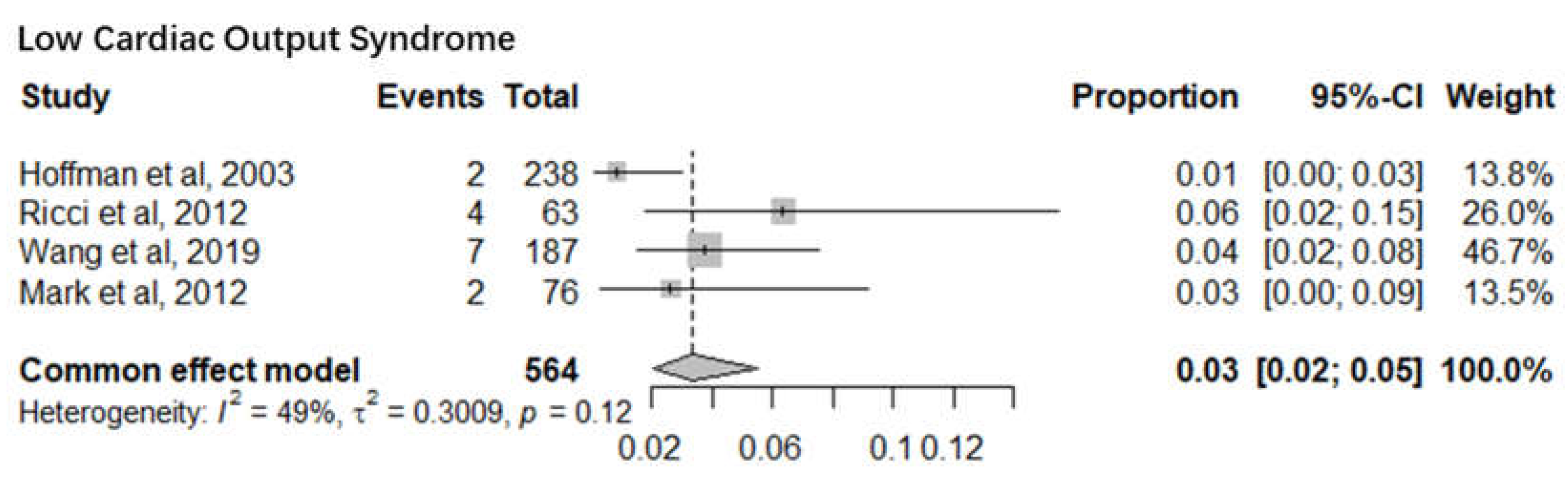

2. Low Cardiac Output Syndrome

Four studies with a sample size of 564 infants reported the mortality of low cardiac output syndrome infants after cardiac surgery. The pooled mortality was 3% (95% CI 2%-5%). The I

2= 49% and p-value= 0.12 indicate minimal statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 4).

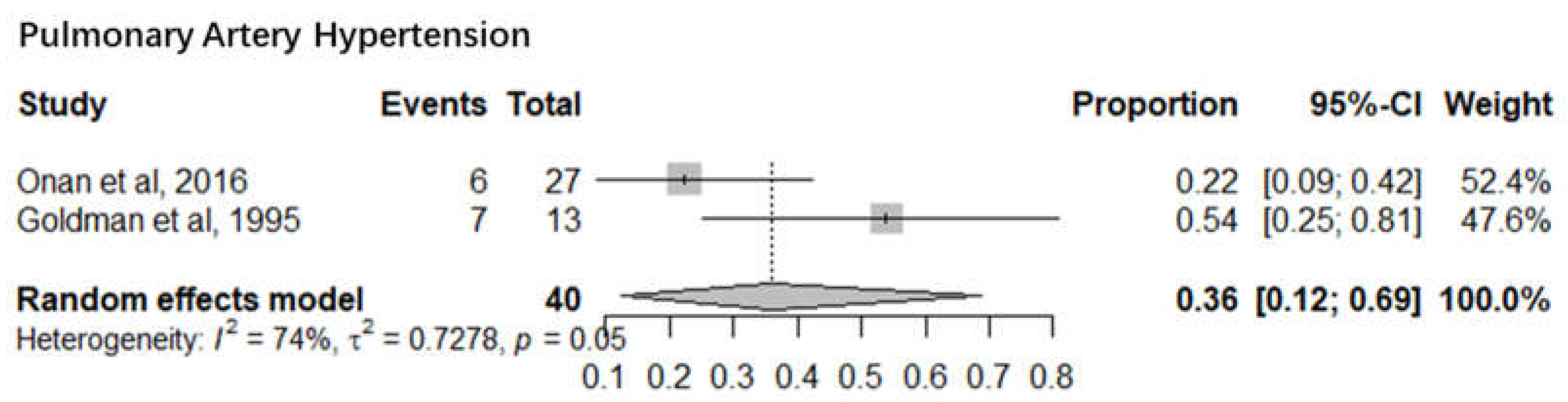

3. Pulmonary Artery Hypertension

Severe pulmonary hypertension is still a cause of morbidity and mortality in children after cardiac operations. Two studies with a sample size of 40 infants reported the mortality of pulmonary artery hypertension infants after cardiac surgery. The pooled mortality of pulmonary artery hypertension infants was 36% (95% CI 12%-69%). The I

2= 74% and p-value= 0.05 indicated significant statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 5).

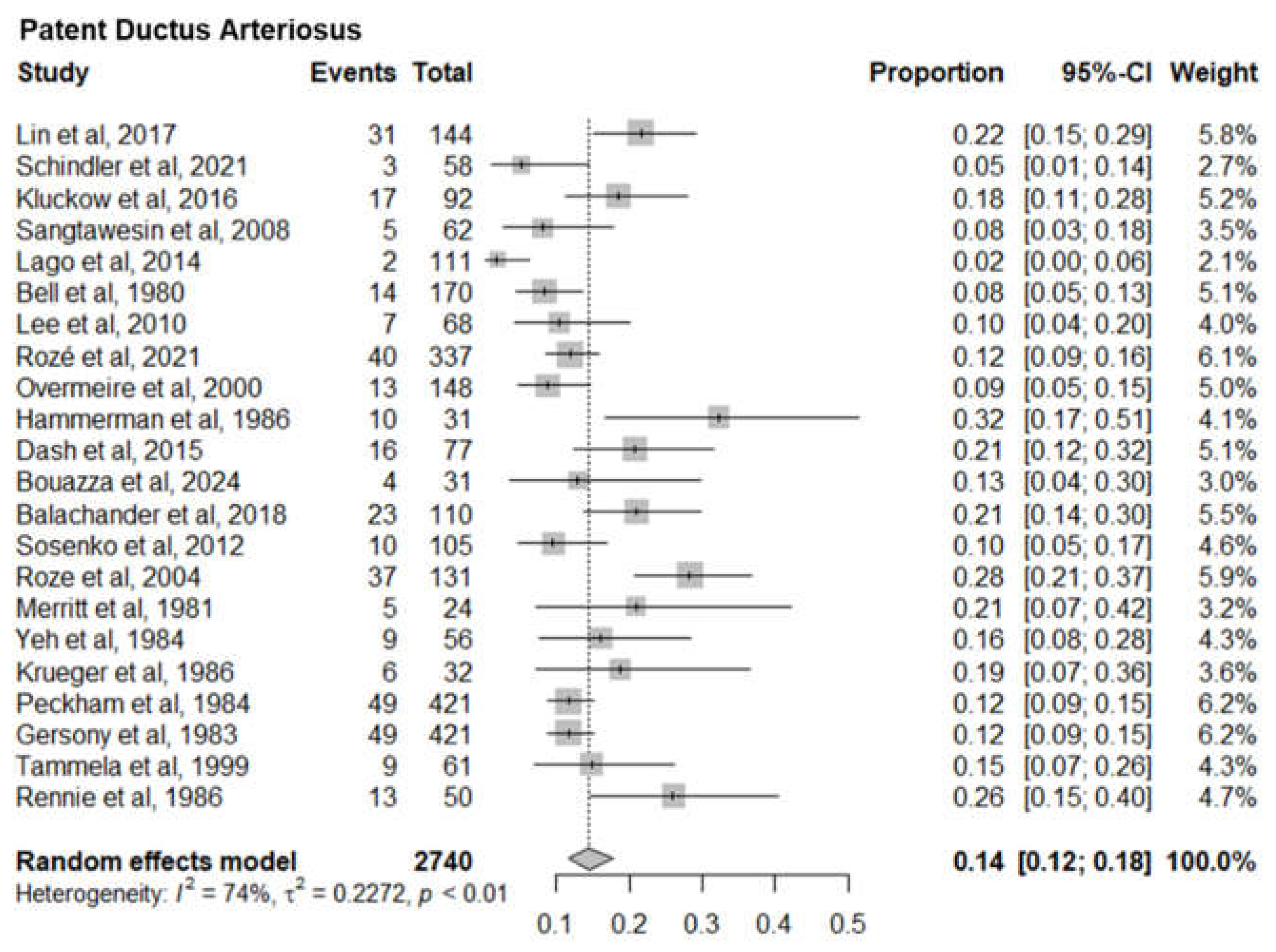

4. Patent Ductus Arteriosus

PDA is a common cause of mortality and morbidity among very low birth weight infants. Twenty two studies with a sample size of 2740 neonates reported the mortality of patent ductus arteriosus infants. The pooled mortality of patent ductus arteriosus infants was 14% (95% CI 12%-18%). The I

2= 74% and p-value< 0.01 indicated a significant statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 6).

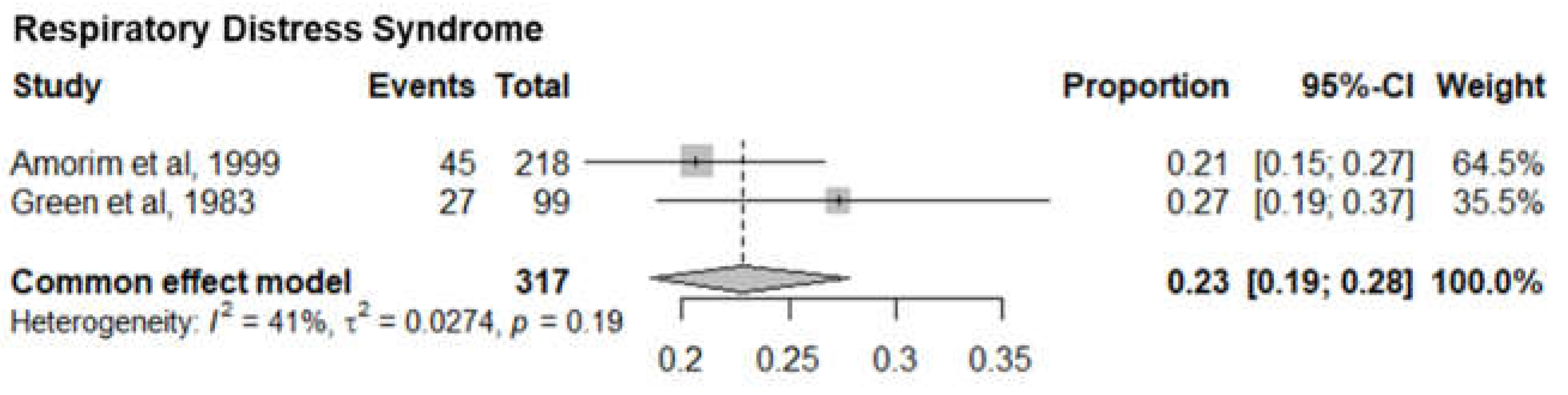

5. Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Two studies with 319 premature infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome reported the mortality of respiratory distress syndrome infants. The pooled mortality was 23% (95% CI 19%-28%). The I

2= 41% and p-value= 0.19 showed minimal statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 7).

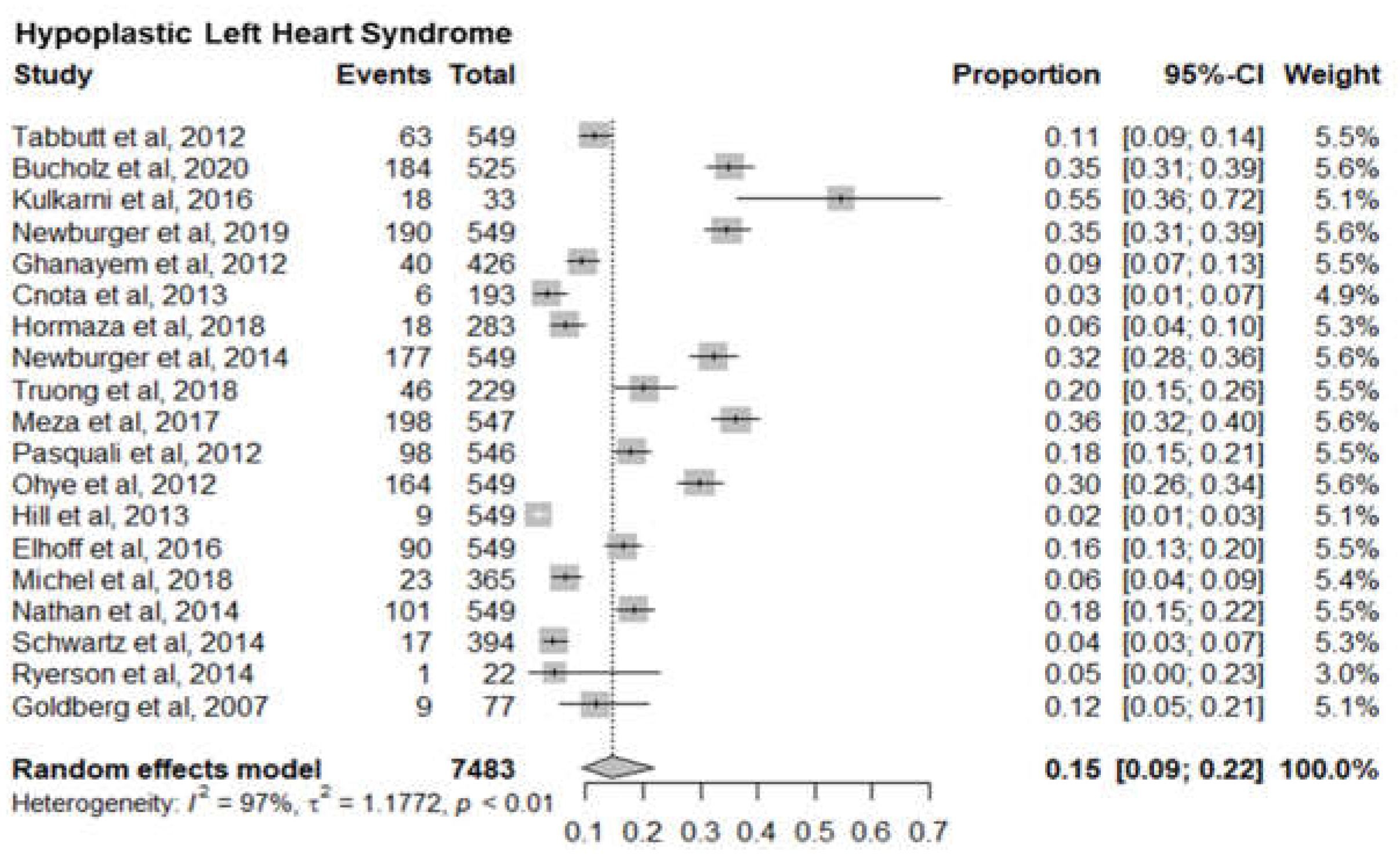

6. Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

Nineteen studies with 7483 newborn infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome reported the mortality of hypoplastic left heart syndrome infants. The pooled mortality of left heart syndrome infants was 15% (95% CI 9%-22%). The I

2= 97% and p-value< 0.01 in indicated significant statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 8).

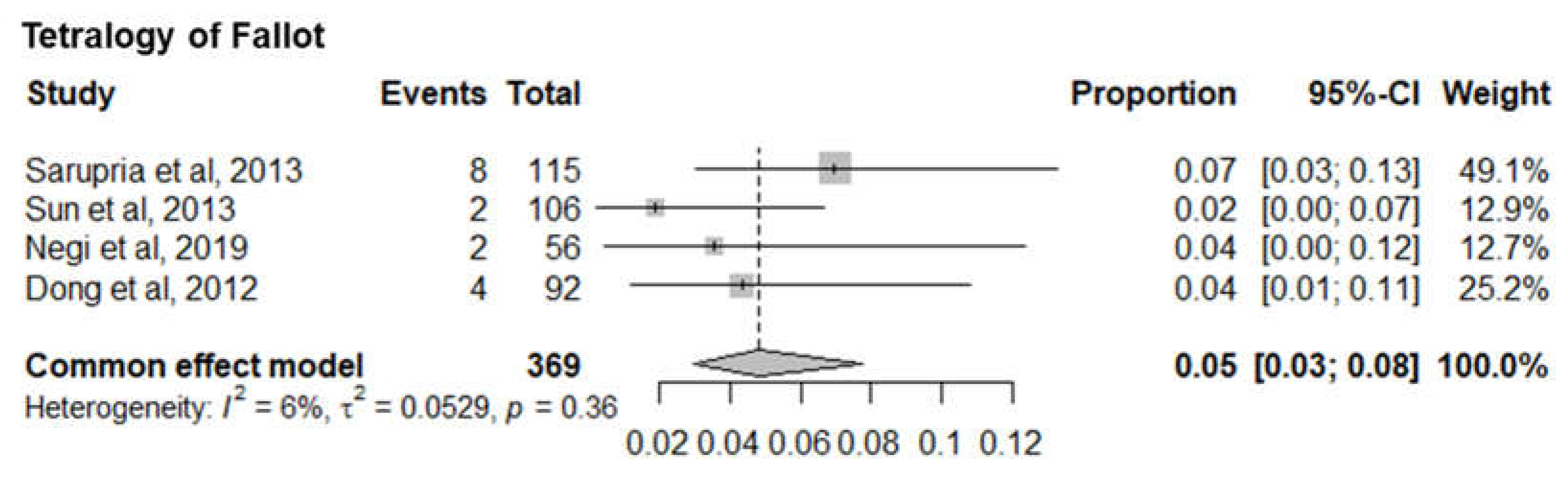

7. Tetralogy of Fallot

Four studies with 369 infants with tetralogy of Fallot (TOP) reported the mortality of TOF infants. The pooled mortality of TOF infants was 5% (95% CI 3%-8%). The I

2= 6% and p-value= 0.36 showed minimal statistical heterogeneity (

Figure 9).

Discussion

Seven sub-meta-analyses were performed of which 5 studies reported the infant mortality associated with six specific Congenital heart defects. Our results show a much higher mortality for Pulmonary Artery Hypertension (36%) (95% CI 12%-69%) than Low Cardiac Output Syndrome (3%) (95% CI 2%-5%). Of the other 4 Congenital Heart defects, Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome had the highest mortality of 15% (95% CI 9%-22%) followed by Congenital Aortic Coarctation at 5% (95% CI 2%-10%), Patent Ductus Arteriosus at 14% (95% CI 12%-18%) and Tetralogy of Fallot at 5% (95% CI 3%-8%). Mortality rates identified can serve as a proxy for healthcare system performance in diagnosing and managing CAs. Based on the identified evidence context of healthcare settings, these findings can be an indication of unequal access, lack of advanced neonatal services and delayed interventions. This could also be a marker of prenatal screening gaps, perinatal and postnatal care deficiencies requiring improved maternal-child health programs.

Two sub-meta-analyses reported surgical outcomes following Low Cardiac Output Syndrome and Pulmonary Artery Hypertension that could have contributed to infant mortality. These conditions incurred post-cardiac surgery where the researchers did not mention any surgical history that participants may have had due to the congenital heart anomaly, which could impact post-operative complications and surgical outcomes. As a result, these findings may underestimate, or overestimate risks linked to altered hemodynamics or other physiological changes that are vital for clinical management. Also, in the absence of cumulative burden of prior interventions, mortality rate may be disproportionately analysed attributing to bias in mortality associations that could limit the applicability of the findings.

The findings of this study, particularly the elevated mortality rate for Pulmonary Artery Hypertension (PAH) at 36%, confirms our understanding of it as a significant post-surgical risk factor. It also reflects on the long-term impact of undiagnosed, untreated or sub optimally managed congenital anomalies, particularly common in low-resource settings where access to surgical repair is limited. For instance, Ivy et al. (2013) similarly reported that PAH contributes substantially to poor surgical outcomes in infants with congenital heart disease [

8]. However, the stark contrast between the mortality of PAH and Low Cardiac Output Syndrome (LCOS) in this study (36% vs 3%) may differ slightly from other studies that show more comparable risk levels between these two conditions [

9]. This could suggest either population-specific differences or variations in clinical management. The results also highlight that Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) presents a higher mortality risk (15%) compared to other congenital anomalies like Tetralogy of Fallot (5%) and Patent Ductus Arteriosus (14%). Yet, the mortality for Tetralogy of Fallot we discovered is lower than previously observed, where studies, such as Brown et al. (2015), reported higher rates due to complex surgical procedures [

10]. These discrepancies underscore the need for further comparative studies to evaluate surgical techniques and post-operative care in different settings. Overall, this study adds to the body of evidence but highlights the need for contextual analysis across populations.

Practice Implications

Our findings can help design better standard operating procedures, core outcome sets for optimising research conducted and healthcare policies. In HICs, advanced technologies and resources allow for comprehensive post-surgical monitoring, including continuous haemodynamic assessments, which improve survival rates, particularly for conditions like Low Cardiac Output Syndrome (LCOS) , or PAH, that can be managed with advanced therapies like prostacyclin or endothelin receptor antagonists[

10]. More precise identification may inform intervention strategies in HICs that can benefit from cutting-edge surgical techniques, specialised intensive care, and access to pharmacological treatments, which significantly enhance patient outcomes [

10,

13].

In HICs, better informed identification of CAs alongside of sophisticated models that incorporate genetic, socio-demographic, and clinical data enabled personalised care could improve survival rates and overall health outcomes, particularly for those from underserved populations [

14]. This will also reduce the burden on the mental health and wellbeing of parents and caregivers making difficult decisions over termination, a significant cause for increased healthcare service utilisation and associated costs [

16].

It is worth noting that there are persistent health inequalities in HICs and socioeconomic disparities and cultural factors, particularly amongst minoritised or economically disadvantaged communities may influence the uptake of screening services and prevent timely prenatal care.

The impact of our findings on post-surgical monitoring, intervention strategies, and risk stratification in LMICs is limited by challenges of resource and health service capacity and capability. There are a number of barriers to congenital anomaly detection including limited access to advanced prenatal screening and diagnostic technologies [

15]. There are also limits in access to, or the success of, congenital heart disease surgery due to the lack of infrastructure, specialised equipment, advanced therapies and trained personnel [

11,

12]. In LMICs, risk assessment is typically less precise due to the absence of routine diagnostics and long-term follow-up as well as determinants of health, such as poverty, malnutrition, and limited access to healthcare.

Limitations

The sample sizes across the sample were relatively small and limits the generalisability of findings, increasing the risk of bias and reducing statistical power. At the secondary analysis level, smaller studies contribute to heterogeneity and potential over- or underestimation of true effects.

Most of the studies in our study sample were conducted within high-income nations than low-middle-income countries that often face challenges like limited funding, resources and inadequate resources. The lack of equity within the studies indicate the importance of conducting inclusive and comprehensive research to promote early detection and intervention, and which explores the challenges of scalability and affordability for patients accessing healthcare services in rural and urban settings.

Study designs often lacked core health outcomes and well thought-out designs that could assist with identifying predefined variables and outcome measures for qualitative and quantitative datasets. Qualitative study designs in particular reported caregiver experiences with minimal quantifiable measures that limited the ability for these to be re-analysed as part of a broader evidence synthesis.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates 7 common conditions that attribute to infant mortality that can assist clinicians, academics and policymakers better design standard operating procedures, core outcome sets and policies. We recommend that evidence-based approaches be used in a living format with a standardised set of clinical, scientific and patient-reported outcomes to be reported across prospective studies. Future research needs to exhibit better awareness of inclusivity, equity and diversity and there is a notable lack of research in LMICS.

Author Contributions

GD conceptualised the evidence synthesis and developed the methodology. GD and HC conducted the initial searches using multiple search engines. GD, HC and VP extracted the pooled data. GD, SJ, SW and YW re-extracted the data, including but not limited to confirming a final data pool, addressing missing data issues and categorisation. VP, TM and GD conducted a thematic content analysis. GD, SJ, SW and YW conducted the statistical analysis. JQS reviewed the analysis. GD and IL conceptualised and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors critically appraised and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Birmingham Health Partners Evaluation Service.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

Data is publicly available.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Congenital disorders 2023 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects.

- Care AGDoHaA. National action plan for the health of children and young people 2020–2030. In: Care DoHaA, editor. 2019.

- England N. Saving babies’ lives version 3 2023.

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S, You D, Lee AC, Waiswa P, et al. Every Newborn: progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. The lancet. 2014;384(9938):189-205.

- NHS. NHS fetal anomaly screening programme (FASP) 2023 [Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/nhs-fetal-anomaly-screening-programme-fasp.

- Alt S, McHugh A, Permalloo N, Pandya P. Fetal anomaly screening programme. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine. 2020;30(12):395-7.

- Cuevas KD, Silver DR, Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Bobo CM. The cost of prematurity: hospital charges at birth and frequency of rehospitalizations and acute care visits over the first year of life: a comparison by gestational age and birth weight. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2005;105(7):56-64.

- Ivy DD, Abman SH, Barst RJ, Berger RM, Bonnet D, Fleming TR, et al. Pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62(25S):D117-D26.

- Massé L, Antonacci M. Low cardiac output syndrome: identification and management. Critical Care Nursing Clinics. 2005;17(4):375-83.

- Brown KL, Crowe S, Franklin R, McLean A, Cunningham D, Barron D, et al. Trends in 30-day mortality rate and case mix for paediatric cardiac surgery in the UK between 2000 and 2010. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000157.

- Das D, Dutta N, Das S, Ghosh S, Chowdhuri KR. Late presentation of congenital heart diseases in low-and middle-income countries: impact on outcomes. Indian Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2024:1-14.

- Zheleva B, Atwood JB. The invisible child: childhood heart disease in global health. The Lancet. 2017;389(10064):16-8.

- Bobillo-Perez S, Sanchez-de-Toledo J, Segura S, Girona-Alarcon M, Mele M, Sole-Ribalta A, et al. Risk stratification models for congenital heart surgery in children: Comparative single-center study. Congenital Heart Disease. 2019;14(6):1066-77.

- Goley SM, Sakula-Barry S, Adofo-Ansong N, Ntawunga LI, Botchway MT, Kelly AH, et al. Investigating the use of ultrasonography for the antenatal diagnosis of structural congenital anomalies in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2020;4(1).

- Sundus A, Siddique O, Ibrahim MF, Aziz S, Khan J. The role of children with congenital anomalies in generating parental depressive symptoms. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2013;46(4):359-73.

- Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Journal of Social Work Education. 2008;44(sup3):105-13.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).