1. Introduction

Since its inception, clinical psychology and psychotherapy has been used in the treatment of patients in person. Currently, the advancement of technology has enabled consultation of people with mental health issues through digital means, thanks to online videoconferencing platforms. This new form of treatment, called telepsychology,has been emerging as a highly required option and even more so after the COVID-19 pandemic, in which 67.32% of North American clinical psychologists reported carrying out all their therapeutic work via telepsychology [

1].According to the American Psychological Association [

2], this service is defined as "the provision of psychological services through the use of telecommunication technologies [...] by electrical, electromagnetic, electromechanical, electro-optical or electronic means" (p. 792).

Telepsychology and its most known service, videoconferencing psychology, offer the user greater accessibility to psychological assistance, and certain limiting variables such as distance and mobility to the clinical center are eliminated or mitigated, thus allowing significant savings in time and money. Moreover, videoconferencing psychotherapy and other services from telepsychology favor the comfort and safety of the environment in which the therapeutic session takes place [

3] and allows to fight against some long-lasting problems in medical assistance such as mental health costs and waiting lists improving access to mental health professionals with specialized expertise [

4,

5]

Likewise, but less studied is the fact that telepsychology integrates user interface navigation throughout the therapeutic process, encompassing pre-session, real-time, and post-session activities. We precisely explore this novel aspect in our study, in particular the effect of virtual background in telepsychology applications or platforms. First, we will briefly introduce the study of real indoor space perception, followed by the knowledge achieved about this issue in virtual environments.

1.1. Indoor Space Perception

Our study explores how the environment is perceived in the context of a simulated mental health app. So far, this context has been physical, usually in consulting rooms. Consulting rooms are physically enclosed spaces, like offices, classrooms, and meeting rooms, and all of them provide private space for the intended purpose of interaction [

6]. Within those places, human perception of location and space is fundamental to interaction [

7]. As these enclosed spaces are the main places where people stay during the day, the effect of some conditions like illumination and color have been studied.

It has been demonstrated that lighting in leisure and working environments plays a significant role [

8,

9] and provokes an improvement of some cognitive variables such as attention and memory [

10]. In case the environment is low-illuminated, lower temperatures of color are preferred compared to high-illuminated environments, where higher temperatures of color are preferred [

11]. Each temperature affects several personal perceptions of the present places including calmness, likability, and coziness [

12].

Moreover, warm colors are better remembered and more attractive than other colors and they are an important contextual clue to navigate indoors [

13]. Light colour influences the appearance of interiors [

14], whereas brightest colours maximize the perceived height of ceilings [

15] and some colours are preferred for certain activities, for example, to study [

16]. Finally, specific colours are favored by visitors whose intention is to stay and navigate through clinical consultation premises [

17,

18].

Regarding elements of the scene, familiar rooms were preferred, elicited more positive responses and involvement with the spectator [

19]. Also, vegetation has relevance in the research of indoor spaces. In general, plants displayed on the physical room seem to improve performance and mood for many people [

20,

21] and a clear cognitive effect can be seen after presenting natural scenes for just 40 seconds, boosting the sustained attention [

11]. In addition, plants and vegetation within rooms are associated with subjective wellbeing [

22] and increased perception of air quality [

23].

Regarding non physical spaces, recent research suggests that manipulating particular features of virtual environments leads to measurable changes in key responses. Variation via virtual reality has demonstrated that large windows (but not sky type) provoke more perception of attributes such as spaciousness in small rooms [

24]. Virtual environments variation may also be achieved by online platforms manipulations. By these means, non-artificially modified backgrounds were found to be preferred by students [

25] and undergraduates tend to be more relaxed during work interviews when they have natural backgrounds [

26]. Also, natural backgrounds enhance creativity in Zoom meetings [

27] and several cognitive functions seem enhanced when solving tasks in front of a window view of nature [

28]. Nevertheless, as far as we know, no research has studied perceptive preferences when simulating different virtual settings in e-mental health and telepsychology services.

1.2. Justification

The telemedicine market, which includes services for psychotherapy and mental health, is projected to exceed

$590 million by 2032 [

29] and one of its strongest points is being patient-centered. Any attempt to improve closeness between the visitor and the provider of telepsychology services has its importance nowadays.

Being telemedicine and telepsychology so relevant nowadays, poor usability or unfriendly telemedicine dispositions may hinder patient acceptance and adoption of the service [

30]. Moreover, although in general, telepsychology or online therapy is well accepted by patients, with benefits on mental health demonstrated [

31], and appropriate ratings of the therapeutic alliance [

32], no deep exploration of perception of spaces for therapeutic purposes has been done.

We are currently navigating from a world where we remain mainly within indoor spaces [

33] to a world where virtual environments for working, studying and consulting are fully available [

34,

35].Although optimal design for mental health and telemedicine apps are important nowadays [

36], few studies encompass the contextual cues where patient-clinician interaction takes place. The concept of global characteristics of the image [

37,

38] allows us to investigate certain attributes of the image, easily detected by humans and very informative to provide a holistic description. The chosen characteristics for this study are naturalness (degree of verticality and horizontality displayed on the image as opposed to the undulating edges more representative of nature) and roughness or complexity (the number of elements that a certain scene contains), together with colour.

Our predictions are based on relevant hypotheses in the area of perception and behavior. First, we defend that naturalness in the scene viewed is going to be preferred for mental health consultation over other spaces by our participants. This is based on biophilia hypothesis. Biophilia is “an unconscious and innate need to affiliate with nature and living organisms” [

39] ( p.792). In a study about automatic associations, people were faster when choosing a natural environment than urban settings [

40]. Although not all people seem to have such attraction for nature, most of us show a pattern of autonomous activity when observing natural landscapes [

41] and natural spaces are preferred for some types of work activities [

42].

The variable complexity is also studied in this manuscript. This characteristic can be explained from an evolutionary viewpoint. Kaplan [

43] defended that human, as other animals, could have preference for information to fill up their cognitive maps (or mental models as Johnson-Laird [

44] conceptualizes). The processes behind these preferences would be unconscious and dominated by an adaptive function similar to choosing habitat [

45]. In landscape, complexity has been found to have an impact on preference in open landscapes and forests [

46,

47]. When some artificial element is present in the scene, complexity is a main factor that contributes to preference [

48], and interiors with complexity are preferred in opposition to simpler indoor spaces too [

49].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Ethical Approval

In this experimental design all the participants selected their preferred environments (or male/female figures) and dependent variables were the proper selection and the response time. Independent variables were the manipulation of complexity and naturalness within these environments.

Ethics was obtained from the Complutense University Institutional Review Board (Id number: CE_20220217-06_SOC) and the time window where the researchers administered the questionnaires and asked to fill them out was from January 1st of 2023 to December 31st of 2023.

2.2. Sample

We recruited 310 people over 18 years old (M=39.06; SD=13.7) in a convenience sampling where 59.7% were women. The pervasiveness of the knowledge and use of health applications allowed us to recruit the participants with minimum constraints. We recruited the participants from the personal and professional networks of the authors and collaborators, mainly from

www.terapiaencasa.es, an online psychological consultation service in Spain. The only inclusion criteria were to be an adult over 18 years and to possess a device to access the survey research and the exclusion criteria were to have any visual deficit.

2.3. Images Creation

For our study, human figures and indoor spaces were designed by two professional graphic designers.

Designs with human figures were initially selected on the bank image Freepik (

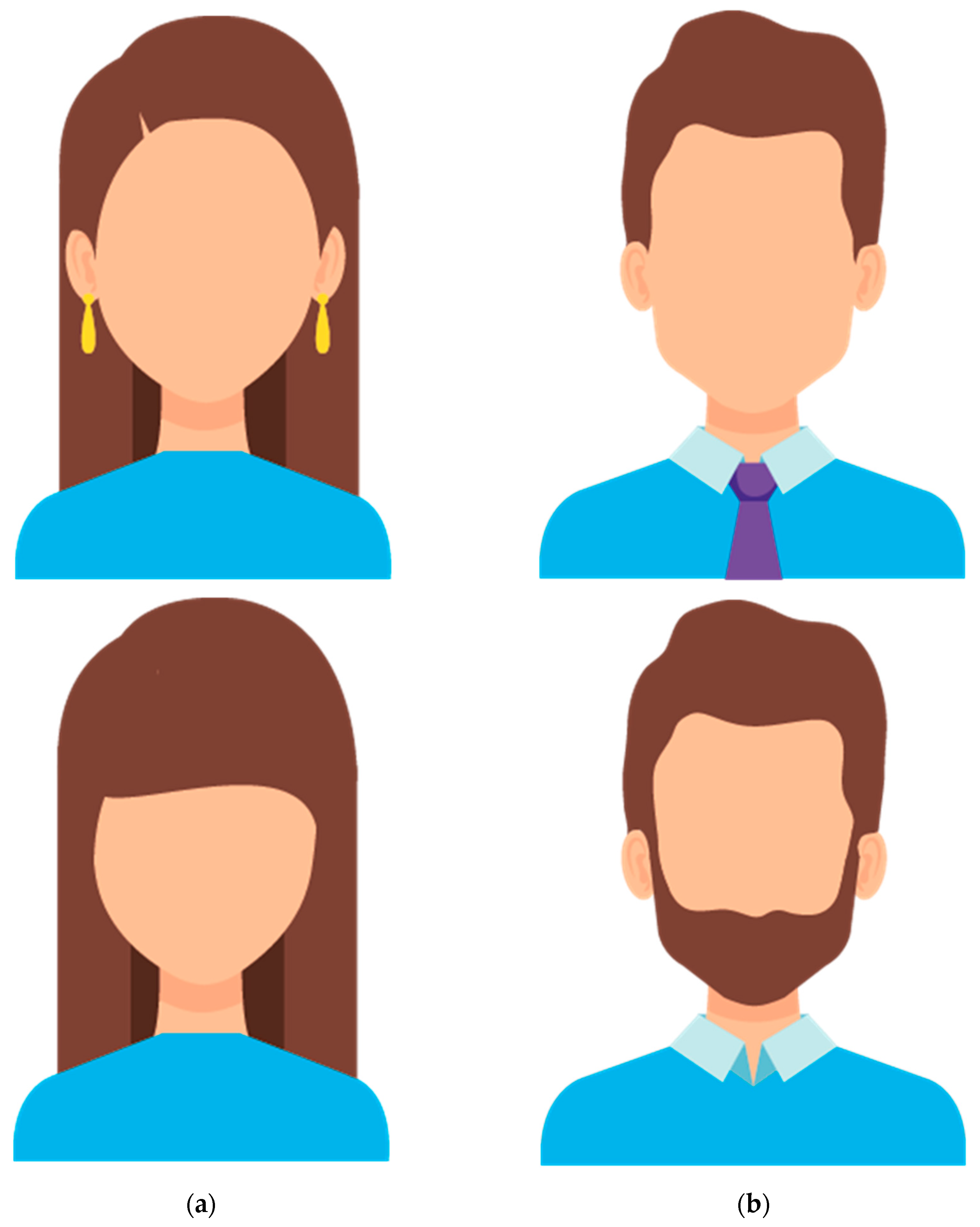

www.freepik.es). This selection was followed by precise modifications done by software Adobe Illustrator CS6 (Adobe, 2012). Human figures were edited with the pen tool simplifying facial traits and with the color picker option to include solid colors. The results of these operations were the final human figures for this study. Experimental manipulation in this case was created modifying the extension of hair in both face silhouettes: females and males. The images corresponded after the modification with an increase of low frequencies. The other option in both cases was the reduction of the hairy area and inclusion of one complement, thus, introducing details. This way, for the other pair of images, there was an increase of high frequencies. These variations can be seen in

Figure 1.

Regarding photomontages of indoor images, some examples were searched on the internet with Google motor research. Both background and details for the final photomontages were combined in congruent tone and perspective. Image-editing software Photoshop CS6 (Adobe, 2012) was also used for this task.

As it has been mentioned, we chose preferentially two global characteristics of the image to manipulate: complexity and naturalness [

38]. Naturalness (

Figure 2A) was manipulated with the inclusion of mainly indoor vegetation and plants, and complexity (

Figure 2B) was manipulated increasing the number of elements present in the room [

49]. Similar natural and artificial indoor environments have been manipulated in previous studies [

42,

50].

A third manipulation for photomontages consisted of the mix of these two attributes, where the first image was a plain office, the second included some plants and decoration, and the last one was an open environment with wood-made coaches and nature view. These mixed backgrounds can be viewed in

Figure 3.

Focusing on colour environments, we also asked for the chromatic preferred option for the ambience in hypothetical telepsychology interactions. Nine colours were selected between those proposed by [

17] for counseling rooms. In

Table 1, the link between Hex code, RGB code and name for the colours surveyed is shown.

2.4. Instrument

The implementation of the online questionnaire was carried out using a combination of HTML, CSS, JavaScript and Firebase. HTML was used to define the structure of the questionnaire, CSS to design the visual appearance, and JavaScript to add interactivity and dynamism.

The database was hosted and managed on Firebase. The connection of the database with the web page is carried out by the Firebase API, which allows the extraction of the data entered in the questionnaire for its subsequent analysis and evaluation. Using cookies recognition on the user devices, we prevented any user could answer the questionnaire more than once from the same device. In addition, the user must provide an alphanumeric code provided by the research team to avoid misuse of the questionnaire. Together, these security measures guarantee the integrity and confidentiality of its data, in addition to maintaining the quality of the responses obtained.

Informative responses needed are fast, automatic, not caused by too much rationalization as [

51] have suggested. Therefore, response time was free for participants, although later on, only responses below 20 seconds were selected for the analysis.

2.5. Procedure

Participants showed their willingness to participate in the research project and then, contacted the main researcher LLLR. A particular code was linked to their set of responses in order to treat their responses anonymously. The first part of the online survey was about sociodemographic data with multiple-choice questions about the use and interest in psychological therapy, among others. The second part was about visual preferences. The questions displayed in this part were “Which of the following environments would you prefer if you needed online therapy?”, “What (female) therapist appearance do you prefer in case you should choose one in a mental health app?”, “What (male) therapist appearance do you prefer in case you should choose one in a mental health app?”, , and “Between the two options, what type of decoration would you feel most comfortable with if you needed online psychological therapy?”, being the former question formulated for both cases: naturalness (

Figure 2A) and complexity (

Figure 2B).

The questionnaire was completed on average in 4 minutes. All the reaction times for each preference response were measured, together with the option chosen.

After the completion, participants were paid 1 euro by the Spanish payment service provider Bizum.

2.6. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis followed to achieve the objectives presented was:

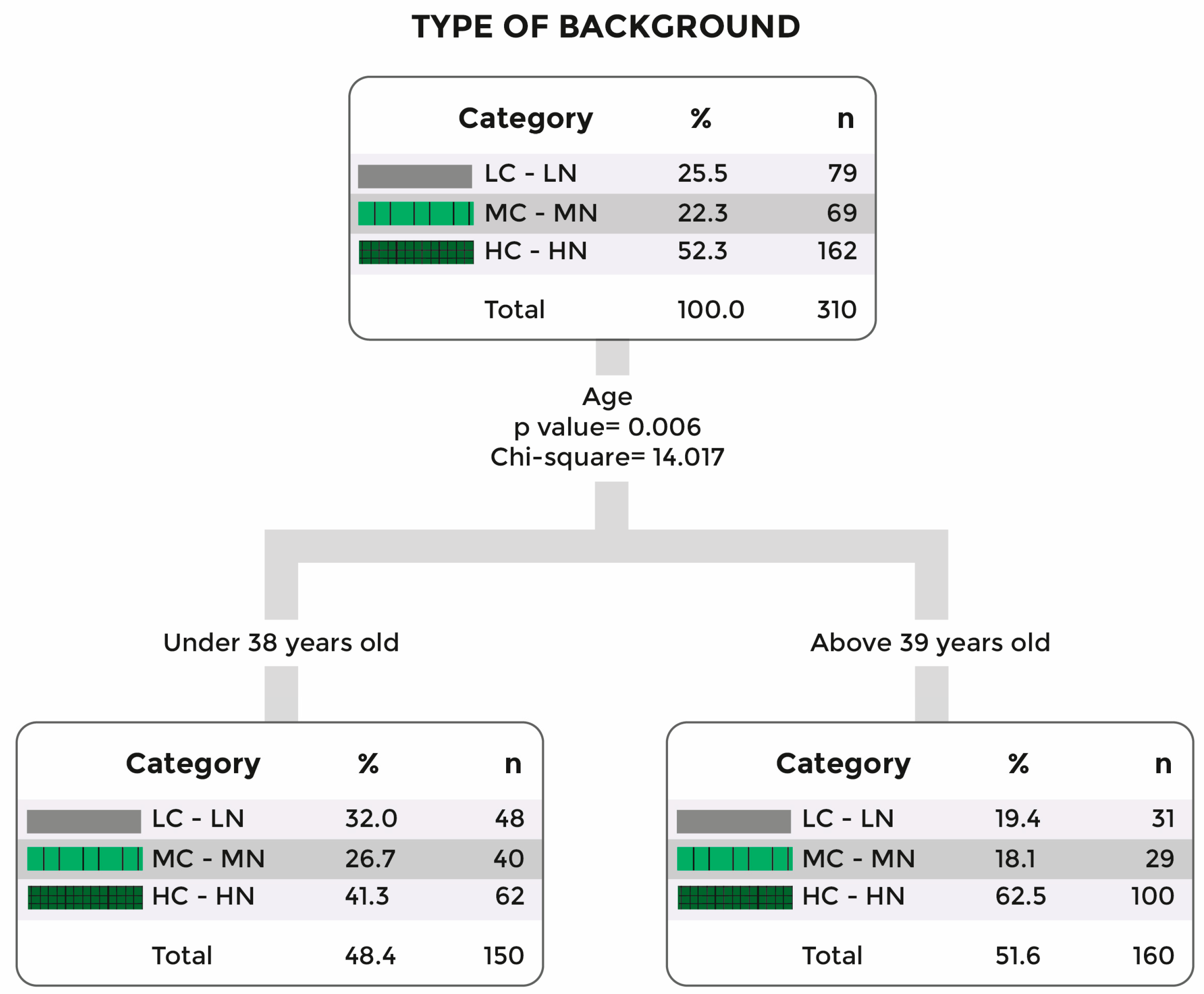

Analyzing the ANOVA for time responses and Chi-square Tables for categorical variables to see what factors influenced the user when choosing an online environment or taking any option.

Grouping individuals for each photomontage through decision trees to take their profile and characteristics into consideration.

Finally, calculating the probability that a given user uses the different proposed environments thanks to logistic regression models.

The analysis was carried out with the SPSS statistical package (IBM, version 27).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The sample responded mainly through their mobile phones (88.7%) and 156 participants (50.3%) had received psychological therapy previously. We also asked for the studies and the level of interest in psychological therapy, which can be seen in

Table 2. In this study, most people surveyed had university studies (65.2%) and a clear interest in receiving psychological therapy in the near future (81.7%).

When facing the demand about the preferred gender for the counselor in the telepsychology service, people opted mostly for “Indifferent” and a very low percentage (ranging from 2.6% to 13.6%) preferred a male psychologist within all ages. Even for men, the option of the male psychotherapist was the least demanded (16%).

3.2. Therapist Appearance

In general, participants had no preferences over therapist gender and the second most popular choice was a female therapist over a male therapist ( χ2(6, N=310) =20.71, p=<.01). When selecting potential therapists according to their attire, younger participants consistently chose the formally dressed female figure over other options (χ2(3, N=310) =16.70, p=<.01). This preference for formal attire was also observed in their selection of male therapists. Conversely, participants over 50 years old preferred casually dressed male therapists, a contrast to the younger group's choice(χ2(3, N=310) =23.50, p=<.01).

In addition, an analysis of response times revealed a significant difference in how quickly participants chose the male therapist's appearance. Specifically, participants who expressed 'indifference' towards future psychological treatment took significantly longer to make their choice compared to those who had clear opinions with either no interest or high interest in therapy. (F(4, 277) = 2.715, p = .03). However, this delay in decision-making among indifferent participants was not observed when they were choosing the female therapist's appearance.

On the contrary, when requested for the appearance of male therapist, the age did not influence in terms of time response, but it did influence when asked for female therapist appearance (F (3, 278) =2.817, p=.04). In fact, those under 39 were faster when deciding between the two female figures, than those above 39.

3.3. Decision-Making for Virtual Environments in Telepsychology

Our study also analyzed how visual cues in a virtual environment influence decision-making among potential telepsychology users. Regarding the question: “Which of the following environments would you prefer if you needed online therapy?”, we must remember that participants had three options. The simpler option had no details, and the complexity and naturalness increased in the next two options progressively, with a moderate number and maximum level of details and plants in the third option.

Participants over 39 preferred backgrounds with medium complexity and naturalness (χ2(6, N=310) =16.66, p=.01). Younger participants showed no strong preference, though they also most frequently chose the medium complexity/naturalness background. The decision tree for this question also shows a clear separation between the marked preference of those older than 39 to those younger (see

Figure 4). Regarding time responses, the medium configuration of complexity and naturalness (see

Figure 3b) provoked the fastest response with a mean of 1.5 seconds before the second fastest, that was the simpler room (F(2, 291)= 4.10, p=.02).

Regarding the type of decoration (

Figure 2a and b), when a decision between opposite levels of complexity (or naturalness) was requested, all group of ages preferred backgrounds with higher complexity and naturalness (χ2(6, N=310) =16.66, p=.01).

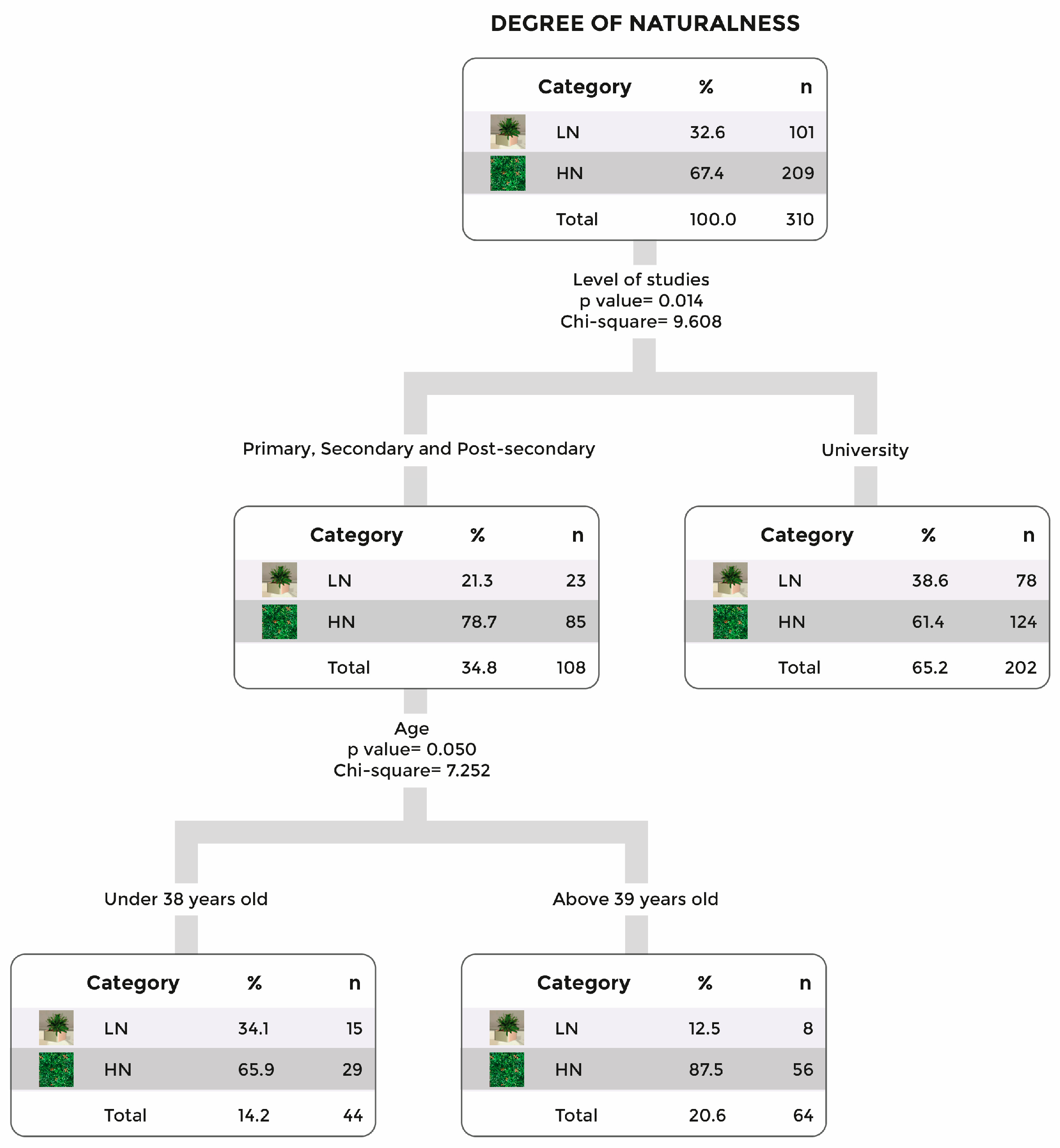

Specifically analyzing responses regarding the preferred level of naturalness in the images, a decision tree was constructed to group participants based on their responses. In this tree that can be seen in

Figure 5, a higher percentage of participants with primary, secondary, and postsecondary education selected the natural scene compared to those with university education (78.7% vs. 61.4%). As shown in

Figure 5, older participants without higher education displayed the strongest preference for this scene.

On the contrary, the question for furniture decoration according to the complexity, or number of details, did not allow us to group participants according to a clear profile as the natural decoration did.

Regarding the preferred colours for the atmosphere of the telepsychology service, the cerulean option, a bluish colour, was the most popular (38.7%), followed by observatory (19.7%), a colour with greener hues. Cerulean colour was more selected by females (44.3% vs 30.4%), whereas observatory type, was more selected by males (14.6% vs 27.2%). These differences are significant (χ2(8, N=310) =25.97, p<.01). Lastly, taking the entire sample together, the least accepted hues for telepsychology videoconferencing were reddish hues like Tia María style (2.3%) and cabaret style (2.9%).

3.4. Logistic Regression for Choices

When we applied logistic regression to the questions directed at both preferences over environments and over decorations, the variable(s) directly related to each choice were taken into account. Specifically, for the question “Which of the following environments would you prefer if you needed online therapy?” (see

Figure 3 a, b, c), the related variable was Age (χ2(6, N=310) =13.96, p=.03), so it was included in the model. Taking the metallic environment category (gray counseling room) as a reference, it was found that those aged over 39 had at least twice the probability of choosing the medium combination between naturalness and complexity background (OR=2.6; p =0.1 for those between 39 to 50 years and OR=3.8; p<0.01 for those above 50 years old), compared to younger participants.

Regarding the questions about decorations with natural motifs (vertical garden vs. potted plant) and furniture (full book shelf vs. shelf), no variable was significant to calculate the probability of choosing these decorations, so the logistic regressions did not show relevant results. Finally, in the case of plant decoration, a tendency could be observed for those over 39 years of age with non-tertiary studies (vocational training, primary and secondary) to choose options with high nature to a greater extent. This can be also seen in the decision tree for the question, previously presented (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

A growing demand for healthcare apps and software design prompted us to conduct the present work. In our study, we recruited participants as potential patients of e-mental health services, to analyze how their decision-making about key elements in therapy could vary according to their visual impression. Three were the main objectives: To analyze responses according to the appearance of the therapist, to analyze responses according to global characteristics of the image and to predict responses from specific profiles of participants.

4.1. According to Appearance of the Therapist

In the realm of person perception, something interesting to consider is that “context” encompasses a broad range of visual aspects of the environment that provide a source of expectations and predictions about the social targets likely to be perceived in that environment. The cues manipulated in this study were the style or look in both cases, for female and male therapists.

An interesting duality can be seen in our study, which breaks the general rule that, in professional contexts, someone dressed-up receives more positive evaluations and favoritism than people with casual or less stylish dresses [

52,

53,

54]. In our case, older than 50 year-olds preferred dressed-up males as counselors, but casual women were selected when the decision was between females faces. On the contrary, young people selected the inverse pattern, dressed-up female therapist vs casual male therapists. This preference for formal attire of professional women aligns with findings by [

55] who reported that young people perceived female violinists in concert dress as more technically proficient and competent than those in nightclub attire. This element adds to the knowledge that women are more likely judged by visual aspects by young people [

56].

Casual male preferences could be explained by findings that reflect that attire is not the main factor that influences opinions about competence in men [

57], and that the beard, the element chosen in this study to “create” a casual style could also be seen a cue for smart style, very congruent to the proposal for a therapeutic intervention. In fact, a perceived smart attire positively influences the impression men make on others [

58].

Also, about this former decision, and assuming the time response as an index of the strength of preferences [

59,

60], we can affirm that young people have strong preferences for dressed-up female professionals, not only in terms of percentage but in terms of strength of attitude, because younger than 39 were faster in deciding about female appearance. Another finding coherent to the use of time response as the strength of the attitude is seen when respondents who are indifferent to psychological therapy, decide about appearances in a slower manner compared to those very interested.

4.2. According to Environmental Images

Little is known about the image characteristics that have relevance when navigating in virtual environments associated with telepsychology. As we have mentioned, the global characteristics of an image studied here have been complexity, naturalness, and colour. They are not processed consciously but they do influence human behaviour [

37,

38].

In general, our results allow us to state that people prefer a virtual environment with a moderate range of items and plants and, in case of facing a decision between spaces for telepsychology services with high or low complexity (or high or low naturalness), people generally opt for high levels of both.

Regarding complexity, medium levels of organized complexity are preferred when several mountain and hilly landscapes are presented [

48,

61] and this is also demonstrated in interior preferences [

49]. Also, certain complexity is seen when people choose the best option for backgrounds in a physician consultation [

62]. So, data are unidirectional showing this trend, now confirmed for telepsychology.

Regarding naturalness, our results towards preferences of more vegetation into the background also fit with several findings. First, observers prefer architectures with a curvilinear component and this trend seems to be universal [

63]. We must remember that natural scenes contain more curvilinear elements than other scenes with handmade objects, so this preference is expected according to the geometry, but also according to the vegetation itself, which has evolutionary meaning proposed by Biophilia [

39]. Also, hybrid studies combining real and computer-manipulated environments, show that the presentation of indoor plants (but not windows) seem to improve the perception of certain premises [

50].

This preference for vegetation even for high levels was pronounced in participants over 39 who preferred the open-air photomontage (

Figure 3C). Research shows a clear preference for natural outdoor places, when activities involve creativity such as brainstorming, reflection, evaluation. In addition, natural spaces were preferred in activities where silence is preferred (reflection, lecture, reading) [

42]. It seems that this would be a stronger need for our older and middle-age individuals, who preferred the outdoor terrace for psychotherapy sessions here.

However, our results show that a moderate combination of items and plants is preferred than a high component of naturalness and complexity (see

Figure 3B vs

Figure 3C). These results, now seen in relation to telepsychology, have been seen in studies focusing on productivity. Specifically, whereas plants in the office might seem to provoke a positive effect on productivity and mood, it is also true that some accounts obtain these findings regarding productivity when a moderate (instead of a high) quantity of plants in the room is applied [

20]. Preferred plants are especially leafy [

21] as our vertical garden in

Figure 2A and rounded [

22] as the plant displayed in

Figure 3B.

The last global characteristic of the image, colour, has some interest too. Colour environment impact has an immense literature: since the influence on more fixations in landscapes [

46] to the effects on attributes such as more useful, spacious and clear spaces when white and green lights are the source of illumination in the room [

14].

According to preferences on environmental colours, blue and green were found the most preferred colours for face-to-face mental health consultation facilities [

17]. In our case, using the same palette of colours as in the former study, we found that bluish and greenish colours were the best accepted for videoconferencing psychology. In our case, we found a difference depending on sex. Males preferred a greener hue, compared to females, who preferred a bluish hue. Anyway, reddish tones were the last choices for telepsychological services by everybody.

4.3. Limitations and Prospective

Among the design limitations, the study is focused on the influence of the characteristics of the global image on decision making, but we cannot run out the possibility of the impact of the reflective processes here, not dependent on perception, given the extended response time allowed. However, we minimize the influence of extensive analysis and rationalization driven by Type 2 reasoning processes, as described by Evans [

64,

65], by limiting our analysis to responses under 20 seconds. Nevertheless, some degree of rationalization, beyond purely perceptual processing, remains possible among our participants.

In addition, another limitation is that in our study we did not analyze the link between perception and action. Hypothetical preferences from the users could not be the most demanded option in the long-term because of practical issues, or a combination between conscious and automatic processes. For example, some elements could be preferred but also produce distraction, likewise intense lighting increases male’s memory and colour affects female participants´ attention in virtual reality environments [

10]. At the same time, it is possible that positive impressions about backgrounds threaten the retention of clinical data [

66] and this derives in a lesser quality of the therapy. These are aspects to consider when designing and carrying out telepsychology studies and treatments.

In fact, further research on telepsychology services could explore dynamic facial cues in ongoing therapeutic interviews or sessions in order to go beyond the static cues presented in this study. In addition, the use of eye gaze methodology in future studies may be paramount to determine the content where the look fixates depending on different therapists, environments or backgrounds. In general, we expect that customizing the sensory experience of consultants is a mechanism that likely drives to engagement and collaboration with therapists and professionals, enhancing physical and psychological recovery.

5. Conclusions

This study enhances the knowledge about the interaction between two basic human processes: perception and decision making, analyzing the impact of visual cues on the user preferences in a simulated context of telepsychology. So far, the use of visual alterations in interaction has received limited exploration within telepsychology. In particular, our study reveals subtle differences in preferences regarding therapists between individuals older and younger than 50. We identified a specific influence of age on therapist appearance, with younger individuals (under 39) preferring more formal attire for female therapists. In terms of complexity and naturalness, our data supports the well-established notion that moderate levels of complexity and naturalness are preferred. Another significant interaction was observed between gender and color preferences, with women favoring bluish tones and men leaning towards greener hues, according to our survey. These findings suggest potential segmentation strategies for marketing in telemedicine and telepsychology services, enabling more tailored promotional approaches and resulting in more patient adherence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.L.R. and R.T. B.; methodology, M.A.M.S.; software, R.T.B.; validation, L.L.L.R., and R.T.B.; formal analysis, M.A.M.S.; investigation, L.L.L.R; resources, R.T.B.; data curation, L.L.L.R; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.L.R; writing—review and editing, M.A.M.S; visualization, M.A.M.S.; supervision, R.T.B.; project administration, L.L.L.R.; funding acquisition, R.T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding..

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Complutense University of Madrid (protocol code CE_20220217-06_SOC and date of approval 04/04/2022).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge Erica Zappi and Inés Garriga-Nogués for their design contributions to this study. We also extend our deep appreciation to the professionals at

www.terapiaencasa.es for their generous collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

Author RTB works currently in

www.terapiaencasa.es, a company in the field of telepsychology and have collaborated mainly in the procedure of this research.

References

- Pierce, B. S.; Perrin, P. B.; Tyler, C. M.; McKee, G. B.; Watson, J. D. The COVID-19 Telepsychology Revolution: A National Study of Pandemic-Based Changes in U.S. Mental Health Care Delivery. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76 (1), 14–25. [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology. American Psychologist. 2013, pp 791–800.

- Mancuso, F. LA TERAPIA ONLINE: INNOVAZIONE E INTEGRAZIONE TECNOLOGICA NELLA PRATICA CLINICA. Cogn. Clin. 2020, 16 (2), 193–207. [CrossRef]

- Mair, F.; Whitten, P. Systematic Review of Studies of Patient Satisfaction with Telemedicine. BMJ 2000, 320 (7248), 1517–1520. [CrossRef]

- Morón, J. J. M.; Aguayo, L. V. La psicoterapia on-line ante los retos y peligros de la intervención psicológica a distancia. Apunt. Psicol. 2018, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Jens, K.; Gregg, J. S. How Design Shapes Space Choice Behaviors in Public Urban and Shared Indoor Spaces- A Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102592. [CrossRef]

- Sedlmeier, A.; Feld, S. Learning Indoor Space Perception. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2018, 12 (3–4), 179–214. [CrossRef]

- Custers, P.; de Kort, Y.; IJsselsteijn, W.; de Kruiff, M. Lighting in Retail Environments: Atmosphere Perception in the Real World. Light. Res. Technol. 2010, 42 (3), 331–343. [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Ou, D. A Comparative Field Study of Indoor Environmental Quality in Two Types of Open-Plan Offices: Open-Plan Administrative Offices and Open-Plan Research Offices. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 394–404. [CrossRef]

- Nolé Fajardo, M. L.; Higuera-Trujillo, J. L.; Llinares, C. Lighting, Colour and Geometry: Which Has the Greatest Influence on Students’ Cognitive Processes? Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12 (4), 575–586. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Moon, J. W.; Kim, S. Analysis of Occupants’ Visual Perception to Refine Indoor Lighting Environment for Office Tasks. Energies 2014, 7 (7), 4116–4139. [CrossRef]

- Nikookar, N.; Sawyer, A. O.; Goel, M.; Rockcastle, S. Investigating the Impact of Combined Daylight and Electric Light on Human Perception of Indoor Spaces. Sustainability 2024, 16 (9). [CrossRef]

- Hidayetoglu, M. L.; Yildirim, K.; Akalin, A. The Effects of Color and Light on Indoor Wayfinding and the Evaluation of the Perceived Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32 (1), 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Odabaşioğlu, S.; Olguntürk, N. Effects of Coloured Lighting on the Perception of Interior Spaces. Percept. Mot. Skills 2015, 120 (1), 183–201. [CrossRef]

- von Castell, C.; Hecht, H.; Oberfeld, D. Which Attribute of Ceiling Color Influences Perceived Room Height? Hum. Factors 2018, 60 (8), 1228–1240. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Frumento, S.; Nese, M.; Predieri, I. Interior Color and Psychological Functioning in a University Residence Hall. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ji, J.; Chen, H.; Ye, C. Optimal Color Design of Psychological Counseling Room by Design of Experiments and Response Surface Methodology. PLOS ONE 2014, 9 (3), e90646. [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, F.; Leng, X. Colour Here, There, and in-between—Placemaking and Wayfinding in Mental Health Environments. Color Res. Appl. 2021, 46 (1), 125–139. [CrossRef]

- Ritterlfeld, U.; Cupchik, G. C. Perceptions of Interior Spaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16 (4), 349–360. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Adams, J.; Deal, B.; Kweon, B. S.; Tyler, E. Plants in the Workplace: The Effects of Plant Density on Productivity, Attitudes, and Perceptions. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30 (3), 261–281. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Suzuki, N. Effects of the Foliage Plant on Task Performance and Mood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22 (3), 265–272. [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Essah, E.; Blanusa, T.; Beaman, C. P. The Appearance of Indoor Plants and Their Effect on People’s Perceptions of Indoor Air Quality and Subjective Well-Being. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109151. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.; Knight, C.; Postmes, T.; Haslam, S. A. The Relative Benefits of Green versus Lean Office Space: Three Field Experiments. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2014, 20 (3), 199–214. [CrossRef]

- Moscoso, C.; Chamilothori, K.; Wienold, J.; Andersen, M.; Matusiak, B. Window Size Effects on Subjective Impressions of Daylit Spaces: Indoor Studies at High Latitudes Using Virtual Reality. LEUKOS 2021, 17 (3), 242–264. [CrossRef]

- Goethe, O.; Sørum, H.; Johansen, J. The Effect or Non-Effect of Virtual Versus Non-Virtual Backgrounds in Digital Learning. In Human Interaction, Emerging Technologies and Future Systems V; Ahram, T., Taiar, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp 274–281. [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. H. M.; Qiu, L.; Lam, J. An Investigation into the Stress-Buffering Effects of Nature Virtual Backgrounds in Video Calls. In Applied Psychology Readings; Moore, B., Murray, E., Winslade, M., Tan, L.-M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Palanica, A.; Fossat, Y. Effects of Nature Virtual Backgrounds on Creativity during Videoconferencing. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 43, 100976. [CrossRef]

- Sharam, L. A.; Mayer, K. M.; Baumann, O. Design by Nature: The Influence of Windows on Cognitive Performance and Affect. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 85, 101923. [CrossRef]

- Global Business Development Teams – Market.us. Telemedicine Market Size to Surpass USD 590.9 billion in value by 2032, at CAGR of 25.7% - Market.us. GlobeNewsWire. https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2023/02/27/2616144/0/en/Telemedicine-Market-Size-to-Surpass-USD-590-9-billion in-value-by-2032-at-CAGR-of-25-7-Market-us.html (accessed 2024-10-10).

- Campbell, J. L. Identifying Digital Rhetoric in the Telemedicine User Interface. J. Tech. Writ. Commun. 2023, 53 (2), 89–105. [CrossRef]

- Hames, J. L.; Bell, D. J.; Perez-Lima, L. M.; Holm-Denoma, J. M.; Rooney, T.; Charles, N. E.; Thompson, S. M.; Mehlenbeck, R. S.; Tawfik, S. H.; Fondacaro, K. M.; Simmons, K. T.; Hoersting, R. C. Navigating Uncharted Waters: Considerations for Training Clinics in the Rapid Transition to Telepsychology and Telesupervision during COVID-19. J. Psychother. Integr. 2020, 30 (2), 348–365. [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, A.; Agha, Z.; Maglione, M. L.; Repp, A.; Ross, B.; Zuest, D.; Rice-Thorp, N. M.; Lohr, J.; Thorp, S. R. Videoconferencing Psychotherapy: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9 (2), 111–131. [CrossRef]

- Schweiker, M.; Ampatzi, E.; Andargie, M. S.; Andersen, R. K.; Azar, E.; Barthelmes, V. M.; Berger, C.; Bourikas, L.; Carlucci, S.; Chinazzo, G.; Edappilly, L. P.; Favero, M.; Gauthier, S.; Jamrozik, A.; Kane, M.; Mahdavi, A.; Piselli, C.; Pisello, A. L.; Roetzel, A.; Rysanek, A.; Sharma, K.; Zhang, S. Review of Multi-domain Approaches to Indoor Environmental Perception and Behaviour. Build. Environ. 2020, 176, 106804. [CrossRef]

- McBain, R. K.; Schuler, M. S.; Qureshi, N.; Matthews, S.; Kofner, A.; Breslau, J.; Cantor, J. H. Expansion of Telehealth Availability for Mental Health Care After State-Level Policy Changes From 2019 to 2022. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6 (6), e2318045–e2318045. [CrossRef]

- Özgüzel, C.; Luca, D.; Wei, Z. The New Geography of Remote Jobs? Evidence from Europe; OECD: Paris, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Torous, J.; Nicholas, J.; Carney, R.; Pratap, A.; Rosenbaum, S.; Sarris, J. The Efficacy of Smartphone-Based Mental Health Interventions for Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. World Psychiatry 2017, 16 (3), 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Modeling the Shape of the Scene: A Holistic Representation of the Spatial Envelope. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2001, 42 (3), 145–175. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Chapter 2 Building the Gist of a Scene: The Role of Global Image Features in Recognition. In Progress in Brain Research; Martinez-Conde, S., Macknik, S. L., Martinez, L. M., Alonso, J.-M., Tse, P. U., Eds.; Elsevier, 2006; Vol. 155, pp 23–36. [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. Biophilia Revisited: Nature versus Nurture. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38 (9), 792–794. [CrossRef]

- Schiebel, T.; Gallinat, J.; Kühn, S. Testing the Biophilia Theory: Automatic Approach Tendencies towards Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101725. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Park, B.-J.; Lee, J.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Forest Walking Affects Autonomic Nervous Activity: A Population-Based Study. Front. Public Health 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Mangone, G.; Capaldi, C. A.; van Allen, Z. M.; Luscuere, P. G. Bringing Nature to Work: Preferences and Perceptions of Constructed Indoor and Natural Outdoor Workspaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Cognitive Maps in Perception and Thought. In Image and environment: Cognitive mapping and spatial behavior; 1973; pp 63–78.

- Johnson-Laird, P. N. The History of Mental Models. In Psychology of reasoning; 2004; pp 189–222.

- Kaplan, S. Aesthetics, Affect, and Cognition: Environmental Preference from an Evolutionary Perspective. Environ. Behav. 1987, 19 (1), 3–32. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A. S.-H.; Lin, Y.-J. The Effect of Landscape Colour, Complexity and Preference on Viewing Behaviour. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45 (2), 214–227. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Luo, J.; Liu, Q.; Lan, Y. Landscape Design Intensity and Its Associated Complexity of Forest Landscapes in Relation to Preference and Eye Movements. Forests 2023, 14 (4). [CrossRef]

- Lavdas, A. A.; Schirpke, U. Aesthetic Preference Is Related to Organized Complexity. PLOS ONE 2020, 15 (6), e0235257. [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. C. Complexity and Mystery as Predictors of Interior Preferences. J. Inter. Des. 1993, 19 (1), 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cha, S. H.; Koo, C.; Tang, S. The Effects of Indoor Plants and Artificial Windows in an Underground Environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 138, 53–62. [CrossRef]

- VanRullen, R.; Thorpe, S. J. The Time Course of Visual Processing: From Early Perception to Decision-Making. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2001, 13 (4), 454–461. [CrossRef]

- Dacy, J. M.; Brodsky, S. L. Effects of Therapist Attire and Gender. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1992, 29 (3), 486–490. [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; van Prooijen, J.-W.; van Lange, P. A. M. Status Cues and Moral Judgment: Formal Attire Induces Moral Favoritism but Not for Hypocrites. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43 (21), 19247–19263. [CrossRef]

- Howlett, N.; Pine, K.; Orakçıoğlu, I.; Fletcher, B. The Influence of Clothing on First Impressions. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 17 (1), 38–48. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, N. K. ‘Posh Music Should Equal Posh Dress’: An Investigation into the Concert Dress and Physical Appearance of Female Soloists. Psychol. Music 2010, 38 (2), 159–177. [CrossRef]

- Morris, T. L.; Gorham, J.; Cohen, S. H.; Huffman, D. Fashion in the Classroom: Effects of Attire on Student Perceptions of Instructors in College Classes. Commun. Educ. 1996, 45 (2), 135–148. [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Shafir, E.; Todorov, A. Economic Status Cues from Clothes Affect Perceived Competence from Faces. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4 (3), 287–293. [CrossRef]

- Gurney, D. J.; Howlett, N.; Pine, K.; Tracey, M.; Moggridge, R. Dressing up Posture: The Interactive Effects of Posture and Clothing on Competency Judgements. Br. J. Psychol. 2017, 108 (2), 436–451. [CrossRef]

- Alós-Ferrer, C.; Garagnani, M. Who Likes It More? Using Response Times to Elicit Group Preferences in Surveys; Working Paper 422; University of Zurich, Department of Economics: Zurich, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shadlen, M. N.; Kiani, R. Decision Making as a Window on Cognition. Neuron 2013, 80 (3), 791–806. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhuo, Z.; Ye, B.; Fang, L.; Huang, Q.; Lai, P. The Impact of Landscape Complexity on Preference Ratings and Eye Fixation of Various Urban Green Space Settings. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127411. [CrossRef]

- Houchens, N.; Saint, S.; Kuhn, L.; Ratz, D.; Engle, J. M.; Meddings, J. Patient Preferences for Telemedicine Video Backgrounds. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7 (5), e2411512–e2411512. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Puerto, G.; Rosselló, J.; Corradi, G.; Acedo-Carmona, C.; Munar, E.; Nadal, M. Preference for Curved Contours across Cultures. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2018, 12 (4), 432–439. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. St. B. T. Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 2008, 59, 255–278. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. St. B. T. Reflections on Reflection: The Nature and Function of Type 2 Processes in Dual-Process Theories of Reasoning. Think. Reason. 2019, 25 (4), 383–415. [CrossRef]

- Stosic, M. D.; Duane, J.-N.; Durieux, B. N.; Sando, M.; Robicheaux, E.; Podolski, M.; Sanders, J. J.; Ericson, J. D.; Blanch-Hartigan, D. Patient Preference for Telehealth Background Shapes Impressions of Physicians and Information Recall: A Randomized Experiment. Telemed. E-Health 2022, 28 (10), 1541–1546. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).