Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

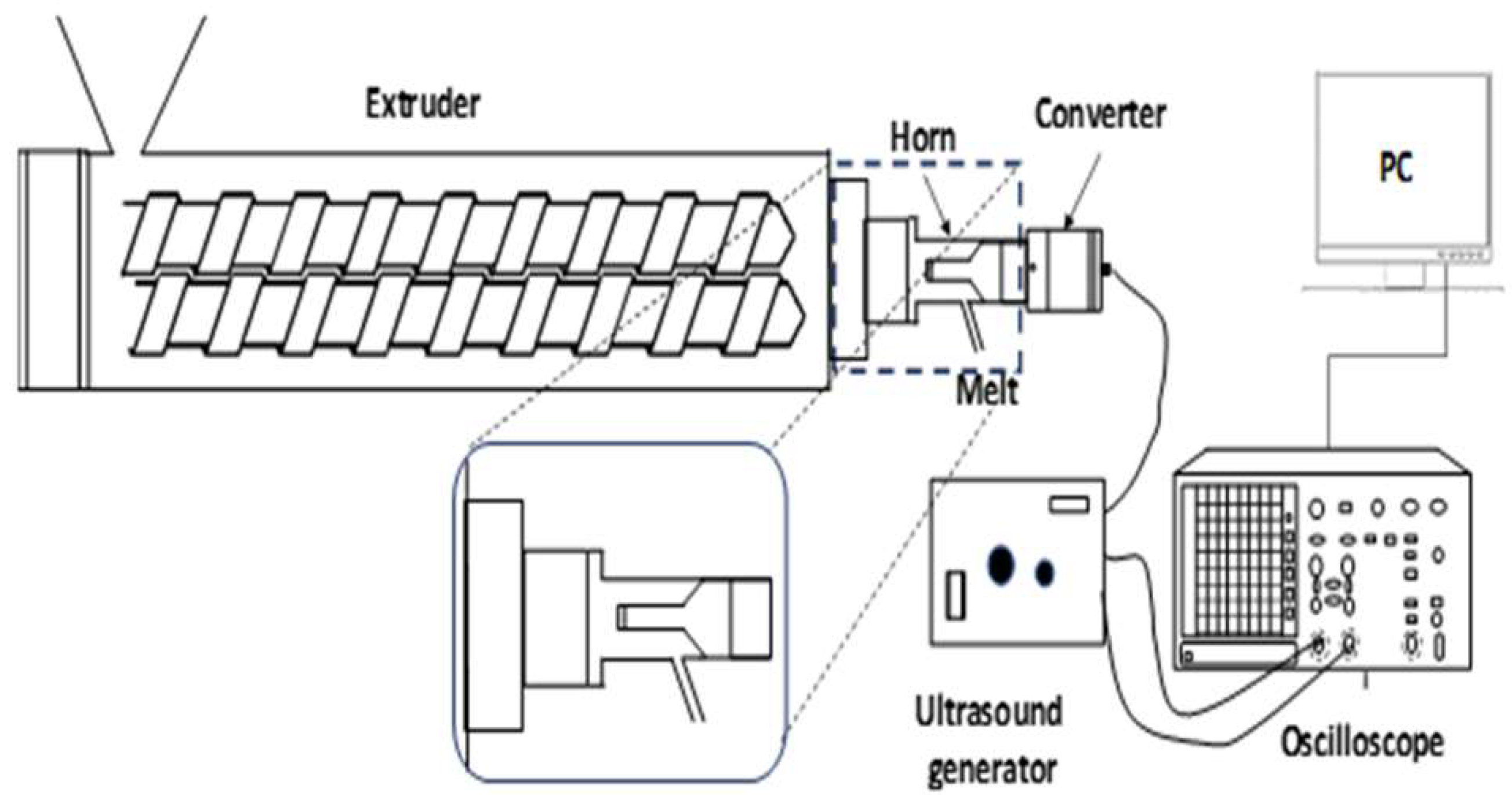

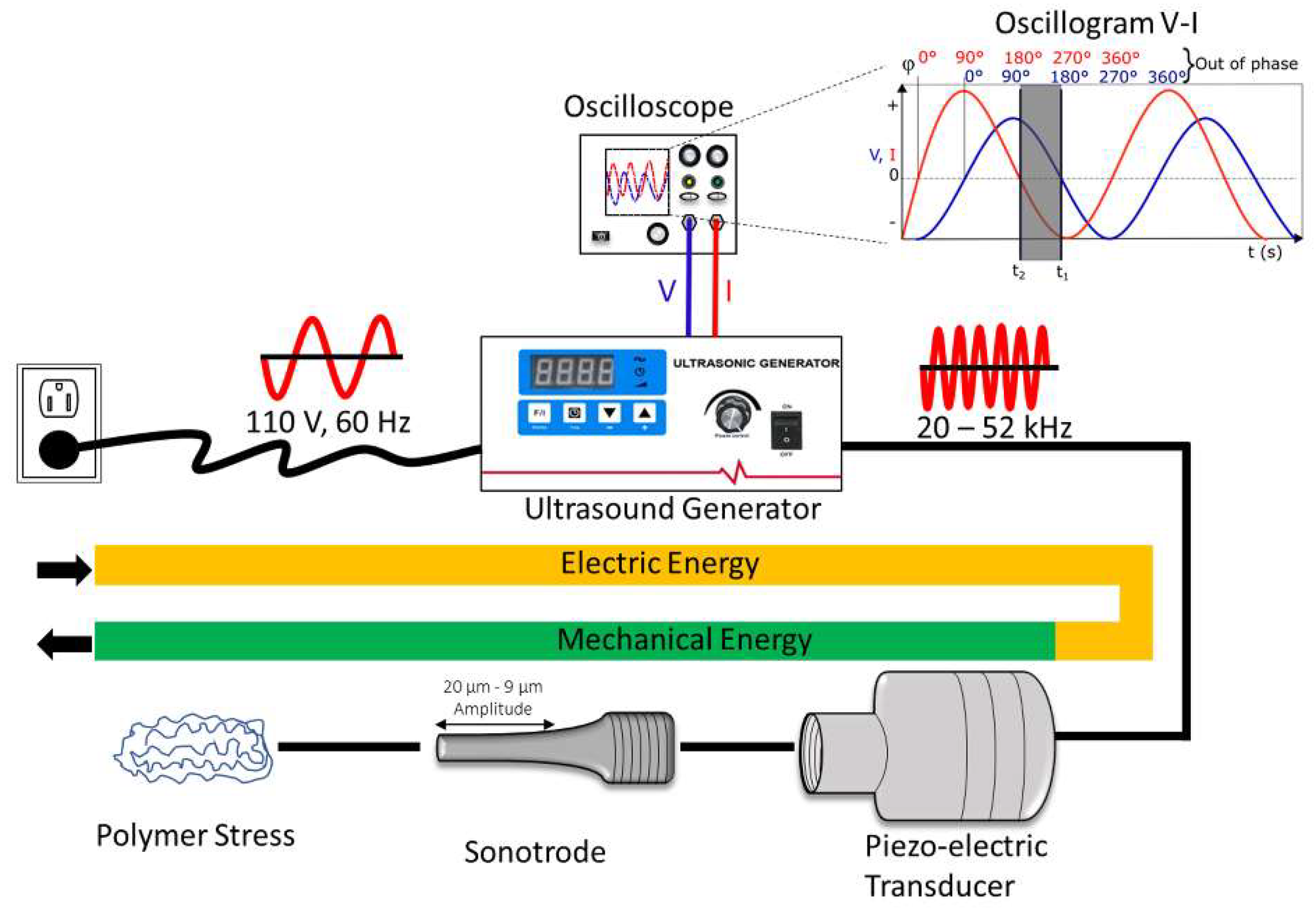

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Characterization Techniques

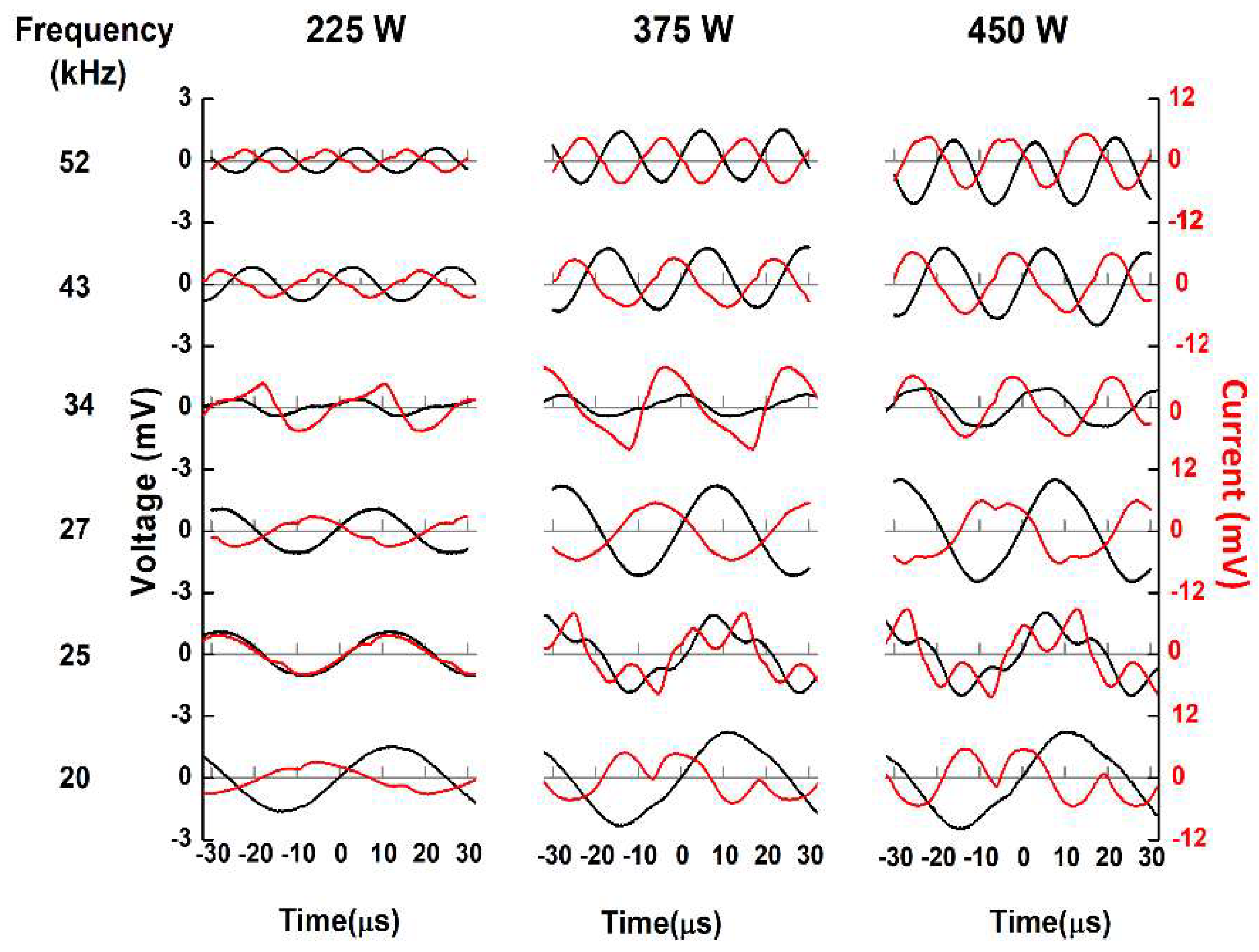

2.3.1. Oscillograms

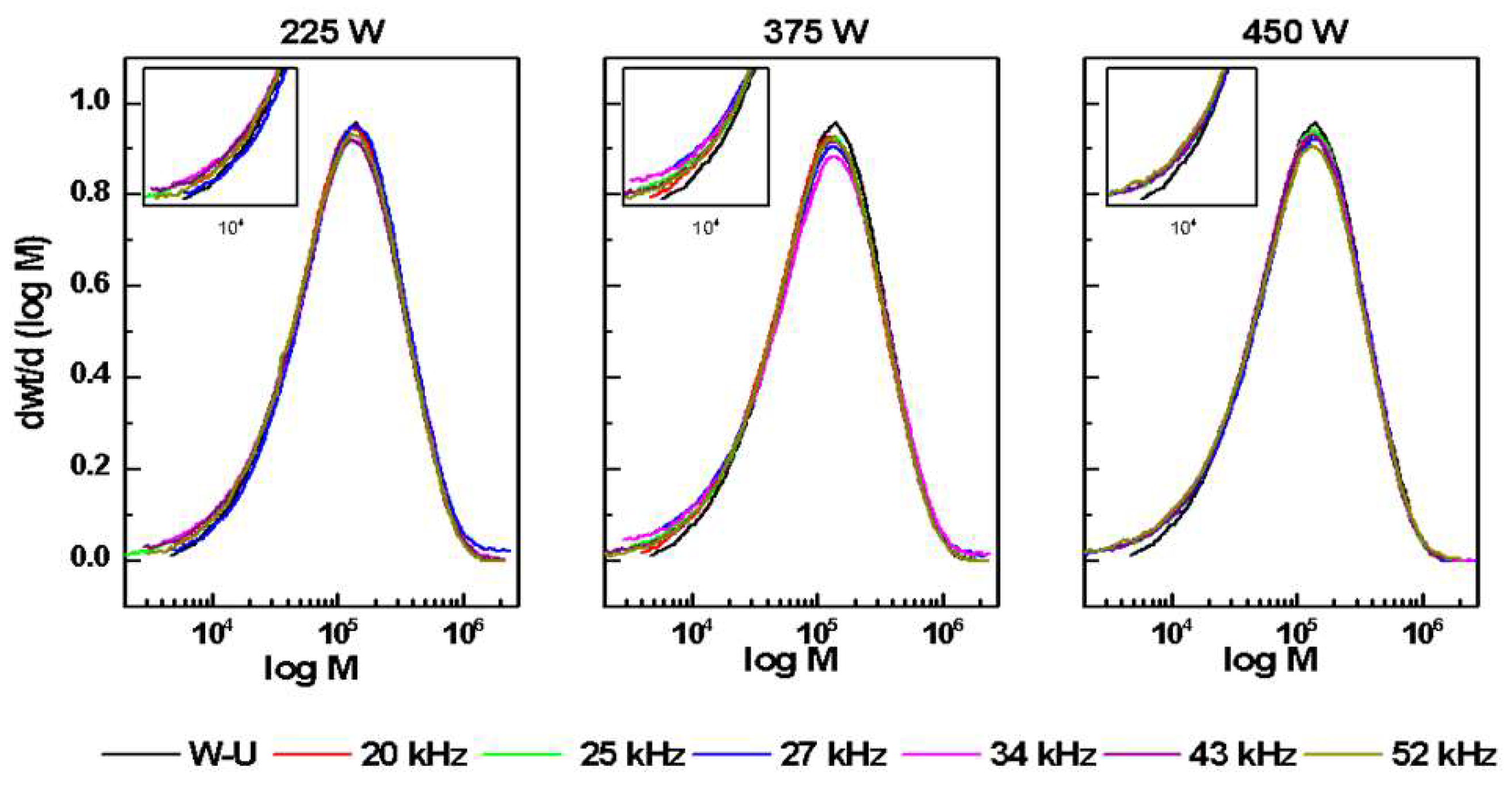

2.3.2. Molecular Weight Analysis

2.3.3. Melt Flow Index (MFI)

2.3.4. Capillary Rheometry

3. Results

3.1. Collection of Oscillograms

3.2. Molecular Weight Analysis

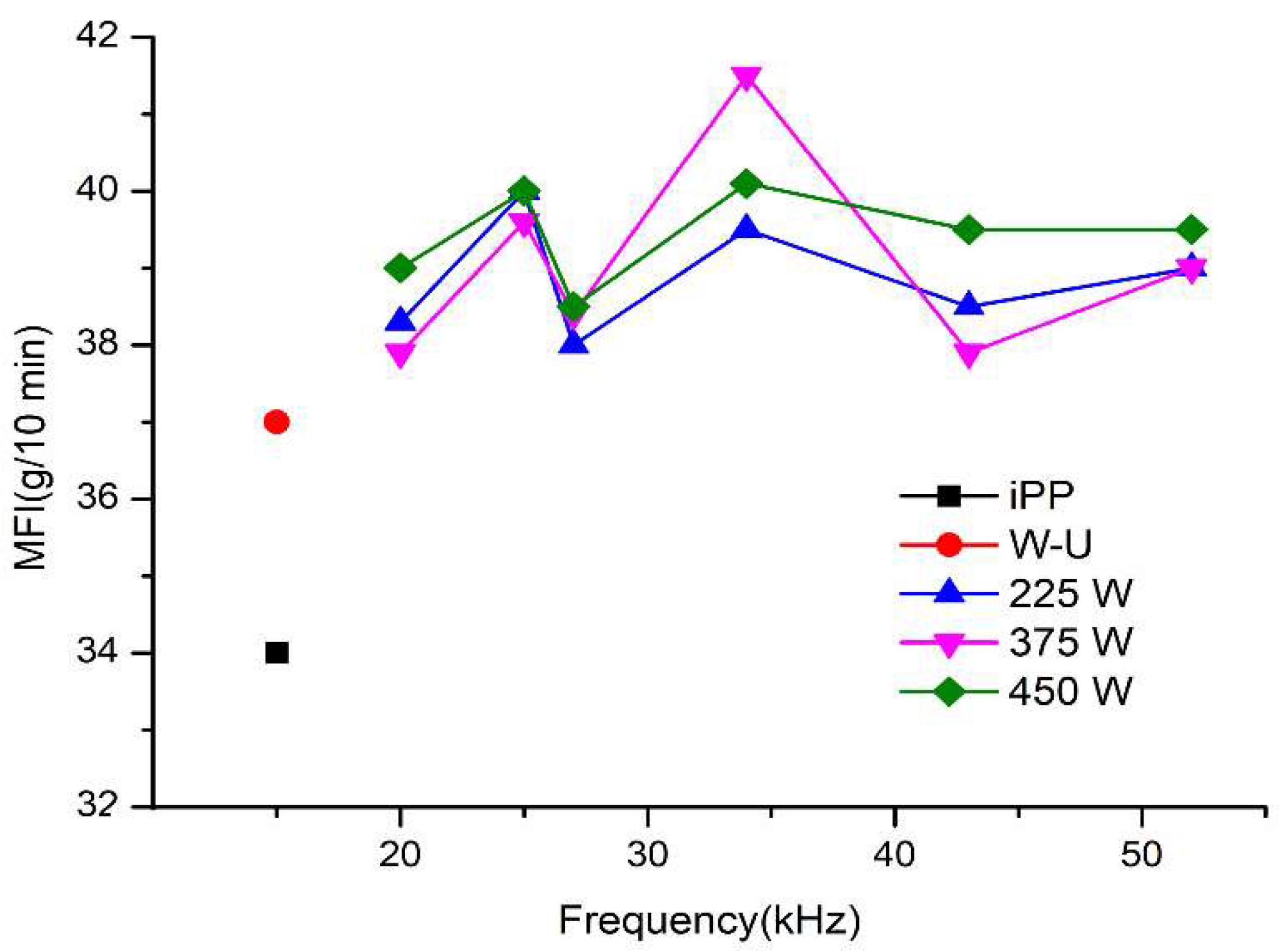

3.3. Effect of Ultrasonic Waves on MFI

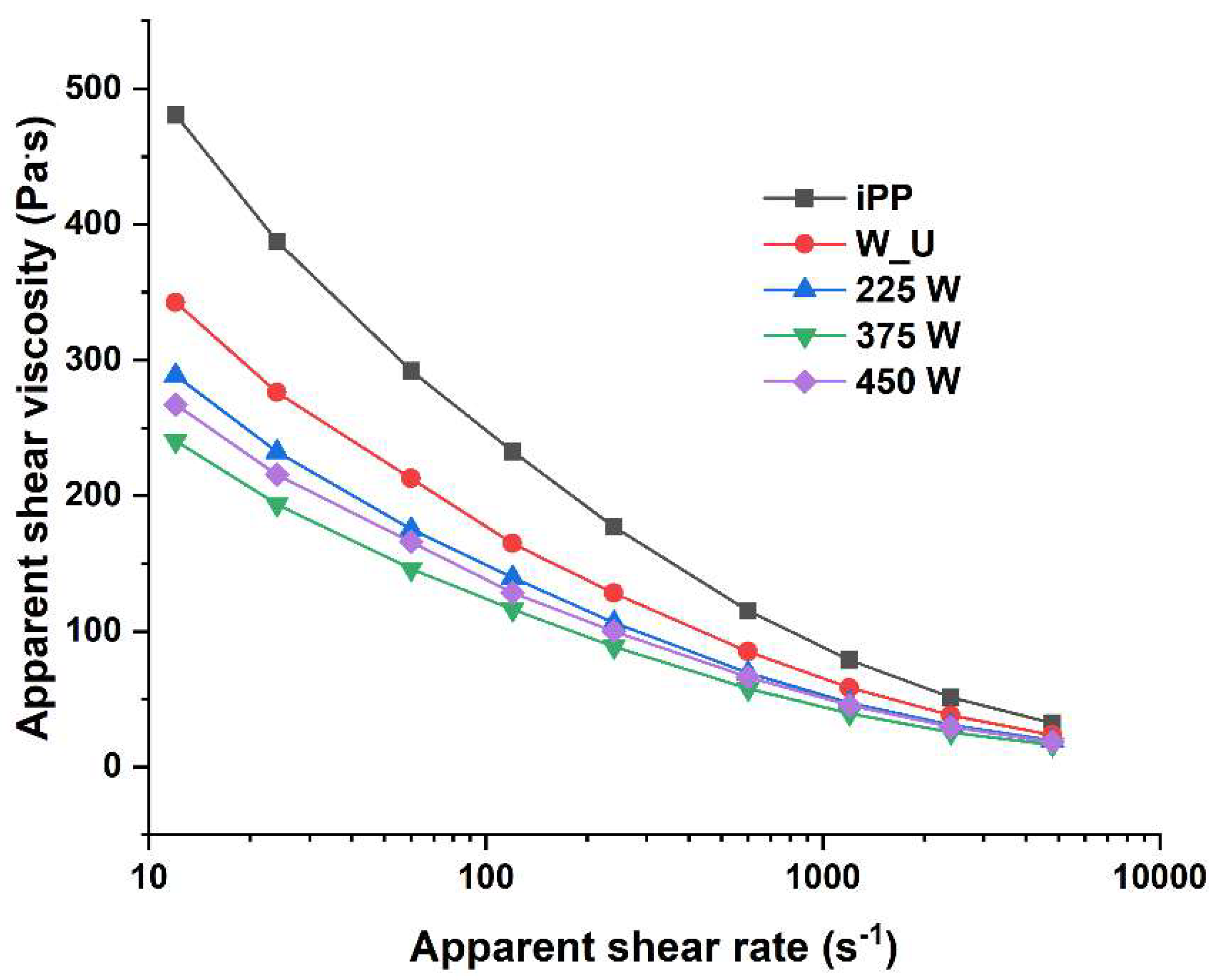

3.4. Rheological Analysis

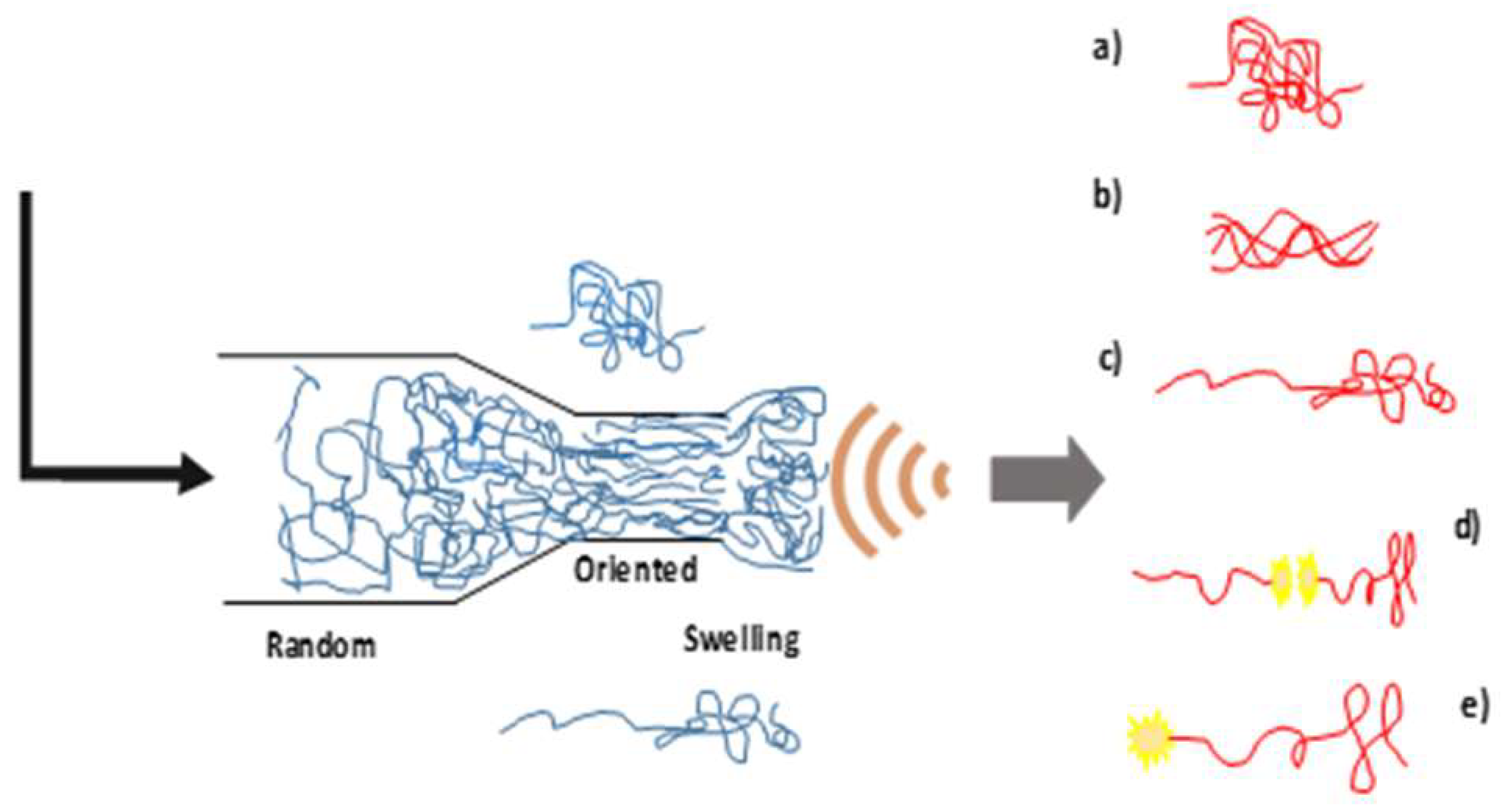

3.5. Polymer Chain Interactions and Ultrasonic Wave Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leighton, TG. What is ultrasound? Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2007;93:3–83. [CrossRef]

- Hamidi H, Sharifi Haddad A, Wisdom Otumudia E, Rafati R, Mohammadian E, Azdarpour A, et al. Recent applications of ultrasonic waves in improved oil recovery: A review of techniques and results. Ultrasonics 2021;110:106288. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Mathur M. Ultrasound Physics & Overview. Ultrasound Fundam., Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021, p. 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Timothy J M, Lorimer JP. Applied sonochemistry – the uses of power ultrasound in chemistry and processing. 1st ed. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag; 2002.

- Dengaev A, V. , Khelkhal MA, Getalov AA, Baimukhametov GF, Kayumov AA, Vakhin A V., et al. Innovations in Oil Processing: Chemical Transformation of Oil Components through Ultrasound Assistance. Fluids 2023;8:108. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Lee Y, Lee JW. Effect of ultrasound on the properties of biodegradable polymer blends of poly(lactic acid) with poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate). Macromol Res 2007;15:44–50. [CrossRef]

- Gunes K, Isayev AI, Li X, Wesdemiotis C. Fast in situ copolymerization of PET/PEN blends by ultrasonically-aided extrusion. Polymer (Guildf) 2010;51:1071–81. [CrossRef]

- Swain SK, Isayev AI. PA6/clay nanocomposites by continuous sonication process. J Appl Polym Sci 2009;114:2378–87. [CrossRef]

- Mata-Padilla JM, Avila-Orta CA, Medellin-Rodriguez FJ, Hernandez-Hernandez E, Jimenez-Barrera RM, Cruz-Delgado VJ, et al. Structural and Morphological Studies on the Deformation Behavior of Polypropylene/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Nanocomposites Prepared Through Ultrasound-Assisted Melt Extrusion Process. J Polym Sci PART B-POLYMER Phys 2015;53:475–91. [CrossRef]

- Kim KY, Nam GJ, Lee JW. Continuous extrusion of long-chain-branched polypropylene/clay nanocomposites with high-intensity ultrasonic waves. Compos Interfaces 2007;14:533–44. [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Juárez, JA. Power ultrasonics: new technologies and applications for fluid processing. Ultrason. Transducers, Elsevier; 2012, p. 476–516. [CrossRef]

- Price GJ, West PJ, Smith PF. Control of polymer structure using power ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem 1994;1:S51–7. [CrossRef]

- Coates PD, Barnes SE, Sibley MG, Brown EC, Edwards HGM, Scowen IJ. In-process vibrational spectroscopy and ultrasound measurements in polymer melt extrusion. Polymer (Guildf) 2003;44:5937–49. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Determination of velocity and attenuation of shear waves using ultrasonic spectroscopy. J Acoust Soc Am 1996;99:2871–5. [CrossRef]

- Verdier C, Piau M. Analysis of the morphology of polymer blends using ultrasound. J Phys D Appl Phys 1996;29:1454–61. [CrossRef]

- Kim K-B, Lee S, Kim M-S, Cho B-K. Determination of apple firmness by nondestructive ultrasonic measurement. Postharvest Biol Technol 2009;52:44–8. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zahra, NH. Measuring melt density in polymer extrusion processes using shear ultrasound waves. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2004;24:661–6. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zahra NH, Seth A. In-process density control of extruded foam PVC using wavelet packet analysis of ultrasound waves. Mechatronics 2002;12:1083–95. [CrossRef]

- Erwin L, Dohner J. Measurement of mixing in polymer melts by focused ultrasound. Polym Eng Sci 1984;24:1277–82. [CrossRef]

- Brown EC, Olley P, Coates PD. In line melt temperature measurement during real time ultrasound monitoring of single screw extrusion. Plast Rubber Compos 2000;29:3–13. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Min K. In-line monitoring and analysis of polymer melting behavior in an intermeshing counter-rotating twin-screw extruder by ultrasound waves. Polym Eng Sci 2005;45:998–1010. [CrossRef]

- Dias Pereira, JM. The history and technology of oscilloscopes. IEEE Instrum Meas Mag 2006;9:27–35. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V, Chandrasekhar N, Albert SK, Jayapandian J. Analysis of arc welding process using Digital Storage Oscilloscope. Measurement 2016;81:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Savyasachi N, Chandrasekar N, Albert SK, Surendranathan AO. Evaluation of Arc Welding Process Using Digital Storage Oscilloscope and High Speed Camera. Indian Weld J 2015;48:35. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian E, Parak M, Babakhani P. The Effects of Properties of Waves on the Recovery of Ultrasonic Stimulated Waterflooding. Pet Sci Technol 2014;32:1000–8. [CrossRef]

- Dengaev A, V. , Kayumov AA, Getalov AA, Aliev FA, Baimukhametov GF, Sargin B V., et al. Chemical Viscosity Reduction of Heavy Oil by Multi-Frequency Ultrasonic Waves with the Main Harmonics of 20–60 kHz. Fluids 2023;8:136. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Chen Y, Li H, Lai S-Y, Jow J. Physical and chemical effects of ultrasound vibration on polymer melt in extrusion. Ultrason Sonochem 2010;17:66–71. [CrossRef]

- Isayev AI, Wong CM, Zeng X. Effect of oscillations during extrusion on rheology and mechanical properties of polymers. Adv Polym Technol 1990;10:31–45. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Li J, Guo S, Li H. Mechanochemical degradation kinetics of high-density polyethylene melt and its mechanism in the presence of ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason Sonochem 2005;12:183–9. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Gonzalez C, Avila-Orta C, Martinez-Colunga G, Lionetto F, Maffezzoli A. A Measure of CNTs Dispersion in Polymers With Branched Molecular Architectures by UDMA. IEEE Trans Nanotechnol 2016;15:731–7. [CrossRef]

- Ávila Orta CA, Martínez Colunga JG, Bueno Baqués D, Raudry López CE, Cruz Delgado VJ, González Morones P, et al. Proceso continuo asistido por ultrasonido de frecuencia y amplitud variable, para la preparación de nanocompuestos a base de polímeros y nanopartículas. 323756B, 2014.

- Cao Y, Li H. Influence of ultrasound on the processing and structure of polypropylene during extrusion. Polym Eng Sci 2002;42:1534–40. [CrossRef]

- Medellín Rodríguez FJ, Gudiño Rivera J, Rodríguez Velázquez JG, Lara Sánchez JF, Salinas Hernández M. Gradually modified fibers of Yucca Filifera ( Asparagaceae ) as biodegradable and mechanical reinforcement of polypropylene composites. Polym Compos 2024;45:751–62. [CrossRef]

| Power (W) | Frequency (kHz) | Period (s) | Vmax (mV) | Imax (mV) | Phase shift (°) |

| W_U | - | - | - | - | - |

| 225 | 20 | 5.0 x 10-5 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 133 |

| 25 | 4.0 x 10-5 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 0 | |

| 27 | 3.7 x 10-5 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 144 | |

| 34 | 2.9 x 10-5 | 0.5 | 4.6 | 75 | |

| 43 | 2.3 x 10-5 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 121 | |

| 52 | 1.9 x 10-5 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 151 | |

| 375 | 20 | 5.0 x 10-5 | 2.2 | 5.0 | 132 |

| 25 | 4.0 x 10-5 | 2.0 | 8.2 | 29 | |

| 27 | 3.7 x 10-5 | 2.2 | 5.5 | 139 | |

| 34 | 2.9 x 10-5 | 1.2 | 7.8 | 13 | |

| 43 | 2.3 x 10-5 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 108 | |

| 52 | 1.9 x 10-5 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 180 | |

| 450 | 20 | 5.0 x 10-5 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 134 |

| 25 | 4.0 x 10-5 | 2.0 | 8.8 | 35 | |

| 27 | 3.7 x 10-5 | 2.5 | 5.9 | 139 | |

| 34 | 2.9 x 10-5 | 0.9 | 11.6 | 2 | |

| 43 | 2.3 x 10-5 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 114 | |

| 52 | 1.9 x 10-5 | 1.4 | 5.4 | 155 |

| Power (W) | Frequency (kHz) |

Mw x 10-4 (g/g-mol) |

Mn x 10-4 (g/g-mol) |

Mw/Mn (dimensionless) |

| W_U | - | 17.48 | 6.70 | 2.6 |

| 225 | 20 | 16.80 | 6.34 | 2.6 |

| 25 | 16.58 | 5.10 | 3.2 | |

| 27 | 17.06 | 6.01 | 2.8 | |

| 34 | 16.98 | 5.62 | 3.0 | |

| 43 | 16.84 | 5.33 | 3.2 | |

| 52 | 16.72 | 5.83 | 2.9 | |

| 375 | 20 | 17.16 | 5.97 | 2.9 |

| 25 | 16.82 | 5.45 | 3.1 | |

| 27 | 17.57 | 5.71 | 3.1 | |

| 34 | 17.84 | 4.86 | 3.7 | |

| 43 | 16.68 | 5.01 | 3.3 | |

| 52 | 16.70 | 5.26 | 3.2 | |

| 450 | 20 | 16.74 | 6.08 | 2.8 |

| 25 | 16.76 | 5.97 | 2.8 | |

| 27 | 17.02 | 5.22 | 3.3 | |

| 34 | 17.00 | 6.35 | 2.7 | |

| 43 | 16.66 | 5.58 | 3.0 | |

| 52 | 16.86 | 4.91 | 3.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).