Introduction

Hypertensive emergencies are clinical conditions marked by acute or persistent injury to target organs and significantly increased blood pressure, usually ≥180/120 mm Hg.[

1] The

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.[

2,

3] Hypertension is a common chronic problem in patients hospitalized for COVID-19.[

4] Acute blood pressure increases in COVID-19 patients may be linked to in-hospital mortality, intensive care unit admission, heart failure, acute end-organ damage, and a worse outcome.[

5] The physiological reactions to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), such as sympathetic nervous system (SNS) hyperactivity, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) dysregulation, and cardiovascular strain can result in a marked increase in blood pressure, although ARDS itself does not directly cause a hypertensive emergency.[

6] Inflammation, hypoxia, RAAS dysregulation, and iatrogenic factors are some of the ways in which COVID-19 can dramatically worsen preexisting hypertension, resulting in a hypertensive emergency.[

7]

Treatment of a hypertensive emergency involves monitoring or treating end-organ damage and promptly controlling blood pressure (BP) with intravenous antihypertensives (such as labetalol or nicardipine). Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and diuretics may be useful in the treatment of excessive blood pressure in patients with COVID-19.[

8] According to this case report, a patient who had previously been diagnosed with hypertension and SARS-CoV-2 had a hypertensive emergency.

This Study Adds

This study emphasizes the necessity of integrated care pathways to handle hypertensive emergencies, with an emphasis on minimizing organ damage and enhancing patient outcomes, as well as the integrated mechanisms to exhibit hypertensive emergencies in COVID-19 settings. They also underscored the importance of checking blood pressure early in COVID-19 patients, especially if they have hypertension or other cardiovascular concerns. A more complex understanding of the relationship between viral infections and chronic diseases is possible by the inclusion of COVID-19 as a factor in hypertensive emergencies. This will help shape preventive and management strategies for future pandemics.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old black male merchant was admitted to the emergency room on July 12, 2022, with a chief complaint of shortness of breath for two days. He had shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, and weakness. The patient also exhibited edema and symmetric palpable pulses in his lower limbs. He had a history of medical treatment and medication use. During the past five years, he had stage I hypertension. He had been taking enalapril and hydrochlorothiazide. He had never smoked or consumed alcohol or tea. He effectively managed his blood pressure with antihypertensive drugs and dietary modifications. He was unaware of the family’s medical history and medications. Two weeks before his admission, he had no history of trauma. He had never previously been diagnosed with COVID-19. He lived with his wife, who was under investigation for COVID-19, and was positive four days prior to his admission.

Upon admission, he had a high blood pressure of 204/109 mmHg, a heart rate of 104 beats per minute, a body temperature of 39.7 °C, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, a weight of 87 kg, a height of 1.72 m, a body mass index of 29.4 kg/m², and an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air. Laboratory investigations of the patient revealed: blood urea nitrogen of 21 mg/dL (normal value: 6-20 mg/dL), potassium of 4.0 mmol/L (normal value: 3.6-5.2 mmol/L), sodium of 139 mEq/L (normal value: 135-145 mEq/L), fasting blood glucose of 104 mg/dL (normal value: 100-126 mg/dL), higher density lipoprotein of 47 mg/dL (normal value: 40-60 mg/dL), lower density lipoprotein of 119 mg/dL (normal value: 100-129 mg/dL), triglycerides of 133 mg/dl (normal value: < 150 mg/dL), hemoglobin of 14.1 mg/dL (normal value: 13.8-17.2 mg/dL), hematocrit of 44% (normal value: 41-50%), and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL (normal value: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL), urinalysis revealed urine crystals, white blood cell of 12,190 cells/mm3 (normal value: 4,500-11,000 cells/mm3), neutrophils of 65% (normal value: 55-70%), and lymphocytes of 37% (normal value: 20-40%). The troponin levels were normal.

Electrocardiography (ECG) revealed left axis deviation inversion, sinus tachycardia, and ST-segment elevation. There were no hypodense areas showing brain tissue infarction or hyperdense areas showing bleeding (such as in the thalamus or basal ganglia) on the CT scan of the brain. Vasogenic edema in the parietal and occipital lobes was not visible on the MRI. Chest radiography revealed an enlarged mediastinum and widespread alveolar infiltration. Echocardiography revealed a discernible intimal flap and thicker ventricular wall. No hypoenhanced renal regions were visible on the abdominal CT scan. He was eventually diagnosed with COVID-19 infection and a hypertensive emergency. After a nasopharyngeal swab PCR test showed COVID-19 positivity, the patient was sent to an intensive care unit.

He was still receiving oxygen through a nasal cannula at a rate of four liters per minute in the intensive care unit. Oxygen saturation reached 95%, which is regarded as the normal range, after 45 min. As soon as he was taken to the critical care unit, he began receiving fluid resuscitation (0.9% normal saline). Hydralazine (5 mg) was administered intravenously immediately. The patient was then re-evaluated after 20 minutes. After two injections of hydralazine at a dose of 5 mg each, the patient experienced reflex tachycardia. The physician subsequently changed hydralazine to 50 mg atenolol, which was administered orally once daily. Atenolol lowers heart rate by inhibiting β1 receptors in the heart, which stops hydralazine-induced reflex tachycardia. Additionally, he began taking 20 mg of sustained-release nifedipine orally, twice a day. By addressing both vascular resistance (by nifedipine) and cardiac output (via atenolol), nifedipine and atenolol work in concert to improve blood pressure. Atenolol prevents reflex tachycardia, a side effect of nifedipine alone. He received ≈ 5,000 IU of low-molecular-weight heparin every 12 hours to prevent prothrombotic episodes. He received 500 mg azithromycin once daily for five days to prevent secondary bacterial infections. He was administered 500 mg of acetaminophen when necessary to treat his fever.

Outcome and Follow-Up

After 17 days in the hospital and two consecutive negative COVID-19 throat swab test results were obtained. Subsequently, he was released to return to his house. He was counseled to take nifedipine in addition to his prescription for hypertension medication. It was advised to keep up with his monthly follow-up appointment at an ambulatory clinic.

Discussion

COVID-19 intricate interactions with the cardiovascular and renal systems greatly worsen hypertension in people who already have hypertension.[

9] Million people have been infected by the COVID-19 virus as it has spread worldwide.[

10] Risk factors linked to COVID-19 include age, hypertension, cancer, prior cerebrovascular disease, a history of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. Hypertension most frequently affects COVID-19 patients.[

4]

The characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 hospitalized patients have discovered that hypertension increases the risk of serious clinical outcomes. In particular, hypertension is linked to a higher rate of ICU admission, worsening heart failure, and increased death in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.[

11] Target-organ damage includes cardiac ischemia, advanced retinopathy, hypertensive encephalopathy, acute stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema, acute aortic disease, eclampsia, and severe pre-eclampsia/HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver.[

12] The study's patient in this study experienced target organ damage from hypertensive emergencies, including myocardial infarction (caused by ST-segment elevation), acute coronary syndrome (caused by increased cardiac output and oxygen demand), left ventricular failure (caused by acute pulmonary edema), and left ventricular hypertrophy (caused by left axis deviation).

COVID-19 with pre-existing hypertension can interact in a number of ways that could result in a hypertensive emergency. These two diseases can combine to create a hypertensive emergency in the following manner. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity: In individuals with preexisting hypertension and COVID-19, SNS activation can exacerbate elevated blood pressure, potentially triggering a hypertensive emergency. The underlying cardiovascular changes in hypertensive individuals (e.g., stiffened arteries and left ventricular hypertrophy) make them more vulnerable to the effects of increased SNS activity.[

13]

RAAS dysregulation: In individuals with hypertension, RAAS dysregulation can intensify the vasoconstrictive actions of angiotensin II, raising blood pressure even further. Because the kidneys, heart, and other organs are under higher stress, this worsens the condition of hypertension and raises the possibility of a hypertensive emergency.[

14] Hypoxia and respiratory stress: COVID-19 can increase blood pressure to extremely high levels in those who already have hypertension. Increased cardiac output, vasoconstriction, and hypoxia can lead to a hypertensive emergency, particularly if blood pressure is not properly controlled.[

15]

Acute cardiac and renal complications: Patients with hypertension already have a burden on their hearts and kidneys owing to their long-term high blood pressure. Both cardiac and renal functions may suffer an abrupt decline as a result of the additional strain caused by COVID-19-related inflammation, hypoxia, and RAAS dysregulation. Acute end-organ damage, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and renal failure, may result from a hypertensive emergency.[

16] Medications and iatrogenic factors: The use of medications such as corticosteroids or antivirals to treat COVID-19 in people who already have hypertension might raise blood pressure even more and could cause a hypertensive emergency, particularly if the blood pressure is not closely monitored or controlled.[

17]

Vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction: Chronic hypertension already results in blood vessel stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. This effect is exacerbated by endothelial damage linked to COVID-19, which increases blood pressure and the likelihood of acute consequences, including hypertensive emergencies.[

18] Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The body's compensatory responses, including vasoconstriction and an elevated heart rate, can increase blood pressure in conjunction with the stress of ARDS. People with preexisting hypertension may experience sudden increases in blood pressure, which could lead to hypertensive emergencies.[

19]

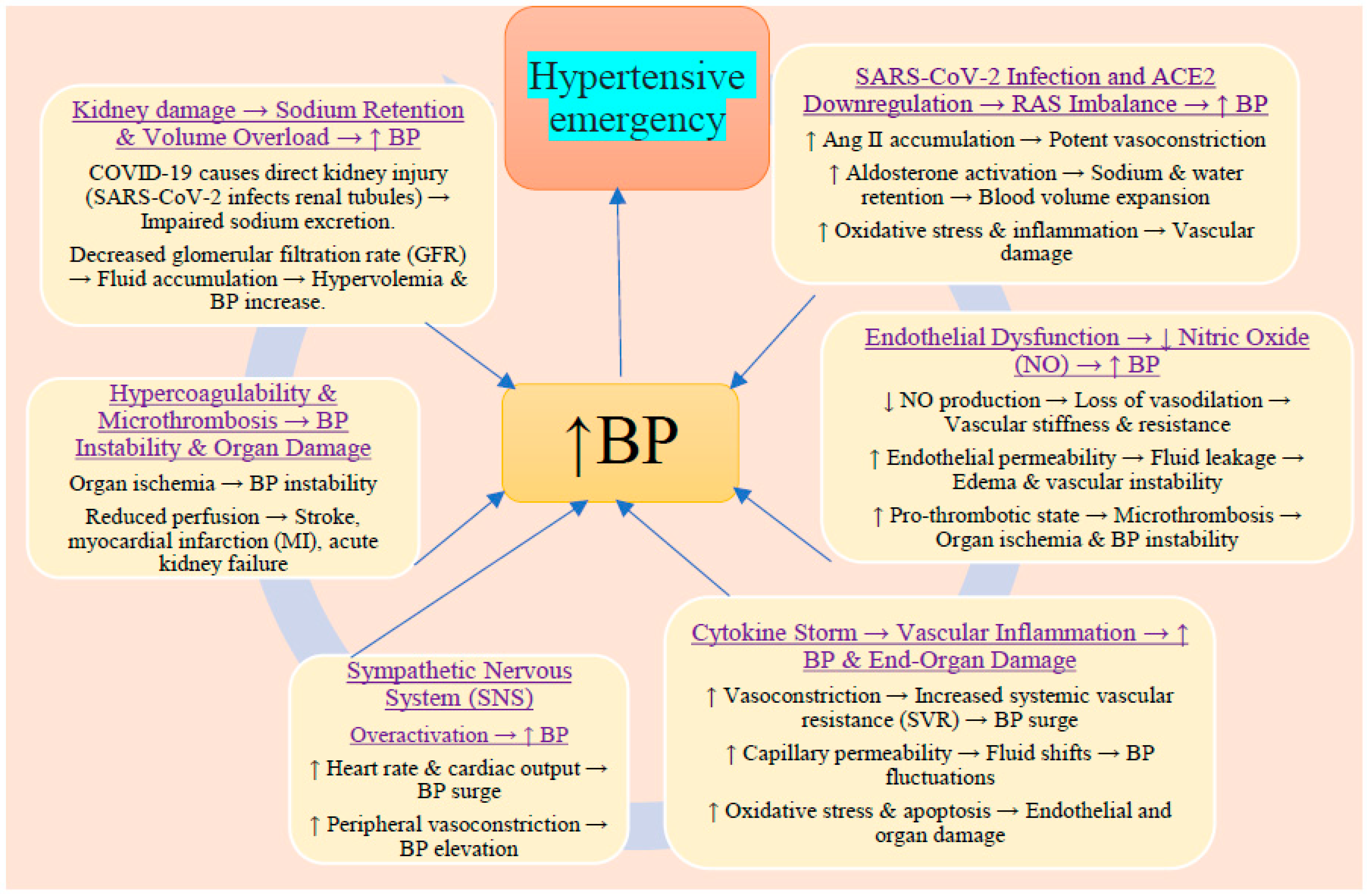

Figure 1.

In hypertensive patients, COVID-19 exacerbates pre-existing hypertension through multiple interrelated mechanisms.

Figure 1.

In hypertensive patients, COVID-19 exacerbates pre-existing hypertension through multiple interrelated mechanisms.

Numerous factors, including the extent of organ damage, the promptness and efficacy of medical care, and the patient's general health and comorbidities, influence the prognosis of hypertensive emergencies caused by COVID-19 and preexisting hypertension. Acute hypertension and COVID-19-induced hypertensive emergencies with preexisting hypertension typically have a worse prognosis because of intense systemic inflammation, a higher likelihood of multiorgan damage failure, and difficulties controlling both conditions simultaneously.[

20]

In most hypertensive situations, the mean arterial pressure (MAP) should be gradually reduced (by 10–20% in the first hour and another 5–15% over the next 23 hours). For the first hour, the goal was to lower the systolic and diastolic blood pressures by 180 and 120 mmHg, respectively. Systolic/diastolic blood pressure should be reduced to 160 and 110 mmHg within the next 23 h. [

21]

The site of organ damage mostly influences the choice of blood pressure-lowering medications, target blood pressure, and the timeframe by which blood pressure reduction should be achieved for hypertensive emergencies in COVID-19.[

22] The interaction of the cardiovascular, renal, and respiratory systems necessitates careful consideration while treating a hypertensive emergency in a patient with COVID-19 and preexisting hypertension. Antiviral therapy, oxygen supplementation, corticosteroids (such as dexamethasone in extreme cases), and anticoagulation, if necessary, are used to treat COVID-19. Treatment of a hypertensive emergency involves monitoring or treating end-organ damage and immediately controlling blood pressure with intravenous antihypertensives (such as labetalol or nicardipine).[

23] In this study, hydralazine (5 mg) intravenously was given right away. After 20 minutes, the patient was re-evaluated. The patient experienced reflex tachycardia following two injections of hydralazine (5 mg each). The physician subsequently changed hydralazine to 50 mg atenolol, which was administered orally once daily.

Conclusion

In hypertensive patients, COVID-19 disrupts cardiovascular homeostasis through ACE2 depletion, RAS imbalance, endothelial dysfunction, cytokine storm, sympathetic overactivation, renal impairment, and hypercoagulability. These mechanisms collectively increase BP and cause severe hypertensive emergencies, leading to stroke, myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, and multi-organ failure. Early BP control and anti-inflammatory treatment are crucial to reducing mortality and preventing fatal outcomes. Pharmacological treatments should prioritize the rapid control of blood pressure while addressing the underlying COVID-19-related complications. In this study, hydralazine (5 mg) was intravenously given immediately, and the patient was reevaluated after 20 min.

Key Points

By binding to ACE2 receptors, SARS-CoV-2 reduces the protective effects of ACE2 on blood pressure regulation and exacerbates hypertension. COVID-19 causes endothelial cell destruction, which hinders vasodilation and increases vascular resistance, ultimately leading to increased blood pressure.

Ethical Approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the study participants for their willingness to respond to all questions.

Funding Information

None.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest to report.

References

- Mathews EP, Newton F, Sharma K. CE: hypertensive emergencies: a review. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2021 Oct 1;121(10):24-35. [CrossRef]

- Atzrodt CL, Maknojia I, McCarthy RD, et al. A Guide to COVID-19: a global pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The FEBS journal. 2020 Sep;287(17):3633-50.

- Atri D, Siddiqi HK, Lang J, et al. COVID-19 for the cardiologist: a current review of the virology, clinical epidemiology, cardiac and other clinical manifestations and potential therapeutic strategies. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020 Apr 10;5(5):518-36.

- Li J, Wang X, Chen J, et al. Association of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA cardiology. 2020 Jul 1;5(7):825-30.

- Peixoto, AJ. Acute severe hypertension. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019 Nov 7;381(19):1843-52.

- Swenson KE, Swenson ER. Pathophysiology of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19 Lung Injury. Crit Care Clin. 2021 Oct;37(4):749-776.

- Savedchuk S, Raslan R, Nystrom S, et al. Emerging viral infections and the potential impact on hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease. Circulation Research. 2022 May 13;130(10):1618-41.

- Banasik JL. Pathophysiology-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021 May 29.

- Savedchuk S, Raslan R, Nystrom S, et al. Emerging viral infections and the potential impact on hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease. Circulation Research. 2022 May 13;130(10):1618-41.

- Singhal, T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). The indian journal of pediatrics. 2020 Apr;87(4):281-6.

- De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Lanzani C, et al. Residual clinical damage after COVID-19: A retrospective and prospective observational cohort study. PloS one. 2020 Oct 14;15(10): e0239570.

- van den Born BJ, Lip GY, Brguljan-Hitij J, et al. ESC Council on hypertension position document on the management of hypertensive emergencies. European Heart Journal–Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):37-46.

- DeLalio LJ, Sved AF, Stocker SD. Sympathetic Nervous System Contributions to Hypertension: Updates and Therapeutic Relevance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 May;36(5):712-720.

- Manrique C, Lastra G, Gardner M, et al. The renin angiotensin aldosterone system in hypertension: roles of insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Med Clin North Am. 2009 May;93(3):569-82.

- Fedorowski A, Fanciulli A, Raj SR, et al. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a major health-care burden. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2024 Jun;21(6):379-95.

- Burnier M, Damianaki A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ Res. 2023 Apr 14;132(8):1050-1063.

- Batiha GE, Gari A, Elshony N, et al. Hypertension and its management in COVID-19 patients: The assorted view. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. 2021 Dec; 11:200121.

- Tavares CA, Bailey MA, Girardi AC. Biological context linking hypertension and higher risk for COVID-19 severity. Frontiers in physiology. 2020 Nov 19; 11:599729.

- Augustine R, Abhilash S, Nayeem A, et al. Increased complications of COVID-19 in people with cardiovascular disease: Role of the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) dysregulation. Chemico-biological interactions. 2022 Jan 5; 351:109738.

- Siddiqi TJ, Usman MS, Rashid AM, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Hypertensive Emergency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023 Jul 18;12(14): e029355.

- Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Reboldi G. Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency and emergency in COVID-19 patients. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2022 Jan 22;23(2):235-42.

- Balahura AM, Moroi ȘI, Scafa-Udrişte A, et al. The Management of Hypertensive Emergencies—Is There a “Magical” Prescription for All? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022 May 31;11(11):3138.

- Khan M, Singh GK, Abrar S, et al. Pharmacotherapeutic agents for the management of COVID-19 patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2021 Dec;22(18):2455-2474.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).